Richard Frewen, the man who annoyed Lobengula and the consequent deaths of the Colonial government emissaries on their way to the Victoria Falls

Frewen’s journal was copied from the original into a manuscript volume along with many of his original letters to his mother and sisters, apparently by Dr F. Storr, tutor to Richard and Moreton Frewen. Richard Frewen’s hand-writing was notoriously difficult to decipher; he kept five books recording his travels including a logbook for observations, a workbook for calculating positions and heights, a wine and stores book, a journal kept by himself and a diary of brief entries kept initially by Robertson, the trek manager and then by himself. His attempts at photography appear to have been successful, but all seem to have been lost when the family home was burned down in 1921.

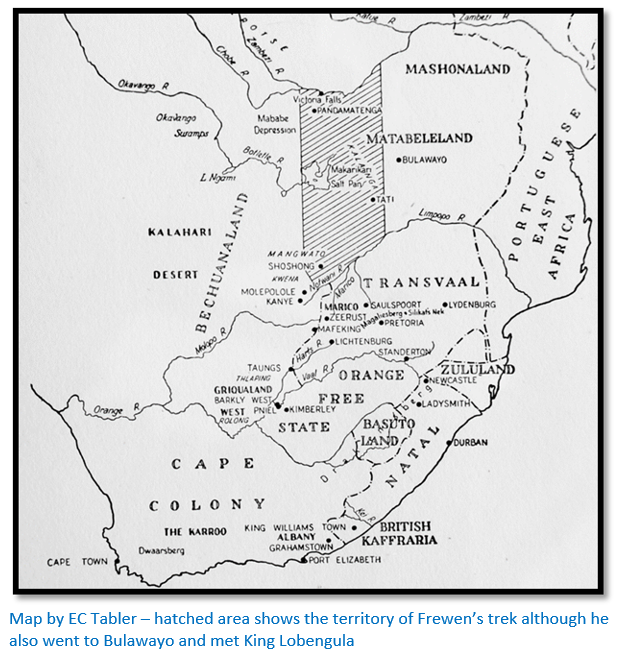

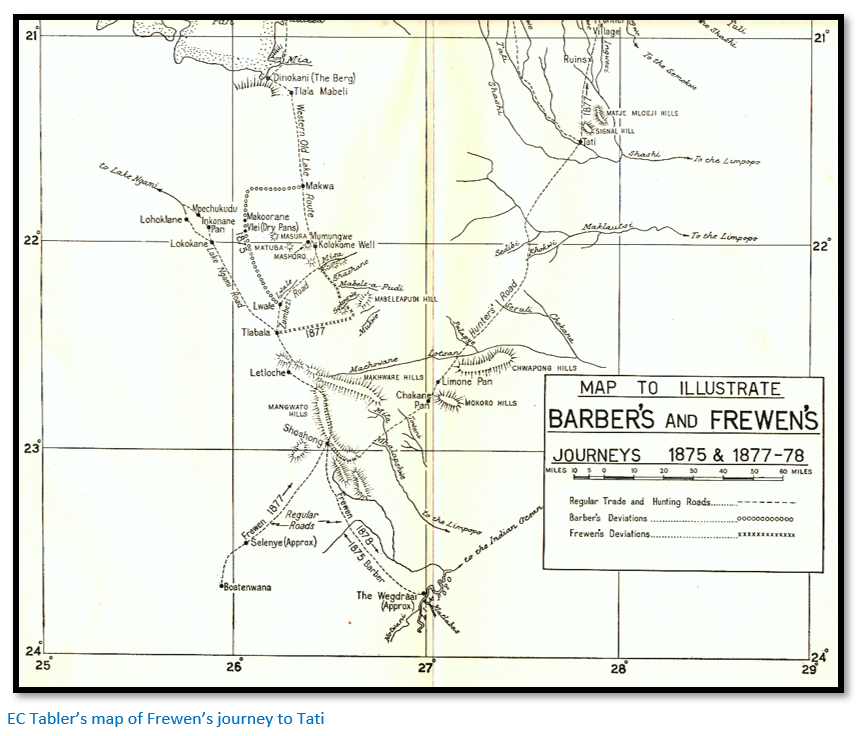

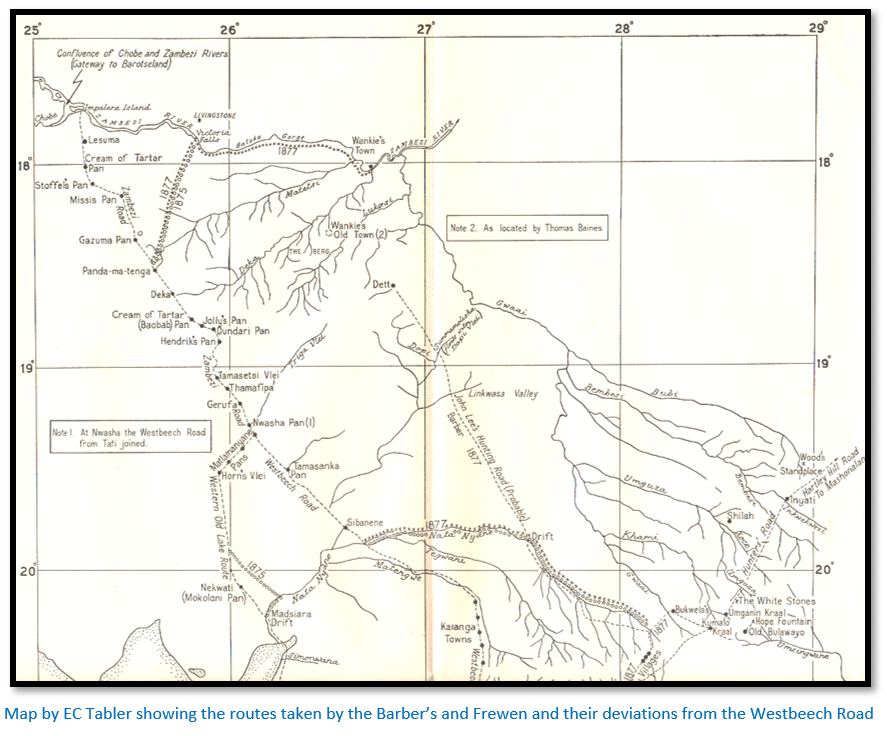

Edward Tabler edited the material for publication in Volume 1 of the Robins Series from where most of this article was sourced. The material relating to Richard and Moreton Frewen’s adventures in America is covered in considerable detail by Dr P. Roberts on the website: http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/cattlefrewen.html

