Home >

Matabeleland South >

Fort Umlugulu (previously Fort Nsezi, or Sugar-bush Camp) and the Cemetery

Fort Umlugulu (previously Fort Nsezi, or Sugar-bush Camp) and the Cemetery

National Monument No.:

71

Why Visit?:

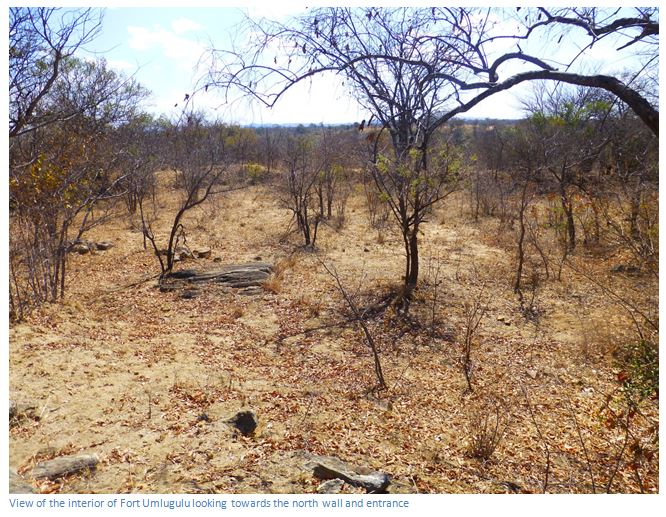

Historic fort used as a base by Rhodes during the Matabele uprising / First Umvukela and the first Indaba site. Originally known as Sugarbush camp, then Nsezi Fort and finally Fort Umlugulu. One of the best preserved in Zimbabwe because the ditches were carved out of the rock and because of its isolated position.

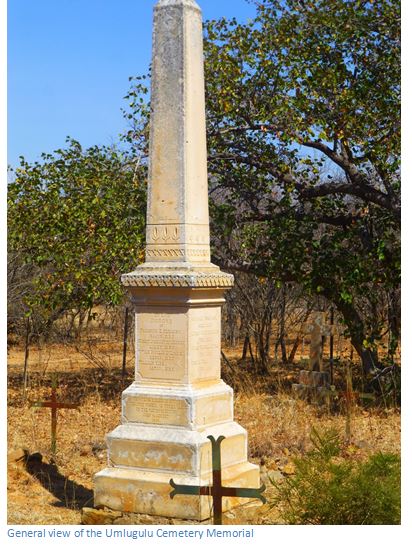

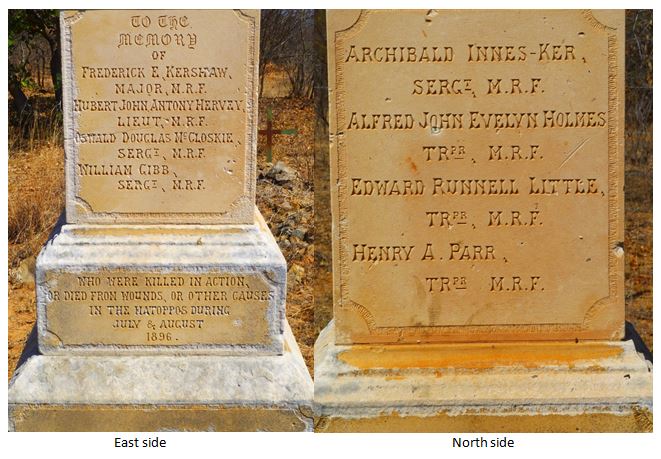

A cemetery nearby with a red sandstone monument in memory of the men who were killed in skirmishes in the nearby Matobo Hills.

Lt-Col. Robert Baden-Powell of the 13th Hussars arrived in Bulawayo on 2 June 1896, and spent the next three months in Bulawayo and the Matopos Hills, as Chief of Staff to the Matabeleland Relief Force. Many believe that the three months that Baden-Powell’s spent in the Matobo played a significant part in the evolution of the Boy Scout movement which he founded in 1908, twelve years later.

In 1893 the AmaNdebele military campaign at the battles of Shangani and Bembezi was not successful because they attacked fixed positions and came across the deadly force of the Maxim gun. They learnt from their experience and in 1896 by retreated into the Matobo Hills and so denied the Imperial forces the use of their horses and artillery amongst the rocky ravines and learnt to surround and snipe at any column that penetrated the narrow valleys. The military strategy became to starve them out as they could not be driven out.

How to get here:

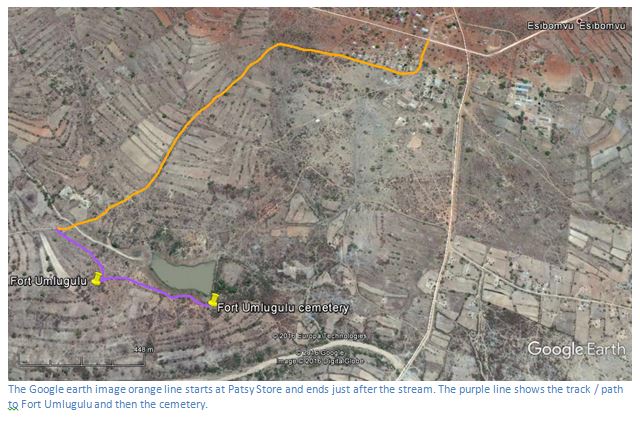

From Bulawayo take the A6 towards Gwanda, but turn right at the turnoff just before Mawabeni ( 57.5 KM peg) Drive the untarred road 10 KM to Esibomvu. At Esibomvu there is a cross roads about 100 metres after Esibomvu Clinic. For Dian’s Pool, turn left down the road signposted “Diana’s Pool 9 KM / Rhodes Indaba site 7 KM”. For Fort Umlugulu continue straight on (i.e. ignore the Diana’s Pool Rd) another 180 metres and turn left at Patsy Store (opposite Hanyana Store on the other side of the road) and continue south towards the Matobo hills. At 400 metres turn right and follow the track west past houses and a modern cemetery on the left. At 950 metres follow the dogleg left and follow the track, at 2.1 KM cross the stream and park on the left immediately afterwards. Up to this point the road is suitable for ordinary vehicles, as long as they have good ground clearance.

In a suitable vehicle, you can drive a further 250m along a poor track in a south easterly direction to the highest point of the ridge facing the Matobo hills towards the large Acacia galpinii which are located near the fort. If you have left your vehicle at the stream crossing, then walk along the same directions. In the wet season the undergrowth makes this difficult to locate.

For the cemetery follow the path that runs along the stream going east and then the edge of the dam to the cemetery which is just south of the earth dam wall. If you are at the Fort, then follow the paths from there in an easterly direction, on top of the ridge and in the direction of the dam wall.

GPS reference for the cemetery: 20⁰24′40.59″S 28⁰53′07.94″E

GPS reference for Fort Umlugulu: 20⁰24′38.49″S 28⁰52′52.78″E

AmaNdebele tactics

There is every reason to believe that the Matabele uprising or First Umvukela was well coordinated, although the murder of the first African policeman near Umgorshwini in the Esigodini area on Friday 20th March 1896 was premature and three days elapsed before the murders of the first Europeans took place. This was at Edkins store near Filabusi when Native Commissioner Bentley and six other Europeans and three of their servants were all killed; only Joe O’Connor escaped alive. [The website www.zimfieldguide.com has the narrative of the early days of the Matabele uprising or First Umvukela and events are covered in detail the two articles on Selous House (near Esigodini) and the Filabusi Rebellion Memorial.]

The amaNdebele military plan was simple; as soon as it was full moon they would arm themselves and assemble along the outskirts of Bulawayo. They would charge into the town and slaughter all the white inhabitants and their servants. The town itself would not be burnt down because it would become the royal seat of a reincarnated Lobengula. Soon afterwards the Regiments would move out over the surrounding countryside killing all white settlors and their servants on their isolated farms and mines.

As Selous writes so evocatively in Sunshine and Storm: “From the Umzingwani, the flame of rebellion spread through the Filibusi (Filabusi) and Insiza districts, to the Tchangani (Shangani) and Inyati, and thence to the mining camps in the neighbourhood of the Gwelo and Ingwenia rivers, and indeed throughout the country wherever white men, women, and children could be taken by surprise and murdered either singly, or in small parties ; and so quickly was this cruel work accomplished, that although it was only on 23rd March that the first Europeans were murdered, there is reason to believe that by the evening of the 30th not a white man was left alive in the outlying districts of Matabeleland. Between these dates many people escaped, or were brought into Bulawayo by relief parties, but a large number were cruelly and treacherously murdered.”

Albert Henry George Grey, the fourth Earl Grey was a Director of the BSA Company when he arrived in the country within three weeks of the outbreak of the Matabele uprising or First Umvukela to succeed AHF Duncan as Administrator. As D.N. Beach says in the foreword to the ’96 Rebellions, Greys’ analysis of the causes of the uprising were flawed by his loyalty to Rhodes and the BSA Company and forced him into conflict with his own sense of honesty. There is a wide difference between what he says in the ’96 Rebellions reports and what is revealed in his private correspondence, but this article is not about the underlying reasons behind the uprising.

Grey divides the Matabele Uprising into four time periods which appears a useful subdivision:

(1) From the outbreak of the rebellion around the 20th March to the end of Macfarlane’s patrol on the 25th April. Once the Europeans had organised themselves in laagers; patrols were sent out and skirmishes took place around Bulawayo; the major engagement occurring at Umgusa River. None of them were particularly decisive and the position by 25th April was that the Europeans held the laagers and forts only at Bulawayo, Gwelo, Belingwe and Mangwe and the whole countryside outside their immediate vicinity lay in the possession of the amaNdatabele. As the best of the authors on the campaign, Frank W. Sykes who wrote With Plumer in Matabeleland writes: “At the time the MRF arrived at Khami, the AmaNdebele were still in far too dangerous proximity to the town to allow of any feeling of security. Some of them, more audacious than others, would occasionally appear on the summits of ridges not three miles distant, and would form capital targets for seven-pounder practice til, once the range found, the merry shrapnel would make them suddenly bear in mind the urgency of an appointment a few miles further from Bulawayo.”

(2) From 25th April to the storming of the Mambo Hills, or Thabas a Mambo by Col. Plumer’s column on 5th July. Two battles changed the amaNdebele tactics. The first was at Umguza River on the 25th March when Macfarlane and large patrol of around 315 men met the amaNdebele in fairly open country and in small parties. The amaNdebele came under a concentrated and steady fire from the rifles, the Maxim gun and the Hotchkiss firing one-pound shells, and made two determined rushes, but were beaten back. Their reinforcements were kept at a distance by the Maxim and Hotchkiss. Casualties among the Ndebele were high, but the patrol also had five killed and Selous had a very close escape.

(3) From 5th July to the first Indaba on 21st August. More significant battles took place at Umguza River and at the Mambo Hills, or Thabas a Mambo, ninety kilometres north east of Bulawayo. Although none of these actions were decisive for the amaNdebele the first arrivals of the Imperial forces reinforcements meant that the rebellion shifted strategically from an offensive to a defensive situation. Matisa and Godhlo’s men had moved to the Mambo hills in Inyati district, while Mtini, Umlugulu, Sikombo and Banyaan / Dhliso’s men moved to the more easily defensible and relative safety of the Matobo Hills south of Bulawayo.

The Matobo are a rugged mountainous and thickly wooded area about eighty kilometres long and forty kilometres deep, situated south of Bulawayo where there was plenty of water and grain could be hidden in grain bins deep within caves which were hard to find.

The rocky kopjes were ideal for sniping from and many of the African Police had deserted with their Winchester rifles and were good shots. This was very different situation from 1893 when the warriors believed the harder they gripped their rifles and the higher they set their sights the faster the bullet went. The 1893 War had also taught them the futility of attacking fixed positions such as the laagers at Shangani and Bembezi and they had felt the deadly killing power of the Maxim guns. In addition, they soon realised that horses were a liability in the rocky jumble of the Matobo, another advantage which could be denied the European soldiers and local volunteers.

Below is a timeline of the events in this third period, which include the building of Fort Umlugulu:

13th July - Col H Plumer, who is commanding the Matabeland Relief Force (MRF) sets up camp with 1,300 men at Fort Usher No. 1, about seven miles north of the actual Matobo hills. He is joined by Lt Col R S Baden-Powell of the 13th Hussars who is to act as his Chief Staff Officer.

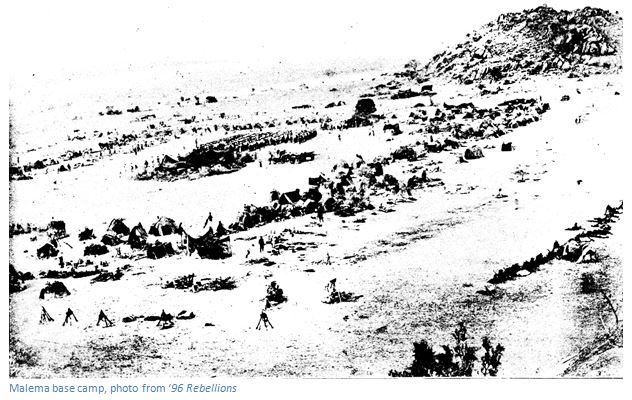

17th July - Maj Gen Sir F Carrington arrives to take overall command. The base camp is moved south to Fort Usher No. 1 (also known as Malema Base Camp), at the foot of the hills, close to the headwaters of the Maleme River.

19th July - A reconnaissance party of 35 men is harried by rebels in the upper Mtshelele valley, close to where the MOTH shrine now stands. There are no casualties, but the patrol is forced to retreat.

20th July - After a night march, 800 men of the MRF, led by Carrington and accompanied by Rhodes, attack Induna Babayan’s men at dawn after a night march at Nkantola, about 16 kilometres from the base camp. The fight begins with an artillery barrage, the kraal is burnt and the amaNdebele fight a running battle, killing 3 of Major Robertson’s Cape contingent and Sgt F.C. Worringham and retreating into the caves which Sykes describes as a game of hide-and-seek. This encounter cannot be counted as a success for the MRF.

At the same time 170 MRF with 300 local “friendlies” led by Capt. D. Tyrie-Laing is moving from Figtree in the west, to outflank the Nkantola rebels and join forces. They laager up for the night in a narrow gorge at the foot of Mount Inugu, described as “a nasty place” and the column is attacked at dawn by the forces of Induna M’biza, Inkonkebella Holi and Dhliso from two sides, by about 1,500 amaNdebele and is fortunate to barely escape complete defeat. Their attackers rushed from the heights getting within a few paces of the laager and were only beaten back by the two machine guns, Maxim and Nordenfeldt, and the seven pounder using case shot. This was to be the bloodiest fights of the entire rebellion - even today the battle site is known as Laing’s Graveyard. Cpl J. Hall of the BFF and Tprs W.H. Bush and P. Bennett of the MMP are killed instantly and Tpr O.C. Morgan dies later of his wounds and 11 horses are killed. Finding it impossible to advance closer to Nkantola, the column retired.

21st July – Maj Gen Carrington decides on a military policy of establishing a series of small forts to close the major exits from the Matopos Hills to keep the AmaNdebele in a state of siege and defeat them by cutting off their food supplies.

22nd July - Fort Usher No. 2 is established, although Baden-Powell soon selects a better site at Fort Usher No.3.

25th July - A force of 250 mounted men with 200 of Colenbrander’s Cape Corps led by Capt. Nicholson is sent by Col. Plumer back to Mount Inugu. However, as Sykes writes: “scarcely had they entered than they were exposed to a raking cross-fire from an invisible for. So well directed was it that within a few minutes four of our men were shot down.” Tprs Cheves, Bern (both buried at Fort Umlugulu) and Porter died of their injuries; Colenbrander’s Corps lost 2 killed and 4 wounded and Capt. Nicholson soon ordered a retirement. When questioned later, the amaNdebele say only 2 of their own were killed.

30th July - Having not been very successful against the amaNdebele in the western Matopos, Maj-Gen Carrington decides to probe their eastern flank, which is still untested. The transport wagons begin a 50 kilometre march via Dawson’s store to Sikombo Mguni’s stronghold by Tshingengoma, close to today’s Diana’s Pool. They establish their base at Sugar Bush Camp, later called Fort Umlugulu.

31st July - Plumer's force of 800 men then moves by night marches east along the edge of the Matopos and have a minor action at Mtshabezi. Major Kershaw with C squadron scales the heights above the valley and drives the amaNdebele into a retreat with artillery support. Somabulana and Nyanda’s strongholds are found deserted and a large quantity of grain is either seized or destroyed.

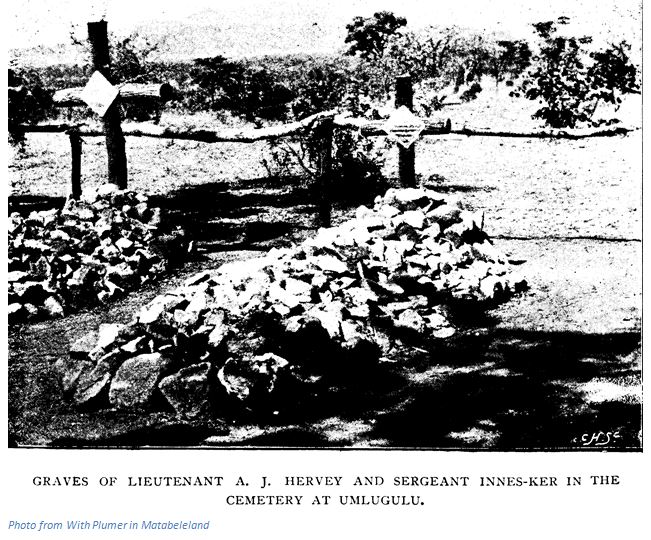

5th Aug - an advance guard of 138 dismounted men and the artillery under Capt. Beresford had moved up the pass leading to Sikombo’s stronghold. They are attacked by 3,000 amaNdebele, whom they manage to hold off for two hours, with Capt. Llewellyn sweeping off the attackers at point-blank range with a Maxim, Tpr Evelyn Holmes runs to his assistance and is mortally wounded. Sgt-Major A. Ainslie is killed and then Lieut H. Hervey waving the Johannesburg detachment on to reinforce the artillery is also mortally wounded. The main body climb Sikombo’s Hill and come under heavy attack, Major F. Kershaw and Sgt-Major McCloskie are killed in the ascent; Sgt A. Innes-Kerr is killed shortly after. The troops gain the summit and begin a pursuit as the amaNdebele withdraw into the Matobo when Sgt W. Gibbs is killed. This was to prove the severest engagement of the campaign. Col. Plumer withdraws to the jeers and mocking calls of the amaNdebele after suffering the heaviest casualties of the campaign with 7 MRF men killed, including Major Kershaw, one of Plumer’s right-hand men and 13 wounded. [For details of the battle of Sikombo’s stronghold, or Tshingengoma battle see the article on www.zimfieldguide.com]

This was the most serious and important single military engagement fought throughout the Matabeleland campaign and did not turn out well for the MRF. The biggest mistake was sending the artillery under Capt. Beresford forward unsupported; they were then surprised by the AmaNdebele who had remained carefully concealed in a gully and nearly took the guns when Lieutenant Hervey was mortally wounded. At 11am Major Kershaw stormed the range of hills to the left, and while gallantly leading his men was shot dead. Robertson attacked at 12am and the amaNdebele began to withdraw into the Matobo Hills. AmaNdebele forces was estimated at 4,000 men and their casualties from 200-300. Plumer’s force numbered 760; of which 6 died and 15 were wounded. Lieut McCulloch, who was wounded in the leg at this fight, states that the artillery fired “three ring, twenty-one shrapnel and eight case. We opened up with case quite blank at close quarters, the rebels trying to rush the guns, and coming to within thirty or forty yards of the muzzles.”

All in all the amaNdebele showed a better appreciation of the military situation and used the rocky kopjes and steep slopes to their advantage and definitely gained the advantage that day. R. Baden-Powell’s estimate of their losses was probably greatly exaggerated and his claim that this battle represented a “victory” for Colonel Plumer is not justified. It is surprising that Captain Hoël Llewellyn for his single-handed action manning the Maxim gun at a desperate time was not awarded a military medal for his gallant conduct.

On hearing news of the engagement, General Carrington and Rhodes left Bulawayo and arrived at Fort Nsezi on the evening of the 5th. It is becoming more and more obvious to Cecil Rhodes, whose British South Africa Company was paying all the expenses, that the military campaign will be extremely difficult and costly to settle by force of arms, particularly as General Carrington is insisting that he will require another 5,000 European troops to continue the campaign with any hope of defeating the AmaNdebele.

7th Aug – a decision is made to build a fort on the site of the Sugarbush camp to be called Fort Nsezi, after the nearby river, but known from 22nd September 1896, as Fort Umlugulu.

8th Aug - Baden-Powell leads the next attempt against the AmaNdebele, with a night march onto Tshingengoma. There is complete confusion with elements of the column getting lost in the darkness; when dawn breaks Baden-Powell on the summit of Tshingengoma can see the rear-guard wandering aimlessly around in the ravines below him. Honour is satisfied with the artillery pounding the supposed AmaNdebele positions, but without achieving any tactical military advantage.

14th Aug - the troops at Fort Nsezi are afforded some relief from the monotony of camp life and fort building by a sports day, but the other forces are not informed and the shooting during the V.C. race causes concern to the other garrisons in the Matobo, who send out patrols to investigate and to newly-arrived Imperial reinforcements whose advance guard galloped into the camp to investigate.

