Matabele Thompson; his role in the Rudd Concession

Introduction

Thompson’s parents[1] came to South Africa in 1850, Francis Robert ‘Matabele’ Thompson, one of three sons and two daughters and the subject of this article was born in 1857. His father, Francis Thompson, had inherited £7,000 and his son writes that he came to “make his name as a hunter of big game.” They landed at Port Natal and headed inward to the new settlement of Pietermaritzburg, where Ann, his mother was to stay while Francis snr. ventured into the interior where on his early trips he met Dr and Mrs Robert Moffat at Kuruman and David Livingstone on the Zambesi river. However, hunting was quite soon swopped for trading from Port Elizabeth (now Gqeberha)

Probably ‘Matabele’ Thompson’s greatest achievement was being one of the party of three who visited Lobengula, King of the Matabele (amaNdebele) and obtained the Rudd Concession on 30 October 1888 despite the total opposition of the established traders in Bulawayo and other concession seeking parties. One of the main motivations in persuading Lobengula to agree to the Rudd Concession was the threat of Portuguese expansion from the east as they were already active in gold mining at Penhalonga in the future Manicaland and had traded for gold through their Feira’s and the annual trading expedition of their Vashambadzi[2] to the Mazowe and Angwa rivers since the sixteenth century.

The Rudd party, appointed by Cecil Rhodes became part of the British effort to acquire Zambezia, the region between the Limpopo and the Zambesi rivers. However, Lord Salisbury, the Prime Minister at the time required Rhodes to legitimise his claim first by obtaining a mining concession from Lobengula, the amaNdebele King. Thus the acquisition of the Rudd Concession became a necessary part of Rhodes’ plan to occupy Mashonaland, a region recognised at the time as being tributary to Lobengula. The Rudd Concession was different in that it was not a treaty between sovereign states but a concession granted to the British South Africa Company controlled by Rhodes.

Thompson had already known Rhodes for several years and as the only one of the three in the party who spoke isiNdebele, the language spoken by Lobengula, became a key appointee in obtaining the Rudd Concession.[3]

Despite Ivon Fry’s criticism[4] of Thompson as one of Rhodes’ ‘jackals,’ his role, especially in the light of Lobengula’s and the amaNdebele Indunas misgivings sparked by the other concession seekers bitterness at losing out on the concession, was extremely difficult and he endured extreme hostility. Indeed Lotshe, the Induna who supported the Rudd Concession was made a scapegoat and murdered.

As Thompson died in May 1927, nearly forty years after the granting of the Rudd Concession, it is hardly surprising that some the daily detail in his autobiography had become blurred and Thompson himself writes of Rhodes: “no man knew or loved him better than I did, and there could have been few to whom he spoke more openly.”[5] In addition his daughter ‘had to piece together much from his notes and memoranda’ and understandably would throw a positive light on his efforts.

As neither Charles Rudd nor Rochfort Maguire wrote accounts of the events at the time, Thompson’s first-hand account of the events surrounding the Rudd Concession assumes great importance and much of this article is written directly from his book, rather than rephrasing.

Early days

Thompson says as a young lad in Port Elizabeth he learnt Dutch and a number of native languages including isiNdebele. He went to school at Grey’s[6] but in 1870 it was decided the family would move to the newly discovered diamond fields and live at Klipdrift, now Barkly West in Griqualand West and from then his mother encouraged him to self-study. Aged thirteen, he became a diamond digger.

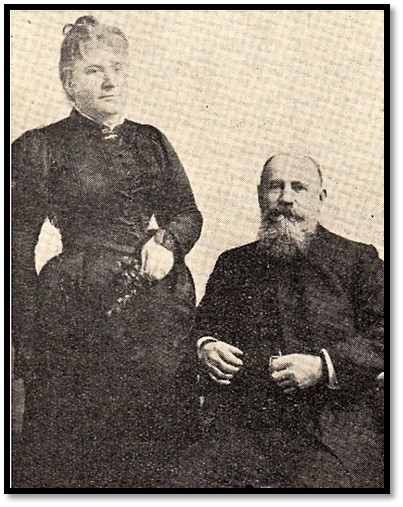

Francis and Ann Thompson, the parents of ‘Matabele’ Thompson soon after their marriage in 1850

He writes that life on the diamond fields was hard; his native helper and he worked from sunrise to sunset with only mealie meal and a little tea and coffee.[7] When he failed to find enough stones to pay his way, he joined a trading firm, and found himself in Bechuanaland (now Botswana) bartering for ivory and ostrich feathers with native hunters and improving his language skills and his financial status.

In 1873 his father was appointed one of the eight Legislative Councillors for Griqualand West as the discovery of diamonds and the influx of diggers meant the territory needed to be properly administered. On a stay with his parents he learnt that his father had met and invited two young men to supper on Sunday; they were Charles Rudd and his friend Cecil Rhodes. This would be the start of a long friendship.

Cornforth Hill Farm

To settle Griqualand West the British Government offered perpetual leases to those willing to farm the land and in 1874 Thompson bought the first farm on the Hartz river, about fifty miles north from Barkly West, from the money made from trading that he named Cornforth Hill after the family home in Yorkshire. He farmed the property for the next four years and accumulated herds of around three thousand sheep and six hundred cattle.

The ninth and final frontier war – also known as the ‘Fengu-Gcaleka War’ or ‘Ngcayechibi's War’ involved competing powers: the Cape Colony Government and its Fengu allies, the British Empire, and the Xhosa armies (Gcaleka and Ngqika) A series of devastating droughts had started in 1875 in Gcalekaland and became the most severe drought ever recorded. It caused political tensions among the Xhosa; particularly the Mfengu, the Thembu and the Gcaleka. A wedding celebration at Headman Ngcayechibi's in September 1877 was the scene of a bar fight when the tensions emerged after the Gcaleka harassed the Fengu in attendance. Later in the same day, Gcaleka attacked a Cape Colony police outpost, which was manned predominantly by a Fengu ethnic police force.

Cornforth Hill, being on the frontier was extremely vulnerable and Thompson’s father became anxious for his son’s safety, as settlers in the neighbourhood had been murdered, and came to the farm on 14 July 1878. Shortly after a neighbour, William Hunter, sent for help as he was being attacked. Thompson, his father and a cousin William, rode over to help, but after wounding Hunter, the natives appeared to have withdrawn and they returned to Cornforth Hill.

Cornforth Hill Homestead

Next night each of the three kept guard in turn until at about 3am Thompson was woken by one of their Koranna farmhands whispering: “Wake up, master, they are attacking and surrounding us.” In fact they turned out to be the second battalion of the 24th Regiment under Captain Brunker[8] that had become lost and found its way to the farm. They had not eaten for 52 hours, but the Thompson’s were able to put that right. The troops left and at dawn on 18 July a farmworker arrived to say they were about to be attacked.

Thompson's father is brutally murdered; Thompson himself barely escaped with his life

The three whites armed themselves and their three Koranna farmworkers and soon saw an estimated group of two hundred mounted natives approaching. Thompson attempted to parley but was fired upon. General firing broke out and after three hours their attackers were within 30 yards when the thatched roof caught fire. With the farm house ablaze they had to run for it and Thompson had only gone a short distance when he was shot on the left side with two broken ribs. He saw mounted men catching up on his cousin and father and shots being fired.[9]

One of the Koranna farmhands was captured, Thompson and the other two ran into a dry riverbed and managed to get about a mile away before they were spotted and the natives came in pursuit. With his wound slowing him, Thompson told the two to run on and crawled into some grass cover before fainting. The enemy soon reached the spot where he was concealed, but they saw the two Koranna farmhands in the distance and took off after them. Then the natives saw a transport wagon laden with goods for a trader and with bated breath Thompson watched them, sixty yards away, galloping down to loot it. The wagon drivers having seen the attack on the homestead had made off into the bush. The natives then moved back to the wrecked and burning homestead and looted the sheep, cattle, wagons and horses.