Born to position, wealth and influence and well-travelled by 23 years old

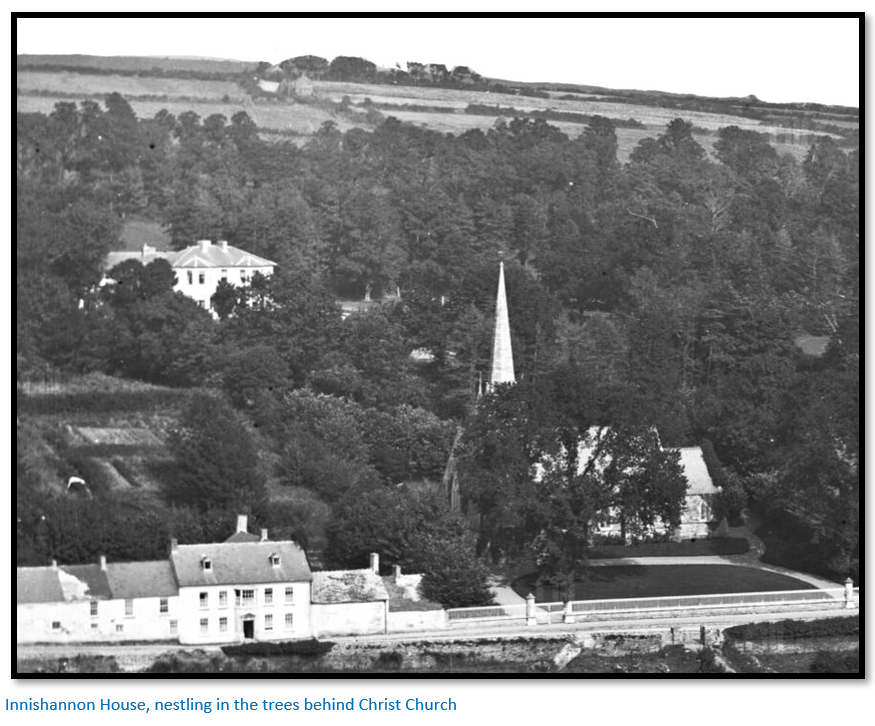

Richard Frewen (known as Dick) was born in Cold Overton, Leicestershire on 25 February 1852 to Thomas Frewen (1810 – 1870) and his second wife Helen Louisa Homan. His father Thomas had five children from his first marriage with Anne Carus-Wilson and then five more children with Helen and was a Justice of the Peace, then High Sheriff of Sussex in 1839 and MP for South Leicestershire from 1835 – 1836. His father died in 1870 leaving eighteen-year-old Dick with over £16,000 and the 2,722 acre Frewen estate in Innishannon in County Cork which included arable land and woodland, fishing rights on the river Bandon, a stone quarry, Innishannon House and the village of Innishannon.

He attended Dr Storr's school at Brenchley, Kent, c1861-1865 and schools at Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire, c1866-1867 at Shere, Surrey, c1868 and Stratford Abbey near Stroud, Gloucestershire, c1868-1870. During 1871 Richard attended a school at Parsons Green, Fulham before he accepted a commission in the militia stationed at Dover Castle; having resigned his commission in October 1873[i] he went on two transcontinental trips between 1872 - 1875, one a circumnavigation of the globe, the other involving travel in Asia. By the age of 23 he had visited Russia, Kashmir, China, Japan, Java in Indonesia and India and was a member of the Royal Geographical Society although he only ever contributed one short note on the Zambezi river.

First journey to South Africa in 1876

Frewen arrived in Cape Town in mid-July 1876 planning to journey into the interior of Southern Africa, however he had missed the South African winter, the dry season and the best time for travelling so he changed his plans and travelled instead to the Eastern Cape of South Africa.

His father was an acquaintance of Sir Henry Barkly and Sir Bartle Frere (successive Governors of Cape Colony 1870 – 1877 and 1877 – 1880) and Barkly assisted Frewen by having Charles Brownlee, the Secretary of State for Native Affairs, include him in his party to the Eastern Province, then called Kaffraria, to monitor ‘increasing levels of hostility among the native tribes’ and to persuade them not to fight. They left Cape Town on 26 July 1876 returning in early September and although brief, this trip provided the groundwork for a journey to the Victoria Falls Frewen planned to make the following year. He hoped to defray his expenses by shooting elephants and trading, but as it turned out he bagged no elephants. Before he left the Cape on 23 September he placed an order for a wagon to be built for him for his journey into the interior the following year.

Journey to Zambezia

He tried to get the Royal Geographical Society to support him on an exploratory journey to Zambezia from the south through Matabeleland and over the Zambezi river to Lake Bangweulu and the swamps; the region where David Livingstone had died in May 1873 before exiting East Africa through Zanzibar. Whilst the Royal Geographical Society were happy to make him a fellow of the Society, they did not support his request for financial assistance. Frewen knew Captain James Henry Bowker,[ii] Colonel of the Frontier Armed and Mounted Police (FAMP) in 1870 and seems to have arranged to travel with their nephews, Fred and Hal Barber.

Frewen left England on 16 February 1877 - later than he had initially intended and accompanied by six tons of stores and equipment including scientific instruments, saddlery, an ice making machine, wines, trade goods, over 750kg of tinned and preserved foods, a photographic outfit and a personal battery of seven guns.

He arrived in Table Bay in March and purchased an additional 1,800kg of stores before travelling to Kimberley by train and mail coach which he reached on 30 March and where he met Fred Barber. [See Freddy Barber’s narrative to the Victoria Falls in 1875 and to Matabeleland in 1877 under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] Frewen found Kimberley “dismal” and complained of the high price of champagne at 18 shillings a bottle. The Barbers introduced him to Robertson who he took on as trek manager and he engaged an English boy named Parks, who proved a liability.