15th Aug – Rhodes returned to Fort Nsezi to continue the negotiations that had begun when Baden-Powell and the Native Commissioner, J. Richardson, had captured one of Mzilikazi's wives, Nyambezana, the mother of Nyanda. She was held at Fort Nsezi for a week and then became the go-between in the negotiations that now opened, as it became clear that some of the amaNdebele wished to surrender. She was asked to return to her home and make contact with the rebel indunas. If they wanted to make peace, she was to fly a white flag over her hut: if they elected to go on fighting, she was to hoist a red flag.

19th Aug – with the new fort Nsezi practically complete and soon to be renamed Fort Umlugulu, the main body withdrew to its main camp at Malema in the western Matobo.

21st Aug - Rhodes leaves the camp outside Fort Nsezi to meet the rebels for the first indaba. [For a detailed account of this see the article “The Matabele uprising or First Umvukela Indaba site (Rhodes Indaba site) on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Fort Umlugulu (previously Sugar Bush camp, then Fort Nsezi)

No action was ever fought at this fort, but many engagements took place in the nearby hills between the AmaNdebele tribesmen and the Imperial forces that were camped here.

It was from Fort Umlugulu that JP Richardson, Native Commissioner and Zulu linguist, John Grootboom and James Makunga went into the Matobo hills at great personal risk to arrange a meeting with the Ndebele Indunas. Rhodes returned on the 15th August and left from here with Grootboom, Makunga, Sauer, Colenbrander and Stent for the first of the Indabas on the 21st September 1896 which resulted in the end of the First Umvukela. [Refer to the article on the Matabele uprising / First Umvukela Indaba site]

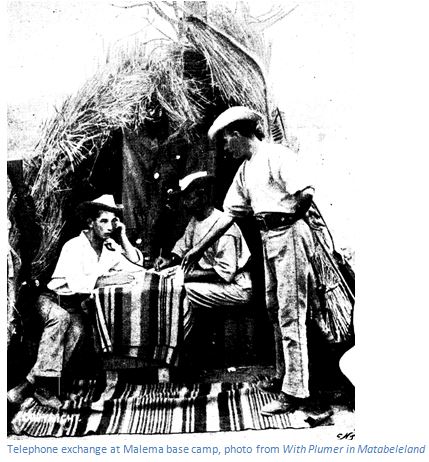

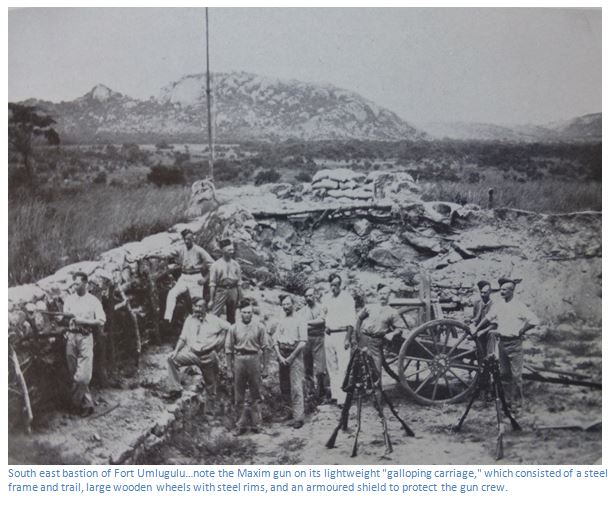

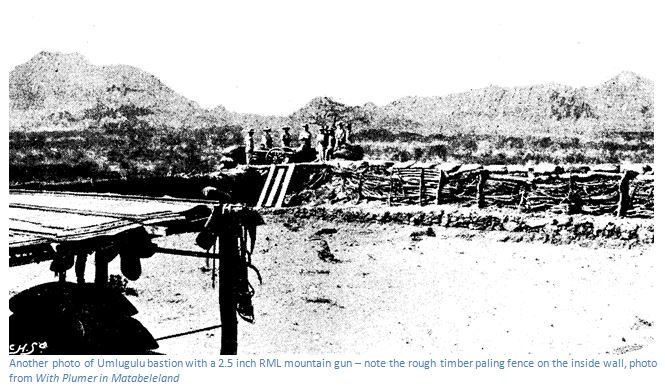

Robert (later Lord) Baden-Powell was one of the members of the small party that designed and stayed at the fort. It is said that he first thought of the idea of the Boy Scout movement during his scouting expeditions into the Matobo hills. The fort, the only one in the area with well-constructed pole and dhaka huts for the troops and garrisoned by 60 Police with a seven-pounder gun, a 2.5 inch RML mountain gun (a British rifled muzzle-loading mountain gun of the late nineteenth century designed to be broken down into four loads for carrying by man, or mule) and one or two Maxim machine guns, called "sigwagwa" by the Ndebele for the noise they made when firing. On completion on 22nd September the name was changed to Fort Umlugulu.

