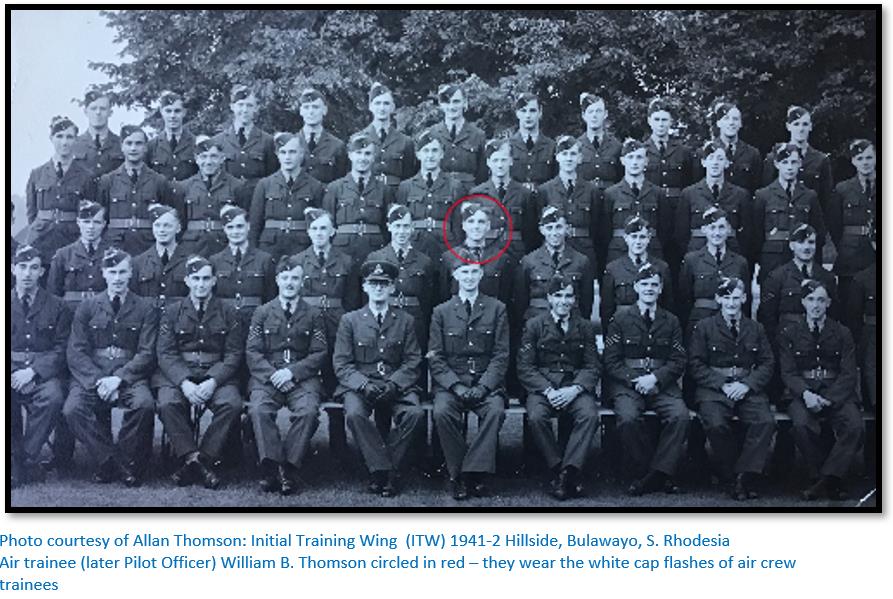

Pilot Officer William (Bill) B Thomson – one of many aircrew who were part of the Rhodesian Air Training Group (RATG) and trained at Bulawayo to fly as Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR)

This article is a tribute to William Thomson and celebrates his connection and all those who served in WWII with the Rhodesian Air Training Scheme (RATG) I have also sourced additional information from the personal stories of Derek Wilkins[i] and Hugh Bone[ii] who also trained under the RATG scheme in Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe)

The RAF desperately needed new pilots and asked the Commonwealth countries for help in turning fledgling air cadets in the RAF and RAF Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR) Greek, Royal Australian and South African air force volunteers into fully qualified bomber and fighter-pilots. Southern Rhodesia was ideal for training with its cloudless days and well away from enemy interference and the country made a major contribution to the war effort.

See also the original article on The Rhodesia Air Training Group (RATG) 1940 – 1945 and statistics on fatalities from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) under Harare on this website.

Initial training

Like thousands of other young men Bill Thomson at the outbreak of war in 1939 or later may have joined the Air Defence Cadet Corps with other young volunteers such as Derek Wilkins and Hugh Bone whose stories I have used to fill in the gaps of Bill’s early life. The Air Training Corps (later called Air Defence Corps) provided a basic training in navigation, meteorology, signals, armament and aircraft recognition.

Entry into the Air Training Corps would have been preceded by a stringent medical and aptitude tests before the successful applicants received call-up papers and instructions to report to a designated Air Crew Reception Centre (ACRC) For Derek ACRC was at Lord’s Cricket Ground in London where he was inducted and inoculated along with other hopefuls. Of this ordeal he wrote: “Under the stern eye of WG Grace in the sanctum sanctorum, the Long Room, my lower regions were closely inspected for ghastly diseases” and presumably Bill followed a similar ordeal.

For Derek there followed three months at Initial Training Wing (ITW) at Newquay of Pilot/Navigator/Bomber (PNB) ground training followed by two months flying DH82A De Havilland Tiger Moth[iii] open-cockpit tandem two-seat biplanes at 26 EFTS (Elementary Flying Training School) Theale in Berkshire, near Reading. This was the point at which one passed or failed for further pilot training and was put into an aircrew category. At this stage Derek had flown 13 hours dual without going solo.

Then as an Aircraftsmen Second Class (AC2C) but known as “air cadets” they passed through the Aircrew Despatch Centre (ACDC) at Heaton Park, Manchester where they were processed for further training in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Canada or the USA.

Hugh was called up at 17 years and on 2 March 1942 reported to the ACRC at Lord’s Cricket Ground at St John’s Wood, London where he was presumably “closely inspected for ghastly diseases.” He writes there was panic stations for new aircrew – their ITW was shortened to 3 weeks before they were sent to Blackpool to wait for a troopship to South Africa. Here they stayed for two weeks in which they were billeted in private houses and the daily routine was route marches and clay pigeon shooting. He writes: “At least, we were supposed to be on route marches. We were in the charge of an air gunner Flight Sergeant who was resting after a tour. After falling into line, we marched away for some hundred yards, when he gave the order “right turn” and found ourselves marching into a cosy café where they were still serving cream cakes after two and a half years of rationing!”

Then they went by train down to Swansea and boarded the troopship HMT Highland Princess.

Troopship to Durban

Cadets were transported from Liverpool in troopships, sometimes escorted in convoys as protection against U-boats or solo if there were no escorts available. Derek says that in an order to confuse the enemy, a sola topee (pith helmet) and tropical kit was issued to those who were Canada-bound and heavy clothing for those destined for Rhodesia and South Africa. This kit must have been quite uncomfortable in the heat of the Red Sea. They sailed in late December 1943 in a convoy of 50 ships, picking up their naval escort north of Ireland

Derek writes aboard the troopship SS Orbita: “Accommodation for 2,000 troops was in 200-man troop decks six decks down, close to the engine room. Hammocks swayed above the mess tables. We were ignorant of our destination. The voyage took six weeks through the Straits of Gibraltar, Port Said, the Red Sea, and Mombasa. Christmas, near my 19th birthday, was off Gibraltar, celebrated with a single small bottle of beer. By Mombasa we had exhausted our stores and broached our emergency rations.”

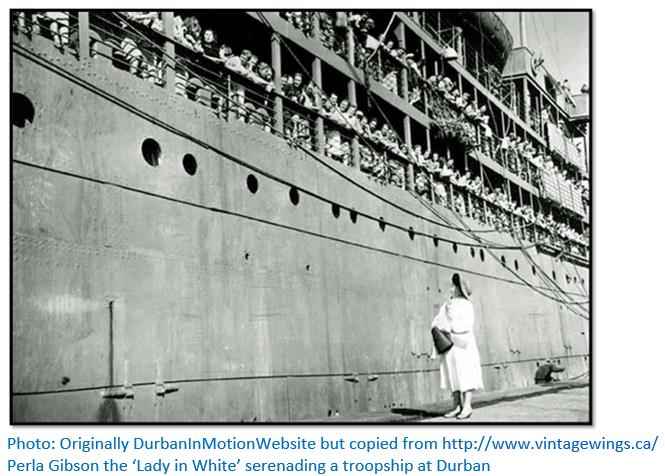

He continues that at Durban they were: “met on the quayside by the singing of 'The Lady in White'. There were lights, not experienced for three years in wartime UK, and unrationed, glorious food. Paradise! We were put up in concrete ex-pigsties at Clairwood Camp and fed Koo jam and bread. Ecstasy! But disastrous for shrunken stomachs.”

