A Visit to Lobengula at the King’s Kraal or Umvutcha in 1889 – Lieut-Col. H. Vaughn-Williams recalls his stay after 57 years

Introduction

Lieut-Col. H. Vaughn-Williams’ book A Visit to Lobengula in 1889 was published 57 years after he visited the King’s Kraal or Umvutcha as a nineteen year old medical student with his elder brother Arthur, who was hoping for a concession from Lobengula. He was there nearly three months from August before leaving to resume his medical studies in Edinburgh in late October 1899.

It was a very tense time as the Rudd Concession had been signed on 30 October the previous year and it was widely known that the British South Africa Company under Rhodes was planning the Pioneer Column into Mashonaland with a police escort in 1890 – the amaNdebele majakas were keen to wipe out all the white men in Matabeleland who they believed would take their country, but throughout Lobengula protected them from harm. Vaughn-Williams writes, “the white people always had a square deal from Lobengula” and “I never heard of Lobengula doing harm to any white man.”[i]

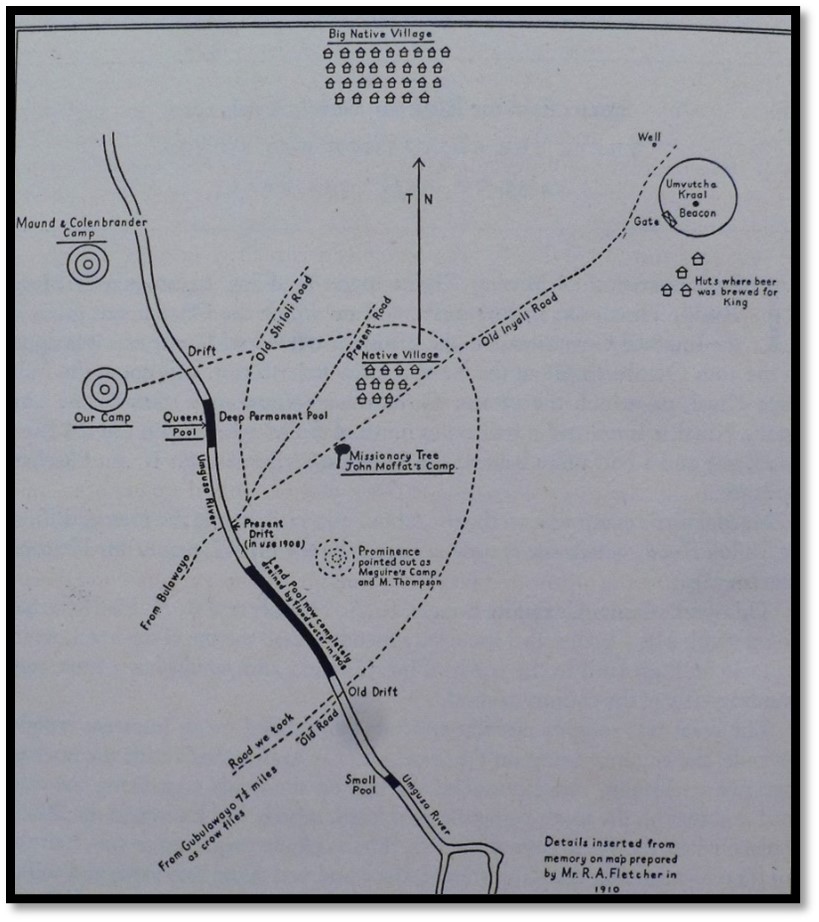

Vaughn-Williams returned to Bulawayo in 1938 planning to visit the Umvutcha, but nobody knew where it was, not even the Curator at the Museum! They thought it was at the Governor’s residence, now State House, but this was the site of Gubulawayo – the pantry of State House had been the site of Lobengula’s house built by John Halyet in August 1884. Eventually he spoke to some of Lobengula’s old warriors who knew the King’s Kraal or Umvutcha had been situated two kilometres north of the Umgusa river and a few of the old-timers such as Tom Meikle and R.A. Fletcher also knew the site: it was Fletcher who took Vaughn-Williams to the old King’s Kraal and drew the sketch map included in this article.[ii]

The kraal was sited on the old Shiloh Road and was the favourite summer residence of Lobengula. At the time all the early concession-hunters were camped nearby under the eye of Lobengula. Alexander Boggie, Matabele Wilson, James Fairbairn and James Dawson were all camped 500 yards above the drift. Rudd, Maguire and Thompson camped at Charter Camp about 1,000 yards east of the drift.

The Rudd Concession itself was signed at the Umvutcha (not at Gubulawayo) an event that led to Lobengula’s downfall after the 1893 Matabele War and the invasion of Matabeleland. There are many articles on this subject on the website www.zimfieldguide.com. It seems remarkable that although the site was declared National Monument No 105, no memorial and plaque was ever erected at this significant and historically important site.

We arrive at Gubulawayo and go on to the King’s Kraal or Umvutcha

Vaughn-Williams describes the journey from Gubulawayo to the King’s Kraal as follows: We started off with our three wagons the following afternoon and owing to spruits and rough ground, we had to go some miles round to get to our destination. We reckoned we covered about 12 miles. Now the spruits are bridged it is only about 7 miles. Half way we met (Francis) ‘Matabele’ Thompson, as he was known, riding a big black horse. He was a biggish thick-set man with a rather swarthy complexion. Arthur knew him and introduced me. But he did not seem very friendly. There was so much jealousy between the few white men who were up there at the time; all trying to get something out of Lobengula and afraid someone else would get what they wanted. Matabele Thompson represented Rhodes’ interests. In fact, he and Rudd accompanied by Rochford-Maguire, had obtained the concession the previous year from Lobengula (on the 30 October 1888) to mine gold and protect themselves in Mashonaland. Rudd having left some months back and Maguire a little later. Thompson was left in charge while Rhodes was arranging with the British government to get the Chartered Company into being. Thompson had lived in this country in fear of his life for nearly a year and it was getting on his nerves. He showed it in his manner, being jumpy and nervous. He lived in a camp some way from the King’s Kraal.

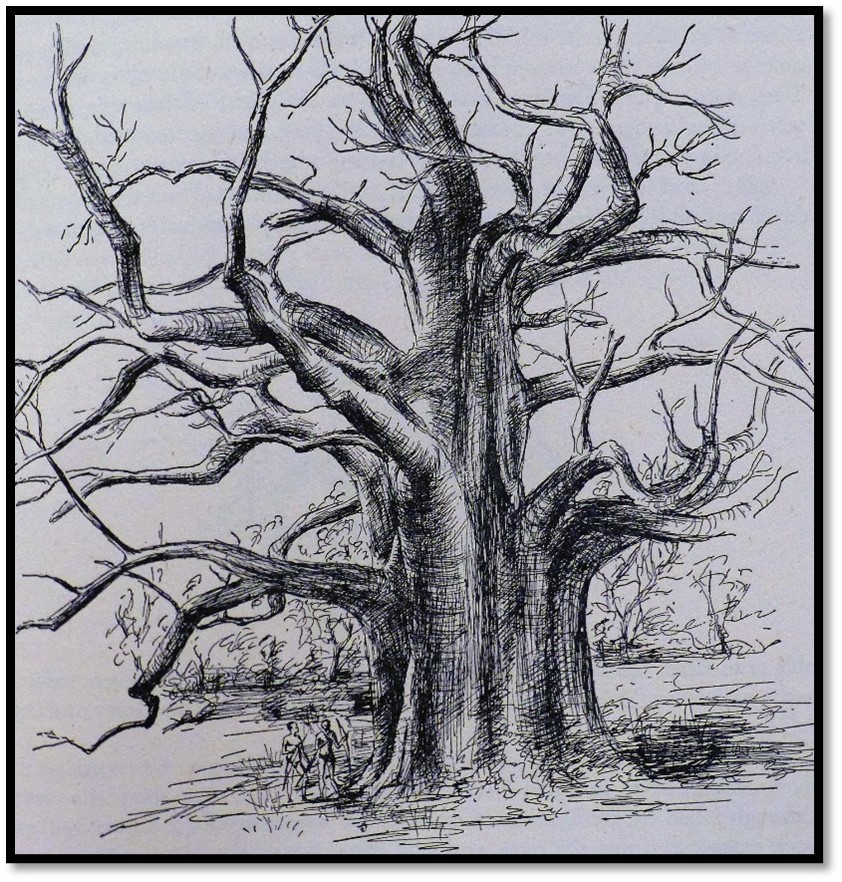

After crossing a drift, we saw a camp under big trees on our left. This was where Dr John Moffat was living. He was the son of Robert Moffat, a missionary at Kuruman and was a brother-in-law of Dr Livingstone, who had married his sister (Mary) Just at this time Moffat was acting as British Resident and had two troopers of the British Bechuanaland Police (BBP) more as a show of authority than an escort. His camp was under what came to be called the Missionary tree; Vaughn-Williams writes that in 1938 when he re-visited, Moffat’s name that he had carved into the tree was still visible!

From here onwards the ground was cleared of bush and we could see the King’s Kraal on high ground to our right, with its huge palisade of poles, glistening white in the distance.[iii] On our left we passed a fairly large native village. A chief met us a little further on and told us we were to camp on a site that he would show us, about 300 yards across the Umgusa River, which was on the far side from the King’s kraal. The bush was fairly thick here, but we could just get a view of the King’s kraal about a mile away. The Induna strongly advised us to build a big thorn bush skerm around our camp to keep the young Matabeles (Majakas) out.

Illustrated by Mary Vaughn-Williams: the wagon outspanned

Where we crossed the river by a drift, there were nice water holes, one of fair size where he said we could get our water. It was known as the Queen’s Water because it was kept for their use. There was a bigger pool further up the river (the Long pool) We quickly set to work and built a huge scherm about 8 foot high, mostly of wag-‘n-bietjie thorn (wait a bit) It was big enough to take our three wagons and all the oxen as well as a bell tent which Arthur had brought up on one of the wagons. A big gate made of poles interlaced with thorn bush closed the entrance. (Edward) Maund had his camp a couple of hundred yards north east of ours.

The Long pool, where Rochfort-Maguire was accused of wizardry was where they all bathed and still existed in 1908 when Mrs Fletcher wrote it was big enough for her boys to build a canvas boat to sail on. A big flood broke it in 1914 and it was never the same again.[iv]

R.A. Fletcher (1910) Map of the area around the King’s Kraal or Umvutcha with the various concession-seekers camps

(Johan) Colenbrander and (George) Condon came over to see us; they had only arrived a few days before. Colenbrander brought a message from the King saying that we were to attend his ‘court’ the next morning and that he (Colenbrander) was to accompany us. He warned us that the position was not too good at present, as the young bloods of the country were all for pushing the white people out of Matabeleland, but Lobengula was holding out against them. He warned us not to go any distance out of camp and never, on any account, to pick up stones. He said that we were certainly going to be watched all the time. He told us there was at least one crocodile in the Queen’s Water and advised us not to swim there. There was plenty of clean, good drinking water.

We settled down and made ourselves as comfortable as possible. On the way up I had netted a hammock and this I slung under one of the waggons for shade. It was fairly cool here and a better place to sleep than on the wagon cartel. That evening after supper, a number of young Matabele girls came to the camp, ostensibly to sell mealies, but really to offer themselves for the night…These maids were very persistent and a nuisance during our stay. Funnily enough, they were worse on Saturday nights. Some old-timers said it was the old missionaries night, which I did not believe. Unmarried girls were allowed the greatest liberty by Lobengula. He said that their bodies belonged to them and they could do what they liked with them, but when married, their bodies belonged to their husbands. Immorality when married was punished by the death of both offending parties. There is no doubt that some of the white men did sleep with these girls.