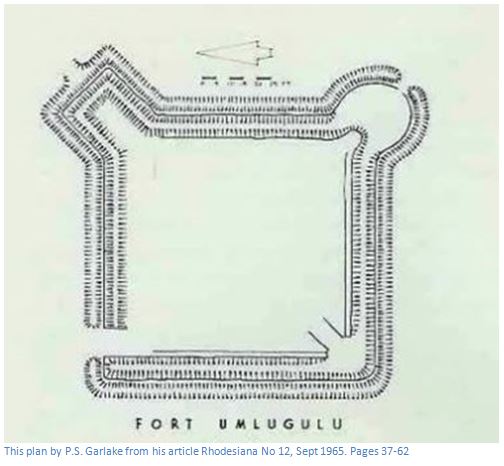

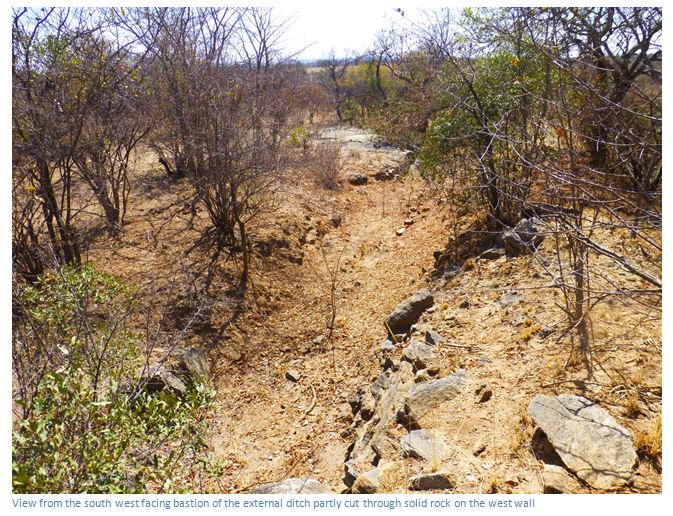

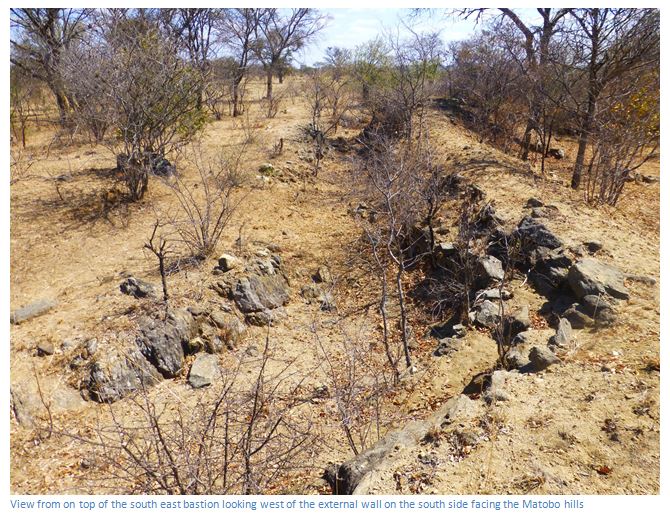

My only slight criticism of the plan by Garlake is that the fort faces north east, and not north as shown, with the most strongly defended wall with the two bastions facing south west towards the Matobo hills.

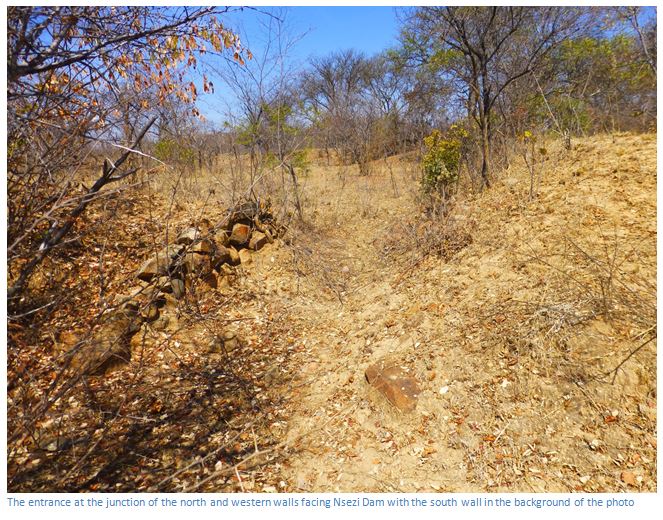

The fort was sited in a good location being on top of a ridge with clear views across to the Matobo hills and just 150 metres south of the small stream that flows into the Nsezi River and just 330 metres north of the Nsezi River itself.

