The British South Africa Company

Introduction

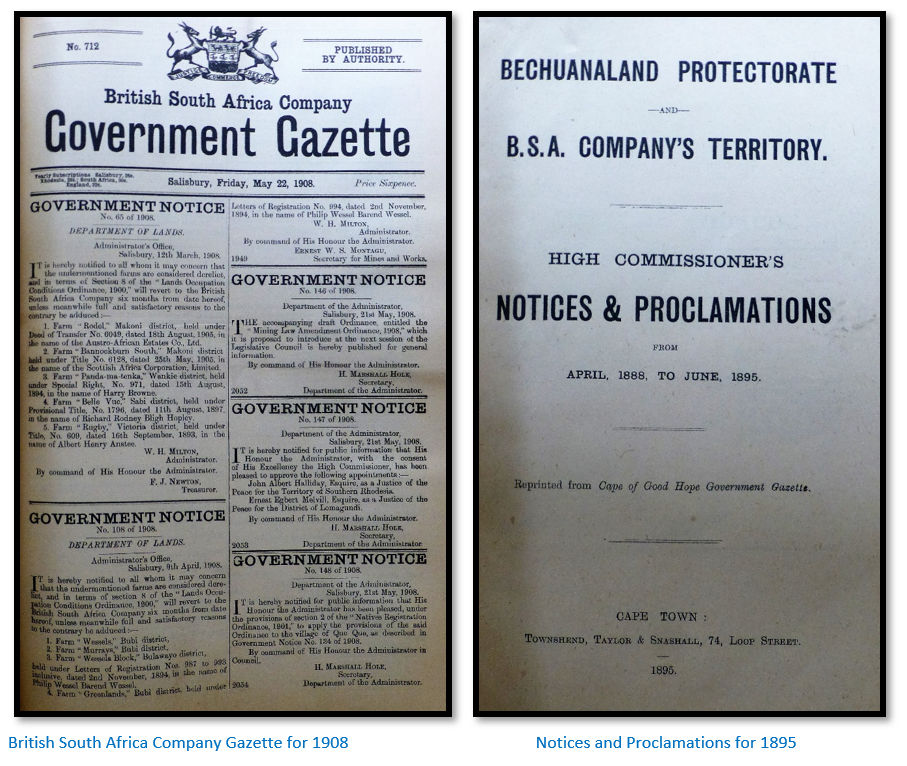

This article explores the preliminary manoeuvres prior to the formation of the British South Africa Company (BSAC) without going into the detail of either the concession-seekers, or the Rudd concession, or the objections raised by Lobengula, King of the amaNdebele after the signing of the Rudd Concession. These are explored in other articles under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com.

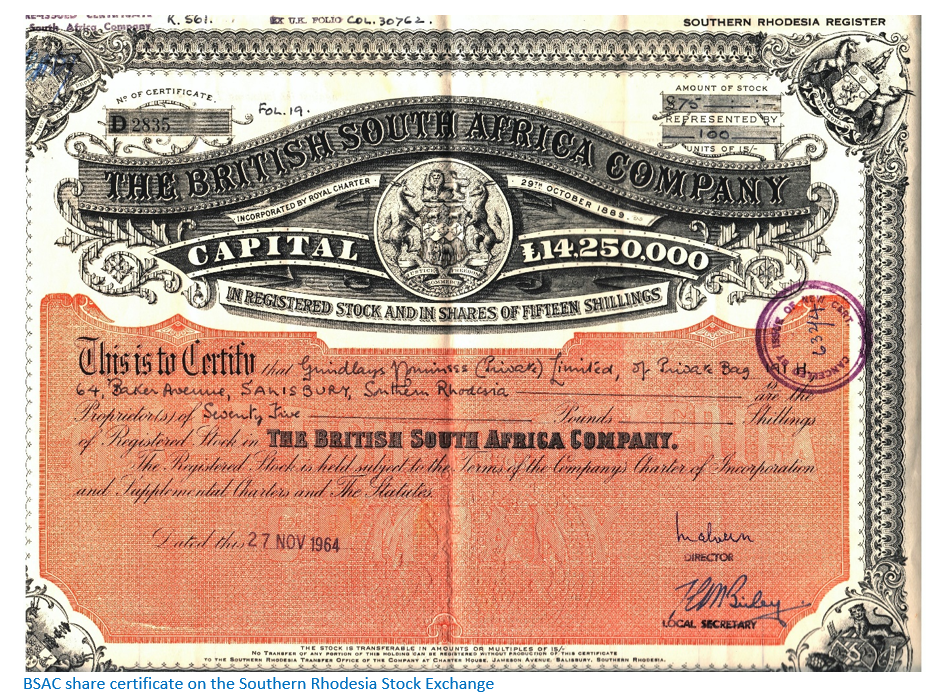

Martin Meredith writes in Diamonds, Gold and War: “The British South Africa Company, emanating from a flimsy agreement involving an illegal arms deal that had been obtained in dubious circumstances, and since repudiated repeatedly by its principal signatory [Lobengula] was formally granted a royal charter by Queen Victoria on 29 October 1889, with a remit similar to that of a government.”

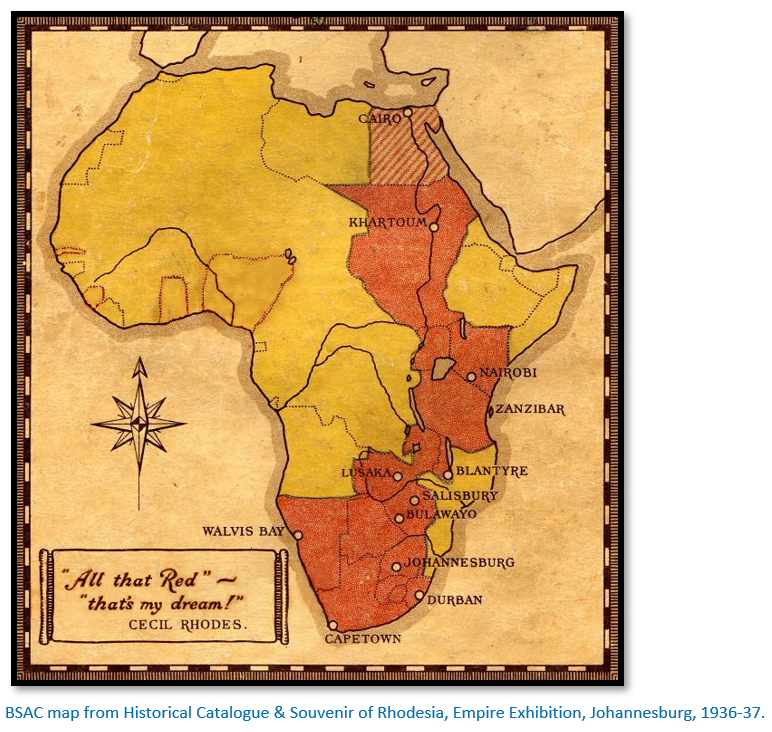

The flip side of the above statement is contained in the BSAC Historical Catalogue and Souvenir of Rhodesia produced for the Empire Exhibition at Johannesburg in 1936–37 when Sir Henry Birchenough, Chairman, wrote of a miracle that occurred between 1888 – 1893 when Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe was added to the British Empire “without the loss of a single soldier of the British Regular Army or the expenditure of a shilling of the British taxpayers’ money.”

The use of a Royal Charter was definitely a way of building an Empire “on the cheap” without costing the Treasury a penny then, or in the future. Powers assumed by the Secretary of State for the Colonies in theory prevented local tribes and chiefs from injustice, or the company being involved with foreign powers, or obstructing the commercial interests of other businesses.

Keppel-Jones writes that from “the elaborate provisions for ordinances, police, railways, land settlement…the reader of the charter would have no doubt that it was a program of imperial expansion…[but]…he would not gather that the sole foundation was a batch of purely mining concessions, of which the most important had been repudiated by the grantor.” [Lobengula]

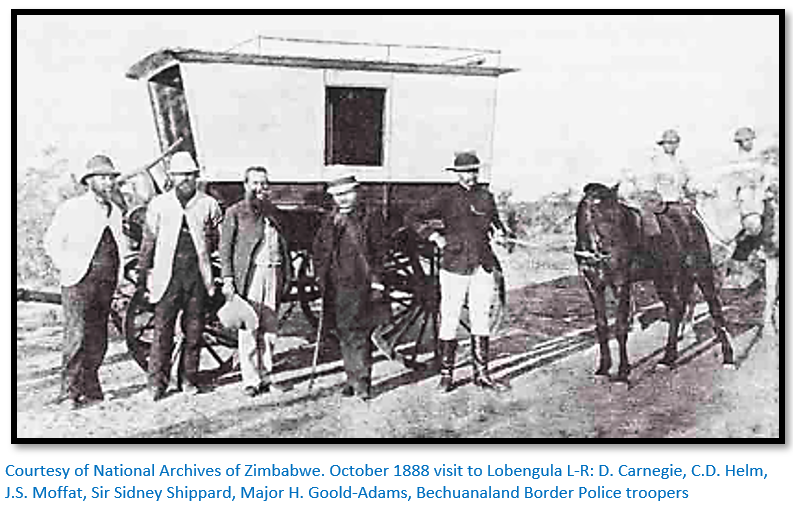

The article does not include concessions covering present-day Malawi, which responsibilities were assumed by the colonial office in 1894, or Barotseland in present-day Zambia where Harry Ware and then the BSAC agents, Sharpe, Lochner and Wilston were active in the 1890’s in securing concessions in return for BSAC protection.

The rise and use of royal charter companies

The advantage of using chartered companies to the colonial office was that it secured territory for the British empire without the expense of British taxpayers maintaining colonies and protectorates. Rhodes’ request to Lord Knutsford in June 1886 for a chartered company for the area of Zambesia was definitely not the first occasion this approach to territorial expansion had been used.