A story is told of Mrs Colenbrander who came up to stay with her husband a year or so later. When visiting Lobengula she asked him why he allowed his native girls to sleep with white men. His reply was, ‘If I stop these native girls sleeping with the white men and you are the only white woman up here, do you think you could cope with all the white men?” There was no answer to this!

We have an audience with Lobengula; He dines and wines us

The next morning Colenbrander collected us about 11am and we strolled across to the King’s kraal. On the right of the road, about 300 yards away were some huts where the King’s beer, known as tuala (outchualla) was brewed. When ready, it was taken to his kraal in big gourds by young girls, who carried them on their heads. We saw some going towards his kraal. An order of Lobengula's forbade anyone to even look at these maids carrying his beer and men had been severely punished for breaking this law...Beer is made by first sprouting corn or millet, then drying and grinding it. The women ground it between two stones, a flat one at the bottom and a round one above, which they rolled backwards and forwards on the grain until it formed a fine meal. This is then fermented; the coarse part is sieved out and fed to pigs and chickens and the remaining thickish liquid, of a pinky brown colour, forms the beer. It is food and drink to the natives. The taste is slightly acid and is pleasant to drink.

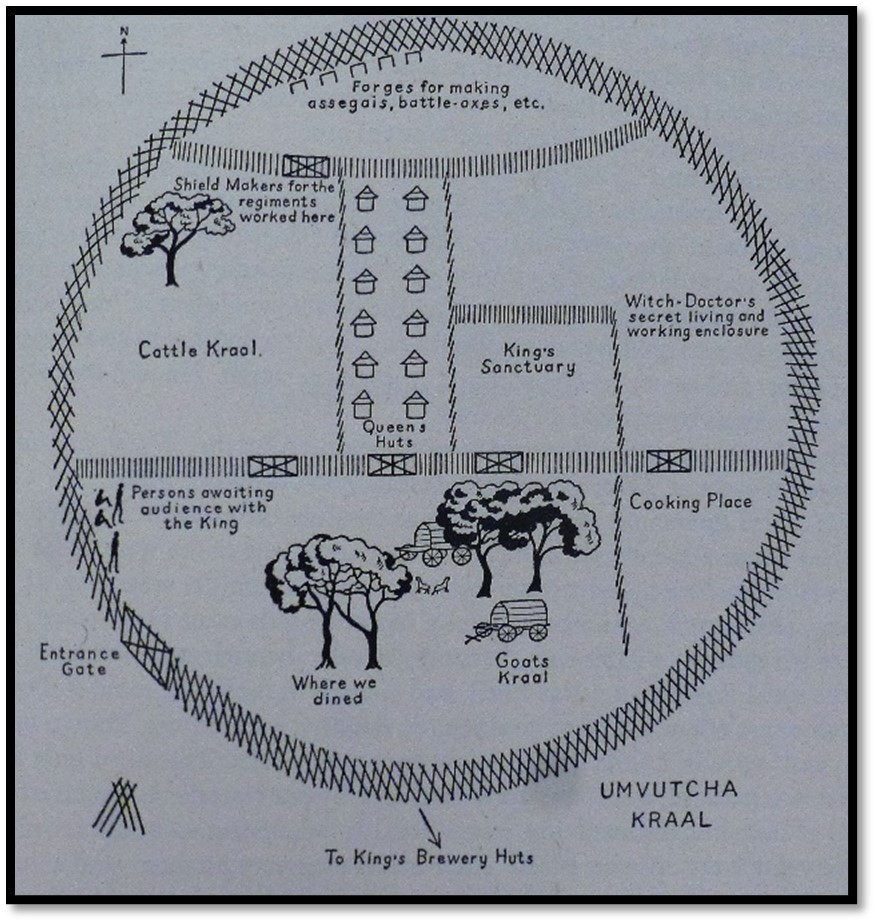

The country round the King’s Kraal was completely cleared of bush to the extent of about two or three square miles, with only a few big trees left. On the east side of the kraal was another village. We were not allowed to visit this village and I never knew the reason, as we could visit the one on the west side. The King’s Kraal itself covered several acres of ground and was two or three hundred yards in diameter. When we reach the kraal, we found its palisade was made of two rows of poles stripped of their bark, about seven or eight feet apart below, leaning inwards to interlace above. The poles were very close together and about eight to ten inches thick and about fifteen feet high. A formidable place to assault. The gate, which was on the west side was equally strongly built and wide enough to admit the King’s ox wagons. Inside the space between the slanting poles, a number of small natives about ten to fourteen years of age were housed. They were known as the King’s ‘black ants’ and were the sons of conquered natives, who were to be trained later as soldiers.

Illustrated by Mary Vaughn-Williams: sketch of The King’s Kraal, or Umvutcha, north of Gubulawayo

The gates were open to us by armed sentries and we were admitted to a big open space, with a few natives sitting on their heels round the perimeter on the left hand side of the gate. Dr Moffat was standing there. In front of us was a tented ox wagon, of full size, under a big shady tree, with Lobengula sitting on a chair next to the disselboom. He was talking to a native as we entered. He had a coloured man in European clothes standing near him. This was a man called Jacob[v] (John Jacobs) who was well known and acted as an interpreter. The King wore the isigodla or kethla (ring) on his head. This occasionally had a blue crane’s feather stuck in it, not a big ring, like some natives. He had a few blue monkey skins round his middle and a bit of cloth rolled up and tied round his chest, knotted at the back. I never found out what the latter was for. He looked about fifty years of age, but I believe he was fifty-six.

This place of audience has been called the Goat’s Kraal, but the floor was sandy and fairly clean. I never saw any evidence of goats there. The only unpleasant sight was a lot of meat hanging on trees near the wagon. The King often had two wagons here.

After he had finished talking to the native, Dr Moffat was called up. He shook hands with Lobengula and had a short talk with him. After he left, two natives who looked like indunas were summoned to the ‘presence.’ They immediately threw themselves on the ground and approached on their stomachs, grovelling and squirming for a distance of about thirty or forty yards, shouting what Colenbrander said were words of praise, such as ‘Oh, Bull Elephant that shakes the ground, Big Black Bull, Lord of Thunder, Stabber of the Skies, etc.’ It was a ludicrous sight and it happened every time a native approached the King. When they got near him he told them to stand up. They had their talk and left, walking backwards, bodies bent and heads bowed, still shouting the King’s praises.

Colenbrander and Arthur were next called up. They had a long talk. When he had finished with them, he beckoned to me. It was only when I got close that I could see what a big man he was. He told me to sit down on a chair, which was supposed to be rather an honour. The first thing he said was, ‘what do you want from me?’ This, I believe, was always his first question to a white man. The coloured man, Jacob interpreted. I replied that I did not want anything. ‘Well,’ he said, with quite a pleasant smile, ‘you are about the only white man who does not want something from me - perhaps you are too young.’

He then asked my age (19 years) and said, ‘Oh, you are a picannin white man’ and he called me that for the rest of my stay in the country. He asked me what I did and I told him I was studying to become a doctor. He was most interested, asking many questions. After a while he asked if I was quite sure I did not want anything. I replied that I had been told there was a herd of elephant about twenty-five miles to the east and would he give me permission to shoot one or two. He said he was sorry he could not let me, as a number of his young men, Majakas, out that way were very aggressive and it would not be safe for me. ‘Anyway,’ he continued, ‘all the big bulls have been shot off, so you could not get much ivory.’ He wanted the young ones to grow up.

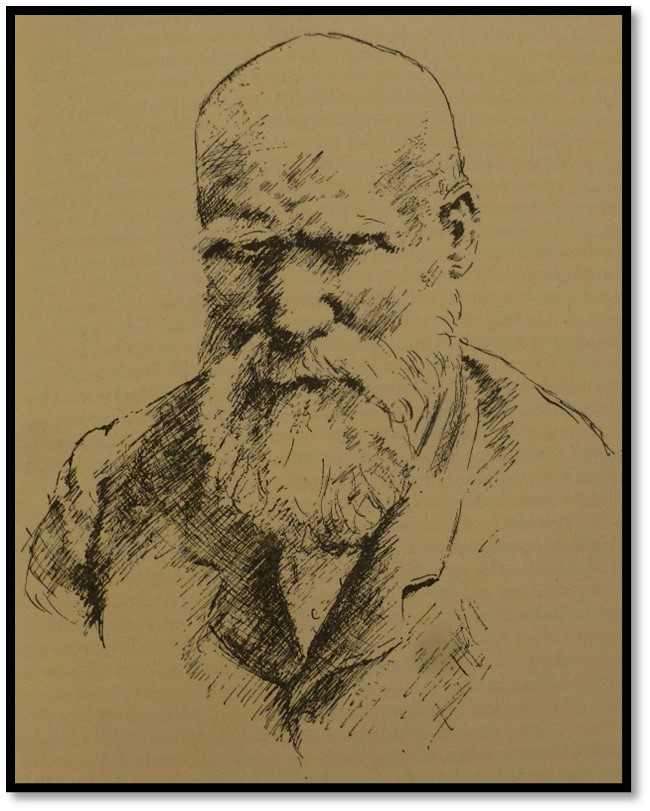

It was about midday by now and Lobengula stood up and said it was dinner time. I then saw what a huge man he was. Over 6 feet 3 inches, I should think and very broad in proportion. He carried himself well and there is no doubt that he looked every inch a King. He carried his head well thrown back and his neck and back were straight. In fact, all the Matabele soldiers had the same carriage, heads thrown back with an arrogant mien, as much to say, ’We are the Lords of this country and you are only interlopers.’

Lobengula always look clean so I suppose he washed. He had a very intelligent expression, rather coarse features, but a pleasing smile. He was stout, but not grossly fat as he was later depicted. He definitely had a commanding and dignified presence and dominated the company he was in. Arthur was only about half an inch shorter, sparely built and broad shouldered. Lobengula looked as if he had been athletic in his youth and I believe he was a very active man. He was accustomed to being obeyed by everyone and showed it.

We could see that the kraal was divided by pole palisades into several compartments with a more or less central one behind the King’s wagon, which was his ‘holy of holies’ and only head indunas were admitted there for conferences.

