Home >

Matabeleland South >

Fort Rixon Rebellion Memorial (Matabele Uprising, or First Umvukela, 1896)

Fort Rixon Rebellion Memorial (Matabele Uprising, or First Umvukela, 1896)

National Monument No.:

58

Why Visit?:

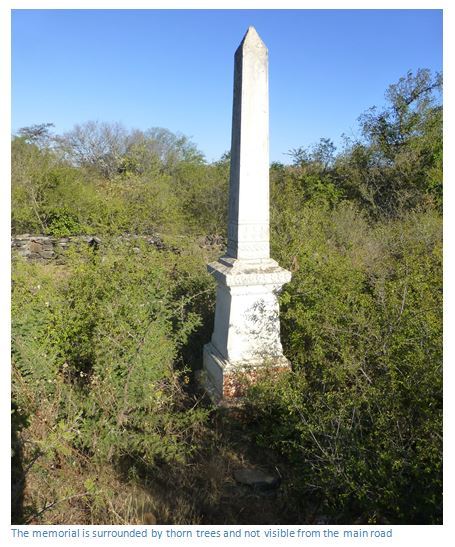

- The Memorial in the shape of an obelisk with the names of 13 civilian dead on the north side panel and 3 military dead on the south side panel is barely visible from a few metres away and stands hidden and forgotten in this remote place far away from any towns and the nearest village of Fort Rixon. Those whose deaths it commemorates are long forgotten; the Cunningham family suffered nine fatalities.

- 145 civilians were killed of whom the great majority of 121 were killed between the 23rd – 31st March 1896; 16 in April and only 8 others in the following months to December 1896.

- Although the local people may not sympathise with the Memorial, their respect for the dead has meant that it is remained in as good condition today as when it was built.

How to get here:

From Shangani take the A5 towards Bulawayo, 18.4 KM reach Insiza and turn left onto the untarred road heading south-east, 45.8 KM reach Fort Rixon road junction, 46.9 KM turn left towards Fort Rixon, 48.1 KM pass through fort Rixon, 55 KM turn right at the intersection, 58.2 KM continue on at road intersection, 61.8 KM continue south at road intersection, 65.9 KM turn right at the road intersection. [Note: the road to the left leads to Zinjanja Monument and the Bertrand and Aleth de Guitaut Memorial and you are now in the midst of an artisanal gold mining area] 67.1 KM turn sharp left onto a track, the Rebellion Memorial is 40 metres up the track on the right-hand side and almost obscured by thick thorn.

This is sometimes also called the Claremont Memorial because it is on the former site of the Claremont gold mine, or the Cunningham Memorial because the entire family perished.

GPS reference: 20⁰09′01.51″S 29⁰19′56.18″E

The memorial names the following civilians on the north face:

To the memory of James Cunningham, his wife Sarah and their children

James Samuel

Henry Dadson

Alice and Mary, their grandchildren

Evelyn, William and Frank Milne

Thomas Maddocks

Thomas Langford and Laura, his wife

C.J. Leman

The following military on the south face:

And of the following who

Were killed in action

John O’Leary Sergt. MMP 27 March 1896

Arthur Parker

George Rootman

Tprs. BFF 22 May 1896

In this district

The three years following the death of Lobengula in 1893 included a great drought, swarms of locusts that devoured every green thing that had survived the drought and was followed by rinderpest that destroyed all the remaining cattle and the game. The Ndebele persuaded themselves through the Mlimo who dwelt in the Matopos hills that all these ills were attributable to the new white settlors. “Until the blood of the white man is spilt”, said the Mlimo, “there will be no rain.” Within days of the first killings on March 23rd, the rains long overdue, began to fall. To the Matabele it was proof positive that the Mlimo had spoken truly and the omens for the Uprising were good.

Peter Baxter says in the series History of the amaNdebele (peterbaxterafrica.com) that the uprising was planned for the full moon of March 28 1896 and no hint whatsoever reached the ears of white settlers and administrators; even long-time residents of Matabeleland such as the Rev. Charles Helm of the Hope Fountain Mission and Frederick Selous, who had recently been appointed cattle inspector for the districts between Umzingwane and Insiza, had no inkling of what was about to happen. Only William Usher, long time Matabeleland trader and former confidante of Lobengula, maintained loudly and consistently that a native uprising was inevitable; the response of the administration was that he would be clapped in gaol if he continued to spread alarm and despondency.

The amaNdebele plan was that on the full moon the amaNdebele fighting men would arm and assemble along the outskirts of Bulawayo and the town would be rushed and the whites slaughtered. Bulawayo would not be destroyed because it would be the royal seat of a reincarnated Lobengula. Thereafter, the impis would break up and surge throughout the country mopping up isolated white settlements and those that survived the assault of servants and retainers.

