Orton’s Drift over the Sebakwe River

- An interesting part of the country’s postal and transport network, Orton’s Drift has survived intact despite over a century of floods

- The telegraph Office is a rare survival from the past

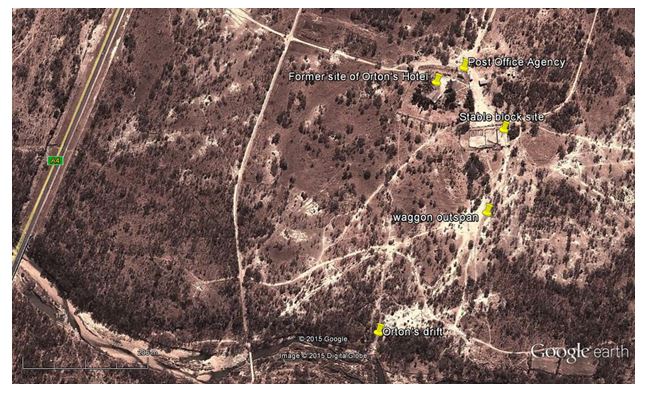

From Chivhu take the A4 south. 29.2 KM turn off the A4 into the Mavise Bus Stop and take the old strip road which runs parallel to the A4 towards the Sebakwe River, 30.5 KM turn left onto a farm track at the cross roads, 30.7 KM reach the farmhouse which is the site of the old Orton’s Hotel. The Agency Post Office still stands on the north of the property; the stables are now covered in a cattle kraal. The waggon outspan is 120 metres south of the house with Orton’s Drift which crosses the Sebakwe River on an artificially constructed stone ford which dams the Sebakwe River to its east.

GPS reference: 19⁰09′10.80″S 30⁰39′01.64″E

Below is a Rhodesia 1898 One Penny Duty stamp with an Orton’s Drift Post Office agency cancellation stamp postmark dated 4 September 1899.

GDB Williams in an early Rhodesiana article thinks the drift was opened about 1894, but as a crossing point with its hotel, it may have been used earlier. Although he does not identify Orton, there is a clear and unmistakable reference to Orton’s death by FC Selous in his book Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia; Appendix A, which lists the persons murdered in Matabeland in 1896 and Henry Sambourne Orton was last heard of at the Sebakwe River Drift. His body was not found presumably because it was dumped into the Sebakwe River. DN Beach in an article mentions the telegraph line going through Orton’s drift as well.

Orton’s Hotel was replaced on the north bank of the river by the existing house in 1953 and the stables, still in use in 1965 have been demolished, but the Post Office Agency building is still standing. Between the Hotel and the Sebakwe River is an open space which was probably an outspan, where the wagons stayed when the river was running too high to cross and presumably there was another outspan on the south side of the river. The Post Office Agency was opened in 1894 and abandoned in 1908, probably due to the opening of Enkeldoorn in 1897 and the completion of the railway from Bulawayo to Harare in 1902.

There were two roads over the Sebakwe River; the earliest was the western road which went south from Hartley Hill and Concession Hill skirting past the present-day Ngezi Recreational Park and due south to cross the Sebakwe River, before turning west for Fort Ingwenia and the Old Hunters Road and was in use before 1890. The eastern route which went on to Fort Charter crossed here at Orton’s Drift and was used by the later passenger coach from Gwelo (now Gweru) to Salisbury (now Harare) This road cut across the vast landholding of Central Estates, part of Willoughby’s Investments to Iron Mine Hill and Lalapanzi.

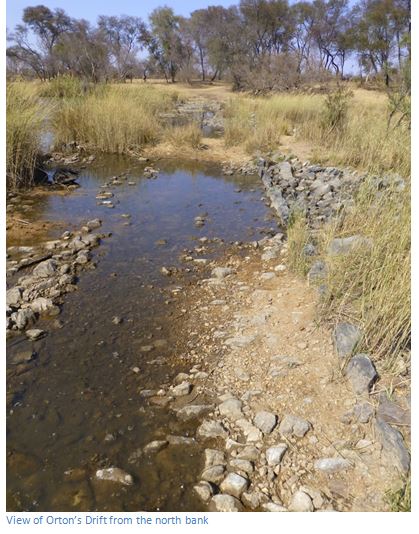

Orton’s drift was made of stones which were laid on edge from bank to bank across the Sebakwe River at normal flood height and is still negotiable by vehicle, although the low-level bridge 200 metres is much more convenient. A considerable quantity of stones was dropped into the riverbed which had the effect of damming up the river to the east, but allowing the water to flow over the Drift and downstream and it is still possible to walk from bank to bank without getting one’s feet wet!