Badly wounded though he was, Thompson eventually made it to safety at a farm called Spitzkop, some sixteen miles distant from Cornforth Hill. Ronald Spalding and his family were quite unaware of what had happened at Thompson’s farm and there was barely time to roughly dress his wounds as they all set about preparing to defend the house that fortunately had an iron roof; surrounded by a loopholed stone wall six feet high. Thompson’s bed was raised to the level of a loophole at one of the windows and he was armed with a rifle.

Then the same natives who had attacked his homestead were seen approaching about seventeen hundred yards away. A desultory fire was kept up by both sides during the night. Mrs Spalding loaded Thompson’s rifle and he fired whenever a flash from one of the natives’ guns was seen. The long weary night passed and daylight showed they were surrounded, the natives about twelve hundred yards away. The enemy knew the house was fortified and kept up a constant fire but were afraid of approaching too close. Firing from the homestead kept the attackers at bay; but the defenders worried about passing another night of siege.

About midnight Thompson heard the distant sound of a bugle and called Mrs Spalding who told her husband, but he replied, “Don’t encourage Thompson; he is becoming delirious. Keep him up and don’t let him go away, as it will mean one gun less.”[10] They had just three guns. Soon a military force of five hundred troops arrived and the natives retreated.

Four men held him down and a Kimberley doctor, Dr William Murphy carried out an operation; Thompson was kept under morphia sedation for eight days before being taken back to his mother in Barkly West and kept in bed for a further forty days.

Having lost his farm, Thompson was almost penniless, but received a lieutenant's commission in the intelligence department of Colonel Warren’s staff and after the war ended was appointed British Resident and Chief Inspector of Nature Reserves in Griqualand West. He had seventy-five troopers of the Diamond Fields Horse under his command, but instead of using force decided to use his skill with native languages to help persuade the defeated natives to disarm in a general amnesty and twelve hundred guns were handed in.

As the frontier settled down, he was able to move back to Cornforth Hill, and soon it was flourishing again. In 1881 Thompson was visiting his married sister Penelope in Malmesbury, Cape Colony when he met his future wife. On 16 February 1882 he married Georgina Rees, daughter of Colonel Charles Rees, an Imperial surveyor who had come out to South Africa to do some work on the forts at Capetown and Simonstown.[11]

Francis Robert ‘Matabele’ Thompson Georgina Thompson (née Rees)

Boer freebooters establish the Boer Republics of Stellaland and Goshen

Sir Charles Warren had policed Bechuanaland for a few years but gradually his force was withdrawn to cut costs and the natives living there found themselves without protection having being disarmed by the British. However others in the Taungs Reserve had been allowed to keep their arms and soon began to interfere with their unarmed neighbours.

Prior to this there had been many years of hereditary native disputes over chieftainships and tribal rights. Each side invited whites to help and about a thousand Boers under Adrian de la Rey[12] promptly annexed the territories of both chiefs and established the Republics of Stellaland[13] and Goshen[14] (1882 – 3) that united in 1883 with its capital at Vryburg with its own paper money and stamps and a Volksraad with van Niekerk as President. Their territories were close to the Transvaal border and the Boers claimed some of it had been given to them for services rendered, the remainder was theirs by right of conquest.[15]

The overall question was: did the British Government, Cape Colony or South African Republic control Bechuanaland?

Thompson and the Boer Republics

Reverend J.M. MacKenzie was initially appointed as Commissioner over the territory that was to be named British Bechuanaland, but as a missionary sympathetic to the natives he was bitterly opposed by the Boers and replaced by Captain Graham Bower, then secretary to the Governor of the Cape Colony. He asked me to accompany him and together we got in close touch with van Niekerk and his followers. Bower was later to report to the Governor: “I was fortunate in securing the services of Mr Frank Thompson, Inspector of Native Locations in Griqualand West who possessed a thorough knowledge of Dutch as well as of the various Bechuana dialects.”

The crisis threatens Rhodes’ plans

The chaos caused by these Boer Republics threatened Rhodes’ plans for opening up the north through Bechuanaland. Thompson went to Kimberly to tell Rhodes his plans would be in jeopardy if there was conflict between the Boers and the missionaries that had to be settled by the Imperial Government over the Cape Colony and suggested to him that he should offer his services to Sir Hercules Robinson[16] as Special Commissioner.

Rhodes agreed, but stipulated that Thompson should be his secretary, guide and interpreter.

John Smith Moffat in 1858 Sir Hercules Robinson,he British High Commissioner for Southern Africa

With Rhodes in Bechuanaland

Rhodes saw the Stellaland Republic as a deadly threat to his plans for opening up the north and decided the best way to placate the Boers would be to offer them land titles on condition they accepted British rule. Thompson was sent to negotiate with them. The Boers were initially inflexible, but Thomson sensed they would change and stayed to negotiate. Rhodes threatened to leave and was persuaded to stay. By sunset next day the Boers had agreed and a document was drawn up subject to approval by British Government and was signed on 8 September 1884.

Thompson then met Gey van Pittius, self-styled President of the Goshen Republic at Rooi Grond and was promptly locked up in a corrugated-iron hut. He was soon released and brought before the President who would not commence negotiations before certain conditions were met, including the payment of £25,000.[17] Whilst giving this message the Boers were attacking Chief Montsioa at Mafeking with five hundred Boers and a thousand natives, cannons and rifles.[18]

Rhodes countered by saying he would not negotiate whilst hostilities were in progress. So Rhodes and Thompson left for Barkly West where Rhodes spent the night on the telegraph to Robinson and suggested that Bechuanaland be annexed by the Cape Colony. This the Cape Parliament turned down and the Warren expedition became necessary.

Thompson is commissioned as a lieutenant on the Warren expedition

Thompson’s commission did not last long as he says Warren wanted revenge for Majuba[19] and was spoiling for a fight with the Boers, whilst Thompson believed that the Goshen Boers could be ousted through negotiation. When Warren reached Rooi Grond he found the Boers had left for the Transvaal, the expedition was ordered back and the whole region to Ramatlabama was declared British Bechuanaland.

Re-organising the De Beers Compound system

Thompson writes that in 1886 Rhodes asked him to leave his role as British Resident and Chief Inspector of Nature Reserves in Griqualand West to reorganise the entire compound system for native labour at De Beers Mines at Kimberley as the Illicit Diamond Trade (IDT) was costing the company millions of pounds. Despite tough laws, the native workers sold illicit diamonds to native middle-men who sold to white buyers who evolved ingenious ways of concealing stones and smuggling them out the country. The compound scheme met initial resistance, but strikers were replaced and work resumed.

