The Zeederberg Coach Company and the first passenger services into the country

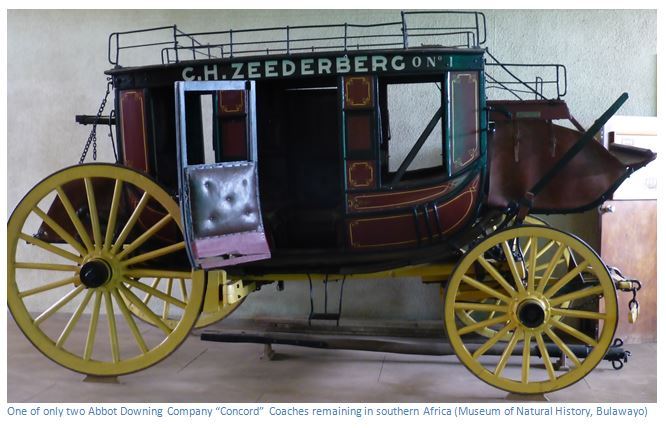

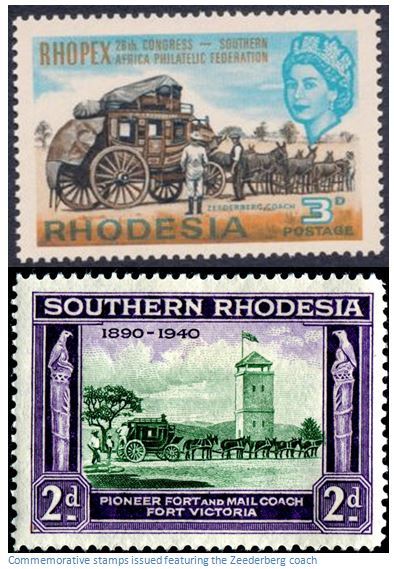

Doel Zeederberg used passenger coaches built by the Abbot Downing Company based in Concord, the capital of New Hampshire in the USA. This company started coach building in 1827 and disbanded after 20 years in 1847; but then resumed from 1865 until 1919. The Company introduced the leather braces to give a swinging motion to its coaches, instead of the jolting up and down of the spring suspension. Their Concord stagecoaches were built so solidly it became known that they didn’t break down, they just wore out!

An American authority described the coach as resembling "the English coach of the 18th century ... The ample body, almost egg-shaped, was a fine piece of joinery. It rested lengthwise on braces, each of several leather strips. These helped to absorb shocks which would otherwise affect the horse team. Concord coaches weighed 2,500 lb. (1,134 kgs) with each wheel spoke hand hewn from clear, super-seasoned ash; each was fitted into the hub with a nicety that would have done honour to the finest cabinet-maker’s art."

In 1967 a wheel was found near Tuli by the BSAP and nearly all the spokes were in still place, not even our termites could get through them! The Concord Coaches had space for 6 passengers inside and 6 more on the top and next to the driver.

According to C.K. Cooke, only two of this type of Concord coach is known to survive in southern Africa, the one above at the Natural History Museum in Bulawayo and the other in the Museum Africa in Johannesburg. Cooke says Zeederberg’s closed their business in 1930 and this coach was sold in 1932 to Bulawayo Municipal Council for £25 and used on pioneer and other anniversaries, the last occasion being in 1950 on Bulawayo’s 60th anniversary celebration. It was then housed at Government House, but its condition deteriorated and in 1964 it was sent to the Natural History Museum (then the National Museum) for repairs and display. Cooke says it was lifted into position on the second floor by Messrs. Fox and Bookless (Pvt) Ltd who took over Zeederberg’s business, Mr Bookless being Zeederberg’s book-keeper, then general manager until its closure.

Roger Summers says this Concord coach is numbered 566 under the jump seats, but number 538 appears on an iron plate at the front of the fore carriage. The rough treatment these coaches received most probably resulted in parts being pirated from other coaches. Both the two coaches from which this coach was assembled were shipped to George Heys and Company in 1888 from New York. George Heys ran passenger and mail coach services from Cape Town to Kimberley and from Johannesburg to Pilgrims Rest and other towns in the eastern Transvaal, including Pietersburg (now Polokwane) The two coaches were probably bought when George Heys stopped operating on this route to Pietersburg after 1895.

Zeederberg’s bought other coaches in South Arica, and also imported four Concord coaches directly from the Abbot Downing Company in the USA, but none appeared to have survived. One was written off in an accident and two were burnt by an amaNdebele Impi in 1896 between Gwelo (now Gweru) and Bulawayo.

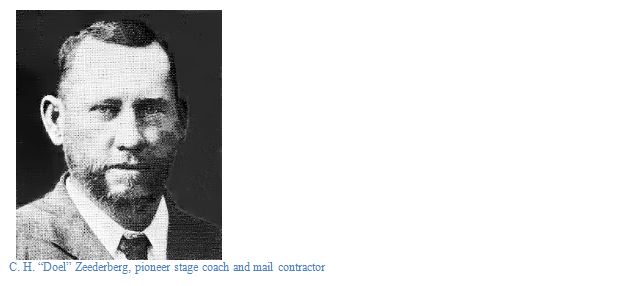

The Zeederberg Coach Company was a South African horse-drawn mail and stage coach service which began in 1887 when Christiaan Hendrik Zeederberg, or “Doel” Zeederberg as he was known, took on his three brothers Dolf, Louw and Pieter as partners and started the first mail-coach route between Johannesburg and Kimberley. In 1890 they added a service between Pretoria, Pietersburg (now Polokwane) and the gold rush town of Leydsdorp, now a ghost town, south of Tzaneen. After 1896, the Zeederberg Coach Company operated only north of Pietersburg and on the internal routes in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe)

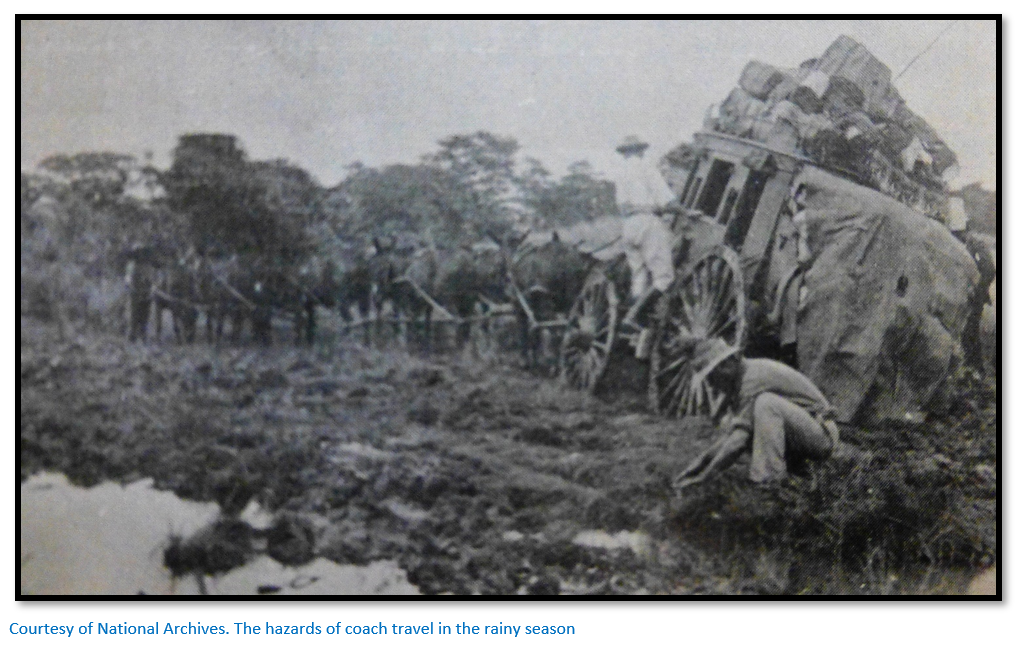

It was the occupation of Mashonaland and the tremendous demand for transport north of the Limpopo River that resulted in Cecil Rhodes commissioning Doel Zeederberg to survey a coach service in Rhodesia. Before 1891 the ox-wagon was the only form of transport within the country. The rainy season of 1890 was extremely heavy and for some months any northward movement beyond Fort Tuli was practically impossible. Wagons were stuck hopelessly in the black vleis, or on the banks of the flooded rivers, where in the absence of adequate shelter, food and medicines, many young troopers of the BSA Company police died of exposure and malaria. Mashonaland became effectively was cut off from the outer world from December to February, 1891.

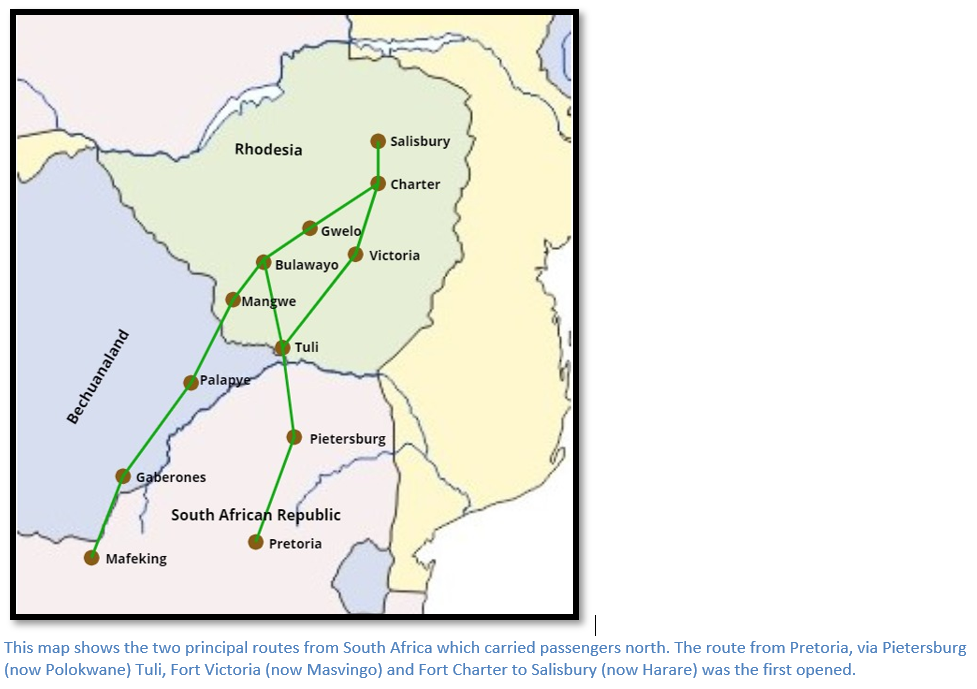

In April 1891 the Zeederberg coach company inaugurated a route from Pretoria to Pietersburg (now Polokwane) and then on to the hotel at Fort Tuli, then to Fort Victoria and Fort Charter and finally Salisbury.

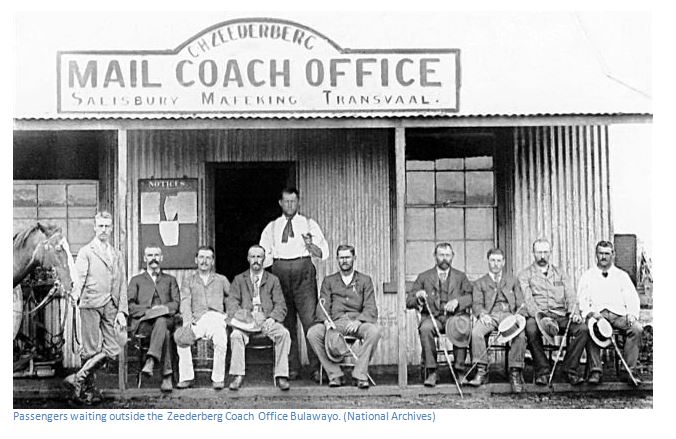

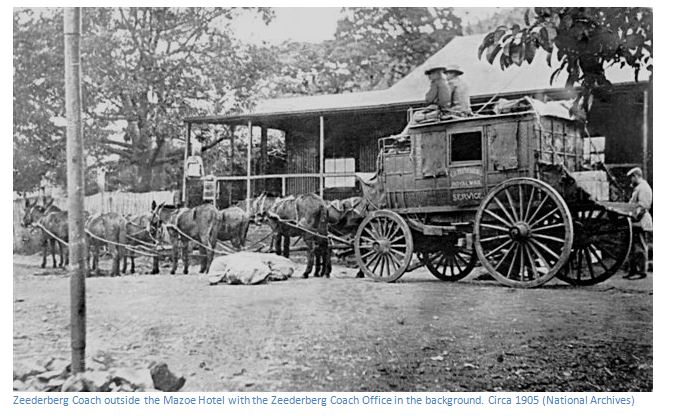

Zeederberg’s were paid £4,500 annually by the BSA Company and became the official mail carriers replacing the police mounted despatch riders. To incorporate Mashonaland routes, Zeederberg had to build various pontoons over the rivers, including the Limpopo River and set up staging posts. The company bought a number of wood and iron buildings from the British army in colonial India which had become ‘surplus to requirements’. They were shipped out to South African and from there to the newly occupied territory of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) The buildings were all identical and made of corrugated iron and were moved to the coach sites where they were reassembled to be used as coach offices.

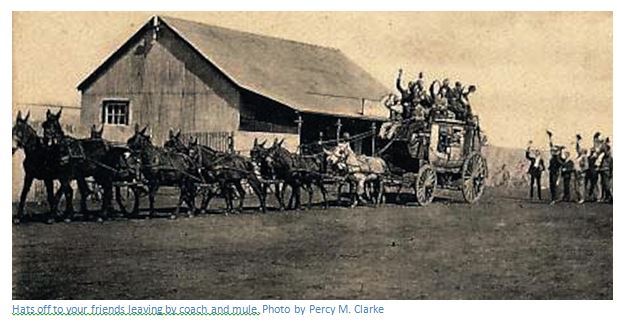

The teams of ten mules were changed every 10 – 15 miles (16 – 24 kilometres) and the coach houses had to have enough animals to supply fresh teams for up to 4 – 5 coaches each day. At times the Company had up to 400 oxen, 300 horses and 600 mules. Mules generally provided the power, because “Dikkop,” a cardiac form of horse sickness was very prevalent in the early days and good ‘salted’ horses cost up to 10 times the price of a mule. Zeederberg once used a span of trotting oxen, and when mules were very scarce, he even tried to train zebras, but they lacked the necessary stamina and he soon abandoned their use

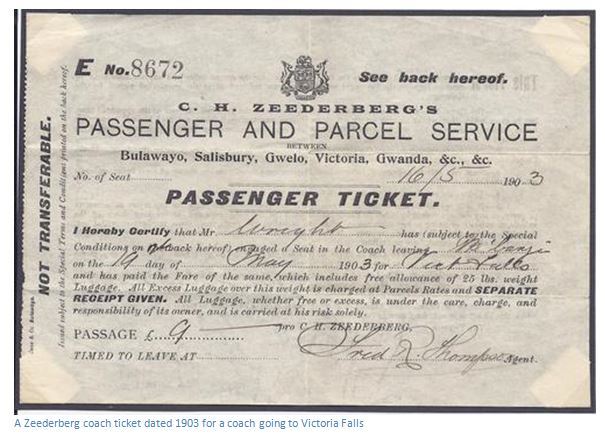

The rate of travelling, including stoppages to change the teams, was not much more than six mph (10 kilometres per hour) Fares were high, ranging from 9d to 1/- per mile and luggage allowed per passenger ranged from 25 –40lb (11 – 18 kgs) and every additional pound weight was charged at 6d – 1/6 according to the distance travelled. The "Guide to Southern Africa" for 1893, quotes the fare from Tuli to Salisbury as being £15 with the trip taking 14 days.

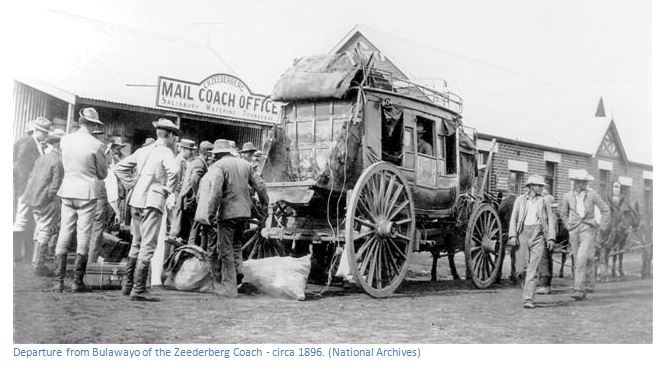

A nineteenth traveller could journey in comfort by train from Cape Town, Port Elizabeth and East London to Mafeking, the end of the railway line, and then travel by Zeederberg Coach to Bulawayo. At the time, the only regular service covering the 850 kilometre journey to Bulawayo was by the weekly Zeederberg coach. The journey was scheduled thus: Boulder pits - Monday midnight, Gaborone -Tuesday 5 am, Palapye - Friday noon, Tati hotel - Sunday 6 am, Mangwe Pass - Sunday midnight, Bulawayo - Monday 9 pm.

The daily coach service left two hours after the arrival of the train. The Concord coaches carried up to twelve passengers with room on top for mail and baggage and were usually drawn by ten mules. The uncomfortable journey to Bulawayo meant changing mules at post stations every 25 kilometres or so and took five to six days when the mules were in condition, but frequently longer. They could cover 240 kilometres in a 24-hour run, depending on the weather. C.K. Cooke states the fare on 5th June 1895 between these points was £45.

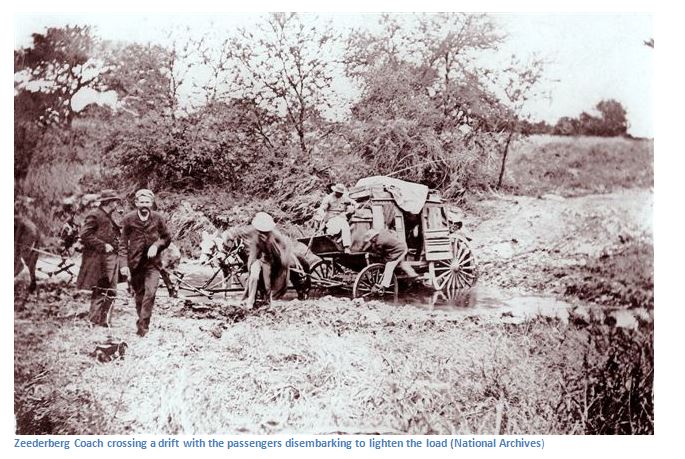

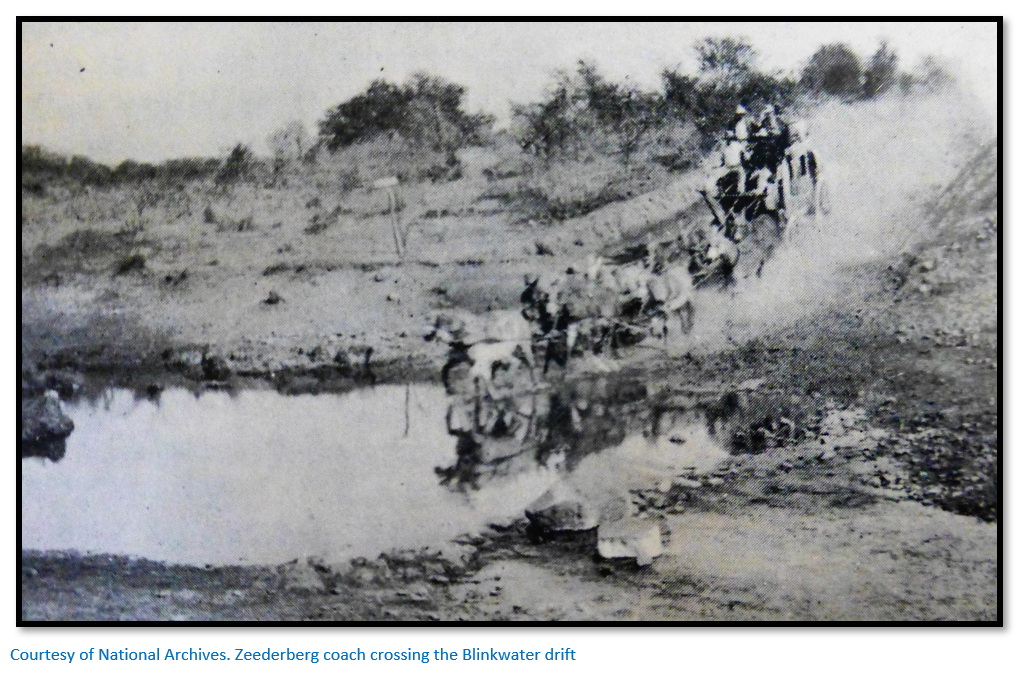

The seats were only thinly padded with the two middle seats having only a three inch (8 cm) strap as a back-rest. A wide strap stretched from side to side in front of the passengers to prevent passengers being thrown around when the track became rough, or the wheels hit a tree stump. Tracks were rough, rivers flooded, wild animals terrified the mules and accidents, such as wheel coming off, were common. Passengers were expected to help out in such an event.

A journey through Bechuanaland was described by (later Colonel) R.S. Godley in 1896: “Our road from Mafeking ... lay along the old coach road .... On this road ... coaches, with their spans of twelve mules apiece, used to travel with passengers and mails. Such coaches were huge ‘Buffalo Bill’ affairs, swinging on enormous leather springs and carrying twelve passengers, the driver, and a Cape boy to assist him. Teams were changed every seven or ten miles ... A Journey in one of these conveyances meant days of trial and tribulation. Passengers were of all sorts and conditions. Ladies of doubtful reputation, commercial travellers, prospectors, business men, and parsons were packed like herrings for days on end. Inside there were no room to move or stretch one’s legs; one was also choked with dust. Outside one was surrounded by mail bags, and exposed either to glaring sun or torrents of tropical rain.”

A similar coach journey is written by Lord Randolph Churchill: -“This kind of coaching is an experience which at the present day can only be tried in Africa. The coaches themselves are the most curious productions of human skill. Intended to hold twelve passengers inside, half-a-dozen outside, besides large quantities of heavy baggage, they are constructed of very solid materials hung upon thick springs of leather, and present the most unwieldy, lumbering and old-world appearance. They are drawn by ten or twelve mules or horses, harnessed in pairs. Two men are required to guide the team, the one holding the reins, the other the long whip, with which he can severely chastise all but the leading pair. When driving a team of mules the whip is in operation every minute, constant flogging alone inducing these stubborn animals to do their best. At times one of the drivers is compelled to descend from the box and run alongside the team, flogging them all with the greatest heartiness and impartiality. “In spite, however, of all this effort and apparent harsh treatment, an average speed of about six miles is all that can be realised. Roads there are none; deeply rutted tracks are followed. When the ruts get too deep for safety the track turns slightly aside, and to such an extent does this sometimes occur that in places the track occupies a width of a quarter of a mile or more. Swinging, bounding, jolting, creaking, straining over this extraordinary route, the coach pursues the uneven tenor of its way, sometimes labouring and plunging like a ship at sea, constantly heeling over at angles at which an upset seems unavoidable; now descending into the deep bed of a ‘spruit’ (creek), now sticking fast in heavy ground, now careering over masses of rocks and stones. The travellers, all shaken up inside like an omelette in a frying-pan, never cease to wonder that the human frame can endure such shaking, or that wood and iron can be so firmly riveted together as to stand such a strain. It may be mentioned that the life of a coach does not exceed two years, that upsets are frequent, and casualties not uncommon.”

Internal coach services became of vital importance in the development of the country. For instance, in 1901 at Bindura, Walter Thurlow built a thatched building with a hitching post at the Kimberley Reefs which became a staging post for the Zeederberg coach service to Abercorn (now Shamva) The next staging post built in 1902 towards Salisbury (now Harare) belonged to Arthur Trusson and whilst a replacement team of mules was being inspanned, passengers could wash and get a simple meal and a drink.