It must have been extremely uncomfortable to ride on an ox-waggon or passenger coach across the drift as the stones are very unevenly laid and passengers probably walked across. The stones are mostly quite small with larger stones at the edge to mark the edge of the drift which has been laid in a straight-line as can be seen in the photo below. This no doubt helped navigation over the drift when the river was higher than when visited in mid-August.

The current occupier of the homestead Mr Fambi Makumbe showed me a letter from Willoughby’s Investments giving him the right to occupy the homestead and in the past Mr Makumbe has resisted a number of efforts to have the historic Orton’s Drift Post Office Agency and Telegraph office pulled down. The building originally had two rooms and a small lean-to; the larger room with a fireplace, but the dividing wall has been pulled down and some of the original windows and doors have been bricked up.

The lean-to is probably contemporary with the main building and is as wide as the original verandah with its door leading from the verandah. I assume it was the toilet / bathroom and the kitchen would have been a pole and dhaka hut in the near vicinity.

I could see no sign of where the telegraph wires entered the building, but there is damage on the rear corners where a stanchion might have once supported the wires. Over the fireplace sections of the original brown painted wood timbering forming the ceiling still remain and the interior plasterwork is remarkably intact. Parts of the original foundation slab are visible showing it was made of cement and flat stones and was built up about 10 centimetres above ground level. Multiple holes in the exterior plasterwork show where police details stationed on site have used the walls for target practice.

Until the end of 1900, the Canadian and Australian troops taking part in the Boer War would have disembarked at Beira. To prevent drawing attention to themselves in a neutral country, they arrived in separate, small groups from April to August 1900. They travelled by rail from Beira to a camp in the Pungwe swamps called `75 Mile Peg' (now Gondola), then moved to Bamboo Creek (now Vila Machado), a deadly place for malaria. From there they travelled to Umtali (now Mutare) where, on reaching Rhodesian territory, they were able to receive improved medical care and rest. A number died from malaria, their condition being worsened by malnutrition before arriving at their base and training camp at Marandellas (now Marondera)

The rail line from Salisbury to Bulawayo was only completed to Gwelo during June 1902; the section to Bulawayo was completed by December of the same year. So until then, Lord Carrington's Imperial forces consisting of 5,000 men, 10,000 horses, and 14,000 tons of military stores, guns and ammunition would disembark at Marandellas (now Marondera) and trek to Bulawayo. This journey was either on foot accompanied by ox-wagons, or in overcrowded mule coaches hired from the Zeederberg Company by the British South Africa Company, although this mode of transport was often reserved for officers only.

James H. Birch in History of the War in South Africa gives an account of the Canadians mounted troops deployment through Beira in 1900 of which this part is relevant: “Although our journey from Marandellas to Bulawayo was carried out hurriedly and under trying circumstances, it was, nevertheless, most interesting. Occasionally at night the roar of a lion could be heard; and now and then during the day a deer, leopard or jackal would dart across the trail. The first British South Africa Police post reached was Fort Charter, 60 miles from Marandellas; then Enkeldoorn, 50 miles further on Sebakwe, or Orton's Drift, 114 miles from Marandellas, was reached in due course. The Sebakwe River here divides Mashonaland from Matabeleland. We found the telegraph line here disconnected; the reason stated being that the civilian operator was pro Boer.

After Sebakwe we got to Iron Mines. Then came Gwelo, another interesting place and the largest we had been in since leaving Beira. There were quite a number of white people here and we were well received. There was a hotel, bank, a large post office building and other places of importance. Gwelo is a gold district and a fever district too, over half of the population at the time being down with it. So far, very little rain had fallen since our landing at Beira, or indeed since our arrival at Cape Town, nor did we see much rain for some months to come. It was the winter season in Rhodesia, all vegetation being dried up. On this account, the country presented a very desolate appearance. The roads at times were extremely bad, and the drifts in some places were well-nigh impassable and extremely dangerous for men and horses. Another unpleasant feature, and one with which we had to contend in nearly all our treks, was the dust, so thick at times as almost to choke men and horses.”

With The Bushmen, The Trek across Rhodesia was written by Captain the Rev. James Green, Chaplain with the troops and was written at the Bulawayo Showgrounds on June 2nd 1900 and was published in the Sydney Morning Herald of 13th July, 1900.

On Friday, May II, 50 officers, non-commissioned officers and men, under the command of Captain Machattie, of C squadron, left Marandellas Camp for Bulawayo. Captain Dibbs, New South Wales special service officer, and Lieutenant Darrien Smith, Imperial special service officer, who were ordered to Bulawayo for camp duties, were attached, as was also Captain Green, Chaplain. There were a hundred horses with the detachment and six ox wagons, laden with stores and ammunition. When the detachment was drawn up for inspection it presented a very fine appearance, as we had an unusually good lot of horses. The general being detained on urgent business delegated his duties to Colonel Beal, who inspected the troops and expressed his satisfaction at the appearance of men and horses. Having left late in the afternoon, we travelled six miles only the first night, then outspanned and off-saddled. For many of us that night was the first experience of what is now very common to us; sleeping out on the open veldt with only our blankets and waterproof sheets around us and the Southern Cross and the Great Bear keeping watch above.

Reveille sounded at 3 am as we were to trek at 4 am. Now began the routine of the march. "For 19 days we have had as near as possible inspanned at 4 am and outspanned, at day-break. Then breakfast had to be cooked, horses fed and groomed, arms to be cleaned. At 2.30 pm the men were paraded, told off to bring horses in again from the veldt where they grazed, water them, and get ready to trek once more at 4 pm. The evening trek finished at any hour between 8 pm. and 11 pm., according to the location of the camps, when once more after supper we lay beneath the stars until roused by the unwelcome sound of the bugle at 3 am. During the last week of our trek a better arrangement was arrived at; we sent a guard of troopers with the wagons, slept an hour later, and overtook the wagons bringing our swags on the spare horses. This routine allows oxen and horses to graze in the warmth of the day, the only time when it is quite safe to permit them to do so. We managed to travel from 17 to 20 miles a day. We could not, of course, go faster than the wagons. One of the dreariest experiences was when at night or early morning, especially when there was no moon or day had not yet dawned, the detachment had to wait in the cold near some spruit for the wagons. As soon as the conductor points out the camp, the fires are lit, forage given out, billies boiled, and biscuit and bully beef, varied with Maconochie's field ration, partaken of.

A good deal of money has been spent along the road by the troopers for "extras," but it should be understood that the army rations are of excellent quality. Of course there is a natural craving for variety and in many instances men who are "off-colour" need other things. We had with us some supplementary stores given by a generous Government when we embarked on the Maplemore. We shared these with the troops of the other colonies on board the transport, then we brought what was left on and we have been grateful for them many a time on the veldt. For the first few days it was one succession of trekking from spruit to spruit. It was very picturesque, the long column moving along the kopjes in the moonlight, or in the twilight of early morning, when the horizon was defined by a band of soft blue light, surmounted by the fast growing pink colour which is the sure herald of day.

Mashonaland is a beautiful country, more rugged than Matabeleland, which is for the most part flat, treeless country. Picture the bush of New South Wales without gum trees, but sparsely dotted with the thorny mimosa bushes, and with grass growing frequently to the height of the horse you ride. On either side you see hills covered by great rocks poised at all sorts of impossible angles and forming numerous caverns - these are the kopjes. We began the long trek in great spirits and there was much to cheer us on our march-the bright wild flowers, the beautiful landscape, and the magnificent butterflies. By the roadside we often saw white waratahs, which reminded us of our own more beautiful ones in New South Wales, and then there were crocuses, tulips, and convolvuli, as well as very fine feathery grass all around. Every spruit bore on its bosom beautiful white or blue water lilies; and the little spruits themselves, with banks studded with rocks of white quartz were pictures whose beauty marks them permanently upon the memory.

