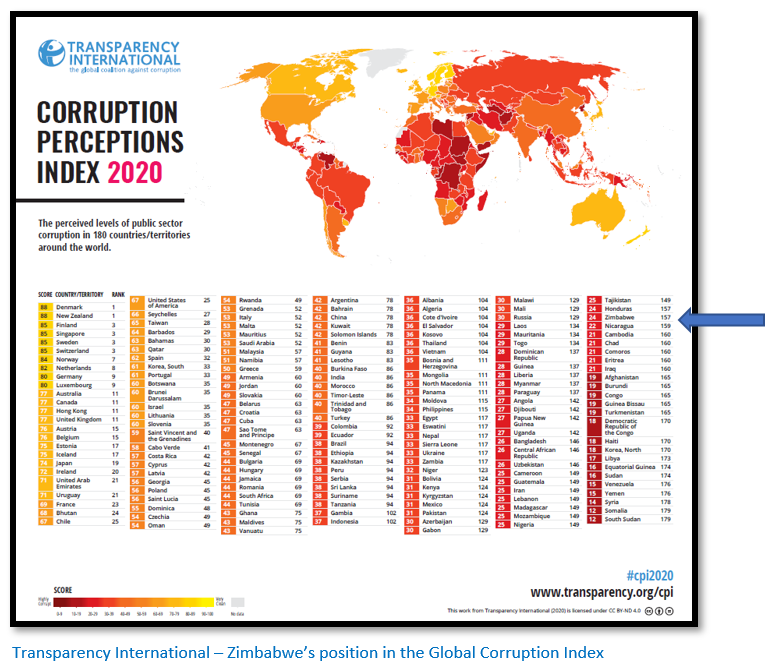

Corruption in Zimbabwe - Transparency International reveals the latest Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) for 2020

The organisation ranks 180 countries by how corrupt their public sector is perceived to be. The scores are made by experts and business people, not the general public. In overall terms the 2020 report found that more than two-thirds of countries had scores below 50 showing perceived high levels of public sector corruption.

Transparency International believes that in 2020-21 the Covoid-19 pandemic has undermined both public health and democracy. Many of the measures during the pandemic taken by autocratic regimes in Africa and elsewhere, including Zimbabwe, lacked transparency, restricted civil rights of their citizens and prioritised the private interests of corrupt officials and politicians over the rights of its citizens.

Whichever way you look at it, things are not going well as far as Zimbabwe’s international image is concerned. In Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index Zimbabwe is ranked 157 out of 180 countries…this is not a score that any Zimbabwean should be proud of…it is in the worst fifteen percent of corrupt world nations!

Globally

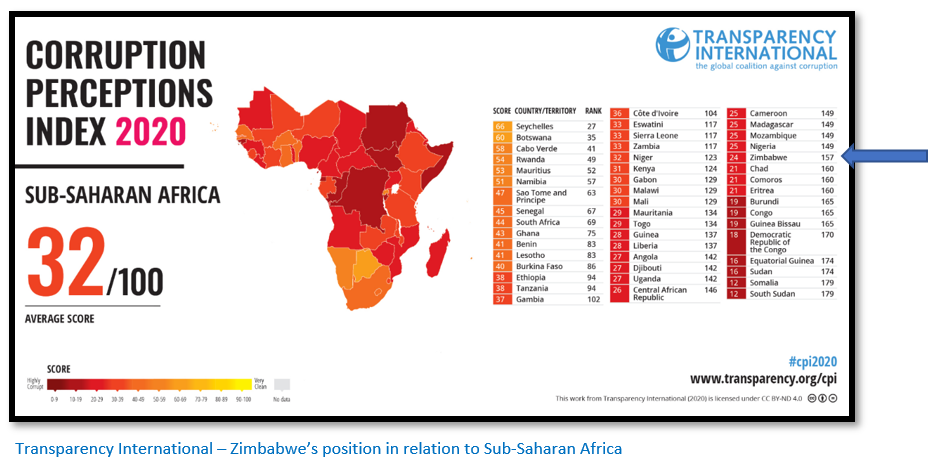

Sub-Saharan Africa

If we narrow the focus down to just Sub-Saharan Countries, the situation does not get much better! Zimbabwe remains in the bottom third, so even by the standards of our neighbours, things are looking pretty grim.

Of the 49 countries assessed in Sub-Saharan Africa, the average score was 32/100, with Zimbabwe on 24/100 and near the bottom of the class! In fact, 38/49 and barely above some of the most corrupt regimes in the world, such as DRC and Equatorial Africa.

There were some improving African countries

Côte d'Ivoire and Senegal improved 9 places, Angola 8 places, Tanzania 7 places.

Significant declining African countries

Liberia declined 10 places, Congo, Madagascar and Malawi 7 places, Mozambique 6 places and Zambia 5 places.

How Countries are scored

Transparency International uses a Corruption Perception Index (CPI) which scores 180 countries and territories by their perceived levels of public sector corruption; a score of 100 would be very clean and 0 would be highly corrupt. The highest scoring country was Denmark with a score of 88; the UK was joint eleventh with Australia, Canada and Hong Kong, the worst were Venezuela and Yemen (15) Syria (14) and Somalia and South Sudan joint last (12)

How the data is collected

The data for collecting the CPI comes from a number of sources comprised of thirteen datasets - Transparency International is not involved in its collection. The data comes from:

- The World Bank

- The World Economic Forum

- Private Risk and Consulting Companies

- Think Tanks

Each of the thirteen datasets rates countries according to its own scales and each score is transformed from its original scale into “standardised values” which show the position of each country relative to the others. The average score is the CPI value for each country.

A minimum of three sources of data are required for each country…that’s why not every country in the world is included. The year 2012 is the baseline.

What do the thirteen datasets cover?

They all measure various aspects of corruption in the public sector including:

- Bribery

- Diversion of public funds

- Effective prosecution of corruption cases

- Adequate legal frameworks

- Access to information

- Legal protection for whistle-blowers, journalists and investigators

Carefully designed questionnaires are sent to the country-expert sources listed above who assign values on each of the aspects of a country’s corruption they are familiar with – these often correlate with citizen’s own reports of bribery. To ensure reliability the CPI is regularly reviewed by independent evaluators.

But the datasets do not cover

- Tax fraud

- Money laundering

- Financial secrecy

- Illicit flows of money

Does the CPI reflect actual levels of corruption?

Transparency International explains that corruption generally involves illegal activities which are deliberately hidden and only become public knowledge when they come to light through scandals, investigations or public prosecutions. Research has been carried out in measuring corruption, but at present there is no available index that measures corruption in all its different guises.

Internationally the CPI is the most relied upon corruption indicator

Due to its wide international coverage and the reliability which comes from using a variety of data sources and that it reconciles different points of view on what actually constitutes corruption, the CPI is the most widely recognised indicator of public sector corruption.

Delia Ferreira Rubio Chair of Transparency International said: “COVID-19 is not just a health and economic crisis. It is a corruption crisis. And one that we are currently failing to manage. The past year has tested governments like no other in memory, and those with higher levels of corruption have been less able to meet the challenge. But even those at the top of the CPI must urgently address their role in perpetuating corruption at home and abroad.”

How much better do Zimbabwe’s immediate neighbours do?

As can be seen in the table most do a lot better and little positive can be gained from Zimbabwe’s position third from the bottom!

Corruption cases in Zimbabwe

On the 19 June 2020 former Zimbabwean Minister of Health and Child Care Obadiah Moyo was charged with corruption in connection with the awarding of a $60 million contract for Covid-19 medical supplies and was sacked by Emmerson Mnangagwa for inappropriate conduct by a public official.

Moyo has been arrested and charged with criminal abuse of office. According to court papers, Moyo allegedly awarded the contract to Drax International LLC, headquartered in the United Arab Emirates, which was concluded without the consent of the Procurement Regulatory Authority of Zimbabwe and allegedly sold supplies to the government at inflated prices.

The Zimbabwean government has been criticised for failing to deal with corruption at a time when the country is in desperate need of an international bailout package to save the economy from collapse.

Now out on bail of $50,000 will this ZANU-PF stalwart who has run for Parliament unsuccessfully on several occasions ever be brought to trial?

Another corruption case which this website has already reported upon was the case of Henrietta Rushwaya, niece of President Emerson Mnangagwa, former head of Zimbabwe Miners Federation and previously a member of ZANU-PF’s ‘untouchable’ elite [See the article Rushwaya gold-smuggling case exposes a microcosm of the corruption that exists in Zimbabwe today under Midlands on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Rushwaya was granted $100,000 bail by a Harare Magistrate who also ordered her to surrender all her travel documents, not to leave her home between 8 pm and 6 am, and not to go within 80km of any of the country’s borders.

The Magistrate’s actions look well-considered and correct, but Rushwaya is jointly charged with Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) operatives Steven Tserayi and Raphios Mufandauya, Gold dealer Ali Mohamad and Gift Karanda.

The gold trade is without doubt Zimbabwe’s most profitable illicit activity and many of the ZANU-PF bigwigs and politicians are entangled up in its murky dealings which this website has previously written about [See the article Zimbabwe’s artisanal miner’s, popularly known as makorokoza, risk their lives to make a decent living under Midlands Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Will the defendants be brought to trial in due course, or will their political connections ensure that this case is quietly dropped, and corruption allowed to win once again, so confirming Zimbabwe’s current position at 157/180 in the Corruption Perception Index?

References

2020 – CPI – Transparency.org – Transparency International; https://www.transparency.org › cpi

Nyasha Chingono. 9 Jul 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/jul/09/zimbabwe-heal...