Matendere Monument

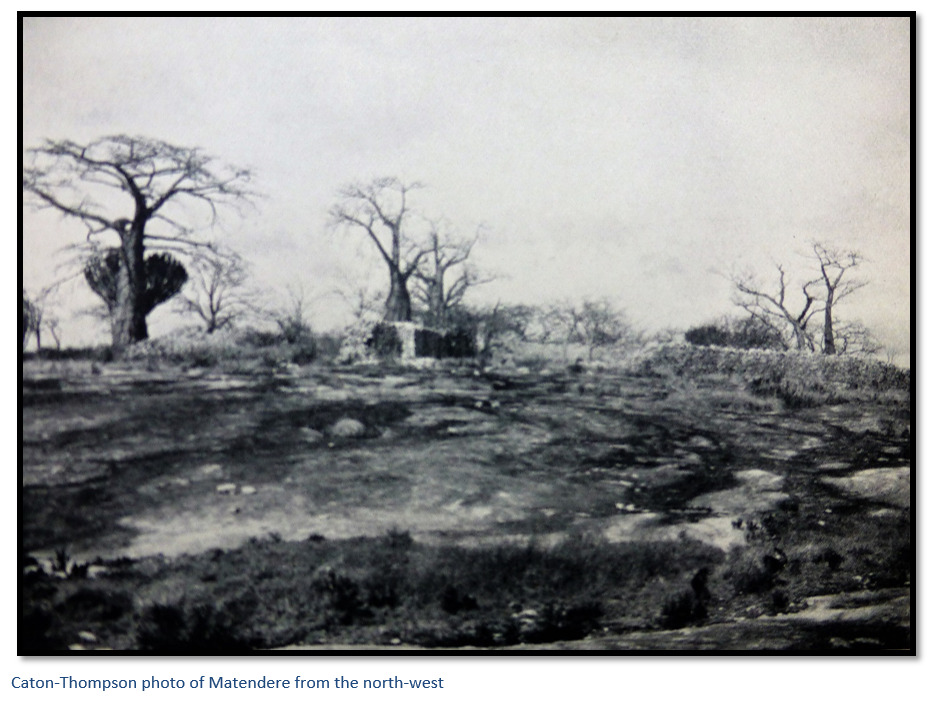

- Matendere Monument is located on a prominent granite ‘whale-back’ in the Buhera district, 50 kilometres south of Murambinda Growth Point in the Buhera district and well off the usual tourist track.

