Contemporary criticism of the British South Africa Company (BSAC) in 1889 – 90 from Henry Labouchère the editor of the journal Truth

Introduction

This article is largely based on Eleanor Mabin’s thesis for an MA at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, Canada published in 1982. Labouchère was a Member of Parliament from 1880 to 1906 and concerned with the issues of abuse of office and the limiting of imperial expansion. Therefore it is not surprising that the British South Africa Company and particularly Rhodes, who filled the dual roles of politician and capitalist, were often the subject of his attention in the journal he founded and edited named Truth. British politicians and imperial officials were all of interest to him, as were the Chartered Company’s directors.

I have interchanged the terms Labouchère and the journal Truth as Henry Labouchère was founder and editor of the journal and also BSAC and Chartered Company.

Truth’s general theme

Mabin writes that the general theme of the articles in Truth was to demonstrate to its readers that the BSAC made no serious attempt, before the Jameson Raid in late 1895 attracted the Imperial Government’s attention, to develop an effective administration or the infrastructure necessary to develop Mashonaland and Matabeleland as a colonial settlement. The articles showed:

- That the BSAC was not a viable commercial proposition

- The BSAC did not take the responsibility of governing its territory very seriously.

He used these points to warn potential settlers off and potential shareholders against holding BSAC shares and attempted to convince the Imperial Government that the Chartered Company was not fit to govern the territory.

Henry Labouchère’s arguments raised in the journal Truth in 1889-90

These were that:

- As a commercial Company the British South Africa Company (BSAC) managed to persuade the Imperial Government to grant it a royal charter and support the Company’s undertakings.

- That the BSAC was a speculative venture which had an appearance of respectability granted to it by the royal charter with which it was awarded and which in turn persuaded shareholders to invest in its shares without any realistic prospects of success.

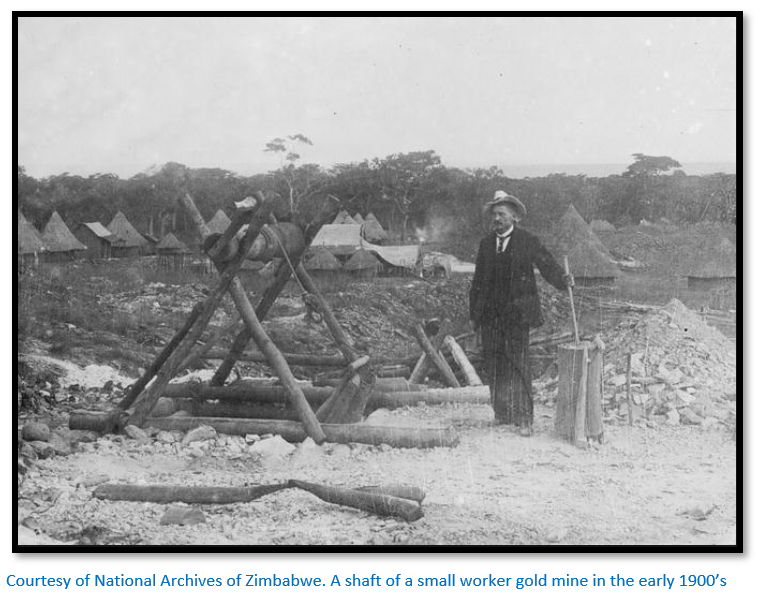

- The BSAC’s prospects of success depended entirely on finding commercial gold ventures in Mashonaland and when these did not materialise the Company invaded neighbouring territory in the hope of new gold finds and to support the Company’s declining share price.

- Those neighbouring territories included Manicaland in 1890-91, Matabeleland in 1893 and the Jameson raid into the Transvaal Republic in 1895-96.

- He believed Rhodes was foremost a financier and a power-monger and all the activities of the BSAC were directed not at enriching the Empire, but at enriching Rhodes and his colleagues.

- Rhodes displayed a complete disregard for legality and due process evidenced in his actions toward the administration of Mashonaland.

- Rhodes ambitions far exceeded the BSAC’s resources.

However in Labouchère’s view the Imperial Government also bore responsibility in that:

- It chose to use a Chartered Company to expand its territories in order to save money but failed to implement control over the BSAC for the same reason.

- Further than failing to exercise control, many of the colonial office officials actively assisted Rhodes in his objectives and were rewarded for this.

A further area of concern for Labouchère was that:

- The rights of Mashona and amaNdebele were effectively ignored and neither were awarded any respect. He evidenced this in the Pioneer Column entering Mashonaland despite Lobengula’s protests and the 1893 War on the amaNdebele.

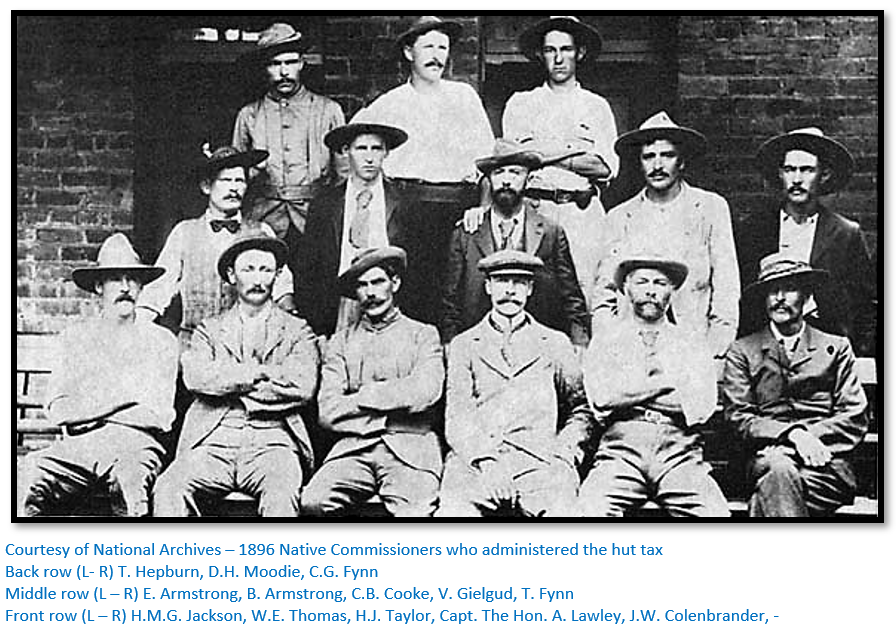

- The imposition of a hut tax of ten shillings per hut in Mashonaland in 1894 despite the fact they were living on their own land.

