Were Lobengula and the amaNdebele tricked by the Rudd concession?

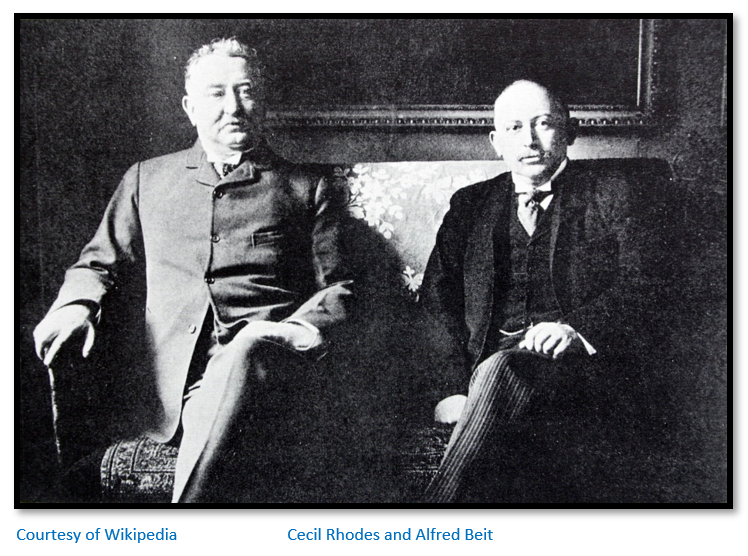

Many concession-seekers had petitioned Mzilikazi and Lobengula over the years for the right to mine gold in Mashonaland. Rhodes went further and saw gaining a concession as the first step to obtaining a royal charter from the British Government for the British South Africa Company which Rhodes would use as a vehicle to acquire Zambesia, the name of the area between the Limpopo and Zambesi rivers in the 1880’s.

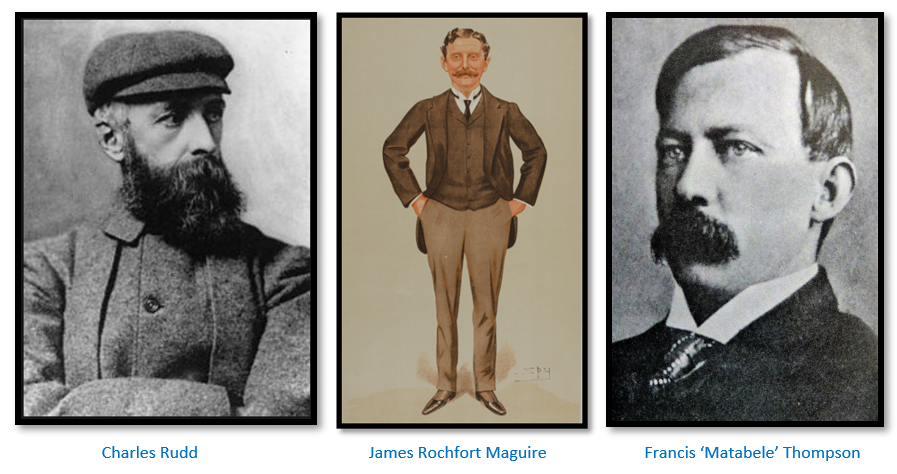

He sent Charles Rudd, a close business associate with Francis Thompson and Rochfort Maguire to Gubulawayo to negotiate with Lobengula and his council of izinDuna. There was fierce competition from other concession seekers at Umvutcha, Lobengula’s kraal, with the main opposition being the London Syndicate, whose local agent was Edward Maund.

Eduard Arthur Maund (picture kindly supplied by Julian Misiewicz)

Very soon after the Rudd concession was signed rumours swirled that the country had been sold and Lobengula realised that the oral promises made by Rudd were not enforceable: “that they would not bring more than ten white men to work in his country, that they would not dig anywhere near towns, etc., and that they and their people would abide by the laws of his country and in fact be his people."

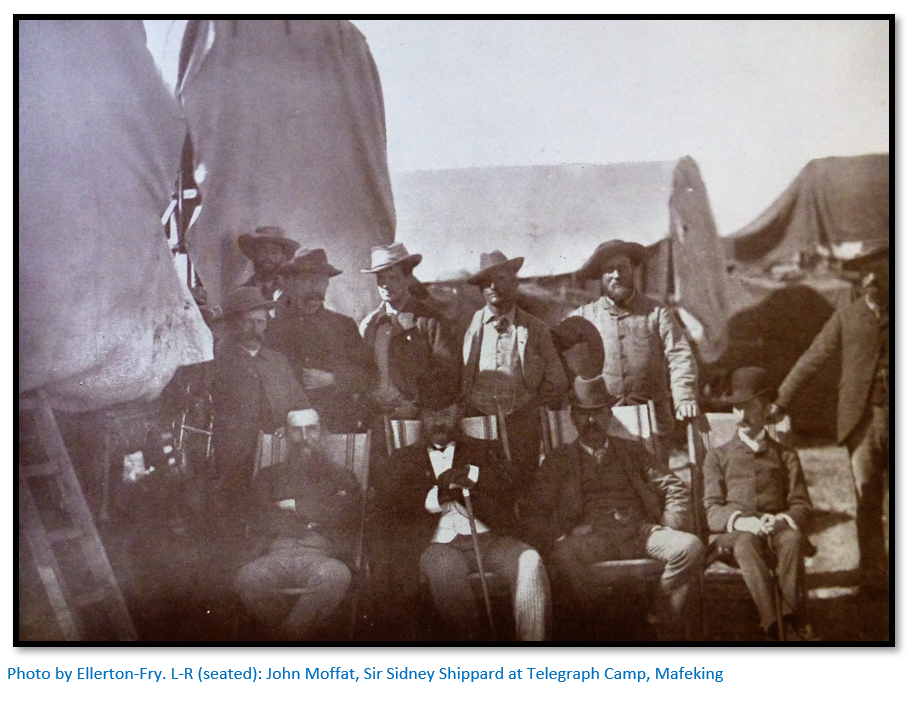

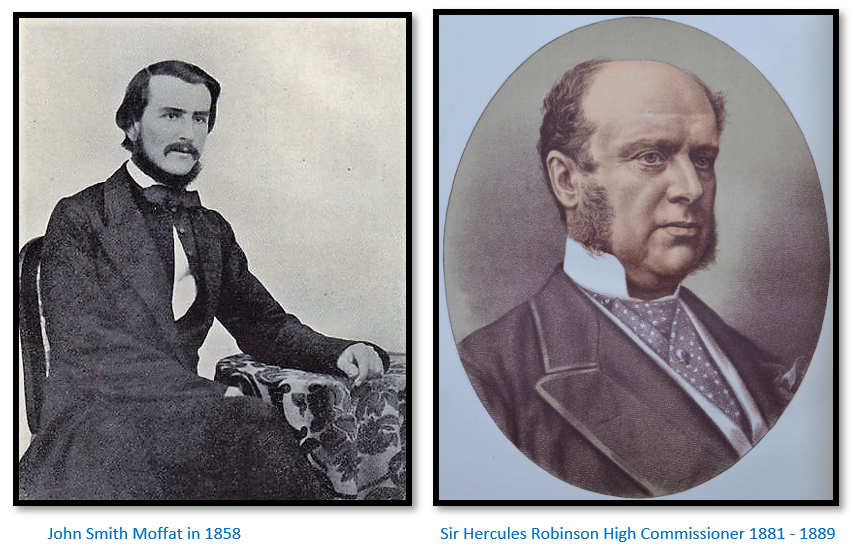

Lobengula’s efforts to persuade the colonial office that the concession was invalid by sending envoys to Queen Victoria and writing letters to the colonial office was destined to fail as all the key officials in southern Africa, namely Sir Hercules Robinson the high commissioner succeeded in June 1889 by Sir Henry Loch, Sidney Shippard, then resident commissioner of the Bechuanaland protectorate and his deputy John Moffat who were all in favour of Rhodes and the British South Africa Company. (BSACo)

The amalgamation of the British South Africa Company’s commercial interests with the London Syndicate led by Gifford and Cawston cleared the way for support from the colonial office as the plan to occupy Mashonaland in 1890 (a not well-kept secret) would:

- Exclude German, Portuguese and Boer territorial threats to British possession in southern Africa

- Form part of Rhodes plan to connect the Cape to Cairo by telegraph and railway

- Would be accomplished without costing the British taxpayer a penny.

| Mzilikazi | |

| 1836 | 3 March - Mzilikazi's envoy, Mncumbathe signs a treaty of friendship with Governor d'Urban in Cape Town |

| 1853 | Mzilikazi agrees, but does not sign, a treaty with Hendrik Potgieter which makes Matabeleland a virtual Transvaal Protectorate, but Potgieter dies before the treaty is concluded. |

| 1853 | Mzilikazi agrees a peace treaty with Andries Pretorius but this time the amaNdebele nation is treated as a distinct nation |

Mzilikazi allowed the London Missionary Society under Robert Moffat who was based at Kuruman to establish a mission station at Inyati, now Inyathi. Moffat arrived in December 1859 and left soon after June 1896 whilst the church and mission buildings were being constructed under William Sykes and Thomas Morgan Thomas.

| 1868 | Mzilikazi gives miners and prospectors the right to mine gold, but not own land in the Tati district. The goldfield becomes the object of the first gold rush; at its peak 220 prospectors and miners were active in the area and it becomes the first european settlement north of the Limpopo river and a base for hunters and traders. |

| Lobengula | |

| 1870 | Lobengula in the year of his accession agrees the Tati Concession to the London and Limpopo Mining Company run by Sir John Swinburne and Capt. Arthur Levert to mine gold in the Tati River area - a strip of land between Matabeleland and the Bechualanland Protectorate bordered by the Shashe and Ramokgwebane rivers. The company brought up a stamp mill powered by a steam engine. |

Lobengula only became King after a brief succession struggle and was not accepted by all the amaNdebele as the rightful heir of Mzilikazi…this latent hostility was a constant factor to be considered during his reign and played a major part in all his dealings with concession-seekers.