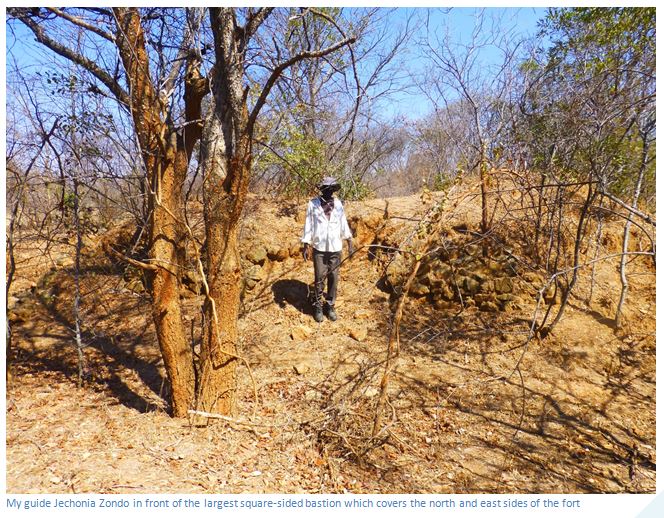

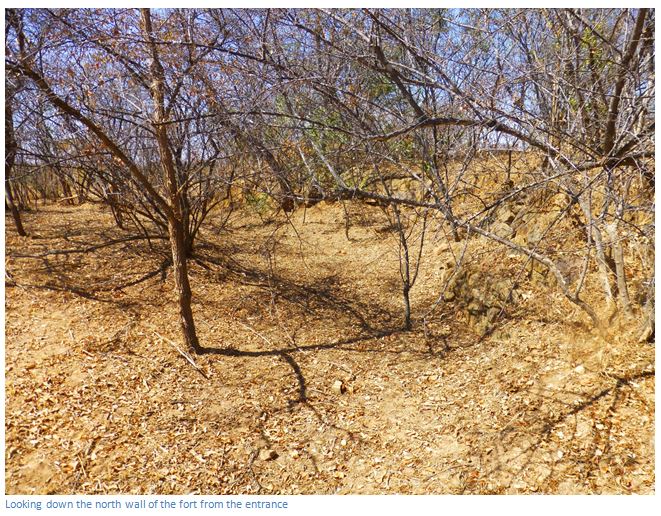

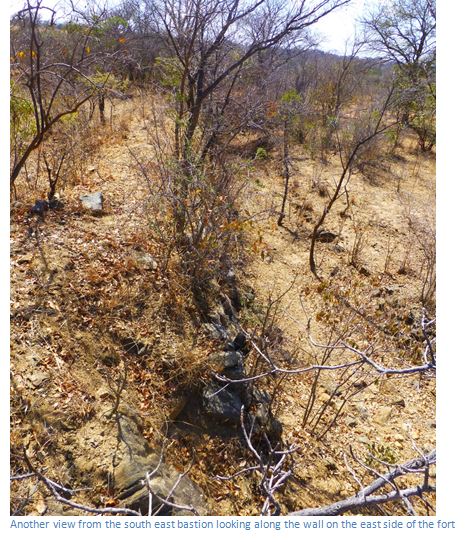

The basic shape of the fort is a square made up of earth walls with bastions at the north east, south west and south east corners; the entrance being on the north west. The external dimensions of the walls are 30 metres by 30 metres and they still remain one metre high and nearly two metres high on the bastions.

The south west bastion still has its ramp for pulling up a Maxim gun; the seven pounder gun would have been fired from within the interior of the fort. As I.J. Cross says in his article Rebellion Forts in Matabeland in Rhodesiana No. 27 contemporary photos show some kind of staging was erected on the bastion, no doubt to give some elevation as a lookout.

In his article Rebellion Forts in Matabeland I.J. Cross says the old Bulawayo – Tuli road crossed to the east of the fort and that he found traces of dhaka hut bases between the fort and the old road, probably for the fort’s troops, but I think these have been damaged by cultivation now as I could not find any dhaka remains.

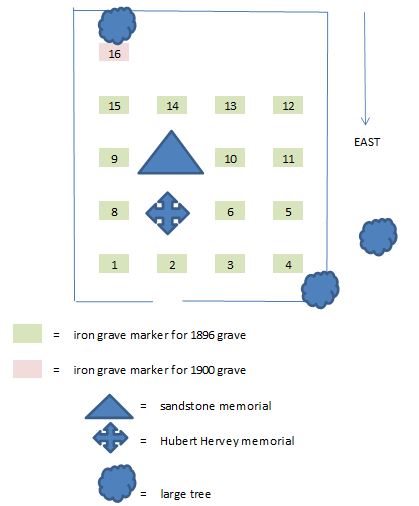

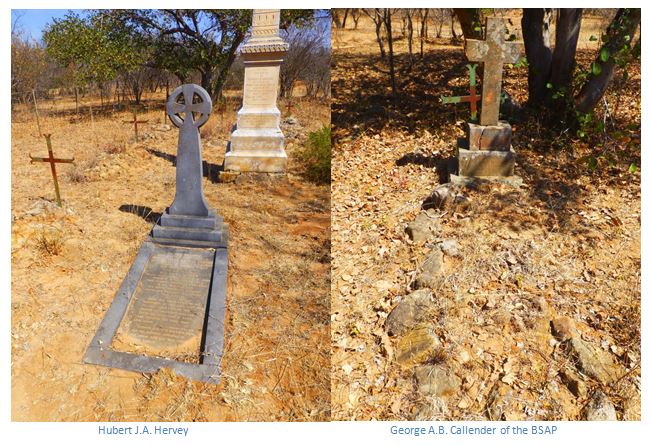

There are sixteen marked graves within the cemetery nearby; however the most western grave relates to the death of George A.B. Callender of the BSAP who died at Umlugulu on 2nd May 1900 aged 24 years.

All the fifteen other grave markers refer to those who were killed in July / August 1896. The mystery is that there are sixteen names on the Umlugulu Memorial which was erected by the Rhodesia Memorial Fund. The names of those most likely buried in the cemetery in date of death order are:

| Name | Unit | Place | Status | Date of Death |

1 | Greer, Stuart George | BFF | Gwanda Patrol | KIA | 10 April 1896 |

| Packe, Christopher J. | BFF | Gwanda Patrol | KIA | 10 April 1896 |

2 | Bennett, Peter Tpr. | MMP | Inugu (T-Laing) | KIA | 20 July 1896 |

3 | Bush, William H. Tpr. | MMP | Inugu (T-Laing) | KIA | 20 July 1896 |

4 | Hall, John Cpl. | BeFF | Inugu (T-Laing) | KIA | 20 July 1896 |

5 | Bern, William Tpr. | BFF | Inugu (Nicholson) | wounds | 27 July 1896 |

6 | Cheves, Laurence Tpr. | BFF | Inugu (Nicholson) | wounds | 27 July 1896 |

7 | Little, Edward R. Tpr. | MRF | Spargo store | accident | 3 August 1896 |

8 | Ainslie, Alexander Battery Sgt-Maj. | MMP | Sikombo | KIA | 5 August 1896 |

9 | Gibb, William, Sgt. | MRF | Sikombo | KIA | 5 August 1896 |

10 | Innes-Ker Archibald Sgt. | MRF | Sikombo | KIA | 5 August 1896 |

11 | Kershaw, Frederick E. Maj. | MRF | Sikombo | KIA | 5 August 1896 |

12 | McCloskie, Oswald D. Sgt. | MRF | Sikombo | KIA | 5 August 1896 |

13 | Hervey, Hubert J.A. Lt. | MRF | Sikombo | wounds | 6 August 1896 |

14 | Holmes, Alfred J.E. Tpr. | MRF | Sikombo | wounds | 9 August 1896 |

15 | Parr, Harry A. Tpr. | MRF | Inseza camp | typhoid | 17 August 1896 |

MMP = Matabeland Mounted Police | |||||

BFF = Bulawayo Field Force | |||||

BeFF = Belingwe Field Force | |||||

MRF = Matabeland Relief Force | |||||

The most deadly skirmish for the Imperial forces was on 5th August 1893 at Sikombo, or Tshingengoma battle with Father Marc Barthelemy reading the burial service over them, the rest died elsewhere in the Matobo. The BSAP compiled lists of the names of those buried at each site around the country before 1908, thus there is no confusion about George A.B. Callender being allocated a grave marker because he died before 1908. Lists were then drawn up by the Guild of Loyal Women (GLW) that were sent to be cast as the familiar circular cast iron grave markers by the Gregory iron foundry firm in Cape Town.

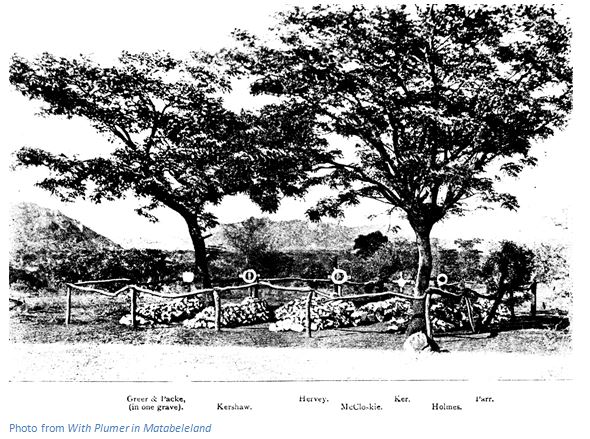

Greer and Packe appear to be buried in one grave as can be seen from the Sykes photo below.

The two individuals below are listed on the Umlugulu cemetery memorial, but they are probably buried in Bulawayo as there is a memorial and grave in the Bulawayo cemetery.

Worringham, Frederick C. Sgt | MMP | Babayana's kraal | KIA | 20 July 1896 | |

Morgan, Charles O. Tpr. | BFF | Inugu (T-Laing) | wounds | 23 July 1896 |

However, as can be seen from the photos, the cross-shaped grave markers have been left, but all the circular cast iron grave markers with the details of the individual have been removed. So there will be no solution to the question of who was the one individual listed on the Umlugulu Memorial who is not buried within the cemetery, and it is not possible to say who is buried where within the cemetery.

The cemetery plan is as follows:

The Lieut. Hubert John Antony Hervey memorial reads in full: To the memory honoured and much loved Hubert John Antony Hervey, youngest son of Lord and Lady Alfred Hervey, and grandson of Frederick William, First Marquis of Bristol, born 19th May 1859, died 6th August 1896, having been mortally wounded in action when gallantly serving as a volunteer in the Matabele War. His deeply sorrowing brothers, sister and sister-in-law erected this cross. Nearby Falcon College has six Houses and one of them is named after Hervey. Frank Sykes in his book says that one of his last remarks was: “Well, I suppose before long I shall be extending the British Empire in Jupiter or somewhere else.”

Holmes upper thigh was shattered by a piece of quartz encased in lead.

The loss of Major Kershaw was keenly felt by all the troops of the MRF as his courage was legendary.

After the burials on the Thursday 6th August the troops were drawn up into a hollow square and addressed briefly by Maj-Gen Carrington who congratulated them on their achievements and expressed deep regret at the loss of lives.

This is Umlugulu cemetery as photographed by Frank Sykes within a few months of August 1896. Strangely, Greer and Packe, both killed on the Gwanda Patrol are shown on the far left as buried in one grave. Selous in Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia says five troopers were KIA on the Gwanda patrol and their bodies had to be left on the field; he names E. Heyland, J.M. Forbes, S.G. Greer, C.J. Packe (all of C Troop, BFF) and Green. However, there is no Green listed in the ’96 Rebellions lists and I think Green is a misspelling of Greer.

R.A. Baker of the Afrikander Corps died the next day of his wounds, making five casualties.

Why Greer and Packe were buried here at this time, but not their three comrades is a mystery.

This close-up photo by Frank Sykes of the graves shows why there is so much confusion over gravesites in this country. Memorial crosses erected were made from wood with the names and details carved onto tin-plate. Within a year or two at most, termites would have eaten the crosses, or they were destroyed by veld fires and so the original location of the individuals within gravesites became confused.

This photo of Frank Sykes is included because his book provides so much useful information on the MRF campaign in the Matobo hills. The experience was still so raw that “Jim” on the left of the photo was still so afraid he would not leave Fort Usher and go with them into the Matobo hills.

Acknowledgements

P.S. Garlake. Pioneer Forts in Rhodesia 1890-1897. Rhodesiana No. 12, Sept 1965. Pages 37-62

I.J. Cross. Rebellion Forts in Matabeland. Rhodesiana No. 27

One Hundred Years On - A record of Baden-Powell's exploits in the Matopos and Matabeleland 1896 at the Gilwell Reunion at Gordon Park on 12 - 13 October 1996

F.W. Sykes. With Plumer in Matabeleland. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo. 1972

The ’96 Rebellions. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo. 1975

When to visit:

All year around

Fee:

None

Category:

Province: