Ivon Fry’s reminiscences of Bulawayo and Lobengula in 1888 – 89

Introduction

Ivon Fry’s reminiscences were written down by the Bulawayo Chronicle journalist Foster Windram in September / October 1938 when Fry was 74 years old[1] and they have been lent to me by his son, Alan Windram. I have tried to keep the text as original as possible, although there are sections that have been shortened and where on occasion Fry returned to a subject already discussed, they have been amalgamated into one subject. I have kept the narrative personal by writing in the first person

Being a journalist Foster Windram had the skills to draw out these early memories from Ivon Fry. In 1888 Fry was a young man of 22 years old, and Foster Windram captures the emotion elicited by Fry’s memories. Fry’s father did not succeed in obtaining a concession from Lobengula; cancer forced him to return to Kimberley where he died, Fry clearly felt betrayed and had a great dislike of Cecil Rhodes’ and by association the lawyer Bob Graham and Francis Robert ‘Matabele’ Thompson,[2] the Rhodes’ representative who succeeded him at Bulawayo in 1889.

Ivon Fry’s reminiscences cover a wide period of Zimbabwe’s colonial history and may be unique in including the pre-concession days of 1888 and subsequent events. He marched with the Pioneer Corps in 1890,[3] knew Rhodes, Jameson and Johnson well, took part in the Battle of Massi-Kessi (Macequece) against the Portuguese, rode with the Victoria Column in 1893 to Bulawayo, was involved in the construction of the Beira Mashonaland Railway (1892 – 1898) to Umtali. He does not mention the 1896-7 Matabele (Umvukela) / Mashona (Chimurenga) Rebellions, so perhaps he was in South Africa at this time.

Fry’s memories capture a very special time when the Matabele controlled directly and indirectly a huge swathe of land and were probably at the height of their power. All this changed dramatically with the coming of the white man, but despite this, every account of Lobengula states that he was a man who kept his word and acted honourably towards all his visitors. It is a stain on those he dealt with, including Rhodes through Rudd and his associates, who knew he was illiterate and unversed in law, and took advantage of this in their commercial dealings with him.

Many of the comments made by Fry are about disagreeing points made in the book Matabele Thompson.[4]

Ivon Fry's first visit to Bulawayo in 1886 with his father for a Concession at Tati from Lobengula

My father, John Larkin Fry[5] had a share in the Tati Concession. Sir John Swinburne[6] had the concession for over ten years and he had not paid the rent in all that time. He was supposed to pay £30 a year. Sam Edwards[7] came up to see the King on behalf of a syndicate consisting of Dan Francis,[8] himself, Billy Davin, Thomas ‘Sandy’ Leask[9] of Klerksdorp, my father and others.

Sam Edwards asked the King: “what about Swinburne’s Concession?” Loben said he hadn't heard anything or received any rent from Swinburne for ten years. (Mining had not even started, not by Swinburne) Sam Edwards said: “What about giving it to me?” So Loben gave it to him in 1881, for which he paid all the back rent, £300 and offered Loben £300 a year.

Africana Museum (L-R) Matabeleland traders and hunters: William Tainton, George Phillips, Sam Edwards, Johannes van Rooyen

I was in Kimberley at the time. I came up to Tati in 1887 with my father to test the ground and the different reefs. Early in that year we came up on a visit to the King (Lobengula) at Bulawayo. It was the time of the Great Dance in January, the dance of the first fruits (Inxwala)[10] which is always held in Bulawayo. We stayed here about six weeks. That was my first visit to Bulawayo.

Was there an agreement between John Larkin Fry[11] and Rhodes to secure a concession from Lobengula?

In December 1887 Sir Hercules Robinson[12] authorised Sidney Shippard[13] to direct John Smith Moffat[14] to convince Lobengula to sign a treaty that accepted that Britain was the main power in the territories of the amaNdebele and Mashona.

By mid-February 1888 John Smith Moffat had negotiated the Moffat Treaty with Lobengula in which Lobengula agreed, “from entering into any correspondence or treaty with any foreign state or power to sell, alienate, or cede, or permit or countenance any sale, alienation, or cession of the whole or any part of the said Amandabele country…without the previous knowledge and sanction of Her Majesty's High Commissioner for South Africa.” The Moffat Treaty, “fitted Salisbury’s specifications of imperial influence without imperial responsibility.”[15]

Rhodes was quick to congratulate Shippard, “I am very glad you were so successful with Lobengula…At any rate now no one else can step in.”

Thereafter in 1888 Rhodes tasked John Larkin Fry, an employee of De Beers who spoke fluent isiZulu, to travel to Bulawayo and negotiate a mining concession with the King.

Sadly soon after reaching Bulawayo the elder Fry developed cancer of the jaw and left for Kimberley and died soon after.

Rhodes was already thinking in terms of a charter but after speaking to officials at the Colonial Office understood that it would only be obtained after obtaining a mining concession from Lobengula. He wrote to Shippard, “… I am going to have another try…It is an awful pity that Fry was so ill he could not stop and he has got no concession which I could use as a ground for making an offer to HM Government” and he continued, “I am sending now young Fry to try but he is a mere boy. I know Moffat cannot in any way directly support me, but you can tell him all my ideas and see if my Company is not able to obtain one, that Lobengula does not give away his territory in mining concessions to a lot of adventurers who do nothing but simply tie the country up.”[16]

Later on 1 August 1888 Rhodes wrote to Shippard that he was sending another De Beers representative to Lobengula (the Rudd party) meanwhile young Fry ‘was on the spot’ in Bulawayo and acting for Rhodes, “I have told him (Fry) to make another try when Moffat arrives who is taking a parcel for us to Fry for Lobengula containing a big present though he (Moffat) is in no way aware of the objects.”

From the correspondence there clearly was an agreement between Rhodes and Fry’s father to obtain a mineral concession from Lobengula.

The young Ivon Fry is superseded by Charles Rudd,[17] James Rochfort Maguire and Francis R. Thompson

On 15 August 1888 the Rudd party set off from Kimberley having told everyone they were going on a hunting trip.[18] Despite this, Rhodes did not seem overly optimistic about gaining a mineral concession from Lobengula and told Nathaniel Rothschild, “Still, someone has to get the country and I think we should have the best chance.”

There is no indication either from the sources (Rotberg, ….etc) that Ivon Fry was even told that his efforts were no longer required and that the role of obtaining a concession had been taken over by the Rudd party. Rhodes had squared all the competing concession-seekers. Henry Clay Moore was bought off, Leask, Fairbairn, Phillips and Westbeech were persuaded to sell their concession and Edwards, Usher and Tainton similarly settled. Rotberg includes Ivon Fry amongst those who settled, but Ivon Fry does not say he received any monies or shares from Rhodes; indeed the opposite, he says every time he approached Rhodes he was told, “Bring your agreement.”

Ivon Fry meets Lobengula

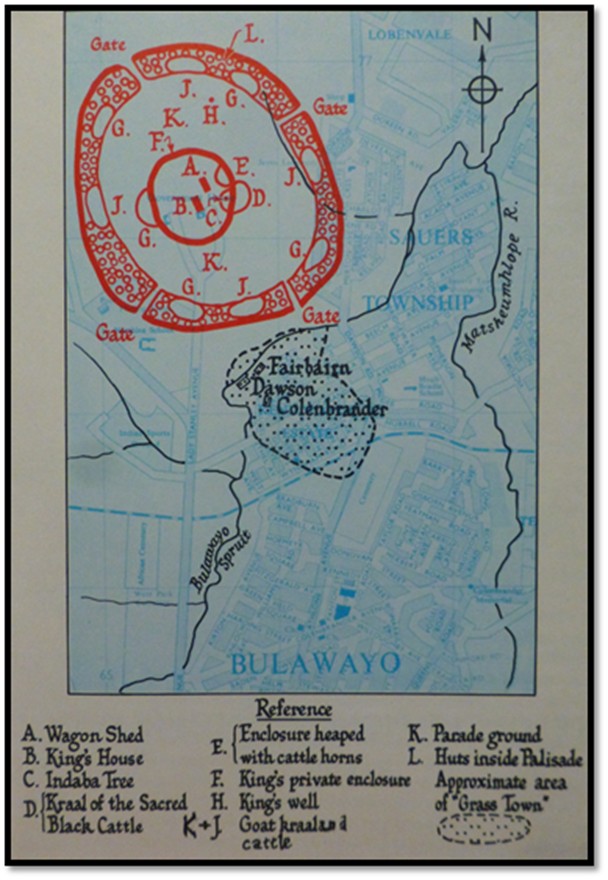

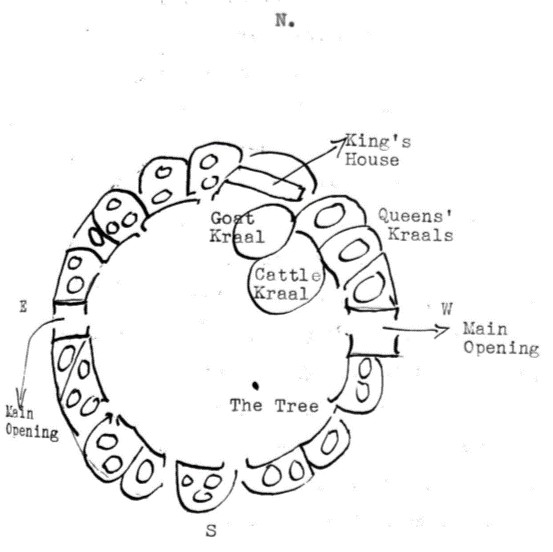

We outspanned outside Dawson's[19] place. I was about 21 or 22 at the time. Next day we proceeded to the King’s kraal on the site of the present Government House. (There was no tree there that he held court under. There was a tree towards the northern end of the whole kraal; but it didn't denote anything. That tree was afterwards cut down)[20]

Loben always sat on his wagon box or else on a chair on the ground. He had one of the Players Navy Cut folding chairs, that I gave him subsequently. He came down to my wagon one day and sat on it and I asked him if he would like it.

In approaching Lobengula you gave him his titles: “Kumalo! Bayete! or Nkosi!” and you shook hands with him and sat down. You sat on the ground and you didn't speak to him until he spoke to you. He knew all about you beforehand because you had to send up runners from Tati to ask, ‘for the road.’ You sent to Dawson or some other white man you knew, who would go and ask for permission for you to come. We never took our hats off to the King. That wasn't a native salutation at all.

From Dawson's store where we were camping to the King’s kraal was only about 700 or 800 yards and we walked across. My father, Dawson, Fairbairn, Usher and the other white people all went up together. The King was sitting on the wagon box in front of his wagon. He had a full-tent wagon.[21] We went up to him, gave him his titles and shook hands and then went and sat down on the ground. He asked the usual questions he always asked strangers: where you had come from, what you had come for, and your name and where you were going. You could not go further than Bulawayo unless you got permission.

Traders at Bulawayo: James Fairbairn and James Dawson

We all brought presents of some sort. We used to bring half a dozen cases of champagne. He drank some and his Queens used to drink a lot. They would drink it all if they had the chance. Those Gazaland Queens used to drink gin like water.

We discussed no business the first time saying we had only come on a visit.

The King always gave his visitors beer. It was brought along in a billycan by a girl named Velagubi who handed the billy to us. Before she did so, she took a sip herself to show that there was no poison. The King himself never drank with us. I never saw him drink in front of us. He used to eat in front of us sometimes; but he never drank with us.

After that we visited the King nearly every day until we left. We used to go up just to have a chat with him.

After we left Bulawayo I went down to the Tati and stayed there until sometime in 1887. Then I went down to Kimberley for a change and afterwards to Cape Town.

Fry’s Mission to Lobengula on behalf of Cecil Rhodes to negotiate a mineral concession

I do not know how my first father first got the commission from Rhodes to get a concession. I think Rhodes must have asked him to do it. My father knew Rhodes well. In those days Rhodes was not looked upon as a very big man down in Kimberley.[22]

My father and I saw Rhodes in 1887 when he [John Fry] got back from Matabeleland and the Tati; and it was then that Rhodes said to us: “I have just completed the amalgamation of the French and Central Companies. I have made a million and my income is £80,000 a year. Spend that and more if necessary; but get a concession.”

After that we had to get things ready, get a wagon and wait for the rains to finish. My father had a written agreement by which we were to get £55,000 if the Concession was granted, provided we did the spade work.[23]

In the beginning of 1888, my father and I returned to Matabeleland to get the concession from Lobengula. My father told me that we were going back to Matabeleland on behalf of Rhodes and Beit. I had nothing to do with Rhodes then and I did not see him before I came up with my father.

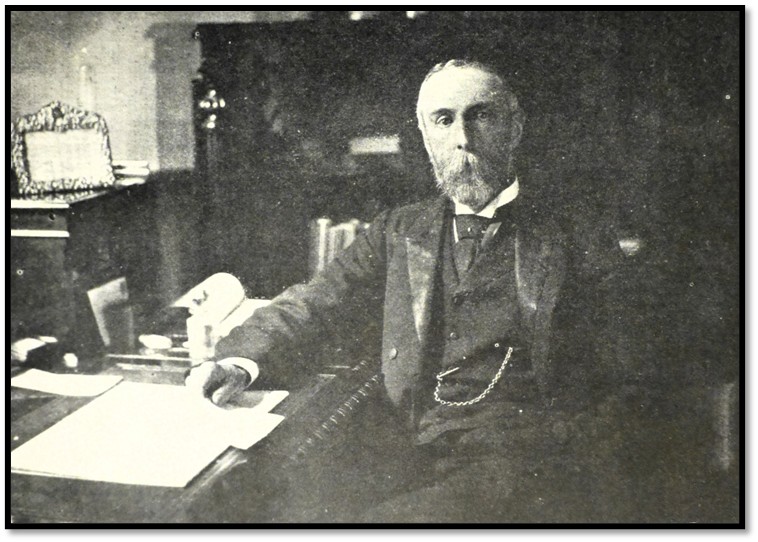

Cecil Rhodes Alfred Beit

We arrived in Bulawayo after resting the cattle for a week or so at Tati. Sam Edwards came up with us. He was always coming up to see the King as he represented him at Tati. He was his Immigration Officer, you might say.

I rode over to Hope Fountain to ask Helm to interpret for us, Helm said; “I would rather not, as the Missionaries are always accused of interfering in politics, etc.”[24] Then I got Usher[25] to interpret for us.

The first day we saw Loben we said nothing about wanting a concession. You had to work up to it in a very quiet roundabout way. It was no use trying to rush things.

Thompson[26] afterwards tried to get round Lotshe[27] to speak for him and when Lotshe was killed we heard from the natives that it was because he had been too friendly with Thompson. That was why Thompson got the wind up when Lotshe was killed.[28]

We used to see the King every day. We went up to show ourselves to the King. I cannot tell you when it was, but after some time my father put it to him that he wanted a concession of the country. He did not expect an answer then. One had to leave it to soak in as a native does not answer at once.

Before the King gave us an answer, and before my father had gone into any details with him, my father was taken ill. So he went to the King and said: “King, I am ill and I am going to die. I want the road.”

The King said: “Very well, you can have the road. It is only right you should go down and die among your own people; but you leave your son with me. I will be a father to him.”

After that he always made me trek about with him whenever he went in the country.[29] It was rather a nuisance. I think Loben was afraid that if white people died in his country, the Government might bring a charge against him.

Later, when I got word to say that my father was dying and that I must come down to Kimberley, I saw the King and told him that my father was dying and that I wanted the road to go down to him. The King said: “Yes, it is your place to see your father before he dies, but you must come back to me.”

Ivon Fry acts as Rhodes agent

My father returned to Kimberley, ill with cancer and I remained behind and acted as the agent of Rhodes and Beit.[30]

They looked upon me as a Matabele. I remember one day, after my father's death, Lotshe said to me: “Asalutu, when are you going to wear a ring?” meaning I was now a man. I replied: “when the King cuts my ears” and turned it off that way. Asalutu was my native name.

I put the question to the King: “What about the concession?” and the King said: “Gashle.”[31] Usher was my interpreter. I was paying him £300 a year.

Between the time my father left and I went down, Moffat[32] brought up some money for me, about £600 and never said a word about it. When I went to Moffat and asked him why not given it to me, he said: “I did not consider that a young man like you should be entrusted with £600.”

Whenever I required money I simply wrote to Rhodes personally and the money was sent up, usually by Dr Harris,[33] who was one of Rhodes’ jackals.[34] It was just before I left for Kimberley that Rudd, Thompson and Maguire turned up. I remember they had no food and I supplied them. When they found that my father had gone down and there was no chance of his recovery these people rushed up.

Dr Rutherfoord Harris the Company Secretary of the British South Africa Company at Kimberley

I was about 21 at that time.

Thompson said to me: “Fry, we know what you are here for and who you have come for and we are on the same errand. So if you get the Concession, we will come in on it. And if we get the Concession you come in on the other hand. Therefore, do not let us work against each other.”

I did nothing then because I had got my promise from the King. I understood that when the King said “Gashle” he meant that I was to wait before bringing the papers up to him.

I left for Kimberley about a week before the Rudd Concession was signed.[35] I know it must have been about a week, because after I went down, Rudd followed on. It might have been a month, but I do not think so. I must have had an inkling of the concession, because I remarked to my father on his deathbed: “Where is that agreement between Rhodes and ourselves?”

My father was in Kimberley more than a month before he died. He must have left Bulawayo about the end of September, or thereabouts. He died about the middle of November in Kimberley Hospital.[36]

After my father had gone down (it might have been two months after) I received a letter saying he could not live. I left for Kimberley about a week before the supposed concession was signed.

Fry leaves Bulawayo for Kimberley

There was a German count here, Count Sweinitz [Schweinitz] and Baron Crane. He had two titles. He was the son of the German ambassador at St Petersburg. Just at that time there was nearly war between France and Germany and he wanted to hurry back, so he and I left here together. The German Baron had been shooting in Matabeleland with a man in charge of his wagons.

We travelled quickly with relays of trotting oxen. We had post stations all the way down where we got relays of oxen. The system was in existence and I think the traders clubbed together to pay for it.

At Mafeking, we charted a post-cart and got to Kimberley on Sunday night. From Mafeking to Kimberley took about four days. I got there a week before my father died. I went to see my father and asked him where all the papers were, especially the agreement with Rhodes and he said: “Bob Graham has got them.” That was our attorney. I said: “He's got all our papers?” My father said “Yes.”

A week after that, I went to Bob Graham's office with my mother and demanded my father's papers. Bob Graham gave us all the papers, except the agreement with Rhodes. He pretended to hunt high and low for it. He said: “I can't find it.” And I never saw it from that day to this. The consequence was that I never got anything out of Rhodes as I should have.[37] Graham was a school fellow of my father's and we trusted him implicitly. We always thought the agreement would turn up. There was nothing more we could do. But I believe now that he sold it to Rhodes; because every time I met Rhodes afterwards and demanded a settlement he told me to “bring my agreement.”

We had done the spade work for the concession and the wording was that “in the event of the concession being granted” we were to get £55,000. Graham was an attorney in Kimberley and a member of the Club. He would have known Rhodes like everyone else.

Letter from F. W. Usher in Bulawayo

While I was down in Kimberley, I received the following letter from Usher, which goes to prove my claim on Rhodes. Usher called his place ‘Bug Villa.’ The farm he called Labouchere, after the editor of Truth magazine. The name is now changed to Fort Usher.

Matabeleland

Bug Villa

Feb 16, 1889.

Dear Fry,

I wrote you last month and am surprised that I have not had an answer from you. I had a letter from you by last post; but it did not bear on what I wrote you, so you could not have received my last one. Rudd’s party have your wagon here and they want the oxen too, but I told your boy not to give them up. I don't see why they should jump on everyone. You must let me know what to do in the matter. Am I to give up all to them and who is to pay your boys? You must write me fully all about it.

In my last letter, I told you that the King said your claim was good and that the King had not granted a concession of his country to Rudd's party. They are with the government party and the missionaries have tried to practise a fraud and they have been found out sooner than they wished.

The two Devils Rudd left behind [Rochfort Maguire and Francis Thompson] are accused of bewitching the waters[38] and are in anything but favour with the people and the King. I think you will be very foolish if you give up your claim or promise of the King’s.

The little dance is over and the big one will be in a few days.

The natives are not very civil and shout openly that the white people want to bewitch the King. I wish the dance was over. I think there will be a trial after the dance of some of the Devils and I will make it hot for some of those who have caused all the trouble here.

I am hard up for stuff[39] and there is none to buy here.

Hoping soon to hear good news from you.

I am yours faithfully,

W.F. Usher.

Meeting Rudd in 1889

When I met Rudd in Johannesburg somewhere in the beginning of 1889, he said to me: “Fry, I wanted you to take over our transport to Bulawayo.” But Rhodes would not hear of my coming into the country again. That was long before the Occupation Column.

Rudd told me then: “When the King agreed to our concession. He said Fairbairn and Fry had to be provided for. But don't look to me for it. You must look to the other side.” (i.e. Rhodes and Beit) Rhodes would not agree to my coming back with the transport. I had a lot of influence with the natives here.

Thompson drew up the supposed Concession. When Rudd looked through it, he saw that Thompson's name appeared on it. He then said to Thompson: “Remember, you are only a paid servant of ours.” Thompson replied: “I am well aware of that, but if the King signs it and my name does not appear, as we always talk about each other as ‘brothers’ it will only cause complication again and may delay the signing.”

Rudd let it pass at that. Afterwards, when the whole thing was over, Rhodes said to Thompson: “I am giving you £10,000 for the part you played in this.” Thompson said: “£10,000! Why I am one of the original concessionaires.”[40] Rhodes then went to Rudd and said: “You allowed Thompson's name to appear on the Concession and he demands £200,000, so you would have to drop two units.” That caused the row between Rhodes and Rudd. They never had anything to do with each other afterwards. I got this whole story from Rudd himself; I think it was in 1889. Rudd had a lot to do with everything after that, as a shareholder in the company, but he did not have much to do with Rhodes.[41]

Ivon Fry reiterates this after being confronted with Matabele Thompson’s book.[42]

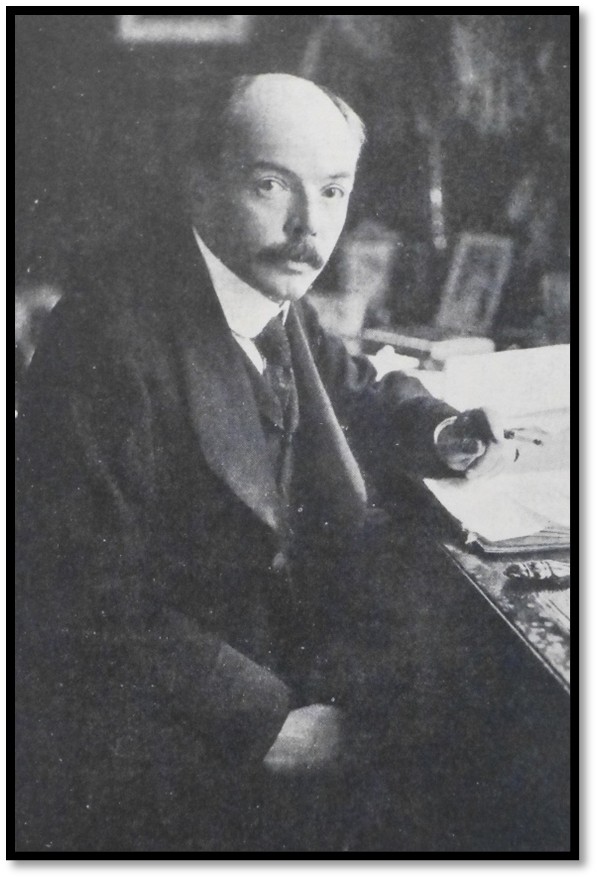

Charles Dunell Rudd

Rudd distinctly told me that Thompson had only come as the paid servant of the syndicate and that it was by putting his name on the concession that he got them to recognise him as one of the concessionaires. Rudd told me the story I have told. [This is hard to believe; see Footnote 40]

I left Bulawayo before the supposed concession was granted and I got to a place called Lemoeni Pan, where there was very little water left. I filled up our containers with water (we used to have little wooden kegs) and our cattle practically finished off the water. I then put a stick in the ground with a note in the cleft saying: “water north east, follow large footpath.”

Rudd was bringing back the concession. He reached Lemoeni and found my note. He buried the concession and what money he had in the sand under his wagon and tried to follow on the instructions with his mules; but the mules were very thirsty and kept going in all directions. Rudd, trying to get them together, eventually collapsed. Some natives found him, gave him water and took him back to the wagon. The natives gathered the mules and took them to the water and Rudd was able to set off again.

He said to me afterwards: “I got your note, Fry, but I could not get the mules to be driven along properly.” He did not get lost. He could not get lost on the main road. It was not Bushmen, but Bechuanas that found him. [more disagreements with Thompson’s account]

Subsequent attempts to upset the [Rudd] Concession

In the early part of 1889 a man came to me and made me an offer on behalf of principals of £2,000 cash and all expenses paid to fit me out if I would go back to Matabeleland and get the concession from Lobengula which had been promised me. He came to see me again next day and then he told me that his principle was Barney Barnato[43] and that the object was to upset Rhodes’ Concession, because Barney Barnato was up against Rhodes.

I met John X. Merriman[44] in the street and told him what had occurred and he told me that Barney Barnato was a scoundrel and that my father had nothing in common with him and advised me to have nothing to do with it. So I turned it down.

Sometime after 1893 Ikey Sonnenberg,[45] a well-known character, approached me to join him in an expedition to Matabeleland and find Lobengula and take him down the Zambezi and through Delagoa Bay to the Transvaal. The Transvaal government, he said, wanted him there to upset the concession.

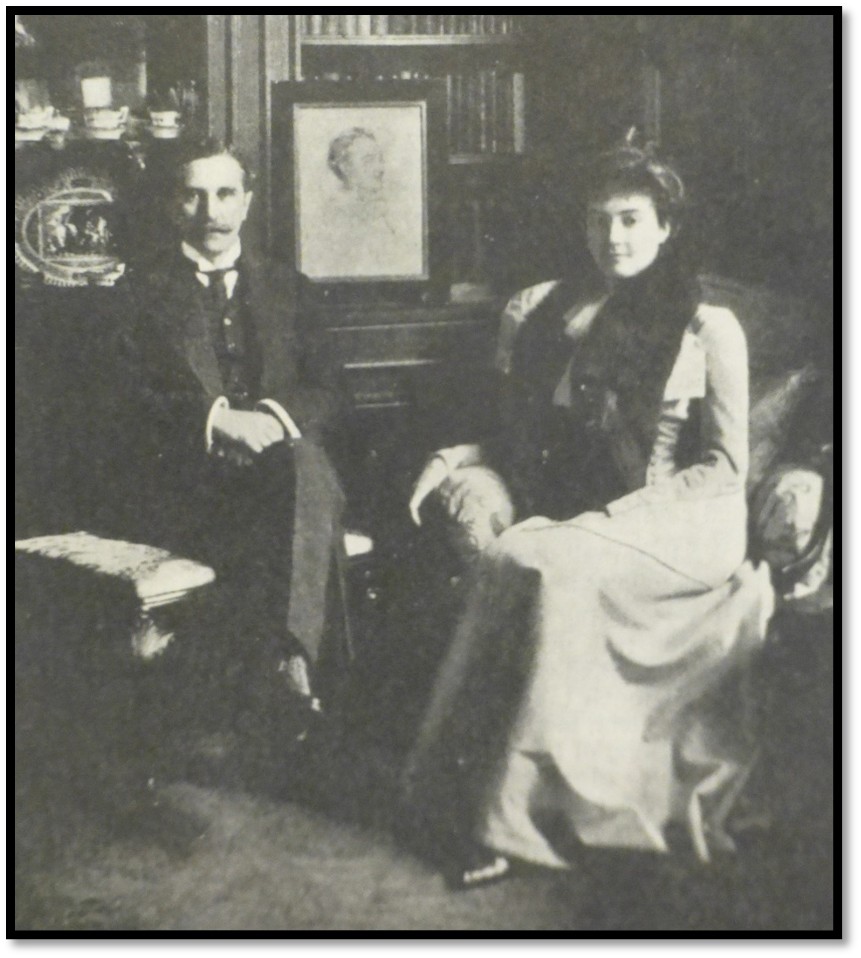

James Rochfort Maguire and his wife, note the sketch between them of Rhodes by the Marchioness of Granby

Fry goes back to Bulawayo to quieten the opposition to the Rudd Concession

While I was in Johannesburg in 1889, after Rhodes had refused to allow me to go back, I got a letter from Harry Curry, Secretary of Gold Fields South Africa Ltd, telling me I had to return to Matabeleland under the terms of my original agreement[46] and there to do nothing unbeknown to the company representative.