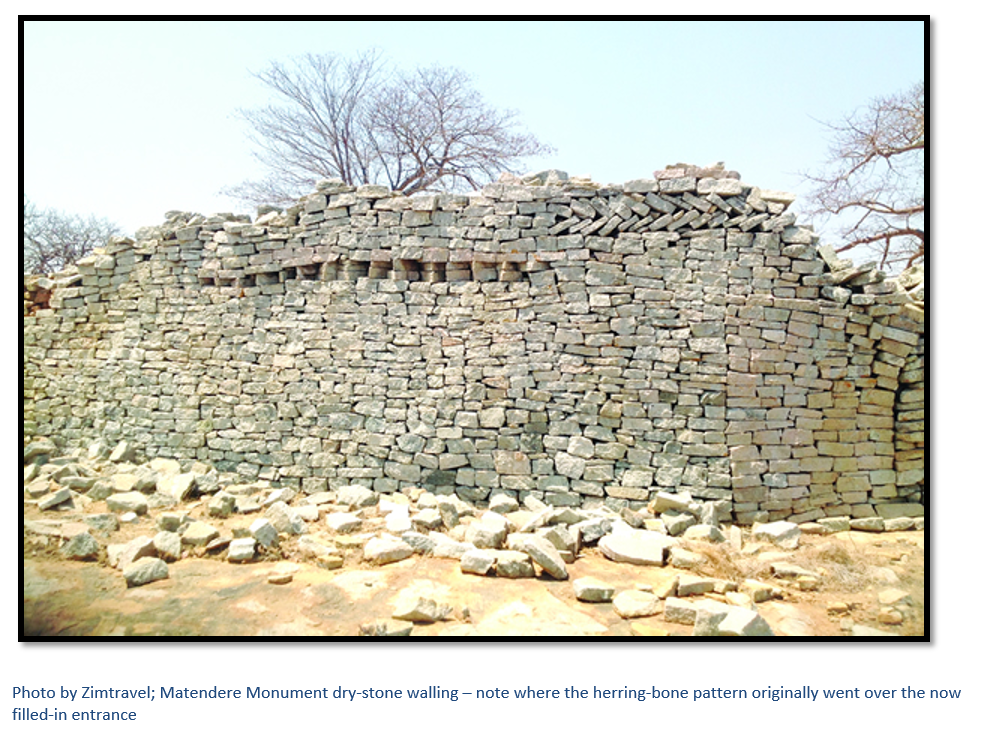

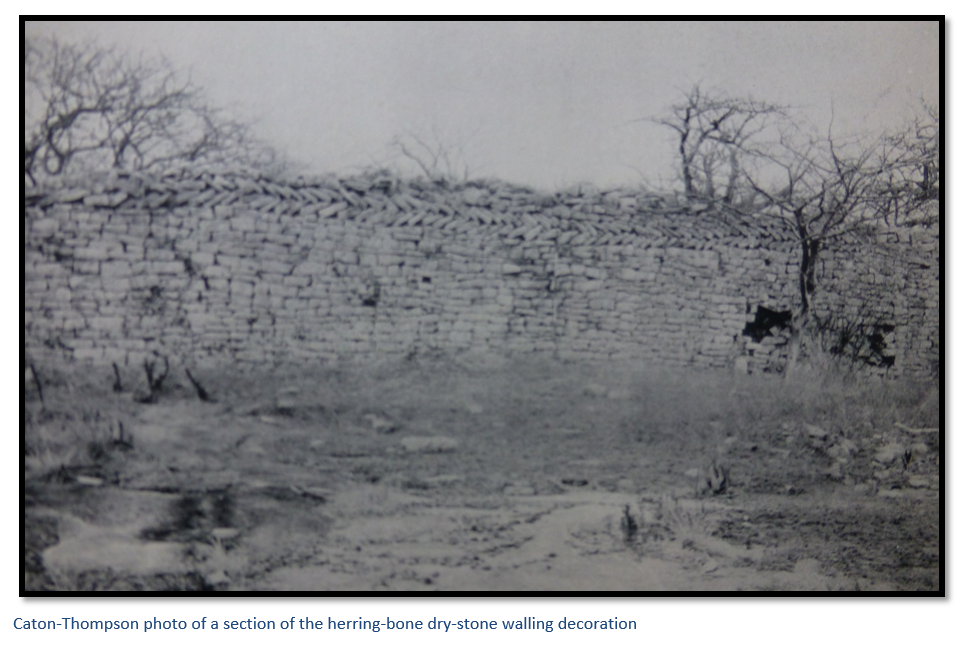

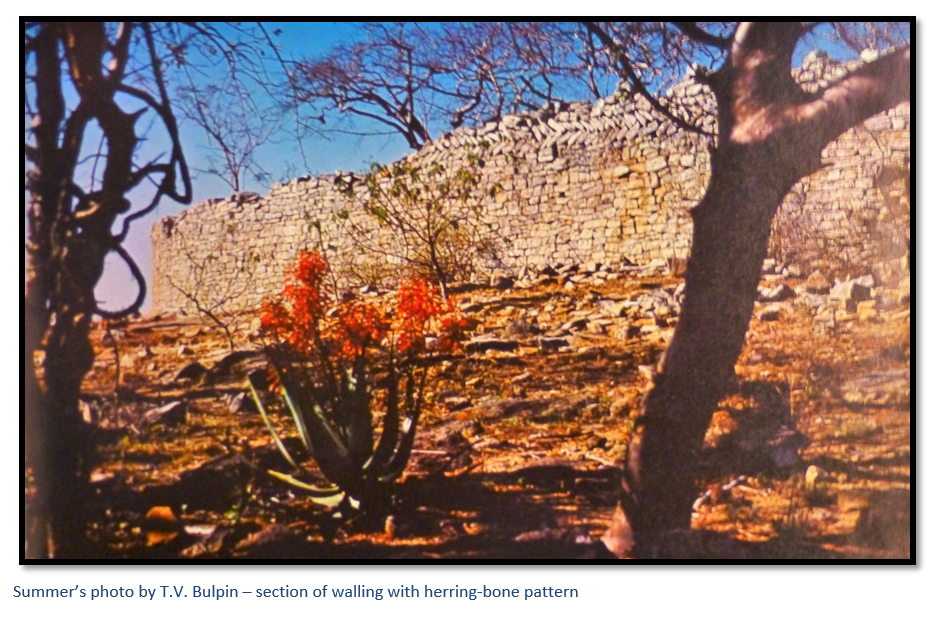

- The site is an excellent example of a Zimbabwe-style enclosure and is known for its herringbone and dentelle decorations in the dry-stone walling, plus two monoliths at the top on the perimeter wall.

- Theodore Bent, an English traveller and antiquarian (but not an archaeologist) in 1891 carried out a dig at Great Zimbabwe and a survey of Matendere with Swan, a surveyor. They concluded that the buildings at Great Zimbabwe were a temple and fortress and were ancient in origin and built by foreigners, they favoured the Phoenicians, a view originally proposed by Karl Mauch in 1871. It is interesting to note that F.C. Selous differed completely in his views; saying they were comparatively modern and built by local Africans.

- Matendere is the largest of a group of six monuments that also includes Kagumbudzi, Muchuchu, Chironga, Chiwona and Gombe; all of which are situated on the summit of steep-sided kopje’s that give a commanding view over the surrounding countryside and as a group are described by Gertrude Caton-Thompson in her book The Zimbabwe Culture.

- In recent years the Buhera Council and National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe have held an annual cultural festival at Matendere which is well-attended by local people and officials to celebrate Zimbabwe’s cultural heritage and its local traditions.