Conditions on the sea voyage to South Africa on HMT Highland Princess[iv] for Hugh were as bad. “We were crowded on a below-sea level deck where there were long fixed tables and we were twenty-four to a table, sleeping in hammocks above the table. The latrines were only a few paces beyond our table where the swinging doors wafted the ghastly stench of urine and sickness for at least the first three weeks of our voyage.”

Hugh writes that during the voyage to South Africa he endured the worst conditions of his life. He says breakfast and lunch were inedible. “The only meal worth eating was afternoon tea which consisted of newly baked bread, marmalade and a large mug of tea. There was a canteen where one could have free biscuits, but they had only ginger nuts (a small ginger snap like biscuit). Since they were a favourite of mine, I survived the voyage consuming packet after packet of ginger nuts.”

“Into the Tropics the weather improved and conditions below became a little better. The first excitement was when we sailed into Sierra Leone where some ships in the convoy were taking on cargo. We thought it rather romantic to see the bum boats paddle out to our ship and beg for coins for which they would dive into the water to retrieve. The romance was quickly killed when some men wrapped silver foil around farthings [1/4 of a penny] and threw them to the natives. And the ‘natives,’ on finding the deception, came out with a stream of invective in broad Liverpudlian accents. Seems that many of them had lived half their lives in Liverpool!”

“Rounding the Cape of Good Hope, the convoy was attacked by a U-boat and two ships on the outer side of the convoy were hit. Our destroyer escort dashed to and fro, their sirens whooping, and I ate my bread and marmalade and drank my tea while standing by my assigned lifeboat.”

“That was the end of it and a couple of days later we docked in Durban on the Indian Ocean. As we pulled into the pier in Durban, we were serenaded by Perla Siedle Gibson, the famous ‘Lady in White.’ Gibson, a South African soprano, was at the docks for the arrival and departure of every ship during the war… singing to them all.”[v]

By train to Bulawayo and No 1 Hillside Initial Training Wing (ITW)

The journey by train from Durban to Bulawayo via Bechuanaland (now Botswana) took two days.

Bill’s journey from England in a troopship his experiences would have been the same as his fellow learner-pilots.

Derek writes that here, at last at Hillside, an ITW of the Rhodesian Air Training Group (RATG): “the real business of learning to become a military pilot within the best training scheme in the world in the best place, Southern Rhodesia.”

Initially training at Hillside comprised six weeks of square bashing amid shouts of 'gechur knees brown.' Quite quickly their standard service issue tropical kit was smartened up with a visit to one of Bulawayo’s Indian tailors.

I can find no formation date for No 1 ITW but presumably it was in April 1940 or before, when the first EFTS opened up in Southern Rhodesia. The website www.rafweb.org[vi] states it was an old army camp. I am speculating that it might have been used during the Anglo-Boer War of 1899 – 1902.

Hugh writes: “A great deal of kindness was shown to us by many South African ladies. Ashore for the night in Durban, they had laid on a magnificent feast in the town hall and we returned to our ship laden with fruit. The next day, we were off on a two-day, 1,400 kilometre-long train journey to Bulawayo, Rhodesia - a delight after our five-week-long hellish voyage on Highland Princess.”

Once at Bulawayo, Hugh hoped they could start their Initial Training Wing (ITW—basic training for airmen) in earnest. Only they found out that the urgent signal that had been sent to England was for the immediate delivery of air screws (propellers), not air crew!

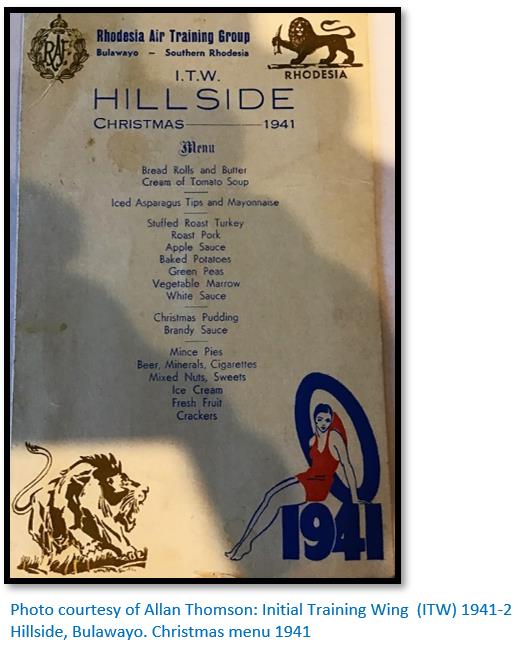

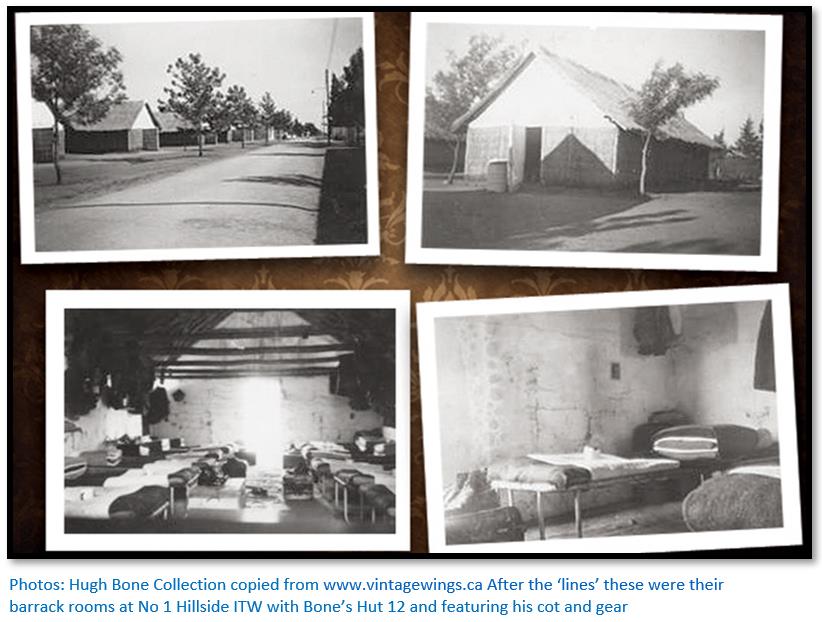

So where to accommodate them? He writes: “The ITW at Hillside had been a cattle market before the war so, there being no huts available, we were quartered in what became known as ‘the lines’ - cattle pens in which we slept for the next two and a half months! But what a revelation was Hillside. After two and a half years of wartime rationing, followed by five weeks of uneatable shipboard meals, the food at ITW was fantastic. Breakfast was “mealie meal,” a porridge of polenta followed by eggs and bacon and if you were still hungry you could have second helpings. At the entrance doors there stood barrels full of oranges, apples and avocados to which you could help yourself. Life in ‘the lines’ was not hard, as the climate was balmy, never a drop of rain while we were there.”

