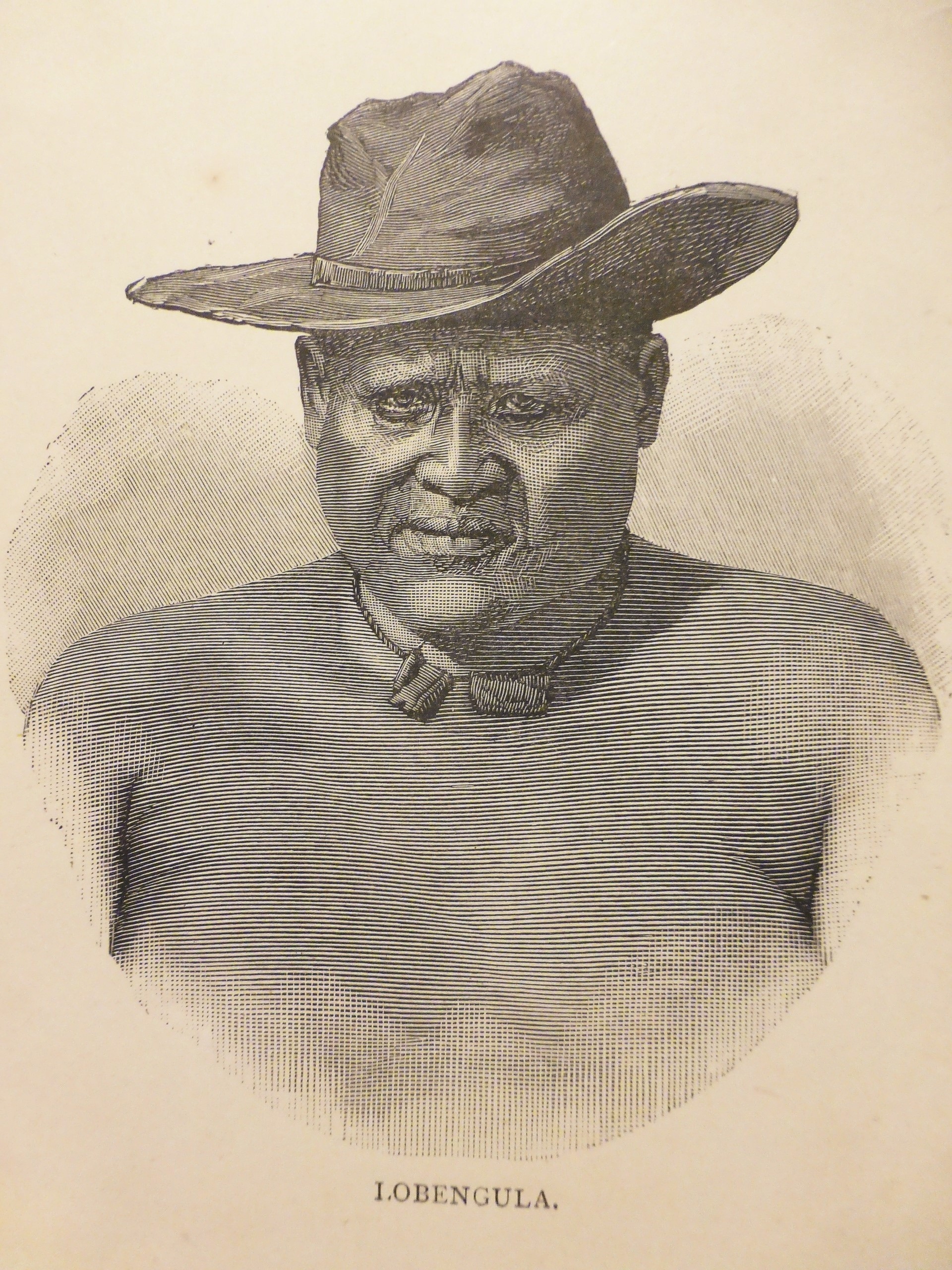

The Great Dance or Inxwala Festival

Background to the Great Dance

The Inxwala, or Great Ceremony, usually called the Great Dance, in the nineteenth century was of course not really a dance. It was held annually just after the ripening of the first of the new crops, usually in January. It was actually a religious ceremony, to please the ancestral spirits and indirectly a rekindling of national loyalties and essentially it is about cleansing and renewal, and – above all – celebrating Kingship and to thank the King for bringing the rain. As long as the correct rituals were followed by the King then there would be good germination and growth of the season’s harvest. The King was essential for the ceremony and this caused the problem in 1840 when Mzilikazi was absent from Gibexhegu the first capital in Matabeleland[i]

Those rituals included the killing of the oxen, particularly black bulls whose strength would be transferred to the King and hence to the whole nation. Ripened marrows (amakhomane) were given by the King to his warriors as part of the ceremony to symbolise revitalisation and rebirth.

It was followed by a ritual tasting of the season’s first fruits, carried out at all the kraals by the traditional spiritual leaders after which the people were permitted to eat the new crops. The ritual offering of the first fruits to a God or through his human representative, or to the King, has been a widespread religious ceremony for millennia and is also celebrated in European countries as Thanksgiving Day or Harvest Festival. In Eswatini’s (formerly Swaziland) it is the most important cultural event.

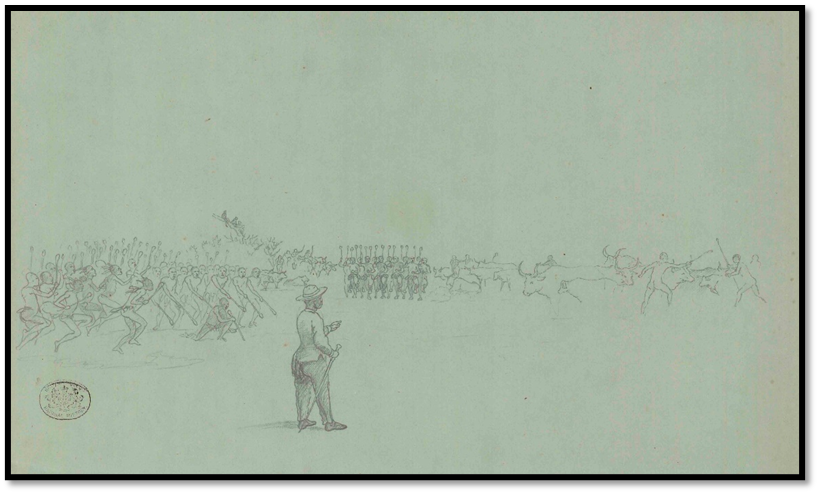

NHM (London) No 61: sketch by Thomas Baines of Lobengula reviewing his army in November 1870

The timing of the event was really important and its exact date depended on the time of the ripening of the crops planted in October and November; in Mzilikazi and Lobengula’s time the rains generally arrived in October and by January the crops were growing and would soon be ready for harvesting. Amongst the amaNdebele a ceremony, a minor Inxwala was held a lunar month before the main event, when milk was delivered to the King. The minor Inxwala was a private affair involving the King alone and on the night of the new moon he went into spiritual seclusion as it was believed malign forces were present from which he needed protection. When the crescent moon appeared an offering would be made to the rising sun to symbolize renewal and hope for the future. In public at the royal kraal a black bull would be killed and eaten and the regiments from the various parts would begin assembling for the main Inxwala that followed a month after the minor Inxwala.

So the Inxwala was usually celebrated in January or February, but in 1870 it took place on 3 March.[ii] Messengers were sent out to summon the people to the royal capital for the event and most of the regiments attended and supplied cattle to be sacrificed. Temporary huts were built outside Gubulawayo and the indunas were responsible for the good behaviour of their warriors. The Inxwala lasted five days when no business was carried on and no wagons were allowed to leave.

Many early travellers incorrectly linked the direction of the throwing of the assegai by the King to indicate the direction that the regiments would raid in the following winter months and associated the main Inxwala with military significance and violence. The regiments danced and sang in full war dress – most white visitors were hugely impressed by their skill. The cattle were killed and then skinned and cut up, being left outside over night for the ancestral spirits before being eaten.

Following the Inxwala special messengers were sent to all the kraals to announce that the ceremony of the First Fruits was complete. The men and boys older than twelve years were ritually cleansed and this was followed by a ritual tasting of samples of the harvest. Women and children were allowed to watch but did not take part and there was no dancing. The main Inxwala was always held at the time of the new moon to symbolise regeneration and rebirth and points to the ceremony’s primality as a religious and cultural festival.[iii]

The descriptions below were written by early travellers and by missionaries. There are others from the likes of Thomas Baines, Rev Thomas Morgan Thomas and Rev W.A. Elliott, but they have been omitted so the article does not become too repetitive.