The trek north begins with continual desertions of his servants

Frewen and his party left Kimberley in late April trekking north through present-day Botswana and his troubles soon began. The wagons were overloaded with the provisions Frewen had brought with him and stuck often in the sand; the disselboom broke, water was scarce, supplies were lost or stolen and they often took the wrong road. Four servants engaged in Kimberley and paid in advance deserted and Robertson and Frewen drove the wagons themselves, were forced to inspan and outspan and undertake all the various camp tasks.

Beyond Taungs the oxen strayed one night and as Frewen and Robertson were out searching for them, all of Frewen’s cash, about £50, was stolen from the wagon. Six oxen were not recovered and all their newly recruited servants deserted. Parks quit soon after with Frewen believing he had the stolen money in his pocket. Richard Clarke of Shoshong lent Frewen money and experienced trekkers as far as Kanye. Frewen’s inexperience of travelling in Africa is clearly apparent. The roads were bad, game scarce, the country dry, bare and uninteresting and “the natives enough to make a saint swear.”

The continual desertions of his servants demonstrate an incompetence in dealing with local people by Frewen. His treatment was probably too harsh and his poor ability as a hunter probably also contributed to their dissatisfaction. They expected a good supply of meat when working for Europeans and this was not provided by Frewen. They made their dissatisfaction known by taking their blankets from the wagon and walking off.

Short-handed, he had to work hard and was constantly awake supervising the few remaining natives; meals and trek hours were very irregular and the food poor. His watches went wrong, his photographic equipment was likely to be broken by the jolting wagon and half his instruments were broken or lost. Finally they arrived at Shoshong on 5 June…the journey from Kimberley which should have taken three weeks had taken nearly seven weeks and Frewen realised that he would be too late to cross the Zambezi river that year.

Leaving Shoshong on 12 June they travelled on the well-beaten Westbeech road to the east of the Makgadikgadi salt pans and reached Pandamatenga on the Matetsi river on 9 August. Many interior men, Boer and British helped him out and new servants had to be hired as old ones deserted often taking with them his live-stock, money, scientific material and merchandise that he carried to trade or buy favour from local tribes.

Frewen reaches the Victoria Falls

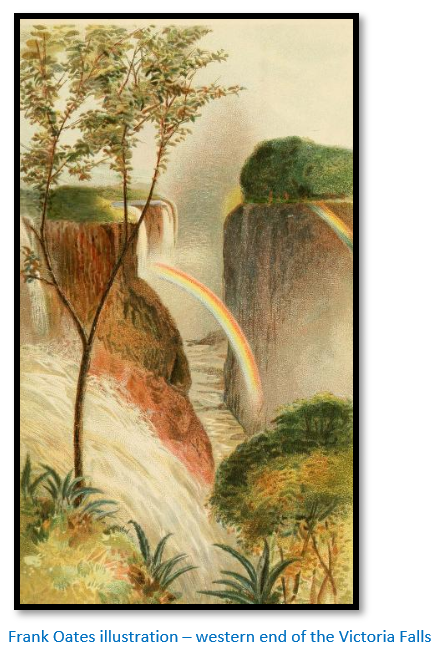

Tsetse fly prevented further trekking by wagon north of Pandamatenga and Frewen walked to the Victoria Falls where he stayed from 14 – 18 August; his impression of the Victoria Falls was one of admiration and awe, recording that: “certainly it is the first waterfall, I should say, in the world and is as much finer than Niagara as Niagara is finer than [the Rhine Falls at] Schaffhausen.” He calculated the height of Victoria Falls, using a boiling water thermometer, to be around 2900 feet [actual 3,260 feet or 994 metres] His photographic equipment that had been carried with such care and effort failed to work, a difficulty he later speculated was due to the effect of the hot climate on the chemicals.

He then walked down the Zambezi river to Wankie’s town, his journal states: “A good many of my boys left and the rest were in a state of insubordination, not liking the idea of carrying heavy parcels over the hilly ground and also to leave the camp where they expected to live in idleness on the corn I had bought.”

Plans for an expedition to Lake Bangweulu and the swamps are thwarted

His plan had been to remain in the area south of the Zambezi river until April 1878 and then during the dry season to proceed to his final destination of the flood plains of Lake Bangweulu, but by the end of August this plan had come apart.

For Thursday 23 August 1877 he records: “We took possession of an empty house belonging to Westbeach [Westbeech][iii] We had not been long there and had just made an exchange of presents with Wankie’s people, when an armed party of Matabele came up and instantly began their small attempts to bully and extort presents. They frightened Wankie’s people into bringing them goats, beer and other presents.”

Friday 24 August: “These brutes of Matabele had the cheek to order us to give up our guns and prevailed on Wankie’s people to endorse their order, when we declared we would not give them so much as a bead. They drove our boys away and we were without a single man except Jem, Westbeach’s boy, who had been robbed on the road of everything except his gun by the Matabele…”

A standoff followed, with Frewen revealing a fatal weakness in diplomacy. His journal notes he soon: “had them all in on their knees to apologise for their conduct” having first threatened: “to have them killed by their King Lobengula if they did not.”

On Tuesday 28 August his journal states: “…Wankie sends over to say he wants to trade and I go across with a lot of goods. [i.e. he crosses to the north shore of the Zambezi river] They evidently think I am young and foolish and they may cheat me to any extent; on my refusing to be cheated, they refuse to trade and o after showing no end of things and measuring wire and beads and calico for about four hours, I get angry and tired of the brutes, pack up and bid good day for once and all to Wankie.”

Thursday 30 August his journal states in addition to endless arguments with local natives: “From different reports the Matabele seem to have been plundering all the traders about here; so we were not the exception, but the rule, as to their attacking us. But we seem to have been the exception in not having been plundered…”

Tuesday 4 Sept “Begin to get ready a scarum[iv] Blockley, Robertson, J. McKenny[v] and a lot of boys arrive before it is finished…The Matabele have been levying a tax on all the white people in here, nothing more than blackmail…”

Wednesday 5 Sept: “…I wish to cross the river with Blockley, but Wankie who is in high dudgeon because I sat on his lion skin when I paid him a visit and would not give all the presents he wanted of me, won’t let me cross the river and will not hear of my passing through his territory…”

Frewen once again failed to understand local customs. Wankie was a vassal of the Barotse King, not Lobengula and he would have understood this better if he had made friends with George Westbeech at Pandamatenga who was on good terms with both the Barotse and the amaNdebele.