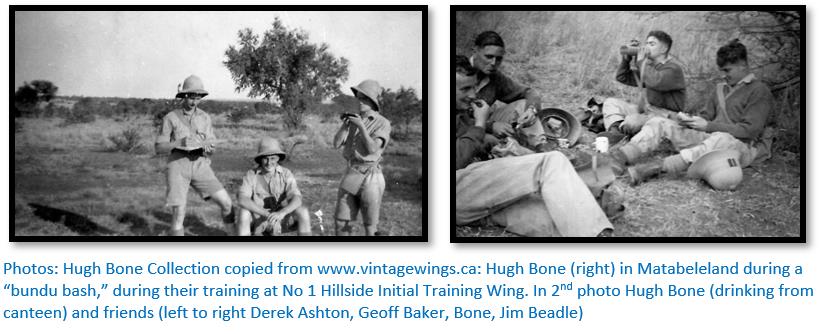

Hugh carried out the same ‘survival training’ as Derek. “To keep us occupied, we were put onto a number of orientation exercises, or ‘bundu bashes’ as we called them. Taken out into the bush in groups of five and given a map and a compass we did triangular courses, increasing in size as we became more accomplished. This was all quite educational as we got to know the bush and often ran into a native kraal and saw Rhodesia as it had been before the colonial townships were built. Plus wildlife which consisted mainly of baboons though we twice saw a green mamba which was somewhat of a scare.”[vii]

“The first Sunday at Hillside I went into Bulawayo to attend the Methodist church, having been raised in a Methodist household and I was immediately taken up by a couple of families and from then on, my every weekend was spent with the Hardy and the Kerr families who have been lifelong friends ever since…. The Kerr’s lived in Hillside and most Saturdays the two families met up and we with a couple of other RAF fellows spent so many happy days together.” Many of the learner-pilots made firm friends with Bulawayo residents and were so taken with the Rhodesian style of life that they returned to settle after the war.

Eventually Hugh’s group moved from the ‘lines’ into huts and started their ITW training which at that time lasted ten weeks before those that passed would expect to move on to an Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS)

Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS)

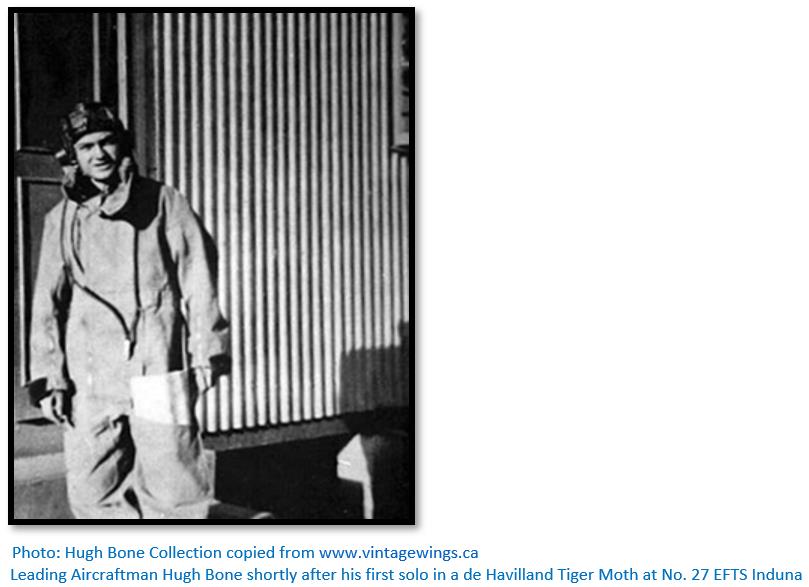

After passing out at Hillside Camp Bill most probably went for his EFTS at No 27 Induna, often called Ntabazinduna.

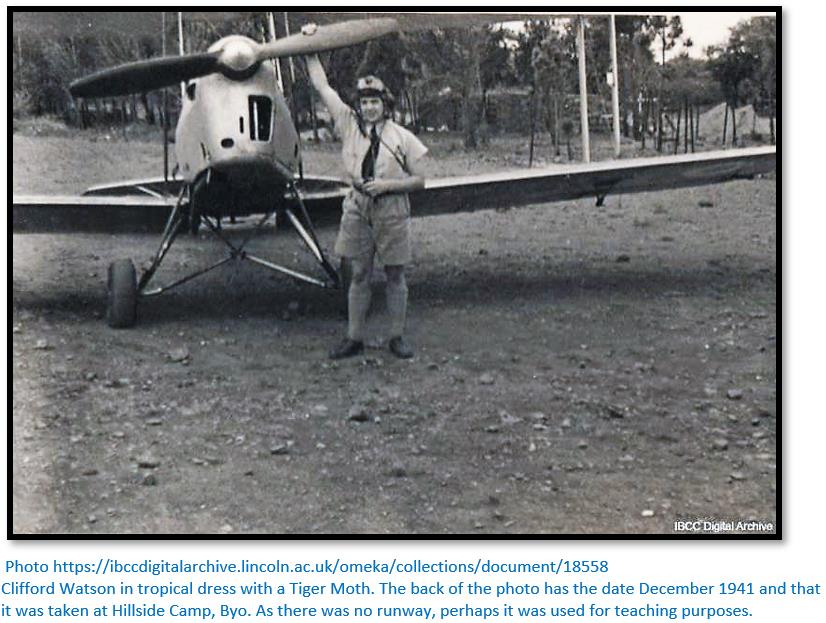

Having successfully completed ITW Derek was next posted to No 27 Ntabazinduna EFTS (then called N'Thabusinduna) an air station with a grass airfield that flew De Havilland Tiger Moth DH82A’s and US Fairchild Cornell PT26’s[viii] a few kilometres north-east of Bulawayo.

Training included cross countries, instrument flying under the hood and night flying using goose-neck flares. Derek flew solo after 8½ hours and by the end of the EFTS course had logged 118 hours. Many aspiring pilots failed to make the grade as pilots and were then presumably trained as navigators or bomb-aimers

In those days the flat landscape around Bulawayo had few distinctive landmarks, so good dead reckoning navigation was vital without radio. Any visible wildlife spotted in the veldt was shamelessly buzzed and crews did get disorientated and lost, sometimes with fatal consequences. Survival training was taken seriously.