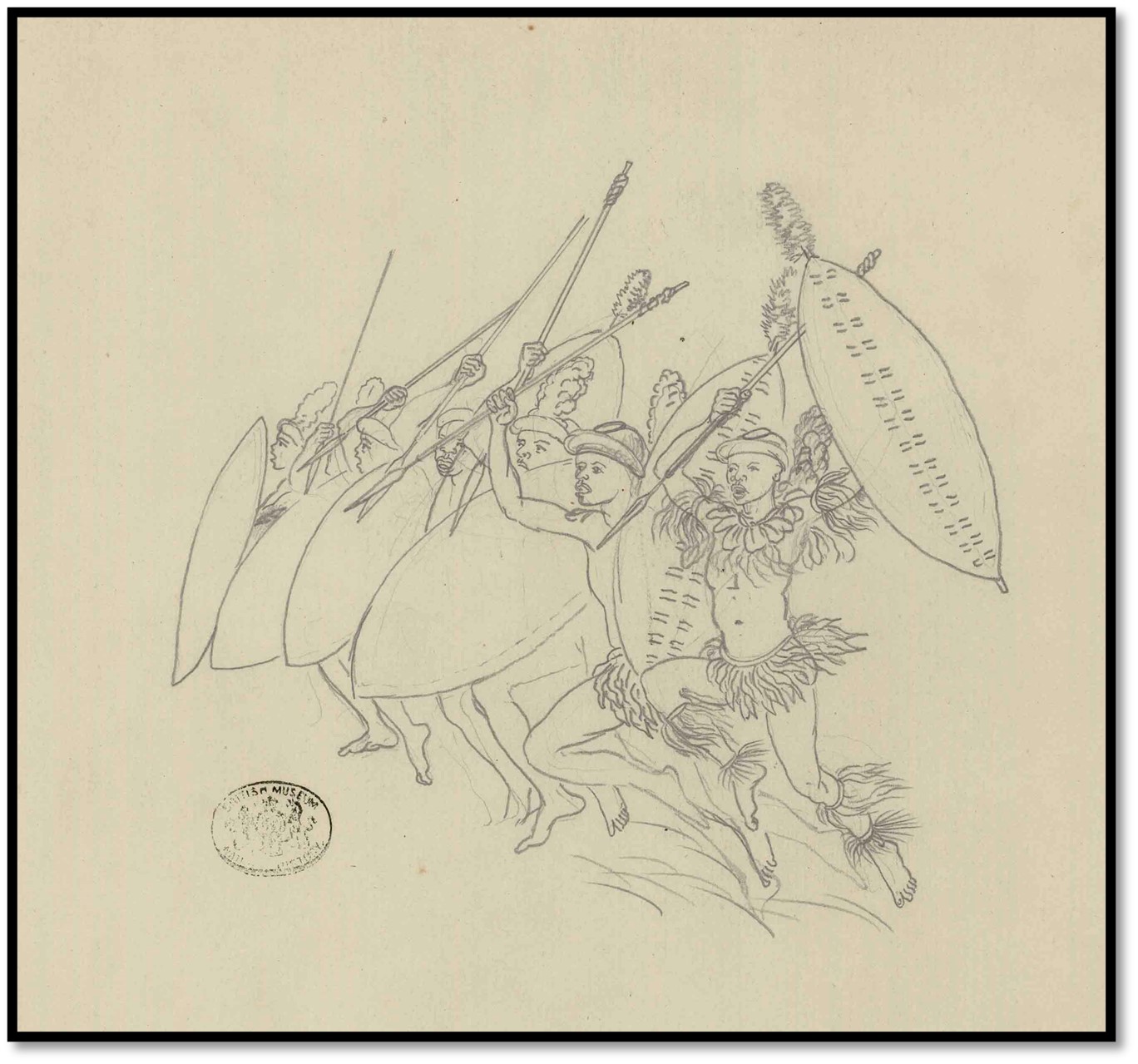

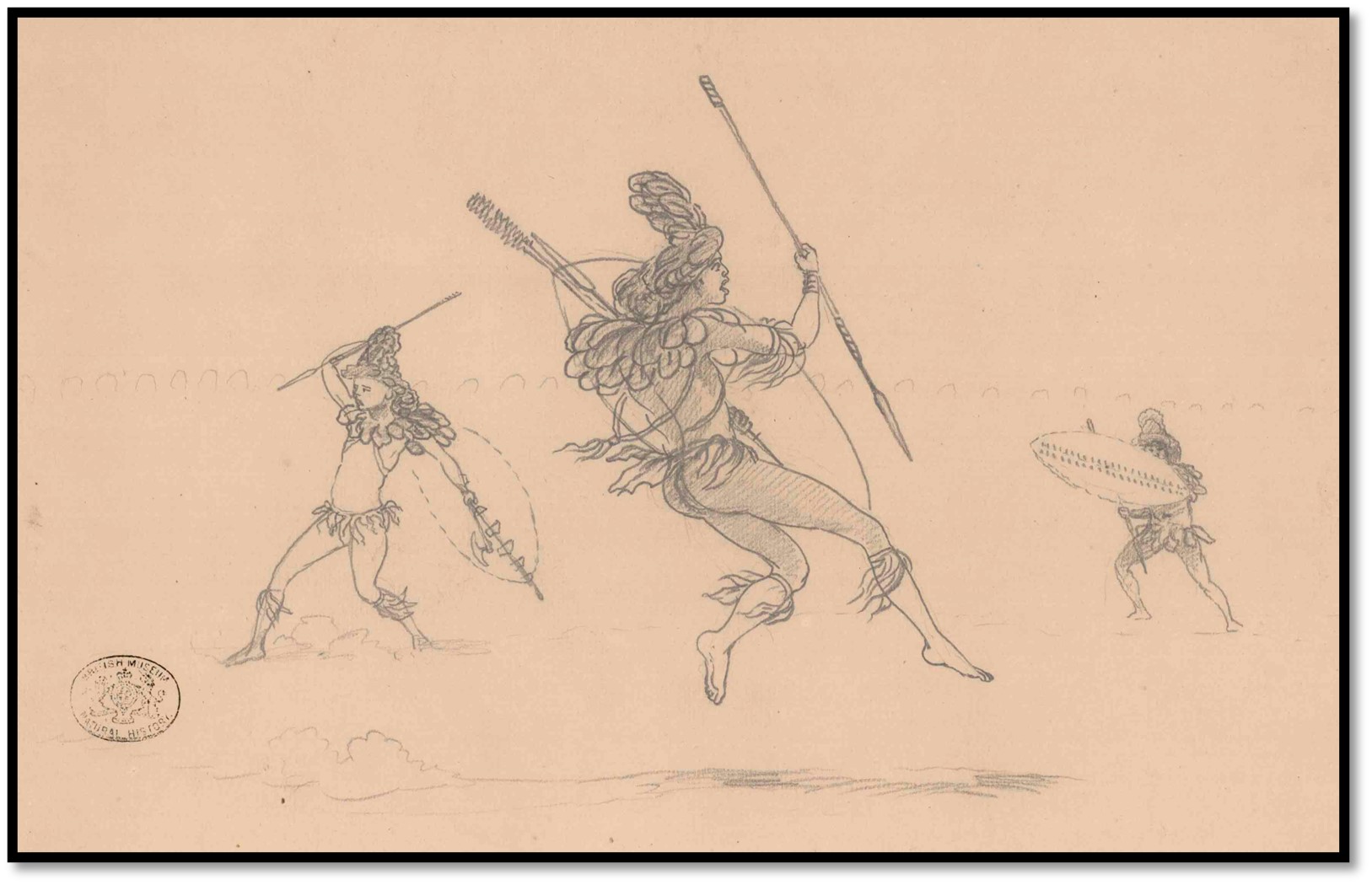

NHM (London) No 63: Thomas Baines sketch of Lobengula’s warriors

The Inxwala in 1878

Frederick Hugh Barber[iv] arrived in Gubulawayo in January 1878 after a hunting trip with a small party above the Nata river during which his brother, Harry was badly hurt by an elephant, but survived. He writes: At Bulowayo (sic) the traders have built a number of houses and stores and there are usually about fifteen or twenty whites living there always. The elephant and other hunters collect here in the beginning and at the end of the season. Permission to hunt must be procured from the King before you can enter the hunting veld. The hunting season commences as soon as the worst of the fever season is over, at the end of April, and the general ruck of hunters get back about November, at which time the weather becomes hot and the rainy season sets in. The hunters disperse to their different homes in the Transvaal, Kimberley, etc. Many stay in Bulowayo where they sell their produce of ivory, (ostrich) feathers, (rhino) skins, etc. The majority of the hunters are Boers, and traders, English.

Soon after our arrival, the great dance of the first fruits was celebrated. A small white tent was pitched at the gate of the sekotla,[v] in front of which, in his armchair, he (Lobengula) sat, a white gamp[vi] held over his head, surrounded by counsellors, indunas, white men and attendants, reviewing and inspecting his army. This was a magnificent sight, a great dusky phalanx of sable warriors seven or eight thousand strong, each regiment under its own induna and distinguished by different coloured shields covered with bullock hide. Marking time with measured tread, they chanted solemn dirges and sang war songs, Striking their shields with assegais, while distinguished warriors would bound from the ranks, spring into the air, stabbing and thrusting as if in desperate combat, each thrust signifying a man he had killed. Sometimes in his excitement, a man would make too many stabs, and be greeted with howls and shouts of derision from his companions for lying when he would retire crestfallen to the ranks.

The King would also go through a ceremony of throwing an assegai, applauded by terrific shouts from thousands of men. Great numbers of cattle were killed to feed the warriors. Sometimes a wild bullock would escape after being wounded by a badly directed thrust from an assegai and would career over the veld, pursued by a dozen shouting warriors, who would bring him back, exhausted, to be slain for dinner. The first day at night, the flesh was spread out and hung on the kraals and fences to propitiate evil spirits. Next day the hungry warriors would be given permission through the witch doctors to feed ,the spirits being appeased. Then the scene of roasting, gorging, half-cooked meat would commence, that was more like an orgy of ghouls than human beings, tearing and fighting for the meat and rubbing their heads and ebony bodies until they shone with fat.

The noble savage being surfeited, he would throw himself down in a sunny spot, belch, grunt, pick his teeth with a chunk of wood and go to sleep, until a cry of more meat arose, when he would rise and commence skoffing again, as if he had starved for a week. It was a beautiful and edifying sight and made us feel proud and good that we were gods, chosen creatures, and had souls and so much better than the beautiful wild game that frequented the country.

Another account of the Inxwala in 1878

Andrew A. Anderson writes:[vii] When I arrived at Umkano kraal[viii] or, as some term it, Umganin, on the 30th December, it was Sunday; when I had drawn up my waggon in a nice snug nook to be away from the native kraals, and outspanned, it was 4pm. Dinner was soon prepared and despatched, and then I sent my two warrior guards to the King to announce my arrival, and that I would call on his majesty to-morrow.

I went to call on Lo-Bengulu; he was sitting on his waggon-box naked, all but his cat-tail kilt. After shaking hands and passing the compliments of the day, I told him, as he expected one of his regiments over to escort him to the military kraal, that I would defer my talk with him until after the grand dance. He asked me to follow him when he started; that meant, I was to fall in with the other waggons of the white people composing the cavalcade.

We started about 11am, Mr Sykes[ix] taking the lead behind the King’s waggons, which were surrounded by about twenty Zulu women and girls. One waggon held his sister Nina and the native beer; next followed Mr Coillard[x] and his waggons, then my waggon, Phillips,[xi] Viljuen,[xii] and other white men on horseback, and about a hundred of the King’s bodyguard, about as unique a turn-out as one could desire to see—an African King on his travels—it would have graced Regent street.