However, on the evening of 20 March 1896, a small detachment of amaNdebele rebels sprung the plot prematurely. The story related by Selous in Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia was that eight native police details with their carriers arrived towards evening in the Umgorshwini kraal, south of Bulawayo. The group camped outside the town, and were approached as they sat around their campfire by a body of armed amaNdebele who adopted an aggressive attitude, although they did not immediately attack. The policemen were taunted and insulted before a scuffle broke out, shots were fired, killing first one of the attackers and then a carrier, with a second carrier being clubbed to death with a knobkerrie. Later that same evening, a lone native policeman on leave was killed in a neighbouring village.

Three days later the killings of Europeans began. Some disagreement exists on the exact timing and sequence of the first attacks, but probably on Tuesday 24 March when 4 whites, 2 ‘colonial boys’ and a ‘coolie’ cook were killed at Edkins Store, and the local Native Commissioner, Arthur Bentley, was surprised and murdered while seated at his desk, with his last words written dated March 23 1896. A further two men were killed at the Celtic mining camp and between the camp and the store and many more in the Filabusi district. [See the article the Filabusi Memorial and the Edkins Store killings on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] Next, in Insiza district,the farmhouse of the Cunningham family was attacked and the family of nine individuals, including three children, were killed with axes and knobkerries. This was followed by the killing of Thomas Maddochs, the manager of the Nellie Reef Mine nearby at Insiza and close to the Fort Rixon Rebellion memorial.

When the scene was discovered it was also reported that all the surrounding amaNdebele villages and kraals lay deserted, leading to the assumption that again it was natives of the immediate vicinity who had been responsible for the killings. “From the Umzingwane,” Selous wrote, “the flame of rebellion spread through the Filabusi and Insiza districts, to the Tchangani (Shangani) and Inyati, and thence to the mining camps in the neighbourhood of the Gwelo and Ingwenia rivers, and indeed throughout the country wherever white men, women, and children could be taken by surprise and murdered either singly or in small parties ; and so quickly was this cruel work accomplished, that although it was only on 23rd March that the first Europeans were murdered, there is reason to believe that by the evening of the 30th, not a white man was left alive in the outlying districts of Matabeleland.”

Peter Garlake writes in Pioneer forts in Rhodesia 1890 – 1897, printed in Rhodesiana no 12, September 1965 that when the news reached the settlors of the murders in their area they planned to gather at Rixon’s Farm, where the Bulawayo – Belingwe road crossed the Insiza River, but instead laagered at Cumming’s Store and were brought to Bulawayo two days later. Dr. and Mrs Langford and C.J. Leman were making for Rixon’s Farm when they were attacked and the men killed. Mrs Langford fled to Rixon’s Farm, but found it deserted and hid alone in a nearby river bed for several days before being she was discovered and killed. Col. Napier’s Gwelo (now Gweru) patrol found the bodies in May 1896 but also lost two troopers in the area, Arthur Parker and George Rootman. [Those names in black italics are listed on the Fort Rixon memorial]

One hundred and forty-five settlers were killed in Matabeland during the Uprising. Obelisk Memorials bearing the names of those murdered by the Ndebele have been erected here and there in the veld, on or near the scene of death. The Filabusi, the Pongo, the Mambo and the Fort Rixon Memorials have been declared National Monuments and bear the names of many of those killed.

Peter Baxter writes that in terms of organization and battle readiness the amaNdebele seemed to have suffered significantly from the absence of a tight military command system, a situation aggravated by the central leadership vacuum since Lobengula’s death and this was also the first war fought without reliance on the traditional tactics evolved over the long years of amaNdebele military dominance. There were many guns in circulation at that time; according to Selous at least 2,000 breech loaders were in use during the uprising, mainly Martini-Henrys, with some 100 Winchester repeaters taken over to the rebels by the native police. A good many Lee-Metford magazine rifles had also found their way into Ndebele hands through theft or private purchase, or as a consequence of illicit gun running in the years leading up to the uprising and a random collection of muzzle loaders in varying states of age and disrepair.

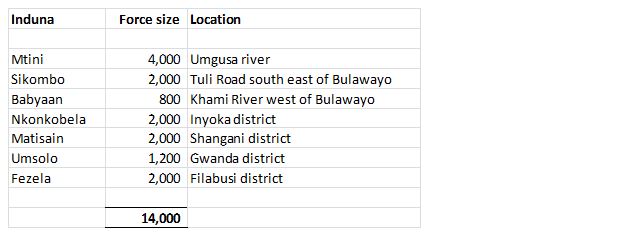

The Ndebele forces numbered approximately the following:

The following long account is quoted from The Matabele Rebellion, 1896: with the Belingwe Field Force by their commander Major D. Tyrie Laing, because it shows the complete surprise achieved by the uprising and the news of the first murders, whose names are inscribed on the Fort Rixon Memorial. [See also the article The 1896 siege of Belingwe, now Mberengwa as told by David Tyrie Laing under Midlands Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] Messages were sent out to the surrounding miners to collect at the Belingwe Store and although the lack of news made all 33 of them very nervous, they fortified their position in expectation of an imminent attack: designing an alarm system rigged on a trip wire to fire a gun and constructing dynamite mines.