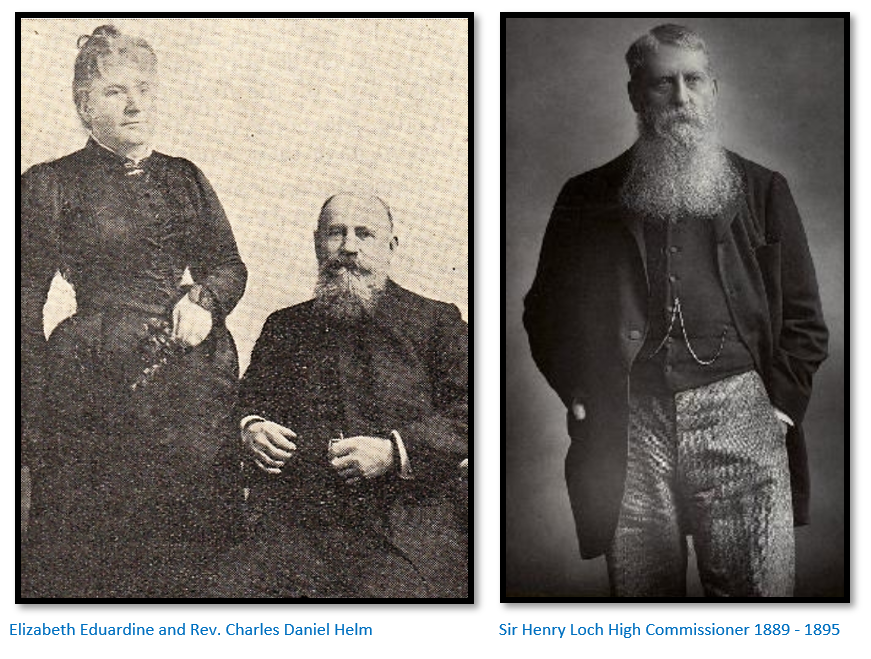

Lobengula followed Mzilikazi in permitting the London Missionary Society to open a new mission at Hope Fountain in 1870 and the first houses and church were begun by the Rev Thomson, but perhaps the better known is Charles Helm for his subsequent and controversial role as interpreter during the drafting and signing of the Rudd concession in 1888. [See the article on Hope Fountain Mission under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

In the same year he granted Sir John Swinburne and his London and Limpopo Trading Company the Tati Concession, an area of 2062 square miles “from the place where the Shashe River rises to its junction with the Tati and Ramokgwebana Rivers, thence along the Ramokgwebana River to where it rises and thence along the watershed of those rivers” this area had never been occupied by the amaNdebele; the original inhabitants of the area were Bakalanga and Basarwa who had resided in the area for centuries and the Bamangwato also claimed the land which was known as the ‘Disputed Territory.’

This shrewd move secured his border between Matabeleland and the Bamangwato people of modern Botswana under Chief Khama III. Over time the concession companies assumed rights far exceeding the mining rights their concession granted, including the rights and administrative powers to issue licences for water, land and machinery and to raise revenue.

However, gold mining at Tati proved to be more difficult than was at first thought as many of the surface deposits had been removed in pre-European times and the quartz veins had been followed down as far as the water table. Most of the miners did not have the working capital or machinery to sink shafts and they soon left to try their luck at the diamond fields at Kimberly.

By 1871 the settlement at Old Tati was virtually abandoned; the only permanent residents remaining were Piet Jacobs, a Boer hunter and his family and Alexander Brown, a Scot who managed the London and Limpopo Mining Company for a while and ran a trading store. Even the big game hunters had also left, as most of the game, which had been so abundant ten years earlier, had been shot or moved to remoter areas within the tsetse-fly belts.

| 1871 | In 1870 Thomas Baines is granted a concession on behalf of the South African Gold Fields Exploration Company to explore for gold between the Gweru and Hunyani, now Manyame rivers |

This concession permitted Baines to mine for gold, but not to own the land. Henry Hartley had noticed the gold workings on the Umfuli, now the Mupfure river in 1866 and the presence of gold was confirmed by Karl Mauch the following year. [A detailed account of Thomas Baines’ efforts on behalf of the South African Gold Fields Exploration Company and some of his painting and watercolours are shown in the article Thomas Baines and the Hartley Hills goldfield under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] His efforts came to nothing as the company ran out of money and Baines died on 8 May 1875 as he was preparing for another expedition to the interior. The Baines concession was never repudiated and but for Baines’ untimely death would probably have prevailed over the Rudd concession.

| 1880 | The Tati Concession with the London and Limpopo Mining Company is revoked for failure to pay the agreed £60 annual fee and awarded instead to the Northern Light Gold and Exploration Company, a syndicate formed by Daniel Francis, Samuel Edwards and others |

In the 1870’s Lobengula was amenable to granting a limited number of mining concessions and hunting licences to Europeans in return for gifts, annual grants and weapons. Because Lobengula was illiterate, but knew written agreements were required, his words were translated and transcribed by one of the hunters, missionaries or traders at his kraal at Umvutcha into English or Dutch, then later read back to him by another. Once Lobengula was satisfied that the written document reflected his words, he would sign his mark, affix the royal seal (which depicted an elephant), and then have the document signed and witnessed by those Europeans present.

Why were so few concessions granted in the 1880’s?

The answer is probably because as Lobengula’s position as King became more secure he no longer felt any need to please the few European concession seekers camped at his kraal at Umvutcha and felt strong enough to continue Mzilikazi’s policy of isolation.

In his younger days Lobengula had joined George Westbeech and George Arthur (Elephant) Phillips at their hunting camps and enjoyed their company. They traded for eight years in Matabeleland before they moved their base to Mpandamatenga in 1871 and Lobengula was well-disposed towards these old residents of Matabeleland. Phillips travelled down country to discuss a mining concession with Lobengula and these talks continued over several months. On 25 January 1884 Lobengula made his mark on an agreement with Thomas Leask, George A. Phillips, George Westbeech and James Fairbairn:

Lobengula’s first concession to Thomas Leask and his partners

Gubulawayo, Amandebele Land

25 January 1884

“I Lo bengula, King of the Amandebele nation have this day granted to Messrs Thomas Leask, George A. Phillips, George Westbeech and James Fairbairn permission to dig and mine for gold and other minerals in my country between the Gwaie [Gwaai] and Hunyani [Manyame] rivers and to remove the product. Also I have given them permission to have a few white men to work and prospect for them. By this grant I cancel all former grants and concessions and this is the only one valid. I give the said company power to add to their number and I also promise to protect them.”

Lo Bengula X his mark

As Witness Elephant seal embossed

T. Halyet

John H. Whitaker

Fairbairn and Phillips both traded in Bulawayo; Fairbairn had custody of Lobengula’s elephant seal in the photo above; Phillips had the King’s ear; perhaps Lobengula thought better ‘the devil you know’ when he granted a concession to these old-timers.

| 1884 | 25 January - Lobengula is persuaded by Philips to sign a concession with a syndicate made up of Leask, Philips, Westbeech and Fairbairn to dig for gold and other minerals between the Gwaai and Manyane rivers - this the same area granted to Thomas Baines in 1871 |

Lobengula’s attitude towards granting concessions changed particularly after the 1886 discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand. Twenty years previously Karl Mauch had been guided by Henry Hartley to the gold fields of Mashonaland and it was Mauch's enthusiastic reports that spread the myth that in Mashonaland lay the Ophir of the Bible and the El Dorado of the ancients. Increasingly as rumours of a “second Rand” circulated more and more Europeans came to Lobengula’s kraal seeking concessions and usually briefed against each other so that Lobengula began to mistrust them all.

| 1887 | Lobengula signs a renewal of friendship treaty with Pieter Grobler on behalf of the Transvaal Republic |

As renewed interest in Matabeleland and Mashonaland grew in the early 1880’s Rhodes began promoting the notion of their annexation by Britain through the colonial office, notably through Sidney Shippard, the resident commissioner of Bechuanaland Protectorate and Sir Hercules Robinson, the high commissioner for Southern Africa.

Shippard viewed the German annexation of Damaraland and Namaqualand and that of Boer adventurers as the main threats, but Portugal had also pressed claims to Mashonaland and Shippard combined efforts with Rhodes to forestall their territorial efforts. John Smith Moffat, well-known to Lobengula as Robert Moffat’s son, was appointed assistant commissioner in Bechuanaland in an effort to persuade Lobengula to become pro-British.

Portuguese threats

These were mostly historic and based on their trading stations in Manicaland and Mashonaland which were sacked in 1693 [See the article on Luanze Earthworks and Church under Mashonaland East and How Mutare and Manicaland were annexed from the Portuguese under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] Portugal had concluded treaties with Germany and France which recognised historic Portuguese claims to the territory between Mozambique and Angola, however in reality in the late nineteenth century Portugal’s occupation was largely confined to the coast and British traders and explorers were pressing for an alliance with Lobengula to counter Portuguese claims.

The threat from the Transvaal Republic

In September 1887, Robinson wrote to Lobengula, through Moffat, advising Lobengula not to enter into discussions with agents of the Transvaal Republic, Germany or Portugal. When Moffat reached Gubulawayo in November he found Grobler still at Lobengula’s kraal. There had been much speculation around the nature of the friendship treaty, but Grobler denied to Moffat that a Transvaal Republic protectorate over Matabeleland had been agreed; whilst Lobengula said it was merely a renewal of the 1853 Pretorius friendship treaty.

Paul Kruger, the President of the South African Republic was deliberately ambiguous about the terms of the Grobler treaty and in response to this perceived threat, Rhodes, Robinson and Shippard met at Grahamstown on 25 December 1887 and agreed to instruct Moffat to obtain from Lobengula a copy of the Grobler treaty and to arrange a formal treaty with Lobengula that recognised a “special-relationship” existed between Britain and the Matabeleland in preference to other foreign powers.

The 1884 London Convention had recognised the independence of the Transvaal Republic but in return the Boers were not permitted to expand either to the east or the west. Through this any threats to the “missionary road” centred on the London Missionary Society mission station at Kuruman were neutralised. This was regarded by Rhodes as the key route of British influence northwards, a “Suez Canal” from the Cape to Central Africa. However there was nothing to prevent the Transvaal Republic from expanding northwards into Matabeleland or even Germany. On 3 January Rhodes had written to Shippard: “The only thing we have now to work for is that the Germans shall not take Matabeleland. I think you will have to lay your plans for several years residence in Bechuanaland.” In fact, Germany had no designs on central southern Africa, but it suited Rhodes long-term plans for both Lobengula and the colonial office to be made constantly aware of these potential threats.

| 1887 | 17 November - Lobengula awards a gold-mining concession to the Woods-Chapman-Francis syndicate in the "disputed territory" between the Shashe and Macloutsie rivers |

Woods party made a successful trip through Mashonaland going as far east as Wedza mountain before returning to Gubulawayo on 21 October 1887 where Lobengula denied having given them permission to prospect and only to hunt and shoot. The King was negative about granting them a gold concession in Mashonaland but finally after much discussion was granted a concession between the Shashe and Macloutsie rivers.

Know all men by these presents that we Lobengula King of the Matabele Nation with the advice and consent of my Indunas this day granted to Joseph Garbett Wood and Edward Chapman of Grahamstown and William Curl Francis of Mangwato to their heirs and assigns: viz., the sole right to search for, extract and utilise gold and any other metal that may be found upon any of the ground or rivers between the Rivers Shashi and Macloutsie from their source to where the rivers empty themselves into any other rivers; To erect mills for stamping purposes or any other form of mills and smelting works, and to reduce ores or minerals as may be required; he exclusive right to all water within the described area between the Rivers Shashi and Macloutsie; the right to ant timber or wood required; the right of making and using roads; the right of grazing stock; the right of erecting such buildings as may be required for machinery and labourers. The said Wood, Chapman, Francis their heirs and assigns on their part promising truly to pay or cause to be paid an annual rental of one hundred pounds sterling to me or my lawful representative, this rental to be due and payable at te expiration of one year from the signing of this deed of cession or grant…shall remain in lawful possession for a term not to exceed ninety-nine years terminating in the year of Our Lord 1986, with the right of renewal.

Given under my hand at the Royal Kraal Umbucha, this seventeenth day of November 1887

Lobengula, King of the Matabele

In the presence of His X mark

G.A. Phillips

M. Cohen Great Seal of Kingdom attached

It is further understood that should the parties commence working the reefs before the expiration of one year then the annual payment shall be made on the day the work commences.

Witness, Present, Noonje Razengwani

M. Cohen

G.A. Phillips

J.W. File, Interpreter

Wood’s party saw Chief Khama at Shoshong who informed them that the country between the Shashe and Macloutsie rivers belonged to him and that he would not allow them to mine for gold.

At Kimberley Wood received a telegram from his brother which said: “Governor told me last night that he had instructed Administrator Shippard to arrest and imprison Wood, Chapman, Francis or any other white man attempting to enter territory in dispute between Khama and Lobengula until dispute is settled. Administrator has full power to arbitrate between the two chiefs, when settled Governor says justice will be done to all who secured concessions.”

In September 1888 Wood attempted to revisit Gubulawayo via Pretoria for a further interview with Lobengula. They were stopped soon after crossing the Limpopo river, as the local chief since the death of Grobler permission was required from the King to enter Matabeleland. After some delay on 26 October Sir Sidney Shippard’s wagons arrived escorted by Major Gould Adams and an escort of Bechuanaland police. The Major said Lobengula had written to Shippard; Matabeleland was in a very excited state and he would not advise them to go any further as the lives of every white person in Matabeleland would be threatened and no further concessions would be issued.

John Moffat, Shippard’s deputy, negotiates a treaty paving the way for the Rudd concession

Moffat’s efforts to persuade Lobengula to sign a treaty of friendship as Mzilikazi’s envoy, Mncunbathe had done with Governor d ’Urban in 1836, were long and drawn-out as now Lobengula and his council of Indunas were reluctant to sign any more treaties. However Moffat told Shippard: “they may like us better, but they fear the Boers more” and eventually Moffat’s efforts paid off and Lobengula placed his mark to a treaty of friendship which declared that Lobengula would not enter any kind of diplomatic correspondence with any country apart from Britain, and that the King would not "sell, alienate or cede" any part of Matabeleland or Mashonaland to anybody

| 1888 | 11 February - Lobengula signs with John Moffat a treaty of friendship with Britain stating he would have diplomatic negotiations only with Britain and would not "sell, alienate or cede" any part of Matabeleland or Mashonaland to anybody. |

Rhodes out-manoeuvres the colonial office

The colonial office was initially hesitant about the treaty which they had neither authorised or committed to…they referred it back to Robinson but he believed it was in both Britain’s and the Cape’s commercial interests and eventually they believed the treaty was advantageous to Britain’s interests, as it did not commit Britain to any specific policy or actions. It was not the first time that Rhodes with the active connivance of Shippard and Robinson stole a march on the colonial office.

AGREEMENT

The Chief Lobengula, Ruler of the tribe known as the Amandebele together with the Mashuna and Makakalaka tributaries of the same, hereby agrees to the following articles and conditions:

That peace and amity shall continue for ever between Her Britannic Majesty, Her subjects and the Amandebele people; and the contracting Chief Lobengula engages to use his utmost endeavours to prevent any rupture of the same, to cause the strict observance of this Treaty, and so to carry out the spirit of the Treaty of friendship which was entered into by his late father the Chief Umsilagaas with the then Governor of the Cape of Good Hope in the year of our Lord 1836.

It is hereby further agreed by Lobengula, Chief in and over the Amandebele country with its dependencies as aforesaid, on behalf of himself and people, that he will refrain from entering into any Correspondence or Treaty with any Foreign State or Power to sell, alienate, or cede, or permit or countenance any sale, alienation, or cession of the whole or any part of the said Amandebele country under his chieftainship, or upon any other subject, without the previous knowledge and sanction of Her Majesty's High Commissioner for South Africa.

In faith of which, I, Lobengula have on my part hereunto set my home at Gubuluwayo, Amandebeleland, this eleventh day of February, and of Her Majesty’s reign the Fifty-first.

LOBENGULA X his mark

Witnesses:

W. GRAHAM

G.B. VAN WYK

Before me: J.S. MOFFAT

Assistant Commissioner

February 11th, 1888

Approved and ratified by me as Her Majesty’s High Commissioner for South Africa, this 25th day of April 1888

HERCULES ROBINSON

High Commissioner

Government House, Cape Town

Portuguese objections to Lobengula’s claim over Mashonaland

Note the treaty covers; “the Amandebele together with the Mashuna and Makakalaka tributaries of the same” i.e. Mashonaland which Portugal already claimed they had historic rights over. Certainly many Mashona chiefs claimed they owed no allegiance to the amaNdebele although they were subject to their periodic raiding parties. Selous wrote: “Various communities of Mashona are subject to Lobengula, pay him tribute and keep the great herds of cattle owned by the Matabeles. They are well-treated and have little to complain of in so far as they are looked up to. But alongside of them live numerous tribes of Mashonas who are in no wise subject to Lobengula. They pay him no tribute and when they are attacked by his Nobles, they take refuge in the caves and on the summits of their mountains and defend themselves and their property as well as they can against the invaders.”

Once Selous joined forces with Rhodes however there was no further talk of Shona independence as it was in Rhodes’ interest to maintain that Mashonaland was under amaNdebele dominion.

Sidney Webb at the colonial office noted that; “Lord Salisbury has been for some time cross with our ancient ally” as Portugal’s was attempting to restrict aid to those Scottish missionaries and others resisting the slave trade in present-day Malawi. Salisbury Events were slowly moving to Rhodes’ advantage.

For Rhodes, the chief advantage of the treaty was to give him time. In March his proposal to merge the De Beers Diamond Mining Company with the Barnato brothers Kimberley Central Diamond Mining Company to form one new consolidated company; De Beers Consolidated Mines went ahead. In 1887 Rhodes and Charles Rudd had formed Gold Fields of South Africa to hold properties they had acquired on the Witwatersrand gold fields. Now Rhodes had the financial muscle to make his dream of creating a British empire in Africa a reality.

Rhodes next priorities were:

- Acquiring a mining concession with Lobengula over Mashonaland

- Obtaining a royal charter based on the mining concession

- Floating a chartered company (BSACo) on the London Stock Exchange to use as a vehicle to annex Mashonaland on Britain’s behalf

Rhodes wrote to Shippard on 14 August 1888: “My plan is to give the Chief [Lobengula] whatever he desires and also to offer Her Majesty’s Government the whole expense of good government. If we get Matabeleland we shall get te balance of Africa. I do not stop my ideas at Zambezi.”

Obtaining a mining concession from Lobengula

Rhodes faced a number of obstacles. As noted above, Lobengula and his council were wary of signing mining concessions. In addition there was competition from other concession-seekers.

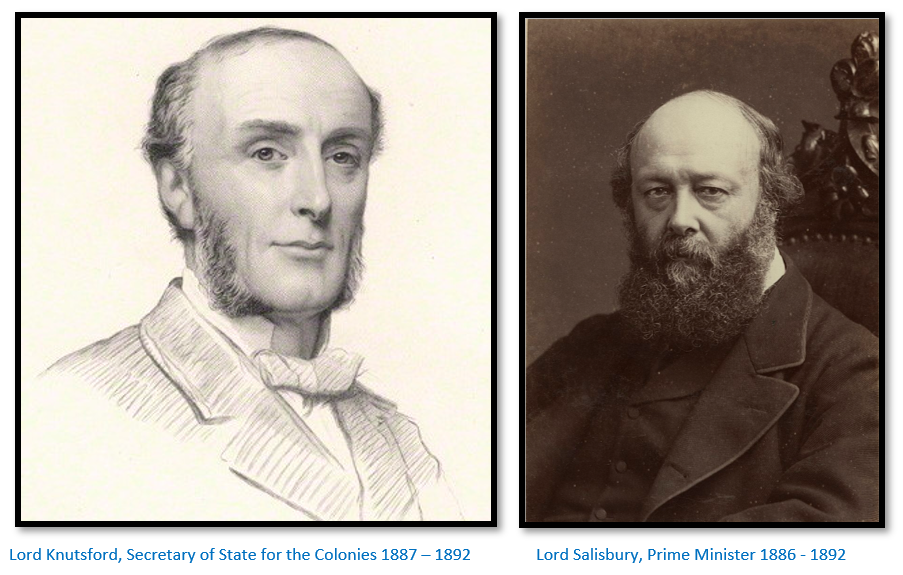

Lieutenant Edward Maund was one of three officers sent to inform Lobengula in 1885 that Britain had declared Bechuanaland a protectorate. He heard the tales of gold found in Mashonaland and interested George Cawston, a London financier and Lord Gifford who already had obtained substantial mineral rights in Northern Bechuanaland, in obtaining a mining concession in Mashonaland. Whilst Maund left for Gubulawayo to negotiate terms, Cawston and Gifford wrote to Lord Knutsford, the colonial secretary seeking his support.

In June 1888 whilst Rhodes was in London he heard of the London Syndicate approach to the colonial secretary and realised that urgency was required in negotiating a concession with Lobengula. Rhodes and Alfred Beit hurriedly put together their own party consisting of Charles Rudd, Francis Thompson and Rochfort Maguire.

Rhodes and Beit put Rudd at the head of their new negotiating team because of his extensive experience negotiating the purchase of Boers' farms for their company Gold Fields of South Africa.

Because Rudd knew little about African customs and languages, Francis ‘Matabele’ Thompson, a De Beers employee, who spoke Setswana was included and would be able to talk directly with Lobengula and his council. The inclusion of the third member of the party is somewhat of a puzzle; James Rochfort Maguire was an Irish barrister whom Rhodes knew at Oxford. Both men supported Parnell’s home rule for Ireland in which all the self-governing territories would send members to the British Parliament, but possibly he was included to add a “touch of class” in a bid to rival Lord Gifford’s prestige.

Maund arrived in Cape Town in late June 1888 and attempted to gain Sir Hercules Robinson's approval for the London Syndicate bid. Robinson answers were deliberately ambiguous; he supported British ambitions in Mashonaland but would not commit to the London Syndicate. Maund reached Kimberley in July as Rudd’s party was preparing for their journey to Gubulawayo.

| 1888 | 14 July - Thomas Leask is awarded a second mining concession |

I, Lo Bengula King of the Amandabele hereby grant to Thomas Leask, George Arthur Phillips, George Westbeech and James Fairbairn the sole right to dig for gold and other minerals in my country to the exclusion of all others except to those to whom I have already granted similar rights and that on the condition that I receive one half share of the proceeds of the work carried on by them – on the same principle as my own people work for me.

Lo Bengula his x mark

Witnesses

Bowen Rees Elephant Seal

J.A. Dawson

Interpreted by Chas D. Helm, Missionary of the London Missionary Society at the King’s kraal, Emkanwini, 14 July 1888

This mining concession covered all of Lobengula’s country in return for a fee of half the profits but Leask feared the concession was “commercially useless” and Moffat persuaded Leask that as he lacked the financial resources he should wait and sell his concession to either Rhodes or the London Syndicate, neither of whom yet knew of this concession. Parts of Moffat’s letter are quoted below:

Sanane River, 28 Nov 1888

My Dear Mr Leask,

….I believe that the Chief Lobengula is fairly honest in intentions when he puts his name to an agreement, but I have come to see, especially lately that he is far from being a free agent. He has in fact forces behind him which he can ill control – and the jealous and suspicious nature of his fighting men aroused, any agreement of this sort made with white men would be of little account. The Chief is being beset with applications. I have reason to believe that during the two months I have spent there, just now, at least five hundred pounds in gold has been given to him by different parties, in order merely to pave the way for concessions. My advice to such as gave me an opportunity of offering advice was – let all combine and act on a settled plan – this advice was not taken and the result has been a most unsatisfactory clashing of interest and by such a mode of procedure certainly not forwarding their own; for the Chief is learning how to play one against another to pocket the proceeds with tolerable freedom from any responsibility – beyond a few fair words.

I have heard a great syndicate [this of course, led by Rhodes] of which you may have heard is at work and is prepared to deal with the matter on an unprecedented scale…and I should like to see such a scheme carried out. Could not the interest represented by you be merged in this? I fancy it will be this or nothing…

J.S. Moffat

Leask and Phillips sold out to Rhodes for £30,000 each. Fairbairn refused to sell until a year later when Rhodes would only pay £3,000. Leask and Phillips each paid one quarter of their proceeds into Westbeech’s estate, but Fairbairn did not.

In the same month Rhodes returned from London and spoke to Sidney Shippard, the administrator of the Bechuanaland protectorate and Hercules Robinson, the high commissioner, about forming a chartered company along the lines of the British North Borneo, Imperial British East Africa and Royal Niger charter companies. This proposed charter company would take possession of “Zambesia,” reserve areas for the exclusive use of the indigenous peoples and develop the remaining land. The beauty of this for the colonial office was that it would all be privately financed without state aid.

Shippard, a close ally of Rhodes, was already an enthusiast for the idea and wrote to Robinson strongly endorsing annexation of the territories, particularly Mashonaland, which he described as "beyond comparison the most valuable country south of the Zambezi."

The idea appealed to Robinson who:

- wrote to Knutsford saying the Transvaal Republic would be more likely to back a scheme that involved a chartered company occupying the territories of “Zambesia” between the Limpopo and Zambesi rivers than if it was a British Crown colony,

- wrote a second letter of recommendation for Rudd’s party to carry to Lobengula.

In July 1888 Piet Grobler was also on his way to see Lobengula and passing through the disputed territory when he was intercepted by a party of Khama’s men searching for two English traders who were in violation of a liquor ban within the Bechuanaland protectorate. A fight ensued and Grobler was accidently shot, probably by one of his own men and died of his wounds. Shippard held an enquiry attended by German military advisers and representatives of the Transvaal republic, although the incident had occurred outside the protectorate and his jurisdiction – his acquittal of the BaNgwato was disputed by the colonial office and the Transvaal Republic.

Francis Robert Thompson, one of Rudd’s party

In the autobiography of Francis Robert ‘Matabele’ Thompson edited by his daughter Nancy Rouillard, Thompson states that on meeting the Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, at the Houses of Parliament Rhodes first words to him were: “Now for our daydreams of securing the territory up to the Zambesi for the British nation.” At the time Rhodes was in negotiations with the De Beers Company controlled by Barney Barnato and Alfred Beit and Barnato replied in response to Rhodes appeal for support: “Your sphere of British influence does not appeal to me. You Rhodes, want empires; I want money – money counted in millions.” Thompson states: “It was only then that Rhodes decided the acquisition of mineral rights must be the basis of the opening of the north.” He goes on to say that Rhodes cared about as much for money as a monkey cares for a diamond necklace. He was interested first and last and all the time in his political plans and money was merely a means to an end.

Rhodes, Rudd and Thompson formed the Matebililand Syndicate with the sole purpose of obtaining a concession from Lobengula. Thompson had to borrow his share of the venture capital from the Cape of Good Hope Bank and Rudd was his guarantor.

Some historical writers have queried Maguire’s role. Thompson states he was not in an official sense a member of the expedition and had no share in the syndicate. The concession was drafted by Rudd, altered by Thompson to suit the izinDuna’s understanding and reviewed by Maguire. Thompson said Maguire was a man of charm and ability, but his distaste for life in Gubulawayo caused Thompson much future trouble.

The race to Gubulawayo

After telling everyone in Kimberley they were going shooting big game, Rudd’s party left on 15 August 1888, well behind Maund. Rudd’s party encountered thirst, mules dying, wagons breaking down and at Shoshong they were held up following Grobler’s death by Khama who said no white men could travel north.

Shoshong’s resident missionary, Reverend Hepburn was away and Thompson showed the high commissioner’s letter, bearing the Queen’s stamp, to Mrs Hepburn:

O.H.M.S.

To King Lobengula,

King of the Amandabili

I beg to introduce to you Messrs. Rudd and Thompson, two highly respectable gentlemen who are visiting your country.

Hercules Robinson

High Commissioner

Mrs Hepburn thus secured their onward passage and when Thompson told Rudd that he felt certain they would succeed in their mission, he replied: “You are a sanguine man and always up in the stirrups.”

They were both beaten to Gubulawayo by John Moffat who left from Shoshong in the Bechuanaland protectorate and found the kraal at Umvutcha surrounded by white concession-hunters. Following his Grobler enquiry Shippard also arrived in Gubulawayo and persuaded Lobengula to renounce the Grobler treaty and with Moffatt laid the groundwork for Lobengula later signing in favour of the Rudd concession.

In addition the Grobler treaty was declared invalid by the British Prime Minister Lord Salisbury who declared that the Moffat treaty superseded the Grobler treaty because the London Convention of 1884 only permitted the Transvaal Republic to sign treaties with the Orange Free State and individual native tribes, but not with the amaNdebele, who were a nation rather than a tribe.

Maund wrote a letter to the London Syndicate volunteering to help defend Khama saying this might enable him to win a concession over the disputed territory, but Cawston wrote back telling Maund not to waste time and to concentrate on Lobengula; however a month had since gone by and Maund had squandered his head start on Rudd.

The Rudd party ignored a notice that Lobengula displayed at Tati barring entry to white big-game hunters and concession-seekers and arrived at Umvutcha, the King’s kraal, on 21 September 1888, three weeks ahead of Maund.

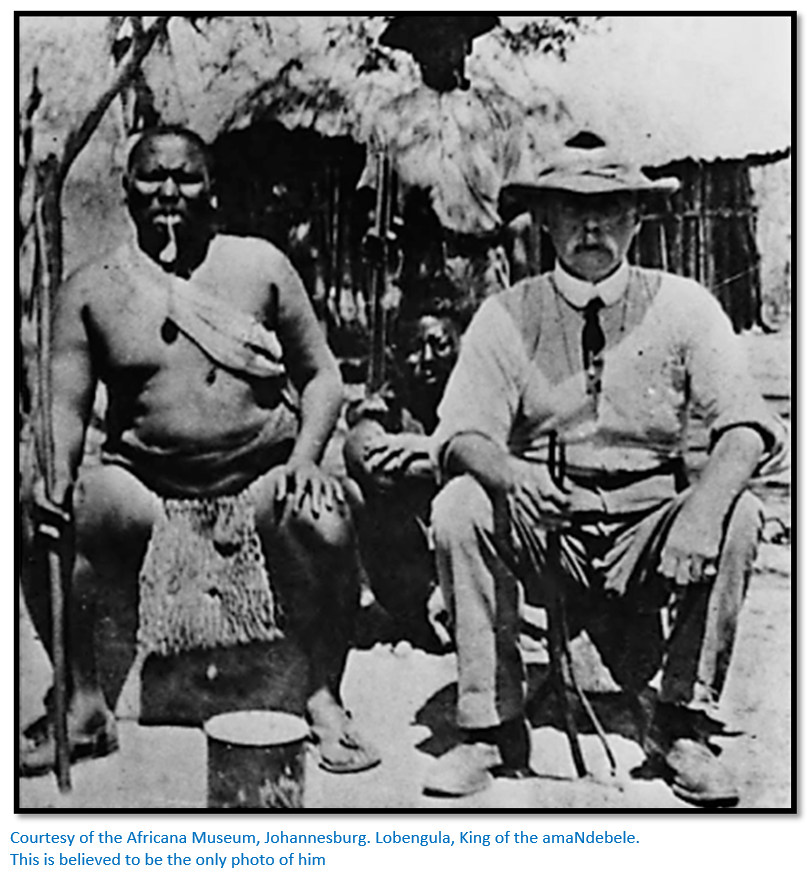

Thompson’s description of Lobengula

Thompson says that Lobengula weighed about 127 kilograms (or 280lbs) and was: “tall, stout, well built, looking every inch a King.” The royal kraal built of wood poles was known as the ‘buck kraal’ where about five hundred goats were kept at night. Lobengula was seated on a block of wood, surrounded on all sides by goats and dogs. They had been told it was the custom to crawl towards him on hands and knees and remain like this in his presence, but they walked up to him in the ordinary fashion, much to the surprise of his entourage. They were kept waiting for their audience, but introduced themselves and presented the King with a gift of £100 in gold sovereigns and were told to come back in a few days.

Negotiations

After three days they had their next audience and Thompson explained in Sechuana that they were not Boers and had not come to seek land, but only wanted to mine for gold in Mashonaland. Lobengula was interested in Thompson’s gun-shot wounds from his younger days. Little headway was made as the King preferred talking of anything rather than discussing a gold concession.

Talks took place intermittently over the next few weeks with the King consulting his council and Moffat for advice. Moffat argued that it would be easier for Lobengula to manage Rhodes and his organisation rather than many smaller concession-holders and urged Lobengula to await Shippard’s arrival. Money had little value to the amaNdebele who thought gold sovereigns were best suited for making bullets…guns and ammunition were what they really valued. But Lobengula was in no hurry and most days were spent in camp by the concession-seekers playing backgammon or reading.

Shippard arrived accompanied by Sir Hamilton Goold-Adams and sixteen Bechuanaland Border Police in mid-October. Shippard openly advocated Rhodes saying he was backed by the colonial office and was the only organisation with sufficient financial resources to keep the Boer forces from overrunning Lobengula’s territory.

Rhodes advised Rudd that Maund, Cawston and Gifford of the London Syndicate were their main rivals and that he should not leave Gubulawayo without the concession. "You must not leave a vacuum. Leave Thompson and Maguire if necessary or wait until I can join ... if we get anything we must always have someone resident." Prevented by Rhodes from leaving, Rudd tried in vain to complete negotiations with a draft document before Shippard left in late October.

Finally one hundred izinDuna met at the King’s kraal over two days; Charles Helm was asked by the King to interpret. Helm had established the London Missionary Society at Hope Fountain, understood the language and was trusted by Lobengula. However, he too firmly favoured the Rhodes proposal as he thought it might lead to the amaNdebele becoming more sympathetic towards Christianity.

Thompson emphasized that the Boers were pressing at the borders which he likened to a dish of milk attracting flies, the Portuguese were negotiating treaties with the chiefs in the east; in the event of a concession the amaNdebele would be able to face them with the Martini-Henry rifles and ammunition they would supply. He used a metaphor when describing why they should be given the sole right to mine gold…if there were two bulls in a herd of cows the bulls would certainly fight rather than be looking after the cows.

Lobengula called his council of izinDuna but opinions were sharply divided. The King and many older izinDuna were receptive to a granting a mining concession, younger izinDuna were set against letting Europeans into Mashonaland. Some thought granting a mining monopoly would mean the end of a succession of concession-seekers; others thought it was a useful system for earning gifts.

Rudd, Shippard and Moffat emphasised the Boer threat; the amaNdebele understood the Boers wanted land; Rudd claimed to be only interested in mining and trading, therefore if they granted Rhodes the concession the British would be obligated to protect them from the Boers in order to look after their own interests.

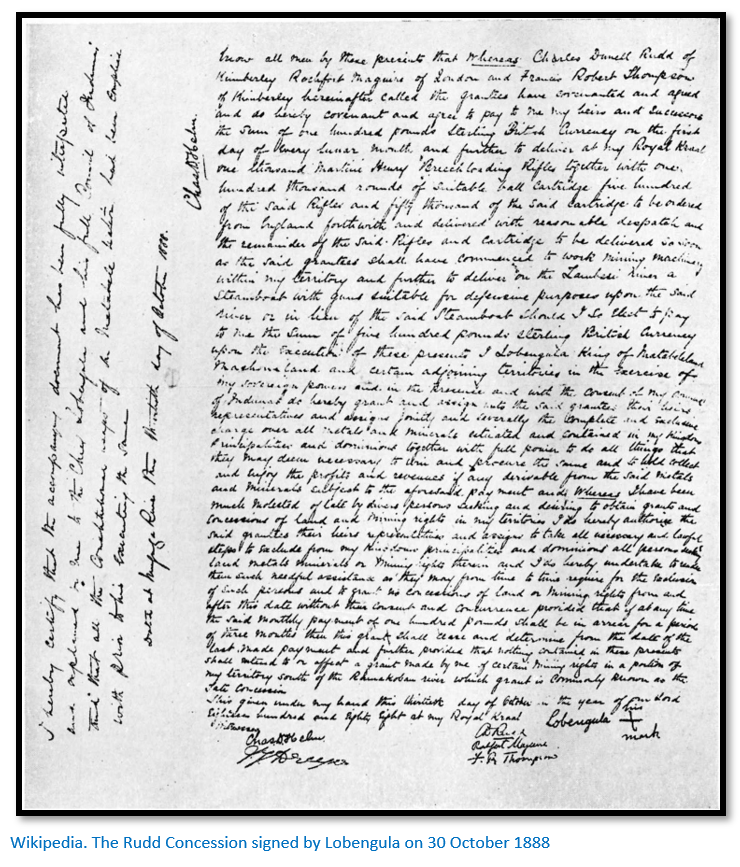

The terms being offered by Rudd’s party were better than any other; one thousand Martini-Henry breech-loading rifles, one hundred thousand rounds of ammunition, a steamboat on the Zambesi river or £500, and an annual payment of £100. Charles Helm read the document to Lobengula several times before negotiations started on 30 October 1888.

Final negotiations with the izinDuna

The King did not engage in the final round of negotiations but was in his royal kraal nearby. The izinDuna wished to know where mining would take place. Rudd said they wanted rights covering the entire country, but the izinDuna would not agree to this. They said: “No, take the part this side of the Tati, you have seen that.” Rudd insisted: "No, we must have Mashonaland, and right up to the Zambezi as well—in fact, the whole country." The izinDuna were confused as to where these places were and the arguments became circular. Frustrated, Rudd and Thompson rose to leave saying: “Yes Indunas, your hearts will break when we have gone and you will remember the three men who offered you moshoshla (rifles) for the gold you despise in this land.”

Lotshe persuaded Thompson to stay and the izinDuna agreed that inDuna Lotshe and Thompson would speak to the King alone.

The concession

After speaking with Lotshe and Thompson, the King was still hesitant to make a decision. Thompson appealed to Lobengula with the following question: "Who gives a man an assegai [spear] if he expects to be attacked by him afterwards?" Lobengula understood this related to the Martini–Henry rifles and made the decision: "Bring me the fly-blown paper and I will sign it," he said. Thompson briefly left the room to call Rudd, Maguire, Helm and Dreyer and they sat in a semi-circle around the King. Rudd says in his diary that the King was sitting on an old brandy case in a corner of the buck kraal. He said “Good morning” in a good temper but appeared hustled and anxious. For half an hour he would not sign saying that a promise was all that he would give but that he never signed his name. Rudd had almost made up his mind to clear out when the King suddenly said to Rev Helm: “Hellum, tele lappi” [Helm, give it to me] and there and then put his mark to the concession.

| 1888 | 30 October - the Rudd Concession is signed between King Lobengula of Matabeleland and Charles Rudd, James Rochfort Maguire and Francis Thompson acting as agents on behalf of Cecil Rhodes |

As Lobengula made his mark at the foot of the paper, Maguire turned to Thompson and said "Thompson, this is the epoch of our lives" and once Rudd, Maguire and Thompson had signed the concession, Helm and Dreyer added their signatures as witnesses with Helm adding an endorsement alongside the concession terms: “that all things had been done in conformity with the customs, laws an usages of the Matebili nation in full council and after full consideration and that the concession had been fairly and honestly obtained.”

It is not clear why Lobengula would not allow the izinDuna to sign the concession, but Rudd thought as they had already been consulted Lobengula did not consider it was necessary for them to also sign. Others believed that with only Lobengula’s mark on the concession he may have felt it would be easier to reject if necessary in the future.

Rudd’s oral statements

Although Lobengula clearly thought Rudd's alleged oral conditions ["that they would not bring more than ten white men to work in his country, that they would not dig anywhere near towns, etc., and that they and their people would abide by the laws of his country and in fact be his people."]

were part of the conditions of the concession document, none of them were written into the document, making them legally unenforceable. Reverend Charles Helm in later years also stated these oral promises were made.

Rudd takes the news to Rhodes

None of the other Europeans at Gubulawayo were told they had obtained a concession; Rudd quickly left Gubulawayo by mule cart to take news of the concession signing to Rhodes. However after ten days he lost the road and ran out of water. He thought he would die of thirst and wrote a letter which he fastened to a tree and hid the concession. Delirious in the night he stumbled on a San hunter-gatherer camp who saved him before he retrieved the concession. Reaching Kimberley after just twenty days on 19 November 1888. Rhodes was thrilled at the news saying: “so gigantic it is like giving a man the whole of Australia.” Both left immediately by train, meeting with Hercules Robinson on 21 November.

Whilst Robinson wished to publish the news in a Gazette, Rhodes knew that the news that he was arming the amaNdebele with one thousand modern Martini-Henry’s would be received with alarm by the Boers and advised caution until the rifles were in the Bechuanaland Protectorate.

An account omitting any mention of the Martini-Henry rifles was published in the Cape Times and Cape Argus newspapers on 24 November. Two days later the Cape Argus printed a notice from Lobengula: “All the mining rights in Matabeleland, Mashonaland and adjoining territories of the Matabele Chief have been already disposed of and all concession-seekers and speculators are hereby warned that their presence in Matabeleland is obnoxious to the chief and people. Lobengula.”

Rumours reach Lobengula

Thompson and Maguire had stayed in Bulawayo to represent Rhodes and ensure that the King was not persuaded by other concession-seekers to change his mind. But Moffat after telling the King previously that it would be easier for Lobengula to manage one concession-holder, now questioned whether Lobengula would be able to control the expected influx of miners and prospectors. The other concession-seekers encouraged rumours that Rudd’s party had taken the country and the amaNdebele would have no land on which to live.

When a group of prospectors led by Alfred Haggard and representing the Austral Africa Company attempted to enter the country Maguire accompanied an amaNdebele impi to see them off.

On Maguire’s return to Gubulawayo Thompson warned him that everything they did was put down to an evil motive. Their walks were represented as prospecting for gold and on many days they did not leave camp for fear of being harmed. Thompson could handle the hardships of poor food and little exercise, but Maguire: “The dilettante member of Parliament, ex-attaché, Fellow of All Souls was completely out of his element and he suffered accordingly.”

Lobengula’s envoys to Queen Victoria

Lobengula asked Maund to accompany two of his izinDuna, Babayane and Mshete to England, so they could meet Queen Victoria herself; officially to present a letter highlighting Portuguese territorial ambitions in eastern Mashonaland, but also unofficially to ask for advice on dealing with the concession-seekers. [Their journey is covered in the article Why Lobengula sent envoys to Queen Victoria in the late nineteenth century under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Maund was happy to assist as he saw this as a chance to turn the tables on Rhodes in favour of the London Syndicate. Rhodes hoped to stop the envoys leaving Africa and at Kimberley had Jameson try to win Maund over by offering him financial inducements to leave the London Syndicate, but these offers were turned down by Maund.

The envoys reached Cape Town in mid-January 1889 and now Robinson, Rhodes’ ally, attempted to delay them and discredit them at the colonial office by saying that Shippard had described Maund as "mendacious" and "dangerous" Colenbrander as "hopelessly unreliable" and Babayane and Mshete as not actually izinDuna or even headmen.

The colonial office requests answers

In the meantime Rhodes and Rudd returned to Kimberley, and Robinson wrote to the colonial office on 5 December 1888 to inform them of Rudd's concession, but Lord Knutsford had already learned of its existence from Cawston and Gifford of the London Syndicate; Robinson received a telegram asking if there was any truth that Martini-Henry rifles formed part of the payment. He replied by letter enclosing a memo from Shippard stating that as the amaNdebele were less experienced with rifles than with assegais and receiving rifles would not make them more dangerous; also it was not diplomatic to supply Khama and the Bechuanaland chiefs with guns whilst refusing Lobengula and finally that the prospect of armed amaNdebele might make the Boers think twice before interfering.

Rhodes and the London syndicate become allies

Instead of trying to thwart the London Syndicate Rhodes decided to change tactics and try to win over Cawston and Gifford; he began by talking with Maund. His attitude became markedly different after looking over Lobengula's message to Queen Victoria and said that he believed the Matabele expedition to England would actually support the Rudd concession if the London syndicate could be persuaded to merge their interests with his own and together form an amalgamated company. He told Maund to wire this pitch to his employers.

Maund presumed that Rhodes's shift in attitude had come about because of his own influence, coupled with the threat to Rhodes's concession posed by the Matabele mission, but in fact the idea for uniting the two rival bids had come from Knutsford, who the previous month had suggested to Cawston and Gifford that they were likelier to gain a royal charter covering south-central Africa if they joined forces with Rhodes. They had wired Rhodes, who spoke with Maund. The amalgamation freed Rhodes and the London Syndicate from their long-standing stand-off; Cawston and Gifford could now utilise Rhodes's considerable financial and political resources and Rhodes's Rudd concession had greater value now the London Syndicate no longer challenged it.

Rhodes settles the Leask concession

Rhodes resolved that the Leask concession must be acquired, he told Rudd: "I quite see that worthless as [Leask's] concession is, it logically destroys yours." In late January 1889 Rhodes met and settled with Leask and his associates, James Fairbairn and George Phillips, in Johannesburg. Leask was given £2,000 in cash and a 10% interest in the Rudd Concession and kept a 10% share in his own agreement with Lobengula. Fairbairn and Phillips were granted an annual allowance of £300 each.

Opposition to Lobengula’s envoys is dropped

In Cape Town with Rhodes's approval Robinson no longer delayed the Matabele mission, cabling Whitehall that further investigation had shown Babayane and Mshete to be headmen after all, so they should be allowed to board ship for England.

The concession holders are accused of deception

By mid-January 1889 South African newspaper articles were arriving at Gubulawayo describing the concession. William Tainton, a long established trader translated the articles for Lobengula and added a few exaggerations of his own; telling the King that he had sold his country, that the concession-holders could dig for minerals anywhere they liked, including in and around kraals, and that they could bring an army into Matabeleland to depose Lobengula in favour of a new chief.

The King asked Rev Charles Helm to read the copy of the concession that had remained in Bulawayo to him; Helm did so and pointed out that none of what Tainton had said was actually reflected in the text. Lobengula then said he wished to dictate an announcement.

When Helm refused, Tainton wrote down the King's words: “I hear it is published in all the newspapers that I have granted a Concession of the Minerals in all my country to CHARLES DUNELL RUDD, ROCHFORD MAGUIRE [sic], and FRANCIS ROBERT THOMPSON.

As there is a great misunderstanding about this, all action in respect of said Concession is hereby suspended pending an investigation to be made by me in my country.

Lobengula”

This notice was published in the Bechuanaland News and Malmani Chronicle on 2 February 1889. A Council of the izinDuna and the Europeans in Bulawayo was announced but delayed until 11 March when Helm and Thompson were back in Gubulawayo.

As in the previous concession negotiations , Lobengula was not present, but remained close by. The izinDuna questioned Helm and Thompson at great length, but condemnation of the concession was led not by the izinDuna, but by Tainton and other concession-seekers who stated that the concession gave away all of the country's minerals, lands, wood and water.

William Mzisi, who had been to the Kimberley diamond fields said the mining would involve thousands of men rather than the few Lobengula had envisaged and argued that digging into the land amounted to taking possession of it: "You say you do not want any land, how can you dig for gold without it, is it not in the land?"

Thompson, backed by the missionaries, insisted that the agreement only involved the extraction of metals and minerals, but when questioned as to where exactly it had been agreed that they could mine; he confirmed that the concession permitted them to prospect and dig anywhere in the country.

Even the missionaries disagreed with each other. Rev Helm was accused of hiding the concessions true meaning from the King. The Reverends Bowen Rees and William Elliot at Inyathi Mission were asked if mining rights could be bought in other countries for the amount paid to Lobengula and said they could not. The izinDuna concluded that either Helm or the missionaries must be lying, their attempts to say men did not always hold the same opinions met with scepticism.

Daily Thompson and Maguire were treated with contempt by rank and file amaNdebele often receiving physical threats and suffering petty annoyances. Maguire was accused of poisoning a sacred spring when he used its water to clean his false teeth and accidentally dropped eau de Cologne into it and it was said he was involved in witchcraft and rode a hyena at night.

Thompson wrote: “Poor Maguire’s hair brushes, tooth brushes, clothes brushes, razors, cherry tooth paste and eau-de-Cologne were all confiscated. Life for him was hardly worth living without them.”

Rhodes fulfils the concession payments

Rhodes sent two shipments of Martini-Henry rifles to Bechuanaland in January and February 1889 and instructed Jameson, Dr Frederick Rutherfoord Harris and a Shoshong trader, George Musson, to transport them to Bulawayo. Lobengula however, although he accepted the monthly £100 in gold sovereigns for years afterwards, refused to take delivery of the rifles. Jameson placed the weapons under a canvas cover in their camp near Umvutcha, stayed at the kraal for ten days, and then went back south with Maguire in tow, leaving the rifles behind. They were only uncrated by Percy Crewe in November 1893 in time to be used against the Victoria and Salisbury columns at Shangani and Bembesi. [See the article on the Reminiscences of Percy Crewe of Nantwich Ranch, Hwange under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Lobengula revokes the concession and the colonial office waivers

In Gubulawayo in March 1889 Lobengula dictated a letter for James Fairbairn to write to Queen Victoria. In it he said he had never intended to sign away mineral rights and that he and his izinDuna revoked their recognition of the concession.

In London the colonial office had received protests against the Rudd concession from a number of businessmen and humanitarian societies and had come to the conclusion that it could not approve the concession because of its ambiguity as well as Lobengula’s objections.

Rhodes manoeuvres behind the scenes

Rhodes arrived in London in March 1889 to organise the amalgamation of interests just as the izinDuna were about to leave. To Gifford and Cawston’s dismay, Rhodes was originally angry with Maund, accusing him of creating problems, but eventually accepted that it was not Maund's fault. Now Maund was to go back to Gubulawayo pretending to be an impartial adviser and to try to sway Lobengula back in favour of the concession.

Rhodes wrote to Thompson:

Westminster Palace Hotel, 11th April 1889

My Dear Maguire and Thompson,

We have settled with Maund at the request of H.M. Government so as to have no opposition in interior they will then I believe support concession. You must work with him and we leave all details to your mutual brains I think you should read my old letter of instructions to you to him and in case faulty amend as you all think best.

You will be really a council and for goodness sake pull together or you will bogle all.

Yours, C.J. Rhodes

Formation of the British South Africa Company

From March 1889 Rhodes worked on amalgamating the interests of the London Syndicate and the Bechuanaland Exploration Company and the Exploring Company with his own and Alfred Beit’s interests that were represented the De Beers Syndicate and Gold Fields of South Africa.

These two groups had been in competition as described earlier, but now Rhodes was convinced that they would be commercially and politically more powerful if their interests were merged.

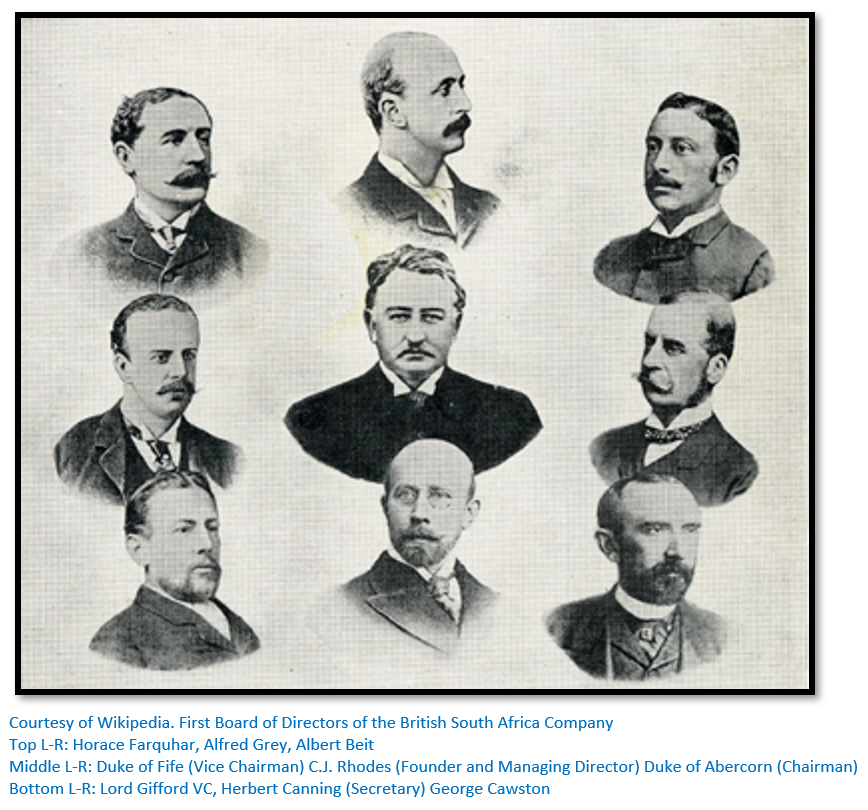

The British South Africa Company (BSACo) was incorporated in October 1888. Rhodes and Cawston recruited the Board of Directors. The dukes of Abercorn and Fife, chairman and vice-chairman were appointed to give the BSACo stature and prestige, but neither had any interest in Africa and both lacked commercial experience. Farquhar was a London financier, Albert Grey was nephew of Earl Grey a leading imperialist in late Victorian Britain, Gifford and Cawston were associated with commercial speculation in southern Africa. The company’s legal adviser was Lord Robert Cecil, the son of the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury.

Rhodes spent his time seeking out supporters for his cause between March and December 1889 when the Royal Charter was granted; he won support from other imperialists including Harry Johnstone, Alexander Bruce of the East Africa Company and eventually Lord Salisbury. By June the colonial office was dropping its suspicions about the Rudd concession, opposition in Parliament was muted and with the assistance of William Stead, editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, there was growing popular and political support for the idea of a chartered company in Zambesia.

However events hindered progress just as things were looking positive for the granting of the royal charter:

- Sir Hercules Robinson, the high commissioner and Rhodes’ supporter in Cape Town retired in May 1889; his retirement hastened by his attacks on parliamentary opponents of the Rudd concession and he was replaced by Sir Henry Loch. Rhodes told Shippard in a letter that "the policy will not be altered"

- Lobengula's letter renouncing the concession arrived in London. Maguire cast doubt on the letter’s authenticity by saying it lacked a missionary’s signature and requested that Thompson, still in Gubulawayo be called upon to say if Lobengula had been misled by rival concession-seekers.

How the royal charter was obtained

Thompson gives an account in his autobiography saying that when Rhodes arrived in England he saw Baroness Burdett-Coutts, unfolded his plan to her and asked for her help. The Baroness was widely-known as ‘the richest heiress in England’ and spent most of her wealth on scholarships for the poor, endowments and a wide range of charitable causes including improving the condition of indigenous Africans. She advised Rhodes to consult the Rev. Dr Bruce in Edinburgh who was very involved in central African missionary work.

After reading the Rudd concession Dr Bruce said: “This is good enough for me, I will help you.” Rhodes and Dr Bruce returned to London and a reception held by Baroness Burdett-Coutts which was attended by the Prince of Wales (later acceded to the throne as Edward VII) Rhodes was presented to Albert Edward and told him about the Rudd concession and was told he would use his influence with his mother Queen Victoria.

Soon afterwards Rhodes accompanied the Prince of Wales to Balmoral where he laid the concession and his scheme before Queen Victoria. The Queen said she would discuss it with her ministers and Rhodes returned to London and discussed the scheme further with the Conservatives and Lord Salisbury, then Prime Minister.

Thompson says that it was arranged he would stay in Gubulawayo until he received from Rhodes the code word ‘Runnymede’ which would signify: “Charter signed and sealed; position consummated; matters little what happens your end.”

Rhodes wins the royal charter

Despite all the initial setbacks encountered, the royal charter came into effect on 20 December 1889, initially for a period of twenty-five years and later extended for a further ten years.

Colonial office concerns of Portuguese and German expansionism in Africa were a major factor in Rhodes's success plus his financial clout meant that the British government saw that they were not being asked to finance the acquisition of Zambesia and that the BSACo was taking on all the risk and responsibilities of this territorial acquisition.

Rhodes had returned to the Cape in August 1889 leaving Cawston to organise setting -up of the administration of the BSACo in London. Rhodes wrote to Maund, soon after reaching Cape Town: "My part is done…the charter is granted supporting Rudd Concession and granting us the interior ... We have the whole thing recognised by the Queen and even if eventually we had any difficulty with King [Lobengula] the Home people would now always recognise us in possession of the minerals[;] they quite understand that savage potentates frequently repudiate."

The British South Africa Company, the charter company, now had its royal charter which confirmed the legitimacy of the Rudd concession's in the eyes of the colonial office.

Thompson faces the wrath of the amaNdebele

Thompson says he was insulted in every way by the izinDuna and the Europeans at Gubulawayo even threatened to shoot him. The council insisted on Thompson sending for the original concession document, but Rhodes advised that it was at the colonial office forming the basis for the royal charter. When it did finally arrive Thompson buried it in a pumpkin gourd with some maize seed telling his servant Charlie that if he was killed, the growing maize would mark the spot where the concession was buried.

As time went by the amaNdebele become more agitated and came to ask the King if it was true that the white dog Thomoson (Thompson) had bought the land. The other European concession-seekers deliberately misrepresented the concession particularly in the passage: “Whereas I have been much molested of late by divers persons seeking and desiring to obtain grants and concessions of land and mining rights in my territories.”

At a meeting with three hundred izinDuna which lasted from 7am until 5pm Thompson was asked from whom he had bought the country. He replied: “Matebili, did I not tell you when first I came into this country, about a year ago, that we were not farmers and wanted no land, cattle or grass, but that we wanted the gold in the stone?”

Alarmed by these rumours Lobengula looked for a scapegoat. The chief councillor inDuna Lotshe Hlabangana who had advised the King to take the thousand rifles in exchange for gold was condemned by the izinDuna. Thompson says: ‘I saw the poor old fellow stand erect. He handed his snuffbox to a man standing near. He was taken outside the council kraal and on kneeling down he said: “Do as you think fit with me. I am the King’s chattel.” One blow from the executioner’s stick sufficed; one smart blow on the back of the head. Thompson turned to the half-dozen Europeans who sat away to the right, scum as he regarded them, and said: “Who is responsible for this? You, who have told all these villainous lies of what will happen when the charter is granted.”

Three hundred men, women and children of Lotshe’s extended family were executed. Lobengula who lived to regret the decision remorsefully remarked: “Yek’ uLotshe!” a remark which loosely translates to: “Lotshe’s advice has been vindicated” shortly before his death in 1894.

Lotshe was made the scapegoat to protect Lobengula from the rising tide of suspicion that he had traded away their rights in their land.

Thompson makes a bolt for it

Next day Thompson decided to ride over to Hope Fountain to discuss events with Rev Helm and had just started off when an amaNdebele horseman caught up with him and said: “Tomoson, the King says the killing of yesterday is not yet over.” Whilst considering the message he observed young amaNdebele in war dress approaching him.

Thompson believed he was a friend of the King but understood that Lobengula was now so hard pressed that he was playing for his own safety and that he could do no better service than to disappear until the storm blew over.

He took their fastest horse, without a saddle and with improvised bridle from the mule trap and crossed the ford over the Umgusa river and rode west. With no food or water, at sunset he tied his horse to a tree, climbed it and spent the night in its branches. Next day he rode until the horse was knocked-up and then walked and ran all day in the semi-desert and found a water hole at sunset which gave him dysentery the following day. Luckily on the third day he met some Makalaka and swapped his pocket knife for a meal of mealie-meal; then a trader with a mule wagon gave him a lift to Shoshong and from there he travelled to Mafeking.

Then returns to Gubulawayo

Despite not having seen his family for fifteen months, Rhodes and Sir Henry Loch both requested that Thompson return urgently to Gubulawayo. Jameson had received instructions to go to Gubulawayo if Thompson refused to return, but Jameson did not know Lobengula, did not know the language and had no experience in these matters, so Thompson agreed to escort him.

On their arrival back in Gubulawayo those concession-seekers who believed they held prior claims were paid off by Jameson with a few thousand pounds; Thompson unearthed the concession and gave it to the King who said to the Europeans around him: “What have you got to say? There is the paper” and their spokesman answered: “King, this document is all right. We were wrong in all we said about Thompson.” The King smiled and rubbing his hand across his mouth said: “Tomoson has rubbed fat on your mouths. All you white men are liars. Tomoson, you have lied the least.”

The King handed back the concession and a message was sent to Rhodes: “Things are well. Send me a peace offering.” The Duke of Fife despatched two jet black bulls as gifts but when Thompson saw them at Cape Town he explained they could not possibly be sent; the colour signified to the amaNdebele almost a declaration of war and they were given to Sir James Sivewright, a strong Rhodes political ally.

Alfred Grey, another BSACo director sent two snow-white bulls which were delivered to Lobengula as a peace offering.

The land issue

Thompson claims that Rhodes told him he did not want the gold per se, or the land, but rather territorial administrative powers. Nor did Thompson imagine that the concession entitled the BSACo to rights in the land. When discussing the matter with Lobengula he used a metaphor in likening his country to a cow and said: “King, the cow is yours. If she dies the skin is yours, if she calves, the calf is yours. I only want the milk.”

The threat from the Lippert concession

Edward Renny-Tailyour, had been petitioning Lobengula since early 1888 and it came as a great surprise to Rhodes when in April 1891, Renny-Tailyour announced he had negotiated an agreement on behalf of Lippert with Lobengula for an upfront payment of £1,000 and £500 annually. The concession granted Lippert exclusive rights to manage lands, establish banks, mint money, and conduct trade in BSACo territory.

| 1891 | April - Renny-Tailyour representing Edourd Lippert announced he had an agreement with King Lobengula the exclusive rights to manage lands, establish banks, mint money, and conduct trade in the territory of the Chartered Company in return for £1,000 and an annual payment of £500 |

Rhodes had previously tried to settle with Lippert, an estranged cousin of Beit, without success.

The authenticity of the Lippert concession was queried because the only witnesses to have signed it were inDuna Mshete and Renny-Tailyour's associates, one of whom then soon stated that Lobengula had believed the concession was with Theophilus Shepstone's son, "Offy" Shepstone and that Lippert was merely acting as an agent.

Rhodes stated the defects made the Lippert concession a fraud. Loch, backed by the colonial office, declared that if Lippert tried to gazette his agreement, he would issue a proclamation warning of its infringement on the Rudd concession and the company's charter and threatened Lippert with legal action. However they quickly saw that the Lippert's concession included land rights from Lobengula, privileges not included in the Rudd concession and this would be invaluable to the BSACo in ensuring the legality of any future occupied territory in Mashonaland.

Rhodes changes tactics and buys up Lippert’s concession

So despite Rhodes having initially turned down Lippert’s offer to sell for £250,000 in cash or shares at par, he agreed with Beit not to take the legal route of a drawn-out and expensive court case which they might not win and instead, asked Beit to attempt a deal.

After two months of fruitless talks Rudd took over the negotiations and terms were finally agreed on 12 September 1891; the BSACo would take over Lippert’s concession provided he returned to Bulawayo and had it properly formalised by Lobengula. In return Lippert would receive seventy five square miles (one hundred and ninety square kilometres) of land of his choice in Matabeleland with full land and mineral rights and thirty thousand ordinary shares in the BSACo.

Key to the scheme was Lobengula’s belief that Lippert was acting against Rhodes rather than on his behalf. Moffat was not happy with this deceit but agreed not to interfere having concluded that Lobengula was just as untrustworthy as Lippert. With Moffat looking on as a witness, Lippert delivered his side of the deal in November 1891, extracting from the Matabele King the exclusive land rights for a century in the BSACo’s operative territories, including permission to lay out farms and towns and to levy rents. The amaNdebele remained unaware of this deception until May 1892.

Postscript

Francis Thompson only ever visited Matabeleland again in 1904. He was on the railway platform at Figtree when he met one of Lobengula’s izinDuna who said: “Oh Tomoson, how have you treated us, after all your promises, which we believed?” Thompson says: “I had no answer.”

The Rudd Concession

30th October 1888

Know all men by these presents that whereas Charles Dunell Rudd, of Kimberley; Rochfort Maguire, of London; and Francis Robert Thompson, of Kimberley; hereinafter called the Grantees, have covenanted and agreed, and do hereby covenant and agree to pay to me, my heirs and successors, the sum of 100 pound sterling, British currency, on the first day of every lunar month; and, further, to deliver at my Royal Kraal one thousand Martini-Henry Breech-loading Rifles, together with one hundred thousand rounds of suitable bull cartridge, five hundred of the said rifles and fifty thousand of the said cartridges to be ordered from England forthwith and delivered with reasonable dispatch, and the remainder of the said rifles and cartridges to be delivered so soon as the said grantees shall have commenced to work mining machinery within my territory; and further, to deliver on the Zambezi River, a steamboat with guns suitable for defensive purposes upon the said river, or in lieu of the said steamboat, should I so select, to pay to me the sum of five hundred pounds sterling, British currency.

On the execution of those presents, I, Lobengula, King of Matabeleland, Mashonaland and other adjoining territories, in the exercise of my sovereign powers, and in the presence and with the consent of my Council of Indunas, do hereby grant and design until the said grantees, their heirs, representatives and assigns, jointly and severally, the complete and exclusive charge over all metals and minerals situated and contained in my Kingdoms, principalities, and dominions ,together with full power to do all things that they may deem necessary to win and procure the same, and to hold, collect, and enjoy the profits and revenues, if any, derivable from the said metals and minerals, subject to the aforesaid payment; and, whereas, I had been much molested of late by diverse persons seeking and desiring to obtain grants and concessions of land and mining rights in my territories, I do hereby authorise the said grantees, their heirs, representatives, and assigns to take all necessary and lawful steps to exclude from my Kingdoms, principalities and dominions, all persons seeking land, metals, minerals, or mining rights therein, and I do hereby undertake to render them such needful assistance as they may, from time to time, require for the exclusion of such persons, and to grant no concessions of land or mining rights from and after this date without their consent and concurrence; provided that, if it anytime the said monthly payment of one hundred pounds shall be arear for a period of three months, then this grant shall cease and determine from the date of the last made payment; and, further provided that nothing contained in these presents shall extend to, or affect a grant made by me of certain mining rights in a portion of my territory south of the Ramakoban river, which grant is commonly known as the Tati Concession.

This given under my hand the 30th day October in the Year of our Lord 1888, at my Royal Kraal.

(Sgd.) LOBENGULA HIS X mark

Witnesses:

(Sgd.) CHAS D. HELM

J.F. DREYER

(Sgd.) C.D. RUDD

ROCHFORT MAGUIRE

F.R. THOMPSON

Copy of Endorsement on the Original Agreement

I hereby certify that the accompanying document has been fully interpreted and explained by me to the Chief Lobengula and his full Council of Indunas, and that all the constitutional usages of the Matabele nation had been complied with prior to his executing the same.

Dated at the Umgusa River this 30th October 1888

CHAS D. HELM

References

Botswana Daily News / Old Tati: Bechuanaland’s ancient commercial centre - http://www.dailynews.gov.bw/news-details.php?nid=39060

Sunday Standard 25/02/2018 - ‘Tati concession was colonial generosity to private companies with the property of local people’

R. Sampson. White Induna; George Westbeech and the Barotse People.

P.T. Mgadla, F. Morton, J. Ramsay. Historical Dictionary of Botswana. Scarecrow Press Inc. 2008

F.C. Selous. Travel and Adventure in South-East Africa. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1972

F.R. Thompson, edited by Nancy Rouillard. Matabele Thompson, an Autobiography. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1977

W.R. Warhurst. Concession-seekers and the Scramble for Matabeleland. Rhodesiana Publication No 29, December 1973