Nyunteya Cave & Grain Bins

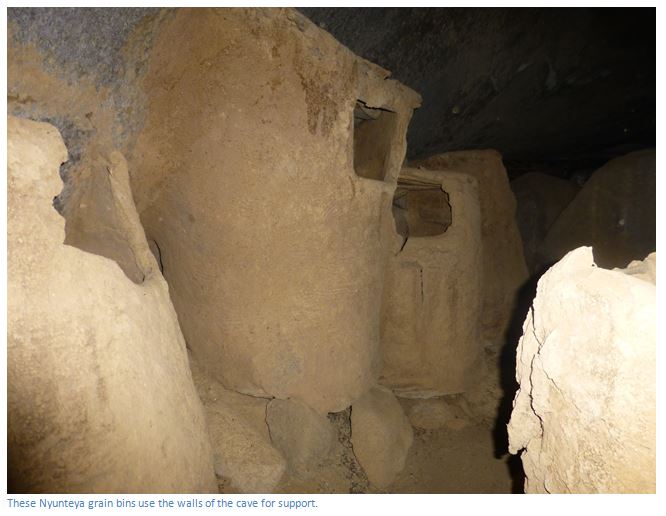

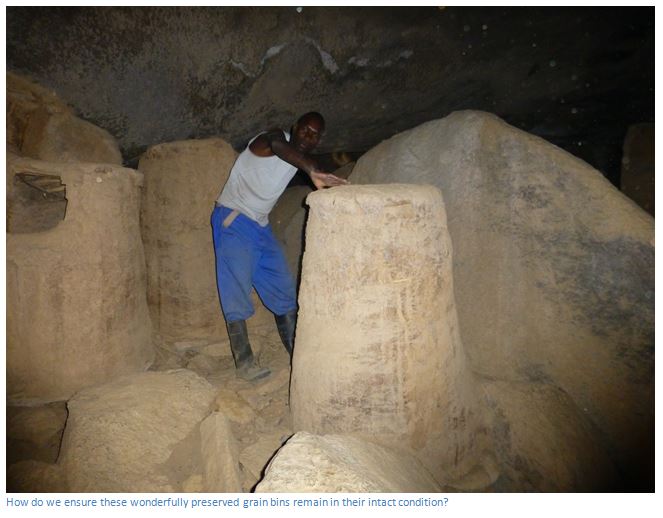

Nyunteya Cave: this well-hidden cave, about 300 metres from the road, contains about 13 grain bins, most of which are intact.

Caves and shelters hidden away in the rocks have always formed part of amaNdebele culture as secret places known only to the local communities and as places to make medicine, or for rainmaking shrines and burial places. Their adaption as places to store grain surpluses during the AmaNdebele uprising or First Umvukela of 1896 showed a very flexible approach to the exigencies of the period. Col. Plumer’s MRF went to considerable lengths to seize and destroy grain supplies to starve the amaNdebele out of the Matobo and using grain bins in caves showed a clever and practical cultural adaption to the traditional forms of grain storage in the area.

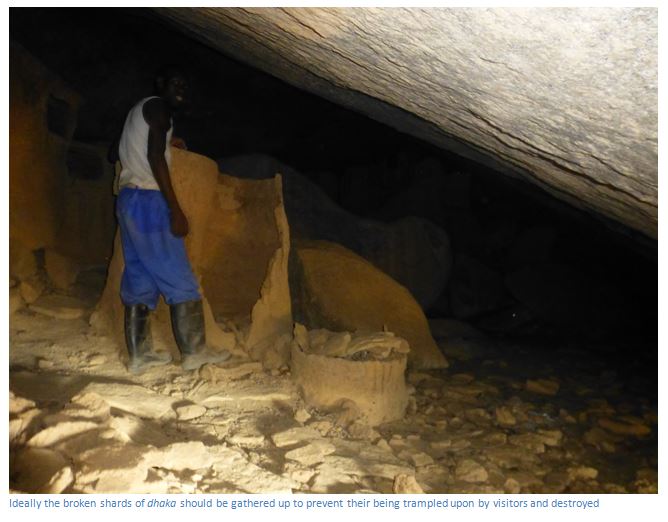

Take care going into any cave not to stand on the clay dhaka remains of broken grain bins, or cause more destruction; visitors can help to preserve the visible remains of amaNdebele culture.

And take care not to make much noise which disturbs the bats, which also live in the cave.