Labouchère’s views of the BSAC

These are summarised as follows: “That the Company originated as a venture in financial speculation which was facilitated by the Royal Charter granted by the British Government and by the presence of two Dukes on its Board of Directors; that only a small part of the nominated capital of the Company represented cash, while the promoters secretly retained special rights to themselves, then sold shares to unsuspecting investors; that the only asset of the Company was a mineral concession in Mashonaland, that it rapidly became obvious that Mashonaland did not contain gold and so, in order to keep the Company afloat, Rhodes embarked on a series of raids, annexing more land to the country’s territory, to stimulate new confidence in investors; that the first raid was into Portuguese territory and it was only partially successful, as the Company did secure part of Manicaland, but failed to get Beira, which was its objective; that in 1893 the finances of the Company were in a desperate state, so the Company mounted its next expedition – this time against Lobengula – which operation was successful, both in joining Matabeleland and in boosting the value of shares on the Stock Exchange; that Matabeleland did not yield paying gold either and so, in 1895, Rhodes embarked on the boldest raid of all – against the South African Republic which had already proven its value.”

The BSAC and Cecil Rhodes

According to Labouchère the entire edifice was propped up by Cecil Rhodes, then Prime Minister of the Cape Colony and Chairman of De Beers and Gold Fields of South Africa and Managing Director of the BSAC.

However Eleanor Mabin says his attacks on Rhodes were not personally directed against his character: “I should be sorry were Rhodes seriously ill. I have always made a distinction in my mind between him and the financiers with whom he threw in his lot. Had he merely used them to carry out his Imperial dreams, without sharing in the loot, I should have had a higher opinion of him…” but more on his powers as managing director with a power of attorney for all the directors of the BSAC.

Also on Rhodes capacity as Prime minister of the Cape Colony whilst also being a director of De Beers, Gold Fields of South Africa and the Chartered Company. Labouchère believed there was a conflict of interest, just one example being the Mafeking Railway extension: “In the event of Mr Cecil Rhodes, as managing director of the South Africa Company, failing to divide the first 6,000 [square] miles of land with the Cape Government, it falls to Mr Cecil Rhodes, as Premier of Cape Colony, to compel specific performance of the agreement. In the event of the railway extension to Mafeking not being carried out (and a proposal that a line should be constructed in lieu of it from Bloemfontein to Kimberley has been publicly made by Mr Rhodes’ chief colleague in the directorate of the De Beers Consolidated Mines) it will fall to Mr Cecil Rhodes, adviser to the Governor of British Bechuanaland, to recommend that Mr Cecil Rhodes, private gentleman, be compelled to re-transfer the 6,000 square miles already transferred to him…”

The BSAC’s shares and shareholdings

Labouchère was very interested in the inter-locking boards of directors and shareholdings between the various companies as he believed their promoters were engaged in questionable dealings to deceive the colonial office and the public regarding the financial weakness of the BSAC.

| Directorships | |||||

| BSAC | Central Search Association | United Concessions Company | Exploring Company | De Beers | Goldfields of South Africa |

| Rhodes | Rhodes | Rhodes | Rhodes | Rhodes | Rhodes |

| Beit | Beit | Beit | Beit | Beit | |

| Gifford | Gifford | Gifford | Gifford | ||

| Cawston | Cawston | Cawston | Cawston | ||

| Rudd | Rudd | Rudd | Rudd | ||

His specific concern were:

- Rhodes and his fellow directors exploited the appearance of respectability given to the BSAC by its royal charter in order to defraud British investors,

- The boards of director’s between all BSAC and all of Rhodes’ companies were inter-related and that there were secret agreements between them,

- Rhodes and his associates inflated the value of their shares although they lacked real assets creating opportunities to profit on speculation and by awarding shares to influential people to buy their support.

He maintained that despite any real prospects of a “second rand” the BSAC put out sufficient propaganda “puffing” to bolster the value of their own shares which he stated was financial trickery. In December 1891 he published a letter from an experienced miner who stated he had spent over a year in Manicaland and Mashonaland dispelling the rumours of gold: “my own firm conviction is that were one ten-stamp battery at work for six months on any one of the many reefs I have visited and examined, the claims and pretensions of Mashonaland to being a gold-producing country would be ruthlessly dispelled.”

In October 1893 he quoted from a speech made by Rhodes in Salisbury who said: “Mashonaland is equal in size to France and its sparse population has pegged out 400 miles of gold bearing claims.” Labouchère responded that he had: “never doubted that there is gold in Mashonaland and I have no doubt that the sparse but speculative population has pegged out many claims. What I have denied is that the gold is in such paying quantities that these claims can be worked so as to cover any interest on outlay, sale price to British investors, and the royalty of fifty per cent on profits claimed by the Company…Mr Rhodes seems to forget that the ‘puffs’ of Matabeleland have already commenced and that we are already being told that its gold reefs are richer than the Mashonaland reefs.”

In a letter to the BSAC director Lord Gifford he posed three questions:

- What are the assets of the United Concessions Company?

- How property only alleged to be worth £121,000 last year [the share capital of the Central Search Association] can now be worth £4,000,000?

- Why the conversion of the Central Search Association with a capital of £121,000 into the United Concessions Company of £4,000,000 took place at a cost of £4,000 for registration?

The Exploring Company held 29,400 shares or 24.5% of the initial Central Search Association nominal capital of £120,000. When the United Concessions Company was formed with a nominal capital of £4,000,000, the Exploring Company’s share was 30% and they also held 25,000 fully-paid shares in the BSAC and 50,000 shares on which three shillings had been paid. How had this all come about? Was it because of the directors of the Exploring Company – Gifford, Cawston, Rhodes, Beit and Maund, all except Maund were also directors in the BSAC?

Lord Gifford never responded but a letter dated 15 January 1891 from “one who knows” stated the relationship between the United Concessions Company and the BSAC is that: “…of landlord and tenant, though it will not be forgotten that here the tenant has powers far larger than could be given ordinarily by a landlord to his tenant – namely, to develop the Matabele Concession in its discretion, and where thought fit, to turn it to account by sale, lease or in any other way.” Finally any relationship between the Chartered Company and either Gold Fields of South Africa or the Exploring Company beyond the fact that those companies were shareholders in the United Concessions Company was denied.

In 1891, the responses from the BSAC seemed plausible; but in 1893 the shares of the United Concessions Company, then considerably below par, were exchanged for BSAC shares of much greater value. Nor did they explain why ownership of the Rudd concession was not vested in the BSAC despite the fact that the owners of the Rudd concession were also directors of the BSAC?

How influential people were “squared” with Company shares

Labouchère returned to this theme several times. In the case of the Matabeleland Company versus the BSAC in July 1893 he noted Alfred Beit’s answers to several questions:

“Q: What was done with the 40,000 shares which there appears for distribution in South Africa?

A: 34,000 were distributed in England by me

Q: …distributed to whom?

A: Distributed to people who wanted to enter the Company at par

Q: They were not members of the Beit Syndicate?

A: They were given to people outside the Beit Syndicate who it was considered in the interest of the Company should be interested in the undertaking and also promises were made.”

