Why Lobengula sent envoys to Queen Victoria in the late nineteenth century

Neil Parsons in an essay entitled “No longer rare birds in London” explored the Colonial office’s motivation for encouraging Zulu, Ndebele, Gaza and Swazi envoys to visit England in the period 1882 to 1894 - this article discusses each visit but focuses particularly on the amaNdebele envoys Mshete and Babayane who visited London in March 1889.

Sending one’s personal envoys was a long-established political strategy; appealing to the monarch over the heads of local authorities was fairly commonplace in medieval England and in India before the arrival of the East India Company. This article shows that the African envoys continued the tradition of ceremonial gift-giving and made formal submissions to express loyalty to Queen Victoria, but at the same time tried to advance their own strategic goals.

S. Carter and M. Nugent the editors of Mistress of Everything: Queen Victoria in Indigenous Worlds state: “indigenous people began to see the Queen as an alternative source of authority, as someone who could help them in their battle with settler governments and people, especially in their quest for the return of their land….Loyalty and devotion to the Queen was promoted and nurtured among all her scattered subjects and colonists, not just the Indigenous people of the Empire. According to Imperialists, she generated a ‘mystic reverence’ amongst all her people. She was the emblem of imperial unity as well as maternal love, standing watchful guide over her magnificent realms.”

An African perspective

For the African nations under consideration below who sent envoys to Britain between 1880 and 1900 it was a period of profound change during the ‘scramble for Africa’ as they assessed the relative strengths of the great powers in order to form the most secure alliances as all were under the threat of white settlers. Those nations discussed below include:

- the Zulu nation being threatened by Natal settlers

- the Gaza under Gungunhana being pressurised by the Portuguese

- the Swazi nation was vulnerable to encroachment by the Transvaal Boers

- Tswana chiefs when under threat of administration by the British South Africa Company (BSACo)

- the amaNdebele by the BSACo and other concession seekers

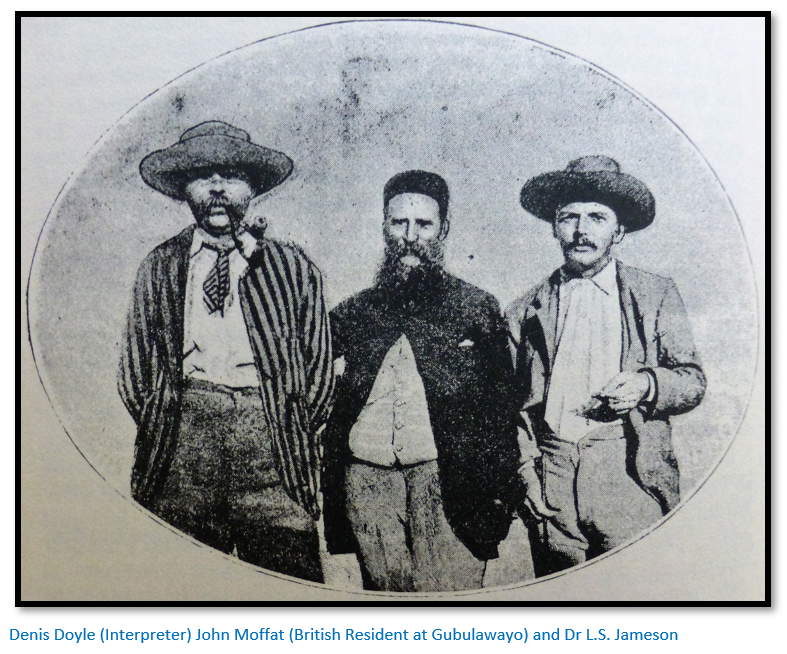

These nations all shared various dialects of the same isiZulu language and it was also spoken by the interpreters such as Denis Doyle who accompanied the Gaza envoys and Johan Colenbrander who accompanied the amaNdebele envoys.

The envoys’ primary motivation in coming to Britain was to lessen or reduce the wave of European imperialism sweeping over the African continent and in Lobengula’s view they were: “as much spies engaged in intelligence gathering as they were diplomats seeking political advantage.” However Parsons’ argues that the colonial office was unable to listen to the envoy’s arguments as their officials were in the thrall to ‘the white men on the spot’ such as Rhodes, Sir Theophilus Shepstone and Sir Sidney Shippard.

Early attempts to send envoys

In his article Parsons states the threat of encroachment was not new to many of the indigenous nations in the late nineteenth century as Boer settlers had attempted to penetrate the lands of the Khoe and Xhosa on the eastern Cape frontier. In the 1850’s the Sotho, Korana and Tswana nations faced the same threat and in 1882 – 1883 new threats from the Boer Republics of Stellaland and Goshen.

The Tswana rulers were heavily influenced by Robert Moffat, the Scottish missionary, living at Kuruman north of the Vaal river, and looked to Britain to help them against the Boer freebooters. Chief Sechele of the Kwena made an effort to petition Queen Victoria but ran out of funds and only reached Cape Town.

King Moshoeshoe of Basutoland, present-day Lesotho, hoped that Britain would protect him against the depredations of the Orange Free State Boers. He told the nation that Queen Victoria was: “sitting on the top of a high mountain, looking down on us, her children…someday, Queen Victoria will come back among us. On that day I shall rejoice as I rejoice at the rising of the sun.”

In 1869 he sent envoys to Britain led by his mission educated son Tsekelo, but the Colonial office did not grant them an audience with the queen.

The Colonial Office Agenda

In general terms the itineraries that the colonial office drew up for the visits of African envoys all had the following diplomatic objectives in common:

- To ensure the envoys saw and inspected evidence of overwhelming British military capability either at military manoeuvres at Aldershot or on the live firing range at Shoeburyness

- To overawe the envoys by the sheer scale and grandeur of the royal residences at Windsor Castle or at Osborne House

- To inspire the envoys with the authority of Queen Victoria ‘the great white queen’

- To demonstrate Britain’s economic power by arranging visits to factories or the Woolwich arsenal

- To arrange visits to Westminster Abbey and Madame Tussaud’s which reinforced Britain’s royal and military reputation

