The Bent’s archaeological expedition to Great Zimbabwe in 1891 and the prominent part played by Mabel Bent

Source

Much of the information in this article comes from the very comprehensive website Theodore and Mabel Bent (http://tambent.com/) by the author Gerald Brisch. Theodore Bent wrote over 150 articles, papers and lectures with many listed on the above website. Both Theodore and Mabel Bent were prolific authors and their books are also listed on the website. Other information and details of their journey came from Bent’s book The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland written very rapidly on their return home at 13 Great Cumberland Place, London – it proved very popular and ran to five editions. Finally, I used facsimile copies of Mabel’s notebooks stored at the Hellenic Society, University College London.

Theodore’s conclusions were soon being challenged by archaeologists, notably David Randall-McIver in 1905 and Gertrude Caton-Thompson in 1929. The evolution of thought on the origin of Great Zimbabwe and the many other stone buildings and gold mines are traced in the article The controversy in the early 20th Century over whether the stone structures in Zimbabwe were old and built by foreigners or comparatively recent and built by the Mashona under Masvingo Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Mabel deserves an accolade for being one of the earliest European women into present-day Zimbabwe and bravely endured the rigours of travelling at that time by ox-wagon, horse, donkey and on foot.

The Bent's notebooks at the Hellenic Society, London

The extent of their travels to visit archaeological sites can be seen from their notebooks and Mabel always accompanied Theodore as his wife, photographer and illustrator.

Mabel Bent's Notebooks

Greece and the Middle East

Mabel Bent (1883/4): The Greek Cyclades

Mabel Bent (1885): The Greek Dodecanese

Mabel Bent (1886): From Istanbul, the islands along the way (including Mitilini, Chios, Samos, Patmos, Ikaria, Samos, Kalymnos, Astypalea) and down the Turkish coast

Mabel Bent (1887): Central Greece and the Northern Aegean (including Evia, Meteora, Skiathos, Thessaloniki, Kavala, Thasos, and Samothraki)

Mabel Bent (1888): The west coast of Turkey (including Smyrna, Istanbul, Broussa, and as far south as Kastelorizo)

Mabel Bent (1890): Further researches along the Turkish coast (including Mersin, Tarsus, ancient Cilicia, the discovery of ‘Olba’, and into Armenia)

Bahrain and Iran

Mabel Bent (1888/9): Researches in Bahrain and a ride, south–north through ‘Persia’ (including Persepolis, Shiraz, Isfahan, and Tehran)(I)

Mabel Bent (1889): Researches in Bahrain and a ride, south–north through ‘Persia’ (including Persepolis, Shiraz, Isfahan, and Tehran)(II)

Mabel Bent (1889): Researches in Bahrain and a ride, south–north through ‘Persia’ (including Persepolis, Shiraz, Isfahan, and Tehran)(III)

Africa and Egypt

Mabel Bent (1884/5): Egypt (before steaming to the Greek Dodecanese)

Mabel Bent (1890/1): South Africa and the expedition to Great Zimbabwe (I)

Mabel Bent (1890/1): South Africa and the expedition to Great Zimbabwe (II)

Mabel Bent (1895/6): Sudan and the western Red Sea littoral

Mabel Bent (1897/8): Alone in Egypt (‘A lonely, useless journey’)

Southern Arabia

Mabel Bent (1893/4): Wadi Hadramaut (first attempt, via Mukalla) (I)

Mabel Bent (1893/4): Wadi Hadramaut (first attempt, via Mukalla) (II)

Mabel Bent (1894/5): Wadi Hadramaut (second attempt, via Muscat, Oman and the discovery of Abyssapolis/Khor Rori)

Mabel Bent (1896/7): Sokotra and Aden (this volume has not yet been scanned [Feb 2022])

Theodore Bent's Notebooks

Theodore Bent (1888): Inscriptions from Patara, Lydae, Lissa, Myra, Kasarea, Nicaea, etc.

Theodore Bent (1895/6): Sudan and the western Red Sea littoral

Theodore Bent (1893/4): Wadi Hadramaut (first attempt, via Mukalla) (I)

Theodore Bent (1893/4): Wadi Hadramaut (first attempt, via Mukalla) (II)

Theodore Bent (1894/5): Wadi Hadramaut (second attempt, via Muscat, Oman and the discovery of Abyssapolis/Khor Rori)

Theodore Bent (left) at a campsite in Sokotra in 1897

Theodore Bent (1896/7): Sokotra

Theodore Bent (1896/7): Sokotran glossary and notes (Bent’s final notebooks)(I)

Theodore Bent (1897): East of Aden (Bent’s final notebooks)(II)

Some background

As can be seen from their notebooks the Bent’s spent many years travelling and excavating, but by 1890 it was getting much harder to get unlicensed and unscientific excavations approved of by the authorities and Theodore decided to move elsewhere, preferably a British-controlled territory. The small island of Bahrain had grave mounds that might be linked to the Phoenicians and seemed an ideal excavation possibility; the Bent’s began excavating in February 1889. But after fourteen days they decided that Bahrein offered few opportunities and left.

Bent’s two weeks digging in Bahrain led to a presentation to the Royal Geographic Society (RGS) in early November 1889 of a paper on his ‘Phoenician’ Bahrain finds and this was followed by E.A. Maund who gave a RGS lecture on 24 November on the ‘On Matabele and Mashona lands” illustrated by photographs.[1] Maund’s lecture was followed by talk from E.A. ‘Elephant’ Philips who had traded in Matabeleland for twenty-six years and spoke about the threat of malaria and how he rescued Karl Mauch and Adam Renders in 1871 in the vicinity of Great Zimbabwe.[2]

Bent commented at that lecture that pottery had been found by Sir John Kirk near Zanzibar which was thought to be of Persian origin and suggested that if the Phoenicians reached Zanzibar, they might also have reached Great Zimbabwe before adding, “But of course this theory is open to doubt, and I am perfectly certain that nothing definite will ever be found out about these forts until they are thoroughly dug out and investigated, when perhaps some inscription will be found that will prove that both Mr Maund and I are quite wrong.”

How Theodore Bent was appointed to excavate at Great Zimbabwe

Gerald Brisch believes that Bent’s opinion that the origins of Great Zimbabwe would remain a mystery “until they are thoroughly dug out and investigated” might have caught Maund’s eye. The apparent association between the ancient civilisation of Phoenicia and Great Zimbabwe probably led to Bent’s appointment to excavate at Great Zimbabwe when Rhodes was informed about the lecture.

Rhodes had been quoted as saying, “You will find that Zimbabye is an old Phœnician residence and everything points to Sofala being the place from which Hiram fetched his gold.” Rhodes decided Bent’s supposed knowledge of the Phoenicians made him the ideal candidate for excavating at Great Zimbabwe and would hopefully vindicate Rhodes’ claim that it was not built by local people living around the site.

Rhodes belief that local people appeared to know nothing about the ruins at Great Zimbabwe and elsewhere and Theodore Bent’s inclinations towards establishing distant cultural and trading contacts with the Middle East made the basis for a good shared relationship that would hopefully shed new light on the region. Already theories were circulating that Phoenician vessels would have passed from the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean and travelled down the East African coast to Sofala and then gone up the Sabi (Save) river.

Theodore Bent's archaeological expedition to Great Zimbabwe in 1891 was primarily financed by the British South Africa Company (BSAC) with additional support from the Royal Geographical Society who made a grant of £200 and the British Association for the Advancement of Science.[3]

The Bent’s prepare for their first expedition to Southern Africa

Theodore quickly circulated a press release. The American Register of Saturday, 13 December 1890 is typical of what the newspapers reported, “At a meeting of the council of the Royal Geographical Society it was agreed to contribute £200 to Mr Theodore Bent for the purpose of exploring the remarkable ruins in Mashonaland about which so much has recently been heard in connection with the British South African Pioneer Expedition. The ruins have been known since the sixteenth century, and been described by Karl Mauch and others, but no systematic examination and excavations have ever been carried out. This Mr Bent will undertake, and it is hoped he will thus be able to throw light on the origin of these mysterious buildings.”

The Bent’s journeys in Southern Africa

They travelled by steamer to Cape Town and then by train to Kimberley where the railway line terminated. Then by ox-wagon to Fort Victoria for the period of excavating at Great Zimbabwe. Following which they took donkeys and travelled to Matendere monument, afterwards passing Mount Wedza to Fort Salisbury, Then a short journey north of Salisbury to the Mazoe (Mazowe) Valley, followed by a journey to Chief Mtoko and then through the first Umtali to Mapanda’s on the upper reaches of the Pungwe river and down to Beira. Their steamer reached Cape Town on 11 December 1891 where they had dinner with Cecil Rhodes[4] and from there the longer voyage home via Madeira and Lisbon arriving in London at the end of January 1892.

Fort Tuli to Fort Victoria

They left Fort Tuli on 9 May 1891 and trekked with their two wagons and thirty-six oxen up the road the Pioneer Column had cut nine months earlier. They visited the small circular ruins on the Lundi (Runde) river and noted the herring-bone pattern facing the south-east and speculated it was connected with some form of sun worship.