From Birchenough Bridge take the A9 heading toward Masvingo, 6.4 KM turn right and head north west, 12.84 turn left heading west, 23.3 KM cross a river, 34.7 KM cross a river, 55.6 Km travel through kopjes, 59.2 KM continue straight on ignoring the road crossing to left and right, 65.9 KM continue straight on ignoring the road to the right, 77.2 KM take the road to the left going west, 85.4 KM Ruti Dam comes into view, 88 KM reach school and enquire after best route to Matendere Ruins which is 3.5 kilometres to the east of here.

GPS reference: 19⁰30′53″S 31⁰47′36″E

I have not personally visited Matendere Monument and would appreciate any recent photographs which visitors are prepared to let me add to the article; they will be acknowledged, of course.

The existence of Matendere has been known for a long time to travellers and early archaeologists.

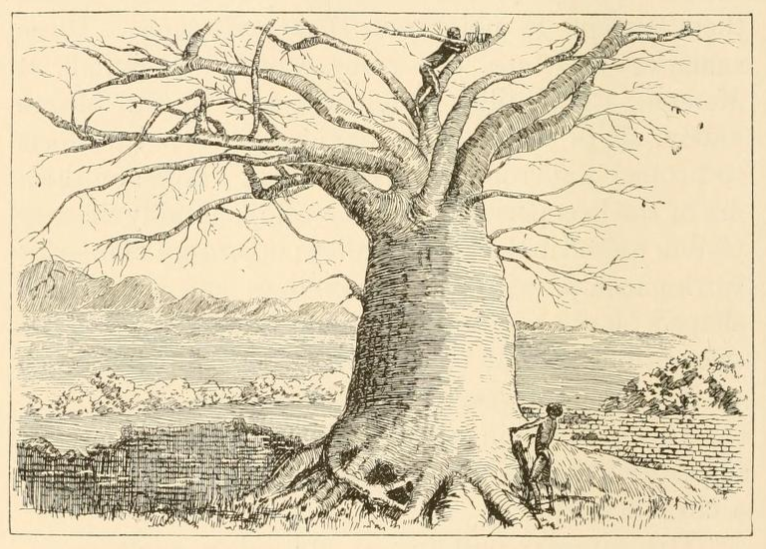

Llewellyn Cambria Meredith (1866-1942) who led Theodore Bent (author of The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland) in 1891 to Great Zimbabwe and became a Native Commissioner in Manicaland described Matendere as follows: “The ruins were of the same nature as those of Zimbabwe. They are not so well built, or extensive. The walls were not more than seven feet high and in one place a baobab tree had grown up through the walls, the tree being about six feet in diameter and about thirty-five feet high. The ruins were in a partly circular form and about forty yards wide with a few dividing walls. In fact, after seeing and working at Zimbabwe, they were not very interesting.”

Bent states in his book The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland that ‘Matindela’ is the second most important monument in the country with the area of enclosure almost as large as that at Great Zimbabwe. From their observations that the south-west walls were so strongly built and well-decorated and that the north-eastern side had been left open, Bent and Swan concluded that the building had been a temple, rather than a fortress. Bent noted that the enclosure walls were of inferior construction to those at Great Zimbabwe, but that the complex herring-bone and dentelle patterns signified a more complex purpose than just decoration. He was the first to notice the holes in the tops of the walls for inserting stone monoliths as at Great Zimbabwe.

Bent sketch of walling and a baobab tree at Matendere.