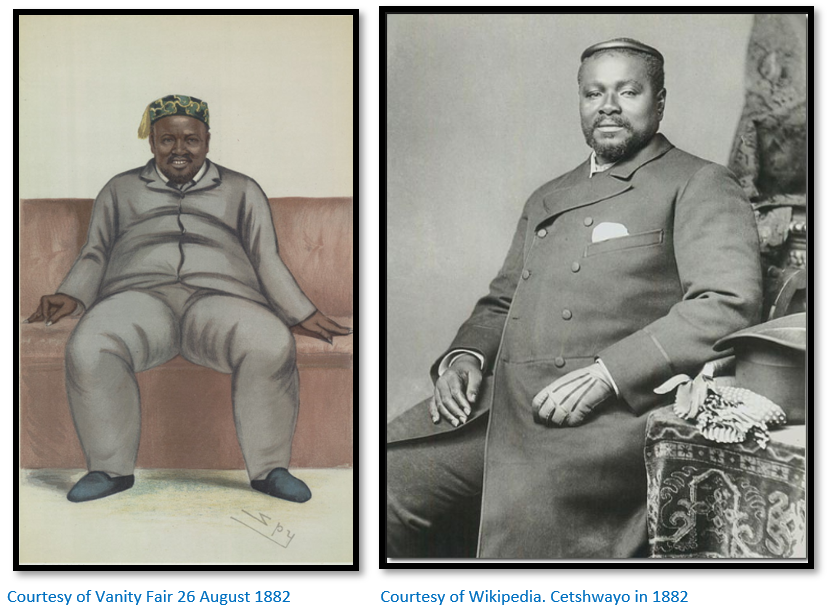

Zulu King Cetshwayo’s visit in 1882

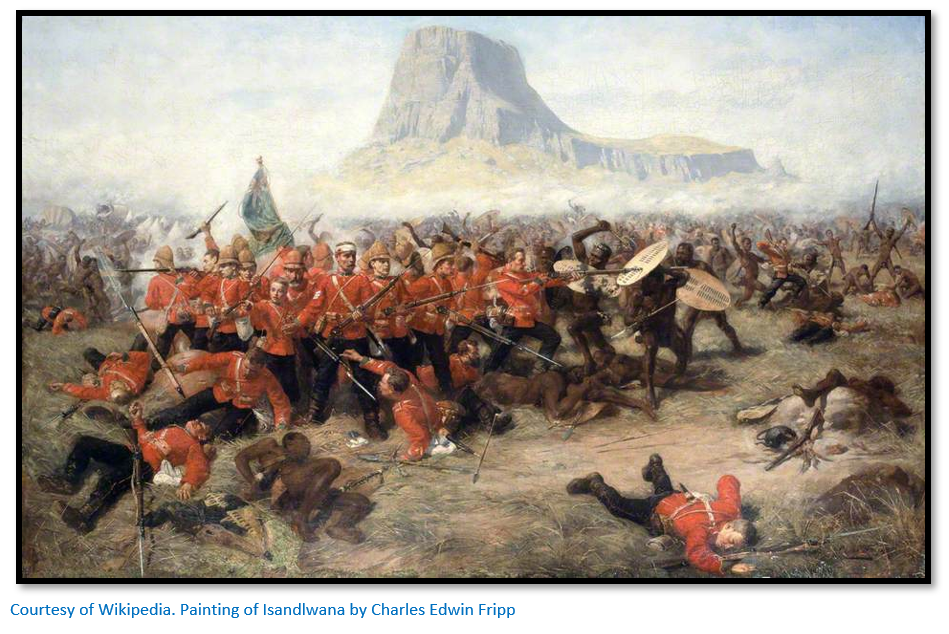

Cetshwayo stayed for a month in Britain from 3 August to 2 September 1882 with three Indunas and two attendants and interpreter and this was probably the most publicised visit as the memory of the decisive Zulu victory in 1879 at Isandlwana over the British forces was still fresh in the public memory. British casualties here were 1,300; including 57 officers, 727 regular soldiers and 471 African Natal native contingent and 133 European colonial troops with possibly 1,000 – 2,500 Zulu killed and 1,000 wounded.

After his capital Ulundi was taken and torched by Lord Chelmsford’s forces on 4 July 1879, Cetshwayo was deposed and sent into exile at Cape Town.

On Cetshwayo’s arrival in England The Times opinioned that he should understand: “the futility of armed resistance to British power” and be overwhelmed: “with a sense of [our] boundless resources.” Accordingly he was taken by the colonial minister Lord Kimberley to visit Queen Victoria where he was told: “she respected him as a brave enemy and trusted that he would become a firm friend.” This was followed by a tour of the royal gun factories at the Woolwich arsenal: “I have seen the wonders of the English nation. I have witnessed where England gets her power from and of the might of the works conducted here.” Afterwards he saw a delegation from the National Temperance League whom he told: “the beer which we use is actually a food – it is a gruel…not like your spirits and your intoxicants which are death.”

Cetshwayo’s visit to the queen lasted only thirteen minutes, her journal only records a polite conversation taking place and his petition against the incorporation of his Zulu Kingdom into the Natal colony ultimately fell on deaf ears and was unsuccessful; at the colonial office he was told that he would be allowed home but would not rule over those chiefs who had allied themselves with the British. Following his 1879 – 1882 exile from Zululand and his British visit, he was allowed to return to Zululand. However blood feuds and civil wars soon broke out, his new Ulundi capital was attacked and Cetshwayo was wounded but managed to escape and died at Eshowe on 8 February 1884.

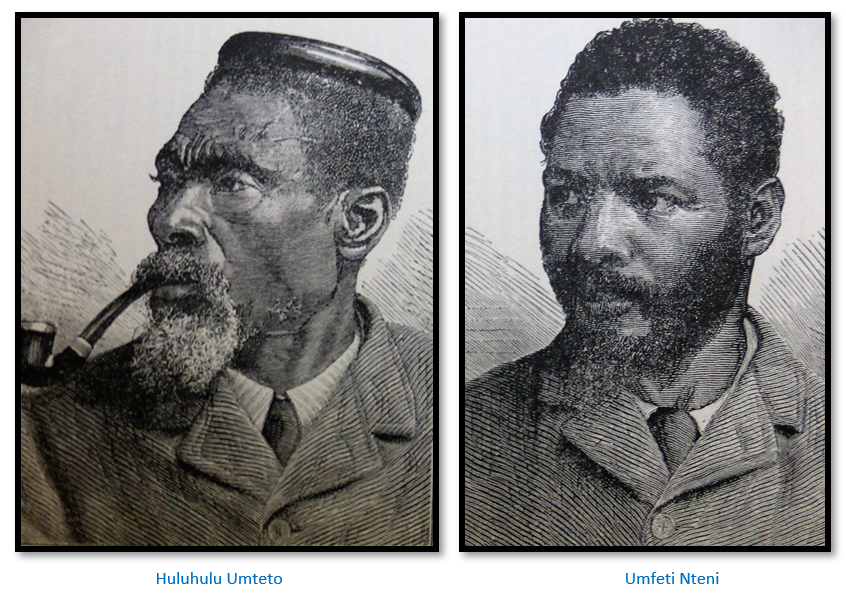

Gungunhana sends envoys from Gaza to Britain in 1891

Given the choice between the two evils of Portugal and England seeking territorial dominance over his Gaza Kingdom, Chief Gungunhana of Gaza (“the lion of Gaza”) declared he preferred the English over the Boers from the Transvaal and the Portuguese: “who made the men and the women and the children silly with drink.”

Rhodes through the BSACo tried every trick in his power to seize Gazaland from the Portuguese and ensure territorial access to the Indian Ocean [for a detailed account see the article How Mutare and Manicaland were annexed from the Portuguese under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Gungunhana sent two Indunas as envoys, Huluhulu Umteto and Umfeti Nteni, who arrived in Plymouth on 23 May 1891 accompanied by Denis Doyle, a BSACo employee and they were the subject of a well-organised publicity campaign by the same company which included newspaper interviews with the Pall Mall Gazette which supported Rhodes’ imperial aims. The aim was to gather support for a British intervention in Gazaland, the southern central portion of Mocambique. Umteto declared: “I am the eyes and ears of Gungunyana the King, and I know the heart of Gungunyana as if it were my own heart, and I have come to bring the word of Gungunyana to the great White Queen.”