“The first intimation we, at Belingwe had of any real danger from a rebellious rising of the natives in Rhodesia was on the morning of the 26th of March, 1896. About 7.30 a.m., whilst at breakfast, Mr. A. J. Wilson and I were surprised by a visit from Mr. S. N. G. Jackson, the Acting Native Commissioner at Belingwe, who appeared rather excited. After having been asked to take a seat, he explained to us that he had just received, by a native police runner, a letter from Mr. Fynn, Acting Native Commissioner at Inseza, which he handed to me. It was as follows;-

Sir, — I regret to have to report to you that the whole of the Cunningham family have been brutally murdered, and also Maddocks, manager of the Nelly Reef. Two of his miners got off, severely cut about. These two miners tell us that about thirty natives came up to their camp in a friendly way and sprang upon them with kerries and battleaxes. This happened the night before last, between six and seven. All the Europeans in this part of the district have concentrated here, as things look very serious as regards the natives. All the natives have cleared out of their kraals; probably fearing that the murders having been committed in their district they will be blamed.

It is hard to say whether this organisation has been general throughout the country, which I fear is the case. We have received no communication from either Buluwayo or Filabusi yet. I would advise you to see Captain Laing and get all the prospectors to concentrate at the Belingwe Store, until we can get further news. We expect someone over this morning from town.

One of the murderers was shot by the police I sent after them. They came across five of them, all with guns, and that these men were Maholes I cannot believe. That the gang were composed of Matabele — I should rather think they were Matabele. Coach has not arrived yet.

I have the honour to be,

Yours obediently,

H. P. Fynn, A.N.C.

After discussing the situation for a few minutes it was decided to send out information to all the outlying camps, as soon and as quietly as possible — Jackson sending out his two mounted white police and several native police, and I despatching my engineer, Edwin Vallentine, who happened to be at hand at the moment, on one of the company's best horses, to call in all the miners working for the company, and all others on his route to and from the different camps. His instructions were to ride as hard as possible, see the men at the various camps, tell them to take their bandoliers and rifles, go to the different works and order the natives employed to put all provisions and light stuff into the company's wagons, all the heavy and less damageable material down the shafts, bring the ropes away, inspan the wagons, and get back to headquarters camp as quickly as possible, fetching as many natives as they could with them, but under strict surveillance.

I strongly advised Mr. Jackson to disarm his native police at once, but he had great faith in their loyalty and demurred; and as I was not then quite sure of the position, I did not think it advisable to interfere with one of the Chartered Company's officials — especially when he was doing his very best to assist — although at the time I felt certain that the native police would be on the side of any uprising in Matabeleland. I, however, came to the conclusion to leave Mr. Jackson to carry out his own ideas for the time being, but made up my mind to watch the police under him very closely.

As soon as the messengers were sent off I went up to the camp of Sir Frederick Frankland, Assistant Mining Commissioner of Buluwayo, which was only about a hundred yards from my house. Wilson went over to the general store to warn the men there and get the ammunition and rifles in readiness. Sir Frederick had only arrived in Belingwe from Inseza two days before the outbreak, accompanied by his assistant, W. C. Beaty-Pownall, and was engaged in inspecting the different mining properties in the Belingwe district for the Chartered Company. They were just about to saddle up and go out for the day when I got to their camp. I could see at once that they had not heard of the native rising, I told them what I had heard and had already

done. Sir Frederick was very much upset when he learnt of the fate of the Cunningham family. He had been a guest at their house only a few days previously, and had been all over the Inseza district, where most of the murders had been committed, and knew nearly all the people there. He and Pownall at once decided to throw in their lot with the Belingwe men, and volunteered their assistance on the spot.

The disarming of the native police was then discussed, and Sir Frederick coincided with my opinion. We then rode over to the police camp, unarmed, so as not to cause any suspicion. Mr. Jackson had gone off, leaving Mr. W. R. Wilson, his assistant, in charge. We told Mr. Wilson we were in favour of having the native police disarmed, and he thought it was advisable, but would not do anything in the absence of his chief. We then decided to leave matters as they were for the time being, and proceeded to the general store, which was about a thousand yards from the police camp. Here we found all my company's employees busy getting their rifles and ammunition ready for the men coming in from the outlying camps. Sites were then selected on which to erect two small redoubts, to protect the store and cover the defenders.

About 11am Mr. Malcolm McCallum, manager for the "Buluwayo Syndicate," rode up to the store to see me. He said, “I have had notice from the police, and have put my men on their guard, and have come to see you and find out what is to be done." The situation was explained to him, and he departed at once, to bring in his men and supplies.

Shortly after midday my company's wagon, with the miners from "The Bob's Luck" and "Wanderers' Rest" and Mrs. Mitchell, came into camp. Mr. Mitchell, who was in charge of "Bob's Luck," reported that he had tried to carry out the instructions sent, and had succeeded in getting most of the mining plant under cover before the natives deserted. This they did at the very first opportunity, disappearing in the bush in every direction.

James Low, who was in charge of the "Wanderers' Rest," reported that the natives worked well and got all the mining material down a deep shaft, but when carrying the food stuff to a spot where the wagon had to pick it up, they waited a favourable opportunity, destroyed most of it, and disappeared in the bush. The above reports left no doubt in my mind as to the seriousness of our position. It appeared very plain that all the natives had an idea of what was going to happen.

Towards evening Harry Posselt, W. Lynch, and C. F. W. Nauhaus, farmers, who lived close to the Doro Mountains, about twelve miles away, came into camp and reported that fifty-six of their trek oxen had been looted during the previous night.

At 8pm a meeting was held in the Belingwe Hotel, at which there were thirty- three present. This number was about ten men short of what we had estimated to be in the district at the time. Five of these we knew were at the "Sabie," twenty-five miles distant, and could not possibly be in for another day. Two others were at a camp about three miles away, who pooh-poohed the idea of a native rising; the remainder we expected were on their way in. Some of the men present had walked in eighteen miles, and it was very gratifying to notice the readiness with which most of the men in the district had grasped the situation and come in at once, to give all the assistance they could. The meeting appointed me their chairman. I read Mr. Fynn's letter and explained all that had been done and what had actually happened during the day as far as my knowledge went.

As the commanding officer of the volunteers in the district addressing them, I said that I would at once place them on an active service footing. With regard to the burghers, it was explained to the meeting that they had been asked to concentrate solely for the purpose of protecting life and property, and that the camp, as far as they were concerned, was purely a voluntary one. I asked them to do what they thought best, under the circumstances, and to co-operate with the volunteers, for the mutual defence of all. They unanimously agreed to place themselves under my command, and elected Sir Frederick Frankland to be their lieutenant and second in command.

A portion of the white men were then detailed to superintend the erection of the redoubts by about seventy natives, who had been brought into camp. The natives worked with a will when they were told the white men knew all about the uprising, and that if any of them attempted to escape until the works were completed, they would be fired on. They were also informed they would be at liberty to go, or stay with us as soon as the works were finished. The moon was just about two days from being full, and served us beautifully, and it was a stirring sight to see the natives hard at work, under the white guards, who, on this occasion, had a trying duty to perform, namely, to keep a look-out for a possible enemy in front and treachery from the enemy employed within. By the time the moon went down, about 3am the following morning, the redoubts were so far advanced as to offer cover for the defenders. The work was then stopped, the natives marched into the store paddock, and sentries were placed over them. A guard was mounted and sentries put on wherever it was considered the best positions were. The remainder of the white men lay down close to the earthworks, with their arms handy, and patrols were sent round the cattle kraals at intervals; but nothing of any importance happened. Thus, through the timely warning sent from Inseza by Mr. Fynn most of the men in Belingwe were banded together and in a position to protect themselves and public property in less than twenty-four hours from the time the warning was received.

The Acting Native Commissioner and his assistant slept at their own camp, about a thousand yards from the position we had fortified. When morning came they found the native police had built a bush scherm between their own quarters and those of their officers. This rather damped Mr. Jackson's belief in their loyalty. He came in and reported the matter and then he and his assistant joined the other white men in garrison. The police were brought down and placed under cover of one of the forts, about a hundred yards away, but as several of them had faithfully carried the despatches entrusted to them, and had been the means of advising many of the white men, it was very difficult to decide what to do with them. They protested that they were not a party to the uprising, and that they wanted to be faithful to the white men. They were strictly watched, but allowed to keep their arms.

All hands were kept busy during the 27th March putting the finishing touches to the forts and covering their approaches with a strong abattis made of the large hook thorn and other trees. Towards the evening W. Sheldrake came into camp just as the men were being told off to their posts for the night. He reported that Stoddart's camp at the "Great Belingwe” mine had been looted by the rebels, and nineteen trek oxen were missing. He had had to run the gauntlet of the rebels' fire as he was on his way to the fort. Bergqvist, his comrade, had gone to look after the missing cattle. I felt very much annoyed with these men for not taking the timely advice sent to them, and acting in concert with the others. Had they done so their camp and cattle would have been saved, for they were the first men Vallentine saw on his way out. It was pure selfishness that kept them away from the other men, and when it was suggested that a party should be sent out to try and find Bergqvist. I did not think it was proper that any lives should be risked for him, seeing that he had had the best chances of any at first; and it was only when a party of volunteers came to me on the morning of the 28th and said that they wished to go out and endeavour to find out what had happened to Bergqvist, that I agreed to let them go. I admired the sentiment that prompted the volunteers to go in quest of their comrade. The following men were allowed to depart, namely, W. R. Wilson, H. Posselt, Corporal Daniell, Corporal Le Vierge, H. Paulsen, and C. Paulsen. They were mounted on the best horses we had in the camp, and left about 6.30 a.m. They had not gone half an hour before Bergqvist came into camp and reported that on the evening of the previous clay he had followed up the spoor of the missing cattle and come up with them before sundown. They were then being driven to the southwest by a large party of armed natives, who laughed at his vain endeavours to drive his cattle back, evidently enjoying his discomfiture. Although they were all armed, they did not attempt to hurt him, only driving the cattle along a little faster and jeering at him when he gave up his efforts to recover his oxen. The patrol returned about 1pm and reported that all the provisions at Stoddart's camp were destroyed and scattered over the veldt.

The defence works at the store were still being carried on and improved and the men told off into two divisions — No. I division for No. 1 fort and No. 2 division for No. 2 fort. A guard was mounted at sunset and six sentries posted round the laager. The native police were posted and had charge of the cattle; four hundred of which were kraaled about a hundred yards northwards from the laager. They also had a few sentries posted outside the white sentries. This brings us to the evening of the 28th March. Shortly after sundown two shots were fired by the police sentries. The white sentries at once retired on their forts, according to orders, and the forts were manned. Mr. Jackson and Mr. Wilson went immediately to find out what the native sentries had fired at. The sentries said they saw several Kaffirs moving about in front of their posts, and that they fired on them. Shortly afterwards the Native Commissioner and his assistant again went out to the cattle posts, and returned to report that all the native police, with the exception of three, had deserted, taking with them twenty rifles and ten rounds of ammunition per man. Not long after this several signals were heard by the white sentries near the cattle kraal. I then took out a patrol of eight white men, in skirmishing order, and got past the cattle kraal. The inside of the kraal was examined and two natives were found hiding. They said they were hiding from the police and on being identified as herds, were allowed to join the other natives in the compound.

I was under the impression that they were placed inside the kraal for the purpose of driving out the oxen when the proper moment came, but as our sentries were too much on the alert, the police had decided to go without the cattle for the time being. The three native police who remained were disarmed, but they could, or would, give no information. Two days afterwards they were allowed to go out to bring in some mules from Posselt's farm, but, needless to say, they never returned.

I am quite sure that many people who may read this will think I was wrong from the beginning in not having the police arrested and disarmed. At the time I felt convinced I was wrong; but what otherwise could anyone have done when everything is considered? First, a native policeman brought us the warning; then, after they knew we were on our guard, they took our messages to isolated white men — some of whom were twenty-five miles away from our laager — and as we had no information from outside, I think it would have been very unfair to have treated them as rebels until they proved themselves such.

On the 29th we still went on strengthening our defences, the cattle kraal was moved close up to the laager, an abattis put right round the whole place, and several dynamite mines were set, to be fired by electricity. Luckily, my company had three strong electric batteries and any amount of wire and connections, which were of great utility under the circumstances.

This evening H. Posselt and W. Lynch, two of the troopers, who knew the country well, volunteered to try and get through, if possible, to Buluwayo with despatches, in order to let the authorities know we were all right in Belingwe, and to bring back all the information they could in regard to the uprising. They left after dark, mounted on two of our best horses, and returned on the morning of the 31st, just as the sun was rising. They reported that they got as far as the Inseza, which is about fifty miles west of Belingwe, on the road to Buluwayo, and found that place deserted by all white men. A small laager had been formed at Cummings' store, which had evidently been attacked. There were several dead bodies of natives lying about, but none of white men. The brick walls of one of the houses bore bullet-marks in many places. About three miles beyond Cummings' store they saw the bodies of a woman and child, both disembowelled. As they approached the river, at the foot of the western slope of the Inseza hills, they were fired upon from the thick bush by a body of native police, who were evidently stationed to guard the drift. Posselt and Lynch were forced to return. It would have been useless to have gone further, as they would have been overpowered. Luckily they got off clear, Posselt only losing his hat. We were all very pleased to see them back, and although they had failed to accomplish their object, we knew it was not their fault. The fact, however, of their not being able to get through made us think more seriously of the position we were in, and very anxious to know what was happening in other parts of the province.

Every morning and evening mounted patrols were sent out in different directions to watch the approaches, and patrols of Cape boys were sent up and down the river-beds every morning before the cattle were let out to graze. On the same morning, the 31st, the mounted patrol caught a native hiding in the bush, about three miles from the fort, and brought him into camp. On being questioned, he said — "I am one of the cattle herds, who ran away with the police from Belingwe. The police ran away because the Maholes had raided Bergqvist cattle. They went to Um'Nyati's. The police wanted me to go further with them, but I refused, and said I wished to return to my master, the Native Commissioner. At Um'Nyati's I heard that all the white men in Buluwayo were to be killed and also those at Inseza. I heard that the Impi was to kill all in Buluwayo first, and then come down this way and kill all here, and then on to Victoria. I also heard that ten white men had been killed at Inseza and that the others were in laager. I left here with four of us herd- boys and five police. I do not know who is supposed to be heading the uprising. Um'Nyati's people are at their kraal. They are not armed. I ran away from the police in the daytime."

The information got from this boy proved how very serious matters were, and did not tend to make the men in the little garrison of Belingwe feel any more comfortable than they were before the lad arrived. In fact this information had quite the opposite effect, and it was not long before I heard rumours that several of the more nervous men in laager had been discussing the advisability of moving the camp to Victoria. I called a general meeting in the store, and explained to those present that I considered the position we held a very strong and safe one and that it was the intention to continue strengthening it every day, and in doing so I would be glad to receive any suggestions from any one that might tend to that end.

With regard to the suggestion to move camp to Victoria, I said I was very sorry to think that there was any one present who had so little faith in himself or his comrades as to insult them by insinuating that they were not able to hold the position against anything in the shape of an Impi and that I was really surprised to learn that any of the men were becoming alarmed; that it appeared to me quite evident that the man who would advise the deserting of Belingwe did not know the difficulties that lay before him on the way to Victoria. I further pointed out that we were strongly fortified, in a good position, with plenty of water and provisions to last at least three or four months. I also stated plainly that if any man, or section of men, thought it best to move, he, or they, were at perfect liberty to do so, but once away from the range of our forts they would have to look after themselves, and that so far as the volunteers and myself were concerned, we would stay where we were, or if we were forced to vacate we would take the road for Buluwayo, because it was much more easy to travel on than the one to Victoria.

I also had the pleasure of informing the meeting that two of their number, who knew the different ways to Victoria, had volunteered to try and get through, and bring about three thousand rounds of ammunition - the only thing we wanted to make our position absolutely secure. The men were invited to speak their minds freely and openly, and after considerable deliberation all agreed to remain where they were F. Luckhurst and V. Lyle, the two men who had volunteered to ride to Victoria for ammunition, left after dark on two good horses. Just as the meeting ended, the signalman reported several white men coming in from the north. They were in the thick bush and evidently scouting the store. As soon as they saw white men moving about they came straight up, and we were very glad to welcome John, James, and Archie Cook, Walter Laidlaw, and C. C. Pike, from the "Sabie" district. The native policeman had delivered the message to them safely. They had started for the camp the following morning, coming slowly, and taking by-paths, in case of being surprised. They were all very tired and glad to get into camp.

On the 1st of April, I had all the dynamite removed from the magazine, close to the Store, and put down a shaft, about one mile away.

On the 3rd of April, shortly after daybreak, the sentry reported the approach of a white man. This proved to be James Stoddart, who had, on learning the seriousness of the uprising in Matabeleland, decided to come in from Victoria, in Mashonaland to warn his men in the "Sabie" district. His horse broke down before he had got over the first thirty miles, and he had to walk the remaining fifty, doing the greater part of the distance at night. He was surprised when he reached the "Sabie" camps to find them deserted, but, nothing daunted, came on with the intention of warning Belingwe, not knowing that we had already been advised. When he came in he was very footsore, hungry, and soaking wet, having lain the greater part of the previous night in the bush, on a small rise, about a mile east of our position, watching for any signs as to whether the store was deserted, or inhabited by natives or whites. He was very happy indeed when daylight came and he saw the white sentries on their posts and the place in a state of defence.

After he had partaken of some refreshment he made the following report: "When I left Fort Victoria there were about one hundred and twenty men, and sixty women and children in laager. They had between twenty and thirty horses, and provisions for all, to last about six weeks, and plenty of arms and ammunition. They were still in telegraphic communication with Buluwayo and Salisbury, and had received the following information regarding the uprising. It was generally supposed that the rising was general throughout Matabeleland and that one of Lobengula's sons was at the head of it. The headquarters of the rebels was in the Matopos Mountains. Several small patrols of white men had been sent out from Buluwayo to help in prospectors and others from the outlying districts. The leaders of these patrols were Spreckley, George Grey, Gifford, Napier, and Selous. A large patrol of about four hundred men was being raised to go out and strike a decisive blow at the rebels and the Chartered Company had ordered reinforcements from the Cape Colony of five hundred men, and Khama had offered his assistance. So far the telegraph wires had not been tampered with. About forty white men had been murdered so far as could be ascertained at present."

To us, in Belingwe, the information brought by Stoddart was most acceptable, because it showed us that, at all events, our comrades in other parts of the country were organising and defending themselves and preparing to strike a decisive blow. Stoddart's report was read to a full-muster parade at 8.30am and he received the thanks of the garrison and three hearty cheers for his gallant endeavour to bring the tidings of danger to Belingwe. He was unanimously elected a Lieutenant, and taken on the strength of the garrison.

About 8pm on the evening of the 3rd April Sergeant Lynch brought in a native prisoner, who had been caught inside our outer line of defence. I questioned him, and he willingly gave a glowing account of a journey he had just made from Buluwayo. He had left there only three days before with a message from W. Slade to his partner West, whom he expected to be in Belingwe, but, if not, he (the prisoner) was to proceed to Gondogue and deliver his message. He professed to be surprised at finding us in laager, and asked the reason why. He said the people in Buluwayo were going about as usual, that so were the people at Bembesi, as he came past, and at the Inseza. He had heard there had been some sort disturbances amongst the Maholes at Inseza, but that the native police had put a stop to it. The self-confident effrontery with which the prisoner answered all the questions put to him might have put us off our guard had Lieutenant Stoddart's statement not been made before, but being in possession of that it was quite easy to discern we had a very bold spy to deal with. After putting a few questions as to Gifford's fight at Inseza and telling him that we knew what had taken place at Bembesi, and that the people in Buluwayo were in laager, he was slightly nonplussed, and went away quite dejected when he found that we did not believe his story and that his visit had proved futile.

