The Beira and Mashonaland Railway – the Contractor’s stories

The railway was an important element of the country’s development and many excellent articles have appeared both in Rhodesiana and Heritage Publications over the years. I have used extensively the books written by Anthony Croxton [Railways of Zimbabwe] and Edward Hamer [Steam Locomotives of Rhodesia Railways] and there are good websites at www.geoffs-trains.com and mikes.railhistory.railfan.net. After an annual summary of events this article covers the construction of the Beira and Mashonaland Railway through the personal accounts of Henry Francis Varian [Some African Milestones] and George Pauling [The Chronicles of a Contractor] who were responsible for actual construction of the Beira – Salisbury section with a few personal accounts from travellers who travelled along the railway line during the conversion from 2 ft gauge to the standard 3 ft 6 inch gauge including Lt-Col. Alderson’s account [With the Mounted Infantry and the Mashonaland Field Force 1896]

Cape to Cairo Railway

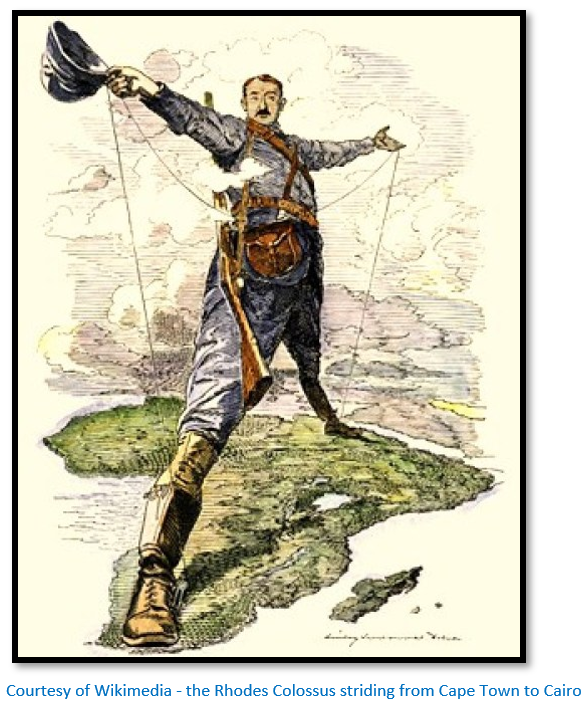

Cecil Rhodes dream was for a continuous line of pink of over 7,000 kms from South Africa to Egypt and the railway was seen as the way to establish that ambition. The plan of a Cape to Cairo railway did not originate with Rhodes but in 1890 he had made a fortune through the De Beers diamond mining company and was the Prime Minister of the Cape Colony and he saw the railway as a crucial element in creating the communication and trade links of an empire-building project that would establish Britain’s dominance in southern Africa.

Transport before the railways

Varian explains that prior to the advent of the railways transport was dependent on native porters and carriers and the ox-wagon. Transport by humans was flexible and reasonably fast, but the loads that could be carried were comparatively light. The ox-wagon had serious limitations in that it required roads, however rough, drifts at river crossings and feed for the trek oxen at the outspans and travel by ox-wagon was only possible in country where there were no tsetse fly. Oxen were also vulnerable to rinderpest which crossed the Zambesi River in 1896 and decimated 80 – 90% of cattle, buffalo, eland, giraffe, wildebeest, kudu and antelopes and in South Africa alone the losses amounted to over 2.5 million cattle (there is an article on Rinderpest under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com)

The human carrier’s performance depended on the type of country and the load carried; with loads of 27 – 36 kgs (60 – 80 lbs) distances of 24 – 32 kms (15 – 20 miles) might be achieved. Ox-wagons typically carried 2,700 – 4,500 kgs (6,000 - 10,000 lbs) over 19 – 23 kms (12 – 14 miles) in two treks made every 24 hours pulled by eighteen oxen. The first trek began about 4pm when the voorlooper would crack his whip and bring the oxen back to the wagon for in-spanning. Trekking began at 5pm and lasted until 9pm when the oxen were unyoked and tied to the trek chain to lie down and chew the cud. Two or three fires were lit around the camp to scare off lions and for the evening meal. Dry firewood was collected and stacked for use during the night. After supper everyone slept, rising about 2am when the second trek began and ended just after sunrise at 5am. During the day the oxen were let out to graze with a herder, and the wagon conductor or driver, the voorlooper and other assistants would take long naps, just waking to check on the oxen. All passengers followed their example as it was difficult to sleep whilst the waggons were trekking due to the wheels constantly bumping against boulders and stumps.

Where roads existed the Cape cart, drawn by mules or horses could average 56 kms (35 Miles) per day and the Zeederberg coaches could do 240 kms (150 miles) or more, depending on weather conditions, in a twenty-four hour run carrying ten passengers and 1,016 kgs (1 tonne) of mail and baggage through day and night, with constant changes of mules every 16 – 24 kms (10 – 15 miles)

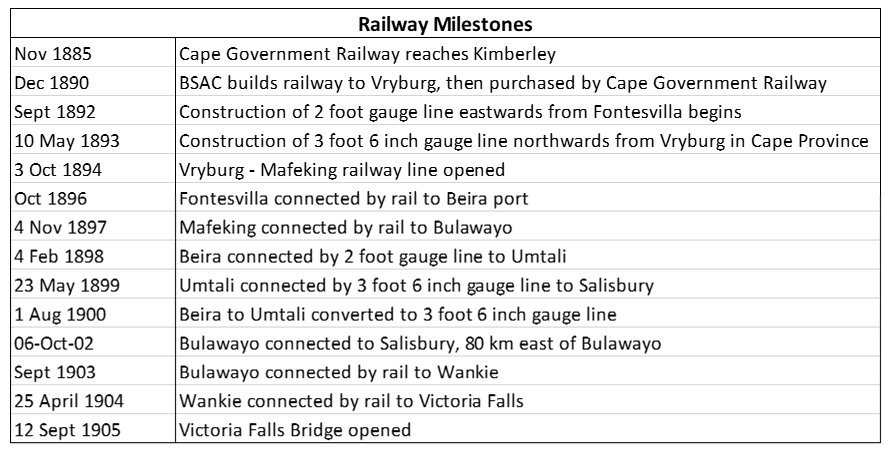

Summary of railway development in central Africa

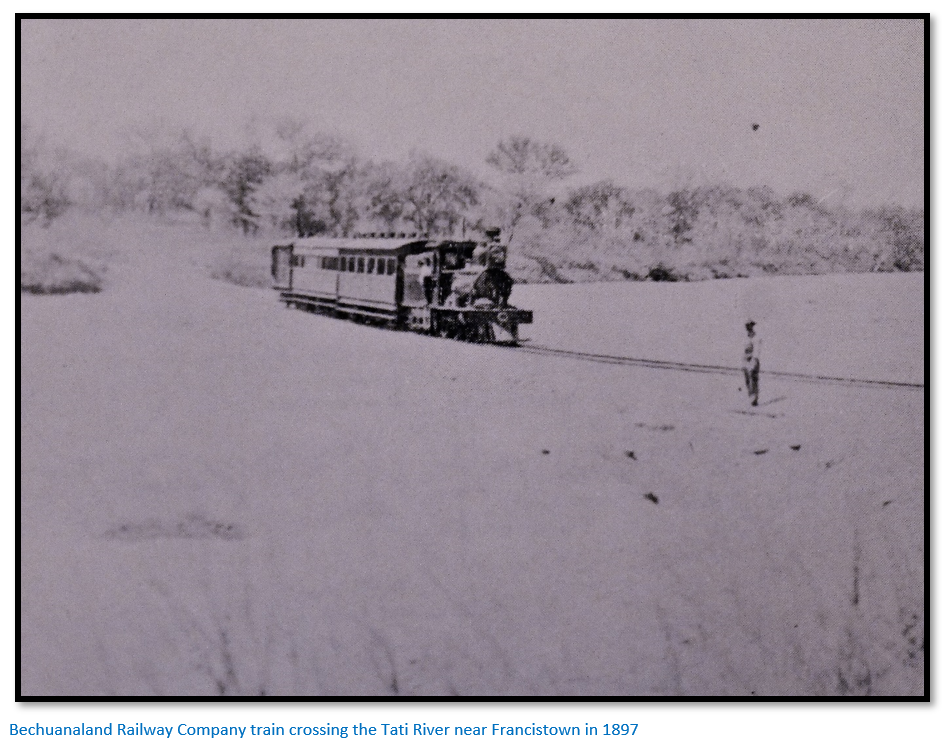

By 1890 the railways had reached Vryburg 1,246 kms (774 miles) inland in order to serve the interests of the Cape Colony and Rhodes realised that the extension of the Cape railway system was essential for the development of Mashonaland which had been occupied in 1890 and Matabeleland in 1893.

There were several proposals to connect Mafeking with Bulawayo by light railway, but it was not until 1896 when the Matabele rebellion or Umvukela broke out together with the rinderpest outbreak that the shortage of oxen put freight charges up to £200 a ton over the 965 kms (600 miles) between the two towns that the project assumed a vital urgency. Rhodes commissioned the line construction from George Pauling and the railway was operational by November 1897.

From then onwards Rhodes devoted his energy to railway development and although his dream of a Cape-to-Cairo railway scheme never occurred, the spread of ‘pioneer railways’ from Vryburg in the south to Beira in the east, the Congo in the north and Lobito in the west occurred.

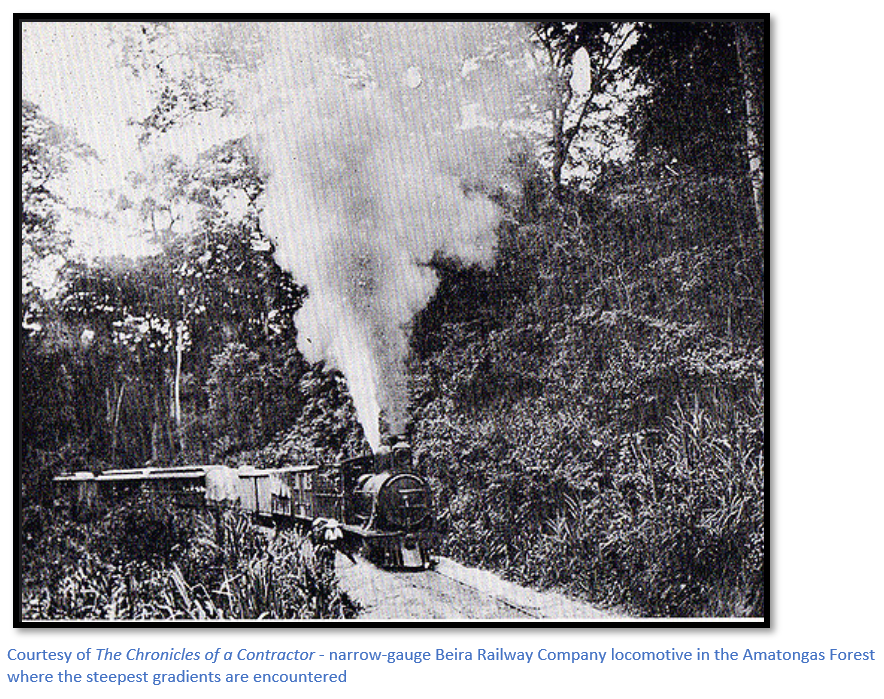

These pioneer railways were initially always lightly constructed to meet the conditions of the country and to minimise costs. All construction materials came from bases in the rear, bridges and culverts were temporary to be replaced with more permanent structures later when they were justified by sufficient freight revenue. For this reason they always followed the line of least resistance along the watersheds and avoided river crossings with earthworks and cuttings reduced to the minimum. The greatest difficulties were always ascending from the coastal plains to the central plateau as here the steepest gradients were encountered and the heaviest engineering works required as in the Amatongas section of the Beira and Mashonaland Railway.

Year by year development of the railway system from 1890 to the formation of the Beira and Mashonaland Railway in 1900

1890 - Within a week of the Pioneer Corps being officially disbanded on 1 October 1890 Frank Johnson, Dr Jameson and a Trooper named Hay had left Salisbury to investigate a route from the east coast into Mashonaland. Johnson tells of their series of mishaps in Great Days in a collapsible boat down the Pungwe River, but everyone realised the potential of this much shorter 330 km route.

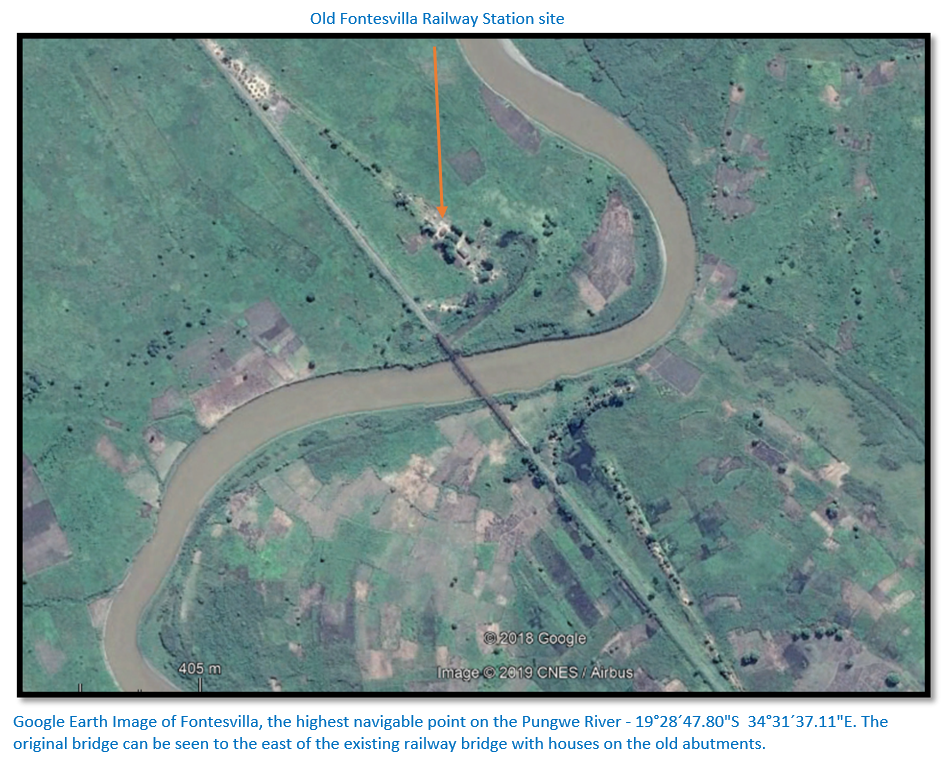

Rhodes soon realised that the existing firm of “Johnson, Heany and Borrow” was undercapitalised and could not possibly fund the development of a road and coach service from Beira to Mashonaland. He persuaded Johnson to form a new company “Frank Johnson and Co. Ltd” with an issued capital of £200,000 (Rhodes was Chairman and Johnson Managing Director) The ever-confident Johnson sent Selous to open a road through Mashonaland down which were sent wagons and coaches; Johnson planned to bring tugs to tow barges up the Pungwe River from Beira to Fontesvilla, the highest navigable point on the Pungwe River.

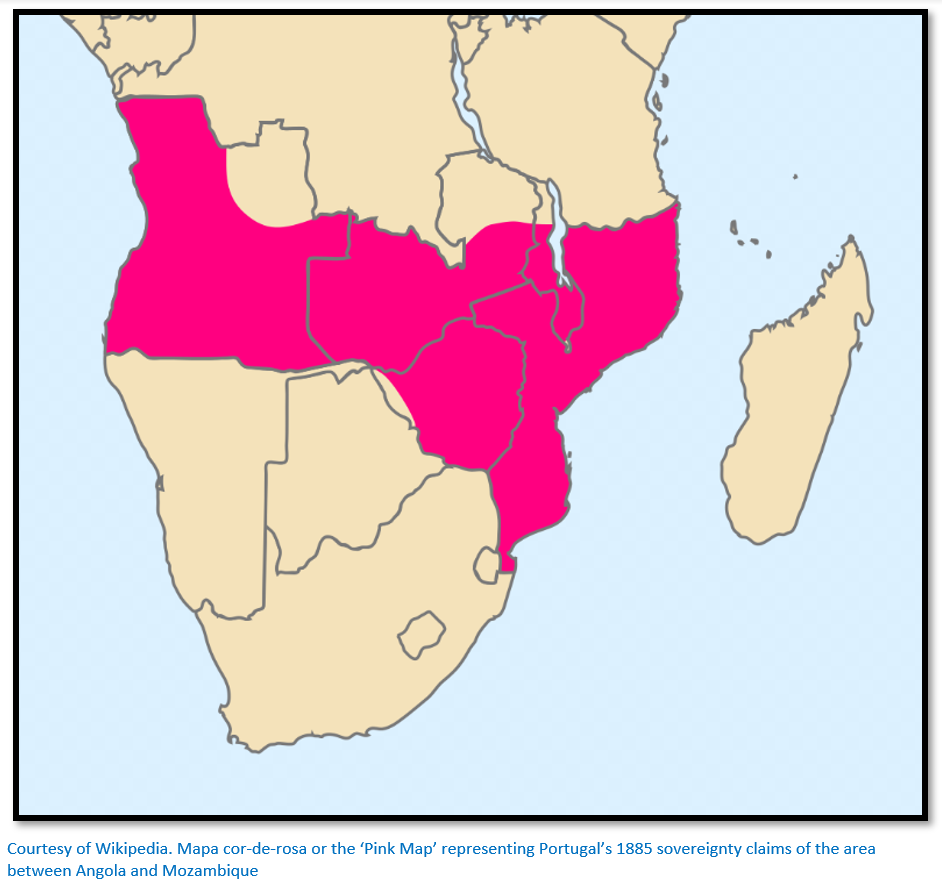

However the occupation of Rhodesia, which ended Portuguese dreams portrayed in the Pink Map and the humiliation of the arrest of D'Andrade and Gouveia by Forbes at Mutasa's Kraal in November 1890 infuriated the Portuguese public and officials in Portuguese East Africa.

1891 – Consequently when Sir John Willoughby arrived at Beira on 13 April 1891 in the Norseman with two tugs the Agnes and Shark, he found the Portuguese officials under their Governor Colonel Machado, unhelpful and belligerent. They refused to accept the 3% customs due for goods in transit and when Willoughby lifted anchor and got under way a Portuguese gunboat, the Tamega, fired a blank shot across his bows and he was ordered to stop. The Governor was courteous, but his officials made no effort to conceal their hostility and British residents in Beira were threatened. The Pungwe River under previous agreements was open to British shipping and this resulted in an international incident between the Portuguese and British authorities.

The subsequent Anglo-Portuguese Treaty of 11 June 1891 provided for the recognition of the Pungwe as an international waterway, for freedom of movement of people and goods between Beira and Manicaland, to limit transit duty fees to 3% for twenty-five years and for the building of a railway to connect Mashonaland with the east coast at Beira. No timetable was set, but the rail survey was to be completed within six months. The Portuguese Government agreed to construct the line from Fontesvilla, 80 km up the Pungwe River and near the site of the present Pungwe Bridge (Ponte do Pungwe) to Manicaland. The exclusive rights were ceded to the Companhia do Mocambique, but as it was almost bankrupt, a concession was granted in September 1891 to Henry Theodore van Laun of London.

In exchange for forming a railway company with a share capital of £600,000 and debenture capital of £1,500,000 van Laun was given the right to build the railway including stations, docks and quays and to blocks of land along the railway line each five square kilometres in extent as long as they were not adjacent and the 3% transit duties to offset the cost of the debenture interest.

Rhodes first journey into Mashonaland with Frank Johnson and de Waal through Penhalonga on 9 October 1891 is described in an article under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

In December 1891 Rhodes’ British South Africa Company (BSAC) took over van Laun’s contract in return for a down payment of £10,000 and £295,000 of fully-paid up shares in the new railway company.

1892 - The Beira Railway Company was formed in July 1892 the 600,000 shares being issued at no par value; 305,000 issued to the subscribers for the £250,000 of 6% Debentures secured on the first 113 km (70 miles) of railway from Fontesvilla to Mandegos (now Chimoio) and 295,000 in the name of the Companhia do Mocambique. Late contractual changes allowed the Beira Railway Company to charge the 3% transit duties to revenue and to set its own dock and warehouse and transport charges – in effect, granting a monopoly.

During the year Roach had managed to build a rough road from M’pandas, just north of Fontesvilla, to old Umtali (this is shown as the dashed line on the map) but the tsetse fly problem and the three weeks it took to travel between Fontesvilla and Salisbury meant this route would never be commercially viable; both Johnson and Rhodes realised after their previous year’s trip that a railway was a necessity. This failed project cost Johnson £25,000.

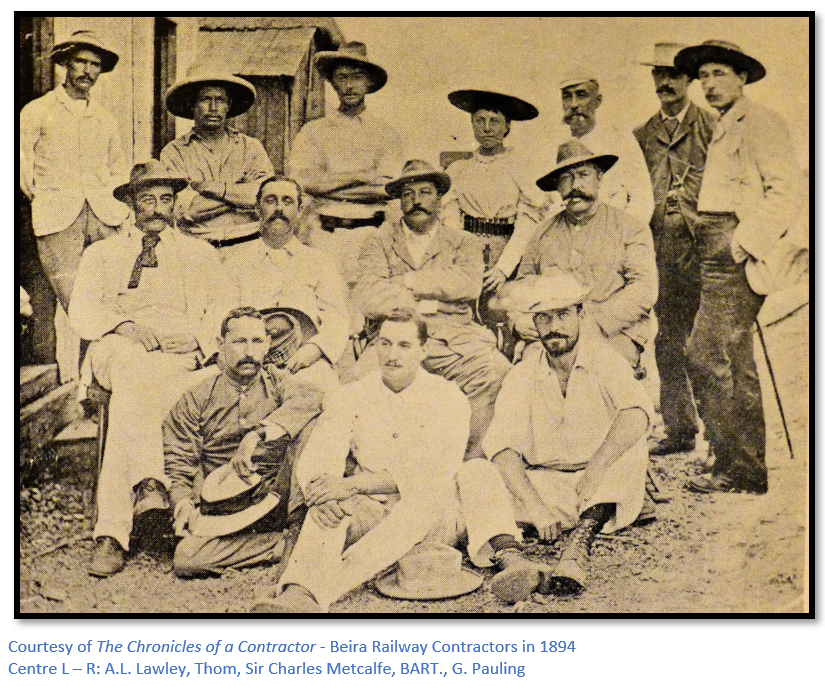

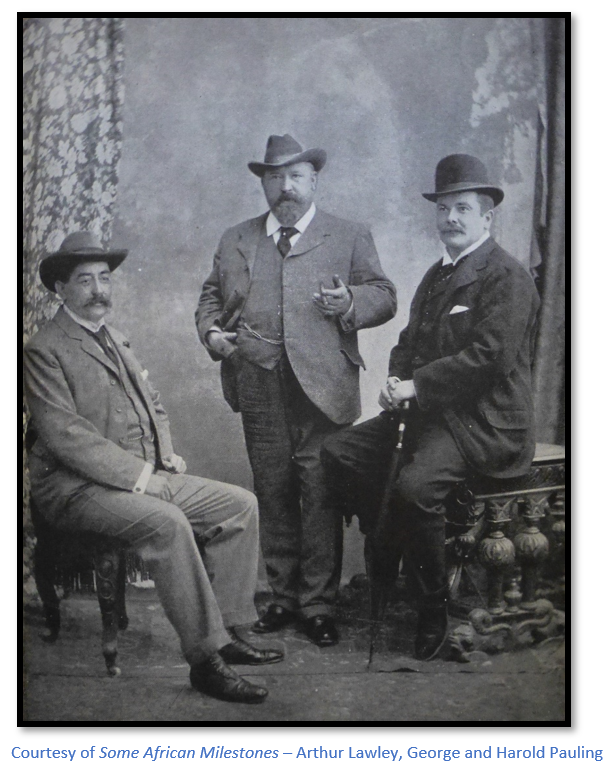

Alfred Beit on behalf of Rhodes called for tenders for the construction of the first section. Frank Johnson was their agent and put in a bid to build the railway, but he writes, the Directors of the BSAC decided that "a firm with more experience of railway building" should do the work. George and Henry Pauling, who had already built railways in South Africa were awarded the contract with Alfred Lawley, who had tendered his own contract bid, as chief engineer.

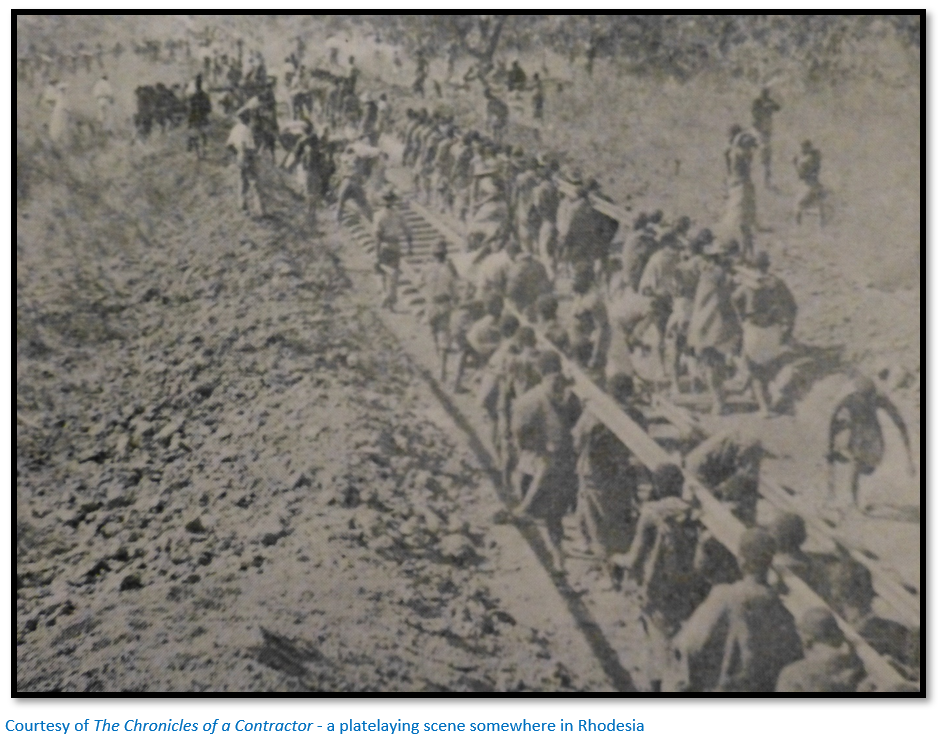

The railway was planned as a 2-foot light, narrow gauge line with rails weighing only 20 lbs a yard from Fontesvilla to Mandegos, later Vila Pery then Chimoio. George Pauling's estimated contract cost for the first section was £70,000 to be completed at the rate of one mile per day, but his initial estimate proved completely inadequate for the swampy and malarial conditions and the railway became infamous for the cost of human lives. Many white workers died and legend has it, one African for every sleeper. Although construction from Fontesvilla began in September 1892, Umtali was reached only in February 1898.

Below is George Pauling’s original estimate for the construction of 113 km (70 miles) of railway line and supply of locos and rolling stock from M’pandas to Mandegos (gauge 24 inches, sleepers 3 ft, 20 lb rails) dated 1 July 1891.

Cost per Mile | £ | s. | d. |

Line cost from England including sleepers | 495 | ||

Freight cost to Beira @ 50s per ton, 43.75 tons per mile | 109 | 7 | 6 |

Transhipping and freight to Pungwe River, 43.75 tons @40 s per ton | 87 | 10 | |

Earthworks 4 x 1 @ 1s per yard | 88 | ||

Platelaying @ £40 per mile | 40 | ||

Total cost per mile | 819 | 17 | 6 |

x 70 miles | 70 | ||

57,391 | 5 | 0 | |

1 Mile Sidings - 4 x 200 yards - 2 x 400 | 819 | 17 | 6 |

16 x single points and crossings @ £8 15s | 140 | ||

2 x Engine Sheds @ £100 each | 200 | ||

3% Duty on permanent way | 1,160 | ||

Rolling Stock | |||

20 x Covered Bogie wagons, 4 tons each @ £35 each | 700 | ||

30 x Open Bogie wagons, 4 tons each @ £25 each | 750 | ||

3 x Passenger cars @ £97 each | 292 | 10 | |

5 x Locos "Wasp Type" 6 inch cylinder to draw 80 ton loads | 2,600 | ||

Loco freight, packing & duty | 357 | ||

Wagons freight, packing & duty | 276 | ||

Distribution of material @ £20 per mile | 1,400 | ||

Culverts, etc | 2,000 | ||

Contingencies | 1,913 | 7 | 6 |

Total | £70,000 |

|

|

As a consolation prize Johnson was given the contract to transport all the railway material from Beira to Fontesvilla, but even this was a financial disaster for him as both the Agnes and the Kimberley required 150 cms (5 ft) of water under their keels. A shallow-draft paddle steamer “Crocodile” was built at Southampton and shipped in sections to Beira where it was re-assembled. But on its maiden voyage it struck a submerged log and sank onto a sand bar and was never recovered.

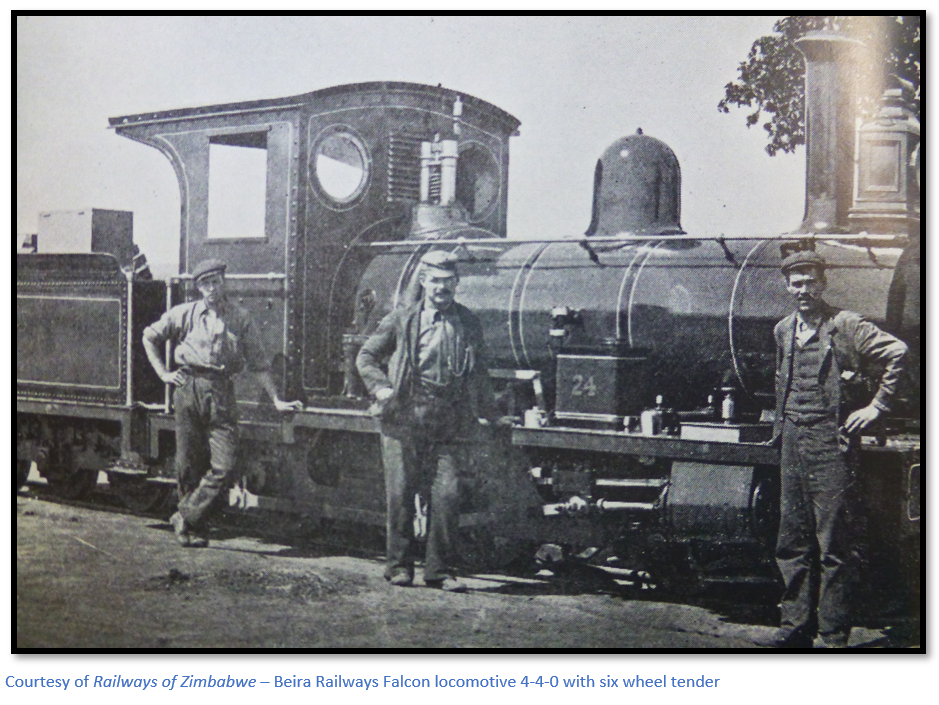

Some fifty European men were recruited at Salisbury and came down to the construction camp formed at Fontesvilla (Ponte do Pungwe) The 20 lb rail was supplied by Kerr, Stuart and Co of Stoke on Trent and five locomotives were ordered from the Falcon Engine and Car Works in Loughborough. They were typical contractors locomotives of 0-4-0 type with side tanks, straight lipped-top chimneys and open cabs with wood-fuel bunkers. Construction work began in September and by the end of November 23 km (14 miles) of earthworks were done with 4 km (2.5 miles) of rails had been laid out for platelaying to start.

1893 - The remaining line survey was begun by Harry Pauling, George’s cousin, who left before the rains begun and later died of fever at Beira and continued by Lawley and P. St. George Mansergh. The first 80 km of construction consisted mainly building of up the line above the level of the Pungwe River flats, but with the combined attacks of heat, tsetse fly and lack of knowledge of malaria and its treatment this section caused the maximum human casualties. It has been estimated that 60% (up to 400) of all the Europeans working on the line died of fever and on his arrival in May 1893, George Pauling found Lawley desperately ill with malaria so he put him on board a steamer with instructions to sail up and down the coast until he had recovered. The death rate among the African labour force has never been estimated and 500 Indian labourers nearly all died.

Tsetse fly caused equal destruction amongst the animals — 500 donkeys introduced in the belief that they could withstand "the fly" all died. The rainy season revealed that the first 16 km (10 miles) of line from Fontesvilla was submerged for about a month, and it was discovered that burials which were not deep enough either floated up or were disturbed by animals. On several occasions deaths occurred when the tugs were stranded on sandbanks; the deceased were buried immediately on the banks of the Pungwe River where the graves were marked by clumps of trees and served as excellent navigational aids — "Smith's Point" or "Jones's Crossing."

The first rainy season was very heavy with most of the area flooded; the Agnes grounded 11 kilometres from the main stream of the Pungwe; there she remained high and dry for three years until, with the help of a canal, there was another flood tide high enough to float her off.

The first section to Bamboo Creek, later Vila Machado, now Nhamatanda was extremely flat, teeming with wild game of all kinds and prone to flooding. Gondola was reached in October 1893, an outstanding achievement considering that the line through the Amatongas Forest rose from 198 metres (650 ft) to 638 metres (2,092 ft) in 40 km. At one section the steep terrain could only be overcome by constructing a series of zigzags ending in dead-end spurs; the train reversing direction at each halt.

1894 – A further £250,000 of debentures was issued to finance further construction and work begun in June 1894. Lawley employed over three thousand men on this section with the heaviest section requiring a 1.5 km (1 mile) embankment 13 metres (43 ft) high. Chimoio was reached In November 1894, the higher altitude bringing healthier conditions and the tsetse fly belt being left behind.

In September newspaper advertisements were being run by Pauling and Co that stated the mail train was running every Wednesday from Chimoio at 6:30am to connect with the ‘mail steamer’ at Fontesvilla the journey advertised as taking just over 9 hours. Passengers paid 6d. a mile first class and 3d. a mile third class; natives paid 1d. and corpses cost 1s. a mile! The boat-trip from Beira to Fontesvilla cost 25s. The 200 km from Fontesvilla to Chimoio cost £3 first class and the final coach run to Salisbury £9. Goods cost 12/6 to £1 per ton from Beira to Fontesvilla, including landing charges; then £6 per ton to Chimoio by rail and a further £6 per ton by wagon to Umtali – about £13 per ton in total.

At Chimoio progress came to a standstill for two years, partly because the initial contract had been completed and partly because of the combined difficulties of the rugged terrain ahead and escalating costs.

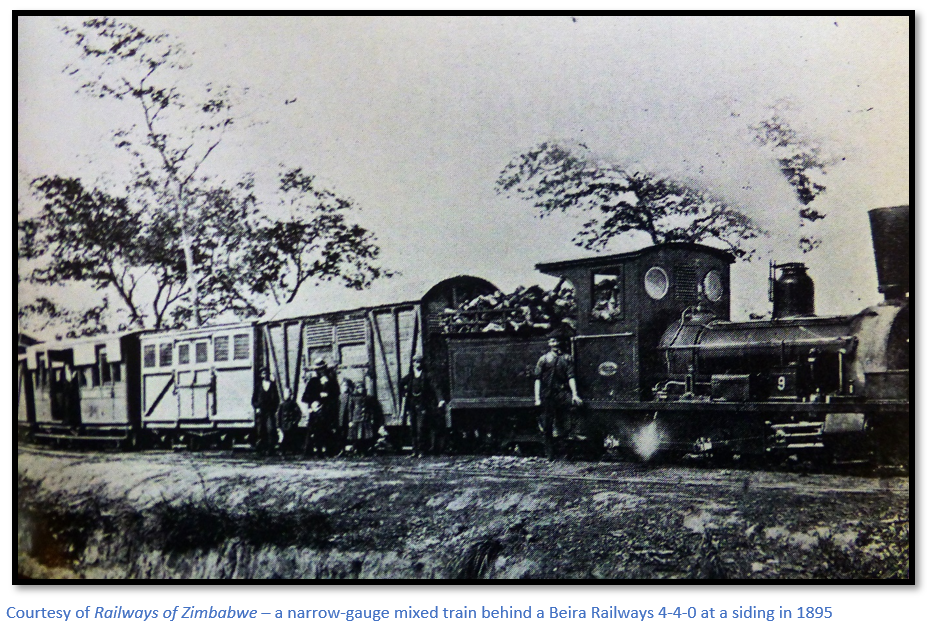

1895 – By January trains were soon running regularly two or three times a day to Chimoio leaving Fontesvilla at 6:30am and reaching Mandegos in the evening and Chimoio next morning. However arrangements were still crude, Kingsley Fairbridge travelled first class in a deck chair in an open wagon covered by a tarpaulin for shade. He wrote: “We saw great herds of game and men fired at them from the open trucks. A herd of zebra raced the train and we all shouted at them. Our train did not run off the rails, but most train did and then the passengers had to get out and push them back again.”

Another account by Edith Campbell to her mother quoted from Rhodesiana Publication is well described: “Landed at Beira and joined the tug Kimberley which steamed 4 miles up the Pungwe…and then anchored for the night. The Pungwe is a wide river with an awful smell about it. Next morning we went on but came bang on a sandbank where we stuck. There was a lighter fixed alongside of the tug and this went swing ahead breaking the ropes, then back again against the tug smashing the bulwarks. After a great deal of swearing on Captain Dickie’s part the lighter was collared again. Breakfast on the tug cost 3/- eggs, bacon, curry and bread with beer or cold water...After an enormous amount of swearing on Capt. Dickie’s part, I never heard anyone swear so much, but he informed me it was just habit and he never meant anything. Well we managed to get off the sandbank and went in to Fontesvilla. It is on the right bank and is almost a river in itself. A few houses about 3 ft above ground level because everything gets flooded in the rainy season…We landed at Fontesvilla by climbing over the tug’s side onto a lighter then scrambling on to the muddy bank…The next thing was to walk knee deep through wet grass and black mud to the hotel and such a hotel I never saw. The room I had was on the level of the ground, and to get to it I had to walk with black mud over my ankles for about 10 yards from the verandah; I nearly lost my shoes in that mud they stuck so tight in it…Well I inspected the room, then went to lunch, about a dozen men elegantly attired in their shirt sleeves. The lunch consisted of tinned beef curried, tinned beef stewed, minced, boiled and all sorts of mess and the pudding is quite beyond description.

Well we started, ten of us in the carriage. The Beira Railway is a queer-looking concern, very narrow and only a couple of carriages and about three engines. The carriages are long narrow things with hard seats on each side like garden seats and 10 inches wide. The first 25 miles of line known as the fly country is flat and grassy almost under water at this time of year, trees and enormous palms growing in clumps here and there and any quantity of game in herds close to the line. The train conveniently slackened off for hunters to shoot at each herd of game. Mr Jansen shot a hartebeest, cut it up and put it on the train. Then on to the 40 mile peg where we had to wait an hour for the Chimoio down train, so a fire was made, steaks were cooked and we picnicked under a big tree. After beer and canned pears for dessert we went on again through lovely forest…

At 60 mile peg at 2pm we came to a dead stop; the engine and first truck had run off the line and were lying gracefully on their sides against some rocks; fortunately, our carriage stood up…the engine diver jumped off in time and dragged the stoker with him. Then help was sent for up and down the line. Next morning a man came along on a trolley with a basket of food, four chickens, two loaves of bread, a piece of high meat, some gin and beer. Happily, I wouldn’t have any, as when the men were finished, they were requested to haul out 7/6 each for breakfast, 10/- for a bottle of gin and 5/- a bottle for beer…We had to wait for another engine…From 62 mile peg the line is comical, it is a zig-zag on the side of a hill and the train is pushed backwards and forwards to get to the top of the hill. I lived in a funk all along that line…At Chimoio a man had been wired to meet me, so I was taken to the hotel and slept til 10 next day. Then I sat on the verandah and interviewed everyone, some were rather whisky eyed too, but most polite.”

However, it also became clear that Fontesvilla was totally unsuitable as a port as the Pungwe River was constantly changing its course and the tugboats were endlessly grounding on sandbanks, additionally it was 80 km by water as compared to 60 km by land. The river journey was advertised as taking four hours; in fact, it was rarely completed in less than twenty hours.

The only solution was to add a further section of 56 kms (35 miles) of rail to the port of Beira. However the Beira Railway Company finances after the long and expensive construction period were almost exhausted…the 6% interest on the debentures unpaid.

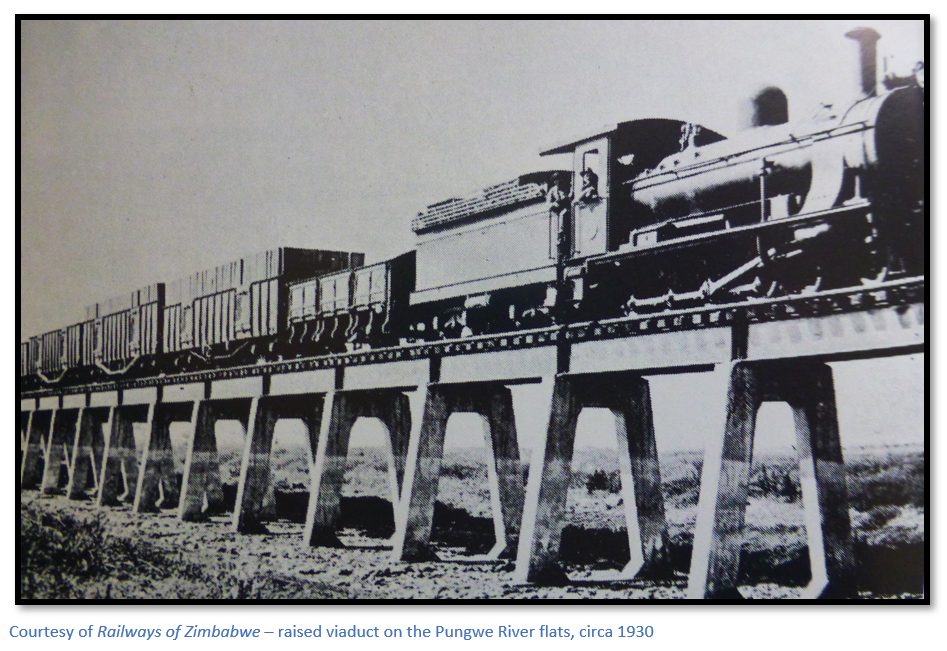

George Pauling used the banker and his long-time friend Baron Frédéric Émile d’Erlanger to promote the Fontesvilla – Beira section, a bridge over the Pungwe River and a wharf at Beira through a new Company, the Beira Junction Railway Company (BJRC) which enjoyed the same rights as the BRC; i.e. 3% transit duties and blocks of land along the railway line each five square kilometres in extent as long as they were not adjacent. Construction began from Fontesvilla with Lawley in charge. Crossing the Pungwe flats with the need for frequent small bridges and culverts slowed the work and the 56 kilometres (35 miles) took fifteen months.

The master of the Kimberley, Captain Dickie, used to provide food and liquor for the voyage and should the passengers be slow to finish his whisky the Kimberley would be stranded on a sandbank until Captain Dickie's supplies had been consumed before efforts were made to refloat her. Rhodes, who was made aware of this scam bought the entire stock of whisky and champagne for £25 after which the Kimberley made the passage in 12 hours breaking all records!

Charting a course along the Pungwe River was difficult with the sandbanks moving position after each high tide. At such times according to C. M. Hulley, Captain Dickie: "became ever more eloquent as each sandbank came into sight, doing all he could to avoid it, his vocabulary ranging from 'damn' to words of four syllables as he became ever more excited. He shook his fist, roared and yelled and then, remembering he was a gentleman, apologised profusely to the women on deck below him." When the Kimberley became stuck fast on a sandbank Dickie would use a mirror to attract local natives who, after considerable bargaining, would jump into the water making a considerable noise to frighten off crocodiles and, up to their armpits in water, would forcibly push the boat into deeper water, their reward being a blanket. If all these efforts locals failed, there was nothing to be done but to wait for the turn of the tide to lift her off the mud.

On arrival at Fontesvilla, the Kimberley halted at the mud bank and the passengers scrambled ashore with the help of natives and ladders. To some the name of 'Fontesvilla' suggested cooling streams, but the reality was very different. William Harvey Brown who wrote On the South African Frontier said: "Of all the deadly places I have ever visited, it was without doubt the worst. The yellow sickly appearance of the inhabitants suggested to our minds the idea of people who walk about to save funeral expenses. The houses were built on piles six feet above the swampy soil — the continuance of the railway to Beira doomed the future of the pestilential spot to nothing more than a sepulchre for the dead." Marshall Hole in Old Rhodesian Days agreed: "…a loathly little camp… with probably the highest death rate of any place in the world." There were two cemeteries, both nearly full and because the water level was only a few feet below ground level heavy weights had to be placed in the coffins to keep them down while the graves were covered with soil.

Travellers were left with two dominant memories of Fontesvilla, one being the Railway Hotel. In the dining room only buck steaks were served and they were tough and inedible; the bedroom furniture comprised a bed slightly over a metre in length with a wire foundation, no mattress, one coarse sheet and one small blanket. The owner was: “a pale, yellow, fever-stricken, listless spectre, perpetually drunk into the bargain.”. The second memory were the rats. Dan Judson who was woken by the rats gnawing his candle was so disturbed he dressed and walked all night.

Once passengers had unloaded their baggage from the Kimberley, the next task was to find a seat on the train. In the early years this was normally a garden seat, wide enough for three burly men to sit abreast, in an open goods truck. Some were fortunate enough to have a covered coach but in the case of the Hulley family in 1894 this was derailed only 30 km out of Fontesvilla and the journey continued on an open truck loaded with timber; worse, it poured with rain for much of the journey.

Livestock was conveyed in special trucks fitted with wire gauze as protection from tsetse fly, whilst African travellers perched on top of the loaded goods trucks where they spent their time avoiding the very real danger of being swept off by overhanging branches. Once the train was in motion and depending on the strength and direction of the wind, sparks from the wood-burning locomotive constantly threatened and arms and legs had to be continually slapped to prevent the passengers clothes from being set alight.

Peter Shinn entered the country via the narrow gauge and “joined the train to Chimoio, hauled by a wood-burning engine which stopped frequently to take on fuel. There were two passenger coaches exactly the same in appearance as the old tramcars in England with a long seat down each side with one’s back to the drop windows, beautifully arranged so that the red hot sparks from the engine could fly in and set your clothes alight. Everyone now and then someone would smell clothes burning and there would be a general post to find who was alight.”

Those who had their backs to the engine and could keep the cinders out of their eyes noticed that many of the telegraph poles leaned at drunken angles with broken gin bottles used as insulators — this section was within the tsetse fly belt and progress had been made as hastily as possible. Every two or three hours the engine would stop to allow passengers and crew to collect bundles of firewood left by African woodcutters at recognised sidings.

From Fontesvilla across the coastal plain to Bamboo Creek, then Nova Fontesvilla, later Vila Machado, now Nhamatanda and famous because elephants had been seen using the water tower as a spray bath!) the line was practically straight; when it was flooded an African was sent to splash along in front testing the line with his toes. When it was dry the train could reach 20 kph downhill but after Bamboo Creek, on the steeper gradients, the passengers would often walk alongside the train giving it a playful push to help it on its way. At one point the gradient was so steep that a gang of Africans was kept pushing from behind.

Passengers did not complain much; these discomforts were minor when compared to travel by ox-wagon or walking. Besides, the passengers met the most unusual people: an heir to an earldom who ran a butcher's business; a baronet who opened a small hotel; 'Long' Paley, grandson of a Bishop; 'Daisy' Newbolt, nephew of Canon Newbolt; little Jean Menaut - 'Johnnie the Frenchman' — short and broad with a long black beard who ran a shack at Bamboo Creek called by courtesy an hotel. Varian wrote: "the eternal item of his cuisine was buffalo meat, no matter what other name it assumed" and there was Larsen the Swede, one of the earliest guards on the railway who later became a notorious ivory poacher and died in Angola.

The only noteworthy building was the Railway Hospital at the 77 mile spruit. Chimoio, the railhead in 1895 – 6 for two years had just a small collection of mud huts, one or two galvanised wood and iron stores and 'Lawson's Hotel', the latter a series of huts with calico-covered windows and a door made of old packing cases on which was printed 'Keep the Contents Cool', secured by a nail and string. The furniture - two packing cases, japanned washstand ware, two wooden stretchers and a piece of sacking on the floor was considered relatively luxurious.

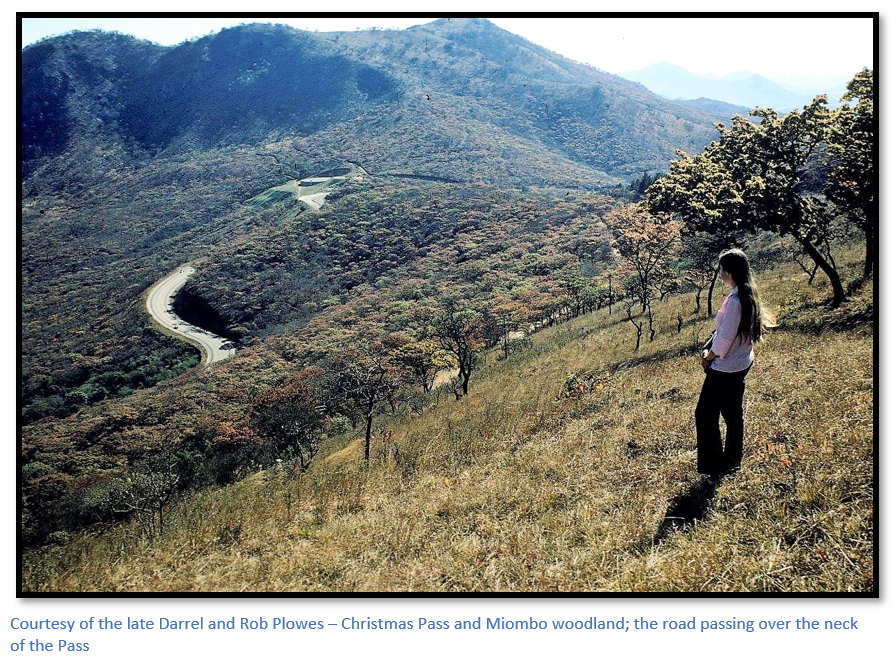

Mr. Symington's mule-drawn carts could cover the final 120 km from Chimoio to Umtali in 22 hours but many passengers preferred to walk rather than wait for the next cart which could be a week in coming. Travel in the cart pulled by fourteen mules was cramped, hot, dusty and bumpy, there was a strong possibility of the cart overturning, of vital parts breaking or of being stuck in a river or a donga, all of which meant lengthy delays. The first stop for lunch was at Vendusi where there was a store run by a golden-haired Frenchman whose native servant spoke English, French and Portuguese. The night stop was at Hawe’s store at the Revue River which offered mud huts, blankets and a warm fire. [Dan and Maynie Judson’s account of this journey is in Mashonaland Central / Mary Blackwood Lewis’ letters on her journey to Mashonaland from Beira is in Manicaland. Both articles are on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] An early start meant lunch at Massi Kessi, the home of the Portuguese Commandant and the customs officials as well as the site of a hospital. Supper could be taken at one of four stores — Botley's, Fisher's (five kilometres short of the border) Brown's or Leslie's, the latter near the present site of Umtali. Next morning there was a 4 am start and walk up Christmas Pass and over the Mutarandanda Range behind the cart. At the top of the rise everyone climbed into the cart which rushed into Old Umtali where the mail was always eagerly anticipated.

Late in 1895 Mansergh, the surveyor, reported that it was impractical to take the rail line over Christmas Pass at the lowest point of the Mutarandanda Range and recommended the route along the valley of the Sakubva River and over the Nyamashiri Range to the Odzi River, the next big obstacle.

1896 – Rhodes was in the country having recently resigned as Prime Minister of the Cape following the Jameson Raid and on 26 March 1896 held a meeting with the residents of Old Umtali. The choice was clear: either the town moved to the planned site of the railway or it remained where it was and became an isolated backwater. The meeting agreed that the town would have to move and the owners of stands in Old Umtali would be given corresponding position in the new town with valuations of all buildings in the old town being calculated for which the BSAC would pay the owners. In addition, the BSAC would build suitable government buildings and a hospital and provide money for a water supply at the new site.

A selection committee consisting of Sir Charles Metcalfe, Mansergh, Pickett and Suter choose the final site at the farms Sable Valley, Birkley and Mountain View and paid out £5,000 to the owners. Landowners in Old Umtali applied to the Surveyor-General, J. M. Orpen, to allocate new stands on the new site.

In January 1896 Arthur Lawley was arrested and imprisoned in Pretoria from January to May for his part in the Jameson Raid and returned during the Mashona Rebellion or First Chimurenga. Many of the workers deserted and returned to their kraals, but the railway line remained open and operational throughout.

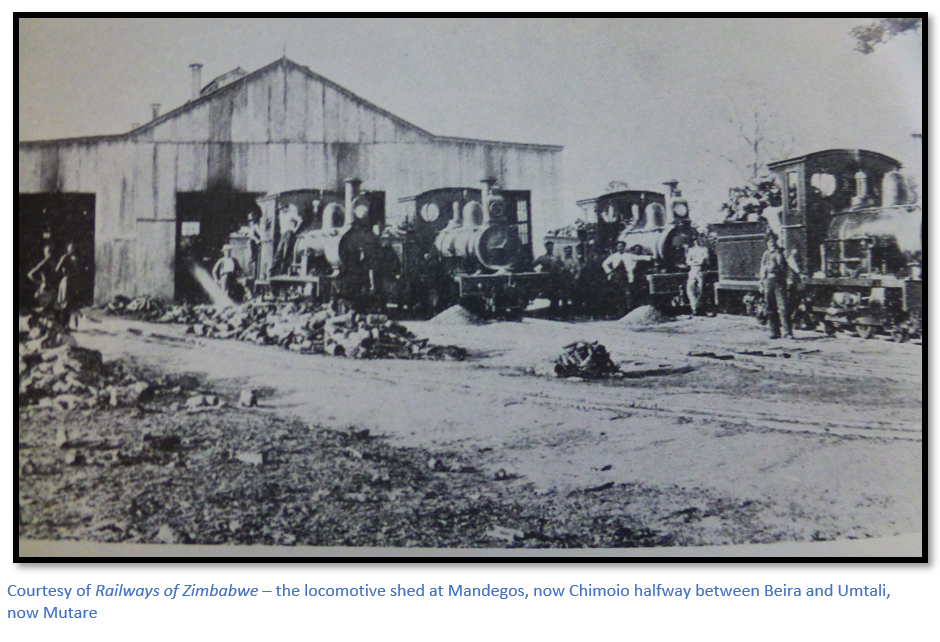

A third issue of Beira Railway Company Debentures for £600,000 was issued in 1896 to enable Pauling and Co to begin construction in May of the remaining 109 km (68 miles) of railway line between Chimoio and Umtali. The company now owned 20 locomotives and 140 wagons and Lawley decided that Mandegos, then Vila Pery, now Chimoio was the most suitable spot for a locomotive depot being at an altitude of 700 metres (2,300 ft) and roughly halfway from Beira to Umtali. Once the narrow gauge had been replaced by the standard gauge in 1900 the engine shed became redundant and was dismantled and removed to Victoria Falls where it became the dining-hall of the Victoria Falls hotel.

With the outbreak of the Mashona Rebellion or First Chimurenga, Lt.-Col. Alderson was sent from Cape Town in the Arab and arrived off Beira in early July 1896 with a force of 380 men and 284 horses of the newly-designated Mashonaland Field Force. The first detachment set off on barges towed by the tug Kimberley skippered by the redoubtable Capt. Dickie who Edith Campbell encountered the previous year. Like others they were struck by his knowledge of the Pungwe river and by his language; Alderson states he never heard a man with a better flow of the most expressive nautical oaths after he ran aground and stuck fast some 4 km from Fontesvilla.

The Kimberley could not get off with the morning tide and Alderson and two of his officers left by dinghy for Fontesvilla where they had breakfast at the shanty called the “Railway Hotel.” They found sufficient space for the men and horses, but judged Fontesvilla about the most feverish looking spot that could be imagined and judging by the two nearly full cemeteries it was as bad as it looked.

They left in a special train consisting of a locomotive and one carriage through flat marshy country teaming with zebra, buffalo and innumerable antelope. At 80 mile station, near which was the railway hospital, they arranged with the owner of the “so-called hotel” for the troops to be supplied with coffee, bread and cheese. At Chimoio there was plenty of space for men and horses and the BSAC representative Fotheringham to erect tents made of wagon sails.

On their way back at the 62 mile peg they met the first of the upcoming troop trains, where they were informed that the second train had derailed so they went on and at the 56 mile peg as they rounded a sharp curve heard a whistle and saw the train only a hundred yards away. Both drivers shut off steam and applied brakes and everyone jumped off onto the embankment as both locomotives collided and entangling their cow catchers , but without incurring much damage. Once untangled the upcoming train backed up and they came to the scene of the derailment…the second train’s carriages had all come off at an embankment killing two horses, others had to be shot and the rest had run off, although none of the troops were injured. When the line was cleared both trains backed up to the 62 mile peg.

As a result Alderson already arrived back at Fontesvilla at 2am next morning and says he was oblivious to the rats who steeple-chased over his bed. The engineers meanwhile had lashed two small lighters together as a platform for the horses and built a landing stage and ramp up the bank for unloading the horses. Mr Moore of the Beira Railway Junction Company was asked to reduce the speed of the trains which meant sixty horses and men would leave Fontesvilla every third day.

Gradually the men and horses were disembarked from the Arab over six days as Captain Haynes continued to improve facilities at Fontesvilla with watering troughs for the horses, washing places and latrines for the men and was repairing the wagons broken in the derailment of the 8 July. Captain Haynes was later killed at the attack on Makoni’s kraal [see the article Fort Haynes and the attack on Chief Chingaira Makoni’s kraal under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

The men and horses and stores then marched for Umtali, but wagons were difficult to obtain, the reason being that traders wanted to send goods, especially liquor, up to Salisbury behind the Mashonaland Field Force and sell them at famine prices. Alderson commandeered the waggons and had the liquor replaced with food supplies. The ride to Old Umtali 116 km (72 miles) away over Christmas Pass took two full days and they overtook most of their force enroute.

In October 1896 the Beira Railway Junction Company eventually linked Fontesvilla to Beira and this part of the trip became considerably quicker and more efficient, but until the bridge over the Pungwe was complete train passengers were carried through the mud to and from the ferry boat by local natives.

1897 – after petitions had been sent to Rhodes and Queen Victoria construction re-commenced and the railway line reached Massi Kessi or Macequece, now Villa de Manica.

Under the supervision of George Pauling who was Commissioner of Public Works in Umtali, the whole town at Old Umtali was dismantled and building materials and property carried over Christmas Pass and rebuilt on the new site; for a while there were two towns of Umtali with the population of ninety Europeans equally divided between the two. Most homes were pole and dhaka huts with thatched roofs and construction was hindered by a shortage of labour after the Mashona Uprising or First Chimurenga.

The B.S.A. Company paid out over £300 000 in compensation and this money as well as the approach of the railway contributed to the rapid development of the new Umtali.

On 11 August 1897 the last meeting of the Sanitary Board in Old Umtali was held. Negotiations between the BSAC and the Methodist Church had been taking place and on 12 December 1897 Bishop Hartzell conducted the first Methodist service in a general dealer’s store prior to the handing over of the remaining buildings and 1,300 acres of land for the establishment of a church and school. Today a hospital, a large and respected Bishop Hartzell Primary and Senior School, Fairfield Children’s Home and agricultural program with Africa University nearby demonstrate the success and progress made subsequently by the Methodist Church. [See the article Old Umtali – the second site under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

By late 1897 the old ‘Tramcar’ type passenger carriages had been downgraded for third-class passengers and the new carriages had seating for four passengers in each section and no longer had to contend with red-hot sparks from the wood-burning engines setting their clothes on fire!

1898 - The first train reached Umtali on 4 February, having left Beira the day before. Although narrow gauge (2 ft) and limited to 50 ton loads, the railway did mean regularly scheduled transport. The last 32 km (20 miles) from Macequece, now Manica into Umtali rose 366 metres (1,200 ft) and required numerous curves and culverts. A railway celebrations week was held in April with a programme of banquets, dances, cricket matches, rifle meets, Caledonian sports and a fancy dress ball and soon after all the railway workshops and buildings were soon transferred from Fontesvilla to Umtali.

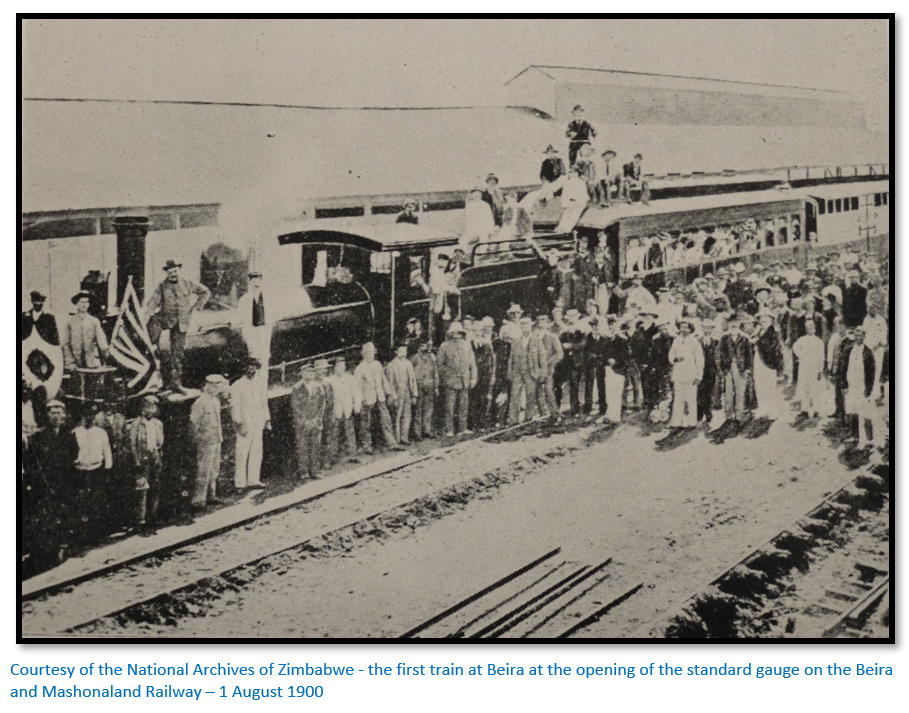

1899 - On 22 May the standard gauge line (3 ft. 6 in.) to Salisbury was opened but inevitably confusion and delay arose from the difference in gauges when goods began to flow from the coast to Salisbury. The original two foot gauge had been pushed through at the lowest possible cost and thus followed the line of least resistance; the earthworks were as light as possible and bridges were all temporary structures.

A contract had been signed by Rhodes in March for the widening of the gauge for the full 357 km (222 miles) and realignment of the heaviest gradients; £900,000 in 5% Debentures were issued and guaranteed by the BSAC.

The line between Beira and Umtali was therefore re-laid to the 3 ft. 6 in. gauge at a cost of about £800,000 for the 328 km (204 miles) the conversion being completed on 1 August 1900. About 1,000 Europeans and 6,000 natives were employed and the new alignment shortened the total length by about 19 km (12 miles) without taking the track away from the settlements that had sprung up along the route.

To complicate matters, the Anglo-Boer War broke out whilst the conversion was being carried out.

Stops were frequent for fuel and water as the tenders were small and local Africans would be present to load the cut timber quickly while overhead tanks replenished the locomotives water supply. Stations were small corrugated iron buildings with a covered verandah and were connected to each other by a two-wire telegraph line on iron poles. These the elephants used as scratching posts with negative effects on communications.

By the end of 1899 six trains a day were leaving for Bamboo Creek where the loads were split in half for the heavily-graded climb to Umtali.

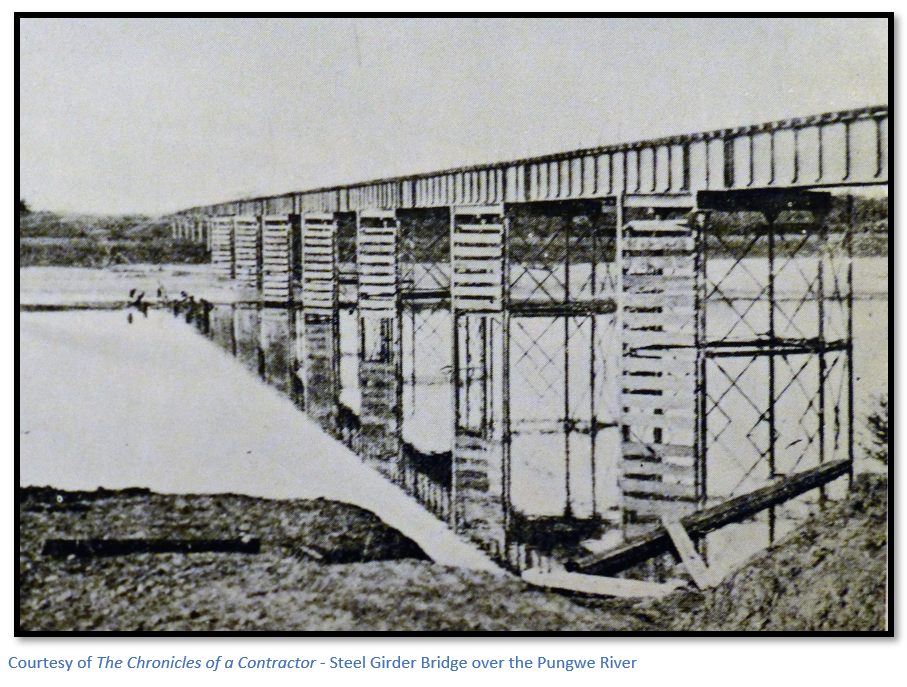

1900 – In addition to the track widening it was necessary to replace the temporary wooden bridges which were not wide enough or strong enough for the standard gauge with steel girder structures. At Fontesvilla a new steel girder bridge was built by Wm Arrol and Co to replace the old bridge.

Lawley’s role in the Anglo-Boer War is well told in Varian’s account below. In an amazing effort between March and July 1900 over 5,000 troops, 14,000 tons of military stores, guns and ammunition and 10,000 horses, mules and cattle were moved between Beira and Umtali and everything needed to be transhipped from the narrow 2 ft gauge to the standard 3 ft 6 inch gauge as well as the normal goods traffic to Salisbury and construction materials for widening the line.

The final rails of the 3 ft. 6 in. gauge were laid near Mile 42 on 1 August 1900 and soon after the Beira-Umtali-Salisbury sections of the Beira Railway Co. and the Mashonaland Railway Co. combined under one management known as the Beira and Mashonaland Railway (BMR)

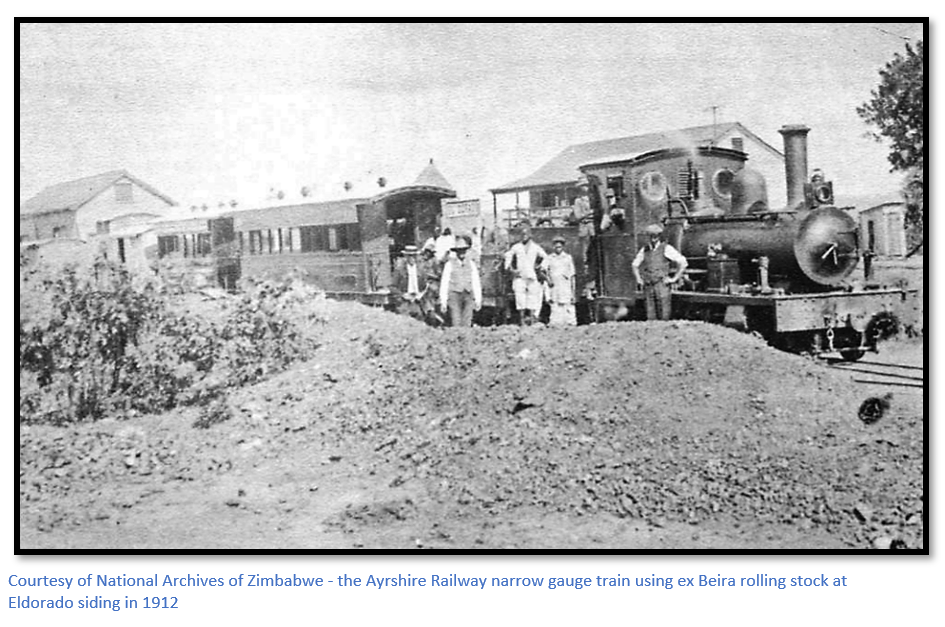

Most of the 2 ft gauge rolling stock was stored in sidings close to Bamboo Creek Station and slowly sold off. Thirteen of the Falcon 4-4-0 locomotives were sold to the South African Railways in 1915 for use in the occupation of South West Africa, now Namibia and others used in South Africa became the NG6 Class but were always known as ‘Lawleys’ during service. Some were used on the Salisbury – Ayrshire line and others on the Planet Arcturus Railway line {see the article under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] The Umtali tramway which operated from July 1901 and was removed July 1920 presumably used a short amount of the narrow gauge track which had been replaced by standard gauge track on the Beira railway in 1899 – 1900 but the passenger tramcars were especially imported from the USA.

One of the 4-4-0 Lawleys joined the Hans Sauer on the Selukwe Peak Light Railway in 1920 and this narrow gauge railway operated for over fifty years. Three Lawleys were employed on the Premier Portland Cement Company’s Railway bringing limestone from their quarry on Claremont Estates to Cement. Two of their locomotives were sold in 1931 to the Suzman Brothers Logging line which ran from the Zambesi River near Victoria Falls. The Cam and Motor Mine’s light railway ran from their plant at Eiffel Flats near Gatooma, now Kadoma bringing in firewood for the roasting plant and three ex-Beira Lawley’s were purchased from the Ayrshire line for this purpose. Two of their locomotives were eventually sold on to the Igusi Sawmills Light Railway.

Below is the sad and rather depressing account written by Sharrad Gilbert: Rhodesia and after; being the story of the 17th and 18th Battalions of Imperial Yeomanry in South Africa of his experiences at Thirty-two Mile Creek and then at Bamboo Creek.

In 9 May 1900 Gilbert and his fellow soldiers arrived in the Galeha off Beira; the harbour had never held such an assemblage of ships…the Maori, the Waimate, the Monouai and the Cymric; all packed with khaki figures, Queenslanders, Victorians, New Zealand Rough Riders and the 17th and 18th Battalions of the Imperial Yeomanry. Next day they waited patiently for nearly six hours before the paddle steamer Trevor came alongside and they set foot on African soil for the first time.

Shortly after they were on a troop train on the narrow gauge Beira – Salisbury railway. Each carriage was 16 ft by 5 ft on six wheels and overhung the 2 ft gauge railway line with overhead a flat corrugated iron roof and timber boards at the ends but open at the sides. Each filled with sixteen men in marching gear, thirty-two kit bags and three days rations for each man. The string of carriages were pulled by two comical little locomotives made at the Falcon Works, Loughborough. Compressing sixteen pairs of legs into this space was quite impossible, so soon each side of the train had dozens of pairs of dangling legs clad in putties, boots and spurs.

The engines all burnt wood fuel so every few miles there was a plentiful heap of logs heaped up by the side of the line by a group of native huts. At 32 mile peg, christened Thirty-two Mile Creek, were a couple of iron buildings and a neat enclosed garden with large banana trees and a large water tank by the side of the line. The men unloaded their baggage and stores and scrambled up the bank to follow their officers for half-a-mile until they come across lines of tents put up by the squadrons who preceded them. They pitched their tents and had a meal of corned beef and ship biscuit with hot coffee. Before sleep, each man has a quinine tablet. One of the few remaining buildings, for this was once a native kraal, served as a guard house with one prisoner who woke up in the night to find: “three large light grey rats, one on his face, the other two sitting on his chest and contentedly trying to make a late supper off the buttons of his greatcoat.”

Because Portuguese East Africa was notorious for fever the men were given quinine daily. They were compelled to wear a sombrero during the day and a tam o’ shanter after sundown. Handkerchiefs were worn around the neck and they were forbidden to sit on grass after the sun went down. At every hour of the day and night long trains, drawn or pushed by two or three engines and laden with men, horses and stores passed their camp on their way northwards. Often stores arrived in the middle of the night and they shouldered the heavy boxes and stumbled with them over the uneven ground in the darkness back to camp. Food was made up of bully beef and hard ship biscuit for breakfast, dinner and tea.

On 19 May they were told of the Relief of Mafeking a few days before and all cheered and threw their hats in the air for Baden-Powell and his gallant men who had resisted Boer efforts for seven months. A few days later they were visited by Cecil Rhodes…Gilbert thought his face seemed lined with care.

On 20 May a company of New Zealanders and 100 horses stopped for a few minutes. They had food, but no water, so Gilbert and his companions filled their water bottles at the creek. The train had an engine at each end, but the driver of the rear engine was drunk and in evil humour. A few miles down the line he unhitched his engine and the train was unable to move on for some hours.

On 22 May the sick were brought in stretchers from the camp and waited over three hours for a train. Then the train collided with some trucks parked on a siding and some of the carriages were derailed. The whole camp was marched to the siding in the dark and took two hours to lift the carriages back onto the rails before the train left with its sick passengers.

On 23 May Gilbert and the Imperial Yeomanry were due to leave at 11:30am. It was very hot and there was no shade as all their tents were packed. The train arrived at 8pm and they left after their stay of 12 days in a grain wagon – a box with an iron roof and large door which had to be kept open all night to prevent them suffocating. They sat on their kitbags, no light, no food and no room to stretch legs. Someone started a singsong, but it died a natural death. At last at 12:30 the train stopped and they were told they were at Bamboo Creek.

They arrived after a heavy thunderstorm and next morning saw their new camp. A large stretch of black-looking soil covered with rows of dirty-looking tents, bare hard trodden earth in the higher parts, soft and sticky earth in the hollows. The railway line in front was reached by crossing dykes and pits of smelling stagnant water crossed by planks; at the back was coarse yellow shoulder-high grass except where it was burnt off. The right side had a vast horse paddock, the right was waste ground and the men had barely been in camp a day before they began to fall sick.

Each day those on parade grew smaller and words malarial fever which had just been a name, now became a reality. The two or three small hospital tents soon grew full and a fatigue party was kept busy constantly throwing water on their canvas sides to keep the interiors cool. The doctors were the hardest worked men in the camp as their duties continued day and night.

Soon the hospital tents were full and the sick men stayed in their own tents…the fit stepping over their blanketed bodies. The fever removed any desire for food and their friends patiently helped them eat small quantities. Fever often revealed itself when the men were on parade under the hot sun when the sick fainted. In one Yeomanry squadron only two out of the section of twenty-eight men remained fit for duty; each day in turn one served as tent orderly and the other fell in on parade – their sole section representative. The camp was becoming a vast hospital and as day followed day no instructions came to move.

Fever was followed by acute diarrhoea and then dysentery. At the end of the camp was the Bamboo Creek cemetery. When the Imperial Yeomanry arrived it held four graves marked by white wooden crosses with black paint inscriptions - by the time they left three more graves had been added. Prior to their arrival numbers of horses had died of blue tongue; the carcasses were not buried, just dragged into the surrounding grass away from the camp where they were fed on by the vultures.

Army food was monotonous and unimaginative consisting of bully beef and hard ship biscuit every day of the week accompanied by tea or coffee; when they could be purchased the men supplemented their diet with tins of condensed milk and jam.

Bamboo Creek at the time was the terminus for the narrow gauge; to the west the 3 ft 6 inch standard gauge continued toward Umtali. The station and telegraph offices consisted of iron buildings with veranda’s dominated by groves of banana trees. Everywhere hundreds of natives were busy unloading stores from the narrow gauge and onto the carriages of the standard gauge. The Bamboo Creek Hotel was within their bounds, but a sentry prevented the troops visiting the Portuguese settlement.

The Hotel’s large matchwood boarded bar-room had a long counter, backed by the usual bar-room shelves and a glittering array of coloured bottles and flasks. The clink of glasses mixed with the hum of scores of conversations, a shifting population of slouch-hatted, shirt-sleeved, booted and spurred and picturesquely dressed men with brown faces and sun-scorched arms. At the far end the click of billiard balls; everything seen through the smoke of bad shilling cigars and black cake tobacco. Behind the bar the sallow faces and broken English of the attendants and every few seconds the crash of a broken bottle as it was flung through the open window at the back of the bar to join the dozens that have gone before. Many enjoyed their first square meal since they left home of antelope meat or boar’s head in the dining room.

The orders to move came suddenly and by Sunday midday their kit-bags and bedding were packed and they waited in blue deck uniforms to save the khaki from sparks. The hours rolled by and the men unpacked their blankets and lay down to sleep. The train arrived next day at midday. Eight horse boxes – seven of them filled with horses for the Rhodesian Artillery and one open wagon. The sick were put in the empty horse box, the rest packed into the open wagon but there was room only for “A” squadron and the remaining three squadrons had to wait. So on 28 May 1900 Sharrad Gilbert along with forty-two other soldiers, many sick with fever and dysentery left the fever pit of Bamboo Creek on a journey to Marandellas which would take two days and a night.

Many weeks after he says he came across the following written shakily in pencil upon the walls of a Rhodesian Hospital: “Bamboo Creek, the white man’s grave.” He continues: “It was only the work of an idle moment, scrawled by some unfortunate when the fever had left him strength and the power to think. But for the truth of it let the little row of graves in the cemetery at Bamboo Creek bear witness; for the bitter proof of it go to the Umtali graveyard to the last resting place of the score of British and Colonial soldiers who lie there. To its fever-laden flats we owe the teeming hospitals of Umtali and Marandellas. Of Umtali where ninety men were crowded into a building intended to hold fifty; of Marandellas where in addition to the iron hospital of nearly forty beds, fifty large huts of mud and thatch had to be built to cope with the incoming sick. Many a man who saw his name among the pitiful list of those invalided home owes to Bamboo Creek his shattered health and the wreck of bright hopes with which he left his country and his home.”

[An article on the Anglo Boer War graves at Paradise Plot, Marondera can be found under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Henry Francis Varian wrote Some African Milestones

Varian spent sixty years on railway construction projects in Mocambique, Rhodesia (where he was assistant engineer on the Victoria Falls Bridge, Angola on the Benguela Railway, and in East Africa.

Varian’s father worked in the Woods and Forest Department in Ceylon and was locally well-known as an elephant hunter but suffered an early death at 34 years old leaving a wife and young family. Through lack of funds Varian was forced to give up writing entrance exams to the Ceylon Civil Service but was offered a position with the Burma Teak Forest Company. At the time he was running with a pack of Bassett hounds and made friends with Cyril Hoste, brother of “Skipper” and Derick Hoste [Derick’s death of blackwater fever at Hartley Hills is told under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] and Vivian and James Archer-Burton. James had been shot through the head at point-blank range during the Mazoe Patrol’s escape from the Alice Mine [this article is under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] Once recovered from this terrible wound which took off the lobe of his left ear, passed through the roof of his mouth and emerged below the right eye, James intended returning to then Rhodesia and opening a store at the Hunyane (now Manyama) River drift, then known as “Norton’s Poort.”

Varian was trudging back with the hounds one day, as acting whip with Cyril Hoste, who suddenly asked why he did not join them? Cyril thought that Mashonaland, still recovering from the rinderpest and Mashona Uprising or First Chimurenga, was ripe for someone prepared to work hard and take what came. Varian’s friends did a whip-round and almost before he realised, he had joined them on the train journey across Europe and embarked from Naples on the S.S. Koenig for the East African coast.

They arrived at Beira, Portuguese East Africa on Queen Victoria’s Birthday, 24 May 1898. The town was the headquarters for the construction of the 2-foot gauge Beira Railway and consisted of a long street lined with wood and iron buildings along which trolleys were propelled by natives on a 1 foot 6 inch Decauville track. As all the trolleys were privately owned and none were for hire, visitors had to trudge through the sand. The yellow fever-stricken look of the town’s inhabitants reinforced all the tales they heard of Beira’s evil reputation for ill-health.

After several days they obtained a covered wagon and with their baggage and themselves stowed inside spent the next two days travelling to new Umtali. The 3 foot 6 inch gauge line to Salisbury was being extended but was not yet complete and transport was still dependent on ox-wagon and coach. Transport rates were 10/- per 100 lbs, having recently halved; in 1896 with the rinderpest they were £5 per 100 lbs. These high wagon rates added to the £11 per ton rate over the Beira Railways made imported goods expensive. A tin of bully beef cost 2/6d, a case of milk 45/-, a case of whisky 42/- and beer was 7/- a bottle.

Their convoy consisted of five wagons, four with general cargo and one of timber deals and they left Umtali for the first outspan at the foot of Christmas Pass. The first sunset was memorable; Varian had arrived at the best time of year when the rains were over and before the bush fires concealed the landscape with haze and smoke. The two obstacles on the journey to Salisbury were Christmas Pass and the Odzi River drift with the first considered the worst. In 1898 the only route over the Pass was straight, steep and heavily scoured by the rains. The four general cargo wagons were all double spanned; the timber wagon was triple spanned, but when it stuck in a pot-hole and the timber began to slide off another span was added making a total of seventy-two oxen; the journey of 5 kms taking five hours.

Varian says the journey was his apprenticeship to life in the country and the laws of the veld much as Percy Fitzpatrick describes in Jock of the Bushveld. Trekking was adventuresome although the actual travelling was very monotonous as the wagons only moved at three kilometres an hour and the only way to avoid the thick clouds of dust was to travel on foot either well ahead or a long way behind. On the way to Salisbury there was plenty of evidence of the rinderpest with skeletons of oxen lying on the veld and abandoned wagons.

A varied year in early Salisbury began with little prospects for civil engineering; he obtained a job with a newly arrived architect but left after being paid £7 10/- for a month’s work. Then he found part-time work sketching out prospector’s claims and another as agent for mining companies and finally a role as acting Deputy Sheriff.

Widening the 2-foot gauge to the standard gauge of 3 foot 6 inches

In June 1899 Varian went down to Beira where the widening of the 2-foot gauge line to the standard gauge of 3 foot 6 inches between Beira and Umtali was due to begin. Friends he knew dined with Alfred L. Lawley, head of Messrs George Pauling & Co the contractors, and next day he received an appointment letter scribbled on the flap of an Egyptian cigarette box: “Varian all right, starts tomorrow morning.” Lawley himself had been appointed as: “he had no fear of fever, and very little of anything else.”

The original line had been built at the lowest possible cost and followed the line of least possible resistance with earthworks as light as possible and only temporary bridges and culverts. James Frame was the engineer in charge; the day Varian arrived as his assistant he was told that Frame had already killed several underlings; he was eagerly awaiting a new victim as his most recent underling was in hospital! Frame’s only idea on life was work – food and recreation just did not matter. They shared a tent; food consisted of rice and sardines and the occasional antelope that Varian managed to shoot.

Work followed the same routine. At dawn they made for the end of the previous day’s work, sometimes 5 – 6 kms away and not a word was spoken unless about work. They dressed lightly and no attempt was made to stay dry. Varian went down with malaria which was treated with pure quinine. Varian says that after several attacks when he feared he would die, he now felt so terrible he began to fear he might not!

The line widening started at Umtali and they worked in sections getting as much traffic as possible forward to the line already re-laid to 3 foot 6 inches, then closing the following section where the new materials were laid out alongside, ready for use as soon as the 2-foot gauge was torn up. When Varian joined the wider gauge had been laid as far as Bamboo Creek, 97 km (60 miles) from Beira and the Locomotives and rolling stock designed for 3 foot 6 inches had great difficulty supplying sufficient construction materials.

The outbreak of the Anglo-Boer War and siege of Mafeking in October 1899 cut all traffic from the south and diverted all traffic through Beira. All goods had to be transhipped from the narrow to the standard gauge at the junction which, when the first contingent of Australian, New Zealand and Canadian troops arrived, was at Bamboo Creek. Some 7,000 troops and several thousand horses from Hungary and the Argentine, and mules from Texas and the Argentine together with all the associated stores, equipment and forage arrived at Beira at a time when there was neither a camp for the men nor fencing for the animals, with the rains still in progress, malaria and horse-sickness were rampant and flies were everywhere. There were delays as the lighters were off-loaded and more delays at the junction at Bamboo Creek. There was enough rolling stock for the 2-foot gauge, but only three large engines and one saddle tank shunting engine, the ‘Jack Tar' [See the article on the Railway Museum at Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com)

The delays as they waited for transport resulted in soldiers dying from malaria and dysentery at 23 Mile Creek camp, Umtali now Mutare and Marandellas, now Marondera [See the article on the Anglo-Boer War at Paradise Plot Cemetery, Marondera under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] Men, guns, horses and ammunition and stores had to be manhandled from the 2-foot gauge rolling stock to the 3 foot 6 inch gauge for their onward journey.

About the same time Rhodes arrived with Sir Charles Metcalf, the chief railway consulting engineer, and a lot of pedigree cattle and pigs for his farm at Inyanga, now Nyanga. During their transhipment, a pedigree pig with a litter of eight piglets strayed close to the Australian camp – the sow returned without her litter and travelled up alone!

All this time, troops, animals and stores and ammunition were being moved down the line…to complete the change from the 2 ft gauge to 3 ft 6 inch standard gauge the remaining 97 kilometres (60 miles) were divided into sections of 20 miles each; the first being Beira station yard and twenty miles, the second from mile 20 to 40 including the Fontesvilla bridge over Pungwe River at mile 35 and the third section from mile 40 to Bamboo Creek. Varian was assistant at the second section.

The last 2-foot gauge train left Beira on Thursday and arrived at Fontesvilla at 11:30 am. The light track was torn up before the train left the station some two hundred metres north of the Pungwe River by large teams of platelayers and lifted clear of the standard gauge track waiting to be laid. It was a full moon and the work continued until 10pm; then all laid down and slept beside the track ready to start again at 4am. In the section between Fontesvilla and Mile 40 there were a number of bridges that needed to be re-timbered and this caused some delay so that the work was finished at midday on Saturday. The first section to mile 20 was hampered by grass fires which gave off dense smoke on either side of the railway line but the first and second sections linked up on Sunday morning and the combined teams moved up the line to the third section. Here Varian met up with Lawley and with a final spurt the two ends met up near mile 42.

The first train consisted of Jack Tar pushing an open truck and pulling a passenger wagon and the tired teams who had worked day and night danced and yelled in wild excitement; the train contained masses of food and drink all of which were whole-heartedly consumed. Then Lawley and Varian rode the train back to Beira for more celebrations and a big supper at Lawley’s house…Varian was so tired he nearly missed the photo re-enactment the next day on 1 August 1900 of the arrival of the first train on the standard gauge at Beira.

Varian went down with an attack of malaria, but it was the last time he did because thereafter he slept under a mosquito net, much to the amusement of everyone and never caught malaria again.

Mapping the alternate blocks of land five square kilometres on either side of the line

The original concession of the Beira Railway from the Companhia do Mocambique had included alternate blocks of land five square kilometres (2,500 hectares) in size on either side of the line. For the first 97 kilometres (60 miles) to Bamboo Creek the railway line was straight and presented no difficulty, but thereafter the gradients became steep with many curves and it became impossible to mark off the blocks without overlapping adjacent blocks belonging to the Portuguese Government.

This meant Varian had to walk the entire 328 kilometres (204 miles) of line with a railway trolley and team of six natives with one member carrying a red flag several hundred metres ahead of the measuring party, then the trolley and finally a red flag several hundred metres behind. They walked all day and staying at a wayside station or ganger’s hut at night.

The telegraphist manning the station at Dondo was a character called O’Flaherty, where the line to Nyasaland, now Malawi and Moatize diverts from the line to Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe. Varian noticed a lot of lion spoor and a ladder led to the roof – O’Flaherty asked Varian to help deal with them by sitting with his rifle on the verandah during the night with a goat tethered ten metres away. His host however disappeared off to bed and Varian was left alone and dozed off to sleep. When he awoke the goat was gone and only lion spoor remained!

One day when the flag member was taking a rest a locomotive passed him without seeing the flag and entered a cutting without just as Varian and his team emerged from it. As soon as the engine driver spotted the trolley, he applied full brakes, but too late, Varian and his team leaped from the trolley and rolled down the bank, but the trolley was reduced to matchwood and old iron.

Although Varian was only employed on a temporary contract, more and more general construction maintenance work began piling up with the level of malaria and sickness among the staff of the Beira and Mashonaland Railway. Many of the temporary bridges needed replacing either because there were washouts or because the culverts collapsed and in one incident in Mashonaland a trestle bridge collapsed when it was burnt out by a veld fire or sparks from the wood-burning locomotive and a whole train was destroyed. Tunnelling into the banks and removing broken culverts which needed replacing with new concrete or steel culverts whilst trains travelled overhead proved challenging.

Then followed a survey on the feasibility of a branch line to the Rezende and Penhalonga gold mines in the Penhalonga valley. The survey showed it was possible to get over Christmas Pass with a gradient of 1 in 33, but only with heavy works and at a prohibitive cost. The Pass was notorious for lions which crossed the Cecil Kop Range at their lowest point and one night near the end of the survey Vivian was alone in his bell tent with his terrier “Vick” without a rifle when he was woken by baboons in the heights…a sign of leopard or lions. Later an unmistakable rumbling and watery cough told him it was lion. Varian lit a candle his dog tracked the lion with her body as it did a circuit around the tent with Varian in a cold sweat. Twice more the lion circled the tent until finally Varian heard its breathing and the swish of its tail in the grass before it moved off and the sound of the baboons again indicated the lion had moved off.

Pungwe River flats reconstruction

Despite all the improvements a continuing problem was the crossing of the Pungwe River flats between mile 28 and mile 41 from Beira and particularly at mile 35 (56 km) (35 miles) at Fontesvilla. In March when the river is in flood from rains falling in Zimbabwe which coincide with the spring tides, the river bank is only 30 cms (1 foot) above the water and the flats become inundated for several weeks. In the spring tides there was a rise and fall of 5 metres (17 ft) accompanied by a bore on the river and the alluvial banks were being constantly eroded. The original trestle bridge had been washed away and replaced by continuous plate girders of 15 metres (50 ft) on screw pile piers until they too proved unsuitable.

The original railway track bed proved too low and during the floods the track was under water for up to 11 km (7 miles) either side of Fontesvilla bridge, at times only the telegraph poles being visible and festooned by clinging snakes. A scheme to raise the line above flood level and to extend the Fontesvilla bridge and other bridges was prepared with a test project to carry out 3 km of the proposal. An engineer was recruited from England, but once he had seen Fontesvilla he remarked that he knew of better places to die in and sailed home by the same ship.

Varian had done a lot of the design work and knew the country and although somewhat junior to take charge of such a large project established his office in a wood-and-iron shack, 3m (10 ft) x 3m raised on piles 1.5 metres (5 ft) above the ground and close to the riverbank at Fontesvilla. The mosquitoes were bad, it was always damp and any surveying had to be done early before it became too hot. Extra steel spans needed to be added to Fontesvilla bridge and the track bed needed to be raised between 1 – 2.1 metres (3 – 7 ft) without interrupting the rail traffic. Fortunately only the weekly mail train rain in daylight; all goods trains ran at night so construction work continued through the day.

The preliminary phase was approved by Sir Alfred Beit, Chairman of the Beira and Mashonaland Railway, who arrived with Dr Jameson, Jones, Secretary of the BSAC, Sir Charles Metcalfe, the consulting engineer and Alexis Soley, chief engineer. However the rains were starting, so materials were ordered and Varian was ordered to Salisbury to take over the maintenance of the Ayrshire line which had just been completed to the Ayrshire and Eldorado gold mines and which had been built by George Pauling and Co using 2-foot gauge rails and rolling stock from the Beira Railway Company.

Ayrshire Line

Completed in 1902, the Ayrshire line had its teething troubles as soon as the rains started. There were washouts and derailments, but traffic serving the Ayrshire and Eldorado gold mines was light. In one bad derailment 16 km (10 miles) from the Ayrshire mine due to track subsidence it was thought the locomotive would only be recovered in the dry season, but the job was soon done by a team that arrived from the mine with jacks and gear on an ox-wagon.

Back to the Pungwe Flats

After the floods subsided work began again on the Pungwe Flats; the bad reputation kept men away but Varian managed to put together a team of 30 men including Greeks, Italians, Chinese carpenters, English, Scots and Irish, including O’Flaherty. It was a rough life camped on the Flats, fiendishly hot during the day with no shade, plagued by mosquitoes at night and no amusements to break the monotony. Small incidents became magnified and a Greek and Italian fight only ended when Jimmy Lawther, Varian’s assistant “Mr Jimmy” ended it by knocking out one of the contestants with a pick-handle.

The work employed 12,000 African employees and three ballast trains continuously. On the marshes double baulks of timber were placed under the rails whilst the ballast was shovelled under the track and firmly packed and the railway track had the appearance of a switchback during this type of construction.

On the old bridge the tidal surge of 5 metres (17 ft) meant the bottom of the girder was only a metre clear of flood level and any floating matter became caught in the cross-bracing. Gangs of men were kept continuously at work day and night breaking up the islands of vegetation and keeping the waterway clear…the chief danger then were snakes clinging to the branches.

Work hours were from sunrise to sunset at full swing as the progress of construction was developing into a race with the coming rains. There were unexpected delays, as when a swarm of bees invaded Fontesvilla at dawn and took charge until dusk. Those in mosquito-proof huts had to stay there, but all the goats, hens and ducks were chased away; a pet monkey tied to a tent was stung to death.

The Anglo-Boer War had just ended in May 1902 and parties of officers, sometimes with professional hunters, came up from South Africa on shooting leave and stayed at Varian’s camp at Fontesvilla. Varian bought an old sporting Martini rifle from Dan Mahoney, who killed 34 lions in Gorongoza in one month. Varian says there were some curious characters, all of whom achieved contemporary fame. Fred Johnstone, Paulin the Frenchman, “Bloody Bill” Upscher, “Johnnie” the Frenchman and Larsen the Swede. Hunting was always hard going on the Pungwe Flats as the only method was on foot with native carriers and as the East African territories opened up the professional hunters moved north.

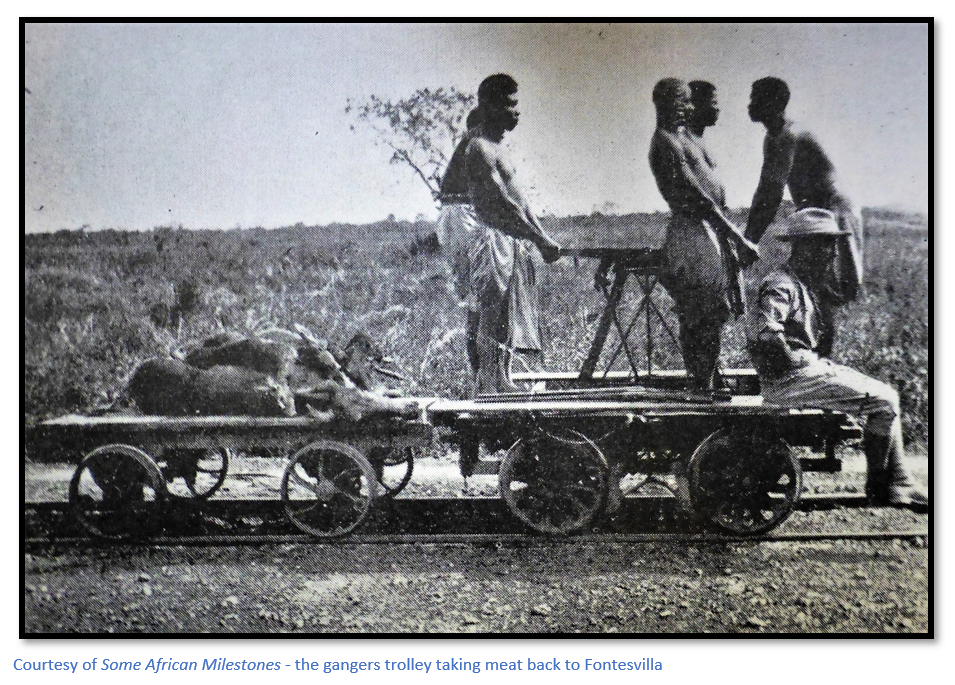

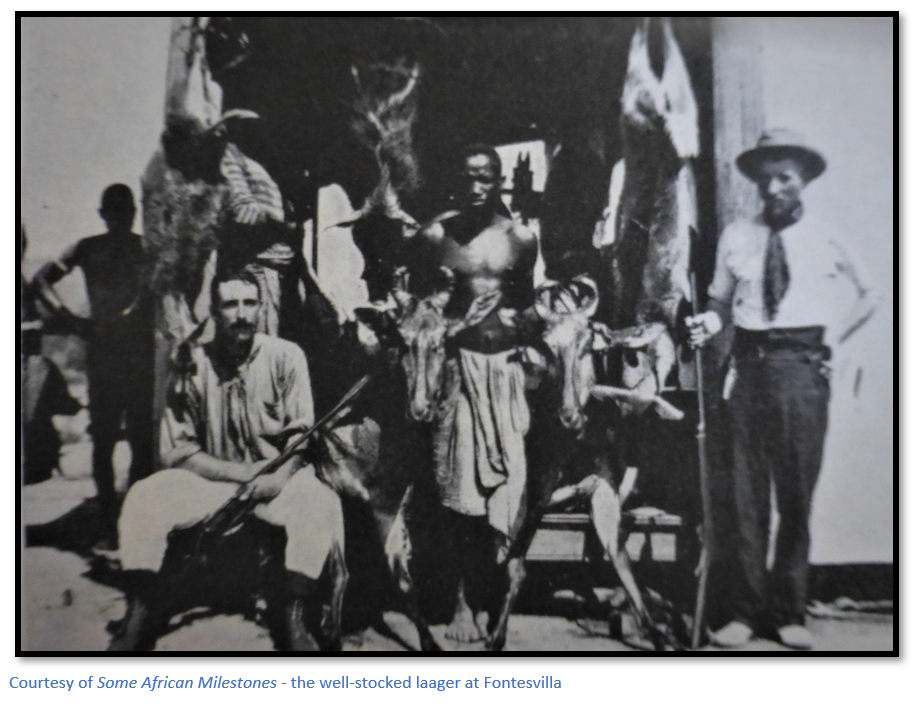

Varian hunted to provide meat for his employees and most Saturday evenings he and an Italian line inspector would go along the line to wherever game was plentiful at the time, sleep out for the night and each take separate sides of the line next morning to hunt. As each animal was shot, one native would be sent back to fetch the others who took the carcass back to the line where it was cleaned and taken by gangers trolley back to Fontesvilla for distribution.

However with time Varian decided that he preferred shooting wildfowl on either side of the line and it provided a pleasant change of diet from the eternal buck meat. They used bunches of reeds as cover, standing up to a metre deep in water and waited for the geese and ducks to fly in close…downed birds would be collected in by local natives. Wet through, there would be a change of clothes on the trolley and time for a whisky and soda before the ride back to camp. The larder at Fontesvilla was always well stocked with meat – buck large and small, geese, duck, teal, guinea-fowl and francolin. Wine was cheap, a barrel of red wine containing 56 bottles cost 24/- and visitors always welcome.

The work of raising the line was completed at the end of 1903 before the rains began, but still needed to pass the test of the next floods. The workforce had no malaria and only a few cases of dysentery which mystified the local medical authorities but which Varian put down to careful precautions. The next rainy season considerably damaged Beira with 25 cms (10 inches) of rain in one day, but the new works stood the strain and did so for the next thirty years.

Henry Varian’s career after the Beira and Mashonaland Railway

Varian had a career long relationship with all those engineers responsible for railway development in central and southern Africa including Sir Charles Metcalfe, George Pauling and Alfred Lawley – in most cases he was the connecting link between these men and those that physically carried out the construction.

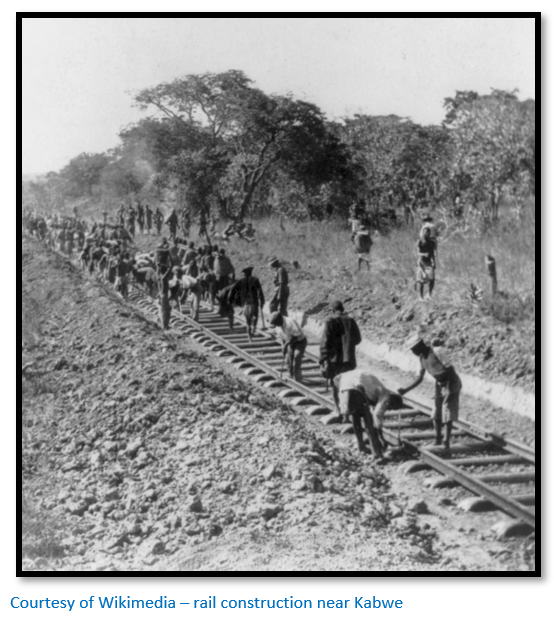

His next engineering appointment was as assistant engineer on the building of the Victoria Falls bridge under Georges Imbault a French engineer working for The Cleveland Bridge Company. The first locomotive with two loaded wagons across the bridge was the same Jack Tar which had carried out such good work on the BMR. [there is an article on the Victoria Falls bridge under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] Construction of the line then continued to Broken Hill, now Kabwe…on one occasion 9.25 kms (5.75 miles) of track were laid in a day…a record never exceeded and the rails reached the Kafue River three months ahead of the contract time of a mile a working day.

This was followed by a survey of the Victoria Falls as a source of hydroelectricity. Then in 1906 – 7 followed a survey of the Gwelo – Blinkwater railway in extremely wet weather driving in survey pegs for the proposed line.

Another of Varian’s major contributions was as chief resident construction engineer of the Benguela Railway that connected the Atlantic port of Lobito to the Angolan border town of Luau. This started in late 1907 and finished with Varian present at the opening ceremony on the Congo border at the Luau River on 10 June 1929.

As an explorer he made several reconnaissance surveys, sometimes over Livingstone’s old trails, sometimes through unknown territory. “Varian’s Trace” in Uganda was made with Tanganyika Concessions, at the request of Sir Robert Williams, who shared Cecil Rhodes vision for Africa and commissioned Varian to make a reconnaissance and report on the possibility and estimated cost of a railway across Uganda from the railhead, then at Kampala, to the Kilembe copper and cobalt mines.

Varian was an enthusiastic naturalist; his observations on topography, flora and fauna were keen and interesting; he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and a Life Honorary Member of the American Museum of Natural History with the distinction of having two animals named after him; the giant Sable Antelope (Hippotragus niger variani) and the Angolan Dik-Dik (Rhynchotragus damarensis variani)

In August 1914 he was commissioned into the Royal Engineers as a Captain; attached to Fourth Army in France, his work on railways during the Somme and Passchendaele offensives was highly valued, likewise his services in the Railway Intelligence Service in Palestine under General Allenby.

Born in 1876 he died in England in December 1960 aged 84.