Mabel Bent: ruin on the Lundi (Runde) river

Mabel and Theodore Bent arrive at Great Zimbabwe

Their wagons appear to have been the first to reach Great Zimbabwe. Theodore writes there was a footpath from Fort Victoria “and active persons have been known to go there and back in a day” but it took them seven days to cover the 14 miles (23km) with their wagons over the marshy ground arriving on site after three months of trekking on 6 June 1891.[5]

Measurement and maps were made by Robert M.W. Swan who accompanied the Bent’s throughout. His south latitude reading for the Great Enclosure is almost perfect at 20° 10´ 30", but his east longitude at 31° 10´ 10" is 25km too far east (should be 30° 55´ 51")

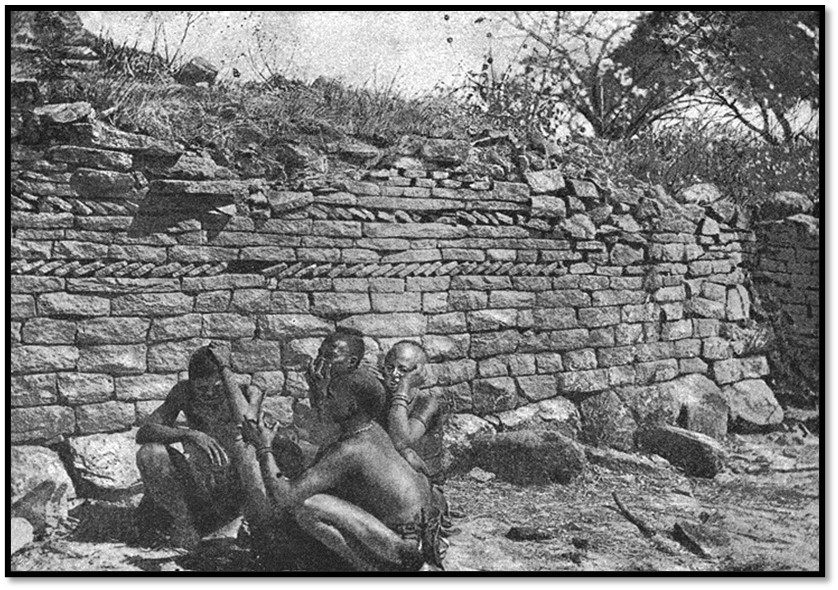

The excavations took two months and they employed thirty of Chief Mugabe’s men each earning one blanket a month costing 4s 10d at Fort Tuli “and for a teaspoonful of beads they would do any amount of extra work.”[6] Theodore writes, “I almost despaired of getting rid of the thick jungle which filled the large circular ruin, so that it was almost impossible to stir in it. This they contrived to do for us in three or four days, hacking away at stout trees and branches with their absurd little hatchets, and obtaining the most satisfactory results.”

Mabel Bent: The Conical Tower in the Great Enclosure in 1891

Ikomo, brother of Chief Mugabe who lived near the Hill Complex told them his people had arrived at the site about forty years before when he was eighteen years old from the area of the Sabi (Save) river. “No one was then living on Zimbabwe Hill, which was covered, as it is still in parts, with a dense jungle. No one knew anything about the ruins, neither did they seem to care. This is how all tradition is lost among them. The migratory spirit of the people entirely precludes them from having any information of value to give concerning the place in which they may be located...”[7]

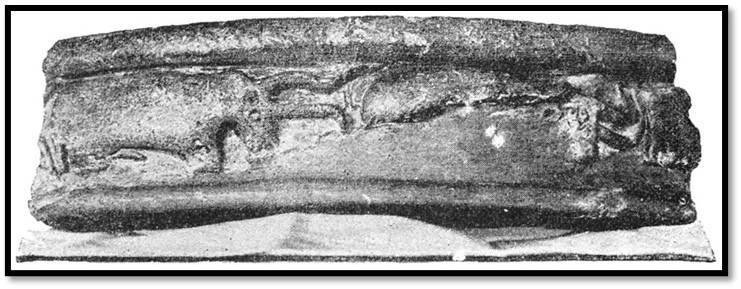

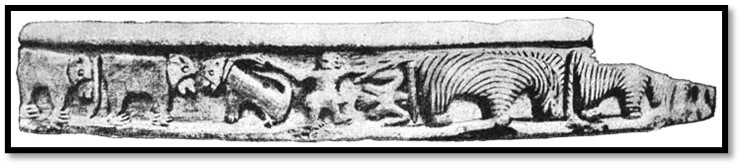

Mabel Bent: Fragment of bowl with procession of bulls

Mabel Bent: fragment of bowl with hunting scene

Mabel Bent: fragment of bowl with zebras

A constant theme of Bent’s book is the Phoenician origins of Great Zimbabwe, “Turning to Phœnician temple construction, we have a good parallel to the ruins of the Great Zimbabwe at Byblos; as depicted on the coins, the tower or sacred cone is set up within the temple precincts and shut off in an enclosure…”[8]

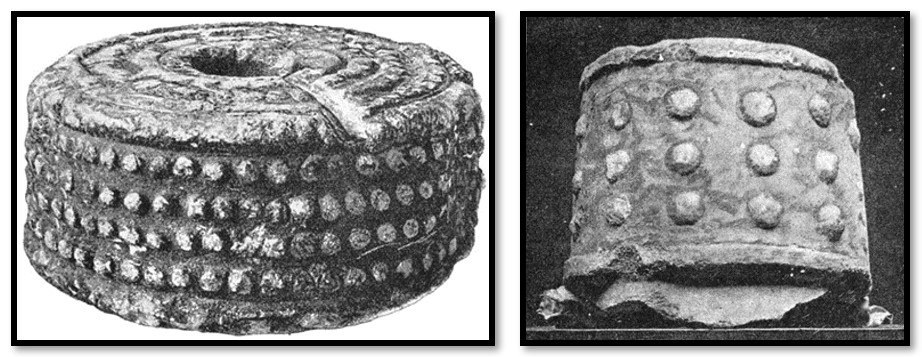

Mabel Bent: Soapstone cylinder from Great Zimbabwe Object from Temple of Paphos, Cyprus

Again there is a constant linking of artefacts from Great Zimbabwe with those of the Phoenicians, although the similarity often seems very superficial, “The use of this extraordinary soapstone find is very obscure. Mr. Hogarth calls my attention to the fact that in the excavations at Paphos, in Cyprus, they found a similar object, similarly decorated, which they put down as Phœnician.”[9]

On the Great Enclosure, “What appeared at first sight to be a true circle eventually proved elliptical – a form of temple found at Marib, the ancient Saba and capital of the Sabaean kingdom in Arabia, and also at the Castle of Nakab al Hajar, also in that country.” Always the constant references to Arabia and the Middle East!

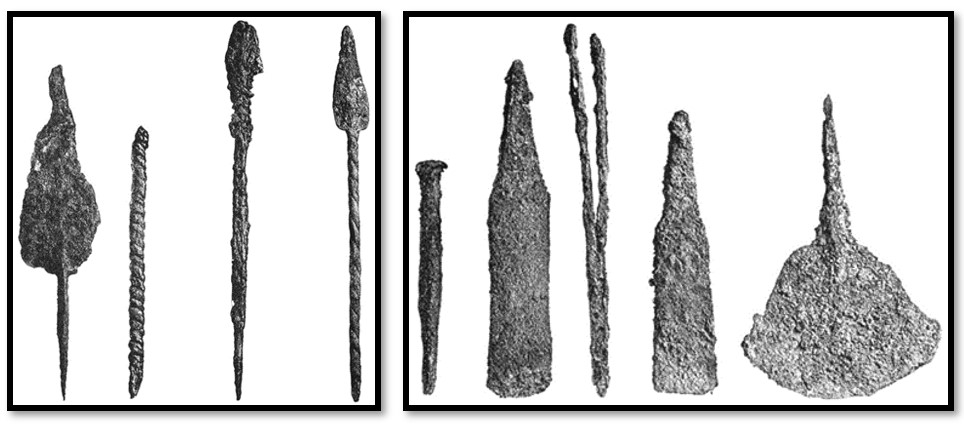

The iron artefacts excavated are acknowledged to be still being manufactured in Mashonaland in 1891, but always the reference to a foreign origin, “the shapes and sizes of arrows and spear-heads correspond very closely to those in use amongst the natives now. As against this it must be said that there are many iron objects amongst our finds which are quite unlike anything which ever came out of a native workshop, and the patterns of the assegai, or spear-head, and arrow are probably of great antiquity, handed down from generation to generation to the present day.”[10]