Lord Salisbury was furious, but Rhodes maintained it was merely a private visit. The colonial office took charge of their itinerary with a visit to Westminster Abbey followed by a trip to Madam Tussaud’s waxworks and on Tuesday 2 June the two envoys and Doyle met Lord Salisbury at the foreign office rather than the colonial office. The choice of venue was important as it showed they were being treated as Portuguese colonial subjects rather than as British subjects.

Other visits included the military tournament, the House of Commons and London Zoo as well as a factory making guns; they watched the military manoeuvres at Aldershot and the great steam hammer at Woolwich arsenal, plus gunnery practise at Shoeburyness firing range. The purpose of all these visits was to impress the envoys with the might of Britain’s economic and military power. They had a short meeting with Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle and asked for her protection against the forces that were threatening the Gaza nation. She presented them with a silver cup inscribed with; “To Gungunyana from Queen Victoria.”

However all of Rhodes’ expectations of gaining the territory of Gazaland were dashed by the new Anglo-Portuguese treaty of 11 June 1891 which replaced the treaty of August 1890 and unambiguously defined the boundary between Mocambique and British territory as running north – south along the Nyanga mountains “the divide” thus locating Gazaland firmly in Portuguese territory.

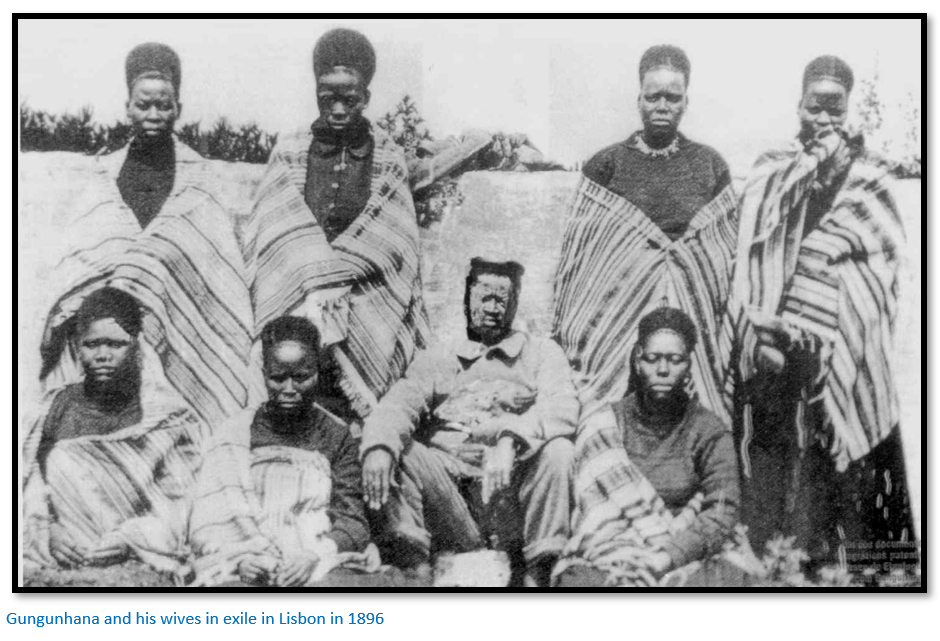

Gungunhana rewarded the BSACo in 1893 with a concession that covered that part of Gazaland that was situated on the western side of the border but paid the price in 1895 when he was defeated by a Portuguese force under General Joaquim Mouzinho de Albuquerque and lived out the rest of his life in exile, first in Lisbon, but later on the island of Terceira in the Portuguese Azores.

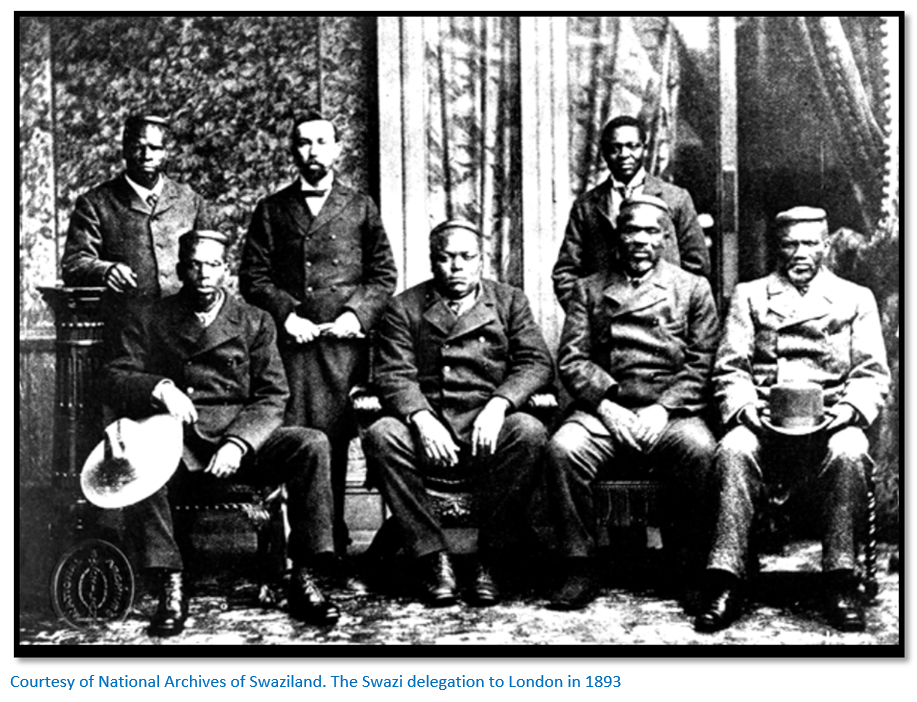

Swazi envoys in England in 1894

Mbandzeni ruled as King of Swaziland from 1875 until 1889; on his death Swaziland came under the rule of two regent queens, the most powerful being the deceased King’s mother, Labotsibeni. At the same time the colonial office came to an understanding with Paul Kruger, the State President of the Transvaal Republic, that he would have the right to expand on the eastern boundary with Swaziland provided he prevented any Boer trekkers from interfering with the BSACo’s territorial expansion into Mashonaland.

The landlocked Transvaal Republic wished for territorial control over Swaziland to give it access to the coast between Portuguese Mocambique and British Natal.

After being pressured by the Transvaal Republic in 1893 Labotsibeni appealed to the Colonial office: “We consider we are the Queen of England’s children. You have protected us ever since the Zulu war and it is now with sorrow that we learn that our Mother the Queen wants to send us from under her wing and hand us over to the hawks that will devour us.”

The deceased King’s half-brother, Prince Longcanga and five others from the ruling class, plus three attendants and James Stuart as translator were nominated as envoys and arrived by sea at Southampton on 28 October 1893. The Westminster Gazette interviewed Cleopas Kunene and reported he said: “Tell your people. Then they will listen to us and not let us be killed by the Boers. We want you English to rule over us. You are just, you do right. Who can withstand you? There is nothing for you to learn, you can teach the world…The chiefs are strong in their belief that their journey will be successful. Their country’s independence will be preserved and Swaziland will be happy again.”

