To what extent did slavery exist in Mozambique, Tanzania and Zimbabwe?

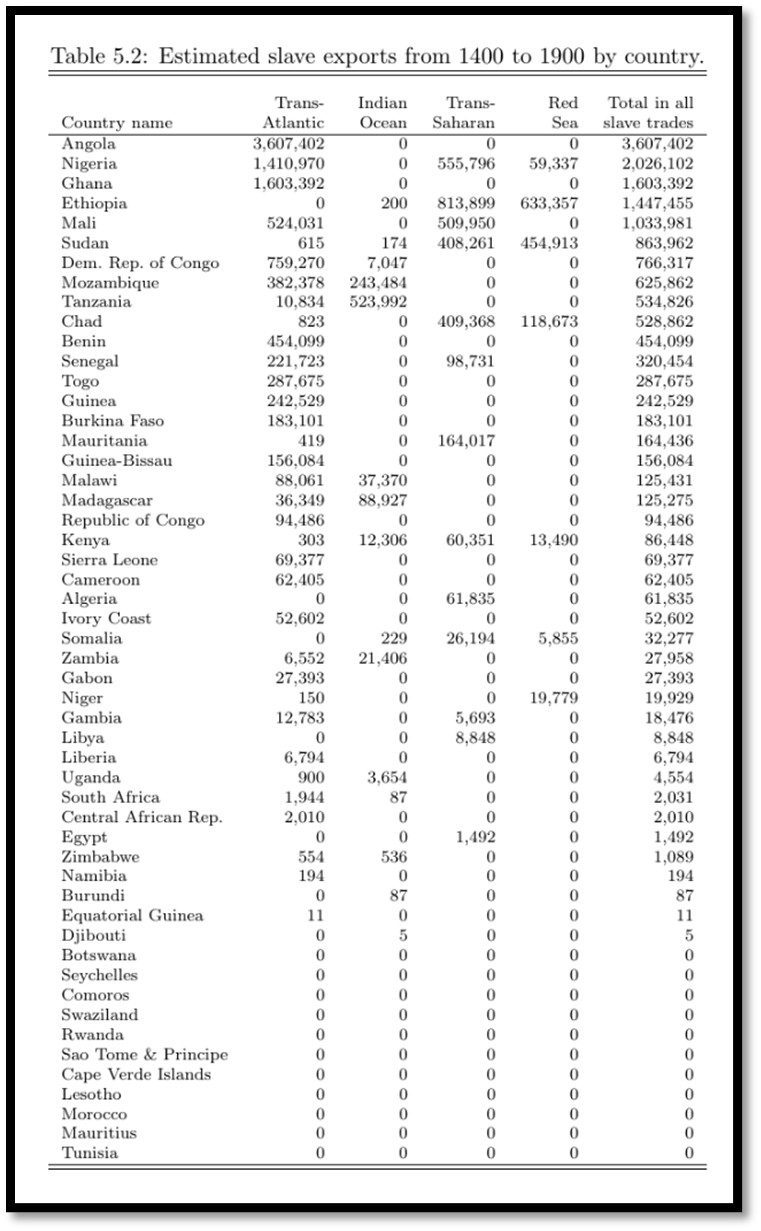

I have been told that slavery did not exist in the region of Mozambique, Tanzania and Zimbabwe; this article sets out to explore this question. However, to give the reader an initial broad perspective: Nathan Nunn[1] estimates that the numbers of men, women and children enslaved for each of the above countries were 625,862; 534,826; 1,089 respectively.[2]

Probably the oldest slave trade networks from Africa were the trans-Saharan, Red Sea,[3] and Indian Ocean slave trades, all dating back to at least 800 AD. Slaves were being sourced south of the Saharan desert, inland of the Red Sea, and inland of the coast of east Africa and shipped to Northern Africa and the Middle East where there was demand for them as soldiers, domestic servants and manual and craft workers.

However, much larger in scale was the trans-Atlantic slave trade; beginning in the 15th century slaves were shipped from West Africa, West Central Africa, and Eastern Africa to the European colonies in the New World. Although it covered a shorter period than the previous slave trades, it was many times larger and probably at least 10.5 million men, women and children were taken from Africa as slaves. Greatest numbers came from the Slave Coast (Togo, Benin and Nigeria) West Central Africa (Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola) and the Gold Coast (Ghana)

This article does not cover conditions of slavery after the beginning of the 20th century; nor is the topic of forced labour, forced marriage, migrant workers or compulsory prison labour included.[4] There is little information on the extent of slavery in present-day Zimbabwe. It surely existed, but statistically according to Nunn barely registers as even a fraction of the combined slave trade. See Appendix 1) ZANU-PF government owned newspapers such as The Patriot and The Herald are loud in their rhetoric but fail to back up the sensational headlines with anything of substance.

A broader look at the extent and some details of the slave trade

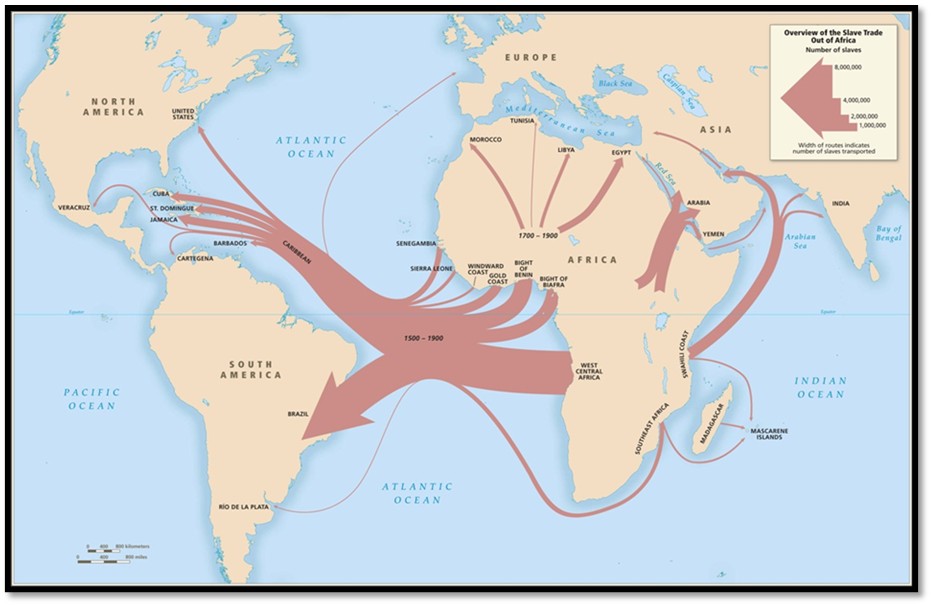

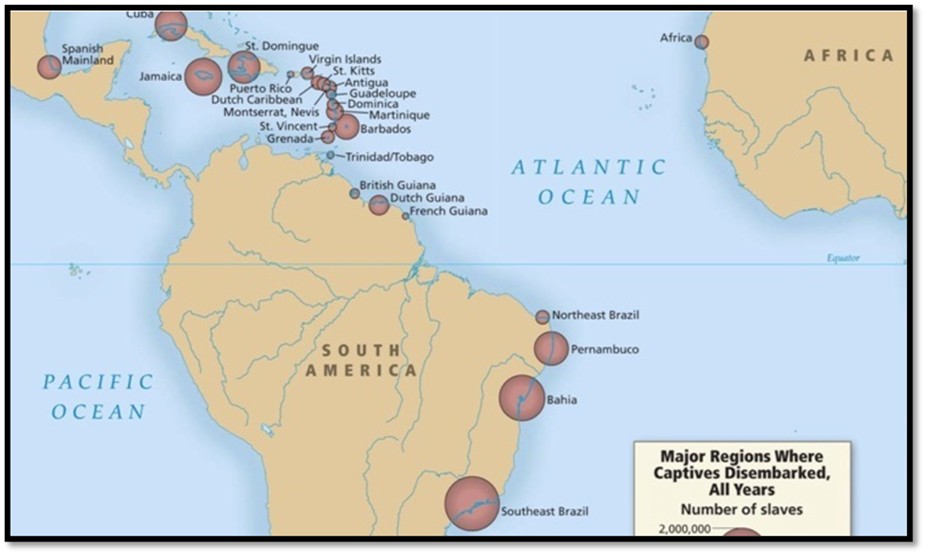

The map of the Atlantic Ocean below shows the slave routes from their sources in Africa to their various destinations in South America, the Caribbean and North America for the period covering 1525 to 1866. The authors state that records were kept for trans-Atlantic movements, but there are almost none for the trans-Saharan, Red Sea and Persian Gulf routes, but they estimate that, “about the same number of captives crossed the Atlantic as left Africa by all other routes combined.”[5]

Slave Voyages Graphic[6]: slave traffic from Africa to various destinations

The above graphic highlights the direction and volume of the slave trade between their sources and destinations, namely from Africa principally to the Spanish colonies, Portuguese Brazil and Uruguay and the sugar plantations in the Caribbean. Clearly Portuguese slave ships would mostly transport their slaves to Brazil and Uruguay, but it was also the case that captives from any of the major regions of Africa could disembark in almost any of the major regions of the Americas. Even captives leaving Mozambique or Tanzania in Southeast Africa, the region most remote from the Americas, could disembark in mainland North America, as well as the Caribbean and South America. The authors caution the data in this map is based on estimates of the total slave trade rather than documented vessel departures and arrivals.

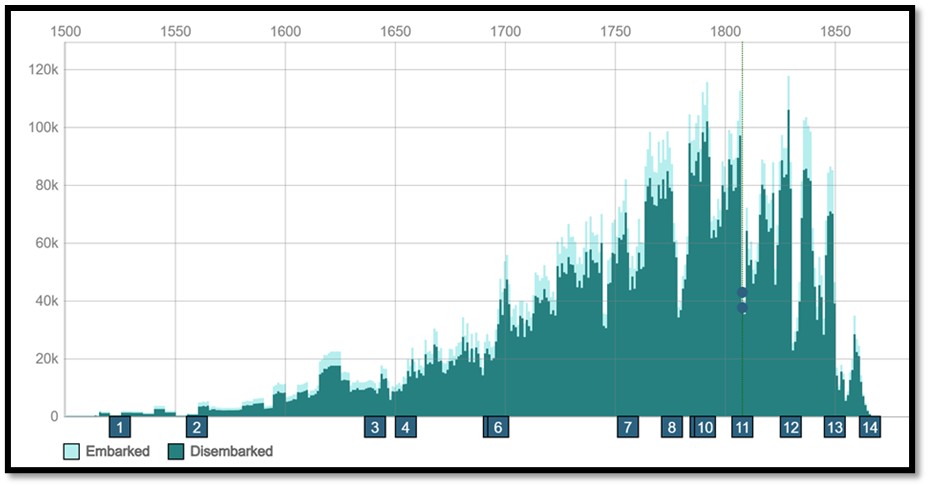

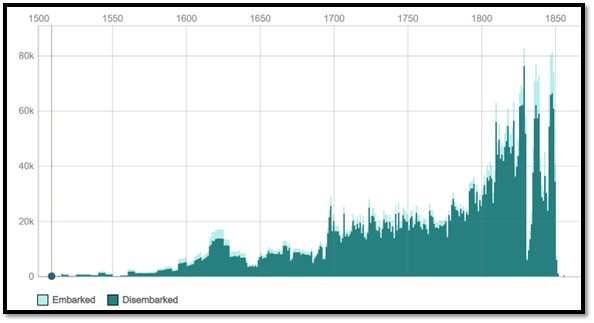

Slave Voyages Graphic: Numbers of slaves estimated to have been shipped trans-Atlantic from 1501 to 1875

The authors explain the significance of the various historical events:

The flags of the various slave ships used in the transport of the slaves to their destinations include Denmark, France, Great Britain, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and the United States of America.