Lobengula led us to a big tree[vi] a few yards away on the left of the wagon and beckoned Arthur, Colenbrander and some indunas to join us. One of these was Lochwe (Lochi) the King’s chief adviser and a kind of Prime Minister. He was a nice fellow and friendly to white people. He was rather intimate with Matabele Thompson and, I heard later, that this was ultimately his undoing. Mjaan, the King’s commander in chief was there, also a Umshete (Mshete) and Babiane (Babayane) the former as cunning looking and unpleasant as ever, but Babiane seemed pleased to see us. I was told they never dared tell Lobengula what they had seen of England's might. They feared that they might be executed for telling lies. How could they say that any country was more powerful than their Kings![vii]

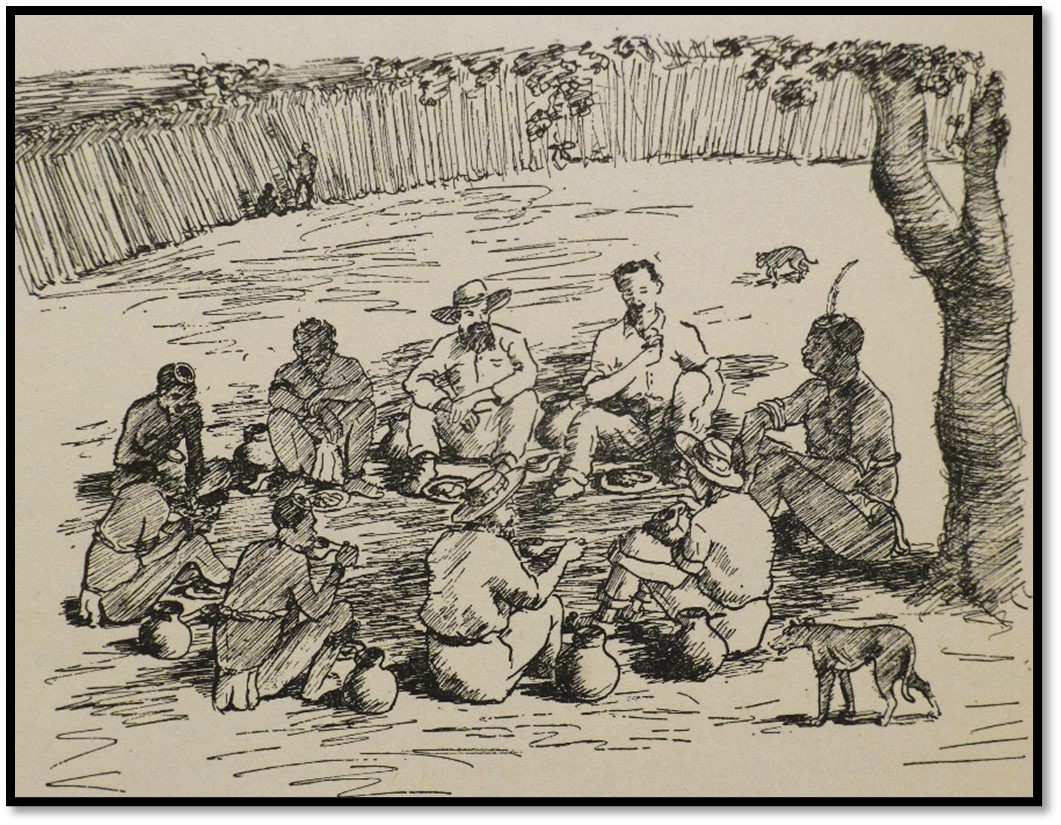

Illustrated by Mary Vaughn-Williams: eating with Lobengula at the King’s Kraal

The King told me to sit on his left, with Colenbrander on my left and Arthur on his right. We just squatted on the sandy ground. He said that I was the youngest white man he had met. I look younger than my age. Enamel plates, piled with slabs of beef, were brought and placed in front of us. I was appalled by the amount on my plate and said to Colenbrander that I could not possibly eat it all. He said I must try, as it was an insult to leave any. He told me to eat what I could and, later on, dogs would come up and I could feed them. This happened, thank heavens and I surreptitiously shoved slabs of beef under my left elbow, which the dogs quickly gobbled up. I hoped the King had not seen me doing it. The beef was deliciously tender and was cooked in big pots. It was hung inside the pots and steamed. I missed salt.

Another trial followed. A bevy of practically naked maids arrived with gourds of beer, one for each of us. The gourds looked as if they held more than a gallon apiece. Each gourd had a little gourd holding about a pint, with a handle and you drank from that. I again asked advice from Colenbrander, as I could not get through more than a pint of the stuff. He said, ‘Wait until after dinner is over and then ask permission of the King to visit his wives. Give them the beer, they will drink it.’

When Lobengula finished his meal. he gave out a huge belch. Colenbrander nudged me and said, ‘If you can do that it is a great compliment to his dinner.’ I failed to comply! I then asked permission to visit his wives who lived in a row of huts running towards the north of the Kraal. There were fifteen wives there. Lobengula was said to have 56 wives, but the others were out working on his lands in different districts. These other wives were also responsible for his cattle and he is said to own more than 150,000 head. Cultivation of the lands was all done with hoes; no ploughs or harrows were used.

Lobengula did not believe in labour saving devices; the more work the less chance of trouble was his idea. All the work on the lands was done by women; the men were only supposed to fight. I never heard of them working except occasionally with oxen. Women, after marriage, were just treated as chattels to work and breed.

The first hut I came to was the favourite wife’s and when I offered her the beer, she said, ‘I want champagne.’ When I said I had none she took the beer. Apparently travellers had often given them champagne. I went from hut to hut until the beer was finished.

When I returned the King took us round part of the kraal. First we went to where cattle were kept on the north west side and here ox hides were being made-up into shields of various colours, mostly for his two guard regiments, the Imbezu and Induba; the first had their shields of black and white and the second of red skins. He presented me with an Imbezu shield, black with a few white spots. They were large shields.

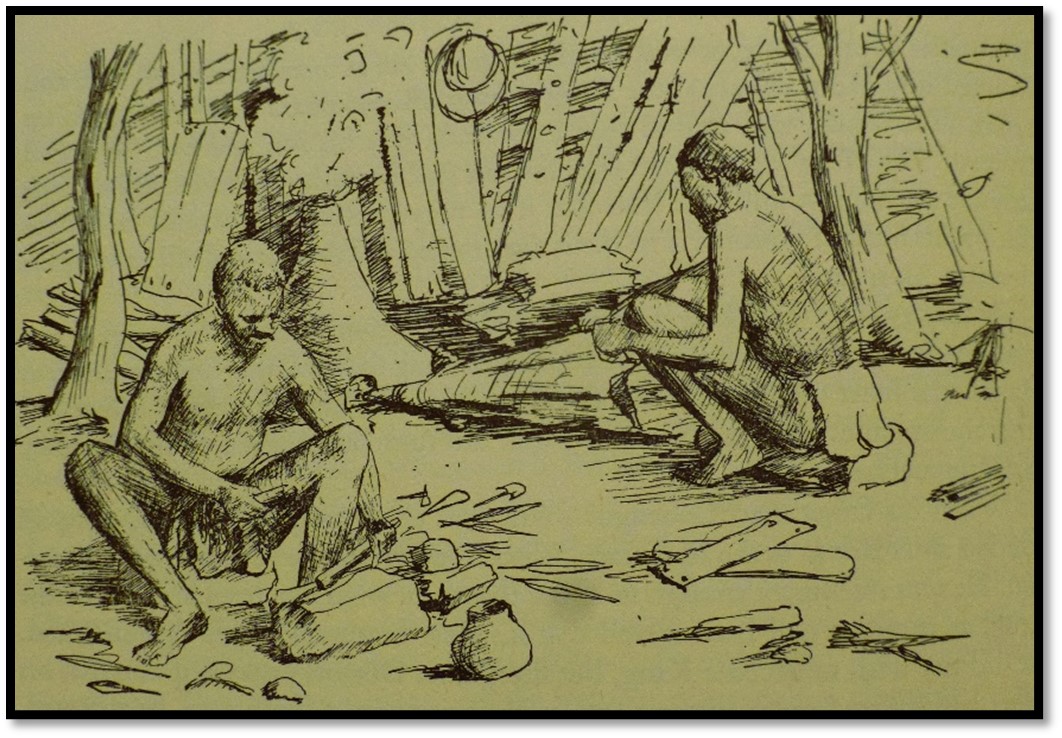

We went through an opening to another part of the kraal on the north side; here were natives working with furnaces and home-made bellows. They were fashioning assegai heads and blades for their fighting axes. I heard that the iron was actually smelted from ore by natives in outside districts. The other part of the kraal was shut off and no one was allowed to enter it. Here the King’s chief witch doctor, known as the Mlimo and his evil looking myrmidons plotted gruesome deeds beyond the imagination of civilised people. Only the King was allowed within this enclosure where he, with the witch doctors,[viii] carried out their rainmaking performances. I could not find out what other dreadful rites took place there. There was another enclosure behind the wagon where the King occasionally held conferences with his head indunas in secret.

Illustrated by Mary Vaughn-Williams: Matabele ironsmiths making assegais and battle-axes

On our return to the Kothla, or place of audience, we had another talk with Lobengula. He warned us that all Matabeles were thieves, that they were trained to be thieves and that the only sin attached to thieving was to be found out! He then gave us full permission to thrash any native we caught stealing, or even coming into our camp without permission. He said they were sure to try. His parting advice, when we shook hands was, ‘Don't look for stones because my young men will fear you are looking for gold and if you find it many white men will come to the country and eat us up.’

We were told not to move our wagons or leave camp for any distance without permission, except to visit the other white men, or the village on the west side. He said this was for our good as he could not trust his young soldiers if we went too far.

That evening, after our return to camp, three young, well set-up Matabele girls arrived, each with a gourd of beer on her head. They were more or less naked, as usual, except for their few beads, and they looked like bronze statues. ‘A present from Lobengula for the Makewas’ (white men) they said. We told them to put down the gourds, thanked them and gave them each two yards of blue calico and told them they could go. ‘Oh no,’ they said. ‘The King says we are to stay with you.’ We were very firm and they cleared off looking rather sulky. It was just as well we sent them off because when we next went to see Lobengula, a few days later and thanked him for the beer, he said, ‘Oh, you didn't like my Matabele girls.’ When we replied that it was not our custom to sleep with native girls, he said he was very glad and had a greater respect for us for not doing so. He said that if all the white people who came up behaved like that, more respect would be shown to them and there would be less trouble.

Unrest amongst the young Matabele warriors against white people: Events leading to the Concession: Rival Expeditions

Lobengula's belief in witchcraft was one of the predominant features of his life. This even caused him to have his favourite sister Minji[ix] killed, as she was accused of bewitching his most recent wife’s child and causing it to be stillborn. He was very good to all the white men who visited him and some of them were pretty hard cases! Some lived at his kraal year in and year out. His young warriors, or madjokas[x] became more and more antagonistic to the white men and begged Lobengula either to kill them all or turn them out of the country. They feared they would come in ever-increasing numbers and take the country away from them.

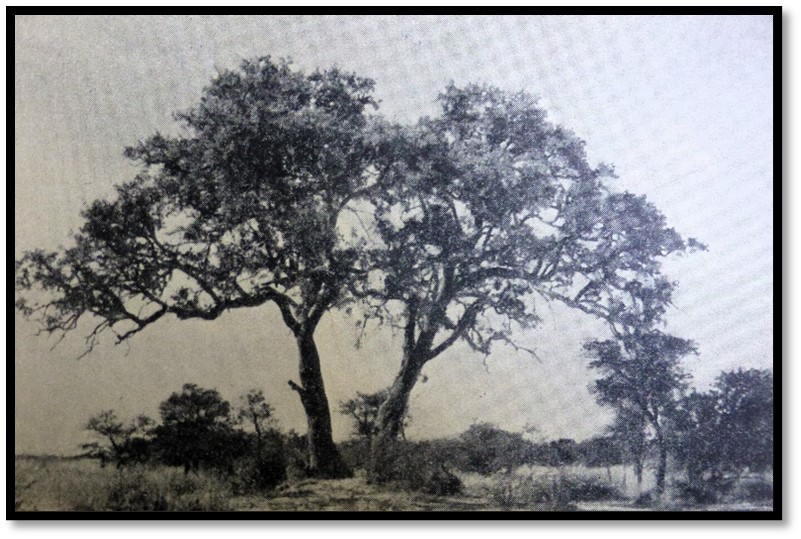

Missionary’s Tree on the old Inyati Road where Alexander Boggie and his companions camped, so-called because Dr John Moffat used to camp under it on their way to the Inyati Mission

John, son of the Revd Robert Moffat of Kuruman, was sent up by the Cape government, then under Rhodes, when he was Assistant Commissioner of Bechuanaland. He actually got Lobengula to put his mark to a Treaty of Peace with England in 1887. Lochwe was Lobengula's chief counsellor and Mjaan his commander-in-chief. A number of white men came into the country, many being concession hunters, but in 1888 Rhodes sent (Charles) Rudd, (James) Rochfort-Maguire and (Frank ‘Matabele’) Thompson, who somehow got the better of Lobengula and obtained a concession to dig for minerals in Mashonaland on payment of 100 golden sovereigns every month, 1,000 (.577/450 Martini-Henry) rifles, 100,000 cartridge and a steamer on the Zambesi. A fact that is generally unknown is that Rhodes never met Lobengula.