Additionally he arrived on the Zambezi river too late to travel further afield and miss the summer rains and fever season. This was because he left England late and he travelled too slowly; initially with an excess weight in goods, but also because of the continual desertions of his servants due to his poor attitude towards them.

The amaNdebele warriors who attempted to bully Frewen were trying to see what they could get from him – no doubt they thought they were far enough from Gubulawayo to get away with it. Frewen faced them down and his servants who had disappeared when the amaNdebele arrived, reappeared when they were gone.

Lobengula sent a message on 26 October to the Europeans at Tamasetsi Pan denying that he had ordered all of them out of the country, or that he had authorised the robberies and he did return as much of the stolen property that he was able to recover. Tabler argues that the Barbers were not molested in the same way by raiding parties of amaNdebele as the hunters gave them small presents which were expected at such encounters.

Monday 17 Sept: “…Rode over to Pandamatinka[vi] where I met Westbeach, Dr Bradshaw,[vii] etc. Most of them very drunk.”

Tuesday 18 Sept: “Found my brandy casks had been nearly emptied of their contents, over 60 bottles had been stolen. This was very bad as they were in the charge of white men.” The wagons had been left at Pandamatenga; one suspects the same crowd who had been drunk the previous day, had been responsible for the theft! The same day he fired J. McKenny who he had accused of stealing tobacco and dried fruits a few days previously and “his other boy, whom he had engaged against my wishes, had bolted with my elephant gun, ox, etc.” and says he could not stand his thieving and lying any longer.

Wednesday 19 Sept: “Westbeech, Nicoll, Collison and others came over from Pandamatinka, all still very drunk…”

Thursday 20 Sept: “Gave a breakfast. Discussed the aspect of affairs up here with Westbeech and Sellew,[viii] both agreeing that the country was utterly worked out. Trade and hunting ivory being things of the past on this side of the Zambesi.”

Friday 21 Sept: “A letter which we had been writing in order to send to his Excellency Sir Bartle Frere was signed by all the traders. It was to ask assistance for the protection of trade and life in these parts. Westbeech and the Pandamatinka division left soon after.”

Frewen’s letters of protest

On 18 September a letter was sent to the High Commissioner for South Africa on behalf of the, “traders, hunters, and Europeans in the Zambezi country” which complained about Lobengula’s treatment of them.[ix] Frewen was acknowledged to be the author of this letter, which is quoted in the notes, although the other signatories are not known as the letter was later destroyed.

The letter (copied in the endnotes) states that H. Byles,[x] an old timer who was in the country by 1868 and a former partner of Karl Meyer the hunter was robbed by the amaNdebele. However in Frewen’s journal of Monday 6 August 1877 he states “sold Byles two cases of brandy and bought jam, etc. Made rather a bad deal…” but I can find no reference in his journal to any robbery.

Two more letters were written to the Under Colonial Secretary in Cape Town from Wankie dated 29 August 1877 and from Daka [Deka] on 21 September 1877, the main points of which Edward Tabler summarised as follows:

- the black mail levied on the traders by the bands of natives under petty chiefs, headmen, etc. which are known to be acting under King Lobengula’s secret instructions. Lobengula pretends ignorance of the matter and offers to punish the offenders if they are pointed out, which obviously in most cases it is impossible for the victims to do.

- The trade on the Zambesi is estimated at £200,000 per annum and sufficiently valuable to claim protection from the Colonial government.

- If there is no answer to the letters from the High Commissioner, Lobengula will construe this as indifference on the part of the Colonial government to these outrages and matters will become worse than ever.

- If the Colonial government wish to bring Lobengula under their protection that there would be little opposition from him or his subjects as he is not popular with his subjects and his brother ‘Kuruman’ is considered by the amaNdebele to be their rightful King.

The danger to life and property was clearly exaggerated – no details are known about the robberies except for Frewen’s note that Lobengula ensured the stolen items were returned. Once again Frewen showed a great ignorance of the real situation particularly in regard to (4)

The journey south from Pandamatenga

On 16 October Frewen decided to return south upon seeing that his path to the north was blocked. The rainy season brought with it an increased malaria risk and it was clear he was no longer welcome in the area. He made his way in a leisurely fashion via the Nata and Mangwe rivers on the Westbeech road to John Lee’s farm at Mangwe by 14 December and visited Gubulawayo for twelve days from 20 – 31 December 1877 and there the trouble began.

Gubulawayo and King Lobengula

Fred and Hal Barber welcomed Richard Frewen with a dinner before he visited Lobengula at his kraal. John Lee interpreted for Frewen in his interviews with the King. His journal has little to say about this period:

Friday 21 Dec: “Went down to the King’s. Rode down with Byles. Met there a very pleasant French missionary, his wife and niece. [This was Revd. Francois Coillard] They had been going to establish a mission-station in the Mashona country when they were turned back by the Matabele King. Had a long interview with the King, which was on the whole satisfactory. He is a clever man, very bigly built. I told him very plainly that he had ruined my enterprise and told him that I had reported it to my Chief and if he did not agree to what I had to propose, I should return and report the same to my Government.” There are no journal entries for 24 – 30 December and Frewen cleared out the following day.

King Lobengula was considered friendly to British interests and granted mining concessions and hunting licences to European hunters and traders in return for gold sovereigns, weapons and ammunition. The King knew Europeans liked a written document, so he would have his words translated and transcribed in English or Dutch by one of the whites in residence near his kraal and then later translated back by another. Once the king was satisfied with the document, the royal elephant seal would be affixed and it would be signed and witnessed by a number of white men and endorsed by one of the missionaries at Inyathi, or Hope Fountain.

Richard Frewen needed a scapegoat for his disappointments

Frewen had hoped to stay during the summer months in Matabeleland and make another attempt the following year into the region north of the Zambezi river, but he could not contain his frustration at what were his own shortcomings and accused Lobengula of wrecking his expedition and threatened the punishment of the British government.