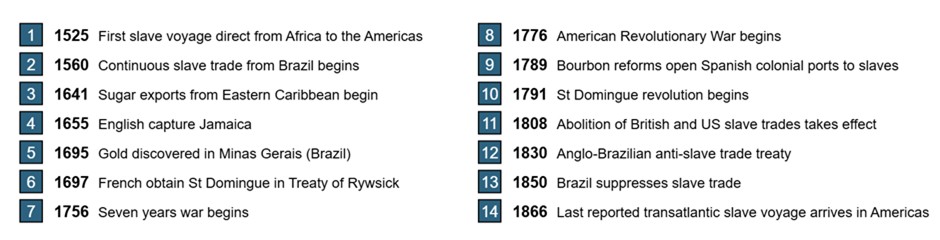

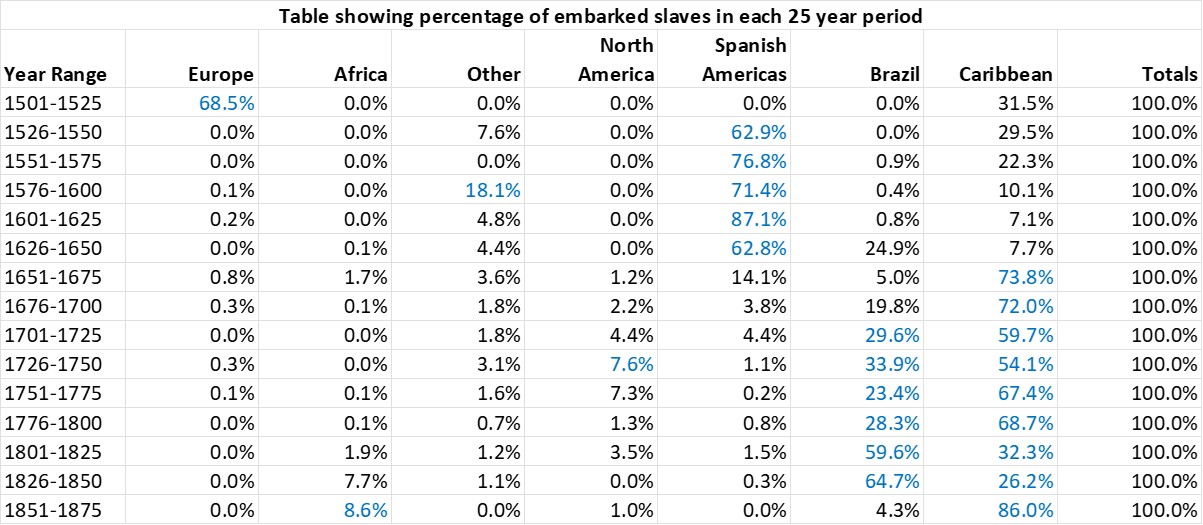

Table showing the number of embarked slaves and their destinations

Source: Slave Voyages

Source: Slave Voyages; (peak years highlighted in blue)

Slave Voyages Graphic: Destinations trans-Atlantic where slaves are estimated to have been shipped from 1501 to 1875

The trans-Atlantic slave trade being banned did not end slavery, particularly in the colonies

The transatlantic slave trade was officially prohibited in 1807 in Britain and in 1808 in the United States, but it did not signify an end to slavery as slaves still remained under the control of their owners for many more years and the laws were disobeyed in the colonies.[7]

However, slave traders were forced to search for new slave markets and Mozambique became an important source and destination for slaves.

Portugal and the slave trade

Portugal’s colonies at Angola and Mozambique had a significant part in the global slave trade in the 18th and 19th centuries. Hundreds of thousands of Angolans and Mozambicans were sold as slaves in the South Atlantic trade, in the Arab trade in the Indian Ocean and in the French trade to Indian Ocean Islands.

More than 400,000 East Africans, shackled in ships’ holds, are estimated to have made the four-month, 7,000-mile journey from Mozambique to the sugar plantations of Brazil between 1800 and 1865.[8]

Slave Voyages Graphic: Portuguese slaves shipped from Angola and Mozambique to Brazil and Uruguay

As the above graphic illustrates the vast majority of African slaves were destined for Brazil and Uruguay. They were shipped from Angola, but some also came from Mozambique with the vast majority being shipped between 1800 and 1850.

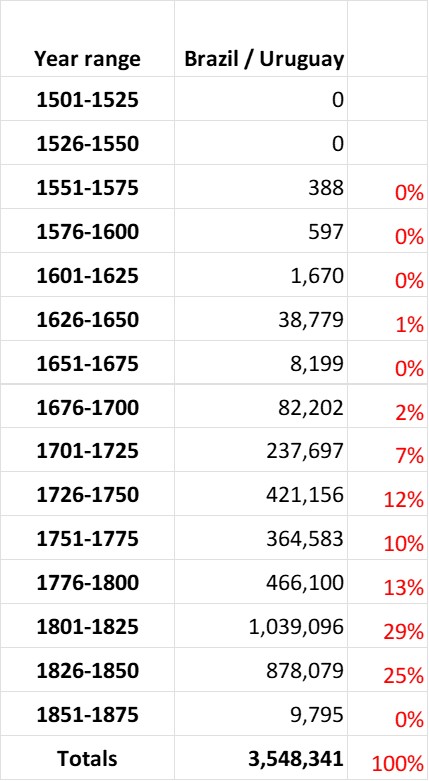

Slaves Voyages Graphic : showing slave numbers shipped to Brazil and Uruguay

Slaves transported from Angola and Mozambique to Brazil and Uruguay in each 25-year period

The plantations of Brazil and Uruguay were the destination of the second highest number of slaves shipped from Africa representing an estimated 35% of the total number. The table above shows the highest 25 year-period for shipping slaves was 1801-1825 followed by 1826-1850.

The rise in slave trading in Mozambique

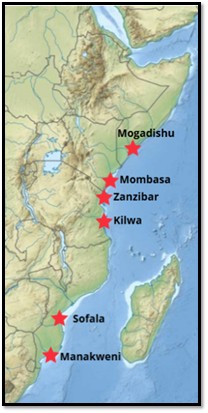

Long before the Portuguese arrived at Sofala,[9] an important commercial network of Swahili settlements existed on the Mozambique coast from Bazaruto up the Swahili coast. From the coastal settlements a network of paths spread inland into the African interior usually following geographical features such as rivers and facilitated by groups of traders who relied on inter-personal relationships and kinship ties for support. African trade goods, including gold, were exported from these ports to the northern Swahili towns and through them to the Indian Ocean where they were exchanged for cotton, beads, spices and other Indian goods. This trade underpinned the prosperity of the northern coastal settlements and ports such as Kilwa,[10] Sofala, Quelimane, the Querimba Islands, Angoche and Mozambique Island.

Flowing out of the interior of Southern Africa and present-day Zimbabwe, gold had been traditionally traded out of the port of Sofala, located in today’s Mozambique, since the 10th Century. Kilwa extended its influence to control Sofala, but also the Bazaruto Archipelago as its southern outpost until the entire east African gold trade came under Kilwan control. This regional trade network between the Mutapa State in the interior and the east coast of Africa, India and Asia brought prosperity to the small southern ports, Sofala and Mozambique Island long before the Portuguese arrival. See the article The Mutapa (Mwenemutapa, Monomotapa) State in its heyday c.1480 – c.1623 under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Most trade was seaborne

Navigation up and down the east African coast depended on the monsoon winds and trade goods were moved by small dhows with most of the settlements having sandy beaches up which the dhows would land. They traded primarily for gold, but also carried exotic skins, turtle shell, ivory, mangrove poles and slaves. There are few natural harbours suitable for the ocean-going Portuguese naus that needed to be large enough to be stable in heavy seas and to carry a sizeable cargo and the provisions needed for very long voyages.[11]

When the Portuguese under Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1498 and sailed up the east coast of Africa they knew almost nothing about the region and the Indian Ocean commercial network. However their plan was to dominate the gold trade with their superior sea power.

Graphic showing main Swahili trade centres

At the time the Portuguese arrived at Sofala in 1505 the gold traffic from the interior was controlled by Muslim traders under the rule of Sheik Isuf who had just declared his independence from the Kilwa Sultanate. Alcáçova[12] states in 1506 that Sheik Isuf’s community numbered about 800 and lived side by side with the local native community.

The Portuguese goal was a monopoly of the spice trade from Asia

The 1498 voyage of Vasca da Gama around the Cape of Good Hope brought the Portuguese into the Indian Ocean and challenged the old Swahili and Omani trade monopoly. For the Portuguese dominating the spice trade between the Far East and Europe was the ultimate goal and breaking the monopoly of the silk road and Venice’s monopolistic hold on it. Their interest in the Mutapa State’s gold mines was simply as a source of revenue to purchase spices – India would not accept the commodities that Europe had to offer – they wanted gold bullion. See the article Why did Portugal establish bases on the East African Coast, now Mozambique in the early sixteenth Century? under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Dominating the east coast of Africa was not the Portuguese Crown’s final objective but subduing the power of the Swahili traders ‘the Moors’ and forcing them to pay taxes and fees (cartazes) in order to trade were important steps to establish a trading monopoly.

From their little knowledge the Portuguese form an Africa strategy

Based on their knowledge of the above trade and vague information of trade at Sofala of gold mined in the African interior they made their plans. This was to impose their rule in the region using the superior firepower on their naus so that they controlled the Indian Ocean and through Sofala – the focal point of the gold trade – to gain access to the gold mines of the interior and to oust the Muslims from their position of power.

The Portuguese believed their plan to control the commercial network in the Indian Ocean required establishing a permanent military presence at Sofala and the Island of Mozambique[13] with sufficient military resources to make the Kilwa Sultanate subordinate to their rule as well as establishing strategic alliances with local rulers such as Malindi. Port cities, such as Zanzibar, which did not welcome the Portuguese presence would be forced to submit and pay tribute.

The Portuguese attempt to dominate the gold trade

By the 1530s small numbers of Portuguese had established garrisons and trading posts at Sena and Tete on the Zambesi river and tried to gain exclusive control over the gold trade by establishing trading posts[14] (feiras) within the region of the Mutapa Empire and its vassals. See the article The Portuguese Feiras and trading settlements of the 16th – 17th century on the Northern Mashonaland Plateau and Manicaland under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

They managed to dominate the coastal trade between their arrival in 1505 and 1700 but failed in their attempt to control the gold trade. See the article How Portuguese trade developed in Mozambique during the 16th/17th Centuries prior to the establishment of the feiras in the Mutapa State under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

There was much resistance from Swahili traders; in 1561 Gonçalo da Silveira, leader of the first Jesuit mission to the Mutapa Empire, was killed after converting the King to christianity at the urging of the Muslims who feared his influence. See the article The 1561 martyrdom of Dom Gonçalo da Silveira, S.J. under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

In response, the Portuguese sent a large military force in 1569 to punish the Monomotapa and to conquer the northern Mashonaland plateau and gold-mining region. Most of the soldiers including their commander Francisco Barreto died of disease and malnutrition and almost nothing was achieved beyond a temporary occupation of the Zambezi Valley with almost no Portuguese authority beyond Tete and Sena. See the article Francisco Barreto’s military expedition up the Zambesi river in 1569 to conquer the gold mines of Mwenemutapa (Monomotapa) under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

See also the article Vasco Fernandes Homem and the search for the Mutapa state’s fabled gold mines 1574-5 under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Portuguese policy led to general unsettlement in the Mutapa Empire and gave rise to a chronic state of native warfare. The Portuguese were always sending out punitive expeditions, and to such an extent that in 1634 De Rezende wrote, "Those [natives] in the interior are in revolt against us, and as we have often chastised them in war, they cherish a hatred of us" and he further explained the "petty commerce" by stating, "The negroes of these parts resent the punishments we have inflicted upon them." [15]

By the end of the 16th century, much of Mozambique was outside Portuguese authority and civil war and strife in Monomotapa led to the loss of their last trading post (feira) in 1693 to a Rozwi invasion force led by Changamire Dombo.

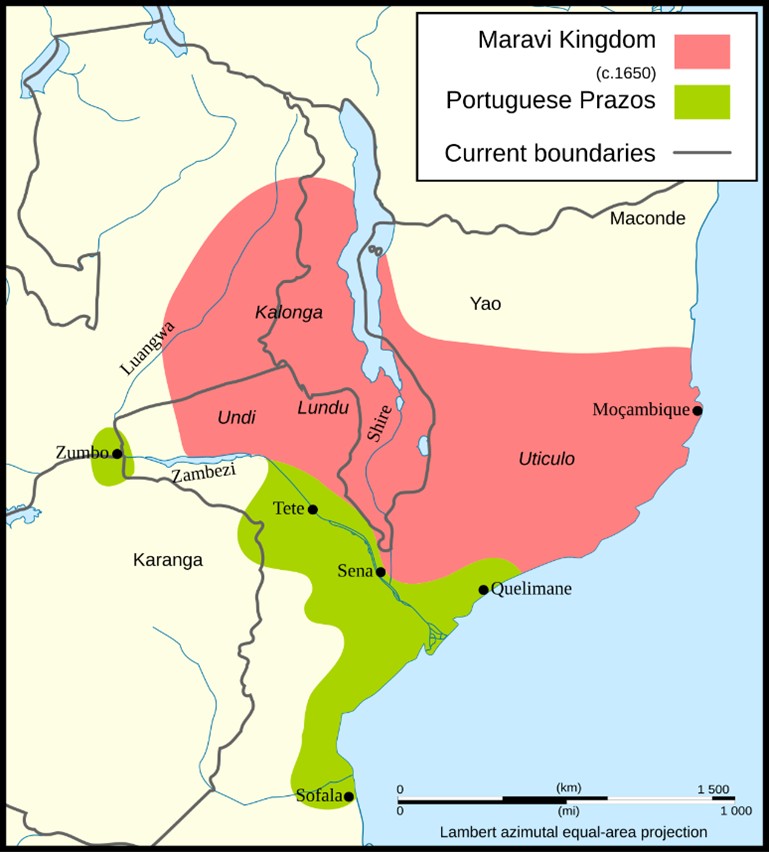

North of the Zambesi river Maravi chiefs had established the powerful chiefdoms of Karonga, Undi, and Lundu and similarly resisted the Portuguese.

As Portugal’s hold begins to weaken the gold trade declines in favour of the slave and ivory trade

The general unsettlement of the country from 1505 to 1760, as described earlier, accounts very largely for the short lives of these markets, but the introduction of the slave trade in 1645, as dealt with later, finally put an end to the Portuguese trade in gold.

“In 1645 we find the Portuguese trade in slaves to Brazil and India from Mozambique paid far better, on their own admission, than either gold-trading or goldmining, while the records show…that the ivory trade at Sofala was more profitable than the trade in gold! We read, too, that the Portuguese slave trade destroyed the confidence of the natives in the Portuguese and ruined the trade in gold.”[16]

“The slave trade was at times a Government monopoly, and at other times it was "farmed." Licences to trade in slaves were sold at a high figure, and there was a brisk demand for them, which returned a revenue, as the records state, exceeding that derived from the gold trade, beside which the records show that the slave trade itself was far more remunerative than the slow business of bartering loincloths and glass beads for gold dust. But gold-trading could not be carried on simultaneously with the slave trade. With the introduction of the slave trade in 1645 commerce in gold ceased.”[17]

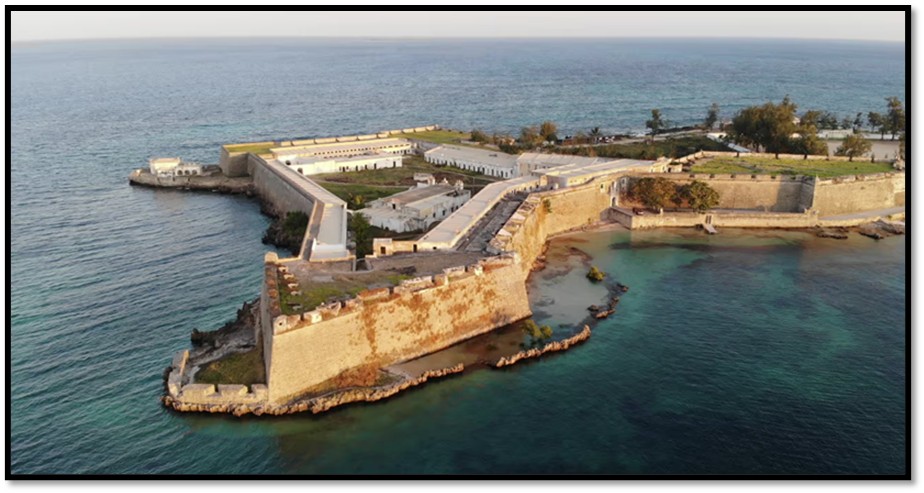

The gold trade appears to have been in decline as far back as the Portuguese arrival at Sofala in 1505. In addition, Sofala was ill-suited as a port, with a shallow sandbar at the entrance and a malaria problem; their trading activities soon moved to their base at Mozambique Island[18] that developed as a way station on the route up the east coast and to India.

In 1696-8 Fort Jesus at Mombasa was subjected to a two-year siege by the Omani Arabs, led by Saif bin Sultan. The Arab seizure of the fort[19] marked the ending of Portuguese dominance on the east coast. During the 18th and 19th centuries the Mazrui and Omani Arabs reclaimed much of the Indian Ocean trade, forcing the Portuguese to retreat south. The Sultans of Oman relocated to Zanzibar in 1840.[20]

Fort of São Sebastião, Mozambique Island, a 16th-century fortification used to trade and detain enslaved people

Despite their eviction from the northern Mashonaland plateau by 1693, the Portuguese had gradually extended a weak authority up the Zambezi Valley through the prazos, and to some extent, north and south along the Mozambican coast. A trading post was established at Inhambane in 1727, and in 1781 at Delagoa Bay (present-day Maputo) However as Malyn Newitt writes, “in central Mozambique a kaleidoscope of polities, some dominated by Afro-Portuguese or Indo-Portuguese warlords supported themselves through attracting clients or purchasing slaves to form their armies or to hunt for ivory.”[21]

These conditions led to the slave and ivory trade beginning to dominate over the diminishing gold trade and by the late 1700’s the trade in slaves, which had existed at a low level prior to the European arrival, began to flourish under both African, Indian[22] and European traders as demand grew.

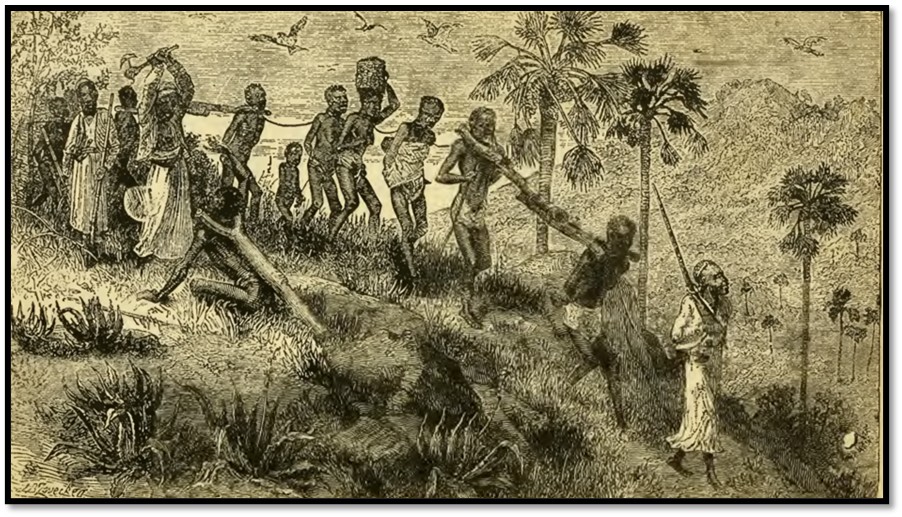

From the Portuguese accounts it appears that the most common way that slaves were taken was in wars and village raiding. Men, women and children were not only taken through conflict between communities, during raids and wars, but they were also taken in large numbers as a result of conflict within communities, where individuals were kidnapped or sold into slavery by acquaintances, friends, or even family. An environment of insecurity arose from increased conflict between communities and individuals acquired weapons from Europeans to defend themselves.

The slaves were often obtained through local kidnappings and violence and the slave traders probably also played a role in promoting internal conflict. They formed alliances with established rulers and warlords inside villages and states in order to obtain slaves.