Mabel Bent: Locally-produced iron weapons and tools

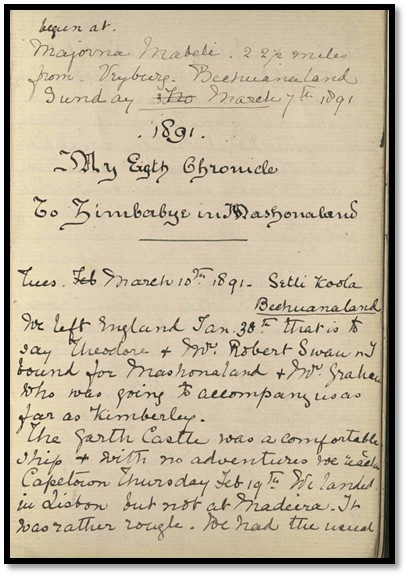

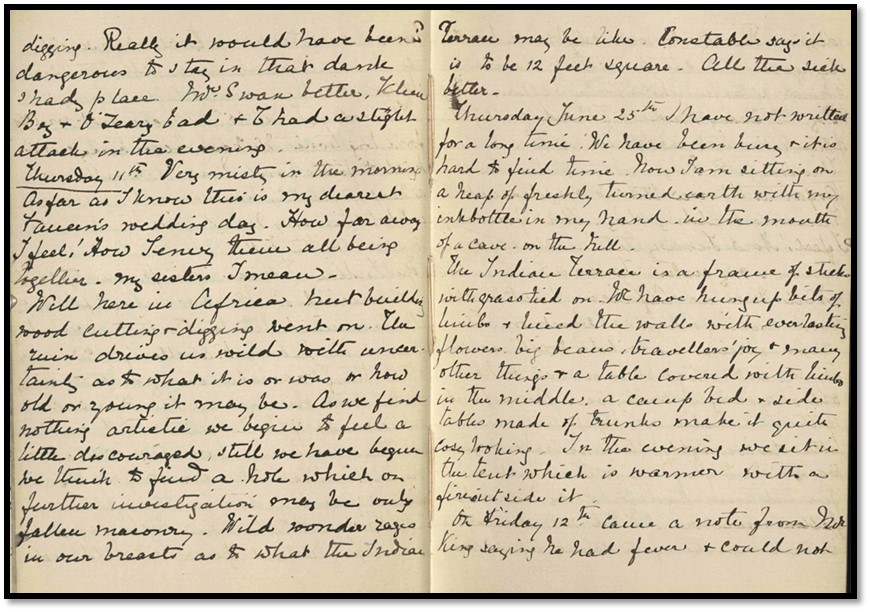

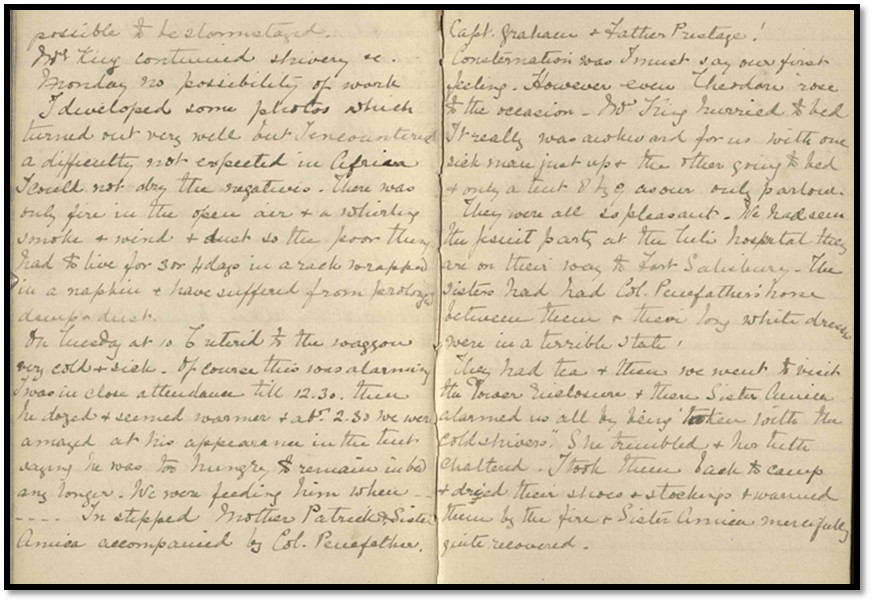

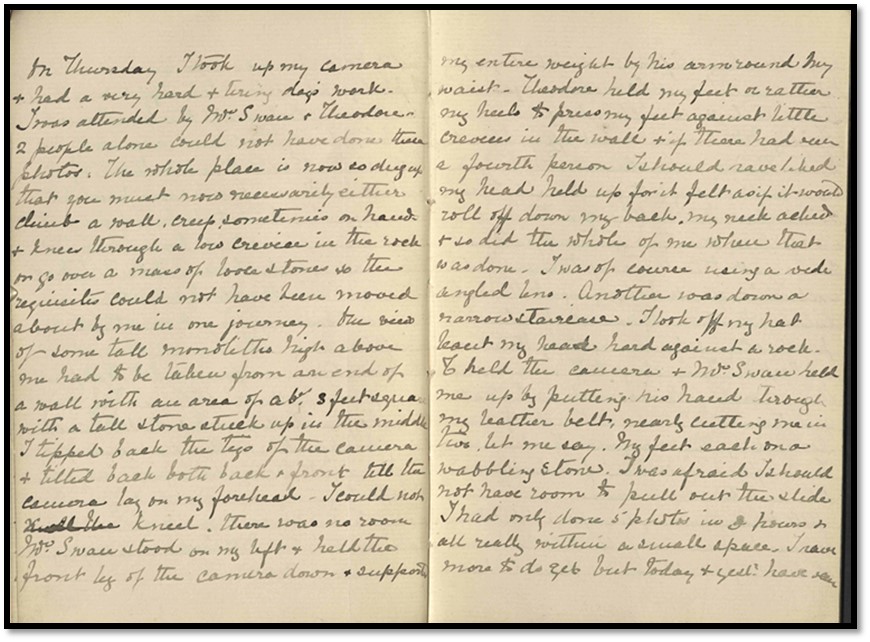

The notebooks written by Mabel Bent

The first page of Mabel’s 1891 Notebook

After a long gap between the 11 to 25 June 1891 Mabel writes, “I have not written for a long time. We have been busy. And it's hard to find time. Now I am sitting on a heap of freshly turned earth with my ink-bottle in my hand in the mouth of a cave on the hill.”

This page records some of Mabel’s difficulties, “I developed some photos which turned out very well but I encountered a difficulty not expected in Africa. I could not dry the negatives. There was only fire in the open and a whirling smoke and wind and dust so the poor things had to live for 3 or 4 days in a sack wrapped in a napkin and have suffered from prolonged damp and dust.”

Here Mabel recalls a trying time taking a photo, “I tipped back the legs of the camera and tilted back both back and front ‘til the camera lay on my forehead. I could not kneel. There was no room. Mr Swan stood on my left and held the front leg of the camera down and supported my entire weight by his arm around my waist. Theodore held my feet or rather my heels and pressed my feet against little crevices in the wall and if there had been a fourth person I should have liked my head held up for I felt as if it would roll off down my back. My neck ached and so did the whole of me when that was done. I was of course using a wide-angled lens.”

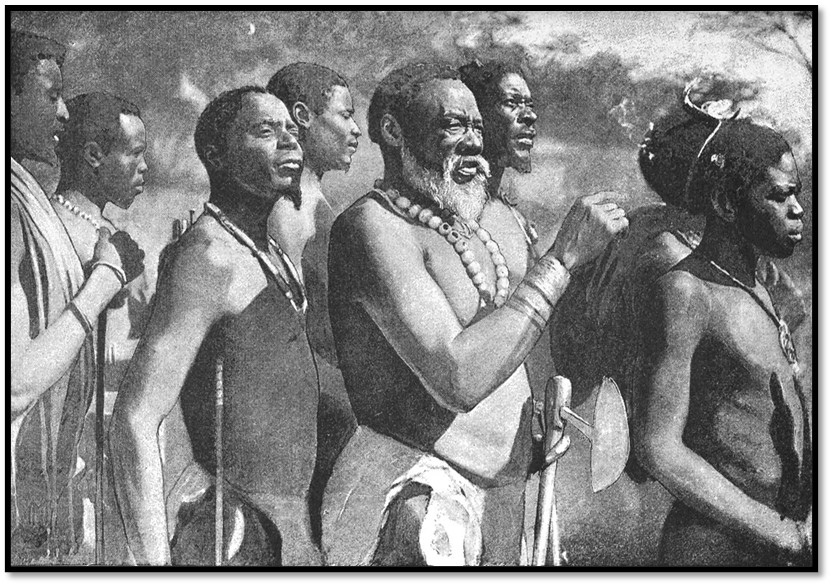

A visit to Chief Mugabe

On 6 August the wagons and their curios set off for Fort Victoria; Theodore, Mabel and Mr Swan set off to visit Chief Mugabe whose kraal was “situated in a glade, buried in trees and vegetation, so that until you are in it you hardly notice the spot.”

Mabel Bent: Chief Mugabe and his councillors

Next day they rode to Cherumbila’s kraal, “the bitter enemy and hereditary foe of our late host” and on the way at a swamp, “one of our horses disappeared in it, all but his head, another rolled entirely over in it, whilst we stood helpless on the bank and fearful of the result, but at length we managed to drag the wretched animals out…”

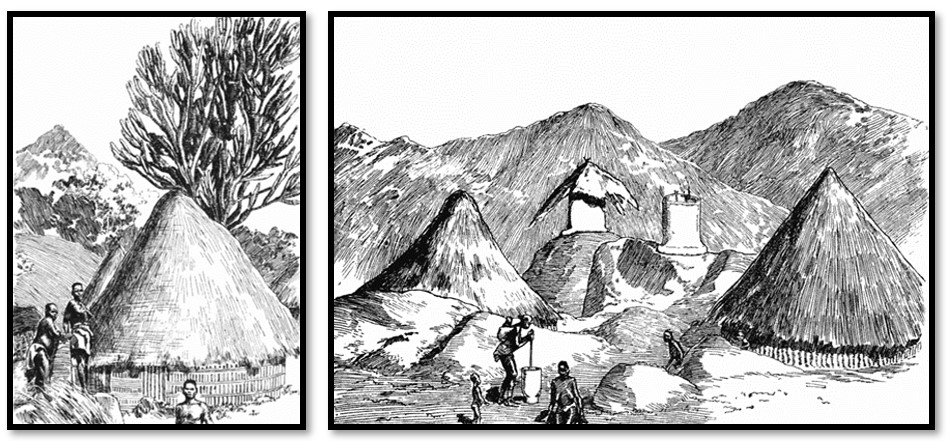

Mabel Bent illustrations: Chief Mugabe and Cherumbila’s kraals

By donkey to the Sabi (Save) River and Matindela (Matendere)

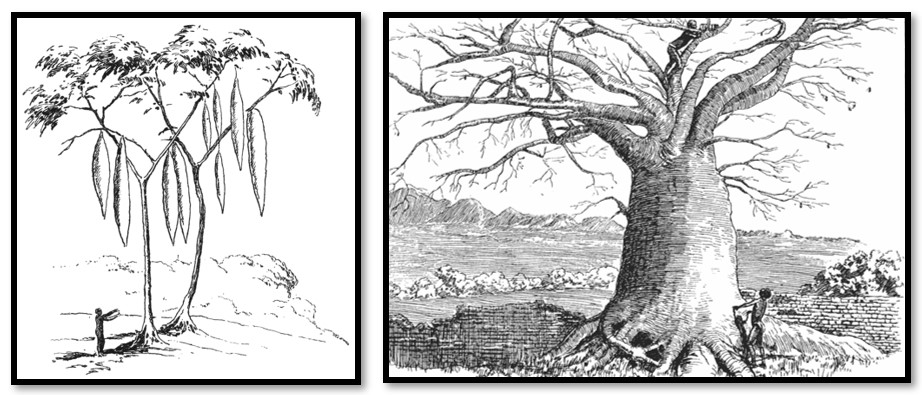

As there were no wagon tracks they borrowed seven donkeys from the BSA Company and initially travelled north to the Makori post station.[11] From here on 14 August Theodore and Mabel, Messrs Swan and King with attendants travelled east passing numerous kraals, the largest belonging to Chief Gutu.[12] “At the entrance to it some tall trees are completely hung with provisions packed away in their long sausage-like bundles—bags of locusts, caterpillars, sweet potatoes, and other delicacies. These trees we henceforth called ‘larder trees,’ and found them at nearly every village.”[13]

Mabel Bent: Larder tree Mabel Bent: Baobab tree at Matendere

Chief Gutu was away, but his kraal appeared prosperous with large fields of tobacco and rice. The nearer they came to the Sabi river, the more varied became the landscape with deep valleys and kopjes, the vegetation grew thicker and the climate hotter. They visited small ruins called Metemo “which formed a link in the great chain of forts stretching northwards” before reaching the Matindela (Matendere) ruins, approximately 112km east of Makori post station.