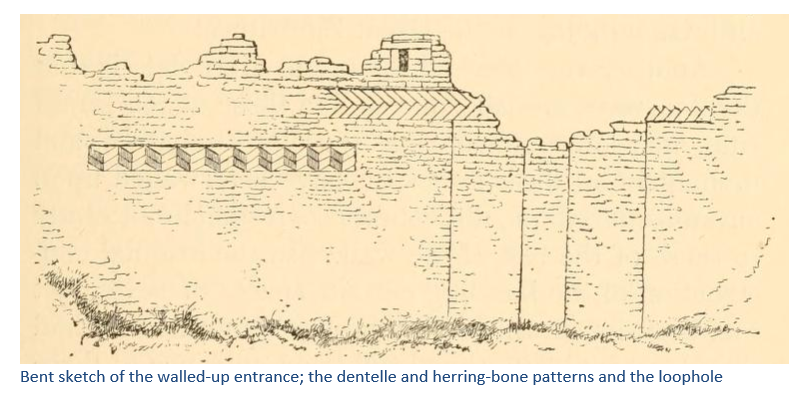

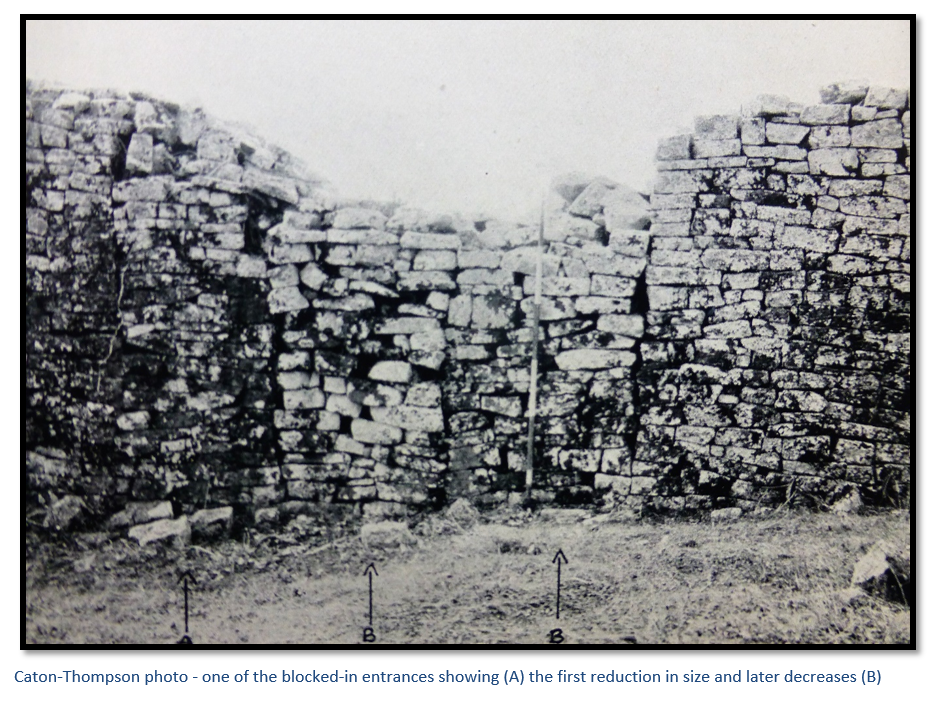

Bent contrasted the square-edged doorways as against the rounded doorways at Great Zimbabwe and noted that most had been fully or partially walled-up; originally 2.1 metres (7’) wide, they had been reduced to 0.91 metres (3’) with stone courses on either side. The relatively-straight lines of the inner enclosures are remarked upon, as are over forty circular stone hut foundations all outside the enclosure, but in close proximity. Bent also noted other smaller building structures halfway down the slope of the granite batholith with similar hut foundation circles and the associated quarry sites. Bent says: “I take it that the ruins at Matendere were constructed by the same race [i.e. as Zimbabwe] at a period of decadence, when the old methods of building had fallen into desuetude. [disuse]”

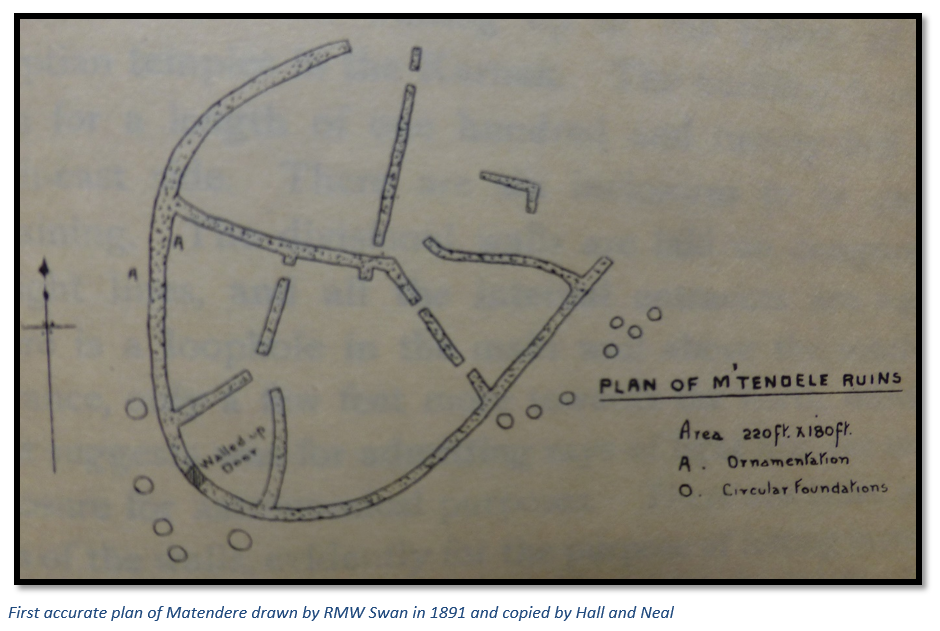

‘M’Tendele’ or ‘Matindela’ is described in Hall and Neal’s The Ancient Ruins of Rhodesia as the capital of the Sabi district although it is also clear their book indexer seems to have confused the M’Tendele ruins in Sabi with the M’Telegewa ruins on the Shangani River. They hypothesize that the foundations are contemporary with Great Zimbabwe, but that the walls are of a later period and inferior quality with rough masonry and irregular stone courses.

