Snatched from death in a flooded river

This article is about the perils of maintaining the Telegraph line in 1893 with the incident described told by (later) Lieutenant-Colonel Dan Judson, then inspector of Telegraph's.[1]

Lt-Col Dan Judson lived at Kirton Farm, Heany Junction

Judson as inspector of Telegraphs in 1893 had charge of the whole of the Telegraph system in the country. His most vivid memory of the early days was swimming the Tati river, then a raging flood, an adventure which almost cost him his life. His main task was to keep open the line of communication with the Cape. No easy task when it is explained that the iron telegraph poles terminated at the Nuanetsi (present-day Mwenezi) river and from that point to Salisbury, a distance of about 260 miles (414 kms) The line was carried on wooden poles except for the section from the Nuanetsi river to Fort Victoria (present-day Masvingo) which was consisted of a mix of wood and iron poles.

At this time the occupation of Matabeleland was in progress in 1893. Judson received an urgent message from Cape Town to arrange for a light Telegraph line from Palapye, Khama III’s chief town to Tati, and from that point to Bulawayo. At the time the only means of communication was by Heliograph between Fort Macloutsie (the headquarters of the Bechuanaland Border Police) and Tati and its working depended upon clear, sunny days which were then in November, few and far between. Judson went on from Palapye on the heels of the Southern column and hired a salted horse (guaranteed against sickness) and with light equipment including a notebook, some underwear, a small flask of brandy and some cigarettes, and set out on a wet day. His raincoat was not the best material and he was soon soaked to the skin. The horse, he said, was the slowest thing alive, but he put this down to the salting process and although he fumed at the delay, he felt some comfort in the thought that it was better to be ‘slow but sure’ than have a fleeter and better-looking horse and perhaps be stranded in the bush. After dark a thunderstorm with vivid flashes of lightning developed and as the road was rough and unknown to the rider, the horse was soon compelled to continue at walking pace.

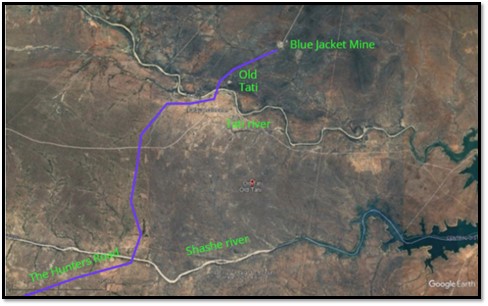

Eventually, they reached the Shashe, a wide river. It was flowing strongly and apparently rising. The horse did not like the look of it any more than the rider did, but the crossing was effected although the water was up to the girths. A flash of lightning revealed that it was 11pm, but Judson was cheered by the knowledge that he had safely negotiated the Shashe. The Tati river was the next obstacle. A hurried meal was made of bread, biltong and brandy and then the journey was resumed. A little later a few lights were seen twinkling in the darkness and the horse broke into a jog-trot at the sight of them. Presently when the lights were clearer, the heavy roar of a river in full flood was heard. Very fearsome the mass of water looked, but with shelter and comfort to be gained after crossing. Judson endeavoured to persuade his horse to enter the water. But neither whip nor spur had the slightest effect, and the rider, after half an hour's work, gave up the attempt. Then a moment’s calm reasoning convinced him thar the horse was right.

Google Earth: Shashe and Tati rivers in relation to Old Tati

On looking round, he saw a faint light. Towards this he made his way and reached a tented wagon in which Dutch travellers accommodated him for the night, although they were at first unwilling. The horse had by that time been unsaddled and tethered to a wheel of the wagon. The rain continued all night and in the morning Judson found that his horse had broken loose. The Tati river was then overflowing. It was now a mighty, muddy torrent and as he gazed at it felt grateful to the missing horse for its common sense. In having refused to take him to certain death in the flooded river. On the other side of the river was what is now known as Old Tati on the site of the Blue Jacket mine.

For two days Judson had to remain with the hospitable Dutch people in their wagon. Part of the time was spent in a shooting match – entrance fee five shillings each, which the Dutchman won - with a soapbox for a target. The missing horse was recovered, but with the river falling, Judson decided to swim across. He climbed a tree and with a handkerchief tied to a stick began some flag waving. It was not long before he attracted the attention of a uniformed man - an army signaller luckily who rushed into a tent and returned with a signalling flag and signalled, “Who R.U.?” From his perch Judson explained the situation and said that in an hour’s time he was going to swim the river, asking if they would be ready to help him. “Right O” was signalled back.

At the appointed time he stripped to the skin, tied a vest and socks on his head and going about a hundred yards above the drift slid into the water. Full of confidence, he struck out, watched by a large number of men on the other side. He headed upstream to avoid missing the drift as the bank on both sides was steep. He got on famously until well into the middle of the river, when to his horror, he saw a black object coming towards him. My God, he thought, a crocodile! As it reached him, he threw up his arms and went under. As he did so, something struck him a blow on the arm. It was without doubt a log! When he came to the surface again, he had swallowed quite a lot of muddy water and lost much valuable distance. The small bundle on his head felt very heavy, and for the first time Judson began to despair. Feeling somewhat feeble, he struck out once more, but it seemed now as if he would be swept past the drift where there would be no further hope for him. Encouraging shouts reached him from the men at the drift, but he felt exhausted. Three or four more frantic strokes and everything went black. He had a dim recollection of a hand clasp…then silence. Was this the end?

How long afterwards he knew not, he found himself lying on the bank. Men were around him, one saying, “He is full of water. Pick him up by the heels and let it run out.” Judson had enough strength to dissent. Wrapped in a military cloak, he was taken to the Tati mess and made much of. A rub down, a bottle of English stout and some hot food worked wonders. In an hour or two, he was as fit as ever. Then he learned that the hand clasp had been given him by Captain Lindsell, at that time, military commander who was at the end of the chain of hands that had effected the rescue as the drowning man was being swept past.

Three days later, Judson re-crossed the river without difficulty, this time on horseback, and was shown the body of his “guaranteed salted” horse. It had died of horse sickness!

The Tati river flowing near Francistown

Reference

Occupation of Matabeleland: A Souvenir

Notes

[1] At the time many people thought Dan Judson was worthy of a Victoria Cross award for his role in the rescue of those besieged at the Alice Mine, however at the time only regular serving individuals qualified for the award. Judson is featured in a number of articles on this website;

- Dan Judson and the Africa Transcontinental Telegraph Co under Mashonaland Central

- The June 1896 Mazoe Patrol skirmish with detailed accounts from those besieged and their Mashona attackers under Mashonaland Central

- The Victoria Cross (VC) medal recipients connected with this country under Mashonaland West