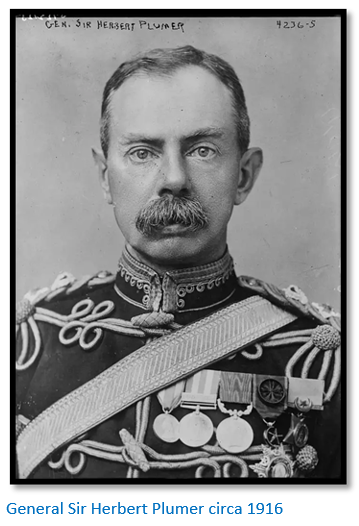

Field Marshall Herbert Charles Onslow Plumer, 1st Viscount Plumer, GCB, GCMG, GCVO, GBE and his connection with Matabeleland

Field Marshall Herbert Charles Onslow Plumer, 1st Viscount Plumer, GCB, GCMG, GCVO, GBE and his connection with Matabeleland

Herbert Charles Onslow Plumer (1857 – 1932) commanded Second Army from May 1915 to November 1917 and from March 1918 to the end of the war. Although Plumer’s walrus moustache and rotund stature inspired David Low to create the cartoon character of Colonel Blimp after his death, he emerged as the most popular British general of the First World War, partly due to Second Army’s prolonged defence of Ypres and its successful offensive at Messines in June 1917, but also due to his genuine paternalism and his singular talent for public relations. In the interwar period ‘Daddy’ Plumer’s reputation as the British soldier’s favourite general was cemented by his high-profile support for the fledgling Toc H movement. A devout high churchman, Plumer frequented the chapel at Talbot House in Poperhinghe and according to Charles Harrington, his principal biographer and former chief of staff, he marked the commencement of the battle of Messines by kneeling in prayer for his attacking troops[i]

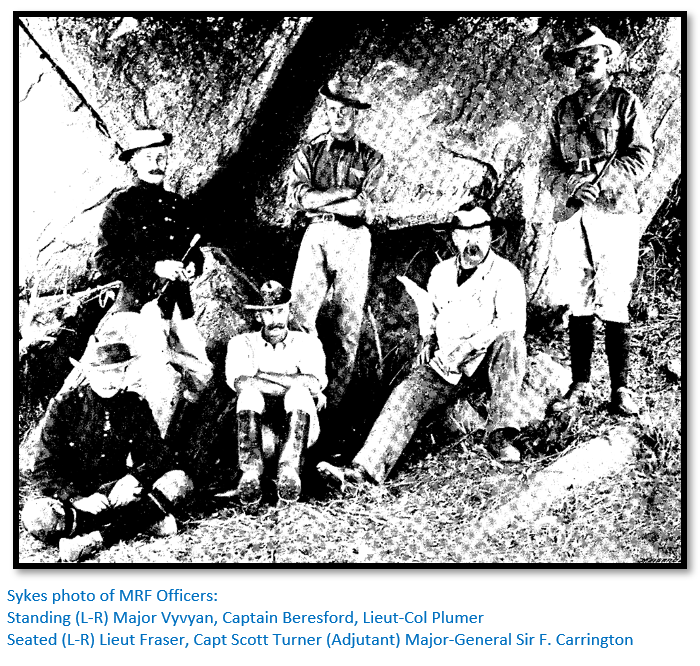

This article about one of Britain’s most illustrious soldiers does not cover his whole military career in any great detail but concentrates on his time in Matabeleland in 1896 during the Matabele Rebellion, or Umvukela. This is the same approach used for the www.zimfieldguide.com article on Lieut-General Robert Baden Powell of Boy Scouts fame - they both served as brevet Lieut-Colonels’ in the Matabeleland Relief Force in 1896 under the command of General Carrington.

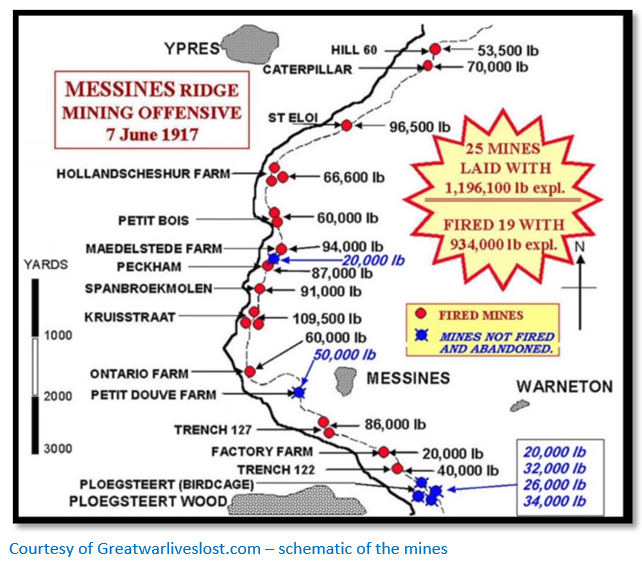

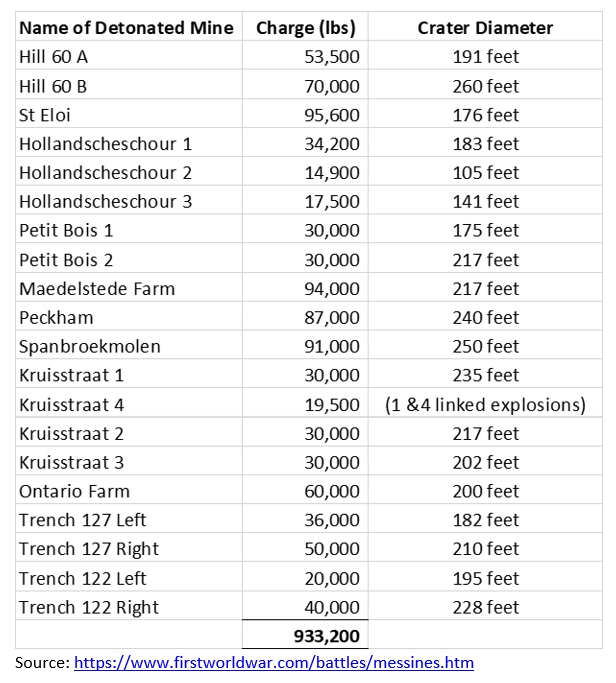

In June 1917 Plumer was in command of the British Second Army on the Western Front when the simultaneous explosion of a series of nineteen mines tunnelled beneath the German’s forward positions on the Messines ridge in Flanders , described as the loudest explosion in human history before the Hiroshima atomic bomb, instantly killed 10,000 German troops, thereby depriving the German 4th Army of the high ground south of Ypres and signalled the start of an advance of 3,000 metres of the frontline.

Plumer later served as Commander-in-Chief of the British Army of the Rhine and then as Governor of Malta before becoming High Commissioner of the British Mandate for Palestine in 1925 and retiring in 1928. He was instrumental in the formation of Toc H; one of the most successful ex-serviceman’s associations to emerge out of the war.[ii] Formally inaugurated in 1922 the association was conceived as an inter-denominational Christian movement dedicated to the ideal of ‘unselfish service.’

Both his biographers comment on the lack of original historical papers. Sadly Plumer instructed his wartime clerk and factotum, Sergeant Back, to destroy all his papers before his death in 1932. Harrington had copies of letters that Plumer wrote to his wife, but they were not the originals, so they may have been altered and these have also disappeared.

Note on his biographers

General Sir Charles Harrington was Plumer’s Chief-of-Staff of the Second Army in World War I and asked by Lady Plumer to write the memoir of her late husband which was published in 1935 titled Plumer of Messines.

Colonel Geoffrey Powell earned a Military Cross at Arnheim leading C Company of the Parachute Battalion at Arnheim endured bitter fighting against armoured German forces. After the war he held various military postings in Java, Malaya, Egypt, Cyprus and Kenya before transferring for the next 15 years into MI5. In his retirement he ran a bookshop and wrote military histories.

Early Military career

After school at Eton[iii] and training at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst where he passed near the top of the list,[iv] Plumer was commissioned on 1876 as a second-lieutenant in the 65th (2nd Yorkshire, North Riding) Regiment of Foot and sent to Lucknow in India becoming adjutant of the battalion in 1879 and promoted to Captain in 1882.

The same year the now 1st Battalion the York and Lancaster Regiment left for Aden which Plumer described as living in a perpetual dust-storm, although sea bathing and fishing helped relieve the boredom[v]

On their way home by HMS Seraphis in 1884 the battalion were diverted to the Sudan as part of the Nile Expedition to relieve Major-General Charles Gordon at Khartoum. On 26 January 1885 Khartoum fell to the Mahdist Army of 50,000 men; the entire garrison was slaughtered and Gordon’s head delivered to the Mahdi before they could be relieved by General Wolseley’s force.

At Kirbekan on the Nile the Mahdist Army on the heights was routed by a force under General Earle who suffered sixty casualties, including the General himself. Although not present at Kirbekan, Plumer was present at the battle of El Teb in February from which he wrote: “Just a line in pencil to let you know I am all right. We had a very rough time since we left ship and a pretty hot fight the day before yesterday, February 29th. I was not touched. The Regiment suffered 7 killed and 32 wounded…I have not attempted to tell you about the battle of El Teb. It was, as you know, my first experience. I could not give you any description of it because I was rushing about all the time. It seemed to be about half-an-hour, but I believe it really lasted about four hours or more…”[vi]

On the 15 March 1884 after the battle of Tamai where he was mentioned in despatches and awarded a 4th Class Medjidie and Khedive’s Star medal, Plumer writes: “We had an awful battle on Thursday. I hope I may never see a scene like that again. We lost poor dear old Ford. His body was horribly marked about when we got it, but I trust he was shot dead. Dalgety was badly wounded and I am afraid will lose his arm. We were very lucky not to have lost more officers, but we lost a lot of men, 32 killed and 22 wounded. Some of our best men. One longed to see active service, but I have seen enough to last me some time.”[vii]

Back in England

On 22 July 1884 Plumer married Annie Constance (née Goss - 1858-1941) and they would eventually have three daughters and a son. From 1886-7 he was at Staff College, Camberley where he passed out nineteenth of twenty-six officers in the staff examinations and re-joined the 65th at York before being promoted Deputy-Assistant Adjutant-General in Jersey in 1890. In January 1893 he was made up to Major in the 84th 2nd Battalion of the York and Lancaster Regiment and posted to Natal, South Africa leaving his wife and children at home, the expense of moving them being too costly for him. In Natal he did good work on reports and maps for the Intelligence department until the Regiment moved to Cape Town where he was joined by his wife and family.

In 1895 he was appointed assistant military secretary to the General Officer Commanding Cape Colony[viii] where his connection with Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe began.

Consequence of the Jameson Raid – ordered to Pitsani in Bechuanaland (now Botswana)

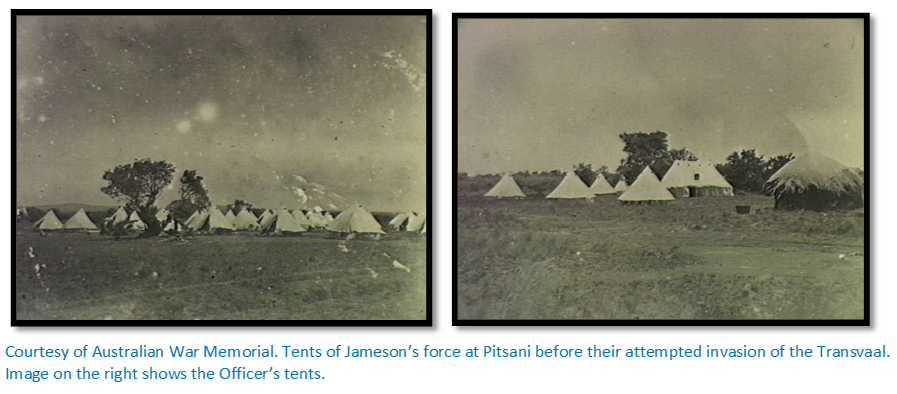

The Jameson Raid was launched on 29 December 1895 and led by Dr Leander Starr Jameson with a mixed force of about 400 British South Africa Company Police and other volunteers, many from the Bechuanaland Border Police which assembled at Pitsani, a railway siding and just inside Botswana. By 2 January 1896 the force had surrendered at the battle of Doornkop where Jameson and the others were arrested and interned. The raid was intended to trigger an uprising by British workers in the Transvaal against the Transvaal Republic which never took place.

On the last day of 1895 Plumer writes from Cape Town: “There seem to be wars and rumours of wars all over the world just now. There is every sign of trouble in the Transvaal. The Johannesburg people have issued a manifesto this morning practically demanding the franchise and there are all sorts of wild rumours about to the effect that they have stores of rifles and ammunition and Maxim guns at Johannesburg and are ready to make war on their own account. I fancy there will be trouble at any rate.”[ix]

On 5th January 1896: “You can imagine that during the last two days the whole place has been in a state of ferment about Johannesburg. The wildest rumours have been flying about. Direct telegraphic communication with Johannesburg has been interrupted and all telegrams have been sent via Pretoria, consequently their accuracy is always questionable. There is no doubt that Jameson surrendered after a lot of hard fighting. The Governor [Sir Hercules Robinson] left for Pretoria last night and he will be there tomorrow morning.”

Two days later a telegram arrived from Robinson requesting: “the General to send some officers to Mafeking and Bulawayo to prevent any attempt of avenging the Jameson disaster and to take from the Chartered Company’s officers any guns and ammunition they have there.”

From Pitsani Plumer wrote: “The camp was about 30 miles north of Mafeking. Six of us went, Newton, the Resident Commissioner, Col. Crofton, O’Meara and myself and two Bechuanaland Border Police…We reached the camp about 11am. It is prettily situated and well laid out. The tents were all standing and everything just as they had left them. The officers lived in mud and brick huts and they had a corrugated iron hut for a mess. They evidently did themselves pretty well. There was one officer and a few men left behind sick. Our mission was to take over the ammunition they had left, which we did. All the stores were left in an appalling state of confusion and no one seemed responsible. The men left seemed utterly disheartened. One sergeant told us the men did not know where they were going til they were paraded and that if they had a couple of hours to think it over, at least half would not have gone. It was one of the maddest schemes ever started. Everything pointed to a reckless waste and extravagance. The camp was pitched by a contractor at his own price; he had not been paid. Thousands of pounds worth of equipment, saddlery, ammunition, etc., was bought (not paid for, I think) and issued anyhow. The men themselves have not been paid, some of them for three months.

The camp was only three miles from the Transvaal border and the Boers, after Jameson’s defeat, could have made a raid on it and looted the whole place. They have made no attempt to do so, merely patrolling the border and I must say they have acted very creditably in this and many other ways.”

Ordered on to Bulawayo

From Mafeking Plumer was given the local rank of Lieut-Colonel and was given orders to proceed to Bulawayo via Gaberones. He arrived at Gaberones on 14 January 1896 and after taking over the arms and ammunition belonging to the Chartered Company [British South Africa Company] they were handed over to the Assistant Commissioner and Plumer left for Bulawayo alone.

He wrote of the journey of 922 kilometres in a Zeederberg coach: “The coach journey is the most horrible thing you can imagine. There was an unfortunate woman with a baby in it. It is a trial if one has to do a railway journey with a baby, but to travel in a coach for six days and five nights with one is beyond description. It was really terrible. You can’t sleep and altogether it takes more out of you than anything I have ever experienced before…”

From Bulawayo he wrote: “I am being put up here by a Mr Giffard.[x] He is a good friend of Jameson’s and went through the Matabele war[xi] with one of the columns. I have done practically all I have to do here, but I expect I may be kept here some time yet. What I had to do was to take over all the guns and ammunition belonging to the Chartered Company and also of course to prevent any armed force starting from here for the Transvaal. As regards the latter, there is not the slightest danger. Everything is perfectly quiet here. There was tremendous excitement at the time of Jameson’s surrender and if his life had been in danger I believe a number of men would have started off from here in defiance of the Imperial Government or anyone else. The devotion to Jameson is something wonderful; he is simply worshipped by all classes alike. It is the same wherever he has been. He must be a very remarkable man.

Everything seems prosperous and there are a better class of men up here than I had anticipated. They have started polo here and I had a game on Wednesday and enjoyed it. Everybody has been very civil and the Company’s officers have been most courteous. Of course, the taking over the guns and ammunition is only a formal matter, but still it might have been a rather unpleasant job.”[xii]

In Salisbury there was two .303 Maxims and one 7 pounder RML but there was very little ammunition for any of the guns except the Hotchkiss and none at all for the 12 pounder.[xiii]

Plumer met all the leading townspeople and this gave him not only advance knowledge of the country, but he gained their friendship. He estimated that there were only fifteen men still available from the Matabeleland Mounted Police, a forerunner of the BSAP – the rest had left with Dr Jameson on his abortive raid into the Transvaal. He also remarks on the recruitment of the Native Police, about 300 – 400 had been recruited who presented a very soldier-like appearance marching on parade, but many were soon to desert their recruiters.[xiv]

He was relieved by Captain Nicholson on 1 March and left Bulawayo on 12 March 1896 for Cape Town. On 1 April General Goodenough offered him the Military Secretary post but Plumer felt as a married man he could not fill the role and had contemplated leaving the military.

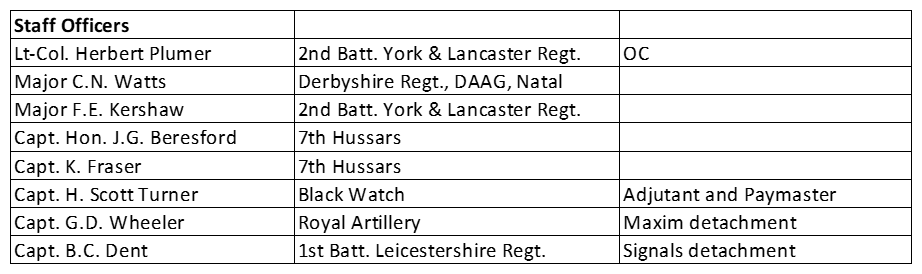

In late March 1896 the Matabele rebellion or Umvukela had broken out and Plumer wrote: “I am appointed Commander of the Force until Sir Richard Martin arrives from England. I am to go to Mafeking and enrol men there, collect horses, saddlery, etc., and then I hope to go on to Bulawayo. As 2nd in command to Martin, Watts is to come from Natal, Kershaw from here and I believe Beresford, 7th Hussars, is to be Adjutant.”

Matabele rebellion or Umvukela

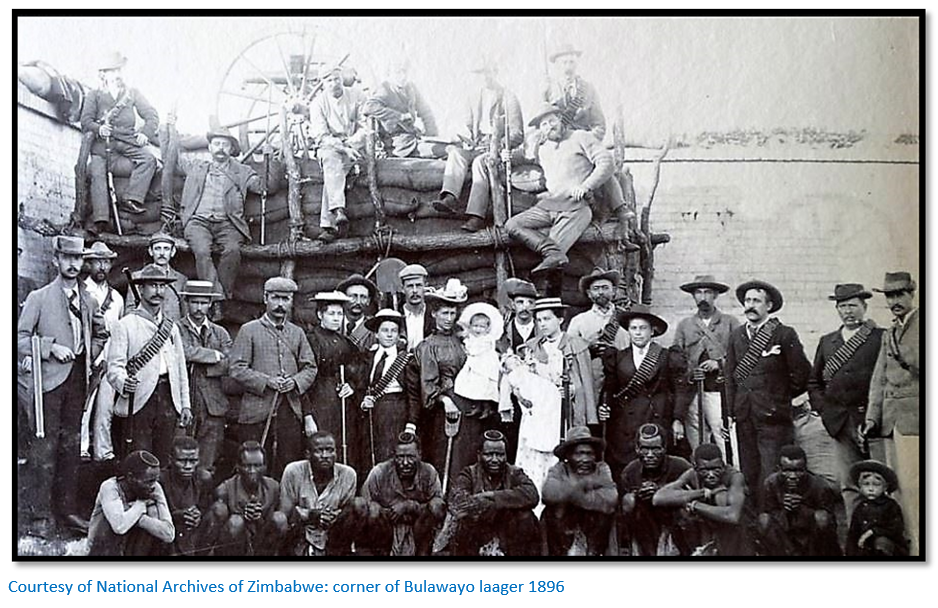

The plan for the uprising was sound, but its execution flawed. Bulawayo was to be assaulted at night and its inhabitants killed; then outlying prospectors, miners, traders and farmers attacked. But the killings began prematurely in Esigodini and once warned of the amaNdebele intentions, the settlors formed laagers at Bulawayo, Gwelo, [now Gweru] Belingwe [now Mberengwa] and Mangwe. Outside these places the amaNdebele, initially at least, controlled Matabeleland.

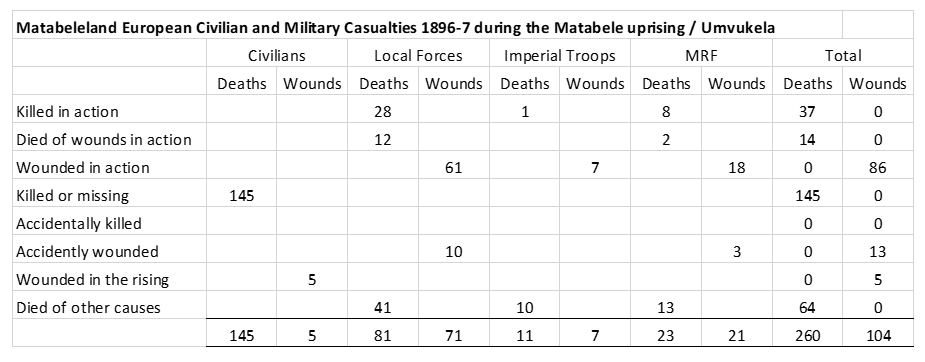

Many deaths were recorded in the last week of March and early April 1896 amongst the European population.

The British South Africa Company’s (BSAC) Administrator for Matabeleland who succeeded Jameson was Earl Grey[xv] and he wired south on 29 March 1896 for a relief force of 500 men to be raised and sent to Bulawayo; the Matabeleland Relief Force (MRF) was increased on the orders of the High Commissioner to 750 men[xvi] with 1,100 horses and mules with recruitment being carried out in Kimberley and Mafeking.

The British government determined that if the necessary troops need to be raised, trained and equipped it should be done by British regular officers and not colonials, although the BSAC would be paying for its expenses.[xvii]

Plumer sent to Mafeking to raise the Matabeleland Relief Force

On 2 April 1896 Plumer left Cape Town once again for Mafeking promoted to the rank of acting Lieut-Colonel with the tasks of:

- Raising a Matabeleland Relief Force (MRF)

- Escorting arms, ammunition and supplies to Bulawayo

- Defending the European civilians in Matabeleland against the amaNdebele.

Recruiting commenced at Kimberley and Mafeking, then the northern terminus of the Cape Government Railways (CGR) on 6 April, although 150 men were recruited in Johannesburg – all troopers were offered 7s. 6d. per day plus rations; a generous rate for the time.[xviii]

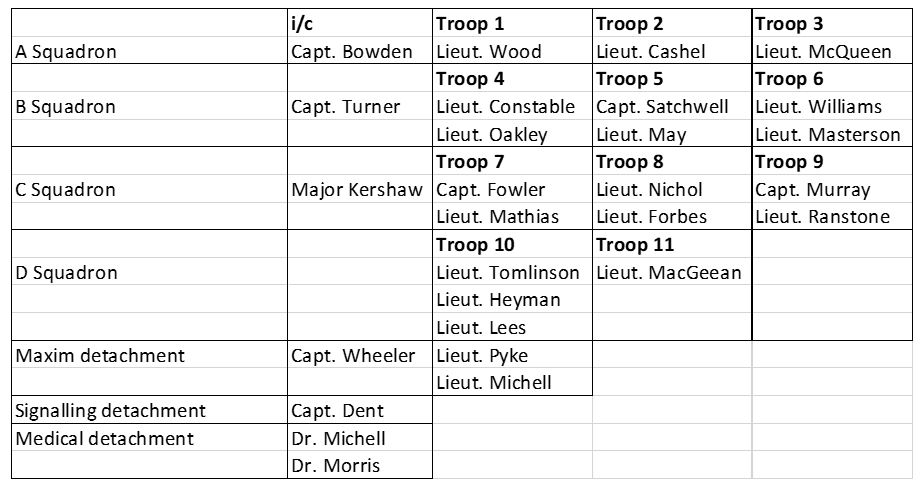

A military camp was formed outside Mafeking with all the men, horses, mules, supplies and equipment coming by rail. Many of the newly enrolled troops were old hands at fighting and had gained their experience in the Cape Mounted Rifles, Natal Police, the Cape Frontier Wars and the Bechuanaland Border Police and they included many Matabeleland Mounted Police who had accompanied Jameson and were released from gaol in the Transvaal Republic.

The Mafeking camp consisted of rows of tents pitched in the open near the railway station with an orderly room, stores, stables and parade ground. Sykes says the hotel-keepers did a great trade; the bars were full day and night and Julius Weil’s stores were reaping a rich harvest. Mafeking was in a state of excitement never before experienced. Every train full with military supplies and equipment, nights made hideous by braying mules and donkeys and the noisy carousing at the bars.

Frank Sykes wrote: “The heavy work of organising men and material as they came to hand at Mafeking was carried out under the direction of Lieutenant-Colonel Plumer, an officer whose capability and sound experience, though tried to the utmost, were fully equal to the occasion. To arrange, equip, provide for and despatch into the field such a force of mounted men, all within twenty days, was no small feat and alone would have sufficed to establish the reputation of the M.R.F. Commander as a military organiser of the highest order. The expedition with which preparations were effected was at the time commented on with surprise by those who were in a position to know what was entailed.”[xix]

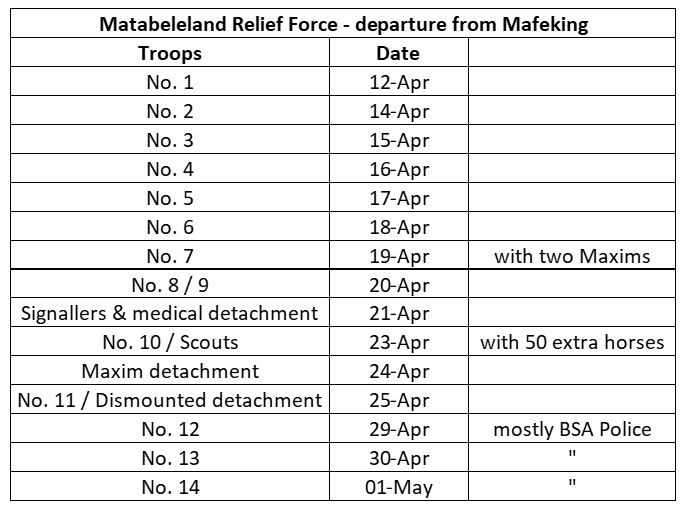

Training quickly got underway with the first troop leaving Mafeking on 12 April on the long march to Bulawayo and the last leaving on 1 May. In just three weeks 750 men were recruited and equipped as mounted infantrymen, 1,150 horses, 602 mules and 45 wagons with their spans of fourteen mules each had been despatched together with all their associated supplies of saddlery, medical equipment, food, weapons, ammunition which were carried with each troop. Fodder for the animals and men’s food was cached in stores along the 922 kilometre (573 miles) and water was short along the route so small parties allowed waterholes and wells to replenish between visits.

Speed is the essence of war

Sun Tzu said: “speed is the essence of war” and in this Plumer and his officers proved surprisingly adept. Moving the troops up to Bulawayo in small groups of fifty was a masterstroke – it improved discipline, it enabled the non-commissioned officers and officers to get to know the men, it weeded out the misfits and unfit, the men were trained on the march and it was the quickest way of getting manpower from Mafeking to Bulawayo.

Plumer considered that from a soldier’s point of view they would learn quicker in a small party than a large force the daily routine and knowledge of their duties and he would also be able to judge the capabilities of the officers and non-commissioned officers at the end of the march in Bulawayo. He says in the concluding remarks in his book that: ”there were a certain number of men who by their conduct seemed unlikely to add to the efficiency of the Corps and these were discharged.”[xx] This is a good example of Plumer’s early judgement in assessing soldiers abilities.[xxi] In addition the mules and wagons had just been purchased; it was felt they would be managed better attached to small parties who would render aid as the wagons contained their provisions.

Many recruits came from the Diamond Fields Horse and Kimberley Volunteer Brigade under Colonel Harris and about 220 officers and men were from the BSA Company’s Police who had left with Jameson from Pitsani on the bungled Transvaal raid - most recruits had served in various irregular corps or the British Army.[xxii] Inspector’s in the BSA Company’s Police were given the rank of captain and sub-inspectors as lieutenants. There were also a mixture of two hundred Zulu, Xhosa and Fengu recruits under Major Robertson, the so-called “Cape Boys” who provided excellent service.

Two additional Maxims came from the navy at Simonstown and ten were purchased new; all were .450 calibre.

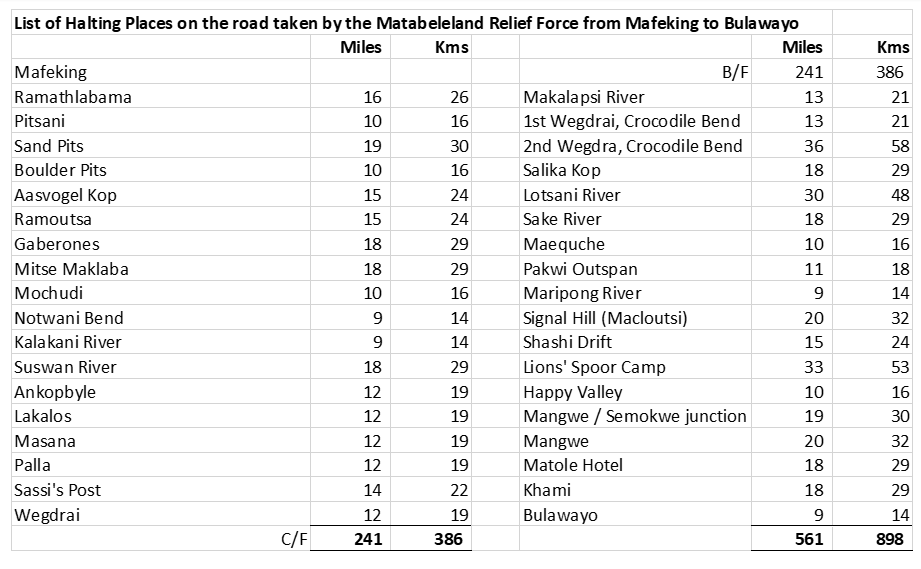

The detachments left Mafeking for Bulawayo on the following dates:

Each troop was addressed by Plumer before they left who offered advice and encouragement. Sykes says that “more often than not there were incidents connected with the departure of the troops which detracted somewhat from the dignity of the occasion.”[xxiii] Many of the horses were green and inexperienced and would not form up in their fours; the troop sergeant-major would make this quickly known to the rider. In would dig the spurs, down went the horses’ head and then the fun began. The horse would buck, the rider would cling on desperately and dig in his spurs again, but hampered by rifle, bandolier, water bottle and haversack, horse and rider would soon part company much to the amusement of the onlookers from Mafeking.

Supply and Logistics

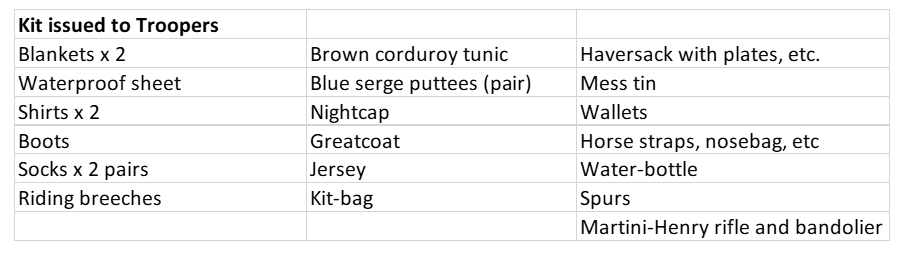

The troops wore cord riding breeches with either boots, leggings or puttees, brown corduroy tunics, felt hats turned up on the one side and cavalry cloaks or greatcoats and blue jerseys. Each was armed with a Martini-Henry rifle because there was 400,000 rounds of MH ammunition in Bulawayo. Kit carried per man was limited to 20lbs (9kg)

The official ration was a pound of meat and one and a quarter pounds of flour or meal daily, with tea, coffee, sugar, lime juice and a tot of Cape brandy, although the last two were in short supply. Sometimes the diet was augmented with rice or tinned vegetables. Thirty days rations were carried for each man.

The men made up messes of four to eight men, one of whom each day baked the flour on hot embers into small, hard ‘cookies.’ The results depended on the taste and skill of the days’ chef…some bullet-proofed cookies would have tested the digestive system of an ostrich. At passing wayside stores the men would buy jam, pickles or curry powder if they could afford them – the prices rising as the distance from Mafeking increased.

Each wagon carried a buck sail or tarpaulin which could be stretched between two halted wagons in bad weather. At night the troops rolled themselves into a blanket laid on a groundsheet and wore a night-cap.

It was far safer to drink from scoops in a dry riverbed than from a pond which might contain the body of a dead ox killed in the rinderpest epidemic. However the troops did not need reminding of this danger as the carcasses of dead animals were lying about everywhere and the air was full of the stink of rotting oxen.

The wagons were pulled by mules as there were so few surviving oxen, but mules require fodder, whereas oxen can survive on grass and so much of the wagon loads were made up of fodder needed by the mules. In addition oxen can pull around 8,000lbs (3,630kg) whereas mules only manage 5,500lbs (2,500kg)

Despite the long march and horse-sickness being widespread only 88 of the 1,100 horses died on the journey.

Two wagons were sufficient for each detachment of fifty men with a third wagon for every third or fourth detachment loaded with reserve ammunition and additional supplies.

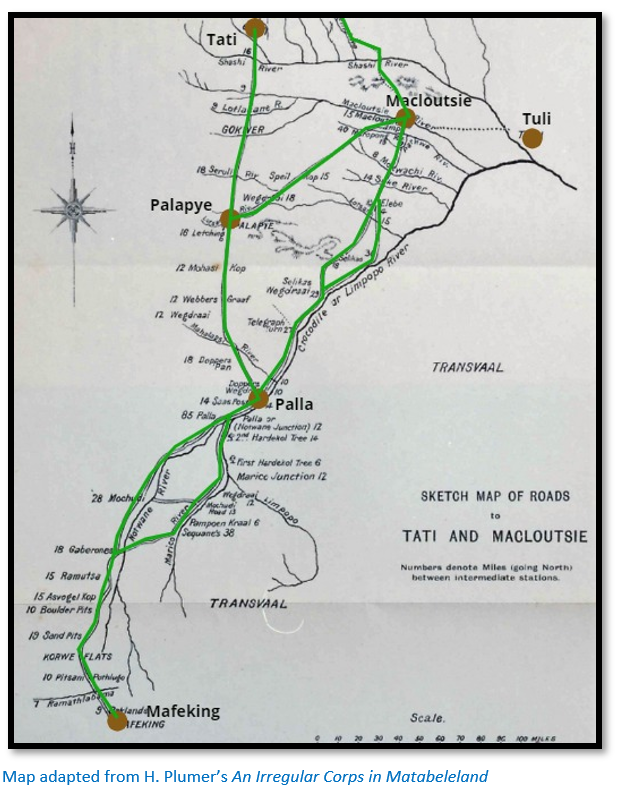

So much depended on the supply of fodder and water on the road that Major Kershaw went by coach to Palla and then purchased horses to ride and inspect all the halting places to Macloutsie.[xxiv] Non-commissioned officers were stationed at Gaberones, Palla and Macloutsie who were to send in daily reports to Mafeking of their stocks of forage and supplies and which detachments had arrived and left.

By the 25 April there were 700 men of the MRF marching on the road and Plumer left Mafeking by coach intending to arrive at Macloutsie as the first of the detachments arrived.

On the road

Route and daily routine

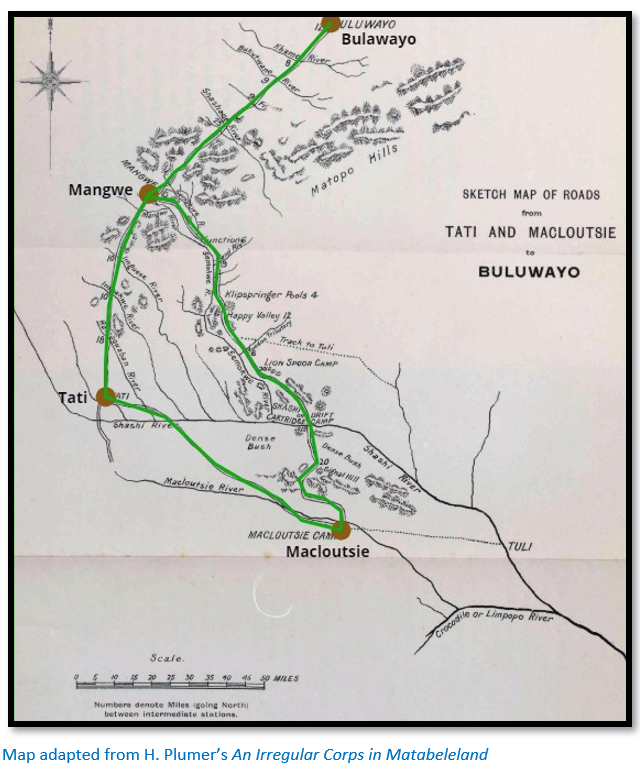

There were two options for the route from Mafeking to Bulawayo. Either the coach road via Palla, Palapye and Tati (418 miles) or via Palla, Seleka and Macloutsie (561 miles) The first was shorter and there were grain supplies at Palapye, but there were also long stretches of heavy sand where there was little water. The longer route had a harder road and better water supplies and was recommended by local transport drivers, so this route was chosen and rough sketch maps drawn up and given to each officer-in-charge.

The roads were inches deep in sand; the hooves of the horses kept each detachment enveloped in dust so that it was impossible to distinguish the trooper in front.

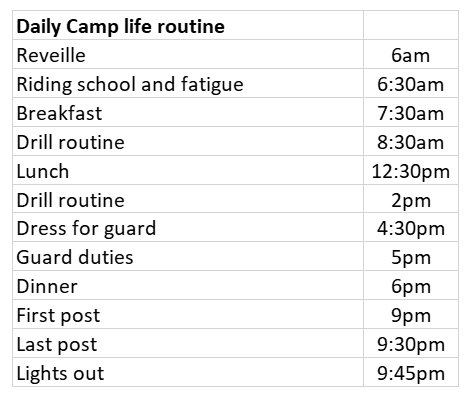

Daily treks varied between 24 – 48 kilometres (15 – 30 miles) depending on how easy the road was and the availability of water. Reveille was at 4am or earlier, depending on the length of the day’s march; about 9am there was a stop for breakfast and a sleep in the middle of the day. At 4pm they would saddle-up and march for another five hours when the second meal of the day was prepared; after which the troops settled down to sleep.

Macloutsie

Plumer left Mafeking by coach on the 26 April and reached Macloutsie about noon on 3 May; they found No 1 and 2 detachments had arrived; they were 110 men, 115 horses, 5 wagons and 64 mules. That same evening a convoy arrived from Pietersburg of 14 ox-wagons with mealies and oats – the drivers had used a little frequented road and seen no signs of the rinderpest.

Macloutsie, the headquarters of the Bechuanaland Border Police (BBP) consisted of a post office, barracks, huts, stores and a fort with a decoy Maxim gun on the roof of the magazine made from iron-pipes. Soap, candles and matches were affordable, but whisky at 25s. and lime juice at 10s. a bottle were unaffordable.

Rinderpest and looting

Sykes comments on the decaying stench of rotting oxen and says it was common to see an entire span lying about within a radius of 100 metres. Wagons were abandoned laden with timber, furniture and supplies just off the road. Sykes say Dutch transport-riders did the bulk of looting but admits that MRF troops did plunder whatever they could find abandoned, including cases of provisions and liquor which were usually immediately consumed. Sometimes they plundered with the knowledge of their officer and non-commissioned officers, sometimes not. He states one officer only became aware when he found half his men drunk and incapable.

Merchants in Bulawayo became indignant and the BSA Company paid them compensation, but some harm was caused to the MRF’s reputation.[xxv]

Routine changes once the troops are into Matabeleland

Once the troops left Macloutsie, the small detachments of 50 men were concentrated into squadrons of 150 men each commanded by a regular officer and travel was only done in daylight hours. Advanced and flank guards were put out, one troop always closely guarded the wagons and a laager was formed with the wagons each night.

All spare kit was left at Macloutsie, only blankets and groundsheets being allowed on the wagons and the men only took what they could carry in their wallets and haversacks. Any men who seemed weak or ill were left at Macloutsie pending a medical examination to assess whether they were fit for further service.

Formation of the Matabeleland Relief Force

March from Macloutsie to Mangwe

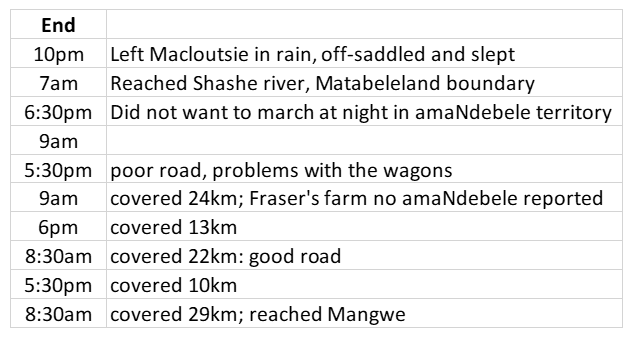

Plumer marched with A Squadron from Macloutsie and this itinerary illustrates the usual routine.

Plumer says the civilians at Mangwe fort comprised mostly prospectors and Afrikaanse farmers with their families and belongings; any value the fort had as a defence work was nullified by the collection of huts, wagons and paraphernalia gathered outside. Hans Lee and Cornelius van Rooyen were in charge at Mangwe and wanted Plumer’s men to intercept an amaNdebele impi moving southwest but Plumer’s first priority was to safeguard Bulawayo.

There was an excellent farrier at Mangwe named Roberts who shoed the horses of each squadron as they passed through and here Plumer met Alfred James ‘Bulala’ Taylor [described in more detail in the article on the battle of Ntaba zika Mambo] and who is described by Plumer as ‘a most efficient leader of scouts in all our subsequent operations.’ The store at the Bulawayo end of the Mangwe Pass had been burnt down and here they met Sir Richard Martin in the Zeederberg coach who asked Plumer to accompany him to Bulawayo.

The forts along the road were inspected; Fort Matoli (24 km from Mangwe) Fort Halsted (34 km from Mangwe) Fort Figtree (48 km from Mangwe) then forts Mabukwatwani, Khami and Matabele Wilson’s, each with garrisons of twenty to thirty men, but few horses.

Arrival in Bulawayo

The squadrons rode into Bulawayo, then a town of wide streets and mostly single-storey corrugated iron houses, on 24 May 1896. The townspeople gave them a great welcome, but although many old acquaintances were re-made, the celebrations did not last long as the amaNdebele forces were still very much in the vicinity of Bulawayo. They would appear on the ridges just 5 kilometres from town until the seven-pounder fired shrapnel shells when according to Sykes they would: “suddenly bear in mind the urgency of an appointment a few miles further from Bulawayo.”[xxvi]

Multiplicity of those-in-charge

Powell rightly points to the potential for conflict between personalities.

Earl Grey, a director of the BSAC had only just been appointed Administrator in place of Jameson who was languishing in a Pretoria gaol. In fact he had stopped off at Plumer’s camp outside Mafeking before continuing to Bulawayo by coach.

Colonel Sir Richard Martin had been hurriedly appointed by the Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain as Deputy High Commissioner and Commandant-General of Rhodesia who was to command the police and armed forces of the BSAC and took over control of operations from Grey. He caught up in his coach with Plumer at Mangwe Pass and together they entered Bulawayo on 14 May.

Major-General Sir Frederick Carrington, a veteran of the Eastern Cape Frontier Wars, now fifty-two years old and somewhat fatigued, was to run military operations as commander of all armed forces in the Bechuanaland Protectorate, Matabeleland and Mashonaland comprising the Bechuanaland Border Police (BBP) the remnants of the BSAC Police not captured with Jameson and volunteers merged into the Bulawayo Field Force (BFF) the MRF and two units of ‘Cape Boys’ under Robertson and Colenbrander plus the Imperial Mounted troops still to arrive under Lieut.-Col Alderson. Carrington arrived on 2 June from his sinecure post as military commander at Gibraltar.

Lieut-Colonel Robert Baden-Powell, an old colleague of Plumer’s from India, was Carrington’s Chief of Staff.

Finally Cecil Rhodes arrived on 27 May with a relief force from Salisbury. He had resigned during his second term as Prime Minister of the Cape on 12 January 1896 following the Jameson raid, but was still a director of the BSAC, a post he relinquished in June 1896.

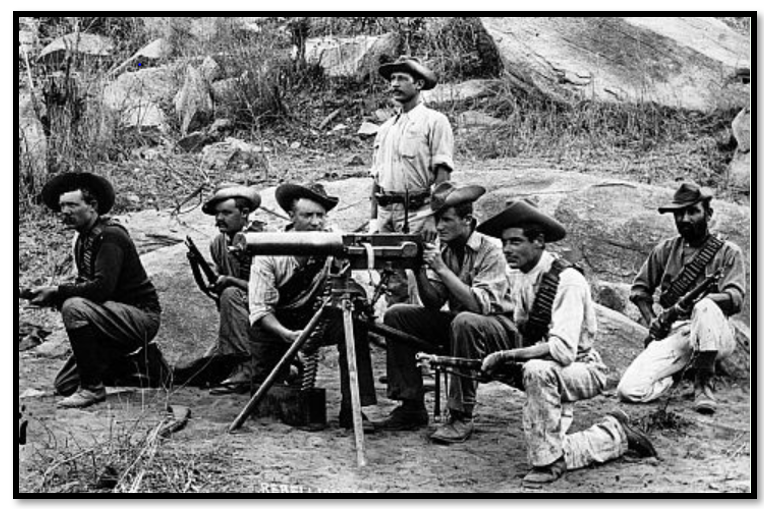

Photo courtesy of I.J. Cross[xxvii]

A column under Colonel Napier had moved towards Gwelo to attack and disperse any forces in the area and practically denuded the town of fighting men and horses, but amaNdebele impis were said to be gathering on the Umguza and Khami rivers; a number of horses had been driven away by them from the fort at Matabele Wilson’s towards the Khami river.

On 18 May B Squadron arrived at Khami and the next day A Squadron rode to Hope Fountain Mission 20 km from Bulawayo and a fortified post was built overlooking the valley and mission station. The homes of Reverends Carnegie and Helm had been burnt down and the entire area was deserted.

Fifty men of the Bulawayo Field Force arrived on 22 May to garrison Hope Fountain and A Squadron scoured the areas with patrols but only saw recently deserted kraals. Early the next day A Squadron left for Khami and at noon the small garrison at Hope Fountain were attacked by around 200 amaNdebele who were beaten off with the loss of a horse and mule.

Major Kershaw arrived at Bulawayo with C Squadron on 22 May.

The MRF’s first test to the Khami river

Jan Colenbrander confirmed the amaNdebele were concentrating at Trenance farm about 16 kms north west of Bulawayo. Two roads led to the farm; one from Bulawayo and the other from Government House. Plumer took a column on the first and Major Watts led Squadron B on the second with the plan of joining forces at their junction.

At midnight on the 24 May, the MRF were ordered on a three-day expedition. Sykes captured the excitement well: “Kits were overhauled, haversacks were stocked and impedimenta generally reduced as much as possible, for no wagons were to proceed with the expedition. By nightfall everyone was in a state of suppressed excitement. The weather was magnificent, but the biting cold soon made itself felt, while the full May moon shed an eerie light over the bustling men and patient horses. Orderlies hastened to and fro. Civilians, attached by special permission, kept riding up and down the line seeking some particular squadron. Press correspondents were pestering everyone for information and getting roundly sworn at in consequence and generally everyone appeared to be endeavouring to do half a dozen things at once. Presently came the order to saddle up, then the order to mount; strict silence was enjoined and quietly the long line of men and horses filed out of camp.”[xxviii]

At 6:30am the forces met; but the 1,000 – 1,500 amaNdebele had learnt not to face the Maxim guns and disappeared as they were charged by No 1 Troop of A Squadron and Gifford’s Horse; the native allies fired recklessly and were so dangerous to the MRF that Plumer recommended they be disbanded. The force lost two dead and six wounded, but Plumer was pleased that their military discipline had held.

In the afternoon about 4:30pm a second fleeting engagement took place as the MRF crossed the Mpopoma stream but were driven back and broke off the engagement.

On 27 May Captain Beresford arrived with D Squadron very disappointed they had missed the engagements.

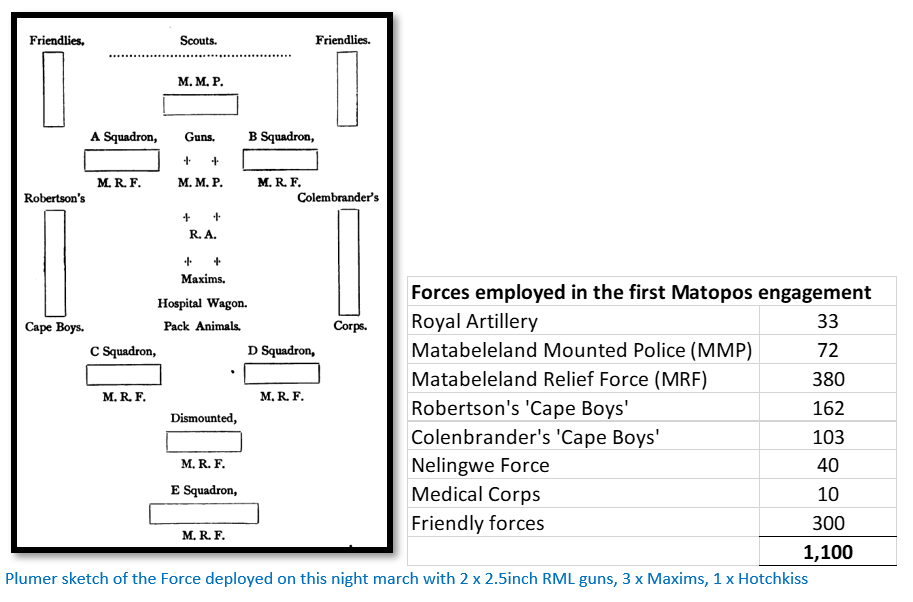

On 2 June Major-General Sir F. Carrington arrived to take command of the troops with Lt-Colonel R.S. Baden-Powell as Chief Staff Officer, Captain C.B. Vyvyan and Lieutenant V. Ferguson. E Squadron arrived the same day with only the dismounted detachment and the ‘Cape Boys’ under Robertson still to arrive.

Second test - Gwaai river patrol

Carrington soon informed Plumer that he wished to clear the areas north and west of Bulawayo.

- Plumer was to take one column down the Gwaai river to its junction with the Umguza river

- Captain McFarlane was to work down the Umguza river

- Colonel Spreckley was to take a column to the Inyathi and Shiloh Missions.

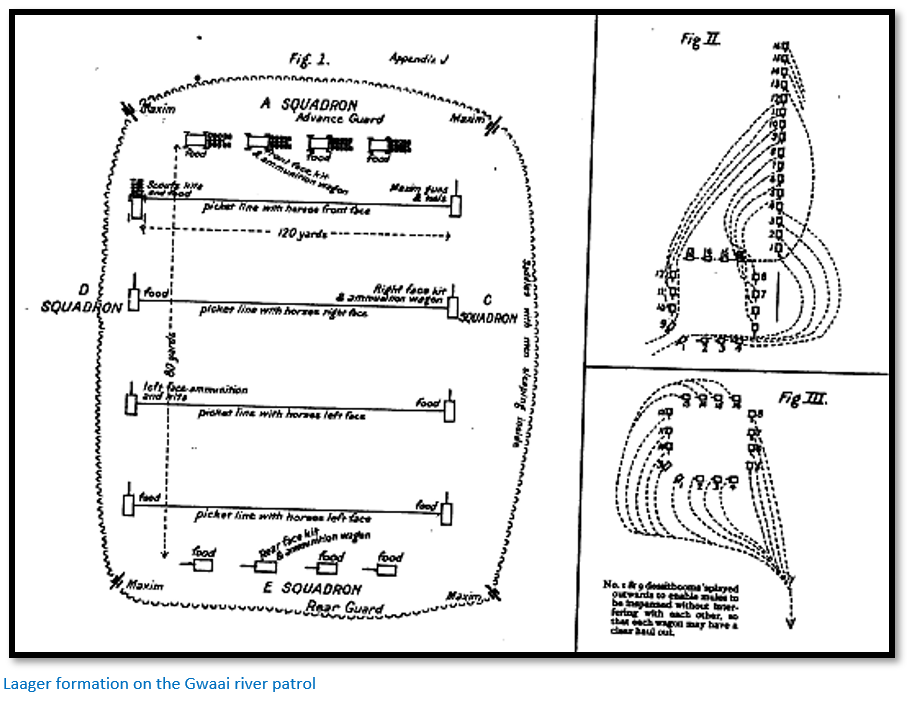

Their second foray after the amaNdebele was much the same as the first only on a larger scale and was planned to last twenty days. Plumer’s column comprised 32 officers, 451 NCO’s and men, 474 horses, four Maxims, sixteen wagons with supplies drawn by 192 mules. Another two columns operated parallel to and north of Plumer’s column.

The wagons had twenty day’s rations, two blankets, a ground-sheet, 150 rounds of spare ammunition per man, in addition to the 50 rounds they each carried in bandoliers.

The mules needed to graze for 3 – 4 hours in daylight which with upsets crossing rivers and vleis limited the ground they could cover; ticks were a problem and one in four mules died.

The men suffered from veldt-sores caused by the continuous diet of bully beef and dysentery which caused dehydration and if not treated quickly could be fatal. In addition the men’s boots and clothing were becoming worn out.

The diagram above of the laager formation demonstrates once again Plumer’s meticulous attention to detail in everything he undertook.

MRF Military tactics were ineffective

AmaNdebele tracks were often seen by the scouts, but mounted men were unable to follow warrior’s on foot into the impenetrable bush. Few actual encounters took place and the column was reduced to burning down empty kraals and destroying what food they could not take. Sykes comments that it was small wonder the amaNdebele were never surprised: “from reveille to lights-out at 8:45pm the bugles were sounding the calls all through the day, whilst hardly a night passed but rockets and star shells lit up the sky for miles around and disclosed the column’s position and rockets and star-shells burst into the night-sky. There was no mystery about the approach of the Column.” Sykes also thought too much time was devoted by the officers in ensuring saddles were neatly aligned in rows.[xxix]

He lampoons the early military tactics: “One can picture the wily rebel listening from afar to the white man’s ‘pow-wow’ and whilst stirring his mess of ‘impupu’ [sadza] speculating as to how long it might be before a flank movement to the rear would be necessary on his part to frustrate the candid intentions of the invader.”

Sykes states that he witnessed prisoners being mistreated; on one occasion a rope was tied around a prisoners neck and his guard rode at a canter; when he fell through exhaustion, he was dragged along the ground. Sykes thought Plumer would have severely punished individuals for such behaviour. He also states that captured prisoners were shot; either out-of-hand or later.[xxx]

Clearly the columns were being closely watched and the amaNdebele always had plenty of notice of their approach - little was achieved by the Gwaai river expedition of 180 men led by Major Watts, other than kraals being burnt and some grain being confiscated. This was known as ‘the whispering patrol’ on account of the men being ordered not to talk and all orders being given in whispers. The scouts reported kraals recently vacated and with the amaNdebele thought to be just ahead no smoking was permitted, nor fires lighted. But Watts suddenly and without thinking gave an order for the trumpeter to sound a call and in response warning shots were fired from the surrounding bush. The column was operating in a ponderous fashion against an enemy that was operating in small groups and highly mobile and always aware of the column’s location.

The obvious lack of success led to one in six of the men applying for their discharge upon their return to Bulawayo; however Plumer addressed the men on parade and pointed out they had signed on for as long as their services were required and there was a military mission still to be carried out.

The second column which had set out with Plumer suffered from the poor condition of their mules which handicapped their mobility. The third column under Colonel ‘Jack’ Spreckley, who had taken his discharge from the Bechuanaland Border Police along with Johnson, Heany, Borrow and Burnett in 1886 had carried out better reconnaissance and came to grips with an Amandebele impi on the Umguza river on 6 June and inflicted casualties of about 300; the highest number inflicted in any single engagement.

Outbreak of the Mashona rebellion or First Chimurenga

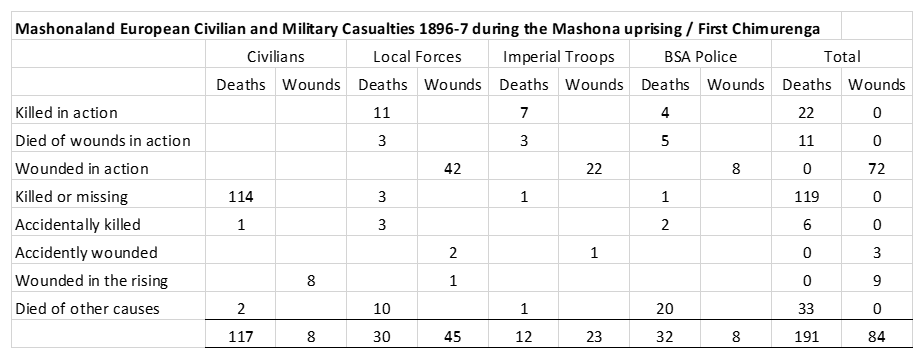

On his return to Bulawayo Plumer learned that the Mashona had seized the opportunity opened up by the absence of so many police and military volunteers to rise in a similar manner as the amaNdebele had in late March and kill over 140 outlying miners, prospectors, traders and farmers.

The Mounted Infantry and sappers were called upon to assist and Lieut-Col Alderson was soon to disembark at Beira. The 7th Hussars under Col Paget and detachments of Mounted Infantry under Captain Kekewich and Major Rivett-Carnac were sent from Mafeking to Tuli and Victoria.

Battle of Ntaba zika Mambo

The impi attacked by Spreckley’s column moved into the jumble of granite kopjes and well-watered ravines thirty kilometres north east of Inyathi Mission. On 29 June 1896 a large force moved off to engage the amaNdebele at this location. This time the operation was much better organised with a detailed reconnaissance in advance by Jan Grootboom, a successful night march that caught the amaNdebele by surprise and the fighting was carried out with much courage and pluck particularly by the “Cape Boys” under Major Robertson.

This battle is covered in detail in the article Battle of Ntaba zika Mambo, Manyanga or Mambo Hills under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

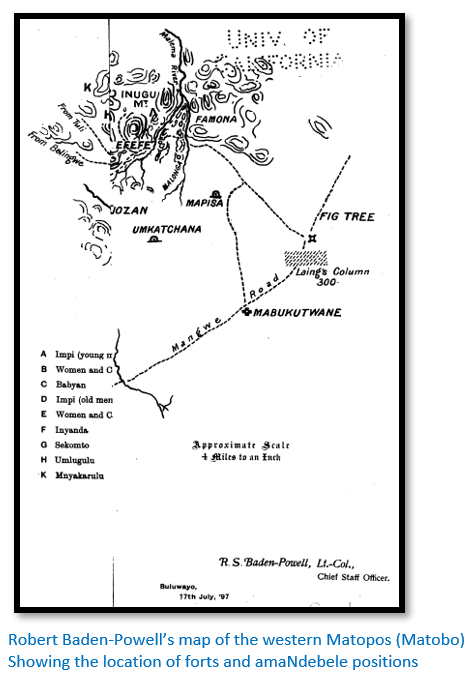

The amaNdebele move into the Matobo

The majority of amaNdebele still willing to fight took refuge in the Matobo – a much bigger proposition than Ntaba zika Mambo; approximately one hundred kilometres from east to west and thirty-five kilometres deep, the ridges of rocky kopjes composed of enormous piled boulders rose much higher than Ntaba zika Mambo, access was difficult through narrow defiles into fertile and well-watered valleys. The kopjes contained hundreds of natural caves that were ideal for concealing grain-bins and easily defended with loose stone dry-walling.

The MRF base camp was at Ushers Farm ten kilometres north of the Matobo and away from the fleshpots of Bulawayo. Now Plumer combined his routine careful planning and painstaking preparation with Robert Baden-Powell’s close observation and scouting under the tutelage of Jan Grootboom. The new strategy was to gather as much intelligence on the amaNdebele dispositions as possible prior to any military engagement.

Plumer writes: “on the 16 July all available officers went out to make a reconnaissance of part of the Matoppo Hills, not so much with a view of discovering the exact whereabouts of the rebel impis, as to give us all an opportunity of examining the koppies and ascertaining te character of the country we should have to operate in. We were all much impressed with what we saw and the difficulties of the task before us if the rebels were handled with sufficient skill to avail themselves of all the advantages which their occupation of such a territory could give them. We climbed up one of the highest koppies we came upon and though no very extensive view was possible there lay before us an apparently endless view of koppies of various sizes, all more or less composed of huge granite boulders, in the interstices of which grew bush and scrub and separated from each other in most cases by only extremely narrow and torturous gorges.”[xxxi]

Engagements in the Matobo

On 19 July a column left Usher’s No 2 at night marching 8 kms over the veldt until 2am and then rested until 4:30am before resuming the march to the head of a valley where the field hospital halted with a guard of fifty men, the pack animals and mounted men plus a Maxim gun. The remainder of the force continued down the valley which was dominated by steep-sided kopjes – small groups of amaNdebele in them were dispersed by firing shells.

The stronghold at the end of the valley was made up of a labyrinth of caves strengthened with dry-stone walling. The friendlies attacked first but soon fell back after resistance was encountered. They were followed by the ‘Cape Boys’ under Robertson and Colenbrander, who had proved themselves resolute at Ntaba zika Mambo supported by two Maxims and a Hotchkiss under the overall command of Baden-Powell. The amaNdebele fought obstinately killing two of their attackers and wounding six before falling back into the jumble of caves and kopjes behind their position.

The scouts and mounted troop of the Matabeleland Mounted Police tried to work their way around the kopje to cut off the retreating amaNdebele but were forced through a narrow defile through which they could only pass in single file and came under heavy fire. Here Sgt Warringham MMP[xxxii] was killed and Lieut Taylor of the Scouts slightly wounded

The amaNdebele had quickly adjusted their military tactics. A Matabele survivor of the Battle of Bembesi, called Egodade by the amaNdebele recalled that when the "sigwagwa" as they called the Maxims, opened fire "they killed such a lot of us that we were taken by surprise, the wounded and the dead lay in heaps." They knew it was hopeless to take on the MRF in a straight battle and had also learnt since 1893 that raising the height of the back-sight of a rifle did not increase the impact of the bullet; many native police who had been trained on the Martini-Henry had deserted to the amaNdebele cause and the rank and file warriors were now much more proficient in using their rifles.

The pattern of fighting was repeated again and again – long marches followed by short engagements and a steady loss of soldiers. The amaNdebele would hold their positions and then retreat into the fastness of the Matobo – their local knowledge of the terrain and speed of movement allowing them to slip away.

The MRF based in fixed positions situated around the Matobo [see the articles on Fort Usher No 3 and Fort Umlugulu and the cemetery under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

The Battle of Tshingengoma or Sikombo’s stronghold in the article under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com on 5 August 1896 also featured a night march followed by the usual pattern of the amaNdebele defending their rocky strongholds and almost over-running Lieutenant Beresford and the seven-pounder guns before slipping away into the fastness of the Matobo. Grievous losses were suffered though by Plumer’s force: Seven European were dead or dying including Major Kershaw and Lieutenant Hervey and thirteen wounded, a high proportion of which were MRF officers and NCO’s.

Futility of further fighting

The military situation was that of a stalemate; the amaNdebele would only be forced to surrender if the manpower of the MRF was considerably expanded and additional forts constructed around the Matobo. The amaNdebele clearly were avoiding general military engagements against the MRF and meant to trust to the difficult conditions within the Matobo and their mobility and knowledge of the kopjes to save them from losses and to exhaust the Imperial Forces.

The BSAC was funding the fighting and Rhodes saw that the chartered company faced financial ruin. On the amaNdebele side food was scarce within the Matobo and they faced the prospect of widespread famine if the crops were not planted before the coming rainy season and they were also weary of the fighting.

First Umvukela / Rhodes indaba

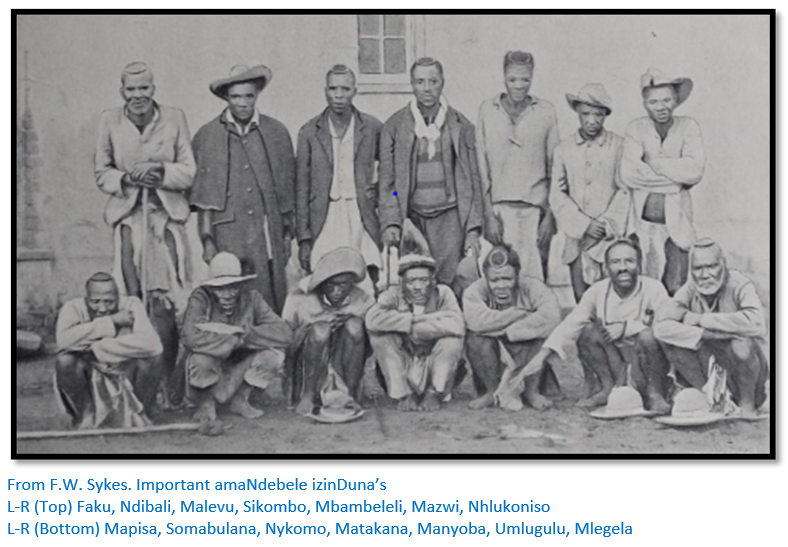

Rhodes saw that a direct approach to the izinDuna’s needed to be made as only they could persuade the younger warriors to lay down their arms. Plumer and Carrington knowing that there was no military solution with their existing forces gave reluctant approval for Rhodes to negotiate with the izinDuna’s; Sir Richard Martin was all but ignored. See the article The Matabele uprising or First Umvukela Indaba site (Rhodes Indaba site) under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

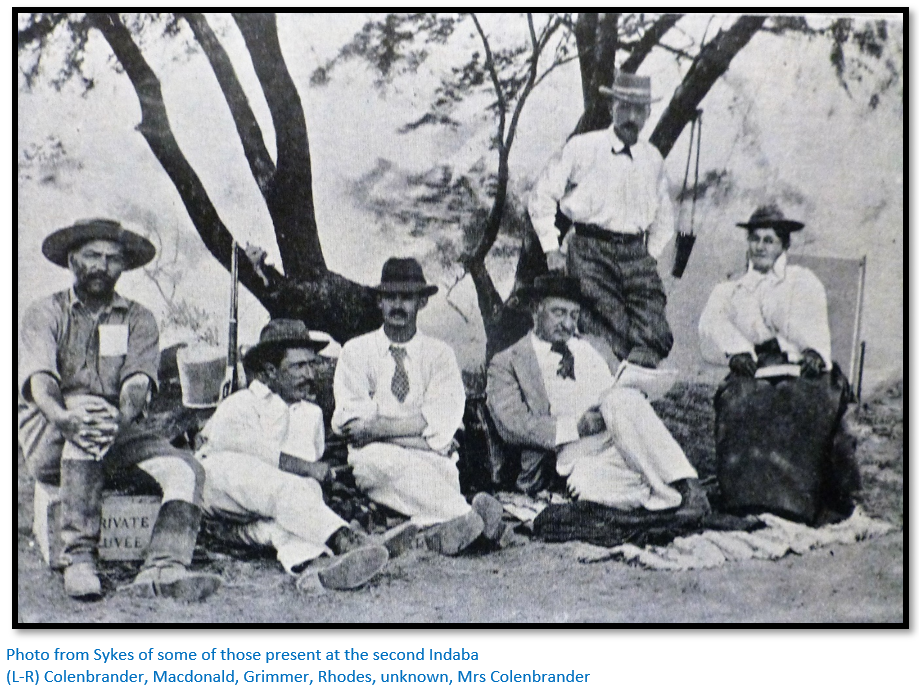

The four hours of talks between Rhodes and the izinDuna’s on the 21 August were the first of the Indaba’s to settle the terms of the peace. Rhodes’ sent this note to Plumer soon after: “My Dear Plumer, We had a regular go with the natives today; the indaba lasted four hours, they will not fight again unless forced to do so. I am sorry Moncrieff (one of Plumer’s staff officers) was not present, but Colenbrander had a message they only wanted myself and himself. We went through every grievance. There were forty present and all the principal Chiefs. C.J. Rhodes”[xxxiii]

A second Indaba followed a week later at which Plumer and two of his officers were present; there was a third Indaba on 9 September at which Martin and Grey were also both present and following which the amaNdebele warriors began to leave the Matobo and surrender their arms. The fourth and final Indaba was at Rhodes’ camp on 14 October when Grey and Rhodes convinced the izinDuna that if they gave up their arms and returned to their kraals there would be no retribution.

Plumer says he found the waiting welcome at first after their exertions, but the inaction became irksome and tedious after a while. Lieutenant-Colonel Baden-Powell took a patrol composed of detachments from the 7th Hussars and York and Lancaster and West Riding Regiments to Inyathi, then Ntaba zika Mambo and then onto the Shangani river and after the capture and execution of Chief Uwini worked through the Somabhula Forest. [for more details see the article under Bulawayo on Baden-Powell in Matabeleland in 1896 where he learned the principles of Scouting on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] The patrol went onto overrun Chief Wedza’s stronghold before returning to Gwelo.

Disbandment of the MRF

With the cessation of fighting and the imminent start of the rainy season most members of the MRF were enthusiastic about the news that they would be disbanded in mid-October. Some who wished to stay took their discharge in Bulawayo; the others, including ten officers and 289 men marched back to Mafeking to receive their discharge including the “Cape Boys” who had shown admirable courage.

Plumer received congratulations from many. Earl Grey, who remained as Administrator until 1898 wrote: “…The rapidity with which your column was recruited, horsed, equipped and marched up to the relief of Bulawayo was, in itself, an achievement of which you and every member of your force have abundant reason to be proud…I wish on behalf of the Administration and the English settlers of Matabeleland to acknowledge with grateful thanks the part played by all your officers, non-commissioned officers and men who have so gallantly and ably assisted you…”[xxxiv]

Sixty-five of his officers wrote: “…It has been a great pleasure to us to have had the honour to be with you in the field and in saying ‘Good-bye!’ we all unite in wishing you a brilliant future in the Service and throughout your life…”

Father Barthelemy who was Chaplain of the MRF wrote the tribute that touched Plumer the most: “It is almost useless to tell you that I heartily join in all the congratulations you receive and will receive. Men more authorised to do so than I am praise your work; still nobody perhaps knows better than I how much you deserve the love your men have for you…”

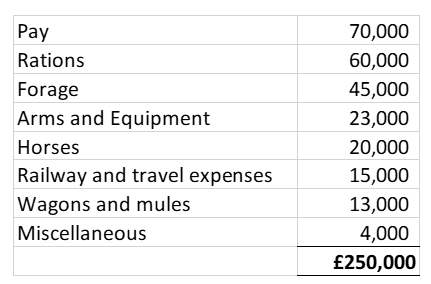

Cost of the MRF to the British South Africa Company

Plumer’s estimate is made up as follows:

Plumer adds that the pay to men and officers was extremely liberal and throughout the campaign the BSAC treated them with the greatest consideration and generosity.

Conclusions to be drawn from Plumer’s experience in Matabeleland

- For a regular officer in the British Army Plumer adapted amazingly quickly to the exigencies of the situation and quickly concluded men and officers would be better trained in smaller troops and so were despatched from Mafeking in detachments of fifty each under an officer allowing both men, non-commissioned officers and the officers to get to know each other better and become familiar with the various tasks required on a long route march.

- Plumer proved extremely adaptable in dealing with numerous persons-in-charge in Matabeleland: Earl Grey, Martin, Carrington, Baden-Powell, Rhodes and in commanding irregular troops who were all independently minded and by temperament individualistic[xxxvi]

- Plumer’s skills in careful planning and paying attention to every detail involved in campaigning in the field become obvious in the way the MRF is managed; these skills become obvious to everyone who meets Plumer throughout his military career.

- His tact and diplomacy in dealing with the day-to-day problems encountered in the MRF were really appreciated by those under him; it eased tensions and created good relations. It is not for nothing that Geoffrey Powell called his book: Plumer; The Soldier’s General.

General Carrington in his report Operations in Rhodesia, 1897 to the War Office praised Plumer for raising and commanding the MRF “with conspicuous success” and to “having rendered excellent service generally” but Plumer received no decoration.

Earl Grey protested to Sir Alfred Milner, High Commissioner for Southern Africa in 1897: “The fact that Colonel Plumer was able to raise, horse and equip at Mafeking a force of 700 men and fight two successful battles against the Matabele, after marching 600 miles within forty-one days of receipt of the first order given to raise the force, is, if not unique, at any rate a remarkable achievement. And not less remarkable than this achievement was the admirable discipline and bearing of the force thus hurriedly collected throughout the whole of their service in Matabeleland.”

But Plumer received no award apart from his brevet to Lieut-Colonel; although Carrington whose chief accomplishment appears to have been to learn a ride a bicycle around the streets of Bulawayo, added a KCB to his KCMG.

Post Matabeleland

Plumer became deputy assistant adjutant-general at Aldershot with promotion to Lieut-Colonel on 8 May 1897 and spent his leave writing his book An Irregular Corps in Matabeleland.

Back in Africa for the second Boer War

In 1899 Plumer returned to Southern Rhodesia as a special service officer to raise irregular units of mounted infantry. Rob Burrett in his book Plumer’s Men tells the story of how the Boer forces which might have fought elsewhere were kept occupied on the Rhodesian and Bechuanaland borders with the Transvaal Republic and Plumer’s part in the Relief of Mafeking during the Second Boer War. I would recommend this book to readers interested in the fortifications and battles that took place along the border areas involving the Rhodesia Regiment and the Rhodesia Field Force which included Australians and New Zealanders and elements of the Imperial Yeomanry.

The Times History described Plumer’s part in the relief of Mafeking: “certainly the most interesting and instructive of the minor operations carried on during the first year of the war. With a force always at a numerical disadvantage to his opponents, containing no regular troops and very few regular officers, working all the time on the borders of the enemy’s country, with miserably inefficient artillery and constant anxiety for supplies, he succeeded by daring, which never exceeded the limits of due precaution, in stopping most effectually any attempt against Rhodesia and in dissipating the energies of the forces arrayed against Mafeking.”[xxxvii]

Plumer was promoted to Colonel on 29 November 1900 and given command of a mixed force which pursued General Christiaan de Wet’s forces…in forty-three days they had travelled thirteen hundred kilometres and prevented de Wet from invading the Cape Colony. Plumer was always a day or two behind de Wet who managed to evade capture but lost many of his men and all his transport and guns during February 1901.

Plumer’s dogged pursuit only enhanced his reputation and he was promoted to Brevet Brigadier-General. He served another year in South Africa advancing over three hundred kilometres from Pretoria through thick bush and taking Pietersburg, the last established Boer base with little resistance. The Boers continued their guerrilla war and Plumer with his mostly Australian and New Zealand mounted infantry was hardly ever out of the saddle during the next year capturing a few prisoners and losing a trooper from time to time to a sniper, or in an ambush.

The war of attrition told on the Boers and in March 1902 Plumer’s column was broken up; his troops given their discharge and Plumer given leave by Lord Kitchener, Commander-in-Chief in South Africa, after three years of active campaigning. In a despatch Lord Kitchener wrote that Plumer: “invariably displayed military qualification of a very high order. Few officers have rendered better service.”

Enthusiastic crowds greeted him on his return to England; Earl Grey wrote: “We are all drunk with excitement and Fizz at your success and I do congratulate you from the bottom of my heart at the magnificent way you played the game.” Grey was present at the London office of the BSAC when Plumer was presented with a sword of honour, subscribed by the Rhodesian people with its hilt, blade and scabbard of Rhodesian gold.

Lord Roberts wrote in February 1901 to Kitchener who later took over command of British troops in the Second Boer: “Plumer is a man we must, I think, look after. An ordinary commander would not have hung on as he did outside Mafeking and since the relief of that place he has done excellent service. Perhaps you would send me a telegram when you receive this to let me know what sort of berth Plumer is best suited…”

Plumer’s further military career

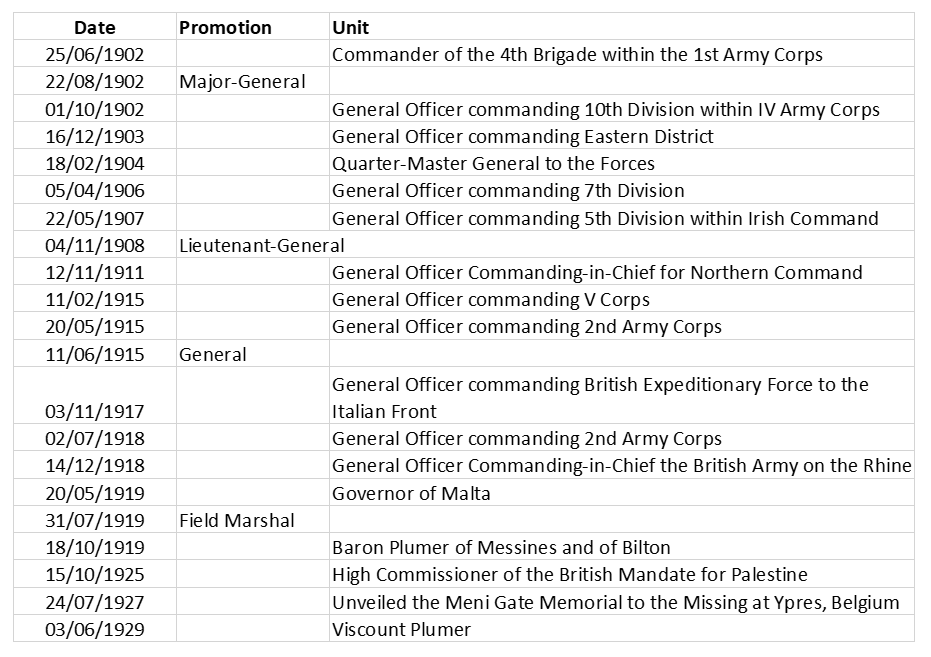

On his return he was made a Companion of the Bath on 13 May 1902 by King Edward VII and given the command of the 4th Brigade at Aldershot and on 1 November 1902 made up to major-general. In 1903 He received a letter from Lord Roberts asking him to command a district – either Colchester or Dover. He chose Colchester but had barely unpacked when Lord Roberts promoted him to the Army Council and they bought a forty-four year lease on 22 Ennismore Gardens which was to be his first and last permanent home.[xxxviii] A summary of Plumer’s progression through the ranks of the British Army is provided here.