No information on the recipients of the shares was given, but Labouchère states that: “almost everyone…who has puffed the Company and done the praise of its land of Goshen, is pecuniarily interested in the Company’s financial success, or rather in its shares going up in the markets.”

In October 1893 as the Salisbury and Victoria columns advanced into Matabeleland Truth called for investigation into the BSAC asking: “whether…important personages have been “squared” either with free shares or shares given at par when they could be sold at a premium. Let us know precisely what connection exists between Sir Henry Loch, the High Commissioner and the Company, on the Directors of which he is supposed to exercise a check, on behalf of the Imperial Government.”

At all times Labouchère was cautious in his allegations because he did not have access to the share registers. Mabin however quotes Maylam who found evidence that Sir Hercules Robinson, the High Commissioner, Newton the Colonial Secretary and Receiver-General in British Bechuanaland in 1889, General Carrington and Lt-Col. Goold-Adams of the Bechuanaland Border Police all held BSAC shares without the knowledge of the colonial office.

See also the bear sales of the directors during the course of the Jameson Raid when the value of BSAC shares were judged about to fall.

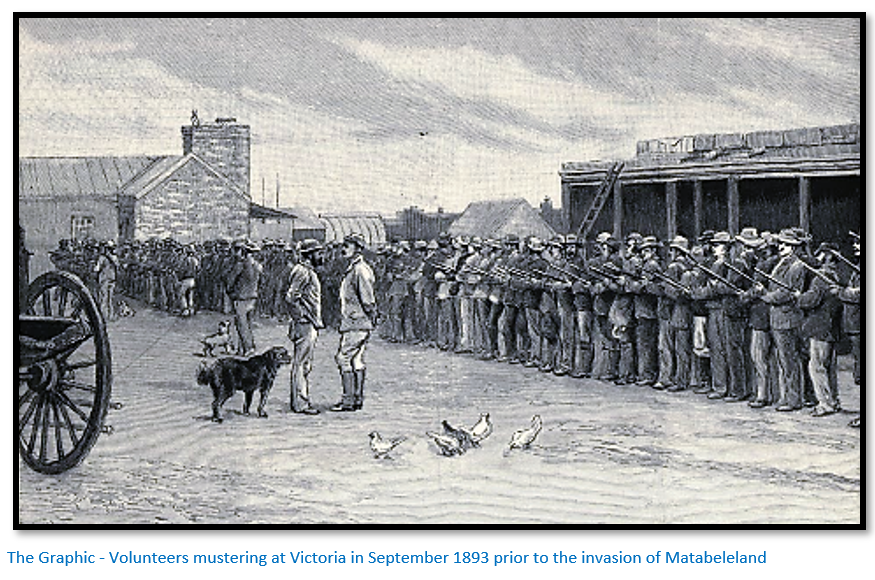

Conquest and settlement of Matabeleland 1893 – 1896

Labouchère was highly critical of the BSAC’s motives which he stated were the result of the Company’s near bankruptcy and the fact that Mashonaland had produced very little payable gold

and asserted that a war was created with Lobengula in order to invade Matabeleland and to revive confidence in BSAC share values on the London Stock Exchange.

As examples of the Company’s propaganda he reproduced a letter from the Pall Mall Gazette: “Lobengula and his people have the best country in South Africa in every way. They say it is even richer than the Transvaal in gold. At Bulawayo itself a missionary whom I know and who has lived in the country as long as any Englishman, has seen a reef of simply marvellous richness. On the latest map published by the Chartered Company you will see that they speak of the “banket” reef near Bulawayo…so you see there is something to fight for.”

Ranger considered that Rhodes and Jameson in 1890: “planned the eventual conquest of Matabeleland…but were happy to postpone it.” Once the minor incident at Victoria occurred, Jameson decided the right moment for war had arrived.

Labouchère thought the BSAC provoked the war and then ruthlessly seized amaNdebele land and cattle showing a complete disregard for their rights – an action in which the colonial office was happy to go along with. Initial amaNdebele raids against Mashona in 1891 to exact tribute and the killing of chief Lomagundi were accepted; Jameson commented they were: “in accordance with Lobengula’s laws and customs.”

In the July 1891 Victoria incident Lobengula gave advance warning to BSAC officials and the impi were given strict instructions not to interfere with Europeans which they obeyed. However Mashona servants appealed for protection and were taken into the fort at Victoria. The impi demanded their release and were told by Jameson to be over the border in Matabeleland within an hour. A patrol under Captain Lendy fired upon the impi; European feeling against the amaNdebele rose and Jameson decided to prepare for war. The colonial office needed to be convinced that action was necessary, but Sir Henry Loch agreed with BSAC directors that the amaNdebele needed to be conquered and both Mashonaland and Matabeleland brought under British control.

The amaNdebele were accused of building up their forces which Lobengula denied and was supported by John Moffat, the assistant commissioner in Bechuanaland, but these protests were ignored by Loch and the colonial office. Lobengula sent two deputations to Cape Town; the first was ignored, in the second two of the three izinDuna were killed by Bechuanaland Border Police.

The war was quickly over, Bulawayo captured and Lobengula fled northwards and died in January 1894. Negotiations between Rhodes, Loch and Lord Ripon, the colonial secretary resulted in the Matabeleland Order in Council of 18 July 1894 in which Matabeleland was recognised as British territory and the BSAC given the right to administer the territory.

Truth accused Rhodes and the colonial office of: “tricking the Matabele out of their country and independence, massacring by the hundred with machine-guns, robbing them of whatever they possessed worth stealing, driving them into revolt by sheer despair, and finally subduing them after a bloody war”

Land and Cattle

The Order strove to protect the rights of the defeated amaNdebele by appointing a Commission to oversee the redistribution of land and cattle, but the BSAC were not supervised by the colonial office and the amaNdebele were ruthlessly stripped of their land and cattle by Jameson who had promised too much land to the volunteers during the Matabele War and virtually one hundred kilometres of land around Bulawayo was redistributed. Jameson completed outfoxed the Land Commission.

Labouchère’s assertions that the war was about supporting the BSAC’s share values proved correct allowing new shares and debentures to be issued.

The lack of control over the BSAC

Another of Labouchère’s concerns which worried him was Britain’s responsibility for a commercial business with vast powers over which the Government had so little effective control. He had grave moral doubts about Chartered companies: “From the very first I have protested against (these) expeditions into the interior of Africa got up by Chartered companies. In every case they are marauding expeditions made for the benefit of speculators. What has civilisation gained through the raid through Africa after Emin and his ivory? What is civilisation likely to gain by the advance through Matabeleland and Mashonaland with the avowed purpose of seeking whether gold can be found there, or whether fools can be found in England to put money in the pockets of promoters on the chance of its being found?”

He understood the British Government was willing to use Chartered companies: “because they would establish a British presence in territories which might otherwise fall as colonies into the hands of another European power at no direct, or obvious cost to the British taxpayer.”