A royal charter company received certain rights and privileges which effectively created a monopoly in a specified geographic area with the right to use force to open and maintain its trading rights. The Crown provided the political support and endorsement for carrying out what usually amounted to high risk business ventures and in return the economic expenses and business risk was carried by private individuals and joint-stock companies who would ultimately benefit.

In the seventeenth century the Dutch West India Company (WIC) the Royal African Company, the African Company of Merchants, were some of those charter companies given trading monopolies in Africa; the WIC for example, was empowered to negotiate treaties, make war and peace with local chiefs in West Africa, acquire ports on the coast and pass legislation in its territories. The Dutch West India Company and its successors was much involved in the gold and slave trade in present-day Ghana.

The situation after 1870

After 1870 many of the European powers sought new markets as well as looking for new sources of raw materials and valuable minerals and Africa was an obvious candidate. Germany in Togo, Cameroon, Tanganyika and South West Africa, Belgium in the Congo Free State, France in Senegal and Lake Chad, Italy in Ethiopia and Portugal in Moçambique and Angola began to challenge Britain for colonies in the scramble for Africa.

The cornerstone of British foreign policy in southern Africa was always the security of the Cape Colony and Gladstone was reluctant to become involved in any territory to the north. As foreign powers began to show an interest in the region, the Cape Government under Rhodes urging put pressure on the Imperial Government to act. There was concern that the German and Transvaal Republic might act in concert to block any northward expansion of British territory, thus threatening the economic dominance of the Cape Colony.

Around 1886 voices began urging an arrangement with Lobengula for concessions in Mashonaland saying the Portuguese and Germans had territorial aims and the Transvaal Republic were interested. Sir Hercules Robinson, the High Commissioner for Southern Africa, forwarded petitions to the Queen from the Chambers of Commerce in Cape Town and Grahamstown: “that measures are now urgently demanded for securing to British influence the territory stretching from the present limits of the Bechuanaland Protectorate to that great natural line of demarcation, the Zambezi River.”

The Transvaal Republic upped the ante in 1887 by sending a party into Matabeleland and claimed to have agreed what became known as the Grobler Treaty with Lobengula.

The Berlin conference of 1884 – 85 laid out the ground rules for any territorial annexations; Article 35 stated that a mere claim to territory was not enough for international recognition of a colony. Under the doctrine of ”effective occupation” the colonizer had to prove that it had authority and control over a colony. [The importance of this concept in relation to Portugal’s claims to Mocambique are discussed in the article How Mutare and Manicaland were annexed from the Portuguese under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Now once again royal chartered companies began to play an important territorial role and were established to demonstrate effective political and economic occupation. In 1886 the Royal Niger Company was granted a charter; two years later another was given to the Imperial British East Africa Company; the Companhia de Moçambique was awarded a concession in 1891 to consolidate Portugal’s four hundred year old claim to Moçambique.

The powers entrusted to royal charter companies were absolute. Take for example, the Royal Niger Company whose charter granted in 1886 authorised it to administer the Niger delta and all the country along the Niger and Benue rivers. Palm oil was the main export with the main imports being cloth and alcoholic drinks - treaties were concluded with local rulers which imposed monopolies on them and forced out French and German competition.

Uprisings by local tribes in 1886 and 1895 against the companies’ monopolies were put down by Royal Niger Company police backed up by gunboats and the Royal Navy. When King Jaja of Opobo organized his own trading network and even began running his own palm oil shipments to Britain, he was lured onto a British warship and shipped into exile on Saint Vincent on charges of "treaty breaking" and "obstructing commerce." In 1891 he was given permission to return to Opobo but died en route, allegedly poisoned with a cup of tea. The charter was revoked in 1899 but these actions form the setting for some of the British South Africa Company’s own arbitrary actions.

The British South Africa Company (BSAC or BSAC)

Preliminary activities to the BSAC’s formation included:

Acquiring a mining concession with Lobengula over Mashonaland

Alarmed at the news that the Transvaal Republic had concluded the Groblet Treaty, the colonial office sent John Moffat, son of the missionary Robert Moffat, to meet Lobengula and in 1888 they agreed the Moffat Treaty which guaranteed peace between the amaNdebele and the British and ensured Lobengula would not enter any relations with a foreign nation without Britain’s consent and at the same time Lobengula renounced the Grobler Treaty.

Rhodes’ interest in Mashonaland and Matabeleland arose both from their geographical location in Zambesia as it was then called and in the reputed gold wealth of area. (For stories of the wealth of Mashonaland see the article The Wood-Francis-Chapman syndicate of concession-seekers under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com)

Rhodes’ power and wealth were based on De Beers Mining Company in which he began acquiring shares in 1837 and which after amalgamating many of the smaller diamond companies eventually became De Beers Consolidated. The largest obstacle was Kimberley Central Company controlled by Barney Barnato (Barnet Isaacs) who opposed amalgamation, but with the assistance of Alfred Beit the amalgamation was completed by 1889. Goldfields of South Africa was established in 1887 by Rhodes and Charles Rudd and became Consolidated Goldfields in 1892. Together these two companies became Rhodes’ powerbase upon which he planned to build his empire.

In September 1888 Rhodes’ negotiating team of Charles Rudd, Rochfort Maguire and ‘Matabele’ Thompson had reached Umvutcha at Gubuluwayo to negotiate a mineral concession from Lobengula. Rudd had a letter of introduction from the High Commissioner, Sir Hercules Robinson and by ‘coincidence’ the Resident Commissioner of Bechuanaland Sir Sidney Shippard arrived at the same time. Clearly these moves were intended to impress Lobengula and to put Rhodes party at an advantage over other concession-seekers. Sir Sidney and his superior, Sir Hercules Robinson were strong supporters of Rhodes “push to the north” and later received their rewards for loyalty. Robinson was awarded shares in the Central Search Company and became a Director of De Beers; Shippard was appointed legal adviser to Consolidated Goldfields of South Africa in 1894 and a director of the BSAC in 1896.

Shippard believed the occupation of Mashonaland was inevitable: “The accounts one hears of the wealth of Mashonaland of known ….and believed in England would bring such a rush to the country that its destiny would soon be settled whether the Matabele liked it or not.” So for local officials like Shippard the real question was not how long the amaNdebele would be in control, but if their dispossession would be through the chaos of a gold rush like those in California 1848 - 55, or a peaceful transition dominated through Rhodes’ monopoly of a royal charter.

In Shippard’s view which favoured the second option his tasks became:

- To convince Lobengula that Rhodes’ proposal had the blessing of the colonial office,

- To satisfy Lobengula that his proposals were the best to sooth the King’s fears of a chaotic gold rush; young amaNdebele warriors needed only the King’s permission to kill the whites and the Imbizo, Ingubo and Insuka regiments were particularly restless,

- To persuade Lobengula that granting Rhodes a concession would deter the Boer threat,

- To convince all the other concession-seekers at Umvutcha that their efforts were in vain,

- To brief Rudd on political developments in his attempt to secure a mineral concession.

[For further details see the articles Were Lobengula and the amaNdebele tricked by the Rudd Concession and Why Lobengula sent envoys to Queen Victoria in the late nineteenth century under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Maguire wrote: “Sir Sidney’s visit did a great deal of good removing such misunderstanding which was steadily growing worse” and that “Shippard and Moffat did all they could for us.”

John Moffat, Shippard’s deputy, supported the concession going to a “powerful company” and may have favoured Rhodes as Maund tried to represent himself as being in some official capacity.

Charles Helm, the missionary at Hope Fountain Mission and Lobengula’s interpreter, probably supported a chartered company as a way of gradually civilising the amaNdebele and converting them to Christianity…under Lobengula’s rule there were virtually no converts. The missionaries were aghast at the news of the men and old women being murdered on amaNdebele raids and the young men, women and cattle captured. In 1888 there were thirteen raids some of which crossed the Zambesi river and others into the Umfuli, now Mupfure river area.

Lobengula signed the Rudd concession on 30 October 1888.

The King had been adamant all along that he would not give away any land and the concession granted only: “complete and exclusive charge over all metals and minerals situated in my Kingdom, principalities and dominions, together with full power to do all things that they may deem necessary to win and procure the same.”

The major defects allied to the Rudd concession related to:

- The BSAC’s authority derived from Lobengula’s claims to territorial dominion and sovereignty over Mashonaland and Manicaland which were extremely questionable. Edward Fairfield, the assistant undersecretary at the colonial office, suggested amaNdebele incursions into Mashonaland were more in the tradition of murderers, kidnapers and thieves than of ‘government.’ But his claims were dismissed and his superior at the colonial office, Sir Robert Herbert wrote: “whatever maybe the actual truth about Lo Bengula – and I certainly doubt his being anything like as bad as Mr Fairfield makes out – it will never do for us to admit any doubt of his right over Mashonaland, or to open the door one inch to Portuguese claims. In reality the ancestors of some of the Mashona people were represented by the Rozvi Statebut its central authority had disappeared and the Mashona lived under local chiefs who owed no allegiance to any central authority. They largely practised subsistence agriculture but had long-standing links with the Portuguese based at Sena and Tete based on a gold trade which was mined locally during the dry season.

- Verbal promises made by Charles Rudd which were, according to Rev Charles Helm the interpreter, that: “they would not bring more than ten white men to work in his country, they would not dig anywhere near towns and that they and their people would abide by the laws of his country and in fact be as his people.”

Both of these defects would in time be ignored and shrugged off to suit the situation.

The news that Lobengula received that he had been tricked into “selling his country” has been covered in some detail in the article Were Lobengula and the amaNdebele tricked by the Rudd Concession mentioned above.

