Fort Hill – the first site of Umtali (now Mutare)

The area, which includes the Indaba tree, was originally near the site of Chief Mutasa’s kraal at Bunga Guru where early prospectors and both the Portuguese and BSA Company had tried to win the Chief’s allegiance and permission to prospect for gold in the Penhalonga Valley.

The Portuguese had established a number of trading posts for gold, called Feira’s, within Mashonaland in the sixteenth Century and managed to exert some influence in the interior though the tiny establishments at Sena and Tete on the Zambesi River using a policy of divide and rule. In the area of Manicaland their authority rested on the powers exercised by a number of individuals including Manuel de Souza (Gouveia) a Prazo holder near Gorongoza Mountain. A Prazo was a large estate and Gouveia kept the local population subjected and terrorised with his armed followers. He was supported by Major Paiva d ’Andrada who had formed a commercial company, the Companhia de Mocambique to develop mining and commercial schemes in the what was considered Portuguese territory.Their company headquarters and interior base was at the fortified settlement of Massi Kessi or Macequece.

The Companhia was undercapitalised and decided to lease out mineral concessions to individual speculators who would carry out the commercial development and pay royalties. J.H. Jefferies in 1888 obtained a concession from the Companhia and formed a syndicate to carry out exploration. After many difficulties he and a small party of prospectors reached Manicaland and pegged gold claims in the Penhalonga Valley naming one after Baron Joa Rezende, the manager of the Companhia and the other after Count Penhalonga of Lisbon. Work began on mining in 1890.

On 3 September the Pioneer Column was making its way through southern Mashonaland and a small party under Colquhoun the appointed Administrator, and Jameson, the de facto commander, Selous and seven mounted Troopers left the Column for Manicaland. On 12 September, the same day as the Pioneer Column reached the site of Salisbury, now Harare, this small party minus Jameson who had been thrown from his horse and injured, reached the Mutare River and camped under a shady tree half-way up the hill slope near the site of the Bartissol Mine.

These representatives of the BSACo managed to persuade Chief Mutasa that it was in his best interests to sign a treaty that gave mining and mineral rights to the BSACo. Soon after, Fort Hill was established near the present site of Penhalonga to “protect” the Chief from the Portuguese. The buildings were too flimsy to survive, any corrugated iron roofing and doors and windows were carted away to Old Umtali. Nevertheless, Fort Hill remains an important part of Zimbabwe’s early colonial heritage.

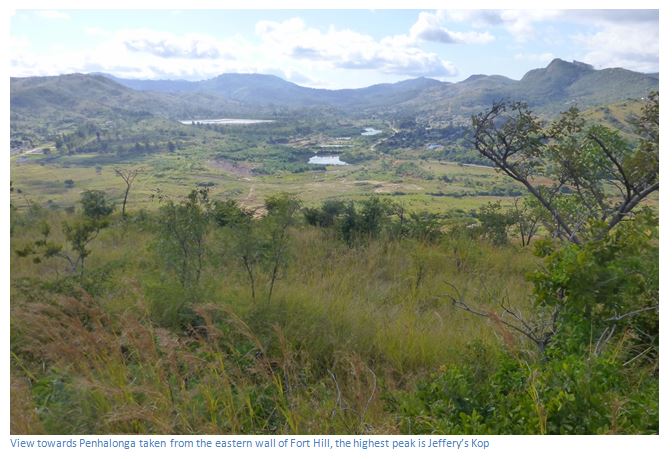

The remains of Fort Hill are still just visible, a square enclosure with an entrance on the north surrounded by a ditch. Inside is a hole 2 metres x 3 metres neatly lined with stones that presumably sheltered the ammunition. Excellent 360⁰ views are obtained in all directions and the first hospital site is within one hundred metres.

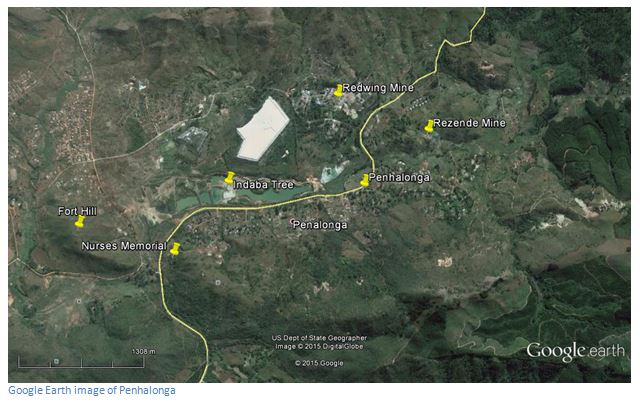

From Harare to Mutare on the A3 pass the A15 turn-off for the Nyanga Road. 2.2 KM later turn left before Christmas Pass at the petrol station on the road signposted for Penhalonga. Drive towards Penhalonga Village passing at 5.9 KM on the right the La Rochelle turnoff, 7.2 KM turn left for the untarred Fairbridge Road, crossing the narrow bridge over the Mutare River. 7.4KM go right at the fork, 8.6 KM turn left at the junction, 8.7 Km turn left and continue up the track towards the Hill, 9.1 KM turn right at the fork going up towards the water tanks on the hill; 9.4 KM reach the water tanks and park. A footpath zigzags about 200 metres up to the levelled area and then continues south onto Fort Hill.

For a local guide, I strongly recommend contacting Gary Goss in advance of your visit and meeting at La Rochelle. This is an artisanal gold-mining area and local people can be suspicious of visitor’s intentions and Gary is well-known and respected. Mobile 0772252001 or 0772249011

GPS reference: 18⁰53′02.51″S 32⁰39′00.06″E

The first permanent settlement of Umtali was at the camp site of the BSA Police in November 1890 when they came to negotiate a treaty with Chief Mutasa during the period that the British and Portuguese were struggling for dominance over Manicaland. Named Fort Hill, this settlement was located close to the confluence of the Sambi and Umtara Rivers and the future mining town of Penhalonga.

After months of political wrangling and threats matters came to a head in Manicaland at the battle of Chua Hill, close to the Portuguese Fort at Massi Kessi or Macequece when the BSACo Troopers under Captain Heyman were attacked on 11 May 1891 by a mixed Portuguese force under Colonel Ferreira and Captain Bettincourt. [Details to be given in a separate article] The border dispute with the Portuguese was resolved on 3 July 1891 by international agreement with the boundary at 33 degrees East and the confirmation that Manicaland was within the territorial boundary of the BSACo.

Three days later on 14 May 1891, Lionel Cripps, later Speaker of the Rhodesian Parliament, and a small party arrived at Fort Hill and together with all the prospectors present in the area and excavated the fortifications at Fort Hill with defensive walls and cannon emplacements. Nine Maxim guns taken from the Portuguese at Fort Massi Kessi presented a formidable appearance but were useless as the firing pins had been removed.

On 1 July 1891 the newly appointed Bishop of Mashonaland, Knight Bruce arrived at Fort Hill and together with Eustace Fiennes visited Chief Mutasa looking for land with good soils and water to establish a Mission. Land was granted by the Chief and later confirmed by the BSACo for 3,000 acres at the present-day site of St Augustine’s Mission.

Theodore Bent and Charles Finlason who wrote A Nobody in Mashonaland both visited Fort Hill as they left the country for Beira. The fort was at the highest point and approximately 200 BSACo Police were nearby in camp huts. The Police Officer’s Mess was furnished with items looted from Fort Massi Kessi and it was said that when the Portuguese Governor visited, he sat on his own chairs, ate off his own china and was served his own tinned meats, but was too much of a gentleman to make any comment! A hut near the Police camp served as the reading room where the most recent newspaper was 7 weeks old and the best chair was a bully beef case.

On another spur of the hill was the hospital and across the Mutare River on Sabi-Ophir Hill were the original huts where Mr Campion, Manager of the Sabi-Ophir Mining Company had given the three nurses and Dr Glanville accommodation when they first arrived on 14 July 1891 in one of his three pole and dhaka thatched huts. [See the article on the Nurses Memorial under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Just north of Fort Hill was a collection of huts and stores which included a butcher and very primitive hotel comprising three huts.

The location of the Fort Hill as a settlement had numerous shortcomings; it lacked level space, water needed to be fetched from the Mutare River and numerous gold mining claims had been pegged in close proximity, so the decision was made in December 1891 to relocate the settlement seven kilometres due west to the site of Old Umtali where the Methodist Church has now established Hartzell School and the Africa University…among the leading educational establishments in Zimbabwe.

After just seven years in 1897, Old Umtali was abandoned in favour of the present site of Umtali (now Mutare) to avoid an expensive diversion of the railway track over Christmas Pass and to line the railway up with its next big obstacle, the Odzi River. Old Umtali was moved lock, stock and barrel to its current site and today the Methodist Church occupies the site of Old Umtali.

Fort Hill today

There are steep slopes on all sides of Fort Hill, which occupies a plateau on the summit of the Hill, with extensive 360⁰ views of the Penhalonga Valley. The walls of the Fort are aligned slightly west of north in the shape of a square measuring 30 x 30 metres with the only entrance in the northern wall. The remaining walls have clearly collapsed, being just a metre high and two metres wide; they were undoubtedly revetted, or faced with timber lengths, which were long ago eaten by termites. It was common practice at the time to top the walls with sandbags to increase their height and to provide a level firing platform; sandbags are easy to transport empty and have been in use since the late eighteenth Century. There are the remains of a ditch around the walls, except to the north, where the ground is level around the entrance. No firing step is visible, and the corners do not have bastions, although all trace of them may have been washed away since 1890.

In May, the grass was thick and the ground features difficult to make out; but no timbers appear to have survived and no hut sites were observed within the Fort. In the south east corner is what appears to be an ammunition store in the form of a pit, lined very neatly with stone and about 2 x 3 metres in size and one metre deep.

Either graves, or hut sites are visible sixty metres north of the Fort entrance. I think they are more likely to be the scattered remains of huts, although some seem quite small. There is at least one recorded death on the site; that of the nurses’ first patient on 8th October 1891 with lung tuberculosis, but I believe he would have been buried at a suitable site away from the camp.

A cleared area of levelled ground is still obvious 100 metres north of the Fort and on the edge of the slope. The Nurses had arrived in mid-July 1891 and used one of three huts belonging to Mr Campion on Sabi Ophir Hill. The site proposed by Bishop Knight-Bruce for the Hospital had been declared unsuitable by one and all and in August the Nurses moved from Sabi Ophir Hill to four huts built for them on Fort Hill. This appears to be the most likely spot for these Hospital huts proposed by Colonel Pennefather and built by the BSA Company for the Nurses and completed by October. This site was abandoned after only four months in December when everyone moved to the Old Umtali site and all the huts at Fort Hill were set on fire.

The track to Fort Hill appears to have been up the easiest slope from the north and along the current track which follows the same route as far as a left dog-leg just 90 metres from the water tanks. From the dog-leg the faint remains of a track gradually ascend the hill on the western slope and probably this was the original route used by ox wagons and for the seven-pounder gun.

October 1890

C.M. Hulley writes in his book Memories of Manicaland that the Pioneer Column was officially disbanded on the 1st October 1890, soon after the flag hoisting at Fort Salisbury on 13th September 1890. Frank Johnson's contact with Rhodes thus expired and he decided to explore for a shorter route to the Mozambique Coast as the the route from South Africa was too long and costly, He was persuaded, against his better judgement to take along L.S. Jameson, Rhodes’ right-hand man.

It seems likely that Johnson and Jameson were amongst the first pioneers to reach Manicaland from Harare. They followed in the tracks of an ox-wagon driven by Morris, Human and Jack, a Zulu man. It took three days to reach Marondera from Salisbury, and Johnson states that the local people had never previously seen either a white man, or a horse, and seemed more interested in the latter. They had great difficulty in following the spoor of the wagon as it had been obliterated, which necessitated frequent halts to pick up the trail again.

They were happy to reach the mouth of the Penhalonga Valley and overtook their wagon near the Bartissol mining camp in the Mutare River valley at the base of Fort Hill and worked by Englishmen with a Portuguese licence. These prospectors were completely surprised when the wagon suddenly turned up out of the blue as they had heard nothing of the occupation of Mashonaland by the BSA Company. Johnson and Jameson’s subsequent adventure down the Pungwe River in a collapsible boat to Beira is hilarious and described by Johnson in his book Great Days.

Morris and Human had spent several days trying to find a possible route over the mountain for the ox-wagon, but came to the conclusion that, without weeks of heavy work, it was impossible to get over the range, so Jameson and Johnson hired carriers and followed the footpaths to Macequece (Massi-Kessi, now called Manica)

One of the first residents in the immediate area was A. Tulloch who came soon after the Pioneer Column had been disbanded. He travelled from Salisbury to Chief Mutasa’s kraal passing Patrick Forbes on his way back to Salisbury with his Portuguese captives. [See the article under Manicaland on How Mutare and Manicaland were seized from the Portuguese o the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

The BSACo encouraged prospectors into Manicaland to counter the Portuguese presence, but few stayed for long and most drifted back to Salisbury. Those remaining that had believed their gold claims had potential banded together into syndicates to begin mining. Tulloch’s claims were the Liverpool, Campion and Central Penhalonga and after staking his claims he returned to Salisbury to fetch his wife and borrowed a wagon from Frank Johnson to bring supplies back to Penhalonga

A month or two later, the BSA Police encamped at Fort Hill. At that time malaria was rife, there was no medical care and conditions were pretty bad. The Rezende and Penhalonga mines were being worked and soon the area became active with other prospectors. They pegged gold claims all along the Sambi and Umtara Rivers right down the Divide, in what is now known as the Penhalonga Valley. One prospector even pegged a claim and began to dig for gold in front of their camp!

The Camp Mess at the Fort seems to have witnessed some odd scenes, "What's your name?" enquired a BSA Policeman of a visitor. The rather terse reply was: "Damn", then the comment "I'm thirsty!" "That's not the way to behave here" was the retort. "Before I can serve you with a drink, I must know your name." "Damn" the man repeated, adding a few more profanities. "No drink for you unless you conform to regulations" warned the indignant member of the force. "Damn" emphasised the now rattled prospector for the third time. The Policeman, refusing to be insulted by an old disreputable prospector, tried to push him out. A fight ensued, "Hold on" cried a sergeant as he entered the room, "What's up?" "This fellow refuses to give his name and only curses, saying “Damn.” "I know him, his name is George Damn, as a matter of fact". There was instant laughter and all was forgiven.

July 1891

Although many of members of the Pioneer Column were disbanded after 1st October 1890, about 200 BSA Police were stationed at Fort Hill following the tension with the Portuguese over the territory of Manicaland, forming the largest concentration of men on the eastern borderlands.

Much to the surprise of these men, three Nurses arrived unexpectedly, their destination being Sabi Ophir Hill, directly opposite Fort Hill across the Mutare River. They were even more amazed when they were told that these women had walked 140 miles (225 kilometres) from M'Pandas Kraal on the Pungwe River, arriving at Penhalonga on the 14th July 1891. Their promised transport had not arrived and there is scarcely an account of the early days which does not mention these women with affection and admiration. They were Nurses Blennerhasset, Sleeman and Welby. The arrangements to proceed to Rhodesia from South Africa had been made by Bishop Knight-Bruce, who had accepted the charge of the missionary diocese of Mashonaland. The Nurses’ only European companions had been two young Englishmen, Dr Doyle Glanville and Walter Sutton, who knew no local languages and were absolutely new to the country. On the last stages of their journey the carriers deserted them, and one man was left behind to guard the luggage which was retrieved later. The Nurses remarked: "It was a freak of chance that we ever arrived at all".

Their book Adventures in Mashonaland records their last day in Mozambique after leaving Massi-Kessi (Macequece, now Manica): After quitting the fort we lost our way, and had to encamp in a wood early in the afternoon, whilst our boys went to a kraal some miles distant to obtain what information they could about the way to Umtali. The next day we set off early, and hoped to reach our destination after a few hours’ walking, we were obliged to make a forced march, because our provisions had run short. There was indeed nothing left but a little tea and half a pot of Bovril.

This was the hardest day of all. A bad rocky path, hill after hill to climb, valleys and ravines to cross, burning heat; and, worst of all, for some hours we could find no water. Even the boys, who seem made of iron, began to lag. As to Sister Aimée [Rose Blennerhassett] she looked half dead. I was terribly anxious about her, feeling sure she must have fever, for, as I took her hand, her skin seemed to burn me. When we did finally reach Umtali her temperature was 105⁰…At last we came to a stream, where we bathed our faces, rinsing out our mouths, as we did not dare to drink much in our heated state. Much refreshed, we longed to light a fire and make some Bovril, but there was no wood to be found anywhere near, so we had to go on.

After another couple of hours’ walking, we came to a larger stream in a grove of bananas, and here we halted and made some soup. This revived us somewhat, we felt able to make a fresh effort. Then there were more hills to climb, more valleys and ravines to cross, interspersed with long stretches of tall grass, which after a time had a most bewildering dizzy effect. At last towards sunset, Dr Glanville descried a distant flag – Umtali! [This was the flag on Fort Hill] The sight of that flag gave us new spirit…Half an hour’s quick marching brought us to a small river. As Sister Aimée was scrambling over a fallen tree, which served as a bridge, a hand was suddenly stretched out to help her. It was the Bishop! [Bishop Knight-Bruce] He looked extremely well, and welcomed us warmly. He had only received our note an hour or two before, and was preparing his hut for us. He was horrified to find Sister Aimée so ill; indeed, by this time it was all we could do to get her up the steep hill, on the top of which the Bishop was then staying.

All they found when they arrived on 14th July 1891 were three small huts belonging to Mr Campion, the manager of the Sabi Ophir Mining Company. The three nurses occupied one; Mr Campion occupied another and the Bishop the third, with Dr Glanville in a tent. The encampment was perched on the top of a steep, rocky hill, and in the space in front of the huts an enormous tree of the fig species spread forth its branches. This was the only large tree in the whole district, and Sabi Ophir Hill was known to the natives as the “hill of the great tree.”

Bishop Knight-Bruce had decided he did not have the resources to build an Anglican Mission hospital, but hospital huts were built on a site adjoining the Police Camp by the BSA Company. These were ready on 22nd September with their first official patient arriving a few days later. Dr Glanville appears to have suffered a nervous breakdown and was “talking foolish”. When he had recovered, Captain Heany, who was making roads, asked him to take some of Sir John Willoughby’s horses to Salisbury, but he died of fever within a few miles of reaching his destination and was buried in the veld.

Bishop Knight-Bruce had picked a site for the new hospital a little over 3 kilometres from Sabi Ophir Hill and the three nurses describe: descending from our eyrie, and crossing by a slippery pole a rapid torrent which rushed at the bottom of the hill, we wound along, passing beneath the height on which the Police camp was pitched. The Bishop was with us, and he was amused to see all the natives who were working in the camp tear madly down the slope with a view of catching a glimpse of the ”m’lungas,” or white women…leaving the camp behind we hastened on after our guide; crossed one or two streams on stepping stones; climbed a height or two, and at last found ourselves on the summit of a grassy slope, backed by towering rocks and thick bush, were our huts were to be built. Already poles and grass for one hut were cut and ready for use.

Lieutenant Eustace Fiennes reminded them that the innocent-looking brook [the Mutare River] they had slipped over so easily became a raging river in the rains and would cut off the hospital from the police camp for days on end. The only doctor [Dr Lichfield] lived in the Police camp and all their supplies and provisions came from there. Fiennes thought it quite impossible for three women to live alone here, over 3 kilometres from the doctor, or any help. If a patient became worse in the night, no native would be persuaded to cross the veld and call Dr Lichfield with lions roaming about.

They spoke to Captain Heany who persuaded the diggers and traders at Penhalonga to have nothing to do with the hospital if it was built on the proposed spot and would build one themselves. A subscription list was opened and a considerable sum of cash sent over next day. Then Colonel Pennefather, OC of the BSA Police arrived, and came across to Sabi Ophir Hill. He proposed a spot near the Police camp for the Hospital huts which would be ready in a few weeks.

The nurses meals consisted of meal and ox meat, their cooking utensils were a three-legged pot and a frying-pan and with no baking powder, or yeast, the meal turned into “the most horrible half-cooked flat cakes.” Another venison meal cooked with sardine oil to which Mr Campion was invited turned out a culinary disaster and was abandoned to their servant.

Their luggage had been abandoned at ‘Mpanda’s, and when Captain Heany sent down oxen and ox-wagons to bring it up, rumours began to arrive of all the oxen dying. East Coast fever had arrived, spread via the brown tick. Many transport riders such as Stanley Hyatt found themselves bankrupt; “with their wagons abandoned on the veld, abandoned beside the bones of their dead cattle.” Just before the outbreak Hyatt and his two brothers owned some six thousand pounds worth of property; a few months later we were just able to pay our fares out of that miserable country.”

The nurses say digging and prospecting went on everywhere with gold reefs discovered in every direction. No one talked of anything but “booms, shares, quartz carrying visible, and the prospect of finding alluvial fields.”

August 1891

The nurses moved from Sabi Ophir Hill to their four new huts one hundred metres from Fort Hill which the BSA police officers furnished with the spoils from the battle of Massi-Kessi including a table, chair, a pair of candlesticks, and treasure of treasures – a bath. The walls of the huts were concealed behind blue and white calico, and the earth floors covered with reed mats. Their encampment was surrounded by a low wall of loosely piled stones, which did not prove animal-proof, as a hyena got into their store hut. There were no doors, just a hanging reed mat, which they say kept them awake many a night listening to the strange, uncanny noises of the veld.

The Tulloch family arrived at this time from Beira with their two children who had come in machilas, Mrs Tulloch and the children having a slight attack of fever. They were the first European children in Manicaland.

The Nurses say the BSA Police officers kept them from starvation, although meat rations often did not come, or were inedible. Every prospector who came to visit brought a present; either a bake-pot, or bananas, or honey and Eustace Fiennes, who had some cows, often sent milk. Part of the food shortage problem was that for traders the commodity that sold best was whisky; it could be bought for 15 shillings for a dozen bottles and sold for 30 shillings a bottle. Food was just added to the carrier’s loads to make up their agreed weight. So at one time, nothing but tinned sardines could be bought, and then tinned lobster, followed by foie gras. For a week or two, the whole of Manica breakfasted, dined and supped on foie gras.

The nurses were afraid they would miss the hunter F.C. Selous, but he sent word he would come as soon as he could get his shirt washed! The stories he told of his adventures he did so with charm and modesty, and they say his name was always associated with honesty. Selous left them with a bundle of newspapers, which they enjoyed since they had no letters since leaving Cape Town in April and he searched his wagon to fill their empty store room.

They describe the hardship for all of having no books, or newspapers, which resulted in the prospectors drinking too much and they say that two-thirds of them were always drunk at that time. Drinking bars flourished and were run by Jewish traders.

September 1891

One hospital hut was nearly finished by the 22nd September and on the same day Captain Heany’s wagons arrived from Chimoio bringing all of Sister Welby’s possessions, a small box belonging to Sister Sleeman, but nothing came for Sister Blennerhassett with the route from ‘Mpanda’s to Umtali marked by abandoned wagons and broken and rotting packing cases.

Their first patient arrived on the 26th September, an elderly man with lung tuberculosis and he had to stay in his tent pitched just outside the hospital area. Dr Lichfield told them to give their patient dinner of “whatever we had going” but they only had stodgy cookies; so the Police sergeant’s mess sent over a huge plateful of not over fresh tinned lobster. Sadly, he died quite soon after.

Because nobody would take responsibility in ordering “hospital comforts” the hospital opened with two or three iron spoons, two tin mugs, a couple of pots of Liebig’s extract, and a packet of Maizena from which they made excellent blancmange.

Then Dr Jameson arrived, “Dr Jim”, upon whom the nurses vented a good deal of irritation. Dr Jim said they had come up a year too early, but now that they had arrived, he must try and find them patients; whereupon they denounced the muddle of the BSA Company’s affairs and the amount of whisky which was being imported. A BSA police officer who accompanied Jameson said: “Jameson went into that hut a man, and came out a mouse.”

But the nurses say that he did not bear malice; only revenged himself generously by making every arrangement for the hospital and nurses by ensuring the BSA Company and not the Anglican Mission took responsibility for them, ensured they had all they needed, and paid their bills without a murmur.

Because the nurses were afraid of going up and down the hill at night, they would sit in the porch of the hospital hut, the sleeping patients would be their company, and the night seemed to pass more quickly.

October 1891

On the day their first patient died on the 8th October; Bishop Knight-Bruce called to say goodbye as he was going to raise money for the Anglican Mission in England. That same day Rhodes arrived, but did not stay in the Police Camp, but with Captain Heany. As he was not staying more than two days, they did not expect to see him and were surprised to see Rhodes riding up alone to the hospital hut. He came in and sat on a box and asked for pen and ink saying he would give them a cheque at once for the hospital. “Would £100 do? Amply, they said. Well, he thought he had better make it £150.”

The nurses were charmed by his simple manners and boyish enjoyment of a joke. He remained with the nurses a few hours, chatting delightfully and left promising to see them through all their difficulties. Their medical library had been lost, so he ordered replacement books from England.

The same day they learned that the whole township and hospital were to be moved eight kilometres to a more favourable site where the Old Umtali Mission is now situated. The move started soon after, Eustace Fiennes camped over at the new site and began building the new Police camp, nurses’ huts and hospital. The last was a square building with a small operating room in the centre with wards both sides and capable of holding between twenty to thirty patients.

For the nurses, the change could not come soon enough, as the existing hospital hut, despite the use of umbrellas and waterproof sheets, leaked terribly and their own huts were beyond repair. During the rains they huddled together in the centre of the best hut in an area of about a metre square, the floor like a swamp.

Their last visitors that rainy season were Mr and Mrs Bent who had carried out a dig at Great Zimbabwe and Mr Swan, a surveyor. Theodore Bent thought the buildings at Great Zimbabwe were a temple and fortress and were ancient in origin and built by foreigners, a view originally proposed by Karl Mauch in 1871. F.C. Selous differed completely in his views, saying they were comparatively modern and built by local Africans.

December 1891

The journey from Fort Hill to the new hospital at the New Umtali site, a distance of eight kilometres, took place in the middle of the rainy season. Their furniture was tied to an ox wagon with strips of cow hide called reims and the nurses moved off with their huts at Fort Hill being set afire. Their new servant, “Jonosso,” a Malay, said: “where does your Excellency wish your Excellency’s plate to be packed?” This plate comprised six teaspoons the nurses had brought with them, plus a few cheap steel forks and was kept in a biscuit tin that Jonosso, in a long blue shirt which reached his calves, white and scarlet striped trousers and scarlet fez, carried on his head as proudly as any English butler.

They reached the site of Old Umtali about midday and took shelter from the rain in Fiennes’ hut. Hours passed and no wagon appeared until a young boy reported it had been upset in a water-filled “donga.” Fiennes and his troopers patched up the wagon and brought it in before dark; but their tea was now soup, their meal was dough and their precious packing cases reduced to firewood. Happily their blankets were dry, so they lit a fire in the kitchen hut and slept in their blankets on the floor.

The next day was devoted to getting their huts and new hospital into order. They replaced the patients beds made with sticks and straw for mattresses with canvas stretchers and Nurse Lucy Sleeman made tables. They also had help from a Bavarian prospector who had been sentenced to a fine and three months imprisonment for shooting his servant in the leg. He was marched to the hospital from the gaol each day and wore the usual flannel shirt and miner’s trousers, but with large green arrows painted on them. Whenever he stood in the sun, the paint melted and ran down his clothes leaving a green puddle on the floor.

Algernon Caulfield helped out; turning a packing case into an arm-chair, which when covered in turkey twill looked like it had come from Maple’s, the furniture suppliers to the aristocracy and royalty.

Major Arthur Leonard

Arthur Leonard left Salisbury on the 20th October 1891 with three others and a scotch cart to carry their luggage. Leonard has already described how on their ride from Fort Tuli to Fort Charter, they met strings of empty ox wagons returning from Salisbury carrying parties of discharged and dissatisfied BSA Police who had little to say in favour of the BSA Company, or the country.

Leonard was incensed on his last night at Salisbury when it was customary to dine at the Police Mess, as Forbes at the instigation of Colonel Pennefather, asked him to dine out to make space for Rhodes, Jameson and Lord Randolph Churchill. When he returned to bed he could hear the conversation they were having in the dining-room over the Manicaland question. Leonard gained the impression that after Captain Heyman’s fight at Massi-Kessi, when he defeated the Portuguese, Rhodes felt he should have pushed on and captured Beira, but in Jameson’s absence the Administrator, Archibald Ross Colquhoun, would not make the decision.

He says he walked almost every mile of the way from Salisbury to Umtali on an uneventful, but one of the most enjoyable trips he had ever experienced – “one long and delightful picnic” through a perfectly beautiful country, magnificently watered, prettily beflowered, well wooded and splendidly adapted for grazing and agriculture

They arrived in Umtali on the 30th after a journey of ten days and he described the scenery of the last thirty kilometres as simply superb. Fort Hill he says is not as big as he expected, and in a bad location. Old Umtali to which all were about to move, he describes as an excellent site, with charming surroundings. Next today with Maund, Williams and Sauer they looked at some gold properties, especially the Sabi Ophir mine which had a 2 metre-wide quartz reef and a ten metre shaft; the prevailing opinion being that the gold field will be a great success.

He and Molyneux left on the 2nd November for Massi-Kessi at dawn. At first they walked through low-lying marshy country, but after two stiff and steep climbs they were in grass-covered, rugged hills, full of crannies and clefts, in which grew bushes and trees, while wild raspberries and plantains were common. The little mountain streams, with icy-cold water remind him of England and besides one under a large tree they rested and breakfasted, until suddenly one of the group looked up and saw a snake above their heads which they quickly killed.

They continued their walk passing through picturesque scenery which changed into beautiful wooded hills halfway to Massi-Kessi. He describes lovely colourful orchids and shrubs covered with flowers, before arriving at Lorenzo’s store, a poky little mud and wattle shanty, where for lunch they had tinned salmon and hard biscuit washed down with Vino Tinto wine. In the evening they crossed the Revue River and soon came to Massi-Kessi, having walked 34 kilometres that day.

The Fort belonging to the Mozambique Company he found to be a square with walls about 160 metres long, 2 metres high and 35 centimetres thick with a large well-built bungalow, two huts, a store and some ruins; but no guns, or troops. Next morning Leonard tried to get carriers without success, but he met Williams and Sauer again, who offered some of their own and they left together on the 4th November.

Acknowledgements

C.M. Hulley. Memories of Manicaland. Published by C.M. Hulley, 1980.

J.C. Barnes. Fort Hill. Zuro 1972. The Magazine of The History Society, Umtali Boys High School.

J. Bekker and E. Smith. Early Days in Umtali 1888 – 1898. Zuro 1971. The Magazine of The History Society, Umtali Boys High School.

R. Blennerhassett and L. Sleeman. Adventures in Mashonaland. Books of Rhodesia Volume 8, 1969

A.G. Leonard. How we made Rhodesia. Books of Rhodesia Volume 32, 1973

Darrel Plowes, Gary Goss and John Meikle for assistance in finding the site