The Hanging Tree

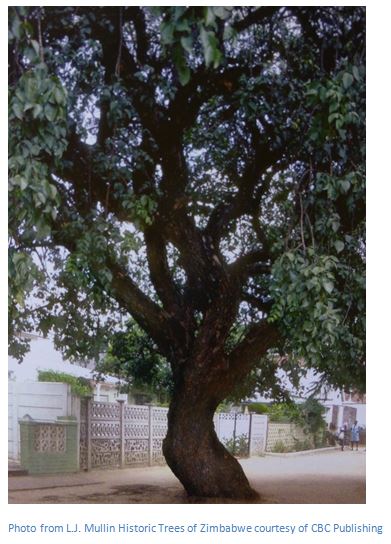

Indigenous trees are rare along Bulawayo’s roads; most were planted with exotic trees in the twentieth century. This false Marula was spared because of its symbolism.

It represents a moment in time when the citizens of Bulawayo were unhappy and scared at the fate of many of their friends and colleagues who had been brutally killed at the onset of the Matabele Rebellion, or First Umvukela.

The hangings of looters and supposed spies, after hasty trials, “rough and ready” as Selous writes cannot be condoned, except to say that those citizens were living in dangerous times with the killings of their friends and colleagues fresh in their minds.

East side of JMN Nkomo Street (previously Main Street) between Connaught and Masotsha Ndlovu Avenues

GPS reference: 20⁰08′33.00″S 28⁰35′09.00″E

Lyn Mullin writes that the hanging tree is an average-sized specimen of a false Marula, or Lannea schweinfurthii, with a wide –spreading crown, which was for many years a proclaimed national monument, but was de-listed and today few know of its existence, or of its history. It is one of the few indigenous trees left standing along a main street and there is a dark reason behind its existence.

During the Matabele Rebellion, of First Umvukela of 1896-7 a total of nine amaNdebele men were hung from the tree; three for looting when the inhabitants of Bulawayo moved from their homes into laager and six for allegedly spying. At the time the tree was outside the town’s fortifications and a number of authors have said this was done to intimidate and put fear into the amaNdebele on the outskirts of the town.

Stories appeared in British papers in 1896, such as the Daily Graphic and Truth, that wholesale hangings were taking place in Bulawayo. Selous quotes a letter which appeared in the Daily Graphic on the 13 June 1896 supposedly from a Bulawayo tradesman saying: “my stand has one big tree on it, and it is often used as a gallows. Yesterday there was a goodly crop of seven Matabele hanging there; today there are eight…”

Mr Labouchere, the editor of the Daily Graphic reproduced the letter in his paper as well as another in which the writer wrote of it being “quite a nice sight” to see men shot as spies. No efforts were made by the newspapers to verify whether the reports were true or not; they were just printed.

Selous denies that widespread hangings took place, maintaining these were the only executions of this kind. The three looters were caught red-handed near Soluso’s kraal, thirty kilometres west of Bulawayo, looting and burning a farmers’ property and were all armed and were the subjects of Nduna Maiyaisa whose people had been amongst the first to rebel against European rule. Although I have not researched through the records; Selous says the other six were all hanged singly and at different times and admits that although they were “tried in a somewhat rough-and-ready fashion” they were undoubtedly proven to be spies and rebels.

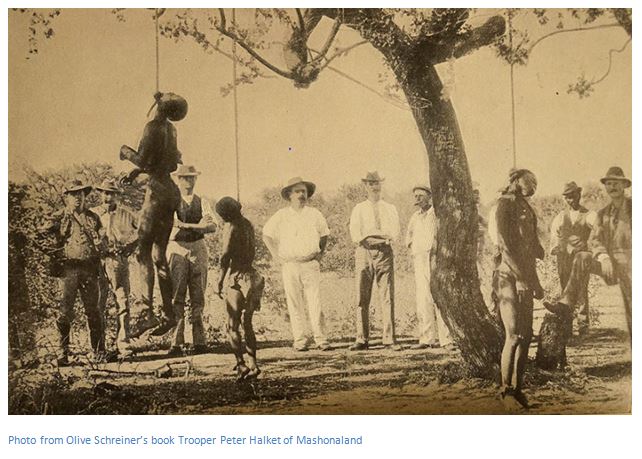

Olive Schreiner published the photograph above in her book Trooper Peter Halket of Mashonaland. Formerly a great friend of Cecil Rhodes, she became a fierce critic and the book was her response to what she saw was a great injustice. The public outcry made the British Imperial Government take much great notice of the British South Africa Company’s actions in Mashonaland and Matabeleland and for the first time, a Resident Commissioner were appointed to supervise the affairs of the British South Africa Company. The Resident Commissioner reported to the High Commissioner of Southern Africa, who in turn reported to the Colonial Office in London. The Resident Commissioner's function was to protect African interests and to prevent the company from over-reaching its powers granted by the Royal Charter and to ensure that its actions were even-handed in respect of African and European interests. The first appointee was Sir Marshall James Clarke who occupied the post from December 1898 to April 1905.

At the time Bulawayo was surrounded by amaNdebele forces and the citizens were feeling seriously threatened; a battle had taken place on the Umgusa River to the northwest with Gifford’s patrol having been strongly attacked, followed by a heavy skirmish at Fonseca’s Farm when about 1,500 amaNdebele warriors were present and the Troops were chased into a temporary laager. A determined charge was made, but the attackers were beaten back by steady fire rifle fire and the Maxim gun, although they managed to get within 200 metres. After a quiet night the amaNdebele attacked again the next day from all sides, but retired again about midday. Troopers S.K. Mackenzie and E.E. Reynolds were killed, Captain J.W.M. Lumsden mortally wounded, and Colonel M.R. Gifford lost his arm, Troopers J. Walker, Fielding and W.J. Eatwell and Lieut. J.H. Hulbert were wounded

News was received soon after that Captain Tyrie-Laing had managed to gather all the surviving inhabitants of Belingwe and Filabusi into the Belingwe laager after receiving a message from H.P. Fynn, the Insiza Native Commissioner that a widespread rebellion had broken out in the district and many civilians killed.

In the background to all these events, the inhabitants of Bulawayo were kept very aware of the ever present danger to themselves. On 6 April a herd of cattle were driven off only two kilometres from the hospital and several herdsmen and locals sleeping outside the cattle kraal were killed. Selous was tasked with setting an ambush at the site of another cattle kraal near Dr Sauer’s house, also just outside Bulawayo. However, nobody came in the night and in the morning it was established these cattle were dying of rinderpest.

Acknowledgements

L.J. Mullin. Historic Trees of Zimbabwe. CBC Publishing

R. Burrett and T. Mukwende. Bulawayo memories. Khami Press, 2015

O. Schreiner. Trooper Peter Halket of Mashonaland. Roberts Brothers, Boston, 1897

F.C. Selous. Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1968