The Rhodesia Air Training Group (RATG) 1940 – 1945

Places are referred to by their names in 1940: Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) Bechuanaland (now Botswana) Salisbury (now Harare) Gwelo (now Gweru) Selukwe (now Shurugwe) Umtali )now Mutare)

Introduction

In March 1935 Germany repudiated the disarmament clauses of the Versailles Treaty and reintroduced conscription. Various aggressive moves followed that culminated in the occupation of Czechoslovakia by Adolf Hitler's Nazi Germany in March 1939, and Godfrey Huggins, the Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) from 1933 – 1953, became convinced that war was inevitable and rearranged his Cabinet on a war footing. When Britain declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939, following the invasion of Poland, Southern Rhodesia issued its own declaration of war almost immediately and before any of the other Commonwealth Dominions.

Today, there are almost no memorials, monuments or plaques within Zimbabwe to mark the great efforts and personal sacrifices that were made by African and European servicemen and women and civilians to the Allied cause in both World Wars.

A separate article on this website Rhodesian Air Training Group (RATG) – a high price was paid in young lives gives details of all those who made the ultimate sacrifice and gave their lives training to be pilots and aircrew or auxiliary services at the RATG airfields.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) does an outstanding job in commemorating them. Their immaculately maintained cemeteries are in stark contrast to the disorder and chaos that characterises most of Zimbabwe’s municipal cemeteries. In the course of writing this article, photographs of every headstone at the CWGC cemetery’s at Harare and Gweru were taken. Any readers who would like an image for their family records should contact the author through the website www.zimfieldguide.com The fatality statistics are taken from the excellent CWGC website.

Southern Rhodesia’s preparedness before 1939

It was not until 1936-7 that the seriousness of Germany’s re-armament and aggressive intentions began to dawn on the citizens of Southern Rhodesia. In December 1937 a conference of the military representatives of the African colonies was held at Nairobi where it was agreed that they should be prepared to send troops outside their Colonies to defend British interests in Africa.[i]

With a white population of around 63,000 of whom 10,000 were fit and available for service, the decision as to who might go and fight and who must stay at home if the Colony was to survive economically was a difficult one. Mining, farming and industry had to continue as well as administration and other essential services and therefore only a limited number of civil servants, teachers, doctors and police could be released.

In 1936 a start had been made on air defence with an air training scheme at Belvedere with pilots being trained in a De Haviland Tiger Moth and two Major Moths by the local civilian flying school.[ii] The next year the scheme was extended to Bulawayo under Squadron-Leader G.A. Powell and Flight-Lieutenant V.E. Maxwell who were seconded from the RAF. Graduates went on to fly from the military airfield at Cranborne in Hawker Harts, considered rather antiquated even in 1939. The pupil pilots qualified for their wings when 20 hours of solo flying was completed.

There was no shortage of pilot applicants, but ground staff were in short supply and were recruited mainly from the motor and engineering trades. One recruit wrote, “the first thing we were taught was to use a file and this filing practice continued for many weeks. Afterwards we were split into groups and our training became more specialised. Riggers were taught to splice, to dismantle, assemble and repair aircraft wings, hydraulic undercarriages and so on. Fitters had to know all about aero engines; others became instrument repairers, armourers, M.T. mechanics - all were fitted in and licked into shape. Our training was of a blitz nature, but it was very thorough.”[iii]

A Brief History of the Rhodesian Air Training Group (RATG)

Air Vice-Marshall Sir Charles Warburton Meredith KBE, CB, AFC, who commanded the RATG believed the scheme was not only Southern Rhodesia's main contribution to World War II; but proved to be "one of the most important happenings in Rhodesian history" and JF MacDonald in the War History of Southern Rhodesia wrote it was “undoubtedly Southern Rhodesia’s greatest single contribution to the Allied victory.”

It led to economic development in Southern Rhodesia during a period that might otherwise have resulted in depression as the total local annual amount spent on the RATG greatly exceeded the government’s annual budget at the time.

Just as importantly, the RATG also proved in the long term, to be a most successful immigration scheme, since many of the former instructors, trainees and other staff returned to settle in Rhodesia after the war, some of them becoming leading citizens in the country. The white population of Southern Rhodesia increased to 135,596 by 1951, over double its pre-war size.

The Southern Rhodesia Air Force effectively ceased to exist after its last training course was completed on 6 April 1940. Its three squadrons became 44, 237 and 266 Squadrons, Royal Air Force, bearing the name of Rhodesia.

Southern Rhodesia was the last of the Commonwealth countries to enter the Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS) but the first to turn out fully qualified pilots and by size of total population, it was the largest training scheme. Eventually there were eleven operating aerodromes that required a huge national effort to build, maintain and staff—at the scheme's peak more than a fifth of the white population was involved in running them. Air Vice-Marshall Meredith made specific reference to the kindness and hospitality shown by the citizens of this country to all ranks who came for training.

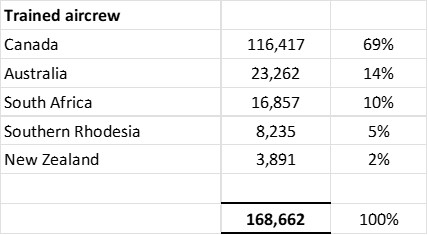

From May 1940 until March 1954 the Royal Air Force (RAF) had a presence in Rhodesia in the form of the RATG that trained aircrew for the RAF, from many different countries, including Great Britain, but also from Australia, Canada, South Africa, New Zealand, USA, Yugoslavia, Greece, France, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Kenya, Uganda, Tanganyika, Fiji and Malta as part of the Empire Air Training Scheme. Ashley Jackson's book The British Empire and the Second World War states the Rhodesian Air Training Group trained 8,235 Allied pilots, navigators, gunners, ground crew and others—about 5% of overall Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS) output.

Pilots comprised over 75,000 of the above.

During this time the RAF was the sole military force to fly in Rhodesian skies. After the end of World War II, in common with all other units, the RATG was run down and continued its training task at a much reduced rate. On 28 Nov 1947 The Southern Rhodesian Air Force (SRAF) was re-established as a separate unit and from that date until RATG closed, both the RAF and the SRAF took to the skies above Rhodesia.

The beginning of the Cold War brought a renewed need for aircrew training; the RAF re-vitalised the Rhodesian Air Training Group (in May 1948) that continued to grow with the Korean War, although nothing like its WWII level.

In March 1954, mainly for financial reasons, the decision was made to close the Empire Air Training Scheme and return RAF aircrew training to within the British Isles and the RATG was disbanded.

The Rhodesian Air Training Group badge, Courtesy of ORAFs.

The literal Shona translation being: “we will be strengthened in hundreds”

The beginnings of the RATG

Before WWII even started the British Air Ministry had begun planning to set up air training centres outside Britain; away from where there was air activity over the country and where the weather could be relied upon to be consistently good. Canada was the first country to be first chosen, the scheme being called the Empire Air Training Scheme.

Ultimately the countries involved in training aircrew comprising pilots, navigators, bomb aimers, air gunners, wireless operators and flight engineers included Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Southern Rhodesia and the United States.

At the outbreak of war in September 1939, the facilities in Rhodesia for air training were too small to be of any assistance to the Royal Air Force (RAF) Major D. Cloete, M.C., A.F.C. had been charge of a small air training scheme from 1937 of two RAF Officers and twelve other ranks who were seconded to Rhodesia with four Audax and six Hart aircraft and based at Hillside (later renamed Cranborne) but they only trained local Rhodesian territorial forces and personnel from the Rhodesia Regiment.

In 1938 the unit was separated from the territorial force and on 12th May 1938 the Governor, Sir Herbert Stanley, presented the first seven Rhodesian flying badges at a parade at Hillside.

There was an agreement that, in the event of war, Rhodesia would send an air unit to Kenya for service with the RAF and accordingly three Audax and three Hart aircraft were despatched on 28th August 1939, i.e. six days before the actual declaration of war. Some of the ground crew personnel were ferried in three Rapide civil aviation aircraft; the remainder and equipment travelled by road in vehicles that had been bought locally as motor transport for the air unit.

Lieut.-Col. C.W. Meredith arrived in Rhodesia in June 1939 as Staff Officer Air Services and Director of Civil Aviation. The British Air Ministry were very interested in expanding the air training into a much larger programme as they wanted most, if not all, air training out of England and to involve the training of other allied personnel as well as Rhodesians.

Photo courtesy of NAZ - Air Vice Marshal C W Meredith, Air Officer Commanding the Rhodesian Air Training Group, sitting at his desk at the Headquarters of the RATG in Salisbury.

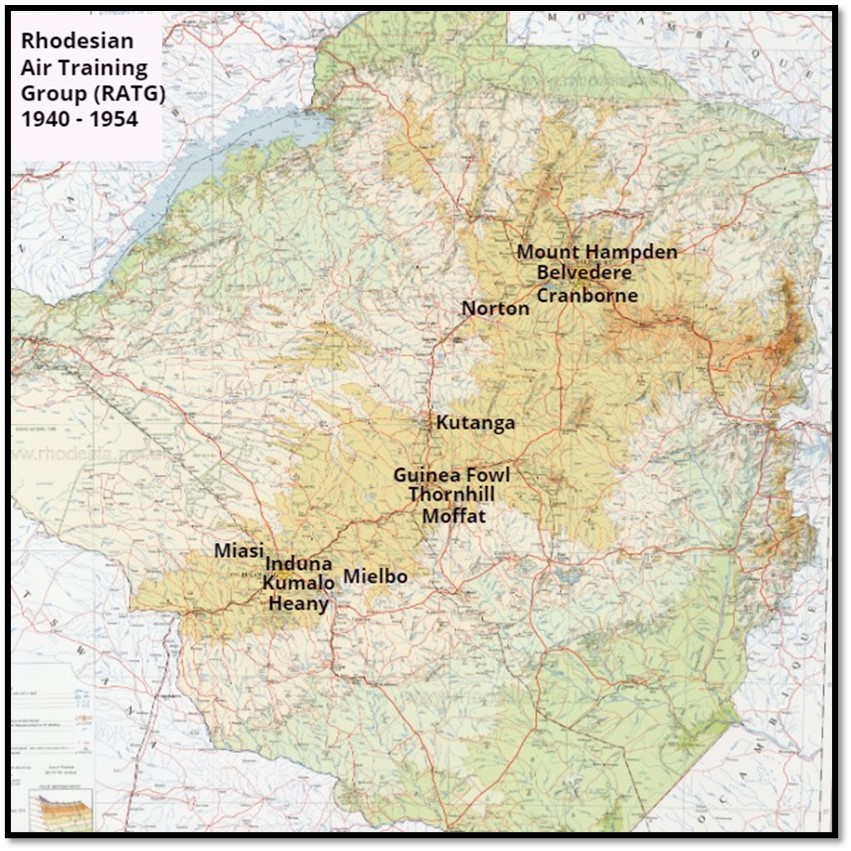

It was decided to start off in Rhodesia with one initial training wing through which pupils would pass on to three Elementary Flying Training Schools (EFTS) and matching them, three Service Flying Training Schools (SFTS) The establishment of six new Air Stations required a considerable amount of building, all of which had to be done using local resources. In Salisbury (now Harare) the EFTS was at Belvedere, with the SFTS at Cranborne; the second pair of schools would be established at Bulawayo (Induna and Kumalo) with the third pair at Gwelo (Guinea Fowl and Thornhill)

When Lieut.-Col. Meredith asked about finances he was told by the Air Ministry to: "get whatever you want from the Southern Rhodesia Government and we will settle up later." In fact, the Southern Rhodesian Government contributed to the war effort in a big way with the active endorsement of the programme by the then Minister of Defence, the Hon. R.C. Tredgold, and the Prime Minister, Sir Godfrey Huggins. In March 1940, the new Minister for Air was appointed, Lieut.-Col. E. Lucas Guest.

Photo courtesy of the IWM - North American Harvard IIA’s from No 20 SFTS being flown in formation by RAF trainee pilots at Cranborne, near Salisbury (now Harare)

Initial resources available to the RATG were very limited

At the official beginning of the training scheme on 23 January 1940, Meredith’s staff consisted of two territorial officers who had joined at the outbreak of war for administrative duties, and a typist. Initially RATG headquarters were based in the Salisbury suburb of Belvedere and with a heavy building programme ahead, the immediate need was for staff to cope with layouts, design and construction of airfields and hangers, supplies of building materials and finance and accounting.

At Cranborne, accommodation was a problem with the aircraft packed into one end of a hanger, the remainder being used as sleeping quarters! Total strength of the air station was 137 officers and other ranks with 16 aircraft available for training. These comprised four serviceable Harts, one Audax waiting rebuilding, eight serviceable Tiger Moths and one being repaired, and two Hornet Moths.

Major C. W. Glass MC, an architect by profession, was released from his civilian employment with the Public Works Department and agreed to transfer with the rank of Squadron Leader, later Wing Commander, with the title of Director of Works and Buildings. His Section was wholly responsible for the layout of Air Stations and the design and construction of buildings for whatever purpose. The staff consisted of architects, quantity surveyors and draughtsmen and other non-professional staff and controlled all building activity. Building was done by civilian contractors and at one stage virtually all the builders in the Salisbury, Bulawayo and Gwelo areas were employed on RATG work.[iv]

The finance and accounts section was handled by the Treasury Representative, C.E.M. Greenfield, later Sir Cornelius and Secretary to the Treasury and A. James, an accountant in civil life, who joined with the rank of Flight Lieutenant. James was killed in an aircraft accident on 28 August 1940 and his place was taken by Flying Officer G. Ellman-Brown, an accountant in civilian life, later Group Captain.

The supplies section was led by W.H. Eastwood, a Bulawayo businessman who joined with the rank of Squadron Leader, later Wing Commander, and the title of Director of Supplies. This Section was responsible for the location and purchase of all the building materials and equipment required by Works and Buildings. Both Ellman-Brown and Eastwood later became Cabinet Ministers in government.

These three Sections were the nucleus of RATG headquarters that later moved from Belvedere to Jameson Avenue, now the corner of Samora Machel Avenue / Simon Muzenda Street. Later sections that were added included air staff, air training, signals, armament, administration, equipment, engineering, personnel, medical and legal.

Photo courtesy of NAZ - The Corps of Signals band marches past RATG headquarters in Jameson Avenue, now Samora Machel Avenue, the buildings were erected in 1901 as the first BSA Company offices and still stand today!

At Durban in South Africa was a small unit to deal with the Harvard and Oxford aircraft arriving by sea that were then unpacked, assembled and tested for flying before ferry pilots flew them to their air stations in Southern Rhodesia. The crates in which they were packed were too big to be sent inland by rail. At Cape Town was a movement control officer who handled the arrivals and departures of trainees on special trains. At Port Elizabeth a representative dealt with incoming consignments of equipment.

The first Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) opens at Belvedere airfield

At the end of March 1940 the Rhodesia Herald reported, “About 100 officers, pilots and technicians of the RAF, who will lay the foundation of Southern Rhodesia’s part in the Empire Air Training Scheme passed through Bulawayo by special train this afternoon (28th March) and will arrive in Salisbury tomorrow morning.”

In April 1940 the Empire Air Force Training Scheme really began; but were known locally as the Rhodesian Air Training Group. In the same month the first draft of pupil pilots arrived at Belvedere, also the first of the Harvard’s airplanes having been assembled at Durban and flown to Salisbury via Bulawayo by Rhodesian pilots. The Belvedere air station was declared officially opened by Air Chief Marshall Sir Robert Brooke-Popham on 25 May 1940, in the presence of the Prime Minister Godfrey Huggins, E.L. Guest and C.W. Meredith.

The press statement quoted the Air Chief Marshall as saying, “of my knowledge of all the flying schools under the expanded Empire Air Training Scheme this is actually the first to start, but only by three days.”[v]

Photo courtesy of the IWM - North American Harvard IIA’s from No 20 SFTS being flown in formation by RAF trainee pilots at Cranborne, near Salisbury (now Harare)

The first batch of fliers graduate from the RATG scheme

The first group graduated from elementary flying training school in July and by early November 1940 the first pilots to be trained by the RATG passed out at Cranborne air station, five of whom were Rhodesians. When war broke out in 1939 the Air Ministry used the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR) as the principal source of aircrew into the RAF and this continued into the 1950’s.

The Southern Rhodesia war bill of 1940-41 was £2.5 million of which air stations, bombing ranges and quarters absorbed £1.08 million of capital expenses. Of the remaining £1.42 million, £0.9 million was used by the RATG in air training.

In fact the programme was such a success that it soon was realised that the Rhodesian Air Training Group could become vital to the war effort for training aircraft personnel. Although the bulk of the trainees were British, they also received Greeks, Yugoslavs, Free French, Polish, Czechs, Australians, New Zealanders and South Africans. Ezer Weisman, later to be President of Israel, trained as a pilot in Rhodesia. RAF training units would still be based in this country until a decade after WWII had finished.

A war time Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) gave a recruit 50 hours of basic flying instruction on a simple trainer, such as the De Havilland Tiger Moth. Pilot cadets who showed promise went onto training at a Service Flying Training School (SFTS) where they were awarded their “wings.” The SFTS provided intermediate and advanced training for pilots, including fighter and twin-engined aircraft, on the North American Harvard[vi] and Airspeed Oxford aeroplanes. Other trainees went onto different specialities, such as wireless, navigation, or bombing and air gunnery.

The complete flying training course was estimated to last six months, with two months spent on each stage - elementary, intermediate and advanced. During this period the various ground subjects were taught and each pupil had to complete not less than 150 hours of flying. But as the scheme developed it was decided the course could be shorter and the stages were reduced to seven weeks each and a short course of night flying became part of elementary training.[vii]

The Canadian scheme had been planned well before the war and much earlier than Rhodesia's; but because of the enthusiasm and support generated in the country, the first of the RATG stations, No. 25 Elementary Flying Training School at Belvedere, Salisbury (now Harare) was opened on 24th May 1940 in less than five months, and before the first Canadian station began operating.

Additional RATG flying schools come into operation

The next air station to come into operation was at Guinea Fowl, Gwelo (now Gweru) on 16 August 1940 taking twelve weeks from bare veld to the commencement of flying training. Its construction included provision of water supplies, water-borne sewerage and building a rail siding for the special trains bringing aircrew from Cape Town. The speed was amazing, on the same day of its opening, a special train from Cape Town drew into the siding with 500 pupil trainees.

The original programme of an initial training wing and six schools (Belvedere, Induna,[viii] Cranborne, Guinea Fowl, Kumalo, Thornhill) was increased to eight flying training schools (with Mount Hampden and Heany) and in addition, a bombing, navigation and gunnery school (Moffat) was opened for the training of bomb aimers, navigators and air gunners.

To relieve congestion at the air stations, six relief landing grounds for landing and take-off instruction were established (Parkridge, Sebastopol, Hienzani, Nkomo, Senale, Marrony) and three air firing and bombing ranges (Mias, Myelbo and Kutanga) Later another air station was established for the training of flying instructors (Norton) and this brought the total to ten air stations.

Two aircraft and engine repair and overhaul depots were set up and a central maintenance unit to deal with bulk stores for the RATG programme.

In late 1940 it was decided that Cranborne and Thornhill would be used to train single-engined pilots, or fighter-pilots, and Kumalo and Heany air stations would train twin-engined pilots.

In June 1941, the Southern Rhodesian Air Force Meteorological Service was set up at Belvedere to provide information to the pilots and instruction to navigators and the Meteorological Services Department of Zimbabwe is still at the original site on the corner of Hudson Avenue and Bishop Gaul Avenue.

Photo courtesy of the IWM – a flying instructor shows a pupil pilot where he must put his feet when climbing into the cockpit of a De Haviland Tiger Moth

Location of RATG sites

Training within the RATG scheme

Initial reception for pupil pilots was at Hillside Camp, later called Cranborne, where the Initial Training Wing (ITW) course lasted 6 weeks.

From here they went onto post initial training for 6 weeks, or to the Elementary Flying Training Scheme (EFTS)

Each EFTS intake had 320 pupils spread over the various air stations, about 50 from post initial training and another 270 direct from an ITW course and the course lasted 6 weeks. Those failing were posted back to an ITW course for re-examination.

The Service Flying Training Schools (SFTS) had an intake of 64 pupils every 6 weeks at each air station. Some went for air gunner training and others for air observer training.

The complete pilot's course initially lasted six months, ground subjects were also taught and each trainee had to fly at least 150 hours to qualify.

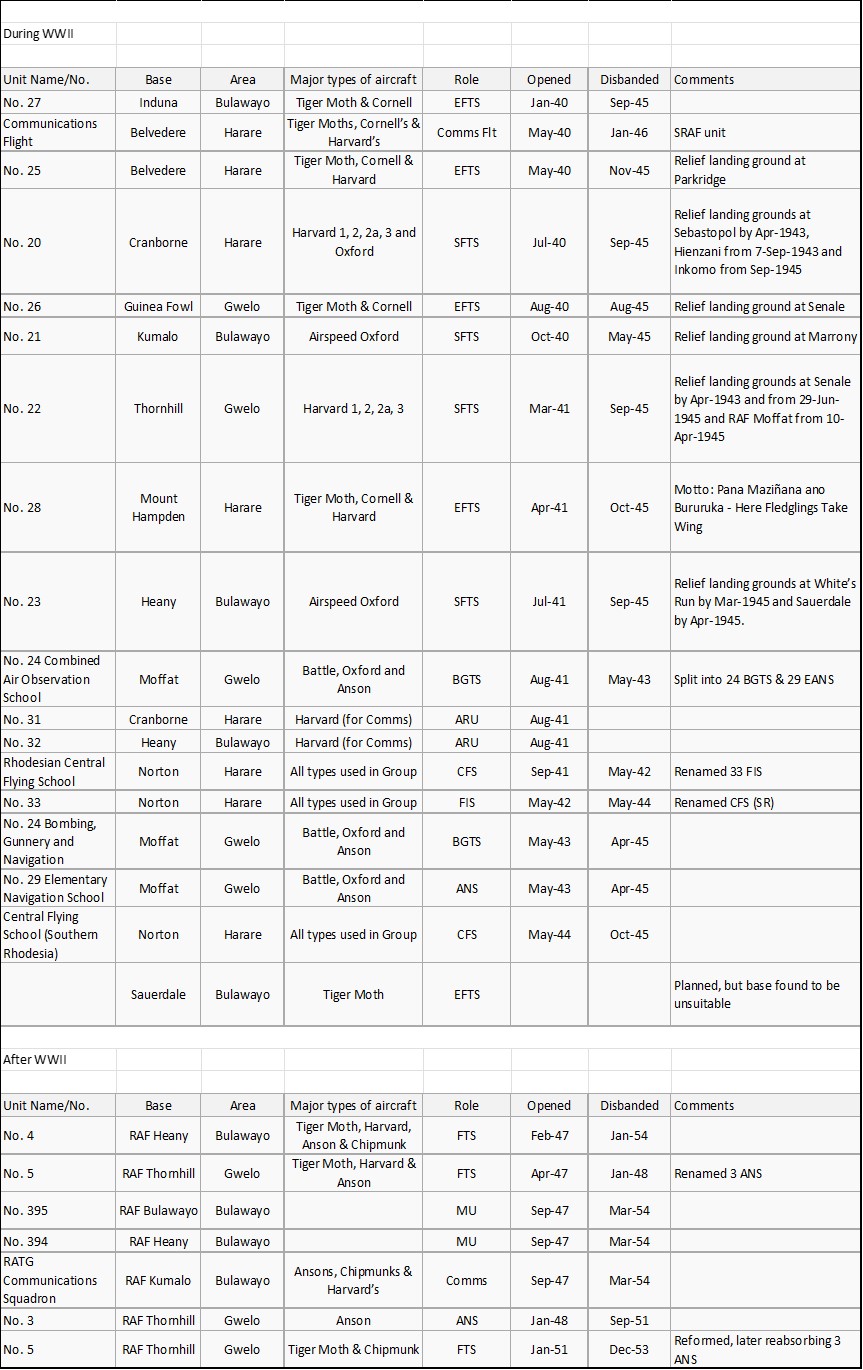

Abbreviations used above include: ANS = Air Navigation School, ARU = Aircraft Repair Unit, BGTS = Bombing and Gunnery, CFS = Central Flying School, EFTS = Elementary Flying Training School, FIS = flying Instructors School, SFTS = Service Flying Training School, FTS = Flying Training School, MU = Maintenance Unit, SRAF = Southern Rhodesian Air Force, RAFVR = Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve

The training aircraft used were Airspeed Oxfords, Avro Ansons, Fairey Battles, North American Harvards, De Haviland Tiger Moths and De Haviland Chipmunks and Fairchild Cornells.

After WWII RATG headquarters moved from Belvedere to RAF Kumalo and most training took place at RAF Kumalo.

Photo courtesy of the IWM - North American Harvard IIA’s from No 20 SFTS lined up with instructors and pilots at Cranborne, near Salisbury (now Harare)

GPS Coordinates for RATG bases

John Austin-Williams, Chairman of the South African Airways Society, researched for details of what building remains are visible today and matched them with contemporary aerial photographs and kindly provided GPS co-ordinates of the following RATG bases:

Readers interested in viewing the photographs of any of the individual RATG bases can contact John Austin-Williams on john@austinwilliams.co.za for his valuable research paper on the RATG bases.

RATG Air Stations

Brief details of some of the air stations are given below. One of the most important criteria for the selection of airfields was that they be in malaria-free areas that necessitated sites above 1,200 metres. Salisbury and Bulawayo were obvious choices; Umtali with its surrounding mountains proved too dangerous for pilot training and Gwelo was the third choice.

No.25 EFTS Belvedere

The original civil airport for Salisbury and opened in the 1930’s. Used by the Southern Rhodesia Air Unit from November 1935. No.25 EFTS was opened here on 24 May 1940, as part of the RATG. After WWII it was converted to civil use. Located on the other side of the city from Cranborne, it closed about 1956 when the new Salisbury Airport opened. The site has been completely built over as a residential area.

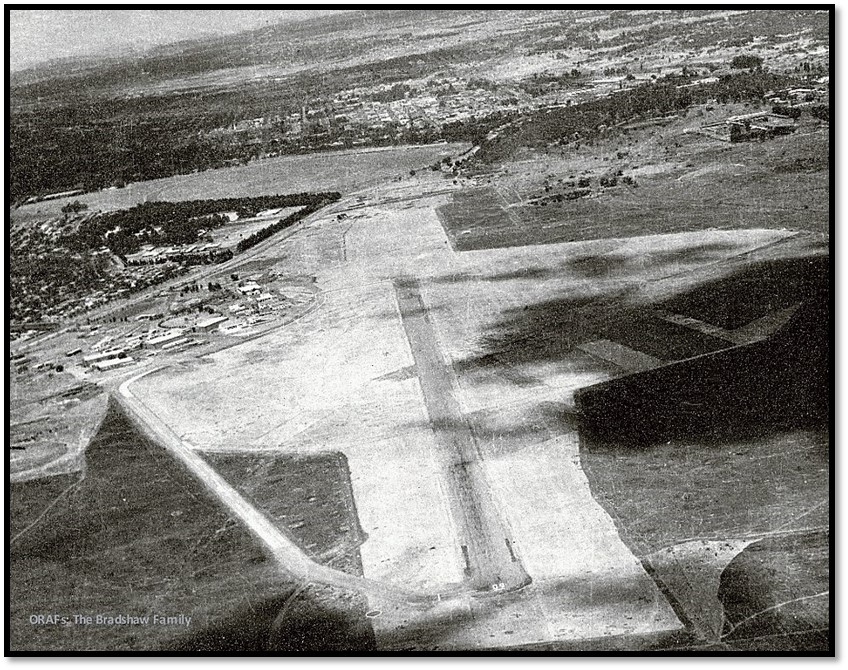

Courtesy of John Reid-Rowland and ORAFs – Belvedere runway with Salisbury (now Harare) in the background

No.20 SFTS Cranborne

Originally a flying school known as Hillside but renamed Cranborne in 1939 and located 5 kilometres from the city centre. A SFTS was opened here in July 1940, as part of the RATG. From 28 November 1947 it acted as the main SRAF air base and included the Spitfire squadrons. The rapid post-war expansion of the city of Harare forced its closure in 1952, when New Sarum airbase opened. The area is now residential with Cranborne Barracks occupying part of the site.

No.26 EFTS Guinea Fowl

An EFTS base during WWII with Thornhill as its SFTS located approximately halfway between Gwelo and Selukwe (now Shurugwi) south east of Gwelo. Originally called "Divide" as it was on the top of the watershed between Gwelo and Selukwe, after WWII it became a boarding school for boys from 1947 until about 1977. It was then used as a military base after Independence and is now a government school.

Tony Benn, the Labour MP for Bristol South-East for 31 years trained as a pilot on Fairchild Cornell’s and an extract from his diary is included at the end of the article.

No.23 SFTS Heany

This RATG base located near Bulawayo was used during WWII for Royal Air Force bomber aircrew training. It is not known when it closed, the two bombing ranges near Bulawayo were named Mias and Myelbo from the expression; “I don’t know Mias from Myelbo.”

Courtesy of IWM – a replacement Armstrong Siddeley Cheetah engine being fitted to an Airspeed Oxford at No 32 Aircraft repair Depot, Heany

No.27 EFTS Induna

The RATG booklet says the chief characteristic of Induna, from which the air station got its name, was the flat-topped hill some miles to the north-east that bears the native name "Ntabazinduna," "The Hill of the Headmen." Gordon Dodd, whose photographs of crashed De Haviland Tiger Moth’s feature in the article Rhodesian Air Training Group (RATG) – a high price was paid in young lives, was based at Induna. Not known when it closed.

Courtesy of IWM – pupil pilots arriving at No 27 EFTS Induna and being allocated their billets

Kutanga Bombing Range

East of Que Que, between the town and the Sebakwe Dam and used as a RAF bombing range during WWII.

Miasi and Mielbo bombing ranges

At Bulawayo pilot-trainees underwent the Elementary Flying Training Scheme (EFTS) at Induna (or Ntabazinduna) and on graduation moved on to Service Flying Training Schools (SFTS) for further training as twin-engined pilots on Avro Anson’s and Airspeed Oxford’s at Kumalo and on North American AT6A Harvard’s at Heany. Bombing, low and high level was practiced at the Miasi (northwest of Bulawayo) and Mielbo (east of Bulawayo) bombing ranges.

John Reid-Rowland points out that according to Pride of Eagles (second edition pp 106-107) they were so called because: "pilots and navigators had great difficulty in distinguishing between the two [so] they coined the phrase: “I didn't know Mias from Myelbow" although the spellings seem to have been bowdlerised on the map!

Courtesy of John Reid-Rowland - Miasi and Mielbo bombing ranges

No.24 BGTS Moffat

A RATG base during WWII used by No.24 Bombing, Gunnery and Navigation Training School operating Avro Anson’s from August 1941 to April 1945. Moffat was the first and only Bombing and Gunnery School in Southern Rhodesia.

Wikipedia - Avro Anson aircraft phased out of coastal patrol service in 1940 and thereafter used in a training role for pilots, bombardiers, navigators and air gunners[ix]

Located just south of Gwelo and now partly occupied by the Bata Shoe Company. The original control tower still stands and was used as the clubhouse by the Midlands Gliding Club with one of the original hangars still standing and used to store the gliders but is no longer known as Moffat.

There was little known about Moffat, but Kris Hendrix at RAF Museum supplied the following information included in the article. Gwelo’s European population was around 2,000 at the time; so uniformed young men from Guinea Fowl, Thornhill and Moffat were a common sight around town.

A cadet training to be a navigator would arrive from an EFTS where he would have learnt the elementary principles; at Moffat he would pass in stages through Air Crew Pool and elementary navigation, into the bombing and gunnery school, and to the average cadet, the climax of this would be his first flight. Most of a cadet’s time would be spent on navigational exercises, and towards the end of his course, long-distance flights to South Africa and even Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) There were a lot of night exercises, both in navigation and bombing. Class work included basic meteorology and astronomy, photography, aircraft recognition, signals and gunnery. The first course of air observers (their title was then changed to navigators) passed out from Moffat in December 1941.

A cadet gunner was at Moffat for a much shorter period and training was at a special gunnery section and they were accompanied on each gunnery exercise by an instructor. Initial training was on Fairey Battles and Airspeed Oxfords, but they were replaced by Avro Ansons with power-operated gun turrets.

Moffat became the main centre for training Greek aircrew; in early 1942 the first batch trained as air gunners at Moffat; initially they had interpreters, but they quickly picked up English.

“A fortnight after the opening of the station, the first batch of cadets reached Moffat to be trained as navigators. It is interesting to note the composition of that first course - 19 Rhodesians, 10 United Kingdom, 1 South African, 3 Australian, and 1 American…They were a cross section of Empire life, these men: farmers, clerks, schoolmasters, students, chemists….

A few days later the first pupil air gunners arrived - 16 Rhodesians, 10 United Kingdom and 3 Australians.”[x]

At the end of December 1942 Group Captain C. Findlay became Moffat’s new Commanding Officer and remained at the station until it closed. When he arrived the station was known as 24 C.A.O.S, a somewhat unfortunate name and the new title became Royal Air Force Station Moffat with three resident units: 24 Bombing, Gunnery and Navigation School, 29 Elementary Navigation School and Air Crew Pool.

On Saturday 14 April 1945 the final parade at Moffat was held. The last two courses; Air Gunners and Navigators were in front of the saluting base, with three Squadrons of station personnel behind, together with the Askari Corps. The Air Officer Commanding RATG, Air Vice Marshall CW Meredith took the salute. Meredith told them the Gunner’s course had achieved the best results of any school in the Empire Air Training Scheme and Moffat trained men had been awarded, so far as they could be traced at the time: one DFC and Bar, ten DFC’s and four DFM’s.

The official record shows that 778 navigators and 1,590 air gunners were trained at Moffat.

Photo courtesy of IWM – air gunners receiving class-room instruction at No 24 Bombing, Gunnery and Navigational School at Moffat, Rhodesia

No.28 EFTS Mount Hampden

RATG base during WWII with No.28 EFTS operating Harvard IIAs; located north west of Harare and called Charles Prince Airport after Charles Prince, a British RAF Officer during the war who stayed on in the country as the airport manager until his death in 1973. It became the home to the Mashonaland Flying Club and various aircraft charter companies.

No.33 Rhodesia Central Flying School Norton

RATG base during WWII with the Central Flying School operating Avro Ansons and Harvard’s. The RATG booklet describes Norton as the "University of the Training Group," where the cream of the RAF pilots were instructed.

John Reid-Rowland tells me that his late father-in-law, Sandy Singleton, was an instructor/pilot in the RATG during the period 1940-1944 and based variously at Belvedere, Cranborne and Norton. He and Robin Taylor informed me that Norton airfield was one kilometre west of the Norton junction on the A5 national road and is today Dudley Hall Primary School.

Courtesy of Google Earth – former No 33 Rhodesian Central Flying School at Norton airfield now Dudley Hall Primary School

Courtesy of John Reid-Rowland – aerial photo of Norton airfield in 1944

The landing ground is aligned to the north-east and in common with most of the RATG airfields, the taxiway apron has a solid cement surface and the airstrip is a grass runway.

John Reid-Rowland tells me that in the second edition of Pride of Eagles Page 266, the order for the closure of Norton as a training station and move to Cranborne was given on 14 December 1944. However, the runway remained in use until the late 1970’s when he personally landed at Norton airfield.

No.5 SFTS Thornhill

Located at Gweru and built on Thornhill farm in 1941, opened in March 1942. The airfield operated as an RATG base with No.26 EFTS. Reactivated in late 1946 for Royal Air Force aircrew training with No.3 Air Navigation School operating Avro Anson I’s and later Hawker Sea Fury T.20s, but later closed. Taken over by the RRAF in 1956 with the runway reconstructed and radar installed. Home of No.2 Ground Training School by 1967 for initial cadet pilot training. Currently home of the School of Flying Training, the Flying Instructors School and Nos. 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 Squadrons. Today it is the homebase of all the jet aircraft, since the is conducive to good take-off performance.

The Women's Auxiliary Air Service

The Women's Auxiliary Air Service was formed in August 1941 with Mrs D. Roxburgh-Smith, one of the first women in Africa to obtain a flying licence and who had done over 500 hours flying, as Commandant. The RATG booklet says they wore a uniform similar to that of the RAF with the same badges of rank but wore mufti when off-duty. Common rooms, generally known as the "Waaferies" were provided for them and at some of the air stations the "Waafies” lived-in.

Initially 106 female recruits attested into the Southern Rhodesia Women’s Auxiliary Air Service, but within months after training many hundreds of women previously occupied with family and household duties became capable of releasing airmen for more active work. They became clerks, teleprinter and telephone exchange operators, radio telephone operators, tailors, canteen assistants, instrument repairers, elementary mechanics, parachute packers and fabric workers and motor transport drivers. They also staffed the station sub-post offices and many of the officers became assistant adjutants and junior equipment officers.

Wikipedia: Women’s Auxiliary Air Service member folding and packing a parachute.

The Rhodesian Air Askari Corps

The biggest of the auxiliary services was the Askari Corps, officially formed in August 1941, but active in different a form in 1940 as armed guards and non-armed labour forces. At first a few civilians were employed at Cranborne and Belvedere aerodromes, controlled by British NCO’s, but soon the Labour Corps of the Rhodesian African Rifles was asked to supply labour, and later the Air Force Native Labour Corps was formed, with British officers and NCO’s seconded from the Rhodesian African Rifles. Entry was voluntary and the Rhodesian Air Askari Corps was formed under the command of Flying Officer T.E. Price, later Wing Commander, OBE.

The Corps divided into 2,000 in the armed section for station guarding and protection duties, and a further 3,000 for general duties for aerodrome work that included propeller-swinging, aircraft refuelling and marshalling, fitters' and riggers' mates, motor transport drivers, carpenters and assistants on fire tenders. Headquarters was at Belvedere, the old civil airport for Salisbury.

Photo courtesy of IWM: Air Askari’s assisting with aircraft maintenance.

Conscripted labour

The most controversial aspect of the RATG was the demand placed on Southern Rhodesia's black population during the early stages of WWII to provide conscripted labour to build the airfields.

The government assigned labour quotas to native commissioners for each district across the territory who in turn requested local chiefs and headmen to fill the quotas. This system, known locally as chibaro according to Charles van Onselen, had been in fairly widespread use during British South Africa Company rule between 1890 – 1923, but had fallen out of use by the 1930’s.

The chibaro workers received pay and provisions; but the salary of 15s/- per month was lower than the 17s/6d generally received on white-owned farms. It was met with widespread opposition and many men elected to run away rather than fill the quotas. "Hundreds, if not thousands", according to Kenneth Vickery, crossed into Bechuanaland or South Africa as many thought that after finishing building the runways they would be sent overseas as soldiers.

Allies in the RATG

Greeks, Yugoslavs and Frenchmen were trained as pilots, navigators and air-gunners in the Rhodesian Air Training Group many having escaped from their countries under the noses of the Germans via the "underground" through occupied Europe.

The Greeks who came had battled gallantly in their out-of-date aircraft against Messerschmitt’s and Stuka’s before managing to escape and often waited for weeks in the mountains for a small boat to take them from isle to isle of the archipelago, until eventually they would arrive at an Allied shore. As the Royal Hellenic Air Force was rebuilt in Egypt, so Southern Rhodesia became the nursery of its pilots.

For those who could not speak English, a special English course for allies was started at Bulawayo, and within three months most who could not speak English at all on entering the school, were able to go on to the flying course proper and follow lectures on highly technical subjects in English.

The greatest proportion of allies trained in the RATG were Greek and many of their pilots joined the three Royal Hellenic Air Force Squadrons, two fighter and one bomber, that operated in the Middle East and took part in the campaign of El-Alamein and afterwards in Italy.

Yugoslavs were trained in smaller numbers and absorbed into the RAFVR or volunteered for Marshal Tito's Forces; whilst the Poles, recruited and trained as RAFVR, once their training was completed, became part of the Polish Air Force.

Photo courtesy of the IWM: Tiger Moth’s with their cadet pilots probably from No. 25 Elementary Flying training School at Belvedere, near Salisbury (now Harare) leaving their aircraft.

Sir Ernest Lucas Guest, was appointed Rhodesia’s first Minister of Air on the outbreak of war, and together with Sir Charles Warburton Meredith, inaugurated and administered the Rhodesian Air Training Scheme and was appointed OBE in 1938 and KBE (Civil Division) in the 1944 New Year Honours List "for public services, especially in inauguration of the Empire Air Training Scheme." He was also appointed CVO by King George VI during the Royal Family's visit to Rhodesia in April 1947 and CMG in the 1949 New Year’s Honours List.

Courtesy of NAZ - Air Vice-Marshall C. W. Meredith AFC with Col. the Hon. Sir Ernest Lucas Guest, KBE, MP, Minister of Air and Internal Affairs for Southern Rhodesia

Photo Courtesy of IWM- No 24 Bombing, Gunnery and Navigational School at Moffat, Rhodesia, January 1943. A Fairey Battle aircraft towing a drogue sleeve while the student operates the power turret of Airspeed Oxford AS515.

Training to be an RAF pilot

At Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) the pupil pilot initially studied mathematics and the theory of flight, engines and airframes, some navigation and sent and received Morse code with a lamp. In addition to lectures, there was parade drill, physical training, cockpit drill, and an occasional camp inspection parade. At least 50 hours of basic aviation instruction were required on a simple trainer, such as the De Havilland Tiger Moth; more if the instructors felt the pupil pilot was slipping in on turns, or holding off a little too high on landings, or the take-offs were too bumpy. Once most of the mistakes had been ironed out, the pupil pilot was allowed to fly his first solo flight. Then followed more dual instruction, more solo, more dual, instrument and finally night flying.

Having sat and passed an examination, the pupil was ready for posting for more advanced training at a Service Flying Training School (SFTS)

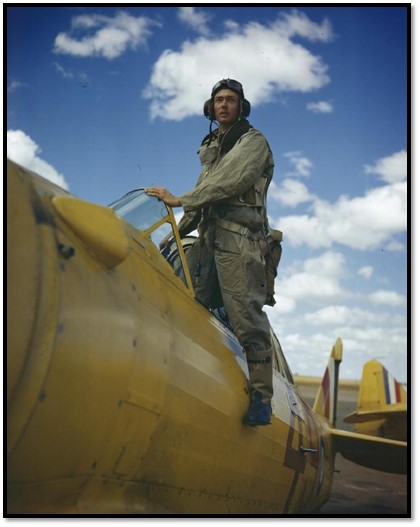

Instructor in front and pupil pilot behind in a De Havilland Tiger Moth trainer

A pupil pilot progressed with a group of colleagues to a SFTS where they would fly bigger and more powerful aircraft, such as the North American Harvard IIA’s, learn the elements of bombing and air firing, formation flying and night cross-countries.

The pupil pilot would be allocated to an instructor and in a Harvard trainer they would go through a sequence of gentle, medium and steep turns, take-offs and landings, forced landings and instrument flying, but with the added new complications of a variable-pitch propeller, retractable undercarriage, flaps, boost control, radio and a new array of instruments.

Lectures would continue with advanced plotting courses, studying the line of fall of various bombs, using a radio, understanding weather conditions, recognition of allied and enemy aircraft. Advanced instrument flying was practised on a link-trainer, landing by radio when the clouds “were down on the deck” and firing a machine gun whilst allowing for the deflection necessary when shooting at a flying bomber. Hours were spent “under the hood” using instruments to fly from point to point on a map, and long night-time cross-country flights.

Photo Courtesy of IWM - Pupil Sergeant D H Marshall climbing into a North American Harvard `49' at No.20 Service Flying Training School, Cranborne, Salisbury. He served as a ground crewman for 2 1/2 years before being accepted for flight training.

The Harvard’s Pratt & Witney 600 hp Wasp radial engine was much more powerful than the De Hviland Gipsey III 120 hp engine in the Tiger Moth. Advanced aerobatics were possible and low flying gave a great thrill. As the pupil pilot advanced there would be formation flights in vic (“V” shape) echelon and line astern, learning to watch his leader and keep one eye roaming around the sky. There would be flights to a relief landing ground from where they would practice flying each morning and then intercepting a twin-engined Airspeed Oxford that would have been tasked with bombing a target in the same area.

Wikipedia - The Oxford Advanced Trainer (nicknamed the 'Ox-box') had dual controls and was used to train pilots, navigators, bomb aimers, gunners and radio operators.

Finally, the great day arrived when the pupil pilot received his wings. This left just time for a final party in town to celebrate the event before he was sent north to an operational unit in North Africa or the UK. Here he would be introduced to the Spitfire whose details would be carefully explained with much cockpit drill before he was allowed his first solo with no second cockpit to carry a watchful and helpful instructor.

Rapid growth of the Rhodesian Air Training Group

J.F. MacDonald writes, “it is to her share in the Empire Training Scheme that we must look to find the Colony’s most potent influence in the war effort. Every month saw an increasing acreage of virgin bush being transformed into air stations or landing grounds and an increasing number of training aircraft purposely voyaging the skies. Several stations were built on the bare veld many miles from the distractions of the nearest town. With the sites selected, planning and erection of buildings went ahead at top speed and heavy demands were made on those responsible for the work. Barrack-rooms, offices, hangars, sheds, flying field strips and all the appurtenances of a small town - macadamised roads, electric lighting and water-borne sanitation - came into being in a waste of grey dust and thorn…”[xi]

At its peak there were about 12,000 adult male white personnel and about 5,000 adult male Africans employed by the RATG.

The final financial responsibility accepted by the Southern Rhodesia government for the RATG programme was for:

- The capital expenditure on land and buildings and ancillary works for the whole of the Air Training Scheme including quarters and housing.

- The cost of all barracks equipment at air stations.

- The cost of RATG Headquarters.

- All pay and allowances for Rhodesian personnel serving in Rhodesia.

- Make up pay and family allowances for Rhodesians serving abroad as there was a difference between RAF and Rhodesian rates.

- A cash contribution of £800,000 p.a. towards the operating costs of the Air Training Scheme.

Southern Rhodesia’s contribution to the war effort

Hugh Beadle, the Chief Justice, on 17 January 1941 gave The Rhodesia Herald details of the country’s contribution to the war effort in the first eighteen months, “… in the Air Force there were 1,416 (on full-time military service) including 17 trained pilots in Rhodesia as instructors and in the communication squadrons and 92 pilots outside the Colony and 259 men in training. There were also 64 Rhodesians waiting their turn to be absorbed in the Empire training schools.

We would probably have about 400 pilots on active service eventually. On the same proportion that would be 40,000 pilots for the population of Great Britain…”[xii]

Initially there had been a great shortage of building materials and labour, but this was quickly overcome even at the remote airfields that were being constructed. MacDonald continues, “There was no need to teach Rhodesians how to ‘make do’ in such circumstances. In no time they would convert an empty anthill into an oven for baking bread; they would rig up a shower from petrol tins and would have some damp sacks round a gauze framework to cool their beer. One detachment liked eggs for breakfast, so they procured some fowls. The rooster came to an unfortunate end. Someone bet that he would fly to earth were he thrown from an aircraft a few hundred feet up. He didn't.”

Courtesy of IWM - Airspeed Oxford airframes under repair in a hangar at No. 32 Aircraft Repair depot, Heany

Tony Benn, the Labour MP trained on Fairchild Cornell’s with the RATG at No.26 EFTS Guinea Fowl near Gwelo

Tony Benn joined the RAF in 1943 for training as a pilot. He was posted to Southern Rhodesia for pilot training and the entry below is on the day of his first solo in a Fairchild Cornell PT-26 trainer at No.26 EFTS Guinea Fowl.

Wednesday 14 June 1944 - At six this morning Crownshaw [the instructor] told me to get into 322 straightaway, a PT-26 Cornell trainer. I apologised to him for boobing the check yesterday and he remarked that they were really only nominal things and that they didn’t really matter.

We taxied on to the tarmac and I got out and walked back with Crownshaw. He said we’d just have a cigarette and then go up again. I was very surprised but put it down to a desire on his part to finish me off ready for another check tomorrow. However, we took off, did a circuit or maybe two, and then as we taxied up to the take-off point, he said to me, ‘Well, how do you feel about your landings?’ I replied, ‘Well, that’s really for you to say, sir.’ He chuckled. ‘I think you can manage one solo,’ he said. ‘I’m going to get out now and I’ll wait here for you,’ he went on.

So this was it, I thought. The moment I had been waiting for came all of a sudden just like that. ‘OK, sir,’ I replied. ‘And don’t forget that you’ve got a throttle,’ he said. ‘Don’t be frightened to go round again -OK? And by the way,’ he added -he finished locking the rear harness and closing the hood, then came up to me, leant over and shouted in my ear, ‘you do know the new trimming for taking off?’ ‘Yes, sir,’ I replied, and he jumped off the wing and walked over to the boundary with his ‘chute.

I was not all that excited. I certainly wasn’t frightened and I hope I wasn’t over-confident but I just had to adjust my mirror so that I could really see that there was no one behind me.

Then I remembered my brother Mike’s words: ‘Whatever you do don’t get over-confident; it is that that kills most people and I only survived the initial stages through being excessively cautious.’ So I brought my mind back to the job, checked the instruments, looked all around and when we had reached 500 feet began a gentle climbing turn. It was very bumpy and the wind got under my starboard wing and tried to keel me over, but I checked it with my stick and straightened out when my gyro compass read 270 degrees. Then I climbed to 900, looked all round and turned again on to the down-wind leg. By the time I’d finished that turn we were at 1,000 feet, so I throttled back, re-trimmed, got dead on 180 and I felt pretty good about things.

I thought I was a little high as I crossed the boundary so I eased back to 800 rpm, and as I passed over, I distinctly saw Crownshaw standing watching where I had left him. Now we were coming in beautifully and I eased the stick and throttle back. A quick glance at the ground below showed me to be a little high, so I left the stick as it was, gave a tiny burst of engine and as we floated down I brought both back fully. We settled, juddered and settled again for a fair three-pointer.

I was as happy as could be. I taxied up, stopped and braked. Try as I did, I couldn’t restrain the broad grin which gripped me from ear to ear and Crownshaw, seeing it, leant over before he got in and said ironically with a smile, ‘Happy now?’

I was more than happy, I was deliriously carefree, and as he taxied her back I thought about it all and realised that the success of my first solo was entirely due to the fine instruction I had received; it was a tribute to the instruction that I never felt nervous once, and all the time had imagined what my instructor would be saying, so used had I got to doing everything with him behind me. We climbed out, and attempting to restrain my happiness I listened while he told me where and what to sign. Then I wandered back to my billet and one of the greatest experiences of my life was behind me. The lectures were pretty ordinary, and it being my free afternoon I had a bit of lemonade in the canteen and wrote this.[xiii]

The following is taken from the archives of the BBC in WW2 – People’s War and was contributed by Derek Wilkins (Article A1122337) on 25 July 2003

As a boy I was interested in aviation and so joined the Air Defence Cadet Corps (then the Air Training Corps) at the outbreak of war in 1939. As well as the normal military basic training we followed the aircrew syllabus of navigation, meteorology, signals, armament, aircraft recognition etc, giving us a head start over other pilot training aspirants.

All RAF aircrew were volunteers, so at the age of 17 I presented myself at RAF Uxbridge for stringent medical and aptitude tests. A year later I received my call-up papers and reported to the ACRC (Aircrew Reception Centre) at Lord's Cricket Ground to be inducted and inoculated. Under the stern eye of WG Grace in the sanctum sanctorum, the Long Room, my lower regions were closely inspected for ghastly diseases.

There followed three months at ITW (Initial Training Wing) Newquay for more PNB (Pilot/Navigator/Bomber) ground training, followed by two months flying DH82a De Havilland Tiger Moths at 26 EFTS (Elementary Flying Training School) Theale. This was the point at which one passed or failed for further pilot training and was put into an aircrew category. I had flown 13 hours dual without going solo.

All AC2(C)s (Aircraftsmen Second Class) then passed through ACDC (Aircrew Despatch Centre) Heaton Park, Manchester for shipping to training in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), Canada and South Africa under the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan or to the USA under BFTS (British Flying Training School) or the Arnold or Towers' Schemes.

Cadets were transported to their destinations in troopships, escorted in convoys by the Royal and Allied Navies. In order to confuse the enemy, a sola topi (a type of hat) and tropical kit was issued to those who were Canada-bound, and heavy clothing for those destined for Africa. I sailed in SS Orbita, a vessel used as a troopship in WW1, which had turned around quickly at Liverpool without victualling.

Orbita sailed in late December 1943, picking up the naval escort north of Ireland in a convoy of some 50 ships to protect against the Atlantic U-boat packs. Accommodation for 2,000 troops was in 200-man troop decks six decks down, close to the engine room. Hammocks swayed above the mess tables. We were ignorant of our destination. The voyage took six weeks through the Straits of Gibraltar, Port Said, the Red Sea, and Mombasa. Christmas, near my 19th birthday, was off Gibraltar, celebrated with a single small bottle of beer. By Mombasa we had exhausted our stores and broached our emergency rations.

How marvellous it was to reach the South African port of Durban, and to be met on the quayside by the singing of 'The Lady in White'. There were lights, not experienced for three years in wartime UK, and unrationed, glorious food. Paradise! We were put up in concrete ex-pigsties at Clairwood Camp and fed Koo jam and bread. Ecstasy! But disastrous for shrunken stomachs.

After two days by rail to Bulawayo via Bechuanaland there was six weeks more square bashing at the Rhodesian Air Training Group (RATG) ITW at Hillside. There were shouts of 'gechur knees brown', resulting in a visit to the Indian tailor to smarten up the bizarre service issue tropical kit. And then, at last, the real business of learning to become a military pilot within the best training scheme in the world in the best place, Southern Rhodesia.

My posting was to No. 27 EFTS at Ntabazinduna near Bulawayo, a grass airfield in the shadow of the kopje, or hill, reputed to have been close to the HQ of Lobengula. We flew DH82as, Tiger Moths and PT26s (US Fairchild Cornells). I went solo after another 8.5 hours. Training included cross countries, instrument flying under the hood and night flying using goose-neck flares. At the end of EFTS I had logged some 118 hours. Many fellow aspirants had fallen by the wayside.

Southern Rhodesia in those days was wild frontier country with few landmarks, so good dead reckoning navigation was vital without radio. The veldt was alive with huge herds of game which we shamelessly buzzed. Crews got lost, sometimes fatally. Survival training was taken seriously. There was the famous myth of the aircrew killed by bushmen giraffe hunters in the desert basin west of Bulawayo. Sadly, the Bulawayo cemetery contains RATG graves.

Then on to No. 21 SFTS (Service Flying Training School) at Kumalo, Bulawayo. Kumalo had a single concrete runway with a cemetery at one end and a sewage farm at the other, so you were well catered for. There we flew Airspeed Oxfords, a twin Cheetah engined aircraft, a military derivative of the Courier, and the North American AT6A Harvard. Some flying was done from satellite bush airfields such as Woollandale. Bombing, low and high level, was practiced at the ranges Miasi and Mielbo, named so in the African tradition.

The citizens of Bulawayo were most hospitable to the cadets, providing a much-appreciated social break. The Bodega Bar was also popular. At the end of the course we staged a squadron formation flypast over the city to thank them all as best we could. After some 300 hours of flying training I received my flying badge (wings), a commission and an offer to remain in SR as an instructor, which I declined in favour of going to an OTU (Operational Training Unit). How would my life have gone had I stayed?

But before OTU was a posting to the Maritime Reconnaissance Course at No. 61 Air School (SAAF) at George, Cape Province in South Africa. The flying there concentrated on sea navigation using dead reckoning and astro-navigation. Ship and aircraft recognition mainly concerned the Japanese navy and air force, indicating our final destination to be Coastal Command in the Far East war. We flew in Avro Ansons as navigators, equipped with wireless operators and pigeons in case of red on blue, the next stop being the South Pole. The operational area was between Cape Town and Port Elizabeth. All shipping rounding the Cape was logged and photographed and a look-out kept for U-boats heading for the Indian Ocean.

After graduation in April 1945 we flew to the Middle East from Durban in a Short 'C' Class Empire flying boat via neutral Mozambique. We had completed two years of intensive training over some 320 hours of flying; considerably more than the 200 to 250 hours average for the BCATPS as a whole. According to John Golley in his book Aircrew Unlimited, RAF pilot training was much more extended and thorough than that of the Luftwaffe and the Russian air force. Thanks to Southern Rhodesia, the other Commonwealth countries and the USA, we ended the war with a surplus of well-trained aircrew.

1945 and the RATG effort begins to wind down

As the war drew to its close the flying training camps began closing and the activities of the RATG began gradually to wind down. “The casualty rate among pilots had been less than was expected. Large reserves had been built up. And with the end of the war insight the demands of the RAF for trained pilot personnel became less pressing. Air Vice Marshall Meredith, his staff and the whole colony could view with pride what was undoubtedly Southern Rhodesia's greatest single contribution to the allied victory - the training under the Empire Air Training scheme of thousands of air crew members to man the aircraft...”

Air Marshall Sir Bertine Sutton paid the following tribute, “I would like to recall that No.1 Rhodesian Squadron (now 237 Spitfire Squadron) was the first Dominion Squadron in the field when war broke out. It was indeed, at its station at Nairobi, two days before war was declared. There it began its war career and nearly five years later we find it covering the landing in the South of France.

Rhodesia was also the first in the field in connection with the Empire Air Training Scheme. It was in Rhodesia that the first EFTS school was opened in May 1940, a week before the opening of the EFTS schools in Canada.

No.44 squadron can also claim a ‘first’ in that it was the first squadron to be equipped with Lancasters and I think the first to have its own Rhodesian commander - Wing Commander FW Thompson.

The Third Squadron, No.266, is a Typhoon squadron which began operating from Normandy very soon after D-Day.

And all this from Rhodesia with, I believe, a white population of under 70,000. But this 70,000 has placed no less than 8,000 men in the fighting services, of whom as many as one-quarter are in the RAF. That is an outstanding contribution and I believe it would have been greater had it not been necessary to restrain the flow of volunteers in order to preserve essential services.

Well, the Air Force pays its tribute to those 2,000 Rhodesians and expresses also its thanks for the generous hospitality shown to our air crews who were trained in Southern Rhodesia and thoroughly enjoyed their stay there.”[xiv]

RATG pilots transition to civilian life

The many Rhodesians that had served with so much credit in the various theatres of war began to return to Southern Rhodesia where they mostly transferred to the Southern Rhodesia Air Force Reserve and settled back into civilian life. They were paid according to their ranks for up to three months until they took up employment again.

Roll of Honour and Airforce honours and awards

Any reader who wishes to have the details of those Southern (Zimbabwe) and Northern Rhodesians (Zambia) who gave their lives KIA or KOAS, was taken POW, or received British and foreign awards whilst serving in the various Air force units is advised to check Appendix 3 and 5 of A Pride of Eagles or contact the website as the author has a copy.

Acknowledgements

Sir Charles Meredith. The Rhodesian Air Training Group 1940-1945. Rhodesiana Publication No. 28, July 1973

D. Newnham. Rhodesia and the Royal Air Force - Rhodesian Air Training Group (RATG) – An Overview. With kind permission of the website www.ourstory.com/orafs

Booklet published Under the Authority of the Air Officer Commanding the Rhodesian Air Training Group, courtesy of ORAFs

The Rhodesia and the RAF booklet published by the RATG kindly loaned to me by Robin Taylor

B. Salt. A Pride of Eagles. The Definitive History of the Air Force 1920-1980. Covos Day 2001

Commonwealth War Graves Commission for the fatality statistics

K.P. Vickery. “The Second World War Revival of Forced Labour in the Rhodesia’s". International Journal of African Historical Studies. Boston: Boston University. 22 (3): 423–437. 1989

C. van Onselen. African Mine Labour in Southern Rhodesia, 1900-1933.

Wikipedia

Kris Hendrix. RAF Museum for information on No.24 BGTS Moffat

J.F. MacDonald. The War History of Southern Rhodesia 1939-1945. Rhodesiana Reprint Library, Silver Series Vol 10 and 11. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1976

John Reid Rowland for facts, photos and GPS location table, Imperial War Museum (IWM) National Archives of Rhodesia (NAZ) Wikipedia and for photos and images

Notes

[i] The War History, P8

[ii] A Pride of Eagles, P18

[iii] Ibid, P33

[iv] Ibid, P58

[v] Ibid, P47

[vi] The RAF Museum states 17,096 Harvard trainers were built during World War Two with over 5,000 supplied to British and Commonwealth Air Forces. As conflict became inevitable a massive increase in pilot training was required and the RAF soon turned to the United States to acquire the trainer aircraft. A contract for two hundred Harvard’s was placed in June 1938. The majority of flying training units were in Canada, Southern Rhodesia and the United States as this provided safer conditions for training.

[vii] The night flying at Salisbury, Bulawayo and Gwelo drew many complaints in the local newspapers, but also indignant replies from those who had suffered German air raids in England and considered locals were not sufficiently grateful for being let off lightly!

[viii] Initially it was decided that the elementary flying school for Kumalo air station would be at Sauerdale, but the surface proved unsuitable and Induna was chosen instead.

[ix] The website https://www.airvectors.net/avanson.html states a remarkable 11,020 Avro Anson’s were built in the UK and Canada.

[x] The War History, P173

[xi] Ibid, P172

[xii] The War History P171 has 40,000 but A Pride of Eagles P87 quotes the same speech, but with a figure of 400,000 pilots rather than 40,000! I calculate 400 of a 1940 white population of 63,000 equals 305,000 of an estimated UK population of 48 million

[xiii] The Benn Diaries: 1940-1990 can be viewed online

[xiv] The War History, P608