Rhodes position in South Africa was too powerful

He drew attention to the questionable morality of Cecil Rhodes occupying so many roles: “what renders the position in South Africa difficult for the Imperil Government is the duality of Mr Cecil Rhodes. He is at once the Premier of the Cape Colony and head of the South Africa Company. This is as though Mr Gladstone were British Prime Minister and the Chairman of the East Africa Company; and I need hardly say that such a duality would not for a moment be tolerated by British public opinion.”

Individual British Government Officials in South Africa had been deceived by the BSAC

Labouchère believed that honest officials were being deceived through deceit and trickery by BSAC officials. Initially ignorance or sympathy for other Europeans led individuals to favour the Chartered Company in negotiations with Chiefs; these were guilty of neglect, but others deliberately gave away their positions of trust.

Initially this might be done with no dishonest intent; these officials were acting in good faith – assisting the BSAC because they believed in it. However as time went by, they assisted the Charter Company for financial or personal gain, or political reasons.

The Chartered Company’s negative effect on political relations

Labouchère expressed the fear that Britain might be drawn into conflict with another power as a result of the Company’s actions. He condemned the: “attempt of the Company to lay its hands upon Manica which (according to South African International Law) most unquestionably belongs to Portugal, was nothing but buccaneering. The Chartered Company coveted this Naboth’s vineyard. They therefore calmly, vi et armis, dispossessed the Portuguese Naboth who possessed it and laid hands on it. More outrageous conduct never came under my notice,…the action of the Company should be submitted to investigation. They may however console themselves with the certainty that the Tory Government will refuse this investigation, for if it were entered into, it would rebound very little to their credit.”

But little Portugal was nearly bankrupt and a small player on the world’s political stage: “If Mr Rhodes’ gold-hunting Company had treated a German, as it treated a Portuguese, we should either have been at war with Germany, or have had to humbly apologise for the act of our Chartered freebooters…A more wanton act of filibustering in order to bolster up the shares of a financing Company with a fictitious capital, never took place. Our good name is disgraced…”

In January 1891 Truth summarised the reasons for the Chartered Company’s seizure of Manicaland as follows:

- “That Mashonaland has been found (so far) to have no gold in workable quantities and the owners of eight million pounds of shares [i.e. at market value] that represent this gold on the London Stock Exchange are obliged to look for it elsewhere if it can be hoped that more fools will purchase any of these ‘fancy’ shares.

- That Lobengula is much to astute to part with his land and so a less civilised chief has had to be found further north who can be humbugged out of a land concession, in order to enable the Company to keep its promises to its employees and to justify the assurances in regard to land which have led to the purchase of its shares by fools in England.

- That the high plateau, respecting the salubrity of which so much has been asserted, hardly begins in Mashonaland, but stretches out beyond it in Portuguese territory.”

Truth’s criticism of the British Prime Ministers and Ministers of State

Lord Salisbury (1885 – 1886, 1886 – 1892, 1895 – 1902) was criticised for opposing the Chartered Company when it suited him but being frightened of Rhodes’ influence in the Cape. He resisted the Chartered Company when he chose to do so, since his negotiations with the Portuguese resulted with his desired outcome and recognised their sovereign rights, but Truth suggested he covertly supported the main activities of the Chartered Company.

Lord Ripon was Secretary of State for the Colonies from 1892 – 1895 and was condemned by Truth for failing to control Rhodes and the BSAP: “Lord Ripon was cowed by Mr Rhodes and the herd of ruffians and speculators whom the Company had got together advanced into Matabeleland. They found no Matabele force in the neighbourhood of the frontier (the statement that there was one having been a falsehood designed to hoodwink Lord Ripon),…Lord Ripon who seemed to have entirely lost his head, on this ordered the Bechuanaland Police Force [sic] to enter Matabeleland, with a view apparently, of hindering the further advance of the Company’s expedition. But…the Police Force…aided and abetted the Company’s expedition.”

Another criticism of Lord Ripon concerned the official report of the Victoria incident which cleared the BSAC of any blame, despite other reports contradicting the official story: “One of my South African correspondents tells me that the Mr Newton who so beautifully white-washed the Chartered Company in his report on the ‘incident’ which began the Matabele War is an intimate personal friend of Mr Rhodes…as much might have been inferred from the report itself. What I do not understand is how Lord Ripon could have supposed that such a report would have any value; or if he knew the truth, how he could have offered the report to the public as anything more than a partisan verdict on the facts.”

Truth’s criticisms of the Board of Directors

Labouchère extended his attacks to the Directors, particularly the Dukes of Abercorn and Fife and Earl Grey who had been appointed directors to satisfy conditions for the royal charter; he considered they had a public duty to protect the interests of the shareholders, but also the British Government and the public. The three were directors for life, or until they became ill or resigned and could not be removed by other directors of the Chartered Company.

However all three failed to live up to expectations. John Galbraith in Crown and Charter states: “Of the three public members of the Board…two devoted little time and effort to the affairs of the Company, and the third was converted to the religion of Rhodes. They consequently were worse than useless for they gave a sheen of respectability to the operations of a Company over which they exercised no control.”

Eleanor Mabin says that Rhodes was not easily controlled, but the powers he was given by the directors were extraordinary. He was given power of attorney of the Company and until it emerged that he was spending far more than the Company could afford, he had complete freedom over the budget. When the directors failed to release information on the shareholders and what arrangements existed between the Central Search Association, United Concessions Company and BSAC he accused them of being “decoy ducks” and misleading shareholders.

When the directors pleaded ignorance of the Jameson Raid Labouchère said: “The London Directors plead that they knew nothing of this until after the raid. Would this not amount to culpable negligence? When half the City knew that the raid was about to take place, when the Company’s money was being expended and the Company’s forces being collected for the raid, these innocents knew absolutely nothing of what was occurring!”

Despite all the above, the same three directors remained on the Board.

Criticisms of Colonial Office officials

Sir Hercules Robinson was High Commissioner for South Africa and served as the connection between the colonial office and BSAC between 1881 – 1889 and 1895 – 1897 and was heavily criticised both as an early supporter of Rhodes and of the BSAC and was influential in securing the royal charter. He was given shares for his contribution and elected a director of De Beers.

Truth strongly objected to Robinson’s re-appointment as High Commissioner in 1895 stating: “The appointment is an outstanding one – for if there is one man who ought not to be sent to the Cape as Governor and Chief Commissioner, that man is Sir Hercules Robinson. He had, on leaving the Cape Colony apparently a considerable holding in the United Concessions Company, which was exchanged for Chartered Company shares and also on De Beers Company. On his return to England, he became a director of the latter Company which has a secret service fund of £10,000 per annum for political and other purposes and of the Standard Bank, another Rhodesian undertaking. The Cape Colony is now ‘run’ by three powerful corporations – De Beers, the Chartered Company and the Consolidated Gold Fields, in all of which Mr Rhodes’ will is absolute. This is humiliating, but surely it is a mistake to accentuate this state of things by sending out a Governor who has been closely connected with two of these companies?”

Maylam subsequently provided evidence that in 1892 Robinson held 2,100 shares in the BSAC and 6,250 shares in the United Concessions Company.

Sir Henry Loch served as High Commissioner for South Africa between 1890 – 1894 and was a keen advocate of Chartered Company rule in Mashonaland and Matabeleland. He aided Rhodes in obstructing Renny-Tailyour as agent for Lippert in his efforts to obtain a land concession, but when Rhodes decided the best option was to buy out Lippert, he persuaded Lippert to visit Lobengula to get his land concession confirmed and ensured it was recognised by the colonial office. Labouchère was heavily critical of Loch for giving Jameson permission to start the Matabele War of 1893 and gave permission to: “take whatever action he may deem necessary for the protection of life and property of the residents in Mashonaland.”

Settlers in Mashonaland and Matabeleland

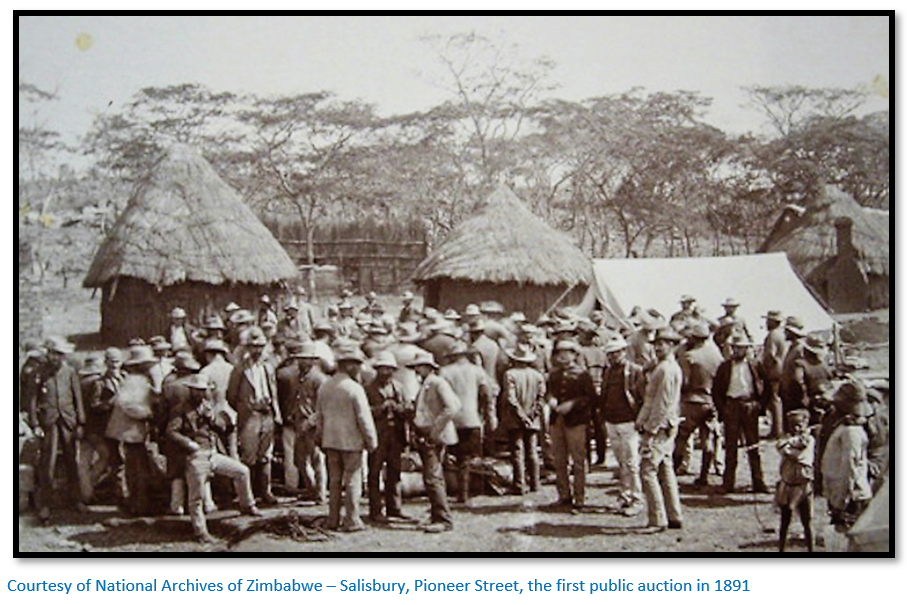

Mabin asserts by presenting the complaints and unsatisfactory conditions which newly arrived settlers faced in Mashonaland and Matabeleland Truth was able to expose that the true objective of the BSAC was not that of expanding the British Empire, but of financial speculation. This led Labouchère to the conclusion that the BSAC was not fit to run the administration of its territory. Also that the Chartered Company was unlikely to show a profit in the near future in order to discourage investors from buying the Company’s shares. His conclusions were well fed by letters of complaint from correspondents; some of which are examined below.

BSAC control of the telegraph and postal services – any report leaving the country had to pass through Chartered Company hands. The focus of Truth’s criticism was the Chartered Company withholding the true state of affairs from the public. In August 1891 the Post Office was accused of: “opening letters for the purpose of obtaining any information of value to the Company, or suppressing any intelligence the transmission of which does not suit the officials and directors…the matter has become so notorious that formal complaints on the subject have been addressed to Sir Henry Loch…Certain of the Company’s officials have openly boasted, in the presence of witnesses that no letter of importance is sent to or from the Company’s territories the contents of which they do not know.”

Indeed Labouchère states: “Many are my correspondents in Mashonaland, I have not found one among them who dares to address a letter to the Truth office, except under cover to somebody else. A pretty state of things under a territory nominally British.“

Criticism of the BSAC Police Force – Truth asserted: “The Chartered Company obtained the aid of Her Majesty’s Representative in Bechuanaland to recruit a lot of buccaneers and it has now sent these buccaneers into Lobengula’s country to defend the agents of the Company in looking after gold. Against whom the buccaneers are to defend the agents, except Lobengula, is not clear.”

A correspondent writing in April 1891 remarked that members of the Police he knew: “sincerely regretted that they had ever joined the force, the work of despatch riders riding through all sorts of weather, roads and rivers, with the constant fear of being a fair target for an assegai, is not compensated for by three shillings per day…Tommy Atkins’ lot and pay are much superior to those of an unfortunate trooper in the British South Africa Company Police.”

In 1894 Truth stated: “Many enlist under a complete delusion as to the real nature of the duties they have to perform and the conditions of the life they have to lead. This appears to be particularly the case with those who join the Chartered Company’s Police in Mashonaland. Complaint after complaint is received that the men are not only ill-paid, but ill-clothed, ill-fed, ill-sheltered and generally ill-treated.”

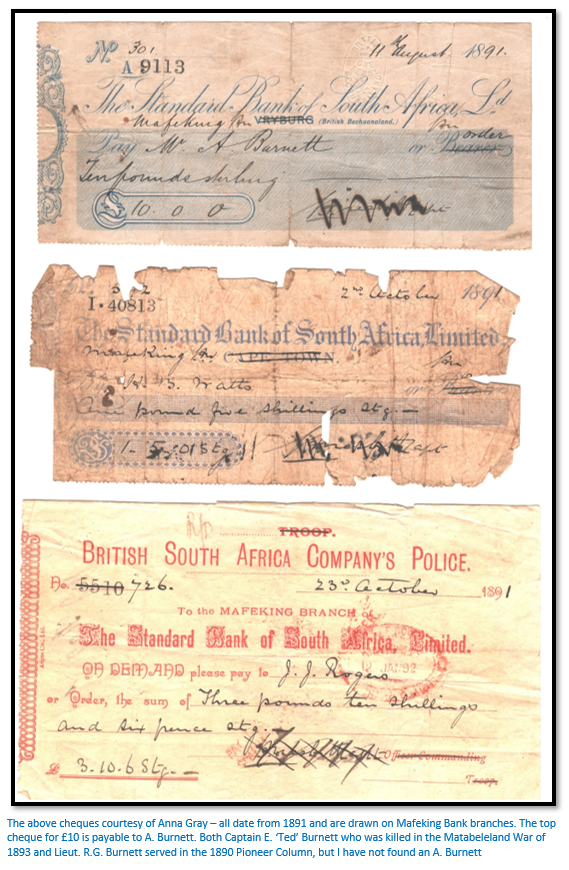

Obtaining payment from the BSAC – In April 1892 a Mr Cutler dug wells for the BSAC and found getting payment difficult. The inspector of works had signed vouchers, payable at 75% of their face value in Mafeking. Some of the vouchers were honoured; but others were not and when Mr Cutler threatened to sue, the Chartered Company replied that they had no registered office in Bechuanaland and they must be sued in London. Truth said that: “The Charter expressly provides that the Company may be sued in any Court of the United Kingdom or Colonies, that the agent in Mafeking had an office there where the summons had been delivered and that this agent made the contract with Mr Cutler; the plea looks such a flagrant plea of pettifogging dishonesty that I am curious to hear what Mr Rhodes has to say in defence of it.”