Hugh writes that only four from their course of forty received an immediate posting and he was one of the lucky ones to be posted to Induna air station, an EFTS only short distance outside Bulawayo and so continued his friendship with the Rhodesian families. He says there was an old man who they knew as “Binker” Grieg who had the largest chicken farm in Rhodesia. On his land he had built a small, fully-equipped bungalow which was for the use of any RAF learner-crew that wished to use it and it was where I spent all my weekends during my thirteen months training in Rhodesia.

Hugh says: “It was truly a wonderful time. I had achieved my boyhood ambition to learn to fly and despite all the state of the art aircraft that I was later to fly there was nothing so exhilarating as flying in the open cockpit of a Tiger Moth in the balmy Rhodesian conditions. Looping, rolling, and stalling high in the Rhodesian sunshine, ‘low’ flying over the tops of the few fleecy white clouds, all this from Monday to Friday and then off to my dear ‘family’ at the weekend. So it went on until the course ended and a posting to Service Flying Training School (SFTS)”

Service Flying Training School (SFTS)

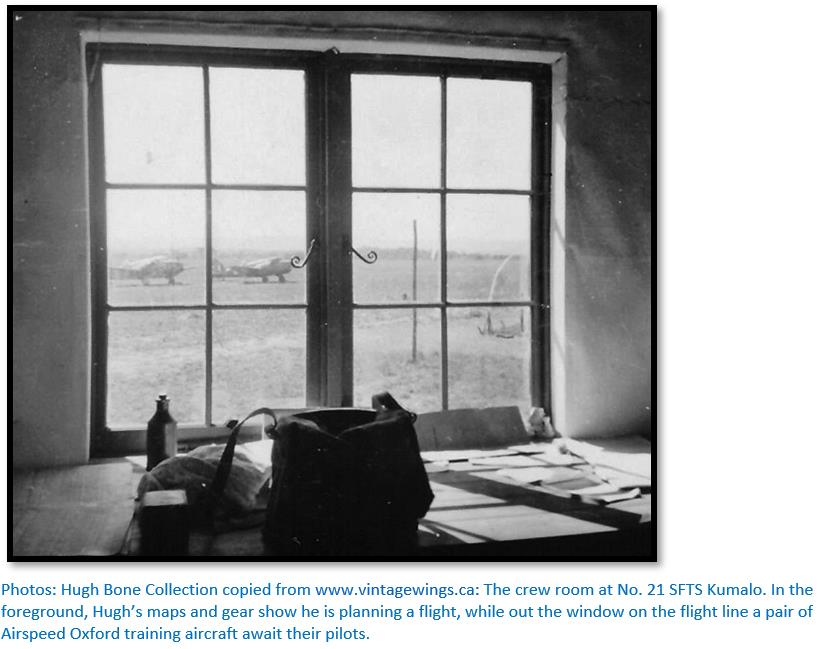

On successful completion of the EFTS course Derek progressed to No 21 SFTS at Kumalo air station, Bulawayo which had a single concrete runway where the learner-pilots flew Airspeed Oxford’s,[ix] a twin Cheetah engined aircraft,[x] a military derivative of the Courier, and the North American AT6A Harvard.[xi] Some flying was done from the nearby satellite emergency airfield at Woollandale and the learner-pilots were introduced to the technicalities of low and high-level bombing that was practiced at the Miasi and Mielbo bombing ranges. Derek writes the bombing ranges were “named so in the African tradition” but I would say that “not knowing my arse from my elbow” was a very English expression!

Hugh recalls that: “One guest at the Hardy’s was a Warrant Officer ‘Jacko’ Jackson who was an instructor at the SFTS at Kumalo and I had got to know him as a friend and he said to leave to leave it [my SFTS posting] with him. Eventually, I found myself posted to Kumalo and who was to be my instructor, but Jacko!”

He continues: “So I learned to fly the Airspeed Oxford[xii] in the company of a friend and was now stationed only three miles outside Bulawayo and even closer to my families. Dear Mrs. Kerr, she was a wonderful person and I regarded her as a second and very dear mother. One of her daughters, Peggy, married a Dane and moved to Denmark and Gunvor, my wife, and I visited Peggy a couple of times while she spent a couple of holidays with us in England. As did Mrs. Kerr, that wonderful bond that dated from my training years continued until Mrs. Kerr died and Peggy moved to Australia. I had so much to be thankful for, having been posted to Rhodesia. Discipline was loose, we had been issued with tropical kit that would have looked ancient on trader Horn and the first thing we did was to buy ourselves natty bush jackets and short shorts! It was a very friendly Air Force out there in Rhodesia and I can honestly say it was the happiest year of my young life by far."

Bill was posted to No 23 Heany air station where he also trained on the Airspeed Oxfords, gaining his wings from the SFTS in September or October 1942. His notes indicate that at least two of his learner-pilot colleagues were killed in air training accidents.

Awarded Wings

After 300 hours of flying training Derek received his flying badge (wings) a commission and an offer to remain in Southern Rhodesia as an instructor, which he declined in favour of going on an Operational training Unit (OTU)

After finishing his flight training syllabus, Hugh and his fellow learner-pilots did not immediately receive their wings, like Derek, although they had completed the flying syllabus and additional advanced courses in bomb aiming and air navigation. Much time was spent carrying out low and high level bombing at the Miasi and Mielbo ranges: “After we had done 80 hours on the Oxford and passed our classroom studies we were eligible for our wings but in Rhodesia we had yet another 80 hours of training. Now we were coupled with another pilot and one day he would pilot the aircraft while I did a navigational exercise or acted as bomb aimer and we took it in turns throughout the rest of the course. Then we had to do two weeks under canvas out in the bush[xiii] and finally we went on an exercise bombing mission to be intercepted by Harvards from the SFTS near Salisbury. And finally we were awarded our wings on June 2nd, 1943.”

Just before end of his course Hugh was given seven days leave and with a couple of fellow aircrew took the train to Victoria Falls. “What a wonderful experience that was. We stayed in the Falls hotel and even though the falls were a couple of miles distant one could hear the constant thunder of the falling water and could see the mist of spray that indicated their presence.”

Having been awarded his wings, all of his: “Rhodesian friends were at the station to wave me a tearful farewell as I started my journey to South Africa.”

Bulawayo

All the learner-pilots wrote that the citizens of Bulawayo were incredibly hospitable and provided them with much appreciated social outings. At the end of their course Derek’s unit staged a squadron flypast over Bulawayo to thank them for their welcome and kindness.

Life post RATG for these young, qualified pilots

Hugh writes that the routine was:

- One flying course move to Kenya to do an OTU (Operation Training Unit) before joining a squadron in the Middle East

- The second course moved straight home to England

- The third course would do a three month General Reconnaissance (GR) course at No. 61 Air School in the small city of George, South Africa, in preparation for joining the RAF’s Coastal Command.

Hugh Bone is posted on the Maritime Reconnaissance Course at No 61 Air School (SAAF) at George in the Western Cape, South Africa

He writes: “Those three months at George I would prefer to forget. Many of the Afrikaners were openly hostile towards Brits and George, we learned, was a hotbed for the OB’s, the Ossewabrandwag[xiv] who were violently opposed to being in the war with more sympathy for the Nazis than the Allies. It was a rude awakening, the shock of leaving the easy-going RAF of Rhodesia and the lovely friends I had made, to the reality of a hostile environment. Most of our instructors were South Africans and there were a number of Afrikaner pilots on the course, most of whom were unfriendly to say the least. Only one was pleasant so his name still stands out in my mind—Prinsloo…

There was a very pleasant weekend retreat on the coast called the Wilderness but, though we were taken to see it, none dared risk staying for the weekend. It was a very miserable and dull three months emphasized by comparison to Rhodesia. Even the flying was boring—flying as a navigator over nothing but sea and trying to navigate over a triangular course by instruments. Most quite useless, having to learn the use of a sextant for instance. Masses of aircraft and ship recognition—British, American, Italian and German. The final insult was when we sat our final exams. One was assessed by the percentage of marks compared to that of the overall average of the course. The Afrikaners on the course were given the answers to all the questions by the Afrikaner instructors. So I achieved an average of 88.5% while the course average was 90. 2% and in large writing my logbook reads “Results below average”. Even though it was the same for every one of the RAF pilots on the course, which has still rankled in my mind. No, it was a most unpleasant three months, that GR course…

The course completed in unsatisfactory fashion, we were shunted off to Capetown to await a ship. We were in a camp at the town of Retreat which was a few miles down the coast from Capetown and while it was quite safe to visit the city we were strongly advised to return to camp in groups. The camp was some distance from the rail connection and there was again the danger of OB’s. I was in a room with two other air crew plus a Polish pilot. The drill was to visit Capetown but wait at Retreat until there were sufficient men to make a safe group to walk to the camp. One night the Pole didn’t return and we learned the next day that he had tried to walk from the train alone and had been murdered. It was with some relief that we were assigned to a ship after two weeks at Retreat. Gossip was rife and the latest was that RMS Queen Mary was in dock and would be taking us home. There was only myself and my friend Derek Aston from Aircrew Reception Centre days and we were more than disappointed to find ourselves boarding HMT Highland Chieftain,[xv] the sister ship of the slave galley on which we had arrived in South Africa.”

After a week on board they were told the ship was diverting to Buenos Aires to pick up a cargo of beef, but as Argentina was pro-Nazi, they were put ashore in Montevideo, Uruguay. The citizens of the town really treated them well and they enjoyed the luxury of staying at the Miramar Hotel and were the centre of attention among the Uruguayans. Hugh writes: “Such lovely people all. Prior to our arrival, we had no wish to delay our return home by visiting Montevideo. Now, after two wonderful weeks, we didn’t want to leave, especially me. I could have stayed on forever!”

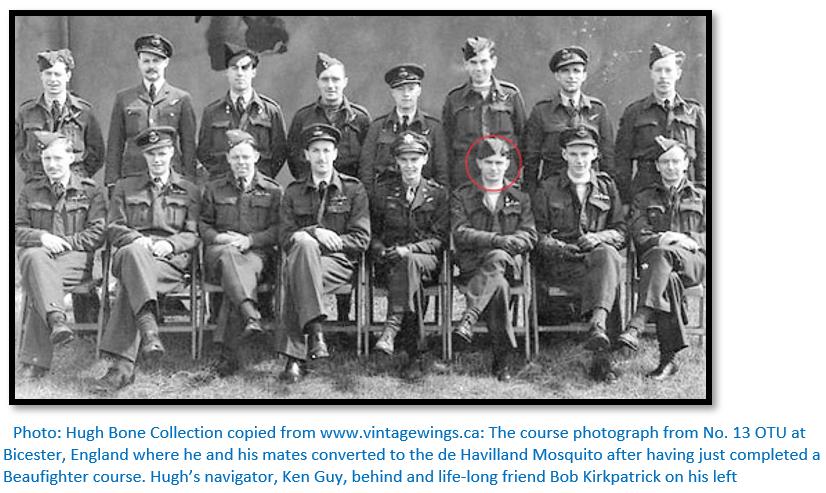

Back in England by October 1943, I had expected to do an OTU course and join a squadron post-haste, but it was not to be. He was posted to RAF Harrogate, where he kicked his heels for 4 months. Then to RAF Fraserburgh where he did an advanced course on Airspeed Oxfords! In April 1944 he was posted—to RAF Crosby-on-Eden to do a Beaufighter OTU. Then finally to No 13 RAF Bicester to do Mosquito OTU.

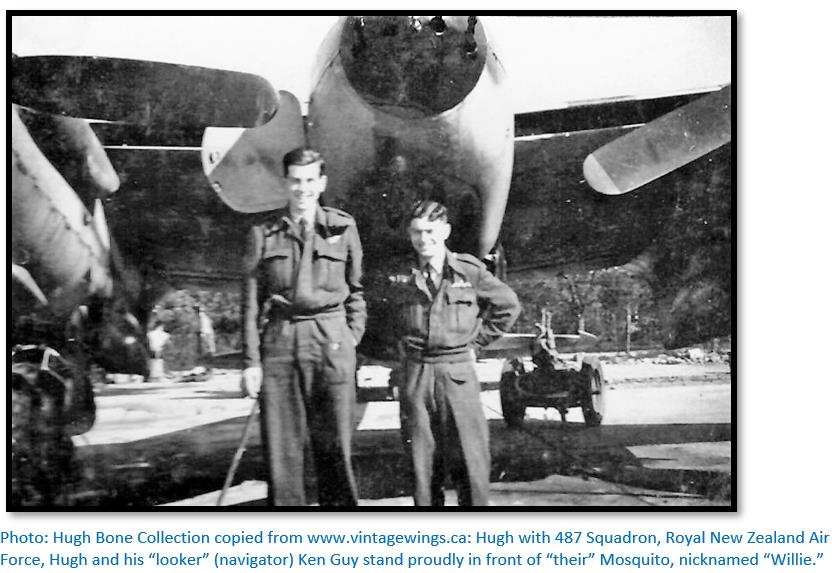

Hugh wrote: “I have always been very proud and grateful that I served on 487, a Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) squadron. The Kiwis were great lads and I consider myself very fortunate to have had one of the best flight commander’s in Bill Kemp DSO and bar, DFC and bar and over the course of my time with 487, he became more of a friend than a superior officer…”

Their missions: “meant operating immediately behind the “bomb” line, the line separating the opposing forces, where we would search for any troop or transport movement and attack it with bombs and cannon and machine gun fire. The Mark 6 Mosquito was armed with six machine guns and six 20mm cannons, as well as carrying a bomb load of four 500lb bombs. As we would often be operating over occupied territory we must not be indiscriminate in our attacks. If we could find no troop movement then we should drop our bombs on bridges or rail junctions and if visibility was too bad then we should bring our bombs back unless we were over Germany. Operational height was usually 1,500 to 2,000 ft, which was the best height to make observations. On returning to base, a truck would take us to the interrogation room to be debriefed by an Intelligence Officer. We’d be given a couple of days to settle in and do some local flying to acquaint ourselves with the local landscape, after which we should be ready to start operating.”

Derek Wilkins is also posted on the Maritime Reconnaissance Course at No 61 Air School (SAAF) at George in the Western Cape, South Africa

The newly-qualified pilots flew Avro Anson’s a British-built, twin engined, multi role aircraft that served in large numbers in the Royal Air Force and Fleet Air Arm. The course concentrated on sea navigation using dead reckoning and astro-navigation with their operational area between Cape Town and Port Elizabeth. All shipping was logged and photographed and a sharp lookout was kept for U-boats heading for the Indian Ocean. Ship and aircraft recognition was mainly of the Japanese navy and air force but after graduation in April 1945 they were flown to the Middle East from Durban in a Short 'C' Class Empire flying boat via neutral Mozambique!

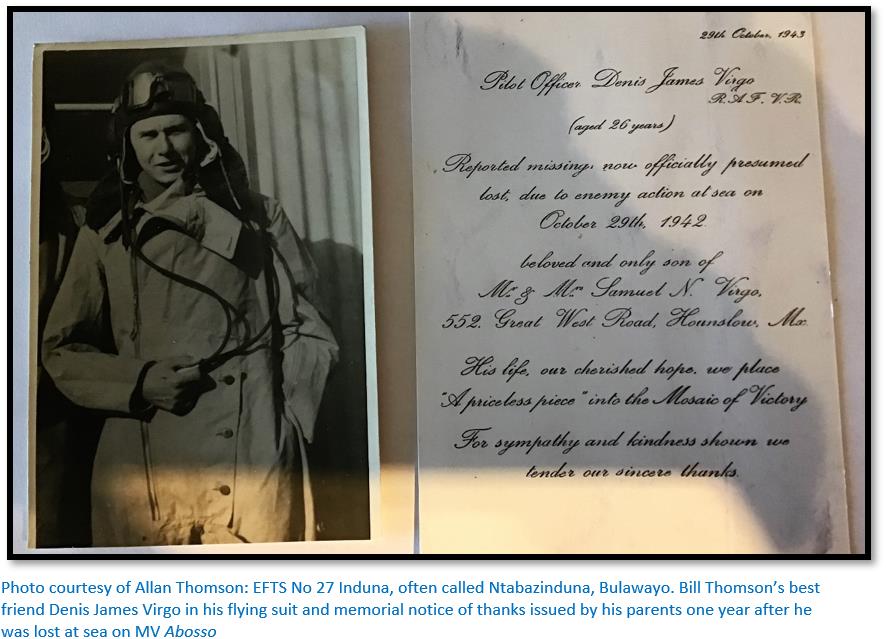

Bill Thomson takes the RMS Abosso to England, but the ship is sunk by a U Boat in the Atlantic

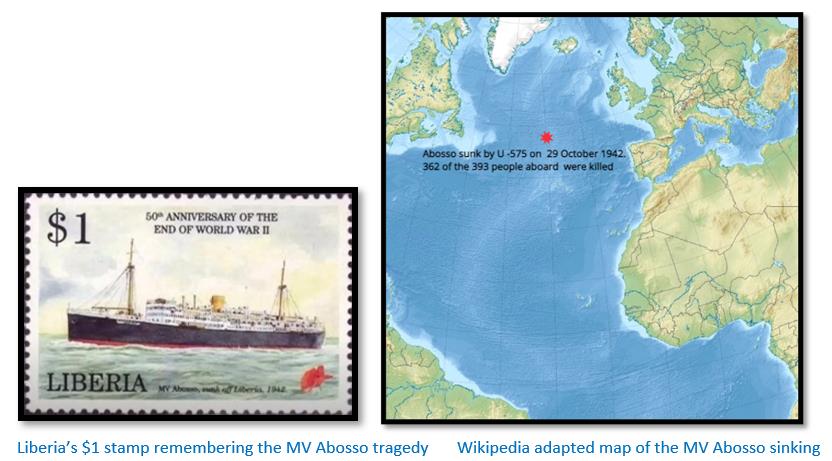

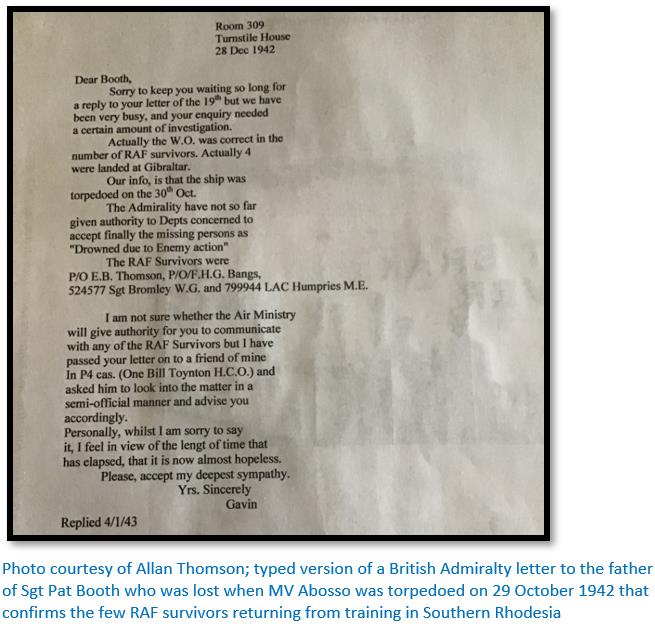

Bill’s son Allan writes: “On the night of 29 October 1942 while returning to the UK on the RMS Abosso, the ship was attacked and sunk by the submarine U-575. There were 45 graduates from his STFS or ETFS on board. Only my father and one other pilot is believed to have survived, having by good fortune boarded the only one of 12 lifeboats which was found. Almost the entire class was wiped out.”

Wikipedia carries a comprehensive article on the sinking of MV Abosso. Pre-war she was the flagship of the Elder Dempster Lines carrying passengers, mail and cargo. In WWII she was converted to a troopship and Defensively Equipped Merchant Ship carrying 20 DEMS gunners and sailing between the UK, West Africa and South Africa.

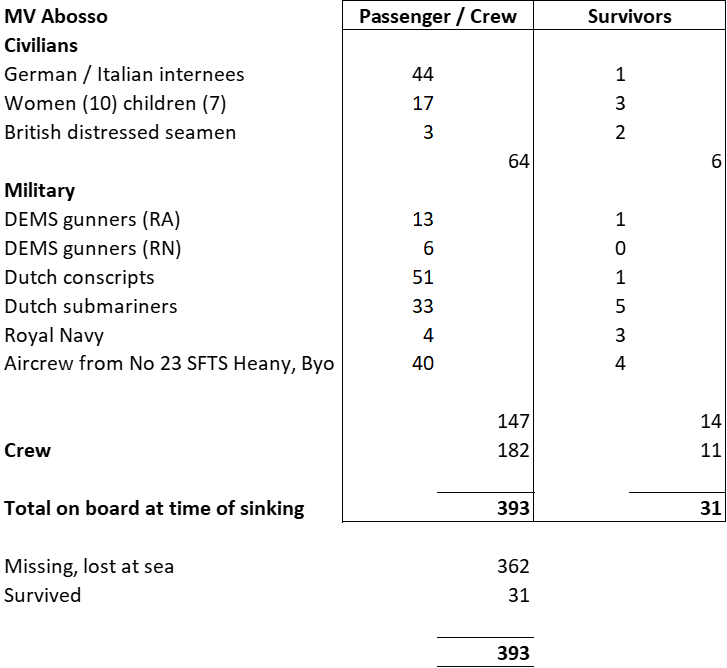

On 8 October 1942 Abosso left Cape Town for Liverpool with 400 bags of mail and 3,000 tons of wool. Her complement of civilian and military passengers and crew is listed below. She sailed alone and unescorted, despite having a top speed of only 14.5 knots (26.9 km/h) On Thursday 29 October at 2213 hrs when she was over 1,000 miles north of the Azores (see above map) she was torpedoed by the German submarine U-575. The ship's engines stopped, all her lights failed, and she started to list heavily to port. As she settled in the water, the ship temporarily righted herself, her crew got her emergency generator working and her floodlights were switched on to help the evacuation. Almost immediately, U-575 fired another torpedo from one of her stern torpedo tubes, which hit Abosso at 2228 hrs forward of her bridge. At 2305 hrs the ship sank bow first.

Although the Abosso had 12 lifeboats it is unclear if any on the port side were launched. On the starboard side No 3 was launched with most of the Dutch submariners, but the lifeboat fell and all the occupants were thrown into the water. No 5 and No 9 lifeboats were both launched successfully and collected some of the Dutch swimmers. U-575 then surfaced and scanned the area with her searchlights, but no attempt was made to speak to or rescue the survivors. Kapitanleutenant Gunther Heydemann reported 10 lifeboats and 15 – 20 life rafts afloat and occupied.

No 5 lifeboat, which included Bill Thomson soon lost sight of the other lifeboats and life rafts in the dark. Their lifeboat leaked badly and they used their seaboots and empty cans to bail her out. Next day they raised the mast and hoisted the sail to keep the lifeboat into the wind. At daybreak on 31 October after 30 hours they spotted Convoy KMS-2 sailing to the Mediterranean for Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of Vichy French North Africa. HMS Bideford, a convoy escort, received permission to stop and pick up the 31 survivors.

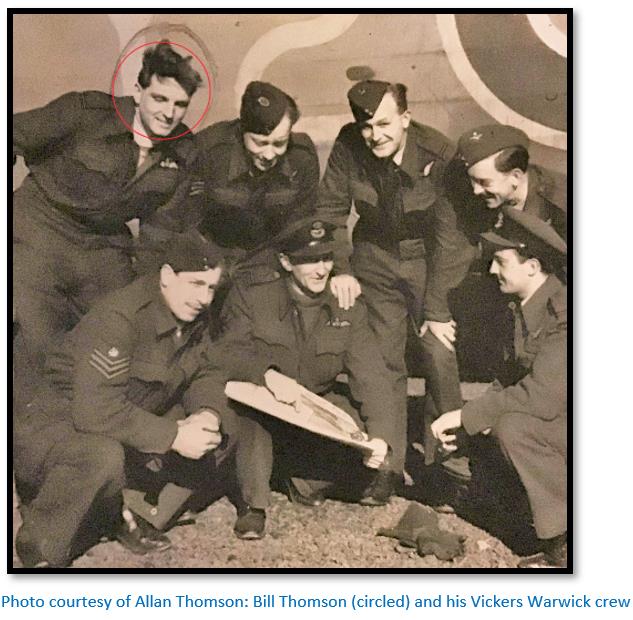

Bill Thomson’s later career

On arriving back in the UK, Bill was assigned to fly with Coastal Command protecting the convoys from U-boat attacks in the battle of the Atlantic and Allied shipping from Luftwaffe threats. In the last years of WWII he flew the Vickers Warwick, a multi-purpose, twin-engined aircraft on air-sea rescue missions. The Mark V was armed with 7 machine guns and could carry 6,000 pounds (2,700 kg) of bombs, mines or depth charges and a Leigh light was fitted ventrally.

After the war in 1951 he went back to Bulawayo where he worked as a civil engineer, returning to the UK in 1954-5. Africa lured him back several times, teaching in Swaziland and Lesotho in the 1970’s and then onto Nigeria in the 1980’s. He married Janet in 1948, Allan was born in Scotland in 1949, Ann was born in Bulawayo in 1953, Ian was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, in 1957 after the family moved to Canada in 1956. Allan says Bill never spoke about his war years, but near the end of his life he wrote notes beside the photos in his album. His family thought he suffered from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) like so many of his generation, but it was never discussed or treated.