But our troubles now began. The very first time we camped we lost one horse to the dreaded horse sickness, "dikkop," and this continued day after day until the ghastly list of I6 horses dead out of 100 was reached. It is not easy to persuade an Australian that any country is beautiful where horses will not live. There seems to be little difficulty with oxen, though they are expensive, owing to the ravages of the rinderpest among them some years ago. Now however, when the rinderpest does attack a herd only 20 per cent are lost, as inoculation has proved very successful. The docility and training of the oxen are admirable. For instance, when they are called they come back in their ranks just as they are in spanned in pairs; and when they lie down to rest, when free for a while, they lie down alongside their yokes ready to inspan quickly. The teams are made up of uniform colour, and are composed of I6 oxen. When oxen have to go a good way to graze the drivers sprinkle salt on the road home, and when they wish to inspan they call out, “Sante, Sante," and soon you can see the oxen coming along in their ranks, their noses on the ground ready for the salt. The English, Dutch, and natives drive oxen in language made up of Dutch and native words they call it "talking ox." It is the custom to name the worst ox of the team "Englishman" and this obtained in our teams. The mail coaches which frequently passed us are drawn by 10 mules. Often wagons would pass by drawn entirely by donkeys. This is the slowest way to trek and rather risky as the lions can smell a donkey from afar. Scotch carts with four oxen in spanned, take good loads at a fair speed, but if you want to trek quickly you must have a Cape cart, i.e. a heavy and large sulky, with four or six mules in spanned. We passed a good number of cyclists, also on the trek. Their only difficulty is the spruits.

On Tuesday, May 15, at daybreak, we reached Charter, formerly called Fort Charter. We found Lieutenant Fraser here, ill of fever. Sister Anderson, of the Victorian nursing staff, had come from Salisbury to nurse him. Mr. Fraser's men had to carry him back two miles to Charter, he was so ill. I am sorry to say that Sister Anderson has never been without patients at Charter since. Every detachment keeps up the number of two or three and it is this way at every place we reach. We take a few convalescents from the hospitals at Enkeldoorn or Gwelo as we pass, but we always have others to leave behind for those whom we take on to re-join their own squadrons. I am pleased to say that at this date Lieutenant Fraser is quite well and per-forming his duties in this camp. On Wednesday we crossed the River Umniati at a very deep drift. On Thursday, May 17, we outspanned late (at 8.30 am) at the scene of the massacre of 14 white women and 21 white men settlers who were murdered in the early days by natives. On Friday we reached the township of Enkeldoorn (single-thorn tree), so called because of one large thorny mimosa growing near the first farm built. This township is entirely inhabited by Dutch, and their loyalty is such that they celebrate every victory, whether of Boers or British, in the same way, by the whole of the settlers getting drunk on "dop." Just before we reached the town we had much delay by one of our ox wagons breaking down, and unfortunately the new one we obtained also broke down when we were 25 miles out from Enkeldoorn. On Saturday, May 19, we arrived at Orton's Drift, where we crossed the Sebakwe River. Here we heard of the relief of Mafeking and we hoped that our comrades ahead were in it. For some miles our road was now flanked with a continuous wall of fire, a slow-burning veldt fire.