Rhodes’ task of out-manoeuvring other concession-seekers

On 11 February 1888 Lobengula signed a treaty of friendship with Britain that was counter-signed by J.S. Moffat as assistant-commissioner pledging that he [Lobengula] “would not sign any treaties or sell or cede any part of his nation without the knowledge and agreement of the British High Commissioner for South Africa.” Most of the concession-seekers at Umvutcha were composed of small syndicates of traders trying their luck [See the article The Wood-Chapman-Francis syndicate of concession-seekers under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Gifford and Cawston’s Exploring Company and Edward Maund

The major rival concession-seekers at Umvutcha was the Exploring Company whose holding company the Bechuanaland Exploration Company had secured mineral rights in Bechuanaland and wished to expand into Mashonaland. The company had two of Queen Victoria’s sons-in-law as directors and was headed up by Lord Gifford and a well-known stockbroker George Cawston with financial backing from Baron Nathan de Rothschild. They were actually Lobengula’s preferred choice and also claimed to have the backing of the City of London and the British Government.

More challenging for Rhodes was the news that Edward Maund, the Exploring Company agent, had informed Lobengula that he had been tricked by Rudd and his party and had offered to lead a delegation to England to protest at the colonial office and to the Queen. Lobengula told the two izinDuna: “There are so many people who come here and tell me that they are sent by the Queen. Go and see if there is a Queen and ask her who is the one she really sent” and he also told them to deny ‘he had given away his country.’

When Maund arrived in Cape Town in December 1888 with his amaNdebele delegation of Babayane and Mshete on their way to visit Queen Victoria he met up with Rhodes. Rhodes had initially been annoyed at the move, but changed his mind after Lord Knutsford, the secretary of state for the colonies, told Rhodes that the delegation might actually improve his chances of winning a minerals concession from Lobengula if he managed to consolidate his interests with those of Maund’s employers, the Exploring Company.

Lord Knutsford’s deputy, Robert Herbert had earlier made the same proposal to Gifford and Cawston suggesting that they too were more likely to win a royal charter over Zambesia if they merged their interests with Rhodes on the old maxim “if you can’t beat them, join them.”

Rhodes’ side had the Rudd concession and the approval of local colonial office officials; Gifford and Cawston had a concession in Bechuanaland and influence in the City of London.

The envoys meantime were shown displays of Britain’s military strength and meeting the Queen in the splendour of her royal palaces was designed to inspire them with the authority of “the great white queen.” Rhodes arrived in Britain in March 1889 as the envoys were about to leave only to learn that the colonial office had stated its opposition to the Rudd concession.

The Lippert concession – E.R. Renny-Tailyour

The other main rival concession-seeker was Edward Lippert, a cousin of Alfred Beit. Despite Rhodes throwing every obstacle in the path of his agent Renny-Tailyour, he did manage to reach Lobengula and claimed to have been granted a concession. Despite the dubious validity of the claim, Rhodes preferred to negotiate a settlement rather than have the validity of the claim tested in the English courts.

Lippert took his wife to Matabeleland in 1891 and persuaded Lobengula to confirm the concession for land rights before witnesses. [See the article on the Lippert or Renny-Tailyour concession under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] Lobengula believed that Lippert was in opposition to Rhodes and the BSAC – he was kept completely in the dark about the tie-up until a year later. The concession was purchased immediately by the BSAC in return for Lippert receiving shares in the United Concessions Company and the BSAC, plus 75 square miles of land between the Sebakwe and Umniati, now Munyati rivers and £5,000.

A sense of inevitability about the fate of the AmaNdebele nation

John S. Galbraith in Crown and Charter states the amaNdebele nation was marked for demise even if there had been no Rhodes. In the 1880’s any African nation with reputed riches was certain for European domination; the only question being when and by whom. The amaNdebele might control elephant hunters and traders who posed them no threat; but they could not resist a gold rush. David and Mary Carnegie were greatly respected in their lifetime [see the article on Hope Fountain Mission under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] and he wrote: “gold and the gospel are fighting for the mastery and I fear gold will win.” Galbraith writes that a key part for the rationale for expanding the empire was the view: “of the tyrannical African chief who terrorised not only his enemies but his own people, living in fear of the whims of a despot who might, if the mood struck him, order the death of any of his subjects, or even hundreds of them.”

The missionaries blamed their failure to convert the amaNdebele to Christianity on the character of the nation and the peoples’ fear of retribution from the King, so they welcomed the possibility of Lobengula’s downfall as a means of converting the amaNdebele to Christianity.

Under Mzilikazi few concessions had been granted, but by the time Selous reached Matabeleland in 1872 most of the elephants in the more accessible areas had been hunted out, the remainder retreated into the “fly-country” where only those prepared to hunt on foot would venture. The ivory trade was in serious decline and Lobengula may have believed he might extract more revenue from concessions to replace those funds.

For evidence of this Father Croonenberghs in Journey to Gubulawayo writes on 28 February 1880 on the occasion of Greite leaving his property which he sold to the Jesuits (See the article Old Jesuit Mission under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com) “For today he [Greite] left us taking with him several waggons full of goods which will realize a fortune when sold in the Cape. A few details will help you to understand. His waggons were laden with 10,000 lbs of ivory, the rich spoils of many elephants killed in the hunting. The weight of the tusks varies, according to age, from 60 to 80 and even 100 lb. Mr Greite also took some 400 lb of ostrich feathers, the brilliant plumage of hundreds of these birds.

Three months ago a load f 6,000 lb of ivory left Gubulawayo. During our own journey northwards from the Transvaal to Shoshong, we met several waggons carrying, between them all, almost 20,000 lb of elephant ivory. You can see, if hunting continues this way, not one elephant will remain in this part of the country before very long. Then the hunters will have to push further north beyond the Zambesi and up into the very heart of Africa.”

Civilisation and the economic opportunities of Zambesia

Both the missionaries and the gold-seekers used the above as moral justification for the three C’s; Christianity, Civilisation and Commerce. Most Europeans at the time believed they should have the right to exploit lands in Africa which the Africans themselves had not developed.

In 1888 Joseph Chamberlain already called: “Your coming Prime Minister” said: “…as far as the unoccupied territories between our present colonial possessions and the Zambesi are concerned, they are hardly practically to be said to be in the possession of any nation. The tribes and Chiefs that exercise domination in them cannot possibly occupy the land or develop its capacity and it as certain as destiny that, sooner or later, these countries will afford an outlet for European enterprise and European colonisation.”

A final impediment

In October 1889 Thompson, one of the Rudd concession signatories, had been persuaded to return to Matabeleland with Rhodes’ emissary Jameson following his ignominious flight a month earlier after the killing of Lotshe and his kraal at the hands of Lobengula’s executioners. After paying off many of the other concession-seekers, both men (Jameson was at Umvutcha from October 1889 to January 1890) reassured the King that all they wanted was to dig for gold with just ten men at a time and they wanted no land.

Jameson tried to renegotiate the Rudd concession, but Lobengula would not agree to a new written agreement and Jameson manipulated his words to give the impression that Lobengula had agreed to the occupation od Mashonaland.

One final impediment arose which is highlighted by Meredith in Diamonds, Gold and War. On learning that the concession had been obtained with the promise of guns, the then Anglican Bishop of Bloemfontein, George Knight-Bruce, later Bishop of Mashonaland declared: ”Such a piece of devilry and brutality as a consignment of rifles to the Matabele cannot be surpassed.” The promise of arms was a blatant breach of Cape law, but Sir Hercules Robinson disingenuously stated that if Lobengula was not supplied arms from Britain, the Transvaal Republic would be happy to supply them in exchange for a concession.

Robinson’s assistant, Graham Bower wrote in his memoirs: “It was clearly illegal to deliver Martini-Henry rifles to a native chief. On the other hand unless the rifles were delivered the contract was not complete and the concession was invalid. Sir Sidney Shippard solved the problem by issuing a permit on his own authority.”

Knight-Bruce was quickly “squared” by Rhodes who wrote to Rudd: “Without telling you a long story, I will simply say I believe [the Bishop] will be our cordial supporter in future. I am sorry for his…speech…but he has repented.”

The arms were delivered in two batches to Gubuluwayo but left untouched by Lobengula until 1893 when Percy Crewe cleaned them before the1893 Matabele War. [see Reminiscences of Percy Durban Crewe of Nantwich Ranch, Hwange under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Convincing Lobengula that granting the concession to a monopoly was the best choice

Lobengula did not know that Queen Victoria after warning him in a letter against giving away his country, had granted the royal charter until John Moffat told him in November 1889.

Having granted the royal charter to the BSAC without consulting Lobengula in any way needed to be explained and another letter was brought by a delegation of five officers and men from the Royal Lifeguards which stated:

“Since the visit of Lo Bengula’s Envoys, the Queen has made the fullest enquiries into the particular circumstances of Matabeleland and understands the trouble caused to Lo Bengula by different parties of white men coming to his country to look for gold; but wherever gold is, or wherever it is reported to be, there it is impossible for him to exclude white men, and, therefore, the wisest and safest course for him to adopt, and that which will give least trouble to himself and his tribe, is to agree, not with one or two men separately, but with one approved body of white men, who will consult Lo Bengula’s wishes and arrange where white people are to dig, and who will be responsible to the Chief for any annoyance or trouble caused to himself or his people.”

The ‘one approved body of white men’ being of course, Rhodes, represented by Rudd, Maguire and Thompson. The letter continuing: “they are men who will fulfil their undertakings and who may be trusted to carry out the working for gold in the Chief’s country without molesting his people or in any way interfering with the kraals, growers or cattle.”

Lobengula was not taken in and complained that: “the Queen’s letter had been dictated by Rhodes and that she, the Queen, must not write any letters like that one to him again.”

However Maund had now also been turned 180 degrees and was assisting to amalgamate the interests of the Exploring Company with those of the Central Search Association. This meant:

- He had to represent himself as a neutral observer not interested in personal gain and to convince Lobengula that the Rudd concession represented the best outcome for the amaNdebele nation.

- The colonial office had initially prevaricated towards the Rudd concession partly through Gifford, Cawston and Maund’s objections, but now all parties were working towards an amalgamation of interests, he had now to convince Lobengula to resist granting any other concessions.

Obtaining a Royal Charter based on the mining concession

The negative attitude to territorial expansion from the colonial office had been coloured by Britain’s experiences in Bechuanaland. A small British expedition in 1878 had led to the appointment of a Resident, the missionary John Mackenzie, but neither the British nor the Cape colony favoured a protectorate and gradually the region lapsed into disorder into which freebooters of the Boer Republics established the Republic of Stellaland and State of Goshen. In 1884 General Sir Charles Warren led an expedition to restore order and restate the boundaries, but this cost the Imperial Government one and a half million pounds and led to a dislike for any sort of further African adventures and an anxiety to avoid new expenses and responsibilities. Each year Parliament was being asked to approve sums for the maintenance of the Bechuanaland Border Police and administration, but there were no known resources and the territories only importance was that it controlled the road to the north.

In March 1889 Robinson wrote to Knutsford that neither Khama, Chief of the Bamangwato, nor Lobengula: “are at present in the least disposed to part with their sovereign rights and the discussion of any proposal based upon the acquisition by a commercial company of a sovereignty of those chiefs might, if it became public at the present time, jeopardize our relations with them.”

This led to many being opposed in principle to a royal charter in Mashonaland. Fairfield wrote: “Something is to be got which will look well enough to invite fools to subscribe to. Such a Chartered Company would never really pay. It would simply sow the seeds of a heap of political trouble and then the promoters would shuffle out of it and leave us to rake up the work of preserving the peace and settling the difficulties…Lord Gifford and Mr Cawston evidently find that their existing schemes are likely to come to little – hence this restlessness and change of proposal.”

Again Fairfield wrote: “We must soon make up our minds whether we are to allow all these concession mongers to cut each other’s throats or not. If the principals could be put in the front of the fight it would be a solution of the question that would not be without its compensations.”

Lord Knutsford’s position was ambivalent. Keppel-Jones puts it succinctly: “Knutsford and his officials wanted above all to avoid involvement, responsibility and expense; the committee [South African committee] inspired by Mackenzie [John Mackenzie the missionary] wanted the government to incur all those – through annexation and direct imperial rule.” Gladstone, Prime Minister for four terms did not wish to engage in African adventurism that resulted in negative reactions from settlors and Africans and incurred heavy expense.

However the situation changed quickly during 1889 due to several factors:

- Lord Salisbury, then British Prime Minister, and the colonial office were becoming increasingly concerned at Portuguese and German attempts to expand their territorial borders. Salisbury was not enthusiastic about imperial expansion merely for the sake of glory, but he was prepared to prevent other powers from claiming territory for which they had no justifiable historic claim. For instance in 1889, he chose Sir Harry Johnston nominally as consul in Mozambique, but with the real task of securing for Britain those territories in the interior in which Salisbury was interested and in 1889 it was the Portuguese who provided the chief threat.

- The colonial office was in favour of direct imperial administration, but this was made impossible by the treasury. Sir Harry Johnston once called the treasury: “A Department without bowels of compassion, or a throb of imperial feeling.” So the colonial office came to believe that royal charter companies provided a better option than commercial ventures. Fairfield wrote: “In consenting to consider this scheme in more detail, Lord Knutsford has been influenced by the consideration that if such a Company is incorporated by Royal Charter, its constitution, objects and operations will become more directly subject to control by Her Majesty's Government than if it were left to these gentlemen to incorporate themselves under the Joint Stock Companies Act as they are entitled to do. The example of the Imperial East Africa Company shows that such a body may, to some considerable extent, relieve Her Majesty's Government from diplomatic difficulties and heavy expenditure." Sir Lewis Michell remarked in his Life of Rhodes: “The advantage of expanding the Empire at private expense was perhaps never formulated as a policy with franker cynicism.”

- Local officials were in favour of a monopoly. Robinson wrote to Lord Knutsford stating that in Matabeleland the only alternative to the proposed monopoly was a free-for-all. “Lo Bengula would be unable to govern or control such incomers except by a massacre. They would be unable to govern themselves, a British Protectorate would be ineffectual, as we should have no jurisdiction except by annexation; and Her Majesty’s Government, as in Swaziland, would have before them the choice of letting the country fall into the hands of the South African Republic or of annexing it to the Empire. The latter course would assuredly entail on British taxpayers for some time at all events an annual expenditure of not less than a quarter of a million sterling.”

- North of the Zambezi beside Lake Nyasa the Africa Lakes Company had been formed by the Moir brothers eager to spread Christianity, Commerce and Civilization, but was in financial difficulties because of the interruption to trade by Arab slavers and Portuguese expansionism. David Livingstone’s exploration and writings had created a special place in British hearts and the Portuguese were laying claims to the region. [For details see the article The Pink Map; How credible were Portuguese claims to Mashonaland and Manicaland in 1890 under Salisbury on the website www.zimfieldguide.com ] Rhodes threw a lifebelt; a charter company would pay a subsidy of £9,000 per year and help to stamp out the slave and liquor trades.

- By 1885 the Protectorate over Southern Bechuanaland had prevented the Germans in the west from their base at Angra Pequena and the Boer Republic on the east of Bechuanaland from joining hands and encircling the Cape Colony and kept open the road to the interior. A further treaty requested by Chief Khama placed the whole of Bechuanaland to 22°south latitude and 20°east longitude, i.e. to the amaNdebele borders under British protection. The “missionary road” to the interior was saved and Rhodes proposed further expansion into the area between the Zambezi river and the Congo Free State ruled by Belgian. This included Barotseland and the territory to the east and Lewanika, with perfect timing the Lozi chief had just appealed for protection against amaNdebele raids. Minimum responsibility remained policy with the least impact on the British taxpayer, but a charter company offered a method of transferring responsibility and expense.

- Rhodes’ motivation for expansion of the empire is not examined here, but he managed to convince a number of influential newspaper editors and journalists that he had not only had an enthusiasm of the imperial dream, but that he was prepared to use his own personal fortune as the means to carry it through. They included W.T. Stead of the Pall Mall Gazette, the Rev John Vershoyle of the Fortnightly Review and Flora Shaw of The Times who between them were able to influence public opinion in favour of the proposal for a royal charter.

- Finally Charles Parnell, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party that held the balance of power in the House of Commons during the Home Rule debates of 1885–1890 was given £10,000 [“squared”] by Rhodes if their voices and votes were not directed against the royal charter in Parliament.

These factors persuaded Lord Salisbury that the expense of annexation ruled that option out; a chartered company was the only practical solution to the problem.

Creating a marriage of interests in the Central Search Association

Rhodes spent June to October 1889 in London merging his interests with those of the Exploring Company and overcoming opposition to his plans by slowly winning over the colonial office and Parliament with the support of Lord Salisbury, the Prime Minister, and the public with favourable newspaper reports.

The Central Search Association was formed on the 23 May 1889 and the Rudd concession was transferred into that company from Goldfields of South Africa. Any minerals rights obtained in Lobengula’s dominions thereafter by the original shareholders belonged to the Central Search Association.

The Central Search Association was the precursor to the BSAC and handled all the business that would eventually be taken on by the BSAC. This does not explain why the Central Search Association was not wound up when its initial purpose had been completed; Maylam suggests that it continued to rival competing concession-seekers and to protect the Rudd concession if the BSAC had gone into liquidation.

Later this article discusses the ‘big secret’ i.e. that the Central Search Association owned the Rudd concession which was bought from the Matabele syndicate owned by Rhodes and Rudd.

Lord Gifford and George Cawston who represented the Exploring Company and its holding company the Bechuanaland Exploration Company were bought off with shares and directorships in the Central Search Association which had a share capital of 120,000 one pound shares; 92,400 of which belonged to the original parties. This action united the only concession-holders with access to capital investment and political influence at the colonial office. The implications of this are discussed later as the big secret.

The Austral Africa Exploration Company had Alfred Haggard as its agent, brother of Ryder, and claimed they had a verbal concession with Lobengula and threatened to challenge the Rudd concession and were “squared” by Rhodes with shares.

| Issued Share Capital of the Central Search Association Limited | ||||

| Gold Fields of South Africa Ltd | 25,500 | B/F | 78,000 | |

| Exploring Company Limited | 22,500 | Rochfort Maguire | 3,000 | |

| Cecil J. Rhodes | 9,750 | Rhodes, Rudd and Beit | 9,000 | |

| Charles D. Rudd | 9,000 | Austral Africa Exploration Co | 2,400 | |

| Alfred Beit | 8,250 | |||

| Nathan Rothschild | 3,000 | |||

| C/F | 78,000 | Total | 92,400 | |

The authorised nominal capital was £120,000; increased by £1,000 in 1889 in recognition of Jameson’s services. Most of the issued share capital, as seen above, was owned by its founders, Directors, financiers and rival concession-seekers who had been “squared.”

United Concessions Company

In less than a year after amalgamating their interests in the Central Search Association the company was liquidated and the total share capital of this company of £121,000 was transferred into the United Concessions Company with the same shareholders and assets, including the Rudd concession, but with a greatly enlarged share capital of £4 million. This investment had been secured for the outlay of 1,000 Martini-Henry rifles and ammunition, an annual payment of £100 and a steamboat on the Zambesi river or £500.

| Largest shareholders in the United Concessions Company | ||||

| Thomas Rudd and H.D. Boyle | 336,200 | b/f | 1,160,100 | |

| Exploring Company | 293,700 | Rochfort Maguire | 39,200 | |

| Cecil Rhodes | 132,000 | Nathan Rothscild | 10,000 | |

| Alfred Beit | 112,400 | Dr L.S. Jameson | 10,000 | |

| Rhodes, C.D. Ridd and Beit | 90,000 | Harry C. Moore | 3,000 | |

| Austral Africa Exploration Company | 80,000 | Thomas Rudd | 2,500 | |

| Charles Rudd | 66,800 | Sir Hercules Robinson | 1,000 | |

| Francis 'Matabele' Thompson | 49,000 | |||

| c/f | 1,160,100 | 1,225,800 | ||

Harry Moore was an American who claimed to have an oral concession with Lobengula and was “squared” by Rhodes.

The big secret revealed

The British government only became aware that the Central Search Association and then the United Concessions Company and not the BSAC owned the Rudd concession in 1891. Colonial officials made it known that if the facts had been disclosed in 1899 the Royal Charter would not have been granted to the BSAC. The temptation to revoke the charter was resisted for the same reason that it was granted; government was not willing to cover the costs of administering the new territory.

Nothing was said in public and no action taken, although the United Concessions Company was forced to transfer ownership of the Rudd concession to the BSAC in 1893 in return for one million BSAC shares.

Letter to Lord Knutsford requesting a royal charter

Gifford and Cawston had an interview on 17 April with Lord Knutsford, just prior to the Central Search Association’s formation; after which Gifford wrote: “The objects of this company will be fourfold:

- To extend northwards the railway and telegraph systems in the direction of the Zambesi

- To encourage emigration and colonisation

- To promote trade and commerce

- To develop and work mineral and other concessions under the management of one powerful organization, thereby obviating conflicts and complications between the various interests that have been acquired within those regions and securing to the Native Chiefs and their subjects the rights reserved to them under the several concessions…

I am authorised by the gentlemen who are willing to form this association to state that they are prepared to proceed at once with the construction of the first section of the railway and the extension of the telegraph system from Mafeking, its present terminus, to Shoshong and that for this purpose a sum of £700,000 has already been privately subscribed.

Having regard to the heavy responsibilities which are proposed to be undertaken by the association, and which cannot be considered to be remunerative for some time; and whereas a proper recognition of Her Majesty’s Government is necessary to the due fulfilment of the objects above-mentioned, we propose to petition for a charter on the above lines, and we ask for an assurance that such rights and interests as have been legally acquired in these territories by those who have joined in this association shall be recognised by and receive the sanction and moral support of Her Majesty’s Government.

By this amalgamation of all interests under one common control, this association as a chartered company with a representative Board of Directors of the highest possible standing in London, with a local board in South Africa of the most influential character, having the support of Her Majesty’s Government and of public opinion at home, and the confidence and sympathy of the inhabitants of South Africa will be able peacefully and with the consent of the native races to open up, develop, and colonise the territories to the north of British Bechuanaland with the best results both for British trade and commerce and for the interests of the native races…”

Clearing the final obstacles

Other potential rivals such as the Leask syndicate made up of Leask, Westbeech, Phillips and Fairbairn and the Wood-Chapman-Francis syndicate were simply paid off, or “squared” to use Rhodes’ term. They included the Austral Africa Company whose agent was Alfred Haggard, the Matabeleland Company under Sir John Swinburne who claimed Baines’ concession, d’Erlanger and Company who held the Wood concession, the Bechuanaland Exploration Company and Eduard Lippert represented by Renny-Tailyour.

George Cawston had previously been planning a venture called the Imperial British Central South Africa Company during 1888 and Rhodes may simply have adopted the scheme as his own. In any case, this amalgamation of interests suited both parties; Gifford and Cawston would both gain financially and Rhodes’ Central Search Company would no longer be challenged by the Exploring Company.

Even Lobengula’s letter arriving in London in June 1889 rejecting the Rudd Concession did little to disturb the momentum gathering for the backing of a chartered company in Zambesia.

Floating a Chartered Company (BSAC) on the London Stock Exchange to use as a vehicle to annex Mashonaland on Britain’s behalf

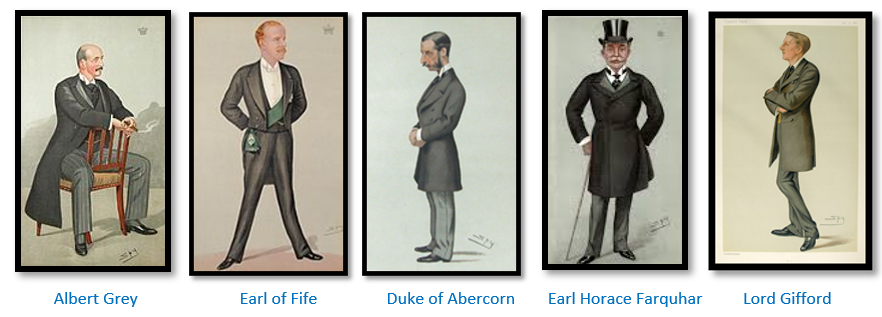

The leading promoters were Rhodes and Cawston, once opponents, now united. The Duke of Abercorn was recruited as Chairman, the Earl of Fife as his deputy. Both were appointed for their royal and political connections and not for any business acumen – in fact, both had little business experience and neither took their responsibilities as directors very seriously. Albert Grey was appointed a Director as he was an advocate of imperialism and friend of Rhodes; before and after the Jameson Raid he served as the main liaison between Rhodes and Joseph Chamberlain, later between 1894 – 1897 he would serve as Administrator in Rhodesia.

A requirement of the Royal Charter was that these three Directors were irremovable except by death, resignation or capacity.

Horace Farquhar, a friend of the Prince of Wales was appointed a Director twelve months later, despite being Chairman and a substantial shareholder in the Exploration Company – a huge conflict of interest. Robert Cecil was appointed the company’s legal representative – a move clearly designed to curry favour with his father Lord Salisbury, then Prime Minister.

The remaining Directors were Cecil Rhodes (Founder and managing director) Alfred Beit, Lord Gifford, George Cawston and Herbert Canning (Secretary)

In May 1890 Rhodes was given power of attorney to act on behalf of the directors which gave him freedom to act as he saw fit within Southern Africa without the further approval of the board of directors.

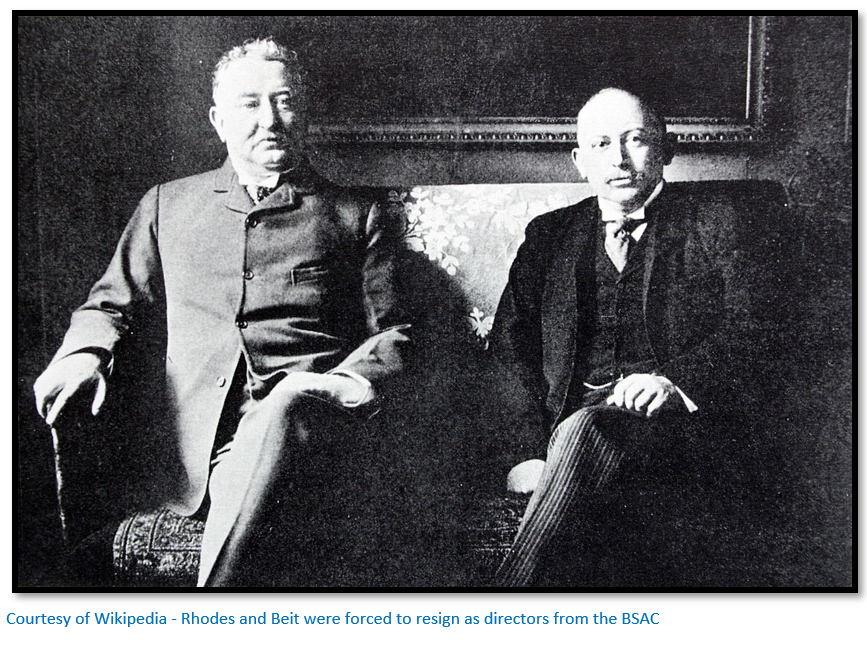

Following the Jameson Raid of 29 December 1895 carried out with the beforehand knowledge of Rhodes, Beit and Grey the Directors led by Gifford and Cawston demanded answers from Rhodes who claimed that he had given Jameson permission to assist a Johannesburg uprising, but not to start one and that he believed he had the support of the British Government against the Transvaal Republic.

However during the trial of Jameson and his officers Rhodes and Beit were forced to resign as Directors in June 1896 although they both remained large shareholders of the BSAC and continued to be involved unofficially until 1898 when they replaced the Duke of Fife, Lord Farquhar and Cawston as directors and Rhodes continued to dominate affairs until his death in 1902.

Raising the BSAC’s Capital – the shares issues to 1896

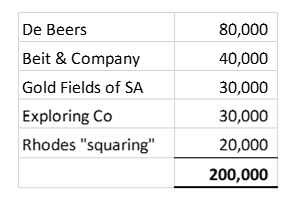

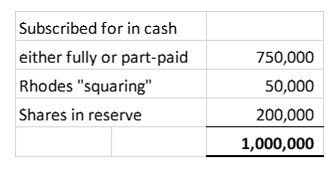

The initial capital was £200,000 as follows:

But Rhodes thought that with the objects that he had in mind for the new company £200,000 was completely inadequate and pushed for a capital of £1,000,000 paid in full or partly paid, the rest available at call. No prospectus was issued, the shares were not opened to public subscription and were not transferable for two years.

A few months after the granting of the Royal Charter, Cawston summed up the shares position as follows:

Knowing Rhodes aims including the construction of a railway, the initial capital of £1 million meant the BSAC was obviously undercapitalised; yet at the time the only assets of the company were a half-share in the Rudd concession and Rhodes needed to work the press to create the illusion that the company owned valuable assets in order to attract shareholders. No public shares were issued in the first two years. The first tranche of £250,000 shares were issued fully-paid at a par value of £1; a further tranche of £500,000 were issued with a called-up amount of three shillings per share, i.e. total of £750,000 shown above. £50,000 were issued by Rhodes and Beit to “influencers” such as Cape Colony politicians, colonial office officials and financiers when their actual market value was £4 - £5 and considerably above their nominal value and the balance held in reserve.

The nominal value of the BSAC increased several times between 1890 – 97 but without any real expectations of an increase in revenues. After the 1893 Matabele War when the price of BSAC shares rose, a million new BSAC shares were issued and distributed to shareholders of the United Concessions Company for the purchase the Rudd concession.

To finance the costs of the war and administration debentures with a value of £750,000 were issued to be repaid on 1 January 1896. As the financial affairs did not improve £500,000 in new shares were issued in January 1896 with a further £1,000,000 in new shares issued later in the year. By the end of 1896 the issued share capital of the BSAC was £4,500,000.

At the end of the article is a list of initial shareholders supplied by Keppel-Jones and it is interesting to note amongst all the familiar names those who were “squared” by Rhodes with shares in the company. Of the original two contenders for a concession Rhodes, Beit, Rudd and their companies held the vast majority (59%); Gifford, Cawston and the Exploring Company held a minority (11%)

Formation of the BSAC by Royal Charter

The final negotiations in Gubulawayo between Rudd, Thompson and Maguire are described in detail in the article Were Lobengula and the amaNdebele tricked by the Rudd Concession under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

The Queen was petitioned for a royal charter on 13 July 1899 with details of its aims that had been agreed with the colonial office; a draft charter was laid before the Queen-in-Council on 23 July and referred by Council to a committee.

Lord Salisbury's concerns of Portuguese and German expansionism in Africa, coupled with Rhodes efforts in London in recruiting powerful backers , prompted the Prime Minister to incorporate the British South Africa Company by royal charter on 29 October 1889.

The delay was caused by objections from various concession-holders that the charter would intrude on their own rights within the Tati concession, although this area was specifically excluded from the Rudd concession, and also from the final version of the charter. Many others, including Sir John Swinburne were also “squared.”

The rush to issue the Royal Charter

The urgency with which the royal charter was issued are due to two compelling factors:

- The defects of the Rudd concession which were considered earlier were on important reason. Fairfield’s comments that the amaNdebele relationship with the Mashona was more akin to raiders than rulers was nearer to the truth than the colonial office liked to admit and many thought that if the matter went to a tribunal the Rudd concession would be considered illegal. Swift action was required to settle with other concession-holders, no matter how dubious their claims and in issuing a charter.

- Secondly the objects of the BSAC now fitted closely with Lord Knutsford and the colonial office’s overall objectives for Africa, which were to keep Germany and the Transvaal Republic in check, to open up the Zambezi, Limpopo and Pungwe rivers to international trade and to defeat Portuguese claims to Lake Nyasa and the Shire river area.

Lord Knutsford wrote to the Queen’s secretary: “I am confident that a strongly constituted Company will give us the best chance of peaceably opening up and developing the resources of this country south of the Zambezi and will be most beneficial to the native Chiefs and people. Such a Company has been formed, and all the capital subscribed without going to the public.”

The legitimacy of the Rudd concession was now secured by the royal charter and backed by the colonial office making its legitimacy indisputable.

Rhodes wrote to Edward Maund, soon after reaching Cape Town; "My part is done…the charter is granted supporting Rudd Concession and granting us the interior ... We have the whole thing recognised by the Queen and even if eventually we had any difficulty with King [Lobengula] the Home people would now always recognise us in possession of the minerals; they quite understand that savage potentates frequently repudiate."

Again writing to Maund a few weeks later with the royal charter in place: “whatever [Lobengula] does now will not affect the fact that when there is a white occupation of the country our concession will come into force provided the English and not Boers get the country.”

The mandate given to the BSAC

The charter restated the objects clause of the company’s memorandum of association confirming:

- The principal activities and operations, leaving it open for this to be extended by future concessions,

- confirmed all the rights conferred by the existing concessions, and other commercial and administrative rights including making treaties, promulgating laws, acquiring economic concessions, establishing a police force, and providing at the company’s expense, the infrastructure of a new colony initially in Mashonaland (now part of Zimbabwe) but extending as far as current-day Zambia, Malawi, and Botswana.

The powers given were as wide as any commercial company, however a number of powers required the approval of the secretary of state for the colonies including:

- new concessions, or treaties had to be ratified by him,

- any dealings with foreign powers needed to be approved,

- the company was bound to carry out any suggestions from the secretary of state,

- any disputes between the company and chiefs would be arbitrated by the secretary of state,

- an annual set of accounts concerning the administration costs were required,

- monopolies were forbidden except for the railway, telegraph and banking. This was the most obvious difference between current and the old-style chartered companies.

The charter was to run for twenty-five years as a first period, and after that for ten-year terms, always subject to the right of the Crown to revoke it at any time should the Company fail to carry out the provisions, or to satisfy the Secretary of State that they were promoting the objects for which the Company was formed. Special provisions for safeguarding native interests were included and the High Commissioner for South Africa and Secretary of State were to be arbiters of native policy.

BSAC’s territory covered by the charter was left imprecise

The extent of the BSAC’s field of operations was left deliberately indefinite, in fact the northern boundary of the company was not defined showing that the colonial office was willing to give Rhodes the power to also further their territorial interests also. Rhodes himself focused his efforts on the supposed goldfield of Mashonaland and Manicaland; Matabeleland came later, but he demonstrated little interest in the territories north of the Zambezi river, although Katanga was known to have commercial deposits of copper.

Lord Salisbury did not wish to provoke the Portuguese with a declaration in the charter that the BSAC’s field of operations included territory to the north of the Zambezi river. The charter provided that the company’s “principal sphere of operations” was north of British Bechuanaland, north and west of the Transvaal Republic and to the west of Portuguese possessions.

No northern limits were given and Lord Salisbury considered that any northern extension could be granted by the colonial office at the applicable time with a simple licence addendum to the charter.

The arms of the BSAC were adopted on 15 October 1899

The lion with the elephant’s tusk symbolizes (=) Britain, the springboks = South Africa

The oxen = cattle-breeding, the ears of wheat = agriculture, the fesse wavy = Zambesi and Limpopo rivers, the three ships = overseas trade and are from the arms of the second Duke of Abercorn, the first Chairman of the company, the elephant = wild-life, the bezants = gold of Mashonaland.

The motto refers to the liberal political and economic point of view from which the colony was exploited.

A variant of the arms existed, showing the arms enclosed in a circular band, broken at the base by a ‘national spray’ of the rose, thistle and shamrock. On the band are the words “British South Africa Company and below this is a scroll with the words “Incorporated by Royal Charter”. This basic design, with some small variations, was used on postage stamps of the BSAC from 1896 onwards.

Shareholders in the BSAC

The authorized capital of the company was £1,000,000; of which £700,000 was initially called up through issuing shares. Rhodes had committed his money as well as the resources of De Beers and Goldfields of South Africa, the entity for holding his gold investments. Both companies had articles of association which included territorial expansion and commercial development of any kind – these same powers were granted to the BSAC under its royal charter. Shares were not initially offered to the public, but offered at par to friends, business associates and political figures who were helpful. These included Alfred Beit, Barney Barnato, Starr Jameson, Charles Rudd, Lord Rothschild, Sir Hercules Robinson, Frank Johnson and Frank Thompson.

The big secret kept from shareholders and the British government

The secret was that the Rudd Concession, upon which the whole edifice was built, was owned by the Central Search Association, not by the BSAC. A lease between the two entities gave the BSAC the right to use the Rudd concession:

- In return for outlaying all the development costs in Mashonaland

- Paying the Central Search Association half of any resulting profits.

This arrangement was not known by the colonial office or the public for several years, although Maylam states that Sir Hercules Robinson as a shareholder of the Central Search Association and High Commissioner must have known but kept quiet.

A constitutional conundrum

The BSAC powers of administration included not only the making of laws and their enforcement by police, but the levying of taxes, customs dues and other revenue. It is clear that there was no authority for these powers as Lobengula had been acknowledged as an independent sovereign in all the letters between him and the colonial office.

However the Rudd concession gave the company the right to "do all things that are necessary to win and procure" the minerals and to prevent the incursion of other parties either with regard to minerals or land and for the time being the colonial office was content to ignore this challenge and allow the BSAC to take what steps it needed to secure order in the new settlement.

Limitations of the BSAC

Many writers have suggested that Rhodes’ dream was to create a British zone from Cape to Cairo through the BSAC – however this was never credible; it was far beyond the resources of the company. As it was, the BSAC paid no dividends for 33 years and then only small dividends from 1924 to 1946 – see the table with dividends paid at the end of the article. In the post war period the strong demand for copper meant mineral royalties from the Northern Rhodesian mines increased substantially, as did dividends.

In the most optimistic scenario the company might have created enough of a return of mineral royalties from the Mashonaland goldfields to finance the expansion into Northern Rhodesia and Katanga, but when this did not materialise there was little funding available after constructing the railway infrastructure and the administration expenses of Northern and Southern Rhodesia.

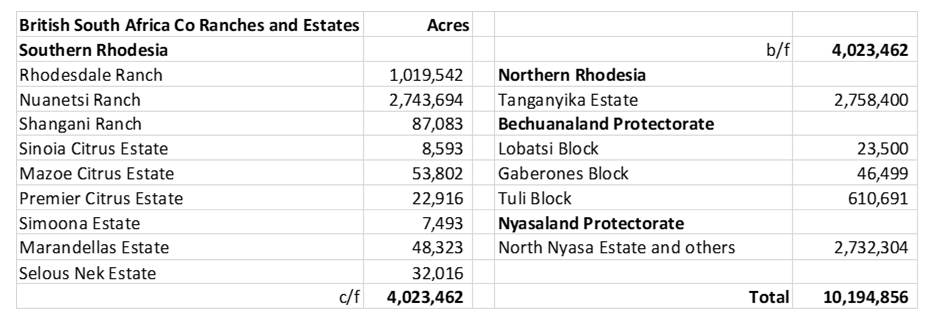

The company hoped its extensive landholdings detailed below could be turned into profitable commercial ventures.