Their first three days of appointments were with the colonial minister Lord Ripon and his deputy minister Sydney Buxton. Then they visited Wolff’s Circus playing in Oxford Street and the pleasure gardens of Crystal Palace. A week later they visited Aldershot accompanied by George Baden-Powell (Robert’s elder brother) but did not view a cavalry charge as the weather was poor, instead watching mounted and dismounted exercises in the gymnasium. The next day was another interview with Lord Ripon before a visit to Queen Victoria at Windsor who gave them shawls for the two Swazi queens and wrote in her journal: “I received four Swazi envoys, sent by the Queen of the Swazis. The Blues were drawn up in the corridor and the reception was much the same as on former occasions when African Indunas have been received.”

On Friday 16 November they presented a memorandum to the colonial office pledging allegiance to Queen Victoria but were told in the afternoon that their memorandum could not be accepted as there was an international treaty already in place with the Transvaal Republic and the party were ordered to return to Swaziland the next day.

In February 1895 the Transvaal Republic took over Swaziland as a protectorate; which decision was reversed in 1904 when Swaziland became a British protectorate in return for supporting Britain in the Anglo-Boer War of 1899 – 1902

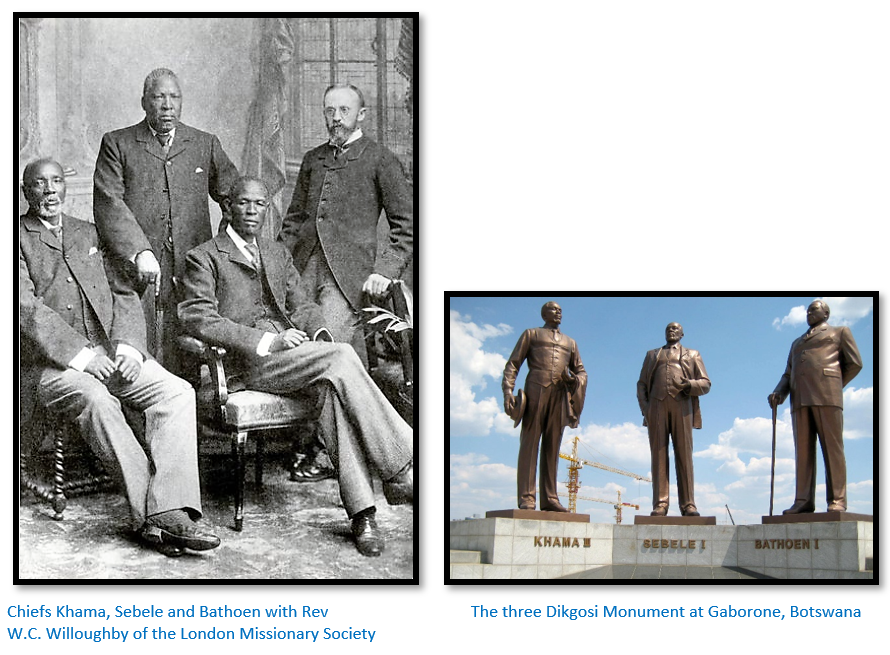

Tswana Chiefs as envoys in England in 1895

In 1885 the southern part of Bechuanaland was administered as the crown colony of British Bechuanaland, but from 1895 Rhodes had stated it was to be incorporated into the Cape Colony and the northern part was to be administered as the Bechuanaland Protectorate under the administration of the BSACo.

However the three Tswana chiefs Khama, Sebele and Bathoen decided to visit London to protest to the new colonial minister Joseph Chamberlain and spoke at many public meetings including Leicester where Khama said: “We say why should the home [imperial] Government hand us over to the other people without asking us? (Hear, hear) They hand us over like an ox, but even the owner of an ox looks to where the ox will get grass and water, land, that sort of thing (Applause) I think they ought to have asked us, and found out what we think about it…We were progressing very much under the Imperial Government , but now you are teaching us the word of war and I think these things ought to cease.”

They saw the queen and were successful in their efforts in fending off BSACo’s efforts to control the Bechuanaland Protectorate which remained under British rule until its independence in 1966. The southern part was administered as the crown colony of British Bechuanaland from 1885 until its’ annexation by the Cape Colony in 1895.

Sebele said of the Royal Horse Guards on his visit to Windsor Castle: “I thrust my finger almost into his eye to make certain he was a living being…To my great surprise he never flinched, but merely rewarded me with a smile.” The queen recorded in her journal: “They brought offerings of skins of leopards and jackals and I gave them New Testaments and my photographs handsomely framed and Indian shawls for their wives.”

Lobengula’s envoys to Britain in 1889

In 1882 Lobengula was warned by Piet Joubert, then Commandant-General of the army of the South African Republic that: “An Englishman once [he] has your property in his hand, then he is like a monkey that has its hands full of pumpkin seeds – if you don’t beat him to death, he will never let go.”

White hunters, missionaries and British and Boer concession-seekers increasingly arrived at his kraal in the 1880’s at Umvutcha and Lobengula remarked to the Rev C.D. Helm: “Did you ever see a chameleon catch a fly? The chameleon gets behind the fly and remains motionless for some time, then he advances very slowly and gently, first putting forward one leg and then another. At last, when well within reach, he darts his tongue and the fly disappears. England is the chameleon and I am that fly.”

On 11 February 1888 Lobengula signed a treaty of friendship with Britain that was counter signed by J.S. Moffat as assistant-commissioner pledging that he [Lobengula] would not sign any treaties or sell or cede any part of his nation without the knowledge and agreement of the British High Commissioner for South Africa.

There were two major rival concession-seekers at Umvutcha; the BSACo headed by Cecil Rhodes and the other represented by the Bechuanaland Exploration Company which had two of Victoria’s sons-in-law as directors and was Lobengula’s preferred choice…both company’s claimed to have the backing of the British Government.

Additionally other parties were seeking concessions from Lobengula and the Portuguese represented by Capt. Joachim Carlos Paiva de Andrada and Lieut. Victor Córdon were in Mashonaland making treaties with local chiefs and claimed territorial rights as far as the Umfuli, now Mupfure river. [For detail see the article How Mutare and Manicaland were annexed from the Portuguese on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] In the south, Boers from the Transvaal Republic threatened to cross the Limpopo river.

Rudd Concession

On 30 October 1888 after much persuasion Lobengula signed the Rudd Concession which was co-signed by Rudd, Maguire and Thompson on behalf of the BSACo and witnessed by Helm and Dreyer.

Unfortunately for Lobengula, Maund and his fellow directors in the Bechuanaland Exploration Company were persuaded by Rhodes to amalgamate their common economic interests and with colonial office backing formed the BSACo which received the royal charter in 1889 on the strength of the Rudd Concession and the financial strength of Rhodes’ personal wealth.