Lobengula was already annoyed by the missionary Rev. Francois Coillard who in April 1877 with his wife and niece Elise had crossed the Limpopo river to establish a mission amongst the Banyai north of the Limpopo river. They by-passed John Lee’s farm at Mangwe and entered what was considered the amaNdebele territory without the usual permission. At the Bubye river a Banyai Chief stole some of their oxen; they struggled on to the Tokwe river where they were robbed and mistreated. An amaNdebele impi arrested them in December 1877 and they were taken to Gubulawayo as Lobengula's prisoners who prohibited them from preaching in his domains and forced them to leave in March 1878 for Bechuanaland.[xi]

Frewen was similarly ordered out of the country.

Fred Barber’s account of the incident

Fred Barber was resident with his brother Hal in Gubulawayo at the time. He states that Frewen had strayed from Khama into Lobengula’s territory “the disputed territory” between the Motloutse and Shashe rivers and the amaNdebele had seized his muskets and taken them to Gubulawayo. This is incorrect, but his account is worth noting.

Frewen handed over a letter of introduction from the Governor of the Cape Colony, Sir Henry Bartle Frere and informed Lobengula that he was a great chief and would not stand this nonsense; threatening to return with an army and “eat Lobengula up.” He then returned to his wagon and dressed in his volunteer’s uniform and hoisted the Union Jack!

This ridiculous behaviour only annoyed Lobengula and Frewen was told to clear off and to bring his army back at once. The immediate consequence was that the traders and hunters at Gubulawayo found that Lobengula’s displeasure resulted in a change of manner; there was no more meat and beer and they were frequently asked when they expected their great white chief and his army to arrive! [See the article Frederick “Freddy” Hugh Barber, hunter, trader, artist – visited the Victoria Falls in 1875 and Matabeleland in 1877 under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Fred and Hal Barber and the other traders at Gubulawayo were prevented from leaving the country for some weeks, but eventually Lobengula’s good humour and friendship was restored and the King told them his heart had softened and they were free to leave his country.

The journey back

Robertson, the trek manager, left Frewen at Gubulawayo and he trekked the usual road through Lee’s, Tati and Shoshong crossing the Marico river into the Transvaal on 28 February 1878 which he considered “English ground.” He had further discussions with colonial officials regarding his grievances with being unable to travel north of the Zambezi before returning to England in early June stating: “It is an awful country, and the most loathsome and despicable people in the world.”

At Pretoria Frewen told his troubles to Sir Theophilus Shepstone, Administrator of the Transvaal and later Sir Bartle Frere in Cape Town.

The Colonial Office response

In response to Frewen’s letters, Shepstone sent a British mission, approved by the High Commissioner Sir Bartle Frere, to meet with Lobengula to investigate the alleged complaints of the hunters and traders. The two emissaries, Captain R.R. Patterson and Lieut. T.G. Sergeaunt wanted to hunt big game and see the Victoria Falls and the Colonial government suggested they combine business with pleasure and paid £500 toward their expenses for carrying out this duty. They made contact with Lobengula in August 1878 and were received by him in a very friendly manner.

However the letter they carried was undiplomatic and they used tactless language and soon enraged the Matabele King. It has been suggested that Lobengula’s behaviour changed abruptly when Patterson mentioned the name of Kuruman or Nkulumane in what may have been a veiled threat.

Historian Edward Tabler suggests that the amaNdebele suspicion of the emissaries may have been aroused because they had not forgotten Frewen’s previous threats and thus may have believed that the emissaries were the vanguard of the army he had threatened would come to punish them.

The deaths of the Colonial Government emissaries

Three days journey from the Zambezi river on 20 September the two emissaries and their guide Evan Morgan Thomas, the son of the Rev. Thomas Morgan Thomas and at least two servants, died.[xii] The manner of their death, whether an accident or deliberate murder from drinking poisoned water, was never determined.

Lobengula maintained the victims drank water poisoned by “Bushmen” [Khoisan or San hunter-gatherers] but he would not permit any Europeans to investigate. The King had tried to persuade the emissaries to postpone their journey to the Victoria Falls and had privately warned Evan Morgan Thomas not to go at all.

Rider Haggard remarks that Patterson had the habit, for which his friends teased him, of always boiling his water and that it seems curious that Lobengula’s twenty native bearers all escaped poisoning. Haggard also tells a tale of some BamaNgwato hunting for ostriches who heard shooting and thought they might obtain some meat. On reaching the campsite by a waterhole, they saw the bodies of the three Europeans and two servants lying on the ground surrounded by armed native bearers who told them to be quiet and that the killings were by “order of the King.”

Frewen’s later life

This is not relevant to the article itself but fills in the subsequent details of Richard Frewen’s life and is from Dr P. Roberts on the website: http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/cattlefrewen.html

Having left South Africa in early 1878 Frewen and his brother Moreton travelled through Colorado and Texas with Frewen continuing on to England whilst Moreton stayed in Dodge City, Kansas. Moreton had seen a business opportunity in cattle ranching but lacked the finance and persuaded Frewen to invest some of his inheritance in establishing a cattle ranch in Wyoming. Frewen arrived in New York on 29 October 1878 with four Cambridge friends, among whom were Gilbert Leigh and James Boothby Burke Roche, son of Baron Fermoy.

They undertook a hunting trip in the Wind River basin in south west Wyoming, following which their Cambridge friends left and Frewen and Moreton decided, despite it being in the depth of winter to travel east over the Big Horn Mountains to view the open ranges between the Powder and Tongue rivers that a mountain guide had told them was ideal for cattle and was surprisingly entirely unoccupied.

This reckless decision to cross the Big Horn Mountains in mid-December nearly proved fatal for the small party as navigation was impossible at the top of the divide where deep snow drifts obscured the landscape and obliterated landmarks. Their quick-thinking guide caused a herd of migrating buffalo to stampede and clear a trail through the snow of the 10,000 foot pass. As the first Europeans to accomplish this feat in winter they were disbelieved when they first told their story to older residents.

Frewen developed a serious fever, but they fortunately found an abandoned hut on the lower slopes of the Big Horn Mountain and Moreton nursed him back to health over the next two weeks.

Following his recovery Moreton travelled east to purchase cattle for their new ranch whilst Frewen arranged the building of a log cabin which form the nucleus of their operations in Wyoming.

In later years a more imposing structure would be built on an outcrop overlooking a tributary of the Powder River that would be known locally as Frewen Castle whose primary purpose was to entertain guests and potential investors from England, including Sir Samuel and Lady Baker, the first Europeans to visit Lake Albert and the Frewen’s were pioneer cattlemen of Wyoming. The hardwood floors and rosewood staircase with walnut railings were all shipped from England. The structure burned down in the early 1900’s and is today remembered by Castle Street and Castle Creek in the township of Midwest, Wyoming.

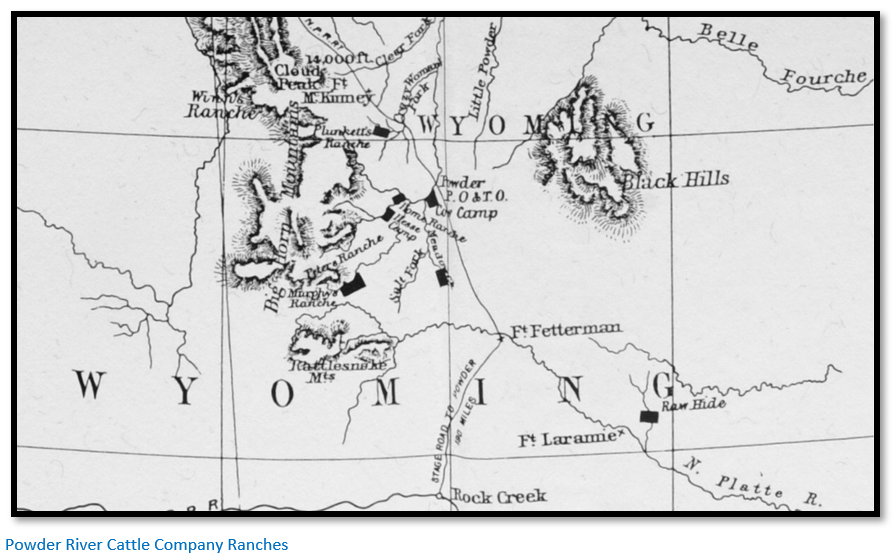

Initially 4,500 head of cattle were purchased: their ranch in Johnson County, Wyoming, called the ’76 Outfit was situated near the trading post where the Bozeman Trail crossed the Powder River, and on the former site of Fort Reno. It was 200 miles from the nearest railway point but was served by a stagecoach service that connected the transcontinental with the newly created settlements.

Their Cambridge friend Gilbert Leigh was elected to Parliament in the 1880 General Election but joined them for hunting trips at ‘Frewen Castle’ in 1881, 1883 and 1884. On 15 September 1884 while hunting at dusk in the Big Horn Mountains he stepped over the edge of Ten Sleep Canyon and fell to his death.

Another friend, Horace Plunkett, the younger son of the Lord Dunsany, moved to Wyoming in 1879 due to health reasons and established a cattle ranch on Crazy Woman Creek with Alexis and Edmond Roche, the brothers of James Roche, another Cambridge friend. Plunkett’s relationship with the Frewen brothers would become complex and dramatic.

In September 1881 Dick envisioned a plan to develop Yellowstone Park, at the time largely inaccessible, as a new tourist destination and he asked Horace Plunkett to be his business partner in his scheme. Access to Yellowstone Park would be via a stage coach from the nearest railway, but infrastructure such as hotels, boats and associated tourist facilities were required. The Yellowstone scheme required government permission and a government monopoly to provide tourist services within the park.

Plunkett was confident of the financial success of the scheme but thought Frewen: “the worst man of business I know except Moreton, who would be my other partner.” Plunkett noted in his diary that when they met Hoyt, the Governor of the Wyoming Territory to discuss the plan: “neither the Governor nor I could get in a word.” In a diary entry that would be somewhat prescient, Plunkett added, “I am afraid his unstable energy will upset the coaches.”

Moreton proved reckless with money and Plunkett noted the effect this was having on Frewen: “is going south for his health & poor fellow, how I wish me may regain it. His mind is preyed upon by the unsatisfactory relations between him & Moreton. But he has the pluck of Job” and the Yellowstone Park scheme ended when Plunkett’s father withdrew support.

Frewen and his brother Moreton’s business relationship deteriorated and on 17 May 1882 Frewen signed an agreement to sell his share in the ’76 Ranch back to Moreton. The “Beef Bonanza” fashion was just sweeping England and Moreton had just secured finance of $1.5 million to create the Powder River Cattle Company.

In 1883 Frewen had established the Dakota Stock and Grazing Company that bought the Hat Creek Ranch which “managed” a range of 600 square miles that could feed 17,000 head of cattle. They did not own the land; instead their cattle along with others roamed and fed freely on the grass of the public ranges. The boom resulted in overstocking of the public lands with an over-supply of cattle and an under-supply of fodder.

By 1884 the company was in financial trouble and in the following year Horace Plunkett was asked by the directors of the Powder River Cattle Company to replace Moreton as its manager. Plunkett found Frewen: “in a perfectly furious humour determined to oppose my management by every means in his power” and soon after they were not on speaking terms, only communicating in writing.

Plunkett’s row with the Frewen brothers got more tense when Dick told him: “that if his brother & he don’t get into power it is “war to the knife” between the Frewen’s & me.” In the meantime Moreton and his older brother Edward were appointed as directors to the Powder River Cattle Company and Moreton then confirmed his support for Plunkett. Frewen stated he was: “thoroughly disgusted with Moreton’s duplicity and determined to give up the fight.” Frewen refused any further contact with Plunkett and Moreton and Plunkett’s relationship was always rocky.

The Dakota Stock and Grazing Company went into liquidation in 1886 paying out $5 a share, but Frewen’s three thousand shares had been loaned to Moreton and he received nothing.

Innishannon House which Frewen had inherited from his father was rented from 1870 by the retired Church of Ireland Rector, the Rev. Robert H. Maunsell Eyre and his wife and Frewen only regained possession in 1890.

Frewen married Katherine Maria Affleck on 21 March 1891, the daughter of Sir Robert Affleck and the widow of Lt-Col Charles Wollaston, but she suffered from ill-health and they travelled frequently to places that might help her. Their efforts were in vain and Katherine died on 26 January 1895 in Montreux, Switzerland after just four years of marriage.

Just a year later on 17 August 1896 Frewen was sailing his yacht Florinda off Milford Haven when he was washed overboard. His body was not recovered. He was 44 years old.

In 1921 Innishannon House was burned to the ground by the Irish Republican Army during the Irish revolutionary period of 1919-1923 which saw at least 275 country houses deliberately burnt and destroyed.[xiii] Frewen’s hunting trophies and the originals of his logbooks and journal were destroyed in the blaze.

References

E.C. Tabler (Ed) Zambesia and Matabeleland in the Seventies. Volume 1 of the Robin Series J. Desmond Clark (Ed) Chatto and Windus, London. 1960.

E.C. Tabler. Pioneers of Rhodesia. C. Struik, Cape Town. 1966.

https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ Letters from his brothers Moreton and Richard Frewen

H. Rider Haggard. The Last Boer War. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co Ltd, 1900

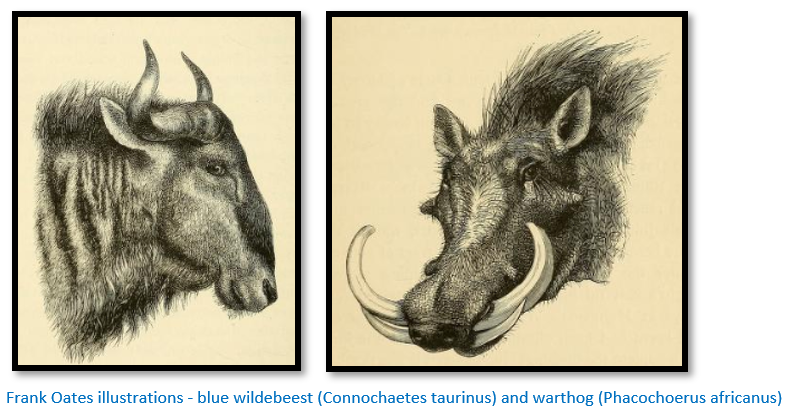

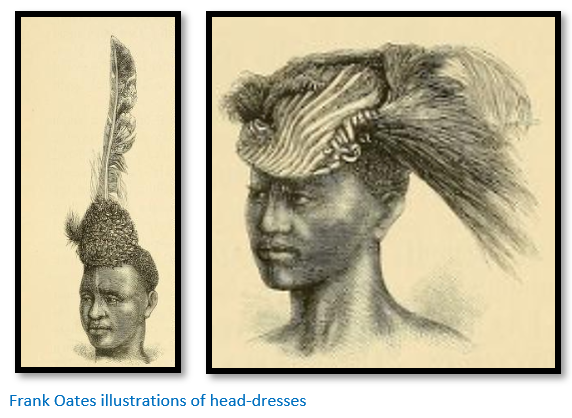

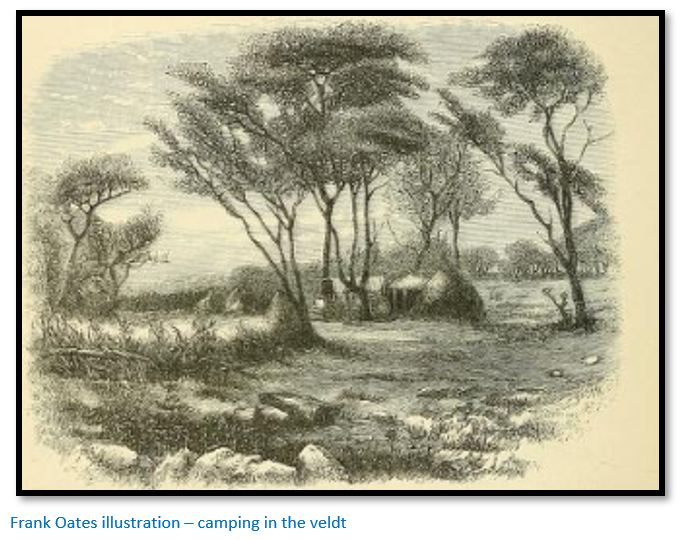

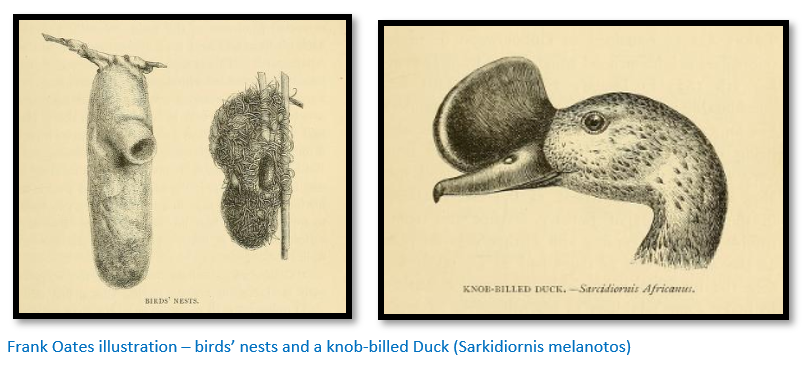

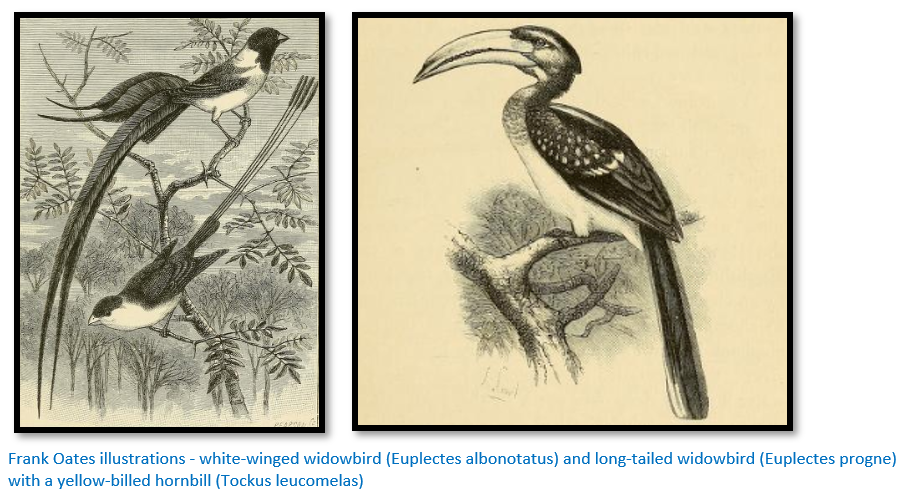

C.G. Oates. Matabeleland and the Victoria Falls; The Diaries and Letters of Frank Oates 1873-75. Kegan Paul & Co, 1881

Dr P. Roberts on the website: http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/cattlefrewen.html

[i] discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk

[ii] Colonel James Henry Bowker (1825 – 1900) was a South African naturalist, archaeologist and soldier and co-authored South African Butterflies (1887 – 9, 3 Vols)

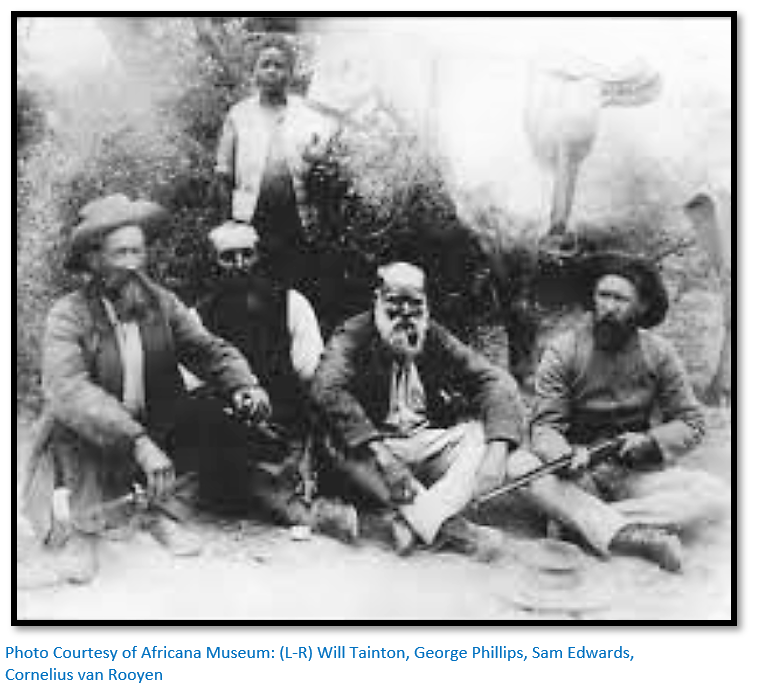

[iii] George Westbeech entered Matabeleland in 1870 with George “Elephant” Phillips and travelled to the Zambezi with Blockley in 1871. He became firm friends with the Barotse King Sipopa and had a trade monopoly until the King’s death in 1877. In 1872 he cut the road from Tati to his trading station at Pandamatenga which was named after him and used by all later travellers to the Victoria Falls. Westbeech knew all the early travellers – Oates, Fairbairn, Bradshaw, Selous, Francis, Coillard, Watson and Horn. He became firm friends with Sipopa’s successor Lewanika and was trusted by Lobengula. He employed numerous hunters to shot ivory for him usually on “halves” and assisted many travellers in need; indeed he was respected by all and opened Barotseland to the British and made Pandamatenga a stopping off place for all. He suffered much from malaria and died trekking south and was buried at Vleeschfontein Mission near Rustenberg. “Joros” was widely known and respected and traded over much of north-western Zambia.

[iv] Scherm or shelter of brushwood

[v] George Blockley worked for Westbeech; the others for Frewen

[vi] Pandamatenga

[vii] Benjamin Frederick Bradshaw, a ship’s doctor left the diamond fields in 1872 and worked for Westbeech until his death in 1883. He was well-known as a good cook and doctor and naturalist.

[viii] Sell, a young German trader who hunted elephant around Dett in 1877 and looked after Hal Barber after he was gored by a buffalo and hunted with Miller and Selous on “halves” in 1879.

[ix][ix][ix] To His Excellency Sir Bartle Frere,

Governor and High Commissioner of Cape Colony

Panda and Tenka, Zambesi,

Tuesday, September 18, 1877

Sir,

We, the undersigned traders, hunters and Europeans in the Zambesi country, think it our duty to inform your Excellency of the way trade has been stopped and Europeans, whether hunting or trading or merely travelling through the country have been waylaid and robbed by the Matabele who declare themselves to be sent by the King.

We state two cases for your Excellency’s information to show how all Europeans have been treated. A trader (well-known in the Matabele country for over ten years) named Byles coming in from Gubulawayo with permission from Lo Bengula to trade and hunt in the veldt was stopped by the Matabele and robbed of five guns, more than 30 of his servants being driven away at the same time.

Another case: Mr Scott travelling up simply to see the country and the Victoria Falls had his waggon robbed of five breech-loading guns in his presence by the same Matabele.

We feel sure, knowing the interest that your Excellency has always taken in African affairs, you will consider our grievances, things never having arrived at such a state before: as in the event of no notice being taken of the above outrages, all Europeans will be compelled to leave this country as life and property will no longer be safe.

Europeans who are best acquainted with Lo Bengula are well aware of the great moral influence your Excellency possesses at Gubulawayo and we feel sure you will use the same on our behalf.

Signed Henry Hall and 25 others.

[x] Henry Byles was hunting in Matabeleland with Zietsman and Meyer in 1868 when elephants were plentiful on the Gwaai river and lived in their wagons near the Mangwe river during the summer rains. Byles accompanied Willie Hartley, Maloney and O’Donnell to Hartley Hills and Manyame river in 1870 where Hartley and O’Donnell died of malaria on 29 May 1870. [See the article The search for Willie Hartley’s grave under Mshonaland West on www.zimfieldguide.com] He accompanied Thomas Baines through Botswana in 1871 and was in Gubulawayo from 1875 – 1877 before taking trade goods to the Zambezi and was back at John Lee’s at Mangwe in early 1878.

[xi] In the mid 1880’s Coillard returned to Zambezi where, thanks to George Westbeech, he founded a successful mission among the Barotse.

[xii] Rider Haggard says two servants; Edward Tabler states seven servants were poisoned

[xiii] Wikipedia. Destruction of Irish country houses (1919–1923)