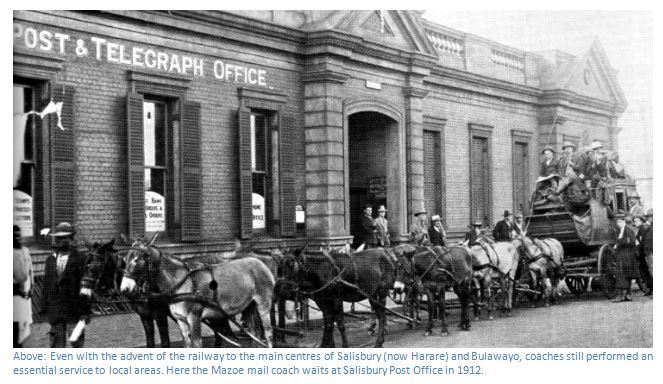

Coaches left Salisbury (now Harare) from the Zeederberg Coach Office, next to the Commercial Hotel, later the Grand, and would buy provisions for the road and wait on benches outside for departure time. By 1913 the railway had reached Shamva and regular coach services ended. Thurlow’s staging post became the hotel, Kimberley Reefs became Bindura and as production increased at the Phoenix Prince Mine, the hotel became the mine single quarters. In 1968 they were renovated and became the Coach House Inn, and for many years, the social hub of Bindura.

In 1896, most (>90%) of trek oxen fell victim to the severe rinderpest epidemic that swept across southern Africa. During the Matabele Rebellion, which began in March 1896, Zeederberg coaches were the sole means of transportation between Bulawayo and the outlying settlements, and even went as far as Pietersburg for supplies for the local Volunteer and the Imperial Forces . One coach, with nine passengers, was attacked in a running fight between Shangani and Bulawayo. The mules were eventually run to a standstill and were killed. The driver and passengers ran to the top of a nearby kopje and prepared to defend themselves. With night coming on their situation was bad, but they were saved by the timely arrival of a patrol under Col. Napier on its way to Gwelo (now Gweru) The coach, however, had been burned to ashes.

The arrival of the railways at Bulawayo in 1897 was the beginning of the end of the coach service; although internal travel within the country to places like Bindura and Shamva continued by coach.

During the second Boer War (1899-1902) Zeederberg’s mail transport contracts were suspended and its resources put at the disposal of the local administration British Government. Canadian and Australian troops and their equipment were transported from the railhead at Marandellas via Charter and Gweru to Bulawayo to assist at the relief of Mafeking.

The Zeederberg network extended into Manicaland, with a Zeederberg station building and a stable located just behind the Umtali Club complex, at No 81 Third Street, Umtali (now Mutare) and was used as a house well into the 1960's, after the Zeederberg Coach Service was discontinued.

Doel Zeederberg died in 1907, but for many years, "Zeederberg's Garage", in Esigodini was owned and run by Mr. A. ”Cook” Zeederberg, a son of Doel.

On a spring morning in 1927 the people of Umtali heard the piercing note of the post horn for the last time. Four coaches, each drawn by twelve mules, bumped and rattled out of town en route to Bulawayo. They were making Zeederberg's last run after more than thirty years of service in rain and shine throughout Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe)

Motor transport and the railways finally ended the days of coaching, but they had provided an amazing service, Rhodes himself said that no other individual had done more to open up Rhodesia than Doel Zeederberg.

Arthur Leonard commanded “E” Troop of the BSA Company Police which was stationed at Fort Tuli, so he did not accompany the pioneer column into Mashonaland. Here is his amusing description of the journey from Kimberley starting on the 4th May 1890 in a post cart which began at the Kimberley Post Office with seven other passengers, a driver and leader and over a ton of luggage and mails.

Of the passengers, one was abnormally stout, another enormously tall, a third a living skeleton, while the rest of us were of the ordinary run of average humanity. The cart had room enough for two to travel with tolerable comfort, and four with a certain amount of discomfort, but nine of us, were a trifle too much for it, packed sardine fashion or squashed into pulp like mashed turnips.

However, after much glaring and inward criticism of each other, we were soon on speaking terms. I was wedged in-between two extremes. On one side the stout man taking up the whole seat; on the other the skeleton jammed against the side of the cart and I was in the middle of it. Never has a pancake undergone the flattening process more vigorously, and what awful salient, in the shape of elbow and knee-joints which ran into me like blunt razors.

The bottom of the cart was strewn with small boxes and parcels, and I found my knees on a level with my chin, but where my feet were stowed heaven alone knew, except occasionally when a terrific attack of pins and needles reminded me very forcibly of their actuality. I will spare you further detail, except to say that never in the whole course of my life have I received such a jolting. The country was flat and interesting and the places we passed through – Barkley West, Taungs and Vryburg were small and miserable and they reached Mafeking on the morning of 7th May.

Here Sir Fred Carrington briefed on what was going on – little more than I learnt in the secretary’s office in Kimberley, which was practically nil. Indeed, the prevailing ignorance of the country and of things in general is astounding. After six hours, which consisted of trying to clean ourselves and running about all over Mafeking seeing various people and securing stores, we learnt our reduced party of five passengers were to go the next one hundred eighty kilometres over hilly country in a smaller cart. We had not driven many miles before we found that we had jumped from the frying-pan into the fire

Not only was the cart smaller, but its springs were broken, and to make matters worse, bolstered up by blocks of wood. Oh our poor nerves! How we trembled in anticipation at every stone and stump we saw in the road – and their name was legion – and when we struck, which was frequently, curses and imprecations thickened the air. Speaking for myself, never, while memory lives, shall I forget those jars and bumps. Our teams were now composed of mules – for the horses had long since succumbed to the deadly horse sickness – and wonderfully surefooted and nimble they were, especially in the dark, whilst it was a marvel to all of us how on earth the drivers managed to keep to the road, such as it was, during the night.

After Kanya, we resumed our journey, but we had not driven on half a mile, when a small rock proved too much for us, and over we went. Luckily no one was hurt…that evening we reached Molepolole… and the following morning Mashindi’s. On again, for we never stopped more than two hours at an outspan and the evening overtook us at Lonetree Pan and we drank tea brewed out of the very muddy water of the pan with a relish that would have amused our London Club friends.

That night was the worst we experienced…as the road was strewn and studded with boulders and stumps, broken also by ravines and undulations innumerable. Sleep all along had been out of the question, but some of us had been able to snatch five minutes nap over a level stretch, but the bumping and jolting was simply terrible, and to add to our misery, the driver, who had been over seventy hours in harness, kept falling asleep from sheer exhaustion. But like everything else it came to an end, morning found us at Miller’s store, while by dusk we arrived at Notwani unction, on the Crocodile River.

Here we were turned into a still smaller conveyance, a kind of Scotch cart with a canvas hood to it. We were still seven, not atoms, but shreds of humanity, what was left of us. The stout man alone seemed to have retained his substantiality, but the skeleton was thinner than ever…as for me, I felt more like a letter-bag that had been sat upon with a vengeance, and the others resembled parcels and packages that had been flattened beyond recognition. However, get in and get on we did, but this time with bullocks instead of mules, and at a steadier, if slower, pace. The next morning, as we turned round a bend in the road, we were delighted to see, patches of white that turned out to be the tents of the Pioneers who are concentrated here at Cecil camp, close to the Crocodile River, where they did us a good breakfast.

The morning of the 13th May found us at Pilapwie. The huts were only native built, and far from luxurious, but Messrs. Harman and Moffat made up for it by their excessive kindness. I was shown into a hut and a bath given me. Oh! The luxury and the joy of that tub, the first since leaving Kimberley; for water was scarce at Mafeking, and we had only been able to get a wash down; while on the road the stoppages had been so short, and the cold so intense, that every available moment was snatched by us for food and sleep.

Acknowledgements

P.J. White. How "Wild West" coaches opened up Rhodesia. Rhodesiaheritage.blogspot.

Rhodesia Calls Magazine of May-June 1973

Wikipedia

C.K. Cooke. The Zeederberg Coach. Rhodesiana Publication No. 32. March 1975. P43-47

R. Summers. The Bulawayo Zeederberg Coach: its History and Restoration. Arnoldia Rhod. 3 (11) 1967

Major A.G. Leonard. How we made Rhodesia. Books of Rhodesia. 1973

E.A. Logan. The Coach House Inn – Bindura. Heritage of Zimbabwe Publication No.23. 2004

A. Sillery. Founding a Protectorate. History of Bechuanaland 1885-1895. Mouton, London. 1965

Lord R.S. Churchill. Men, Mines and Animals in South Africa. Books of Rhodesia. Bulawayo. 1969