Rinderpest

Most of the following article is abbreviated from Frank W. Sykes' book: With Plumer in Matabeleland

As we have seen in Stanley Hyatt’s account of life as a transport-rider, the onset of Rinderpest paralysed the transport system which was dependent on the ox-wagon and moreover caused widespread social and economic distress within African communities. The Rinderpest travelled from Somaliland south, infecting game and cattle into Uganda and by 1892 Sir Frederick Lugard, British soldier and explorer, encountered its effects in Northern Rhodesia (Zambia)

The Zambezi appears to have been the most effective barrier to its spread southwards, but even this failed and in 1896 made its first appearance in present-day Zimbabwe. The well-developed transport system probably speeded up its spread. Within twenty-five days of its first reported occurrence, it was at Tuli, moving at a speed of twenty miles a day and by November 1897 it was killing game at Groote Schuur in Cape Town.

Apart from spreading death, the spread of Rinderpest was attended by widespread suspicion and rumour with many Africans thinking that the destruction of their cattle herds and the accompanying suffering and even starvation, was the result of the white man’s malevolence.

Directly after the ravages of the fatal Rinderpest disease vague rumours began to circulate of an intended rising of the Matabele (Ndebele). Upon the outbreak of the Matabele Rebellion, the BSA Company enrolled volunteers to form the Matabeland Relief Force and recruiting commenced at Kimberley and Mafeking (Mahikeng) in April 1896.

Frank Sykes was in a troop largely composed of men just released from the abortive Jameson Raid. He says at first their tales were interesting, but after each individual version of “how we went into the Transvaal” and the number of hours in the saddle without food and sleep, the narrow escapes, life in Pretoria gaol, their treatment by the Boers, etc., had been told and re-told, the subject became somewhat threadbare!

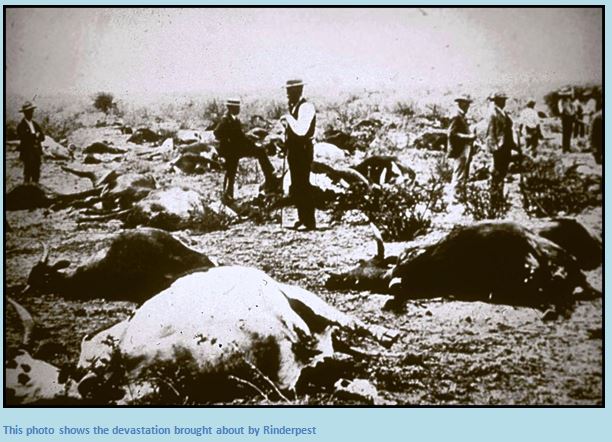

By the fifth day of their march from present day Mahikeng they are a Crocodile Pool and Sykes comments on the horrible stench arising from the decaying carcases of dead oxen – victims of the rinderpest – which lined the roadside. It was a common occurrence to see the remains of whole spans, twenty or thirty, lying about within a radius of 100 yards. Often camp was pitched right alongside places where these poor brutes had dropped dead, and the all-pervading effluvia arising from their remains in every stage of decomposition, offended the nostrils throughout the night. The air never was entirely free from this pestilential taint, and to a certain extent the troops became inured to it.

Now and again wagons were met with – derelicts of the veldt – laden with timber, furniture and cases of all kinds of merchandise, drawn up in the bush just off the road, and left to look after themselves. All the trek oxen had succumbed to the [Rinderpest] plague and the transport-riders had had no alternative left them, but to abandon their loads.

It is fact that several troops of the BSA Police freely plundered whatever they found on or near the wagons, breaking open cases of liquor, provisions, clothing, etc. and wantonly destroying or exposing to the weather what they were not in a position to make use of. American clocks were set up as targets. Hats, ties and other articles of clothing were hung about the trees. Champagne and liqueurs were drained out of tin mugs, while whisky, brandy and other spirits were tossed down by the bottle.

C. van Onselen. Reactions to Rinderpest in Southern Africa 1896-7. Journal of African History VIII. 1972.

F.W. Sykes. With Plumer in Matabeleland. Books of Rhodesia. 1972.