Carl Peters and The Eldorado of the Ancients

Introduction

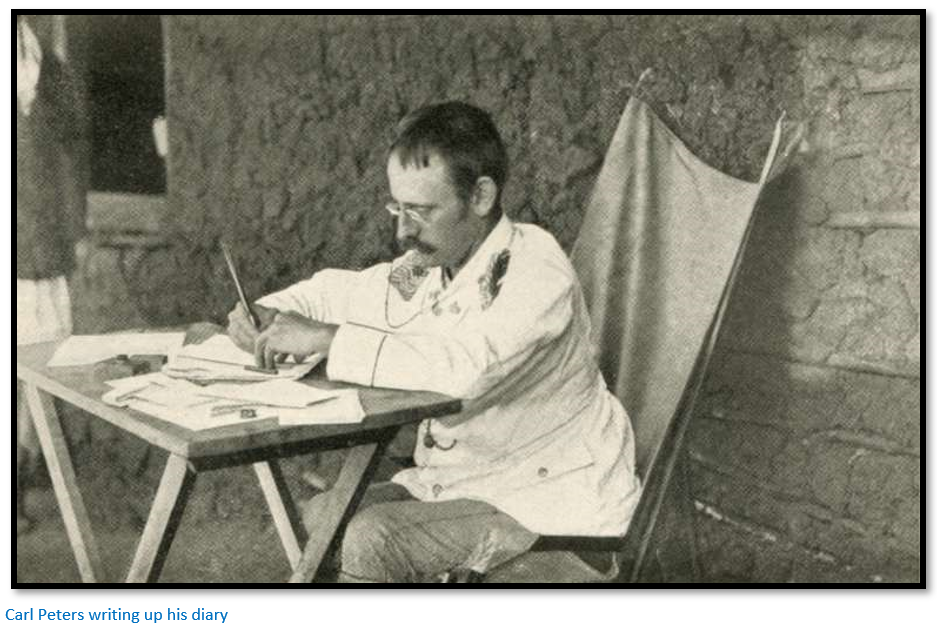

Carl Peters (1856 – 1918) was a German explorer, author, self-publicist and colonial enthusiast who believed that Germany’s economic survival depended on obtaining colonies, he was behind the colonization of German East Africa (present-day Tanzania) His book The Eldorado of the Ancients was based on exploratory journeys in March 1899 to June 1900 through Portuguese East Africa (present-day Mozambique) and along the length of Manicaland in Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe)

A supporter of the Volkisch philosophy, a German popular and nationalist and typically racist movement which was active from the late 19th century until the Nazi era, Carl Peters’ attitude towards the indigenous population made him one of the most controversial colonizers even during his lifetime. He was pardoned posthumously by personal decree of Adolf Hitler twenty years after his death in 1918.[i] A propaganda movie 'Carl Peters' by Herbert Selpin was released during 1941, featuring Hans Albers.

Carl Peters with his friends Karl Ludwig Jühlke and Count Joachim von Pfeil founded the "Society for German Colonization" (Gesellschaft für Deutsche Kolonisation, GfdK) and they initially conceived the idea of obtaining a concession in Mashonaland from Lobengula, but discovered the region was largely dominated by the British and switched their attention to the Sultanate of Zanzibar.

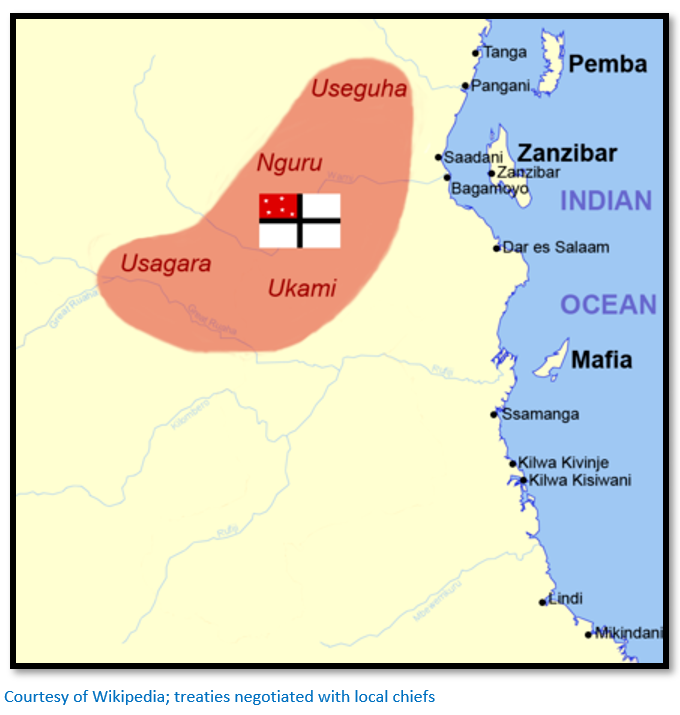

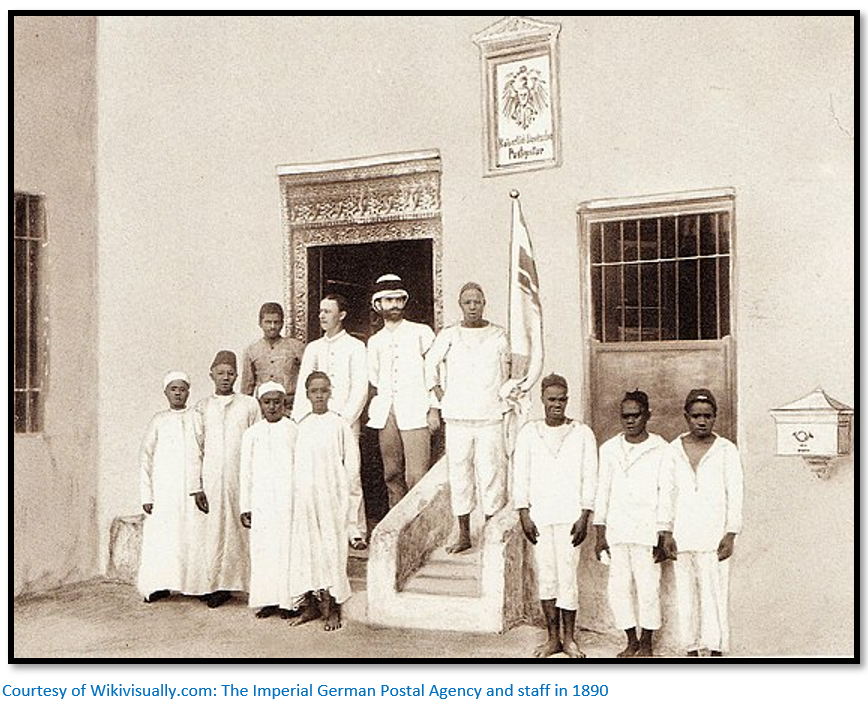

Not content with recent German acquisitions in South West Africa (present-day Namibia) Togo, Cameroon and the north-eastern part of New Guinea, Peters signed treaties with East African tribes, which were dubious to say the least, but in 1884 enabled the East Africa Company to gain a charter to administer the new colony.

Oscar Baumann who explored the region of German East Africa including present-day Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi and produced extensive maps of the region called Peters “half crazy” and the more liberal-minded newspapers gave him the nickname of Hänge-Peters ("Hangman-Peters") A modern German social historian Hans-Ulrich Wehler described him as a “low-success judicial criminal psychopath.” Even at the time, many German Foreign Ministry officials considered his activities more reckless than heroic and an unwanted and unnecessary danger to German foreign policy.[ii]

The Eldorado of the Ancients

Carl Peters’ book is the subject of this article with details of his life and career following after. As A.J. Chennells writes in the foreword to the reprint edition the book is the “work of a deeply embittered man” who two years before had been stripped of his German official title, but still hoped to show that he had a role to play in colonial affairs. “I have not voluntarily left my old work, nor with a light heart, but was compelled to do so.”[iii]

The theory that the ruins and goldmines in present-day Zimbabwe had exotic origins in the Middle East and the voyages of Solomon’s fleet to Ophir, or in the Phoenicians of the Mediterranean had already been proposed by Karl Mauch, Theodore Bent, Hall and Neal, Wilmot and numerous others (but not Selous) played into his own racist philosophy and from the outset in his introduction, Peters states that he intends to prove that most of the ancient world’s gold and ivory came from the region. This is clearly stated in the first chapter title of “My Call to Ophir.”

However in this article I intend to concentrate solely on the details of Carl Peter’s expedition and avoid all the speculation in which he indulges himself most of which is based on ancient maps and descriptions and doubtful philology. The chapter headings mirror those of the book.

Early Explorations

From Chinde steamboats carried passengers and supplies to either Lake Nyasa, now Malawi or up the Zambesi for eight or nine months whilst the river was navigable to Tete between the end of December and mid-September. The party at Chinde on 15 March 1899 consisted of six Europeans, although he only mentions Puzey, Ernst Gramann, von Napolski and himself. On 3 April they left on board the King with fourteen tons of luggage up the Chinde river[iv] before anchoring for the night. Travel is during daylight hours only because of many sandbanks and daily travel is about 100 kms (63 miles)

Next day they joined the Zambesi river and in the evening take on wood fuel at the Mozambique Company station of Morassa (probably Marrameu) on the south bank. The following day brought them to Mutarare, a station of the Companhia da Zambesia on the north bank from where they crossed to Sena on the south bank and received an invitation next day for lunch with the Governor Senor Pinto Basto and local officials. The next night was spent opposite the plantation of Santa Tao and then another fuel stop at the Mozambique Company station at Chiramba. On 11 April they disembark at Tambara at the eastern end of the Lupata Gorge.

Puzey opened a trading post here in 1896 for the trade with Macombe who at this time was in a state of rebellion with the Portuguese. Peters hired fifty-six bearers and on 15 April enters Macombe territory to the district of Inja-ka-Fura. They followed the riverbed of the Miura which is dry and after a few hours enter a valley which he found more picturesque and mysterious than anything that Rider Haggard could have conjured in his mind! The peaks on both sides resembled old castles, but on closer examination turned out to be natural. They see quartz sand in the riverbed and conclude there must be quartz reefs higher up with the possibility of gold! He is so carried away he names the peak on the eastern side after the chairman of the company Mount Thornhill and that on the western side Mount Peters after himself!

The porters are dismissed as they intend to camp at this place in the centre of the Muira river valley and make short trips. Gramman has already had a severe attack of fever and is stuck in camp. In the afternoon of 16 April Peters and Puzey continue to the south end of the valley beyond which he speculates will lie Mount Msusi at the base of which the second chief of Macombe, Kambarote, governor of Inja-ka-Fura has his kraal.

Next day local natives come to sell food and on being asked where is Inja-Sapa they state it is to the east of the mountains (i.e. on the Zambesi side) Next morning 17 April Puzey and he head back down the Muira river valley and along the track already traversed and turn east and about five kms from the river where they find a strong stockade in a dense forest at Inja-ka-Fura. They ask local people if they know a place called Massapa and are told this is the very place and Peters writes “apparently we were here on the site of the old Portuguese market-place of Massapa…which is ‘an open market-town, in which gold was exchanged and where the Capitao das Portas (Captain of the Gates) with a few Benedictine monks had his residence.”

The site confirms all that Peters has read about the Portuguese feira. Massapa is not in the gold region itself, but at the gates, hence the title Capitao das Portas. He believes that an hours’ march west of Inja-ka-Fura are the ancient gold mines and they are convinced that soon they will find the ruins of Fura (the Ophir of the Bible) itself.

Next day they march for six hours around Mount Thornhill without result. The following day Gramann is feeling better and pans the Muira river and finds traces of gold which Peters takes as confirmation they are in the vicinity of goldfields.

Peters has neglected to pay a courtesy visit to any of the local chiefs asking permission to enter their territory saying it is a waste of time and on the basis they might refuse permission. Now on 17 April the headman of Mafunda where they located “Massapa” marches past their campsite in the Muira river valley with 300 riflemen and then begins war-dances around their tents and to make threats against them. Consequently next day 20 April he sends Puzey to Inja-ka-Fura to settle matters with chief Kambarote.

Puzey returns by noon saying he saw a ruined wall on the track from Mount Peters to Mount Msusi and returned with the good news. They visit the wall with Gramman in the afternoon, the now named “Puzey’s Hill” is within a bend of the Muira river which Peters speculates may have originally been an artificial ditch like a moat! Further examination of the walls unearths “curiously formed stones” that Peters believes to be betylae objects of religious worship in the oldest Semitic cults. The great ‘heaps of debris on the edge of the precipice’ sounds remarkably like exfoliated granite which peels off in thin flakes known as onion-skin weathering.

Peters again speculates that these ruins are older than those encountered later in Mashonaland and believes ancient gold-seekers sailed up the Zambesi as far as the Lupata Gorge and made their way inland up the Muira river to the “northern part of the ancient Eldorado.”

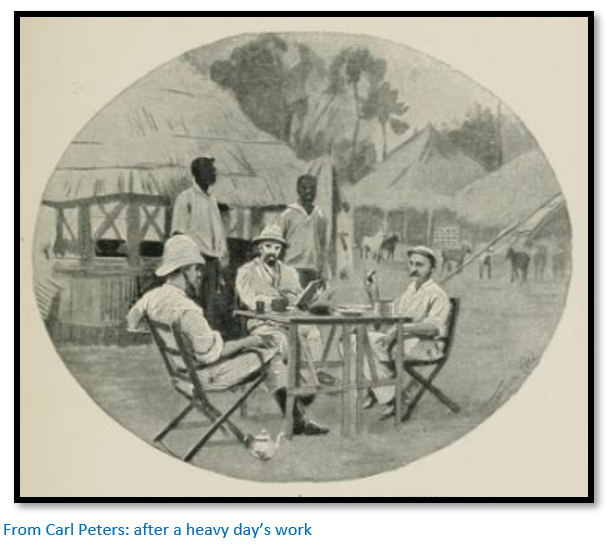

Peters, Gramann and Puzey investigate the area until the end of June. He gives few details except to say that the natives of the area throughout the whole district pan for gold in the rivers which is bartered for goods and that he patched up relations with the chief and that his brother, Cuntete visited their campsite. They are joined by Herr Blocker[v] who appears to be the geologist although Peters writes “the details of our geological research are not of general interest” when the purpose of the expedition is to search for gold!

Among the Makalanga

The title appears misleading as there is no mention of the name Makalanga throughout the chapter. On 28 June Blocker and Peters set out for Tete to register eighty gold claims starting from Tenje,[vi] whose location appears to be 30 kms inland and north of the Lupata Gorge and next day they reach Tinto on the Zambesi which lies 6 kms below the Portuguese fort of Massangano. They march up the banks of the Zambesi following the telegraph line from Chiromo and on the 30 June Peters shoots four crocodiles. Next morning they cross the Ruenya river at its confluence with the Zambesi with Peters being carried across by three natives and again camp on the Zambesi bank arriving in Tete next day where they enjoy lunch with Puzey who had come in earlier because of illness.

Peters describes Tete with its eighty Portuguese and twenty other Europeans as “the most god-forsaken place on the Zambesi” with no sanitation and the whole atmosphere polluted and the fort as “incapable of any great resistance.”

Peters, Puzey and Blocker leave Tete by river on 4 July to Kapiendega, a station of the Zambezia Company above Lupata Gorge and the nearest site to their camp at Tenje. Peters says “the up-river journey was splendid” although in fact they are going down-river from Tete. Arriving back at Tenje they found Cuntete, chief Kambarote’s brother with a present of ivory from Macombe. Macombe had a few weeks before attacked and killed chief Dingo at Tela kraal, an hour’s march from Tenje, because Dingo was friendly with the Portuguese and replaced him with one of his own men.

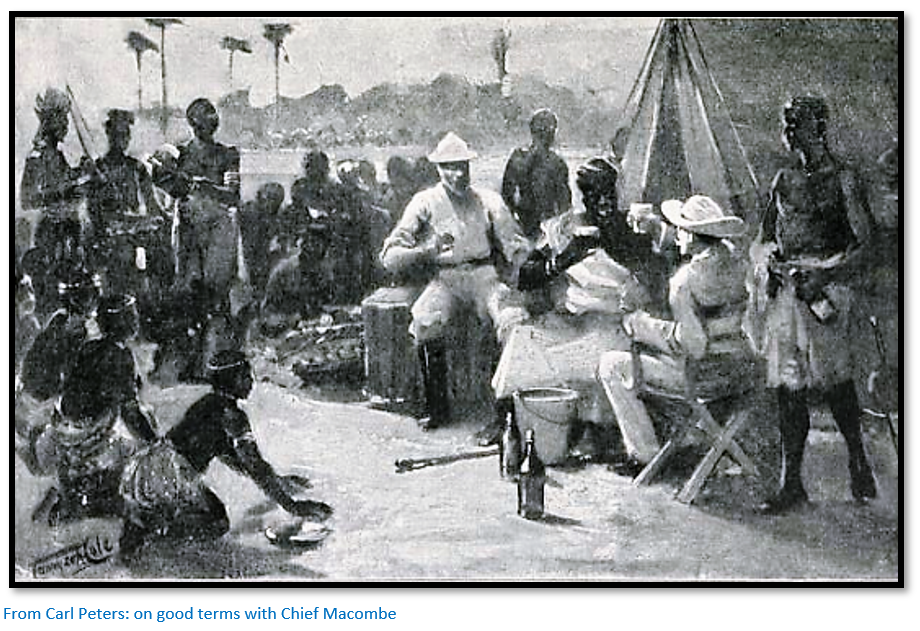

Puzey’s contract ended on 15 July and he returned to Bulawayo via the Ruenje river and Umtali, now Mutare. While Von Napolski was making a map survey of the country, Blocker and Peters went south and found a promising looking quartz reef. Then as little food had been sold by local natives Peters and Blocker went through the Muira river valley to Inja-ka-Fura to meet Chief Kambarote for whom Peters had bought “magnificent presents” namely coloured cloth from Tete, a frock-coat, a bottle of cognac and calico cloth. At a council meeting Peters makes a request to buy food and for a supply of labour, to which after some consultation with the elders, the chief replied: “Dokatore Peters, my people will sell thee food, as much as thou mayest require and this very day I shall send the workmen. Also thy friend here we will receive in peace. If my people ask too high a price from you, then send to me and I will fix the price myself. Should they not obey, I will have their heads cut off.”[vii] The language here seems like another piece of Peters’ fantasy, as is his observation that the local natives “have faces cut exactly like those of the ancient Jews who live around Aden.”[viii]

Spring on the Zambesi

The next chapter is a long-winded description of winter and then jumps to a description of a thunderstorm and extracts from Peters diary in December 1900 of life on the Zambesi. “today I shot eight crocodiles, six hippopotami, three ducks and two river-hens.” There follows a long description of voyaging down the Zambesi to Chinde: “we have arranged things comfortably for ourselves in the fore part of the boat with tables and chairs; we read, smoke and chat and every now and then fire off a shot” all of which is totally irrelevant to the main subject.

The Kingdom of Macombe

Peters leaves Blocker and Gramann at Tenje on 15 July and walks up the Muira river towards its source leaving the district of Inja-ka-Fura and next day reaching Lolongoe which the natives tell him was formerly a Portuguese station and he believes is the feira of Bocuto. Quoting Theal in his book The Portuguese in South Africa states: “Bocuto was thirty miles distant from Massapa and only a little store with no interesting features…”[ix]

Peters criticises Theal for not being more precise on the location: “Massapa was situated on the river Manzoro, the Mazoe (now Mazowe) of today” and asks: “from what point near the Mazoe is one able to look over the Makalanga country?” Peters then goes on to say the centre of Makalanga country is the Muira, its chief is Macombe whose residence Misongwe lies on the bank of this river and that the distance from Massapa to Bocuto, that is given as thirteen leagues, fits this location well. [But no mention of the Manzoro] He criticises Theal once again saying “He speaks continually about the Kalanga districts…without stating where this clan lived” and “it is a pity he did not go deeper into this question before writing his book.”

On 18 July they reached Chief Macombe’s kraal at Misongwe and Peters’ presented his gifts; calico, coloured print for the wives, cooking pots, salt and a demijohn of gin. The chapter is a long description of his conversations with Macombe notable only for references that no Portuguese would be tolerated in the kingdom and that Macombe is at war with them. Finally, Peters is granted permission to march through Macombe’s country and sold supplies of maize flour.

Peters says for the Makalanga agriculture is their first activity, alluvial gold is panned and they are clever iron-workers and good at carving wood chairs and headrests and make high-quality mats and pottery. There is a long description of their religion and he concludes: “under any circumstances we have absolutely ancient Semitic religious ideas before us”[x] and once again he fits the facts to fit his theories.

Peters concludes that the old State of Mwene Mutapa has dwindled down the centuries and the last remnant is preserved in Macombe’s country.[xi] They leave on 23 July after a delay of five days to get the necessary permissions to cross Makalanga country accompanied by Macombe’s brother, Cuntete. As they are crossing granite country without any prospect of finding gold Peters concludes: “nothing can be expected here for the prospector.”

His original intention had been to march to the Pungwe river and then Umtali, now Mutare, but decided he could not carry enough supplies for his porters and changed the route to the upper Injasonja river and from there to Katerere. Piso the half-brother of Cuntete will join them as far as Umtali. Next morning Peters wants to start off: “It was bitterly cold and difficult to push the carriers along; they sat down, lighted fires and declined to rise. I had to use my walking stick in order to induce them to move on.”

They march in a south-westerly direction and next morning: “we crossed the merrily flowing Injasonja, one of the tributaries of the Pungwe.” Next morning they cross many tributaries of the Injasonja – Manjate, Muse, Jansaro and Indue and see the Manica mountains in the south-west: “like a steep, high, rocky wall.” From midday they turn north-west and begin to climb reaching 1,100 metres (3,600 feet) with extensive views over the Pungwe and now in dense mountain forest. “There cannot be any doubt that coffee and tea could be grown here splendidly.”

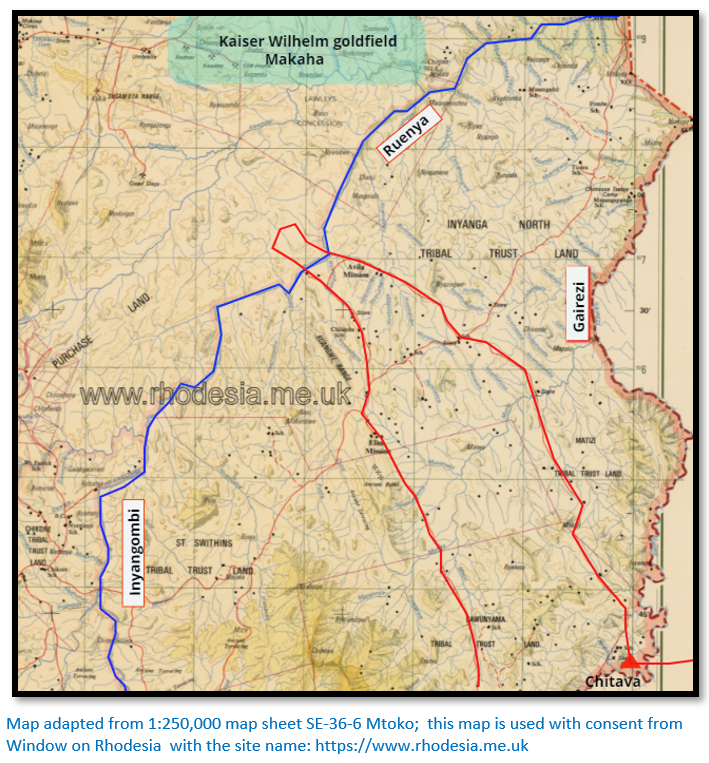

Next morning they begin the descent into the Gairezi river valley. “Inyanga [now Nyanga] rose up to 10,000 feet, illuminated by the rays of the golden sun.”[xii] “The river may be 80 feet wide. I was stretched like a packet over the heads of three of my men and was transported across the river in this fashion.” They pitch camp at Chitava kraal and were welcomed by the chief, a brother of Cuntete with a rhino-horn for Peters. “At sunset I took a bath in the cool river and then a happy dinner united us at which fish, European potatoes and boiled tomatoes were a pleasant change…The march on the following day should get us out of the Portuguese sphere of influence into the British.”

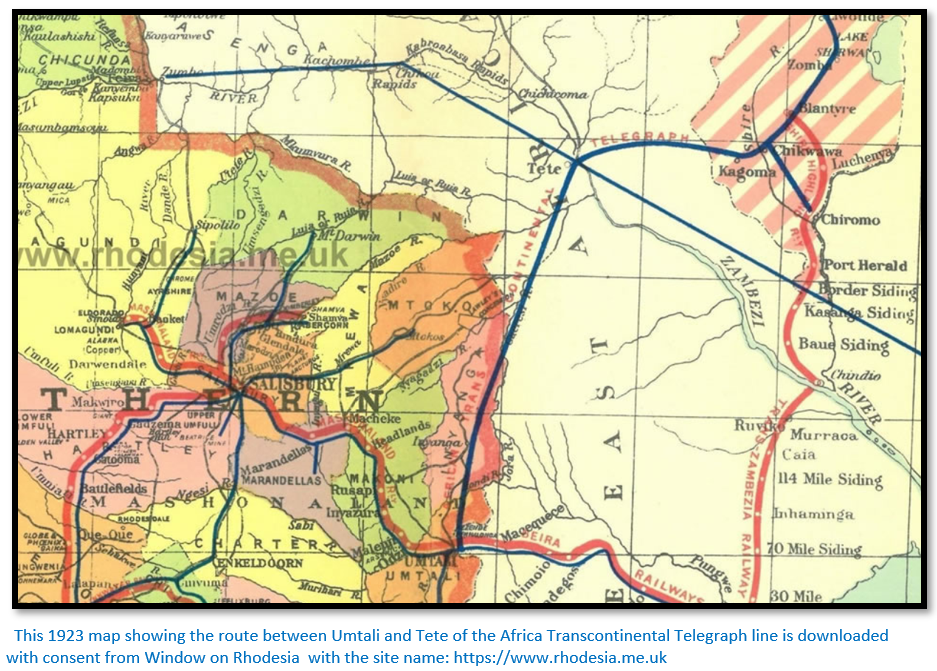

They march north-west towards Katerere with the Gairezi on their east – Peters notices great numbers of heaps of quartz over the countryside: “They could not be workings for gold, because the geological formation here excluded the presence of that metal. Herr Gramann thought we had ironworks before us.” The Trans Continental Telegraph line is often seen as it stretches along the eastern border before heading towards Tete. [For more information see the article Dan Judson and the Africa Transcontinental Telegraph Company under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Ancient Ruins in Inyanga

Katerere was experiencing a famine and there was no food for sale on this side of the Ruenya river. They follow a wagon-track that leads towards Matoko’s [now Mutoko] country wandering through the whaleback granite hills and reach the Ruenje river which is crossed by means of a primitive bridge a few hundred yards upstream. “…the prevailing formation was granite which seems to fill the whole of the south of the so-called Kaiser Wilhelm land.” Soon after they reached Simbuyi, a small settlement and the chief agreed to sell food. “By the evening, to my great delight, I saw troops of women coming in with the customary flour-baskets on their heads.”

Gramann and Peters travelled north but: “If the Kaiser Wilhelm “gold-field” really exists it most certainly does not lie on this side of the country…From a mineralogical point of view we were very disappointed with this Kaiser Wilhelm-land which Mauch had passed through and in which we expected to find quite a different formation.”[xiii] [See the article Karl Mauch, explorer and geologist and the man who claimed to be the first European to visit Great Zimbabwe under Masvingo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

As shown above, they cross the Gairezi at Chitava and march north to the Ruenya which is crossed, but they do not travel far enough north to encounter Karl Mauch’s Kaiser Wilhelm gold field at Makaha.

On 5 August they re-crossed the Ruenje river and travelling through countryside dotted with granite kopjes reached Matombo or Nhani and is north-west of Mount Taui which Karl Mauch christened Mount Moltke. “It is the highest summit of this granite formation and forms an excellent landmark, visible from a distance of several days march.”

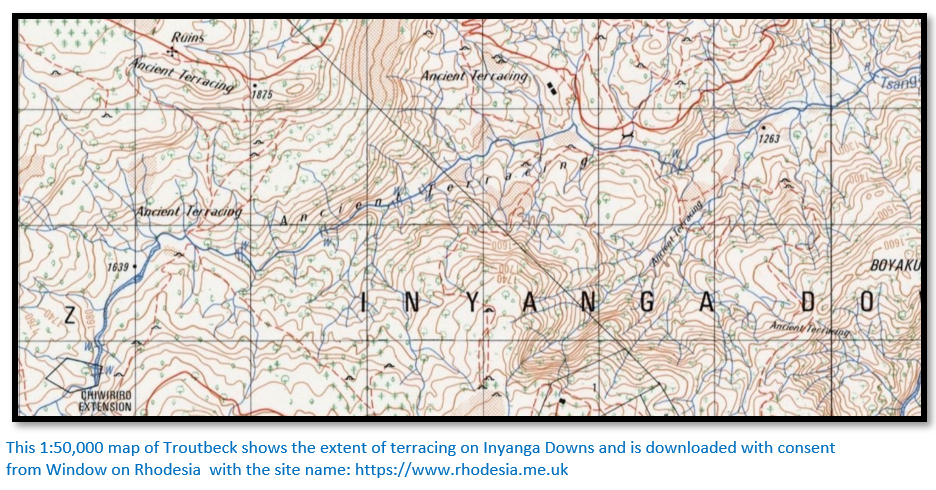

“…I had seen a circular stone wall, which Herr Gramann took to be an enclosure for cattle; it was built with cyclopean rocks, probably owing to the scarcity of timber. Now we found more of such enclosures, some of them quadrangular. At ten o’clock after a very tiring march, partly over swampy ground, we sat down in the centre of a whole system of such pens, which formed a big rectangular enclosure surrounded by a series of smaller circular walls.

…We soon reached the foot of the eastern hill along which a sparkling brook was running and here the ruins of stone walls became even more bewildering. Terraces ran round the hill, one wall above the other. On what were apparently artificial squares those quadrangular walls were standing, giving one a vivid impression that they were the remains of ancient dwellings. The brook which ran along this settlement was artificially bordered and had apparently been diverted to suit the needs of former inhabitants.”

These descriptions continue for some pages…they camp near some structures that have the stone heaps of quartz near them they have being seeing the past few days…”I had two of these opened as the thought had struck me they might perhaps be ancient burial-places. Gramann who controlled this excavation stated that the quartz at the bottom had been subjected to great heat and he took the holes in which the debris was lying to be a kind of stove which might have served to prepare the quartz for crushing…we found behind the house three washing dishes cut into the rock inclined to the one side which might have been used to wash the crushed quartz. A strong round house into which wound a spiral path protected on both sides by a wall was the strangest of these ruins.”

Their conclusion? “We had then here the dwelling of the ‘mining engineer’ with houses for the ‘boys’ distinct traces of quartz that had been worked by fire, dishes for washing the crushed quartz and a treasure-house on the bank of a running watercourse.”[xiv]

They encounter the first of the Nyanga terraces. “This projection which rises about 2 – 3,000 feet above the valley looked from a distance like a striped zebra. When we came nearer we discovered that this strange appearance had its cause in a gigantic artificial system of terraces and that we were facing either an imposing ancient fortification or a grand arrangement for getting hold of the rain running from the top. Of these terraces along whole mountains we now found a great number.”

Peters speculates:

- They are agricultural terraces as in China where each square foot is cultivated, or

- They served either defensive or religious purposes“ In connection with these terraces the district in front of us for another hours march was strewn with stone walls and stone heaps so that the diameter of this whole settlement must be estimated at about six English miles. Here ages ago, hundreds of thousands of people must have dwelt together.”

As they get nearer Nyanga: “The artificial walls, it is true, did not quite cease here, but decidedly decreased in number…” There are descriptions of rock outcrops that sound deluded: ”…the figure of a knight with mantle and sword stood, hand on hilt, gazing over the wide valley at his feet.”[xv] They have been marching directly south until finally they see the beginnings of European houses; is this the early Dutch Settlement which Rhodes encouraged? Peters is not very complimentary about their enterprise and next they reach Mocfurt and Smythe’s store where they pitch camp. It is now 8 August and water left outside froze during the night. It is more difficult getting firewood also and the carriers feel the cold.

Next day they visit a nearby Boer farm, although only the “tante” was present and he says: “Then the ‘farm’ although in reality there was no such thing was shown to me.”

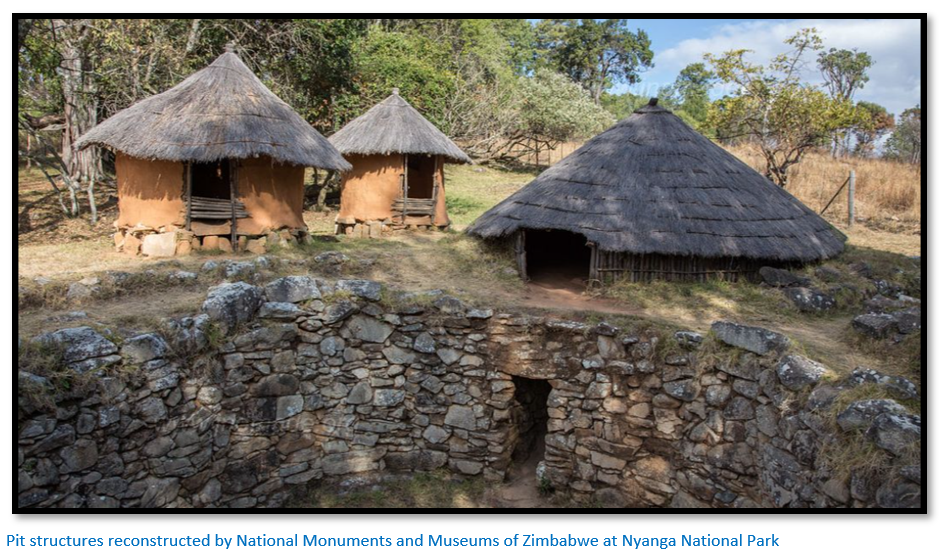

The following day the track goes steadily uphill and finally they reach the police camp at Inyanga[xvi] where nearby they come across pit structures and he says: “We now discovered the first example of a new class of ancient stone building which we came across very frequently in the district now before us. These were pits, after the style of wells, with a diameter from ten to fifteen feet, walled in with carefully built cyclopean walls. The pits we saw were twelve to fifteen feet deep but may have been filled up in the course of centuries. Others which we saw later on were up to twenty feet deep. Often, nay, almost in every case, old trees were growing out of these pits.

The curious feature of these buildings is that the entrance is formed by a subterranean passage at the most three feet high which may be sixteen feet long, dug into the ground and also walled with rock. What does this all mean we asked. Apparently so we thought that afternoon their object was to lock up something; animals or slaves, or to protect something against the cutting south-east wind.”

[See the article on Pit Structures under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Between the police camp and the pit structures the previous day Peters states he discovered: “a mighty quartz reef which showed traces of old workings” and on 12 August he and Gramann return to nail up a discovery notice. (i.e. a gold claim)

Twenty of his carriers are paid off here and will walk back to Tete. The march continues – Mount Nyangani is described as 11,000 feet high – and they pass Rhodes’ farm which he states was formerly owned by Grimmer. In fact, Grimmer was Rhodes’ manager and the previous owner was G.D. Fotheringhame, the current manager being Norris. [See the article Rhodes Nyanga Farm under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

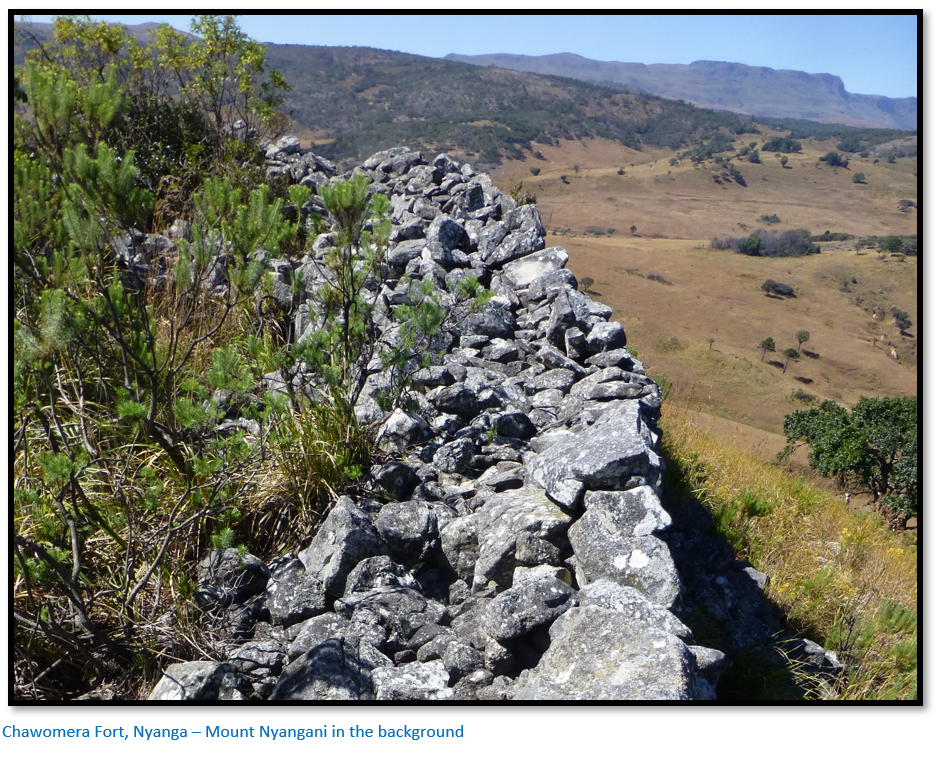

Peters only mentions in passing the Chawomera and Nyangwe Forts but these were clearly visited as his book contains photographs [see the articles Chawomera Fort and Nyangwe Fort under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

That night they camped at Fruitfield Store, named after Fruitfield Farm and formerly also owned by G.D. Fotheringhame and adjacent to Claremont Farm owned by John Moodie, one of the Moodie trekkers.

Peters visits Rhodes farm where the manager Norris shows him an old stone water conduit which had been repaired by him. “Mr Norris drew my attention to the fact that all these conduits of the ancients had not been made on fertile soil, but on rocky ground. He concluded from this that they were not meant for agricultural use, but for mining enterprises.[xvii] He thought the old settlors had not had the means of transport available to carry their quartz to the rivulets for washing and therefore they had laid on the water directly into their mining ground.”[xviii]

He says: “I examined these underground buildings during the next few weeks following up the observations of Mr Norris and have discovered in all of them that the covered entrance passage was constructed uphill.”

Like Anne Kritzinger, Peters believed these pit structures were part of a mining infrastructure: “I should suppose that the crushed quartz was heaped up in the entrance tunnel and also at the bottom and that water was then poured over it which carried away the dust and left the gold behind.”[xix]

On 16 August Peters and Gramann return to their first discovery claim to the north of the police camp where he says: “We also found a number of phalli, symbols of the ancient Semitic worship of the sun. All these facts prove to me that we are here face to face with an ancient mine…” By the 26 August he has Gramann and the newly arrived Blocker examining this reef and others and when they pronounce the quartz veins as “promising” registers eighty gold reef claims at Umtali.

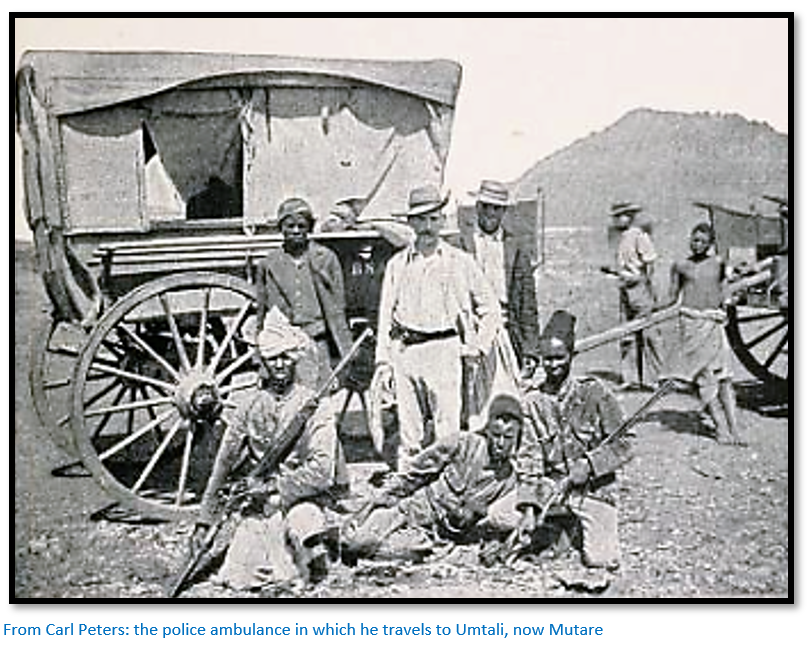

On 2 September Peters left Nyanga for Umtali via Old Umtali in the police ambulance drawn by ten oxen which presumably have been lent to him by Captain Williams. [See the article Old Umtali – the second site under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] At the highest point on the Nyanga – Umtali road which he calls Forty Mile Store (presumably present-day Juliasdale) it is snowing and there is no wood for a fire: “I at once went to bed where I ordered hot tea and claret…The whole of that Sunday I stayed in bed under four warm blankets, which I supplemented with hot drinks.” One hesitates to think what comforts the ambulance driver and staff enjoyed.

Two days later he is at Old Umtali and stays the night with Bishop Hartzell and his wife before travelling on to Umtali, now Mutare where he stays at the Hotel Cecil. He mentions here that Mr Birch, chief of police at Umtali gave him 34 coins found at Nyanga.

In the heart of Manicaland

Peters goes to Macequece (now Manica) and then east crossing the Pungwe on 29 September where his carrier lost his foothold mid-river and held on tightly as they rolled over in the water; Peters only managed to get free with some difficulty! On the other side he and Gramann survey the district but apparently found nothing of interest and return to Macequece. A Mr Sawyer is drawing up a geological map of the area and after a description of the geology Peters leaves Gramann from November 1899 to survey the area and returns to the district in January 1901.

Mr Pacotte, the assayer and inspector of mines of the Mozambique Company takes a week’s leave to show Peters the Manica mining district which is north of the town of Macequece. On 10 January 1901 they leave by donkey across the Revue valley with the road winding upwards in mighty zig-zags and only reach their camp after nightfall.

Directly opposite their camp on the other bank of the Injamkarara river lies the Welcome mine camp and over the hill in the Chimesi valley are the Braganza and Richmond mines belonging to M. Bartisol. Their claims contain twelve parallel gold reefs with the main reef two feet at the surface increasing to six feet at depth with the gold content increasing at depth. Peters says: “As the cost of working only amounts to 5 dwts one can calculate the rest.” The old workings reach a depth of 100 feet: “I do not think that another mining-place in Manicaland has more in its favour than ours which lies fourteen miles from Macequece."

Next day an hours’ donkey ride takes them to Bartisol’s properties. The Richmond and Braganza mines are further uphill and the mine workings at the Richmond consist of a shaft 80 feet deep on the reef and tunnel along the reef of 3 – 400 feet. “The ore yields more than one ounce per ton.” The Braganza reef is thicker, but not as rich.

When they return to their camp next day they have a look at the old alluvial workings along the banks of the Injamkarara: “shortly we came to a strip of country where we had to step out very carefully for there was pit on pit often grown over by thick brushwood. These pits are often 100 feet deep and some of them are connected by underground tunnels. There are between two and three hundred of them on our estate…I noticed that close to all old mining buildings in these districts there are little clumps of Mahoba-Hoba trees (Mahobahoba or “Muzhanje”, U.kirkiana) which bear a very delicious fig-like fruit. The Mahoba-Hoba is almost a sign-post to old mines.”

From the Chimesi Valley they ride by donkey to the Mudza Valley: “To the right lie the houses of a Portuguese settlement where the alluvium of the Mudza is worked. M. Pacotte tells me that the last yield was 6 lbs of pure gold. We cross the Mudza…and reach Mr Bull’s about eleven o’clock, whose property the Windahgil mine, we wished to inspect.” Here Peters reports results of between 1 – 4 oz per ton.

Sunshine and Storm

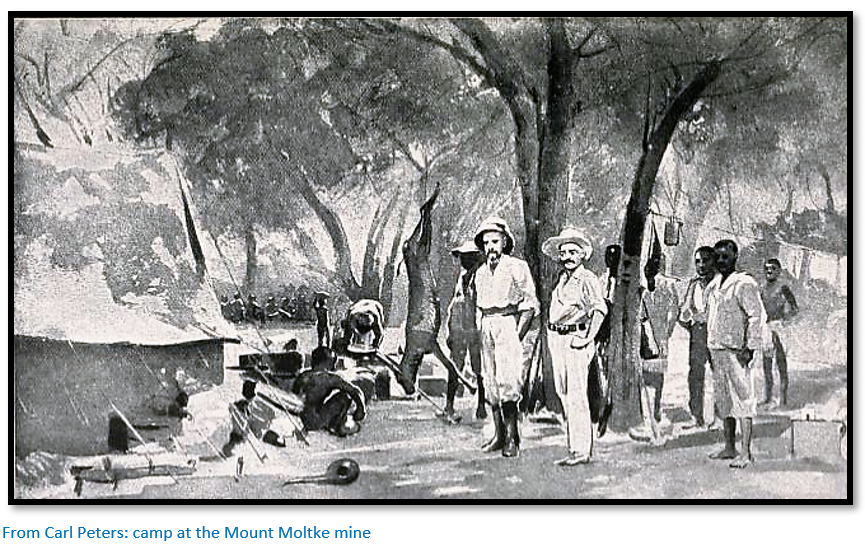

Peters is still at their camp and mine which they have named the “Mount Moltke” above Macequece despite it being the midst of the rainy season. He reports: “The Beira-Mashonaland railway has to stop running for weeks; great patches of the permanent way are washed away…The part between Beira and Bamboo Creek is under water, the bridge over the Pungwe at Fontesvilla is torn away…This has a highly unfavourable effect on the health of Europeans. Fever flourishes. The camps become empty…In these weeks Macequece churchyard receives what is essentially its annual increase…The Moltke now has seven tunnels, one of which is 150 feet deep and we have no accident of any description to report.”

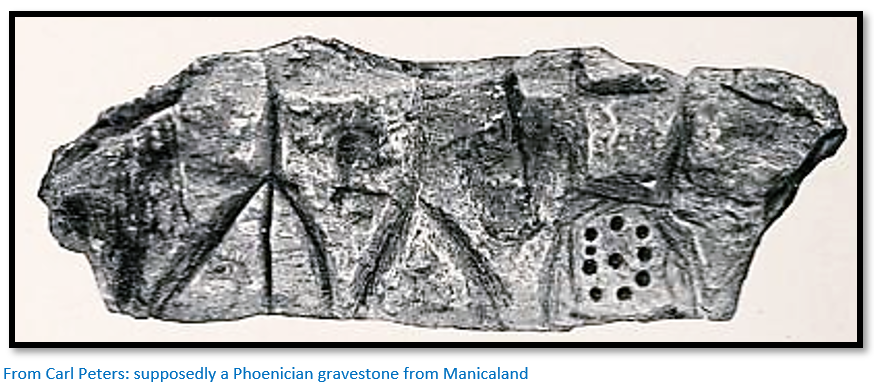

He continues with the antiquity theme. “Throughout Manicaland one finds ancient Phoenician gravestones…the mere fact of gold-mines existing on the Indian Ocean points to the influence of the two gold-seeking nations of the remotest times, to Egyptian or Arabic influences.”[xx]

He says: “Macequece (now Manica) has a European population of about seventy and is very nicely, even charmingly situated at the foot of Mount Wumba. The roads are wide and straight: they lead to the government building of the Mozambique Company to the right of which, in the middle of fine gardens, lie the offices of the Board of Mines, whose head at present is Captain d’Andrade. Macequece, apart from the Portuguese officials is in all essentials a mining camp…Krige’s Hotel, opposite the railway station is the chief rendezvous especially on Saturdays when the bar is filled with prospectors and miners of the district...’No credit today, Tomorrow the same’ is written up on all the walls and yet I suspect that many of the guests in shirt-sleeves could not raise their drinks except on credit.”

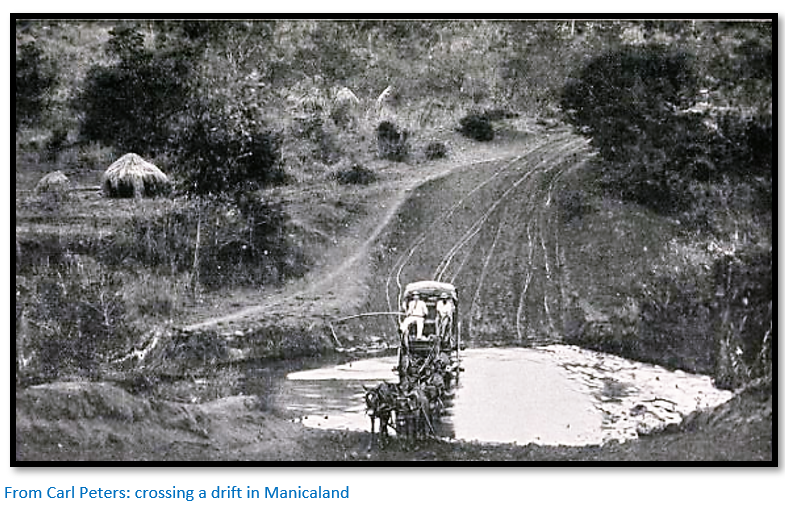

By ox-waggon on the Sabi

Peters says the mere name of this river suggests the Hebrew epoch of South African history. In fact, Sabi is the colonial name; to locals it was always the Save river. He had with him Herr Blocker and in Umtali he engaged a Mr De Gloss, a Canadian with experience in copper mining from Arizona. The entries in the book are copied from his diary and are mostly of little interest. They leave Umtali on 10 April 1900 and travel in heavy rain. On the 16 April the track crosses the Umvumvumu river three times, much as the modern road does today, and De Gloss is almost swept away in the torrent with a donkey. On 18 April they cross the foaming Nyamyaswi river and reach Bradley’s store. On this day and the next they cross the Nyamyaswi eighteen times by drift, “some of which are decidedly unpleasant.” The road winds uphill and downhill by sheer mountain-sides and through deep valleys.

“In the evening a pleasant surprise awaits me. I had several times told my ‘boys’ that my pillow lay too low. This evening I find it beautifully raised. When I turn to look how this has been done I discover that my delightful servants have placed our box of dynamite under my head.”

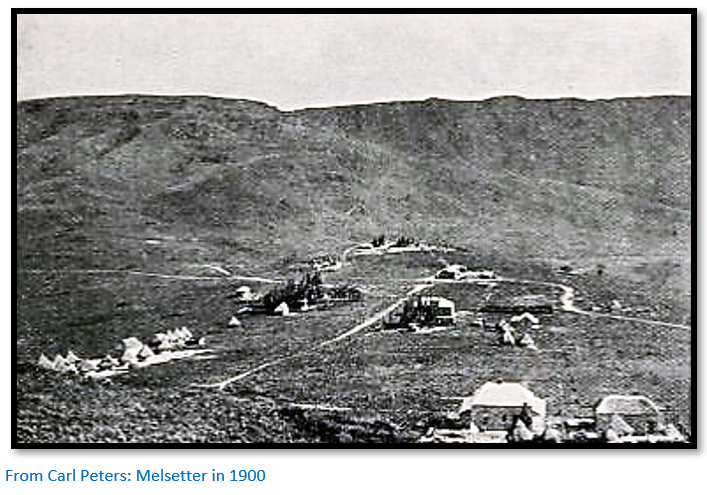

“In the morning the road passes by two Boer farms and in the afternoon we pass two more. What Melsetter requires is a couple of thousand sturdy European peasants.”

“Melsetter, by the by, is called Umsapa, or Massapa by the surrounding tribes – a survival of the Sabaean epoch.”[xxi] Much of this chapter verges on the fantastical. “I am far in advance of the column [one ox-waggon!] and find myself alone in this Rembrandtesque landscape, which has an oppressive and dreary effect on the human soul. And yet an uplifting one; for it appears to demonstrate the infinitude of our spiritual and bodily vision.”

Clearly the scenery brings out the poet in Carl Peters. “Then the night rises. But on the western horizon the sickle moon lights us with its soft glow. We come ever nearer to the scene of age-old historical activity. Already in the south-west we are shown elevations which are in the region of the Sabi where an ancient race once worked mines and erected temples and strong places”

On the 25 April, Bekker one of the Boers, brings an invitation from Mrs Moodie to stay with her for a day and wait for the Native Commissioner, Mr Meredith. Mrs Moodie has a servant who can guide them to the old copper workings and Peters moves over to “Kenilworth” the name of the farm.

Next day Mount Selinda comes in view, they pass Bekker’s farm and King’s Store and arrive at Mrs Webster’s Farm. Here they are delayed by lack of carriers as Bekker has taken his ox-waggon. Peters borrows a scotch cart from the Websters to get his personal baggage down into the Sabi valley and calls on Shlatin, the old Chief of Injambaba. He learns: “that the natives of the district who call themselves Shangaans have worked copper along both banks of the Sabi from time immemorial until about sixty years ago the Zulus had broken in under Gungunyana and made themselves master of the country. Gungunyana had taken all the copper that they possessed away from them and since then the industry had ceased.”

The following day with Shlatin’s son he reaches the camp De Closs has established in the Sabi valley. “After I had refreshed myself with a mouthful, De Gloss and I ascended to the rump of the hill, east of our camp, at whose foot we were stopping and for the first time rested our eyes on the magnificent chain of old copper mines which surprised me to the utmost. In numerous parallel rows the chain of mines generally followed the mountain slope in the direction of north to south…Everywhere we found great heaps of ores dyed green and red, the so-called tailings, sometimes we lighted on some primitive tool as well. On this afternoon we followed up these works for about one and a half miles.”[xxii]

Among big game

Peters then launches into six pages of hunting before describing attempts to establish the extent of the copper deposit. After some hours of marching to the south they reach today’s Hot Springs [see Hot Springs under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] Peters writes: “A spring sparkles from the ground, forming a little pond. I dip my hand into the water, but quickly withdraw it, for the water is extraordinarily hot; it is besides strongly impregnated with sulphur. We have discovered a hot sulphur spring. The natives tell me that when a chicken falls in, it is boiled.”

Close-by they find other old copper workings, including a claim peg by a Mr Browne who was on his way to register this claim in Umtali when he was killed by a lion. “Everywhere we met green boulders whose presence denotes copper.” The natives confirm other old workings which they estimate cover twenty miles.

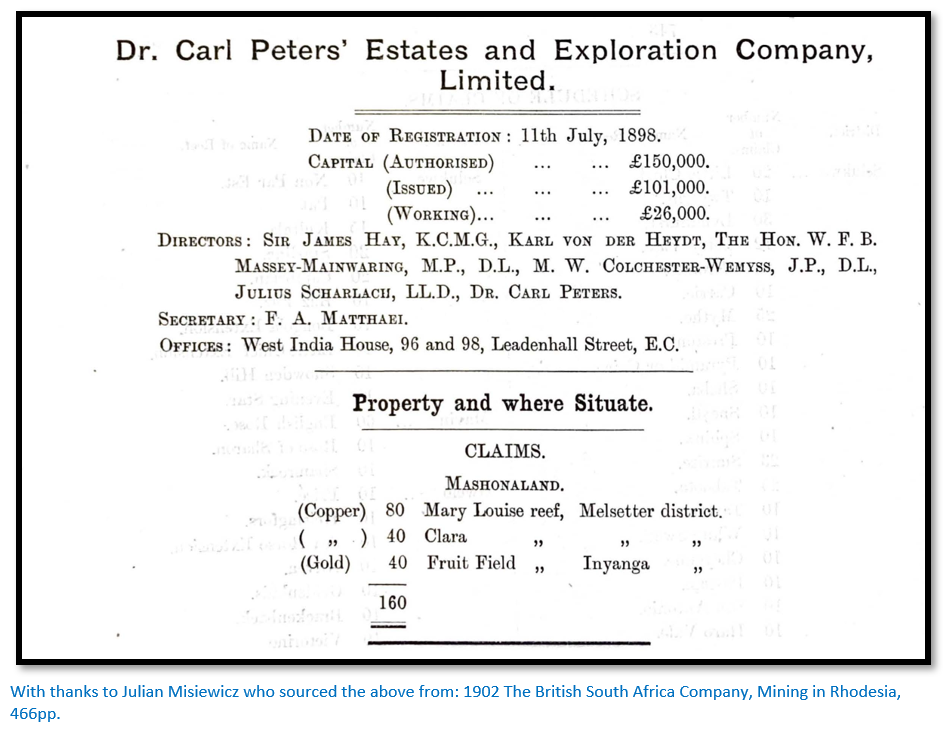

Blocker and Peters examine the old workings near the camp and establish local natives call copper masuk and distinguish it from gold delama or derama as they widen and deepen one of the tunnels at the bottom of a shaft to reach the actual copper vein. However the results are glossed over as he writes: “I need not describe these labours here in detail as they can hardly be of interest to the non-professional reader.” They register eighty copper claims above the camp and forty claims on the ground prospected by the late Mr Browne which are recorded in Umtali as the “Marie Louise” and “Clara” claims.

Nine or so more pages are dedicated to Peters’ very conservative views on the native labour situation before we hear that mining operation conclude for Carl Peters in the Sabi valley on 13 May 1900. “To form a clear opinion about South Africa considered as an ancient Eldorado one must regard the Sabi chain of copper mines as the necessary complement to the goldmines of Mashona and Manicaland…that have been worked from time immemorial in this part of the earth.”

Of the area in general he writes: “The journey had lasted exactly six weeks and seldom in my life have six weeks had so strengthening an effect on my health as these. More fresh and energetic I have never felt than on the return from my expedition to Sabi. Melsetter, now Chimanimani may be regarded as the sanatorium of South African.”[xxiii]

Two further details confirm to Peters satisfaction that the country is the source of gold for Solomon’s Temple and copper from the Egyptians voyages to the land of Punt. First, Rhys Fairbridge a surveyor and keen amateur archaeologist showed Peters some copies of rockart paintings he had made: “The pose of the figures, the character of the drawing, the head-dress, reminded one at the first glance of the frescoes in Egyptian temples and made us both decide on the influence of ancient Egyptian culture.”

Mr Birch, the chief of police who has already given him 34 coins[xxiv] allegedly found at Nyanga, now gives him the upper part of a statuette found somewhere south of the Zambesi. Professor Flinders Petrie, the Egyptologist confirms it is an Egyptian relic. Peters concludes that these objects take “the old copper mines to a higher and more general plane.”

This concludes Carl Peters stay in the country. He left the management of the Mount Moltke Mine to a Mr Eyre[xxv] and that of the Windahgil Mine to a Mr Bull and left the country on 11 June 1900 with Herr Blocker by the Beira and Mashonaland Railway after spending two years in the territories of Mozambique and Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe.

Last Chapters entitled The Gold of Ophir / Before the time of Solomon / An Ancient Eldorado / Goal of the Voyages to Punt / Connection with Ancient Egypt / The Future of Ancient Ophir / Advance of the White Race

The last chapters are an attempt by Peters to force the details from any ancient source into his own fantasy framework and are not considered by this author to have any relevance.

Peters visit to Macombe in the area known as Barwe is significant because the area had resisted Portuguese authority and was the last vestige of the Mwene Mutapa State to retain its independence. Three years after his visit to Macombe the area was overrun by Coutinho’s forces, Inhachirondo (Missongue) was burnt down and the Macombe (Canga) whom Peters described was killed and large numbers of tribes people fled to Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe. In 1917 the Macombe rose again against the Portuguese and drive them out of the area south of the Zambesi from Zumbo to Gorongoza except for Tete which was cut off.

Peters has an ambiguous attitude towards the British South Africa Company and Rhodes. He was distrustful of capitalism in its ability to run a colony as it would be more interested in paying dividends to the shareholders than in establishing a sustainable colony. He is very critical of the notion of companies buying up large swathes of land which then lie dormant until the next land boom increases their value. This criticism was shared by many settlers in the early Rhodesia.

He writes of German peasants settling in the Melsetter area and this chimes with his ideology that people without capital, with nothing but their personal skills and own energy were the only people able to develop a new country as they had to work to survive.

The Chartered Company’ native policy did not impress him at all since he believed that Africans were designed by God to labour and this was a policy that was widely followed in the German colonies.

His own temperament favoured agriculture over mining, but he was forced to recognise that the future of both Portugal and Rhodesia lay in their mineral wealth. Ironically he was correct that in the future agriculture did dominate over mining.

Life and Career

1856

27 September: Carl Peters is born the eighth of nine children of a Lutheran clergyman Johann Peters in Neuhaus upon Elbe in Hanover, Germany. Travel books in his father’s library seem to have been his favourite reading as a child.

1876-1879

Studied history and philosophy in Göttingen, Tübingen and the Humboldt University of Berlin financing his studies through a scholarship and through journalistic work. Publishes the novel "Wrested and Achievements" under the pseudonym C. Fels.

1879

Completes a Doctorate in history at Berlin University and is awarded a gold medal by the Frederick William University for his dissertation on the 1177 Treaty of Venice in history and passes his teaching exam but decides against completing the legal traineeship as a high school teacher. Publishes "Arthur Schopenhauer as a writer and philosopher" in which Schopenhauer’s view that every person should follow their special destiny also became his view.[xxvi]

1880-1883

Moves to London and lives with his recently widowed maternal uncle Carl Engel[xxvii] where he immerses himself in colonial politics and analyses its significance for the British Empire. Publishes "Das Deutschtum in London" and "Willenswelt und Weltwille."

1883

Carl Engel wanted Peters to take up British citizenship but Peters wanted to stay German. On the eve of re-marrying, Engel committed suicide, Peters was his executor and left a generous inheritance which would facilitate an academic career and once the will was settled he returned to Berlin.

1884

The growth of German industry had resulted in an increasing demand for raw materials and German political thinkers were saying that a quick and decisive foreign policy was required to gain colonial possessions to ensure that supply was assured. Peters with a small circle of friends founded the "Society for German Colonization" (Gesellschaft für Deutsche Kolonisation, GfdK) which was essentially a pressure group[xxviii] in favour of the establishment of colonies in Africa as a source of raw materials and as a destination for German exports and for strengthening German’s political influence in world affairs. It has the aims of “a capitalist group for annexation and later for administration of the largest possible colonial countries under the German flag.” Peters proposes to the committee "to acquire land for the Society for German Colonization in Usagara on the east coast of Africa, opposite Zanzibar, if this is not possible, at another point on the east coast” and that Peters carry out this task with the proposal ending: "The Committee expresses the firm expectation that the gentlemen will never return to Germany without having completed the purchase of suitable land somewhere.”

In November Peters went overland with two companions, Count Joachim von Pfeil and Karl Ludwig Jühlke to present-day Zanzibar. Here they met Kurt Töppen who had been working on the island for years and travelled to the mainland several times on behalf of his company, understood Swahili and knew how to deal with the natives.[xxix] The party that marched inland up the Wami river was comprised of the four Europeans and forty-two Africans, thirty-six of whom were porters armed only with spears and another six servants armed only with muzzle-loaders. On the tenth day of the march they managed to conclude commercial and protection treaties (Schutzverträge) with the chief of Nguru, followed by treaties with Useguha, Usagara and Ukami in present-day Tanzania even though they did not have the support of the German government. The treaties, written in German to chiefs who did not understand their contents and with interpreters giving a totally fake version of what was written, conferred all rights to exploit the territories on The Society for German Colonization in exchange for some inexpensive gifts.

Part of the reason that Peters met with such success was that the activities of Arab slavers over the centuries had left most of the tribes fragmented and on hostile terms with each other and the violence which affected the whole region was ideally suited to Peters’ methods and character. The chiefs calculated that having a European ally would help them against their neighbours, at the same time protecting them against the slavers.

Peters had injured his foot and had to conclude the three remaining treaties from a hammock; they all suffered in the intense humidity and on the return journey the porters had to be forced to continue at the point of a revolver. Peters thought he was dying and implored Jühlke to not even bury him but continue on to the coast which was reached safely the next day. Jühlke later died in Somalia.

In Zanzibar the German consul Gerhard Rohlfs made Peters aware of a decree from the Federal Foreign Office that states that if "a certain Peters" wanted to set up a colony in the area of the Sultan of Zanzibar was not entitled to German imperial protection or even security for his life.

From 15 November 1884 Germany hosted the Berlin Conference that fuelled the “Scramble for Africa.”

1885

Returning to Germany Peters formed the German East Africa Company and demanded official protection status for the areas covered by the treaties. The German government of Otto von Bismarck initially feared a negative reaction from the British government and refused to back Carl Peter’s plans for an imperial charter. The Sultan of Zanzibar objected to the treaties with the chiefs, but Peters refuted his claim.

He threatened to sell the treaties to King Leopold II of Belgium who was eager to expand his territory in the Congo. Bismarck’s National Liberal Party allies in the Reichstag Parliament were pro-colonial, so Bismarck backed down and issued the first Imperial letter of protection (i.e. an imperial charter) for these acquisitions by which the German government committed to providing military protection to its overseas territories. One day after the end of the Berlin Conference on 27 February 1885, the GfdK obtained an imperial charter signed by Emperor Wilhelm I.

However the Sultan continued with his objections backed by the English Consul-General Dr John Kirk until German warships under Admiral Eduard von Knorr made an official visit to the port of Zanzibar to fly the flag and after openly aiming their guns at the Sultan’s palace he agreed to back down with his objections and on 20 December 1885 signed a “treaty of friendship” recognising the territory of German East Africa.

1886

The Society for German Colonization was transformed into the German East African Company modelled on the East India Company with a mandate to acquire additional territory and a policy that “fast, bold, reckless action is made a must.”

Peters accompanied Privy Councillor Dr Krauel to England and secured for Germany the area of Kilimanjaro with England recognising German East Africa as being a German colony. German promised not to expand north of the Lake Victoria area, but other regions are open for expansion.

1887

Carl Peters became chairman of the "German-African Society" and on his second trip to East Africa charmed the Sultan of Zanzibar Khalifa bin Said with his knowledge of the Koran and eastern religions and also the Sultans’ family, the old ruling class of Muscat. They signed a 50 year agreement that the German East Africa Company would run the administration of the entire coast including the leasing of all customs duties from the mouth of the Umba river on the current Kenya / Tanzania border to Cape Delgado where the nearby Rovuma river provides the current Tanzania / Mozambique border. The only consideration for the Sultan being that “surpluses, if any” would go to Zanzibar. An area of 900,000 square kilometres which is now an asset of the German East Africa Company has doubled the overseas territory of the German Empire.

Despite the book Germany as a Colonial Power describing Peters as a “success beyond expectations” the German government soon demanded that only a certain amount be deducted from the customs revenue which removed any “elasticity” in the administration costs.

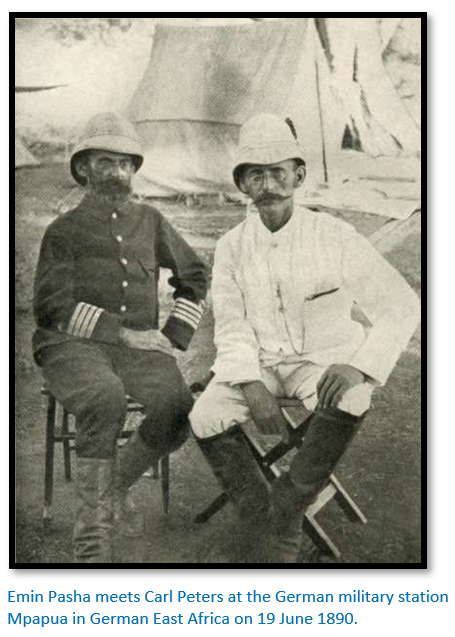

1889/90

Peters led a German expedition from the east coast ostensibly to search for Emin Pasha, a German Silesian who has been administering the Equatorial province in southern Sudan as an official of the Egyptian government and had been out of touch for two years due to the Mahdi uprising.[xxx] In reality this was a flimsy excuse to extend German territory to include Uganda and Equatoria and the headwaters of the Nile river.

This action was not supported by the Germany government who said: "the Federal Foreign Office refuses to mediate or support you" and was regarded by the British as a land grab. They only allowed Peters to take hunting rifles and a force of twenty Somali soldiers and seventy porters and only Lieutenant Adolf von Tiedemann to accompany him. Pack animals died, food and water became short, porters ran away and some had to be chained up at night to prevent them escaping. Local tribes became increasingly hostile as they reached the upper reaches of the Tana river demanding bribes for the expeditions’ passage which Peters refused to pay. Clashes broke out with the Oromo people called ‘Galla’ who attempted to rob the expedition and then with the Obbo and Maasai when again Peters refused to pay tribute.

Finally he reached Bagamoyo with Adolf von Tiedemann and signed a treaty with Kabaka Mwanga II of Buganda, a Kingdom within Uganda. This was part of Peters’ grand strategy to link the Atlantic Ocean with the Indian Ocean with Uganda as the lynch-pin.

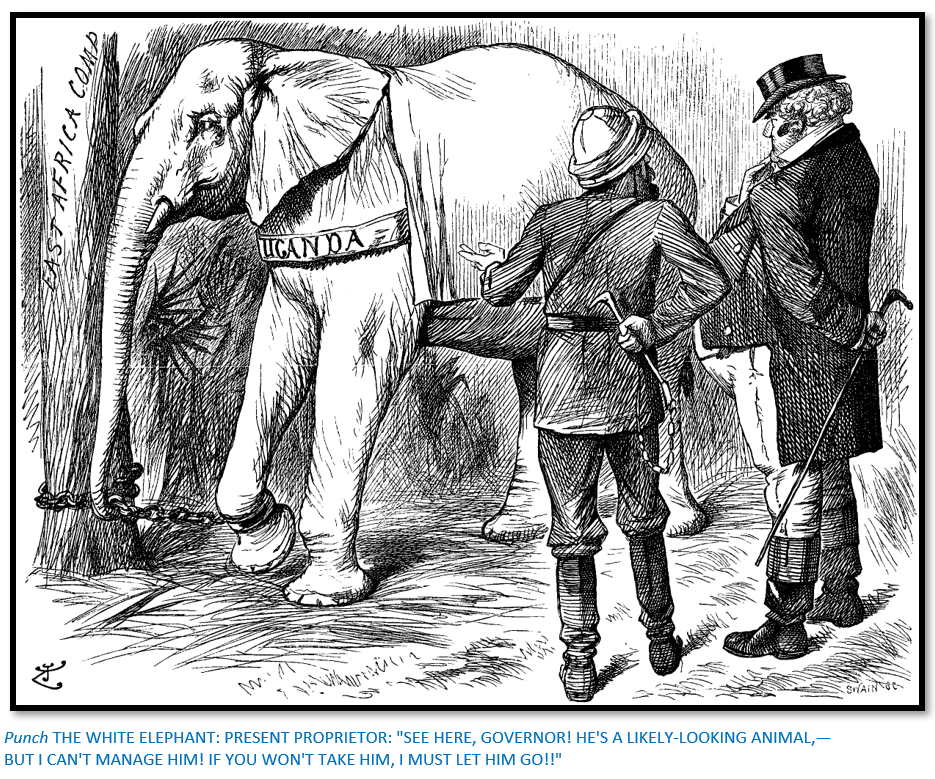

Despite this apparent success Peters had to leave Uganda hurriedly as a British expedition commanded by Frederick Lugard of the Imperial British East Africa Company was approaching rapidly.

At the time Uganda was seen as a white elephant for the Imperial British East Africa Company, which was administering the territory, the cost of which was out of proportion to its potential wealth; this dilemma is illustrated in the Punch cartoon below. The African Explorer (the British East Africa Company) attempts to sell his white elephant to a wealthy man (the British Government) By 1894 the British Government had assumed the administrative duties of the territory and established the Uganda Protectorate.

1890

Once he arrived back in Zanzibar Peters learned that all his efforts had been in vain as on 1 July 1890 the Helgoland-Zanzibar Treaty had been signed between Great Britain and Germany renouncing German political interests in Uganda and made Peter’s agreement with Mwanga void, thus undermining his ambitions for a large East African colonial empire.

In present-day Tanzania the coastal population rebelled against the Sultan of Zanzibar’s lease agreement with the German East Africa Company: the situation became so serious that German troops were called in. Hermann Wissmann, a soldier turned explorer was appointed as Reichskommissar for German East Africa and given the task of putting down the Abushiri Revolt led by Abushiri ibn Salim al-Harthi with just one order: "Victory." He was harshly attacked for burning villages and laying waste to agricultural fields, executing great numbers of natives and tolerating no opposition. The insurrection was put down, Abushiri was arrested and executed and the German government assumed ownership of the German East Africa Company’s possession as a colony.

1891

Peters protested vigorously against the Helgoland-Zanzibar Treaty and with Alfred Hugenberg founded the General German Association (from 1894: Pan-German Association) with the stated aim of promoting an expansive German colonil policy in Africa. On his return to Germany Peters was fêted by the press and published an account of his expedition to Buganda called Die deutsche Emin Pasha Expedition (the German Emin Pasha Expedition)

1891-1895

Now at the height of his fame in 1891 and with a status in Germany equal to that of Livingstone, Stanley or Rhodes, he was appointed Reichskommissionar (Imperial High Commissioner) for the Kilimanjaro region in Moshi. Next year he was involved in negotiating the German-British border settlement between Kenya and German East Africa with the British East India Company.

In 1893 his brutal actions against the local population triggered a rebellion which was to cost Peters his office. Briefly a local woman called Jagodia used by Peters as a lover had an affair with his man-servant Mabruk. When he found out they were both sentenced for theft and treason and hanged by court-martial and their home villages destroyed. The incident was not reported until the local Chaga people broke out in rebellion and had to be crushed with military force.

Carl Peters was not very squeamish when it came to implementing his goals on the local population where he was given the unflattering nickname of “Mkono-wadamu – the man with bloody hands.” In Germany he was accused of cruel treatment of the African population and recalled to Berlin where he was employed by the Imperial Colonial Office from 1893 to 1895. In 1896 the killings became public and Peters was forced to admit to them.

Many of his contemporaries shared the same views and he did not act alone. Eduard von Liebert was governor of German East Africa from late 1896 to 1901 and his massive tax increases caused widespread resentment and unrest which resulted in his being relieved of his position. He also held the same racial theories; in 1904 becoming the founding chairman of the Reich Association against Social Democracy in Berlin, a member of the executive board of the All-German Association, a member of the board of the German Colonial Society and in 1909 was one of the initiators of the right-wing conservative German Women’s Association.

1897

Following disciplinary hearings and the disclosure that Peters had written to Bishop Tucker, the Anglican Bishop of Eastern Equatorial Africa admitting guilt, he was dishonourably removed from office as Reichskommissionar for abuse of office, losing all his pension benefits. The judgment was sharply criticized in public by nationalist associations and some politicians.

Disgusted with the way events had turned against him, Peters avoided further criminal prosecution by permanently relocating to London where he founded the company Dr Carl Peters Estates and Exploration Company (later: South East Africa Ltd) which has as its aim to finance the exploitation of gold deposits in Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe and Portuguese East Africa, now Mozambique.

1899-1905

Peters made six trips to Angola and Rhodesia for his company during which he explored the Makaha district of north-eastern Rhodesia and travelled down the Manicaland Province from its northern to its southern end and this forms the substance of this article.

He claims to have discovered ruins of cities and deserted gold mines of the Mutapa State, which he also identified as the legendary ancient land of Ophir. In 1902 he published Im Goldland des Alterums, The Eldorado of the Ancients.

1904

Publishes "England and the English."

1905

Peters is given the title Reichskommissar aD by Kaiser Wilhelm II and visits the Save river region in present-day Zimbabwe.

1909

Marries Thea Herbers.

1911

Sells all his shares in the South East Africa Ltd Company.

1914

With the outbreak of the First World War much of his company’s assets are confiscated and Peters and his wife returned to Germany where his reputation was completely rehabilitated by Wilhelm II who restored his pension from his personal budget. Amongst the German colonialists he is honoured as a national hero.

1914-1918

Lives in Hanover, Berlin and Bad Harzburg and publishes "African Heads," "South African Mine Life," "For World War I" and "Memories of Life."

1918

10 September Carl Peters died in Bad Harzburg from heart failure.

Legacy

A number of towns in Germany had streets named after Carl Peters, but more recently they have been changed after criticism of his legacy and the colonial policies he espoused. Germany’s largest colony, German East Africa along with its other colonial possessions in South West Africa, Cameroon and Togo were lost in 1919 by the Treaty of Versailles.

A statue of Carl Peters was cast in 1914 by the German sculptor Karl Möbius and sent to Dar-es-Salaam, but because Germany lost its colonies in 1919 the statue was transported back to Hamburg where it remained in the cellar of the shipowner until erected in 1931 in Heligoland. This was because Peters was involved in the Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty of 1890 when Germany gained the island of Heligoland. During world War II the statue was destroyed with only the bust remaining intact. In 1966 the bust was placed on a column on Heligoland’s Strandpromenade, but is now in the museum garden.

References

S. Eckelmann and M. Wichmann at the German Historical Museum, Berlin for biographical details

C. Peters. The Eldorado of the Ancients. Books of Rhodesia Silver Series, Volume 16, Bulawayo 1977

M. Reiss. The Disgrace and Fall of Carl Peters: Morality, Politics, and Staatsräson in the Time of Wilhelm II. Central European History. Vol. 14, No. 2 (June 1981), pp. 110-141

Wikipedia: Dr Carl Peters

Wikipedia: Society for German Colonization

web.archive.org/web/20060114012814/http://www.jadu.de/jaduland/kolonien/text/kpeters.html

www.wintersonnenwende.com/scriptorium/deutsch/archiv/grossedeutsche/gdtPeters.html

wikivisually.com/wiki/Carl Peters

[i] M. Reiss

[ii] M. Reiss

[iii] C. Peters, P2

[iv] The northern estuary of the Zambesi near Quelimane is choked with sand and unnavigable.

[v] On Peters P82 Blocker is described as “a German forester and a hunter by profession.” Is this the same Blocker who worked for F.C. Selous in 1896? [See the article Selous House near Esigodini under Matabeleland South on this website]

[vi] Peters, P62

[vii] Ibid, P74

[viii] Ibid, P72

[ix] Ibid, P101

[x] Ibid, P127

[xi] Peters is correct here. The Mutapa State collapsed under the succession struggles and invasion by the Rozvi and the remnants moved south of Tete where they resided from 1803 to 1902 and finally collapsed after the death of its last Mambo Cioko Dambamupute.

[xii] Mt Nyangani the highest peak is 2,592 metres (8.504 feet)

[xiii] Peters, P154

[xiv] Ibid, P161

[xv] Ibid, P164

[xvi] E.C. Broadbent who died in 1898 during the construction of the Africa Transcontinental telegraph line is buried here in the Nyanga cemetery with a Loyal Women’s Guild Pioneer Memorial Cross. He led the party at The Siege of Deary’s Store at Abercorn June 21st – July 13th, 1896 under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

[xvii] Many prominent authors have asserted that these pit structures housed hornless dwarf cattle and goats, but Anne Kritzinger in a booklet The Gold-Mining Landscapes of Nyanga has done geological surveys which she believes have resulted in gold values at these sites being higher than expected and has considerable support from mining engineers and metallurgists to support her claim that these were part of an early gold-mining industry.

[xviii] Peters, P176

[xix] In a short article in Nyame Akuma No 83, June 2015 Anne Kritzinger gets confirmation from German mining archaeologist Dr Martin Strassburger that “pit structures have nothing to do with agriculture” and were he believes, purpose-built for the gravity concentration of gold.

[xx] Ibid, P224

[xxi] Ibid, P244

[xxii] Ibid, P259

[xxiii] Ibid, P284

[xxiv] The coins are a complete mish-mash comprising one gold and some silver and copper European coins and a number of Graeco-Indian and Indian coins which might have been part of an amateur Victorian collection.

[xxv] This not either of the two early settler Eyre brothers; Herbert Eyre was killed at his farm on the Great Dyke in June 1896, Arthur Eyre died in March 1899. Source: R. Burrett. The Eyre Brothers: Arthur and Herbert. Heritage of Zimbabwe Publication No 9, 1990.

[xxvii] Carl Engel was a distinguished composer and musical essayist

[xxviii] Wikipedia

[xxix] Dr A. Wirth

[xxx] Unknown to Carl Peters Emin Pasha had already been relieved by H.M. Stanley and an expedition sponsored by British interests.