When my father and I arrived, we did not divulge our plans in any shape or form and we were always friendly with the local traders. They knew that we were out for a concession, but not that we had come to get the whole country. It was our plan to get a concession of the whole country for Rhodes, but we did not tell them that. They thought we were just after a concession.

My relations with the traders were very friendly, that was why I was sent back afterwards to quieten the opposition, which I did. The traders said they would not agree to the Rudd Concession because I had been promised a concession by the King and I had to be provided for before anything else happened. They knew well enough that if my concession had been granted in the first place, they would all have got something out of it indirectly. The reason why Fairbairn, Dawson, Usher, Tainton and the others were all so hostile to the Rudd party was that they all had in their minds the hope of getting a concession themselves.

I came up; it must have been about March or April, perhaps May in 1889. I know it was the dry season. I came up from Johannesburg with a wagonette and mules. When I met them all up here, I advised them not to kick against the pricks, but to get what they could out of the Chartered Company.

Shortly after I arrived, there was a meeting between Reverend Helm[47], John Moffat, Thompson and the traders - we were all there, with the King. One of the white traders asked the King the question if he knew that he had given the whole country away to the Rhodes party and the King said: “No, I want that paper back,” and Thompson said: “Yes, as fast as horses can go I will bring the paper back.”

In the meantime, before the concession arrived, Lotshe the Commander in Chief had been smelt out and killed and then Thompson bolted.

I was not there when the indaba took place with Helm; but I was there at another indaba that took place with Moffat and the other white people after my father's death. I suppose that would be in 1889. It was at the King’s [kraal] I forget what they discussed, but it must certainly have been about the concession because it was the one subject about which we were all constantly talking. The whole thing centred on the fact that Rudd's party had got the monopoly of the whole country.

I heard afterwards that the indaba with Thompson and Helm[48] and all the white men took place at the King’s over the concession, Helm and Moffat were present and Helm fainted with the heat. The others used to sneak off out of the back of the meeting and drink beer, but Helm and Moffat did not.

I stayed here for a few months and then went back again. The Chartered Company paid my expenses, but they paid me nothing for myself. I looked at it that I was to return to the country under the terms of my original agreement, and I was working for that.

I went back to Johannesburg. Rudd was away in England then. I think I went to Harry Curry and I am not certain whether he referred me to Rhodes or anyone else. Anyway, I was put off some way or another and I never worried any further. I was a young man dealing with a pack of thieves.

All the guns sent out by Rhodes had defective sights.[49] When Rhodes was asked why he sent the Matabele guns, his answer was that the natives were more dangerous with an assegai than with a rifle. I never tried any of the rifles myself; but that was the story current in the country and judging by the way the natives shot afterwards I should be inclined to believe it was true.[50]

The death of Lotshe who is blamed ‘for giving away the country’

Lotshe was not the Prime Minister, he was the Commander in Chief of the army. I was here when Lotshe was killed. Lotshe was not killed in front of Thompson. Thompson is lying.

Lotshe had been with the impi at Lake Ngami and there they made a mess of things. He was blamed by the King and the Indunas for having made a mess of things. The expedition to Ngami happened after my second visit to Matabeleland, when I came with my father to get the concession. It was probably in 1888.

Johnny Stromboom,[51] a Scandinavian, who had a store at Lake Ngami was away down at Mafeking at the time of the raid and a man by the name of Steele was in charge of his business. When the impi turned up Steele disappeared.

The Matabele got badly beaten there by Moremi’s people. Moremi’s people left a lot of canoes on the banks of the lake which the Matabele got into and could not work. Moremi’s people then fired on the Matabele from the reeds. The Matabele jumped out of the canoes and got drowned or eaten by crocodiles.

They then looted Johnny Stromboom’s store [in 1885] and came home and had a bad time generally.

Lotshe was accused of being to blame for the Lake Ngami failure and of being a great friend of Thompson’s who had always tried to get at the King through him. The Indunas brought a charge against Lotshe accusing him of having been too friendly with Thompson. He was smelt out and sentenced to death. Lottie was killed at his village and all his things were confiscated.

I dare say there was a smelling out of Lotshe’s people, but it is not true, as Thompson says, that they killed the women and children. The women and children were brought into the King’s and distributed as always.

The flight of Thompson, the Chartered Company’s representative at Bulawayo

Thompson, in the meantime, was over at Hope Fountain and did not hear of Lotshe’s death until two days afterwards. He was driving over from Hope Fountain with a cart and four horses to his camp on the Umgusa [river] and on the road he met a native with a youth driving a cow and a calf. The native stopped him and said: “White man, the King says, you must give me a rifle for this cow and calf.”

Thompson told him to go to his camp. In the meantime, he came on to Dawson’s store, where I was, got out and asked us if it was true that Lotshe was dead. We replied: “Yes, he was smelt out a couple of days ago.” Thompson said: “Who is this native who says the King says I must give him a rifle for a cow and a calf?” We said: “Take no notice of him. He tried to sell the cow and calf to us too for a rifle.”

Thompson then drove off. Very shortly afterwards I heard a horse coming towards the gates and there was Thompson, bare-back on the horse using a riem through its mouth for a bridal. When he saw me, he said: “Bring me a bridle like a good chap.” I put my head in the door and shouted to Dawson: “Here’s Thompson. He wants a bridle and saddle.” Dawson brought out a bridle and saddle and Thompson put the bridle in the horse’s mouth without taking out the riem. I said: “Hold on, you've got the riem in the horse’s mouth.” He removed the riem and put the bridle on with the curb in the horse’s mouth with the bit. I said: “Hold on, you've got the curb there.” He said:” It doesn't matter. It makes no difference.”

When he mounted the horse, he turned round and said: “What time do you fellows go to bed?” We replied: “About 8:30pm” He said: “I'll see you then.” So then we asked him where he was going. He said: “I am going to Hope Fountain to tell them the news for fear they may be anxious.” When Thompson rode off, I turned to Dawson and Fairbairn and said: “If Thompson bolts, I won't be surprised.” They pooh-poohed the idea. I said to them then: “You don't know Thompson as I do.” I then told them the story of how Thompson had seen his father killed and been wounded himself in the Griqua Rebellion of 1878.

The next day, Dawson went down to Usher’s Farm and then round by Hope Fountain and asked where Thompson was and he was told that Thompson had left the day before for Umguza. Then Dawson knew he had bolted as he had not been back to Hope Fountain.[52]

The following afternoon the wagons came in with loads from Mangwato and a native showed me a coat he had picked up in the road and in the pocket I saw letters addressed to Thompson. I said: “This is Thompson’s coat. Where did you get it?” He said: “At the Khami” [river] I said: “Did you see Thompson?” and he said: “Yes, Thompson passed us on horseback.”

We heard afterwards from Tom Maddocks[53] that Thompson rode to the Ramaquaban [river] and the horse was knocked up and he tied it up to a tree and ran and walked the 19 miles to Tati, shouting when he got there: “Span in! Span in.” Tom Maddox told us that he came out of his house and said to Thompson: “What’s the matter?” Thompson said: “The Matabele are after me.” Maddocks asked. “When did you leave?” and he replied: “Yesterday afternoon.” (It was a wonderful horse) Maddocks replied that the Matabele could never get there. Nevertheless, he sent for the oxen, inspanned an empty wagon and sent it down with Thompson to Mangwato with relays of oxen on the road and they did it in three days. They did about 50 miles, I think. In those days we used to have trotting oxen for the post-carts. Maddocks did not go with him. He was not afraid of the Matabele. Nobody was afraid of the Matabele except Thompson.

At Mangwato, Chapman put him in a cart and drove him off to Mafeking, where he met Dr Jameson and Dennis Doyle. Jameson asked where he was going and Thompson said the Matabele were after him. Jameson said: “You had better go back with us.” Thompson declined unless they insured his life for £10,000 which they did. Then all three came back again.[54]

The Matabele become hostile to the local traders resident at Bulawayo

In the meantime, the only thing that occurred in the country after Thompson had bolted was that the natives kept away from us. Not one came near us to trade, or anything else. We thought the natives might attack us, so we took precautions. Dawson had a flat-roofed house made of unburnt bricks – it was really a store room in which he kept explosives, gunpowder, dynamite and cartridges. We put in a supply of water and whatever we could in the shape of tinned stuff and made-up our minds that if we were attacked, we would put up a fight for it, and should the natives come onto the roof to try to break in, we would blow the whole thing up, ourselves with them.

Bulawayo and White Man’s Camp from Bulawayo, Historic Battleground of Rhodesia, P52

Dawson, Fairbairn and Usher said to me: “You are in a different position from us, so go over to the King.” I rode over to the King’s at Intotini on the Umguza and the first person I meet was old William Mzizi.[55] Mzizi said to me: “Thompson has run away?” I said: “Yes.” He said: “Can Thompson bring an impi back with him?” I said: “No, He is only a Maholi among the white people.” He said: “Is that true?” I then spat on the inside of my forearm and rubbed the two forearms together above the elbow and said: “Noenisili” This was a form of taking an oath among the Matabele. Another method was putting your finger in your mouth and snapping it in the air.

