Baden-Powell in Matabeleland during 1896 where he learned the principles of Scouting

Introduction

Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell (22 February 1857 – 1941) (he pronounced his name 'Poel') from very early in his life was called Stephe (pronounced Steevie) by his family, ‘B-P’ by everyone else and would only be known as Robert after he was knighted and chose to be Sir Robert. Even his surname which had been Baden was ‘improved’ by his mother to Baden-Powell.

Tim Jeal in his outstanding biography describes ‘B-P’ as an: “actor, artist, spy, hoaxer, female impersonator, author, sportsman and inspired Regimental Commander, Baden-Powell was a dazzling personality, and yet he was dominated by his formidably ambitious mother and remained acutely anxious about his manliness.” Smyth was the maiden name of his mother, Henrietta Grace. His first two names were after his godfather, only son of the famous engineer, who died when Stephe was two years old. ‘B-P’ himself wrote: “It is a well-established fact that very many of the greatest men in the world have acknowledged that they owe much of their success to the influence of their mother.” The Boy Scouts of America Collection alone has approximately two thousand letters written by ‘B-P’ to his mother between 1877 – 1814.

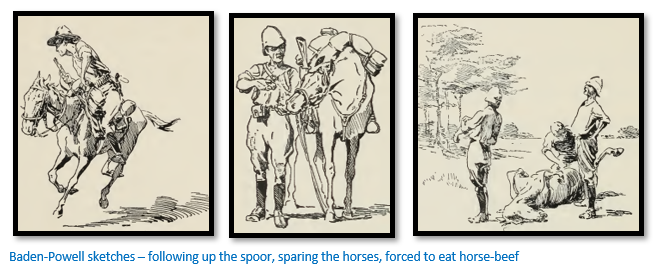

‘B-P’ recalled that John Ruskin, seeing him drawing with his left hand, advised his mother to let him continue using both hands – in those days parents tried to ‘cure’ left-handed actions. ‘B-P’ became ambidextrous that proved of great advantage to an artist, soldier and scout. At school he could draw with one hand and shade with the other. Lieut-General Godley who served under ‘B-P’ at the siege of Mafeking said that the trick of drawing with one hand and writing with the other never failed to draw an amused audience.

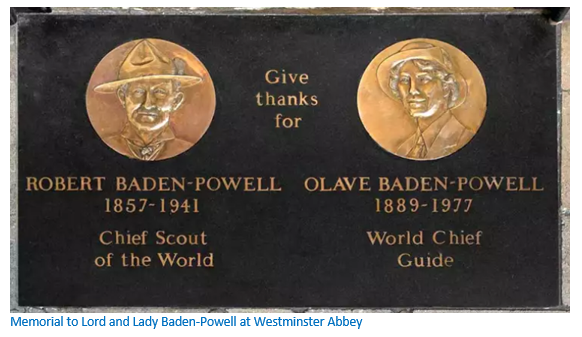

There is a memorial stone to Lord and Lady Baden-Powell in Westminster Abbey which replaced an earlier stone to Lord Baden-Powell unveiled in 1947.

The Westminster Abbey website tribute to his life entirely omits any description of 1896 - the year he was in Matabeleland – this is a major omission as Matabeleland was the first time that ‘B-P’ was able to put his theories into practice and demonstrate that scouting and reconnaissance were vital to military operations – these skills were then subsequently adapted for use during the 217 day siege of Mafeking and incorporated into the Boy Scouts movement in 1907.

Life and Career

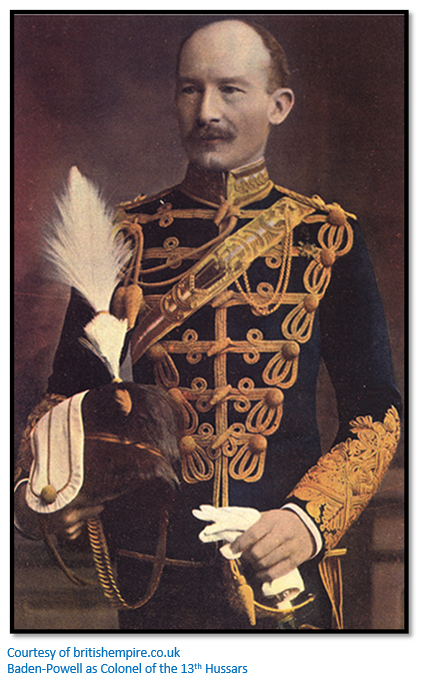

‘B-P’ joined the 13th Hussars in 1876 as a nineteen year old 2nd lieutenant. Unlike his brothers, he had failed his entrance exams at Balliol College at Oxford being “not quite up to Balliol form.” However, when it came to a military career, there were 718 candidates sitting the examination for commissions in the infantry and cavalry; he came fifth in the infantry and second in the cavalry and was gazetted straight into the regiment, then stationed in India. From the start he showed an aptitude for and enjoyment of military scouting and irregular warfare. He also developed an aptitude for pig-sticking, winning the inter-regimental cup in 1883. ‘B-P’ took part in the Zululand (1888) the Ashanti (1895) and Matabele (1896) campaigns.

After Matabeleland ‘B-P’ was posted to the Gold Coast and served in the Fourth Ashanti War. In 1897 at the age of 40 years old, he was brevetted Colonel, the youngest of this rank in the British Army and given command of the 5th Dragoon Guards in India.

While he was on leave in England in 1899 he was summarily appointed to raise a force of mounted rifles to be based in Mafeking with the secret aim of making raids on the Boers in Transvaal.

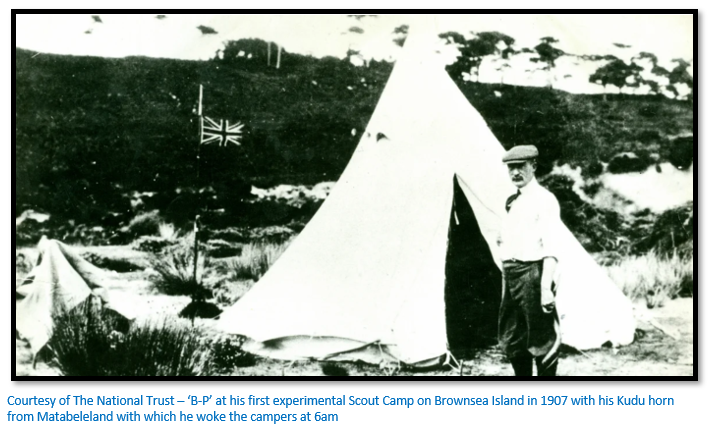

During the Boer War he held Mafeking under siege for 217 days until relieved. In 1910 he retired from the army in order to devote himself to the Boy Scout movement which he founded.

B-P was appointed Colonel of the 13th Hussars in 1911. He remained as such through the amalgamation with the 18th Hussars.

A detailed summary of his military life and career is given at the end of this article.

Note to readers. Readers are reminded that many of the quotes were written a long time ago and use terms and expressions that were current at the time, regardless of what we may think of them today. For reasons of historical accuracy they have been included in their original form with asterisks. Also, I have converted ‘B-P’s miles into kilometres.

BP’s military experience prior to Matabeleland

With his regiment, the 13th Hussars at Lucknow ‘B-P’ completed an eight month garrison course and was posted to Kandahar in Afghanistan and drew maps of the battlefield of Maiwand where the British force had been defeated which were later used in the court-martial of the officers involved. On outpost duty and reconnaissance he much admired the Afghans ability to move silently and their courage and fighting qualities.

Back in India he enjoyed polo and pig-sticking as: “It teaches a man to ride by forcing him to exert to the utmost all his riding powers without any effort of mind; by making him anticipate the moves of the boar and regulate his own accordingly and to the best advantage of the ground; it teaches a man to use his wits and powers of observation, and gives him an eye for country; it trains him to decide in his course of action without a moment’s hesitation; it gives him practice in the use of a weapon while moving at speed, in an encounter with a strong, infuriated boar, it teaches him self-reliance and to keep his head and his pluck in an emergency; in a word, it excels all other methods of training in essential qualifications of a successful soldier on active service.”

At Muttra in 1883 he won India’s greatest prize for pig-sticking; the Kadir Cup.

In 1884 the 13th Hussars were moved to Natal as support for the Warren expedition because the Transvaal Boers with the support of Germany were attempting to annex Bechuanaland. No fighting was carried out, but ‘B-P’ carried out a month long reconnaissance of the Drakensberg mountains and corrected the existing maps.

Back in England he trained his squadron to use hand-signals instead of shouted orders and honed his spying activities on holiday in Germany and by observing Russian manoeuvres.

By 1888 he was back in South Africa as aide-de-camp (ADC) to his uncle, General Sir Smythe, General Officer Commanding (GOC) South Africa where his uneventful life was interrupted by unrest in Zululand led by Cetewayo’s son, Chief Dinizulu. Dinizulu’s army reinforced by other Zulu, soon had Asst-Commissioner Pretorius trapped in his fort at Umsundusi, fifty miles from Eshowe.

General Smythe send 500 troops of the Inniskilling Dragoons and Fusiliers and 2,000 ‘friendly’ Zulus under John Dunne; the whole force under Major McKean with ‘B-P’ as staff officer to relieve the fort. ‘B-P’ never forgot the sight of the Zulus advancing in three long lines and chanting their songs in parts – it became the basis of the Een-gon-yama chorus – known to thousands of Boy Scouts.

The relief march under appallingly wet conditions covered fifty miles in two days and relieved the fort. McKean gave much credit to his staff officer: “I beg to bring to the notice of the Lieutenant- General Commanding, the invaluable services rendered me by Captain Baden-Powell. This officer’s unflagging energy, his forethought and thorough knowledge of all military details were of the greatest assistance to me.” ‘B-P’ was kept busy in the field rounding up small groups of Zulu’s, seizing arms and receiving surrenders. For his useful work ‘B-P’ was appointed Brevet Major and appointed military secretary to the GOC at Cape Town.

General Smythe wanted to crush the Zulu; Sir Arthur Havelock, the Natal Governor thought the Zulu were misguided and wished to hold back the military forces – this was a situation that ‘B-P’ was to experience in Matabeleland between General Carrington and Sir Hercules Robinson when he ordered the execution of Chief Uwini. His military experiences brought ‘B-P’ to the attention of the Adjutant-General of the Army, Lord Wolseley who had also fought the Zulu in 1879.

In 1889 he was sent to Swaziland which was still independent although the Transvaal Boers had designs on the territory and were steadily infiltrating – ‘B-P’s precis of the situation led to his being appointed private secretary of the British Commissioner, Sir Francis de Winton. Eventually dual Boer-English administration was set-up, but it did not work well and a British Protectorate was established in 1906. This experience of political negotiation and compromise was to prove useful experience to ‘B-P.’ He admired the Zulu method of training their youth which was to send them alone into the forest or veld with weapons to ‘live off the land’ – he thought it encouraged initiative and taught them to fend for themselves which developed fitness, resource and self-reliance in the boys.

In 1890 he accompanied his uncle General Sir Smythe as military secretary and ADC to Malta. Armed with a butterfly net and sketch book he surreptitiously made plans of forts in the Adriatic and the Bosphorus and watched military manoeuvres.

In 1893 he resigned his Malta post and re-joined the 13th Hussars in Ireland and caught the eye of General Wolseley, the Army’s Commander-in-Chief. A year later on manoeuvres in Berkshire he was Brigade-Major to General French and gained a special mention for the smooth handling of scouting and reconnaissance. Wolseley asked ‘B-P’ for a report on cavalry machine-gunners.

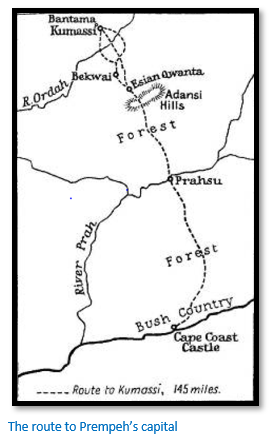

In 1895 Wolseley picked him for special services in West Africa. Prempeh. the King of Ashanti had refused all attempts to make his country a British Protectorate. Sending troops up a narrow path through thick jungle for 145 miles called for organization and precaution. In charge was Colonel Sir Francis Scott and ‘B-P.’ Native levies were raised and armed; bridges built, seven supply bases constructed and a telegraph line laid alongside the track; tsetse fly ruled out the use of horses so native carriers were hired. After a difficult and dangerous journey which took a month in wet conditions the King’s village at Kumassi was reached and taken without fighting. Prempeh was forced to pay tribute and exiled to the Seychelles.

For his part ‘B-P’ was promoted to Brevet Lieut-Colonel at the age of thirty-eight and re-joined his Regiment, the 13th Hussars in Ireland with the next step in Matabeleland, but first some background to the events there.

Scouting

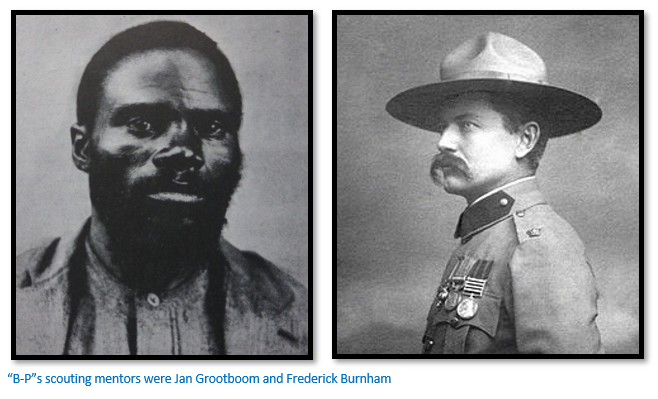

It will be seen from the text that ‘B-P’ learned many of the practical skills of surviving in the wild and the skills of scouting from his military experiences in Matabeleland. The two scouting practitioners who taught him the most about the art of scouting were both present in Matabeleland in 1876 – Jan Grootboom described below and Frederick Russell Burnham, the American Scout who had managed to escape the disaster of the Shangani patrol disaster on 4 December 1893 when he was sent by Allan Wilson with Ingram and Gooding to get reinforcements from the main column. Burnham was ‘B-P’s inspiration for the Boy Scout movement and in later life played a large part in the Boy Scouts of America earning their highest honour and was active in the organisation until his death in 1947.

B-P’s Book The Matabele Campaign 1896

The book was written as an illustrated diary and in the preface written on 12th December 1896 at Umtali, Mashonaland he wrote:

My dear Mother,—It has always been an understood thing between us, that when I went on any trip abroad, I kept an illustrated diary for your particular diversion. So I have kept one again this time, though I can’t say that I’m very proud of the result. It is a bit sketchy and incomplete, when you come to look at it. But the keeping of it has had its good uses for me.

Firstly, because the pleasures of new impressions are doubled if they are shared with some appreciative friend (and you are always more than appreciative).

Secondly, because it has served as a kind of short talk with you every day.

Thirdly, because it has filled up idle moments in which goodness knows what amount of mischief Satan might not have been finding for mine idle hands to do!

Jameson Raid and outbreak of the Matabele Rebellion or Umvukela

Jameson had taken with him nearly the entire British South Africa Company’s (BSAC) Police force leaving the country nearly defenceless. The Matabele rebellion or Umvukela was well-planned and co-ordinated to begin on the full moon of 29 March, but on 20 March warriors in the Esigodini area, south of Bulawayo, killed a native policeman. Over the next week over two hundred Europeans were killed on outlying stores, ranches and mines.

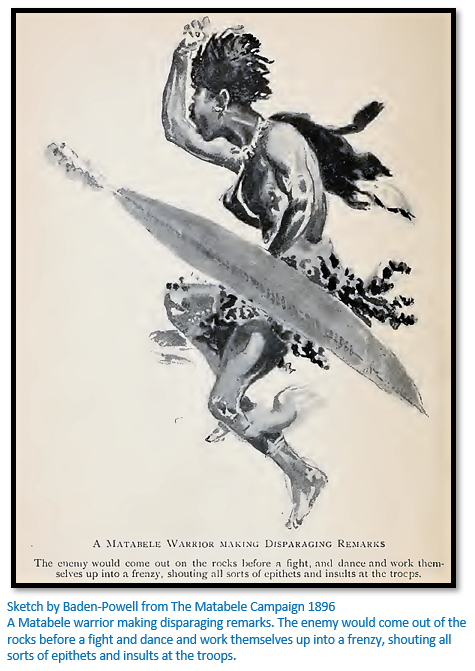

‘B-P’ wrote: “Patrols were promptly sent out to bring in outlying farmers, and to gather information as to the rebels’ moves and numbers. ‘Ere long the rebel forces were closing round Bulawayo. North, east, and south they lay, to the number of seven thousand at the least. Throughout the country their numbers must have been but little under ten to thirteen thousand.

Nearly two thousand of them were armed with Martini-Henry rifles. A hundred of the Native Police deserted and joined them with their Winchester repeaters. Many of them owned Lee-Metfords, illicitly bought, stolen, or received in return for showing gold-reefs to unscrupulous prospectors. And numbers of them owned old obsolete elephant guns, Tower muskets, and blunderbusses. So that in addition to their national armament of assegais, knobkerries, and battle-axes, the rebels were well supplied with firearms and also with ammunition.”

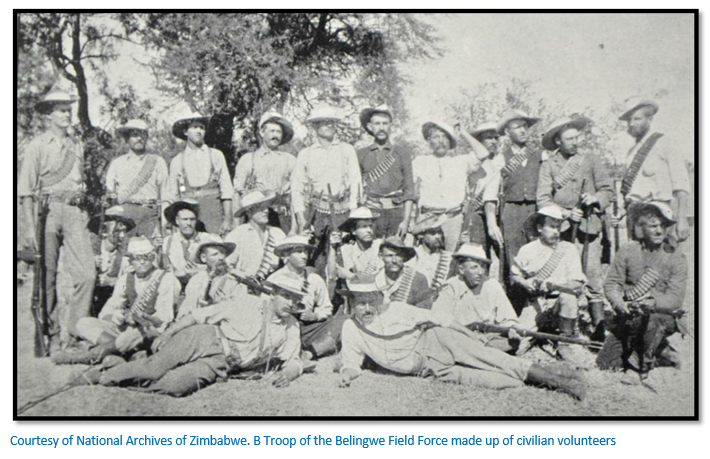

The remaining settlers (there were an estimated three to four thousand Europeans in the country at the time) retreated into laagers of sandbagged wagons at Bulawayo, Gwelo, now Gweru, Selukwe now Shurugwi, and Belingwe now Mberengwa, which were fortified with barbed wire, the area outside covered in smashed glass. Those few remaining British South Africa Company Police plus civilian volunteers were formed into the Bulawayo Field Force (BFF) These forces rode out to rescue settlers as soon as they were mustered and once sufficient defences static defences were in place went on the offensive against the amaNdebele. Mounted patrols were sent out under Selous to the south and Maurice Gifford to the Insiza river.

‘B-P’ wrote: “We now went through the Mangwe Pass. The road here winds its way through a tract of rocky hills and koppies, which are practically the tail of the Matopo range, running eastward hence for sixty miles. It would have been a nasty place to tackle had the Matabele held it. They might easily here have cut off Bulawayo from the outer world, but their M’limo, or oracle, had told them to leave this one road open as a bolt‑hole for the whites in Matabeleland. They had expected that when the rebellion broke out, the whites would avail themselves en masse of this line of escape; they never reckoned that instead they would sit tight and strike out hard until more came crowding up the‑road to their assistance.”

In late May two relief columns arrived in Bulawayo on almost the same day; Rhodes and Beale bringing a relief column of two hundred and fifty men from Victoria, now Masvingo and Salisbury, now Harare in Mashonaland and Lord Grey and Plumer Kimberley and Mafeking with the Matabeleland Relief Force of six hundred Europeans and two hundred Fengu soldiers, previously known as Fingo from the Eastern Cape.

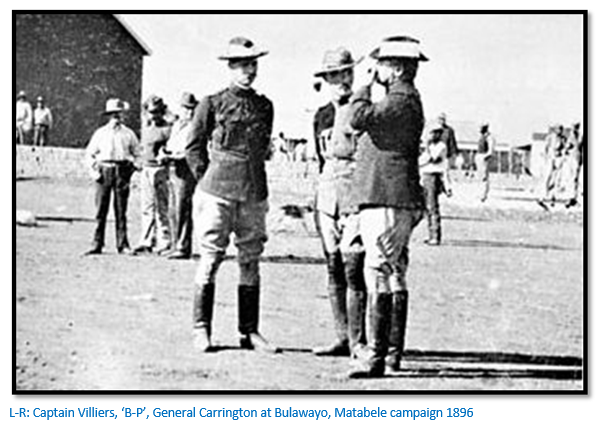

Major-General Carrington appointed to lead the Imperial Forces in Matabeleland

Carrington since 1885 had been Commander of the Bechuanaland Border Police (BBP) and from 1889 expanded this force on the orders of the Colonial Office in order to provide an armed protection force to accompany the British South Africa Company’s Pioneer Column into Mashonaland from Macloutsie on 28 June 1890 until its disbandment at Salisbury on 1 October 1890. This force was led by Lieut-Col. Edward Graham Pennefather [See the article on Pennefather under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

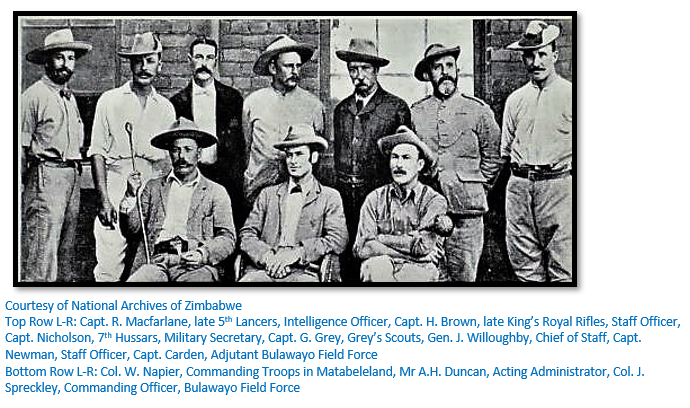

Carrington left the BBP in 1893 to act as military adviser to Sir Henry Loch, High Commissioner for Southern Africa in Cape Town and in 1895 on receiving his promotion to Major General he left Africa for a new appointment as military commander of the Gibraltar garrison. This did not last long as on 18 May 1896 he was appointed in command of all military forces in the Bechuanaland Protectorate, Matabeleland and Mashonaland. These comprised the BBP, Bulawayo Field Force (BFF) the Matabeleland Relief Force (MRF) under Plumer, Imperial troops under Alderson and two companies of Fengu soldiers (often referred to at the time as Cape Boys)

In view of all his experience in South Africa from consolidating Britain’s hold over Griqualand West in 1876 to the various frontier wars against the Xhosa in 1877, the Pedi in North-Eastern Transvaal in 1878, the Basuto Gun War of 1880-81, Carrington seemed a sensible choice, however Oliver Ransford portrays him as: “now a swollen caricature of the dashing cavalry officer.”

Appointment of Baden-Powell as Chief of Staff

Soon after the debacle of the Jameson Raid (29 December 1895 – 2 January 1896) ‘B-P’ was in his barracks at the end of the Falls Road in Belfast; the squadron’s horses stabled with the Shire and Clydesdale horses known as “trammers” that pulled the city’s trams. The regimental parade ground was so boggy that riding instruction was carried out the main road: “which was hard on the horses’ legs and considerably interfered with the traffic” as well as dangerous…in the last week of April a trooper fell from his horse and subsequently died. ‘B-P’ was officiating at his funeral when a telegram arrived from General Sir Frederick Carrington that said that Carrington was leaving for South Africa enroute to Matabeleland and wanted ‘B-P’ as his Chief Staff Officer.

WAR OFFICE, S.W., 28th April 1896.

SIR,

Passage to Cape Town having been provided for you in the s.s. Tantallon Castle, I am directed to request that you will proceed to Southampton and embark in the above vessel on the 2nd May by 12.30 p.m., reporting yourself before embarking to the military staff officer superintending the embarkation.

You must not ship more than 55 cubic feet.

I am further to request you will acknowledge the receipt of this letter by first post and inform me of any change in your address up to the date of embarkation.

You will be in command of the troops on board.

I have the honour, etc.,

EVELYN WOOD, Q.M.G.

Field Marshall Viscount Wolseley, Commander in Chief of British Forces, named Major-General Sir Frederick Carrington, now 51 years old, to command the British forces being sent to Matabeleland. Wolseley had visited George Baden-Powell, then Conservative MP for Liverpool Kirkdale and ‘B-P’s elder brother at his house in Eaton Square on 14 April 1896 where George urged Wolseley to appoint Carrington to command the Imperil forces destined for Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe.

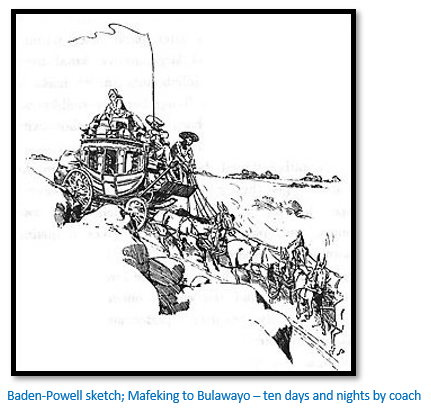

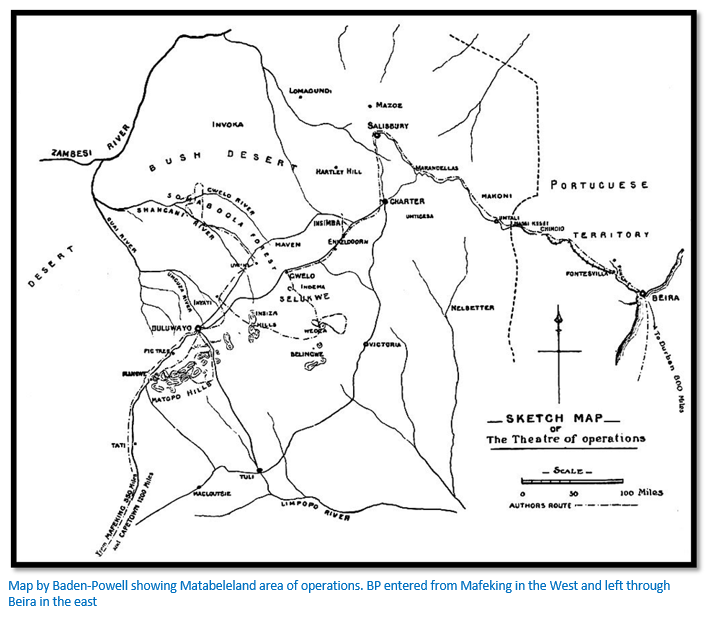

In early May ‘B-P’ was onboard the S.S. Tantallon Castle for South Africa and left Cape Town on 19 May arriving sixty hours later in Mafeking. “At last, after three nights and two days jogging along in the train, we rattle into Mafeking at 6am…Sir Frederick is here, and we, the staff, take up our quarters for a few days in a railway carriage on a siding. The staff consists of Lieutenant‑Colonel Bridge, A.S.C., as Deputy Assistant Adjutant‑General (for Transport and Supply), Captain Vyvyan, Brigade Major; Lieutenant V. Ferguson, A.D.C. my billet is Chief Staff Officer.” The rinderpest had killed almost all the cattle and transport was scarce and ‘B-P’ joined Carrington and other officers for the nine hundred kilometre journey in a Zeederberg coach drawn by mules: “Packed up our kits, and in the, afternoon embarked, the four of us (the General, Vyvyan, Ferguson, and self) in the coach for Bulawayo. The coach a regular Buffalo Bill‑Wild West‑Deadwood affair; hung by huge leathers on a heavy, strong‑built undercarriage ; drawn by ten mules. Our baggage and three servant-soldiers on the roof ; two native drivers (one to the reins, the other to the whip). Inside are four transverse seats, each to hold three, thus making twelve "insides." Luckily we were only four, and so we had some room to stretch our legs. We each settled into a comer, and off we went, amid the cheers of the inhabitants of Mafeking. One, more eager than the rest, a former officer of Sir Frederick’s in the Bechuanaland Police, jumped on, and came with us for thirty miles, trusting to chance to take him back again.”

‘B-P’ noted: “Thus, when we arrived a week later, we found that the immediate neighbourhood of Bulawayo had been cleared of the enemy, but the impis were still hanging about in the offing and required to be further broken up.

The General’s plan, accordingly, was to send out three strong columns simultaneously to the north-east, north, and north-west, for a distance of some sixty to eighty miles, to clear that country of rebels, and to plant forts which should prevent their reassembly at their centres there and would afford protection to those natives who were disposed to be friendly. The southern part of the country, namely, the Matopo Hills, was afterwards to be tackled by the combined forces on their return from the north. Such was the situation in the beginning of June.”

Baden-Powell’s role in Matabeleland

Initially his role as Carrington’s Chief Staff Officer was complete charge of all the administration connected with military stores and materials, transport, munitions, remounts and medical supplies for the entire force. He worked from a small corrugated-iron shed sending orders by telegraph; the amaNdebele had failed to cut the telegraph line connecting Bulawayo with Mafeking. Existing supplies in the country were almost exhausted and the rinderpest had killed most of the transport oxen.

“The office work, although exacting, is most interesting all the same; the only drawback is that there are not more than twenty-four hours in a day in which to get it done. I certainly do look forward, though, to the hour of luncheon; yes, it sounds greedy but it is for the glimpse of sunlight that I look forward, not the lunch. That is scarcely pleasant either to look forward to or to look back on, consisting, as it generally does, of hashed leather, which has probably got rinderpest, no vegetables, and liquid nourishment at prohibitive prices, e.g. local beer at 2s. a glass. I live on bread, jam, and coffee, and that costs 5s. a meal; and prices are rising! Fags are 32s. a dozen, and not guaranteed fresh at that.”

He was praised for his military orders which in a few lines: “told all one wanted to know and in other things, left one a free hand.” Another Officer said: “He never seemed to be in a hurry, or to be overworked, or have a care on his mind.”

He was also known for his eccentric dress which included wearing: “a peculiar pair of riding breeches…like those effected by stage inn-keepers or Tyrolean hunters” and another trooper remembered ‘B-P’ wearing a cowboy hat and holsters for two revolvers.

When the military operations moved from a defensive to a more offensive role with the engagements at Ntaba zika Mambo and in the Matobo Hills the logistical problems around the supply and transport of men and supplies became more complicated and ‘B-P’s workload increased considerably.

Baden-Powell’s first engagement on the Umgusa river with the amaNdebele

On the evening of 5 June Sir Charles Metcalfe and Frederick Russell Burnham came into Carrington ‘s office; they had been planning to visit Beale’s relief force five kilometres out of town but stumbled upon a large hidden impi near the Umgusa river and quickly returned to Bulawayo.

“There, in the early dawn, I was at last able to see the enemy clear enough. On the opposite bank of the Umgusa River they were camped in long lines, fires burning merrily, and parties of them going to and from the stream for water. I took my information on to Beal’s camp. I was much taken with the coolness with which the news was received there. It was not above two miles and a half from that of the enemy.

Our strength was 250 mounted men, with two guns and an ambulance. The country was undulating veldt covered with brush, through which a line of mounted men could move at open files.

As we advanced, we formed into line, with both flanks thrown well forward especially the right flank under Beal, which was to work round in rear of the enemy on to their line of retreat, a duty which was most successfully carried out. The central part of the line then advanced at a trot straight for the enemy’s position.

The enemy were about 1,200 strong, we afterwards found out. They did not seem very excited at our advance, but all stood looking as we crossed the Umgusa stream, but as we began to breast the slope on their side of it, and on which their camp lay, they became exceedingly lively, and were soon running like ants to take post in good positions at the edge of a long belt of thicker bush. We afterwards found that their apathy at first was due to a message from the M’limo, who had instructed them to approach and to draw out the garrison, and to get us to cross the Umgusa, because he (the M’limo) would then cause the stream to open and swallow up every man of us. After which the impi would have nothing to do but walk into Bulawayo and cut up the women and children at their leisure.

But something had gone wrong with the M’limo’s machinery, and we crossed the stream without any contretemps. So, as we got nearer to the swarm of black heads among the grass and bushes, their rifles began to pop and their bullets to flit past with a weird little ‘phit, phit,’ or a jet of dust and a shrill ‘wh-e-e-e-w’ where they ricocheted off the ground. Some of our men, accustomed to mounted infantry work, were now for jumping off to return the fire, but the order was given: No; make a cavalry fight of it. Forward! Gallop!”

This was ‘B-P’s first and only cavalry charge in his career. He has several close escapes from death – a warrior dropped to his knees and fired at point-lank range but missed and a shot fired from a tree struck the ground at his feet.

In this action they suffered only four men seriously wounded and four horses killed; he later admitted that: “this was a very one-sided fight and it sounds rather brutal to anyone reading in cold blood how we hunted them down without giving them a chance – but it must be remembered we were but 250 men against at least 1,200.”