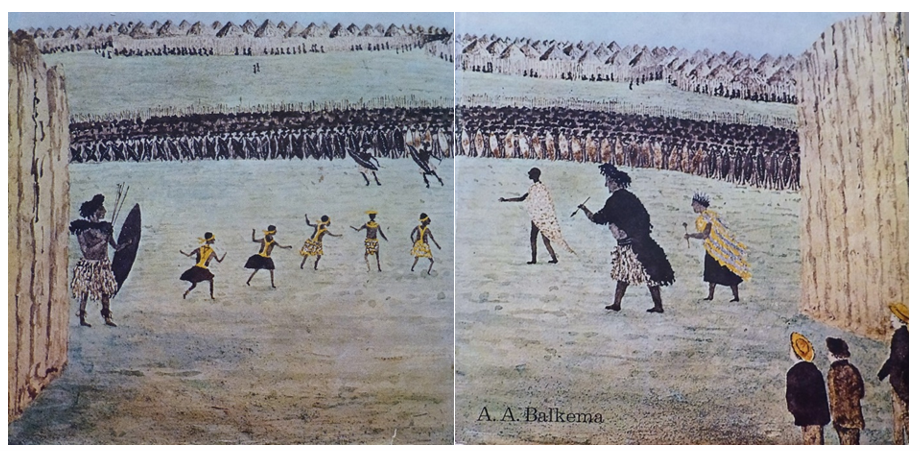

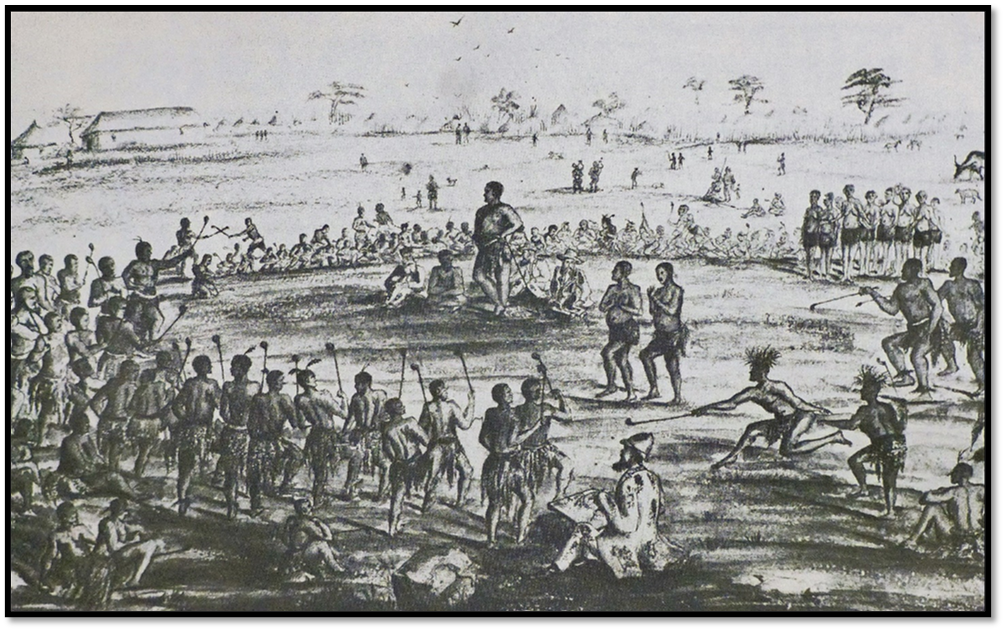

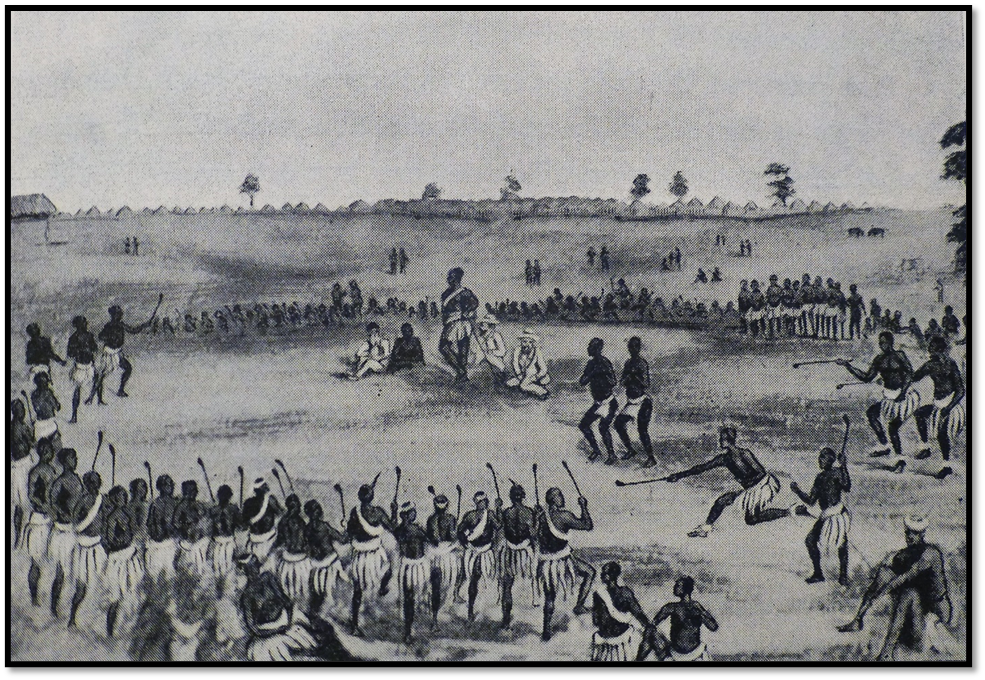

From Journey to Bulawayo: painting by A.A. Anderson – Lobengula reviewing his warriors, his daughters dancing and his sister Ninja on the left

After a seven-mile trek, we outspanned for the day at a small kraal, on the road to the military camp—as a messenger had been sent to say five regiments would be sent out the next morning, inviting the King home, being the usual custom on the King returning after a long absence; therefore we selected a suitable place to remain the night and made ourselves comfortable for the remainder of the day.

Tuesday, January 1st, 1878.—A lovely bright morning. Thermometer at 9 a.m., 87 degrees. After breakfast the Matabele regiments came over, some four hundred, dressed in their war dress, black ostrich feathers for head-dress, a tippet and epaulets of the same, tigers’-tails in profusion round the loins and hanging down to the ground behind, with anklets of the shell of a fruit the size of an egg, with stones inside to make them jingle as they move their feet; armed with shield and several assegai’s. So they came on, singing their war songs, jumping up, striking their shields. With their black skins, white teeth, and the white part of their eyes, they were fit representations of imps issuing from a certain place known to the wicked. On arriving at the King’s waggon, where the King was sitting on his waggon-box, they went through a kind of dance, singing the King’s praise, Lo-Bengulu quietly looking on. The King’s wives, between thirty and forty, dressed only in black kilts down below the knee, open in front; the kilt is made of black sheep or goatskin; some, I think, are made of otter-skin; others had mantles of the same; several had their heads shaved; many cut quite close. After the dance, we all inspanned, and followed the King’s waggons in the same order as yesterday; until we arrived at Gubuluwayo, the military kraal. I took my waggon and outspanned alongside of Mr Wood’s[xiii] waggons, on the opposite rise to the kraal, to be free from the people, and have some peace; and remained the day. All round the kraal is open, every available piece of ground is under the hoe.

Wednesday, I went in the morning, with Mr and Mrs Sykes, Mr and Mrs Coillard and her sister,[xiv] who seems to be about twenty, to the King’s kraal, to see the soldiers reviewed by the King, in the open space between the town huts and the King’s enclosure. It was a novel sight, and one seen in no other part of the world. The regiments formed an immense circle, eight and ten deep; there appeared to be about four thousand, all dressed in their war dress similar to those of yesterday. Each regiment contains about six hundred and is distinguished by different coloured shields. When they sing their war songs in their deep bass voices, keeping time with stamping on the ground with their right and then left foot, striking their shields with their assegai’s, the effect is grand—the earth appears to tremble. Occasionally, one or two come out into the centre of the circle and go through the performance of fighting the enemy, advancing, retreating, then in close combat, striking out with their assegai in imitation of stabbing his foe and making as many stabs as he has killed victims; others come out when these retire and this performance goes on during the war songs. It is considered a great feat if a warrior can jump high in the air and strike his shield several times with both ends of his short stabbing assegai, before touching the ground and knocking his knees and feet together.

Then come the King’s wives, old and young, and all the young royal girls, wearing a black goatskin kilt down to the knee, dressed out with yellow handkerchiefs, the royal colour, profusion of many-coloured beads, many-coloured ribbons, long sashes of broad yellow ribbon, all entering the arena at the same time. Advancing to the centre with slow measured steps, they raise first the left, then the right leg, and put it down, keeping excellent time, chanting native songs, the warriors remaining perfectly still and silent, they then turn and retire in the same way; all this time the King is not seen, he is in the cattle kraal with his medicine-man, examining the intestines of two bullocks that have been killed for that purpose. After a time, a clear road is made and large baskets filled with the intestines are brought out from the kraal: it is death for a native to touch it or be near when it is passed away to the King’s enclosure. Then comes out the chief medicine-man, enveloped in long ox-tails that completely conceal his tall figure reaching to the ground with a little jockey cap on having fur in front and a long crane’s feather, when he marches up and down in the centre of the arena and in front of where the King is known to be, singing his praise.

From Bulawayo, Historic Battleground of Rhodesia: watercolour by A.A. Anderson – Old Bulawayo, the Great Dance 1877

After a time, the King makes his appearance, advancing from the kraal with a towering headdress of black ostrich feathers, an immense cape of the same, a kilt of cats’-tails with an assegai poised in his right hand, advancing slowly in a stooping position; his fat sister Nina, dressed out with a long kilt half-way down the leg, any number of yellow handkerchiefs over her shoulders and gold chains hanging down in front and behind, with the feathers from the tail of the blue jay stuck into her woolly hair and a knobkerry in her hand, also advances beside the King, until they both reach the centre of the arena. The warriors singing their war songs, stamping their feet to keep time, rattling their shields, the scene becomes quite exciting. Poor Nina becomes exhausted, has to kneel on the ground several times, supporting her body with her hands also on the ground and looks anything but an elegant figure. The five royal daughters whose ages average from sixteen to six, advance again and chant a native tune; then the King calls for silence; order is given that each regiment is to march out on to the open plain and have a sham fight, which lasts an hour, each army advancing, retreating, and fighting.

They then return to the enclosure and form themselves in line, when forty black bullocks are brought in for the young braves to slaughter, by stabbing them behind the shoulder so that the skin should not be injured to make shields; some become maddened by the smell of blood, break loose and escape into the open country, the young braves following, and a regular race and uproar follows, creating quite a sensation; and when the night has come, great feasting takes place, and the sports of the day are at an end, and we return to our waggon, wondering what the people in England would think of such a sight of savage grandeur, as was never seen out of Africa. The young Intombies (girls) are all excitement to see their sweethearts so brave. These Zulu maids are most of them good-looking with teeth as white as snow, well-made in every limb and graceful in their movements, very scantily dressed, a slight fringe in front being their only covering, but it is the fashion of the country. For several days these dances go on; those who have paid their respects to the King retire to their distant kraals, and fresh regiments arrive to go through the same performance. The English who may be at the station are allowed to be present, but they must keep out of the way, not to be mixed up with the troops, but they can take up any position they like to have a good view of the proceedings.