I then went to the King, and before giving the King an opportunity of saying anything to me, I said: “King, Thompson has run away.” He said: “Yes, so I hear.” He asked me the same question as Mzizi: “Could Thompson bring back an impi?” I said: “No!” So he said: “Lungile” [sweet, pleasing] and after that the natives turned up again. When Thompson returned with Jameson and Doyle, they went to interview the King and the King said to Thompson: “You ran away like a rat.” Thompson said: “No, I went down to meet my friends.” The King said: “Amanga!” (lies)

Dr L.S. Jameson

How could Thompson have heard the killing of the people of Lotshe’s family when Lotshe’s kraal was Lord knows where. And how is it that we did not hear it? Thompson's camp was on the Umguza River, just about where Sauers township stands today. It was not on the Umguza proper, but on the spruit that runs down below Government House. We called all that portion round there, the Umguza. It was not far from Dawson’s store, but it was some way lower down the spruit towards the Umguza River. It may have been a mile and a half or two miles. I never noted the distance.

No natives in the country owned horses except William Mzizi and the King; so I do not know who that native on a grey horse that Thompson refers to could have been. It was funny we never heard anything about a crowd of young Matabele in war dress approaching Thompson. Thompson is lying.[56] The King would no more think of killing a white man, then he would of flying, for fear of bringing the British Government on him. It shows you how he lies that he does not mention that he came to Dawson’s store where we gave him a bridle and saddle. He came from Hope Fountain in a cart and four horses but he did not cut the horse from the traces; he outspanned it.[57]

The reason why the natives thought that Maguire was ‘tagati’[58] was the fact that he went down to the river to wash armed with tooth powder and toothbrush and other toilet requisites. He was a bit of a dandy.

I do not know of any threat by the white men to shoot Thompson. I was not in Bulawayo when the first consignment of rifles arrived.

Curry’s letter

Afterwards, my brother, who was working at Gold Fields South Africa Ltd tried to secure a copy of the letter written to me by Curry, because it acknowledged my original agreement; but they would not allow him to examine the records of correspondence – the letter book containing the copy. I remember Curry's letter because at the time I had never heard of the word ‘unbeknown’ before and looked it up in the dictionary.

Meeting with Rhodes at Kimberley, 1888

The first time I met Rhodes, after my father's death, was at the Kimberley Club at the end of 1888. I then told him that I was prepared to accept £10,000 as I wanted to send my mother, brother and sisters to England. Rhodes said: “I haven't got £10,000.” My reply was: “You have just given £10,000 to the Parnell Fund.” He said: “What do you know about the Parnell Fund?” and then: “I won't settle with you until I take Matabeleland.” He added: “Bring your agreement.” I had already suspected that he had bought the agreement from our attorney Bob Graham and my suspicion was confirmed by his remark and by the fact that the attorney, who was insolvent before, had now retired to England and never returned.

The second time I met Rhodes was at Beira when we were building the railway, I was contracting on the Beira Railway. This was during the construction of the line and we laid the earthworks. Rhodes was with Colonel Machado, Governor of Mozambique. I approached him as he was walking along the foreshore. I said: “I would like to speak to you.” He said: “What is your name?” And when I replied: “Ivon Fry.” He sort of hopped around and said: “See me on board the Tyrion,” the English ship[59] he was on [the Pungwe river] this afternoon. I said: “No, we are here on neutral territory and Colonel Machado knows me.” Machado answered: “Yes, I know, Mr Fry very well.” Rhodes said: “I am going up the river and I'll be on board the Tyrion this afternoon.” Then I walked off and in the afternoon I went on board with Captain Andrews, the agent of the railway and general factotum at Beira for the Chartered Company.

Rhodes was surrounded by the captain of the ship, the first mate, the bosun and several others. I think he thought I wanted to shoot him. I had not made any sign to give him that idea, but he knew that I had agreements against him and perhaps he did not know what might happen in Portuguese territory. After I had said good afternoon to him, he said: “What you doing here?” I replied: “I am on the railway.” He replied: “This is no place for you.” I said: I am well aware of that and if you settle with me, Mr Rhodes, I promise not to remain here.” I meant that I was not accustomed to doing the work I was doing on the railway as I had been brought up for something different. Rhodes said: “I’ll not settle with you until I take Matabeleland.” He said: “You go ashore and I'll give instructions to Captain Andrews.” When Andrews followed me ashore afterwards, I asked him what Rhodes had told him. Captain Andrews then told me that Rhodes had instructed him to see me on board ship and send me down to Natal and to give me £25. I told Andrews he could keep the £25, actually, I told him he could stick it up.

Rhodes could not get rid of me when he came into Bulawayo after the Matabele War, he found me here again. I had joined the Victoria Column and came in with them. I did not speak to him then. But he knew that I had a lot of influence with the natives and so he insisted on my taking down the remains of Allan Wilson's party to the Zimbabwe ruins and I was kept there for two years as curator.[60]

I join the Pioneer Column in 1890

A little while after Jameson came up with Thompson and Doyle, I left the country - when everything was quiet. I had a letter from Jameson to Curry in Johannesburg. I had done my job and pacified the traders and that finished my part as regards the Rudd Concession. I cannot say how long after Jameson came up that I left. I did not return to Matabeleland until 1893 with the Victoria Column. In 1890 I came up to Mashonaland with the Occupation Column. I caught them up at Tuli.[61]

I was coming up to Matabeleland with two salted horses for Dawson and Fairbairn in case they wanted to do a bunk. In Palachwe[62] I met [Dennis] Doyle, one of Rhode’s jackals and he asked me where I was going. I told him and he told me that Jameson did not want me to go into Matabeleland. He asked me to hand over the two horses to him and gave me another horse and told me to follow after the Column. I think they did not want me to get back into the country because I had a lot of influence, especially with the King. I did as he asked, because I wanted to join the Column in the hope of being in any row going.

I caught the column at Tuli and reported to Frank Johnson and was attached to the transport under George Burnett[63] and I went into Salisbury with the Column.[64] After the occupation, I went down to the Hartley Hills, prospecting with some of the other pioneers.[65] Heany[66] turned up at our camp one night and asked me and several others if we would go into Salisbury and there we would get three months’ rations and more ammunition.

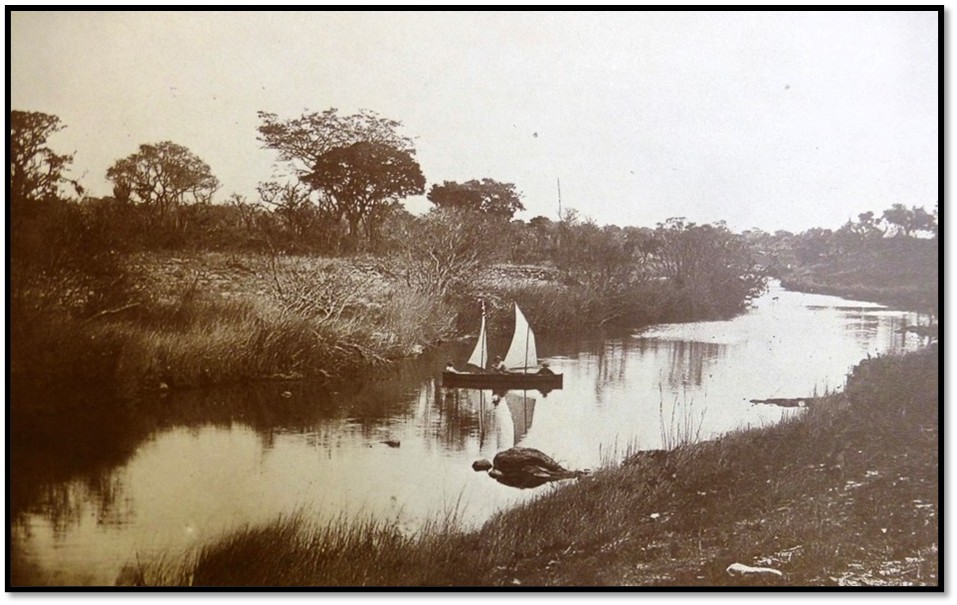

Ellerton Fry. The Berthon boat that ‘Skipper’ Hoste, Tyndale-Biscoe and Ivon Fry sailed on the Umfuli (Mupfure) river

How we gained Manicaland from the Portuguese

When we got there, we were told to trek down through the veld due east until we got to a place called Umtali and occupy the country there. I stayed in Umtali[67] until the railway started and then I went down contracting on the railway. People have now begun to come into the country. Sometime after the occupation of Mashonaland and before the railway was started, an old Jew peddler was coming into the country and he had a lot of watches of a particular make. As his people never heard of him again they instituted inquiries through the authorities. It was then discovered that a Hollander was selling these watches. The Hollander was arrested and tried for murder and hanged in Salisbury In the old original Fort.[68] Everybody sat round on the walls of the Fort and watched him being hanged. I was not there as I had just left Salisbury.

Sometimes afterwards, a man by the name of Mackenzie had something stolen by Xhosa boy in his employee. The boy cleared out and after a time Mackenzie caught him as he was travelling along on his wagon with his wife and child and a sick friend. He took this Xhosa into the police tied up in the front of the wagon. When they came to outspan the Xhosa complained that the reims were hurting him. MacKenzie loosened the reims a bit. On the inside of the wagon, hanging up, were the guns and this native grabbed a gun, shot MacKenzie, shot his wife, who fell over the baby and shot the sick friend who was on a stretcher at the back of the wagon and then bolted.

He was caught by the police afterwards and lodged in the Salisbury gaol. A mob from the kopje-side[69] went across and broke into the gaol, dragged out the native and were going to lynch him. A man by the name of Brewen, a baker on the kopje-side, brought his donkey cart and a rope with him. It was towards sundown. Jameson heard what was going on and came rushing down and said: “Hold on, boys let me have a hand in this.” Having gained their attention, he addressed them, saying: “You have all got properties in the country and if you lynch this native, nobody will invest money in the country because they will consider there is no law and order. So hand him back, and I promise you will be tried and I have no doubt found guilty, and then you can see him hanged.” The native was then taken back to the gaol and handed over to the gaoler, with a parting remark by Brewen telling the gaoler whose name was Law that if he did not bring the rope back the next day, he would be hanged. I was there and saw it all. I went along to look on.

Fry at the battle at Massi Kessi (Macequece) with the Portuguese

When we got down to Umtali, the Portuguese and French, who had been working round there had cleared out.[70] But the Portuguese sometime afterwards came back to Macequece with a baby army they brought out from somewhere.

They collected these young Portuguese boys in Portugal and they had about 300 Angolan natives with them. The Portuguese were so afraid of the natives generally that they used to capture natives in Mozambique and send them round to Angola where they could not escape and vice versa. We always called these natives ‘sepoys.’ Once upon a time when a Portuguese gunboat put into Delagoa Bay, every native in the town disappeared for fear of being collared and shipped away.

The Portuguese brought this baby army to Massi Kessi [Macequece] with the object of recapturing Manicaland from us. The government sent down a white flag to them and a message saying that there was a modus vivendi until May the 16th. i.e. that there will be no move until May the 16th. This was on May the 11th, 1891.

We had already taken up a position overlooking Massi Kessi[71] under Colonel Heyman.[72] I was one of the Troop. We had a nine-pounder [seven-pounder] with us. About the following day, the Portuguese advanced and fired at us. But all their bullets went high and we drove them back with Martini’s.[73] After they had retreated into Massi Kessi Fort we took one prisoner and a wounded sepoy, who afterwards died on our hands. None of us was hurt in the action. Then we elevated the nine-pounder and fired at the Fort. One of the shells struck a hill and bounced into the Fort, and the next morning there were no Portuguese left in it. A month afterwards, I followed down to Beira and I saw sundry, freshly made graves on the roadside which I took to be the graves of the wounded who had died.

We attempt to gain a land corridor to Beira

Then we got orders to take Beira. Rutherford Harris sent a dispatch from Kimberley to Jameson saying: “Take Beira.” Jameson sent back the answer: “Balls, take it yourself.” All we knew about it was that we were told to proceed and that we had to go and take Beira. We got as far as the next place after Vila Pery (now Chimoio) and then we got orders to turn back. I remember now the place was Sarmento.

There was a reporter from the Times who went down with us to capture Beira. He was the last man bringing up the rear. One man saw him tying up his boot lace and that was the last ever seen of him. We presumed a lion had jumped out and got him. We had a hell of a hunt for him because he had a sixty guinea watch with him and I thought the lion would not have eaten that.

I think we must have started off for Beira first and then come back to Umtali. Then the Portuguese came up with their army, and then we took Macequece. The Portuguese retired to Chimoio and built a stockade. We went down to attack them. Before we attacked, Major Sapte[74] sent into message out to us telling us not to do anything as he had come up from Cape Town for the British government to enquire into the business. So Billy Finds [The Hon Eustace Fiennes] a man by the name of du Maurier,[75] [Morier] whose father used to be British ambassador at St Petersburgh) a man by the name of Stuart and myself went down - Fiennes to interview Major Sapte and we really to escort him.

We heard afterwards that what happened was this. Before we got Sapte’s note we had captured an Angolan sepoy doing sentry duty and frightened the life out of him, disarmed him, and let him go. When he reached the Fort every bugler there began blowing a different call. Major Sapte had in the meantime arrived at the Fort from the opposite direction (from Beira) and when he heard all the commotion he wondered what it was. The Portuguese told them we were going to attack. He said: “I must get out of this. I don't want to be shot by my own people.” But the Portuguese said: “No! No! we will surrender.”

Sometime later I went down with Maritz contracting on the railway construction to Mpondo on the Pungwe River. We took on contracts from there right away up to Chimoio. When I go back sometime later to Umtali I met Jameson who asked me where I came from and when I told him, he said: “You have come through the valley of the shadow of death!” The men died like flies on that railway. There was no doctor and no medicine. They used to say afterwards there was a man under every sleeper.

When I came back from the railway construction, I went up to Salisbury from Umtali and Jameson appointed me as mining commissioner at Hartley. But before I could take up the post, they sent me to Fort Victoria as Magistrate’s clerk, because they wanted a shorthand typist from there named ‘Lucy’ Drew to come up to Salisbury. I was sent to relieve him. Then the war broke out.

The Fort Victoria Incident

I left Salisbury by post-cart drawn by trotting oxen for Fort Victoria. When we got to the Shagashi river (the last outspan from Victoria) a man by the name of Brown,[76] who was killed with Allan Wilson later, rode up and warned us to get in as quickly as possible as the Matabele were raiding the country. As I got to the town I saw a man on horseback with his wife and child with him on the same horse going into town.

The Fort in Victoria had wagons drawn into it and the women and children were all in the Fort. The cattle had been sent out to Great Zimbabwe. I saw no Matabele. In the course of time, horses from the Transvaal were brought up from Tuli way. In the meantime, Jameson had arrived from Salisbury, and he sent out and told the Matabele Indunas (Manyao and Umgandan) to come in; he wanted to speak to them. The Indunas came in and Jameson went out to meet them with Napier.[77] Everybody in the Fort was hanging over the wall looking on. Jameson approached the Indunas and asked them through Napier what they meant by killing the Mashonas and raiding the country. The reply was: “We have come to punish them at your request.”

Jameson said: “If you have any case against these natives, you must bring them before our court.” Their reply was: “We don't recognise your courts, and this is Lobengula’s country!” Jameson turned to them and said: “You have got to cross the border by 2pm or otherwise I'll drive you across!” Jameson then left and walked towards the Fort leaving Napier behind. Then Napier ran after Jameson and said the natives don't know what is meant by the border. Jameson turned round and said: “They know where the border is.” Napier went back and told the natives what we considered the border[78] (I have forgotten what it was) and pointed to where the sun would be at 2pm. The indaba took place, it might have been about 11am, or so, because Jameson had arrived that morning and he had to wait till the natives turned up.

A little after 2pm, Lendy[79] told every man who had a horse to mount. As Harry Ware was drunk, Argent Kirtin (who was killed with Allan Wilson) said to me: “You take Harry's horse” and away we went after the natives. By that time the natives were retiring back to Matabeleland and as they had not reached the border, we dismounted at 300 yards and opened fire on them. When they tried to charge, we retired again. I think I only heard two rifle shots from their side. Then we went back to Fort Victoria. When we reached the town, the walls of the Fort were still crowded with people. Jameson came out and Lendy rode forward and said: “Doctor, you told me if I struck, I was to strike hard and I think I have accounted for 300!”[80] Jameson then turned round to the people on the walls and said: “I hereby declare war on the Matabele.”

The reason why the Matabele raided the country was that the natives down towards Fort Victoria had been cutting the telegraph wire for making bangles, not knowing they were doing damage. Lendy went down and punished these natives and took some cattle away from them, which were afterwards sent down to Tuli to Peter Heugh, the magistrate there, to sell. In the meantime, Lendy came into Matabeleland and met Lobengula on the Hunyani [Manyame River] in the hunting veld and complained to the King about these people having cut the wire. Lendy then asked the King to punish these people. Lendy like all these Johnny-come-lately's did not know the Matabele. The only punishment the Matabele knew was death. The King replied to Lendy: “You have taken away cattle from these people and they are my cattle. These people are only my cattle herds.” Lendy replied: “Very well, we'll get the cattle back.” The cattle was sent for and brought back to the Shagashi river. There they were kept for several months and never sent back to Loben. When the Matabele raided around Victoria, they took these cattle with them. Jameson wired to Rhodes and said: “I have declared war on the Matabele!” Rhodes wired back: “Read Luke so and so.” As Magistrate’s clerk, I saw the message.[81]

The 1893 campaign

When we joined up for the Matabele campaign in 1893, the conditions were five shillings a day and rations as far as the border and after we crossed the border, we were to live on the country and were promised half the loot and a farm each.[82] Before proceeding to invade Matabeleland, Jameson wired to the Governor of the Cape Colony,[83] saying: “I'm entering Matabeleland with some of the police to recover native women captured by the Matabele.” I may tell you that these women had probably been captured ten years before and no one knew their whereabouts; but that was the excuse he made for taking the police in with him.

The transport drew out to the Shagashi river and camped there and from there we proceeded into Matabeleland. At Iron Mine Hill, or Ntaba Insimbi, we met the Salisbury column and we travelled along to Matabeleland in two parallel columns and laagered at night. At the Shangani River, the natives attacked us at daybreak. We drove them out. There was a young Jew killed and a Cape coloured boy in our lot - the Victoria Column. Before this Ted Burnett, Ian Grant and Percival Swinburne had been out on patrol. They reached a small village of about four or six huts. Burnett had warned Grant to be careful of the Matabele here. Grant said: “They are only Mashonas!” They dismounted and a native from out of a hut shot Ted Burnett in the liver. Swinburne and Grant leant over him to look and the native fired again and put a bullet through Swinburne's tunic. They then fired at the native and wounded him and he got back into the hut. They went round and set light to the hut. The native was driven out and they shot him. This happened about the day before the attack at Shangani river (Bonko)

After that we had several small encounters, in one of which Grant's horse bolted right through the Matabele. The natives fired at him, wounded the horse in the leg. Grant made for a kopje and tied his horse up to a tree, took off his Stetson hat and waved to the natives to come on. He fired at the natives and they fired at him and at last he was killed. We got the story afterwards from a native who brought Grant’s watch in to sell. The natives stripped the body, tied it on a horse and took it to the nearest Induna. The Induna said he did not want a dead white man and told them to take him back where they found him. They took him back and tied the horse up to a tree and left it there to die, with the body on its back. (This was the same horse that Thompson had bolted on. We called the horse ‘Loben.’)

After the war was over, a native brought me a watch and when I opened the inside of the watch, I saw Ian Grant's name in it. I took the boy down to Dawson's and I told Dawson to close the doors and hang on to this native and not to let him escape. I took the watch to Jameson. They sent for Grant's brother, who recognised the watch at once. We cross examined the native who said he got the watch from his brother, who had got it from the man who died with the horse. They then inspanned two Cape carts and the native went with them to show them the remains. The bones were brought back and buried here in Bulawayo; but were taken up afterwards and taken to his home in England. The bones were found mixed up with the bones of the horse Loben in one heap. That was the end of the horse. He was a fine horse.

Originally, the horse Loben was brought up to this country by George (‘Ocht’) Viljoen. He offered the horse, which was then unsalted, to me for four trained oxen; but I had not got them to spare. He then went over to Inyati and exchanged the horse for some broken ivory and two slaves, a boy and a girl, with George Martin. The horse salted with Martin,[84] who sold it afterwards to Boggie.[85] It was too fiery for Boggie, so he exchanged it with Thompson. It was a company horse. I do not remember how it got to Victoria, but it was there when the horses were dished out and Grant was warned not to take it because of its habit of bolting ever since Thompson’s ride. On one occasion, Percy Inskip[86] was riding it and it bolted with him into the stable and Inskip ducked his head just in time under the door.

The alarm at Shangani was given by the Mashonas we had with us. I believe one went down to the river for water and did not come back. Then another went down and did not come and then, I think, a third went down and the Matabele jumped at him and he fired at them and gave the alarm. Then the Matabele came on and attacked the laager. It was all in the dark. It was about 3am, I suppose, 3am or 4am. It was still dark, I know.

Then there was the incident of White’s Run at the Bembesi [Egodade] on the way to Bulawayo. Ken White and some other fellow had to do vidette duty amongst some camelthorn trees. White had tied his horse to a tree and went over to speak to the other chap and when he looked round, he saw a Matabele running for his horse. White rushed for him and shot him quite close to the horse. The shooting stampeded the horse, which ran to the camp. The other man on horseback went to White’s assistance and they argued the point. This fellow told White to hang on to the stirrup and to run for it and White said: “You go.” In the meantime, the natives were coming on. The other fellow was killed[87] through staying behind to try to protect White and White ran for the camp about half a mile.

We saw what was happening. There was one native just behind White with his assegai raised to strike; but he just could not get that extra yard. We could not train the machine gun on the natives because White was in the line of fire. The other natives were coming along some distance behind. So White whipped round and the native nearly ran onto his gun and he pulled the trigger and shot him. White swerved a bit doing this, and we opened fire on the Matabele. The other fellow had stayed behind to protect White and was pulled off his horse. There was a big battle at the Bembesi at this place, called White’s Run and we bumped the natives badly there. After that we marched into Bulawayo.

Dawson and Fairbairn and Usher[88] was sitting on the roof of Dawson’s store looking out for us when the Column approached Bulawayo. After Lobengula cleared with his people, these three went up to his house (the brick house built by Johnny Mubi) and looted it and blew it up with dynamite.[89] The huts were all standing just as the natives had left them. There was not one native to be seen in Bulawayo. There were any amount of dogs; we used to shoot them. They existed on the trek oxen that died. The natives had burned all the veld in front of us and our cattle had a pretty lean time. A lot of them died of poverty and heavy trekking. After the war was over, we went round and collected cattle from all the kraals. The loot cattle were kept at the loot kraal near Bulawayo. We did not take all the cattle from the natives, we took a certain proportion. There was a loot committee elected by the members of the forces in charge of it. I suppose we could have gone on doing it; but we got tired of it. After we had collected and sold and distributed some thousands of head of cattle, we got sick of it. The loot worked out at about £83 a man.

Comments on Teddy Campbell

The indaba was not at the gate of the Fort Victoria. It was a little distance away from the gate, perhaps 150 to 200 yards. Jameson sent for all the Indunas. Jack Redmond was not interpreting, it was Napier. I told you that the natives were in the open country behind the hills, down on the flat. But I think they were more than three miles from Fort Victoria. My own opinion is that the natives were retiring. How did the native know Jack Brabant by sight to call him by his native name when Jack Brabant had never been in Matabeleland! I never saw a native throwing an assegai. As we were coming home, Jack Brabant had a bottle of whisky and he had no corkscrew so he knocked the neck off and handed it to me. So I do not know where the flask that Teddy Campbell talks about came in.

We were riding along anyhow, and the natives were there in mass formation, and we hopped off our horses and let rip at them at about 300 yards. The Matabele then tried to advance. We mounted our horses and retired for another 300 yards and hopped off and fired again. There were only about three or four shots by the Matabele, all of which went high. They only had assegai’s.

My own idea is that we were driving the Matabele west over the border; but I did not take much notice of what direction it really was. It is true that everyone went for himself. I remember my half section yelled out: “Sergeant! Sergeant! This man won't keep section.” But I rode off and took no notice. I was chasing a native through the paddy fields (there were rice fields all over Mashonaland) and Bob O’Maker from the other side had hopped off his horse and shot him. We were all on our own. We were all very keen on shooting the Matabele. We had carte blanche to do it. The natives could never have turned on us because they were on foot and we were on horseback. That is how the Boers beat Mzilikazi. I do not believe for a moment there were 3,000 natives there, I should say 1,800 at the most. Loben would not need to send 3,000 to punish a few Mashonas. I reckon we did not chase the Matabele very far, if at all. We just fired two or three volleys at them and then they broke and cleared. We left them. We did chase individual natives, but not the whole mob when they cleared. A Martini-Henry bullet makes a hole as big as a jam tin.

The Grobler Mission

[Piet] Grobler came up to Bulawayo while I was here with my father, when we came up for the concession. Grobler introduced himself to us. But we were not in the habit of inquiring into other people's business. He saw the King. Before he left, he told us, myself and others there, that he had got the King to renew the original agreement that the Boers had made with the Matabele,[90] but that he had added other words to it. What he said was: “Maar ons het ander words bygesit.” By this I understood him to mean that they had added something to the original agreement without the knowledge of the King.[91] Grobler then asked us (that is Dawson and me) to give him an imprint of the King’s seal. He said he was collecting those sort of things. We refused to do so without the King's permission. Dawson had the seal and I kept the key. Grobler had Antoni Greef with him. Greef, I should say, was a mixed-race from the Dutch East Indies. He passed as a white man. I am sure Grobler was shot by his own people.[92] He was shot by Greef. I got that from the Lottering’s, who were there at the time. They told me that Grobler cried out: “Ek is geskiet, maar by een van onse ege mense!”

Lobengula’s wood-cut seal carved by Thomas Baines

Swinburne Jnr’s visit to Bulawayo in 1887

When Percy Umberville Swinburne, son of Sir John Swinburne, came to Bulawayo in 1887 with a man named Arkell, and saw Loben, he asked him: “Why have you given the Tati to Sam Edwards when you had given it to my father?” Loben's answer was: “When a man has a knife and he loses it, the finder returns it to the loser. But when a man throws away a knife, the finder can keep it. Your father had the Tati concession and he threw it away. Sam Edwards picked it up and it is his!” Swinburne then asked the King to give him a concession from Ramaquaban to Mangwe. The King agreed. The next day, finding he had got what he asked for so easily, Swinburne asked if he might have a grant up to Minyama kopjes, further up this way. The King said: “Oow! You want to come amongst my people.” Loben then refused to give him anything at all and told him to go down and ask Sam Edwards nicely to give him ground between the Shashe and the Macloutse rivers. Swinburne declined it. Later Loben offered the same ground to Joe Wood and Chapman, who also declined it. Loben's idea was to have a buffer between his country and the south.

When Grobler returned to the South African Republic, the Induna Gambo disappeared from Bulawayo, fearing the King's wrath because he had put one of his daughters with child. Shortly afterwards Swinburne was leaving the country after having tried to get a concession and this girl asked him to take her down to go and join Gambo, which he agreed to do. Swinburne left with his wagon, and the girl and her two slave girls followed on and caught up the wagon. On Swinburne's instructions they did not travel with the wagon, but walked alongside in the bush some little distance off the road and came into the outspan at night. They put their things on the wagon however. An impi was sent after them and caught up the wagon. The girl was not there; but the Matabele noticed her things in the wagon. They said nothing and came back after the wagon had outspanned that evening and surrounded it and caught the girl. Everyone was brought back to the King. I was not here at the time, though I must have been in Matabeleland, but I heard afterwards that the King had a lot to say and turned Swinburne out of the country. Told him not to come back. Actually, Swinburne did not come back until the Matabele War. The girl was not killed. It is not true that he had an affair with the girl. It was not safe for a white man to have anything to do with the King's daughters. Loben afterwards sent word to Gambo to come back and it would be all right and Gambo came back and married the girl.

The journey up to Bulawayo in 1888

Thompson says his party started from Kimberley on 15 August 1888; took 22 days to Shoshong and 7 days from Shoshong to Tati. He arrived in Bulawayo between 21 – 23 September. He travelled with mules.

Water was scarce on the old Tati road. Once upon a time, after leaving Mafeking we used to turn off eastwards and make a detour through the Transvaal in order to be sure of water, until they caught one or two of our fellows and made them pay import duty. So that stopped that. Our road from Mafeking used to be to Kanya and from there we used to go to Ramoutsa. Then, if there was water at Tsama Kop, we would then go via Molepolole. The natives would tell us if there was water or not, or we would know ourselves that there was water if rain had fallen. We always had to go by the rains.

From Molepolole we used to trek across to what they called Wegdraai on the Limpopo River. We would strike the Crocodile or Limpopo usually below the junction of the Notwani and then from there, we would trek to Shoshong, a matter of nearly 40 or 50 miles without water. The way we did it was, we would rest the cattle at the river for about a week. Then we would trek forward a long trek, send the cattle back to drink and when they came back we would trek forward and then send the cattle forward to drink and then bring them back again.

At other stages on the road there was water if you knew where to find it. There was one point on the journey where Patterson lost his valet, a steward from on board the ship that he brought up with him. Patterson could not find him and trekked on. The Bushmen followed his valet’s spoor and it led back to the camp and away again. They found him dead of thirst.

Coming up with a waggonette and mules, I had a friend with me of the name of Harry Lovemore.[93] Travelling along among the granite kopjes there we saw two native youths asleep in the road. I told the two Dutchmen driving to stop and Lovemore and I took our guns, walked up to the sleeping natives. We each kicked one in the ribs, fired off our guns simultaneously, and grabbed them: and I shouted: “Muna, metsi ukai” (Where is the water?) They both said: “Kwa, Kwa!” (There, there!) We marched them on and they led us to a rocky pool a quarter of a mile off the road, a nice deep pool. While we were there, two adult natives turned up and asked me who showed us the water and when I told them, both cut heavy switches and gave the two youths a thrashing! Before we left we blazed the trail to show everyone.

After that many of the chaps called the water ‘Fry’s Pits.’ Khama’s rule was that all travellers had first right to water. There was a place called ‘Sofala’ the same name as the place on the East Coast, and the first place coming from the south where you will find wild figs growing. I know of only one other wild fig in South Africa and that is in Uitenhage. On reaching Sofala the second time I came up (the first time we came round by Tsama Kop) we found ourselves at three water holes in what seemed by the water worn stones around to be the bed of an old river. We took possession of one hole, cleaned out all the cattle, dung and mess from the cattle which were allowed in freely and put bushes around it to keep the cattle off and put a pole across two fork sticks at the opening which would allow two cattle at a time to come in and drink at the edge; but would keep them from walking into the water. The natives came along and demanded what right we had to do this: but when I threatened to report them to Khama, no more was said.

White Inhabitants of Matabeleland in 1888

Foster Windram had the list of the white population in Matabeleland in 1886 published by Alex C. Bailie and asked Ivon Fry how many of those named he knew personally. Fry states that when he came to Bulawayo there were the following white people in the country.

Boers (Afrikaners) Down at the Tati there will also lots of Dutchmen, but none in Matabeleland. I do not think they fancied us. We did not encourage them, but Dutch hunters used to come up in their wagons with their wives and all their kids.

George Dorehill[94] hunted in Matabeland with a native tracker called ‘Hell hound.’

Alex Brown He married a tall Dutch [Afrikaner] girl. When he was courting her, he was sitting in the front room with her and there was a dog under the table. The upper half of the stable door was open. A leopard jumped in and Alex said: “Shut the door!” and he chased the leopard round the room with an assegai. It jumped on the old people who were in bed and the old man pulled the blanket over his head. Brown kept stabbing at the leopard that was growling and striking at him until he turned the point of the assegai on the wall, and could do nothing, and shouted: “Open the door!” and so she did and the leopard flew out again.[95]

Johan Colenbrander came in with Edward Renny-Tailyour and became the British South Africa Company representative at Bulawayo. Trusted by Lobengula, he accompanied the Indunas Mshete and Babayane to England to see Queen Victoria and protest the Rudd Concession. However he supported the BSAC in their attempts to build up to the 1893 Invasion of Matabeleland.

James Dawson[96] had a store with James Fairbairn just below the King’s kraal. He had been here for some time. Native name Jim-solo. Subsequently married Allan Wilson’s fiancée named May Manson Thomson 1896 before returning to Bulawayo where he and his brother established eleven branches of Dawson’s Stores in locations such as Balla Balla, Essexvale, Fairview, Filabusi, Geelong and Khami river.[97] The marriage did not last and May returned to Scotland with their son Ronald Maurice and James Dawson left for Lealui in Barotseland where he lived for the rest of his life.

Sam Edwards (Samu) who had the Tati Concession, was made an Induna by the King. It was an honorary title with no duties, or perquisites attached. But he was supposed to interview anyone wanting to come into the country. Sam Edwards was stationed at the Tati Concession and people used to stay with him until they got permission to come into the country. No one could come in without asking for the road, and when you left, you asked for the road too. But Sam Edwards was always in and out of Bulawayo. The prospecting parties that came up in 1868 were all gone by the time Fry arrived in 1886 and he says they were only pottering around with the gold mining.

Edwards died in Port Elizabeth in 1894. He got £34,000 for his share of the Concession. I got £14,000 out of it.[98] Edwards was one of the first white men to come up here after Mzilikazi came up. His father, Reverend Edwards was a missionary at the place Livingstone first came to in the Transvaal and Sam interpreted for Livingstone. When the Boers came up they destroyed all the Reverend Edwards’ books. I heard Sam speak of his early visit to Mzilikazi.

James Fairbairn had been here a good many years, longer than Dawson. Both he and Dawson were quite decent fellows. Neither of them had native wives, but they had intercourse with native women.[99]

Tom Fry (no relation of Ivon Fry) was the brother of Ellerton Fry, who took the Pioneer Column photographs) and lived mostly in Mangwato, was called ‘Old Boozy Tom’ and died up in the north of present-day Botswana.

Harry Grant had a native woman at one time; but I think she was dead and he had a mixed-blood son with him. He lived in his wagon and moved about the country doing odd jobs for the other white people. Grant was sent out from Inyati once to go and buy cattle for Robert McMenemy in the back veld. The lions followed him all along and pestered him so much that he came back to Inyati. He was in his wagon, some distance from the other people, and he had a calf tied under the wagon and a lion came along and killed the calf in broad daylight. Grant was with his native wife and a boy rushed off to the others down at Martin’s Store, where I was too at the time. The Dutch speaking boy then said: “Baas, Baas, there’s a lion under the wagon!” So the question was put to him: “Where is Grant’s woman?” and the boy said: “Bo in die boom, Baas” (up in the tree) “Where's the beast?” “In the wagon, Baas.” So we rushed out and the lion came out and we shot it. We heard from the natives afterwards that each time the lion growled under the wagon, Grant would say: “Oh God!” in Dutch and take another swig at a bottle of dop. Grant had a red birthmark on his face.

George Hall was an American who came out with Cobb and Co, the coach manufacturers. He ran the coaches from Port Elizabeth to Kimberley in 1871. They had those spring coaches. Then he was at Tati for some years, then when the Pioneer Column came he was at Tuli he took part in forwarding goods. When Fry first came up in 1886, Hall was at Tati.

C. Hesketh moved from Matabeleland to the Zeerust district

John Lee and his two sons C.T. Lee and R.P. Lee lived at Mangwe on the road to Tati from Bulawayo

Robert McMenemy was Frank Mandy’s trading partner at Inyati in 1875, but Mandy had gone back South. McMenemy was trading all around the country. Later, he retired to Tati. They used to trade limbo (cloth) beads, blankets, guns and gunpowder and ammunition generally to the natives for cattle and ivory when they could get it. The Mangwato people were the people for skins.[100]

George Martin had a trading store on the Inkwekwesi river at Inyati. He had a white wife with him and children.[101]

The Missionaries In addition to the English Missionaries of Helm, Carnegie and Rees, there were the Jesuits. Father Prestage[102] and two others, I think, whose names I have forgotten.[103] They were out towards Inyati[104] in my time and then at Empandeni Mission.

Johnny Mubi[105] (John Halyet) was a runaway sailor who lived next door to Hope Fountain in a place called Happy Valley. He had been here some years. He used to do odd jobs for people here, including the King. He built the King's house for him. I do not remember the King’s wagon shed. It may have been there.

I once asked Johnny Mubi how he got his native wife. He used to call her ‘Hannie’ and he told me some slaves were brought in front of the King one day while he was present. They had been taken away from somebody who had been smelt out. Among them John saw a young woman and he said in English: “King, give me that woman for my umfazi”[106] and the King replied in isiNdebele: “Do you want her for your umfazi?” and Johnny Mubi said: “Yes!” so the King said he could take her. You could get as many wives as you liked in the country. Someone wrote to the paper the other day that Johnny Mubi had a wrestling match with the King. That is all nonsense, it never happened. Johnny Mubi never learnt to talk isiNdebele, he used to talk English to the King.

Paddy O’Reilly was a trader who had been here a long time. He and Dawson went up in 1893 and pegged the Victoria Falls for Julius Weil; but when they got back to Bulawayo, the German would not acknowledge the pegging and refused to register it. They wanted to peg it for farms.

Peterson a German had a trading store down at Old Bulawayo. He had been up here some years.