The route of the Bent's party to Matendere, the Sabi and Fort Charter

Matindela (Matendere)

Theodore writes, “and the countryside (is) almost deserted, ruined villages crowned most of the heights, and the deserted fields and devastation in every direction were lamentable to behold. They were evidences, too, of a fairly recent raid, in which the poor Makalangas had been driven out of their homes and probably carried into slavery.”[14] Gungunyana[15] and the Shangaans were clearly to blame knowing that Lobengula and the amaNdebele had been cut off by the BSA Company and therefore made an opportunistic raid west of the Sabi river. Here the Bent’s tried the acidic taste of cream of tartar of the Baobab trees and bartered for cucumbers, monkey nuts and sweet potatoes.

“Traces of recent life around Matindela were numerous; the valleys had all at one time being ploughed, ruined huts, constructed high up in the trees had served as outlooks for the agriculturalists, bark beehives were in the trees, but the villages were all blackened and burnt, the granaries knocked down and the inhabitants gone, no one knows where.”[16]

Travel to the Sabi (Save) river

From Matendere they travelled north-east to a mountain called Chiburwe which was deserted apart from two old women. “A mile or two from Chiburwe we found a ruined fort of the best period of Zimbabwe work, with courses of great regularity, but much of the wall had been knocked down by the baobab trees which had grown up in it.” These ruins maybe Kagumbudzi and Muchuchu described by Gertrude Caton-Thompson in 1929. Theodore speculates on the Sabi river as a route into the interior. “In ancient times it must be navigable for larger craft, for all African rivers are silting up. There is little doubt but that the ancient builders of the ruins in Mashonaland, the forts and towns between the Zambezi and Limpopo, utilised this stream as the road to and from the coast…”[17]

When they left the Sabi river travelling north-west on a native path it was over 30 miles (48km) before they came across the first inhabited village in the area of Mount Wedza, “and it is from here that the natives of Gambidji’s country get the iron ore which they smelt in their furnaces and convert into tools and weapons.” Their guide to Mtigeza’s (Umtigesa) kraal, “carried with him three large hoes which he had made, and for which he expected to get a goat at the kraal.”

“Around the central mass of rocks is ‘Mtigeza’s head kraal, surrounded by palisades and the rock itself is strongly fortified…and the boast of the people here is that the Matabele have never been able to take their stronghold.”[18]

On 2 September 1891 after three weeks of walking the party reached Fort Charter where they met up with their two wagons.

Camped at the Umfuli (now Mupfure) river

They camped on the banks of the river before travelling the approximately 50km south to Fort Salisbury[19] (now Harare) Only twelve months earlier on the 12 September 1890[20] the Pioneer Column had decided to halt their expedition between the kopje, called by the Mashonas ‘Harari’ and the river Makubisi (Mukuvisi) and to build their base there.

Mabel’s letter addressed home to County Wexford[21]

Headed ‘Umfouli (Umfuli now Mupfure) River 5 September 1891, finished on 9 September at Fort Salisbury

My dearest Faneen & L(Loodleloo), Iva & E(Ethel)[22]

I was in the midst of a letter but implored the cart[23] to wait as I knew it was long since you had news. I wonder if you saw the telegram I sent from Fort Victoria in answer to one to report progress.

Well I will go on where I left off. We dined sitting on our bedding and soon went to bed, pretty tired. The days very hot and the nights sometimes dreadfully cold.[i] It is rather hard on one not having some servant but we had no means of getting one. We meant to take a B.S.A.[C.] man as interpreter, but he was ill and we waited 2 days then took our head man, Meredith,[24] who can talk Zulu, and one of our 9 [local men] could understand him, so we got on very well. We can say a few things now ourselves; so the wagons were in command of Alfred, no. 1 driver, Constable, cook, a black leader [and] no. 2 driver of our wagon, and O’Leary, a man who is having a passage given; he feeding himself (not really though) He has been with us since May, digging at Zimbabwe.

Since Fort Victoria, where a leader and driver left, we have been short of a leader and hoped to get one from Major Browne,[25] who would have been glad to save his food and pay, as he has lost so many oxen, but he is so much behind and we can’t [wait?], so we get on without. A leader is the lowest. He puts on the brake,[26] drags the oxen into the right path, for they have no other guide, and takes it in turns with the other leader to go and herd the oxen when grazing. Two naked [local men], or rather with two little skin aprons apiece, drive the donkeys and horses.

We shall be so sorry to have to sell the latter at Fort Salisbury. No one can catch them so well as I, particularly mine, which races away, but they always come to get bread. We have been to some new large unknown ruins, Matindela, and discovered others of which we could find no name. We must sell the horses if we go down the Pungwe River, because one bite of the tsetse fly[27] would kill them at once and we shall get at least £350 for them. The donkeys do not die till the beginning of the rainy season.

We hear dreadful accounts of how the porters forsake you in the worst place if you do not comply with exorbitant demands. But we have 7 donkeys. It is about 400 miles. At Fort Salisbury we shall sell the wagons for little and the oxen[28] for much and divide our clothes, sell some and carry what is absolutely necessary for the steamer from Beira to the Cape, and buy there, for the clothes, etc., we send down won’t be there in time to meet us.

September 8th [1891] We arrived this morning sending a rider on to ask where we were to outspan, for we are very privileged persons, so we are quite away from the public outspan, which is like a dirty farmyard and between the military and civilian quarters. We arrived neatly dressed and were met by invitations to luncheon and breakfast. Very nice not to have to wait till ours was unpacked. There is very little food here: jam 3/6 a pot, and milk – but you can’t buy it – 4/6; ham 4/6 a lb. We have more ruins to see, but our plans are not made till this afternoon. The camp is on half rations.[29]

We have now settled to go down the Busi,[30] and the latter part, each in our own canoe. We are going first to Matoko’s (Chief Mtoko) then to Makori’s; and to Matoko’s we are to be the bearers of the £40 of presents annually given, so are sure of a very good reception. We are to take a trooper with us and Meredith and Alfred, a driver, as personal cook, a very nice fellow, 10 donkeys and 2 of the Makalankas (Makalakas[31]) we have had for more than a month, besides other carriers.

We are invited to take all our meals at the (Officers) mess – a very substantial money saving now. If it weren’t that we are permitted to draw rations we could not get enough food – no milk or meat. So now our men have a good opportunity of seeing that ‘Wilful waste makes woeful want.’ Dr Harris[32], who is head here now, is much pleased with Mr. Swan’s[33] beautifully made maps. Well you see that we are doing well, but alas! When the oxen came in this evening one has lung sickness, so we don’t mean to let that be known[34] and hope to sell the others tomorrow. At the mouth of the Busi we shall go down to the Cape to see the library there and call in Lisbon on the way and hope to be home the beginning of December. There are no ladies here, but one or two traders’ wives and the nuns. How wonderful it is how the Jesuits get in everywhere…

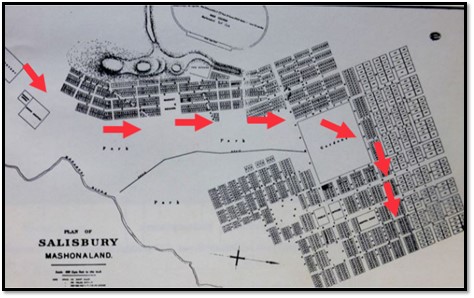

Tuesday, September 8th [1891] We reached Fort Salisbury about 8 o’clock a.m. A man was sent on, riding, to enquire where we were to stop, for we hoped to be spared from the public outspan. We thought we should never arrive. We were half dressed and I was wrapped in a cloak. We drove all through the trading part, which is very extensive and consists of round huts, a few square houses being built, wagons and tents of all sorts, and booths and bowers grouped round a long, low, wooded hill. Then through the camp and past the fort and on to the civilian part and Dr Harris said we were to outspan in that neighbourhood – the hospital and nuns’ dwellings being beyond.

Plan of Salisbury in 1891 and the Bent’s route to their camping place

Before we had stopped, we were greeted by Dr Harris and Captain Nesbitt[35] and we and Mr Swan were invited to take our meals at their mess during our stay. This invitation is of great monetary benefit to us, besides we could not get the food even if we did pay for it. Provisions are frightfully dear and scarce. Sugar 3/- a lb, milk 5/6 a tin, jam 4/6 a lb, ham 4/6 a lb, and everything is in proportion. A pair of common hinges 7/-, 1⁄4 lb of tin tacks 11/6, and 1 lb of paint 35/-. As for meat, it is very hard to get, and a worn out ox just crawled up in a wagon is really so tough that one can’t get ones teeth through it, and those we left in our camp got none…

After breakfast we began in real earnest sorting our baggage; some for England via Cape Town; 2 to go down the Busi with us and be sent by B.S.A. wagons to Umtali’s to meet us; 3 to go to Matoko’s; 4 to be sold; 5 to take to the Mazoe River. The bucksail[36] was made into a tent for packing, but we were very much impeded and had to give up at times on account of the ferocious wind which raged all the time of our stay and brought layers of dirt into the baggage. All our white men sought places and all found them. Mr King is to open a store for the Co. at the Mazoe River. We stayed till Tuesday morning. We saw a great many friends.

Two days I had tea with the nuns who also came several times to see us.[37] Mr Stokes also, and an old friend of Mr Swan’s, Mr Macfarlane. Mr Swan and I had tea in both these huts. Major Browne had walked in the last 30 miles and we had visits in our tent all day. One night (Thursday, 10 September 1891] we dined at the officers mess. They had made the dinner table so pretty with Mr Coope’s puggaree, yellow silk, and ostrich feathers. The fatted calf had died and was served up in 6 quite different ways: cutlets, tongue, roast, pie, and 2 others. In the dining room is a hat rack – 6 rhinoceros horns…

Constable, our cook at (Great) Zimbabwe, was engaged by Dr Harris for the civilian mess. He is abominable to us. Instead of coming forward like an honest man and counting out our enamelled iron and kitchen things, we have to wring them out of him cup by cup. When we ask for things, he says they are gone to the auctioneer, but the list shows the contrary. The last day he kept out of the way and on Tuesday morning, though we were up at dawn, he had already cleared out. I suppose when we get back tomorrow evening that there will be a row. The auction is for Saturday.

Besides our own affairs, there has been on last Saturday the First Annual Dinner on Occupation Day. Theodore was invited. The Pioneers hate Dr Harris and Major Tye. The Chairman, Mr Bird, made the rudest of speeches which Dr Harris ably responded to and most pluckily.[38] The Pioneers had many grievances but some must have been trivial indeed. One of them was that a notice was put up at Zimbabwe forbidding anyone to remove antiquities. No such notice was put up, yet more than once it was complained of and one man said he had seen it. They managed to make Dr Harris tell a lie for the pleasure of confounding him. When he said he had had official news from Cape Town that Mr Rhodes was coming to Tuli, they told him it was a lie for he was coming by the Pungwe, they having concealed the news from Tuesday to Saturday on purpose…

Saturday 19 [September, 1891] Our (auction) sale took place this morning but we do not know the result quite yet. Some of the things seem to have gone high enough: whisky £2 a bottle and brandy £3. We afterwards were quite satisfied. Some people certainly got good bargains, but then so did we: A [quart] of spirits of wine £1.10; 1 doz. 1⁄2 [bottles] champagne £1.5….’

In a letter published in The Times on 14 Jamuary 1892, Bent refers to the caravan of 15 cases of acquisitions he is sending home, many of which are in the British Museum today: “I may add that 15 cases of our finds are now on their way from the interior, also a large collection of native objects, which I hope may arrive in England almost as soon as we do…”

A visit to the Mazoe (Mazowe) Valley

They left Fort Salisbury on 15 September taking three donkeys with bedding and supplies. Mount Hampden is described as “miserably disappointing” and about as high as Box Hill in Surrey! The Tatagora Valley however was at its finest with the Msasa trees in their finery and is compared with a “pretty Norwegian valley.”

Mabel Bent; Mashona pot Mashona ruin in the Mazoe Valley

Theodore writes, “The first set of old workings which we visited was only a few hundred yards from Mr Fleming's huts and consisted of rows of vertical shafts, now filled up with rubbish, sunk along the edge of the auriferous reef, and presumably, from instances we saw later, communicating with one another by horizontal shafts below. We also saw several instances of sloping and horizontal shafts, all pointing to considerable engineering skill…One vertical shaft had been cleared out by Mr Fleming's workmen and it was fifty-five feet deep. Down this we went with considerable difficulty and saw for ourselves the ancient tool marks and the smaller horizontal shafts which connected the various holes bored into the gold-bearing quartz.”[39]

Of the Chisvingo ruin he states, “It was obviously erected as a fort to protect the miners of the district and is a link to the chain of evidence which connects the Zimbabwean ruins with the old working scattered over the country.”[40]

He does point out that fragments of Chinese porcelain and old Delft pottery have been found near the Jumbo Mine thereby confirming the evidence of the Portuguese trading post of Dambarare.[41] “…and no doubt many of the large Venetian beads, centuries old, which we saw and obtained specimens of from the Makalangas in the neighbourhood of Zimbabwe were barter goods…”[42]

The Bents are requested to take £40 of presents from the BSA Company to Chief Mtoko (Mutoko)

The Chief lived about 120 miles (193km) north-east of Salisbury and as there were no roads they would need to sell their wagons and oxen and travel with horses and donkeys and bearers. They learnt that although Chief Mtoko had a treaty with the BSA Company there had been no official dealings to date.

Salisbury was left behind on 23 September, the Bent’s accompanied by Swan and two white men, two native bearers, three horses, eleven donkeys and an interpreter to follow. They reached Chief Kunzi’s (Kunzwi) kraal[43] where they recruited additional bearers. Here they watched iron ore being smelted in a furnace with blow-pipes and bought a porcupine quill of gold. The nearer they were to M’toko’s kraal, the more scattered the kraals became as they were now out of reach of amaNdebele raids and Gouveia, the Goanese who lived near Gorongoza Mountain in present-day Mozambique had once raided but was beaten in battle by Mtoko’s father.

The chief’s presents included an entire uniform of the Cape Yeomanry, helmet and horsehair plumes, knives, looking glasses, handkerchiefs, shirts, beads and yards of cloth. They asked and were permitted to speak to the priest of the lion god, the Mondoro (Mhondoro) who was uncle to the chief and “who is reported to be even stronger than the chief.”

Theodore writes of their encounter at Lutzi, “Then we questioned him about the lion god, and he gave us to understand that the Mondoro or lion god of M’toko’s country is a sort of spiritual lion which only appears in time of danger, and fights for the men of M’toko. All good men of the tribe, when they die, pass into the lion form and reappear to fight for their friends. It is quite clear that these savages entertain a firm belief in an after-life and a spiritual world and worship their ancestors as spiritual intercessors between them and the vague Muali (Mwari) or God who lives in Heaven.”[44]

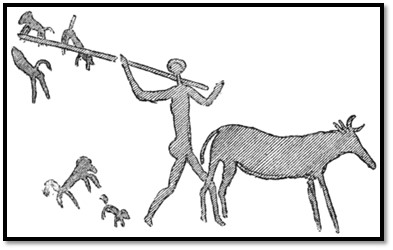

Theodore Bent: Bushman[45] (San Khoisan) drawings near Chief Mtoko’s kraal

On leaving Mtoko’s they enter the territory of Chief Mangwendi, “the two neighbours, like well-matched dogs, growl but do not come to close quarters.” In describing the numerous fortified kraals, Theodore says, “Here we see none of the even courses, the massive workmanship and the evidence of years of toil displayed by the more ancient ruins; the walls are low, narrow and uneven.” Theodore comes down on the builders being local people, “Are we to suppose an intermediate race between the inhabitants of Zimbabwe and the present race who built these ruins? Or are we to imagine them to be the work of the Makalangas themselves in the more flourishing days of the Monomotapa rule? I am decidedly myself of the latter opinion.”

On their travels Bent mentions reaching Chipunza’s kraal, now known as Zvipadze.[46]

Mabel Bent: Chipunza’s kraal

“In the afternoon we went to pay a visit to the chief, who received us in a sort of inner fortress surrounded by a wall, through an opening in which, about three feet high, and covered with large slabs of stone, we had to creep…He sat surrounded by his councillors, and we all set to work to clap hands vigorously…Chipunza has another name, Chipadzi.” [47]

From Chipunza’s kraal a short ride of a few hours brought them to Makoni’s kraal, but they had to leave before meeting the chief. “Almost immediately on leaving Makoni’s our road began to descend, and we entered upon a series of richly wooded gorges, flanked by gigantic granite cliffs”[48] and four days after leaving Makoni’s they crossed the Odzi river.

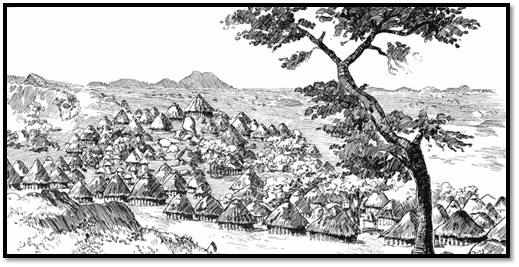

Chief Mutasa’s kraal on Binga Guru Mountain

A ride of twelve miles brought them next day to the kraal of ’Mtasa (Mutasa) the most powerful of all the Manica chiefs. “Mtasa’s kraal is quite one of the most extraordinary ones we had yet visited, being a nest of separate villages, each surrounded by its own stockade, hidden away amongst granite boulders beneath the shade of a lofty mountain. It is almost impossible to form any idea of the exact extent of this place, so hidden away is it amongst trees and rocks, and so intricate are its approaches; but, if report tells truly, which it does not always do in South Africa, it is one of the largest native centres in the country…Certainly no kraal we had as yet visited enjoys such excellent views as ’Mtasa’s. The huts here are large and roomy, at the side they have two tall decorated posts to support shelves for their domestic produce; most of them have two doors, and with the dense shade of many trees above them they are exceedingly picturesque.”[49]

Chief Mutasa had been at the apex of the quarrel between the BSA Company and the Portuguese early in 1891 and the Bent’s were forbidden to see the old chief and there was no welcome from the people. So they left and crossed a slippery drift across the Odzani river about halfway to the BSA Company Police camp at Fort Hill that was reached on 24 October, a month after leaving Fort Salisbury.

They reach Fort Hill (the first Umtali) in the Penhalonga Valley

At Fort Hill in the Penhalonga Valley and before crossing ‘the divide’ into Portuguese territory the Bent’s enjoy a few days’ rest. At the time it was called Umtali[50] from the river that flows below it. Theodore says, “It was, when we were there, a scattered community of huts, now brought together in a ‘township’ at a more favourable spot, (the Methodist Mission) about five miles distant from the former site, which township the British South Africa Company hope to call Manica, and to make it the capital of that portion of Manicaland which they so dexterously, to use an Afrikander term, ‘jumped’ from the Portuguese. Of all their camps Umtali was the most favourably situated that we visited, enjoying delicious air, an immunity from swamps and fevers, lovely views, and many flowers. On the ridge, where the camp huts stood exposed to the violent and prevailing blasts of the south-east winds, which descend in furious gusts from the surrounding mountains, stood also the guns taken from the Portuguese, nine in all, and presenting a formidable enough appearance, until we learnt that they were useless then, for the pins were abstracted before capture. Far away on the hill slopes were the huts of the original settlers; the bishop’s palace likewise, a daub hut standing in the midst of a goodly mission farm. The hospital, with the sisters’ huts, crowned another eminence, and the newly made fort stood on the highest point, from which glorious views could be obtained over the sea of Manica mountains, the rich red soil and green vegetation, so pleasant a change to the eye after the everlasting grey granite kopjes of Mashonaland and its uniform vegetation.”

At Fort Hill the Bent’s met the three British nurses who had arrived on 1 July 1891 having promised Bishop Knight-Bruce their assistance in setting up a mission hospital in Mashonaland, Rosanna Blennerhassett,[51] Lucy Sleeman, and Beryl Welby. In their book they, in turn, describe the Bent’s brief stay.

“We had hardly shaken hands when Mrs Bent asked us what we thought of her dress. This was a difficult question to answer. Mrs Bent's costume consisted of an ordinary print blouse, worn over obvious stays; a woollen kilt, reaching to just below her knees; knickerbockers; top boots and a pith helmet, which gave its wearer something of the air of a Britannia who had exchanged the rest of her garments with a scarecrow!”[52]

On their conversations with Theodore, “He was fresh from those strange Mashonaland ruins which have given rise to so much conjecture. Mr Bent supposed them to be extremely ancient. He told us that, without consulting the archives at Lisbon, he could not give a decided opinion on their origin. At that time he seemed to believe them to be the ruins of a temple and fortress. There, he thought, weird rights had been solemnised and fierce battles fought.

Mr Selous differed entirely from this view. He believes the ruins to be comparatively modern, and the remains of native work… [He] is probably the best authority on the subject, knowing Africa as thoroughly as he does, and being able to converse with the native as easily as with an Englishman, whilst Mr Bent could neither speak nor understand the language. But Mr Bent appeared certain that the Portuguese only could throw light on the problem. He said that the Portuguese had certainly been all over the country and that a Portuguese archaeologist who would devote himself to the subject would find the archives, of Lisbon, and very likely of other old cities, rich in most interesting materials.

A few days later, the Bent’s rode away to Masse-Kesse (Macequece now Manica) en route to the coast. We saw them go with something of a pang. They would probably be our last visitors. When the rainy season sets in thoroughly, Umtali would be like a besieged city and its inhabitants cut off from all communications with the outer world.”[53]

Theodore writes, “Crossing a stream below the fort, we found ourselves amidst a collection of circular daub huts and stores, on either side of what a facetious butcher, who dealt largely in tough old transport oxen, had termed in his advertisement ‘Main Street.’ Here you might pay enormous prices for the barest necessities of life, and drink at old Angus’s bar a glass of whisky at the same price you could get a bottle for in England. Scotch is the prevailing accent here, and I think the greatest gainers out of Mashonaland, in the first year of its existence, were those canny traders who loaded waggons with jams and drink and sold them at fabulous prices to hungry troopers and thirsty prospectors. Old Angus was a typical specimen of this class, a sandy-haired little Scotchman, well up in colonial ways, who kept two huts, in one of which eating, drinking, and gossip were always to be found; whilst the other was divided into three bare cells and called an hotel.[54]

Journey to the coast at Beira

Porters were impossible to get for the journey to the Pungwe river, so a two-wheeled cart was constructed for the baggage to be drawn with their eleven mules. The cart went to Massi-Kessi (Macequece, now Manica) by the wagon road taking three or four days and the others climbed “the divide” Mabel on a horse and reached Massi-Kessi by evening. Even in 1891 Theodore writes the mountainside in the Revue river valley was honeycombed with pits that had been worked for gold.

Around the fort at Massi-Kessi he writes fragments of Nankin porcelain were to be found; remnants from the Portuguese trading post in the sixteenth century. Commandant Béthencourt was a gracious host and they rested for three days before the arduous journey by foot to Mapanda’s, the highest navigable part of the Pungwe river and then by the smallest steamer, the Agnes,[55] to the sea at Beira for their voyage home to England, via Lisbon.

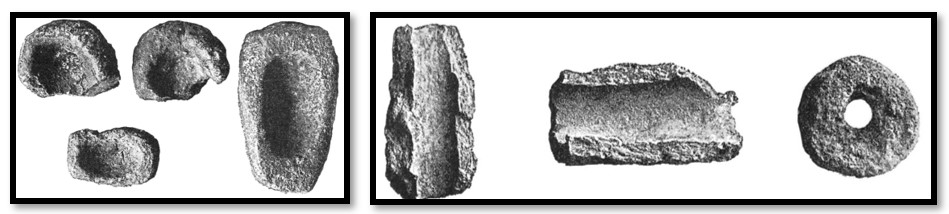

The Bent’s arrive back in England for a lecture at the Royal Geographical Society

The Bent’s travelled home to London via Madeira and Lisbon arriving at the end of January 1892. Theodore’s priority was the talk he was giving to the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) on 24 February. The RGS publicity stated: “The programme for the coming winter season of the Royal Geographical Society is now partly arranged. As the Society depends for so many of its attractions on wandering stars, whose comings and goings are always more or less uncertain, an entire programme is never ready at the opening of the season, but already three or four interesting evenings are promised… But certainly one of the most interesting and at the same time most popular evenings will be that devoted to the account given by Mr Theodore Bent of his journey to Zimbabye and his study of the strange ruins which he went out to examine. I may say, by the way, that news has just been received from Mr Bent that he has discovered unmistakeable signs of the working of the old mines in the vicinity of Zimbabye many centuries ago. Crucibles and other articles connected with the pursuit of the precious metal have been found, and it is quite clear from the scraps of information that reach us that Mr. Bent’s story, when it is told in detail by himself, will be both fascinating and instructive.”

Mabel Bent: crucibles for gold smelting and furnace pipes (tuyeres) excavated at Great Zimbabwe

The lecture was a great success with the RGS President, Sir Mountstuart Elphinstone Grant Duff saying, “This is very much the largest meeting that we have had since the great gathering to welcome Stanley in the Albert Hall [5 May 1890]. You came expecting a great deal from Mr Bent; you have not been disappointed, and I know that I have your mandate to return your most sincere thanks to him and also to Mrs Bent, who was so excellent an assistant to him, and to whom we owe a great deal of the pleasure of this evening, for I understand Mrs Bent did all the photographs.”

The exhibition of Great Zimbabwe artefacts at the Bent’s home in April 1892

The Folkestone Chronicle and Advertiser reported on Saturday 9 April 1892 of the exhibition held at the Bent’s home, 13 Great Cumberland Place, London, “Mr and Mrs Theodore Bent’s party was successful and interesting. Her sister, Mrs Hobson, and a few intimate friends assisted Mr Bent and his fellow-traveller, Mr Swan, in explaining the relics to the learned and unlearned, to the latter of whom the trophies from the Great Zimbabwe might otherwise have seemed just so many rudely-carved old stones, instead of being silent witnesses of the ancient civilisation and worship traced out by Mr Bent in the wonderful walled fortresses of Central Africa, carrying back one’s thoughts to that heroine of ancient history, the Queen of Sheba. Even the most un-archaeological were impressed by the fact that there is nothing like these remains in the British Museum.’

The Bent’s become celebrities

Their journey to Great Zimbabwe attracted much public interest in Britain, David Brisch writes on their website that at least 34 regional newspapers recorded their arrival at Fort Salisbury and that the couple’s ‘treasures’ from Great Zimbabwe were on their way to London, and eventually the British Museum,[56] where most of the ethnographic materials are now stored. The iconic soapstone birds however went back to Cecil Rhodes and Cape Town.[57]

Three of the eight known soapstone birds on pedestals from Great Zimbabwe

The Atheneum reported, “Mr Theodore Bent has brought home with him from Mashonaland an exceedingly interesting collection of objects from the ruins of the ancient Zimbabwe, which he went out to examine last spring at the joint expense of the Royal Geographical Society and the British South Africa Company. These he has mean time arranged in his house in Great Cumberland Street. Later on, we understand, they will form the nucleus of a special African exhibition of a much more comprehensive character. The objects which first strike the visitor to Mr Bent’s collection are the four bird forms perched on the top of slender soapstone monoliths beautifully smooth and polished…’

The Illustrated London News observed, The expedition in Makalangaland from which Mr J. Theodore Bent has just returned, and the results of which he has embodied in a paper read recently before the Royal Geographical Society is likely to open up a rich and well stored garner to the archaeologist. Mr Bent, with his wife, was away from England exactly a year. During his journey…he not only thoroughly explored the great Zimbabwe ruins, but also trod parts of the country hitherto untrod by Europeans…[He] is not unwilling to talk freely of his remarkable journey, and a representative of the Illustrated London News called upon him last week, and learned some interesting facts…“I was sent out, you may know,” said Mr. Bent, “by the South African Company and by the Royal Geographical Society…to examine and excavate the great Zimbabwe ruin… I was accompanied by Mrs Bent, who endured with great heroism the hardships of the journey…Our principal treasures we found in a corner of the fortress now used by a petty chief on the hill as a cattle kraal. Of these some of the most perfect are the birds used to decorate the outer wall of the temple…In M’toko’s country, it would, perhaps, amuse you to hear that Mrs Bent created undisguised astonishment and alarm. Here few white men have penetrated as yet, and at every village my wife had to take down her hair and show its length, and the report of this extraordinary possession travelled so much faster than we did that on our arrival in many villages we were greeted with cries of Hair! Hair!”’

Theodore’s book ‘The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland’ is published in November 1892

Within nine months the first edition of his book had been written, printed and lavishly bound. It proved popular and soon sold out. Gerald Brisch writes its adventurousness, topicality, and large number of illustrations and photographs made it one of the books of the year. A new (and cheaper) edition was prepared for August 1893, with subsequent reprints in both January 1895 and 1896, and a final edition in March 1902.