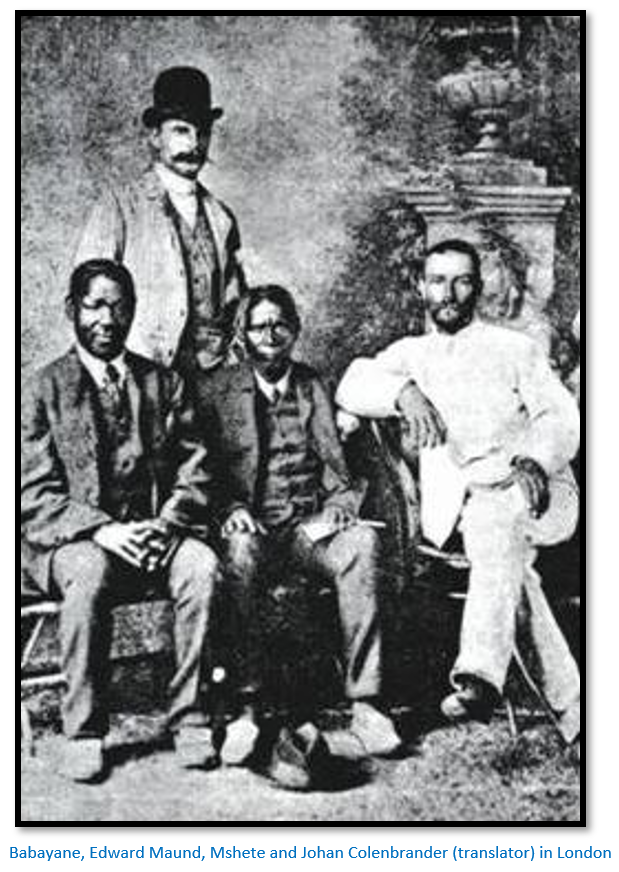

Maund conducts the envoys Mshete and Babayane to Queen Victoria

Mathers in Zambesia; England’s Eldorado in Africa quotes E.A. Maund’s account of events. According to Maund, who was the local representative of the Bechuanaland Exploration Company and also the correspondent for The Times, he asked for a gold mining concession in Mashonaland from Lobengula who was receptive to the idea of the English keeping the Portuguese at bay and replied: “But Maundy, I want you to do something for me first. They tell me that the white queen no longer exists and that is why the white men come up here and bother me. I want you to take two of my men home to see whether the white queen is living.” After some thought Maund said he agreed to the King’s request as there was no imperial government representative in the country, John Moffat being elsewhere.

Next day Lobengula dictated a letter to the queen which Maund wrote down and which was sent to Rev Charles Helm at Hope Fountain Mission because he was trusted by Lobengula. Helm deleted a clause requesting a protectorate and changed it to a request to the queen for help against Lobengula’s enemies. The text of the letter was: “Lobengula desires to know that there is a queen. Some of the people who come into this land and tell him that there is a queen, some of them tell him there is not. Lobengula can only find out the truth by sending eyes to see whether there is a queen. The Indunas are his eyes. Lobengula desires, if there is a queen, to ask her to advise and help him, as he is much troubled by white men who come into his country and ask to dig gold. There is no one with him whom he can trust and he asks that the queen send someone from herself.”

Mshete (aged 60 years) and Babayane (aged 75 years) were to accompany Maund as Lobengula’s envoys: “These are the men who are to be my eyes, ears and mouth.” Lobengula provided some cattle for the road and agreed to pay all expenses amounting to about £600. Maund says: “His majesty thereupon got into his wagon and took down a handkerchief full of English sovereigns, some of which had been obtained by the Rudd Concession. He then counted out a sum for the expenses of his embassy, though it was not quite sufficient.”

They left Gubulawayo in late November 1888. Maund bought clothes for the envoys at Tati and Shoshong and suits at Pretoria. At Kimberley they boarded the train and were terrified when it moved at speed. Maund turned to Babayane and said: “What a King’s soldier and afraid?” and to show he was not afraid Babayane put his head out the carriage window for half an hour!

The party were delayed in Cape Town for two weeks; Sir Hercules Robinson cabled Lord Knudson on 2 February 1889 as follows: “I have had long interviews with the two Matabele who are described as Headmen in a letter received from Lobengula; they say Lobengula has been so often deceived by Europeans of different nations telling him there is no such person as the Queen, others say that they come from the Queen, that they want to know whether England and the Queen exist; they have no other message. This as far as they are concerned is the sole object of their mission. They are to see with their own eyes and go back and report to the King; they say they will be killed on their return if they do not cross the ocean. I advise that they may be allowed to proceed. They have funds for such purpose. Mission is most anxious to proceed by next mail.”

The waves on the coast the Indunas likened to impis rushing up to the King at a review. Their steamer, the Moor, they called the great kraal that pushes through water and they arrived in London in late February 1889 and were quickly met by the colonial minister Lord Knutsford who took them to the queen at Windsor. Like many of the envoys before and after them they were overwhelmed by the grandeur of the royal palace. The size of the Life Guards in the corridors astonished them: “These soldiers are only put up for show…They are so big and stiff - they cannot be alive” said Mshete. Replied Babayane: “Oh yes, they are – I saw their eyes move.”

Queen Victoria presented each of them with gifts of snuff and they were taken on a tour of London’s attractions including the Alhambra musical variety theatre, museums and art galleries, Madame Tussaud’s waxworks and the London Zoo and the gold vaults of the Bank of England.

However the occasions that were really intended to make a deep impression on the amaNdebele envoys were the displays of military strength. The naval ships at Portsmouth followed by artillery live-fire at Shoeburyness firing range which was followed up by visits to Woolwich arsenal and Chatham naval dockyard with the grand finale being army manoeuvres at Aldershot. Ten thousand soldiers took part which included a cavalry charge on the artillery. They stood on their seats to watch every movement of the troops and said: ”Come and teach us how to drill and fight like that and we will fear no nation in Africa.”

A last interview followed with Lord Knutsford after which a great crowd of well-wishers saw them off on their journey home. The following was the full reply of Her Majesty to Lobengula through Lord Knutsford; “I, Lord Knutsford, one of Her Majesty's principal Secretaries of State, am commanded by the Queen to give the following reply to the message delivered by Mshete and Babayane. The Queen has heard the words of Lobengula. She was glad to receive these messengers and to learn the message which they have brought. They say that Lobengula is much troubled by the white men who came into his country and ask to dig for gold and that he begs for advice and help. Lobengula is the ruler of his country and the Queen does not interfere in the government of that country, but as Lobengula desires her advice, Her Majesty is ready to give it, and having therefore consulted her principle Secretary of State holding the seals of the colonial department now replies as follows;

In the first place the Queen wishes Lobengula to understand distinctly that Englishman who have gone out to Matabeleland to ask leave to dig for stones have not gone with the Queen's authority and he should not believe any statements made by them or any of them to that effect. The Queen advises Lobengula not to grant hastily concessions of land, or leave to dig, but to consider all applications very carefully. It is not wise to put too much power into the hands of the men who come first and to exclude other deserving men. A King gives a stranger an ox, not his whole herd of cattle, otherwise what would other strangers arriving have to eat?

Mshete and Babayane say that Lobengula asks that the Queen send him someone from herself. To this request the Queen is advised that Her Majesty may be pleased to accede. But they cannot say whether Lobengula wishes to have an Imperial officer to reside with him permanently, or only to have an officer sent out on a temporary mission, nor do Mshete or Babayane state what provision Lobengula would be prepared to make for the expenses and maintenance of such an officer. Upon this and any other matters Lobengula should write and should send letters to the High Commissioner at the Cape, who will send them direct to the Queen. The High Commissioner is the Queen's officer and she places full trust in him and Lobengula should also trust him. Those who advise Lobengula otherwise deceive him.

