Manyanga (formerly Ntaba zika Mambo) Monument ruins

I am advised by a prominent local historian that any potential visitors need to be VERY aware of local sensitivities when visiting the area which is a highly politicised place with competing groups fighting for control and even a visiting NMMZ inspection team being stoned by local people. This article is more about providing information about the site and not about providing a guide for visitors.

From Bulawayo take Robert Mugabe Way towards Joshua Mqabuko Nkomo International Airport. Distances are from the airport turnoff. Drive 47.4 KM through Queens Mine and Turk Mine to the Inyathi (formerly Inyati) turnoff. Turn right, at 52.3 KM reach Inyathi and follow the road left. At 53.7 KM cross the Inkwinkwisi river and at 55.5 KM turn left on Inyathi Mission road which is an untarred local Council road and head north. At 56.3 KM pass Inyathi Mission on your left and continue on that road crossing the first Longwe river tributary at 73.3 KM.

At 80.2 KM pass the second Longwe river tributary, then some villages on the right-hand side of the road and at approximately 81.3 KM on the left is the Mambo Rebellion Memorial to those killed in the battle of Ntaba zika Mambo and the West brothers. The Memorial was originally sited close to West’s store on the old Hunter’s road, but when the road moved north to its present location in the 1960’s the Memorial was re-sited in its present position.

At this point you are approximately two kilometres north of the Mambo hills. Continue on the untarred road and at 86.7 KM turn right onto a track which leads to the old Meikles Ranch homestead (now Mambo Ranch) As this is private property request permission to visit the battle site; visits to the Manyanga Monument ruins are generally not permitted as there are local sensitivities associated with it.

Continue east on the track past the homestead and past the handling facilities/cattle kraals/dip directly towards the kopjes and park at their base. The closest and most northern hill with the Manyanga Monument ruin should be considered out of bounds but walk east along the foot path at its base for a few hundred metres and then the path turns south and crosses a tiny stream and you enter an open area enclosed by hills to your north, east and west with a small dam.

Directly east towards the Nsangu river is Robertson’s Kopje.

Hall and Neal in their 1902 book Ancient Ruins of Rhodesia, say the Manyanga Monument overlooks the old Hunter’s road 550 metres to the north and includes views of the nearby M’Telegewa, Thabas I’hau and Longwe Monument ruins from its summit.

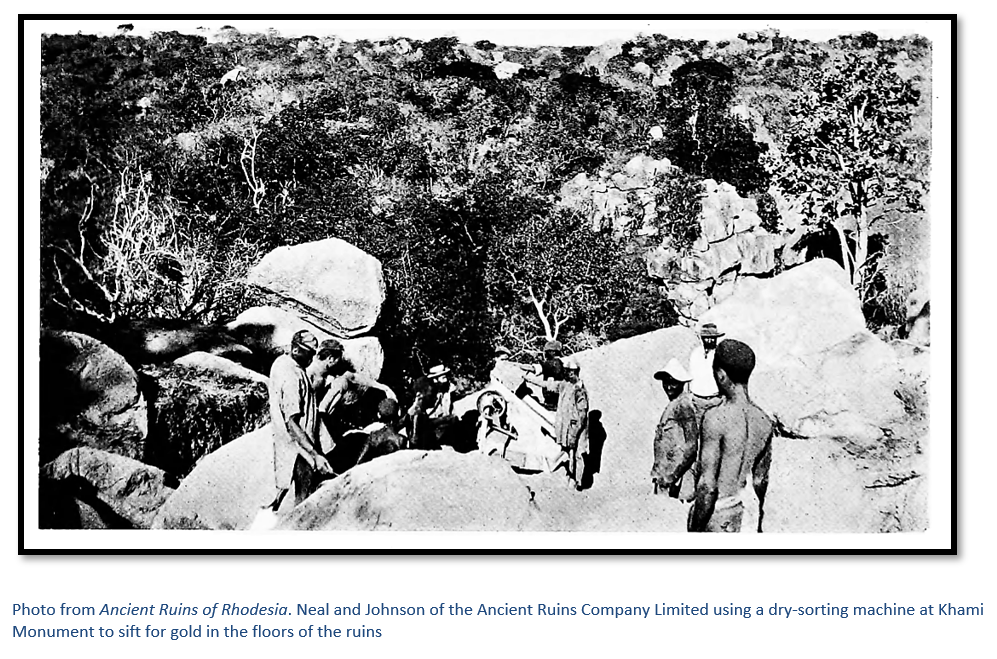

The dry-stone buildings of Manyanga Monument ruins have been little described in the literature; even C.K. Cooke, the Director of The Historical Monuments Commission in his booklet on Ancient Ruins of Rhodesia included Khami, Danan’ombe (formerly Dhlo Dhlo) Zinjanja, (formerly Regina) and Naletale, but excluded Manyanga. Although this site is considered of great importance from the archaeological point of view, as far as I know it has never been comprehensively excavated; although it is a National Monument; but sadly was subject to the destruction of the Ancient Ruins Company whose operations only ceased in 1900.