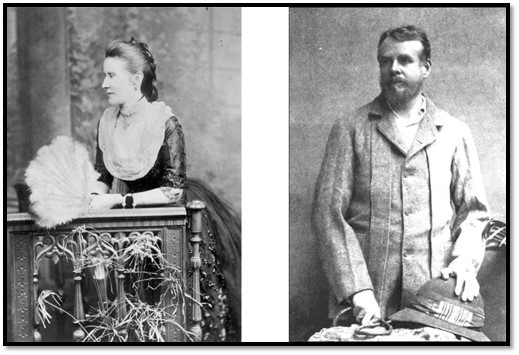

Mabel Virginia Anna Bent and Theodore Bent

James Theodore Bent was born on 30 March 1852 in Liverpool where his uncle, Sir John Bent was Lord Mayor in 1850/1. The family wealth was based on pottery developed by his grandfather who established factories at Newcastle-under-Lyme, Shrewsbury, Macclesfield and Liverpool that were managed by his four sons. His father James Bent (1807-1876) married Margaret Eleanor (c. 1811-1873) née Baildon Lamberts, who were also a wealthy family and young Theodore had a privileged upbringing being schooled at Repton public school in Derbyshire and from there to Wadham College, Oxford (c. 1873-75), where he graduated with a BA in Modern History and later a MA. He was a student at Lincoln’s Inn but never went on to become a barrister. His real interests lay in travel, social history and archaeology and is described as being ‘fair-haired, blue-eyed, short and stocky.’

He joined the Hellenic Society in 1883 and in 1885 was elected a member of the Council, remaining as such until his death in 1897. On 1 July 1886 he was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries and a Fellow of the Royal Geographic Society on 16 June 1890. He was elected Member of the Anthropological Institute at its meeting on 21 June 1892 (see, Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, v.22, 1893, p. 174) following his Great Zimbabwe excavation.

Mabel wrote she met Theodore in Norway probably in the early 1870’s and they married on 2 August 1877. Both were of independent financial means and after honeymooning in Norway, they soon embarked upon their travels abroad. Their first trip was to Italy and in 1879 Theodore published a book entitled A Freak of Freedom: or the Republic of San Marino. In 1880 he published Genoa: How the Republic Rose and Fell, followed in 1882 by The Life of Giuseppe Garibaldi.

Their journeys around the Cyclades followed between 1883-5 with the publication of The Cyclades or Life Among the Insular Greeks in 1885. In the succeeding years they explored the more easterly islands of the Aegean Sea, many of which were then Turkish, as well as the Aegean coast of Turkey.

In 1889 they visited the Bahrain islands of the Persian Gulf. Their trip in 1891 to Africa resulted in Theodore’s best-seller, The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland, published in 1892. Following a visit to Ethiopia he wrote The Sacred City of the Ethiopians that was first published in 1893. In their final years of travel they were on the southern Arabian Peninsula and the African coast of the Red Sea.

On the island of Socotra, in the Gulf of Aden, Theodore caught malaria. They managed to get back home to London, but Theodore died four days later on 5 May 1897 aged 45 years and was buried at St Mary the Virgin Church, in Theydon Bois, Essex.

E.W. Bradbrook, in the Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 27 (1898), pp. 552-553) wrote, “In the death of Mr J. Theodore Bent, the Institute has to deplore the early termination of a life of remarkable achievement and high promise. An intrepid explorer and a ripe scholar, Mr Bent was also a man of singularly attractive and engaging character…”

Colonel Sir Thomas H. Holdich, K.C.I.E., C.B., R.E., the Superintendent of Frontier Surveys in British India, said in a tribute to the Royal Geographical Society, “Theodore Bent has left the fields of Arabia and Africa; Elias will no more tread the steppes of Central Asia…”

The Royal Geographical Society’s stressed Bent’s good nature, “Mr. Bent’s kindly and genial nature had endeared him to a wide circle of friends, by whom his loss will be keenly felt…”

![]()

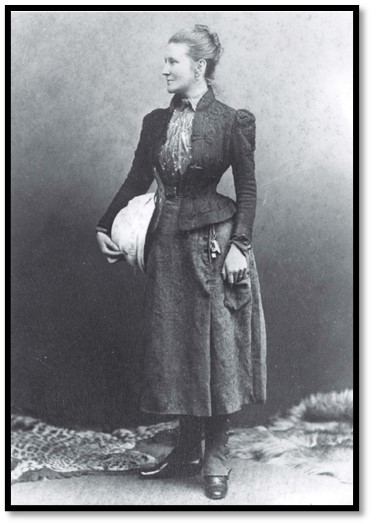

Mabel Bent, possibly taken in Cape Town in 1891. “Mrs Theodore Bent, another woman whose appearance suggests rather the drawing room than the trackless desert, has outstripped many a male explorer in her daring and her defiance of fatigue and danger… Mrs Bent, it may be interesting to add, travels in a ‘tweed coat and skirt coming well over the knees, breeches, gaiters, and shoes.’ She wears a pith hat and always sleeps in a hammock.”[58]

Mabel Virginia Anna (née Hall-Dare) was born in County Meath in Ireland on 28 January 1847, daughter of Robert Westley Hall-Dare and Frances Catherine Anna (née Lambart) she was descended from a line of Anglo-Irish aristocracy with strong, historic ties to Essex, but Mabel’s father relocated to Ireland and established their home at Newtownbarry House in County Wexford.

Mabel’s home: Newtownbarry House

Mabel is described as being "Five feet eight inches tall, a green-eyed, sturdy redhead – striking in her photographs – her flaming, plaited hair was often the subject of native wonder. Outgoing and confident, she was as happy taking fences at full gallop in her native Wexford as she was dining with British ambassadors in Cairo or Constantinople.”

Women were not permitted to become Fellows of the RGS until 1913 and probably explains why she left her notebooks to the Hellenic Society where she was a member for over 30 years and not the RGS.

David Brisch writes that Mabel never really recovered from the loss of Theodore, her travel companion and her raison d’être. She made journey’s after his death but found Egypt ‘lonely’ and ‘useless.’ She finished and published the book of their final journey Southern Arabia in 1900 followed by A Patience Pocket Book in 1904 and Anglo-Saxons from Palestine: or the Imperial mystery of the lost tribes in 1908.

Mabel kept travelling well into her 70’s, particularly to Jerusalem and the Holy Land. Her great work and legacy, Southern Arabia, in the preface illustrates her grief at losing Theodore, “If my fellow-traveller had lived, he intended to have put together in book form such information as we had gathered about Southern Arabia. Now, as he died four days after our return from our last journey there, I have had to undertake the task myself. It has been very sad to me…” The book’s final two sentences read, “This is all I can write about this journey. It would have been better told, but that I only am left to tell it.”

She lived at their London home, 13 Great Cumberland Place, where her husband Theodore Bent, died in 1897, until her own death in 1929.

Mabel Bent’s contributions to the Great Zimbabwe excavation in 1891 include:

- Photography: As the expedition's photographer, Mabel documented the ruins and artifacts through her photographs. These images were later used to produce illustrations for Theodore Bent's books and articles, as well as lantern slides for his lectures at the Royal Geographical Society.

- Record-keeping: Mabel kept detailed notebooks of their journeys, including the expedition to Mashonaland that provided valuable information later used in lectures and the book The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland.

- Mabel recorded significant ethnological information about the native inhabitants of Mashonaland that were used by Theodore in his writings.

- She provided the expeditions’ medical aid from the medical supplies they carried on their journeys and attempted to provide medical aid to local people they encountered.

- Support and collaboration: As Theodore's wife and travel companion, Mabel provided support and collaboration to their Southern African expedition that contributed to its overall success.

- After Theodore's death in 1897, Mabel completed and published their monograph "Southern Arabia" in 1900, which included information from their various expeditions.

- While Mabel's contributions were significant, it's important to note that her work was often overshadowed by her husband's in the historical record, reflecting the gender biases of the Victorian period.

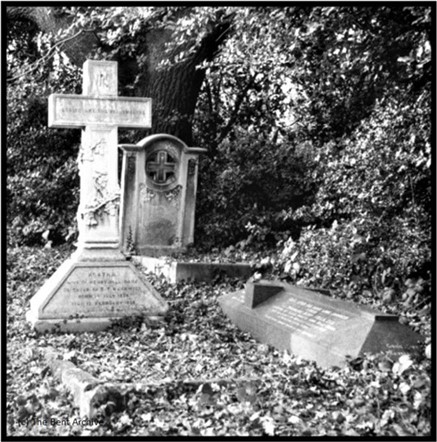

Mabel died on 3 July 1929, aged 83 and was buried alongside Theodore at Theydon Bois. They never had children and she never remarried. Brisch writes she spent the last 32 years of her life alone, perhaps living up to the motto on her family coat-of-arms – ‘Loyauté sans tache’ – ‘Unsullied loyalty.’

Theodore and Mabel’s graves at St Mary’s, Theydon Bois, Essex

The Illustrated London News book review of Southern Arabia provides a perfect eulogy, “The vivacity of her feminine humour, the keen observation of amusing little details, the lively recollection of droll anecdotes, and the brave wife’s spirit of comradeship in their frequent adventurous travels, grace with a peculiar charm the instructive revelation of much rare fresh learning which concerns the lore of historic antiquity, as well as the present condition of territories yet imperfectly known… That lady’s courage and high spirit, the tact and cleverness with which she managed to bear her position as the only female traveller, must have been a great help to her conjugal partner. This book is her memorial of him, acceptable to many readers who condole with her irreparable bereavement.”

Together Theodore and Mabel Bent were intrepid explorers who faced danger and hardship with great courage on their travels to far-off places.

References

G. Brisch. The website Theodore and Mabel Bent http://tambent.com/african-tour-2/

G. Brisch. The Travel Chronicles of Mrs J. Theodore Bent. Volume II: The African Journeys. Archaeopress, 2012

J. T. Bent. The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland. Books of Rhodesia Gold Series Volume 5, Bulawayo 1969

The Project Gutenberg eBook of The ruined cities of Mashonaland: Being a record of excavation and exploration in 1891. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/69067/pg69067-images.html

[1] The Pioneer Column of the British South Africa Company only reached the site of Fort Salisbury on 12 September 1890; this date was celebrated from 1920 as Pioneers' Day. At 10 am on 13 September 1890, a full dress parade of the column was held, the seven-pounder gun fired a royal salute and Canon Balfour said a prayer and then Lieutenant Edward Tyndale-Biscoe hoisted the British flag

[2] Philips, a long-time trader at Gubulawayo in Matabeleland says “When I was at the ruins in October 1871 I heard there were two white men close to the ruins of Zimbabye in a destitute condition. One of them was Mauch, with an American named Adam Kinders (Render)” Local Africans were very reluctant to take Europeans to Great Zimbabwe; Philips hints that he ‘was at the ruins’ but most accounts believe he never actually saw Great Zimbabwe itself, although he was in their vicinity

[3] Bent was a Committee member for the Anthropological and Geographical Sections of the British Association for the Advancement of Science

[4] Cecil Rhodes had become Prime Minister of the Cape Colony in 1890 and the dinner would have been at his official residence, Groote Schuur which he had leased in 1891

[5] Their trekking by two ox-wagons had started at Vryburg on 6 March 1891

[6] The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland, P69

[7] Ibid, P84

[8] The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland, P116

[9] Ibid, P205

[10] Ibid, P211

[11] Makori “post station lay about one mile from our camping-ground; the two huts where the B.S.A. men lived were situated on a rocky kopje full of caves, in one of which their horse was stabled, and from the top of the rock an extensive view was gained over the high plateau, well wooded just here and studded with rocks of fantastic shape.” For a detailed description see the article Postal service in 1890 – 1892; the post-stations from Fort Tuli to Salisbury under Masvingo Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[12] Gutu’s kraal was approximately 45km due east of Makori post station

[13] The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland, P257-8

[14] The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland, P263

[15] Gungunyana was the last king of Gaza, now part of Mozambique reigning from 1884 to 1895

[16] For a description of Matendere see the article Matendere Monument under Manicaland Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[17] The ruined cities of Mashonaland, P269

[18] The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland, P273

[19] Fort Salisbury was named after Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (1830-1903) then the British Prime Minister

[20] F. C. Selous wrote, “It is a matter of history that on the 11th of September 1890 the British flag was hoisted at Fort Salisbury, on the banks of the Makubisi (Mukuvisi) river, and the expedition to Mashunaland thus satisfactorily brought to an end.” Most historians state that the halt was made on 12 September 1890. Tawse Jolie wrote: ‘A full-dress parade was called at 10 a.m., 13th September, 1890, the seven-pounder gun fired a Royal Salute, Canon Balfour said a prayer, and the British Flag, the Union Jack, was hoisted by Lieut. Tyndale-Biscoe of the Pioneer Column.”

[21] From The Travel Chronicles of Mrs. J. Theodore Bent. Volume II: The African Journeys. Archaeopress, Oxford, 2012

[22] These are Mabel’s sisters Frances (Faneen) Olivia (Iva) & Ether (E) and Aunt Olivia (Loodleloo)

[23] September being at the end of winter in Southern Africa

[24] Llewellyn Cambria Meredith (1866-1942) provided by the British South Africa Company to organise the transport and local knowledge who went on to have a successful career in Rhodesia (See the article by R.H. Wood. Llewellyn Cambria Meredith, 1866-1942, Heritage of Zimbabwe 16 of 1977, P55-66)

[25] Major ‘Māori’ Browne who served in New Zealand (1866-72) and wrote a book although there are considerable doubts about his record and then in Australia before fighting in Zululand (1878-9) which resulted in another book and then joined the British South Africa Company’s Pioneer Column into Mashonaland in 1890

[26] Inspanning the oxen of an ox-wagon is an involved process assembling them in a line facing the yokes and trek riems which are laid out in a line from the disselboom of the ox-wagon

[27] Tsetse-fly are fatal to domestic stock such as oxen and horses, but wildlife have natural immunity. In his book Theodore writes (P51) “The diseases to which quadrupeds are subject in this country are appalling. One man of our acquaintance brought up eighty-seven horses, of which eighty-six died before he got to Fort Victoria.”

[28] Rinderpest in 1891 had spread from the north and crossed the Zambesi river and wiped out all the oxen within a very short period and brought all transport to a standstill…hence the high prices for oxen

[29] The Rinderpest by killing the oxen had made supplies very short

[30] The Busi river rises near Manica in present-day Mozambique and flows into the Indian Ocean south of the Pungwe river, the two rivers forming a joint wide estuary. The usual route and the one eventually taken by the Bent’s was to meet a small steamer at Mpanda’s, the highest navigable part of the Pungwe river and travel down the river to Beira

[31] African tribesmen

[32] Dr Frederick Rutherfoord Harris (1856-1920) gave up his Kimberley medical practice and became the British South Africa Company’s secretary at Kimberley. Most of Rhodes company correspondence was written by Rutherfoord Harris. Archibald Ross Colquhoun was the Administrator of Mashonaland from October 1890 until September 1892 and was succeeded by L.S. Jameson

[33] Robert McNair Wilson Swan (1858-1904) who the Bents had met in the Cyclades south-east of Greece in the Aegean Sea in 1883/4 and joined the expedition as surveyor. He contributes a chapter in The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland called ‘On the Orientation and Measurements of Zimbabwe Ruins’

[34] This is a surprisingly dishonest course to take – oxen with Rinderpest have a +90% chance of dying after an incubation period of up to 21 days. Clearly the Bent’s intended to be gone by the time the ox showed increasing signs of sickness. On P26 of The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland, Theodore Bent writes of Chief Khama, “On one occasion he did what I doubt if every English gentleman would do. He sold a horse for a high price, which died a few days afterwards, whereupon Khama returned the purchase money considering that the illness had been acquired previous to the purchase taking place.”

[35] This is Randolph Cosby Nesbitt who won a VC on 19 June 1896 when as a Captain in the Rhodesian Mounted Police he led one of the patrols that rescued the civilians at the Alice Mine, Mazoe Valley and escorted them back to Salisbury. He had been a Sergeant in C Troop in the British South Africa Company Police (No 120) escorting the Pioneer Column and was stationed at Fort Victoria. Two of his brothers served in the Pioneer Corps. A week after meeting the Bent party on 15 September 1891 he wa commissioned as a sub-Lieutenant before being demobbed in December as were most of the BSAC Police to reduce costs [A.S. Hickman. Men who made Rhodesia]

[36] The bucksail is the canvas cover on the Scotch cart held up by wooden hoops

[37] Sister Mary Patrick Cosgrave and four Dominican Sisters volunteered to provide nursing services in the newly occupied Mashonaland. Sister Patrick was appointed Mother Superior in charge and always known as ‘Mother Patrick’ and in July 1891 they arrived at Salisbury, ten months after the Pioneer Column and provided nursing care in the first hospital that had been set up. A year later they opened the Salisbury Convent, the first school in Salisbury. Mother Patrick died of tuberculosis in 1900 aged of 37 years; her funeral was the largest ever held until that time, attended by Cecil Rhodes. See the article Mother Patrick’s Mortuary (1895) under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[38] The rinderpest that killed all the oxen prevented supply wagons getting through to Salisbury. The summer rains (November to March 1891) were particularly heavy and the flooded rivers further prevented supplies getting through. Food became short and very expensive and was still expensive in September 1891 as Mabel Bent describes. Further the gold discoveries had been disappointing and many of the Pioneers were disillusioned and felt they had been misled by the BSA Company

[39] The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland, P288

[40] A visit to the ‘fort’ described by Bent in the article Chisvingo and Nhunguza monuments, Masembura Communal Lands under Mashonaland Central Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com will clarify that his description of the site as a fort is incorrect

[41] See the article Dambarare – an Afro-Portuguese Feira site under Mashonaland Central Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[42] The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland, P296

[43] Chief Kunzwi’s kraal is 20km south-east of Goromonzi

[44] The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland, P329

[45] Theodore does attribute the red, yellow and black drawings to the San people and not the Mashona, P333

[46] This important stone monument is described in the article Zvipadze Monument (formerly known as Harleigh Farm Ruin) under Manicaland Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[47] The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland, P351

[48] This is most probably Devil’s Pass described in the article Devil’s Pass and Fort Watts under Manicaland province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[49] The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland, P358

[50] The Bent’s met the three nursing sisters at the first ‘Umtali’ in fact Fort Hill in the Penhalonga Valley and this was followed by the second Umtali at the nearby present-day Methodist Mission. When the railway was planned it was decided that it was cheaper to move the town to its present-day site (now Mutare) rather than bring the railway to the second Umtali. See the articles Fort Hill – the first site of Umtali (now Mutare) and Old Umtali – the second site, both articles under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[51] Rose and Lucy wrote an account of the nurses’ travels including the 225km walk it entailed from Mapanda’s that the Bent’s were about to embark upon. The book is Adventures in Mashonaland by two Hospital Nurses republished by Books of Rhodesia, Gold Series Volume 8, Bulawayo, 1969

[52] Adventures in Mashonaland, P195

[53] Adventures in Mashonaland, P195-6

[54] The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland, P365

[55] The three nurses had come up the Pungwe river to Mapanda’s on the small steamer Shark in which the three of them, Captain Ewing and two sailors “had barely room to sit” (Adventures in Mashonaland, P84

[56] A future article on the website www.zimfieldguide.com will feature some of the items the Bent’s donated to the British Museum

[57] The soapstone birds proved a sensation. They had been sold to Cecil Rhodes after being taken from site in 1890 and kept at Groote Schuur. In 1981 four of them were returned to Zimbabwe and are displayed with others at the small Museum at Great Zimbabwe itself. One soapstone bird remains at Groote Schuur and a German Museum has a portion of another bird’s pedestal.

[58] Quote from The Washington Times, Sunday, November 1, 1903]