Thursday, a lovely day. Went up again to see the review with Mr and Mrs Sykes and the Coillard’s; found the King sitting on a chair in a bell-tent alone, facing the troops, who were in a circle as yesterday; he was naked with the exception of the tailed kilt. A few braves from his favourite regiment composed his bodyguard; the chief Indunas were with their respective regiments of which they held command; the medicine doctor, clothed in a tiger-skin kaross and a large fur cap with ears of the same marched up and down before the tent, proclaiming to the warriors the greatness of the King. The English ladies were invited into the tent and stood beside and behind this dreaded monarch of this dreaded nation, for all other native tribes fear him. The military performance was similar to that of yesterday; rain came on and we returned to our waggons.

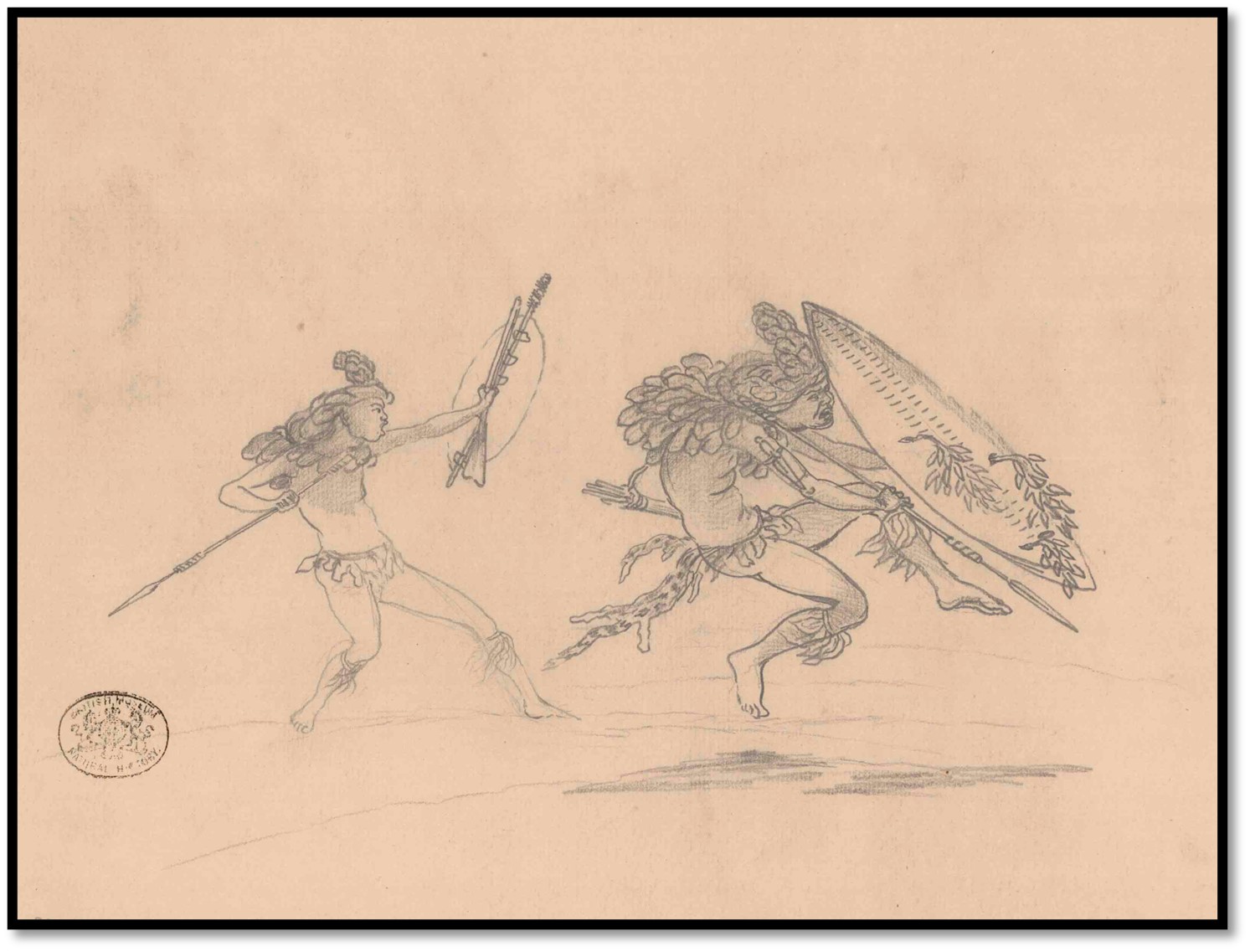

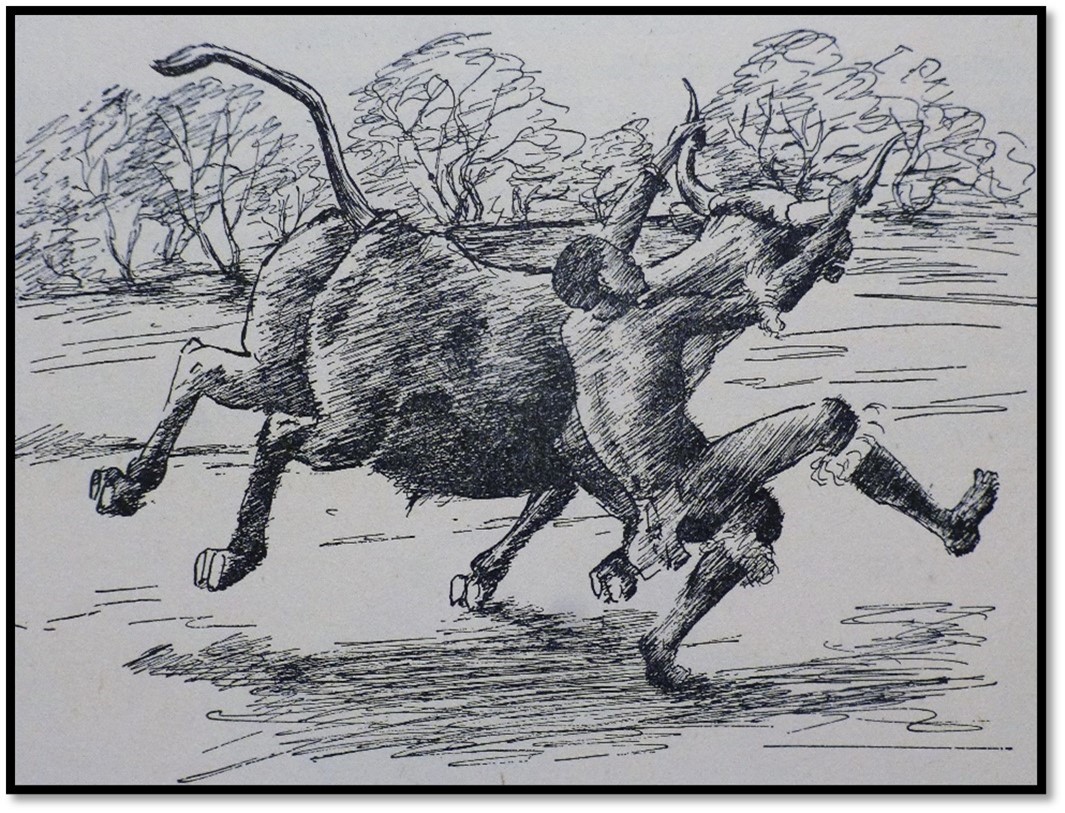

NHM (London) No 65: Thomas Baines sketch of warriors charging in November 1870

The Inxwala in 1880

Father Croonenberghs, a Belgian Jesuit was a member of the Zambesi Mission and the first Catholics into the region and wrote this letter[xv] from Gubulawayo on 11 January 1880 as follows: Yesterday, 10 January, was the festival of the Summer New Moon, or the Matabele New Year; it is also called the Festival of the First Fruits. or the festival of the Little Dance to distinguish it from the festival of the Great Dance, which is to take place a fortnight later, at full Moon…

At the entrance to this kraal King Lobengula presides over the ceremony of the Little Dance accompanied by the chief witch doctor. Extending from this entry right out to the external huts, more than a thousand warriors are ranged in a semicircle. On their heads they wear great black ostrich plumes, their shoulders are covered with skins of lion, hyena, jackal or leopard and they hold a long mimosa branch in their right hands. They are all in complete silence. There is something both awesome and terrible about the sight of this gathering of men.

Meanwhile, the King has made his appearance at the entrance of the kraal. He extends his hand majestically towards the 20 black oxen placed in front of him, all lowing loudly. This marks the beginning of the festival.

It is opened with a solemn dance. Three Queens, clad in goatskins fastened with belts adorned with trinkets come out together from a hut near the kraal and advance to the middle of the semicircle. At a given signal all the soldiers stand to attention with an attentive eye and distended chest. They tap the ground in unison with their right feet. Then, all exactly together and in perfect rhythm, they raise and lower, advancing and withdrawing their mimosa branches. Simultaneously these thousand warriors begin a wild and powerful chant, but a monotonous one as it consists of only two notes, interspersed with a sort of neighing sound which makes a clashing noise like cymbals. These uniform movements and rhythmic sounds are accompanied by the posturing of the queens who execute a warlike dance. This dance which repeats over and over again the same movements, goes on for two hours. However, after a while, the queens are replaced by other queens. At each of these pauses in the ceremony the warriors all give a long and startling whistle. All present, including the King, the chiefs, the officers and the thousands of women and children crowded in the far ends of the semicircle, follow and accompany, so to speak, the movements and singing of the warriors. From a distance, the noise of this festival is not unlike the dull roar of the stormy scene as heard at a distance from the beach.

From Journey to Bulawayo – sketch by Fr V. Croonenberghs of the Great Dance of the amaNdebele, the artist in the foreground

After some two hours of the somewhat tiring exercise, the King leaves the entrance to the kraal and advances into the veld. The Khumalo’s or chiefs come to meet him. Bowing deeply, they hand him a mopane branch and present offerings of wheat, maize and the first fruits. The King eats a few grains. Then, in a sort of ceremonial purging, he pours water three times over the first fruits of the harvest. Then he retires to the royal palace. A piercing whistle followed by a great roar signifying patriotic and religious applause, follow his departure until he is disappeared from view. Thus ends the festival of the New Moon, or the little Dance.

Now the people in their turn are allowed to eat the new season’s produce. Before the ceremony, before the King had first tasted them, no one would have dared to touch them. The transgression of this law would mean death. Who would have thought that here, in the heart of Africa, we would find traces, somewhat obscure admittedly, of primitive religion and of one of the principle festivals of the children of Israel?...

…This letter from Gubulawayo follows on 12 February 1880. In my last letter I described the festival of the Little Dance or the New Moon of Summer. I must now give you a few details about the great annual Matabele Festival which is also called the festival of the Great Dance, or of the Full Moon, or of the First Fruits. The Little Dance, similar in character, is a sort of preparation or rehearsal for the great festival. The latter must always take place at full moon of the first month which follows the summer solstice (21 of December in the Southern hemisphere) This year, the full moon is on the 27 of January, but the Matabele calendar is not always very accurate. This is probably the reason why instead of celebrating the Dance at the full moon on the 27 January, the Matabele celebrated it later, on the evening of the 31st.

King Lobengula, delighted with my sketch of the First Dance, has asked me to paint for him, on a very large canvas which he wishes to send to chief Umzila[xvi] King of the Abagasa, the principal scenes of the great festival. On learning this, I made advance preparations in order to do this work in a suitable manner. A few days in advance I took my measurements and outlined in the background the magnificent sight of the hills surrounding Gubulawayo. In the foreground I marked out the position in which the King and the chief indunas would probably stand, from my recollection of the Little Dance. On the eve of the ceremony I was busy sketching on the site when the King approached me. He was curious about my drawing technique, then went on to enquire bluntly about the exact spot from the canvas that I planned to place himself. I showed him this place of honour and he was proud and delighted and his royal face beamed with pleasure…

…When I described the Little Dance I spoke of the great theatre for that festival, the plateau, the King’s palace, the cattle kraal and the great open space in front of it. This open spaces is called in Matabele the ‘Isibaia’ (kraal) or the ‘Isibaia zimbozi’ (of goats) rather as one might speak of the Athenian Agora or the Roman Forum. For the rest of the year the Isibaia enjoys a habitual calm which is completely oriental, or rather tropical. This great plain is furrowed by the cattle, the goats and their herdsmen, all wandering around with slow, tired steps. The native huts are built around the edge of this plain and, behind these is the great wooden stockade called the ‘Umuzi wabulawayo’ (the Gubulawayo boulevard) which is a sort of external fence to protect the flocks and the inhabitants against wild beasts and, if necessary, against their enemies. The white men live beyond this fence.

For several days before the festival, and especially on the actual day itself we saw numerous bands of Matabele warriors arriving on this public square, usually so quiet and peaceful. These were the regiments called by the King from all parts of his territory. If you saw them in the distance, with their heads crowned with black ostrich plumes, you might almost take them for the Queen's Grenadiers in tall busbies. But when close at hand you would quickly realise your mistake. Their only uniform is a leopard skin on their backs. They weapons consist of an ox-hide shield which they hold in their left hands and of assegais and knobkerries which they hold in their right hands. The festival lasts for four full days during which the King feeds all his people. In return he receives many gifts from his faithful subjects.

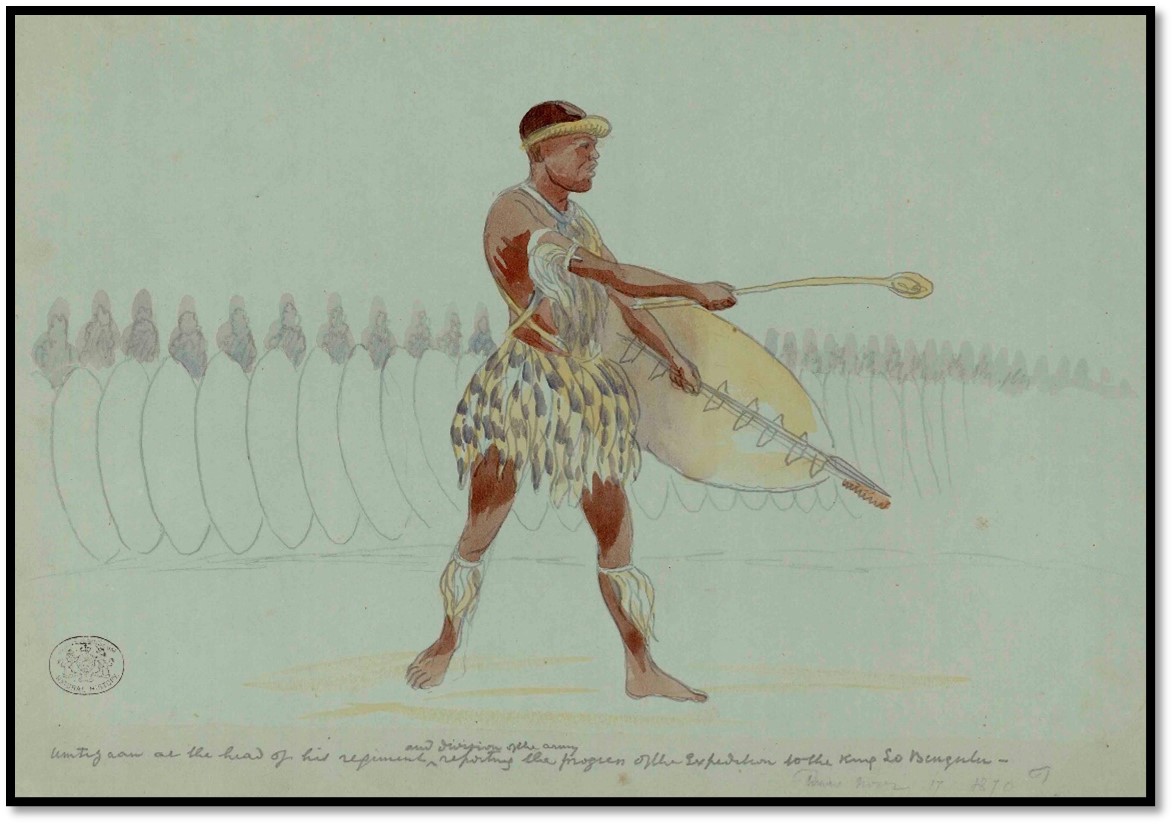

NHM (London) No 62: Thomas Baines watercolour of Umtigan at the head of his regiment

The first day is the day of the Great Dance, strictly speaking. At about three o’clock in the afternoon all the warriors are in their assigned positions. Lobengula appears at the entrance to his cattle kraal in front of the vast open space. He makes me sit on his left hand side, with my drawing paper, at the entrance of the Isibaia. Then he climbs a small hill formed by the accumulated dung of all the cattle of Gubulawayo. From this point he extends his right hand majestically towards the eight thousand warriors who are standing in orderly ranks around the semicircle in lines three or four deep. At this signal, the battalions give a great shout “Yebo, yebo, yebezu.” This is the royal salute. Then, while remaining stationary, the soldiers raise and lower their feet in unison. Also in unison they shake their shields as they raise and lower them. And again in unison they raise and lower their knobkerries which appear and disappear, in a most perfect ensemble above the eight thousand busbies adorned with ostrich plumes. This is the military dance.

From time to time these exercises are interrupted. At these moments, the bravest of the captains appear in the middle of the semicircle and demonstrate the exploits of war. They love to display their strength, their skill and their flexibility at these manoeuvres. They are really terrible to see when they rush upon their enemy with ferocious looks and frightful cries. When one sees them, one gets an idea of that bloody battle fought between the English and the natives of Cetewayo.[xvii]

When the chiefs have concluded their war-dances, I see on my left, emerging in two long files from the nearby huts, the procession of the queens magnificently adorned with tawdry finery of all kinds and with ribbons and shawls in vivid colours. In high pitched tones they sing the royal salute: “Yebo, yebo, yebezu” With slow and rhythmic pace they advance into the semicircle. In one hand they hold the conjugal head-ring, the sign of fidelity, and in the other they bear a green branch as a symbol of peace. They perform quiet dances and then retire whence they came. By now it is almost six o'clock in the evening and the setting sun, so very lovely here, is casting golden and reddish rays, adding something of poetry to this strange and primitive scene. You would think you had been transported to the time of the patriarchs in Arabia or on the plains of Chaldea. Once the sun had set they all retired to their tents or among their friends to sit down for the feast and to enjoy a well-earned rest.

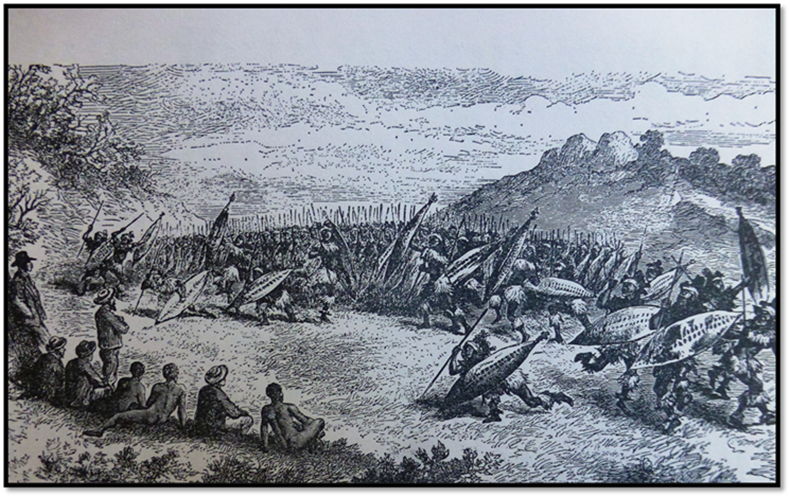

Illustrated London News; warriors dance at the Inxwala

The next day, the second day of the festival, we were to witness a completely different spectacle. At midday, when the sun is directly above our heads, pouring down its burning rays, we see a crowd of Matabele warriors rushing like an impetuous torrent towards the district where the white people have their houses. They are headed by the King who is wearing a gold belt, all sparkling on his black skin and a green sash around his shoulder. Only the King may wear a shoulder scarf in this colour. He walks along leaning on his assegai. Suddenly he stops. The human flood at his heels gives a dull roar. The chief throws his assegai and it whistles through the air and hits the ground about sixty metres away. A group of the warriors dashes forward, competing to see who will run the fastest. Soon one of the warriors, proud of his exploit, brings back the royal assegai victoriously and gives it to the great prince, ‘the King from below the mountains.’

This military ceremony is symbolic. When he receives back the assegai the King says: ”He who loves me obeys me in all things, as has done this faithful warrior who has followed from afar and brought me back my assegai.” Deafening cries greet the winner and applaud the King’s words. Finally the wild crowd returns to the ‘Isibaia Zimbozi’ and everything becomes silent once more.

The third day of the festival is the sacrifice, or rather the massacre, of the victims. Standing near the cattle kraal on the little hill, which I have already mentioned, Lobengula gives the order to bring forward the victims destined for the sacrifice. A little later we see two to three hundred horned cattle arriving in the middle of the open plain. They are headed by ten magnificent pure black oxen. The King looks with satisfaction at the huge herd. Then he extends his right hand towards the beasts gathered in front of him. This gesture signifies that everything living belongs to him. The people reply with their patriotic cry: “ Yebo, yebo, yebezu” (Yes, yes, everything belongs to you who are great)

After that, the beasts are sorted and arranged in the order in which they are to be sacrificed. They are led into the middle of the semicircle where stands the induna appointed as sacrificer. This induna advances slowly towards the first victim, held by four strong young men. Then, with a quick movement, he plunges his assegai into the body, between the ribs and the shoulder, pushing it as far as the lung. The animal gives a dull bellow and all is finished. With the blood pouring from its nostrils, it manages about two paces and falls dead. This process is completed with the most astounding rapidity. The space of one hour is sufficient to sacrifice a hundred beasts. The bodies of the black or sacred oxen are dragged to the King’s kraal. Their flesh and blood will be used as philtres and medicine and probably also for the feasts of the Amazizis (witch doctors) The other animals, cut up on the spot, are distributed to the people who spend the night gorging themselves on meat and utchwala (beer)…

NHM (London) No 64: Thomas Baines sketch of Lobengula’s warriors

Finally, there dawns, with radiant sunshine, the fourth day of the Matabele Festival. The day is consecrated to the ceremonies of the First Fruits and should offer a more poetic sight than the massacres of the previous day, while remaining most realistic.

At the hour when the sun has topped the mountains to the east, that is to say, about nine o'clock in the morning, Lobengula goes to the middle of the Isibaia. As I have already mentioned you can see that this Isibaia is similar to the Agora of antiquity.

There is an immense pyre in the middle of the open plain and it contains the bones of all the oxen and all the other animals killed during the past year for the needs of the King and the people of Gubulawayo. In front of the pyre has been placed the King’s seat, a somewhat primitive throne, consisting of a plain redwood chair. The King seats himself and then lights the fire. From time to time he gets up and stirs the fire himself with his assegai. Slave women are kept constantly busy stoking and encouraging the flames.

While thick clouds of ‘sacred’ smoke covered the plain and fill the not very sensitive lungs of the sons of the tropics, the eight thousand warriors ranged themselves around the pyre, squatting on their haunches and completely still. Behind them crowd the rest of the people, women and children. Within the semicircle, close to the fire and about five paces from the front rank of the soldiers, the witch doctors, or Amazizis, are to be seen, sitting on the ground alongside young slaves who are peeling the new plants, separating the sheaves of maize, shaking out the ears of amabele (native corn) These fruits are offered to the king who gives them the triple libation.

At the same time, the queens still dressed in their richest finery, walk in procession in front of the assembled people. They go several times round the pyre singing hymns to the spirits of Machoban, the father of Mosilikatse, of Mosilikatse, the father of Lo Bengula and of Lo Bengula himself, ‘the prince of peace, the prince of war, the great King, ‘enkos amakos’ (the King of Kings)

During these rather lengthy ceremonies the Matabele women bring around roast meat the smell of which is fragrant in the air and helps to modify a little the acrid smell of the smoke rising from the pyre…

…This, then, is a somewhat incomplete description of the great Matabele festival.

NHM (London) No 77: Thomas Baines sketch of a young Matabele warrior

The Inxwala in 1889

John Cooper-Chadwick[xviii] was camped at Gubulawayo before following the King when he moved to the Imbiso (Imbezu) kraal[xix] about 30 km from Gubulawayo and he says: He (Lobengula) seldom remains long in one place but travels about in his waggon to the different towns, followed by his bodyguard and a large contingent of queens , indunas and members of the royal family. Strangers visiting the country are expected to follow him and usually do so, though it is not compulsory and they can remain at Gubulawayo, which is the white man's town…

The Great War dance, which takes place every year is the principal event in the country and the various customs and ceremonies connected with it may be of interest. I witnessed two of these dances while in the country and the first, which was held in February 1889, I will try to describe.

For weeks before, endless streams of girls were to be seen carrying calabashes of beer to Gubuluwayo where the dance is always held and all around the town several camps were being erected for the different impi’s that the King might select to take part in the dance.

The ceremonies, several of which closely resemble the old Jewish customs,[xx] usually last about a week and during this time no white men are either allowed to enter or leave the country and all staying with the King are expected to attend at the dance itself, which only lasts one day.

During the ceremonies, the King is no longer King and the government of the country is in the hands of the regent (Umthlaba) no violence or bloodshed is allowed, nor can anyone wear anything of a red colour, which signifies blood, but striped or gaudy coloured calicos or shawls are in great demand.

This short respite from killing is more than evenly balanced by the number of people that are afterwards condemned to die by the witch doctors during their ‘smelling out’ operations.

On the morning of the dance, the regiments file into the large space facing the royal quarters and formed in a long crescent about three deep. Each impi as it marched in was attended by a crowd of women and girls belonging to its town, all shouting and singing the praises of each one’s particular warrior.

The numbers were estimated at eight thousand and made an imposing sight for a European to witness. Each warrior wore a headdress of black ostrich feathers and a cape of the same, which gives the shoulders the appearance of being very broad. Hanging from the waist was a kilt made of strips of tiger cat or other skins and on the legs and arms fringes of long white ox tails. They all carried the large ox-hide war shield and assegai’s in the left hand and in the right, the dancing sticks with which they struck the shields in keeping time to their songs. Each impi could be distinguished by its different coloured shields and perfect order and time was kept while the indunas marshalled them into their places. The older and more tried regiments, (Amadoda or ringed men) wore bands of otter skin on the foreheads and long crane feathers.

From Gold from the Quartz: An impi dancing before Lobengula – sketch by Thomas Baines that he gave to Lobengula who hung it in his brick house and then gave it to E.A. Maund

Before coming into the King's presence all the soldiers must wash and be purified by the witch doctors who sprinkled medicine over them. Lobengula was seated in his bath chair in front of the sacred cattle kraal and facing the centre of the line. He had lately been ‘doctored’ for the occasion and his body was covered with streaks of black paint. The old man looked particularly savage as he was suffering from gout. Accordingly as the impi’s passed they thundered out the royal salute “Kumalo” at the same time stamping the ground with their feet and beating time on their shields. The white men were collected near the King, but no one is allowed to stand behind him and in the royal quarters unlimited beer was served out to any who might require it.

The proceedings began by Mazesi, the head war doctor, who is an important personage, coming out to inspect the troops, after which he delivered a harangue, exhorting them to fight well in battle and die for their King; he then performed certain mysterious spells and incantations to ward off any evil or witchcraft and prophesied all the victories they would meet with. The warriors then chanted the national chorus and executed a kind of clumsy dance, keeping however, perfect time and beating their shields with the sticks. Occasionally a shrill whistle would commence at one end of the line and continue the whole length of it, gradually reducing in sound, until it last it faded away. This was a wonderful imitation of a whizzing assegai and the effect produced was perfect. Now and then a tried warrior would spring forward from the ranks and with a succession of high leaps into the air, would drive his assegai into the ground according to the number of men he killed in battle and was duly applauded according to his merits.

About 50 of Lobengula's wives then slowly came out of their quarters in Indian file onto the parade ground – indeed with most of them, fast walking would have been an impossibility; they all wore bright coloured satin shawls and each carried several pounds of beads gracefully arranged in festoons around the neck and waist. Many had brass bangles, fitting close, from the ankle to the knee and others wore beads in the same manner. All were in the royal feathers of the blue jay, arranged sticking up in their hair to form a sort of coronet, which had a pretty effect. They all carried long white wands in their hands, which they waved about, and then, breaking up into small groups, moved slowly up and down in front of the troops with a peculiar motion like waddling ducks.

A line of witch doctors then appeared, each carrying a little calabash of some unsavoury concoction. These worthies created a considerable stir and everyone had to make way for them and let them pass on the right side, even the King himself got up to let them pass and they then disappeared with the medicine into the sacred cattle kraal. The whole line been charged furiously with lowered assegai’s up to the King, gradually closing in so as to hem in the whites as well; indunas were stationed near us to prevent them coming too close or indulging in any horse-play that the young bloods were quite capable of. They then retired again into line and the sacred black cattle were driven past.

The national custom of turning them out of the kraal gates into the veldt and having them brought back by an impi was then performed. The cattle, when released, went off with a full gallop, but they were quickly headed by the active young soldiers who, laying down their shields and assegai’s, ran after them at full speed and soon drove them back again. The thousands of native spectators filled the immense enclosure in front of the warriors and troops of dancing girls paraded about, dressed in full costume of beads and coloured handkerchiefs.

Lobengula then retired to his private quarters and after a time reappeared in full war paint. The ‘Old Buster,’ by which name he was familiarly known to whites, looked the perfect picture of a savage King; his costume was the same as the soldiers, but more complete in detail and of finer quality, his kilt of monkey skins, which is only worn by royalty, being the only distinguishing mark. The King now executed a kind of ponderous elephant dance in front of the admiring nation, who applauded loudly; the dance consisted of slowly lifting one immense leg and then the other from the ground and occasionally executing a kind of pas seul. By the King’s expression, no doubt he had twinges of gout during the performance and was glad when it was over.

The great feature of the war dance took place towards the conclusion of the day’s ceremonies, that of Lobengula throwing the assegai. The King, escorted by the youngest regiment, proceeded outside the main gates of the kraal and then threw the assegai in the direction where it is supposed he intends sending his troops to fight for the coming year and the amajaka (majakas - young soldiers) following would stab the ground with their assegai’s as a signal that they were obey the King’s orders wherever they were sent. Towards evening, the impi’s were dismissed and again filed past the King, shouting the magic word “Kumalo” and when outside the kraal gates they dispersed with a mad rush to their various camps, singing and shouting like demons.

The following day was set apart for the killing of cattle when the King selected some three hundred from the national herd and gave them to the regiments. The indunas of each impi then set to work stabbing the cattle, certain of which when killed was set aside for the Umlimo (spirits) A wild scene took place, the maddened and infuriated wounded cattle rushing about in the confined space of the enclosure, which made it difficult to avoid their long, sharp horns. When at last, all were killed, the meat was cut up to be distributed the next day. The following morning when I entered the King’s quarters a busy scene presented itself – that of the soldiers cooking the meat. Hundreds of fires were scattered on all sides and round each were squatting groups of warriors who were engaged in cutting up lumps of meat and putting them into huge earthenware pots each capable of containing a quarter of a bullock. The pots were supported on three stones with a fire in the centre. The process of cooking the meat is peculiar and makes it very tender, if not particularly clean. Half a pint of water is first put into the pot and then a few small green branches of trees, over them the meat is packed in lumps, all the bone having first been carefully extracted. The lid of the pot is then put on and hermetically sealed to prevent any air entering, a slow fire is kept under and the meat allowed to gently simmer for a whole day. It is, in fact, steamed, not boiled and the little water and bushes prevent it from burning. That night was spent in devouring the meat and next day the beer drinking began. Native beer only keeps a few days without getting sour and as some of this has been stowed away at least a few weeks before the dance, it must have tasted like vinegar; but that to a Matabele warrior is a mere trifle, as was shown by the enormous quantities each consumed. Certainly eating and drinking form a prominent part of the rites during the Matabele holy week.

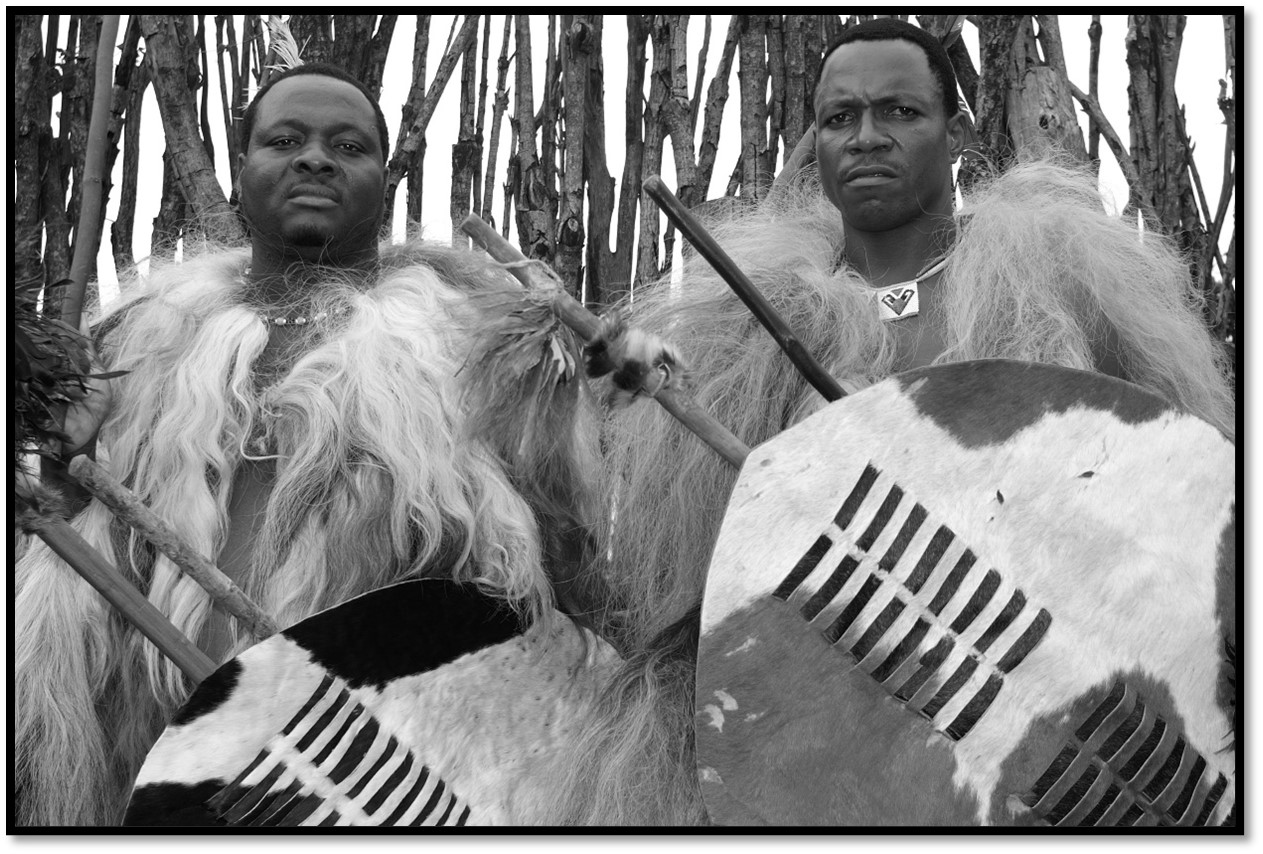

Wikimedia: Men dressed for the Incwala in Eswatini

The Inxwala in 1891

Rev David Carnegie in a chapter named the War Dance and the First Fruits[xxi] states: The dress of the men on this occasion is very picturesque and displays to perfection the peculiar, though not ungraceful, gait of the ‘noble savage.’ On his forehead and pointing upwards is a long crane feather, fixed by means of a bow of otter skin which ties at the back, while on the crown of the head is a huge black tassel of beautiful short black ostrich feathers and on the shoulders and halfway down the chest is a hood of the same. This is the most graceful part of the uniform of the men. Halfway down their arms and legs, ox-tail hair is tied, mostly white, while round their waists are hanging all sorts of skins - monkey, tiger (leopard) cat, rock rabbit and above them, calicoes - spotted, striped, black, yellow and white. Add to this the large war shield in his left hand and spear in his right and there the Matabele stands - the proudest invincible warrior whoever served a King.

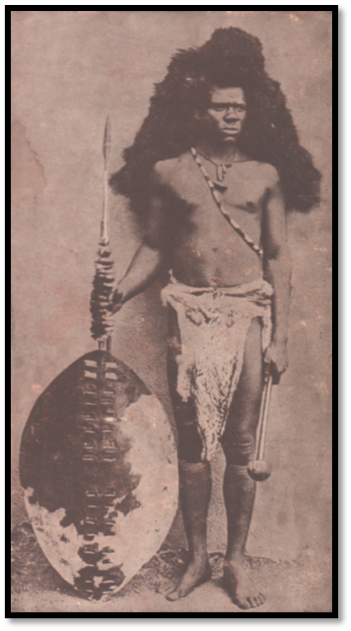

Photo from Gold from the Quartz; a Matabele warrior in full military dress

These all dance in a semicircle in the large enclosure and within this again the girls and queens dance. All have sticks in their right hands from three to nine feet long. Among the girls and queens pink beads, yellow beads, blue and spotted calicoes prevail. The blue jay birds’ feathers are stuck fantastically in the heads of all the queens, some of whom wear long kilts of black and pink beads down to their knees, while others tie round their bodies pieces of spotted calico in all sorts of ways. They all sang the same song at one time, march slowly forward and keep time to their song by stamping on the ground. The hand with the long, thin switch goes up and down according to the music. The girls from the town sing abreast, while the queens come out from their quarters in single file. The men have short sticks with little knobs at the ends. No spears are used on this occasion.

This great feast last for four or five days, its real object being to thank the chief, who prays to the spirits of his ancestors for the gift of fresh corn and food and to show their loyalty by singing his praises. Many have ulterior objects in going to this dance, such as eating beef and drinking beer.

Between each dance the Matabele count twelve moons, so that it is really their Christmas festival and takes place between the end of December and February. If the rains are early, the time will be altered accordingly. Before the time messengers are sent out to bid the people to the feast and they come, as we have seen, and gather each regiment by itself outside Bulawayo.

During all these ceremonies no business of any kind is done; no waggon dares leave the town while the dance is going on. The chief is relieved of his duties, he does not rule, the doctors of the dance - the masters of the ceremonies - have all the power and they give orders about the time it is to be and their orders are obeyed. On the first day of the dance, when everybody has arrived, the important business is the handing over to the chief of the number of oxen which have been brought from the different towns throughout the country. These are all numbered and handed over to the chief inside his kraal as an offering from the people to the spirits of his ancestors. The cattle are carefully shut up in the kraal all night and on the second day, the slaughtering begins.

At early dawn all the army is up and singing the war songs outside the cattle kraal, while the chief and his head priest are inside selecting oxen which are to be slain. Here the chief offers up his prayer. Here so and so takes this ox. The chief points out a certain number and the dance doctor, who is skilled in spearing cattle, soon has all his victims groaning on the ground. None are killed outside the gate, all must fall within. There is no choosing as to what colour or size, only they must be speared by the priest. He spears each one behind the left shoulder, some stand minutes afterwards, others drop immediately and are soon dead.

From A Visit to Lobengula in 1889: a young Matabele warrior overturning an ox

No one may go inside the kraal during this operation, but when it is completed the command goes forth to skin the cattle. The singing of war songs, which has been going on outside all this time, now ceases and there is a regular stampede of men with knives of all descriptions running here, there and everywhere. So many oxen, perhaps sixty, eighty or a hundred, have been slain and each regiment receives its number and sets about skinning them at once. There is no confusion, for each man knows where he has to go and what he has to do.

The skinning over, the meat is halved, quartered and cut up and made ready to be carried away to one or more huts, in which it is piled up in heaps for the night for the spirits of the chief’s ancestors to come and eat their share first of all. This day none are allowed meat of any kind except the feet, tails and entrails of the oxen.

The third day the singing and dancing continue. The excitement grows more intense towards afternoon when the chief appears in full war dress himself and throws a spear from the gate of the kraal into the enclosure where all the people are. At this point the shouting, yelling and tumult are something awful. They come gradually closer and closer, right to within a few yards of the kraal gate to have a sight of his majesty…

Illustration from Among the Matabele of King Lobengula

…At early morn after the spirits have had their feed, the beef is all taken from the huts and put in earthenware pots, some fifty or sixty of them. It remains cooking all day, the pots being covered with broken pieces of others and smeared with cow dung and set a-boiling.

Towards sunset the meat is taken out and handed round, the people all sitting down on the grass in the presence of the chief to enjoy their repast…Next day they may continue their dancing, but this feast over, they soon disperse and go to their own homes. There are various favourite dances, such as the corn dance, at the end of which one points towards his garden with a stick…On the fourth day the dance is practically ended and between this and reaping time there is nothing for the people to do but sit and plot and plan for one another's death. It is in these months that so many are killed for witchcraft.

After this annual festival the chief as a rule leaves Bulawayo for his other country mansions, perhaps Emkanwini, Inyugeni or Umvutcha[xxii] which are within a radius of six miles of the large town.

Besides the great war dance, there is an annual ceremony of the first fruits. No one dare for his life eat any green food, such as mealies, or sweet reeds before observing this ceremony. It takes place just immediately after the big dance. The principle towns luma, i.e. bite first and those in the outlying districts follow. I went as an eyewitness to see this ceremony performed at a neighbouring town among the hills.

There are special doctors set apart for the occasion. The smaller villagers gathered together to the larger ones. I remember on my arrival seeing the doctor busy preparing his medicines in front of the people, who were arranged before him in the cattle kraal in a semicircle. In their hands were no shields or spears, only short sticks, which was a sign that they were about to perform or observe a custom of peace.

As I sat down the master of the ceremony rose and took a wooden dish in which there were some green leaves of makomani - a kind of vegetable marrow and clean water. This he put on the ground in close proximity to the people, who were all dancing and chanting a song. A giraffe's tail tied on a short stick was in his hand, which he dipped into this dish several times. Then he sprinkled the people. Returning to where I was sitting, he greeted me and expressed pleasure at seeing me there to witness the performance.

Just in front of him were some sweet reed stalks, makomani and pumpkin leaves and two small bags full of medicines, which consisted of the usual native miscellaneous collection of snakes’ skins and bones, feathers of wild birds, bones of wild animals, twigs and leaves of various trees. A log of wood was bought and with his small axe he chopped off from each of his bundles of ‘medicine,’ roots, bones and skins a little bit. These pieces he gathered together in a heap on a sheepskin, which was put there close by that for that purpose.

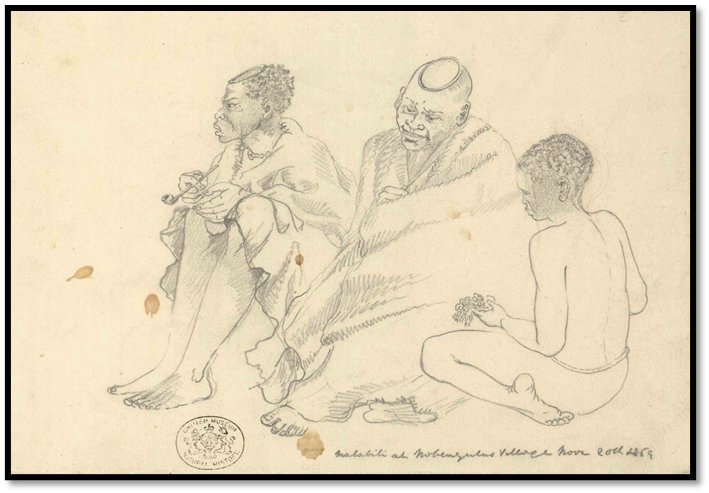

NHM (London) No 75: Thomas Baines sketch of Matabele at Lobengula’s village in November 1869

Two fires were now lit and a native earthernware pot was brought and balanced on three stones, while under it was the fire. A second pot, which was broken, was used to form a lid. Into the sound pot were put all the leaves and sweet reed and where the two pots met was smeared some cow dung, to prevent the steam from getting out. Another broken pot was used in cooking up all the chips of roots, bits of feathers and splinters of bones, but no lid was put on. Fortunately for me, the wind was blowing the smoke towards the people, who all this time were chanting their dirges about forty yards away.

Four reeds about three feet long were fetched and laid down besides this smoking broken pot in which was the smouldering, smelling concoction of roots and bones. At a given signal four men from the ranks approach on hands and knees towards this reeking, smoking mass. Each one picks up one of the reeds, one end of which he puts in his mouth and the other into the thickest part of this stinking smoke and with this he sucks one mouthful of smoke from the pot into his mouth, then he puffs it into the air, lays down the reed, spits once or twice on the ground and returns again to his singing. This they all do in batches of four in turns, til each one has tasted the wonderful cleansing power of the doctor's medicine. The ashes are afterwards taken out of this old broken vessel and put on a flat stone and by means of another round one are ground into fine dust, not unlike charcoal.

Next they bought a dish full of warm milk from a white cow, which was poured into this vessel, out of which the ashes had been taken and when the milk began to boil, the officiating ‘doctor’ threw back into it all this black charcoal-looking stuff, together with some white dust which made a perfume and stirred them all up by means of a long stick. As soon as this second potful of ingredients was cooked sufficiently, the singing ceased and the people all stood staring at this white frothy substance of which they were about to partake. They again came forward, but instead of using reeds they used their fingers, by dipping them into the hot milk and next putting them into their mouths. This was repeated three or four times by them all, when they moved away to their singing place again.

Attention was then directed to the other pot which had the broken pot for a lid, and in which were the sweet reeds and vegetable marrow leaves which had been brought fresh from their gardens that morning. The lid was taken off and all these leaves were eaten up by the people, only the stalks on which the leaves grow were brought back, together with the husks and the remainder of the charcoal stuff and put in the fire and all burned up, not a shred of any being left after the ceremony was over. While eating these green leaves the people strike themselves on their head, elbows and knees, signifying thereby that by means of this young crop - first fruits of the new season - they desire to be strong in head, arms and limbs to fight the chief’s battles.

To complete the performance, the priest, with his giraffe’s tail brush sprinkles them a second time with this milky charcoal substance, saying to them all the while, “Now you have observed the law of the land, now your offering has been given and your song sung. Go and eat the first fruit of your gardens, go eat, be filled and rejoice.” This is all, they disperse and the ceremony ends…

References

A.A. Anderson. Twenty-Five Years in a Waggon in South Africa: Sport and Travel in South Africa. Project Gutenberg eBook #40830

D. Carnegie. Among the Matabele. The Religious Tract Society, London, 1894

J. Cooper-Chadwick. Three Years with Lobengula and Experiences in South Africa. Books of Rhodesia Vol 1, Bulawayo 1975

R.S. Roberts (Editor) M. Lloyd (Translator) Journey to Gubulawayo – Letters of Frs H. Depelchin and C. Croonenberghs, S.J 1879, 1880, 1881. Books of Rhodesia. Silver Series, Vol 24, Bulawayo, 1979

E.C. Tabler (Editor) Zambezia and Matabeleland in the Seventies. The Narrative of Frederick Hugh Barber (1875 and 1877-8) The Robins Series, Volume 1, Chatto and Windus, London 1960

E.C. Tabler. The Far Interior. Chronicles of Pioneering in the Matabele and Mashona Countries, 1847-1879. A.A. Balkema, Cape Town, 1955

Notes

[i] See the article Early traveller’s impressions of Gubulawayo under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[ii] The Far Interior, P111

[iii] There has been some discussion in Bulawayo about turning the large vacant area at the corner of Masotsa Ndlovu Avenue and Joshua Nkomo Street into some sort of cultural hub as the Inxwala Festival was held at this location during Lobengula’s reign with the kraal of eMahlabbathim nearby and is part of amaNdebele heritage

[iv] The Narrative of Frederick Hugh Barber, P105-6

[v] Isigodla, a circular stockade of long strong poles, planted and piled together vertically enclosing the King's residence

[vi] An umbrella to keep off the sun

[vii] Twenty-five Years in a Waggon in South Africa, Chapter 23

[viii] Anderson lists the main amaNdebele kraals as Amaboguana, Inyateen, Umkano, Umganin, Umhlabatine, Umslaslantala, Gubulawayo, Umgamala, Umslambo, Umshangiva, Manyanga and Mthlathlagela in his article Notes on the Geography of South Central Africa, in Explanation of a New Map of the Region in the RGS New Monthly series Vol 6, No 1 (Jan 1884) P19-36

[ix] Rev William Sykes of the London Missionary Society and were based at Inyati mission from July 1861 during Mzilikazi’s rule and died at Inyati on 22 July 1887; his wife dying in 1920

[x] Rev Francois Coillard was a member of Les Société des missions Evangelique’s de Paris and entered present-day Zimbabwe across the Limpopo river with three wagons in July 1877. They were robbed and bullied by local natives and sent messages to Lobengula for help. He sent an impi that arrested them for entering the country by a forbidden route and they arrived at Gubulawayo on 15 December 1877 and were present for the Inxwala.

[xi] George Phillips, hunter and trader at Gubulawayo from 1864 to 1890. Very much trusted by Mzilikazi and Lobengula and popular with the other traders. Lived in the region for 25 years and known as ‘Elephant Phillips’ for his size and strength.

[xii] Jan Willem Viljoen, hunter and trader travelled extensively and hunted during the dry season at Lake Ngami and the western edges of Matabeleland. In 1865 hunted Viljoen and Piet Jacobs were the first Boers permitted by Mzilikazi to hunt in Mashonaland. He, his wife and two sons-in-law hunted again in Mashonaland in 1877 – 1879. Well-liked by all, one of the greatest hunters in the region, died in the Marico district in 1891.

[xiii] Probably George Wood, hunter, trader and explorer died at Pandamatenga in 1882. His first journey along the Gwaai river in 1867 and then east to the Great Zimbabwe region the next year. Hunted in Mashonaland in 1870 going as far east as Umtigesa’s kraal on the Sabi (Save) river but his wife, mother-in-law Mrs Fraser, their baby, Paul Jebe and servants died from fever. Met with Thomas Baines, Leask, Gifford, Maloney and McMaster and Henry Hartley. Hunted most seasons after this in Mashonaland

[xiv] Actually Rev Coillard’s niece, Elise Coillard

[xv] Journey to Bulawayo, P232

[xvi] See the article The 1880 journey of Rev Father Augustus Henry Law S.J. and others to Mzila’s kraal in south-eastern Zimbabwe under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[xvii] The Battle of Isandlwana on 22 January 1879 was the first major encounter in the Anglo-Zulu War between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom.

[xviii] Three Years with Lobengula and Experiences in South Africa, P107-8

[xix] The Imbezu regiment was raised in 1874 and was Lobengula’s bodyguard

[xx] I think this is a reference to the Jewish Sukkot celebration

[xxi] Among the Matabele, P70-9

[xxii] See the article A Visit to Lobengula at the King’s Kraal or Umvutcha in 1889 – Lieut-Col. H. Vaughn-Williams recalls his stay after 57 years under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com