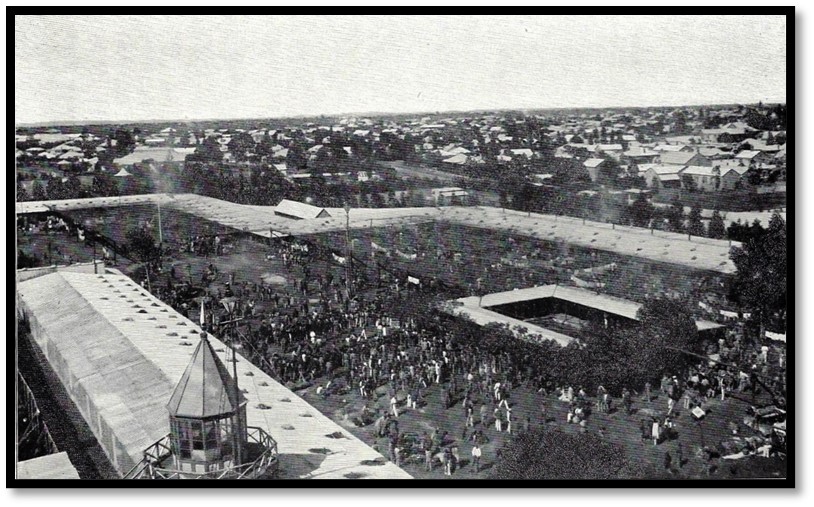

The De Beers Compound with the swimming pool in the centre

An article ‘The Diamond Mines of South Africa’ in the National Geographic of 1906 states: “there were 17 compounds in the diamond fields, 12 owned by De Beers. The largest belonged to De Beer: it was 4 acres and held 3,000 workers, who were contained in the area by 10 feet tall corrugated-iron fences; they slept 20-25 to a 25 feet x 30 feet room… De Beers sought to prevent loss by putting up a fine wire mesh netting over all open areas in the compound so that diamonds could not be thrown up and over the compound walls. When contracts expired workers who decided to leave were sent to another part of the camp to stay for a week before exiting. All of their belongings (such as they were) were either completely searched or seized.”[20]

Thomson writes: “the best recruiting agents for the mines were natives who came home with a good sum.”[21]

Mission to get a concession from King Lobengula

It was in 1888 that Thompson made his name and fortune and led to the foundation of Rhodesia. It started after he left De Beers and was invited by Charles Rudd,[22] now a director of Gold Fields of South Africa, on a trip around the Witwatersrand goldfields. Following this he was appointed Protector of Natives and Government Supervisor of all compounds in mining areas. But soon after Rhodes sent for him and Thompson states his first words were: “now for our day dreams of securing the territory up to the Zambezi for the British nation.” When told that Thompson had just been appointed to the above post, Rhodes contacted Sir Jacobus de Wet, Minister in charge of Native Affairs and he was granted three months leave.

Rhodes’ plan was that Rudd and Thompson should go to Bulawayo where they should try to obtain from Lobengula, King of the amaNdebele, the sole concession for mining minerals in the country. He told Nathaniel Rothschild, “someone has to get the country. And I think we should have the best chance” and that Lobengula was the key, “I have always been afraid of the difficulty of dealing with the Matabele King. He is the only block to Central Africa, as, once we have his territory, the rest is easy…as the rest is simply a village system with separate headmen, all independent of each other.”[23]

A syndicate was formed between Rhodes, Rudd and Thompson and an agreement signed between them. They would only put up the capital necessary for obtaining a concession and if they succeeded it would be the sole property of the syndicate. To contribute my share of the £37,000 I had to get an overdraft from the Cape of Good Hope Bank and Rudd was my guarantor.

Charles Dunell Rudd James Rochfort Maguire

James Rochfort Maguire joined Rudd and Thompson on the expedition at Rhodes’ request, but it was clearly understood he was not a member of the syndicate. As a lawyer, he may have put the final concession into legal format, although Rudd was also up to the task. Rhodes knew Maguire from Merton College, Oxford but he seems an odd choice being described by contemporaries as an ‘effete snob’ and a ‘spoiled child of fortune.’ Rotberg suggests that it was because Maguire was friendly with the Rothschild’s and would afterwards marry the daughter of the Speaker of the House of Commons i.e. he had useful contacts.[24]

Thompson purchased at Kimberley two teams of good mules, two wagons with drivers, Dreyer and Denny and stores for three months; on 15 August 1888 they started off having told everybody they were going hunting. Shoshong was reached after twenty-two days where they stopped as Chief Khama III had prohibited all travel following the death of Grobler, the South African Republic agent.[25]

Fortunately Sir Hercules Robinson had written a letter bearing the Queen’s stamp addressed to King Lobengula and Mrs Hepburn, wife of the Reverend Hepburn told the chief in charge (in Khama’s absence) that they should be allowed to pass as they had a letter from the Queen. After a further seven days travel they reached Tati on the border of Matabeleland but found orders had been given that no white men were to cross without Lobengula's consent.

At this point Rudd decided, against Thompson's advice, to write a letter to Lobengula and send it by messenger stating we were not ‘needy adventurers’ nor had we come to beg from the King, or to ask for anything from him. This term ‘needy adventurers’ really angered the traders at Bulawayo. Rudd believed to the letter to Lobengula from the Queen was sufficient to proceed and they pushed on into Matabeleland. At Kumalo they met the messenger who told them the King had refused permission to enter the country. However, once the King heard the news he granted permission for them to continue.

John Smith Moffat arrives at Bulawayo before the Rudd party

Moffat reached Bulawayo in late August before the others and found the King troubled by the various concession-seekers plaguing him as Thompson wrote later, “like flies around a dish of milk.” Moffat reported back to Shippard, “There is a distinct tendency to draw in and to concede less and less to Europeans…” and he had, “put the chief in possession of the views and wishes of the government respecting the grant of concessions…” and “He will in all probability be unconsciously influenced by what I have said to adopt the course we desire”[26] which was, of course, to favour the Rudd party.

This echoes the views of the administrators at the time. Francis Newton, another Rhodes supporter from Oxford days, and now Colonial Secretary of Bechuanaland, wrote to Moffat after talks with Rhodes, “He is prepared to do everything that Lobengula and those around him may wish, if the King will trust him and make an extensive concession. What he does not care for is to be merely one of a number of concessionaires…I confess I should like to see a thorough imperialist and a good man of business at the same time, as he undoubtedly is, get a good footing in that country. Much more can be done by private enterprise than by the lukewarm advances of the Colonial Office at home.”[27]

Arrival at Bulawayo on 21 September 1888: but the Bulawayo traders are antagonistic

Thompson says the traders feared any concession being granted to the Rudd party and there was also opposition from Germany and Portugal as a concession would close the door to any but British interests. This opposition and the suspicious nature of the amaNdebele natives were the chief difficulties they had.[28]

“On the evening we arrived we went to greet His Majesty. The interview was necessarily short as the law among the Matebili was that no native man, woman or child should be out after dark, as only wolves and witches were then supposed to be abroad. So strict was this law that anyone discovered prowling near a village after dark could be killed at sight without question. We found Lobengula to be just such a figure as I had expected. A man of about twenty stone, tall, stout, well built, looking every inch a King. His palace consisted of a pole stockade with about a dozen huts for the queens who were with him at the time. He had two hundred wives in all. Within the enclosure was a private sanctum constructed of poles known as the ‘Buck Kraal,’ which accommodated at night about five hundred goats. It was in this place that all the plans were concocted for smelling out and killing people when the sacrifices had to be made for rain. The rain maker was the King.

Lobengula was seated on a block of wood, surrounded on all sides by goats and dogs. We had agreed that we should greet the King as an ordinary gentleman, and that by adhering to this line of conduct we could not go far wrong. We had been told that we should have to approach him by crawling on our hands and knees and remain in a recumbent position while in his presence. This was the custom, and the whites who had thrown in their lot with the natives were wont to observe it.[29] We decided, however, to walk boldly up to him in the ordinary fashion, and this we did, to the evident surprise of his entourage. He kept us waiting for some time. Then he enquired who we were and put many commonplace questions which we answered. We handed him a bag containing a hundred sovereigns by way of a greeting gift. We were then told to return to our camp and sleep nicely, a piece of advice which we lost no time in following.”[30]

The Rudd party meet King Lobengula

Here is Thompson’s account: Three days having passed, we presented ourselves before the King and I opened our business to him. He listened attentively and showed considerable intelligence. I explained that we were not Boers, and were not seeking for land, but only asked the right to dig the gold of the country. I told him that all eyes were turned to his dominions, which I likened to a dish of milk that was attracting flies. I said that the Boers were evincing signs of pushing their way from the south, alluding at the same time to the death of the Transvaal emissary, Mr Grobler. I gave him to understand also that the Portuguese were pressing in on the east, or Mashona side, where the vast ocean washed.