Communications with Mashonaland

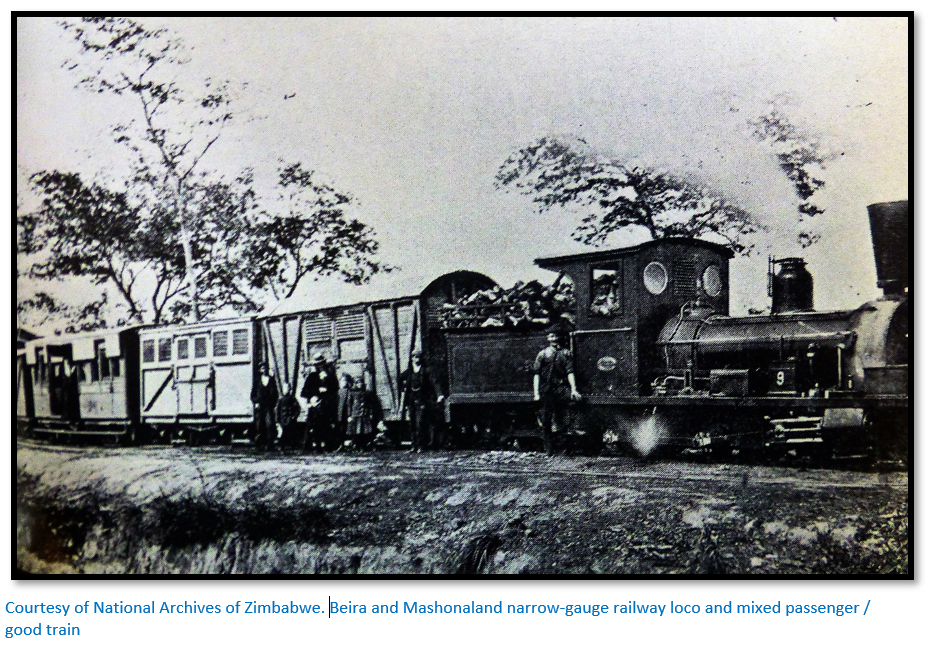

Since the territory was landlocked it was an issue of great importance and Labouchère’s intention was to show that until the problem was solved, the territory could show no profit. He also thought the Chartered Company was very slow in facilitating travel…the first train from Mafeking only reached Bulawayo in October 1897 and the Beira Railway only reached Umtali, now Mutare in 1898.

Throughout the early years farmers, miners and all settlers had to contend with slow and difficult transport links which made the transport of goods uncertain and costly.

Company propaganda led Rose Blennerhassett and her companions to expect they would travel on a waggon road from the Pungwe to Umtali in June 1891. “Major Johnson had indeed assured us that the first coach had started for Mashonaland but had omitted to add that it had arrived nowhere and was stationary on the veld not far from the Pungwe camp…unable to move either backwards or forwards on account of the condition of the fly-stricken oxen, most of which had died.”

Progress was extremely slow…it took seven years for the narrow-gauge Beira Railway to complete the 322 kilometres to Umtali, although in fairness the conditions the railway contractors had to endure were appalling. The rail link rapidly proved inadequate as this letter to Truth indicates: “…things were at a complete standstill. The engine-drivers and carpenters have all left on account of the fever and all other white men as soon as their contracts are finished clear off as quickly as possible. The floods have swept away part of the line on the flats…and the bridge across the Menda river has also been swept away. I have a very poor opinion of the railway and its usefulness, even when completed beyond the ‘fly’ belt. It is only two foot gauge and a regular tin pot affair at that.”

The effects of poor access were most felt during the very rainy season of 1890 – 91 when the flooded rivers made the roads from the south impassable for many months and severe shortages of food were experienced as the Chartered Company had made no emergency stocks. No supplies reached Salisbury, now Harare between November 1890 and April 1891; the only food obtainable was that left over after the Pioneer Column reached Salisbury and small amounts from local Mashona. Consequently food: “…was at famine prices; meal 1s 3d, bacon 3s, corned beef in tins, 2s 3d per lb…The news here about gold is conflicting, no machines are at work, nor is any mine developed far enough to form an estimate of its value…mining material is also very dear. Added to this is the heavy tax added by the Chartered Company. The game is not worth the candle.”

On the road from the south in 1891 a correspondent wrote: “…a distance of eight hundred miles has to be traversed to Fort Salisbury over roads presenting almost insufferable difficulties to locomotion, whilst the transport of machinery occupies several months without counting on the probabilities of rain and the difficulties of crossing rivers.”

Extracting revenue from settlers

The Chartered Company tried to meet the expense of administering the territories by obtaining revenue in every way it could.

Thus gun licences were required from 1893 and Labouchère comments: “I am under the impression that the Government has the right to tax any of its subjects in whatever manner and to whatever extent it pleases. It is however a very novel and remarkable state of affairs that while the white man in the region may not carry arms without a licence, the natives may arm themselves to the teeth at their own sweet wills.”

Prospecting licences and the registration and inspection of claims all required revenue stamps to be attached and the terms attached to the flotation of companies was very stringent.

On claims being ascertained to be payable, the Company have the right to float them into either a joint-stock Company or into a syndicate. The Company shall therefore within a reasonable time either make a proposal or decline to do so. If the proposal is accepted by the claimholder he shall on flotation be entitled to half the vendor’s scrip in the shares of the Company so floated. If the claimholder is not satisfied with the Company’s proposals, he has the right within one year to prove to the Company that he is in a position to float on better terms and he shall, on the flotation of the claims, give the Company half the vendors’ scrip.

In 1895 however paying gold properties were rare and Labouchère wrote that his information: “up to date is that no paying gold has been seen outside the four corners of a prospectus; that the settlers are few and far between and are cursing the Company and drinking spirits; that the only persons growing rich are the liquor vendors; that the climate is such that it is impossible that Europeans can permanently reside in that country without serious danger to their health…”

Truth in 1895 wrote that liquor licences cost £100; licences for pawn brokers and foreign agents cost £20; butchers and bakers licences cost £10.

Truth and Africans living in Mashonaland and Matabeleland

Mabin says Labouchère was no philanthropist, but he was a humanitarian and his strong moral upbringing led him to oppose injustice in any form. His real concerns were the mistake in using Chartered Companies such as the BSAC as tools for territorial expansion and their abuse of their privileged position.

His coverage of local natives began with the deterioration in relations from July 1893; the BSAC’s motives for provoking the Matabele War of 1893; the treatment of enemy wounded and the treatment of the amaNdebele after the War and the distribution of their land and cattle.

Also covered in subsequent editions of Truth was the question of forced labour for the mining (chibaro) and farming industries, the hut tax, justice for Africans and the First Chimurenga or Umvukela of 1896 – 97.

The Victoria incident

This is already covered under the earlier chapter on the Conquest and settlement of Matabeleland 1893 – 1896 and Truth argued that the war was unnecessary, that the BSAC deliberately provoked it, that the Company’s military preparations continued despite the lack of aggression from the amaNdebele and that Sir Henry Loch was deliberately deceived by Jameson and: “…something has to be done, otherwise the Company would go into liquidation. This something has taken the form of a proposal to wipe Loben and his nation out of existence, in order to lay hands on Matabeleland, where it is hoped that gold maybe discovered. With this view, a wolf-and-lamb dispute has commenced between the Company and Loben. That monarch sent some of his troops into Mashonaland. The Company denies that he has any rights there, although as they derive their own rights from him [Rudd and Lippert concessions] if the one does not exist, neither does the other. To punish him, he is to be deprived of Matabeleland and his people are to be shot down with breech-loading rifles and machine guns.”

In all his comments about BSAC propaganda and the war Labouchère stressed the same points:

- That the BSAC was a speculative Company and that profits were the first objective of the directors

- The directors hoped that the war and the over-running of Matabeleland would save the Company from bankruptcy.

“Having made much money by palming off worthless shares to idiots who fancied that Mashonaland was a Land of Ophir, they now want to lay hold of Matabeleland in order once again to play the same game.”

An editorial of 31 August 1893 stated the BSAC was in debt to De Beers, the shares had fallen and finances were in a parlous state and this was the reason behind the war. In Labouchère’s opinion this was confirmed when newspapers that backed the Chartered Company began “puffing” the value of gold reefs in Matabeleland as soon as the war began.

Other Editors agreed; the Pretoria Press wrote: “…must be remembered that the war now being entered upon had nothing to do with England. It is a mere buccaneering sally after loot and land engineered by a private Company.”

Concern at the manner in which the war was carried out

Truth asserted the BSAC was guilty of brutality against the amaNdebele which proved that the Company should not be allowed to administer the territory. The behaviour of the volunteers was attacked, they were referred to as “a crew of buccaneers” as “frontier riff-raff” and “border ruffians” and Labouchère attacked the use of Maxim guns and the treatment of the wounded.

“…They went into Matabeleland with no higher motive than to obtain land, mining claims and ‘loot’ from its murdered inhabitants. Such a thing may possibly have occurred before, but never that I know has it been so cynically admitted and never has the British flag been so disgraced.”

Most of his information came from correspondents as this letter from Pretoria exposes: “Commandant Raaff was here calling for volunteers to attack Loben…The men who volunteer are the very scum of the goldfields, totally unfit for any campaign. They have already started looting stores on their way up. The State Artillery were sent out after one draft to bring the looters back, which they did. The volunteers are deserting, finding that the Company only find them arms and ammunition; their pay they must steal from Loben.”

In March 1894 Truth published their actual terms and conditions of recruitment: “special interest attaches to the offer of land and gold claims to volunteers against Lobengula…let us hear no more of the cant about protecting ‘the defenceless Mashonas’…what these ‘brave pioneers’ are fighting for is Matabeleland.”

Truth directed its criticisms against the cold-heartedness of the Chartered Company and its troops, the inequality of attacking the amaNdebele with Maxim guns and the dishonourable death of Lobengula after his peace offering of gold sovereigns which was stolen by two troopers and who covered-up his message.

Labouchère found nothing: “is more sickening than the accounts which the ‘heroes’ of Matabeleland publish of their own and each other’s exploits. Bullets are as thick as hail around them and yet these bullets hardly ever injure them. They bear indeed, like Achilles, a charmed life.”

Using Chartered Company figures, he estimated that 3,000 amaNdebele warriors were killed and wounded, 1,000 were killed and 500 slightly wounded so that they escaped and asks what happened to the remaining 1,500 wounded? “If, as the Secretary hints, the wounded in the Zulu [sic] campaign were left to die by a disciplined Imperial force, does it not stand to reason that this would be more likely to occur in the case of an undisciplined force, collected together by promises of a share in the booty which could only be obtained by its owners being slain.”

Vere Stent, the correspondent who accompanied Rhodes to the Indaba stated that the amaNdebele wounded: “disappeared in a most mysterious manner.”

A Lionel Cohen wrote to Truth giving details of prisoners who were promised their lives in return for information, then shot the next day; on bayoneting of Matabele wounded despite their pleas for mercy and on Mashona ‘boys’ being ordered to assegai all the wounded on one occasion. “I have got the names of these and can positively swear to this as I was in charge of all the wounded up to the third week in Bulawayo and there was not a wounded Matabele amongst them.”

Post-war accounts of looting and cattle raids soon appeared. Truth quoted this letter in January 1894 written to The Times:

“At 3:30am on the 16th [December] we commenced our attack; the enemy fled at our first fire and we never saw them again. Only a few were killed, but we took all their cattle.

At 5am on the 18th we took a large kraal after a sharp skirmish and captured 500 cattle and a few of the enemy. My syndicate has got 90,000 acres of the best grazing land in the country. We are going to stock it at once…I have got twenty miners claims which a prospector is going to peg out for me on the main reef below Bulawayo. My ten claims in Mashonaland will be pegged out before Christmas and all these things point to the fact that the year has not been wasted. There are great fortunes to be made in Mashonaland and Matabeleland.”

Local press reports pointed to the success of the campaign and were quoted in Truth: “The final distribution of the loot fund takes place at the end of the month. It is expected that the amount to be distributed will be £40 per share, which with the £70, the average price obtained for farms after the completion of the campaign – makes £110 per volunteer for three months service.”

In September 1896 Labouchère drew a direct relationship between the looting of cattle and the First Umvukela of 1896 when referring to one of Rhodes’ speeches he said: “the scheme of the Company seems to have been that a hut tax was to be imposed upon [Ndama’s people] and they were to be deprived of their cattle. This it was thought, would force them to work for the white man at a low wage. That they should have rebelled against this usage and that they should be unwilling to surrender unless in future secured against it, is hardly surprising.”

The actions of the BSAC would eventually cost the British taxpayer

Truth predicted in August 1891 that the actions against Lobengula would result in the Chartered Company taking profits and leave the British taxpayer to pick up the tab: “Sooner or later, in all human possibility, we, the taxpayers of the United Kingdom, shall be called upon to assist Mr Rhodes and Sir Henry Loch in maintaining sovereign rights which they have already assumed to exercise in Lobengula’s country…It is…possible that…the Chartered Company may prove strong enough to defend themselves against Lobengula. It is infinitely more likely however, that…they will…invoke the aid of the Home Government…”

The first actual charges that the BSAC was costing the British taxpayer appeared after the 1893 War ended: “the astute Rhodes seems to be throwing the cost of the war upon us. He is disbanding his filibusters after paying them for their services out of the conquered country, while the British taxpayer is required to pay for the Imperial force that aided in the raid* and that is now doing the greater part of the work in securing the country for the Company. If the Chartered Company is to have the spoils, why are we to pay for securing it?”

[*This refers to the Tuli column under the command of Lt-Col. Goold-Adams comprised of 250 Bechuanaland Border Police and another 250 volunteers under Capt. P.J. Raaff. About 300 were mounted men and they had five Maxim guns and two seven-pounders]

The charge appears to have justification…Sir Henry Loch estimated that the BSAC had cost the British Government over £700,000 between 1890 and 1894.

The Jameson Raid

According to Labouchère the Jameson Raid was yet another example of the BSAC’s disregard for legality and demonstrated the connivance of the colonial office in their failure to stop the raid which was comprised almost entirely of BSA Police and Bechuanaland Border Police and in their handling of the participants and their court case in England after the raid.

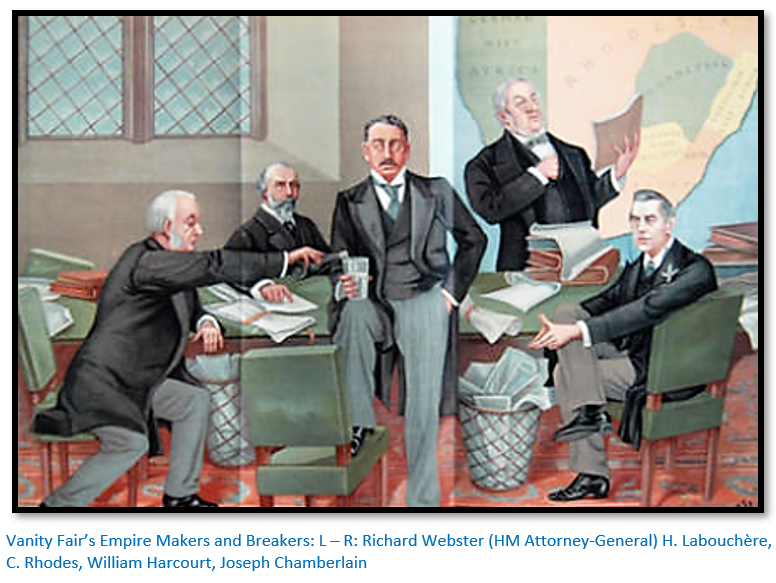

In order to facilitate the raid a narrow section of the Bechuanaland Protectorate was ceded to the BSAC, ostensibly for the construction of the railway. This process was concluded in a very hurried manner in October 1895 between Rutherfoord Harris, the BSAC’s Cape Town secretary and Joseph Chamberlain, then secretary of state for the colonies, so facilitating Rhodes’ plan for an invasion of the Transvaal.

Labouchère agreed to serve on the Committee of Enquiry into the Jameson Raid; however his participation on the committee effectively destroyed his ability to comment impartially and from his appointment in January 1897 his comments were reduced in volume and intensity. The much closer imperial supervision of the Company that the Jameson raid generated meant that Labouchère’s interest in the Company faded.

In January 1898 after the Committee of Inquiry was complete, Labouchère published an article entitled ‘How Chartered shares were sold before the raid’ showing how the shareholdings of the following individuals and companies declined between July 1895 and 31 March 1896. The Dukes of Abercorn and Fife, Earl Grey, Lord Gifford, Sir Horace Farquhar, Rhodes, Beit, Maguire, the Rudd brothers, Thompson, Lord Rothschild, Cawston and other groups associated with Rhodes, Beit, Rudd, Cawston and Gold Fields of South Africa and the Beit Syndicate. In July 1895 they owned over 900,000 shares between them – by 31 March 1896 their shareholdings were reduced to 61,457.

In Labouchère’s opinion this reinforced his notion that the BSAC existed as a financial vehicle for the directors to enhance their wealth. Maylam agrees with this thesis, saying that the: “main promoters held about seventy per cent of the shares in 1889 and only about fifteen per cent in 1893 and that Beit profited substantially from such transactions.”

Henry Labouchère – the man

Henry Du Pré Labouchère whose arguments in the journal Truth are considered here lived from 1831 to 1912. He was born and raised in England although his family had fled as Huguenots from France and in many subjects he took a strong moral and humanitarian viewpoint. He travelled widely as a diplomatic attaché in the British Diplomatic Service between 1854 – 1862. He greatly admired Joseph Chamberlain as a radical reformer and rising star in the Liberal Party but became his critic when he abandoned the policy of home rule for Ireland.

Labouchère worked for and contributed to many newspapers and journals becoming owner and editor of Truth in January 1879 and wrote many of its articles covering the court, political events and financial affairs. As a radical he was generally opposed to imperialism and particularly the use of Chartered Companies to secure territory stating in 1890: “I have no high opinion of any of these Chartered African Companies. Their professions of philanthropic aims disgust me. I regard them as humbug of the most palpable kind. They are monetary speculations, designed to put money into the pockets of their promoters and I have always thought it a great mistake and one which may land us in serious trouble, that promotors should be granted charters giving them vast powers over enormous districts of Africa and allow them to compromise the Empire in their lust for self.”

He was deeply suspicious of Chartered Companies in general and the BSAC in particular and there is no doubt he led a strong campaign against the Company especially in advising potential shareholders of the Company’s financial state and its prospects.

Most contemporary writers and later historians tended to dismiss Labouchère as hostile to the BSAC; Hugh Marshall Hole, whose entire career was with the BSAC, considered his statements slanderous and a fiction and someone who never missed an opportunity of “squirting venom” at Rhodes and the Chartered Company.

Truth’s reputation ensured that it became the obvious journal to send correspondence if anyone had critical material on the Chartered Company. However, Mabin notes that the BSAC never took Truth to court for libel.

References

E.M.O. Mabin. Truth and the British South Africa Company. The Development of a Radical’s opposition to the development of Capitalist Imperialism in a Southern African context.

J.S. Galbraith. Crown and Charter. The Early Years of the British South Africa Company. University of California Press, 1974

P. Maylam. Rhodes, the Tswana and the British. Colonialism, Collaboration and Conflict in the Bechuanaland Protectorate 1885 – 1899. Westport, Connecticut; Greenwood Press, 1980.

T.O. Ranger. Revolt in Southern Rhodesia 1896-7. Heinemann 1979