On Sunday May 20, we crossed the Blinkwater, which divides Mashonaland from Matabeleland. We had church parade at 10 am upon the veldt. On Monday May 21, we reached Iron Mine Hill at 7am. Near this place there are thousands of natives. The chief of the tribe of Kilenza, whose name is Chilimongie lives in this district, and is a very rich man. He has 56 wives and 118 children. At noon of the 21st Quartermaster-sergeant John N. Walton, who had been ill more or less ever since leaving Marandellas became very much worse. He had been relieved of his duties, which were being performed by Sergeant Holmes, and was lying on the wagons during the trek. He became unconscious when being assisted off one of the wagons. Captain Machattie decided that it would be necessary to leave Walton at Iron Mine Hill and I stayed with him, and had a supply of invalid's food and some medicine with which to nurse him. Mrs Svenson, the proprietress of the store was very kind, and we occupied a native hut near the store. I kept my horse with me, in order to follow the detachment. Unfortunately I was disappointed in my hope of nursing poor Walton well, for he gradually sank and never regained consciousness. He died at 10 am on May 22 of congestion of the brain, following malarial fever and bronchitis. I stopped a waggon load of "boys " who were going to work on the road at 4am. The foreman allowed me three boys to dig a grave. They worked till 2:30 pm as the ground was rocky. We dug the grave in a line with the three other graves, in which were buried Mrs Swenson’s husband and two children, who died of fever at Iron Mine Hill. The only two white settlers, who were very kind, tried their best to make a coffin of packing case wood, but found it impossible with the short wood they had. We were reluctant to bury him in his blankets, though that is the custom on the veldt. After searching we found an old sheet of corrugated iron; this we placed on the bottom of the grave. We built a wall of stones around this and made a strong lid to fit on top of it. At 4 pm on the same day we buried him. We put a wooden cross at the head of the grave, with name and suitable inscription painted on it.

I overtook the detachment, which was 30 miles ahead at midnight, and the sad news I brought cast a gloom over the troops for Quartermaster-Sergeant Walton was deservedly respected by all. We arrived at Gwelo, the third largest town of Rhodesia, at daybreak of May 23. As at Enkeldoorn, we found here that the streets, which are well laid out, are planted with Australian gum trees and a few pepper trees. We had to stay here the whole day waiting for ox wagons carrying oats for us. We were thus able to participate in the celebrations on the relief of Mafeking. The next day was the 24th (Queen's Birthday). At Gwelo there were sports and a race meeting arranged, and, by a curious coincidence, 30 teams of oxen arrived early in the morning. We had no blank cartridge with which to salute, but we gave three cheers for the Queen at our parade and drank her Majesty's health at dinner-most of us in Billy tea! We passed Majojo Mountain and went through Somabula Forest during the day. Somabula forest is famous for lions. Some members of A Squadron saw lions here, one trooper had three shots at one, which got away, but we had no such luck. One of the squadrons boasts of having killed a jackal on the trek .We had no further acquaintance with these brutes than hearing their continual barking round our camp at night. There was not a day, however, when we did not get birds of some sort, pigeons, pheasants, or bastards, as a variety in our bill of fare.

On Saturday, May 26, we crossed the Shangani River, and at 7 am we camped in the beautiful Matopos Hills. At the night camp we had hardly got stowed away in our blankets when a thunderstorm broke over us. Of course, most of us had forgotten to turn our boots and helmets upside down, and put our leggings under our pillows, but on the whole we got off very well. We abandoned our early morning trek in order to dry our clothes and had to trek later when we should have been holding church parade. During this day (Sunday, May 27) we crossed the battlefield of Shangani. The surrounding kopjes are still witnesses to the defeat sustained by the Matabele, as human bones are seen strewn upon the ground. About half a mile from the battlefield we passed a large monument erected to the memory of 42 men, women, and children murdered by natives during the rebellion. On Monday and Tuesday May 28 and 29, we passed through several clouds of locusts, which were eating up the young grass and rising crops. Without further incident we reached the outskirts of Bulawayo on Wednesday at day-break. Here we halted for breakfast, and after the usual duties had been performed the whole column entered the town. Our entry created considerable interest. We were conducted to our present camp in the Agricultural Grounds, where we have the luxury of sleeping under canvas and being reunited to about 300 of our comrades of the Bush Contingent. We have travelled 290 miles, the distance between Marandellas to Bulawayo. We were all sorry to hear that 80 of our men, including our Colonel, who are now at Mafeking, were too late to participate in the relief of that town.

Acknowledgements

F.C. Selous. Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia. Books of Rhodesia

D.N. Beach. Afrikaner and Shona settlement in the Enkeldoorn area, 1890-1900

G.D.B. Williams. Where was it? No. 1 Orton’s Drift. Rhodesiana No. 13 December 1965