On hearing this the King at once observed: “You are only a boy. How do you know that?” He thought that the only way to the east coast was through his country. I replied that I knew by the books of my fathers that the great waters were round there. But in vain did I endeavour to convince him, for he persisted in saying that I must have travelled through his territory if I knew of the Mapunga (rice-eaters, meaning the Portuguese)

Our conversation was carried on in Sechuana,[31] a language only he and a half-dozen Matebili[32] understood. Fortunately the white men at Bulawayo did not understand it. Very little headway was made at the interview, but he was much interested. Among other things I described the Zulu War of 1879, and the engagements in which I had taken part in 1878. Until then white men had been regarded by the Matebili more or less as dogs, but the King took an extraordinary interest in examining the scars of gunshot wounds on my body. I believe he would have preferred to talk of anything rather than discuss giving away the gold concession, a subject he carefully avoided. I as diligently referred to it, with the result that to be rid of us he at last said, “Well, go and talk to the councillors.”

I asked him when I should be able to do so, and he replied that he would summon them to discuss the matter shortly. With this we were obliged to be content.

Before this interview I had spoken to Lotjie, who occupied among the Matebili a position equivalent to that of Prime Minister, and to Sekombo [Sikombo] the Induna who in 1896 was to meet Rhodes at the Motopos (Matobo) and put our scheme carefully before them. I promised them gifts if they assisted us. Rudd and I discussed the feasibility of obtaining a thousand Martini-Henry rifles and ammunition for Lobengula. We felt certain that nothing else would obtain us the concession. We agreed that we should promise these and in addition a gunboat for the Zambesi.

Courtesy of the Africana Museum, Johannesburg. Lobengula, King of the amaNdebele. This is believed to be the only photo of him with an unknown white man

The amaNdebele have no use for money

Thompson writes in justification for offering guns and ammunition: This new temptation was rendered necessary owing to the light estimation in which gold coin was held by natives. Money had no value. We had £10,000 with us in sovereigns, but the natives referred to them as ‘lumps of metal’ and ‘buttons’ and said they were fitted for no better use than to make bullets.

When first I went to Matebililand (sic) I could buy an ox for three pounds’ weight of beads, costing 1s. 6d. a pound. A sheep could be bought for a yard of calico worth sixpence. A sovereign would not buy an egg, but an empty cartridge case would buy two fowls. A cartridge case was worn as the tribal token in the slit made in the ear. Guns and ammunition, in short, were considered the only things really worth having. This being the case, it will readily be understood how useless it would have been to offer only a monthly payment of so many sovereigns. If we had not obtained guns and ammunition to give as well, all our efforts would have

been in vain. The natives had seen the effects of shooting by hunters, and naturally coveted such efficient treasures.[33] When the time came, of course, we made the most of our ability to supply rifles.[34]

Martini-Henry rifles used a ‘577-450 black powder cartridge

The delays before they meet the Indunas

Nobody can conceive the weariness of the ensuing days. It was simply a matter of waiting and watching. The native mind moves slowly, and for reasons of his own Lobengula did not wish to be hurried. He was willing enough to meet us but did not wish to discuss a concession. We were reduced to spending every day in our little camp, most of the time playing backgammon or reading. We did not dare to go far afield in case we might be called by Lobengula.

The continual delay made Rudd anxious to return, but Rhodes insisted that he could not leave Bulawayo without the concession, "You must not leave a vacuum…leave Thompson and Maguire if necessary or wait until I can join ... if we get anything we must always have someone resident or else they [the other white would-be concessionaires] will intrigue and upset us."[35] Rudd did manage to present the King with a draft concession, written by himself, that Reverend Charles Helm[36] interpreted for the King. At a later time Helm declared that Rudd made a number of verbal promises to Lobengula that were not written into the concession document, including, "that they would not bring more than ten white men to work in his country and that they would not dig anywhere near towns, that they would abide by the laws of his country and in fact be his people."

Rev Charles Daniel and Elisabeth Eduardine (née Von Putt Kamer) Helm

Sir Sidney Shippard arrives to back up the Rudd Concession seekers

During the following weeks, the Rudd party did talk with Lobengula, but with little progress and the King used Shippard’s visit to suspend talks. John Moffat,[37] who was resident in Bulawayo, advised Lobengula to work with the concession party that was backed by the most commercial resources (i.e. the Rudd party representing Rhodes) rather than the many small concession-seekers and that he should not make a decision until his boss, Sir Sidney Shippard[38] had arrived at Bulawayo during mid-October. Shippard was an important Rhodes’ ally. Rotberg writes that Shippard was: “Long a believer in Rhodes’ aspirations, long a confidant and a one-time sole executor of Rhodes’ will, no other British official could have been better placed to further the diamond magnate’s approach to Ndebeleland.”[39]

Galbraith writes, “Rhodes had a trump card which won the game. The support of local imperial officials. With their backing he was able to neutralise Maund’s claims to governmental favour. Robinson was committed to Rhodes, as were his subordinates, Shippard and Shippard’s assistant, Frances J Newton.”[40] Galbraith goes onto say, “they shared Rhodes enthusiasm for northward expansion and his aversion to Downing Street.”

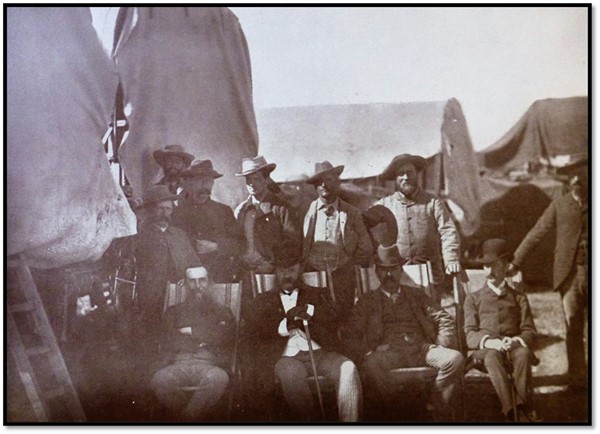

Photo by Ellerton-Fry. L-R (seated): John Moffat, Sir Sidney Shippard at Telegraph Camp, Mafeking

Shippard was accompanied by Hamilton Goold-Adams and sixteen troopers from the Bechuanaland Border Police (BBP) whose arrival in Matabeleland created a storm amongst the Indunas who interpreted this as a mini invasion force and amaNdebele Majakas subjected the party to much verbal harassment. Shippard alarmed the King by saying the Boers had their eyes on acquiring Matabeleland and he backed Rudd’s party by stating they were supported in their mission by Queen Victoria.

Indaba with the amaNdebele Indunas

Thompson writes: Our anxiety and impatience increased day by day, but at last, at the end of October 1888, a month after we had arrived at the King’s kraal, we met one hundred Indunas in an indaba. These Indunas constituted a full council of the Matebili nation. Mr. Helm (a missionary) represented Lobengula and explained our proposals. The indaba assembled at a spot fifty yards from the King’s headquarters and took place on two consecutive days.

I first addressed the meeting and entered fully into the question. The Indunas sat perfectly quiet and listened intently. They heard from me all about the Boers pressing into the country which I likened to a dish of milk; about the Portuguese encroaching; about the thousand Martini-Henry rifles and hundred thousand ball cartridges; about the gunboat for the Zambesi.[41] They heard all this, but when it came to asking them for the sole right to the gold throughout the whole country, the cry arose from one and all, “Maai Ba Booa.” This may be translated, “Mother of Angels, listen, listen.”