This battle was a turning point for the amaNdebele and by the time Carrington arrived on 22 June 1896 the amaNdebele had begun to lose the initiative and split into two main groups; the smaller one heading for Ntaba zika Mambo and the larger for the Matoppos hills, now called the Matobo. Both held Mlimo shrines and offered refuge in granite kopjes honeycombed with caves and hiding places covered with thick bush and slashed with ravines - ideal terrain for waging irregular warfare. In the 1893 occupation of Matabeleland the amaNdebele impis had experienced the devastating firepower of the Maxim guns and would not engage in full-frontal attacks again.

Ntaba zika Mambo

Within a short period of his arrival Carrington had given Plumer permission to use most of their combined force for a full-scale attack on Ntaba zika Mambo. The force left Inyati, now Inyathi Mission on the night of 5 July

“Colonel Plumer accordingly took a column out there, nearly 800 strong, and, after a clever and most successful night-march, surprised the enemy, at dawn, on 5th July, in a desperate-looking kopje stronghold called Ntaba zika Mambo. There was some tough fighting, and the newly-arrived corps of "Cape Boys" (natives. and half-castes from Cape Colony), much to everybody’s surprise, showed themselves particularly plucky in storming the koppies; but, as in the case of most natives, their élan is greatly a matter of what sort of leaders they have, and in this case there was every reason for them to go well. Major Robertson, their commandant, an old Royal Dragoon, is a wonderfully cool, keen, and fearless leader under fire.

In the end the place and its many caves was taken. Our loss amounted to ten killed, twelve wounded. The enemy lost 150 killed, and we got some 600 prisoners, men, women, and children, 800 head of cattle, and a very large amount of goods which had been looted from stores and collected at this place as the property of the Mlimo. It was a final smash to the enemy in the north, though Mkwati, the local priest of the Mlimo, and Uwini, his induna, both escaped.

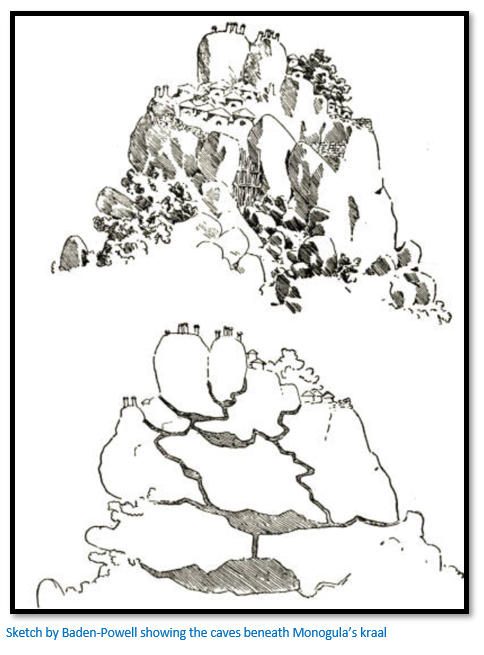

The Mlimo’s cave was found, a most curious place, which I visited later on: a sort of ante-room in which suppliants had to wait while the priest went away to invoke the Mlimo’s attention; then a narrow cleft by which they would walk deep into the rock, and which narrowed till it looked like a split just before the end of the cave. And through this crevice they made their requests and got their answer from the Mlimo. In reality, another cave entered the hill from the opposite side and led up to this same crevice, and it was by this back entrance that the priest re-entered and sitting in the dark corner just behind the crevice, he was able to impersonate an invisible deity with full effect.

Of such caves there are three or four about the country, where the rebels must now get their orders as to their course of action.”

Although large numbers of women and children and cattle were captured, the main body of amaNdebele fighters managed to escape to the Matobo hills the refuge of the Mlimo, their spiritual leader. Mkwati the spiritual leader at Ntaba zika Mambo and his father-in-law Chief Uwini escaped east to the Somabhula forest. [See the article Battle of Ntaba zika Mambo, Manyanga or Mambo Hills under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

‘B-P’ comments as follows: “I was scouting out with my native boy [Jan Grootboom] in the neighbourhood of the Matopos. Presently we noticed some grass-blades freshly trodden down. This led us to some foot-prints on a patch of sand; they were those of women or boys, because they were small; they were on a long march [about 110 kilometres from Ntaba zika Mambo to the Matobo] because they wore sandals; they were pretty fresh, because the sharp edges of the foot-prints were still well-defined, and they were heading for the Matopos. Then my n****r, who was examining the ground…suddenly started…found not a foot-mark, but a single leaf. But that leaf meant a great deal, it belonged to a tree that did not grow in this neighbourhood, though we knew of such trees ten or fifteen miles away. It was damp and smelt of k****r beer. From these two signs then, the foot-prints and the beery leaf, we were able to read a good deal. A party of women had passed this way, coming from a distance ten miles back, going toward the Matopos and carrying beer…They had passed this spot about 4 o’clock that morning, because at that hour there had been a strong wind blowing, such as would carry the leaf some yards off their track…”

Reconnaissance into the Matobo

Co-ordinated attacks were made into the Matobo hills in late July and early August but resulted in a short engagements during which the amaNdebele withdrew further into the hills without any military advantage for the MRF and they incurred heavy casualties.

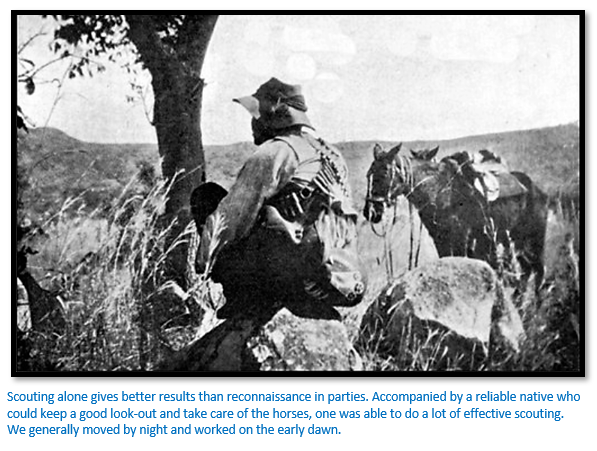

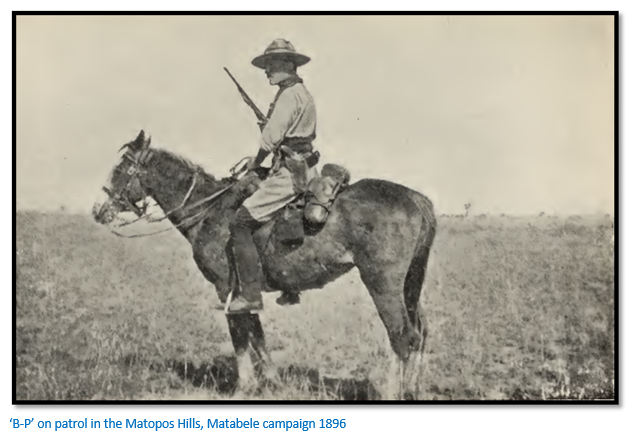

‘B-P’ made his first journey into the Matobo on 12 June with the American scout Frederick Burnham

In the following months he made six more exploratory missions into the Matobo generally just with one or two companions. He was delighted to discover that the amaNdebele had given him a nickname as was their custom which was “Impeesa” – the hyena or creature that does not sleep but walks about at night. ‘B-P’ as was his custom, changed the hyena into “the wolf that never sleeps” as his own translation and used it at the siege of Mafeking to enhance his reputation as a watchful military scout. The nickname was also used for a gun manufactured in the railways workshop at Mafeking using four-inch steel furnace pipe strengthened by rails bent into rings and a chassis from an old threshing machine. Scrap metal was melted down into spherical shells and the home-made gun named `the Wolf' in honour of Baden-Powell could fire an 8kg projectile almost 4,000 metres.

“The net result of our scouting to date is that we have got to know the nature of the country and the exact positions of the six different rebel impis in it, and of their three refuges of women and cattle. Maps have been lithographed accordingly and issued to all officers for their guidance. These maps have sketches of the principal mountains to guide the officers in finding the positions of the enemy.”

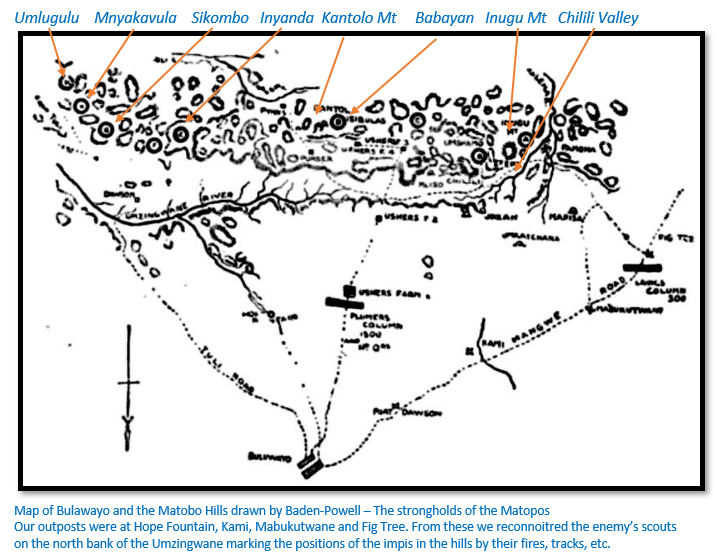

“The Matopo district is a tract of intricate, broken country, containing a jumble of granite-boulder mountains and bush-grown gorges, extending for some sixty miles by twenty. It lies to the south of Bulawayo, its nearest point being about twenty miles from that town. Along its northern edge, in a distance of about twenty-five miles, the six separate impis of- the enemy have taken up their positions, with their women and cattle bestowed in neighbouring gorges.

On the principle, Gutta cavat lapidem non vi sed saepe cadendo [a water drop hollows a stone not by force but by falling often] we have taken innumerable little peeps at them and have now marked down these impis and their belongings in their separate strongholds, a result that we could never have gained had we gone in strong parties.

Commencing at the western end, near the Mangwe road is the stronghold of the Inugu Mountain, a very difficult place to tackle, with its cliffs, caves, and narrow gorges. The impi occupies the mountain, while the women and cattle are in the neighbouring Famona valley.

Five miles N.E. of this is the Chilili valley, in which are women and cattle of Babayan’s impi. This impi is located deep in the hills near Isibula’s Kraal on the Kantolo Mountain; while Babayan himself, and probably the priest of the M’limo, are in a neighbouring valley.

Eighteen miles to the eastward, eight miles south of Dawson’s Store on the Umzingwane River, we come to a bold peak, that is occupied by Inyanda’s people, with a valley behind it, in which are Sikombo’s women and cattle.

A couple of miles farther west, Sikombo’s impi is camped behind a dome-shaped mountain close to the Tuli road.

On the west side of this road Umlugulu’s impi was stationed when we first began our reconnaissance, but he moved nearer to Sikombo, with Mnyakavula close by. Each impi numbered roughly between one and two thousand men. Their outposts were among the hills along the northern bank of the Umzingwane River. We used to pass between these by night, arriving near the strongholds at daybreak.”