The growth and decline of the Prazos

Wikipedia states, “slavery in Mozambique pre-dated European contact. African rulers and chiefs dealt in enslaved people, first with Arab Muslim traders, who sent the enslaved to Middle East Asia cities and plantations, and later with Portuguese and other European traders. In a continuation of the trade, slaves were supplied by warring local African rulers, who raided enemy tribes and sold their captives to the prazeiros. The authority of the prazeiros was exercised and upheld amongst the local population by armies of these enslaved men, whose members became known as chikunda.”[23]

Prazos were large estates (land grants) often run on feudal-like conditions, that were leased to Portuguese and Goan traders in the Zambezi river valley from the 16th to 18th centuries in an attempt to legitimise Portuguese settlement and colonization. The prazo-holders recruited large African private armies known as Chikunda (or Chicunda) and became virtually independent fiefdoms, though they nominally owed allegiance to the Portuguese crown.

However, in the 1820-30’s drought, locust swarms and smallpox ravaged the Zambesi Valley and surrounding areas leaving the prazos to become, “complete deserts through famine and the pestiferous smallpox which has reduced the villages of the chikunda and the colonos to mere depositories of corpses.” Newitt writes, “The social and economic structure of the processors was destroyed as agricultural production and trade ceased and the destitute inhabitants abandoned their villages… Their place was taken by a few powerful families which rented the vacant processors, recruited slave armies and from fortified strongholds[24] began to participate in the growing trade in slaves.”[25]

The slave trade existed before Europeans arrived but expanded after their arrival

In the 18th Century slaves become an increasingly important part of Mozambique’s overall export trade from the east African coast. The slave market developed with the prazo-holders selling slaves from Zumbo, Tete and Sena to merchants at Quelimane. Yao traders developed slave networks from the Maravi[26] area around the tip of Lake Malawi to Kilwa and Mozambique Island. Tsonga ivory traders developed routes from the Transvaal region of South Africa and from the Zimbabwe plateau to coastal entrepôts at Imhabane and Maputo.

Between 1800-80 probably no other form of trading, including ivory and gold, generated as much profit as slave trading. Newitt states, “the demand in America for slaves from eastern Africa rose steeply, until around 1830, exports from eastern Africa were almost as great as those from western Africa. The background to this was the gradual restriction of the slave trade in West Africa. Diplomatic pressure backed by Royal Navy patrols, had led to the trade being officially abandoned by all countries, except the Portuguese…Mozambique now became the major supplier of slaves for Brazil and Cuba. Between 1800 and 1850, Brazil imported around 2.46 million slaves, most of whom came from Portuguese ports in eastern Africa, from Ibo in the north to Delagoa Bay in the south, with Quelimane briefly becoming the most important centre of the trade after 1815.

Wikipedia: The Maravi Kingdom at its greatest extent in the 17th century.

During the 19th century, Mozambicans were sold as slaves in the Portuguese and Brazilian South Atlantic trade, the Arab trade from the Swahili coast, and the French trade to the sugar-producing islands of the Indian Ocean and Madagascar. Although the trade in slaves declined as a result of the mid-19th century slave-trade agreements between Portugal and Britain, clandestine trade - particularly from central and northern Mozambique - continued into the 20th century.

The supply of slaves was facilitated by conflict when tribal raiding groups invaded southern and central Mozambique completely dislocating the lives of local people and causing much suffering. They were the Jere underZwangendaba who continued north across the Zambezi and the Ndwandwe (both later known as Ngoni) under Shosangane who crossed the Limpopo into southern Mozambique, eventually becoming the Gaza state. Succession struggles caused further suffering.

Administration of Mozambique shifts from the Crown to Chartered Companies

By the early 20th century much of the administration of Mozambique had shifted from the colonial authorities to private chartered companies, including the Mozambique Company, the Zambezia Company and the Niassa Company. Although slavery was legally abolished in Mozambique the Chartered companies enacted a forced labour policy and supplied cheap, often forced, African labour to mines and sugar plantations.[27]

Eric Allina has done valuable research[28] in this area to document “how the Portuguese empire ushered in a vast forced labour system.” The Mozambique Company ruled over the area from the Rio Sabi to the Zambesi river, an area larger than Portugal, where forced labour was established until 1961. He reveals that Portuguese colonialism was not weak, “Africans who lived under colonial rule, whether in Mozambique, Malawi, or Mali, were unlikely to view the brutality of their colonial masters as an expression of weakness” and secondly, that the “history of colonial rule does not support a conclusion that institutionalized violence to extract African labour was a peculiarly Portuguese approach.”

Personal accounts of slave raiders within the interior of Africa

David Livingstone recorded numerous encounters with slavers and their captives.

“Once, it is said, a party of twelve, who had been slaves in their own country —Cunda or Conda, of which Kazembe is chief, or general —were loaded with large, heavy yokes, which were forked trees, about three inches in diameter and seven or eight feet long, the neck inserted in the fork and an iron bar driven across one end of the fork to the other and riveted to the other end. Tied at night to a tree or ceiling of the hut, and the neck being in the fork and the slave held off from unloosing it, was excessively troublesome to the wearer, and, when marching, two yokes were tied together by tree ends and loads put on the slaves' heads beside…A woman, having an additional yoke and load, and a child on her back, said to me on passing, 'They are killing me. If they would take off the yoke I could manage the load and child; but I shall die with three loads.' The one who spoke this did die; and her child perished of starvation." I interceded some, but when unyoked off they bounded into the long grass, and I was greatly blamed for not caring in the presence of the owners of the property. "[29]

Life and Explorations: Arab slave traders ‘revenging their losses’

“This wide-spread system of domestic slavery is, of course, an important ally of the foreign slave trade but the slave trade is in some respects a wrong and unutterable woe of itself. There is a certain international slave trade, if we may so speak, in Africa, carried on between tribes which are independent of each other. The importance of a chief is often estimated by the number of his slaves and wives. Now that the recent explorations of white men have made intercourse between tribes of more frequent occurrence than formerly, a rude diplomacy has sprung up, which is chiefly exercised in matters pertaining to slaves and the purchase of wives. A chief strengthens himself at home by marrying as many of the daughters of his "head men" as he can, and among other tribes by the same course among them. A large number of slaves adds to the consideration in which he is held at home and abroad. Thus polygamy, domestic slavery, and the foreign slave trade are the great obstacles which stand in the way of civilization in the continent of the black man. And of these the greatest obstacle is the foreign slave trade. This, not only because of its own cruelty, fearful wrongfulness, and hideous practices, but because it gives the black man a fairly unanswerable practical argument against civilization. Dr Livingstone expressly tells us, in letters which we have quoted, that the practices of the slave-traders are more horrible and cruel than even those of the man-eating Manyama. Is it to be expected that the natives of Africa will adopt a system which, so far as they see, is more cruel than the most horrible customs of their most degraded tribes?”[30]

Life and Explorations: Slaves abandoned

Wrecked ships of the trans-Atlantic slave trade

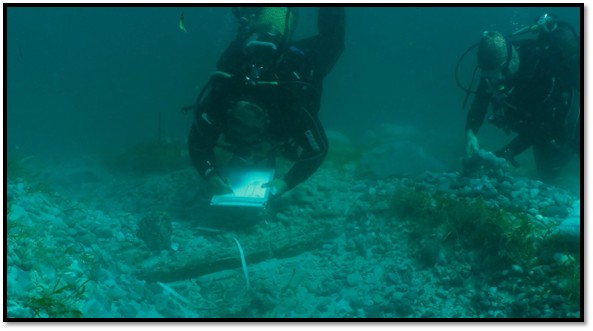

Currently close to Mozambique Island marine archaeologists coordinated by the Slave Wrecks Project (SWP), are exploring and recording the wreck of the L ’Aurore.[31] The French vessel left Mauritius for Mozambique in November 1789 to pick up slaves en route for the French Caribbean. In January 1790, as additional slaves from Mozambique were boarding the ship in the harbour, the 356 already on board attempted to mutiny, during which four of them drowned.

Because of the mutiny, the crew locked the slave men below deck. Women and children were kept in the main cabin. A month later, when the ship was due to leave, a storm hit and the ship began to sink. The crew refused to open the hatch to the lower deck until it was too late and 331 slaves died.

Divers documenting the 18th-century French slave ship L ‘Aurore

Marc-André Bernier, a Canadian underwater archaeologist and the developer of SWP’s training programme said,[32] “It may be the best 18th-century slave ship example.” The wreck is particularly well preserved and could reveal important insights into the structure of slave ships and the living conditions onboard. Most evidence points to the shipwreck being the L ‘Aurore. It lies in the area described in the captain’s account; its shape shows it was built using French methods and the ballast found was from Mauritius, the last port of call for L ‘Aurore before Mozambique.

In 2015, the SWP project identified the São José Paquete Africa, a Portuguese slave ship sailing from Mozambique to Brazil that was wrecked one hundred metres off-shore of Clifton Beach, Cape Town in December 1794.[33] The São José was making one of the earliest voyages of the transatlantic slave trade and was the first recorded wreck discovered of a ship that sank in transit with slaves, an estimated 212 drowned. Another 300 survived and were resold into slavery in the Cape. Slavery was tolerated in the Cape Colony[34] and most of the Cape slaves came from Indonesia and Madagascar, rather than the east African coast.[35]

Albie Sachs said in a speech, “It’s profound and terrible to feel this is one of the most beautiful beaches in the whole world and within such a short distance lie the bodies of 200 slaves who died there.”

The Slave Wrecks Project, an international collaboration, found a Portuguese archival document stating that the Saõ José had loaded 1,500 iron bars as ballast before she departed for Mozambique.

Another document revealing that a slave was sold by a local sheikh to the captain of the Saõ José prior to its departure, identified Mozambique Island as the port of departure.

Objects found from the shipwreck include fragile remnants of shackles, iron ballast to weigh down the ship and its human cargo, copper fastenings and a wooden pulley block.

The Slave Wrecks Project: iron ballast recovered from the São José Paquete Africa

Lonnie Bunch, director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture said, “Perhaps the single greatest symbol of the transatlantic slave trade is the ships that carried millions of captive Africans across the Atlantic never to return…This discovery is significant because there has never been archaeological documentation of a vessel that foundered and was lost while carrying a cargo of enslaved persons. The São José is all the more significant because it represents one of the earliest attempts to bring east Africans into the transatlantic slave trade – a shift that played a major role in prolonging that tragic trade for decades…Locating, documenting and preserving this cultural heritage through the São José has the potential to reshape our understandings of a part of history that has been considered unknowable.”[36]

A 19th century study of Mozambiquan slaves on Bourbon Island (now Réunion)

The trans-Atlantic slave trade had been operating for some time when the French East India Company was established in 1664 to challenge the dominance of the Dutch and British East India Companies in global trade. The sugar, coffee and indigo plantations on Bourbon Island required an abundant labour force and Madagascar and the east coast of Africa became the sources of the immense majority of the slaves brought to Bourbon Island in the late 18th century.

