The part played by religion in the Mashona Rebellion (First Chimurenga) in 1896-7 as told by Terence Ranger in Revolt in Southern Rhodesia 1896-7

Both this article and the article The part played by religious factors in the 1896-7 Matabele Rebellion (Umvukela) as told by Terence Ranger in Revolt in Southern Rhodesia 1896-7 and the shooting of the Mlimo are complementary and sourced largely from Terence Ranger’s book Revolt in Southern Rhodesia 1896-7.

Some of Ranger’s conclusions came under the spotlight of David Beach and Julian Cobbing who have come to different conclusions – nevertheless I still believe that Ranger’s work based on archival material in the National Archives of Zimbabwe, and therefore it must be remembered mostly from a white perspective, has a great deal of value for present-day readers who may struggle to understand the complexities of how religion played its part in the uprisings in Matabeleland and Mashonaland in 1896 – 7.

Future articles may seek to update Ranger’s work that was really amongst the first comprehensive attempts to unravel the role of African religion in the rebellions.

White misconception of Mashona religion

Father Hartman, the Jesuit missionary in 1894 wrote, “Among the Mashonas there are only very faint traces of religion. They have hardly any idea of a supreme being...the Mashonas are united as a commonwealth by nothing except the unity of their language.”[1]

This may be because the Rozwi aristocracy (more below) scattered in the 1830’s following the Zwangendaba and amaNdebele invasions; some going north, others amongst the tribes of western and central Mashonaland, so that by the 1890’s it was difficult to find any remnants of the old Rozwi system,[2] except in their former royal residences at Khami, Danamombe (Dhlo-Dhlo) Naletale and Zinjanja.

The disruption of the Zwangendaba, and to a lesser extent the amaNdebele invasions, caused a great movement and subsequent upheaval of the people in Mashonaland causing the boundaries of the traditional paramountcy’s and the composition of their populations to undergo great change. Despite this, historians have traced the rulers of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries particularly through Portuguese written records of the Mutapa Empire and then the Rozwi confederacy[3] and were known through oral sources into the nineteenth century. Remember though, the Portuguese Catholic clergy wrote these records and always had their own agenda.

Ranger argues that many chiefdom units such as those of Barwe, Maungwe (Makoni) Manyika (Mutassa) Mbire (Soswe) and Budya (Mutoko) preserved the ancient ceremonial rituals of ‘kingship’ that were passed down from the Mutapa and Rozwi. So far from being rootless and without a sense of history, the peoples and especially the aristocracies of these paramountcy’s could relate themselves to two or three centuries of a traditionally known past through their relationship with the previous occupiers, with the dead and with the land.[4]

Perhaps some whites did understand their influence particularly after the rebellions as Native Commissioner ‘Wiri’ Edwards wrote in 1899, “The Mashona chief has never been credited with great power over his people, but although he has not had that tyrannical power of some native chiefs in other territories he has a moral power as head of his tribe which we are getting to understand better every day and he can use this power for either good or evil, just as he thinks it will suit him best.”[5]

Further misconceptions of Mashona history

Marshall Hole noted after the outbreak of the Mashona uprising, “The Mashona race has always been regarded as composed of disintegrating groups of natives, having no common organisation and owing allegiance to no single authority, cowed by a series of raids from Matabeleland into a condition of abject pusillanimity and incapable of planning any combined or pre-meditated action.”[6]

But Ranger notes, “Among the mixed peoples who spoke dialects of Shona in the 1890’s there were many who had been resident in much the same area for centuries and who had a well preserved and institutionalised memory of their history. The Shona linguistic area had been the scene of at least two remarkable attempts at political centralization - the confederacies of the Mutapas and of the Rozwi Mambos. The authority of the paramount chiefs had survived the collapse of these confederacies in most of Mashonaland.”[7]

Only later did local officials such as ‘Wiri’ Edwards, first Native Commissioner at Mrewa write, “We knew nothing of their past history, who they were or where they came from, and although many of the Native Commissioners had a working knowledge of their language, none of us really understood the people or could follow their line of thought. We were inclined to look down on them as a downtrodden race who were grateful to the white man for protection.”[8]

Mutapa Empire and the growth of a religious belief system

The Mutapa dynasty was launched in north-east Mashonaland when Shona speakers conquered the Tavara tribes of Urungwe, Sipolilo and Mrewa in the 15th Century and became known as the Korekore. The conquerors came from the area of Great Zimbabwe – they already had a well-established gold trade with Swahili merchants at the coast at Sofala. They gradually expanded their territory and turned it into “an empire over many other tribes who were allowed to keep their own chiefs but were obliged to forward tribute. In exchange the king’s subjects received protection from their enemies, as well as gifts, the royal court perhaps acted as the centre of a vast system of tributary exchange which functioned without money…”[9]

The Mutapa’s power was partly economic, partly spiritual. Fagan[10] says, “Everything points to the power of the Shona and Rozwi chiefs having been based on their intermediary powers or on their control of the powerful mhondoro (tribal spirits) upon whose messages to Mwari depended on the fortune of the community.”

Ranger adds, “The Mutapa was surrounded by ritual and prohibitions, the dead Mutapas were honoured at the great royal graves, tended by their own posthumous court. And the rites which surrounded the Mutapa were emulated by the rulers of the provinces or the principalities of his empire.”[11]

Although the Mutapa Empire had dwindled by the nineteenth century to the Tavara, a small area west of Tete, the religious system which had been associated with it was still influential and the spirits of the dead Mutapas continued to command respect amongst the Mashona tribes.

In the 1870’s - 80’s Goanese traders and their mixed race offspring named still based themselves at the kraals of the paramount just as centuries before the Arab and Swahili traders had based themselves at the Mutapa’s court with their agents or vashambadzi going out to the kraals of the various headmen and trading for gold with cloth, beads and above all, guns.

Kuper writes, “the Shona have an elaborate cult, unusual in southern Africa, centring in the Supreme Being, Mwari” but by the nineteenth century the Shona people had two elaborate religious systems centering on Mwari.

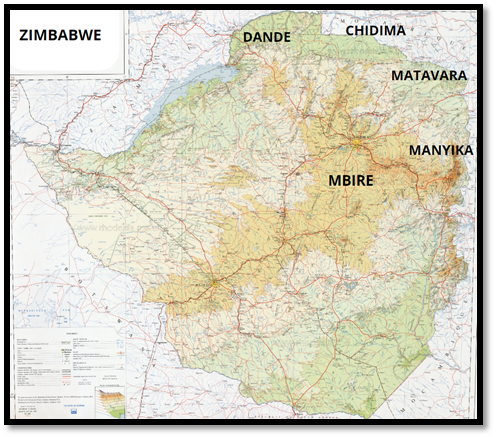

After Ranger P42 – Mutapa Empire Provinces within present-day Zimbabwe at its maximum, Barwe, Uteve and Madanda in Mozambique excluded

In 1890 the memory of the Rozwi confederacy still remained

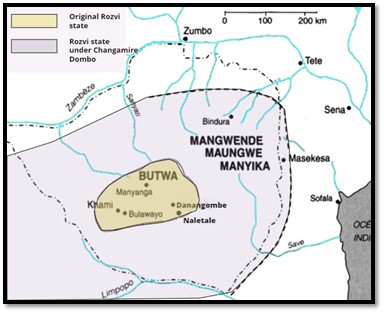

Although the Rozwi confederacy had fallen after a series of invasions in the 1830’s by migrating Nguni groups[12] migrating from present-day South Africa northwards due to the Mfecane there were still Shona elders alive in 1896 and the centres of resistance to the whites was those areas where the Rozwi Changamire confederacy had taken control from the weakened Mutapas in the second half of the 16th Century.

F.C. Selous[13] in 1893 drew a picture of how he imagined central Mashonaland fifty years previously, “the peaceful people inhabiting this part of Africa must have been at the zenith of their prosperity. Herds of their small but beautiful cattle lowed in every valley and their rich and fertile country doubtless afforded them an abundance of vegetable food.” The Shona paramount’s were then, “rulers of large and prosperous tribes… whose towns were for the most part surrounded by well-built and loopholed stone walls…hundreds of thousands of acres which now lie fallow must then have been under cultivation…while the sites of ancient villages are very numerous all over the open downs.”

From Summers: The Rozwi Empire superimposed over a present-day map

Changamire Dombo attacked Tete and Sena in 1693 and Sofala in 1695 in brief raids. The main Rozwi centres were at Danamombe (Danangombe, formerly Dhlo Dhlo) Naletale, Zinjanja and Manyanga (Ntaba zika Mambo) but, “by the 1890’s it was difficult to find any material traces of the old Rozwi system, always excepting the now ruined and deserted zimbabwe’s.”[14]

Native Commissioner Weale[15] asked the rhetorical question, “How many people know who the Rozwi are, or where they live and what influence they exert in the land over which they once ruled supreme?” But clearly the question was appropriate to whites, but not the Shona, who in the 1890’s and later remembered very clearly the Rozwi supremacy and their supernatural powers.

Ranger records that some Shona paramountcy’s can be traced back to the 16th and 17th Centuries when they were named by Portuguese sources, others were founded during the Mutapa or later Rozwi periods, still others were set up by later conquest in various areas such as the Maungwe paramountcy under the Makoni, or the Mutassa paramountcy in Manyika.

Once founded they became the main units of the Shona political systems. Barwe, Maungwe, Manyika, Mbire under chief Soswe, Nhowe under chief Mangwende, Boca under chief Marange, Budya under chief Mutoko.

Whites were mistaken as they generally thought the chiefs possessed no real powers, but in their succession were still included the ceremonial rituals, in a less elaborate form, of the Mutapas and the same hereditary officers responsible for ceremonial functions and in many ways showed what Professor Oliver calls, “vestigial traces of a strongly centralized political structure.”

So in fact, the Shona paramountcy’s thought of as powerless by the whites could relate back two or three centuries into the past and, “exercised a profound, extensive, and subtle influence through their relationship with the previous occupiers, with the dead, and with the land.”[16]

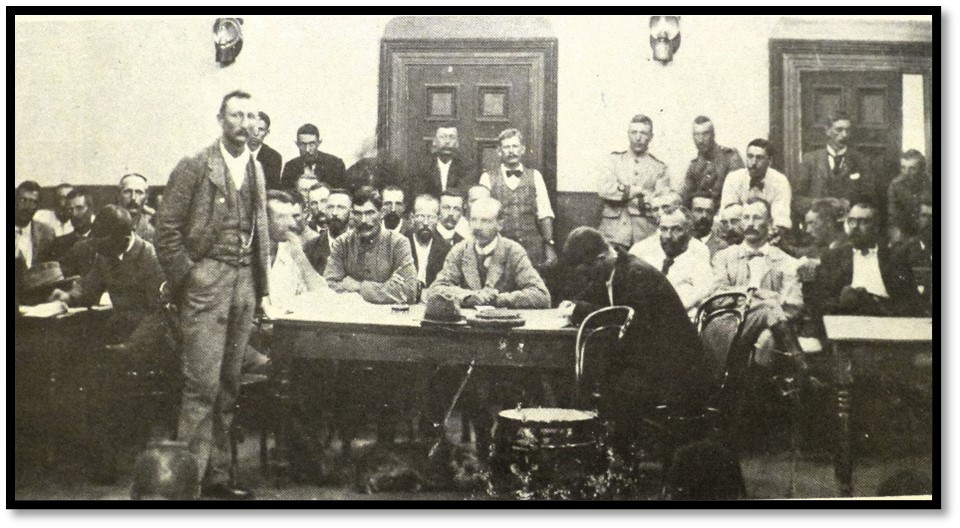

NAZ: AmaNdebele leaders gather in Bulawayo after the conclusion of peace 1896

The Shona resistance to foreign influence

Ranger argues that far from being meekly prepared to succumb to colonial pressures the Mashona had been putting up ‘a resolute and successful resistance to them over centuries.’ Portuguese power pressed onto the Mutapa Empire in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries but was swept away by the Rozwi in 1694 and 1702.[17] A Jesuit historian described the fate of Portuguese missionary work, “What was the result of these hundred years of devoted effort? Almost nothing.”[18]

In the 1890’s a stubborn resistance was put up. Missionary efforts, “were slow and painful.” In 1892–5 the Roman Catholic mission at Chishawasha could record only two baptisms. FR Rea, S.J. wrote in 1897, “It shows at all events that they have but little willingness to become Christians…it was a manifestation of loyalty to their own concepts of society and the divine; a steady passive resistance which was to turn in 1896 into an armed attack upon the missions and their few converts as well as upon all other whites.”

The white myth that the Shona were grateful to be freed from the tyranny of the amaNdebele

This myth was widespread. Jameson wrote when the Pioneer column reached Chibi’s country, “how delighted these unfortunate Banyai are to welcome the coming in of the white men in force sufficient to put an end to all this murder and slave raiding.” Selous wrote there were entire tracts of country absolutely depopulated by the amaNdebele and even where people remained they were so impoverished by the amaNdebele impis that the latter no longer thought it worthwhile to make further excursions to the northeast.

In 1892 Fr Hartmann, S.J. wrote, “if no stop is put to these raids it will go on until the Mashona are exterminated…The Mashonas are a complete wreck physically, intellectually and also morally. In my constant intercourse with them, I hear it oftentimes said that if the white men do not protect them, they will emigrate from the country.”

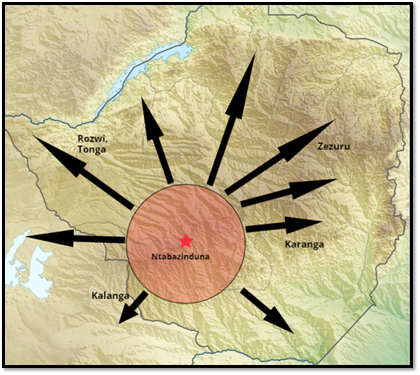

There certainly were destructive and cruel raids by the amaNdebele on the Mashona and their prosperity and security was severely reduced, but they were not almost wiped out, or became totally demoralized. Those within the raiding areas of the amaNdebele impi’s were exposed to their raiding and extraction of tribute – the Kalanga of south-west Matabeleland, the Karanga around Fort Victoria (Masvingo) the Zezuru of Hartley and Charter and Lomagundi (Makonde) the Rozwi, Tonga and others north of Inyati.

Ranger writes the Tonga chief Pashu stated, “while under Mzilikazi’s rule they were continually carried off, yet after Lobengula’s accession he was left unmolested so long as he paid his tribute of skins, feathers, etc., to the King”[19] and even if a chief refused to pay tribute the punishment was not necessarily arbitrary and wholesale. When Chief Lomagundi refused to pay tribute or acknowledge Lobengula’s supremacy, a small impi was sent to his kraal in 1891, its commander first visited the senior spirit medium and obtained her permission to punish the chief, then his kraal was attacked, and the chief and his closest councillors killed.

The amaNdebele made no attempt to re-model Mashona political or religious institutions in the tributary areas, but rather entered into varying relationships with the Mashona paramount’s and spirit mediums.

Ranger writes that outside the ring of tributary territories that had some sort of relationship with the amaNdebele they continued to make periodic raids for loot. An amaNdebele warrior stated, “These people all cleared into the granite ranges and hills to build their strongholds and kept a keen watch on our movements. They also developed a sort of code of call and ways of sounding their drums and sent messengers to keep one another informed of our every movement. So it became very difficult to take them by surprise as time went on.”

One of those who should have been a complete wreck was Chief Kunzwi-Nyandoro, “yet Kunzwi-Nyandoro, in his stronghold[20] and on his guard, retained all the attitudes and pride of a Shona paramount, exerting a powerful authority over his people, respecting the spiritual eminence of the Dzivaguru and Chaminuka mediums and savouring his independence above everything.”[21]

Another wide-spread myth was that the amaNdebele ruled Mashonaland

Colquhoun, the first administrator and Lt-Col Pennefather, the head of the chartered company’s police were told that the British South Africa (B.S.A.) Company’s claim to Mashonaland depended upon the Rudd concession and that Lobengula’s effective sovereignty extended throughout Mashonaland. But once in Mashonaland they realised this was untrue. Colquhoun wrote in 1891, “Lobengula’s claims…I have understood to extend at least as far east as the Sabi River. I consider, however, that if any inquiry was made on the spot, this claim would be most difficult to establish and it would be undesirable to have the question raised…Between the Sabi and the Ruzarwe (Ruzawi) rivers there are chiefs who acknowledge no one’s authority. They have certainly never been under Matabele authority, nor have they ever seen any Matabele…Selous has maintained, and maintains as you know, that (a) east of Sabi and (b) north and east of the Hunyani the Matabele had no real claim whatever, and that such claims would not stand investigation.”

Lt-Col Pennefather came to a similar conclusion, “After making personal acquaintance with the country and the natives. I'm strongly of the opinion that Lobengula's impi’s have not raided further than 30° east.”

In October 1891 Colquhoun sent Selous to make treaties with independent Shona chiefs to consolidate the chartered company’s title. Selous wrote satirically that he was, “off to get mineral concessions and come to a friendly understanding with several native chiefs living to the south and east of furthest Mashonaland of whom neither Lo Bengoola, nor Dr Harris, nor Dr Jameson have ever yet heard.”[22]

The chiefs included Makoni of Maungwe, Soswe of Mbire, Mtoko of Budya and Marange of Boca. Other treaties were made with Mangwende of Nhowe and Mutassa of Manyika. Although not under pressure from the amaNdebele, the Portuguese under the Goanese Gouveia from Gorongoza were attempting to exert influence over them. Like the Shona elsewhere they had abandoned their kraals in the valleys for strongholds in the granite hills defended by stone walls and deep caves. But there was no question of their being exterminated by the amaNdebele without the B.S.A. Company’s white protection or being forced to leave their paramountcy’s and they were prepared to defend these strongholds with firearms that were becoming increasingly common throughout Mashonaland.

This does not mean the Shona chiefs were united in any way. In May 1892, Captain Lendy left Salisbury with a police patrol to visit the chiefs of the Salisbury district and his report shows the disunity between them. Chief Chishawasha complained against Chief Kunzwe-Nyandoro for a pre-1890 assault. Chief Marondera and Chief Chiduku alleged raids and counter-raids against each other. Chief Mbelewa lived in constant fear of being raided by Chief Makoni.

The area of amaNdebele settlement was quite compact as the diagram below shows and covered a much smaller area than the Mutapa Empire, or the Rozwi confederacy. Outside their own area the amaNdebele did not attempt to build up societies in the amaNdebele pattern. This was contrary to what many whites believed in the 1890’s that the amaNdebele raids on the Mashona people depopulated many parts of their territories and undermined their society.

Map adapted from Bulawayo, Historic Battleground of Rhodesia showing amaNdebele settlement around Ntabazinduna and the directions of their regular raiding parties

Some Mashona chiefs joined the rebellion others collaborated with the whites

As in the Matabele Rebellion (Umvukela) some Mashona chiefs had benefited with white rule; either their political power was placed on a more secure footing, or sales of grain and cattle to the whites had increased their wealth and therefore they did not wish to challenge white rule. Others, involved in rivalries with other chiefs and committed to safeguarding their interests stayed neutral, whilst others did put their differences aside and joined the uprising. Beach has argued that Shona chiefs had combined in political alliances in the past and would do so again in 1896.[23]

The Mashona custom of rotating the chieftainship gave rise to some family feuds and rivalries. For instance Chief Chingaira Makoni of Maungwe was opposed by Ndapfunya, son of a former chief. In addition, a sub-Chief Chipunza attempted to assert his independence during the uprising. Old rivalries meant one paramount would stay out of the rising because another had committed. Whilst Makoni was active in the uprising, Mutassa of Manyika, an old enemy, sent warriors to assist Alderson’s force in their attack on Makoni’s kraal at Gwindingwi.

Tension also rose between the generations. Most of the Shona paramount’s were middle-aged or elderly and were challenged by younger members who were more radically committed. Chief Mangwende of Nhowe was challenged by his son Mchemwa, Chief Makoni faced the same problem with his son Mhiripiri, and even Chief Mutasa’s neutrality was challenged by his son.

Ranger also cites Richard Werbner who carried out field work with the Kalanga of western Matabeleland and argues the Mwari cult never co-existed with any state or polity, including the Rozwi and amaNdebele states in the colonial period. It had no political interests or concern with the survival of one state rather than another. Its concern was its own internal politics, the system of tribute and redistribution and its ideology was linked to agricultural production only. Moreover, its organisational structure was scattered between the four main shrines at Njelele, Matonjeni, Umkombo and Manyanga (Ntaba zika Mambo) and other subsidiary shrines and “did not lend itself to the mobilization of people for war.”

“Beach maintains that the Shona spirit mediums had much less extensive areas of influence than I supposed. Cobbing has denied that the Mwari cult played any significant role in the risings at all or that it exercised any influence over the Ndebele.”[24]

Whites were completely taken by surprise at the Mashona uprising

Marshall Hole wrote on 30 March 1896, “I may remark that this sudden departure on the part of the Mashona tribes has caused the greatest surprise to those who, from long residence in the country thought they understood the character of these savages and to none more than to the Native Commissioners themselves. With true native deceit they have beguiled us into the idea that they were content with our administration of the country and wanted nothing more than to work for us and trade with us and become civilised; but at a given signal they have cast aside all pretence and simultaneously set in motion the whole of the machinery which they have been preparing.”[25]

The role of the spirit mediums in the Mashona Rebellion (First Chimurenga)

Spirit mediums were the bridge (i.e. they communicated) between the living people and the spirits of the dead and they had another role as protectors of the land and the people.

A Manyika counsellor told JV Taylor, “In ancient days, all things were there. For there it was that heaven and earth were wont to meet. Every year we used to gather there, we the creatures of the earth, and they, the elders who led the way over the river in between which divides the creator from his creatures.”[26]

The spirit medium would be a man or woman believed to be regularly possessed by an important ancestor spirit and when in a trance, a medium spoke with the voice of the ancestor becoming, in essence, the ancestor and in this way the living and the dead could literally communicate. The living would approach the dead for advice or to intercede on behalf of the people. The dead could tell the living of their past and something of the world outside life.

These claims by the spirit mediums were widely regarded by whites in the 1890’s as fraudulent, but in more recent times the mediums have impressed those who studied them with their sense of vocation and service to the traditional values of Mashona society.

In the 17th Century spirit mediums were closely associated with the Mutapas. They voiced themselves as ancestors of the king himself, or the original owners of the land, or rain-makers[27] and maintained contact with the dead kings on behalf of the nation. The reigning king would visit the royal graves before any major plan and after the Mutapa decline when the royal graves had disappeared, the spirit mediums continued to be the chief’s representative.

The mediums of the Mutapa system become replicated at a local level in the Mashona paramountcy’s

Ranger writes the founder of a paramountcy usually became the senior spirit in the area and his medium became the senior spirit medium. Other significant ancestors would also have mediums. However D.P. Abraham in addition to the upper level of ‘supra-tribal’ mediums also defined a local category of mediums and rain-makers at a tribal level.

“This double hierarchy of spirits and mediums survived the collapse of the Mutapa dynasty so that, long after the secular Mutapa had been confined to his Tavara enclave, the mediums of important Mutapas of the past, or of spirits like Dzivaguru or Chaminuka, were still powerful in wide areas of east, central and western Mashonaland.”[28]

Spirit mediums in Mashonaland continue to play an important political as well as ritual role

This dual role had been important under the Mutapas in the 16th and 17th centuries. Ranger states they at once guaranteed and limited the power of the Mutapa kings; in the 19th century they continued in this role with the chiefs with the senior paramountcy mediums continually involved in tribal politics.

Above them are the great mediums of Mutota, Chingoo, Dzivaguru, Chaminuka and Nehanda who are respected over wide areas of Mashonaland and “the nearest thing to a national focus that the Shona of Mashonaland possessed.”

NAZ: amaNdebele chiefs on trial. Standing W.E. Thomas, Seated (L-R) Herbert J. Taylor, Arthur Lawley, Johan Colenbrander (in white suit) R. Townsend

Portuguese efforts at converting the Mutapa to Christianity were frustrated

As the Mutapa Empire was establishing itself, so Portuguese seafarers were laying the foundation of one of the world’s great maritime empires that started with Prince Henry the Navigator and his attempts to cut the Muslim trans-Saharan gold trade and establish a sea route to India and the rich spice trade. In 1488 Bartolomeu Diaz had rounded the Cape and that achievement was extended when Vasco da Gama set out in 1497 with four little vessels and on 20 May 1898 reached Calicut, a centre of the Indian spice trade.

Portugal was determined to extend Catholicism and these missionary ambitions went hand in hand with their political and economic aims. Gold was necessary to buy Indian spices, the gold trade between the Mutapa and Swahili traders on the east coast of Africa was supposed to be of fabulous value and in 1505 the Portuguese seized Sofala below present-day Beira.[29] By 1507 they had crushed a Muslim fleet off Diu and gained naval supremacy in the Indian Ocean.

Sometime between 1511 – 12 a Portuguese ship’s carpenter and degredado[30] was sent to explore the interior and in a remarkable journey, Antonio Fernandes[31] covered a wide area of the African interior and dictated on his return an account of his travels having reached ‘Embire,’ which is, “a fortress of the king of Monomotapa, which he is now making of stone without mortar which is called Camanhaya and where he always is…And from there onwards they enter into the Kingdom of Monomotapa which is the source of the gold of all this land. And the latter is the chief king of all these. And all obey him from Monomotapa to Sofala.”[32]

The Portuguese decided to follow up Fernandes’ success by sending Father Gonçalo da Silveira, a Portuguese Jesuit to the court of the young Mutapa King Nogomo Mupunzagutu near the west bank of the Utete river. Initial signs were good, the king and his court accepted baptism, but the resident Swahili traders feared Christian penetration threatened their livelihoods and persuaded the king that the Portuguese were bent on stealing his kingdom and in 1561 he had Silveira strangled.

By 1693 the Rozwi under Changamire Dombo had destroyed the Portuguese feiras and forced the departure of the Portuguese traders and their vashambadzi offspring from the northern Mashonaland plateau. A Portuguese chronicler wrote, “What was the end result of all the Portuguese missionary effort? Almost nothing. It was one of the most complete failures of missionary history.”[33]

“In the 1890’s the same stubborn resistance was being put up; everywhere in Mashonaland missionary beginnings were slow and painful; in three year’s work prior to the rising the Roman Catholic mission at Chishawasha could record only two baptisms and their experience was common to all. A closer acquaintance with the Mashonas, confessed a Jesuit missionary in 1897, shows at all events that they have but little willingness to become Christians.”[34]

Father Rea put it down to, “loyalty to their own concepts of society and the Divine; a steady passive resistance which was to turn in 1896 into an armed attack upon the missions and their few converts as well as upon all other whites.”[35]

Why events in Mashonaland and Matabeleland from 1890 to the uprising were so different from colonialism in East and Central Africa

In most parts of Africa that were colonised the interiors remained largely undeveloped with little infrastructure and largely served as reservoirs of labour for the coastal areas as the commercial companies and government administrations had little capital and few resources. However the scale of the Pioneer Column of 1890, the invasion of Matabeleland in 1893 and the administration set up by the British South Africa Company were unprecedented elsewhere in Africa.

If the Shona paramountcy’s initially regarded the Pioneer settlers as representatives of a large trading company that would soon leave they were quickly disillusioned by the prospectors, farmers and traders that entered along with the British South Africa Company administration and they soon realised they faced a far greater challenge.

Inevitably this set the scene for a clash between the two communities – amaNdebele and Mashona on the one hand, with the white settlers on the other, to defend their respective ‘ways of life.’ Ranger quotes Sir Richard Martin[36] calling, “for the establishment of a strong and able Native administration and one which should have considered the conciliation and welfare of the Natives as the all-important object to aim at.” Lord Grey, the Administrator, said to Rhodes in 1891 that, “objectionable German methods must be avoided in Central Africa and that the chiefs must be persuaded that the Queen has spread her wing over the country, not for the purpose of crushing them but with the view of helping the chiefs in the difficult work of self-protection and development.”[37]

Rhodes set the policies of the early British South Africa Company (BSAC) administration

Ranger declares that after 1893 Rhodes did not consider the amaNdebele a factor which required his attention and that the Shona were almost completely disregarded. Once Mashonaland was occupied and Matabeleland conquered, Rhodes seemed to feel there was no need for a continuous native policy or native administration. Official Native Commissioners were only appointed at the end of 1894 as administration was required for the collection of hut tax.

Rhodes’ alter ego, Jameson, said, “should the occasion present itself, or the emergency arise, to ride rough-shod over forms or amenities and rules or regulations” and it was precisely for this quality in Jameson that Rhodes insisted that he be made administrator in place of the first appointee, Colquhoun.[38]

Ranger writes, “With Colquhoun’s departure any chance of the erection of a regular and satisfactory administrative system in Rhodesia was lost” and quotes Alfred Milner’s[39] description of Rhodes as a gambler and describes his failure to build up a Native Department to control and conciliate the African peoples of Rhodesia as an unsuccessful gamble for which the price was paid during the uprising of 1896–7.

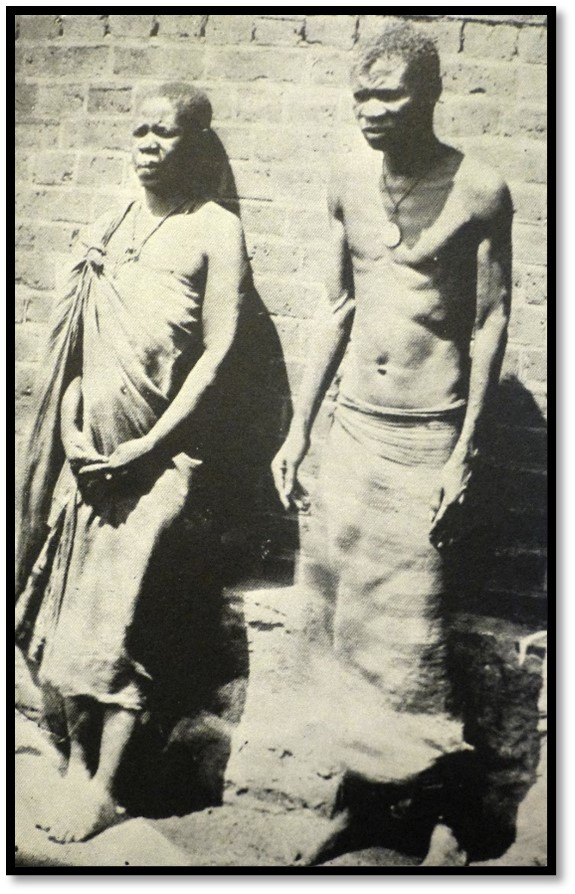

NAZ: the Norton farm after their mass murder

The organisation of the Mashona Rebellion is a mystery to whites

Much of the existing literature focuses on the surprise the whites experienced when it became apparent that they were in the midst of a rebellion. Grey wrote despondently to his wife on 3 July 1896, “It was as you can imagine a profound disappointment this Mashonaland rising. We were nearing the end here [in Matabeleland] and I was looking forward so much to meeting you…at Salisbury. No one who knew the Mashonas ever expected them to rise, and even if they did, they thought that fifty men would be able to march through the country and put things down.”[40] Yet the Mashonas were fighting as fiercely as the amaNdebele and Salisbury (Harare) became cut off from Umtali (Mutare) until the imperial column under Alderson[41] could be landed at Beira and clear the road.

We have already seen that many myths were being peddled amongst the white settlers; in addition there was scant knowledge of Mashona history and the resilience they had shown in the face of 16 – 17th century attempts by the Portuguese to encroach on the northern Mashonaland plateau.

Action from within the Mashona paramountcy’s was robust and between them was quite effective. However the military discipline and regimental traditions present in amaNdebele society that resulted in the battles on the Umgusa river and siege of Bulawayo in Matabeleland[42] were not present in Mashonaland. There were small sieges at Mazoe, Hartley and Abercorn[43] but no pitched battles and Salisbury was never threatened. The set-piece fights were when the paramountcy’s were forced to defend their kopje strongholds as at Mashayamombe, Makoni and Kunzwi’s kraals – all are described on the website.

Religion’s key role in the Mashona Rebellion

Observers were astonished by the co-ordinated outbreak of the uprising and later in the response to peace proposals made by the Chartered Company’s administration. There was no co-ordinating council of chiefs or anything like it; the co-ordination came from the traditional Mashona religious authorities who also gained the wholesale commitment of the people that went way beyond any loyalty to their chiefs.

The role of the Mwari cult

We have already seen that the influence of the Mwari cult shrines spread far beyond their local areas. The influence of the Njelele shrine was felt, at times, even in present-day Mozambique. That of the Matonjeni cult shrine was powerful in the Shona areas of Belingwe, Chibi, Gutu and Ndanga. Mkwati the shrine leader at Ntaba zika Mambo appealed to the Shona in the north eastern and western parts of Mashonaland. Mwari messengers travelled to Charter, Chibi, Gutu, Hartley, Ndanga and Victoria areas of Mashonaland.[44]

This does not mean there was organised cult activity in these areas; but that the surviving prestige of the Mwari cult extended into those areas. Thus, the Native Commissioner at Makoni reported in 1894 that the people spoke, “of the WaRosi…as God's chosen people and have great respect for them, the VaRosi being looked upon as priests.” Even at Umtali in Manicaland the Native Commissioner reported, “They worship a supreme being known as Murimo, Mali or Murunga. They believe he is omni-present but that he speaks to them from only from one place, viz Matjamahopli near Bulawayo, and then he will speak only to a chosen few.”

Both the Mwari cult and the spirit mediums were deeply involved in the Mashona uprising. The well-organised existence of the Mwari cult in western Mashonaland gave Mkwati at Ntaba zika Mambo a great opportunity to link up his activities there with the rising in Matabeleland.

The Mwari cult in western Mashonaland

Ranger writes the Mwari representative there was Bonda, who worked so closely with Mkwati, that Marshall Hole believed they were the same person. Bonda was a Rozwi headman living in the Range-Charter district, later described as the “nursery of the Mashona rebellion.” Bonda was summoned to Ntaba zika Mambo in May 1896 along with some of chief Mashayamombe’s followers. He was questioned by the Hartley Native Commissioner Mooney[45] about this who wrote in his report, “I hear from one of my spies that Mashayingombi himself is in communication with someone in Matabeleland and has lately sent some young men down. I taxed Mashayingombi with this but he informed me that he had only sent to the Matabele Umlimo for some medicines to prevent the locusts from eating his crops next year. This spy also told me that it had been proposed by the Matabele and Maholi inhabitants to rise and first kill all my police…and then try Hartley…I attach no importance whatsoever to the above...”[46]

Bonda returned with Mashayamombe’s followers and Tshiwa and they brought with them members of the Mangoba regiment to incite the Mashonas into rebellion and Mashayamombe’s kraal became the centre of the rebellion in western Mashonaland. We get an idea of Tshiwa’ s influence from Native Commissioner Weale’s report, “I sent messengers out into Ndema’s country to spy out the land and the police boys brought back word to say that the whole of the country ahead was disaffected and that a Mondoro (sic) of the Mlimo, a MaRozwi named Tshiwa was doctoring the rivers so that the white man and his horse’s feet would burn up when they stepped into the water, and stated that he had arranged it that our bullets would be as harmless as water, but what was more to the point was that they had distributed among them some Matabele braves to help and urge them on to fight.”[47]

Bonda had returned to his own kraal with six amaNdebele[48] and then sent out men as messengers of Mwari to carry instructions to the smaller kraals in the area while he visited the kraals of Chiefs Umtigesa, Meromo and Msango. A witness said, “From there they went to Meromo’s, when they came there, they said they were sent by Umlimo and they were the Umlimo’s people. Meromo said he also was one of Umlimo’s people; he joined hands with them.”[49]

Bonda’s importance did not diminish when the Mashona rebellion began, he carried messages from Mashayamombe’s kraal to the south and east, led impi’s on raids to loyalist chiefs and played a significant part in keeping Mashonaland mobilized during the rising.

The links between Mkwati at Ntaba zika Mambo and the western Mashonaland remained strong throughout the rebellion.

General overview of the spirit medium hierarchy in Mashonaland

Professor Michael Gelfand[50] believed there were two distinct hierarchies of Mashona spirit mediums:

A Mutota-Dzivaguru hierarchy in the north-east and east of Mashonaland

This was the dominant area of the Mutapa Empire inhabited predominately by the Korekore and Tavara people and did not play a big part in the 1896 uprising probably because the BSAC administration and tax collection was virtually non-existent in 1896 in this area. This does not mean the spirit mediums were not capable of raising resistance; they did so in 1900 during the Mapondera rebellion[51] but did not do so in 1896.

Chaminuka-Nehanda hierarchy of central and western Mashonaland

These areas were very much involved in the uprising and Ranger explores the extent the spirit mediums were involved. He believed that no senior spirit medium took overall control of the area and they did not all unanimously support the uprising. For instance, Paramount Kunzwi-Nyandoro’s tribal medium Ganyere did not support an uprising, but the chief decided to follow the Nehanda medium.

Before the uprising, the Nehanda medium’s influence was not considered significant. The Native Commissioner Salisbury, wrote in June 1896, “Great belief was also formerly placed in the Mandoras or Lion Gods. and especially in one called Nianda (sic) but as Mr Selous puts it, since the arrival of the white man the Mashonas have lost belief in their Mandoras and the Mandoras have lost belief in themselves.”[52]

But in 1898 the same official had a very different opinion. “Nianda has been constantly spoken of in my hearing ever since I came to Mashonaland in 1890 by the Mashonas. At the present moment Nianda is the most powerful wizard in Mashonaland and has the power of ordering all the people who rose lately and her orders would in every case be obeyed.”

Nehanda was responsible for the death of Native Commissioner Pollard of the Mazoe (Mazowe) area. Gutsa testified in January 1898…I was a native messenger. I went with Pollard to the M’Kori Kori. While there we heard of the God. Then we went to Chipadza; there they fired at us. We then went to Jeta and there they fired at us. Pollard gave us money to buy sweet potatoes and as we returned, a lot of boys came with us. Gwazi was told to catch hold of Pollard. I was told to hold his hand so that he should not hurt us with his gun. So they took him to Nianda...She said, “bring him here.” Then she came and knelt down and spoke with Pollard, but we constables were surrounded in the middle. I heard Nianda say to Wata, “Kill Pollard but take him some way off to the river or he will stink.” So they took him off. We were there still surrounded close to him. Wata said “Nianda sent me.” Then he took his axe and chopped him behind the head.

Encouraged that they would not be harmed the people of Mazowe and Chiweshe rose against the whites and obeyed her orders by taking all the captured goods to her kraal just as they were in Matabeleland when all such goods were carried to Mkwati’s cave at Ntaba zika Mambo.[53]

How did the spirit mediums of central and western Mashonaland co-ordinate in June 1896?

The Mwari cult of central and western Mashonaland overlapped in the Hartley and Charter districts ‘the nursery of the Mashona rising’ and allowed them to keep in touch through messengers who carried communications between the chiefs. Chief Mashayamombe was in touch with Mkwati at Ntaba zika Mambo, but also had his own tribal medium, his half-brother Dekwende, and other chiefs also had spirit mediums at the tribal level.

Historically the great mediums of Chaminuka had their kraal at Chitungwiza and this was deliberately destroyed by the amaNdebele under Lobengula who wished to break the power of Chaminuka. But it remained a sacred place of Shona religious belief. In 1896 however there does not appear to have been one great Chaminuka spirit, informants said, “After his death he had no particular medium and was everywhere.”[54]

Other Chaminuka mediums were active including the Goronga medium in Lomagundi district and the VaChikare medium in the Hartley district who fled in the last stages of the rising to join Goronga. Ranger states this clearly implies the commitment of the Chaminuka spirit to the uprising. Ranger quotes Bullock who states that Chaminuka, VaChikare, Goronga and Nehanda were part of a ‘spiritual brotherhood’ and that they all remained in touch with one another. There was a working alliance between the Mwari cult officers of north-eastern Matabeleland, western and central Mashonaland. This alliance was confirmed by Gumboreshumba who the BSAC administration thought was responsible for the rising. At his trial in 1897 he said, “I want Nehanda, Goronga and Wamponga brought in. They started the rebellion.”

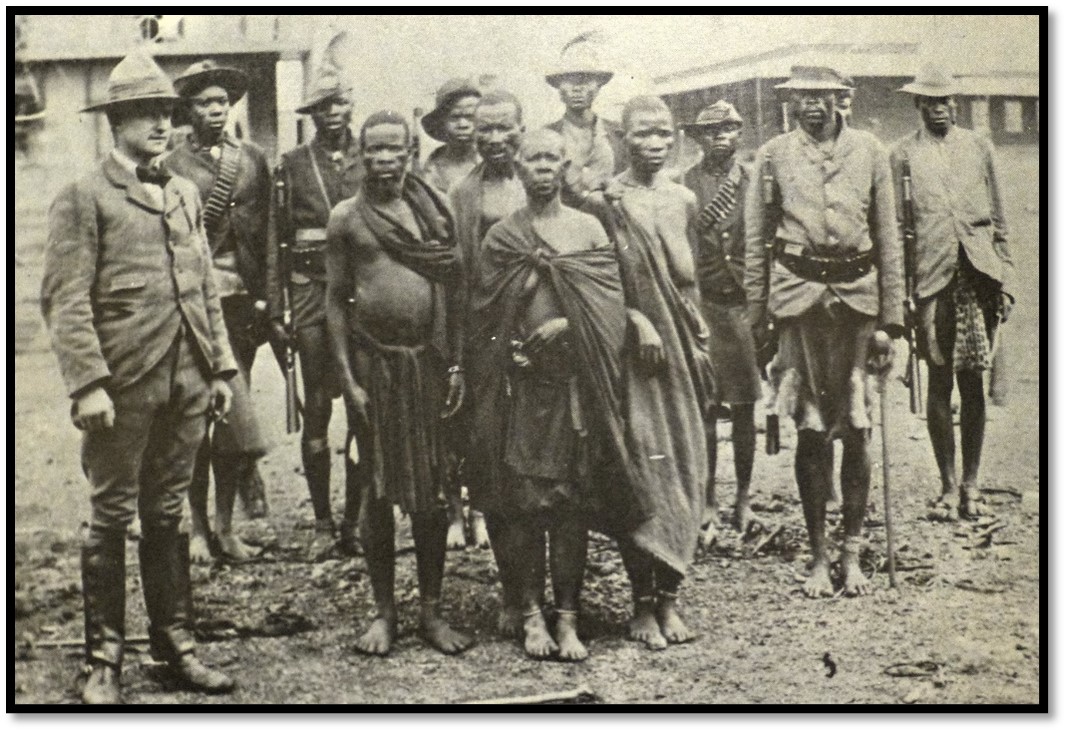

NAZ: the Nehanda and Kaguvi spirit mediums in Salisbury prison awaiting execution, 1898

Background to the spirit medium system

Ranger makes the following general points:

- The Mwari cult and spirit mediums were long established and associated with great political systems of the past, namely the Mutapa Empire and the Rozwi confederacy

- The spirit medium system was hierarchical

- It looked to the past, but gave scope for the emergence of figures with supernatural gifts and with new injunctions and commands

- It involved traditional religious officers and structures which was used in 1896 but the system was open to change, processes were not static and fixed, nor were relationships between religious officers and spirit mediums

- The individual spirit mediums were linked up with supra-natural or tribal political systems, but still retained their essential charismatic character.

From out of the Mwari cult and the spirit mediums there emerged charismatic prophet figures whose personality was capable of creating new ideologies within the cults. Ranger believed that the rise and fall of such personalities was a constant theme within Shona political history, sometimes representing a challenge to established political powers, sometimes acting as a rallying point in a period of political breakdown.

He states the situation in 1896 was conducive for the emergence of a charismatic prophet figure such a Kaguvi.[55] What was being called for was the total overthrow of the white community and that required an uprising to be organised secretly and to provide those carrying it out with a vision of what would be achieved.

The Mwari cult could provide co-ordination and inspiration, but in addition it offered:

- An area of influence far wider than any secular authority in what was a very fragmented Shona society

- It appealed to both the past histories of amaNdebele and Mashona societies

Mkwati

In Matabeleland Mkwati provided the leadership required to turn the “traditional religious systems into something more radical and revolutionary.”[56] He had no claim to being a senior Mwari official, he was initially just a messenger, and was an ex-Leya slave, not even a Rozwi descendant, but just before the Matabeleland uprising managed to emerge as ‘the great Mlimo.’

He achieved this with his revolutionary message and set of instructions. His followers were promised they were invulnerable to the white’s Martini-Henry bullets and his message appealed both to the amaNdebele and Rozwi communities. His authority became elevated beyond that of the Indunas and Chiefs as he sought to create a ‘new order.’ His opponents then were the traditional officials of the Mwari cult, particularly at the Umkombo shrine in south-western Matabeleland and those in the old political order.

Kaguvi or Kagubi whose Shona name was Gumboreshumba

Ranger writes he is unaware of any references to the Kaguvi spirit or its medium before 1896, whilst there are many references to Nehanda and Chaminuka – it seems that his influence only developed in association with the rebellion movement.

Herbert Taylor, the Chief Native Commissioner wrote, “Prior to the rebellion Kagubi was a common Mhondoro (one who purports and is believed to be possessed of a spirit) He resided in the Salisbury district[57] and was believed by the natives to be possessed of the supernatural power of locating and enabling people to capture game…Immediately previous to the present rebellion Kaguvi betook himself to the Hartley Hills and immediately became the most prominent Mhondoro in connection with the rebellion. As Kagubi was, previous to the rebellion, only a common Mhondoro, and as his great scheme (the rebellion) failed, I do not think anyone will arise purporting to have received his supernatural powers. With Nianda [Nehanda Nyakasikana] it is different. Previous to the rebellion she was by far the most important wizard in Mashonaland and was in the habit of receiving tribute from all the chiefs who took part in the rebellion.”[58]

Ranger thought it was unlikely if a complete account of how the Kaguvi medium came to fill such a central role would ever be possible, but makes the following points:

- The system of spirit mediums allowed for reversals of influence and for the emergence of new prophets

- Spirit mediums were respected because of a long line of prior powerful spirits, partly because of their own spiritual gifts

- New manifestations of spirit mediums have appeared regularly in the past.

Kaguvi emerged in 1896 as the Mashonaland equivalent of Mkwati and was elevated to a position above the existing Paramount’s and above Nehanda and her relationship with the Chaminuka hierarchy and provided a centralising figure for the Mashona Rebellion.

NAZ: Spirit mediums Kaguvi and Nehanda under guard after their surrender in October 1897

An outline of Kaguvi’s involvement in the uprising

As a liaison between the Mashona districts, Kaguvi was a good choice. He had operated in the years before the uprising at Chief Chikwakwa’s kraal, was Chief Mashonganyika’s son-in-law and was regularly consulted by Chief Kunzwi Nyandoro.

In April 1896, soon after the Matabele Rebellion had begun, Mkwati had contacted Chief Mashayamombe offering assistance for an uprising in Mashonaland. When the chief’s messengers accompanied Tshiwa and Bonda to Ntaba zika Mambo some of Kaguvi’s followers also accompanied them. The Native Commissioner Mazoe reported in 1897, “Umquarti [Mkwati] told them that he himself was a God and would kill all the whites and was doing so at that time in Matabeleland and that Kargubi [Kaguvi] would be given the same power as he, Umquarti had and was to start killing the whites in Mashonaland. Immediately on receipt of these messages Mashayamombe started killing the whites and Kargubi then sent orders to all the paramount’s and people of influence to start killing the whites and that he would help them as he was a God.”[59]

From April 1896 Kaguvi was based at Mashayamombe’s kraal or Chena’s kraal south of the Umfuli (Mupfure) and a series of meetings were held there with representatives of the Mashona paramount’s. Witnesses at subsequent trials said Chief Chikwakwa sent Zhante, his commander in chief, Chief Zvimba sent his son, Chief M’Southi sent his younger brother, Chief Garamombe sent his son Zawara, Chief Kunzwi Nyandoro sent his son Mchemwa, even Chief Makoni sent his sons.

At these meetings news of the progress of the rising in Matabeleland and their support for a rising in Mashonaland against the whites was given. A simultaneous outbreak was to be made with the return of Tshiwa and Bonda with amaNdebele men. Messengers were to carry the news throughout Mashonaland and signal fires to be lit on the kopjes. Kaguvi’s leading role was emphasised by all witnesses. Zawara, son of Chief Garamombe, testified when facing trial for murder that at these meetings, “All this occurred through Kaguvi. He said all whites must die this year. He gathered us to his kraal and said, I am the God.”

Zhante, Chief Chikwakwa’s commander testified, “Kagubi sent two messengers to Mashonganyika’s. They went to Gonta’s and told the people they were to come to Kagubi’s at once. I went with them. I thought he would give us something to kill the locusts. When I got there he ordered me to kill the white men. He said he had orders from the gods.”[60]

All the witnesses said variations of the same. The testimonies came from Hartley (Chegutu) Marandellas (Marondera) Lomagundi, Mazoe (Mazowe) Umvukwes (Mvurwi) and Gutu districts; all districts where the Mashona Rebellion occurred. “I was working for Eyre[61] when the word came from Kagubi that all the white men were to be killed and a lot of men came to my master's place. I was told to get hold of his legs, so I threw him on the ground and the others hit him on the face. It was Kagubi’s fault.”[62] “The Mulenga said all the white men must be killed so I gathered all my people and went to White’s farm.”[63] “They said it was Kagubi’s orders to hit the white man so I did.”

Kaguvi’s role in the uprising was much greater than most spirit mediums

Ranger writes that the Kaguvi medium played not only an important role in co-ordinating the rising, but also that of the prophetic leader of a revolutionary rebellion. After the rising had broken out with the first killings he continued to play an important part in directing them and ensuring that goods taken from the whites were sent to him.

A witness described after the attack on Norton farm[64] on 17 June 1896 that after the murders, “we went home and feasted and were driving off the cattle when Kagubi sent and stopped us and took them himself.”

Ranger states that the Kaguvi was much more than a senior spirit medium and brought thousands of Mashona into the uprising. Marshall Hole wrote,[65] “They promised to give charms to all who would fight to render them proof against the bullets of the white man which would turn to water or drop harmless from the mouths of those they struck…In almost every kraal the natives, even the women and children, put on the black beads which were the badge of the Mhondoro, while their fighting men, with native cunning, waited quietly for the signal to strike down the whites at one blow. So cleverly was their secret kept, and so well laid the plans of the witch-doctors, that when the time came the rising was almost simultaneous and in five days over one hundred white men, women and children were massacred in the outlying districts of Mashonaland.”

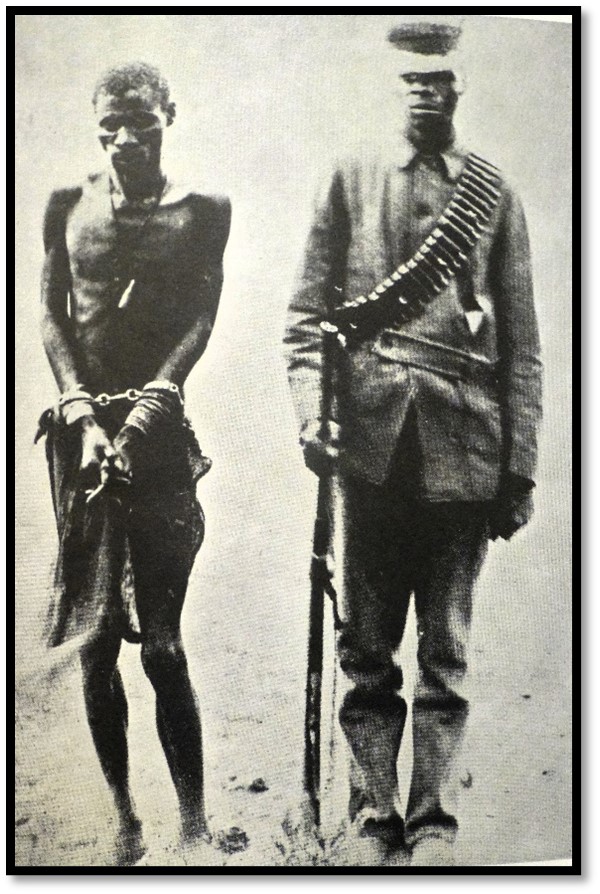

NAZ: The Kaguvi spirit medium under guard, 1897

Other factors contributing to the Mashona Rebellion

Whilst Kaguvi’s role is obvious, there were more influences at work. The encouragement of other spirit mediums should not be overlooked including Nehanda, Goronga and other senior mediums. Native Commissioner Kenny wrote after the rising, “in the event of a rising it will be to them that all blame must be attached, as there is without doubt a certain secrecy among the Mhondoro’s which is yet to be found out. As we all know in our last rebellion there were, so to say, two heads to the Mhondoro following, viz, Kagubi and Nehanda, to whom pretty well all other petty Mhondoro's were continually communicating…The importance of such people is so great that I have no hesitation in stating that no matter what other influence was in vogue could they be captured at any time previous to a contemplated rebellion, the whole conspiracy would collapse.”[66]

It must be remembered that the call to rebellion came at a time of general protest to the imposition of a hut tax and forced labour as well as natural phenomena such as drought and the rinderpest that killed off many cattle. Ranger writes that the powerful paramountcy’s were already “moving into intransigent defiance of the law.”

John White, a Mashonaland missionary, attempted to explain in 1897, “As is their custom these Mashonas when they need advice, resort to these mediums of their gods..” who replied, “If you want to get rid of all your troubles kill all the white men. They believed they had grievances; they ignorantly thought we had brought the plague amongst them; they knew nothing of venting their grievances in a constitutional manner. According to their notions, the best way to rid themselves of an evil is to destroy its cause. Hence they listened to the advice of their prophets.”

References

D.P. Abraham. The Monomotapa Dynasty. School of Oriental and African Studies and Institute of Commonwealth Studies, 1960

B.M. Fagan, Southern Africa during the Iron Age. Thames and Hudson, London, 1965

L.H. Gann. A History of Southern Rhodesia, Early days to 1934. Chatto and Windus, 1965

H. Marshall Hole. The Making of Rhodesia. F. Cass, London, 1967

T.O. Ranger. Revolt in Southern Rhodesia 1896-7. A Study in African Resistance. Heinemann, London 1967

The ’96 Rebellions. The British South Africa Company Reports on the Native Disturbances in Rhodesia, 1896-7. Book of Rhodesia, Silver Series Vol 2, Bulawayo 1975

[1] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P3

[2] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P12

[3] Ranger acknowledges in the Preface to Revolt in Southern Rhodesia (Px) that the role of these empires has been exaggerated and acknowledges David Beach’s contribution to Shona history and, “that the crucial units of Shona political history were in any case always the smaller localised communities under their chiefs…”

[4] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P14-15

[5] Ibid, P15

[6] Ibid, P4

[7] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P4

[8] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P2

[9] A History of Southern Rhodesia, P9-10

[10] Southern Africa During the Iron Age

[11] Ibid

[12] The Ngoni invasions included those of Ngwana, Zwangendaba, Maseko, the Swazi Queen Nyamazana and finally the amaNdebele under King Mzilikazi in 1836-40

[13] F.C. Selous. Travel and Adventure in South East Africa, London, 1893

[14] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P12

[15] NC Weale was dismissed in 1899 for ‘cohabiting with native women’ but was by no means the only culprit

[16] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P15

[17] See the articles The decline of the Mutapa state c.1623 – c.1902 and Dambarare – an Afro-Portuguese Feira site, both under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[18] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P25

[19] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P28

[20] Kunzwi’s stronghold was just west of the Nyagui river

[21] Ibid, P30

[22] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P31

[23] D. Beach. Resistance and Collaboration in the Shona country 1896-7. Institute of Commonwealth Studies Seminar, March 1971.

[24] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, Preface Pxi

[25] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P1

[26] J.V. Taylor. The Primal Vision. London, 1963

[27] A noted rain-maker in the Mavuradonha was the medium of Dzivaguru, who became almost the chief ritual officer of the Mutapas

[28] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P20

[29] See the article How Portuguese trade developed in Mozambique during the 16th/17th Centuries prior to the establishment of the feiras in the Mutapa State under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[30] A degredado was a criminal, condemned to death, but given the option of freedom in return for undergoing dangerous missions

[31] See the article Antonio Fernandes, probably the first European traveller to Zimbabwe in 1511 – 12 under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[32] A History of Southern Rhodesia, P17

[33] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P25

[34] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P25

[35] W.F. Rea S.J. The Missionary Factor in Southern Rhodesia. Historical Association of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, Local Series, 7, 1962

[36] To increase imperial vigilance, the Colonial Office appointed first Resident Commissioner and Commandant of Southern Rhodesia forces. He was Col. Sir Richard E R Martin KCB, KCMG who was appointed in March 1896. The Matabele Rebellion had broken out at the time and the British South Africa Company Police were almost depleted after the Jameson Raid. All police and military forces came under Martin’s authority and he served until 1898.

[37] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P50

[38] See the article Was Archibald Ross Colquhoun; first Administrator of Mashonaland 1890 – 92, a failure or was he actively undermined by Dr Jameson? Under Harare Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[39] Alfred Milner served as High Commissioner for Southern Africa and Governor of the Cape Colony from 1897 to 1905.

[40] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P194

[41] See the article Fort Haynes and the fight at Chief Chingaira Makoni’s Kraal under Manicaland Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[42] See the article Bulawayo and the Matabele Rebellion (or Umvukela) – Part 1, the first few weeks and the patrols sent to rescue outlying farmers, prospectors and storekeepers under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[43] All three sieges are described on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[44] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P201

[45] Native Commissioner David Mooney, along with two prospectors, John Stunt and A. Shell and three Indians trading at their store on the Umfuli (Mupfure) river were amongst the earliest murders in Mashonaland on the 14 June 1896. See the article Chief Chinengundu Mashayamombe’s stronghold, Fort Martin and Cemetery under Mashonaland West Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[46] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P202

[47] Ibid

[48] These young warriors were supporters of the Mpotshwana and Nyamanda faction in Matabeleland, not of chief Umlugulu

[49] Evidence taken by Col Robert Beal in July 1896

[50] M. Gelfand. African Background. The Traditional Culture of the Shona—Speaking People. Juta and Co, Cape Town, 1965 and another 33 books and numerous scientific papers on African religion and medicine

[51] For information on the Mapondera Rebellion of 1900 see the article The story of a Trooper’s experiences in the Imperial Yeomanry and Rhodesia Field Force during the second Boer War 1899 – 1902 under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[52] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P209

[53] See the article Mambo Rebellion Memorial – with three oral history accounts collected by Foster Windram in 1936 and 1938 concerning the killings at West’s store under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[54] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P211

[55] Kaguvi is also spelt Kagubi is a traditional name given to those who speak for the Mwari deity

[56] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P214

[57] Kaguvi whose Shona name was Gumboreshumba meaning: "lion's paw" lived in Chief Chikwakwa's kraal at present-day Goromonzi. He had four wives, one of whom was the daughter of Chief Mashonganyika's who lived close by. The other three wives were given by headman Gondo, also living close by. See the article Fort Harding, Chief Chikwakwa and Headman Gondo’s kraals and Warrendale Farm Police Camp under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[58] Ibid, P215

[59] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P218

[60] Ibid, P221

[61] Herbert Hedges Eyre murdered about 21 June 1896 on his farm on the Great Dyke; body found on 22 October 1896

[62] Ibid, P222

[63] James White murdered about 7 July 1896 murdered at Wesleyan Mission Farm, Marandellas

[64] Joseph Norton with his wife Caroline and daughter Dorothy were murdered on 17 June 1896 at Porta farm, with the farm assistant James Alexander and Miss Fairweather, their daughter’s nurse,

[65] H.M. Marshall Hole. Witch-craft in Rhodesia. The African Review, 6 Nov 1897

[66] Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, P223