The Queen sends Lobengula a picture of herself to remind him of this message and that he may be assured that the Queen wishes him peace and order in his country. The Queen thanks Lobengula for his kindness which, following the example of his father, he has shown to many Englishman visiting and living in Matabeleland. This message has been interpreted to Mshete and Babayane in my presence and I have signed it in their presence and affixed the seal of the colonial office.

(Signed) KNUTSFORD

Colonial Office 26 March 1889”

From the descriptions by Mshete and Babayane Lobengula would grasp the economic and military strength of Victorian England.

Lobengula rejects the Rudd Concession

Starting in early 1889 after hearing reports in the South African press that Rhodes intended to occupy and annex Mashonaland, Lobengula repeatedly stated that he rejected the Rudd Concession because of the signatories trickery; this despite the written text having been translated and repeatedly explained to him and his trusted Indunas just before he signed it. Lobengula wrote letters and hoped that they would reach the queen, but there were no replies from her, or the Colonial office.

Further letters to Queen Victoria

Lobengula wrote a letter to Sir Sidney Shippard, Resident Commissioner of the Bechuanaland Protectorate to be forwarded to Queen Victoria:

“Matabeleland, 10 August 1889

Sir, - I wish to tell you that Mshete and Babayane have arrived with Maund. I am thankful for the Queen’s word. I have heard Her Majesty’s message. The messengers have spoken as my mouth. They have been very well treated.

The white people are troubling me very much about gold. If the Queen hears that I have given away the whole country, it is not so. I have no one in my country who knows how to write. I do not understand where the dispute is, because I have no knowledge of writing. The Portuguese say that Mashonaland is theirs, but it is not so. It is all Umziligazi’s country. I hear now that it belongs to the Portuguese. With regard to Her Majesty’s offer to send me an envoy or resident, I thank her Majesty, but I do not need an officer to be sent. I will ask for one when I am pressed for want of one.

I thank the Queen for the word which my messengers give me by mouth, that the Queen says I am not to let anyone dig for gold in my country, except to dig for me as my servants. I greet Her Majesty cordially,

(signed) Lobengula x (his mark)

Before me

Witnesses (signed) J.S. Moffat Umshete

Assistant Commissioner Babjaan

(signed) J.W. Fill Boyongwane”

Babayane in 1896

Towards the end of the Matabele Rebellion or First Umvukela and after the first Indaba Babayane made an appearance at Rhodes camp. James McDonald was present and wrote in his book Rhodes, A Life that Babayane was still an important political voice. Johan Colenbrander who had handled the envoys so well on their trip was also present at Rhodes camp. Babayane told tales around the camp fire of his London mission to Queen Victoria where he had been presented with a large gold bangle inscribed ‘Babayan, from the Queen V.R.I.’ which he still wore. He had been given other presents, as had Mshete, but both stealthily disposed of them and the European clothing they had worn in Britain as they trekked slowly from the railhead at Kimberley back to Matabeleland.

He told Rhodes and McDonald that if they had kept their European clothing they would have been accused of being disloyal to the traditions of their nation. He said he disliked parting with his new clothes in Khama’s country, but it had to be done; McDonald speculated they had probably been sold as he considered Babayane a crafty fellow.

Again only the large photograph of the queen is mentioned as a present; nothing about a neck chain. Babayane told them some of the presents were damaged after their long journey and Lobengula was not pleased, but cheered up when he heard that the Royal Life Guards were to bring the queen’s response to his letter.

He and Mshete even held back describing the wondrous sights they visited: “No, I had my reputation to think about. Had I told them of the many wonderful things I saw, all would have said, ‘He is lying, the wind has got into his head.” Neither of them told anything the others could not believe. Babayane finished his story by saying: “Does Mr Rhodes know that in these bed times I no longer possess a pipe or tobacco, nor do I have a big coat to protect me from the cold? The Queen would be unhappy if she knew.” McDonald says of course the old scamp gained his desires.

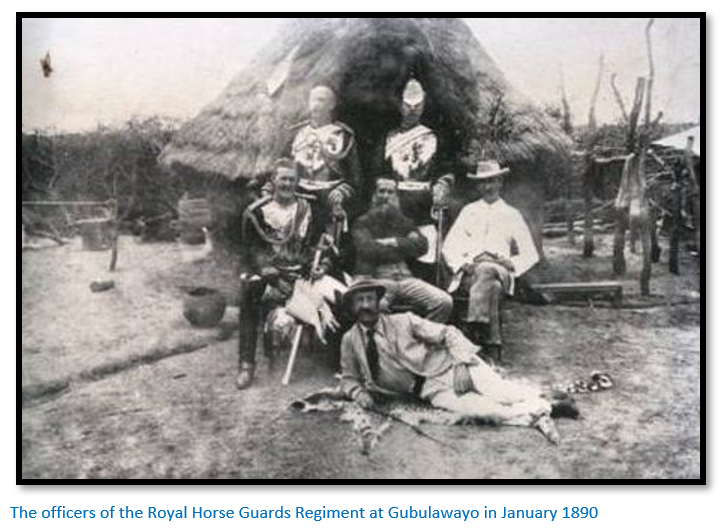

Mission from the Imperial Government

The final chapter in this sham was in November 1889, when a delegation of Royal Horse Guards comprising of Captain V. J. F. Ferguson, Surgeon-Major H. F. L. Melladew, Regimental Corporal-Major A. White and Trooper Ross brought a message from Lord Knutsford on behalf of the queen to Chief Lobengula’s kraal at Umvutcha, Gubulawayo announcing the incorporation of the BSACo by royal charter and advising Lobengula to give his confidence and support to the company and its representatives in Matabeleland.

The Times correspondent account of the journey

The mission’s coach was drawn by ten mules and painted in red and yellow with the royal “V.R” and crown in gold…clearly dressed to impress! A detailed account by Surgeon-Major Melladew is included in Mathers’ book. However there is another account in The Launceston Examiner of 23 April 1890 [kindly provided by Barry Brown] which carried an article from The Times correspondent who accompanied the Royal Horse Guard party carrying the royal letter to Lobengula that announced the incorporation of the BSACo by Royal Charter and advising Lobengula to give his confidence and support to the company and its representative in the country.

The mission left Kimberley on 16 December 1889 for its long journey across Bechuanaland, Khama’s country and Matabeleland and the article gives an account of the journey and their first interview with Lobengula.

The special coach took them via Barkley West and Vryburg and Mafeking to Palapye, the Bamangwato capital over twenty days covering 1,046 kilometres (650 miles) Detours were made from the regular route to visit those chiefs living under the British protectorate on the recommendation of Sir Sidney Shippard.

Few kraals were passed except along the Marico and Limpopo river valleys and the countryside was extremely dry. South African horse disease had killed most of the horses and mules upon which the newly established post-cart service relied and for the last 130 kilometres (80 miles) the heavily-laden coach with its party of nine passengers and drivers, their baggage, uniforms, arms, presents for Lobengula and provisions was drawn by a team of oxen.

At Palapye, Khama’s capital, reached on 6 January 1890 the mission halted for a fortnight, where they were entertained by Heany and Borrow, representatives of the Bechuanaland Exploration Company. The correspondent makes the point that no wine or liquors or even traditional beer were permitted in Khama’s country. Six months previously the entire population of Shoshong, some 20,000 people had migrated 114 kilometres (70 miles) to Palapye which was a better location for their kraals and gardens with more water. Khama’s army comprised 7,000 – 8,000 troops and 300 mounted horsemen.