By way of explaining the idea of ‘sole right’ I told them that I was not going to have two bulls in one herd of cows. All discussion with natives on grave matters was in my time carried on more or less in metaphor, a style carrying much weight when skilfully used. On my alluding to bulls on this occasion one Induna observed that I was right, for the bulls would certainly fight instead of looking after the cows. Thereupon another Induna said, “Yes; I can see he is frightened of other men in the country.”

“He is greedy then,” said a third. At this Samapolane [Somabulana] an Induna who was also to meet Rhodes in the Motopos, rose and said, “No; we will give you a part of the country.”

This was not what we wanted, but I had created an impression, and my talk about rifles had produced the effect intended. So my reply was to turn to Rudd and say, “Come, we will go. These people talk only about giving us a place to dig.” Rudd, speaking for the first time, said, “All right, let us take a piece” and then in an aside to me, “We can gradually ingratiate ourselves with the people.”

Maguire, also opening his mouth for the first time, seized Rudd by the coat tails and said, “For heaven’s sake, Rudd, sit down and don’t interfere with Thompson.” I jumped up and made it appear that we would not discuss matters further. I said, “Yes, Indunas, your hearts will break when we have gone. And you will remember the three men who offered you moshoshla (Martini rifles) for the gold you despise in this land.”

The farewell “Good day to you” was half out of my mouth when Lotjie, the Prime Minister, caught me by the little finger, “Sit down, Tomoson" he said; “I thought you were a man when you began to speak. We as old men know about the Portuguese to the east, and the ocean running past where the sun rises, but truly I see you are only a child.”

Lotjie then went into the King’s private enclosure where he and Lobengula remained in close conference for half an hour. When he came out he called, “Tomoson, come in here. The King wishes to speak to you alone.” I stepped inside and Lotjie asked me to sit down and relate to the King all I had said outside to the Council. This I did, emphasizing what I had said about the sadness of Matebili hearts when we left and how absurd it was to think we did not mean to do what was right. “Who gives a man an assegai” I said, “if he expects to be attacked by him afterwards?” This was my answer to the fear that in giving the concession the Matebili would open the door to white aggression, for rifles would then be the best defence they could have. This made an obvious impression on the King, and after pondering it for a few moments he exclaimed, “Give me the flyblown paper and I will sign it.”[42]

Lobengula signs the Rudd Concession

Thompson writes that he said, according to our customs, we three brothers should all be present when the document was signed, as in the event of Rudd, Maguire or myself dying, there would still be one left who would know all about the transaction. He asked, “Are you brothers?” I replied, speaking in the usual metaphorical style, “Yes, there are four of us. The big one (Rhodes) is at home looking after the house and we three have come to hunt.”

Thompson then collected Rudd and Maguire, saying they should come at once as the King wished to sign and Rev Helm, who wanted to ensure that all was fair and above board, accompanied them.

We seated ourselves in a semicircle with the King in the centre. The Concession[43] was placed before him and he took the pen in his hand to affix his mark, which was his signature. The place on which he was to make his mark was pointed out, and he made it. As he did so Maguire, in a half-drawling, yawning tone of voice, without the ghost of a smile said to me, “Thompson, this is the epoch of our lives.”[44]

Wikipedia: The Rudd Concession

The rights contained in the Rudd Concession

When Lobengula made his mark on the concession he undoubtably did not understand what he was signing over that included, ‘the complete and exclusive charge over all metals and minerals situated and contained in my Kingdoms, Principalities and dominions together with full power to do all things that they may deem necessary to win and procure the same and to hold, collect and enjoy the profits and revenue…from…metals and minerals.’

Clearly the legal language would not have been understood by Lobengula and masked the real future complications that would arise for both the King and the amaNdebele nation. Probably even Thompson, understood that Rhodes was an imperialist, but who does not appear to have been a devious man, was innocent of the way the Rudd Concession would be interpreted in the future.

Rhodes himself could not have been happier as he knew the concession would be interpreted by the Colonial Office as a legal transfer of mineral rights to himself and his associates, even if the process was basically a swindle. Both Rhodes and Rudd believed the Rudd Concession gave the rights to far more than just metals and minerals as Rudd wrote to Curry before leaving for Bulawayo, “that our best chance of a big thing is to try to make some terms with Lobengula for a concession of the whole of his country.”[45]

Rudd takes the signed concession out the country, but Thompson and Maguire stay at Bulawayo

Rudd in his diary wrote, “Not one of the white men at Bulawayo had an inkling of our success. Nor did we think fit to enlightened them.” Once the concession had been signed, Rudd rode back to the Cape and Cecil Rhodes took it to London to get it ratified by Queen Victoria.

For the next year and a half, Thompson and Maguire camped at Bulawayo. Quickly the rival white concession seekers started spreading rumours that Lobengula had signed away more than just mineral rights. Thompson had given Lobengula an undertaking that the concession would be kept secret for a time, but Sir Hercules Robinson insisted that a ‘communication’ be published in the newspapers and so the news came out. Lobengula was given a copy of the newspaper report by one of the Bulawayo traders.

Thompson writes: The white men, taking advantage of my being single handed[46] and of the fact that a large section of the natives headed by a renegade Xhosa named William Mzizi[47] was secretly opposed to Lobengula and working for his downfall, had urged the natives to call the big meeting. Thousands were summoned.

Tensions rose, different amaNdebele factions threatened violence, and Thompson and Maguire were frequently called in for cross-examination. Thompson writes: I found myself forced to sit and answer such questions as these, ‘Have you got a brother named Rhodes who eats a whole country for breakfast? Is it not true that Maguire is a magician who rides wolves at night time? I was insulted in every way by the Indunas, and the white men threatened to shoot me. It was no child’s play, but after being cross-examined for nearly ten and a half hours I emerged satisfactorily.

The Indunas also insisted that Thompson should send for the original concession to ensure it was the same one that Lobengula had signed and eventually after the Colonial Office had used it as the basis for the Royal Charter it was sent back to Bulawayo where Thompson buried it in a pumpkin gourd, telling nobody but his Zulu servant Charlie, and putting maise corn in so that if he was killed the growing stalks would reveal the concession’s location.

Soon after in April 1889 Drs Jameson and Rutherfoord Harris brought up the first consignment of Martini-Henry rifles; the payments of £100 per month were also being made.

Rhodes stated he would bring the guns and rifles himself to Lobengula

In mid-December Rhodes wrote to Rudd, “I shall not approach Lobengula without the guns…and cannot leave here without seeing safe departure of guns” and he had, “no intention of leaving without the guns and making a fool of myself with Lobengula by finding out they have been stopped in the Colony or Bechuanaland.”

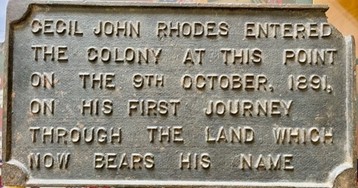

However this never happened. Rhodes reached Fort Tuli only as late as 1 November 1890 and only entered the country via Beira and Penhalonga with Major Frank Johnson and de Waal on 9 October 1891.[48]

The Plaque that was erected at Penhalonga to commemorate Rhodes’ visit

Maguire and the sacred pool – more harassment

Maguire, who spoke no isiNdebele and was relatively ignorant of their customs was so desperate for a wash that he brushed his teeth and prepared to bath in a sacred pool of the Umguza river. He was apprehended by the pool’s custodians who reported to the King that they: “had beheld Maguire approach the King’s sacred fountain; how the white man began to undress himself; how he washed his teeth with some red stuff; how he then took water from the fountain, gargled it in his throat and spat it forth into the pool, which became blood red; how he repeated the process, but this time the water turned white.” Tabeni, one of the pool’s guardians, then described how, “unable longer to endure the sight, he and the others descended upon the evildoer and seized the stuff with which the King’s water was being poisoned; how one man had taken up the bottle of eau-de-Cologne and smelt it; how a Zulu boy who had travelled with white men said that the odour was one white men loved, which accounted for their horrid smell.”

About this time, Lobengula's mother died and the white men at Bulawayo alleged that the poisoning of the water was the cause and this did not improve matters.

They escaped with a fine of virtually everything they had with them. “They were continually getting more, until they extracted twenty times the value of a reasonable fine. Poor Maguire’s hairbrushes, toothbrushes, clothes brushes, razors, cherry toothpaste and eau de Cologne were all confiscated. Life for him was hardly worth living without them.”[49]

Maguire and the escaped slave

Maguire finally left to go home, and on his way took pity on an escaped slave of eight years and gave him a ride on his wagon. The slave was shortly re-captured by an impi sent in pursuit and Thompson summoned before the King to explain why his ‘brother’ had stolen the King’s property - the slave. He tried to bribe the amaNdebele who had recaptured the slave,[50] but this backfired.

“…On my arrival at the royal kraal I sat down and waited, but on this occasion the men of the impi began talking of how they had walked one hundred miles to catch the slave boy who had been taken by Maguire. Their ominous scowls, their angry words and threatening manner, boded ill for me. Although it is customary, to impress a visitor with a sense of the King’s dignity, to keep him waiting, Lobengula did not delay the proceedings as long as usual. Calling to me in a sharp tone he said, “Thompson, where is your neck?” I remained very quiet. “You hear me?” asked the King.

I said slowly, “If a child has done wrong, does its father kill it, Oh King? Does not a horse stumble though it has four feet? I have but two. I have no answer to make, for you will not believe me, because I said that Maguire did not steal the slave. I am found out in what the impi reports to you and must conclude that I must bear the consequences. But I can tell you this, Oh King, that I did not know the child had gone with Maguire.”

The King then produced the two spoons and said, “you said they were not to tell the King. Are you the King? Do you wish to undermine my authority?” I replied, “The Induna had taken much trouble, and it was to reward him that I gave the things, being thankful that the slave was restored. I'm afraid to speak now that I am stated to be a liar and certainly events seem to bear that construction, for the slave was found at Maguire’s wagon. I can only crave forgiveness as a son from his father…

…The King decided, to my intense relief, that for the present he would pardon my offence. But his decision caused great distress and dissatisfaction to the impi. In their opinion, my body was not good enough for hungry dogs. As I left the kraal I was greeted by curses long and deep, and they came from all sides. I was called liar, thief, magician; I was told they would have my blood yet…

…The whites were indefatigable in spreading false reports and in this case, they persuaded the natives that I knew perfectly well that Maguire had taken the slave.”

Thompson feels completely isolated

He writes, “My only support and friends at this time were Ben Wilson and Alexander Boggie.[51] I should have been only too glad to have left the country, but apart from the difficulty of getting away there was too much at stake. I had declared without avail that I was innocent of the charges brought against me, and I lived in fear of my life. But nevertheless I felt that I must stay and keep the concession safe for our partnership.”[52]

The situation continued to get worse for Thompson, “As time went on the Matebili became more and more excited. Thousands came from all directions to ask the King if it were true that the white dog Thompson had bought the land. Among the Matebili I was now the most notorious person in the country, and among a section of black and white schemers the most hated. My main difficulty arose from the false interpretation of the concession by white men at Bulawayo. They told the King to study the word land. It was true that the word occurred in the concession, but in a very different sense from that imparted to it by these men. In misrepresenting the concession to the Matebili they relied chiefly on the passage reading: ‘Whereas I have been much molested of late by divers persons seeking and desiring to obtain grants and concessions of land and mining rights in my territories.’

A copy of the document was produced at a council of three hundred Indunas, and one of the whites asked me to interpret the word ‘land.’ He covered up the other words of the paragraph. I asked the Indunas which of them could tell me whether a beast was male or female when only part of the hide was shown. They answered, ‘None, unless he saw the remaining part of the body.’ ‘I, too,’ I said, ‘cannot interpret that word, for you allow this man to cover up the rest of the sentence.’ I stoutly refused to discuss the word out of its context as the whites would have had me do.”

This meeting lasted from seven in the morning until five in the afternoon. I was asked by every Induna in turn from whom I had bought the country. My answer was, ‘Matebili, did I not tell you when first I came into this country, about a year ago, that we were not farmers and wanted no land, cattle or grass, but that we wanted the gold in the stone?...”[53]

Fortunately letters arrived from Rhodes that cheered Thompson up including news that he was appointed the Chartered Company representative at Bulawayo.

Thompson is appointed the British South Africa Company representative at Bulawayo

Rhodes wrote to Thompson on 14 February 1889, “…We wish you to be the Syndicate Chief Representative at the King’s and to manage the whole matter with Maguire. We offer you £2,000 per annum and to build a house at once and to send up Mrs Thompson. We feel it would be fatal if you left now…I think you underrate your opponents. I hear tomorrow a flaring notice is coming out in all colonial papers as from Lobengula denying our Concession and saying people may go into his country. You should get Lobengula to contradict this and forward at once, otherwise the whole country will trek in...”

Lobengula who had stayed away from the meeting and the cross-questioning now came up to Thompson and said, “What are they asking you, Tomoson? They asked me from where I got the land. What have you told them? If they say I have the land, let the man stand before me, and tell me from whom I got it. Pogee,” said the King, meaning very sound answer, “What more is there to say?” Lobengula sounded satisfied and as he walked away Thompson felt relieved.

Lotjie is made the scapegoat

Lotjie, was sitting beside me and quickly accused by the Indunas of having advised the King to take the thousand rifles in exchange for the concession. Two chief Indunas, but not Lotjie, went and spoke privately with the King. When they returned a decree was passed that Lotjie was responsible for the turmoil and would be killed. Lotjie stood up and handed his snuff box to a man standing near. He was taken outside the Umvutcha kraal and knelt down saying, “Do as you think fit with me. I am the King’s chattel” before being killed with one blow from the executioner’s knobkerrie. In reality, Lotjie’s execution was to protect the King from amaNdebele suspicions he had given away the land.

Thompson writes, “That night was spent by the Matebili in putting to death the men, women and children of Lotjie’s family. It was the most terrible night in my experience. Charlie crept close to me in the darkness for protection and softly exclaimed as each dull thud of the execution stick came to our ears, followed by the shrill cry ‘Ay yi yi.’ Some three hundred men, women and children were killed—Lotjie’s whole kraal with the probable exception of the sucking child.”[54]

Thompson goes to discuss events with Rev Helm at Hope Fountain

Thompson writes he had just started for Hope Fountain when he met a native riding a grey horse and was told, “Tomoson, the King says the killing of yesterday is not yet over” a statement that Thompson believing the King was friendly, took as a well-meant hint. Then he saw a crowd of young amaNdebele in war dress approaching and no longer felt any doubt of their intentions. There and then he decided to make a bolt for it.[55]

The fastest horse[56] was cut from the traces and he rode to the Umgusa river ford. He had no saddle, just an improvised bridle from the trap harness and had lost his hat. In the blazing sun he improvised a hat by tying four knots in his handkerchief and stuffing it with grass. By sundown with neither food nor water and thinking he might be attacked by lions, he tied up his horse, climbed into a tree and there spent the night. The next day he rode until the horse was knocked up and then walked, covering thirty or a forty miles to Tati.

Without water his tongue became swollen, his eyes so bloodshot he could scarcely see. On the second day he came to a waterhole and lying down at the edge of the water very painfully drank and drank. This gave him dysentery next morning. Fortunately he met some Makalaka natives and exchanged his pocket-knife for some mealies before continuing and then luckily came upon a trader with a mule wagon who gave him a lift to Shoshong and from there travelled to Mafeking.

Both Rhodes and Sir Hercules Robinson request Thompson’s return to Bulawayo

Thompson had spent fifteen months at Bulawayo but when he met Jameson at Kimberley he was persuaded by Rhodes to return with Jameson and introduce him to the King and dig up and give the concession to the King. Rhodes wrote, “I want you to return because the King recognises you as the concession and you know perfectly well it would not be ratified unless you are present.”[57]

Land rights were acquired through the concession obtained by Lippert

Thompson maintains throughout that the Rudd Concession was only for mineral rights. He says the metaphor he used with Lobengula was that he likened Matabeleland to a cow and said, “King, the cow is yours. If she dies, the skin is yours. If she calves, the calf is yours. I only want the milk.”[58] But that was not how things worked out. Rhodes used the Rudd Concession to get the British Government to allow him to set up a Chartered Company for the purpose of exploiting the minerals of Mashonaland and any other trading opportunities that might arise in this part of Africa.

W.H. Schrӧder. Rhodes and Lippert settle their battle over land rights “Under the Table”

Edward Renny-Tailyour with Frank Boyle and O’Reilly obtained for Eduard Lippert, an estranged cousin of Alfred Beit, an agreement giving him the right to manage lands, establish banks, mint money, and conduct trade in Mashonaland where the Chartered Company operated in return for a ‘one-off’ sum of £1,000 and £500 annually. However, its genuineness was questioned, because the witnesses were the Induna Mshete and Renny-Tailyour's associates, one of whom said Lobengula had believed the concession was for Theophilus Shepstone's son, with Lippert only acting as an agent.

Rudd persuaded Lippert to get his concession formally signed by Lobengula; this was done in November 1891 and in return Lippert received 75 square miles of land and mineral rights of his choice and thirty thousand shares in the Chartered Company.[59]

The British South Africa Company occupies Mashonaland in 1890

The British Government gave the Chartered Company exclusive trading rights in this region. The Pioneer Column, organised by Frank Johnson, supported by armed British South Africa Company Police, set out for Mashonaland, where they established the settlement of Salisbury (Harare) This was not what Lobengula had thought he had agreed to, but as the settlers were not in his territory, peace was maintained for a while. But soon the natives near Fort Victoria appealed to the company for protection against Lobengula's raids. This was more than Lobengula could stand - if natives who had formerly paid tribute could thumb their noses at him with impunity, his empire would disintegrate. He sent his Majakas to massacre the rebellious natives, who called on the company police to protect them.[60]

The Matabele War and the invasion of Matabeleland was underway. Despite their vastly superior numbers, this was not a war the amaNdebele could win, against superior technology, and in short order Bulawayo had been captured, Lobengula fled north and died and the amaNdebele lost their independence and were incorporated into the eventual British colony of Rhodesia. Arguably this is what Rhodes had intended from the start. Matebili Thompson makes it clear in his autobiography that this was not what he thought he was involved in and that he deplored this outcome although it is hard to believe that he didn't have some idea of where the concession might lead.[61]

“I can truly say, and all my dealings with natives bear me out, that up to the very last moment of my residence with Lobengula I acted honestly towards him as a friend, and in the conviction that the Concession would bring immediate prosperity to him and his people. Fate willed it otherwise. Rhodes always assured me that he personally did not want the gold per se, or the land, but rather territorial administrative powers. He wrote to me that he wanted no rights in land, nor did I at any time imagine that we were entitled to them.

Situations developed which were contrary to the spirit in which I had regarded the whole thing, and situations I should not have been able to accept. Only once did I again visit Rhodesia. It was in 1904, as a member of the South African Native Affairs Commission. I was standing on the railway platform at Figtree when I was accosted by one of Lobengula’s Indunas. ‘Oh Tomoson,’ he said, ‘how have you treated us, after all your promises, which we believed?’ I had no answer.”

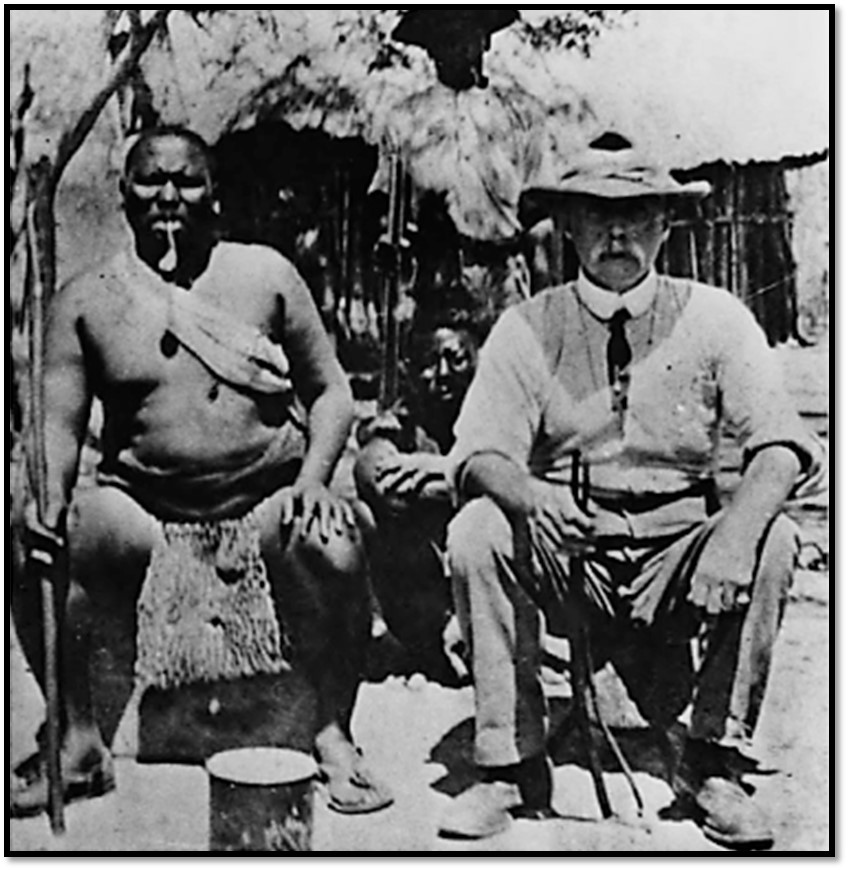

Matabele Thompson on a shooting trip in Zululand in 1924, aged 66 years

Later years

Francis Robert ‘Matabele’ and Georgina Thompson had three sons and two daughters,

Francis Charles

Edward Cresswell

Eileen Mary married Mitchell

Nancy Hely married Rouillard

Neville Rudd of 21st Lancers, Lieutenant killed in Action, 5 Sep 1915 in the North West Frontier, India

Thompson writes that he made a good deal of money through selling his shares in the Chartered Company at the right time through the advice of Rudd’s brother and this enabled him to buy Clay Hall in Essex and go to Keble College, Oxford.

Clacton Gazette: Clay Hall, Great Clacton, Essex

On his return to South Africa he entered politics under Rhodes’ leadership becoming MP for Mossel Bay and later, Wynberg. He was serving in Parliament at the time of the 1895-6 Jameson Raid that compelled Rhodes to resign almost all his offices, not only in the Cape government but also in the Chartered Company, and certainly permanently damaged his political standing and influence, although he refused to denounce Jameson. Thompson writes of Rhodes, “On many matters he consulted me and although we had many differences of opinion and many heated arguments, I was deeply in his confidence.”[62]

Later becoming disillusioned with the schism developing between Boer and Briton, when he believed the two races should be keeping in step, he finally stepped down from politics and devoted his attentions to the development of his beloved Cornforth Hill farm.