Nyunteya Cave and grain bins are about 70 kilometres southeast of Bulawayo and just a kilometre from the AmaNdebele uprising or First Umvukela Indaba Site (Rhodes Indaba site) From Bulawayo take the A6 towards Gwanda, but turn right at the turnoff just before Mawabeni (57.5 KM peg) Drive the untarred road 10 KM to Esibomvu, turn left down a road 100 metres after Esibomvu Clinic signposted Diana’s Pool 9 KM / Rhodes Indaba site 7 KM. Cross the Nsezi stream following the road, ignore the first road to the left, signposted Tshalimbe Primary School, my GPS directed me down this road to a dead-end. Continue on straight to where the road forks right to the signposted Indaba site. Take this road, turning a sharp left after 1.5 KM and then after another 0.5 KM passing the fenced indaba site on the left side of the road. Continue another 1.0 KM and park opposite a kraal on the left side. To reach the caves follow a path opposite the kraal on the right-hand side of the road to a large outcrop of granite boulders just 300 metres from the road.

The road is suitable for ordinary vehicles, as long as they have good ground clearance.

GPS reference: 20°26'55.61"S 28°51'20.34"E

Grain-bins are relatively common in the Matobo Hills, a World Heritage Site in south western Zimbabwe, and also the Ntaba-zika-Mambo Hills. Many archaeologists believe that much of the pottery and artefacts found on cave floors and most of the clay grain bins are remnants of the 1896 period when the amaNdebele were besieged in the Matobo hills by Col. Plumer’s Matabeleland Relief Force. (MRF)

The association of man with the Matobo Hills goes back a very long way indeed, perhaps hundreds of thousands of years. When the first hunter-gatherers arrived in the Matobo hills they found not only permanent water and plenty of game, but ready-made shelters in the many caves and shelters that are dotted around in the kopjes. Although dating that period of time will always be risky; the stone tools excavated at Bambata Cave have been estimated at 10,000 - 20,000 years old, while crude scrapers and knife-like tools from the archaeological layers may be as old as 50,000 years.

The evolution of the Stone Age hunters who shaped these artefacts can be traced through the range of tools found in successive layers of the cave floors. Crude hunting spears gave way to the bow and arrow with a longer killing range and whose efficacy could be augmented by the use of poison. Other remnants of their occupation include thousands of sharp-edged stone scrapers and small, flat beads of ostrich eggshell.

The name given to the latest of these stone-age periods dating back at least 6,000 years in south and east Africa was the Wilton culture and it is characterised by more sophisticated tools. The Wilton people in addition to using stone also used bones and produced items such as awls, ornaments and composite arrows. They also made wooden tools to uproot edible roots, which was a staple in their diet.

All of the rock art produced by San hunter-gatherers on the caves and shelters in the Matobo Hills such as Bambata, Inanke, and Nswatugi is linked to this era along with the paintings that are to be found in almost every rock shelter of any size. Often erroneously called ”Bushmen” the San are peaceful nomads who lived off wild fruits and game and moved around in small groups and still just manage to survive in the Kalahari region of Botswana and Namibia.

Approximately 2,000 years ago the first Iron Age people, the Bantu, arrived in the area probably from the North. They were pastoralists, and brought with them sheep and goats and later cattle; but also they had learned the skills of making iron weapons in furnaces and could manufacture pottery. The San were gradually forced out as the Bantu took over their hunting areas and cleared land for growing millet and sorghum.

The grain bins are about 1.2 metres high and 60 cms across with quite thin clay mud dhaka walls about 5 cms thick. They are entirely enclosed except for a square entrance 25 x 25 cms near the roof of the grain bin. Presumably millet, or sorghum, or maize was scooped from a shallow basket when filling the grain bin. They often have a solid foundation of stones and the top of the grain bin is reinforced with layers of small sticks.

We are extremely fortunate that there are still intact grain-bins in the Matobo Hills, as they are easily broken and in 1896 after the grain had been removed, were frequently broken in by Col. Plumer’s forces to deny the amaNdebele the ability to store future grain supplies. As archaeological remnants they have been little studied in comparison to iron-age furnace sites, however they were extremely important to the local people for storing their food after the harvests and preserving food from rats and the rain and, as such, form an important part of amaNdebele culture which survives. That many were hidden away out of sight in caves shows an adaption to their grain storage methods by the amaNdebele to the reality of warfare in 1896.

This strategy was partly successful, but as Frank Sykes says on page 227 the participants at the first Indaba at the end of the AmaNdebele uprising or First Umvukela of 1896 noticed that the Indunas such as Sikombo, Somabulana, Umlugulu, Dhliso, Nyanda and Bidi “were for the most part thin and bore signs of hard times.” At its conclusion, Frank Sykes quotes Rhodes: “Alright, tell them it is over. I shall be here for some days yet, and they may come and see me about anything they wish. Tell them to come down with their wives in the valleys and sow, they have not much time.” [i.e. come down from safety of the Matobo Hills and prepare the fields for the next rainy season]