Home >

Matabeleland North >

James Dawson’s account of finding the remains of Allan Wilson and his patrol

James Dawson’s account of finding the remains of Allan Wilson and his patrol

National Monument No.:

13

How to get here:

The amaNdebele name for the Shangani Memorial site is Pupu. The GPS location is 18°46´05"S 28°07´33"E.

The final stages of the 1893 occupation of Matabeleland

On 29 October 1893 King Lobengula sent a message to James Fairbairn and William Filmer Usher, the last remaining whites at Bulawayo,[1] saying, “Keep up your heart, do not be afraid, I will look after you. The enemy is in the east.” No harm did come to either of them. The next day he requested wagons from Fairbairn and cattle from Usher.

His last message to them came from the iNduna Sehuluhulu on 1 November, the day of the battle of Bembesi (Egodade) saying, “stay where you are: you need not be afraid of my people as you are not personally responsible for the row; and if you get killed it will be by your own colour, as they will very likely also kill me.”[2]

James Dawson had written to John Smith Moffat, Assistant Commissioner for the Bechuanaland Protectorate, on 9 September saying, “I am firmly of the opinion that Loben does not want to fight and that he will not do so unless forced in self-defence…holding the opinion of which I do of Loben’s intentions I cannot see where the probability of hostilities occurring becomes apparent, unless, of course…the Third Factor, i.e. the Company, is so powerful as to have its own way in case they wish to see the thing out.”[3]

Jameson’s reply, when he saw the letter was, “Dawson’s information, living at Bulawayo with the King, is of no value – the King being a master of deceit and his word utterly unreliable.”[4]

Jameson had, of course, after the ‘Victoria incident’ of 18 July 1893, decided the occupation of Matabeleland and the ousting of the King, was inevitable.

On 7 November soon after taking Bulawayo, Dr Jameson wrote to Lobengula, who had left his capital, appealing to him to surrender, “Now to stop this useless slaughter you must at once come to see me at Bulawayo, when I will guarantee that your life will be safe and that you will be kindly treated.”

Messengers returned saying the King would come in, but he did not, and the news was that Lobengula had continued his flight to northern Matabeleland and it appeared he wanted to get his women and cattle over the Zambesi river.

All thought it essential for the King to be captured if the amaNdebele were to surrender. High Commissioner Loch in Cape Town thought that Lobengula should then be sent into exile in the Cape, as was done with Langalibalele.[5]

A large force is sent to capture the King

A force under Major Forbes, who had commanded the Salisbury and Victoria Columns, consisting of ninety men from the Salisbury Column, sixty from the Victoria Column, ninety from the Bechuanaland Border Police (BBP) and two hundred natives under Lieut Brabant with four Maxims and a seven-pounder was assembled.

The main amaNdebele force was thought to be at Shiloh and the Forbes’ plan was to march to Emhlangeni, near Inyati, and approach Shiloh from the north, the obvious route for the amaNdebele to retreat. The force left Bulawayo on 14 November and were at Emhlangeni on the 16 November. There they learnt from captives that Lobengula was enroute to the Shangani river, but Forbes did not have rations to pursue him.

Dr Jameson despatched two hundred dismounted men to Shiloh with ten wagons of rations. Forbes chose three hundred men, four wagons, four Maxims and a Hotchkiss gun and left Shiloh on 25 November. But an exceptionally heavy rainy season made progress very slow with the wagons getting continuously bogged down and in three days they travelled just seventeen miles. So, Forbes sent back all the dismounted men and the wagons to Emhlangeni.

iNduna Gambo’s account[6]

Col C.L. Carbutt visited Gambo’s kraal in 1915 and was given the following details by Gambo himself.

Gambo told him the amaNdebele knew that Forbes’ troops coming after Lobengula would follow the wagon tracks past Shiloh up to the Gwampa river and Gambo’s impi had orders to stay behind as rearguard. In order to speed up Lobengula’s progress some of the wagons were left behind and burnt between the Bubi and Gwampa rivers as well as Lobengula’s bath chair.[7] However Gambo’s impi and Forbes’ Column did not meet and Forbes’ was unaware of the impi on his flank.

When Forbes’ Column reached the Shangani, they laagered about 200 yards south of the river at what became known as Forbes’ drift with an area of open vlei between them and the river. Shortly after Gambo’s impi arrived at the same spot, they were probably now following the tracks of the Maxim gun’s galloping carriages. Then Gambo himself rode forward on a white horse across the open vlei to the Shangani to see if it was fordable.

Captain A.C. Pyke, who lost an arm, said although they saw a native on a white horse, they did not open fire. Gambo’s impi subsequently took part in the attacks on Forbes’ Column as they retreated back towards Inyati.

Allan Wilson’s patrol

Major Allan Wilson and his men were part of Forbes’ force[8] which left the royal kraal at Bulawayo in pursuit of Lobengula, King of the amaNdebele.[9] It became known that the King had crossed the Shangani River which was low at the time. On the 3 December 1893, a small, mounted patrol consisting of twelve members of the Victoria Rangers joined by some of Major Wilson’s officers crossed the river about 5pm with orders to return by about 6:30pm in the early evening. But it was not until 11pm that Captain Napier rode back into camp when Forbes learnt that Wilson wanted him to cross the Shangani at 4am next day and attack Lobengula’s wagons at daylight.

The purpose of the patrol was to conduct a reconnaissance preparatory to capturing King Lobengula.[10] The patrol followed the King’s wagon tracks for 6 miles (9 – 10 kilometres) and came upon his two wagons in the dark. The wagons were surrounded by a series of scherms[11] that were filled with amaNdebele warriors, but they offered no resistance, possibly because they did not know the strength of the patrol, or believed they were the advance guard of a much larger force.[12] But the King was not present, and Wilson made the decision to wait in the bush for dawn next day in the hope that reinforcements would arrive, and the King might then be captured. But the great irony was that hours before Wilson and his men arrived, Lobengula had abandoned his wagons and ridden away on horseback up the valley of the Pupu towards the Kano river.

In the late evening Wilson ordered a three-man group to ride back to the main force and request reinforcements from Major Forbes.[13] The reinforcements who reached Wilson and his party comprised Captain Henry Borrow accompanied by twenty mounted men from B Troop.[14] The heavy rain persisted, and at dawn Wilson decided to make another attempt to capture the King.

At daylight on the 4 December 1893, they returned to the King’s wagons. This time the amaNdebele opened fire on them and the patrol retired about 640 metres (700 yards) Wilson sent a second group of three who broke out and managed to swim the now flooding river in a bid to collect additional reinforcements from the main Column.[15] However, Major Forbes was himself involved in a skirmish near the southern bank with Mjaan’s (Mtshane) Imbizo Regiment who attacked on both flanks from the bush.[16]

Lobengula’s bodyguard then surrounded and attacked the Wilson’s patrol, who remained isolated, and severe fighting lasted for several hours.[17] The patrol took cover behind the dead bodies of their horses, the wounded reloading and passing their rifles to their uninjured comrades and fighting on, but one by one the men fell until finally all were dead. The position of the bodies showed they had stood shoulder to shoulder throughout the fight. One, whose identity was never discovered, held the amaNdebele at bay for a long time when all his comrades were dead. At last, he was shot down and the amaNdebele said there were six or seven wounds on his body.

The amaNdebele name for the Shangani Memorial site is Pupu. The GPS location is 18°46´05"S 28°07´33"E.

For additional information see the article Three oral history statements made in 1937 by amaNdebele warriors present at the killing of Allan Wilson and thirty-three other Europeans on 4 December 1893 at the Shangani River under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

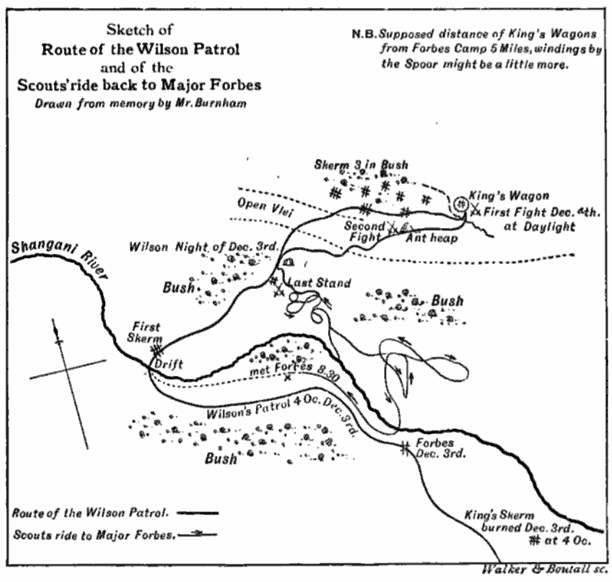

Wikipedia: Frederick Burnham’s sketch map of Wilson’s route north of the Shangani river

James Dawson’s account from Rhodesian Genesis[18]

No definite news had come as to the fate of Wilson’s party, but people feared the worst from the information given by Major Forbes’s men on their return. “We had for some time been looking forward to the advance of the column from Inyati which was being delayed by the rains and were anxious. Persistent rumours keep coming from various sources that there were some survivors of Wilson’s patrol still living and wandering about, naturally the relations of all the men were hoping that the fortunate ones were those in whom they were interested and were urging that something should be done to ascertain the truth.

The object of the force lying at Inyati was to get in touch with the King and induce him to come to terms, as well as to recover the remains of Wilson's party and set all doubts at rest as to their fate.

On the night of 3 February 1894, I had been in bed sometime in my house at Bulawayo when I heard someone coming into the yard at the back and towards the door of the outer room, the top half of which was open. “Are you asleep, Jimmy?” came a voice, to which I answered, “Yes, come in.” I knew the voice, and in came Major [Maurice] Heany.

I lit the candle and he sat down on the end of the bed. He told me he had just come from Dr Jameson and said they had been discussing a hazy proposal of two men to go after Loben and try to treat with him. Now I knew those two men and at once saw that there was likely to be a lot of parleying and bargaining before they would make a start and the matter was urgent. After the Major had talked for some time while I had been thinking, I said, “Look here, Major, tell the Doctor that I will go.” He at once said, “That's what I hoped you would say.” Then I asked him to tell the Doctor, I would see him in the morning.

Next morning early, I saw the Doctor. I told him my plans and at once proceeded to get ready. In the first place I secured a Cape boy whom I knew, to drive the Scotch cart which was to be the baggage carrier. Next, I looked up James (Paddy) Reilly and induced him to accompany me.