To set the Manyanga Monument site in context I have included a summary of the various cultural periods that have been identified, but readers should understand the dates given are still very tentative and this is followed by some historical text.

Approximate dates | |

Mapungubwe state | 1070 - 1220 |

Zimbabwe state | 1220 – 1450 |

Mutapa state | 1450 – 1900 |

Torwa or Butua state | 1450 – 1683 |

Rozvi state | 1684 – 1834 |

AmaNdebele rule | 1838 – 1893 |

BSA Company rule | 1890 – 1923 |

Colony of Southern Rhodesia | 1923 – 1980 |

World War II | 1939 – 1945 |

Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland | 1953 – 1963 |

Rhodesia under UDI | 1965 – 1979 |

Zimbabwe-Rhodesia | June-Dec 1979 |

Zimbabwe | 1980 – present |

Zimbabwe Cultural Periods

Zimbabwe’s recent history can be summarised into the following periods:

- The Mapungubwe state (AD 1070-1220), whose capital was at Mapungubwe Hill, south of the confluence of the Shashi and Limpopo Rivers and represents the earliest appearance of the Zimbabwe Culture with the evidence of Indian glass beads as an indication of the international trade through the East African coast (Huffman 2000)

- The downfall of the Mapungubwe state is said to have overlap with the development of the Zimbabwe state (AD 1220-1450) centred on Great Zimbabwe with some authors, such as Huffman, suggesting the old elite simply transferred their power from Mapungubwe to Great Zimbabwe, although others say there is little evidence from the archaeological record to suggest such a connection. Great Zimbabwe is characterised by the dry stone-walling seen at the Hill Complex, the Great Enclosure and the Valley Enclosures, as well as many hundreds of other smaller sites scattered throughout Zimbabwe, Botswana and South Africa. (Summers 1971; Garlake 1973). Pole and dhaka huts were built within the enclosures for the elite at Great Zimbabwe, while the rest of the community lived outside.The activities that supported this society included cattle herding, local and international trade, gold mining, metal working, farming and hunting. Pikirayi (2006) has argued that the Great Zimbabwe did not ‘collapse’ but went into a period of decline brought about by environmental stress as the local natural resources struggled through natural drought and over-grazing of cattle. The decline of Great Zimbabwe, during the mid-fifteenth century, was followed by the rise of two separate successor states: the Mutapa and Torwa or Butua states.

- The Mutapa state (AD 1450-1900) was based in northern Zimbabwe and our knowledge of it is quite extensive through the written descriptions of Portuguese writers. Whether the same elite populated the settlements of the Mutapa state, or a new elite arose which took advantage of the decline at Great Zimbabwe to establish a rival state, is not so clear. The rich agricultural lands and the gold mines of northern Zimbabwe certainly came to the attention of Swahili traders and then attracted the Portuguese. The movement of trade routes from the Save River north to the Zambezi River may also have contributed to the downfall of the Zimbabwe state.

- The Torwa or Butua state (AD 1450-1683) with its capital at Khami, developed in present-day Matabeleland, north-eastern Botswana and Limpopo whilst the Mutapa state was developing in the northern parts of Zimbabwe. Antonio Fernandes, an early Portuguese explorer, refers to the gold mines and power of the Butua state which he said equalled that of the Mutapa state. Khami was established as a new centre of power and traded directly with the Portuguese via Ingombe Ilede on the Zambezi River. However, a Portuguese writer, Fr Joao dos Santos (Mudenge 1974) said that the Torwa placed a greater value on their cattle than gold and had little interest in gold-mining. A civil war between the ruling Mambo and his brother in which the brother enlisted the help of the Portuguese in the dispute brought about the destruction of Khami around 1650 and considerably weakened the state.

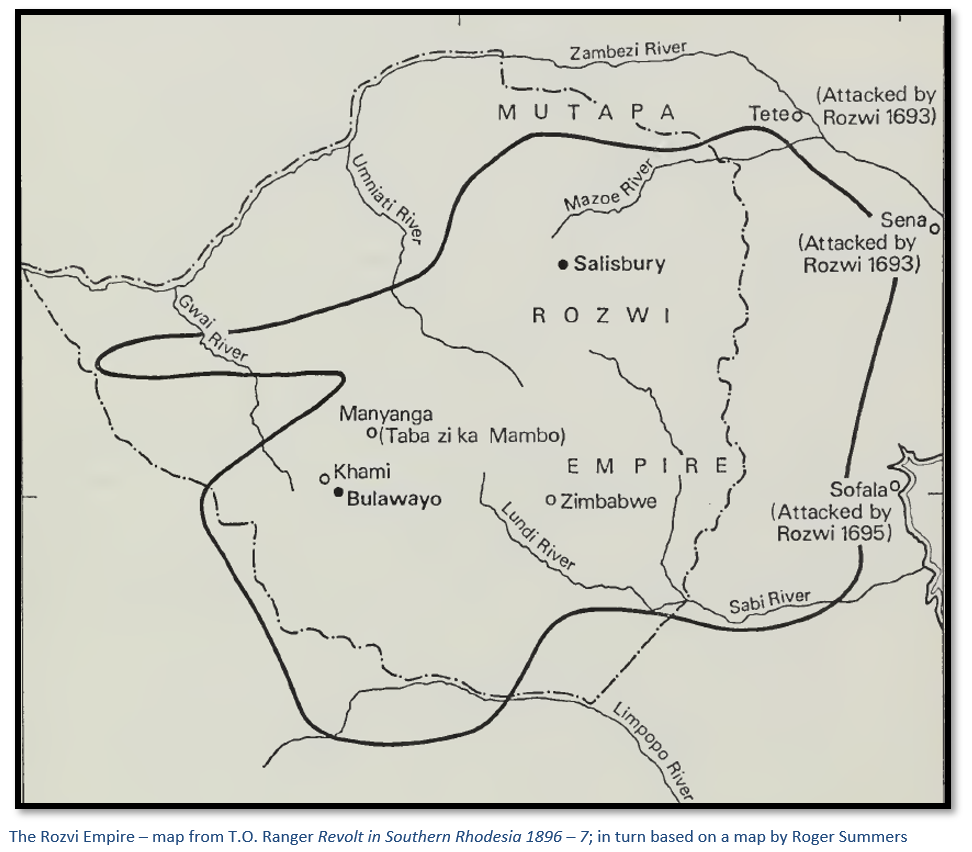

- These events may have precipitated the takeover of the destabilised Torwa state by the Rozvi Changamire (AD 1684-1834) and the move of its capital from Khami to Danan’ombe and its subsidiary centres of Naletale, Zinjanja and Manyanga. The Rozvi state flourished until its collapse as a result of constant invasions by Nguni groups fleeing the Mfecane wars in Zululand about which more is given below.

The end of the Rozvi and the impact on Manyanga Monument

Mfecane (meaning ‘crushing‘) was a period of widespread chaos and warfare among African tribes that took place between around 1815 and 1840. In the late 18th century, populations had increased greatly in Zululand following the Portuguese introduction of maize into Mozambique, but declining rainfall and a ten-year drought in the early 19th century set off a competition for land and water resources.

The Mfecane term is widely used to cover the wars and disturbances following the rise of the Zulu nation under Chaka when whole tribes, or smaller groupings under individual leaders fled precipitately from Zululand and the surrounding area, spreading devastation and chaos wherever they went.

The major forces in Zululand were the Ndwandwe tribe, whose chief Zwide killed Mashobane, the leader of a small tribe called the Khumalo, whose wife Nompetu and small son Mzilikazi fled to the sanctuary of his main rival Chaka. After clashing in 1818 with Chaka and suffering defeat, Zwide sent his general Shosangane and army in 1819 in a further attempt to crush Chaka. The Ndwandwe army suffered a crushing defeat. Zwide fled to the Eastern Transvaal (now Mpumalanga) and played no further part in history, but three groups of his former followers fled as refugees to the north.

Nxaba, the weakest of the three, went up the coast to the area inland of Sofala and conquered the Ndawu tribe. Zwangendaba, chief of the Jele tribe, originally under the protection of Zwide, gathered followers as he pushed Nxaba up the coast before turning inland. The stone walls of Great Zimbabwe and Ziwa and Nyahokwe (formerly Van Niekerk ruins) proved no obstacle for his forces and the lands of the Karanga people were ravaged.

But behind Zwangendaba came a third group of refugees under Shosangane. After pausing in the inland area of Maputo, in 1828 Shosangane fought with Chaka’s forces again before retreating; this time turning inland at Inhassoro and travelling up the Save River (formerly the Sabi) where in the middle reaches about 1830 Shosangane encountered Zwangendaba and his followers who were overwhelmed after a prolonged battle.

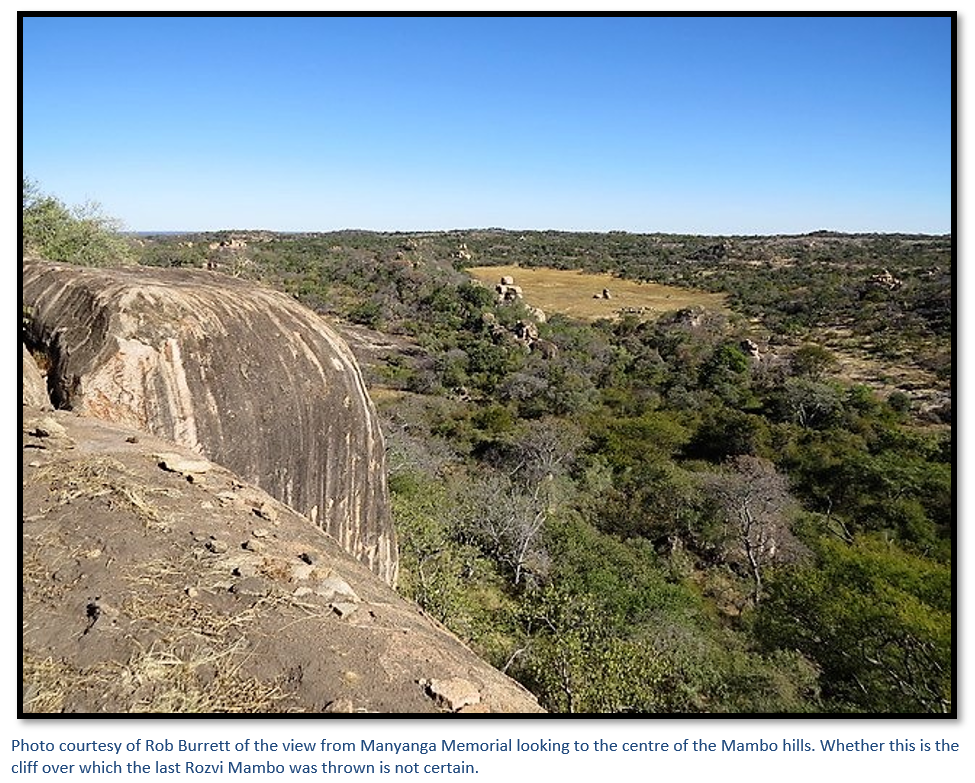

Zwangendaba retreated inland into central Zimbabwe and took his revenge on the Rozvi Mambo at Danan’ombe, Rupengo Chirisamaru (see the article in www.zimfieldguide.com under Matabeleland South province) Danan’ombe was overrun and destroyed, the Mambo Chirisamaru had left for Manyanga (formerly Ntaba zika Mambo) fifty-five kilometres northwest of Danan’ombe and his brother had fled to Khami. Zwangendaba’s army caught the last of the Rozvi Mambo at Manyanga, according to Posselt, allegedly flaying him alive and throwing him over the granite overhang of the kopje.

Remnants of the Rozvi made their way northwest into the area of the modern-day Hwange National Park where they constructed the Bumbusi Monument ruins - a dry-stone circular walled enclosure on the summit of a low granite dome, after conquering the few tribespeople in the area. But this tranquil situation was not to last long as further south Mzilikazi and the amaNdebele had been defeated firstly at the battle of Vegkop in 1837 by Hendrik Potgieter and then again in their own refuge in the Marico Valley by both the Boers and the Zulus. They left in full flight for the north pursued by the Boers before travelling through modern-day Botswana to the Makgadikgadi Pans before turning east into the same modern-day Hwange National Park and overwhelming the local Rozvi Chief Hwange Rusambani.

The last Mambo at Khami, Jiri Mutinhima fled west and with the final subjection of the Rozvi came amaNdebele rule. However, remnants of both the Rozvi and Ngoni stayed; Roger Summers states that Carl Mauch, the second European visitor to Great Zimbabwe after Adam Renders, reported the last group of Rozvi left Great Zimbabwe about 1840 and that some Ngoni remained at Danan’ombe until the 1890’s.

Manyanga Monument ruins

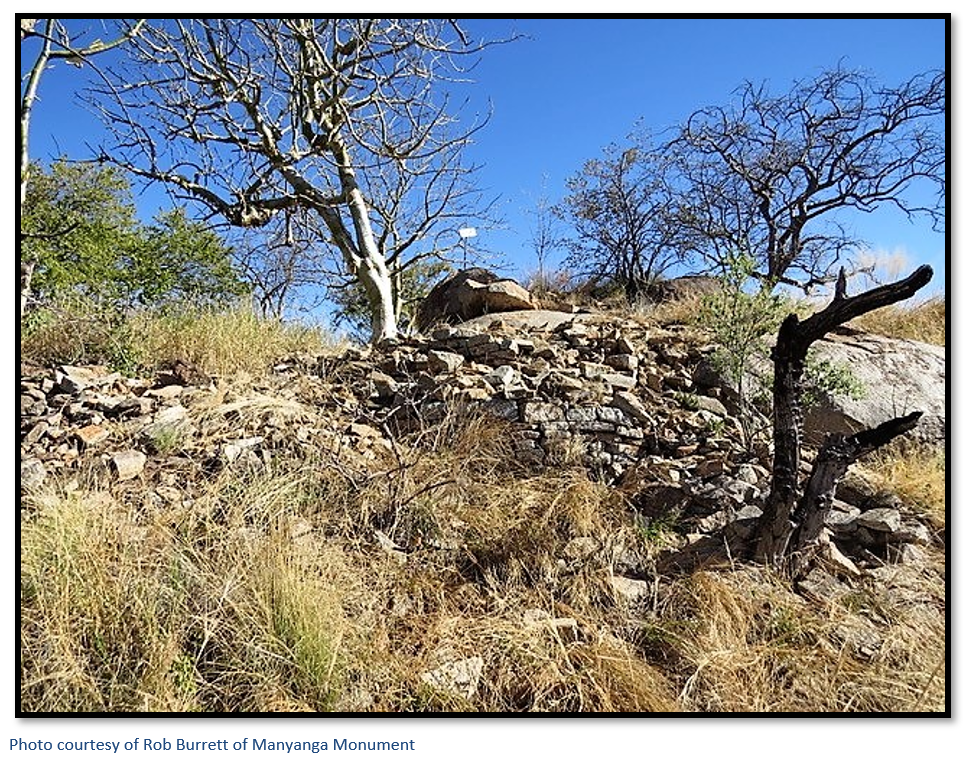

The site was briefly described by K.S.R. Robinson, Inspector of Monuments (1947 – 1964) and declared a National Monument in 1952 and consists of a large granite hill on the northern edge of the Mambo Hills whose summit is sprinkled with huge granite rocks forming cliffs. Over the whole area of the hill top may be seen stone platforms which formerly supported huts, and a little walling of the Khami ruins type. Unfortunately, much damage was done here in the early days by the Ancient Ruins Company looking for gold and the damaging results of this may be clearly seen, as nearly every hut site has been dug into, and there is no doubt that much walling has been destroyed. In spite of this, the site is of great interest and may yet yield important results when properly investigated.

That the hill has a long history is certain. Robinson’s research showed that it had been occupied continuously from the Stone Age until its use in recent times for ritual prayer activities. It is supposed to have been occupied by the last of the Rozwi Mambos, Chirisamaru, who refused to retreat before Zwangendaba’s Ngoni, but sat on his throne saying, “Kingship is a stone and cannot be removed” before being skinned alive by Zwangendaba’s Ngoni (see 'Fact and Fiction', by F.W.T. Posselt). There seems to be good reason for believing that the hill was occupied prior to the Rozwi period but there can be no certainty on this point until further excavations have taken place.

Roughly in the centre of the hill top is an enclosure formed by large rocks and some revetting. This is probably the place where formerly rain-making ceremonies took place before AmaNdebele times, possibly a relic of the Rozwi period.

Roger Summers describes Manyanga as a Type 4 ruin in which Robinson carried out some field archaeology, although I cannot find any published information. In addition, he states that there is plenty of evidence from archaeology to show that Type 4 buildings were occupied by the Rozvi Mambo’s or subordinate chiefs.

Hall and Neal’s Ancient Ruins of Rhodesia published in 1902 provides the first and most comprehensive description of this site and the nearest associated sites at M’Telegewa (twenty kilometres north at the junction of the Shangani and Longwe Rivers) Thabas I’hau (twenty-six kilometres northeast on the eastern side of the Shangani and Longwe (seventeen kilometres north on the western bank of the Longwe River and three hundred metres from its junction with the Shangani River.

They describe the ruins as massive with a gradual backwards slope in the inside and outside of the main walls “the batter” which are built in curved lines on a granite foundation and they describe the stone workmanship as of the first period (Summers’ Type 3 with later additions) occupying an area of sixty metres by twenty-five metres. The building is built the summit of the kopje but takes in the contours of the hill with the walls using natural boulders as part of the structure.

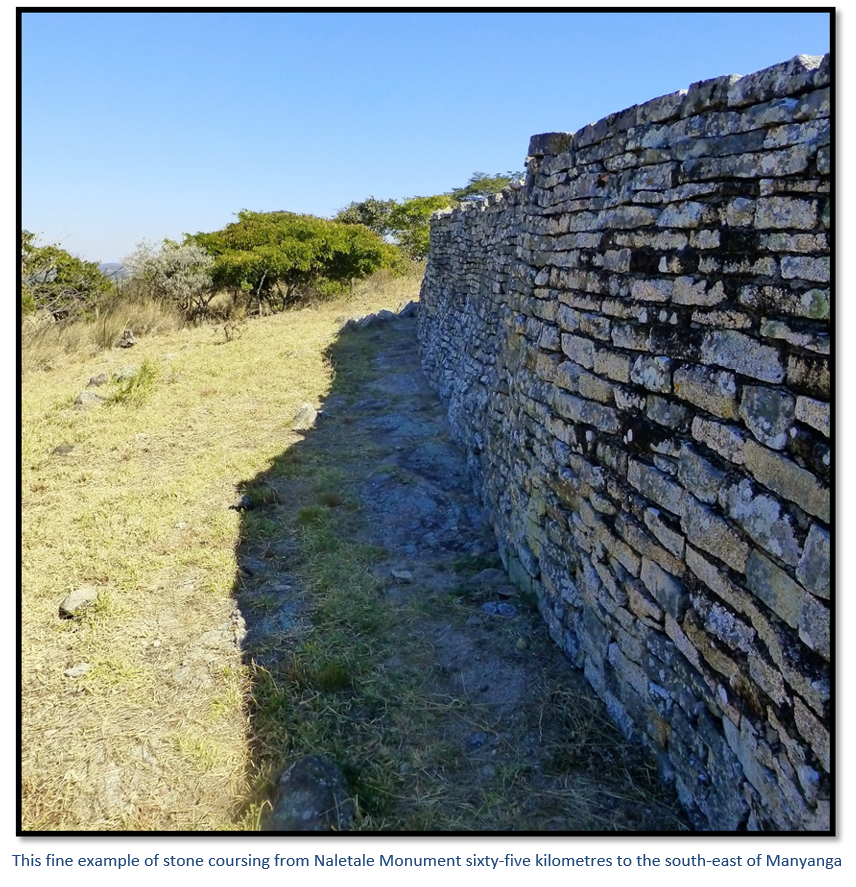

The main walls are well-built (modern archaeologists call R-style) with very straight stone coursing, but they describe the later additions to the walls as of inferior workmanship (Q-style) No wall ornamentation such as exists at Naletale or Danan’ombe was visible; ironically they attribute this to the “vandalism” of later occupiers and amateur explorers and natural causes; ignoring the fact that the Ancient Ruins Company itself caused enormous damage.

Even before Neal and Johnson’s excavations began the entrances had become ruined and unfortunately, owing to the topographical difficulties, no general plan was made of the enclosure. However they describe only one accessible approach to Manyanga on the south-east side; the main entrance was protected on the right-hand side by huge six metre boulders and has a stone wall 1.5 metres high to form a passage over six metres long into the enclosure. Another wall runs parallel on the left-hand side, the passage itself being a uniform 80 cms wide and floored with granite blocks cemented over in dhaka.

The south-west corner of Manyanga has an open space with cemented dhaka floor approached by three steps down from the main structure with a precipice on one side and 3.6-metre wall on the north east. The steps lead onto another flight of twelve steps which ascend to a 2.4-metre wide dhaka platform at the summit with a base of 4.3-metres built as a solid cone.

Inside the eastern wall are lower interior walls inside an enclosure from which Hall and Johnson dug a pit 3.7 metres wide and from 90 cms – 2.7 metres deep and found ashes, bones, broken pottery and portions of gold and copper crucibles and blow-pipes (tuyeres – for blowing air into a smelter) all covered over by a cemented dhaka floor. Inside the same enclosure were described two small compartments each 2.4 metres wide connected by steps which were probably hut bases. On all other sides of the kopje there are sheer drops varying from fifteen to over twenty metres.

Again somewhat ironically, Hall and Neal state that: “portions of the walls have, within the last five years, been destroyed in a most wilful manner by amateur explorers possessed of the idea that the walls contained treasure.” This after they describe the excavations made within the structure itself and that at the base of the kopje were found by the Ancient Ruins Company of which Neal played an important role: “huge debris heaps made of ashes, bones, broken pottery etc., thrown over the edge, and to this day, with a dry separator, can be obtained portions of gold ornaments, gold pellets and tacks, copper and pottery, both ancient and modern, of all periods of occupation.”

This is after having described Manyanga as important, evidently being the centre of a large gold-smelting operation “as portions of many thousands of gold crucibles and blow-pies of the very oldest pattern, with gold still in the flux, were found under the present floors. There are indubitable evidences that a very great population resided at or near these ruins.”

Huffman, Robinson and others have argued that Zimbabwe Society was divided into the elite and the non-elite; the former living within stone walls and the latter living outside them, with the elites distributing the wealth, political power and social status amongst themselves.

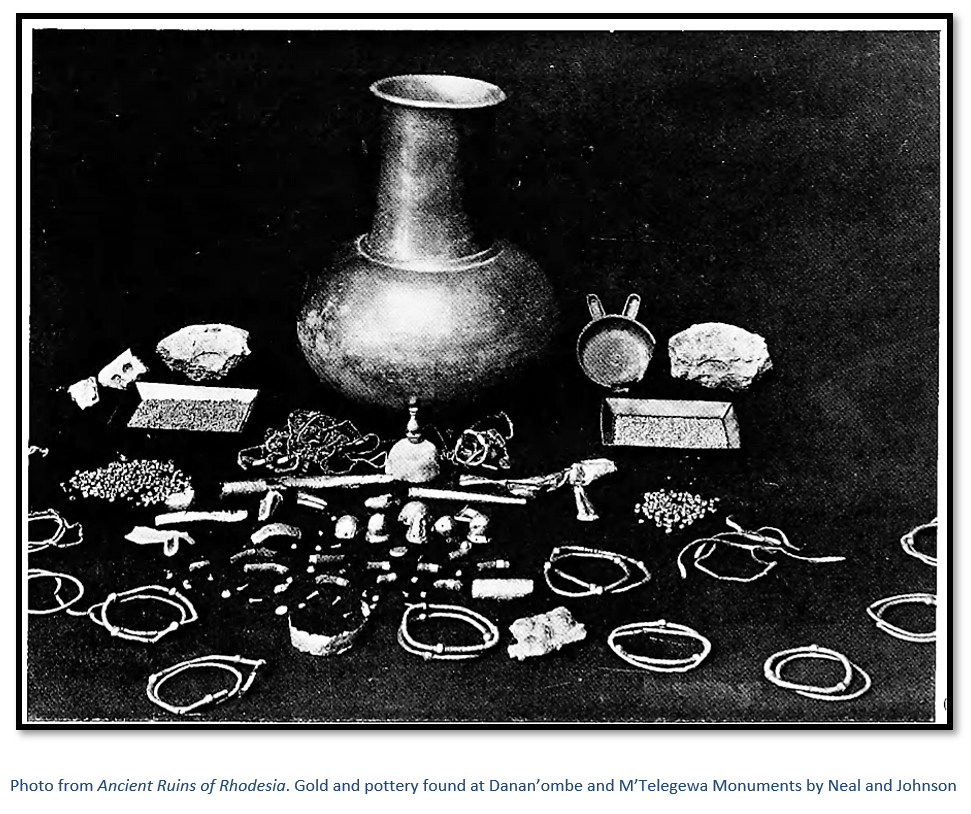

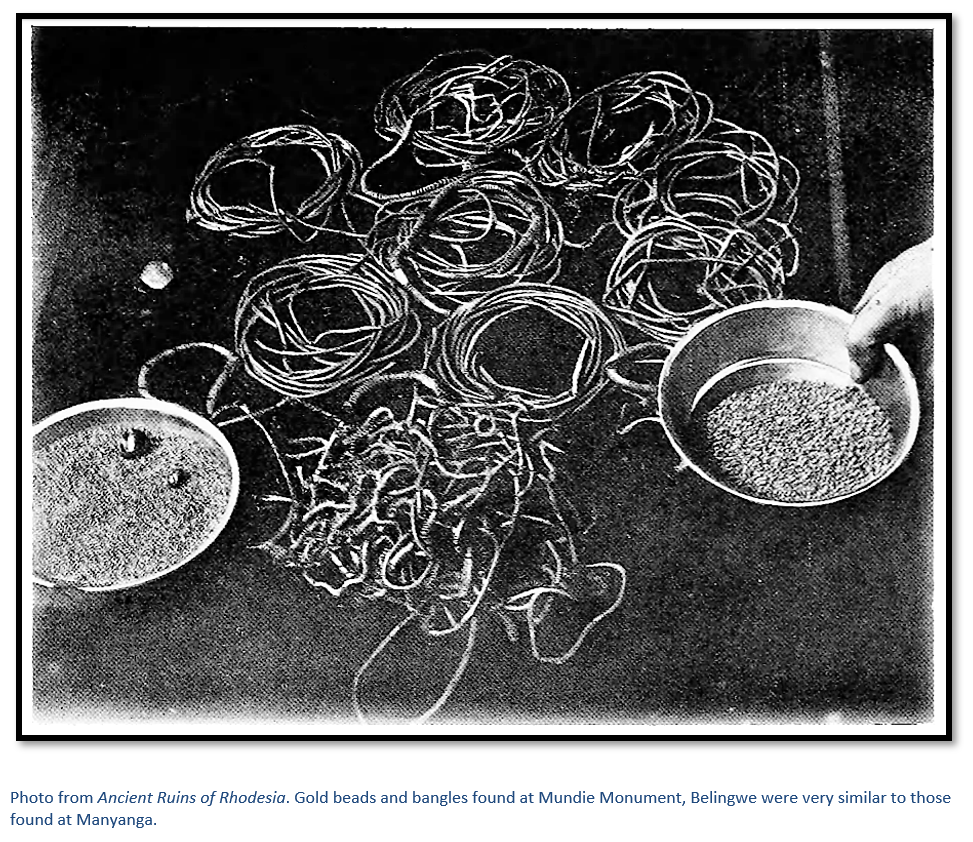

Hall and Neal reported that most gold ornaments found by Neal and Johnson of the Ancient Ruins Company Limited were in the form of gold beads. Every one of forty burials that were located within the ruins of various dry-stone monuments had a necklace of gold beads which varied in size and weight but were all made of pure gold. The largest weighed two ounces five pennyweights (almost 70 grams) down to microscopic size and some beads were engraved. However bangles of solid gold from 9 to 187 grams were also quite commonly found, some of sold metal and others manufactured from twisted gold wire. Over 2,000 ounces (>62 kilograms) of gold ornaments were discovered in the various ruins, mostly in Matabeleland; sadly, all would have been smelted down and their value to archaeology lost forever.

Burials were always found stretched out on either their left or right side under the original dhaka floors or within the next two floor levels; each being separated by approximately eighteen inches (46 cm) of solid dhaka fill. A reported feature was that lower and earlier burials had gold ornaments; later burials had ornaments of copper and iron and glass beads.

Current controversy at Manyanga as a site of cultural heritage

This site is considered of great importance from both the archaeological point of view and cultural points of view. Manyanga Munyaradzi makes the compelling point that the current controversy at Manyanga Monument comes from the National Monuments Act and the National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe (NMMZ) recognising the tangible aspects of preservation but coming into conflict with the intangible aspects of cultural heritage. These intangible aspects are made up of social practices, rituals and festivals by individuals and groups which have long been practised at current archaeological sites as part of the local people’s cultural heritage.

The activities of ritual prayer groups at Manyanga have included the construction of a hut for ritual praying and the planned construction of a granary to store grain for thanksgiving ceremonies; this brings them into direct controversy with NMMZ as Zimbabwe’s National Museums and Monuments Act does not recognize the intangible aspects of cultural heritage.

Thanks

Thanks to Rob Burrett for the photographs as visiting Manyanga Monument is now largely off-limits and to Rod Tourle for providing directions to the site which I have not yet visited.

Acknowledgements

Garlake, P. S. Great Zimbabwe. London: Thames and Hudson. 1973

Hall, RN and Neal, WG. The Ancient Ruins of Rhodesia. Methuen & Co, London 1902

Huffman, TN. Mapungubwe and the origins of the Zimbabwe Culture. Leslie, M. and Maggs, T. (eds), African Naissance: The Limpopo Valley 1000 Years Ago, The South African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series 8: 14–29. 2000

Mudenge, SI. A Political history of Munhumutapa. Harare: Zimbabwe Publishing House. 1988

Munyaradzi, M. Intangible Cultural Heritage and the empowerment of local Communities: Manyanga (Intaba Zika Mambo) revisited.

Pikirayi, I. The demise of Great Zimbabwe, AD 1420–1550: an environmental

reappraisal. A. Green and R. Leech (eds) Cities in the World, 1500–2000. The Society for

Post-Medieval Archaeology Monograph 3, Leeds, UK: Maney Publishing: 31–47. 2006

Posselt, FWT. Fact and Fiction. A Short Account of the Natives of Southern Rhodesia. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1978

Ranger, TO. Revolt in Southern Rhodesia 1896-7. Heinemann London 1967

Summers, R. Ancient Ruins and Vanished Civilizations of Southern Africa. T.V. Bulpin, Cape Town 1971