Jan Grootboom

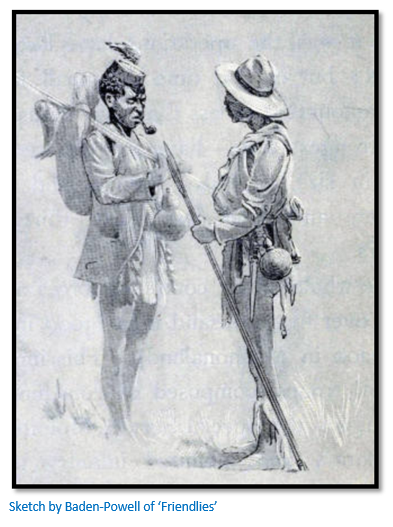

‘B-P’ went on several scouting missions with Jan Grootboom, an extremely skilful and resourceful Fengu (previously known as Fingo) from the Eastern Cape who made the initial contacts with the amaNdebele Chiefs that proceeded the first Indaba.

Baden-Powell learnt many of his scouting skills from observing Grootboom and in his memoirs of the Matabele Campaign in 1896, he frequently mentions him, although he incorrectly refers to him as a Zulu. Grootboom had come to Matabeleland as a wagon driver for Charles Helm, the missionary at Hope Fountain Mission. At the height of the campaign, Grootboom distinguished himself as a courageous and exceptional man especially when it came to night reconnaissance around the amaNdebele camps and outposts.

Baden-Powell writes: “He had the guts of the best of men. Though I knew Zululand, I was new to Rhodesia and its people and I needed therefore a really reliable guide and Scouting comrade.

To do our job he and I used to ride out from our outpost as soon as night had set in. This enabled us to get through the intervening 25 miles of country in good time to conceal ourselves near the enemy position at dawn, then to ascertain his exact whereabouts by observing his camp-fires as they lit up for cooking the morning meal. Our work lay among rocky kopjes. I found with my rubber-soled shoes I was able to get about more rapidly than Jan and in fact the enemy. In this way the enemy got to know me fairly well; they gave me the name of 'Impeesa'- the beast that creeps about at night.

One night we had crept down to near the enemy stronghold and were waiting there to see his morning fires so as to ascertain his position. Presently the first fire was lit and then another and yet another. Jan suddenly growled: The brutes are laying a trap for us. He slipped off all his clothing and left it lying in a heap and stole off into the darkness practically naked. The worst of spying is that it makes you suspicious, even of your best friends; so as soon as Jan was gone I crept away in another direction, taking the horses with me, and got among some rocks where I would have some chance if he had any intention of betraying me. For an hour or more I lay there while the sun rose until, at last, I saw Jan crawling back through the grass - alone. Ashamed of my doubts, I crept to him and found him grinning all over with satisfaction while he was putting on his clothes again. He said that he had found, as he had expected, an ambush laid for us. The thing that made him suspicious was that the fires, instead of flaring up at different points all over the hillside simultaneously, had been lighted in steady succession, one after the other, apparently by one man going around to light them. He himself had pressed in towards them by a route from which he was able to perceive a party of them lying out in the grass close to the track which we should probably have used had we gone on.”

Grootboom had great respect for Baden-Powell who he called “Colonel Baking Powder” an obvious reference to ‘B-P’ and taught him many of the basic techniques of scouting and reconnaissance. Always to check for any clothing that might betray his presence, avoiding the skyline and keeping perfectly still for long periods. Scouting mostly at night when it was easier to slip between sentries; always having an alternative escape route and returning by a different route to avoid an ambush.

“For efficient scouting in rocky ground, in the dry season, India rubber-soled shoes are essential; with these you can move in absolute silence, and over rocks which, from their smoothness or inclination, would be impassable with boots. It is almost impossible to obliterate your spoor, as, even if you brush over your footprints, the practised eye of the native tracker will read your doings by other signs; still, it is a point not to be lost sight of for a minute when getting into position for scouting, and a little walking backwards, doubling on one’s tracks over rocky ground…”

Frank Sykes pays particular tribute to Grootboom’s services. “His services as a spy upon the positions and movements of the enemy have been invaluable. Possessing an intimate knowledge of the country and the customs and tactics of the natives, combined with courage and absolute self-reliance he was just the type pf man most adapted by nature and disposition for purposes of espionage.”

‘B-P’ praises Plumer for his surprise night attack on the amaNdebele at Ntaba zika Mambo; Sykes reveals that Grootboom left Bulawayo six days before Plumer’s column on foot. Once he arrived he lay concealed amongst some rocks not far from the stronghold and says: “At night I went into the mountains and saw every place where the enemy was. I saw the Matabele’s cattle in the kraal and went close up to their scherms where they were busy cooking. At one place I could plainly hear them talking. I went in from the east side of the hills and after seeing where all their fires were I went right round to the other side. Here I was very nearly caught. I was going through a narrow place between two large rocks and when I looked back I saw a fire just behind where I had come in and another one above me. I had to pass these again on my way out. From one spot on top of the rocks I could see something white against the fires and after a little time I made out the wheels of a wagon which they had there. Later on at night a great number of the Matabele started dancing and singing. I could not say how many there were, but they must have been a very large impi as their fires could be seen whichever way I looked. A lot of them who had been to consult the war doctor at Thabas Amamba returned to the Matoppos before Colonel Plumer’s Column arrived at Inyati.”

He had less respect for the hill-fighting tactics of the MRF in the Matobo: “The Column would march into the hills and have a fight and then at night go back to camp. This is no way to fight the Matabele. You must sleep in the hills after the battle and keep on following the enemy from one kopje to another and kill so many that you break his heart. But instead of that, you go back to camp; the Matabele thinks you have had enough of it and soon they collect together again and are more confident than ever. No, the white man doesn’t understand fighting among the rocks. They go out in the open and let the Matabele shoot and shoot and down they fall. I saw one man walk out from behind a rock and as he did so, a Matabele shot him through the head. But you don’t see Colonel Baking-Powder do that. If they want to shoot him, they must go after him, catch him out from where he hides. He knows better to stand up to be shot at.”

16 – 24 July fighting in the Matobo

Following their retreat from Ntaba zika Mambo many of the amaNdebele made their way to the Matobo Hills and Colonel Plumer decided to follow-up as MRF morale was high. ‘B-P’ was chosen as guide to the force of over 1,000 men but it soon became apparent that the Matobo represented a much greater obstacle. The amaNdebele were well armed with Martini-Henry rifles which deserting Matabeleland Native Police had taken with them although they lacked ammunition, and which ‘B-P’ says in letters to his brother George and Major C.B. Vyvyan, local prostitutes attempted to improve by charging ammunition for their services. the broken kopje country criss-crossed by numerous steep-sided valleys and streams gave the amaNdebele unlimited cover and made movement by regular forces extremely difficult.

“The rebels in the south have every reliance, and with reason, on the impregnability of their rock-strongholds; and their confidence is strengthened by their store of grain and cattle, which were being brought, long before the outbreak into the hills by the M’limo’s orders. Of arms and ammunition they have plenty, although the puzzle is to say from whence they come. But there they are Martinis, Lee-Metfords, Winchesters, besides the blunderbusses and elephant guns, which at the close quarters of this fighting make very deadly practice.”

The Chiefs and their followers when attacked simply retreated from their kopje strongholds into new defensive positions and sniped at their attackers from the shelter of the caves. By 24 July twenty MRF soldiers had been killed for no strategic gain and ‘B-P’’s intelligence gathering patrols into the Matobo achieved little in the way of useful information although they knew the approximate position of each of the chief’s.

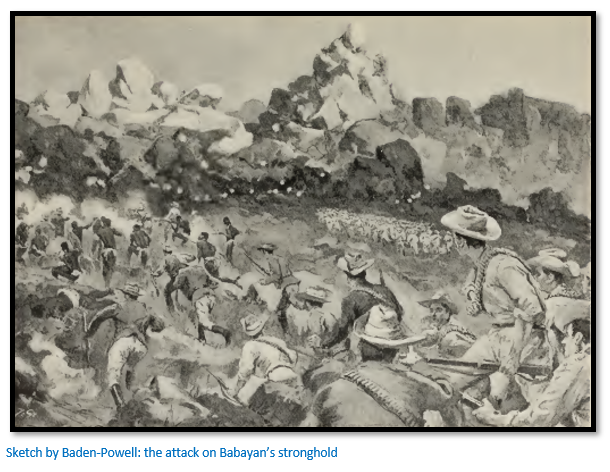

Early Matobo skirmishes – attack on Babayane

“19th July.—At last out time came. The order was given to the men in the morning, " Bake two days’ bread, and sleep all you can this afternoon." At what was usually our bedtime the whole column paraded without noise or trumpet call, and at 10.30 we moved off in the moonlight into the Matopos.

I was told off to guide the column, because I knew the way. I preferred to go alone in front of the column, for fear of having my attention distracted if anyone were with me, and of my thereby losing my bearings. And there was something of a weird and delightful feeling in mouthing along alone, with a dark, silent square of men and horses looming along behind one. Neither talking nor smoking was allowed-for the gleam of a match lighting a pipe shines a long way in the darkness. Except for the occasional cough of a man or snort of a horse, the column, nearly a thousand strong, moved in complete silence. Once a dog yelped with excitement after a buck started from its lair; the orders for the night expressly stated that no dog should go with the column, and accordingly this one was promptly caught and killed with an assegai.

Soon after midnight we were within a mile of the place; the square halted, and each man lay down to sleep just where he stood-and jolly cold it was. An hour before dawn we were up and on our way again, moving quietly onwards until we were close to the pass among the koppies which led into the enemy’s valley. Here, just as dawn was coming on, we left the ambulance and a reserve of men, together with our greatcoats and other impedimenta, and formed our column for attacking the stronghold.”

“…And so we advanced in the growing daylight into the broken, bushy valley, which was surrounded on every side by rough, rocky cliffs and koppies. Fresh paths and spoor showed that hundreds of rebels-must be living here, and at last I jumped with joy when I spotted one thin streak of smoke after another rising among the crags on the eastern side of the valley. My telescope soon showed that there was a large camp with numerous fires, and crowds of natives moving among them. These presently formed into one dense brown mass, with their assegai blades glinting sharply in the rays of the morning sun. We soon got the guns up to the front from the main body, and in a few minutes they were banging their shells with beautiful accuracy over the startled rebel camp...”

At this point the amaNdebele simply vacated their overnight position, leisurely crossed an open valley with a small stream and retired into an adjacent kopje. ‘B-P’ and a small group of native scouts occupied the kopje from which the amaNdebele had just quit.

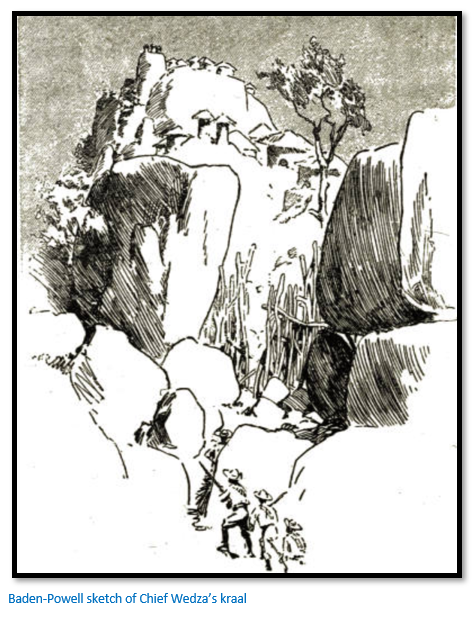

These, though recently occupied by hundreds of men, were now vacate, and one had an opportunity of seeing what a rebel strong hold was like from the inside; all the paths were blocked and barricaded with rocks and small trees; the whole place was honeycombed with caves to which all entrances, save one or two, were blocked with stones; among these loopholes were left, such as to enable the occupants to fire in almost any direction. Looking from these loopholes to the opposite side of the gorge, we could see the enemy close on us in large numbers, taking up their position in a similar stronghold…”

Then the skirmishing begins….

“…The Cape Boys, after making a long circle round through part of the stronghold, reassembled at this spot, and from it directed their further attacks on the different parts and it became the most convenient position for the machine guns, as they were able to play in every direction in turn from this point. For the systematic attack on the stronghold a portion of it is assigned to each company, and it is a pleasing sight to see the calm and ready way in which they set to work. They crowd into the narrow, bushy paths between the koppies, and then swarm out over the rocks from whence the firing comes, and very soon the row begins. A scattered shot here and there, and then a rattling volley; the boom of the elephant gun roaring dully from inside a cave is answered by the sharp crack of a Martini-Henry; the firing gradually wakes up on every side of us, the weird whisk of a bullet overhead is varied by the hum of a leaden coated stone, or the shriek of a pot-leg fired from a Matabele big bore gun; and when these noises threaten to become monotonous, they are suddenly enlivened up by the hurried energetic "tap, tap, tap" of the Maxims or the deafening "pong" of the Hotchkiss. As you approach the koppies, excitement seems to be in the air; they stand so still and harmless-looking, and yet you know that from several at least of those holes and crannies the enemy are watching you, with finger on trigger, waiting for a fair chance. But it is from the least expected quarter that a roar comes forth and a cloud of smoke and the dust flies up at your feet...”

The fighting begins to fizzle out as the amaNdebele fade away into the surrounding kopjes.

“…So in the meantime we did the best amateur work we could on the wounded men brought in. Of these there were six, all badly wounded; in addition to two more killed; and it is a pathetic comedy to watch the burly Royal Artillery sergeant transforming himself into a nurse for the occasion with a rough good-heartedness that does not stop to consider whether his patients are black or white.”

At the same time the plan was for Capt. Tyrie-Laing to simultaneously attack the amaNdebele on the Inugu Mountain, some fourteen kilometres to the westward – this went disastrously wrong as the force camped in a narrow valley and was attacked at dawn by the forces of Induna M’biza, Inkonkebella Holi and Dhliso from two sides [For a full account see the article Fort Umlugulu (previously Fort Nsezi, or Sugar-bush Camp) and the cemetery on the website www.zimfieldguide}

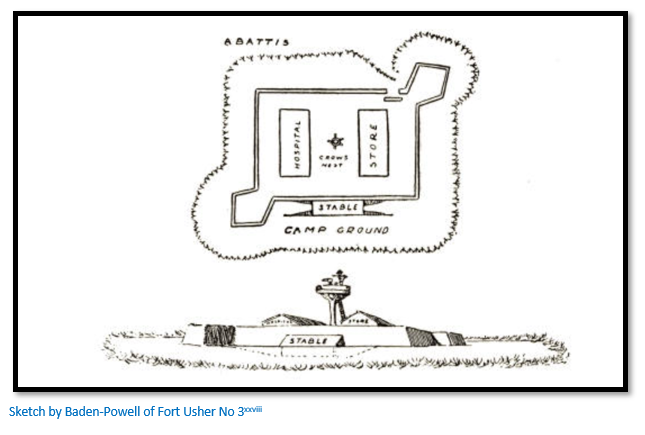

Construction of Fort Usher No 3

“22nd July - Forgot that I had been up all night and went for a bit of solitary exercise into the hills, to investigate some signs I had noted two days before of an impi camped in a new place. After a tedious bit of work, I found that they had decamped. I then went to the neighbourhood of Babayan’s stronghold, but could see no natives about there. Also, in accordance with the General’s instructions, I selected a position in which to build a fort to command this portion of the Matopos. I chose a point where there was open, fairly fiat ground for half a mile in every direction, close to a permanent stream - here there was a mighty thorn tree which would serve for a "crow’s-nest" or raised platform from which a look-out man could see well in every direction, and where a Maxim gun would command the whole of the ground round the fort. On return to camp, I drew out the design and plan of the proposed fort, and in the evening again went out there, taking with me a portion of Robertson’s Cape Boys to start work upon it the following morning. This fort was named Fort Usher, being near the site of one of Usher’s farms." [See the article Fort Usher under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Military operations continue

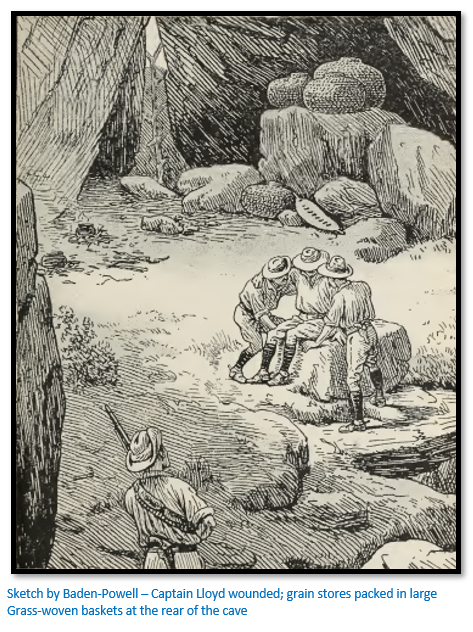

He carried out a reconnaissance of the deep Chabez gorge with Grootboom and next day during a small engagement was hit in the thigh by a stone covered in lead fired from a large-bore musket which fortunately was largely spent and left just a big bruise.

At Inyanda’s stronghold the kopje was first shelled and then: “we worked round through the bush to the rear of the mountain. Here were the caves which formed the grain stores of the rebels and after shelling these for a short time, we sent up parties to capture them. The enemy made no attempt to hold the place, but had retired over the back of the mountain, but one of them firing a parting shot wounded Captain Lloyd, our signalling officer, through the lower part of the thigh.”

At the spot where the Tuli road left the Matobo Brandt’s party had lost five killed and fifteen wounded with thirty horses killed the dead had been left on the ground, they halted and buried the dead. It was easy to follow the course of the fight from the wheels of the Maxim gun on which the wounded were carried and the bodies of the horses left in the veldt.

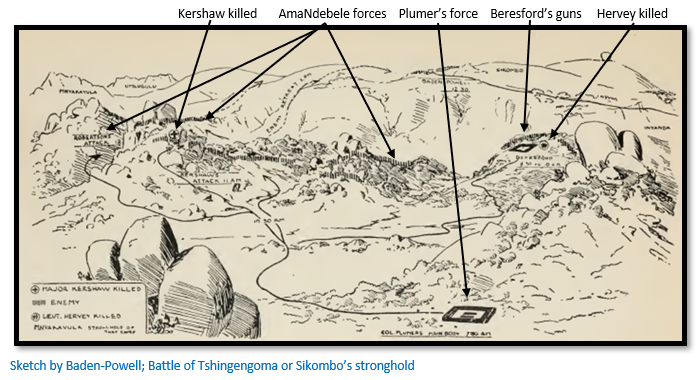

5 August – Battle of Tshingengoma or Sikombo’s stronghold

Sikhombo’s stronghold was attacked by the entire MRF. The attack was made at dawn in an attempt at surprise which meant the assault force needed careful mustering during the night and was led by ‘B-P’ from Fort Umlugulu to the position marked as Plumer’s main force.

Captain Beresford advanced at 6am to the position shown in order to shell the amaNdebele positions along the ridge line from the left of the sketch to the middle. The amaNdebele waited in ambush in a dip in the ground and rushed the guns; the day was saved by Captain Hoël Llewelyn who operated the Maxim gun single-handed and stopped a further charge; Tpr Holmes seeing Llewellyn unsupported ran to his assistance and was mortally wounded in the thigh and died four days later.

To the right of the seven-pounders Lieutenant Hervey was ordered to attack and as he stood on a rock waving his men forward was shot and mortally wounded. He was laid on a stretcher in the shelter of two large boulders, telling his men to continue on fighting. The engagement became more general, Capt. Jesser Coope with his scouts was unable to reach Beresford who had managed to signal that he was being heavily pressed, with Hervey severely wounded.

All the regiments of Chief’s Umlugulu and Sikombo were now engaged and the rocky ground favoured the amaNdebele who inflicted further heavy casualties. Major Kershaw led an attack at 11am to the left of the Tshingengoma Hill and was shot dead, Major Robertson’s Cape Volunteers attacked at 12am; Baden-Powell led an attack half an hour later and the AmaNdebele slowly began to retreat.

AmaNdebele losses were estimated at around 200; Plumer’s forces lost five killed and fifteen wounded, of which two subsequently died of wounds before the force moved back to their base camp at Fort Umlugulu. Two of the most popular officers were killed and the entire force left disheartened.

[This account is a summary - for details see the Battle of Tshingengoma or Sikombo’s stronghold on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Carrington’s lack of a strategic plan to defeat the amaNdebele

The inconclusive results of the actions in the Matobo Hills led Carrington to believe that he would only drive the amaNdebele out of their granite strongholds through a war of attrition by depriving them of ability to grow their crops and surrounding the Matobo Hills with a ring of forts. These would require an additional 2,500 Imperial troops in addition to those already in the field, the cost of which would be all be borne by the BSAC and which suggestion lost him the confidence of Rhodes.

Wikipedia states Carrington: “acquired fame by crushing the 1896 Matabele rebellion” but the reality is that all the military activities in those ‘bloody hills’ was left in the hands of Baden-Powell and Plumer and Oliver Ransford says Carrington spent much of his energy on learning to ride a bicycle around Bulawayo. The military also knew that time was not on their side – when the November rains came the problems of transport and supply would be exacerbated.

Peace negotiations with the amaNdebele

‘B-P’ played a part in the initial breakthrough in negotiations between the amaNdebele Chiefs and Rhodes. On 4 August ‘B-P’ had been scouting with Grootboom and Richardson, the Native Commissioner for the Matobo area and native scouts when they captured an old amaNdebele woman named Umzava whom they learnt was the niece of Mzilikazi, the father of Lobengula.

On 10 August they took her back to her old kraal which had been destroyed and “there we built her a new hut, hoisted a white flag, gave her two cows and some corn and an old woman prisoner to look after her. We told her all our conditions for peace and left her there.” The old woman passed on their message to the Chiefs in the hills. This led to Jan Grootboom and Johan Colenbrander having discussions with the Chiefs and to finally the first indaba in the Matobo.

Rhodes and the first Indaba

Rhodes joined Plumer and Carrington at their base at Fort Umlugulu (formerly Sugar Bush Camp) for a review of operations. The MRF were costing the BSAC £4,000 per day and now Carrington was saying additional troops were needed. Rhodes decided against the military advice he was getting and to negotiate directly with the amaNdebele Chiefs who were just a few miles away. [See the article The Matabele rising or First Umvukela Indaba site (Rhodes Indaba site) under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

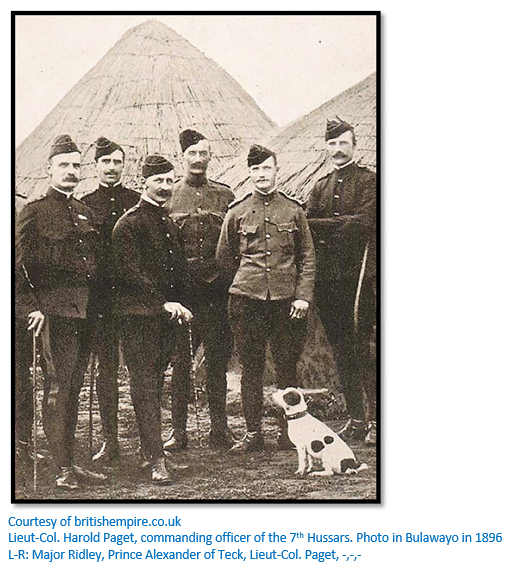

‘B-P’ commands a squadron of the 7th Hussars

‘B-P’ had hoped to join the peace negotiations but Carrington gave him command of the squadron of the 7th Hussars which was under Major Ridley with orders to complete the pacification in the region north of Gwelo, now Gweru. He takes three of Plumer’s men as escorts and rides the one hundred sixty kilometres via Inyati Mission and on the Old Hunter’s Road and finds the Hussars about forty miles to the east of the Shangani river.

The regiment of the 7th Hussars were sent to Pietermaritzburg, Natal on a routine posting when the Matabele Rebellion or Umvukela broke out at the end of March 1896. They had already handed over their horses to the 20th Hussars, so they took on the horses of the 3rd Dragoon Guards and three squadrons, under the command of Lt-Col Harold Paget, travelled down to Durban where they embarked on the 'Goth' for East London and then travelled by train to Mafeking where the Imperial troops were being assembled. Two squadrons remained in Pietermaritzburg.

Before ‘B-P’ joined the 7th Hussars after they had carried out a long patrol under Major Ridley in the Gwaai river area breaking up small parties of amaNdebele and accepting their surrender.

Following this phase the three squadrons of the regiment operated as mounted troops in the Gwelo area, then part of Matabeleland, but now in the Midlands Province, patrolling regularly with mounted infantry troops from the 2nd Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment (the 2nd, Yorks and Lancs) with ‘B-P’ regularly commanded the patrolling squadron.

Chief Uwini

The title of Jeal’s chapter on ‘B-P’s active service in Matabeleland is ‘Mistake in Matabeleland’ and although not explained, presumably refers to the capture, court-martial and execution by firing squad of Chief Uwini.

Ranger argues that after the death of King Lobengula in 1894 the leadership of the amaNdebele was disorganized, however the Mwari cult shrines at Matonjeni, Njelele, Mangwe an Ntaba zika Mambo (despite being Makalaka and not amaNdebele) managed to unite the amaNdebele and elements of Shona and Rozvi in an attack on the Europeans – the Matabele rebellion or Umvukela. After the battle at Ntaba zika Mambo, the spiritual leader Mkwati gathered his followers, mostly Makalaka and Maholi and scattered east into the Somabhula forest situated north and west of Gwelo. Both Mkwati and his father-in-law Chief Uwini were opposed to the chiefs in the Matobo talking peace with Rhodes and took active measures against any who collaborated with the Europeans.

‘B-P’ had no sooner arrived at his new posting when he was told Chief Uwini had been captured by his forces. “He was badly wounded in the shoulder, but, enraged at being a prisoner, he would allow nothing to be done for him; no sooner had the surgeon bandaged him than he tore the dressings off again. He was a fine, truculent-looking savage and boasted that he had always been able to hold his own against any enemies in this stronghold of his, but now that he was captured, he only wished to die.” ‘B-P’ asked the old chief to order his warriors to surrender, but he refused to cooperate, with ‘B-P’ conceding that: “he is a plucky and stubborn old villain.”

‘B-P’ was now faced with a dilemma. If he sent Chief Uwini back to Bulawayo, a five day journey, he would need to split his force and the chief’s followers would probably attempt to rescue him; but ‘B-P’ had neither the manpower nor facilities to take the chief on patrol with him as a prisoner. The other real possibility was to escort him to Gwelo and wait for a suitable time for the chief to be sent to Bulawayo. Carrington had given all his officers printed orders that they were to hand prisoners over to the Native Commissioner (Val Gielgud) in charge of the area for trials in the civil courts.

Furthermore Uwini’s defiant attitude ensured that his followers would not leave their strongholds and lay down their arms which left ‘B-P’ with a number of choices:

- The prospect that the troops (7th Hussars and the 2nd, Yorks and Lancs and Afrikander Corps) would need to enter the caves and winkle them out with the prospect of further casualties. They had lost five men killed and wounded in taking one kopje and kraal; there remained seven to be taken which were likely to be as strongly defended as the first.

- Uwini as the father-in-law of Mkwati a priest of the Mlimo had boasted that he was invulnerable to bullets. This claim had already been shown to be false outside Bulawayo and if it could be shown to be false yet again, Uwini’s followers might be induced to surrender.

- N.D. Fynn, Native Commissioner for the adjoining area had spoken to local Makalaka and Maholi people and was informed that Chief Uwini and Mkwati were the driving forces behind the rebellion locally and were using force and threats to any local chiefs who might be considering peace talks. Fynn had been told that a neighbouring chief and some of his tribe had been murdered for considering surrender of their firearms. In addition, Chief Uwini was considered the instigator of the Native Commissioner and European miners being killed in the area. These were likely those buried later at Fort Ingwenya [see the article Fort Ingwenya and cemetery under Midlands on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Based on the above, both Native Commissioners considered an example should be made of Chief Uwini which would most likely lead to peace in the region. ‘B-P’ asked his second-in-command Major Ridley of the 7th Hussars to be president of a court-martial. Ridley thought Uwini should be sent to Bulawayo for civil trial and asked ‘B-P’ if he had the authority to arrange a court-martial. ‘B-P’ said he had the authority as Carrington’s Chief Staff Officer which Ridley accepted, but did say he had been cautioned by Carrington not to shoot any prisoners.

The court-martial began on 13 September with Chief Uwini facing the following charges:

1. With being a rebel in armed resistance to the established authority

2. With sending his followers to attack ‘friendly’ tribes

3. With killing white miners in the Gwelo area The chief considered the first charge without merit as the Europeans were not the established authority and denied the last two charges. His defence was that the Imperial forces had been searching for grain in the area and either taking or destroying them and that he was defending his people, his property and his land. The military prosecutor made much of Chief Uwini firing at the Imperial forces searching the cave in order to prove that he was: “a rebel captured while in armed resistance to constituted authority.” ‘B-P’ changed his diary to agree with this argument writing first: “Uweena fired a second time at Halifax [the trooper who wounded him] and eventually gave himself up” before changing the entry to read: “Uweena fired a second time at Halifax, before he was at length cornered and captured.”

Chief Uwini did not deny firing on the troopers who entered the cave or refusing to lay down his firearm and said he had fired because he was sure they meant to kill him. ‘B-P’ writes: “When his kraal was taken by the troops Uwini had scrambled down into the labyrinth of caves which ran through the rocks on which the kraal was built. Trooper Halifax and another crawled in after him and followed him from one point to another of his refuge often firing and being fired at by him. After some hours of this game of hide-and-seek, Halifax had managed to wound the chief; then then followed him up with a lighted candle, tracking him by his blood spoor, until they finally cornered him in the cleft of the rocks from which he could not escape. He was so disabled by his wound as to be unable to fire on them and they made him a prisoner.”

Prosecution witnesses provided the following statements:

- Two troopers stated Chief Uwini had fired two shots at them

- Gielgud, the Native Commissioner stated that Chief Uwini had refused to allow his followers to surrender their firearms

- Two local people stated Chief Uwini had sent followers to kill the white miners

- A local person stated that Makalakas or Maholi known to be neutral or friendly to Europeans were killed

Chief Uwini declined to call witnesses. The court-martial found him guilty on all three charges, sentencing him to be shot and the verdict was confirmed by ‘B-P.’ At sunset, in the presence of ‘friendlies,’ local tribesmen and prisoners, Chief Uwini was shot by a firing squad of six troopers and the body taken by his wives for burial.

‘B-P’ expected: “I have great hopes that the moral effect of this will be particularly good among the rebels, as he was the head and centre of revolution in these parts and had come to be looked upon by them as a god.” Some weeks later Native Commissioner Fynn reported: “There can be no doubt that the death of Uwinya has had the very best results in ridding the country of the chief obstacle to a peaceful settlement” and this was confirmed by Native Commissioner Gielgud who reported: “many Maholi headmen surrendered during the next two or three days…These rapid results could not have been hoped for if the prisoner had been tried and executed at a distant time and place.”

After-effects of Chief Uwini’s execution

When Sir Hercules Robinson, recently created Baron Rosmead on 11 August 1896, the High Commissioner for Southern Africa heard the news of the execution he telegraphed Carrington: “I must point out that the ordinary courts of the country are still in existence and that martial law has not been proclaimed; the execution of Uwini appears prima facie illegal and I must therefore request that as soon as possible, without prejudice to the military operations, you will place Colonel Baden-Powell under open arrest and order a Court of Inquiry.”

This Carrington declined to do, viewing this as one more example of colonial office officials interfering with military operations with Southern Africa. When news reached the British newspapers, one of the first questions they asked was ‘why martial law had not been declared when rebellion had been underway for six months? Also, why was a civilian High Commissioner issuing instructions to a General in the field sixteen hundred kilometres away?’

Robinson’s action was consistent with his reaction to the execution of Chief Chingaira Makoni which has many parallels. Chief Makoni had been captured on 3 September and Major Watts’ original intention was that he should stand trial at a civil court in Umtali, now Mutare. Ross the Native Commissioner was opposed to this plan as he argued there was a real risk of Chief Chingaira Makoni escaping which would set the whole district into a blaze, and that the safety of Umtali itself might be endangered. In fact, Chief Chingaira Makoni’s son and two of his senior advisers did manage to escape and Watts’ plan for a trial in Umtali was rapidly discarded and a court-martial was quickly convened to try Chief Chingaira Makoni for “armed rebellion.”

In spite of Chief Chingaira Makoni’s assertion that he was innocent of being a rebel; his reply being: “it is all very well to call me a rebel, but the country belonged to me and my forefathers long before you came here” he was found guilty of armed rebellion and of having caused the murder of the three traders and was sentenced to be shot. A telegram was sent to Earl Grey by Major Watts to confirm the sentence, but as the nearest telegraph Office was at Umtali, this had to be taken by native runners. Native Commissioner Ross argued that any delay in waiting until permission was received would be prejudicial to security and the sentence was carried out on the morning of the 4th September. [See the article Fort Haynes and the fight at Chief Chingaira Makoni’s kraal under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Following the news of Chief Makoni’s execution Robinson had sent a telegram to Carrington to be distributed to all military officers entitled ‘Trial of Prisoners’ which prohibited prisoners’ trials by military courts. This order reached Bulawayo on 8 September, the day after he left for the Midlands so he may well have been unaware of it. The order declared that rebellion, or instigation of rebellion should not be treated as a violation of the customs of war and that men fighting for their country or the interests of their people should not be executed as war criminals.

A Court of Inquiry was held on the 30 October into Uwini’s death which cleared ‘B-P’ of any wrong-doing. In fact there is plenty of evidence that any ‘rebels’ who resisted having their grain confiscated or their kraals burnt down were shot by troopers and prisoners were executed. [See the article Contemporary criticism of the British South Africa Company (BSAC) from Henry Labouchère the editor of the journal Truth under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] Carrington wrote to ‘B-P’ saying he: “should not kill any unless they showed fight since they are on surrender” a rather meaningless statement.

The journal Truth founded and edited by Henry Labouchère had savaged ‘B-P’ for seeking to satisfy the “gold seeking scum of Bulawayo” by executing Chief Uwini; however in spite of this ‘B-P’ gained a reputation as an officer who understood war in Africa and got along with the colonials."

Continuing operations with the 7th Hussars in Matabeleland

Within a few hours of his execution many fighters came in with their arms and gave themselves up and large stores of grain were secured from Uwini’s stronghold and soon there were over a thousand prisoners and refugees in camp.

Following Chief Uwini’s execution ‘B-P’ continued with his squadron chasing after Mkwati, the spiritual messenger and Uwini’s son-in-law who left the Somabhula forest and travelled east to Chief Mashayamombe’s kraal at Hartley Hills near present-day Chegutu. Here he met the spirit medium Kaguvi and together they planned to unite all the Shona chiefs into a revived Rozvi State; however they are pursued north and Mkwati was killed by disillusioned Shona in late September / early October 1897. Despite the fruitless chase after Mkwati, ‘B-P’ describes how he loved the patrolling in the veld. “We all sleep in the open – and it is perfectly divine – fire at feet – saddle backed by a few bits of bush at your head to keep off the wind. Any amount of blankets and a nightcap – and a fine bright sky overhead. If the Prince of Wales went down on his bended knee I wouldn’t change with him.”

Out on patrol ‘B-P’ forbade his men from taking their boots off at night and would creep around the sleeping forms in their horse blankets rapping at the soles of their feet with his cane. One Hussar recalled: “we got cunning eventually and used to take off our boots and put them at the bottom of our blanket.”

New lessons in bush craft were learnt; finding water in dry riverbeds, how sudden movements of game often reveal the presence of humans and how the amaNdebele conceal themselves by merging with their background and keeping absolutely still.

They were looking for any groups of amaNdebele warriors; but most of their routine duties consisted of seizing any stocks of maize and any livestock they could round up on order to deprive the amaNdebele of food and kraals were burnt down– a ‘find and seize war of attrition’ and building secure forts from which the troops could deploy and which stored captured maize and cattle. [See the articles on (1) Fort Ingwenya and (2) Fort Que Que (now Kwekwe) and (3) Fort Gibbs under Midlands on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

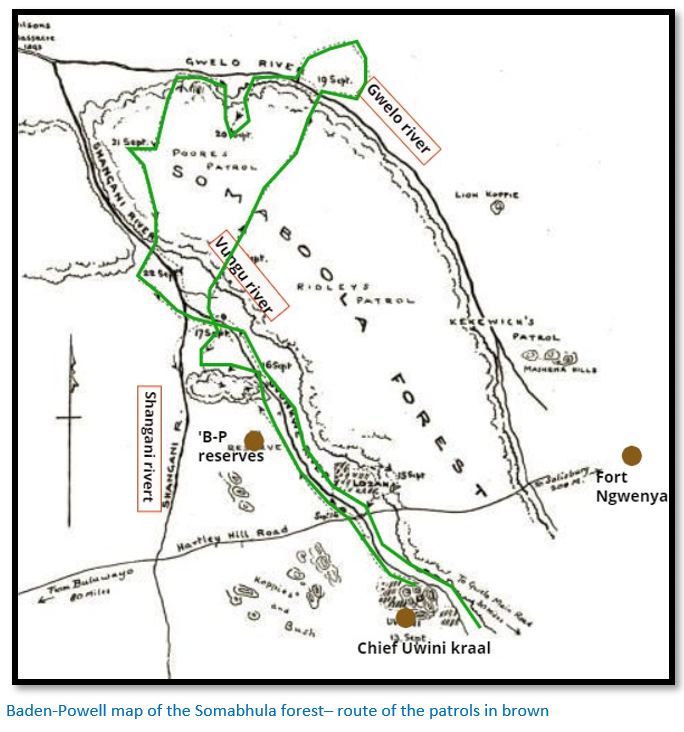

‘B-P’s patrol of the Somabhula Forest entailed one hundred and sixty men of the 7th Hussars and mounted infantry of the 2nd, Yorks and Lancs; two guns, an ambulance and four ox-wagons with the aim of driving the resistance from the Somabhula forest and facilitate the surrender of fighters.

14th – 19th September

Travelling north the patrol crossed the Vungu river and reached the deserted kraals and maize lands of Losan, but the recent spoor showed that the people had moved north into the forest. To move more quickly ‘B-P’ made the decision to split his force into three smaller patrols which would move north parallel to each other and leave the wagons in reserve. Captain Kekewich on the right following the Gwelo, now Gweru river north; Major Ridley to follow the Vungu river north; the third patrol under Captain Poore with ‘B-P’ to travel south down the Vungu river and then across to the Gwelo river to cut off any fighters who flee this way.

At the Old Hunters Road drift they found the remains of three Europeans before following fresh tracks from the Vungu river into a kraal which had just been abandoned where apparel and a necklace were left behind which identified the inhabitants as Mtini’s Regiment who were responsible for guarding Mkwati and who currently were preventing any fighters from surrendering. Knowing that Mkwati usually had his huts hidden in the vicinity, they searched but found nothing. [we know now he was at Mashayamombe’s kraal at Hartley Hills]

Following the spoor of those that have fled Mtini’s kraal they come suddenly into another kraal; “One fine big fellow in European clothes dashes out of a hut and makes off with a gun in his hand. I yell to him ‘Imana, andi Bulali’ (Stop, I am not going to kill you) But he does not stop and I try not to keep my promise, but unfortunately I have one of the new-fangled guns that I do not understand – slipperty-flip, click-clack and tick! – but there is no report; three times I cover him with my sights, aiming nice and low, just about the small of his back, but each time my gun refuses to go off. I have forgotten to turn on or off some little gadget or other and the man escapes.”

Patrolling continues with kraals being burnt; The routine is: 4:30am stand to arms, feed horses and boil coffee; 5:15am saddle up and march off. Patrol until 10am, then off-saddle and breakfast and rest from the heat of the day. 3:30pm saddle up and ride until 5:30pm; off-saddle and supper; then ride until a good position for the night is found. They lay the saddles down to form a square, each man sleeping with his head on the saddle and the horses inside the square tied to two lines.

Now they turn east towards the Gwelo river; they interrogate a woman who tells them the nearby kraal forms part of Mtini’s impi; they capture numbers of people who appear relieved at their new status and tell ‘B-P’ they are tired of the fighting but have been prevented from surrendering. Nearby a European farm has been ransacked and they find and bury the farmer’s remains.

Conditions were difficult: “The Gwelo river itself is not a pleasing one; it is chiefly a bed of hard, black mud, lying between black, shiny rocks, with a few pools here and there, with an unpleasant smell about it. The sun too is now very powerful and we are all feeling tired…”

“…our horses gave out from want of food and overwork, although the men cared for them in every way, walking in their holey boots and sharing with them their small ration of bread.”

Our menu: “weak tea…no sugar…a little bread…Irish stew (consisting of a slab of horse boiled in muddy water with a pinch of rice and half a pinch of pea-flour)

They are still following the Gwelo river from which they hope to strike the Shangani river: “Every man was now walking and either leading or driving his horse and as we formed a long single string in the narrow path, our progress was extremely slow…”

21st September

Gielgud and ‘B-P’ decide to leave the path and strike off to one side where the ground appears to slope downwards. “It was heart-breaking work, every rise seemed to promise a valley on the other side, but we only topped it to find an ordinary dry baked grass vlei behind.”

“Then I saw two pigeons fly up from behind a rock a short distance from me and going there, I found a little pool of water…An hour later we had got the party off-saddled there, watered and camped for the day and here I am under my blanket shelter, scorching hot day, flies innumerable stopping all our efforts to sleep and the prospect of another night march before us which we sincerely hope will bring us out of this beastly forest to the river.

We held on steadily to the south and eastward until long after dark and again a brilliant moon helped us on our way. In fact we do far more marching by night than by daytime. At last a halt was called because two more horses had given out and we had to transfer their saddles to other horses, which in some cases were already carrying two or three saddles on their backs, for we may as well try to save what Government property we can.

I know you will ask, what is horseflesh like? Well, it is not so bad when you have got accustomed to it and especially if you have a little salt, mustard, vegetables, etc. to go with it and also if you do not happen to know the deceased personally. None of these conditions were present in our case. It is one thing to say, ‘I’ll trouble you to pass the horse, please’ but quite another to say, ‘give me another chunk of D15.’”

In the evening they were delighted to meet their relief party which had been sent out under De Moleyns to meet them. “Here were camp fires ready lit, bully-beef, sugar, flour, cocoa, laid out already for issue and nosebags, stuffed with mealies, ready for the horses. It was a goodly sight and what a meal we all made. The luxury of bully-beef!”

1st October

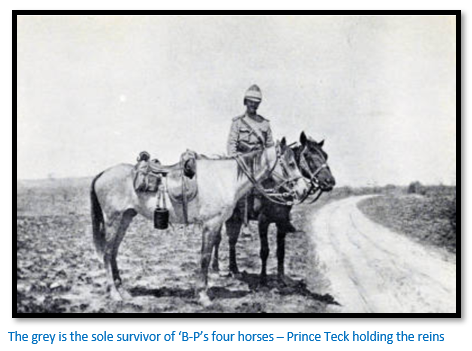

The whole force then re-grouped on the Old Hunter’s Road and headed for Inyati as an impi was reported to be gathering the area. On arrival at Inyati there was a letter from General Carrington saying the impi wished to surrender and that the war was practically over in Matabeleland and that ‘B-P’ is to commence operation against Chief Wedza. The best of the Hussar’s and mounted infantry horses are picked, one hundred and fifteen in all, with a 7-pounder and two Maxims under Captain Boggie and three weeks’ provisions for the one hundred and sixteen kilometre journey to the south-east. Prince Alexander of Teck is the Staff Officer, in place of De Moleyns, who is organising the new police force in Mashonaland.

2nd October

They follow the Bulawayo – Belingwe road going through the Insiza Hills: “Our night outspan is on the top of a hill among the burnt ruins of Stevenson’s store; it does make one feel a little badly disposed towards our black brothers when one sees a comfortable home like this wantonly destroyed, its little household knickknacks scattered, broken and burnt about the veldt. It was near one such homestead as this that I found a poor little white chap of three years old, with his head battered, as these savages are fond of doing. After burying him, I kept one of his little shoes as a keepsake.”

9th October