The Royal Charter which came into effect on 20 December 1889 was for an initial period of 25 years and after being extended for a further 10 years expired in 1924.

The liquidity situation in the early years of the BSAC

Frank Johnson was paid £87,500 for the initial occupation of Mashonaland and the cost of the BSAC police force proved a heavy drain on cash forcing Rhodes to draw upon the resources of De Beers and Goldfields of South Africa. In July 1891 there was £280,000 in cash, but by December it had reduced to £144,000.

The outstanding seventeen shillings on shares was called up from shareholders; Goldfields of South Africa, Rhodes and Beit each contributed £500 per month and De Beers which had already lent £70,000 agreed to lend a further £3,500 per month and these continued for over three years.

Tensions between the BSAC and the Colonial office

- Tensions worsened between the two after the Jameson Raid; there was a fundamental mismatch between the commercial aims of the BSAC and the burden of administering its territories which were too great and outweighed its income from the royalties and rents of mining and farming and railway revenue. The company had to increase its share capital from £6 million to £12 million between 1908 – 1912 and take out loans to retain liquidity.

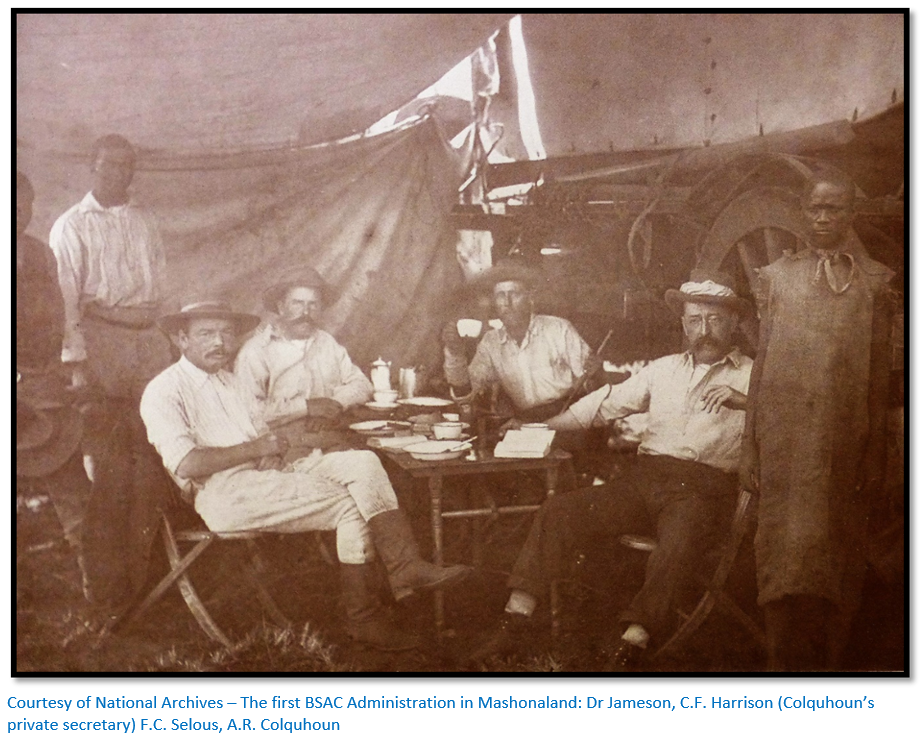

- One of the major omissions in the charter was the failure to demand the appointment of local officials. In 1889 only John Moffat combined duties in Matabeleland with those in Bechuanaland; from 1890 he was the colonial office’s resident envoy in Matabeleland although his salary and expenses were paid by the BSAC. For much of the time Francis ‘Matabele’ Thompson was the BSAC’s agent in Umvutcha and a target for much of the amaNdebele hostility against the Rudd concession both before and after Lotshe’s death. Sir Henry Loch urged that a top administrator be appointed by the colonial office, but his superiors rejected the proposal. BSAC officials were thus free to act as they pleased so long as their actions did not result in international tensions. After A.S. Colquhoun, Dr L.S. Jameson was appointed as administrator and given huge discretionary powers by Rhodes, who in any case, was too involved in Cape politics and his business interests to pay much attention and telegraphed: “Your business is to administer the country as to which I have nothing to do, but merely say ‘yes’ if you take the trouble to ask me.” After the Jameson Raid and the 1896 Rebellions or Umvukela and First Chimurenga this was partly corrected as Earl Grey, already a Director of the BSAC was appointed Administrator of Southern Rhodesia (1896 – 1898) to replace Jameson and a Resident Commissioner was also appointed with Sir Marshall James Clarke filling the first post between 1898 – 1905. Britain oversaw BSAC affairs much more closely thereafter.

- Another cause of tension was that local colonial office officials favoured Rhodes and Rudd. For an example of this partiality; the envoys Mshete and Babayane with Maund and Colenbrander arrived back in Umvutcha on 5 August 1889 and Lord Knutsford’s letter was read to Lobengula next day. On 10 August Lobengula replied, addressing his letter to Sir Sidney Shippard. Because of its contents Shippard delayed sending the letter to Cape Town until 14 October so that it only reached the colonial office on 18 November after the royal charter had been signed on 29 October 1889. Keppel-Jones states: “Shippard had proved once again that he remained a faithful ally of Rhodes.” Prior to his appointment as Resident Commissioner of Bechuanaland Shippard had been a lawyer Griqualand West and became a close friends with Rhodes…so close that he was one of the executors of Rhodes’ will.

- The relationship between Rhodes and the BSAC Directors was a difficult one – mainly because excess power was wielded by Rhodes and there was little desire to challenge him by BSAC Directors. One result of the Directors being in England and Rhodes in Cape Town was that his proximity to Mashonaland gave him greater authority as the “man on the spot.” Their timidity in challenging decisions meant Rhodes came to wield great power and did not welcome any challenges to his decisions. Galbraith says: “Rhodes became the most powerful force in the company. He did so by his own dynamism and by the quiescence of his fellow directors” and later: “With two or three exceptions, the company’s directors devoted little energy to supervision of the company’s policies. They had neither the will, nor the desire to restrain Rhodes so long as he appeared to be successful.”

- The BSAC had no legal basis for the occupation of Mashonaland or for the establishment of any kind of administration. The claim to Mashonaland rested initially on the Rudd concession which granted mineral rights, but not land rights or occupation rights. The assumption made in the royal charter was that the BSAC had obtained the agreement of Lobengula to govern Mashonaland, but in fact Lobengula quickly repudiated the Rudd concession and never gave permission to the BSAC to occupy the territory. Until the defeat of Lobengula in November 1893 the BSAC could not secure a legal basis for occupation and the British government would not permit the setting up of courts and issue laws…however, it did allow the company to issue regulations. In order to place legal weight behind the BSAC’s actions in the face of Boer threats from the Transvaal Republic the British government declared the territory a British Protectorate on 9 May 1891 by Order in Council. The High Commissioner in Cape Town then had the power to appoint all administrative officers and issue regulations, but in reality this did not happen and the BSAC continued to exercise these powers. On 10 September 1894 the Matabeleland Order in Council gave the BSAC’s administration legal authority over almost all of modern day Zimbabwe.

Other Contentious issues

- Shareholder discontent

With Rhodes’ death in 1902 and the expense of the second Boer War of 1899 – 1902 it became harder and harder to finance the BSAC’s administration expenses out of existing revenues; the country itself suffered an economic depression in the early 1900’s. The company sought permission for the growing deficit, then estimated at £7.5 million to become a public debt secured on future revenues. This was hotly resisted by citizens.

- Land ownership

The colonial office initially found it convenient to ignore the question of land titles, although it did affirm Lobengula’s rights to all of Mashonaland. Selous had acquired a land concession from two Shona chiefs which the Lippert brothers purchased and then tried to sell to the BSAC. When the company turned down the offer Edouard Lippert threatened to appeal to the German government to support the concession. The colonial office advised the BSAC to settle with him, but the foreign office advised against: “Mr Lippert is playing a game of brag” said Sir Percy Anderson.

Then in April 1891 Renny-Tailyour secured a concession from Lobengula for £1,000 and annual payments of £500 granting exclusive rights to approve land titles, establish banks, coin money and carry out trade . The actual block of land of 125 square miles was situated in the Umniati district and on the old Hunter’s Road. However the only witnesses were Renny-Tailyour’s colleagues and the IzinDuna Mshete, which made the validity of the concession shaky. Renny-Tailyour was a friend of “Offy” Shepstone, the son of Theophilus Shepstone, a long-time colonial office administrator in Natal and Lobengula may have believed the concession was for the Shepstone’s.

Lippert wanted £250,000 for the concession, but the BSAC ruled it was a fraud and Sir Henry Loch, the High Commissioner in Cape Town issued a proclamation which stated that any concession which had not received his or colonial office approval was a fraud. Renny-Tailyour was arrested at Tati, despite Lobengula’s protests that he should be the arbiter of who entered Matabeleland.

Alfred Beit thought the concession might be considered legal in the English Courts, so despite Rhodes’ misgivings about being blackmailed, he had to understand that the Imperial government would not recognise the BSAC had any land rights, only mineral rights. The Renny-Tailyour concession, however dubious it might seem, did have land rights and this would enable the BSAC to issue titles to land and to charge rentals.