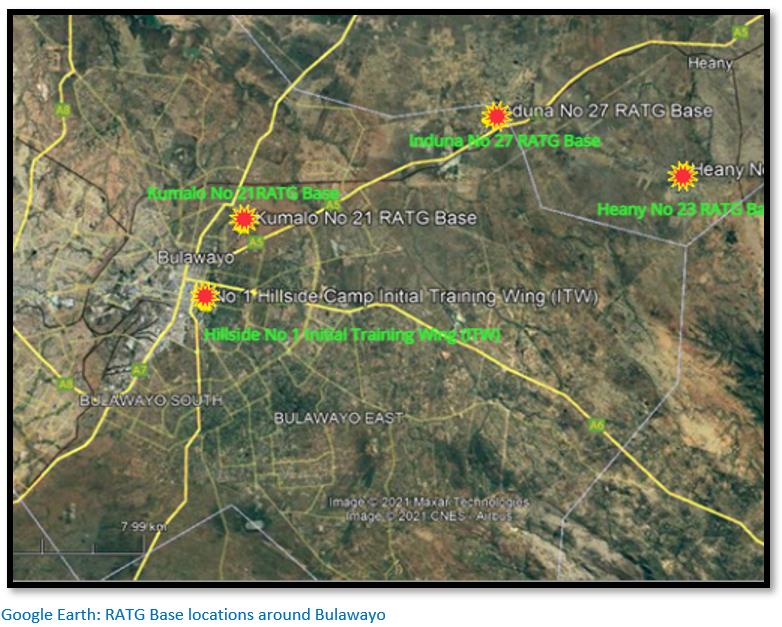

Location of the RATG Bases at Bulawayo

GPS locations were kindly given by John Austin-Williams

Hillside No 1 Initial Training Wing (ITW) 20⁰10′04.7″S 28⁰35′17.4″E

Heany No 23 RATG Base 20⁰07′45.2″S 28⁰46′09.7″E

Induna No 27 RATG Base 20⁰06′18.3″S 28⁰41′51.8″E

Kumalo No 21 RATG Base 20⁰08′24.6″S 28⁰36′11.5″E

References

Allan Thomson. Photographs and recollections of his father William B. Thomson

RAF Training in Southern Africa by Derek Wilkins in WW2 People’s War: An Archive of World War Two Memories from https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/37/a1122337.shtml

John Austin-Williams. Rhodesian Air Training Group (RATG) bases

Notes

[i] RAF Training in Southern Africa by Derek Wilkins in WW2 People’s War: An Archive of World War Two Memories from https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/37/a1122337.shtml

[iii] The De Havilland DH82A Tiger Moth first flew in 1931 and was the probably the best known training plane ever flown by almost all wartime pilots. More than 9,000 Tiger Moths were built. They were powered by a 130 HP de Havilland Gipsy Major I engine with an all-up weight of 1,825 lb (828 kg) Their max speed was 104 mph (167 kph) a ceiling height of 14,000 ft (4,267 m) and a cruising range of 300 miles (483 km) All information from https://www.dehavillandmuseum.co.uk/aircraft/de-havilland-dh82a-tiger-moth/

[iv] His Majesty’s Troopship (HMT) Highland Princess was a 14,000-ton passenger / cargo vessel built in 1929 in Belfast for the Nelson Line but reflagged to the Royal Mail Line by WWII. She survived the war and was broken up in the 1960s

[v] Wikipedia states Perla Siedle Gibson, a South African soprano and artist, greeted servicemen and women at the dockside in Durban, South Africa. Wearing her signature white dress and red hat, she became internationally celebrated during the Second World War as the ‘Lady in White.’ She sang ‘There'll Always be an England’ and ‘Land of Hope and Glory’ to more than 5,000 ships entering or leaving the harbour, amounting to about a quarter million men and women. She even sang on the day she learned that her son Roy had been killed in combat in Italy. She sang through a hand-held megaphone given to her by men from one of the ships. She died in 1971, shortly before her 83rd birthday. A year later a bronze plaque donated by men of the Royal Navy was erected to her memory on Durban's North Pier on the spot where she used to sing. In 1995, Queen Elizabeth II unveiled a statue in her honour in Durban harbour, which has subsequently been moved to the Port Natal / Durban Maritime Museum

[vii] Probably Hugh has confused the green mamba (Dendroaspis angusticeps) with the boomslang (Dispholidus typus) or green bush snakes of the genus Philothamnus. . Green mambas live along the coastlines of Southern Africa and East Africa where they favour coastal bush, dune and montane forest. They probably do live in Zimbabwe’s eastern montane forest area, but not in the flat, open and dry region of Matabeleland.

[viii] The Fairchild PT-26 was a primary trainer introduced in 1939 and designed to replace the biplane trainers then in use. The single, low-winged Cornell more accurately reflected the front-line fighters such as Spitfires and Hurricane’s that many cadets undergoing single-engine fighter training they would later be tasked to fly in combat. The PT-19 was the basic version of the Cornell succeeded by the PT-23 with the same basic airframe and a radial engine fitted. Fairchild (USA) and Fleet (Canada) built over 1,700 PT-26’s. All Information from https://pimaair.org/museum-aircraft/fairchild-pt-26/

[ix] The Airspeed Oxford was a military equivalent of the same company’s Airspeed Envoy airliner. They prototype first flew in 1937 when it became the Royal Air Force’s first twin-engine monoplane advanced trainer. The first Oxford’s had an Armstrong Whitworth dorsal gun turret fitted for gunnery training that was removed from later versions when they were used mainly for pilot training. In addition to training they were used as air ambulances, communications aircraft and for ground radar calibration duties.

It saw widespread use as an advanced trainer in the United Kingdom, Canada, Southern Rhodesia, Australia, New Zealand and the Middle East.

[x] The Armstrong Siddeley Cheetah was a pre-war British military aircraft and developed into the Avro Anson bomber which in 1935 was Britain’s first twin-engineered aircraft with retractable undercarriage. All information from https://www.aarg.com.au/armstrong-siddeley-cheetah.html

[xi] The Harvard AT6A was manufactured by North American Aviation as a trainer aircraft and first flew in 1935. Over 15,000 were built for the US Army Air Force and Navy, Royal Air Force and South African Air Force

[xii] The Airspeed Oxford were affectionately known to their aircrews as the ‘Oxbox.’ The Airspeed Oxford Mark I was a bombing and gunnery trainer and featured a dorsal Armstrong-Whitworth turret—the only Oxford to do so.”

[xiii] They camped in the bush under canvas at a relief landing ground called Marony

[xiv] Wikipedia entry notes the Ossewabrandwag (OB) from Afrikaans: ossewa, lit. 'ox-wagon' and Afrikaans: brandwag, lit. 'guard, picket, sentinel, sentry' - Ox-wagon Sentinel) was an anti-British and pro-German organisation in South Africa during World War II, which opposed South African participation in the war. Pro-German Afrikaaners formed the Ossewabrandwag in Bloemfontein on 4 February 1939.

[xv] His Majesty’s Troopship HMT Highland Chieftain was identical to HMT Highland Princess. Like her sistership she was built in 1929 in Befast for the Nelson Line but reflagged to the Royal Mail Line in 1932. She commenced wartime trooping duties in 1939, but was damaged on the 11th of October 1940, during a bombing raid on Liverpool. She was sold in 1959 to the Calpe Shipping Company of Gibraltar and used in the whaling industry under the name Calpean Star. She suffered rudder damage off Montevideo in 1965, followed by a boiler room explosion and sank in the River Plate estuary.