On 21 January accompanied by BSACo police they journeyed the 145 kilometres (90 miles) to the settlement of the Tati Gold Mining Company which owned the embryonic Monarch, New Zealand, Blue Jacket and other mines which the Times correspondent was positive would become a great business centre.

Another 193 kilometres (120 miles) of hard trekking on poor tracks brought the mission to Gubulawayo on the 27 January thanks to the driving skills of Henry Borrow and his men who had accompanied them from Palapye. At the BSACo house they were met by Major Maxwell, the company representative and John Moffat made arrangements with Lobengula for the initial interview.

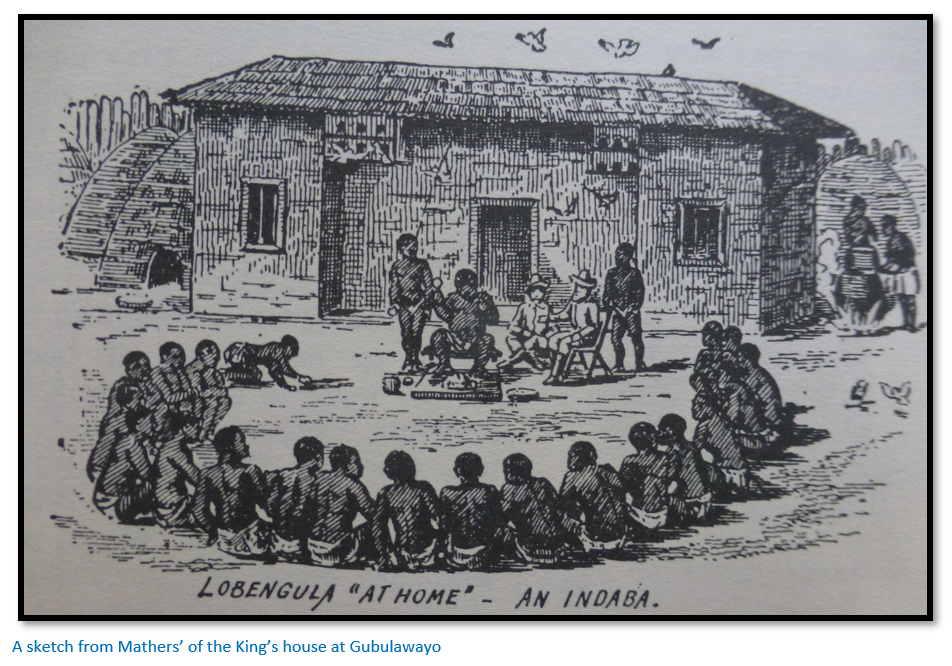

On 29 January the Royal Horse Guards mission in full ceremonial uniform met Lobengula accompanied by Moffat and Denis Doyle, the interpreter. Lobengula was suffering from gout and was not on his favourite seat, the wagon-box, but in a bath chair wrapped in a coloured blanket with his feet in bandages wearing a naval cap topped off with a large blue ostrich feather. There were 300 fine oxen in the cattle kraal nearby impatiently lowing to be let free to graze.

Captain Ferguson presented Queen Victoria’s letters to John Moffat and as he read them out Denis Doyle translated them into isiZulu for the King. The presents consisted of a cased revolver and field-glasses from the Duke of Abercorn, President of the Board of Directors of the BSACo and sporting knives and blankets. The King remarked that he had heard from Babayane of the soldiers dressed in iron and seeing the officers of the Royal Horse Guards in their uniforms now could fully believe it.

The group moved into an inner enclosure where a large joint of steamed beef and pails of beer were presented. More conversation followed and after two and half hours the mission party withdrew with Lobengula promising to reply to the queen’s letter after a week-long ceremony called the Big Dance.

Surgeon-Major Melladew wrote that the camp of Tati Gold Mining Company they met two messengers from Lobengula. Much against their inclination the two messengers were taken in the coach; on the second day their fears were realised when sudden contact with a stump sent both of them tumbling out…thereafter they chose to walk! The party travelled through the picturesque Mangwe Pass and arrived at the BSACo house, a kilometre from Umvutcha, Lobengula’s kraal.