Matabele Thompson died at Cornforth Hill Farm, Barkley West on 3 May 1927 aged 69 years 7 months.

References

National Geographic 1906. The Diamond Mines of South Africa

J.S. Galbraith. Crown and Charter; The Early Years of the British South Africa Company. University of California Press, 1974

R.I. Rotberg. The Founder: Cecil Rhodes and the Pursuit of Power. Oxford University Press, 1988

N. Rouillard (Editor) Matabele Thompson: An Autobiography. Books of Rhodesia, Silver Series Vol 13, Bulawayo, 1977

R.F. Windram. The Reminiscences of Ivon Fry as told to Foster Windram during interviews in September / October 1938

Notes

[1] His father Francis Thompson; his mother Ann (née Backhouse)

[2] Vashambadzi were the mixed race sons of Portuguese men and local African women

[3] Matabele Thompson, P18: “I think Rhodes sought me out because of my knowledge of the natives and of things South African generally.”

[4] See the article Ivon Fry’s reminiscences of Bulawayo and Lobengula in 1888 – 89

[5] Matabele Thompson, P17-18

[6] Grey College was founded in 1856 and continues to the present

[7] Thompson describes with a sense of irony Rhodes and Rudd's early attempts on the diamond fields to make money by selling ice cream, “You are to imagine the great Cecil Rhodes standing behind a white cotton blanket, slung across the tent, turning a handle of a bucket ice cream machine and passing the finished article to Rudd to sell from a packing case at one of the corners of the Diamond Market. The ice cream was retailed at six pence a wine glass full with an extra sixpence for a slab of cake.” (198-9)

[8] This regiment was afterwards wiped out at Isandlwana

[9] His father was murdered in a particularly cruel way; his cousin tortured and died of his wounds later

[10] Matabele Thompson, P51

[11] Georgina (née Rees) daughter of Colonel Charles Rees and Ann (née Gill)

[12] Brother of the Boer War General Jacobus Herculaas de la Rey

[13] Stellaland was given its name (Star Land) from a comet that was visible in the skies at the time

[14] Goshen was named after the biblical Land of Goshen and founded by Nicolaas Claudius Gey van Pittius in October 1882

[15] Matabele Thompson, p62

[16] High Commissioner for Southern Africa 1881 - 1889

[17] Thompson and Rhodes quickly learned that Kruger’s government was encouraging the Goshenites to maintain a staunchly anti-British posture.

[18] Rifles and ammunition were supplied by General Joubert of the Transvaal Republic close by on its western border

[19] The Battle at Majuba Hill on 27 February 1881 was the final battle of the First Boer War and proved a decisive victory for the Boers who suffered 7 casualties compared with 287 British casualties and at the convention of Pretoria of 5 April the Transvaal regained its independence.

[20] ttps://longstreet.typepad.com/thesciencebookstore/2020/01/the-not-so-shiny-diamond-mining-compounds-south-africa-1906.html

[21] Matabele Thompson, P88

[22] Charles Rudd, Rhodes friend and partner on the diamond fields, had switched activities in 1887 from diamonds to gold discovered in 1886 on the Witwatersrand

[23] The Founder, P258

[24] Ibid, P257

[25] Piet Grobler had been mortally wounded on the Crocodile river by a group of Ngwato warriors while returning to the Transvaal and the Boers in the Transvaal Republic were threatening to attack the British-protected Ngwato chief Khama III in response. Eventually Khama paid Grobler’s widow £1,000 to settle the affair

[26] Moffat to Shippard 31 August 1888 quoted in The Founder, P258

[27] The Founder, P258-9

[28] For details of the rival concession-seekers and how they were ‘squared’ by Lobengula read the article Were Lobengula and the amaNdebele tricked by the Rudd concession under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[29] Ivon Fry disputes this

[30] Matabele Thompson, P104 - 6

[31] Setswana, the language of the Tswana people

[32] Thompson always insisted ‘Matabili’ was the correct way to spell the amaNdebele name and not ‘Matabele’

[33] The potential problem though was that Cape Colony legislation prohibited supplying guns and ammunition by sale or gift to Africans living outside the colony

[34] The first lot of Martini-Henry rifles and one hundred thousand cartridges were smuggled through Cape Town in three consignments to Lobengula but involved much manipulation and Shippard’s assistance and created a lot of controversy. Rhodes had also ordered a second batch of a thousand Martini-Henry rifles and these were taken on the Countess of Carnarvon, a small steamer, and unloaded its cargo of rifles and ammunition for Gungunyana in the estuary of the Limpopo river (not the Pungwe river as written in Thompson’s autobiography)

[35] Rhodes to Rudd on 10 September 1888 that probably relates to the activities of Edward Maund who was also seeking a concession on behalf of the Bechuanaland Exploration Company and its offshoot, the Exploring Company

[36] Reverend Charles Daniel Helm, a missionary of the London Missionary Society, was at Hope Fountain from 1874 to 1915. He acted as Lobengula’s interpreter in his dealings with the Rudd party

[37] At this time John Moffat was Assistant Commissioner under Sir Sidney Shippard in Bechuanaland (i.e. part of the British Colonial Service)

[38] Resident Commissioner of the Bechuanaland Protectorate 1885–1895

[39] The Founder, P253

[40] Crown and Charter, P67

[41] If Lobengula preferred he could choose £500 in lieu of the gunboat and also to be paid £100 per month

[42] Matabele Thompson, P130

[43] Ibid, P136: Thompson writes the concession was initially drafted by Rudd, altered by himself to make it more understandable by Lobengula and put into legal form by Maguire

[44] Ibid, P131

[45] The Founder, P264

[46] Maguire had gone to Tati to order back Alfred Haggard, brother of Rider Haggard, who was leading another concession party

[47] William Mzizi was Lobengula’s War Doctor, see the article The Mzizi Family War Doctors to Lobengula by R. S. Roberts in Heritage of Zimbabwe Publication No 41 of 2022, P13-16

[48] For a detailed account of Rhodes’ visit see the article Rhodes first journey into Mashonaland in 1891 through Penhalonga under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[49] Matabele Thompson, P147

[50] The bribe amounted to all that Thompson had left after their fine for ‘poisoning’ the King’s water…two spoons and a knife, and it was taken!

[51] Alexander Boggie wrote ‘From Ox-Waggon to Railway; being a brief History of Rhodesia and the Matabele Nation’ - a very early Rhodesian printing from the Times Printing Works at Bulawayo in 1897

[52] Thompson Maguire, P170

[53] Matabele Thompson, P175-6

[54] Ivon Fry disputes Thompson’s version that Lotje’s family and household were all killed and says that Lotjie’s women and children were distributed as slaves

[55] Understandable from Thompson’s account of events, but Ivon Fry again disputes the truth of it saying only Lobengula and William Mzizi amongst the amaNdebele had horses and that he did not hear of any majakas in war dress

[56] This was the horse called ‘Loben’ that Ivon Fry refers to and that Ian Grant was riding before he was killed by the amaNdebele the day before the battle at Shangani river (Bonko) in 1893

[57] Matabele Thompson, P184

[58] Ibid, P188

[59] See the article Land and the British South Africa Company - the Renny-Tailyour and Lippert concessions under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[60] See the article The build-up to the 1893 Matabele War under Masvingo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[61] This section is written in a different style from much of the book; I would suggest it was written by his daughter, Nancy Rouillard

[62] Matabele Thompson, P225