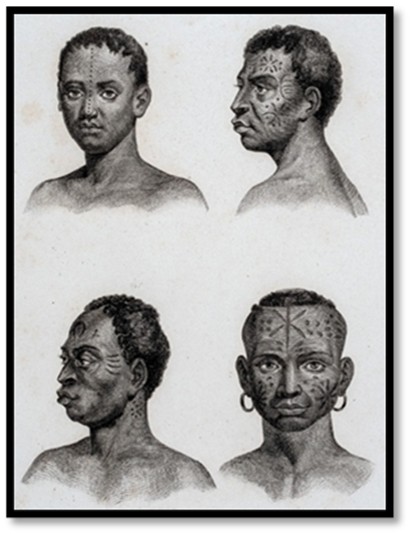

Klara Boyer-Rossol writes in an article The origin of the slaves on Bourbon Island[37] that in November 1845 Eugène Huet de Froberville made a ethnological study of ‘the languages and races of east Africa south of the Equator’ for the French Geographical Society that was based on interviews of ‘Mozambique’ slaves who had been transported to the island mainly between 1810-30.

Before 1770 most slaves came from Madagascar with about 20% from the east coast of Africa, however between 1770 - 1810 approximately 100,000 African slaves were imported into the Mascarene Islands, and although the slave trade was abolished in 1807 by Britain, slaves continued to be imported into Réunion. Between 1810 - 1848 it is estimated that over 75,000 slaves came to the Mascarene's from the east coast of Africa

During his short stay on Bourbon Island (now Réunion[38]) Froberville came into contact with some 200 ‘Mozambiques’[39] as they were called, from whom he gathered vocabulary of east African languages. They told him about the violence of the slavery system that operated on this colonial plantation island and he became convinced of the necessity of abolishing slavery in the French colonies.

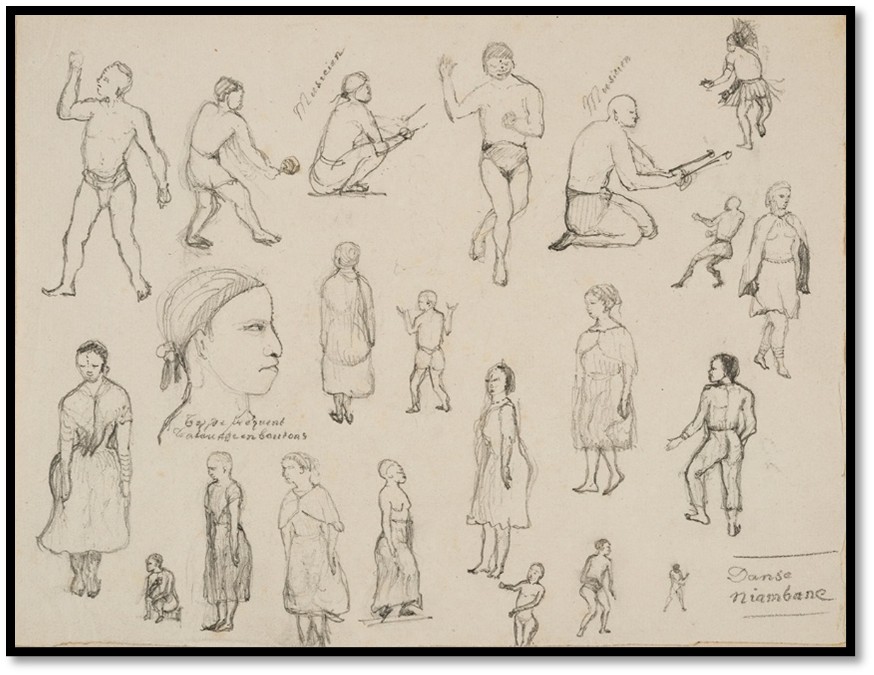

Peoples of Mozambique. Augustin François Lemaître. 1848.

Chiselled engraving. Collection of Villèle historical museum.

Michel Polényk collection, inv. ME.2013.128

Those ‘Mozambiques’ he questioned on Mauritius had been emancipated for about 10 years; on Bourbon Island they were still enslaved. The information he gathered, mainly from men on Bourbon and Mauritius Islands, in the form of notes, drawings and correspondence were studied by the author in 2018. Those on Bourbon were working on sugar plantations, or as craftsmen, or as domestic servants.

Froberville’s interest was in their countries of origin and the author identifies from his notes, four men and one woman, with their names, origins, languages, cultural practices and part of their travel from Mozambique to Bourbon. The author identifies four lists of vocabulary drawn up by Froberville on Bourbon Island including ‘Moadjaoua’ [Yao], ‘Maravi,’ ‘Makoua’ [Makua], and ‘Makōssi’ [or ‘Cafre,’ also confused with the category referred to as ‘Niambane’]”

The author states the Yao and Makua languages, as well as those of the Maravi (Chewa and Manganja) are still spoken today in Mozambique. The term ‘Niambane’ or ‘Yambane’ referred to all the captives deported through the port of Inhambane, located opposite Madagascar, and was not based on any socio-linguistic reality. The vocabulary collected from those referred to as ‘Niambane’ probably originated in the languages commonly used in the region around Inhambane.

The author adds that in “the context of slavery, retaining memories of their east African country of origin, original names (individual and collective), languages or music and dances, can be seen as forms of cultural and identity resistance by the ‘Mozambiques,’ who were among the last to be enslaved through the illegal trade to Bourbon Island.”

Among the native Africans interviewed by Froberville on Bourbon in 1845, are those named Virginie, Onsinānga, Malāssi and Mtchirima Thomas, who were legally slaves belonging to Adolphe Lory in Saint-Denis, as well as Mkūto Germain, a slave belonging to Louis de Tourris on his estate in Sainte-Suzanne. The interviews were conducted in the Creole language that Froberville, who was born on Mauritius Island, had no difficulty understanding

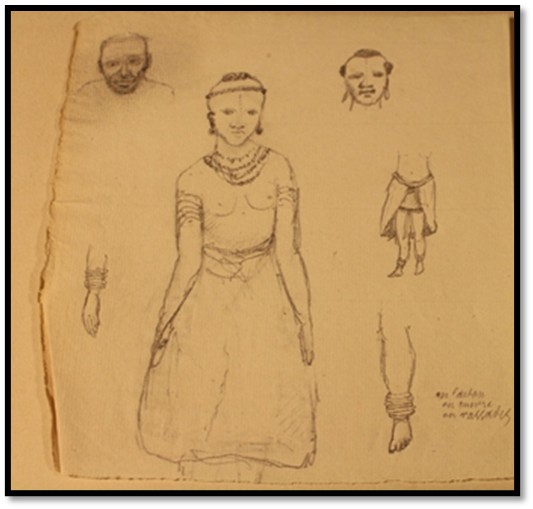

Virginie[40]

Virginie was seemingly born about 1809 in southern Mozambique, in the area of Inhambane and she had a line of tattooed dots from the top of her forehead down to the tip of her nose, characteristic of the ‘Niambane’. He calls her a ‘Makōssi-Niambane’ and she provided the ‘Makōssi’ vocabulary in Froberville’s notebooks.

The author concludes Virginie was at least 10 years old when she was deported, during the period 1820-30, probably from the coastal zone around Inhambane, before being shipped to Bourbon. Several illegal slave-trade expeditions transporting captives referred to as ‘Yambane’ were recorded on Bourbon during this period, notably those involving the vessel Deux-Frères in 1826 and that of Marie in 1827.

Eugène de Froberville. Drawing of a woman, with a tattoo on her forehead characteristic of the tribes referred to as ‘Makōssi’ and ‘Niambane’ © Private Archives and Collections of Huet de Froberville/Photographer F. Lauginie ©International Slavery Museum (ISM), Mauritius Island

Malāssi and Onsinānga

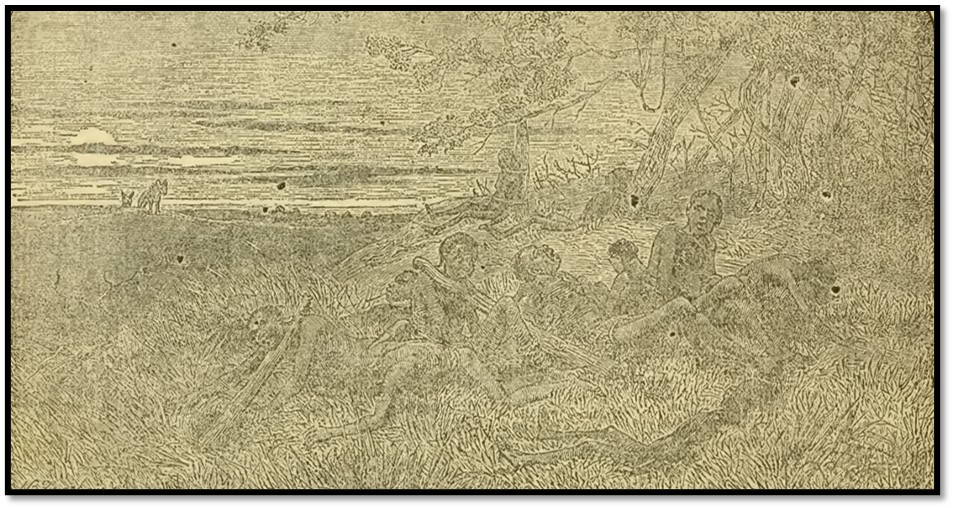

The slaves Malāssi and Onsinānga provided ‘Niambane’ and ‘Makōssi’ vocabularies. Onsinānga said he left his country at a young age from southern Mozambique and provided the ‘Makōssi’ and was described by Froberville, “the man is highly intelligent.” Froberville made some beautiful sketches representing ‘Niambane’ dances, showing their movements dancing in the round, or lines of men and women sharing cultures.

Eugène de Froberville. Drawings of ‘Niambane’ dancers.

© Private Archives and Collections of Huet de Froberville/Photographer F. Lauginie ©International Slavery Museum (ISM), Mauritius Island

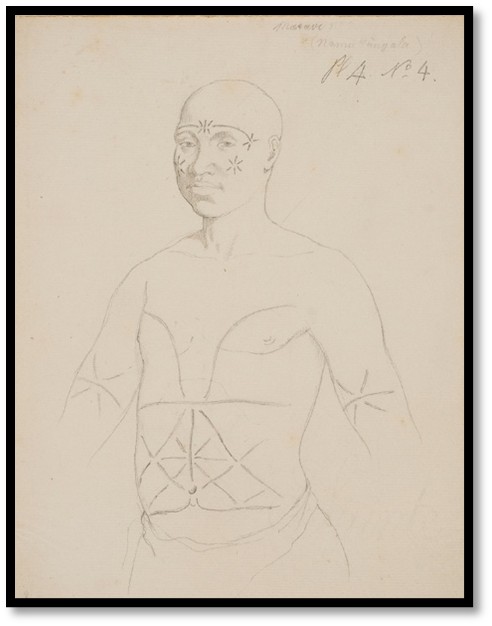

Mtchirima Thomas

Mtchirima Thomas was born around 1806-1810 and belonged to the Maravi people in the centre-west of Mozambique, a region bordering Malawi. He was taken by force to the port of Quelimane, his name ‘Mtchirima’ comes from ‘Tsirimane,’ the local name for Quelimane. When he was 15 or 16 years old, he was sent to Bourbon Island. The Portuguese at Quelimane in 1827-8 recorded ships supplying slaves for Bourbon where he was given the name Thomas and with fellow slaves forced to work as labourers, smiths, boilermen or foundry workers, Mtchirima Thomas provided Froberville with a large quantity of ‘Maravi’ vocabulary (some 80 pages). He bore the “marks of his country” in the form of the tattoo of the Maravi consisting in a sort of star carved out on the forehead, the temples and the chest. The Maravi would also file their incisors down to a point.

Drawing: Portrait of a Maravi man with star-shaped tattoos.

© Private Archives and Collections of Huet de Froberville

Photographer F. Lauginie ©International Slavery Museum (ISM), Mauritius Island

Mkūto Germain

Froberville interviewed Mkūto, of the Yao tribe who was old enough to be married when he was enslaved and taken from the north-west region of present-day Mozambique. Yao captives were forced to walk sometimes several months before reaching the coast at Kilwa or Moçambique. A slave trader in the early 19th century noticed that the Yao represented the majority of the captives.

On reaching Bourbon Island he was christened and given the name of Germain but had retained a memory of his country and the use of his language and Froberville’s notebooks contain some thirty pages of Yao vocabulary, words translated from French by Mkūto.

Slaves on Bourbon Island (now Réunion) mostly came from Madagascar and the east coast of Africa

In the early 18th century the French East India Company brought a small number of slaves from West Africa: 200 slaves from Juda in 1729, then 188 from Gorée in 1730 and 1731.

Some slaves also came from India on ships sailing back to mainland France, especially from 1728. It ceased for a time from 1731-4, then picked up again with hundreds of slaves arriving on Bourbon Island from Pondicherry. After 1767, slave traders on Bourbon had contacts in Pondicherry and Chandernagor and slave ships sailed to Goa from the Island.

Madagascar was an early source of slaves from the 10th century, and perhaps even earlier by Muslim traders. The Portuguese followed in the 16th century and then the Dutch and the British in the 17th century. Between 1685 and 1726, pirates who settled in the north of Madagascar occasionally brought slaves to Bourbon.

The French East India Company in developing its sugar, coffee and indigo plantations took control of the trade in 1717 and Madagascar was the closest source of slaves to Bourbon Island. The slave trade was restricted from 1789 to 1794, prohibited from 1794 to 1802, to be permitted once more, but ceased in Madagascar in 1820 when Britain forced a treaty on Radama, the Merina King, in which he agreed to put an end to the slave trade.[41]

The Mozambique Channel, Island of Madagascar, the States of Monomotapa and neighbouring kingdoms. Robert Bonne, cartographer; André, engraver. 18th century. Intaglio; coloured highlights. Collection of Villèle historical museum. Michel Polényk collection, inv. 2019.1.16

Slaves from Mozambique

Although the interior of the east coast of Africa was virtually unexplored by the Portuguese, from time to time, Portuguese sailors would sell a few slaves purchased at Mocambique Island or Quelimane to the settlers on Bourbon Island.

Things changed however In 1721 when the Viceroy of Portuguese India was forced to stop off at Saint-Denis, the victim of pirates, and sailed back to Portugal on a ship belonging to the French East India Company. To show his gratitude, he promised to write to the Portuguese authorities at Mozambique Island asking them to facilitate slave trading for the benefit of Bourbon Island.

The first shipments, however suffered heavy human losses during the voyage. Later better organised shipments took place between Mozambique Island and Bourbon Island twice each year, bringing over several hundred slaves. The trade stopped between 1746 and 1750, but as the gold trade from the African interior almost ceased, the slave trade then picked up again during the period of the French East India Company, even though the Portuguese authorities were supposed to reserve the Africans originating in Mozambique for the Brazilian market. Gradually however slave trading shifted from Sofala and Mozambique northwards to the Quirimbas Islands and the Muslim trading posts also started to gain popularity.

The East of Africa, the main source of slaves for Bourbon Island

During the final years of the French East India Company, the east coast of Africa became the main source of slaves, far surpassing Madagascar by a factor of five times and was mainly organised by the Yao, who sold at places along the coast those men, women and children they had captured in the region of Lake Nyassa.[42]

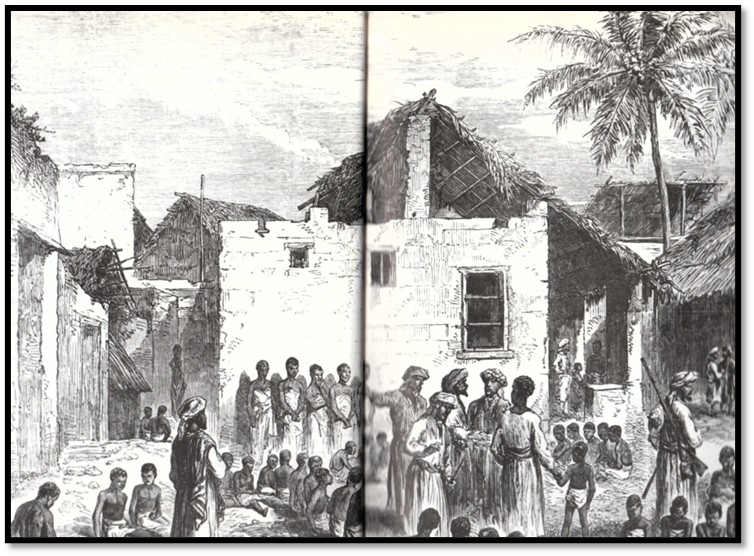

From about 1785 the bulk of the slaves came from the area of Cape Delgado (northern Mozambique) and present-day Tanzania, Kenya and Somalia with dhows being loaded at many small Muslim trading posts set up along the coast. This area, nominally under the rule of the Sultan of Muscat, but in reality independent, had as its main slave markets at Kilwa (formerly known as Quiloa) from 1770-94 and then Zanzibar from 1802. In 1856 when Richard Francis Burton and John Hanning Speke arrived at Zanzibar, Burton counted sixty dhows that had been blown across the Indian Ocean by the monsoon winds.[43]

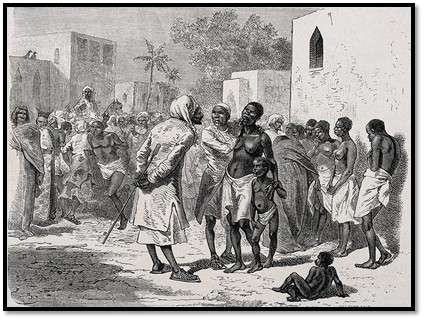

The slave market in Zanzibar. Emile Bayard. Bayard, Emile.

De Villèle Historical Museum.

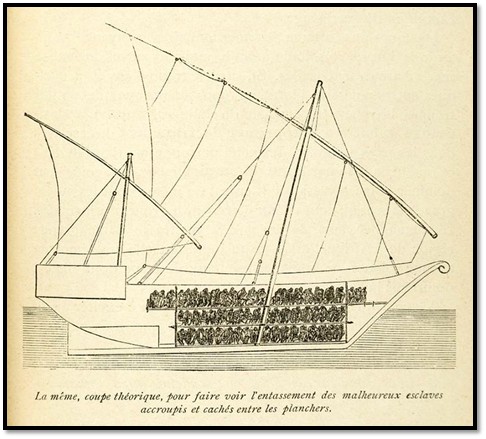

From the beginning of the 19th century sugar became the principal crop of Bourbon Island and required a large workforce and it came as a great shock to the island when Louis XVIII signed laws prohibiting slave trading in January 1817. The plantation owners reacted by trading slaves unlawfully and some 50,000 slaves came onto Bourbon Island between 1817-31.[44]

French authorities tried to combat slave trading, but prosecutions were few and far between, as a ship needed to be caught unloading its human cargo and so most slavers unloaded their cargoes at night in isolated locations. Catching a slave ship at sea could result in the captain throwing overboard his human cargo. Attempting to identify new arrivals on Bourbon caused an outcry from the plantation owners who considered this persecution.

Many on the island considered slavery essential for the economic prosperity of the island. The author points out the factors that gradually weighed against the use of slaves:

- Politically, the administration was compromised

- A gulf grew between France and the colony on the issue of slavery

- Without quarantine arrangements, new arrivals introduced health issues that could affect the whole island population

- As the trade was illicit, conditions for slaves worsened. Ships carrying slaves were smaller with the captives kept in terrible conditions and the death rate worsened.[45]

Dhow or slave boat, theoretical cross-section, showing piling up of unfortunate slaves crouching and hidden between floorboards. In “La traite des nègres et la croisade africaine comprenant la Lettre Encyclique de Léon XIII sur l’esclavage,

Le discours du Cardinal Lavigerie à Paris,” …. Alexis-Marie Gochet. 1889 ». De Villèle Historical Museum.

The fact that slavery was made illegal on Bourbon Island did not stop the trade in slaves

The author notes that the anti-slavery laws passed on Bourbon Island on 4 March 1831,[46] “punished the crew, the ship-owner and the insurers of slave ships with confiscation of the vessel and its cargo, heavy fines and forced labour for the officers. In addition, those selling, dealing in and purchasing new slaves faced imprisonment.” They were not actively enforced.

She quotes Hubert Gerbeau, who states approximately 4,500 slaves arrived illicitly on Bourbon Island between 1832-35; Hai Quang Ho estimates 5,000 between 1836-47 and Serge Daget, between 1815-32 believes of the new slaves, 43% came from the east coast of Africa (25% of these from Zanzibar), 36% from Madagascar (mainly Tamatave, present-day Toamasina), 15% from the west coast of Africa (especially Bonny, in the region of the Niger delta) and 6% from the Cape.

Finally she makes the point that slave trade on Bourbon Island constituted only a small proportion of the global trade, although it had a dramatic impact on the island itself.

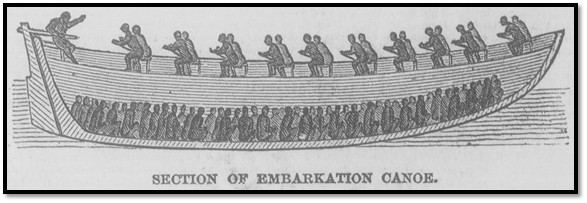

From Slave Voyages: The Illustrated London News (Apr. 14, 1849), vol. 14, p. 237

In West Africa, canoes usually transported slaves from the coast to the transatlantic vessel. According to The Illustrated London News, during the 1840’s in Sierra Leone, such canoes could carry 200 slaves, with their size being, "about 40 feet long, 12 feet broad, and seven or eight feet deep."

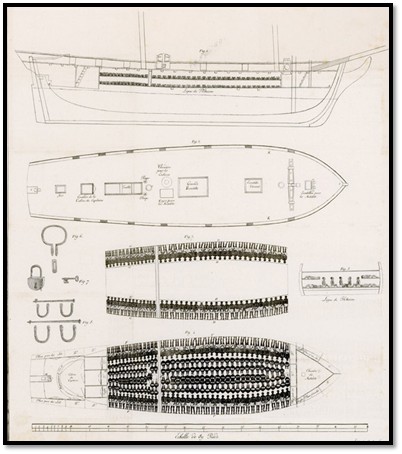

Slave Voyages : Affaire de la Vigilante, bâtiment négrier de Nantes (Paris, 1823)

The Brig “Vigilante” was a French slaver captured in the River Bonny, Biafra, on 15 April 1822. She was carrying 345 African slaves, but she was intercepted by a British anti-slave trade cruiser before sailing to the America’s and taken to Freetown, Sierra Leone. The image above is from an 1823 pamphlet is of a plan of the “Vigilante,” showing the slave decks and the instruments used to chain the slaves.

The slave trade in the 1880’s became an African affair

In the 1880’s a change took place as the main ports were no longer used for slave trading and new, less known places were used. This brought about a corresponding change in the caravan routes and in the trade itself. The traders organised armed African groups that went further into the interior around the Shire river and Lake Malawi to capture slaves. Newly captured male slaves were recruited into private armies (chikunda) who served the various warlords.

Newitt quotes the Anglican missionary W.P. Johnson, “the heads of caravans made friends with the head men …and generally left some intelligent man at the larger villages there, who would pick up a good number of slaves while they themselves…made friends with the chiefs there, principally with the Angoni. Sometimes they would help these chiefs with their guns in raiding and so have a share of the captives. At other times they would buy captives already taken by the Angoni…such people taken in war, furnished the principal supply of slaves, but two other classes are fairly large. First, there were people who had been sold in order to get rid of them, for instance those who had been convicted on some serious charge of witchcraft, which might or might not mean that the man or woman was a really bad character. Anybody who was merely suspected for having caused the death of another might be sold away from his village if he was friendless…Second, another class of slaves consisted of people sold away in times of great famine. This need not imply any cruelty on the part of their relatives as those who were sold were often willing to go for the sake of getting food…”[47]

Slaves from Tanzania were mostly traded through Zanzibar Island

Thomas Smee, captain of the British ship Ternate who visited Zanzibar in 1811 wrote, “the show commences about 4pm in the afternoon. The slaves, set off to the best advantage by having their skins cleaned and burnished with coconut oil, their faces painted with red and white stripes, which is here esteemed elegance, and the hands, noses, ears and feet ornamented with a profusion of bracelets of gold and silver and jewels, are ranged in a line, commencing with the youngest, and increasing to the rear according to their size and age. At the head of this file, which is composed of all sexes and ages from 6 to 60, walks the person who owns them; behind and at each side, two or three of his domestic slaves, armed with swords and spears serve as a guard.

Thus ordered the procession begins and passes through the marketplace and the principal streets; the owner holding forth in a kind of song the good qualities of his slaves and the high prices that have been offered for them. When any of them strikes a spectator’s fancy the line immediately stops, and a process of examination ensues, which, for minuteness, is unequalled in any cattle market in Europe. The intending purchaser having ascertained there is no defect in the faculties of speech, hearing, etc, that there is no disease present, and that the slave does not snore in sleeping, which is counted a very great fault, next proceeds to examine the person; the mouth and the teeth are first inspected and afterwards every part of the body in succession, not even accepting the breasts, etc, of the girls, many of whom I have seen handled in the most indecent manner in the public market by their purchasers; indeed there is every reason to believe that the slave dealers almost universally force the young girls to submit to their lust previous to there being disposed of. The slave is then made to walk or run a little way, to show there is no defect about the feet; after which, if the price be agreed to, they are stripped of their finery and delivered over to their future master…”[48]

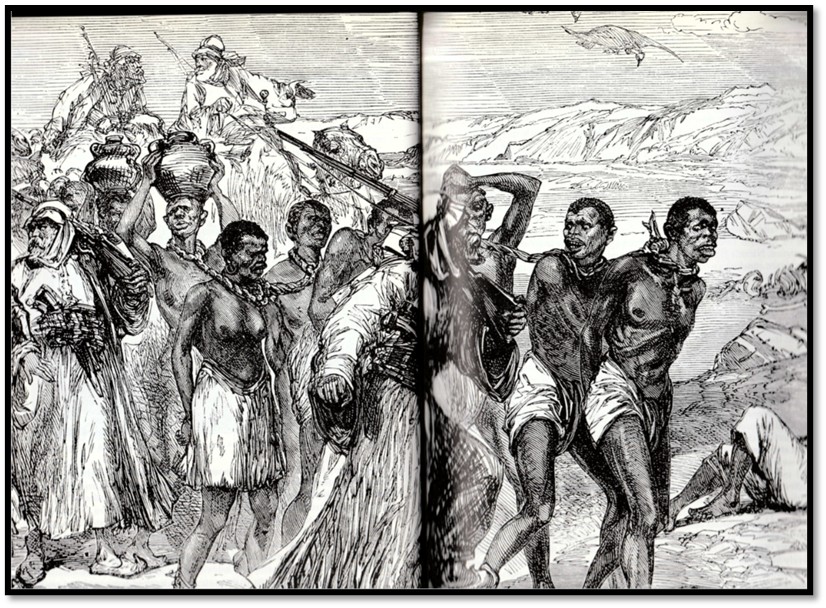

Moorehead: the Zanzibar slave market

In 1845 the Sultan of Zanzibar declared that the export of slaves was forbidden, although slavery within Tanzania continued to be legal, and British and French men-of-war patrolled the coast in search of Arab dhows bringing slaves from the mainland. Despite these efforts, Moorehead continues, “And so the caravans were still raiding into the interior; the dhows, with their cargoes close-packed beneath the decks, were still successfully running the blockade of the warships; and Zanzibar market was as crowded as ever.”[49]

Prices in 1856 were £4-£5 for an adult slave in Zanzibar and more for a female. Between 20-40,000 slaves were being brought to Zanzibar annually, one-third to work on the island’s plantations, the remainder exported to Saudi Arabia, Iran, Egypt, Turkey and even further. Estimates were that thirty percent of the males died annually from malnutrition and disease. The highest prices were paid for Ethiopian and North Caucasus (Circassian) girls, but they were rare, and seldom left the island being reserved for the rulers harem. Some of the Arabs on Zanzibar owned as many as 2,000 slaves.[50]

When Speke and Burton marched inland in 1857-9 and on 13 February 1858 reached Lake Tanganyika near the Arab slaving and ivory village at Ujiji they had no difficulty with the route from the coast which was from village to village and followed the established route of the slave and ivory caravans from the interior. Moorehead writes, “Burton and Speke passed huge slave caravans, some of them a thousand strong and saw the tragic aftermath of their progress - the sick men, women and children dying beside the track…”[51]

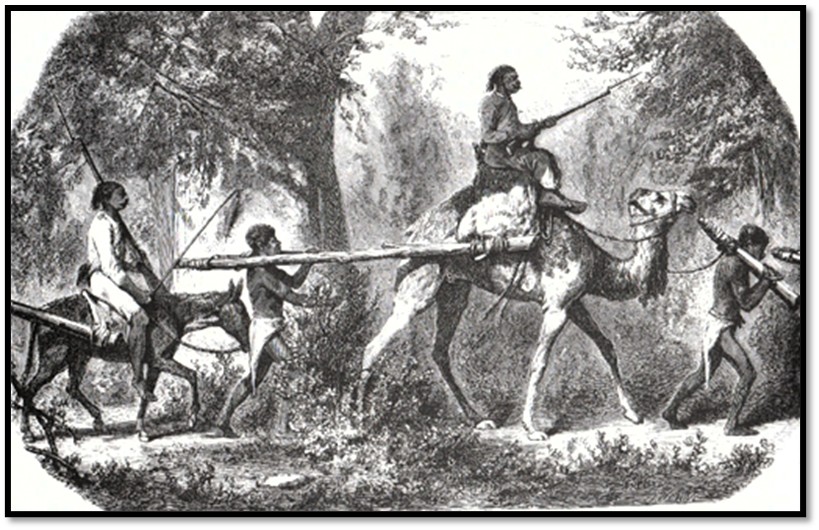

Whilst all slave and ivory caravans south of the Equator headed for Zanzibar, those to the north descended the White Nile to Khartoum. Moorehead in quoting from Samuel White Baker states, “in a rough and haphazard fashion the Egyptians ruled the Sudan from Khartoum; but perhaps pillaged is a better word than ruled. Practically every official from the Governor General Musa Pasha downwards was involved in some way in the slave trade[52]… it was the slave trade that kept Khartoum going…On a normal expedition such a trader would sail south from Khartoum in December with two or three hundred armed men and at some convenient spot would land and form an alliance with a native chieftain. Then together the tribesmen and the Khartoum slavers would fall upon some neighbouring village in the night, firing the huts just before dawn and shooting into the flames. It was the women that the slavers chiefly wanted, and these were secured by placing a heavy forked pole known as a sheba on their shoulders. The head was locked in by a crossbar, the hands were tied to the pole in front, and the children were bound to their mothers by a chain passed around their necks. Everything the village contained would be looted – cattle, ivory, grain, even the crude jewellery that was cut off the dead victims - and then the whole cavalcade would be marched back to the river to await shipment to Khartoum.”[53]

Moorehead: Slaves being driven to Khartoum or Zanzibar by their Arab masters

Britain becomes active in subduing the slave trade

The Royal Navy conducted regular sea patrols in the Mozambique Channel and these were supplemented by consulates at Zanzibar (1840) the Comoro Islands (1850) and at Mozambique Island in 1856.

David Livingstone made a major impact on the anti-slavery movement. He was first in the Zambesi Valley in 1856 in the final stage of his journey across Africa from Portuguese Angola. Later in an attempt to substitute the slave trade with commerce, he persuaded the British government to sponsor a Zambesi expedition (1858-64) from Mozambique believing the Zambesi river was navigable, but the Cahora Bassa gorge proved impassible. Thwarted he explored the Shire river and the Lake Malawi region. See the article Thomas Baines’ disastrous 1858-9 Zambezi Expedition with David Livingstone under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Livingstone spent twenty-two years travelling in Africa; his books made him the most famous of all the African explorers, although he cared nothing for fame; his objectives were to fight slavery and to explore the river system in the African interior.

In 1866, ten years after Burton, nothing much had changed in Zanzibar; “the traffic in slaves had grown if anything still heavier; it was now estimated that between 80,000 and 100,000 were brought down from the interior every year, and although none was supposed to go beyond the Sultan's dominions, there was no real check on the dhows that sailed back to Arabia and the East in June when the south-west monsoon began to blow.”[54]

Livingstone’s plan was to journey in the unexplored country south of Lake Tanganyika beginning in March 1866 at the mouth of the Rovuma river.[55] His aim was to put down slavery, but he was alone and powerless; yet paradoxically Livingstone witnessed a massacre which, when reported by him, dealt slavery a mortal blow.

David Livingstone in 1864

By the end of 1866 he was sick and near death at the southern end of Lake Tanganyika having lost nearly all his porters and mules and his medicine chest. There the Arab slavers took care of him before he struggled on to the west and the Lualaba river.[56] On 15 July 1871 he witnessed a massacre of villagers at a market by three of Tagamoio’s (an Arab slaver) armed men over a dispute about a fowl. After the initial burst of firing the villagers dropped their goods and many jumped in panic into a nearby creek and continued to be fired upon. Dugombe (a trader and slaver) came and rescued over twenty people, but the remainder drowned.

The Arabs themselves estimated up to 400 persons perished. Livingstone wanted to use his pistol on the killers, but Dugombe persuaded him it would start a blood feud. Tagamoio’s men continued to fire on the villagers and burnt down their village. Without porters and supplies, Livingstone struggled back to Ujiji only with the aid of the Arab slavers. There he met Henry Morton Stanley on 10 November 1871.

Sultan Barghash at Zanzibar was very reluctant to make slavery illegal, but the massacre reported by Livingstone brought to a head the horror it was causing in Africa’s interior. The British consul John Kirk pressured Barghash into signing a new treaty. Zanzibar’s slave market was to be closed and the shipping of slaves abolished.

The slave trade proved difficult to eradicate entirely, even though the Zanzibar slave market closed in June 1873. Slaves continued to be captured in the interior and smuggled in dhows across the Indian Ocean. Even in 1901 in the interior of Mozambique it continued under Islamic warlords, Marave and Farelay, who supplied slaves to Angoche in a clandestine trade.[57]

Moorehead: a slave caravan in the interior of East Africa

Appendix 1

Nathan Nunn: Shackled to the Past: The Causes and Consequences of Africa’s Slave Trades

References

Klara Boyer-Rossol. Bonn Centre for Dependency and Slavery Studies (BCDSS) and International Centre for Research on Slavery, and Post-Slavery (CIRESC) The origin of the slaves on Bourbon Island

Klara Boyer-Rossol. Bonn Centre for Dependency and Slavery Studies (BCDSS) and International Centre for Research on Slavery, and Post-Slavery (CIRESC) Where did the slaves on Bourbon island come from? https://www.portail-esclavage-reunion.fr/en/documentaires/the-slave-trade/the-origin-of-the-slaves-on-bourbon-island/mozambique-slaves-on-bourbon-island-based-on-the-manuscript-notes-of-eugene-huet-de-froberville-made-during-his-stay-on-the-island-in-1845/

R.N. Hall. Prehistoric Rhodesia. T. Fisher Unwin, London, 1909

Life and Explorations of David Livingstone…and including his last Journals. John E. Potter & Company, Philadelphia

Alan Moorehead. The White Nile. Penguin Books Ltd, London 1973

Carlos Mureithi, photographs by Yuri Sanada. The Guardian.org. 16 Oct 2024. ‘People did not go quietly’: divers explore wreck of 18th-century slave ship where mutiny took place. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2024/oct/16/divers-explore-18th-century-slave-ship-off-mozambique

Malyn Newitt. A Short History of Mozambique. Hurst & Company, London, 2017

Nathan Nunn. Shackled to the Past: The Causes and Consequences of Africa’s Slave Trades. August 2008 Abstract

David Smith. The Guardian.org. 1 Jun 2015. South Africa beach service to honour slaves drowned in 1794 shipwreck. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jun/01/cape-town-beach-service-honour-african-slaves-drowned-1794-shipwreck

The Slave Wrecks Project (SWP) https://global.si.edu/projects/slave-wrecks-project

Notes

[1] Shackled to the Past: The Causes and Consequences of Africa’s Slave Trades

[2] See Appendix 1

[3] The greatest number of slaves probably came from Ethiopia and Sudan

[4] For details of modern slavery refer to the Walk Free website https://cdn.walkfree.org/content/uploads/2023/09/28090714/GSI-Snapshot-Zimbabwe.pdf

[5] David Eltis and David Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade (New Haven, 2010)

[6] Slave Voyages Explore the Origins and forced Relocations of Enslaved Africans Across the Atlantic World

The now eight member institutions of Slave Voyages are Emory University (the original host institution) Rice University (the new hosting institution) the University of California campuses at Berkeley, Irvine, and Santa Cruz, Harvard University, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture, the University of the West Indies at Cave Hill, Barbados, and Washington University.

[7] Wikipedia on abolition of slavery

[8] South Africa beach service to honour slaves drowned in 1794 shipwreck

[9] The earliest record of Sofala (south of present-day Beira) dates from the 10th century when the Arab chronicler al-Masudi records the existence of the port

[10] By the 14th century Kilwa was the most powerful kingdom along the coast - situated on an island some 680 kms north of Mozambique Island. During its heyday, Kilwa was the foremost port in a string of coastal trading cities that formed along what became known as the Swahili Coast.

[11] The only two major deepwater ports in Mozambique were Delagoa Bay in the south and Nacala, north of Mozambique Island, although Nacala was little used

[12] Pedro Alcáçova (1524-1579) was a Jesuit of the Society of Jesus who worked mostly in Japan but died most probably in Goa.

[13] Island of Mozambique (Portuguese: Ilha de Moçambique)The original Swahili traders came from Quiloa (Kilwa) and had close links with Angoche and Quelimane. The Portuguese established a permanent presence here in 1507 and built Fort São Sebastião. It became an important transit point for Portuguese ships going to India, a base for Jesuit missions into the interior and the capital of Portuguese East Africa until 1898.

[14] There are articles on the website www.zimfieldguide.com covering the following Portuguese feiras – Angwa (Ongoe) Dambarare, Luanze, Massapa (Baranda Farm) and Maramuca

[15] Prehistoric Rhodesia, P49-50

[16] Ibid, P54

[17] Ibid, P56

[18] The Dutch attacked Mocambique Island In 1607 and 1608 and although they failed in their attempts it made the Portuguese very aware of their precarious hold

[19] Fort Jesus was ruled by Swahilis from 1741 to 1837, then again held by the Omanis until occupied by Britain in 1895,

[20] A Short History of Mozambique, P50

[21] A Short History of Mozambique, P6

[22] Newitt writes that in the 18th century Indians were actively involved in financing the east African slave trade and providing shipping out of Bombay (present-day Mumbai) and Damao ports (A Short History of Mozambique, P53)

[23] Wikipedia: Mozambique

[24] The strongholds were known as aringas

[25] A Short History of Mozambique, P50

[26] The Maravi empire existed from the 15-19th centuries, reaching its greatest extent in the 17th century Father Manuel Barretto, a Jesuit priest, said the Maravi empire was a strong, economically active confederation that swept an area from the coast of Mozambique between the Zambezi River and Quelimane for several hundred kilometres into the mainland.

[27] Wikipedia: Mozambique

[28] Eric Allina, Slavery by Any Other Name. African Life under Company Rule in Colonial Mozambique. Portuguese Studies Review 2013, P253-65 Book Review by Michel Cahen

[29] Life and Explorations of David Livingstone, P352-3

[30] Life and Explorations of David Livingstone, P446-7

[31] ‘People did not go quietly’: divers explore wreck of 18th-century slave ship where mutiny took place.

[32] The Slave Wrecks Project (SWP) is a partnership between the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, Iziko Museums of South Africa, the U.S. National Park Service, the South African Heritage Resource Agency, Diving With a Purpose, and the African Centre for Heritage Activities, seeks to bring greater awareness to the study of sunken slave ships and build capacity for research and education in the field of maritime archaeology.

[33] South Africa beach service to honour slaves drowned in 1794 shipwreck.

[34] David Livingstone wrote, “The original inhabitants of this region were the Hottentots, a race bearing more resemblance to the Mongols than to the negroes having broad foreheads, high cheek bones, oblique eyes, thin beards, and a yellow complexion. They are of a docile disposition, and quick intellectual perception. They were possessed of vast herds of cattle and large flocks of sheep but were enslaved by the Dutch. Emancipated in 1833 by England, they are still found all over this region - still enslaved by the Boers in their so-called republics and in small bodies here and there to a great distance in the interior.” Life and Explorations of David Livingstone, P437-8

[35] A Short History of Mocambique, P 52

[36] South Africa beach service to honour slaves drowned in 1794 shipwreck.

[37] The article is on the website https://www.portail-esclavage-reunion.fr/en/documentaires/the-slave-trade/the-origin-of-the-slaves-on-bourbon-island/mozambique-slaves-on-bourbon-island-based-on-the-manuscript-notes-of-eugene-huet-de-froberville-made-during-his-stay-on-the-island-in-1845/

[38] Bourbon Island, now officially known as Réunion Island, is located in the Indian Ocean. It's an overseas department and region of France, situated east of Madagascar and southwest of Mauritius. The island is part of the Mascarene Islands that comprise Réunion, Mauritius, and Rodrigues

[39] The term ‘Mozambiques’ was used in 18/19th centuries to describe east African slaves that the author believes constituted Mozambique, Malawi and Tanzania

[40] This is not her African name, but given her on arriving on Bourbon Island

[41] A Short History of Mozambique, P67

[43] The White Nile, P16

[44] Ibid

[46] France is unusual in outlawing slavery twice in its colonies: First during the Revolution on 4th February 1794, and the secondly on 27th April 1848 during the Second Republic by Victor Schoelcher

[47] A Short History of Mozambique, P68-9

[48] The White Nile, P17-18

[49] The White Nile, P21

[50] Ibid, P21-2

[51] Ibid, P34

[52] Ibid, P78

[53] Ibid, P80-1

[54] The White Nile, P100

[55] The Rovuma river forms the present-day border between Tanzania and Mozambique

[56] The Lualaba river within the present-day Democratic Republic of Congo, flows north and then west forming the largest tributary of the Congo river. Livingstone believed it might be the Nile.

[57] A Short History of Mozambique, P101