Charles Rudd concluded an agreement with Lippert. If Lippert could get Lobengula to ratify another agreement which was acceptable to the colonial office then the BSAC would pay generously. He would receive the right to 75 square miles in Matabeleland with all land and mineral rights, 20,000 ordinary shares in the United Concessions Company and 30,000 ordinary shares in the BSAC plus £5,000 in cash. Lippert was to invest £25,000 in developing the area within one year.

Both the fact that Lippert was acting for Rhodes and that 75 square miles of land in Matabeleland were part of the consideration would have been anathema to Lobengula, so they had to remain a secret, as Lobengula believed Lippert was acting against Rhodes and not in concert with him. Sir Henry Loch, the High Commissioner in Cape Town ordered John Moffat, the colonial office representative in Gubulawayo to cooperate with the scheme and not give Lobengula any grounds for suspicion. “Your attitude towards Messrs. Lippert and Renny-Tailyour should not change too abruptly, though if consulted by the King you might profess indifference on the subject.”

Moffat was troubled by the deceit, but did not betray the scheme, rationalizing that Lobengula was just as deceitful as Lippert and wrote to Rhodes: “I feel bound to tell you I look upon on the whole plan as detestable, whether viewed in the light of policy or morality.”

So on 17 November 1891 Lobengula granted a new concession to Lippert which superceded Renny-Tailyour’s earlier concession and granted rights to land and to charge rentals within the BSAC’s territory for 100 years on payment to Lobengula of £500 per annum. The concession was quickly approved by Loch who approved that the land issue had been so neatly solved and advised Moffat to take: “a well-earned holiday.”

R.C. Cherer Smith wrote an article on the Renny-Tailyour concession in Rhodesiana Publication No. 38 saying that the area (north of Kwekwe and including the Sebakwe and Umniati, now Munyati rivers) was the most prolific in the country for gold bearing prospects and much litigation took place between mine-operators and the Mines Board regarding gold royalties. Only in 1918 after endless delay did the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council rule that the land had been acquired by conquest and as such was owned by the Imperial Government and held by the BSAC only as an agent.

The Privy Council ruled that land titles given by the BSAC administration were valid; but that any money received on sales as stamp duty, rents or royalties were should be treated as administrative and not as commercial revenues. As part of the 1923 settlement, Crown lands were transferred from the BSAC to the Southern Rhodesian government for £2 million.

- Mining royalties

The bait dangled in front of early adventurers to the country was the possibility of a “second Rand” – a treasure house of riches. All the pioneers were promised land and gold claims and even those not interested in farming were attracted by the prospect of finding gold whose existence had been so fully described by Karl Mauch and Thomas Baines. [See the article Thomas Baines and the Hartley Hills goldfield under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] The BSAC never envisaged raising capital for mining, but rather that individuals and syndicates would raise the financial resources to do the mining development and the BSAC would collect the royalties.

It soon became evident that Mashonaland had little alluvial gold and that mining the quartz reefs required financial capital. This disappointment was covered up in the early years by exaggerated assay and sample reports; indeed in the early years there was much more speculation in mining shares than in actual mining itself – eventually there was a reaction and nobody would touch Rhodesian mining shares despite Rhodes’ best attempts to feed the press with fresh stories of Mashonaland’s wealth.

Lord Randolph Churchill on a brief visit was particularly scathing about gold prospects in Mashonaland. [See the article Lord Randolph Churchill’s visit to Rhodesia in 1891 under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Initially gold mining legislation was aimed at large companies with financing on the London and European stock exchanges and 50% of the shares was claimed by the BSAC. But the combined effects of the Jameson Raid followed by the Rebellions (or Umvukela or First Chimurenga) and then the second Boer War brought the infant mining industry close to ruin. Of the twenty-two best known mining and development companies listed in local newspapers, most suffered share declines of 90%.

In response in 1902 the BSAC reduced its share of vendors shares from 50% to 30% and in the case of companies crushing less than 750 tons per month this was reduced to a 2.5% royalty only. The Chamber of Mines argued that even this was not enough and pressed for the abolition of the BSAC’s right to 30% of a company’s shares.

At last by 1908 the BSAC conceded that most gold prospects were best worked by smallworkers and came to an uneasy compromise. By 1909 there were over 500 smallworkers who developed their properties and if they showed promise generally sold out to larger operators with sufficient working capital to develop the mines. In order to encourage claims to be developed the BSAC introduced an inspection charge if development work was not carried out.

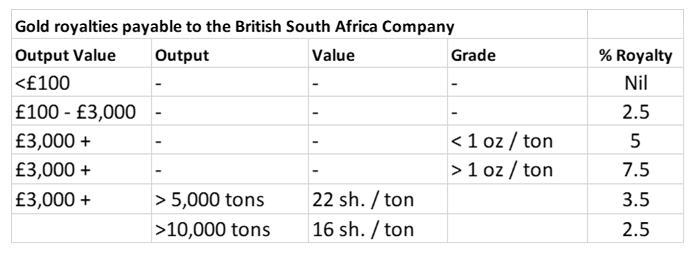

The 1908 Government Gazette introduced a sliding scale of royalty charges.

Gradually gold production increased, but the Chamber of Mines constantly argued with the BSAC to reduce royalty payments until 1932 when the Southern Rhodesian government bought the mineral rights in its own territories for £2 million.

- Conflict of aims within the BSAC

In its early years amongst the BSAC’s aims was the advancement of David Livingstone’s three C’s – Christianity, Commerce and Civilisation. However, most of the directors were pre-occupied in making profit which also conflicted with the conditions of the royal charter which gave the company the responsibly of administering the new territories. This manifested itself in the dismissal of A.C. Colquhoun, the first Administrator, who accustomed to the bureaucracy of India, but found himself in Mashonaland with almost no support staff…Galbraith writes that: “In 1893 Jameson’s staff consisted of less than twenty administrative in a territory of approximately 110,000 square miles.” In 1908 Colquhoun set out his task at a meeting of the Royal Colonial Institute: “Among the steps to be taken were the formation of a headquarters at Salisbury, the establishment of postal communication, the laying out of townships, the creating of mining districts with commissioners, the dealing with applications for mining rights and licences, the adjustment of disputes between the settlers, the establishment of hospitals, the preparation of mining and other laws and regulations, the initiation of a survey, the opening out of roads to the various mining centres and the despatch of missions to the various native chiefs.”

Internal disagreement soon arose; Colquhoun might be the Administrator, but Dr Jameson was Rhodes’ alter ego and J.A. Edwards in his article Colquhoun in Mashonaland: A Portrait of Failure quotes Major Leonard writing at Tuli in June 1891: “Speaking of Colquhoun and Jameson, Graham informs me that, in the first instance, they were great friends. But afterwards, on their way down to Manica Jameson tried to take the administration of affairs into his own hands and so they fell out.”

- The British Government would not sanction loans for infrastructure development

As raising funds for public works within the country were not permitted even the construction of vital infrastructure such as roads and bridges had to be done out of revenue funds – this was a distinct handicap for a country in its early development stage and contributed to the next problem.

- Administration of Mashonaland

Both directors and company officials had little experience in running the administration of a new and colonial administration. Their principal aims were to preserve law and order, to provide a process for gold prospecting, to collect in as much revenue as possible and to prevent conflict between the races. They wished to present an appearance of efficient administration in order to limit interference by the colonial office and to keep administration expenses as low as possible.

Hugh Marshall Hole comments: “mining and revenue officers were…chosen from the material at hand and…by the time the first settlers began to appear from the south a rough-and-ready system of administration was…in existence.” Many of the Pioneer Corps were appointed as mining commissioners and magistrates.

The BSAC was not directly involved in mining; its revenues were to be derived from the revenues of private and publicly-owned mining companies. However as little revenue was collected in the early years the company’s cash finances dwindled rapidly.

The responsibility of maintaining the BSAC Police force created a heavy burden on the company which was not generating any revenue in 1891. At the end of 1890 the police force consisted of 650 men, each of whom cost approximately £300 per annum, or a total of £195,000. The Directors told Rhodes this expenditure must be reduced as by July 1891 the BSAC only had cash reserves of £280,000 and no sources of revenue were in prospect. Accordingly the police force was reduced to 100 men by the end of 1891 and to 40 a year later.

Mention of the Pioneer Column’s cost of £87,500 has already been mentioned; extending the telegraph line to Salisbury cost £93,000. Railway costs were deferred until the Kimberley-Vryburg section which was undertaken by the British and Cape governments was completed in December 1893. The next section to Mafeking only began in 1893; the Matabeleland extension only began in 1895 and reached Bulawayo at the end of 1897. However, roads needed to be constructed and buildings constructed.

The BSAC report for 1889 – 1892 lists twenty-four employees occupying thirty-five positions and Maylam states they were: “a thin layer of men was spread unevenly over a large area, many fulfilling a range of functions.” These included: five Magistrates who were also Marriage officers, the Chief Magistrate was also the Administrator; five Justices of the Peace, seven Field Cornets, five Mining Commissioners, five District Surgeons, a Surveyor-General and acting Post-Master General; many of whom served dual roles.

By 1892 there were four settlement areas of Tuli, Victoria, Umtali and Salisbury each with a Magistrate and District Surgeon. The five Mining Commissioners had responsibility for Victoria, Umtali, Mazoe, Lomagundi and Umfuli.

The BSAC reports note 1,000 settlers in 1890, by October 1893 this had risen to an estimated 3,000. 500 hundred farms had been granted, but only 13 land-titles had been issued and 69 certificates of land-rights.

Hut Tax

The imposition of a hut tax on Africans was important both as a source of revenue for the BSAC and as an inducement to enter the formal labour market. Requests were made for its introduction several times to the colonial office, but only approved in 1894 when it created many complaints. A Chief Native Commissioner with eleven assistant Native Commissioners were appointed to administer the system.

BSAC shares