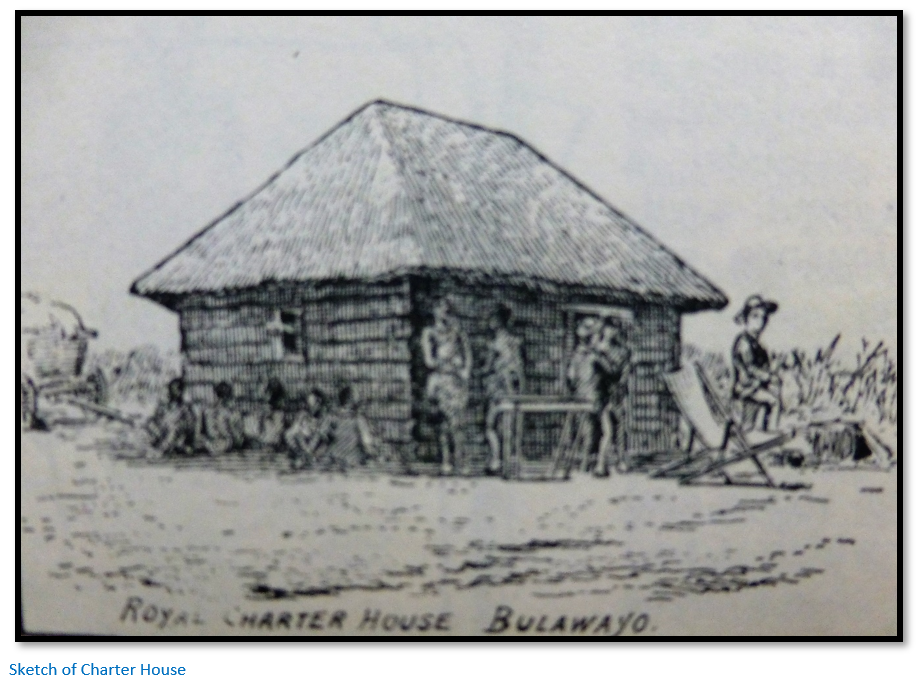

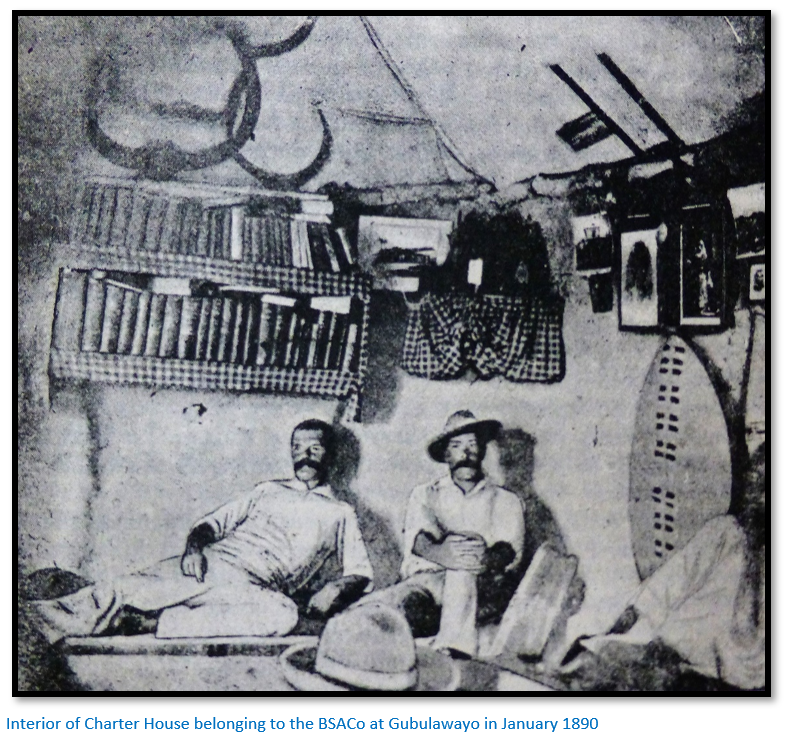

Charter House was the meeting place for those Europeans at “white man’s camp” but was also frequently visited by the amaNdebele queens, princes and princesses, young and old ladies, generals and soldiers. Nearby was the Rev. John Moffat’s, the assistant commissioner’s residence, others belonged to the Bechuanaland Exploration Company and Johan Colenbrander who ran a trading store.

Melladew tells us they were received by Lobengula wearing a monkey skin and royal navy cap with a blue ostrich feather and seated in a bath chair as he was suffering from gout. They were given boiled beef to eat and native beer which was first tasted by a native girl to show that it contained no poison. During their interview with the King men approached whilst shouting out the royal titles and stoping lower and lower until they were crouched at his side. He would not allow photographs of himself believing they would take away his spirit.

Gubulawayo was the only one of the King’s kraals to have a brick house and he travelled frequently from kraal to kraal in his wagon. Melladew and his fellow officers stayed three weeks at Gubulawayo before the King “gave us the road” that is, permission to leave the country and after the last long interview and friendly farewell at Umvutcha they attended the first meeting of the Zambesi Turf Club in which the few survivors of the recent horse sickness were entered into three flat races and two hurdles races around an oval race course.

A diversion – Lobengula’s neck chain

Roger Summers in his Rhodesia article Some Stories behind historical relics in the National Museum, Bulawayo implies that the neck chain from Queen Victoria was brought back to Lobengula by his envoys Mshete and Babayane; Maund is silent…. Lord Knutsford in his March 1889 letter mentions just a photograph of the queen, but not a neck chain.

However according to Summers the neck chain is inscribed:

From

QUEEN VICTORIA

to Lo Bengula

March 1889

The coin is a massive 1887 British Gold £5 Jubilee Head Coin supported by large links – one of which opened to allow it to be hung around the neck of the recipient. Summers says the chain is not made of gold, but of pinchbeck – a technical term for an alloy of 90% copper and 10% zinc with a gold effect look.

Summers goes on to say that Nancy Rouillard, the daughter of ‘Matabele’ Thompson told him a story recounted to her by her father when he was present at Umvutcha when Mshete and Babayane returned in August 1889.

Lobengula had looked at the red box which contained the neck chain very distrustfully – the colour red was considered unlucky by the amaNdebele and when he opened the box and saw the neck chain he threw it and the box aside. The chain links suggested slavery to him and although he said nothing at the time it took some time before he recovered his usual good temper…the colonial office had unintentionally insulted him. An account states the neck chain lay on a rubbish heap all day until retrieved by one of the queens. Summers states there are a number of stories about who had possession of the neck chain between 1889 and 1912, most likely one of the queens, although Johan Colenbrander’s name crops up after 1896, but in 1912 the neck chain was acquired by the South African Museum, although even their records of the acquisition are scant. From 1912 to 1933 the neck chain was in Cape Town until it was sent to Bulawayo for the fortieth anniversary of the Matabeleland occupation when it was loaned to the Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe in Bulawayo.

No mention of the neck chain is made by Maund in his letter of 7 August 1889 to the colonial office who says: “Your Lordship’s letter and the Queen’s picture were duly delivered. The former was read by Mr Moffat and translated to the King, who expressed himself greatly pleased with the contents and general tenor of the letter. Today the King called a meeting of all the white men in this part of the country and the letter was read out to them. The King was much struck with Her Majesty’s picture and made the minutest inquiries about the envoys regarding their visit to Windsor and ended by saying: He could well see that it was written in her face – that she was the Great Queen.”

Even Surgeon-Major Melladew in his very full account states only: “It was in a very dirty enclosure, surrounded by oxen, that he received and welcomed us, and the presents we had brought…”

The Times correspondent writes: “Captain Ferguson presented the Queen Victoria’s letters to Mr Moffat and as he read them out, Mr Doyle carefully translated them to the chief, who made a few remarks on one or two of the paragraphs. The presents consisting of a very handsome revolver and case and field glass from the Duke of Abercorn, as a director of the Company and some good sporting knives and specially selected blankets., were then presented to him, and accepted with evident pleasure.”

Ray Roberts in Rhodesiana No 26 wrote a well-researched article called ‘The Treasure and Grave of Lobengula: Yarns and Reflections’ and writes: “Consequently rumours of treasure did not die away and several circulated for many years around Johan Colenbrander, one of the first in the field after Lobengula’s disappearance, who was said to have made ‘finds’ along Lobengula’s route and at the Queen’s kraal – whether by unearthing, or by theft or by extortion from Lozigeyi [one of Lobengula’s senior queens] is not clear, but she did say that she had ‘given’ two pots full of coins to a European well-known in Matabeleland. Then there was the gilt chain and the necklace of lion claws set with gold that he [Colenbrander] returned to Rhodesia in 1911 - almost certainly Lobengula’s but their previous history is as obscure as their fate, for they then disappeared again, as mysteriously as they came.”

Whether Lobengula was given one or two neck chains is not certain – certainly the gilt chain associated with Colenbrander and referred to by Ray Roberts as disappearing after 1911 and the 1912 acquisition of the neck chain described above by the South African Museum and now in the possession of the Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe in Bulawayo seems more than a coincidence.

Acknowledgements

Barry Brown for bringing Neil Parsons’ publication to my attention and reminding me of past Rhodesiana articles

Barry Brown for sending me the nla.news-page2944132 (The Launceston Examiner Wednesday April 23, 1890) by the Times correspondent who accompanied the Royal Horse Guards.

E.P. Mathers. Zambesia; England’s Eldorado in Africa. Books of Rhodesia. Bulawayo, 1977

N. Parsons. 'Black Victorians/Black Victoriana' edited by Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina Rutgers State University, 2003

N. Parsons. Southern African royalty and delegates visit Queen Victoria in Mistress of Everything: Queen Victoria in Indigenous Worlds edited by S. Carter and M. Nugent. Manchester University Press, 2016

R.S. Roberts. The Treasure and Grave of Lobengula: Yarns and Reflections. Heritage Publication No 23 - 2004

R. Summers. Some Stories behind historical relics in the National Museum, Bulawayo. Rhodesiana Publication No 26. July 1972