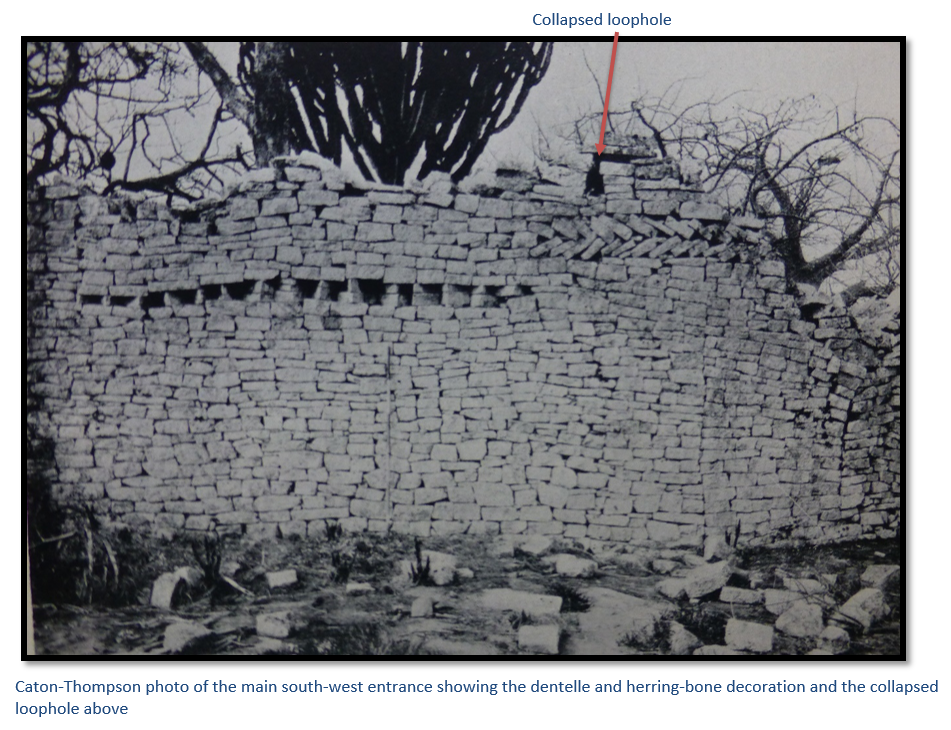

They define the shape of the walls as elliptical [horse-shoe] and massive and that the orientation of the most decorated section of walling is toward the setting sun. Mr Swan, the surveyor, appeared to be fixated on this feature in relation to the doorways: “three of them look east 25°north, and four east 25°south, thus corresponding to the direction of the sun rising and setting at the solstices.” He also suggested that a loophole above the main entrance was designed to admit rays of light into a temple enclosure for astronomical purposes.

They describe the wall ornamentation as: “herring-bone pattern extending six feet above the entrance, also herring-bone pattern for a length of forty feet facing the setting sun at the winter solstice, while a dentelle pattern faces the WNW, being two courses lower in the wall than the herring-bone pattern above the entrance. Herring-bone pattern in two lengths, one being thirteen feet, are on the inside wall of one of the enclosures and face the rising sun at the summer solstice.”

Like Bent they identify the stone quarry on the eastern side of the hill and describe the highest walls on the south-east as being 3.5 metres wide (11’ 6”) and 4.57 metres high (15’) The main entrance faces west-south-west with square edges to the walls. The enclosure is open on the north-east for 38 metres (120’) and there are six internal enclosures which are divided by comparatively straight walling and internal entrances.

They also identified the purpose of the holes in the tops of the walls were for setting up stone monoliths as at Great Zimbabwe. A terrace on the inside of part of the wall they compared with a similar terrace at Naletale Monument near Gweru and the circular 1.8 – 4.6 metre (6 – 15’) foundation bases of pole and dhaka huts at Great Zimbabwe and other sites.

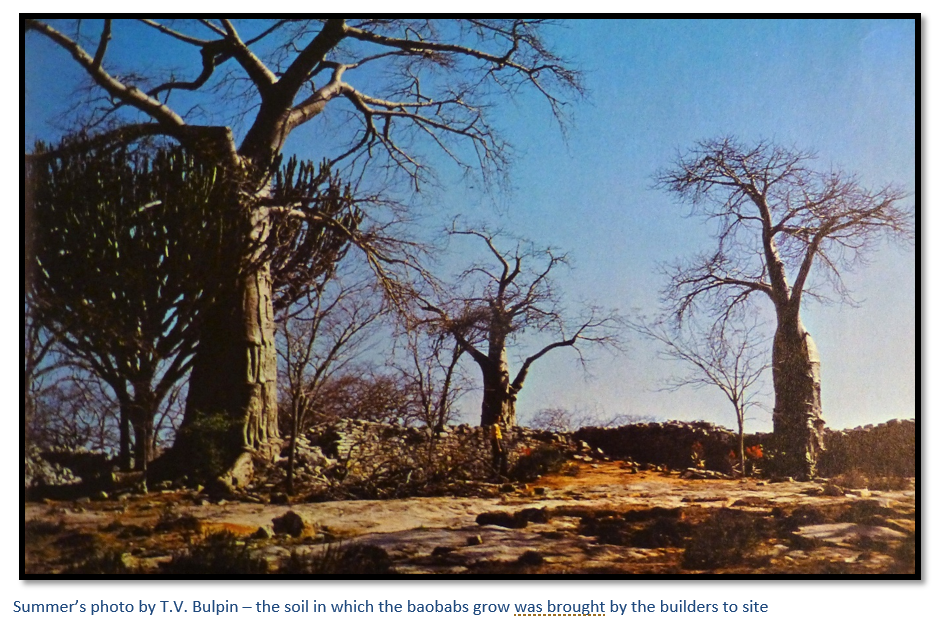

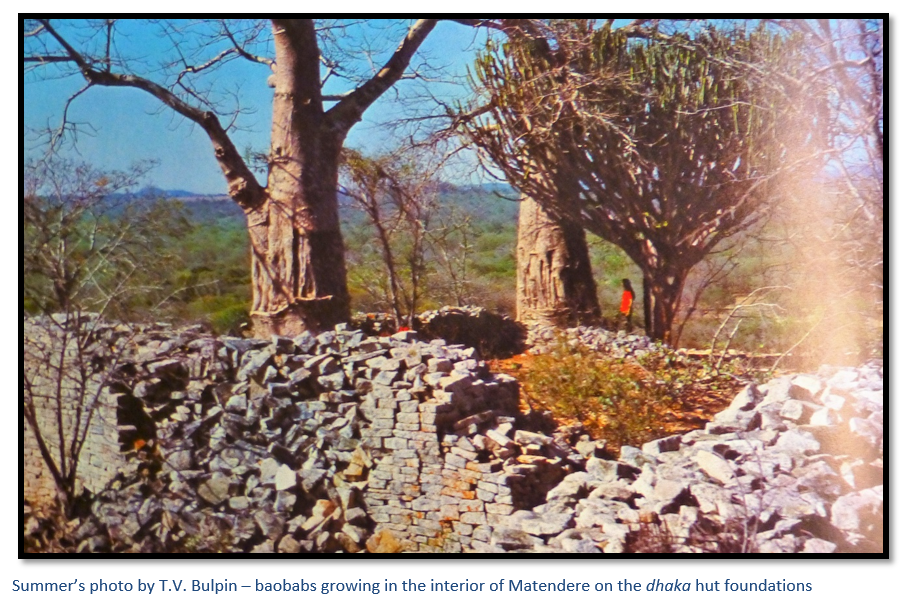

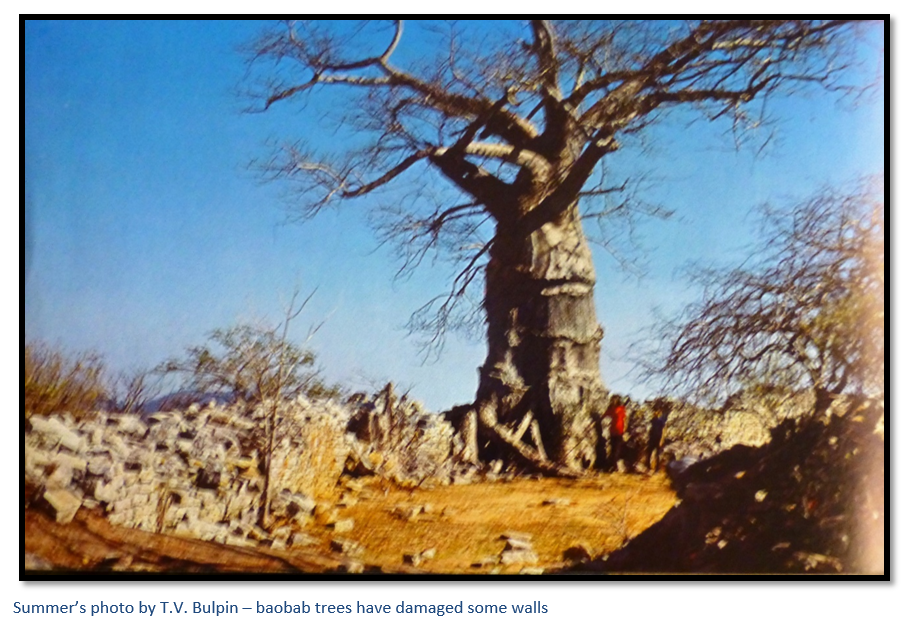

They also stated the presence of giant Baobab (Adansonia digitata) trees pushing up the walls indicated a comparatively recent date to the ruins, although we now know that Baobabs can live to a thousand years. Today the Baobab’s and Mopane trees are still growing around the Matendere Monument.

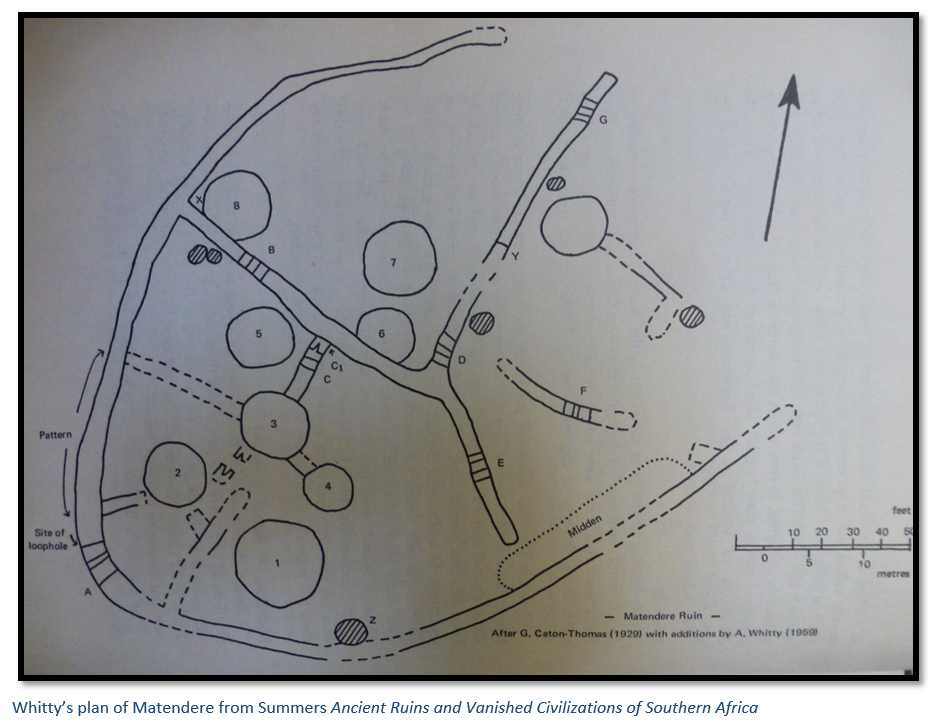

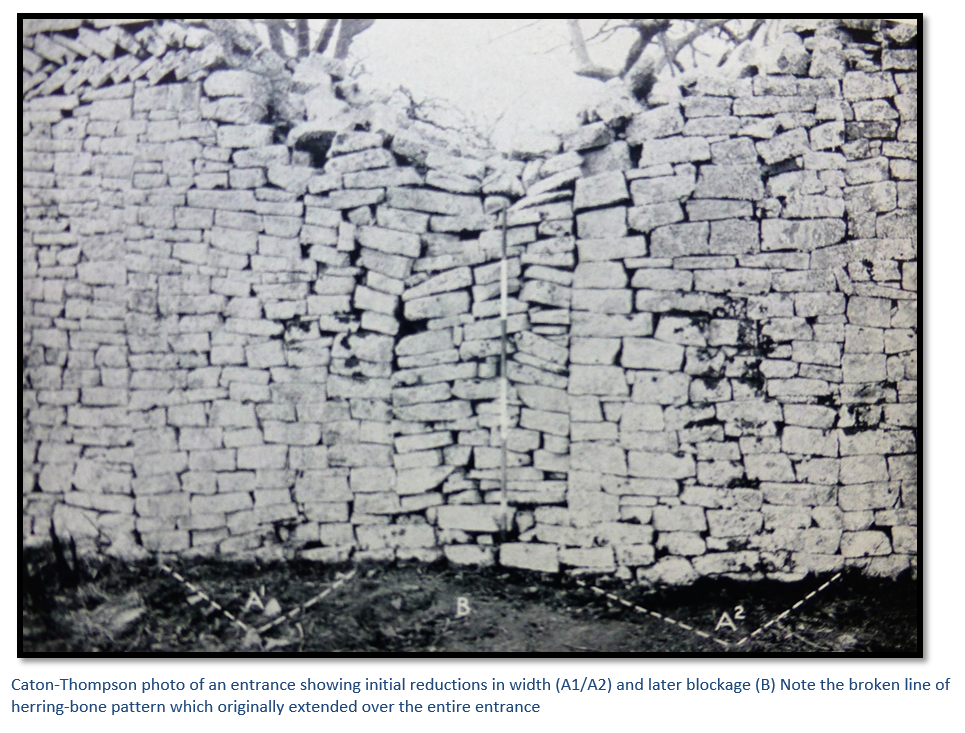

Gertrude Caton-Thompson made the first scientific excavation here in 1929 of a sample of middens (dumps of domestic waste) and hut debris. These were quite shallow, less than a one metre in depth, and she found plentiful glass beads, but little else of much significance. Caton-Thompson noted the alterations to the entrances; originally 3.5 metres wide, they were reduced to under one metre and in other cases, completely blocked up with rough stonework. The loophole above the entrance, unlike any other in the country because it was three times as high as its width, had been neatly drawn in Bent’s illustration, but now looked broken-down thirty-seven years later and is today unrecognizable.

Caton-Thompson was a trained archaeologist and began her work with an accurate survey of the site. She noted the stone came from exfoliated rock on the kopje and that the blocks were irregular in size and laid dry; the walls showed no batter [i.e. that were not wider at the bottom than the top] and the entrances were rectangular. The main wall which she called the girdle wall was 168 metres (550’) and in the form of an incomplete eclipse, or horse-shoe. The width of the girdle wall varied from 1.2 – 3 metres (4’ – 10’) and the narrowest and worst-built sections were at the extremities. The maximum height and width were at the south-west curve which were further enhanced by the dentelle and herring-bone patterns within the walling. She noted that at Great Zimbabwe the chevron pattern is like-wise in the highest and widest section of wall.

Caton-Thompson noticed that the baobab trees grew on the interior of the walls where there was an artificial earth floor about 60 cm (2’) deep had been created by the original inhabitants from the dhaka hut floors. She concluded that the open position and lay-out of Matendere made it useless as a fort, that it was probably a Chief’s kraal, less important than Great Zimbabwe, but built in the same tradition.