It has been my intention in this article to concentrate on Herbert Plumer’s military experience in Matabeleland, but a diversion into why he was called “Plumer of Messines” may be interesting for the reader.

Battle of Messines

Some military historians have argued that the battle of Messines, a prelude to the much larger Third Battle of Ypres, was the most successful operation on the Western Front and was carried out by Herbert Plumer’s Second Army. The Messines Ridge was a shallow rise of higher ground southeast of the town of Ypres with strongpoints along its length slightly ahead of the German trenches which provided covering fire along the trench lines and made attacking them almost impossible. The Ridge itself, although only a hundred feet higher, provided commanding views over the battlefield and into the British lines.

The British attack on 7 June 1917 was initiated by the explosion of nineteen underground mines that caused a virtual earthquake among the many German strongpoints on the ridge and immediately killed as many as ten thousand German soldiers.

The evening before the attack General Harington[xxxix] said to the assembled war correspondents: “Gentlemen, I don’t know whether we are going to make history tomorrow, but at any rate we shall change geography.”

Preparation

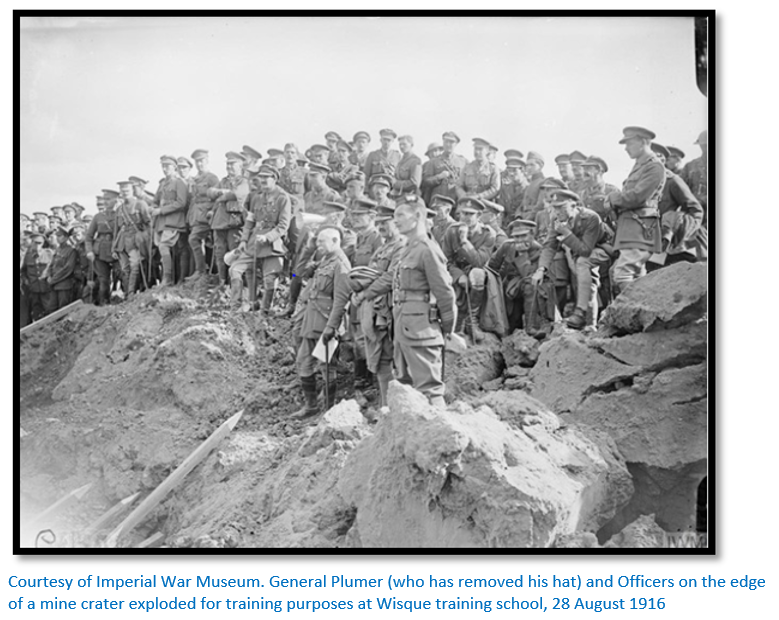

When Haig ordered Plumer to prepare for an offensive at Ypres he discovered that Plumer had been already laying the groundwork to wipe-out the German defences along the eight kilometres of the Messines Ridge in a single blow. Hill 60 marked the ridge’s highest point at 60 metres above sea level – it was not a natural feature but the spoil heap from when the railway cutting was dug – it had commanding views over the entire salient and was heavily fortified.

British mining had begun as early as 1915 with the first mine tunnels being 5-6 metres below the surface at the German strongpoint at Wytschaete [in the middle of the map below] Later Major Norton-Griffiths,[xl] a civil engineer and MP and passionate imperialist known as “Empire Jack” proposed to the Engineer-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force, Brigadier Fowke, that the galleries should be 18 – 27 (60 – 90 feet) underground. British, Canadian, New Zealand and Australian tunnelling companies completed the work assisted by the Royal Engineers using a technique developed in the London Underground for digging heavy clay called ‘clay-kicking.’ Empire Jack’s ‘moles’ sat facing the tunnel sides with their backs on tilted wooden boards with their feet kicking modified spades and chipped away the clay; a kicker’s mate disposed of the loosened debris in sandbags.

German tunnellers dug counter-mines and set off small explosive charges known as camouflets when they suspected they were close to allied tunnels which killed the tunnellers and wrecked completed galleries and chambers. The water saturated ground conditions frequently resulted in the tunnels being flooded. Excavated earth was removed at night in sandbags so that German reconnaissance did not spot the spoil heaps and give warning of the tunnelling efforts. Despite the German counter-mining efforts over 8,000 metres of tunnels and chambers were dug underground with up to 24,000 soldiers engaged in tunnelling.

Twenty-two tunnels were dug along the Messines Ridge, but one mine at Petit Douve Farm had been discovered on 24 August 1916 and destroyed and two mines close to Ploegsteert Wood were not exploded as they were outside the attack area.

Haig feared the discovery of even one of the mines could jeopardise the whole operation and pushed Plumer to attack; but Plumer refused to launch until all the elements of his plan were complete.

The attack

A heavy preliminary artillery bombardment began on 21 May 1917 using 2,300 guns and 300 heavy mortars and the shelling only ceased at 2:50am on the morning of 7 June. The German troops, sensing an attack was about to happen rushed from their deep dugouts to their defensive positions in the strongholds and manned the machine-guns: at the same time sending up flares to illuminate any movement toward their positions.

There was silence for 20 minutes until 3:10am when all nineteen mines with over 424 tonnes of explosive were detonated within 20 seconds of each other. The sounds of the explosion were audible in London and Dublin and were said to be the loudest man-made explosion ever. The sky lighting up above the ridge was likened to a pillar of fire.

The explosives used were mostly ammonal, a potent mixture of ammonium nitrate, aluminium powder, Trinitrotoluene and charcoal.

Soon after nine divisions of infantry from three Corps; X, XI and II Anzac of the Second Army advanced cautiously under the protection of a creeping artillery barrage which advanced ahead of their attack supplemented by tanks and electrically triggered versions of the Livens projectors which propelled gas cylinders filled with flammable oil 1,200 metres directly into the German trench lines and with reconnaissance from overhead aircraft.

In the areas of the mine explosions the approximately 80,000 Allied troops who advanced up the slopes found the German defenders dead, wounded and stunned; about 10,000 German troops were killed when the mines detonated. On the top of Hill 60 were two craters; one 80 metres across and fifteen metres deep and the other 63 metres across and 10 metres deep surrounded by a rim of debris and smashed concrete. The attackers swept through the gaps in the German defences advancing 2,800 metres and all the initial objectives of the battle were taken within 3 hours.

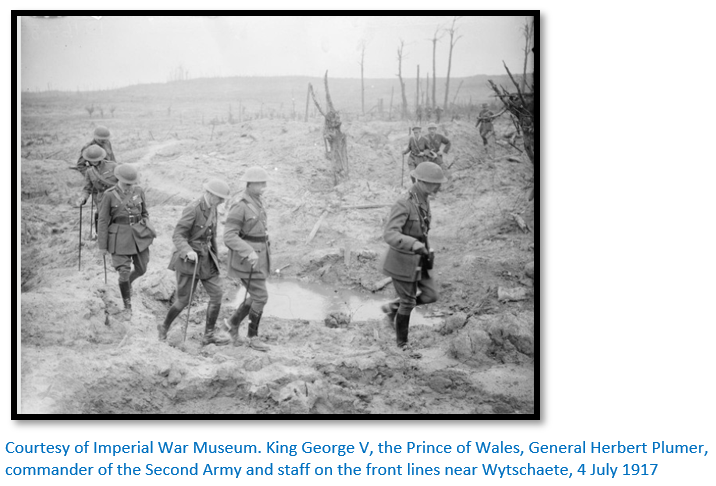

Messines was Plumer’s finest hour, but he went on to further victories at Menin Road Ridge, Polygon Wood and Broodseinde and continued to command the Second Army during the German Spring Offensive and the Allied Hundred Days Offensive.

Lloyd George was triumphant even with the benefit of years of reflection. In his 1934 war memoirs, he wrote: “The capture of the Messines Ridge, a perfect attack in its way, was just a useful little preliminary to the real campaign, an aperitif provided by General Plumer to stimulate the public appetite for the great carousal of victory which was being provided for us by GHQ.”

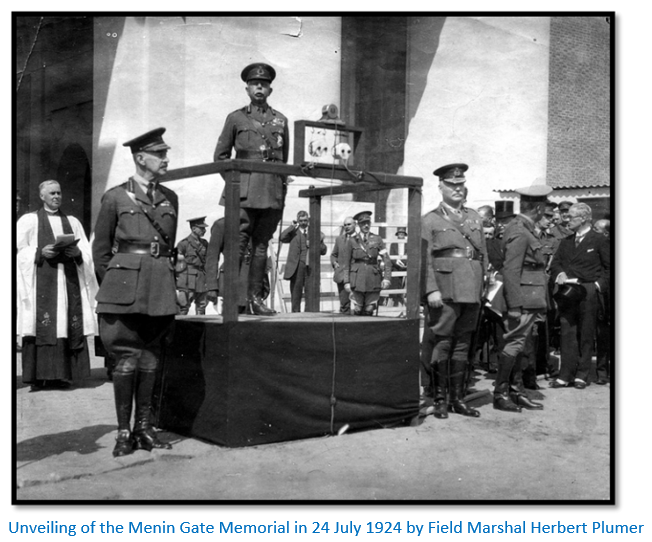

Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing

This memorial at Ypres, Belgium is dedicated to those British and Commonwealth soldiers who were killed in the Ypres salient in World War I whose graves are unknown. The names of 54,395 soldiers are listed who were killed up to 15 August 1917; the names of 34,984 missing after this date are listed on the separate Tyne Cot Memorial to the missing.

Harrington states: “Most of them had passed through that very gateway on their last march to the front…I am sure he was thinking, as we all were, of all those Brigade and Battalion Headquarters which he used to visit living in burrows under those ramparts; of the casualties incurred nightly by the endless stream of transport men, their horses and mules on their nightmare journeys through that Menin Gate; the star shells, crackling rifle fire, shell bursts, plunging horses and dogged infantrymen. No words of mine could ever depict that nightly scene of horror through the gateways of Ypres. Each gateway a bottleneck, registered to an inch by the enemy guns. Every man and animal had to run the gauntlet both going in and coming out.”[xli]

In his speech Plumer said: “…One of the most tragic features of the Great War was the number of casualties reported as ‘Missing, believed killed.’ To their relatives there must have been added to their grief a tinge of bitterness and a feeling that everything possible had not been done to recover their loved ones’ bodies and give them reverent burial…The hearts of the people throughout the Empire went out to them and it was resolved that here at Ypres, where so many of the ‘Missing’ are known to have fallen, there should be a erected a memorial worthy of them which should give expression to the nation’s gratitude for their sacrifice and its sympathy with those who mourned for them. A memorial has been erected which, in its simple grandeur, fulfils this object and now it can be said of each one in whose honour we are assembled here today: He is not missing; he is here.”[xlii]

Field Marshal Plumer as Colonel Blimp

Philip Gibbs, one of the five official World War I correspondents, described Plumer as “almost a caricature of an old-time British general, with his ruddy, pippin-cheeked face, with white hair, and a fierce little moustache, and blue, watery eyes, and a little pot-belly and short legs.” This article shows he was in fact, a combat-hardened veteran of Britain’s imperial wars whose well-earned reputation was based on precise planning and efficient staff work.

Plumer was popular amongst his men, mainly due to the fact that he led from the front, but he was also known to have a good sense of humour, despite being strict in his discipline. His favourite saying was: ‘Trust, Training and Thoroughness.’ Robin Neillands in his book The Great War Generals wrote:

“Plumer is one of the few commanders who came out of the Great War with an enhanced reputation.”

Plumer’s sporting life

In his younger days Plumer was a polo player and all his life was a keen cricketer. He played for his old regiment as an opening batsman and was a member of the Camberley Staff College XI of 1886-7 which only lost one match in two years.

On his return from Palestine he was made President of the M.C.C. Harrington says he was a wonderful speech-maker and had a delightful way of mixing up a note of real sincerity with a keen sense of humour.[xliii]

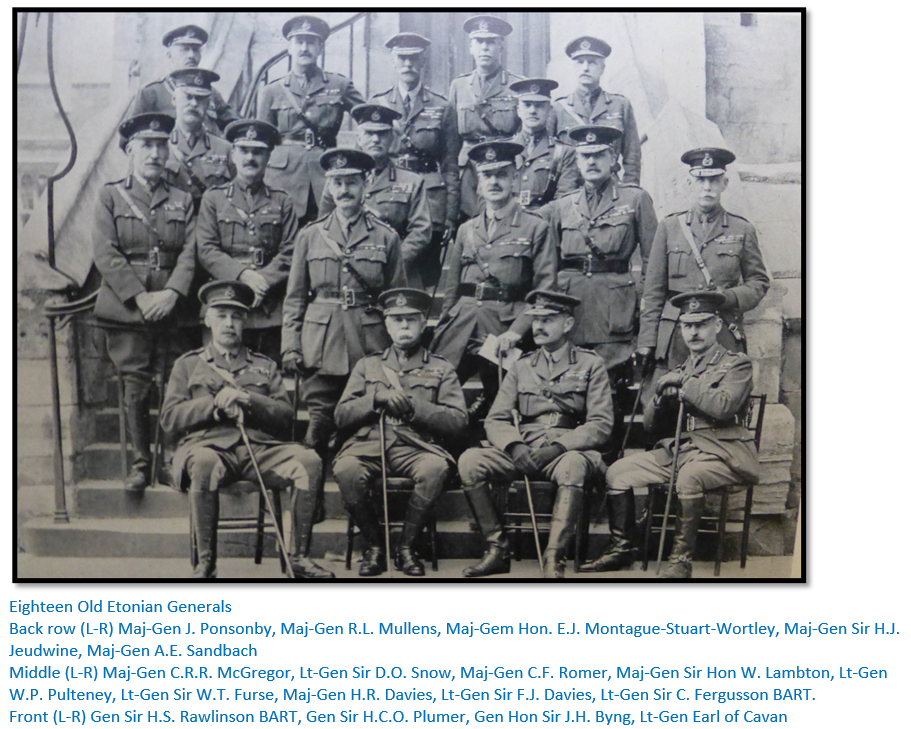

Old Etonian

At an Old Etonian Dinner at the Second Army Headquarters in December 1916 when 75 Old Etonians were present he said: “…It may be going a little too far to say that the history of Eton is the history of England; but it is indisputably true to say that at every period of the history of our country, notably at every stress and trial, Eton and Eton’s sons have taken a leading share in national service…”[xliv]

Toc H

Harrington says the nursing service under Florence Nightingale resulted from the Crimean War (1853 – 1856) the Boy Scouts and Girl Guides came out of Baden-Powell’s experiences in the Second Boer War (1899 – 1902) and Toc H came out of the Great War.[xlv]

Gilbert Talbot, the son of the Bishop of Winchester, a young officer in the Rifle Brigade was killed at Ypres in 1915. In his memory a house was started in Poperinge, 13 kms to the west of Ypres and during WWI one of only two towns in Belgium not under German occupation, called Talbot House, Toc H being the signallers way of expressing T at the time. The Rev. T.B. ‘Tubby’ Clayton organised the Talbot House where everyone was welcome and many soldiers facing danger and death daily found not only rest, but comfort and good cheer. Harrington says only those who served in the Second Army in defence of the Ypres Salient know what Toc H in Poperinge did and meant for them.[xlvi]

Tubby Clayton felt after the Great War that the spirit which he had seen and experienced should be extended to the younger generation and was very much supported in his efforts by Plumer. They wanted the younger generation to carry on the memory of those young men who cheerfully gave their all to save the next generation from having to go through what they went through. At each Toc H meeting they said: “At the going down of the sun and in the morning, we will remember them.”

Harrington says Plumer attracted people to him and gained their trust and affection because he was filled with the Toc H spirit. Word such as jealousy, bitterness and pettiness never entered his vocabulary.

Death

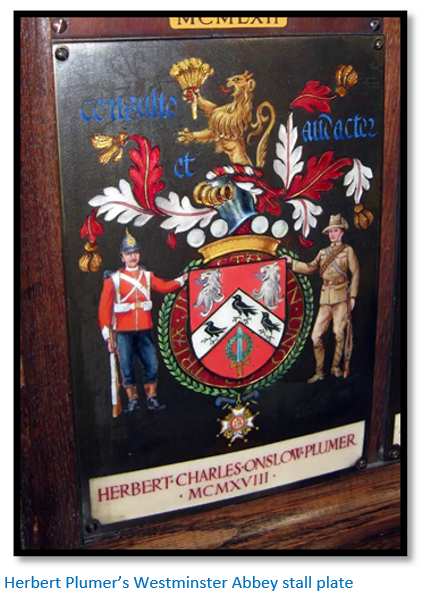

Herbert Plumer died at his home at 22 Ennismore Gardens on 16 July 1932 and was interred in the chapel of St George at Westminster Abbey. He had worshipped here regularly and knew all the vergers by their names. It was a great honour; the first military internment in Westminster Abbey in fifty years.[xlvii]

The previous night his body lay in state at the Guards Chapel and covered with the same faded Union Jack used at Haig’s funeral four years earlier. Amongst the pall-bearers were Baden-Powell and Cavan, Trenchard and Robertson, Allenby and Jacob dressed in their plumed hats and full dress uniforms.

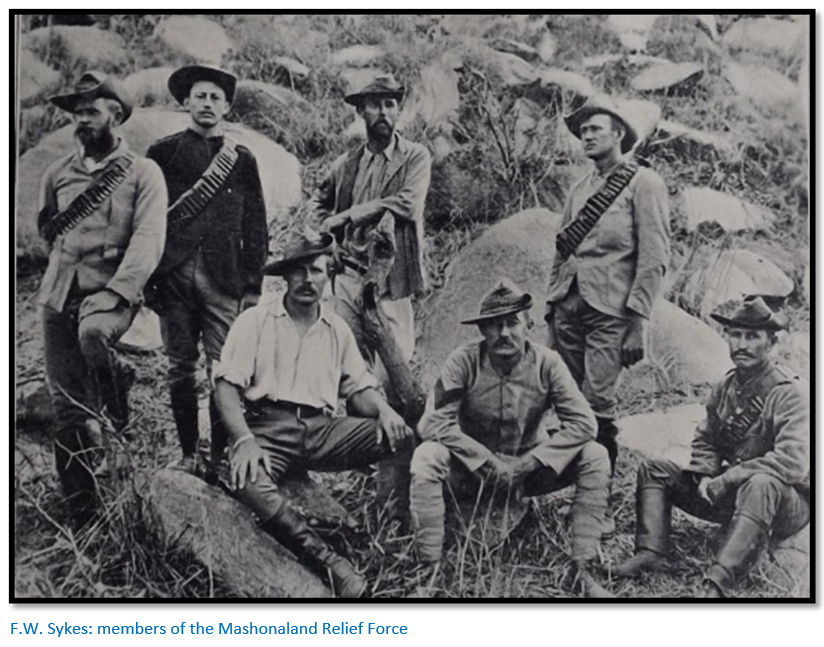

Note: Plumer’s stall plate has an image of a trooper from the Matabele Relief Force or the Boer War. See the earlier Sykes’ photo of members of the Matabele Relief Force with the left-hand hat brim turned up in the same distinctive style.

His wife Annie Constance (née Goss) Plumer died on 18 May 1941 and is buried at Putney Vale cemetery.

References

L.S. Amery (Ed) Times History of the War in South Africa, 1899-1902; Vol 1-5. Sampson, Low and Marston 1902-7

R.S. Burrett. Plumer’s Men. Just Done Productions, Durban 2009

I.J. Cross. The ordnance and machine guns of the British South Africa Company Part Two: 1895-1896. Military History Journal Volume 16, No 3 – June 2014

C. Harrington. Plumer of Messines. John Murray, London, 1935

H. Plumer. An Irregular Corps in Matabeleland. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co, 1897

E.G. Lengel. MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History: The Day the Earth Blew Open. Vol. 29, No 2 - 2017

G. Powell. Plumer; The Soldiers’ General. Leo Cooper, London, 1990

M. Snape. God and the British Soldier: Religion and the British Army in the First and Second World Wars. Routledge, 2005

F.W. Sykes. With Plumer in Matabeleland. Books of Rhodesia. Bulawayo, 1972

Field Marshal Herbert Plumer - World War One Commander". HistoryLearning.com. 2019. Web.

Steve Upton. YouTube video on Messines mine craters

Wikipedia – Battle of Messines

[i] Barber, Taylor, Sewell (Eds) From the Reformation to the Permissive Society: a miscellany in celebration of the 400th Anniversary of Lambeth Palace Library. The Boydell Press, 2010. P470

[ii] Snape, P49

[iii] Powell writes that at Eton he was known as a pleasant, lively but undistinguished boy; even at cricket, later his passion, he played only for his house.

[iv] Powell, P13. Robert Baden-Powell “B-P” passed the same Sandhurst entrance examination.

[v] Ibid, P14

[vi] Harrington. Letter to his fiancée Annie Constance, P4

[vii] Ibid, P5

[viii] Lieutenant-General Sir William Howley Goodenough was General Officer Commanding-in-Chief from December 1894 to 1898; he was briefly in 1897 Governor of the Cape Colony.

[ix] Harrington, P12

[x] Hon. Maurice Gifford (1859 – 1910) and at the time was the general manager of the Bechuanaland Exploration Company During the Matabele rebellion or Umvukela which broke out in March 1896 he raised Gifford’s Horse and lost his arm in an engagement with the amaNdebele.

[xi] First Matabele War in which battles were fought at Shangani river on 25 October and at Bembesi on 1 November 1893 – both are described on this website.

[xii] Harrington, P14-15

[xiii] Plumer, P3

[xiv] Ibid, P9

[xv] Earl Grey was Administrator from 2 April 1896 – 5 December 1898

[xvi] Plumer,P23

[xvii] Powell, P29

[xviii] Sykes, P57

[xix] Ibid, P58

[xx] Plumer, P214

[xxi] Plumer, P34

[xxii] Powell, P30

[xxiii] Sykes, P65

[xxiv] Plumer. P48

[xxv] Sykes, P73

[xxvi] Ibid, P80

[xxvii] The ordnance and machine guns of the British South Africa Company Part Two: 1895-1896. Military History Journal Volume 16, No 3 – June 2014

[xxviii] Sykes, P90

[xxix] Ibid, P97-98

[xxx] Ibid, P98-99

[xxxi] Plumer, P150

[xxxii] See article on Fort Umlugulu and the cemetery on the website. The memorial bears Sgt Warringham’s name although he is buried in Bulawayo cemetery

[xxxiii] Harrington, P4

[xxxiv] Plumer, P203-4

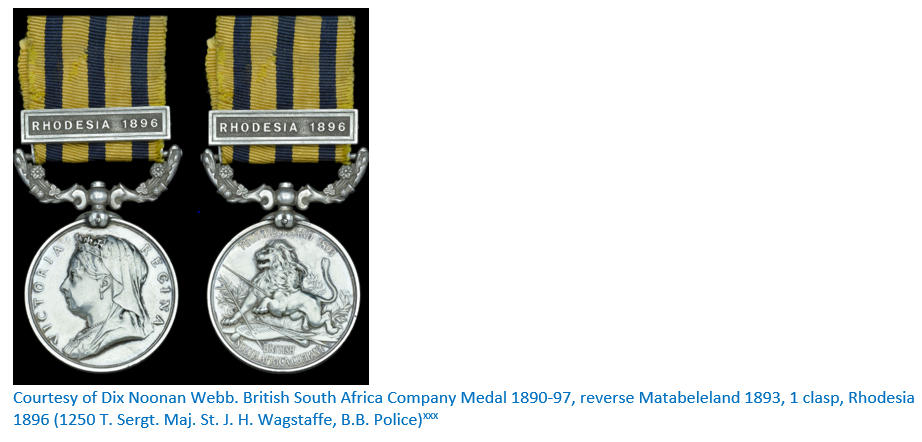

[xxxv] A rare Jameson Raider’s British South Africa Company’s 1890-97 Medal awarded to Troop Sergeant-Major St. J. H. Wagstaffe, Bechuanaland Border Police, afterwards a Sergeant in the Matabeleland Relief Force in the 1896 Rebellion and a Guide in the Field Intelligence Department in the Boer War

[xxxvi] Powell, P52

[xxxvii] Times History, P208

[xxxviii] Powell, P90

[xxxix] Author of Plumer of Messines and a source reference

[xl] Geoff Quick wrote the following review of the biography of Jack Norton-Griffiths (1871-1930) who was deported from the Transvaal following the Jameson Raid and made his way to Mashonaland, where he was a member of Honey’s Scouts during the 1896 Rebellion. In 1897 he joined the BSAP following a recommendation from Cecil Rhodes and in March was second in command at Fort Martin. In 1898/1899 he was O.C. Lomagundi District. After service during the Boer War he became an M.P. and subsequently volunteered for military service during the Great War. He also founded an International civil engineering company and was involved in projects in Africa, England and Canada. The book: Tunnel-Master and Arsonist of the Great War is written by Tony Bridgeland and Anne Morgan published by Leo Cooper, England 2003

[xli] Harrington, P301

[xlii] Ibid, P303

[xliii] Ibid, P294

[xliv] Ibid, P294

[xlv] Harrington, P326

[xlvi] Ibid, P328

[xlvii] Powell, P321