From the time we had formed laager up to the present the general defence works had been continued daily, and the men were drilled twice a day as well. The fact of natives being able to get through the outer fence and come close up to the forts without being noticed suggested the idea of an automatic sentry, in the shape of a signal-gun, which was erected forthwith on the top of the guard-room. It was connected with wires to the outer fence, which was divided into seven sections, each with an indicator, which dropped and fired a gun if anything attempted to force an entrance or pull away any of the bushes of which the fence was constructed. In about three days' time this automatic sentry worked so well that it was next to impossible to tamper in the slightest degree with any part of the fence or to get through it without first firing the signal-gun. In fact it worked so well, and we placed so much confidence in it, as to withdraw the seven sentries who were posted, previous to its erection, round the laager inside the outer fence. This proved a great boon to the men, and relieved them from a large amount of night duty, which had been very hard on them before, in consequence of many of their number being down with fever, caused by hard work during the day and having to sleep in the earthworks at night.

After this the men in each fort divided the night-watch amongst them, which generally ran to about two hours for each man per night. Three men at a time were on duty, sitting up on the ramparts of the redoubts, facing in different directions, the only outside sentry being one on the river bank, about twenty yards from No. 2 redoubt. The automatic sentry was always on the alert, and considered it his duty to turn out the guard, if only to a jackal or wolf, should any of the latter, as they often did, attempt to come through.

The defence works had advanced so far now that most of the garrison had thorough confidence in being able to repel any attack the rebels in the district might make on the position. Besides the earthworks and bush fences, twelve dynamite mines had been laid to command positions where an attacking force could get cover to concentrate before charging. These mines were attached by overhead wires to each fort and operated by an electric battery, used for blasting purposes at the mines. We were the happy possessors of three such batteries, strong enough to explode a mine several miles away and they were so arranged that one mine or all could be fired with one shock, if considered necessary. It gives me great pleasure to mention that the advent of the Cooks' coming into laager was a great piece of good fortune, for not only were they good shots and all-round men generally, but two of them, John and James, were qualified electrical engineers. To them the arrangement and setting of the mines was left, and they worked at them every day until in all they had twenty-seven placed round the laager in every available position. The system they adopted was so simple and complete that any of the men could have fired the mines as ordered without explanation.

It was considered advisable to mount guard every evening about sundown, as was done before the automatic sentry was erected, for the sake of appearances, in case any of the rebel scouts might have been about and noticed our change of programme. There was a full parade of the garrison held at the same time, and the men were then marched to their posts and the redoubts manned. As soon as it was dark the night-watch was set and the sentries recalled.

On the evening of the 4th, when the men were on parade, the sentry on the look-out reported two horsemen approaching on the Buluwayo road. They were coming along very slowly, but gradually increased their speed as they got near to the fort. They proved to be two Cape boys sent on with despatches from Mr. Duncan, the Acting Administrator in Buluwayo. Mr. Duncan's despatch was very short. He trusted we were all right, and requested me to bury all the ammunition the men could not carry and march to Buluwayo as soon as possible. The verbal message given to the despatch riders was most consoling. They had been instructed to try and get to Belingwe, and if possible to try and recognise any of the dead white men, and cover them up if they had time and an opportunity.

The boys were very well treated and petted by the men of the garrison. They got ready and started on their homeward journey at 6pm on the evening of the 5th. They had travelled mostly during the night on their way down and intended doing the same going back. By avoiding the main paths and taking across country, they hoped to be able to get in all right. Every one wished them God-speed as they started on their adventurous journey, carrying a despatch from me to the Acting Administrator at Buluwayo, describing our position and showing the advisability of our remaining in possession of Belingwe.

The following extracts are from the despatch: "We have eighteen men armed with Lee-Metfords and a good supply of ammunition for same. The rest of the men, with a few exceptions, are armed with Martini-Henry’s, the supply of ammunition for which is, at present, limited to thirty rounds per man. We are expecting the return of the two messengers we sent to Victoria at any moment, but until they return it is, of course, impossible to leave…”

The mere fact of our remaining in laager kept a large body of the rebels watching us, ready to rush for the spoil when we vacated, and equally ready to follow us up and harass us at every available opportunity which might offer itself. We were much better off in Belingwe than we should have been anywhere on our way to Buluwayo; in fact it would have been madness to have attempted to reach Buluwayo. I don't believe it would have been possible, even if all the men had been fit to march. As it was, ten of them were down with fever, which would have compelled us to carry them in very slowly. This would have rendered our march all the more difficult, and I feel certain, had we been foolish enough to move, not a man would have reached Buluwayo. In any event we could not have gone until we had news from Lyle and Luckhurst: but luckily we had not long to wait for them. They turned up about 4.30pm on the afternoon of the 6th with 3,000 rounds of Martini-Henry ammunition and a despatch from Captain Vizard, who was in command of Victoria.

The despatch-riders made the following report: That they left the Belingwe laager on the evening of the 31st of March and got about twenty-five miles on their way to Victoria, when one of their horses broke down. They off-saddled for some time and went on again about 2am the following morning and walked on to the east bank of the Lundi River, where they halted for a short time, then walked on again to Goddard's store, and from thence to Meeks, the missionary's, expecting there to get a fresh horse, but as all his horses had been sent away they had to walk the greater part of the way, reaching Victoria on the 2nd of April, where they at once handed their despatches to Captain Vizard. They left Victoria on the 3rd with four horses and 3,000 rounds of Martini-Henry ammunition. At sunset on the evening of the 5th they reached the Sand River, and off-saddled their horses to give them a rest till the moon rose. The horses were knee-haltered, and Lyle had just started to gather some firewood, when two lions made for, and scattered them. Lyle, as soon as he saw what had happened, made for the horses, and succeeded in catching two of them. These Luckhurst held, whilst Lyle again went after the other two for some distance, but did not get up to them. They had stampeded on the road back to Victoria. The lions did not give chase but hung around the spot where the other horses were; that they cooked some food and coffee, and waited until the moon rose, and then put all the ammunition on to the two remaining horses and resumed their march on foot, between 2 and 3am getting to Belingwe about 4.30 the same afternoon. The natives they met on their way were Mashona and at that time friendly.

At 5.30pm a full parade was held, and the despatches which had been forwarded by Captain Vizard, were read to the men. Those from the Administrator contained a brief account of all he knew about the uprising, its supposed cause, the efforts then being made to put it down, and concluded with congratulations to myself and the garrison of Belingwe for holding our own, giving me an entirely free hand to do what was considered best, either to hold the position or retire on any other one, until the Government were in a position to send us aid.

When the men were dismissed they cheered the two despatch-riders heartily, and praised them for the plucky manner in which they managed to get the ammunition through. The men, having now plenty of ammunition, felt more confident than ever of holding their own, and were very anxious to get out and try to have a brush with any straggling parties of the enemy who might be about, but, further than the ordinary patrols, I would not consent to any party going out to look for adventure. We all knew very well that our position was closely watched during the day from a hill called Fondoque, about one and a half miles from our laager. The camp fires of large parties could be seen at night about eight miles to the north of our position and often the ashes of a small fire were discovered at the back of one of the hills close up to the forts by the morning patrols. This proved that the scouts of the rebels were always on the prowl. My plan was to leave them alone, until they got tired of waiting for us to vacate our position, and I concluded that then they would be sure to come and try to rush us out of it. I was very much averse to small parties going more than a mile or two from the laager, in case they might get cut off by a large body of the enemy, whose favourite mode of fighting is, if possible, to surround isolated bodies with overpowering numbers and annihilate them. I often had to tell the men, when they came to me for permission to go out, that they had only to wait until the enemy got tired of watching us doing nothing, then they would have plenty to do. We could not afford to lose a man until they made their attack. When that came off we should want all our strength, and that behind the walls of the redoubts and mines, for I fully expected them to attack our position in great strength."

This rare and little known book describes in a very personal and vividly way the harrowing and nervous times endured in early 1896. In Rhodesiana Magazine No. 22 of July 1970 a short article on the Matabele Uprising 1896 Memorials by Cran Cooke, then Director of the Historical Monuments Commission, quoted Mr H.A. Cripwell, who said that a “Rhodesian Memorial Fund” was set up, meetings being on the 12th and 27th of October 1896 in Bulawayo and Salisbury (now Harare) to provide general and personal memorials to those killed or who died and to provide relief for those wounded or destitute and to erect or extend libraries, museums and hospitals.

In the end Memorials were erected at four points in the outside districts of Matabeland and can be identified by the words “Rhodesia Memorial Fund” carved in the base. They are Pongo (National Monument No. 33) Filabusi (No. 56) Mambo (No. 57) and Fort Rixon (no. 58) However, Mr Cripwell did not know if they were publically unveiled and, if so, on what date.

Acknowledgements

P. Baxter. www.peterbaxterafrica.com

F.C. Selous. Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia. Rowland Ward & Co, London. 1896

P.S. Garlake. Pioneer forts in Rhodesia 1890 – 1897. Rhodesiana No 12, September 1965

Major D. Tyrie Laing. The Matabele Rebellion, 1896: with the Belingwe Field Force. Dean & Son, London. 1897

C. Cooke. Memorials: The Matabele Rebellion, 1896. Rhodesiana Magazine No. 22 July 1970

When to visit:

All year around

Fee:

Entrance free

Province: