Home >

Manicaland >

Dr James Johnston’s account of a journey across Africa (Part 5 of 5 - From Massi-Kessi to Chinde via the mission stations of British Central Africa Protectorate, present day Malawi)

Dr James Johnston’s account of a journey across Africa (Part 5 of 5 - From Massi-Kessi to Chinde via the mission stations of British Central Africa Protectorate, present day Malawi)

13 July 1892. They leave Massi-Kessi going east for 175 km (108 miles) because there has been recent fighting by the direct route between Gouveia and Makombe, in which Gouveia[i] was killed and the area is still disturbed. Travel on the pathways is different from trekking with oxen. They leave at 7am and walk for about 16 km (10 miles) and then a two hour stop for breakfast before continuing another 16 km before sundown. Huts are not built at night, but good fires are kept burning as lions are plentiful throughout the area.

16 July. They arrive at Chimoio and barter red white-eye beads, salt and handkerchiefs for supplies of rice and mealie meal. “There is no very distinctive tribal mark among the Manicas and coast natives, except that the men have the lobe of both ears slit and in the hole carry their snuff-box, generally, the empty shell of a Martini cartridge. The women have the upper lip pierced and insert a lead or silver plug with a flat round top on the outside, like a reversed collar stud.

We are now in the tsetse-fly belt. We passed 17 wagons today that had been left to their fate on the veldt for several months - the result of a rash venture on the part of a company to transport goods from Beira up to the interior. The ‘fly’ killed off the oxen, numbering some 400 and valued at £7 each, and so the wagons, of an average value of £130 had to be abandoned. Most of them are now so dilapidated and scorched by bushfires that it would not pay to remove them.”[ii] [For further details see the article Henry Borrow, after whom Borrowdale is named on this website under Harare]

Johnston quotes several pages from Bent’s book The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland and appears to revel in the failure of Johnson, Heany and Borrow’s attempts to establish a Pungwe route from Beira to Mashonaland.

19 July. The expedition crossed the Pungwe here at Mabute[iii] – the river is about 90 metres (100 yards) wide in a dugout canoe. He writes: “They prepare a very superior bark-cloth by cutting from a sort of fig tree large felt-like masses of the bark. After soaking it in water for a short time it is hammered with wooden mallets on a smooth log. When it is beaten out quite thin and all the holes neatly mended by the aid of a very primitive native needle and fine fibre, it is again beaten with a mallet on which lines are cut, giving the finished cloth a ribbed appearance. If the portion of the tree from which this layer of bark has been taken is found up tightly with plantain fibre, a new bark forms in process of time.”

They have been ascending since crossing the Pungwe river three days before and follow the base of Gorongoza Mountain before beginning to descend. “Water is plentiful and we come across villages every few miles. On the plains to the east buffalo, eland and zebra are to be found in great numbers, but they keep clear of the hills.”

21 July. They wade across the Kulumadzi stream that flows south-east having walked through thick forest for five hours and now emerge into more open plain with Gorongoza Mountain behind them.

Next day after crossing the Nymandura river they reach Gouveia village. The Portuguese representatives give them a crumbling hut for accommodation and the carriers are given the day off to see their relatives.

24 July. The expedition continues, though water is scarce and only obtained by digging in a dry river bed. “We saw at a long distance large herds of antelopes. Everywhere there is evidence of plenty of game, including elephant; but as the season for grass fires has begun, the larger animals have been driven east. In another month the young grass will be springing and they will return so that here we have one of the finest hunting-grounds in Africa within ten days of the sea.”

We passed several small villages during the day, but all deserted, owing probably to the scarcity of water or perhaps the late war.[iv]

26 July. “By noon fever came on. I stopped at a village to buy meal for the carriers. Again a headman brought out a fine large basketful of meal as a present to the white man. I gave him a jack-knife in return. The afternoon march was very hard; what with the hot fever and not a drop of water for fourteen miles, it was no play. The men were crying out for meat, but exhaustion compelling me to lie down by the wayside every mile or two, I was quite unable to go into the bush after game. Fortunately, however, I sighted a fine buck grazing about 150 yards from the path. On raising my rifle, my hand shook so much that I had to lean against the tree to steady myself. I fired one shot and dropped him but had to leave the carcass in charge of my gunbearer until the men should come up, for my mouth and throat felt as though it would be a case of spontaneous combustion if I did not reach water soon. At last we arrived at a village where a native took me to a hole five feet deep, dug in the sand, with about half a gallon of water in it. Not very nice, but never more appreciated.”

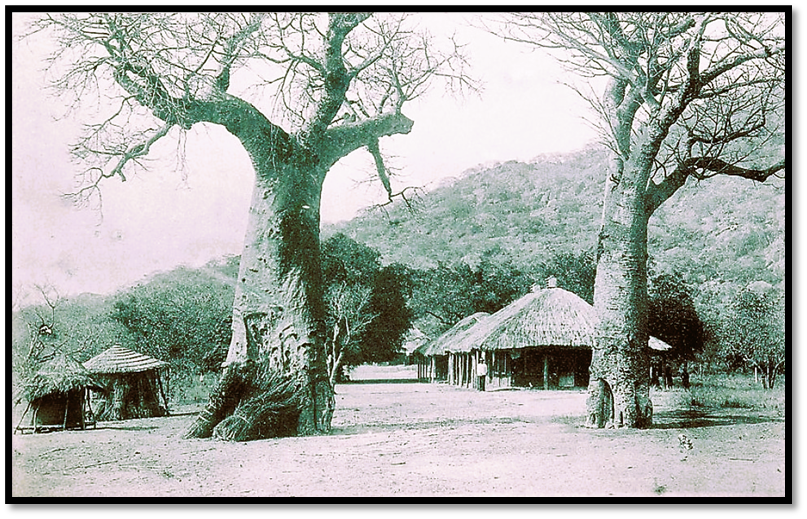

27 July. He says another thirsty day, but the scenery turns from rough, sterile country into “a perfect panorama or a beauty with numerous fine palms and gigantic baobabs.” They yield cream of tartar which is good at alleviating thirst. Another large acacia tree, called by natives ‘njerenjere’ is used for making paddles and also for producing fire. They bore a small hole in the wood, add kindling and then twirl a stick inside, the friction producing fire.

About sundown, we reached the village of Inyamacambe, named after the daughter of the late Gouveia. The chief brought us some lemons and a basket of lovely, sweet oranges, the first we have seen in our journey. I noticed with great pleasure a clump of lordly mango trees, all in full bloom, making me think of Jamaica as these were the first I had seen since leaving home.

From Sena to Blantyre

28 July. They reached Sena in the afternoon after 15 days of walking from Massi-Kessi averaging 32 km (20 miles) a day. “Sena has evidently been a very important Portuguese settlement in days gone by. It has a large, strongly built stone fort, impregnable to hostile natives; the fine old arched gateway, the stones of which are time-worn for an interesting specimen of ancient masonry. The town itself is very scattered and consists of the substantial dwellings of some sixty Portuguese inhabitants and several trading stores.”

The Sena governor invited Johnston to stay with him and treated him with great kindness although he did not speak English and Johnston spoke no Portuguese. “He had a number of slaves in his household and, so far as I could see, treated them with much more consideration than some people do their servants. We have seen natives both here and at Massi-Kessi in stocks and goree-sticks, although not chained together in gangs, as described by Sir John Willoughby; nor were they ordinary slaves or labourers, but convicts undergoing sentence for gross crimes—poisoning, assassination, incendiarism, etc.”

Travel by river

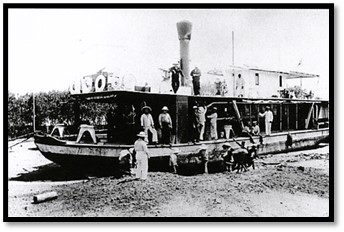

He charters for ten days a riverboat 9 metres (30 feet) long and 1.8 metres (6 feet) beam with a comfortable little cabin. The crew consists of 12 marineros (paddlers) a patrão (steersman) and kadamo (pilot) We left on Monday morning and after two hours rowing turned into the Ziwiziwi but moving slowly with the many sandbanks in the river.

“I shot two crocodiles with explosive bullets hitting them right behind the shoulder as they lay on the sand. One measured fifteen feet six inches, the other fourteen feet. By 10am on Tuesday morning we came out on the Shire River and headed upstream. There is apparently little difference in size between the Shire and the Zambesi; the current of the former, however, is the stronger. There is nothing to be seen of much interest, except the crocodiles, some of them monsters; a hippo now and again shows himself, but they are fewer here now than in former years, the steamers having driven them higher up. For two days the land on either side has been low and swampy, with reedy banks and very malarial.”

3 August. At Port Herald, soon after leaving they pass the river steamer ‘James Stephenson’ stuck fast on a sandbank. In another 24 hours they are at Chiromo,[v] at the confluence of the Ruo and within British territory having travelled 160 km (100 miles) in four and a half days. I have had no trouble with the men and this has been my experience with all the porters or boatmen employed from the Portuguese. They are well trained, hard-working and obedient.

He stays he had no sooner stepped ashore than a customs official asked: “Any firearms, Sir? Yes, I replied. An express rifle, a fowling piece and a revolver. Must leave them all here until you obtain a permit from the administrator, HH Johnston. And where might he be found? In the Shire Highlands, five or six days from here.” To wait 12 days for this permit was out of the question, but he also wasn't keen to continue unarmed as the country was full of leopards and lions. He protested, but the customs official would not budge; nothing to do but wait.

Chiromo is an important government station with a customs house and post office. The English occupied the north and the Portuguese the south Bank of the Ruo river and the two British gunboats, HMS Herald and Mosquito were moored here.[vi] He had an evening on board HMS Herald at the invitation of Commander Robertson.

HMS Mosquito beached for maintenance HMS Mosquito and HMS Herald moored near Chiromo

He stayed with Mr Simpson, a Scots trader with a large native store who promised to get carriers for the next stage of the journey to Blantyre. Simpson complained bitterly about the administration of British Central Africa – now incorporated with the British South Africa Company – saying that the bullying manner of Her Majesty’s Commissioner has alienated many of the chiefs. Every male native over 14 years old must pay a tax of six shillings per annum compared with the one rupee demanded by the Portuguese.

9 August. The expedition left by 11am, the way being rough going through long grass and thornbush. Mona was passed at 2pm and they reached Masanjeras by 5pm where Johnston stayed the night with a trader who offered shelter.

They continued walking the next day on a narrow path along the base of Tyolo Mountain and spotted large herds of buffalo and waterbuck. The valley is thickly populated and at Mbewe, close to the Shire river, they were cheerfully greeted by the chief.

That night at their camp on the riverbank, he says there was no sleep with the hordes of mosquitoes, frequent barking of leopards and growls from lion and the constant snorting of hippo!

At daybreak they continued along the Shire riverbank and reaching Katunga about 9am and the buildings of the African Lakes Company. The manager, Mr Baird had collected carriers but by the time they were assembled it was late and they stayed overnight.

Starting early, they began climbing into the hills up a fairly good road and began getting good views of the Shire Valley. At 3pm they passed the store of the African Lakes Company at Mandala and arrived at Blantyre.

Blantyre

Here he met Dr Scott, who introduced him to the missionary in charge, Rev Heatherwick. He says the magnificent church, the substantial and home-like residence, the crowds of boys and girls being trained by the mission have all been so well and frequently described that a detailed sketch of them is unnecessary.

Brick making at Blantyre

There was disappointing news in that the company’s steamer SS Domira would not be down to the south end of Nyasa for some ten days.

African Lakes Company SS Domira

This is disappointing, but cannot be helped, as I must go and see the stations on the famous lake before returning home.

I visited Mandala, headquarters of the African Lakes Company, where a large native trade is carried on and through whom supplies are forwarded to branch stations and to the various missionaries on the lake. There are rumours of the fresh disturbances in the east and north of Lake Nyasa; Johnston writes the hostility of the Arabs is very bitter and they are all too successful in winning over the numerous chiefs to their side in opposing efforts to stop the slave trade. To this may be added, as a reason for discontent, the maladministration of Her Majesty’s commissioner.

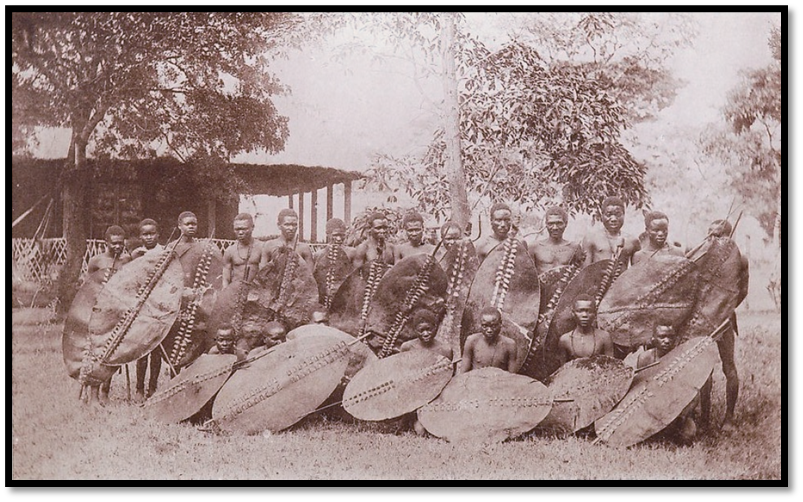

Angoni slave warriors

The grounds around the mission are very fine; much has been done in planting trees of eucalyptus, cypress, fir, etc. by a Scots gardener who has been here for many years. I visited the little cemetery nearby, the last resting-place of some twenty-three white people who have died here in almost every instance from fever. One grave, that of a man named Henchman, suggested a terrible lesson to those fanatics, now so numerous, who have either come or intend coming to Africa as missionaries on the ‘faith alone’ plan. He continues in the same vein for several pages, perhaps because another missionary, Mangin who arrived without adequate support and resources, was buried here on 26 August.

Travelling to Lake Nyasa

28 August. News is received that SS Domira is unable to come further down the river than Mponda because the water is so shallow. He leaves Blantyre with the ship’s captain for Matope 56 km (35 miles) away by foot, saying there is nothing very interesting on the road away from Blantyre and that the air is thick with smoke from the bush fires over the whole country that leave it for a time a blackened waste.

He believes the prohibitive freight costs charged by the river steamers and the shallow waters of the Shire river make the export of agricultural products such as cotton, coffee and sugar impossible. The construction of a railway is the only solution.

29 August. They board a boat with two sets of boatmen to row up the Shire river with its strong current and a head wind. During the night on the riverbank Johnston has the sensation of red-hot needles on his face and a light reveals hordes of ferocious red ants.

Next morning they shove off again: “keeping a sharp lookout for the hippos, which keep bobbing up unpleasantly near our heavily laden boat. They seem more ready to go for intruders on their domain at this season, as many of them are accompanied by their young, some not larger than an ordinary pig and often seen standing on the back of their dam.”

They reached Milouries village after midnight, but frequent showers make sleep uncomfortable. Early in the morning they embark once more hoping to reach Mponda without further delays and the rowers are promised extra pay if they row in the night. “This proved rather risky as toward the small hours of the morning when the captain and myself were enjoying ‘forty winks’ yells from the boatmen and the sudden upheaval of the boat brought us to our feet. We felt sure that the next minute would find us struggling in the river but, happily, our two tons of cargo were not so easily tipped over and we escaped a ducking. It was only a drowsy hippo trying to balance us on its back in rather shallow water.”

On Friday morning they entered Lake Pomalombe (present-day Lake Malombe) yellow mud being stirred by the oars. The lake was crossed in six hours and before dark they reached SS Domira lying at anchor in the stream opposite Mponda.[vii] However, the disappointing news is that the steamer will not be leaving for another three days as none of her cargo is on board.

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Map-of-Lake-Malawi-System-showing-La...

Mponda

On the west bank of the river he says the village “is the largest collection of native huts we have seen in Africa. The population consists mostly of Yao’s and Nyange’s. The only attempt at missionary work among them was made years ago by four Jesuit priests; but they found the place too unhealthy to remain more than a few months, when they retired from the field and went to work in Tanganyika” (present-day Tanzania)

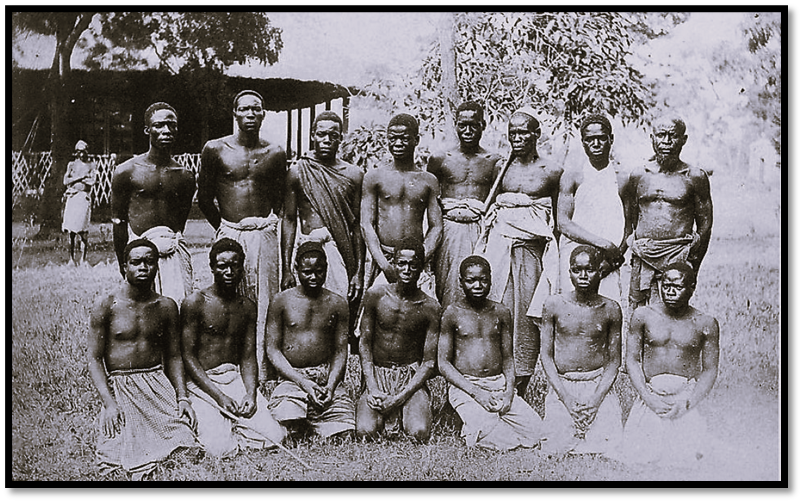

A group of Yao tribesmen, Shire Highlands

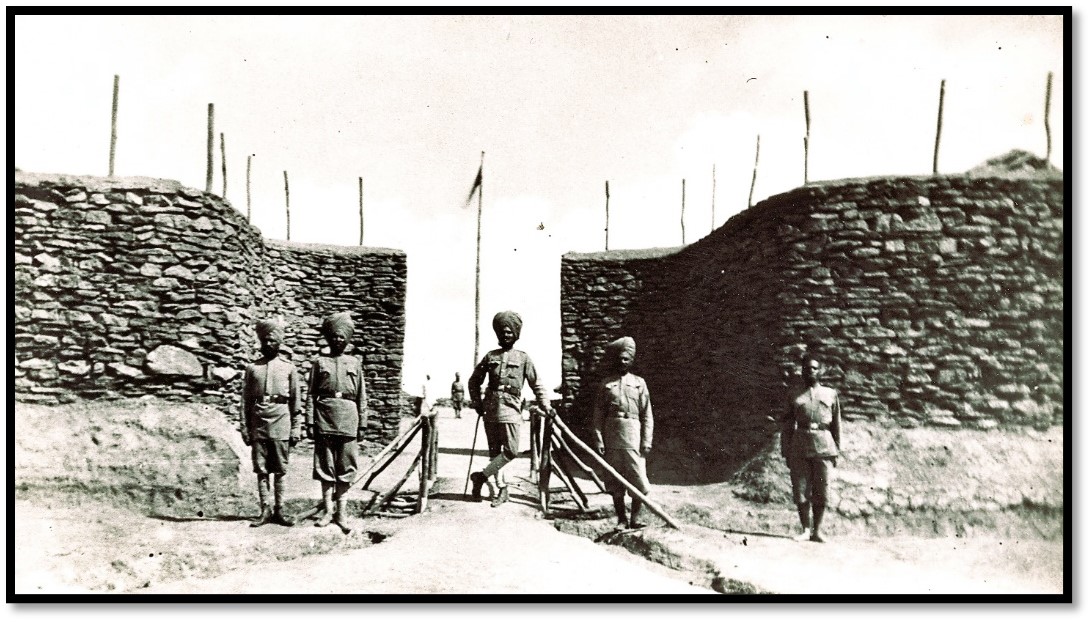

On the east bank of the Shire is Fort Johnston. “The fort has been constructed as the headquarters of the British administration and is garrisoned by about twenty Indian Sikhs and a few Zanzibari. There is nothing very imposing about the fort proper, it being little better than a low bank of sand thrown up in the form of a square and surrounded by a ditch.”

National Archives of Malawi: Fort Johnston

4 September. By 10:30 the SS Domira has steam and they drop anchor that evening at Monkey Bay, a snug and pretty little harbour surrounded by hills.

Wikipedia-Stefan7: Monkey Bay

Next morning, we were delayed for several hours taking on firewood. Once completed, we started again and reached Cape McLear by midday. I went ashore to see the mission station where a native teacher is in charge and I am told doing good work among the children of the district.

There are several buildings making up the mission. They were built by the early missionaries, many of whom died of fever, including Dr William Black. The old Livingstonia mission at this site is only a few feet above the level of the lake and very malarial. The survivors decided to move north to Bandawe.[viii]

The old Livingstonia mission at Cape McLear

We left Cape McLear the same evening and crossed the lake to Maganga where supplies were left for the Mvera missionaries. Next day a fierce storm arose and we were forced to sail past Kotakota in case we were driven ashore; the storm only ceased toward evening.

Bandawe

Early in the morning we anchored at Bandawe and Johnston collected his mail from Dr Elmslie although there was a gap of nine months.

Photo: marysuemakin.wordpress.com - Bandawe Church

Although the first missionaries of the Free Church of Scotland arrived in 1878, this church was only built in 1923. Bandawe was the second location for Livingstonia mission after Cape McLear.

SS Domira was sailing for Karonga and Dr Elmslie invited Johnston to stay until its return before going onto Lokomo. Bandawe is built on a sandy promontory into the lake and is 274 km (170 miles) north of Mponda. The buildings, all built of brick with thatched roofs include missionaries houses, a school and meeting house, carpenter’s shop and printing room. However, like Mponda it is malarial and in 1894 the mission moved once again from Bandawe to Kondowe, again for health reasons.

Bandawe mission station

A key feature of Bandawe mission was its school which included boarders and many from neighbouring villages as day-scholars. Johnston says local people are recognising the benefits of having missionaries amongst them, not only for the medical aid, but also in protecting them from hostile tribes and slave-traders.

He writes that there can be no question that the trade in ‘black ivory’ still exists and that it must be stamped out, but that it is important to discriminate between slave-trading and domestic slavery. “The whole life of Central Africa is permeated with a system of slavery, which the natives themselves have no desire to see abolished, although it must come in time. But high handed measures will accomplish little in this direction, rather let force be concentrated to arrest the cruel and bloody work of the Arabs, who raid and capture slaves for gain only.”

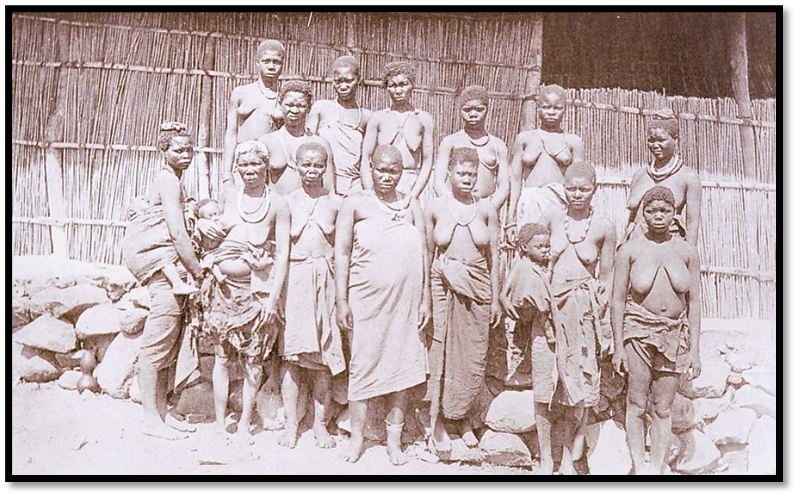

He writes that he has taken several photos of groups of native women: “who were employed on the premises as labourers in the construction of a dwelling house. Those in the foreground are mostly the old women, showing the deformity of features produced by wearing the pelele in the upper lip. This repulsive custom is not confined to the old, but no sooner was the camera placed in position and my head hidden beneath the focusing cloth, then up went the hands of the younger women to their mouths, and the rings were whipped out quick as a wink, the old women however, are less sensitive.”

Women labourers employed at Bandawe mission

He describes trial by ordeal, or the ‘mauvi’ test as being common amongst all the tribes north of the Zambesi and is used to “smell out” witchcraft, or convict persons suspected of crime or even for settling quarrels. As a rule natives who are convinced of their innocence take the test readily as they have full confidence the ‘muavi’ will convict only the guilty.

He quotes a few examples of “mauvi” noted by missionaries: “It seems that everybody in the village, men, women and children above 9 or 10 years old, many of our school children among them, had drunk it and that a few from a distance only remained for Saturdays drinking. Seven in all were found dead - cast out to the vultures - including an old white haired man and wife and the headman of the village, but no children. The possessions of those who died were taken off to Tshipolopolo - the sub-chief who brought the charge against the victims and appealed to Chikusi for the trial.”

“Another mauvi-drinking took place last Friday at which two of our schoolgirls, little things of 10 or 11 years old - and a woman died. The excuse was the death of a man in their village.”

He writes that in the Barotse Valley, poison is poured down the throat of a dog or a chicken and they judge the innocence or guilt of the accused party by the effect the poison produces on the animal – vomiting is proof positive of innocence, while purging indicates guilt!

Likoma

14 September. SS Domira returned, but has to go to Likoma for repairs and then go to Karonga for passengers, so he got on board and was at Lokomo next morning. This is an island about 8 km (5 miles) long and 5 km (3 miles) wide and 16 km (10 miles) from the mainland with a population of over 2 000 natives. The soil is poor and the vegetation sparse except for Baobabs. The headquarters of the Universities mission are 1 km (0.5 mile) from the beach.

The school, store and boys dormitory are built of stone and mud, the staff housing and church from reeds with Archdeacon Maples in charge of 7 or 8 European men and women teachers and several native teachers from Zanzibar. The mission has two small steamers, the Charles Jansen and the Beta that are used for visiting villages along the coast and are under the command of Rev Johnson.

Nyasa fleet at Likoma

Johnston says the Sunday service was mainly choral with the archdeacon playing the organ accompanied by a well-trained choir of school boys with most of the congregation being women.

Native women, Likoma

21 September. A weary week waiting for the SS Domira to return today. By sunset they are heading for Cape McLear and 36 hours later anchored at Mponda.

25 September. He takes an open boat and assisted by the Shire’s current is at Matope next morning. Carriers were ready and after a hurried breakfast, they started for Blantyre with the mission station reached late that night.

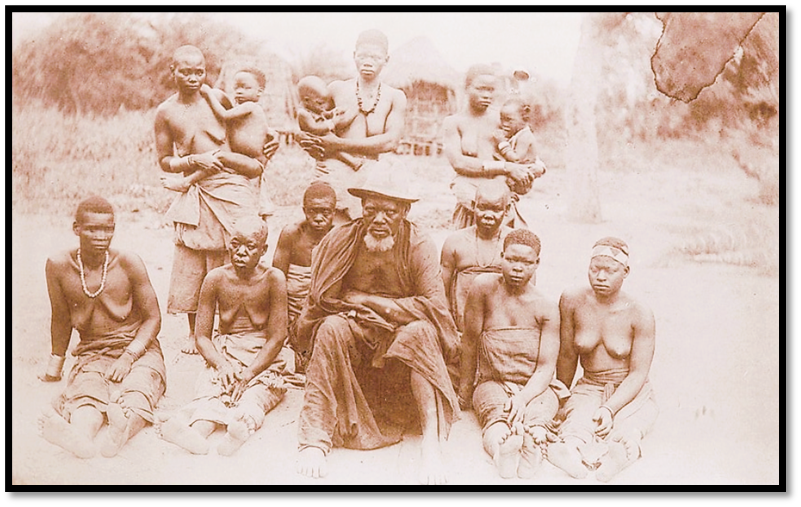

Katunga and his wives (Livingstone’s old servant)

28 September. Leaves Blantyre with carriers for Katunga on the Shire river where he stays the night at the African Lakes Company station and next day leaves by canoe. At Chiromo he gets back his firearms and although he slept under wet blankets for four nights they reached Chinde on the Chinde river, part of the Zambesi delta, in 11 days on 10 October.

He managed to secure a passage on a transport steamer leaving for Port Said via Zanzibar and then to England before returning to Jamaica where his book was completed in October 1893.

References

James Johnstone. Reality versus romance in South Central Africa: An account of a journey across the continent from Benguella on the West, through Bihe, Ganguella, Barotse, the Kalihari Desert, Mashonaland, Manica, Gorongoza, Nyasa, the Shire Highlands, to the mouth of the Zambesi on the East Coast. Hodder and Stoughton, 1893, London. Digitised by the Internet Archive with funding from the Wellcome Library.

https://archive.org/details/b29351212 From the Wellcome Collection: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/ax9dvx6u

Notes

[i] Manuel António de Sousa (1835 – 1892) was a Goan of whom Malyn Newitt writes: "made a fortune in ivory trading and his armed elephant hunters formed the nucleus of a private army which he repeatedly made available to the Portuguese authorities during the Zambesi wars." His personal empire was based around Gorongoza.

[ii] The company that contracted to bring goods up from Beira was that of Messrs Johnson, Heany and Borrow who went into business at Fort Salisbury in 1891. Maurice Heany was in charge of making a road and establishing the transport business, the Pungwe route to Mashonaland – but the task was probably insurmountable at the time with tsetse-fly, malaria and the primitive conditions. The oxen and wagons were from the Pioneer Column that reached Salisbury in September 1890.

[iii] I can find no present-day reference to Mabute, but it maybe where the N7 crosses the Pungwe river that then takes a more south-east direction

[iv] The war between Gouveia and Makombe

[v] Chiromo means ‘joining of the streams’

[vi] The photos of the HMS Herald and Mosquito are from the article The Construction & Commissioning of the Zambezi Gunboats HMS Mosquito & HMS Herald by David Stuart-Mogg in The Society of Malawi Journal Vol. 69, No. 2 (2016), pp. 35-44

[vii] On the Shire river approximately 5 km north of Lake Malombe

[viii] Wikipedia source: Missionaries from the Free Church of Scotland first established a mission in 1875 at Cape McLear. But by 1881 Cape Maclear had proved extremely malarial and the mission moved north to Bandawe. This site also proved unhealthy and they moved once again to the higher grounds between Lake Malawi and Nyika Plateau. This new site proved highly successful because Livingstonia Mission is located in the mountains and not malarial and the mission station gradually developed into a small town.

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: