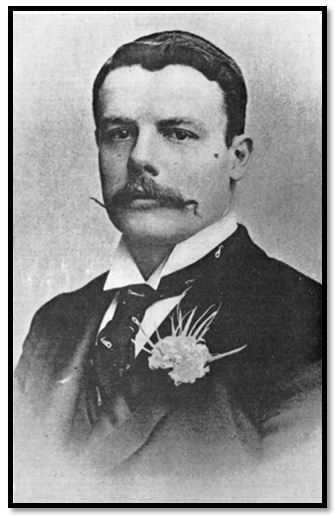

Henry Borrow, after whom Borrowdale is named

Acknowledgements

A number of authors have used Henry Borrow’s letters in the past with good reason; they are well-written and almost in diary style recording events through the prism of Borrow’s eyes and they are comprehensive…over 1,200 pages, at least two accounts were sent to The Times of London, but were not published. Robert Cary used them extensively, particularly in his excellent book Charter Royal and there are good and more comprehensive articles by D. Hartridge on Borrow in Rhodesiana No 18 of July 1968, (P22 – 36) with a repeat of the same article in Heritage No 22 of July 1970 (P157 - 171) Finally the valuable efforts of the staff of the National Archives of Zimbabwe, both in the past and present, as the custodians of these historical records need to be recognised and appreciated.

The origins of Borrowdale

Henry Borrow (he signed himself Harry in his family letters) was one of the partners of Messrs. Johnson, Heany and Borrow who went into business in 1891 at Fort Salisbury. At that time they were one of the few business entities with any capital in the country following their payment by Rhodes for successfully guiding the Pioneer Column to Mount Hampden, although Fort Salisbury was chosen as the better location. They also kept the oxen and wagons which had conveyed the Column upcountry, and had an immense start over everyone else with extensive interests in mining, transport and trading.

Their company concentrated mostly on buying farming land and mining claims; their Borrowdale Estates extended to over 22,275 hectares (55,043 acres) and was the original Pioneer land grant and named after Henry Borrow. Vegetables, including potatoes were planted and watered from the first man-made dam in the country; although the first season’s vegetables were badly damaged by insects, the experts said this was an event that would disappear by the second year [BO P.865] Later the original farm was divided up into farms, residential plots and commercial stands until it became the affluent suburb that Borrowdale is today.

Henry Borrow’s early life

Born in Lanivet in Cornwall, England on the 17th March 1865, he was the eldest son of Reverend Henry John Borrow, the Rector of Lanivet and Mrs Anne Borrow, née Kendall. He was educated at Tavistock School, although he finished his schooling at Sherborne School in 1881. As Robert Cary states, by then a young man of good character, but without sufficient means to go into business, he took the road to the Colonies, a route then being taken by many like him. In 1882 he was in South Africa and working on an ostrich farm near Cradock in the Cape Colony; by 1884 he was farming in partnership with Charlie Wallis at Waterford in the Grahamstown district, but found he was being imposed upon: “how galling to be corrected by a fellow one’s own age…I’m heartily sick of him and as there is a new police force to be raised I have sent my name in” [BO P.182] and so in January 1886 he joined the 2nd Mounted Rifles (Carrington’s Horse) and traveled to Bechuanaland (now Botswana) on the Warren Expedition under the command of Colonel Sir Frederick Carrington.

The Bechuanaland Protectorate was established by Britain in March 1885 following the Warren Expedition to protect the local tribes from Boer incursions and foreign powers, principally Germany, and was administered from Mafeking. The Bechuanaland Border Police (BBP) the forerunner of the British South Africa Company Police was formed in August 1885 and Henry Borrow was recruited to A Troop as a lance-Corporal along with his friend, Frank Johnson. Although Johnson was only eighteen at the time, he was quickly promoted to quartermaster-sergeant, Johnson’s strong personality and self-confidence ensured from the start that he was the leader and Borrow the supporter. Another new friend was an American, Maurice Heany.

In 1886 gold was discovered on the Witwatersrand, and reminded everyone of the legendary goldfields to the north discovered by Karl Mauch and Henry Hartley in May 1866 at Hartley Hills on the Umfuli (Mupfure) River. Borrow wrote to his father: “that the country [Matabeleland] must be fabulously rich, as the natives can obtain gold by putting skins in the river with the hair upstream, then taking the skins out and drying them in the sun (and then shaking) the gold out.”[BO P.253] This tale may have come from a Danish prospector, Erikson, who shows Johnson and Borrow quills of gold he brought back from the Mazowe Valley.

Tales of fortunes to be earned made everyone restless: “not that I have the fever or anything of that sort, but it appears to me a shame to throw away golden opportunities for the sake of £7 per month.” [BO P.238] Borrow; already promoted to corporal, and Maurice Heany, then an orderly, and Edward “Ted” Burnett and corporal John Anthony “Jack” Spreckley were prompted to resign from the BPP in February 1887 to accompany Frank Johnson to Matabeleland and try to win a mineral concession from King Lobengula of the amaNdebele. The entrepreneurial Johnson managed to find backers in Cape Town prepared to put up £900 in return for the four partners taking up one £25 share each and half of the final profits, the syndicate having the grand sounding name of The Great Northern Trade and Exploration Company; “rather a majestic title is it not?” [BO P.276] Borrow wrote that Matabeleland was healthy, but Mashonaland less so. Bishop G.W.H. Knight-Bruce asked them to report on the prospects for establishing a church.

The youthful five left Mafeking on 21 March 1887 with all they could carry on their horses and visited Khama, the Paramount Chief of the Bamangwato at Shoshong and were rewarded with a mineral concession that covered the country, before continuing onto Gubuluwayo. “That there’s gold there is a well authenticated fact.” [BO P.284] “We have just had a most satisfactory interview with Khama who has given us all that our hearts desired…i.e. the prospecting rights to the whole of his country and the right to pick out one or more blocks of 100 miles square to dig for gold, minerals and precious stones.” [BO P.291]

In Matabeleland

Lobengula however, was in no hurry: “time is made for slaves” [BO P.300] and it took two months of talks before the party was given permission to prospect between the Hunyani (Manyame) and Mazoe (Mazowe) Rivers, though Borrow and Heany stayed behind in Gubuluwayo; “Bug Villa” [BO P.372] Borrow describes “the wonderfully productive country” and how the local traders (James Fairbairn, James Dawson, George Phillips, and Johannes van Rooyen) lived on African food and beer. “The natives grow excellent rice in Mashonaland, sent down in neatly woven bags, any amount of local corn and mealies, tobacco, potatoes, sweet potatoes, ground nuts, etc. All the white people on the station eschew altogether bread and coffee and simply live on the things aforementioned, meat being very cheap, they have two meals a day one at 10am and another just before dusk, the interim being filled up with local beer, of which they drink enormous quantities.” [BO P307]

They left Gubuluwayo for a spell in Mangwato, Bechuanaland to clear up a misunderstanding over the concession with Khama; Borrow suspected the missionary James Hepburn of having misrepresented them: “it appears to me that it [the agreement] has been purposely misrepresented by the missionary there” [BO P326] Khama now regretted giving them sole prospecting rights and wanted to limit their monopoly to a few years. Heany and Borrow presented Khama with a barrel-organ [PO P.354] and their concession with Khama was drafted and signed on 17 December; they were permitted to prospect for five shillings a month, and to select up to 400 square miles for an annual payment of £1 per square mile and royalty of 2.5%.

They left for Gubuluwayo, but Lobengula was furious because Wood, Francis and Chapman have defied him and been prospecting. Lobengula sent out an amaNdebele impi to: “find out what they were doing, kill any messenger coming out from them and tear up all letters” [BO P.359] Despite this dispute, Wood, Francis and Chapman received a concession from Lobengula for the region between the Shashe and Macloutsie Rivers “the disputed territory” on 11 November 1887; but Johnson’s syndicate believed this same area belonged to Khama and was covered by their agreement.

The high hopes with which Johnson, Burnett and Spreckley started were dashed by one of the amaNdebele guides dying of malaria despite treatment and their supplies running short, although they did find gold in their alluvial pannings of the Mazowe River. By 12 November Johnson and his party were back at Gubuluwayo where they were accused of (1) poisoning the headman (2) being spies (3) writing a letter saying Lobengula had two tongues (4) kicking an amaNdebele (5) exceeding the King’s permission and using a spade to look for gold. After a ‘trial’ by twelve Indunas, Lobengula let them off with a fine of £100 in gold sovereigns, ten blankets and ten tins of gunpowder and they “were allowed to keep their wagon and equipment, though at first it was said they could only go with their boots in order to walk out of the country!” [ASH P.89]

They concluded that Mashonaland was rich in gold and the labour very plentiful and cheap: “if Lobengula does not throw open the country in another twelve months, it will be rushed as owing to the influx of diggers in the Transvaal, the country is getting quite a different class of man to that which it has had heretofore.” [BO P.372]

Robert Cary states the one abiding impression they left with was that Lobengula was not to be trusted; that he would take whatever they brought him in the way of gifts of guns and trading goods, but his promises meant nothing, and he would repudiate any past deals if it suited him. This character smear was grossly unfair to Lobengula, but formed the basis of all of Johnson’s future dealings with him.

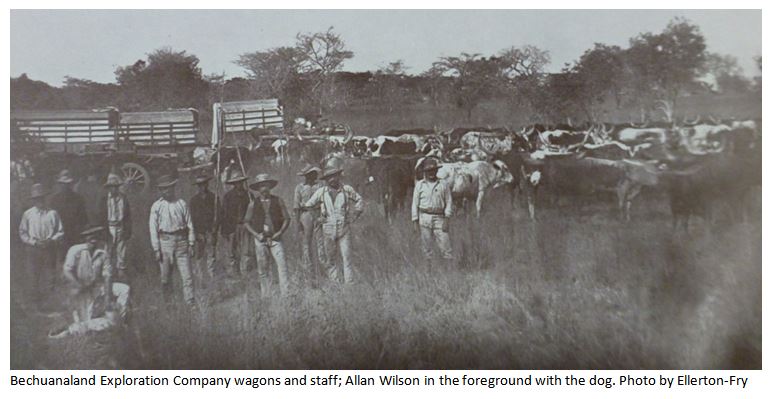

Bechuanaland Exploration Company

Now Johnson’s attention shifted to the region between the Macloutsie and Shashe Rivers; “the disputed territory” between Khama and Lobengula, which was also believed to have gold. They would use the mineral concession from Khama to float a company in “which we shall take part cash and part shares as our payment.” [BO P.388] So the Bechuanaland Exploration Company was formed with Lord Gifford and George Cawston as directors, Johnson as managing director, Heany as general manager and Borrow as local superintendent.

This was a full and eventful time for Borrow and Heany as they learnt the language and local geology and organised the transport and supplies for teams of prospectors and set up trading posts; Borrow acting as local blacksmith, carpenter and barber. “We are off early tomorrow for another month or so down the Limpopo river.” [BO P.409] Meanwhile in Lisbon, Johnson managed to secure a concession from the Portuguese Companhia de Mocambique which gave him the right to prospect twenty miles on each side of the Mazowe River, with the right to mark off 500 claims upon a royalty payment of 20% of all profits and 1% of output. This was in Johnson’s own name and not in the name of the Bechuanaland Exploration Company, another example of his self-regard. Here Borrow first met Allan Wilson, who was in charge of the prospecting team.

On 8 July 1887, P.D.C.J. Grobler who alleged he had negotiated a treaty between the Transvaal Government and Lobengula was passing through the “disputed territory” with his party when he was attacked by Khama’s men under Mokhuchwane and suffered wounds from which he died. Borrow in Shoshong missed the “affair” but states: “the whole business cannot but do us good with the Chief [Khama] as Heany and I both offered to go out with his people against the Boers.” [BO P436]

However, Lord Gifford and Cawston, despite being Directors of the Bechuanaland Exploration Company, had sent Edward Maund to negotiate their own new mineral concession with Lobengula. Gifford knew the Bechuanaland Exploration Company could never compete with Rhodes’ British South Africa Company, but hoped a concession would be a useful bargaining chip. Rhodes learnt of this manoeuver and hurriedly sent off his own party which arrived in Gubuluwayo before Maund. Harassed by concession hunters, on 13 October 1888, Lobengula put his “mark” to a mineral concession granted to Charles Rudd, James Rochfurt Maguire and Francis Thompson, in terms of which he surrendered all mining rights in his territories “the Rudd Concession” and promised not to grant land rights to anyone without the consent of the beneficiaries of the agreement.

In September 1888, Borrow told his mother that BPP police were stationed on the Limpopo River and he had prospectors on the Crocodile, Macloutsie and Limpopo Rivers; they have been using ‘Grobelaar’s road’ but “that they have cut their own road and that he met C.D. Rudd and his party on their way to Matabeleland.” [BO P.455]

The Rudd Concession

In early January 1888 Borrow wrote to his father: “Rudd has offered Lo Ben a present of 1,000 Martini-Henry rifles and 100,000 rounds of ammunition…also a bridge across the Zambezi [actually as recorded below it is a steamboat] this practically means the slaughter of the neighbouring tribes.” [BO .471]

The actual text of the Rudd concession reads as follows: Know all men by these presents that whereas Charles Dunnell Rudd of Kimberley, Rochfort Maguire of London, and Francis Robert Thompson of Kimberley, hereinafter called the grantees, have covenanted and agreed, and do hereby covenant and agree, to pay to me, my heirs and successors, the sum of one hundred pounds sterling British currency, on the first day of every lunar month, and further to deliver at my Royal Kraal, one thousand Martini-Henry breech loading rifles, together with one hundred thousand rounds of suitable ball cartridge, five hundred of the said rifles, and fifty thousand of the said cartridges to be ordered from England forthwith, and delivered with reasonable despatch, and the remainder of the said rifles and cartridges to be delivered so soon as the said grantees shall have commenced to work mining machinery within my territory, and further to deliver on the Zambesi River a steamboat with guns suitable for defensive purposes upon the said river, or in lieu of the said steamboat, should I so elect, to pay to me the sum of five hundred pounds sterling British currency, on the execution of these presents, I, LoBengula, King of Matabeleland, Mashonaland, and other adjoining territories, in the exercise of my sovereign powers, and in the presence and with the consent of my Council of Indunas, do hereby grant and assign unto the said grantees, their heirs, representatives, and assigns, jointly and severally, the complete and exclusive charge over all metals and minerals situated and contained in my kingdoms, principalities, and dominions, together with full power to do all things that they may deem necessary to win and procure the same, and to hold, collect, and enjoy the profits and revenues, if any, derivable from the said metals and minerals subject to the aforesaid payment, and whereas I have been much molested of late by divers persons seeking and desiring to obtain grants and concessions of land and mining rights in my territories, I do hereby authorise the said grantees, their heirs, representatives, and assigns, to take all necessary and lawful steps to exclude from my kingdoms, principalities, and dominions all persons seeking land, metals, minerals, or mining rights therein, and I do hereby undertake to render them such needful assistance as they may from time to time require for the exclusion of such persons and to grant no concessions of land or mining rights from and after this date without their consent and concurrence, provided that if at any time the said monthly payment of one hundred pounds shall be in arrear for a period of three months then this grant shall cease and determine from the date of the last made payment, and further provided that nothing contained in these presents shall extend to or affect a grant made by me of certain mining rights in a portion of my territory south of the Ramakoban River, which grant is commonly known as the Tati Concession.

This given under my hand this thirtieth day of October in the year of our Lord eighteen hundred and eighty-eight at my Royal Kraal.

his

(Signed) LoBengula X

mark.

C.D. Rudd,

Rochfort Maguire

F.R. Thompson

Witnesses,

(Signed) Chas.D.Helm

J.D.Dreyer

This period of intense negotiating for influence is reflected in Borrow’s letter from Shoshong on 17 March 1889 when he describes Jameson and Rutherfoord Harris who have been sent to make the first payments in terms of the Rudd Concession on behalf of the British South Africa (BSA) Company. Johnson learned from Borrow and Heany that the British favoured Lobengula’s rights over Khama to “the disputed territory” and that Lobengula “true to character” in Johnson and Borrow’s view: “says he does not understand the agreement and is reported to be trying the missionary (Helm) who interpreted it. This is all in our hands as we want to try and be paramount power in this part of the world and of course if a powerful company like this [B.S.A. Co.] went ahead it would prove a formidable opponent…The more time we get the better for us, as it allows of the Portuguese making more complete arrangements to support their claim to the country ceded to us; of course the Matabele themselves are nothing…but if an influential company gets control it outs a very different complexion on the state of affairs, as then, I take it, the boundary question would be a matter for arbitration, which no doubt will eventually come when England gets possession of Matabeleland as she doubtless will, but the longer it is delayed the better for us as it gives us more time to get full possession…the Portuguese have undoubtedly a very good claim to the country; at any rate better than anyone else, for Lobengula does not allow hunting north of the Hunyani River, saying that he cannot protect anyone there.” [BO P.492]

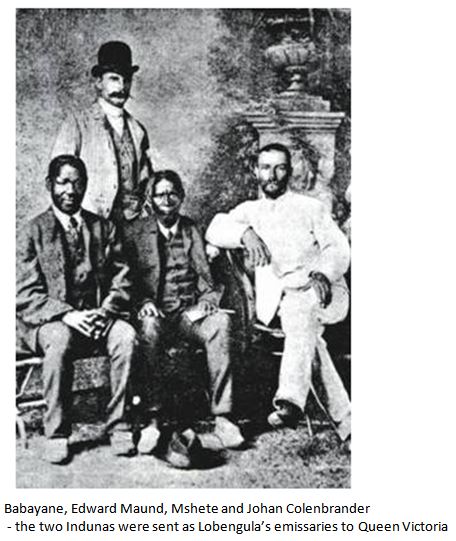

Disputes with rival concession seekers and letters to and from Queen Victoria

It does not appear that Edward Maund received any mineral concession from Lobengula, although he said he did, but he did manage to persuade Lobengula in April 1889 to send two of his Indunas, Mshete and Babayane to London to appeal to Queen Victoria to repudiate the Rudd Concession, or to declare a protectorate over Matabeleland and Mashonaland. Part of the letter reads: “Some time ago a party of men came into my country, the principal one appearing to be a man named Rudd. They asked me for a place to dig for gold, and said they would give me certain things for the right to do so. I told them to bring what they would give and I would then show them what I would give. A document was written and presented to me for signature. I asked what it contained and was told that in it were my words and the words of those men. I put my hand to it. About three months afterwards I heard from other sources that I had given by that document the right to all the minerals in my country. I called a meeting of my Indunas and also of the white men, and demanded a copy of the document. It was proved to me that I had signed away the mineral rights of my whole country to Rudd and his friends. I have since had a meeting of my Indunas, and they will not recognise the paper, as it contains neither my words nor the words of those who got it. After the meeting I demanded that the original document be returned to me. It has not come yet, although it is two months since, and they promised to bring it back soon.”

The Queen’s reply, written by Lord Knutsford, who presented each of the Indunas with a rams-horn snuffbox mounted in silver and a portrait of the Queen for Lobengula, was to the effect that Lobengula should not give away his property to one man: “the Queen has heard the words of LoBengula. She was glad to receive these messengers and to learn the message which they have brought. They say that LoBengula is much troubled by the white men, who come into his country and ask to dig gold, and that he begs for advice and help. LoBengula is the ruler of his country, and the Queen does not interfere in the government of that country, but as LoBengula desires her advice, Her Majesty is ready to give it, and having therefore consulted Her Principal Secretary Of State holding the Seals of the Colonial Department, now replies as follows: - In the first place, the Queen wishes LoBengula to understand distinctly that Englishmen who have gone out to Matabeleland to ask leave to dig for stones, have not gone with the Queen's authority, and that he should not believe any statements made by them or any of them to that effect. The Queen advises LoBengula not to grant hastily concessions of land, or leave to dig, but to consider all applications very carefully. It is not wise to put too much power into the hands of the men who come first, and to exclude other deserving men. A King gives a stranger an ox, not his whole herd of cattle; otherwise what would other strangers arriving have to eat?”

There was also a letter from the Aborigines Protection Society urging the King to be “wary and firm” in his dealings with concession hunters: “We think you acted very wisely as a great chief when you dispatched messengers to our Queen on the present occasion. The digging of gold is a new industry among your people. It is not new among white men, hence your wisdom in sending to our Queen and her advisers on this matter. You already know the value of gold, and are aware that it buys cattle, and everything else that is for sale, and that some men set their hearts on it, and dispute about it as other tribes fight for cattle. As you are now being asked by many for permission to seek for gold, and to dig it up in your country, we would have you be wary and firm in resisting proposals that will not bring good to you and your people.”

In another letter [BO P.492] Borrow says Lo Ben is unlikely to any permanent camps between Gubuluwayo and the Zambezi River, that he expects the British Government will take over Matabeleland eventually, but that the longer their company [Johnson and Company] can entrench themselves in Mashonaland the better. He believes the Portuguese have a better claim to the country than anyone else and welcomes the news that Sir Henry Loch is replacing Sir Hercules Robinson as Governor of Cape Colony and High Commissioner for Southern Africa and adds: “Sir F. Carrington is coming up here, he says he will get us into the Shashe and Macloutsie territory; needless to remark we have made it worth his while.” [BO P.500]

At this time Edward Maund met Rhodes in Cape Town and afterwards Rhodes cabled Gifford and Cawston saying they would all be better off in an amalgamated company. Maund assumed that Rhodes’ actions were brought about because his mission to England posed a threat; but in fact, the Colonial office had already informed Gifford and Cawston that their chances of receiving a royal charter would be greatly enhanced if they combined under the one entity of the BSA Company. Borrow wrote: “the London people are very sweet on that double distilled liar Maund.” [BO P.506]

In May Borrow told his mother that Maund and Johnson have nearly come to blows [BO P.541] and that: “the annihilation of the whites is being openly canvassed” in Matabeleland; he would welcome it if they were to: “try conclusions with the whites…what a chance for the Metford…I think the Maxim gun and the Police quite equal to the Matabele nation.” [BO P.567] Edward Maund was unpopular and: “the concession he pretended to have secured for Lord Gifford is clearly a myth.” [BO P.570]

The Colonial Office wished to fill the territorial void in Matabeleland and Mashonaland and prevent their occupation by the Portuguese and Transvaal, but without incurring any financial liability. The Bechuanaland Exploration Company lacked any real financial resources to fulfill their obligations including building a railway; Rhodes on the other hand, had the resources. He contacted Gifford and Cawston, who in exchange for a million shares and Directorships in the BSA Company, agreed to support Rhodes application for a royal charter.

When Borrow heard of this he was outraged: “my own private opinion is that Gifford and Cawston should be prosecuted for fraudulent breach of trust” [BO P.596] and called their actions: “the most bare-faced piece of swindling I ever heard of” [BO P.597] and “if they were a little younger I for one should have the greatest pleasure in obliging them for a few minutes.” [BO P.600]

The British South Africa Company and the Royal Charter

The BSA Company had been formed in October 1888 and Rhodes spent much of his time in London discussing with the Colonial Office how its operations would be carried out. The Colonial Office demanded that the Governor of Cape Colony and High Commissioner for southern Africa, Sir Hercules Robinson, and then from June 1889, Sir Henry Loch, must approve and accept all BSA Company treaty negotiations with local Chiefs. In effect, any powers given by these treaties were being exercised by the BSA Company on the British Government’s behalf.

Matters speeded up in July 1889; Lord Gifford and George Cawston had applied for a royal charter on behalf of the Bechuanaland Exploration Company to develop mineral concessions in the Bechuanaland Protectorate and Matabeleland; instead a royal charter was granted on the 15 October 1889 to the BSA Company and came into effect on 20 December for an initial period of 25 years.

Leander Starr Jameson was the single most influential individual in breaking down Maund’s influence on King Lobengula. As noted above, Gifford and Cawston were enticed into jumping onto the BSA Company bandwagon and Lobengula was convinced by Jameson of the potential threat of the Portuguese and Boers. This had a basis of truth as the Rev Helm’s letter of 20 December 1889 states: “There have been some Portuguese on the Umfuli River, three European officers and about 400 native soldiers. They built a stockade. The Chief, through Mr. Moffat, sent a letter to ask them what they wanted in his country. The messenger returned saying the Portuguese had left. If so they will probably return after the rains are over. Both Chief and people seemed to think that there was collusion between the English and Portuguese. But he was reassured when Mr. Moffat told him if he found any English among the Portuguese, he (Mr. Moffat) would leave them to him.”

In addition, Jameson persuaded Lobengula that the BSA Company’s plans were quite modest…would Lobengula give permission for some prospecting in a small region west of the Tati Road? Lobengula agreed, and a small party of prospectors began searching. By January no minerals had been found and Jameson asked Lobengula if the prospectors could enter Mashonaland on the road that Selous had planned for the Pioneer Column? Lobengula, not knowing about the Pioneer Column, took the bait; and even volunteered 100 labourers to assist in cutting the road.

Frank Johnson met with Rhodes in Kimberley on 12 – 14 October 1889 and tried to bring an amalgamation between the Bechuanaland Exploration Company and the BSA Company on a 2 for 1 basis for: “nearly one-quarter of that gigantic concern is infinitely better than our old concession.” [BO P610] The current working capital of the BSA Company was £222,000 but Rhodes expected to spend £1 million and this will: “necessitate calls on the shareholders to the tune of three times the number of shares they hold.” [BO P.613] Rhodes was prepared to lend Johnson, Heany and Borrow the necessary extra capital, but they would have to stay with the [BSA] company for at least 12 months working Mangwato, the Shashe, the Macloutsie and Barotseland.” [BO P.614]

In October 1889 ‘a down on his luck’ Selous had met with Borrow and Heany at Shoshong to renew a friendship that began at Lobengula’s kraal in November 1887 on their return from the Mazowe River and the idea came to Johnson that Selous was the best man to lead a prospecting expedition through Portuguese territory back to the Mazowe valley. Described by Borrow: “as the finest and pluckiest man I have ever met” the five men – Selous, Johnson, Heany, Burnett and Borrow agreed to form a new syndicate called the Selous Exploration Syndicate with Selous having 1,000 shares, the others having 800 each and the project funded through a cash injection of £10,000 from influential Cape businessmen headed by Edouard Lippert.

As it was impossible to travel in the rainy season, Selous took a trip back to England where he met Rhodes for the first time. Rhodes was engaged in negotiating a Royal Charter for the BSA Company and outlined his plans to enter Mashonaland through Gubuluwayo. Selous was unenthusiastic about this approach, not only because he believed it would be opposed by the amaNdebele, but because he believed Mashonaland was not Lobengula’s to give away. He wrote a frank letter to the Fortnightly Review on the subject: “I have gathered that it is believed by the majority of the few men who have any ideas on the subject that the Mashonas are a people conquered by the Matabele, and are now living peaceably under their protection, and paying tribute to their King, Lobengula. This is altogether a mistake.” [T&A] This statement put Rhodes in great difficulty because the Rudd Concession assumed that Lobengula could grant mineral rights to Mashona territory.

Selous the concession seeker

On his return to Cape Town, Selous who was: “entirely new to the mysteries of company-mongering” [BO P.547] received an agreeable surprise when he was paid £1,300 for his shares in the syndicate which had been issued to him free. Johnson and Selous in Cape Town had a new strategy which went far beyond their complying with the terms of their concession with the Companhia de Mocambique; they would sign separate mineral concessions with the Chiefs that Selous already knew in Mashonaland and then sell them to Rhodes and his BSA Company.

Selous’ expedition was a great success as he obtained mineral concessions from the Makorikori Chiefs Mapondera and Temaringa which gave the Selous Exploration Syndicate (SES) sole mining rights in the Mazowe valley, and in the document they state their complete independence of Lobengula. Selous wrote: “here you have a concession embracing probably the richest little piece of country in all Africa…This concession is perfectly square, fair and genuine and nothing can upset it…The Matabele claim to this country is preposterous.” [SES letter 2 August 1889] and at the same time he was advocating the route from Palapye though the future site of Fort Tuli and striking across country over the Nuanetsi (Wanetse) and Lundi (Runde) Rivers, crossing the headwaters of the Sabi (Save) River to the source of the Mazowe River at Mount Hampden. [T&A P.310]

Selous had found obvious signs of Portuguese influence, flags and uniformed natives, as far west as the Umniati (Munyati) Rivers [T&A P.309] and wrote urgently to Rhodes; “It (is) absolutely necessary for the British to take possession of the country during the coming year. It (is) an intolerable thought that we should lose it and the Portuguese get possession of it.”

In the meantime Frank Johnson learnt that Maund’s concession with Lobengula which had been backed by Gifford and Cawston, both directors of his Bechuanaland Exploration Company had been in the name of a nominee company and that he, Borrow, Heany, Burnett and Spreckley were not included in the amalgamation deal with the BSA Company. To add insult to injury, Gifford and Cawston now publically stated that any mineral rights in “the disputed territory” were included in the Rudd Concession.

Borrow and colleagues join Cecil Rhodes

Borrow was still a local Superintendent of the Bechuanaland Exploration Company and was writing to his father that: “Rhodes is anxious to get Johnson, Heany and I to work with him or come under his flag.” [BO P.600] Rhodes offered Johnson, Heany and Borrow three thousand shares each in the BSA Company and when he heard of Selous’ concessions with Chiefs’ Mapondera and Temaringa and offered to buy out their shares in the Selous Exploration Syndicate. Borrow was elated writing: “Heany and I have decided to stick to Rhodes all through and to work for him and the Chartered Company in every way we can” [BO P.634] However much more experienced he was in the intricacies of forming companies, Rhodes understood how valuable to him were the connections and combined knowledge of Johnson, Heany, Selous and Borrow.

Johnson and Heany met with Rhodes in Kimberley to discuss the situation and to form a plan for getting to Mashonaland. Out of their discussions emerged a “Memorandum of Agreement between Cecil John Rhodes, Maurice Heany and Frank Johnson.” This hare-brained scheme involved raising 500 European men with military experience and concentrating them on the Shashe River; then 400 mounted men supported by the remainder with the wagons carrying reserve ammunition and supplies would make a dash on Gubuluwayo with the aim of killing Lobengula and destroying his military kraals, or capturing him and making him hostage. Johnson and his colleagues would earn £150,000 and 50,000 morgen (105,847 acres) of land and all captured horses and cattle, but this plan was to be treated as confidential: “as there is sure to be a certain amount of false sympathy in England about any savages.” [BO P.660]

According to Johnson this scheme was betrayed by the Revd. Hepburn in Shoshong becoming suspicious at the arrival of early recruits and when questioned, Maurice Heany “spilled the beans” so that Hepburn informed Sir Sidney Shepherd, the then Administrator of Bechuanaland about the plot and he informed Sir Henry Loch and finally Rhodes was forced to deny the whole affair.

According to Johnson, whose inaccuracies and blatant exaggerations of his own role are recorded in his book Great Days, the document was signed on 7 December 1889, but only a draft contract drawn up by Johnson, has ever come to light.

Selous, back from his trip to Mashonaland, was in Kimberley on the 6 December and met Rhodes with Johnson and Heany the next day. Rhodes was persuaded by Selous that the direct attack on Lobengula was madness; it was far less risky to build a road along the edge of Matabeleland and make for Mount Hampden. Johnson was enraged at the disruption to his plan and never forgave Selous who is constantly criticised and derided in Great Days.

Planning to occupy Mashonaland

For another two days the four men discussed various options before coming up with the final scheme to peacefully occupy Mashonaland with the Pioneer Column. Selous argued that the legality underlying the minerals rights to Mashonaland given by the Rudd Concession were suspect; this was proven through the concessions with Mashona Chiefs in the Mazowe valley and their declarations of self-rule rather than their amaNdebele domination, but Rhodes argued this reason only helped the Portuguese cause.

Johnson, Borrow and Heany agreed to give up their rights in the Selous Exploration Syndicate and Selous accepted £2,000 from Rhodes for his efforts in obtaining the Mapondera / Temaringa concessions. Johnson, Heany and Selous tried to persuade the remaining syndicate members to give up their rights in return for a 20 by 5 mile land concession in Mashonaland, but they bargained on obtaining better returns from the BSA Company and paid Chief’s Mapondera and Temaringa £100 on 13 December 1890, the day after the occupation of Fort Salisbury. They then offered Rhodes their concession for £10,000 in cash and 10,000 BSA Company shares, but Rhodes would not be intimidated, and in the end, they received nothing.

On 15 December 1889 the first £15,000 payment was made for the contract between Johnson, Heany, Borrow and the BSA Company to set up the Pioneer Corps. Selous having played such a prominent part in the plan was however excluded from the contract, probably due to Frank Johnson’s influence and taken on as the Intelligence Officer at 30 shillings per day.

Borrow’s letter written on Bechuanaland Exploration Company Limited notepaper from Palapye on January 15th, 1890 to his father very neatly summarises the contract: [BO P.768]

“NB: the whole of this letter is really a trade secret and I should be sorry if any of it got abroad. H.B.

We have a very good scheme on now which I think might be worth a great deal of money to us. Mr Rhodes has fully recognized that he must occupy Mashonaland next winter as if he does not he feels quite sure that the Portuguese will have made good their foothold and will endeavour to get the question settled by arbitration which Rhodes fully recognizes would be fatal to his interests; so the question then cropped as to the best and most expeditious manner of doing this. Selous has pretty well disproved the Zambesi route, and on that account Rhodes has stopped the building of the gunboats that were already commenced.

When Heany was in Kimberley, he and Johnson put their heads together and at Rhodes’ request submitted to him the following scheme.

We / Johnson, Heany and Borrow / undertake for £87,500 to take an expedition into the Mashona country and to hold the country for a period of three months i.e. 15 July to 15 October, then Rhodes takes over the country with his regular Police and establishes civil Government, but he reserves to himself the right to call upon us to hold the country for a further period of six months at a rate to be subsequently agreed upon. We further agree to make a good wagon road from this place to Mt Hampden, via the Lundi River, a distance of about 600 miles and Rhodes further promises to lend us the following stores;

Two 7 pounders, 100 rounds shrapnel and 100 conical

Four Maxims and 125,000 rounds ammunition

Two hundred Martini Henri rifles and 250,000 rounds Martini Henri ammunition

Two hundred sets saddlery

The total expedition will consist of 126 Europeans, 50 mounted Bamangwato and 150 natives for road making comprising:

100 Europeans mounted

50 Bamangwato mounted

3 Troop leaders

6 Section Leaders

2 Geographers (Selous and Fry)

1 Conductor Transport

2 Asst. Conductors Transport

1 Artillery Superintendent

1 Quarter Master

2 Clerks

2 Farriers

1 Saddler

1 P. Medical Officer

1 Assistant Surgeon

3 Army dressers from Medical Staff Corps

150 native labourers

326 To this must be added the drivers and leaders of 80 wagons.

Johnson reckons the total cost of the expedition as follows: As the contract price is £87,500 we three should have some £28,000 to divide between us to which can safely be added another £5,000 saved on rations, horses and transport and at the end the end we should have £10,000 worth of horses, oxen and other plant.

In addition to this, we three are to receive 120,000 acres of agricultural land in 12 farms of 5,000 morgen at our own selection and the right to 60 reef claims for halves with Charter [BSAC] besides the 15 claims per man to which every member of our force is entitled on half with Charter.

No licence to be charged us on claims which are on halves with Charter, but we also have [the] right to select and mark out all alluvial claims we can work on payment of £1 per claim.

This is the gist of the preamble told in pretty well Johnson’s own words. Selous is on the road up now and will make the road to the Shashe at once and as soon as I return from Bulawayo I will go down to help to raise the men as we must leave here in April. It is certainly a glorious scheme [if] it will go through and it will make our fortunes, not much doubt of that.

I think we are really on the right track now and cannot help making a good thing out of it. It will be splendid sport too, we shall go up in the winter when there will be very little horse sickness and we shall have plenty of time -before Rhodes comes up - to select the very best farms in the country. These farms should be of immense value as we shall get them in the best mineral part of the country.”

The main political and delay to Rhodes’ plans at this time was Edward Maund who, as we already know, had delivered a letter from Lobengula and the reply from Queen Victoria. In October 1889, the Colonial office became concerned that a mineral concessionaire might leave the British government to pick up expenditure and commitments in preserving the peace, so was again forced to write to Lobengula, making it clear that they now approved: “a grant to one man to avoid disputes” but in Gubuluwayo Maund was still briefing Lobengula against dealing with the BSA Company and Rhodes. Borrow refers to Maund in his letters as “a scoundrel,” “a cur” and “a forger.”

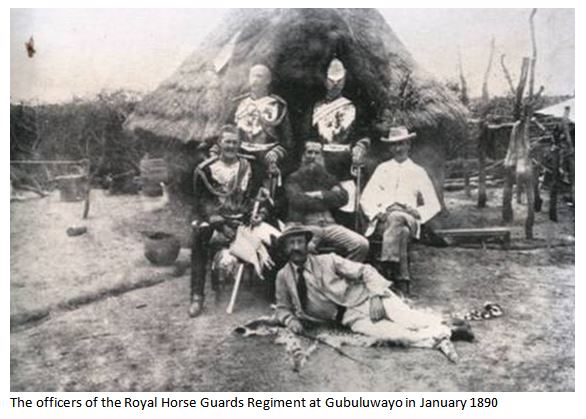

To give grandeur to the Queen’s reply, Rhodes requested that officers of the Royal Horse Guards deliver the message and this was approved. By 17 December, Captain Victor Ferguson, Surgeon Major H.F. Melladew, Major Gascoigne and Corporal-Major White had left Kimberley in their special coach laden with their uniforms and gifts. They were accompanied by Henry Borrow who was given the task of escorting Queen Victoria’s delegation to see King Lobengula. After delays in visiting Khama and other Chiefs they arrived in Gubuluwayo and met the King on 29 January 1890 where they remained for ten days. According to Robert Cary, Captain Ferguson presented his uniform, complete with metal breastplate, to Lobengula as grand parting gesture, but was probably pleased to get rid of it in the sweltering summer heat!

The letter they presented to Lobengula, again written by Lord Knutsford stated: “The Queen has kept in her mind the letter sent by LoBengula, and the message brought by Umshete and Babjaan in the beginning of this year, and she has now desired Mr. Moffat, whom she trusts, and whom LoBengula knows to be his true friend, to tell him what she has done for him and what she advises him to do.

2. Since the visit of LoBengula's envoys, the Queen has made the fullest inquiries into the particular circumstances of Matabeleland, and understands the trouble caused to LoBengula by different parties of white men coming to his country to look for gold; but wherever gold is, or wherever it is reported to be, there it is impossible for him to exclude white men, and, therefore, the wisest and safest course for him to adopt, and that which will give least trouble to himself and his tribe is to agree, not with one or two white men separately, but with one approved body of white men, who will consult LoBengula's wishes and arrange where white people are to dig, and who will be responsible to the Chief for any annoyance or trouble caused to himself or his people. If he does not agree with one set of men there will be endless disputes among the white men, and he will have all his time taken up in deciding their quarrels.

3. The Queen, therefore, approves of the concessions made by LoBengula to some white men who were represented in his country by Messrs. Rudd, Maguire, and Thompson. The Queen has caused inquiry to be made respecting these persons, and is satisfied that they are men who will fulfil their undertakings, and who may be trusted to carry out the working for gold in the Chiefs country without molesting his people, or in any way interfering with their kraals, gardens, or cattle. And, as some of the Queen's highest and most trusted subjects have joined themselves with those to whom LoBengula gave his concessions, the Queen now thinks LoBengula is acting wisely in carrying out his agreement with these persons, and hopes that he will allow them to conduct their mining operations without interference or molestation from his subjects.

4. The Queen understands that LoBengula does not like deciding disputes among white men or assuming jurisdiction over them. This is very wise, as these disputes would take up much time, and LoBengula cannot understand the laws and customs of white people; but it is not well to have people in his country who are subject to no law, therefore the Queen thinks LoBengula would be wise to entrust to that body of white men, of whom Mr. Jamieson is now the principal representative in Matabeleland, the duty of deciding disputes and keeping the peace among white persons in his country.

5. In order to enable them to act lawfully and with full authority, the Queen has, by her Royal Charter, given to that body of men leave to undertake this duty, and will hold them responsible for their proper performances of such duty. Of course this must be as LoBengula likes, as he is King of the country, and no one can exercise jurisdiction in it without his permission; but it is believed that this will be very convenient for the Chief, and the Queen is informed that he has already made such an arrangement in the Tati district, by which he is there saved all trouble.”

Borrow’s role in the Pioneer Column

Rhodes wanted to occupy Mashonaland before the Portuguese gained a further foothold; Selous had “pretty well disproved” the Zambezi route so Rhodes stopped building the steamboat; the wet weather would give them a twelve month start to consolidate their position in Mashonaland.

Henry Borrow was appointed the adjutant-to-be with the rank of lieutenant of the Pioneer Column; potential recruits were told to make their way by train, horseback, ox-wagon and foot to the Central Hotel in Kimberley where each man was required to attest that he: “faithfully declared, undertook, promised and agreed” to serve the BSA Company for a period of 6 to 15 months. At the end of their service they would be given free passage back to Kimberley, or could stay on in Mashonaland. Borrow found time to play some sport including two cricket matches between the “Colonials” and “home-born,” run a 7 mile paper chase, and play a tennis tournament against the Mafeking farmers which the recruits won easily. Adrian Darter in A Troop wrote: “he took an interest in all of us and joined in our sport.” [AD P33]

From the Marico River on 26 May 1890, Borrow wrote that Johnson had gone on ahead with Pennefather. Sir John Willoughby had been tipped to lead the British South Africa Police (BSAP) but Sir Henry Loch has appointed a man he already knew, Edward Pennefather. Sir Henry Loch feared the Boers might mount a rival expedition and Rhodes promised to compensate Johnson and his partners if any delays were caused by this factor. [BO P.725]

Major General P.S. Methuen inspected the force and approved their departure. From Baines Drift Borrow wrote to his mother that Selous thought the amaNdebele would fight, but in the meantime: “they are sending a commission of headmen to the Colonel [Pennefather] to tell him with Lo Ben’s compliments that he does not see why the white and black men cannot live in the same country.” [BO P.736]

Two parallel roads are being built by 100 Europeans and 300 natives in advance parties at the rate of ten kilometres a day; Borrow acted as interpreter and preferred being with the road-building party: “as I find the discipline very irksome” [BO P.745] but was very proud of being a part in the great adventure: “this Company will yet be the biggest thing the world has ever seen” [BO P.643] and later “we are certainly one of the greatest and finest expeditions that has ever been raised.” [BO P.732]

There were thirty-six of their own wagons, fifteen belonging to the BSA Police and ten belonging to the prospecting party. They came across the Banyai tribe hiding in the kopjes who stated that they were glad the white men had come and were building a road as now they would be able to work on the Rand [BO P.744]

On 17 August at Fort Victoria Borrow wrote that the origins of Great Zimbabwe were obscure: “and most of the theories are absurd” [BO P.761] and that they expected to be at their destination, Mount Hampden, in twenty days.

On 30 August at Umtigesa’s kraal he wrote to his father that he expected the eleven hundred oxen and eighty-four wagons should make them £18,620 [BO P.767]

On 7 September on the Umfuli River he wrote that: “this will really be a fine and glorious place to settle down and make one’s home. Heany and myself fully intend to have a nice place and make ourselves comfortable.” [BO P.774] and “we are all very much pleased with the country, the climate is superb…there are splendid long valleys here that one could plough to any extent…every little hollow has a small stream running down it.” [BO P.775]

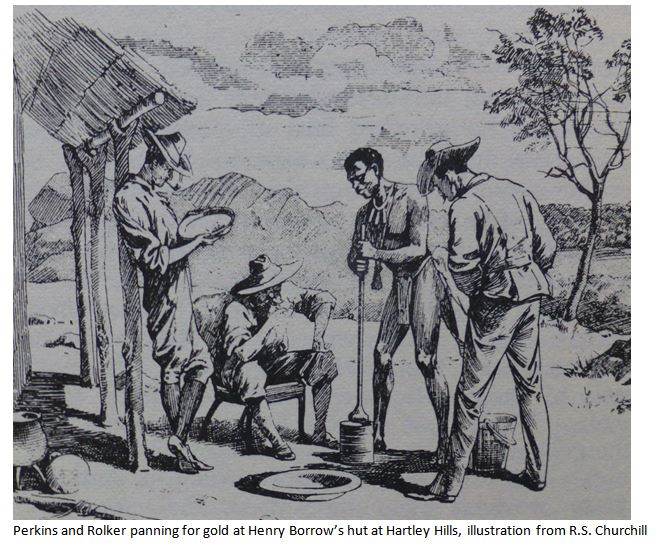

The flag was raised at Fort Salisbury on 13 September, but before the discharge of the Pioneer Column on 30 September 1890, Johnson, Burnett and Borrow had already left and were prospecting at Hartley Hills from where Borrow wrote: “Here we are on the great Mashonaland Gold Fields and the fields on which Mauch stood as one stupefied by their immensity and beauty, this is the place that has been talked about, written about and thought about by all South Africa, we have pegged off ground for half a dozen companies.” [BO P784-5]

Messrs. Johnson, Heany and Borrow

Borrow was made a partner in the firm of Messrs. Johnson, Heany and Borrow. The company engaged in land and mining speculation, hired out the oxen and wagons that were used by the Pioneer Column and attempted to open a route from Salisbury to the East Coast at Beira. Johnson was managing director, Heany the local manager in Manicaland and Borrow the local manager in Mashonaland. Commerce was what drove Borrow and is reflected in his letters: “None of us propose taking any billet under the Charter as it would not allow of us having that free action which we must have if we want to carry out all our projects and they are many.” [BO P.731]

“We hope to clear out of this contract £33,000, or at any rate, £10,000 each, and I have no doubt we shall make a great deal more out of the land.” [BO P.753]

“We have offered Selous £5,000 for his 20,000 acres and I fancy he will sell; he does not seem inclined to settle down in the country.” [BO P.753]

“We ought to be the principal man in Mashonaland, with our claims, lands, shares, transport plant, salted horses, etc.” [BO P.767]

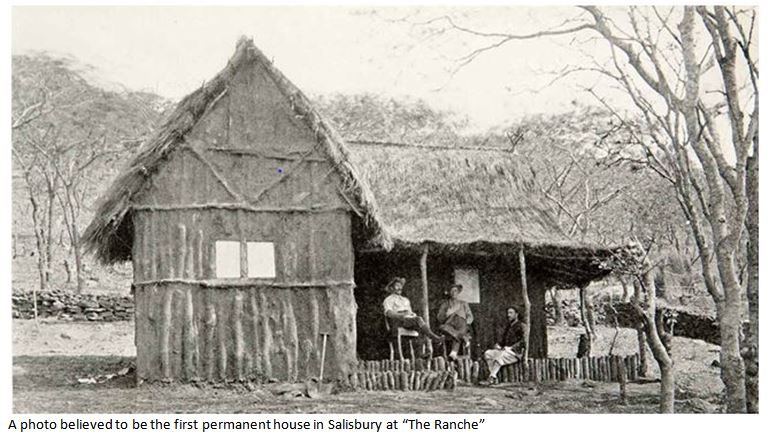

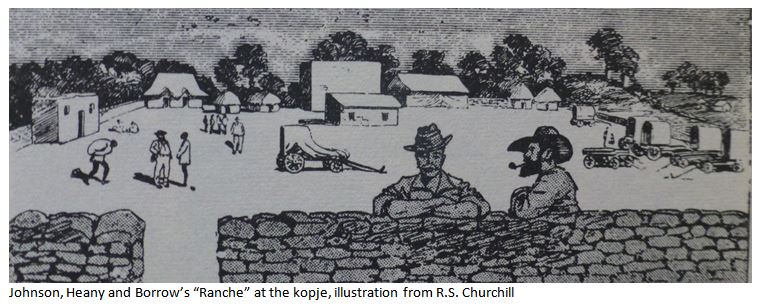

Their headquarters was a large stand of over five hectares on the western side of the kopje which gave rise to its name “The Ranche” and is where Ranche House College now stands. On 5 October 1890, it consisted of “an enormous store made entirely of wagon sails and a few marquee tents for an office, mess tents and tents to sleep in.”[BO P.794] but this was soon replaced with permanent buildings.

By 13 October they had: “30 feet of work done at Beatrice Mine” [BO P.796] and two days later: “hope to bring in more supplies before the rains…the company are sending ponts and boats for the big rivers in the east coast.” [BO P.799]

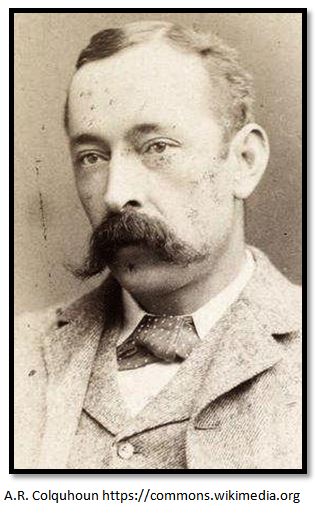

Borrow toured Mashonaland with Heany and A.R. Colquhoun, the Administrator; “we may claim to have had a pretty fair finger in every pie; of course we have the whip hand of everyone in the country as we are the only people who have supplies, cash and other little odds and ends that the soul of the unregenerate loveth.” [BO P.804]

From the Ranche he wrote to his mother on 4 November 1890, that: “many Colonials decided to wait a bit and consequently a great many of the late Pioneer Corps are young fellows not long out from home…I have been busy getting men away to Manica country.” [BO P.811]

On 10 November he was going to the junction of the Sebakwe and Bembesi Rivers to look for a rumoured goldfield. [BO P.817] William Harvey “Curio” Brown describes their meeting: “One evening Messrs Borrow and Stevenson came along with a party of natives who were taking them out to show them some old workings. They were much astonished at finding me there with no white partner [Brown had been sent by Johnson and loaned an ox-wagon to take supplies to Hartley Hill] having flattered themselves that they were further afield than any prospector had yet been. They assumed a mysterious air concerning their destination, as gold-seekers usually do when they think they have a rich find; hence I asked them no leading questions. They camped just across the river from me and the next morning took their course towards the Umsweswe River.” [WHB. P.146]

He told his mother that James Dawson has come as Lobengula’s accredited agent: “asking for a place to dig…seems funny to take a man’s country and then give him forty claims out of it.” [BO P.817]

However he had to write to his mother who had addressed him as Captain Borrow on the cover of the envelope: “let me beg of you not to address me as Captain, a title to which I have no right whatsoever, and even supposing I had the best in the world, should be very sorry to make use of. I aspire to neither the title, nor sword. I am not a soldier…” [BO P.823] He mentioned that they found no gold reefs worth pegging on the Sebakwe River.

In his book Travel and Adventure in South-East Africa, Selous says Johnson, Heany and Borrow were household names in Mashonaland “and all three were brimming over with enthusiasm and energy, are possessed of that dogged perseverance and untiring patience which has already won half the world for the Anglo-Saxon race.” “Ever since the occupation of Mashonaland they have been the life and soul of the country.” “During the hard times experienced by the Pioneers, during the first rainy season after the occupation of Mashonaland, Heany and Borrow (Johnson had gone down to Cape Town to prepare for the opening of the east coast route from Beira) endeared themselves to all classes of the community by their kindness to all who were in distress…” [T&A P.362]

Borrow recounts the arrest of P. d’Andred and Gubu [Paiva de Andrade and M.A. Gouveia] by Patrick Forbes and the BSA Company Police at Mutasa’s kraal near Penhalonga [BO P.830] but seemed to fail to understand the longer-term repercussions for Anglo-Portuguese relations.

Commercially things became tough as the firm experienced the classic problem of overtrading…in buying as many gold claims as they could and purchasing substantial areas of land for 8d. per acre. Borrow states he has a 48,000 acre block near Salisbury, the future Borrowdale. [BO P.849] From the Ranche on 28 December 1890 he wrote that Maurice Heany was delirious with fever and that Jameson was replacing Colquhoun as Administrator, after Colquhoun had written to Rhodes saying the firm of Johnson, Heany and Borrow was becoming too powerful and that the BSA Company should take steps to curb its commercial interests. This led to Colquhoun’s downfall; Rhodes described him as “a miserably weak man.” [BO P.844]

The firm of Johnson, Heany and Borrow began selling ox-wagons to purchase mining equipment and the BSA Company Police were used to will improve the Selous’ road to Umtali and beyond Chimoio to Fontesvilla, the highest navigable point on the Pungwe River with Johnson, Heany and Borrow supplying river transport. [BO P.847]

From Hartley Hills on 12 February 1891 Borrow wrote that flooded rivers had cut off the post and supply routes; that the police rations are: “reduced to meal, no coffee, tea, sugar or salt.” [BO P.857]

Difficult conditions in Mashonaland in 1891 / 1892

Johnson went with Jameson to find a cheaper transport route to Beira followed by Heany who worked on making an improved road. These projects cost money and took time and there were constant delays due to flooded rivers. Johnson did not blame anyone saying only: “Heany was drawing fast on our small capital.”

Rhodes proposed a scheme to reconstruct their firm and Borrow quoted Johnson’s letter to Heany of 11 February 1891 from Fort Tuli: “we are in a very weak state financially.” [BO P.868] as additional capital would be needed if they were to retain their leading position when the big Rand mining firms came up to Mashonaland.

This was the perfect opportunity for Rhodes who needed a hustler on the spot in Mashonaland. He had already decided that the Portuguese occupation of Manicaland and a route to the sea were too important to be left in the hands of Archibald Ross Colquhoun, the Administrator of Mashonaland. Johnson and Jameson were much better equipped to serve the interests of the BSA Company than an ex-civil servant, who was also a personal friend of Sir Henry Loch.

Colquhoun believed he was the key figure in Mashonaland; but in fact, Jameson was the authentic representative of the BSA Company. It was a deceitful arrangement which placed Colquhoun in an impossible situation and naturally the reality could not be explained to him. The first sign of trouble came when a letter from Rutherfoord Harris reached Colquhoun as the Pioneer Column left Fort Victoria in August and informed him that Jameson and Selous were to accompany him in his negotiations with Chief Mutasa in Manicaland. Things went downhill from there on and in September Colquhoun was writing to Harris: “I have written to Rhodes regarding a certain amount of friction which has occurred in connection with the conduct of the Manica mission between myself and Jameson. Your writing to Jameson suggestions and quasi-instructions direct was very irregular and unfortunate, and I have been compelled to tell Rhodes so. It has undermined my authority and Jameson has not cooperated with me as I hoped he would.”

On 4 October a telegram from Harris to Colonel Pennefather said: “I have to urge upon you that…you should at once proceed yourself with HQ staff and occupy the whole of the Manica country” and ended ominously: “It is not necessary to repeat all this to Colquhoun.”

Jameson deliberately stood aloof from all the administration detail of running Mashonaland, and with no trained staff and surveyors and a lack of supplies due to the heavy rains, Colquhoun had to battle on trying to set up some sort of administration of the mining law and to sort out the Pioneer claims and boundary surveys. No wonder that Colquhoun found himself condemned as a petty bureaucrat, “obsessed with rules and regulations.”

By January 1891, the firm of Johnson, Heany and Borrow had serious cash flow problems; with only £4,480 in the bank, they had commitments of £4,500 for a shallow draught sternwheeler to be named the Crocodile, £700 for equipment, £8,000 to replace the oxen lost in the rinderpest and an estimated £4,000 for stores and wharfs at Fontesvilla on the Pungwe River.

However, Frank Johnson, always the great showman has a different take on the situation. “He [Rhodes] knew, of course, that our firm of Johnson, Heany and Borrow was the only firm, company, or individual in Mashonaland which had any capital worth mentioning. We were practically alone in carrying out any serious mining developments, and I think I am not far out in saying that we were, as far as liquid cash was concerned, about ninety-five per cent of the country. At one time we held no less than one-fourth of the total number of registered gold claims in Mashonaland, besides a large area of farming land and a number of town stands. At one time, the whole future of the Chartered Company, which by now had become a favourite gambling counter on the London Stock Exchange, depended on what was found as a result of developing the gold lodes in Mashonaland” [FJ P.195]

With uncanny foresight Rhodes called on Johnson in his office in Cape Town wanting to know the state of the firm’s financial situation and as Johnson wrote: “he was afraid our ideas were bigger than our bank balance” [BO P.868] and suggested that Goldfields of South Africa, of which he and Rudd were joint managing directors, make a cash injection of £50,000 and take one third of the equity in Messrs. Johnson, Heany and Borrow.

F. Johnson and Co. Ltd

But the lawyers suggested a better solution would be to form a new company, F. Johnson and Co. Ltd with Rhodes subscribing £100,000 and being appointed Chairman and another £100,000 to be taken up by Johnson, Heany and Borrow in fully paid-up shares. However, when Rhodes produced an agreement for the sale of the assets of Messrs. Johnson, Heany and Borrow to the new company, Johnson said he could not sign without the consent of his partners. Johnson had a power of attorney in his safe, but procrastinated until 7 April when Jameson told him that if there were any more delays ‘the deal would be off’ and Rudd told Johnson: “don’t play the humbug anymore Johnson, trot out that power as long as my arm that Heany and Borrow gave you.” [JO 4/2/1] The new company had plant to the value of £30,000 mainly in the form of oxen and wagons, 1,000 of the most valuable gold claims in Mashonaland and about 100,000 acres of the best farmland,

In Salisbury Borrow was finding Colquhoun equally difficult on the question of land rights as Colquhoun had written to Harris: “Johnson also proposes to take up the best situated farm lands round the township or townships, and he seemingly has led his men to believe they can do what they like in the matter…I shall not permit anything of this character, unless I get definite instructions.” [CT 1/1/1]

The Rudd Concession had not given the BSA Company the power to grant land rights, although the Pioneers had been promised farms. Therefore Colquhoun had to accept that farms would be assigned initially without title, on the belief that ownership would be ratified once a political settlement was reached, but despite conceding the legal point, Colquhoun was now set on a collision course with Messrs. Johnson, Heany and Borrow.

The fact that Jameson, ‘Rhodes’ man in Mashonaland’ did not overrule Colquhoun was because Jameson did not enjoy ‘administrative detail’ and so Colquhoun’s exit was being merely delayed. Johnson wrote: “Let Colquhoun do his best and be dammed to him, I have thoroughly arranged the whole land question with Rhodes and Jameson with the result that Jameson immediately on his return to Mashonaland will give us provisional titles for the whole of the land to which we were entitled under the contract as well as those farms which we have acquired by subsequent purchase. They have decided not to press Lobengula at present in regard to the settlement, but will issue provisional titles which for the time being are all that could possibly be required or expected.” [BO P.794]

Lobengula who had been reassured by the Rev Charles Helm that: “the grantees…promised that they would not bring more than ten white men to work in this country” [BO P.238] tried to divide the Europeans by granting E.R. Renny-Tailyour the right to issue titles to land throughout his country. However, £30,000 and a block of BSA Company shares enabled Rhodes to circumvent this problem.

However, as Robert Cary puts it, “Mashonaland in 1891 and 1892 was not a viable proposition.” [RC P168) Gold mining returns were minimal as there was little processing plant, agriculture was in early stages and all supplies had to be hauled hundreds of kilometres making them exceptionally expensive. The BSA Company was in a poor financial situation through debt and its cheques required a De Beers guarantee; F. Johnson and Co. Ltd was also experiencing serious cash flow problems.

In addition, investors had been tricked and were in no mood to invest further. Many initial investors believed the BSA Company owned the Rudd Concession, but in fact it was owned by the Central Search Organisation; which in 1890 changed to the United Concessions Company, and assigned its rights in the Rudd Concession to the BSA Company in return for half the net profits. In 1891 the United Concessions Company was bought by the BSA Company for one million newly issued shares and the existing shareholders were furious, regarding these transactions as a barefaced swindle.

Life in Mashonaland in 1891

The first post for three months arrived at the Ranche on 6 April 1891. [BO P.904]

In the same month rinderpest and east coast fever meant horses were dying and oxen were scarce [BO P.909] and the Portuguese affair seemed likely to sabotage plans for an east coast route [BO P.914] By 6 May 1891 Frank Johnson and his party have been turned back from travelling up the Pungwe River [BO P.921] In a letter dated 26 May 1891 Borrow wrote of Captain Heyman’s skirmish with the Portuguese at Macequece and how he rode down to Manicaland to: “have a fling-in” but arrived too late. [BO P.927]

By June: “wagons are rolling in like mad” [BO P.935] and there was considerable new development work in the field and McWilliams, the mining expert, was cautiously impressed with prospects at Hartley Hills; Heany’s road down to the Pungwe would soon be in use, but only suitable for the dry season, and there were many passengers waiting to enter Manicaland at M’pandas, but the tsetse fly were a problem. [BO P.945]

Borrow calculated his worth at £46,300 and in September 1891 he wrote from the Ranche that he has asked Johnson to sell his shares in Frank Johnson and Co; but as this was not done, and he asked Langerman (his representative on the Board) to do so: “Rhodes and Rudd will be annoyed” [BO P.964]

Lord Randolph’s visit to Mashonaland

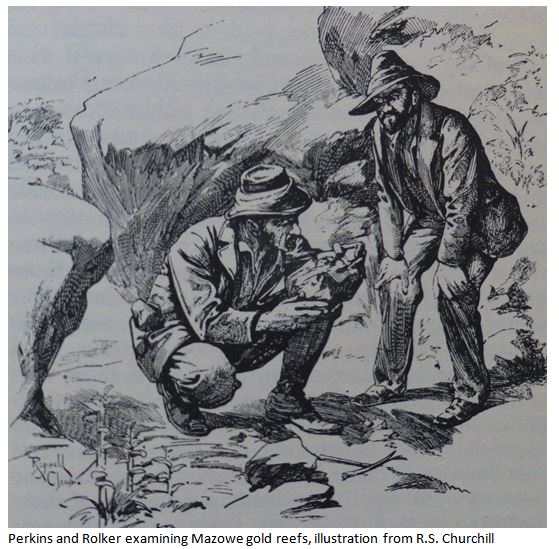

A number of mining experts came up to assess Mashonaland’s gold prospects. They included McWilliams, John Hays Hammond, H.C. Perkins and Rolker. McWilliams in 1891 and then Hammond were both cautious about future mining prospects, but Perkins, Churchill’s mining expert, declared only small workers could make a profit from the gold reefs he had observed.

Borrow tried to be a good host to the Churchill party, by providing transport and accompanying them on their trips to Mazowe and Hartley Hills, where they commented on the shafts in the old gold workings and dated them from twenty to one hundred years old. [RSC P.240] At the Yellow Jacket mine, samples at the surface gave 60 oz. per ton, but were poor at the bottom of the shaft. This claim, together with the Jumbo and Golden Quarry all belonged to Messrs Johnson, Heany and Borrow. Perkins’ conclusion was all the reefs were of the same character; extending along the surface for considerable distances, but pinching out and losing their gold at depth. Churchill wrote to his Graphic readers: “here the actual crushing, by a small three-stamp battery, of twenty tons of ore, gave the excellent result of ninety-five ounces of gold. The “Golden Quarry” however, was soon found to be no reef at all, but only a “blow out” or, in other words, a large bunch of quartz which would be rapidly worked out. I should doubt whether, in the history of gold-mining, two more attractive, more deceiving; more disappointing reefs have ever been found than these two which I have written about.” [RSC P.297]

Borrow observed: “the experts have been rather rough on the country after having…only seen a very small portion of it.” [BO P.970] He wrote: “We have kept Lord Randy quiet by putting him into a syndicate up here of which he has given me full charge.” [BO P.971] But Perkins advice to Borrow was to get out of mining in Mashonaland.

Lord Randolph Churchill was extremely complementary about Messrs Johnson, Heany and Borrow’s “Ranche” describing it as “the most important and conspicuous in the settlement…the whole place is maintained in a condition of extreme cleanliness and order, and may truthfully be described as a homestead which would be respectable in England and princely in Ireland.” [RSC P.282-3] and later: “The settlement in this country of the three acute and enterprising partners who compose the firm alluded to above has been a fortunate circumstance for the Chartered Company…I cannot refrain from the observation that in a new country such as this, where one is compelled at times to notice overmuch apathy, sluggishness, unreasonable discontent, and scandalous waste of money, this firm has set a bright example of active perseverance, of intelligent and economical outlay, which encourages the formation of hopeful views of Mashonaland.”

Much of the praise was due to Borrow. As Darter states: “we were wont to say…that Heany [sic] did the thinking, Johnson the talking and Borrow the work. “ [AD P.33]

Mashonaland in 1892

On 26 November 1891 from Fort Victoria Borrow wrote to his father saying the BSA Company was cutting expenses and had reduced the Police force, and that amaNdebele raids on the Mashona had increased. [BO P.1007]

To his mother he wrote he had an enjoyable Christmas week in which he won a horse race [BO P.1025] that the Alice reef looked profitable; and that the mining engineer McWilliams wrote a satisfactory report on Mashonaland’s prospects, but that Rolker was less enthusiastic. [BO P.1028]

On 11 December C.D. Rudd wrote to Borrow that everyone was depressed by Lord Churchill’s less than bright reports on Mashonaland, the BSA Company would probably not be able to afford a railway to Beira and that it will probably take three or four years, rather than one year, to get the country on its feet. [BO P.1034]

On 5 February Rudd wrote again to Borrow saying: “it is a matter of keeping expenses at an actual minimum until something turns up” and that Dutch farmers, hunters and people returning to the country should give Mashonaland a boost during the year; but little capital would flow in and negotiations with the Portuguese and other technical difficulties were holding up the railway to Beira. [BO P.1044]

On 27 May to his father he said he had visited various mines at Hartley with Jameson, Tyndale-Biscoe and Hoste, the graves of those who died at Salisbury in 1890 have been dug up and buried in a new cemetery, and enclosed a programme from the Mashonaland Turf Club on 24 May 1892. [BO P.1081]

From Hartley Hills he told his father he had lost £600 because of delays in selling his BSA Company shares, [BO P.1088] and to his mother that they were shooting lions using donkeys as live bait; that Rudd was more interested in the BSA Company than Rhodes who: “is such peculiar man one never knows what he really thinks.” [BO P.1093]

Borrow continued to work hard: “Today is Sunday, but it makes very little difference – we cannot afford to stop the mill.” [BO P.1110] He was building the dam at Borrowdale, serving on the city sanitary board as a nominee of the BSA Company, and as an officer in the local volunteer force, the Mashonaland Horse. To his father he wrote: “We are all gamblers here…We (three)…have played a bit higher than anyone else for we have played not for competency, but for a big fortune. Well! The ace turned up at the wrong time and beat us…I suppose I ought to feel sorry for myself, but really I can’t, the game was quite worth the candle.” [BO P.1009-10]

In a letter to his mother dated 4 September he told her during race week his horses won £499; they were imported only in July at a cost of £523 and that he was crushing five tons of quartz at the Umfuli River; he and O.G. Williams were to be joint managers of the Churchill Prospecting Syndicate and hoped this interest would not clash with his interests in Frank Johnson and Co. [BO P.1133]

On 24 October he wrote that the Beatrice Mine is down to 60 feet and looked very promising; the Rhodesia herald will be published soon, but: “the poor Editor seems quite weighed down by all his responsibilities” and that he [Borrow] can always get what he wants put in the newspaper. [BO P.1138]

Mashonaland in 1893

In January 1893 Borrow travelled on leave to England for six months with John Spreckley and assisted in the flotation of the Mashonaland Gold Mining Company, in which he became a Director. Jack Spreckley who had resigned as mining commissioner at Sinoia (Chinhoyi) no doubt met Beatrice Borrow at this time and on 31 August 1895; Spreckley married Beatrice at St John the Baptist church in Bulawayo when he was general manager of Willoughby’s Consolidated.

In June 1893 he wrote from Johannesburg enroute that: “Mashonaland seems to be pretty well thought of here now.”

On his return Borrow became engaged to Lucy Drake, whose sister Ella was the wife of the public prosecutor, Alfred Caldecott, and was appointed managing director of Frank Johnson and Co. Ltd in July 1893 and built a brick house overlooking the dam at Borrowdale.

By now, even Borrow no longer hero-worshipped his partners and wrote about one of Johnson’s projects: “Johnson is a wonderful man, I wired him that I expected…to spend my wet season in prison at Salisbury for fraudulent insolvency.” [BO P.1106]

The 1893 Matabele War Campaign

From the Ranche on 27 August he wrote to his mother that they would leave for Matabeleland on 5 September: “I think we shall come through pretty well, of course we do not expect a walkover.” [BO P.1164]

Borrow’s letter of 4 September says: “Tomorrow we leave for what I look upon as a somewhat risky enterprise, viz the subjection of the Matabele. I think as we probably all do that we shall be entirely successful, still I cannot help thinking that a great number of us will in all probability never return, I have not made a will but I have left a note leaving, with a few exceptions, all my personal effects to father. I estimate my estate as being worth about £17,000…” [BO P.1166]

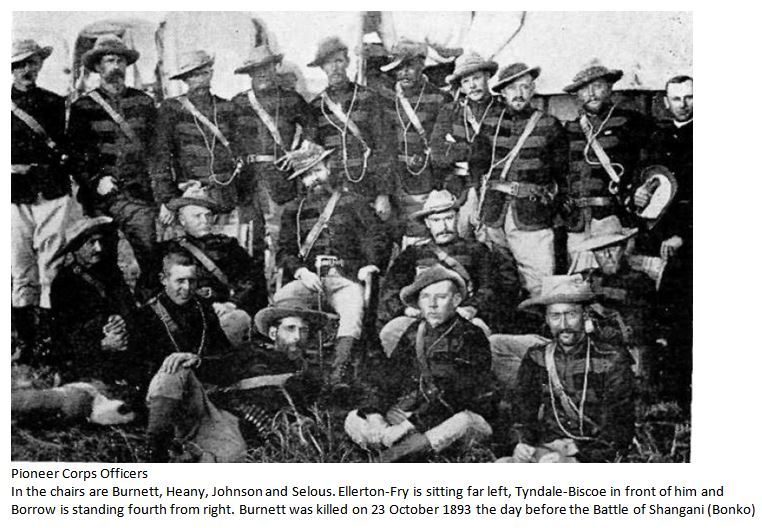

Borrow commanded a troop of the local volunteer force (the Mashonaland Horse) and in August 1893, he was appointed in command of “B” Troop of the Salisbury Horse; Maurice Heany commanded “A” troop and Jack Spreckley commanded “C” Troop.

Borrow wrote to the The Times of London on 4 October reporting they had a tedious and annoying wait at Fort Charter with much drilling, the horses came late with little time to break them in, although they were better than expected having been said to cost £50 each. Four amaNdebele Maholi who escaped reported that Matabeleland was in a state of alarm, that the young warriors wanted war, but their elders hoped for peace. They said Lobengula was at his cattle post at Umvutcha; cattle were being removed from koBulawayo, three regiments had been sent to Fort Victoria and there was an outbreak of smallpox in Matabeleland. On 30 September Jameson arrived at Fort Charter with Sir John Willoughby; the men paraded, and then demonstrated their methods of skirmishing and pursuing the enemy before Jameson made a speech to the men. Borrow added details on the strength of the Salisbury, Victoria and Tuli Columns and the possible role of the Bechuanaland Border Police, described the fortifications at Salisbury, Victoria and Tuli and stated the affair had cost the BSA Company £50,000 to date. [BO P.1181]

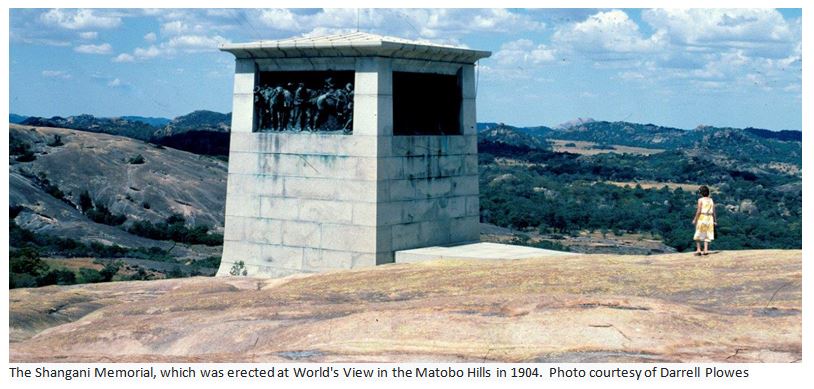

Borrow fought at the battles of Shangani and Bembesi (called Bonko and Egodade by the amaNdebele) taking a prominent part in all the engagements. He was lucky not to be ambushed at Shangani when he returned after dark after burning kraals and capturing cattle and he took a patrol in search of Capt. Williams after the battle. [W&C P.244] In the Memoirs of D.G. Gisborne: Occupation of Matabeleland 1893 in Rhodesiana No 18, Gisborne records in his diary on 31 October 1893 that Henry Borrow was the ‘hero of the day’ at the battle of Bembesi.

The horses were being brought in from the south after watering when the amaNdebele attacked in strength after midday, concentrating on the northern end of the laager which housed the Salisbury volunteers. Frightened by gunfire and by their grooms rushing forward to turn them in, the horses bolted towards the west and some of the amaNdebele. Borrow ran to the centre of the laager and mounted one of the few horses within the lines and together with Sir John Willoughby by “galloping out of the laager pluckily turned the horses in the direction of safety which lay in the valley stretching out toward the Victorian laager.” [GDG] Major Forbes states: “the stampeding horses were only turned when within a hundred yards of the enemy, but not before both they and the relief party were exposed to a very heavy fire which, however, only killed one horse.” [W&C P.121]

Forty miles from Bulawayo, Borrow wrote to his mother saying he has sent the above report to The Times [it was not published] and: “if we can bring on a general engagement we shall soon flatten the Matabele, but if they break up in small parties it will of course be a matter of time” and that he expected to return to Salisbury after a few weeks. [BO P.1192]

On the morning of 3 November, near Ntabazinduna, Troopers Carey and Sibert, who had been wounded at the battle of Bembesi and subsequently died, were buried before the trek commenced. About midday, the trader James Fairbairn met the Columns and told them that Lobengula’s kraal was on fire and that Lobengula and his entourage had fled northwards. Later in the evening Borrow and twenty men of B Troop rode into the royal kraal at Bulawayo, and according to Oliver Ransford in his article White Man’s Camp, Bulawayo in Rhodesiana No 18; Fairbairn and Usher had decided to spend the night on the roof of Dawson’s store with their rifles and a pack of cards, as they considered this building the strongest and most fire-proof in white man’s camp. They felt a great sense of relief about 8pm when Borrow and his patrol rode in to scout the royal kraal. A contemporary account says: “they found them playing poker on the roof” and the two men and Borrow’s patrol spent the night in Dawson’s store.

Although the King’s royal kraal had been completely destroyed, Forbes writes that: “the Matabele had not interfered in any way with the houses belonging to the white men.” These were at “white man’s camp” which was 400 metres from Lobengula’s royal kraal and across the Amajoda stream.

Death of Henry Borrow

Borrow expected to remain in Bulawayo when Forbes and his force left in pursuit of Lobengula. “I think the Matabele business is nearly finished…we shall very soon be able to return to Salisbury…I shall probably be here for at least two weeks after the disbandment of the corps as I want to arrange for the purchase of farms, claims, etc. on behalf of Hirsch & Co. I expect to make some money from them.” [BO P.1194]