Within the north-west interior of Matendere she found the remains of circular pole and dhaka hut foundations in the form of low mounds of dhaka earth, the largest 7.6 metres (25’) in diameter, although most of the remainder of the interior is made up of bare granite rock. In trial trenches they reached bedrock at 60 cm; a thin layer of granite chips comprised the bottom layer, presumably stone-mason’s flakes and the dhaka above contained a high proportion of broken granite.

In the south-east interior they found the principal hut 10.4 metres (34’) in diameter with a dhaka base still 1.8 metres (6’) high, so she concluded that the hut may have overlooked the girdle wall at this point, and its position behind the main entrance, but to the right of the main wall was screened by a partition wall, now in ruinous state. Here Caton-Thompson had another trench dug into the hut foundation down to the bed rock but found no artefacts.

Further trenches were dug in the south-west area and inside of the main entrance, but only found imported dhaka and fallen stone blocks and one tapering granite monolith which had fallen from the top of the wall. Within the midden deposit, only 10% of which was excavated, and which consisted mainly of sooty ash, they found over a thousand opaque glass beads. Bright-blue beads predominated, followed by red and then cobalt-blue, black, yellow and apple-green. Nineteen circular copper and bronze beads were unearthed, some broken bronze-wire bangles and a quantity of rough pottery.

Roger Summers in his book Ancient Ruins and Vanished Civilizations of Southern Africa gives a summary of the final detailed examination of Matendere carried out by JAN Whitty, on behalf of the National Monument Commission in 1959. He noted the earlier foundations and the later raising of the walls to their current height. Whitty reasoned that the width of the entrances had been reduced to insert lintels so that the higher walls could be carried over the doorways. This was shown by the herring-bone wall pattern which appears on both sides and originally ran over the main entrance; but the lintels eventually collapsed, and the entrances were roughly blocked with stone as seen today.

In 1552 Da Barros, wrote Da Asia, the great history of the sixteenth century conquests of India and East Africa included this famous description from travellers into the interior of southern Africa. “…in the midst of a plain there is a square fortress, of masonry within and without, built of stones of marvellous size, and there appears to be no mortar joining them. The wall is more than twenty-five spans in width, and the height is not so great considering the width. Above the door of this edifice is an inscription, which some Moorish merchants, learned men, who went thither, could not read, neither could they tell what the characters might be. This edifice is almost surrounded by hills, upon which are others resembling it in the fashioning of the stone and the absence of mortar and one of them is a tower more than twelve fathoms high.

The natives call all these edifices Symbaoe, which according to their language signifies court, for every place where Benemotapa may be is so called; and they say that being royal property all the King’s other dwellings have this name.”

Da Barras added later: “When, and by whom, these edifices were raised, as the people of the land are ignorant of the art of writing, there is no record, but they say they are the work of the Devil, for in comparison with their power and knowledge it does not seem possible that they should be the work of man. Some Moors who saw it, to whom Vicente Pegado [who was Captain at the Portuguese fort at Sofala] showed our fortress there and the work of the windows and arches, said they could not be compared with it for smoothness and perfection. The distance of this edifice from Sofala in a direct line to the west is a hundred and seventy leagues, or thereabouts, and it between 20°and 21°south latitude. There are no ancient or modern buildings in those parts, the people being barbarians and all their houses of wood. In the opinion of the Moors who saw it, it is very ancient and was built there to keep possession of the mines, which are very old, and no gold has been extracted from them for years, because of the wars.”

Summers has a theory that although this description by Da Barras is often attributed to Great Zimbabwe, it might refer to Matendere Monument. He compares the description above to the Great Enclosure and believes, even after the natural inaccuracies of a second or third hand account, that Matendere matches the description better than Great Zimbabwe saying:

- Although the survey plan of Matendere is not square, from the outside it appears squarish.

- Standing in open country it may appear to be in a plain.

- The walls are thick and not being high, might appear to be almost square in cross-section.

- The row of herring-bone pattern originally above the door might appear to be the indecipherable inscription over the entrance.

- Matendere is surrounded by other dry-stone buildings and Muchuchu building complex, that is a platform building with retaining walls on the slopes of a kopje, may appear as a tower.

- The archaeological evidence shows that these buildings were all occupied at the same time.

- The stated position west of Sofala is approximately correct for Matendere, although there are no gold mines in the vicinity.

Whether or not the description fits, Matendere Monument sees few visitors through its remote location and deserves more recognition as one of Zimbabwe’s prime monuments.

Acknowledgements

R.H. Wood. Llewellyn Cambria Meredith, 1866-1942. Heritage of Zimbabwe. No. 16, 1997. 55-66

J.T. Bent. The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland. Longmans, Green and Co. 1895.

R.N. Hall and W.G. Neal. The Ancient Ruins of Rhodesia. Methuen & Co. 1902.

G. Caton-Thompson. The Zimbabwe Culture. Clarendon Press 1931.

R. Summers. Ancient Ruins and Vanished Civilizations of Southern Africa. T.V. Bulpin, 1971.