Ranche House (1899) - Ken and Lillian Mew

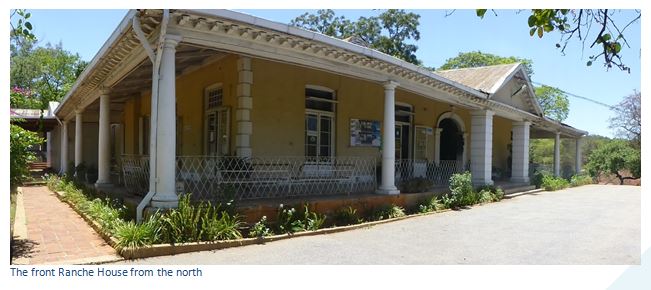

Rotten Row opposite the Museum of Human Sciences, Architect: possibly J.A. Cope-Christie, Client: United Rhodesian Goldfields, Builders: J&R McChlery for £10,000

GPS Reference: 17⁰50′09.56″S 31⁰02′18.72″E

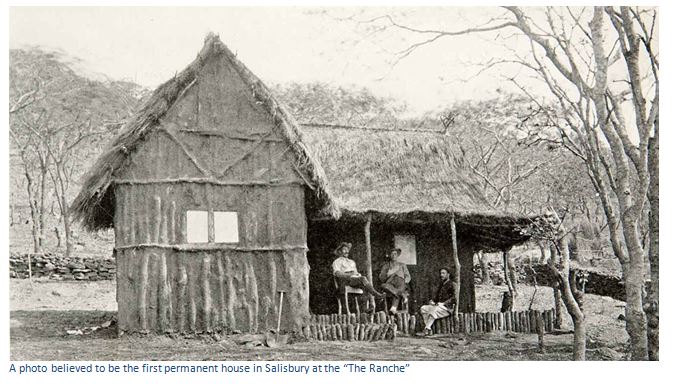

The large stand of over 5 hectares on the western side of the kopje given to Johnson, Heany and Borrow gave rise to its name “The Ranche” and is where Ranche House College now stands. In October 1890, it consisted of “an enormous store made entirely of wagon sails and a few marquee tents for an office, mess tents and tents to sleep in.”

In 1895, the Ranche house stand was bought by the United Goldfields Company who also completed the construction of Ranche House in 1899.

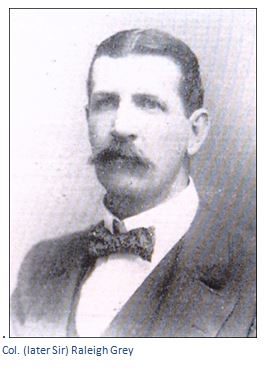

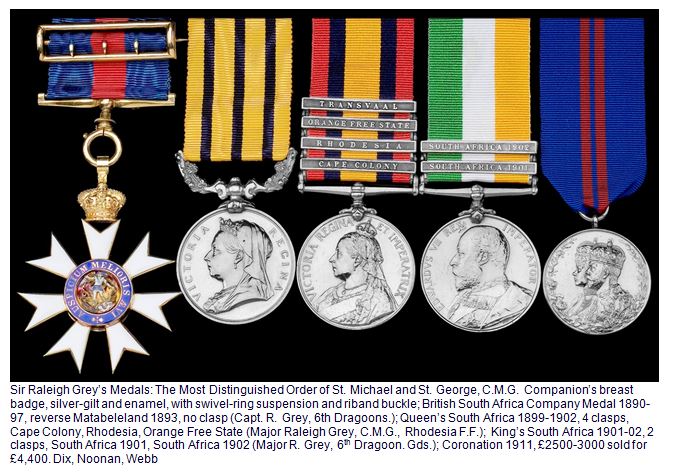

Ranche House’s first resident was Col. (later Sir) Raleigh Grey, the Company’s Managing Director and it was Lady Grey who organised the building of much of the garden terracing and planted many of the mature shrubs and trees that still remain today. It was the first house in Salisbury (now Harare) to be lit with carbide-acetylene gas lamps, when paraffin lamps were in almost universal use.

Grey an aristocrat was married to Mary Isobel Cadogan and brought his own servants from England and had them dressed in livery. He brought to Ranche House the way of life of a Victorian English country gentleman, complete with horses and hounds. It remained one of the town’s finest houses for many years.

Ranche House was sold to the Government in 1927 after the original stand had been sub-divided. It was then occupied by a series of ministries and public civil servants, including Sir Robert Tredgold, the Chief Justice and twice acted as Government House of Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe)

The house was originally “U” shaped around a rear courtyard, which has since been roofed over. The kitchen and pantry are in the southern leg of the “U.” A central passage follows the shape of the house with rooms leading off both sides. A wide verandah roofed with heavy timber beams and dentiled eaves is the most distinctive feature of the house. The front entrance has an oversized gable providing a classical portico supported on large rusticated square piers that are seen at their best as the visitor approaches up the steep flights of stairs from the car park. The roof is largely hidden except for the two elliptical louvered dormer ventilators on either side of the front entrance.

The entrance features small pane Venetian doors that are set into a keystoned basket arch leading into the entrance hall. The interior timber floors and panelled doors have their original brassware; the ceilings are the original plastered linen framed into panels. One of the fireplaces has had its surround removed; the other in the principal’s room is granite with the blocks shaped into a Tudor arch.

From 1961, the Ranche House was occupied by Ken and Lilian Mew, its most celebrated occupants.

Ken Mew was born in 1915 and grew up in the Liverpool slums, one of eight children of an abusive and thieving father and a gentle mother who attempted to keep the family together, even as her husband spent their hard-earned money on alcohol and prostitutes. His father was a second-hand dealer who would send Ken out with a horse-drawn cart to walk the streets yelling "rags and bones." "One time, when a householder sent him down into the basement to fetch an old piece of furniture, Ken's father saw they had copper pipes," said Peter Hamilton, Mr. Mew's son-in-law. "He hammered the pipes flat at two spots to stop the flow, then chopped the pipes out and smuggled them out of the basement in his pants."

As a young boy, Ken Mew placed first among 3,000 students in a scholarship contest to enter a prized technical institute. However, because he was from the lower classes, he was passed over and sent to a working-class school. He eventually left school to work in a variety of menial jobs, but lost one position after another as the Great Depression put a stranglehold on the economy. In 1932, he lied about his age to join the army, a career that promised three square meals a day and some pocket money. By mid-decade, he saw his first violence when he was posted to Palestine, where virtual civil war had broken out between the Arabs and Jewish settlers, with the British Army caught in the middle.

In 1939, he left the army to work for ICI, the giant British chemical company, but within a year was called up to the army when Germany invaded Poland and Britain declared war. The British Expeditionary Force was outmanoeuvred by the German Blitzkrieg through Belgium in 1940 and began retreating to Dunkirk. He was successfully evacuated from Dunkirk back to Britain, where he volunteered for a new unit, the Glider Pilot Regiment. He qualified as a pilot of one of the big, clumsy, wooden Horsa gliders that could carry 30 troops, a couple of small howitzers, or a jeep and command party.

Only five-foot-six (168 cm) but possessing the strength and skill to handle a glider that "flew like a brick," Squadron Sgt. Maj. Ken Mew was picked to carry Gen. Sir Richard Gale, the airborne troop commander, into Normandy on D-Day. Gliding in under cover of night, his wooden glider was among the first to land, but its front wheel came off and it stood up on its nose. Unable to get his jeep out, the general commandeered a French farm horse and rode into battle as Ken and the other soldiers from the glider grabbed their guns and formed a defensive perimeter. Eventually, they heard the skirl of bagpipes: Lord Lovatt and his British commandos had arrived to relieve them, a scene depicted in the classic Hollywood movie, The Longest Day.

Ken Mew would participate in two more glider actions. In late 1944, he carried troops into the area north of Nijmegen to rescue paratroopers who had been stranded in the abortive Arnhem operation. The next spring he participated in the airborne operation that took the British Army across the Rhine, an invasion in which 80 per cent of the gliders were struck by enemy fire. Ken Mew was hit in the leg, and soon after received the Distinguished Flying Cross, one of the few British Army men to receive the coveted Air Force decoration.

The fighting over, ICI was anxious to have Ken Mew back on its payroll as a technical rep. One day, after missing his train, he took another train and encountered an attractive young woman in a pixie hat who was returning home after a weekend with her boyfriend and his parents. They conversed like old friends and Ken was smitten. He found every excuse to stay close to Lilian Rice and within 24 hours had proposed.

"I thought he was quite mad," Lilian said later, but their marriage would last the rest of their lives. In 1948, they went to South Africa, where he would worked for ICI in Southern and Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) He soon found himself standing in as preacher in the school hall of one mining town and within a decade he became immersed in politics, pointing out the dangers of white-only rule. In late 1963, he was recruited as Principal of Ranche House College, where blacks were educated on an equal basis with whites. That equality was maintained even after the white government of Ian Smith decreed racial segregation in education and banned mixed-race children's sporting events.

In 1964, the Prime Minister Ian Smith had declared the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) for Southern Rhodesia and had virtually imprisoned the British Governor, Sir Humphrey Gibbs in his residence for not signing off on the declaration.

At one point, the sons of Ian Smith and black leader Abel Muzorewa would find themselves writing exams at the same time at Ranche House College. Life for the Mews and their three children could be difficult as money was always tight. The College would take just about anything as tuition payments to assist the children of black families and Jayne their daughter recalled many meals of "tuition chicken" provided by proud black parents.

Ken Mew also served as an ad hoc Methodist minister at several churches, the result of his fundamental goodness and his wife's deep Christian faith. He was not a judgmental or stuffy man. "When he laughs (which is often), his whole face is wreathed, his eyes dance with merriment, and his pipe, or his meal, or his drink goes neglected for long periods as he tells his jokes," Rowland Fothergill wrote in a 1984 biography of Mr. Mew titled Laboratory of Peace. "He especially enjoys telling jokes against himself."

The longer Smith's government stayed in power, the greater the level of violence within white-ruled Rhodesia. The Mews found themselves caught in the middle because of Ken and Lilian's efforts to broker a peace. When Mr. Mew went to Sweden to appeal for financial help for his college, he was refused because Ranche House was seen as a Rhodesian institution. As Principal of the Ranche House College, he worked tirelessly for equality between the races, convened meetings and discussion groups and led protests that also made him a hero to many in South Africa, where apartheid was still the rule and Nelson Mandela was still in prison.

Beset by trade sanctions and massive deficits, Ian Smith's government began to give way. When a place was needed for talks, Ranche House College was chosen as neutral ground and hosted the secret talks that led to a one-man, one-vote election in 1980 when Southern Rhodesia became Zimbabwe. Ken Mew was considered for one of the two cabinet positions reserved for whites, but he let Robert Mugabe know he preferred running his college.

In 1982, now 67 years old, Ken resigned his position at Ranche House School and started the Glen Forest Training Centre, where uneducated blacks could learn basic skills like animal husbandry, blacksmithing and baking. The training centre proved another success and in the same year, he was awarded the World Methodist Peace Prize for his work in promoting interracial adult education in war torn Rhodesia (Zimbabwe).

Short of ministers, the Methodist Church asked him to take on a ministry, which he did. During a visit to Edmonton where his daughter Jayne lived with her husband, Ken was offered an exchange. The minister of St. Paul's United Church would go to Zimbabwe to preach at Mr. Mew's church for a year and Mr. Mew would take over St. Paul's.

Almost penniless after a lifetime of good work in Africa, the Mews moved to Edmonton where they stayed with their family and from where over the years the local newspapers would publish letters to the editor from Ken Mew gently scolding local citizens for a lack of moral fibre, for not turning out to the polls on election day and for other shortcomings. Dismayed, he also followed Mugabe's transformation into just another African despot.

A series of health problems finally slowed him down and he died peacefully on May 23, 2008 in his 93rd year in Edmonton, Canada.

Acknowledgement

P. Jackson. Historic Buildings of Harare. Quest Publishing, Harare. 1986

jfarrell@thejournal.canwest.com. A Champion of Peace

R. Fothergill. Laboratory for Peace: The Story of Ken and Lilian Mew and of Ranche House College, Salisbury. L. Bolze. Bulawayo 1984