At a big indaba chief Lochwe made an impassioned speech in favour of the white people which carried the vote in favour of giving this concession and Rudd left with the agreement at once, Rochford-Maguire[xi] following soon after. Matabele Thompson had to remain behind to ensure regular payments and to represent Rhodes until a Charter had been obtained in England. The concession was ratified in 1889 when I was at the King’s Kraal. The other white traders did their best to cause trouble and create suspicion in the King’s mind and poor Matabele Thompson had a pretty nerve-wracking time; the King even began to doubt England’s power and the existence of Queen Victoria, largely due to Boer propaganda from the Transvaal. The result was that Lobengula was persuaded to send two big chiefs, Umshete (Mshete) and Babiane (Babayane) to England to report on her power.

I always felt sorry for Lobengula. He was a good friend of the white people, even in the most difficult times. No one knew better than he the danger of his young soldiers rising against him if he allowed the white men to come into his country, but he stuck to his agreement made with Rudd, Rochfort-Maguire and Thompson allowing them to develop gold fields in Mashonaland in 1890. It was a very difficult position for him. He only kept his authority by sacrificing his best friend Lochwe. Everyone who had been to see Lobengula that I met was full of praise for his kindness, hospitality and protection.

As I said before, our camp was situated about 300 yards beyond the young Umguza river, which was then fairly thickly wooded. We were allowed to visit the various camps of the other white people; (Edward) Maund, (John Smith) Moffat, James Fairbairn and a few others. There were all together about 18 or 20 in Matabeleland. Fairbairn and (William Filmer) Usher were both very friendly with Lobengula. Some did a bit of trading, but it is hard to say what many of these men were really after up there. I suppose they were mostly adventurers, trying to get what they could out of the King. Some of them drank to excess when they could get cases of whisky sent up to them.

There were a queer lot of white people dotted about in their various camps at the King’s Umvutcha kraal. These campsites were allocated by Lobengula and all were within easy distance of his kraal. Except for men on official business, such as John Moffat[xii] and his two policemen from the BBP (Bechuanaland Border Force) everyone is up there for what they could get out of Lobengula and I regret to say, they resorted to all sorts of underhand means to get the better of each other. Outwardly they were more or less on friendly terms, but they would go to the King and say dreadful things against their competitors for concessions. There were a few traders who more or less kept out of ‘politics.’ I think Fairbairn was one and perhaps Usher.

Rudd, Rochford-Maguire and Thompson, sent up by Rhodes, were the first influential people to arrive. They reached the King’s kraal in September 1888 and it was then that they got their concession signed by Lobengula and witnessed by the Reverend (Charles) Helm[xiii] at the Umvutcha kraal and not at Bulawayo as is commonly stated. This was of a little use to Rhodes unless he got a Charter from the British government to exploit and protect the Mashonaland concession, for none of Matabeleland proper was included in his concession, so Rudd left with the original document and Thompson kept the only other copy.

Maguire was the original of Captain Goode; the character in Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines with the eye-glass and the false teeth. The incident in which Captain Goode frightens the natives by taking out his false teeth to brush them at the river, actually happened to Maguire at Charter Camp.

John Moffat really influenced Lobengula on behalf of Rhodes’ crowd and naturally carried weight as a representative of the Cape government with his uniformed policemen.

Close on the heels of Rhodes expedition came another, sent up by a syndicate financed by (George) Cawston, Lord Gifford[xiv] and I believe Oakley Maund, a stockbroker. This consisted of the latter’s brother E.A. Maund and Condon. Maund, an old NCO in the BBP, had been up to the King’s kraal on official business in 1885, knew Lobengula and was liked by him. This syndicate was known as the Exploring Company and I think the Bechuanaland Company.[xv] They arrived in October 1888 and soon obtained considerable influence over Lobengula.

Another expedition consisting of Renny-Tailyour and Frank Boyle were sent by a syndicate formed by a rich German named (Eduard) Lippert, who held the dynamite concession from Kruger for the Transvaal from which he had made a fortune. They arrived soon after Maund’s party in 1888. Renny-Tailyour became very friendly with Lobengula. He was a nice fellow, but at times a heavy drinker. Colenbrander was with this expedition.[xvi]

(John Cooper) Chadwick (Alexander) Boggie and Benjamin Wilson came up about the same time representing yet another syndicate, so there were all the elements present for trouble. Boggie and his companions were kept virtually as prisoners by Lobengula for two years after the Rudd Concession was signed and every now and then the young warriors (majakas) would come and dance around them, telling them that soon they were going to drink their blood.

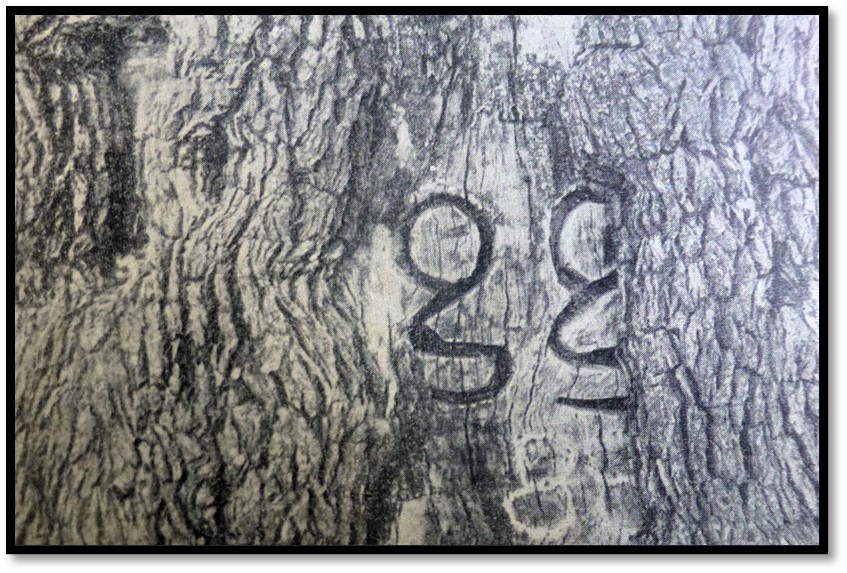

The faint outline of Alexander Boggie’s name and two eight’s of the original date still seen 45 years later

They would run to Lobengula with any stories they could get hold of to belittle their competitors. I often wondered what Lobengula thought of these really unpleasant proceedings. I think, in the end, it decided him to stick to the syndicate with the greater show of authority, but he must have despised the means used by some of them. On the other hand, he probably understood these methods which were so common among the natives themselves.

It was said that when Rhodes heard that Renny-Tailyour, with the German Lippert backing him, had left to try and get a concession from Lobengula, he sent another man up with a wagonload of whisky, with orders not to leave Tailyour's side until the drink and Tailyour were finished, for he knew of his drinking propensities. It certainly was very bad for Tailyour, always a heavy drinker. He died soon after the Matabele War in Bulawayo. This is another example of Rhodes ruthless methods.

Of course Maund and Renny-Tailyour were in opposite camps, but when they found that Rudd had got away with the concession for gold mining in Mashonaland, they both tried to get trading concessions in Matabeleland. They succeeded to some extent, because the syndicate represented by Maund received a very large number of shares in the Chartered Company to buy them out later on.

They put their heads together and thought they would carry more weight in England if they could induce Lobengula to send a couple of high indunas, accompanied by them, to England, ostensibly to refute the rumours spread by the Transvaal Boers that Queen Victoria and England's might were a myth. Maund, Tailyour and Colenbrander persuaded the King to consent to this and it was agreed that Maund, Condon and Colenbrander should take them to England. Two high indunas, Umshete (Mshete) and Babiane (Babayane) were chosen. Tailyour thought that with Maund out the way he would have more influence over Lobengula, but things did not turn out quite as he hoped! Later Maund and his syndicate were absorbed by the Chartered Company!

When Rhodes got word of Maund’s party taking these indunas to England he was said to have done everything in his power to prevent them reaching their destination before his Charter was ratified. It was said that he even booked up all the available accommodation on the ships going to England in order to delay them. However, they managed to reach Madeira in spite of everything. They had heard that Rhodes was trying to delay them. Then, at Madeira, they learnt that Queen Victoria was going off to Aix-les-Bains for a long visit. It was essential for them to get the Queen to receive the indunas at once, or it might be too late for their purpose. Luckily, they found Lady Frederick Cavendish (whose husband Lord Cavendish was brutally murdered in Phoenix Park, Dublin, by Fenians) staying at their hotel and they managed to interest her in the visit of the indunas. She, being a lady-in-waiting to the Queen, cabled her and explained how these indunas had come all that distance to have an audience. The Queen actually delayed her departure to give them time to arrive. She received them graciously and shook hands with the indunas. The visitors were rather lionised and shown a big field day at Aldershot and other impressive spectacles.

There is no doubt that Maund tried hard to upset Rhodes’ Charter but failed and, in the end, Rhodes absorbed their syndicate, although he had to give Cawston's Exploring Company a large parcel of shares.

(Alexander) Boggie and his party did not cut so much ice and also joined up with Rhodes later and received about 20,000 shares in the Chartered Company.

Sir Sidney Shippard was sent up in 1888. He foolishly took a bodyguard of about 16 armed men of the BBP, with Major (Hamilton) Goold-Adams in charge; I suppose to show his authority or importance. This was most upsetting to the young warriors, who considered it a small army. They gave him a deuce of a time on the way up from Tati constantly threatening their camps and doing war dances round them. Some even jumped over the big thorn skerms and threatened Shippard with their assegais. The only thing that saved them was their perfect sang-froid. He and his party were later escorted up to the King’s kraal by an induna. He only stayed a few days, but apparently assured Lobengula that Rhodes’ party was the most trustworthy one and this undoubtedly influenced the King.

On his return he gave much publicity to Moffat's warning that a massacre of the white people was more or less certain in the near future.

This shows how clever Rhodes was to make use of his political influence in every way to get the better of his competitors in Matabeleland in order to further his policy and ambitions.

The Umvutcha kraal site with Mrs R.A. Fletcher and her son P.B. Fletcher standing on the place where the cattle and goat kraals used to be. The Rudd Concession was signed in the goat kraal

The Matabeles: their Customs and fighting forces

Arthur was a very keen chess player and found a boon companion in Dr Moffat and they spent many hours playing together. Dr John Moffat, a full bearded middle-aged man had been appointed Assistant Commissioner to the Bechuanaland Protectorate in 1887 and in 1889 he had been sent up to the King’s Kraal in Matabeleland as British Resident. This was arranged by Rhodes, ostensibly to counteract the influence that the Transvaal Boers were trying to get over the King.

The Boers had been spreading all sorts of malicious rumours against the British and in 1888, as I have already related, had sent up an expedition with one Grobler and another man in charge to try and get Lobengula to sign a treaty with them.[xvii] On their return journey they came to an unlucky end, both being killed near the Limpopo in an affray with Khama’s men, with whom they had fallen foul. Moffat came up with a certain show of authority, being accompanied by two troopers of the British Bechuanaland Police. There is no doubt that he was a strong influence in getting Lobengula to see that the Rhodes Concessionaires were the most reliable of all the parties who came up there and was certainly instrumental in helping them to get the concession.

Although allowed to go visiting we were virtually prisoners and could not leave the camp for a couple of hundred yards without being followed by young Matabeles, dodging behind trees and spying on us. This, even when you were on the most private business, which was sometimes very awkward!

Quite a number of native's visited our camp, indunas and others of lesser rank, either to spy out the land or to get something out of us. Gambo, a young induna and a son-in-law of Lobengula was a rather nice type of native and was very friendly with Arthur, who used to get information out of him…

…We frequently walked through the village on the way to Dr Moffat's camp about a mile away. I spent some time looking at the huts and the natives, mostly women and small children, with a few men here and there. The huts were clean and neatly built. The married women wore a leather skirt reaching to the knees, made of beautifully brayed skins worked up into fringes all over. The girls only wore their scanty beads.

While we were there the small black bead was very fashionable, but blue and white were also used. Nobody was allowed to wear the large blue bead, rather light in colour, as the Queens had declared a monopoly on them for their own use. This was rather bad luck for us, for we had quite a number and they were now useless for trade, so we gave the Queens quite a lot of our stock…

…Marriage in Matabeleland was quite an event, with its peculiar customs. No love seemed to enter into it; in fact, love, kindness of heart and gratitude appeared to be unknown to the Matabele character. Such qualities were looked upon as a sign of weakness by these savage people. A young man when he got permission to marry from the King was not allowed to choose a wife whose father was related to the bridegroom or had the same tribal name; he generally had to go to some neighbouring village. Before his visit an ox was killed and meat was taken to the girl’s father’s kraal. He would be accompanied by friends and, on arrival, there would be a pretence of driving the visitors away. A mock battle then took place. After this they would make friends and they would be feasting and dancing for a couple of days; they then repaired to the future bridegroom’s kraal, the prospective bride being accompanied by her girlfriends. Here there was more feasting and entertaining; then came the marriage ceremony. The girl came up to her future husband with a gourd of water on her head. Strings of beads lay at the bottom of the gourd. After sprinkling water on the bridegroom and her girlfriends, she would put the gourd on the ground, place the beads on her head and smashed the gourd with her feet. The ceremony was then complete and they were married.

No Matabele husband was allowed to look on the face of his mother-in-law. Neither was the bride allowed to look on the face of her father-in-law. Some white people would not object to this law! A woman could not divorce her husband, but the man could divorce his wife. Twins were always killed at birth, as they were supposed to be to “tagati” (bewitched) Infant mortality was very high.

None of the natives owned land individually in Matabeleland, but they could own cattle, sheep and goats. Some were rich with their stock, but if the head of a kraal or an induna became too rich, he was very liable to be accused of witchcraft, when he would be ‘smelt out,’ killed and all his possessions confiscated. This was quite a common occurrence. The King had enormous numbers of cattle and many of them were farmed out at different kraals, the inhabitants of which were allowed to use the milk only. The milk was mostly saved for the boys and young men. To make them grow big and strong…

There were supposed to be at least 25,000 soldiers when I was there. The men, from boyhood, got the best of everything and the result was a very fine nation physically. They were big, well set-up and carried themselves remarkably well. People are now inclined to say that the physique of the Matabele soldiers had deteriorated through their intermarrying with different tribes. This is not true. They were a magnificent body of men. During the Matabele War (of 1893) the best of them were killed off and in that way deterioration came about.

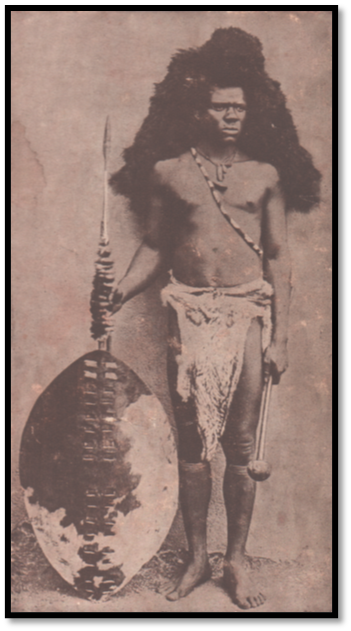

The two outstanding features of Matabele life were soldiering and witchcraft, both of the most bloodthirsty kind. Soldiering with its rigid discipline, raiding, fighting and massacring were as life’s blood to the young Matabeles, trained to cruelty. All boys from 15 years upwards were put into regiments and trained. The regiments varied from about 600 to 900 strong; they were centred on different big kraals, where they were commanded by the indunas of those kraals and generally called by the name of the kraal. Some regiments consisted almost entirely of young married men, ‘majakas’ with a sprinkling of older men. These regiments were about 900 strong. Other regiments, called ‘Amadoda’ consisted of veterans, with kechlas or head-rings and a few young men. They were frequently 500 or 600 strong. The regiments were known by distinctive head-dresses and the colour of their shields. Their chief weapon was always the short, broad-bladed stabbing assegai, but many carried the light, throwing assegai as well. Some had small battle-axes, made of sharpened triangular pieces of iron, let into the heavy head of a knobkerrie.

Image from Gold from the Quartz of an amaNdebele Majaka (soldier) in full military dress

In their full dress, at dances, they were a magnificent sight, especially the young soldiers, who wore a kind of helmet of black ostrich feather plumes coming well down over the forehead and covering a part of the neck at the back. Sometimes they had a cape of similar feathers. These were most impressive when they waved in the wind during their dances. Tasselled armlets of ox tails and long-haired goat-skin bands below the knees were also worn. The ‘Amadoda’ or veteran regiments, wore bands of otter or leopard skins round their foreheads below their rings or kechlas, frequently having blue crane feathers stuck into the latter.

Before the big dances, which were the equivalent of reviews in civilised countries, all soldiers had to wash and be ‘treated’ by the witch doctors, before entering the King's presence. Regiments were accompanied to these dances by many of their womenfolk and often travelled long distances from their kraals. Before the main war dance, these women would dance in front of their regiments, singing loudly, but when the regiments danced and advanced towards the King the women disappeared behind them. All shouted ‘Kumalo’ at the top of their voices - the royal salute - and if I remember rightly, the King’s tribal name. At the big dances held every February the Queens, sometimes to the number of 50, would parade in front of the regiments, many of them wearing a kind of crown of bright blue Jay feathers. This, with the gay shawls they wore gave them quite a picturesque appearance. They sometimes danced, which was rather grotesque when one remembers how fat some of them were!

The regiments, after dancing, would charge up towards the King and his indunas, rattling their shields and making a noise like thunder, shouting and pointing their assegais. The King would throw a spear in the direction of the next raid and then, after the dance was over, a number of oxen were sent on to the ground, killed with assegais and a great feast took place, with quantities of beer.

Witchcraft: its dreadful hold on the Nation

Witchcraft was a predominant feature of the lives of the Matabele; it was a curse and a scourge. If anything went wrong it could only be due to witchcraft and the whole population believed firmly in it. There is no such thing, in their belief, as a good spirit; there were only evil spirits. Such a thing as death from natural causes was not considered possible; it was due to witchcraft and the culprit or culprits who caused it had to be ‘smelt out’ by the witch doctors and executed forthwith…

Long droughts were ‘of course’ caused by witchcraft and 1889 was one of the worst years of drought on record. Crops failed and many victims were ‘smelt out’ and killed; hundreds of them. Whilst I was at the King’s kraal, it was estimated that at least eighty were killed in the village to the north east of the kraal. Judging by the ghastly noises, yells and beating of drums we heard at night, I should have thought there were more. I rarely heard those noises from the other villages on the west. No white man was allowed anywhere near these dreadful ceremonies; it would have been as much as his life was worth to venture there. All these gruesome affairs were taken as a matter of course by the natives, who appeared the next day as if nothing had happened. I think our own native boys were scared stiff and there was no difficulty in keeping them in the camp at night.

The universal belief in witchcraft was made full use of by Lobengula in holding absolute sway over his people. If an induna offended him or even became too rich and powerful, he would be accused of witchcraft and his kraal ‘wiped out’ only the young girls being kept for wives; sometimes not even they were saved. Some years, literally hundreds were killed off in this way…

During our stay at the King’s Kraal several deputations from outside kraals, consisting of one or more regiments, would come and dance before the King and ask him to ‘make rain’ but he wisely refused on various pretexts. It was a real year of drought and many blamed the Makewas, or whites for it.

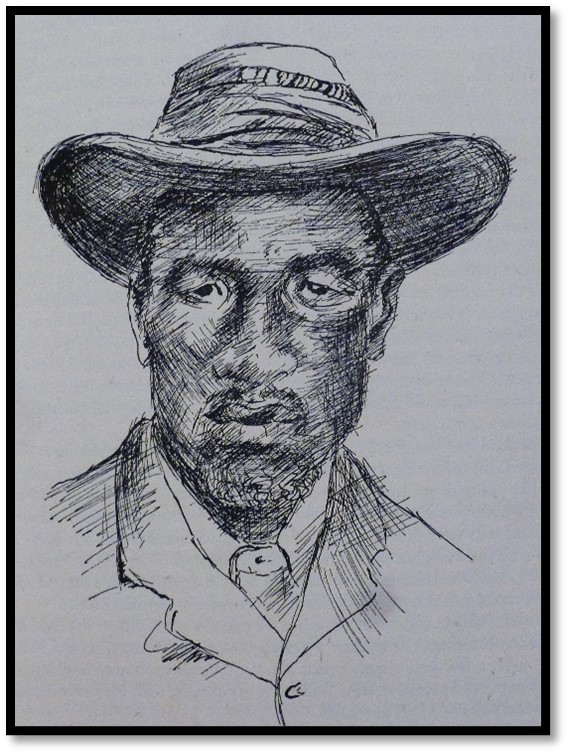

Arthur was very anxious to take a photograph of Lobengula, but we knew that it was not possible to get his consent. Others had tried and been told it was ‘tagati’ they being made to take their little black boxes far away or be punished; that is why no photograph of Lobengula is to be found today. There is no real authentic sketch of him, for if a sketch or portrait had been made some enemy might ‘stick pins’ into it and so cause his death. Anything out of the common was suspected and treated as witchcraft. When Rochford-Maguire went down to wash and clean his false teeth at the (Long) pool, he took his toothbrush and pink toothpaste with him. Of course there were young Matabeles watching him from the bush. There was a deuce of a row and they dashed down and took away all his shaving material, false teeth, even his eyeglass; accusing him of bewitching the water and turning it pink; taking his teeth out was certainly witchcraft. When the matter had been explained to Lobengula, Maguire's property was returned to him. Rider Haggard made use of this story later in his book King Solomon's Mines.

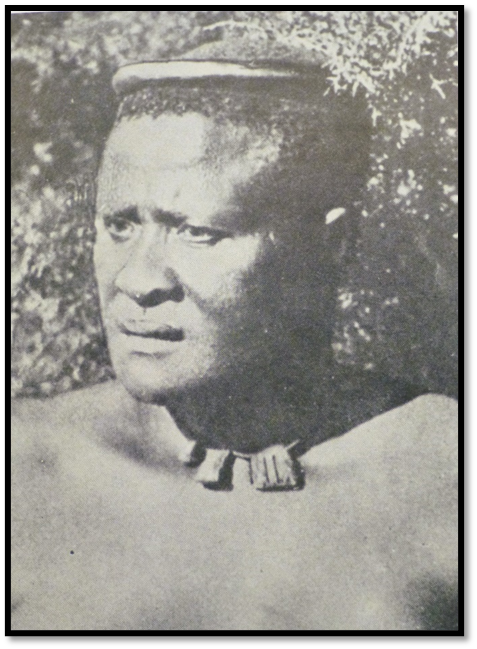

Source unknown, believed to be an image of Lobengula, King of the amaNdebele

The crocodile was very much ‘tagati’ and anyone even holding a piece of a dead crocodile was apt to be bewitched. While I was at the kraal a big crocodile was seen in the Queen’s Pool and Lobengula asked to have it shot for him. One of the BBP, a dead shot was told off to do the job. He waited on the bank and when the crocodile came out he shot it through the eye with a 450 Martini-Henry. It sank in fairly shallow water - dead. The difficulty was to get it out without anyone touching it. Lobengula was informed of the event and sent several witch doctors with one of his wagons to collect it. They put a rope of reims round the crocodile, pulled it out and lifted it on to the wagon, as far as I could see, without touching it. Off they went to the King’s Kraal. Drops of blood that fell on the road were carefully shovelled up by one of the witch doctors, who dug his hands well into the sand so as not to touch the blood. This was placed on the wagon as well. It would have been most dangerous to leave the blood for fear someone else would collect it. This crocodile was, of course, used for rainmaking purposes…

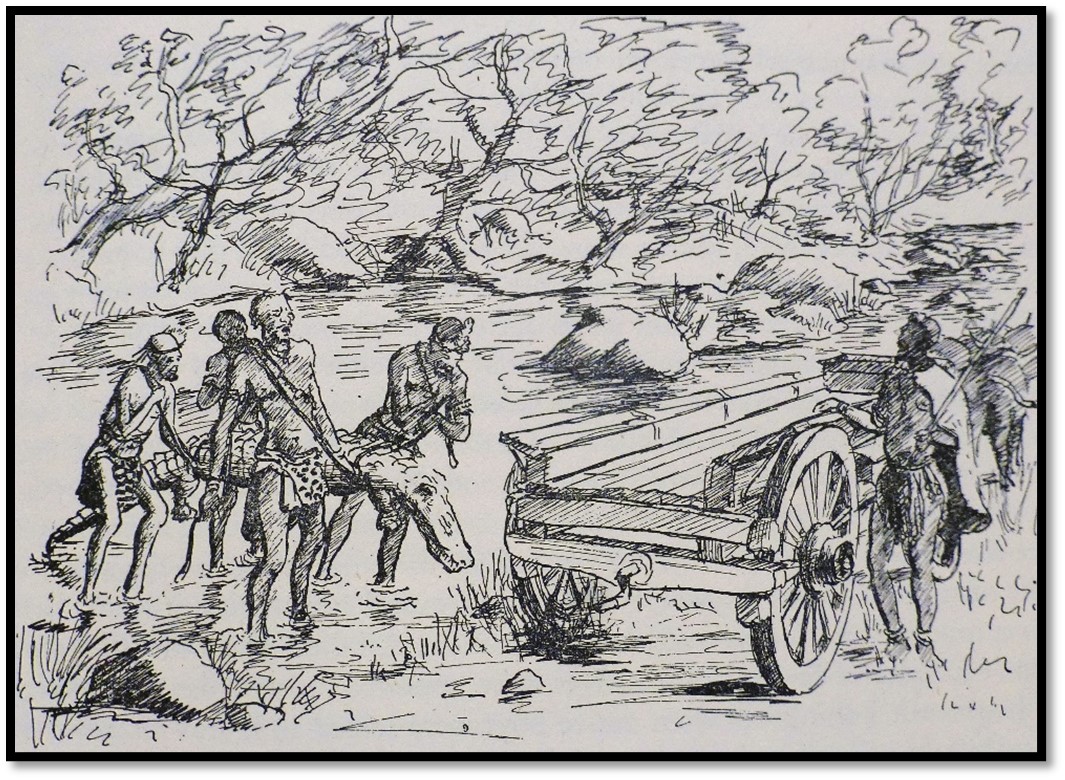

Illustrated by Mary Vaughn-Williams: crocodile being taken from the Queen’s Pool

I make a fast trip to the Victoria Falls and back with McMaster

(Thomas) McMaster,[xviii] who had come up with us, had been away on a short trading trip with Lobengula's permission. On his return he said he was going to ask for leave to go to the Victoria Falls and would any of us like to go with him? Arthur said he could not possibly go, but that I could if I wanted to. I jumped at the offer and we got permission from Lobengula, provided we did the trip within a month, reckoning by the moon.

We left a couple of days later in McMaster’s light waggon and 12 fast oxen. Lobengula provided a young induna to accompany and help us. My brother warned us, before starting, to avoid any trouble with the natives, who were sure to be cheeky and truculent and reminded us of the story of the officer and a civil servant from Natal who had been allowed to go to the Falls a couple of years before. They had fallen foul of the natives and had been killed.[xix] They were accompanied, I believe, by one of the Revd Thomas Morgan Thomas’s sons who was also killed. Thomas was a missionary up there.[xx]

We trekked very fast, at first over rocky stony ground and later through thick bush and big forest country, wonderful big trees of various kinds. The mahogany trees were very beautiful. (possibly the Umguza and Gwaai Forest Lands around Sawmills) They were many other forest trees, unknown to us. We kept to the west of the Gwaai (Gwayi) river. This part of the country is now a game sanctuary (Hwange National Park) I have rarely seen such big flocks of guinea fowl and when we were near any villages we found hundreds of them at a time. Partridges and bush pheasants were also plentiful. We travelled very fast and sometimes made long distances in order to get to water. Much of the road later on was sandy, a very fine sand that got into everything. We sat on the front of the wagon most of the way and saw heaps of game. There were lions round our scherm at night. Elephants inhabited these parts but we never caught sight of one.

We crossed a couple of rivers, the last being the Matetsi and reached the Falls in ten days, about 200 miles: good going, even with a light empty wagon. There was a native village near the Falls and the chief tried to make himself unpleasant, but we gave him presents of cloth, beads and lead and the young Matabele induna we had brought with us explained that we came from Lobengula’s kraal with the King's consent and we were troubled no more.

We could see the fine spray or mist from the Falls several miles away. It looked like a small cloud and might easily have been white sand dust. As we got nearer, we heard the indescribable booming sound of the Falls. The bush was very thick here. After we had outspanned we walked a short distance to get a closer view, but we had the greatest difficulty in getting near the edge of the deep chasm; we literally had to push our way through the bush in order to see the Falls at all. We tried several places and got different views, but it was not possible to get as complete a view as one now can. It was only when we went to the east side that we could get any idea of the extent of the Falls and the huge volume of water. I can well understand how Livingstone made such mistakes in his calculations of the size of the Falls. They were an awe-inspiring sight and we spent many hours gazing at them, one of the world's greatest wonders.

We saw big herds of buffalo in the bush, many tsessebe and other game. Parts of the bush were too wet to stay in there; they are now known as ‘the rainforest’ due to the spray. We did not stay long as our provisions were getting low and not wishing to depend on meat and birds entirely, left after a couple of days and were back at our camp in well under the month. It was the fastest trek by oxen I have ever done and we were tired out when we got back.

I thought that I was the youngest white man to visit the Victoria Falls; I found out later that a distant cousin of ours, Ralph Williams, at that time, British Resident in Pretoria, had trekked up in a Scotch cart via Tati with his wife and their small son the previous year. They had gone north west direct to the Falls, without going to Gubulawayo at all.

Native unrest growing, big indaba ends in sacrifice of Lochwe: Matabele Thompson bolts. Probably the first game of tennis is played in Matabeleland

On our return we heard that there were grave rumours of unrest among the young Matabeles and some of the indunas. They were more strongly opposed than ever to the white man. The drought was also upsetting them.

We saw numerous deputations going to Lobengula’s kraal; some was sent to beg him to kill off the whites, others to implore him to ‘make rain.’ One big deputation consisted of two regiments and we were allowed by Lobengula to see them perform a dance. We stood with some indunas outside the King’s Kraal and the regiments, with their women singing, danced in the big open space. It was a wonderful sight. The men were all about the same height with perfect physique and upright carriage. Their ostrich feather headdresses and capes made them look even bigger and broader; they were a magnificent sight. They made a terrific noise, beating their shields with their brightly polished assegais and all stamped on the ground at the same time until one could feel it shake. Some of the regiments wore anklets of dried fruit pods, with big seeds inside, and the rattling sound added to the din. When they charged up, pointing their stabbing assegais polished like silver and shouting “Shia, Shia, Shia” (strike) I thought our end had really come. I think Lobengula was also a bit doubtful of their intentions, for he came hurrying out of his kraal and waved them away. I was not sorry when we were safely back in our camp. There was a fearful din that night from the two villages, for drums were continually beating. We could only guess what was happening!

Apart from the excitement of living amongst these natives, there was little to do in camp but read and play cards. Cribbage was a great game on trek. Often as not there were only two people, so that it was one of the few games that could be played and it did not require a great deal of skill. Most of the wagon travellers of those days played the game and carried cribbage boards and cards; it made a lot of time pass pleasantly.

Tennis was rather in its infancy in 1889. Arthur, who had become keen on the game in England had brought out some tennis rackets and balls; these were packed away in one of the big cases. It was only after a few weeks that we remembered they were there and got them out. The bush was cleared for an area large enough for a court and Arthur had a surface of broken-up and powdered antheap, mixed with fresh ox dung, laid down on the sandy soil; it was carefully smeared over the top about 2 inches thick and made as level as possible. This hardened and resulted in quite a good even surface. We had no net, but we put up poles and slung a length of cord across the height of a net. On this we hung a piece of white cloth, about 6 inches wide to act as a net. It worked quite well, but one had to be careful to watch that the ball did not go under when you thought it was over.

Arthur and I played a singles match and I won it. I have often wondered since that day whether I won the first set of tennis ever played in Matabeleland. I never heard of any other tennis there at that time; it must have been fairly early in September 1889. Colenbrander, Condon and Beaumont came over and had a few games, but it was a nuisance hunting for balls in the bush.

As far as we were concerned I saw no evidence of Lobengula's savage nature when we visited him, which we did seven or eight times during our stay, but there is no doubt that he was the cause of innumerable killings and massacres and was often guilty of the most wanton cruelty in his punishments.

We were unlucky to strike this very dry season. The heat became very great, damaging crops; it was so hot sometimes that as I lay in my hammock in the afternoon under the wagon the perspiration literally poured off me onto the ground. This drought was the cause of much activity among the witch doctors who were trying to find victims for sacrifice. On the slightest provocation they would ‘smell out’ some poor native in his village and have him killed on the spot…

About the middle of September we could see that the King’s Kraal was showing signs of great activity. Indunas with quite large followings were coming and going, after holding long indabas and we heard from certain friendly indunas that this unrest was due to the leading indunas and the army being strongly opposed to the Rudd Concession. There was a grave danger of an uprising against the white people and even against Lobengula, unless they were convinced that the land was not going to be taken away. It should be remembered that the army was at least 25,000 strong, probably much more and although they were loyal to Lobengula, it did not take much in their country to start a big killing! They were convinced that Lobengula had been influenced by his chief adviser, Lochwe, to sign away their country to the white people. He was known to be very friendly with Matabele Thompson and they all knew that Thompson was there to represent Rhodes Concession.

Matabele Thompson had had an extremely trying time since the Concession was signed about 15 months earlier and he was getting more and more nervy. One could see by his manner that he was thoroughly scared and I was not surprised. He had been all alone since Rochford-Maguire had gone, for Rudd had left quite early. Two months were quite enough to make me feel a bit scared and he had had nearly 15 months of it. Thompson did not appear to be friendly with any other white man; he was a queer fellow and he seemed to suspect everyone. He knew that, as Rhodes representative, he was one of the chief objects of suspicion with the Matabele, but he thought that Lochwe and Lobengula had sufficient influence to protect him.

Thompson received the money (£100 per month was supposed to arrive) and the rifles regularly sent up for Lobengula by Rhodes. Lobengula refused to take delivery of the rifles for some reason which I did not know and it was said that they were packed away in Thompson's camp. He was also credited with holding the only copy of the concession, which, he stated later he buried in a pumpkin gourd for safety.

I doubt if the rifles would have been much use to the Matabeles. I occasionally saw a native with an old gun and if you could induce him to fire - and it took some doing - he would shut his eyes, pull the trigger and be quite prepared to run. They had no idea of taking aim.[xxi]

There is no doubt that we were all in great danger, but we did not realise it until later. The outcome of all this unrest was a big indaba, held in the middle of September when most of the head indunas were assembled. No white man was allowed near the King’s Kraal. Matabele Thompson was away visiting the Helm’s at Hope Fountain, some 12 miles from Gubulawayo. Although his daughter says in the book of his reminiscences, which she published that he was present, he was not. We heard through Colenbrander that the whole question was being thrashed out; each induna had his say about the white people.

Meanwhile messages had been sent out to our different camps telling us on no account to go outside our scherms until given permission by Lobengula. As we heard later, things were getting pretty lively at the indaba; several indunas got up and said that they would lose their country if more white people were allowed to enter. Some were all for killing off the whites. They got very heated and angry and blamed Lochwe for his friendliness to Thompson and the whites, and, as he was Lobengula’s right hand man and adviser, the latter was also indirectly being blamed. Lochwe spoke out strongly to save the white people and said that there was no danger of their entering Matabele itself and that Mashonaland was their object; they only wanted to go and dig for gold. He said that if they were prevented from going into Mashonaland war might be the result.

NHM No 60: Thomas Baines watercolour of 15 November 1870 - Lobengula reviewing his army after a successful raid

Lobengula very wisely, said nothing, but he saw that things were going badly for Lochwe and that, as a result, he himself was being made responsible. After very heated discussions, and veiled threats, Lobengula cunningly suggested to the gathering that he and certain influential indunas should retire to his sanctum behind his wagon and discuss what was best to be done. Lochwe was not invited. At the secret indaba it was shamefully decided, I believe at Lobengula’s suggestion, to sacrifice poor Lochwe as a means of appeasing the young warriors and their indunas. In this way, Lobengula saved his popularity.

The counsellors returned to the indaba and gave their judgement, which was received with great acclamation; we could hear the shouting from our camp late that afternoon. Lochwe, friend and adviser to the King was informed that he was to be killed. He was told that he could run for his life from the kraal. This the brave old man refused to do and walked in a dignified way through the gates. There he was set upon by the hordes of ‘black ants’ as the youngsters who lived in the palisades were called. They did him to death with their knobkerries; a shameful performance. Colenbrander had a complete description of the whole affair from one of the big indunas who was present.

There were other versions of Lochwe’s death given later by people who were nowhere near, such as that another induna had stabbed him; others said that he was strangled; but I am sure that our information was authentic.

Now Lochwe was a very influential induna and was in command of a regiment at his kraal, which was a big one, some 30 miles away. Lobengula gave orders that afternoon that this kraal was to be ‘wiped out’ and it was. Men, women and children (to the number of about 300) dogs, pigs and fowls; every living things. Nothing was left alive and the kraal was burnt. Thus ended Lobengula’s friendship for his most intelligent and loyal induna! There was great rejoicing, feasting and noise at the kraal and villagers that evening and we wondered what had happened; we did not hear for a day or two, for nobody came near us. The killing of Lochwe did not mean that we were safe, but there is no doubt that Lobengula protected us somehow or other.

Matabele Thompson, as I said before, was away visiting the missionary Helm at Hope Fountain; he was driving a Cape cart and four horses. On his way back next morning he met a native woman, whom he knew well, halfway between the Helms and Gubulawayo. She stopped him and told him that all his friends had been massacred. Whether he misunderstood her, or she deliberately told him wrongly, I do not know, but he understood her to mean that all the white people had been killed.

He drove onto Dawson’s store at Gubulawayo, where he borrowed a saddle and bridle, leaving the cart and three horses with Dawson to look after. He saddled one of the leaders and rode off. He said nothing to Dawson of what he had heard, nor did he try to find out if it was true. Dawson told me this when I passed his place a few weeks later. Thompson just cleared off south at the gallop, leaving all his possessions behind.

He was scared to death. He did not stop riding until he was beyond the Ramaquaban when his horse became completely done up, for he had gone about 100 miles. He reached there that night and of all the foolish things he could do, actually tied his horse to a tree in a country full of lions, giving the poor animal no chance to escape. The horse could get neither food nor water. As a matter of fact, it was found the next day, alive, when Sam Edwards sent for it. Thompson never stopped until he reached Tati the next morning, walking through the night for 20 miles. At Tati he found Major Sam Edwards and told him his story. Edwards laughed at him and said that he would have heard if any such massacre had taken place; he advised Thompson to return to avoid trouble with Lobengula. Thompson was so sure that we had all been killed, that nothing would stop him or induce him to return. He would not wait. He borrowed a Cape cart and four mules and drove off through the Kalahari by the fairly well-marked wagon track, until he reached Mafeking a few days later. From there he sent messages to Kimberley saying that we had all been killed. He then went on to give the names of all the white people and I heard later that our names were published in the Kimberley Advertiser as having been massacred.

Illustrated by Mary Vaughn-Williams: Matabele Thompson’s Cape cart and mules

Meanwhile, up at the King’s Kraal, the position had become tense. When Lobengula heard that Thompson had run away, he was furious. “It shows he does not trust me,” he said. He then had a letter written, addressed to Rhodes or his representative, saying that if Thompson did not return immediately, he would cancel the Concession. He was very angry and sent this letter off immediately by Matabele runners. The letter was carried in a cleft stick as usual. I do not know whether the runners had any relays, but the letter was delivered soon after Thompson’s arrival in Mafeking, a wonderful piece of work. This was an anxious time for us. Lobengula would not see any of us except Colenbrander who told us that Thompson’s running away placed us in a very precarious position. The white people at the kraal were all furious with Thompson; I do not think they ever forgave him. It might have put the King against us and have endangered all our lives because of the inflamed tempers of the young warriors. What was said about Thompson would hardly bear repeating!!

Native bravery, no hope of a Concession: I get permission to leave the King’s Kraal with a Hottentot wagon; we reach Ramaquaban

Gambo the King’s son-in-law, who is a nice type of native, lighter in colour than most of them, visited us and gave us a certain amount of news. He was rather an admirer of Arthur’s who interested him by feats of strength and other tricks. The other natives shunned us and if we saw any they gave us very black looks. There was no sign of rain and October was unbearably hot; being allowed to bathe in the Queens Pool was something to be thankful for.

There are many stories told of the Matabele’s bravery and disregard of death. As an instance of this it is related that when Livingstone[xxii] or Moffat, visited Mzilikazi, Lobengula’s father, he preached a sermon on God and the horrors of hell fires. Mzilikazi called a number of young soldiers, made them build a huge fire of logs and, when it was burning fiercely, ordered them to stamp it out with their feet, which they did. He turned to the preacher and said, “There, that is what my men would do to your hell fires.”

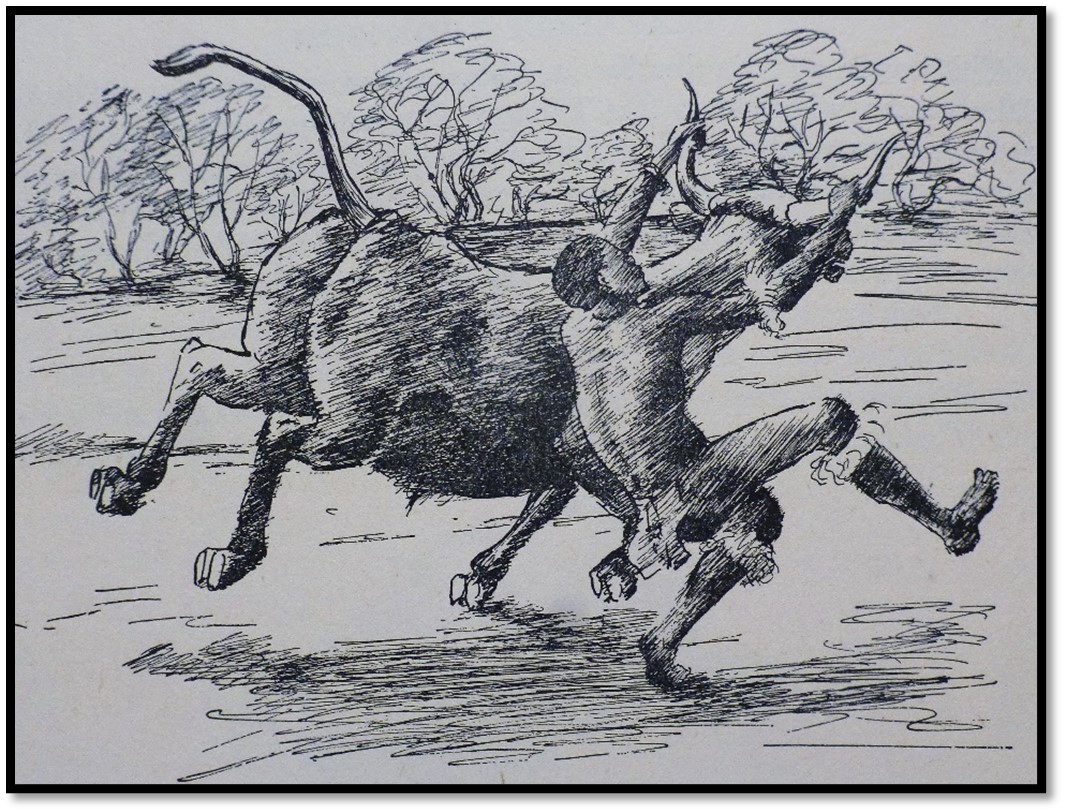

A remarkable performance, which I myself saw, took place after a native dance, when a young ox, about 2½ years old, weighing roughly 600 pounds and very wild, was let loose on the parade ground. Three or four young warriors were sent after it. One of them jumped in front of the ox, caught it by its two big horns, twisted its neck and, throwing himself on the ground, brought it down with him. I saw this several times and once or twice the ox's neck was broken. It took some doing and was as good as any rodeo show in America.

Lobengula would occasionally send out small parties of warriors to kill lions. This they would accomplish using only this stabbing and throwing assegais; a brave feet, as anyone with a knowledge of lions will agree. Lobengula had several rather moth-eaten lion skins obtained in this manner hung up inside his wagon.

Illustrated by Mary Vaughn-Williams: amaNdebele majakas overturning oxen

It was now evident that Arthur was not going to get a concession and he had made-up his mind that as soon as he was released, he and Balane would trek back to Tati and go up the old Hunter’s Road[xxiii] past Tuli through Mashonaland in search of a road through Macequece (Massi Kessi – now present-day Manica) in Portuguese East Africa to the coast at Beira in Mozambique; this he would do for the (Royal) Geographical Society. He said that before he left he would probably stay at the King’s Kraal for two or three months to see what was happening.

One day I met the two BBP troopers at the Queen’s Pool, when I was bathing. They told me they had got permission from Lobengula to leave the country; there was a family of Hottentot’s[xxiv] going out with their wagon in a few days’ time. As it had never been my attention to go to Beira and I could do no good where I was, I made up my mind to go with them. They said they would arrange with the Hottentot’s to take me. I went back to camp and told Arthur. He thought it an excellent idea that I should jump at the chance if I could get Lobengula's permission to leave. It was about time I returned to my studies. I sent a note across to Colenbrander, who arranged with the King from me to have an audience the next morning.

We found the usual crowd of natives grovelling up to the King with various requests and reports. We were then called up and Lobengula told us to be seated. After the usual compliments Colenbrander explained that I wanted permission to go out with the Hottentot’s wagon. “What do you want to go away for?” the King asked, turning to me. I told him that I had to return to finish my training as a doctor. He thought for some time and then answered, “All right, you can go, provided you come back here and doctor me when you are finished.” I said I would and I meant it, but he was dead by the time I was qualified in 1893. The ‘Old Buster,’ as we often called him, was very friendly and said he was sorry to lose the ‘picannin white man.’ We bade him “Goodbye” and cleared off before he could change his mind.

I had also got permission to go round and say goodbye at the different camps. I was sorry to leave Colenbrander and Condon, who been good friends, also dear old Balane. My luggage was carted off to the wagon where the troopers were, ready to start, and off we went late in October. What a funny crowd it was that we travelled with! They only spoke Cape Dutch and were a big family. One old man and his wife, their sons with their wives and several children. These, with the two BBP troopers, had to be my constant companions as far as Mafeking. It was a light ox wagon, practically empty except for our kit and food, so we could travel fast, we each brought our own supplies…

That evening we reached Gubulawayo, where we saw Jimmy Dawson at his store and he told us all about Thompson and his flight from the King’s Kraal. He said that Thompson had seemed nervous and frightened, but had never told him, Dawson, what was the matter, nor that he was running away. “He never even warned me,” he said, “or told me what he had heard. I still have his cart and horses here.”

From there we trekked on through Figtree and Plumtree, doing a bit of bird shooting on the way, mine was the only shotgun, the others having rifles. The severe drought had driven most of the game away to where water was more plentiful, but there are always a number of the red-legged pheasants, or Franklins. They were shy birds and difficult to get within range of a shotgun; they could run like hares with their long legs. In the end, we found it easier to shoot them with a rifle…One afternoon we outspanned near some kopjes about 15 miles from the Ramaquaban River. The thorn bush was very dense and it was hard to see more than a few yards ahead, so I took my gun and went onto one of the hills to look for partridges…After going a few hundred yards, I could not see any sign of the wagon in the thick bush. I was sure I was returning in the right direction, but after wandering about I could see or hear no sign of the camp. It was getting dusk and everything was deadly still, as it can be in the bush. I did not fancy getting lost in this dense bush, so I ‘cooed’ as loudly as I could, when a sleepy voice answered me from a few yards away: “For heaven sake, stop that noise, I want to go to sleep.” There was the wagon, just behind some bushes. I felt rather ashamed of myself. I do not know how I missed the wagon tracks; probably it had left no marks on the hard ground. The two troopers had a good laugh at me.

We trekked onto the Ramaquaban River the next day, crossed and outspanned on the south side. It was always wise to cross a river before outspanning; one never knows when it may come down in flood and so keep you waiting for days. Sometimes a river will come down in heavy spate even though there has been no rain in your immediate neighbourhood. If your wagon were to get stuck in the deep sand of a river and a flood came down, as it sometimes does, in a great wall of water, several feet high, bringing branches and even big trees with it, you might say ‘goodbye’ to your wagon and everything.

Lost in the bush

Early next morning, while drinking a cup of coffee, I heard bush pheasants calling a few hundred yards down the river, so, as we needed game, I took my loaded shotgun with four cartridges in my pocket and went after them. I saw them running into the bush to the south and wished I had my old dog Grouse to find them for me, but I had of course, to leave him with Arthur. I followed them as best I could for a mile or two, but they always kept just out of range.

After an hour of this, I thought I would return, it was a cloudy day, which was most unusual and although there was no sign of rain, the sun was obscured. That did not worry me for I was sure that I knew my way and that all I had to do was to strike the wagon track from Tati or the river, either of which would lead me back to camp. I walked for an hour or two and saw no sign of the river or the wagon track. The bush, well away from the river, without being really thick was made-up of trees all about the same height; they were not very high, but just thick enough to prevent me from seeing more than a couple of hundred yards ahead; there were occasional huge red antheaps. I tried climbing a tree to see if the river was visible, but could not see over the other trees…

I was dressed in my shirt, breeches and boots, with three cartridges, my knife and a few loose matches in my pocket. They were of the red-headed sulphur kind, very common in those days that you could strike without a box. I was getting frightened now, as I had been away some hours. I hurried towards what I thought was the north. I found a big cream of tartar tree (Baobab) and from the higher branches I could see over the bush, which stretched over the country like an even blanket for miles and miles without a break…

Illustrated by Mary Vaughn-William: Baobab and San hunter-gatherers

I started off and walked until nearly dark, but I found neither camp nor drift. I was exhausted by this time and there was only one thing to do; find a place where I could get some sleep and cook my bird…There was plenty of dead wood about so I made a good fire and when it was well alight and burning fiercely I scraped a hole in the red hot ashes, shoved the pheasant in, feathers and all and covered it with more ashes. I did not even clean it…When I thought the bird was cooked, I raked it out and split it open with my knife. The fire had fused the feathers into a cake-like covering, which I could peel off just like a jacket. The insides also came out in a ball, and the flesh, cooked to a turn, was simply delicious.

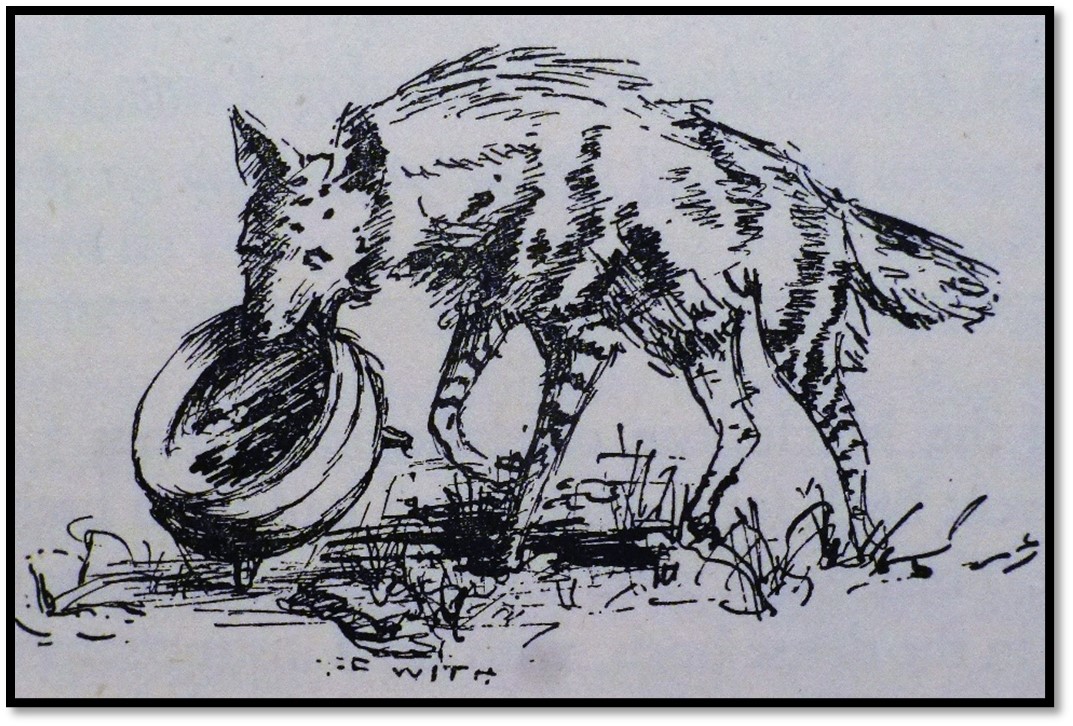

I then made three big fires round the tree, scraped a hole in the sand for my hip and lay down with my gun loaded with my last two cartridges and was fast asleep in no time. In the middle of the night, the dreadful, howling, wailing eerie noise of hyenas woke me up; I am sure an Irish banshee could not sound worse. They were not far away and I could see the glitter of their eyes, gleaming green in the firelight. I put more wood on the fires and was tempted to throw a burning brand at them, but the dread of starting a bush fire prevented me. I decided to climb the tree, but it was quite impossible to get comfortable or to sleep…In the end I had to risk lions, climbed down and slept solidly till dawn…

Illustrated by Mary Vaughn-Williams: Hyena off with our cooking pot

I went down to the river, had a drink and started walking on westwards up the river. After five or six miles, I was convinced that I must be above the camp although I had no recollection of crossing the wagon tracks. I started walking back eastwards down the river and after about five or six hours, when I must have covered 15 or 20 miles, I came to the place where our camp had been. Alas, the wagon, was no longer there; I could have wept. The only live thing I could see was a family of warthogs grubbing around. Tired and hungry I laid down and went to sleep, but I was awakened by a sound near me and found a Makalaka[xxv] of middle age sitting there, who said he was looking after Matabele cattle some way down the river. He said that the wagon had left the afternoon before. While I was talking to him, the two troopers rode up; they said they had been hunting the whole countryside for me…I rode behind one of them to the camp which was a few miles further on and was completely gone in. I know of nothing more trying to the nerves in being lost in the bush…I am sure that my experience started my hair turning grey.

I meet Dr Jameson and party at the Macloutsie: Matabele Thompson again: On to Palapye: we entertain Khama

We trekked on quietly through Mangwe Pass on the road to Tati.[xxvi] The Hottentot family were a queer crowd; the old man or one of his sons drove the wagon, but the driver rarely got off the front seat unless the road was so bad but that there was a danger of being thrown off; then whoever was driving would put one foot on the disselboom and jump for it. They all wore tattered European clothes; the women yellow faced and wizened wore sun bonnets and had very big buttocks. They chatted incessantly in Boer Dutch. They were a good-natured crowd and full of jokes amongst themselves; from what I could understand pretty vulgar ones at that!

…After the oxen had a long tiring pull through sand, or up a long rise, it was customary to give them a good rest to get their wind back and to relieve themselves. To stop the team the driver would give a long drawn-out cry of “Aah now” and the oxen would all stop instantly. The Hottentot driver would jump off the wagon and shout, “piss kinners, piss kinners.” The oxen immediately relieved themselves. At the same command, everyone on the wagon, men, women and children, jumped off. The women squatted and the men undid their breeches and they all relieved themselves. This happened so often that we became quite accustomed to the unusual sight.

We reached Tati with no further trouble, where we met Major Sam Edwards again. He was most hospitable, putting us up and feeding us well. He was anxious to hear all the news from Gubulawayo and then told us how Thompson had arrived scared stiff, in the early morning, quite sure that we had all been massacred. He had insisted on borrowing a cart and four mules and could hardly be induced to take any rest. He was quite sure the Matabeles were after him, and in spite of all that old Sam could say, nothing would stop him; he was off as fast as he could go. I believe he got relays of mules on the way to Mafeking…

Illustrated by Mary Vaughn-Williams: Sam Edwards 'Interior Sam'