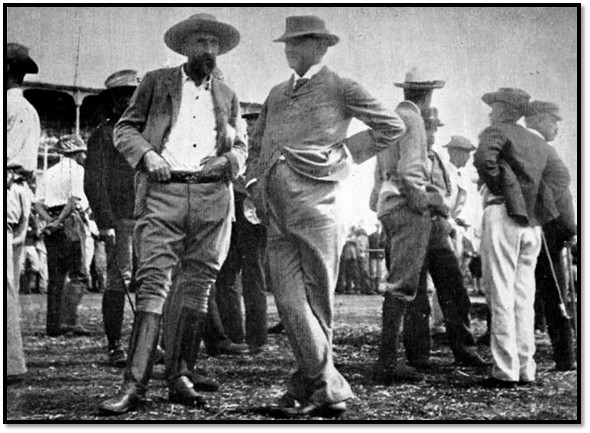

NAZ: James Dawson with Rhodes, Bulawayo 1896

When thinking over my plans the previous night, Sekombo came to my mind, as having one day asked me why I did not go and help my friend the King. I had answered that I would go if he went along. I understood him to say that he would, so the same afternoon, the 4th, we started for Sekombo’s kraal[19] and arrived there in the evening. All that night was spent in trying to persuade him to come along with us, but it was no use as his principal wife, a half-sister of the King’s, was against it and he tried to put difficulties in the way. In fact, he funked it. I had to devise another plan quickly and bethought me of a man named Malibamba who had been given to me as my man when I wanted him, and, as he lived at Inyati, we inspanned at daylight and made our way in that direction. On crossing the Bembesi we found the Doctor with Sir John Willoughby and Mr Knight of the Morning Post on the bank on their way to Inyati. I told the Doctor of my new plan and allowed the party to go ahead to the camp on the far side of the river while I followed later to Malimbamba’s kraal which was on the near side. The most of that night was also spent in arrangements, but at the outset I told him that he had to go along with me and look for the King. He was surprised but made little demur, and at once preceded to select several of his young men to go with us. This was a weight off my mind and in the morning, we crossed over to the camp when I told the Doctor that I was ready to start after he had given me some supplies and a few cattle to kill for food as there was no time to be wasted and I wanted as little shooting as possible.[20]

On the afternoon of the 5th [February], we started from Inyati – Reilly and I mounted - and made our way in the direction indicated by the spoor of Major Forbes’s returning column. The first night out we spent near a small kraal where we tried to get what information we could to guide us. I was lying down a little apart and Reilly had been talking to the people who had apparently given him something to think about as he came over to me and said, “Do you know that this is a damned dangerous thing we're going to do?” I asked him if he had not thought of that before and he said he had not. Then I asked him if he was still going on and he said, “Yes, if you do.” So that was settled. Next morning we went on and came on to some people in a small kraal where we were fortunate enough to get a man to come with us and show us the tracks. The rain had been falling heavily.

We went on for some days until we met two men (one a well-known witch doctor) with their hands up. Upon questioning them we were informed that the King was dead. Being assured of this, I wrote to Dr Jameson who was still at Inyati giving him the news and I said I was going to find the place where Wilson’s party were killed.[21] Before sending the messenger away Reilly said there was no need for us to go any further now as the King was dead and I said there was a chance for him to go back with the news, but I was going on. He decided to come. That afternoon[22] we got to the place on the river near which Major Forbes had his fight with the natives while waiting the return of the men who never came back and where the drift across the river was.

The river, fortunately I think, was unfordable, so we made our small camp. In the morning, a number of young men came to the opposite bank and shouted abuse and threats at us thinking that we were the first of the force which was lying at Inyati. This continued for some days until we persuaded them that we were bearers of messages of peace and got in touch with some of the older men.

At last, one morning we saw that the river had fallen a good deal and, while we were sitting at breakfast, some young men who had crossed farther down came running up to our camp. Upon seeing them I knew the river was fordable, so told our people to get ready to cross. We continued our meal while the horses were being saddled and the young men were standing looking on. Having finished and got up and greeted them, they returned the greeting civilly and then asked where we were going. I told them “to see the place where they had killed the white men.” We started, they coming along, and after a scramble in the water managed to cross.

On the side we were now on there were some big scherms with a great many young men. We approached the largest one within about 100 yards and, when we dismounted, I put my rifle against a tree and told Reilly to wait for me. Inside the enclosure there were many groups, mostly sitting round fires where cooking meat (their only food) was going on, and there was dead silence while I walked right in and, after looking round, gave them the usual greeting which a few of them returned calling me by name (Jimsolo) Then I said I wanted some of them to come and show me the place where they killed the white men. Some of them said, “we are only boys and know nothing of it.” I said, “Very well, I will go and get men to show me” and walked to my horse and mounted. We had not gone very far before a number of the young fellows came running after us saying they would go and show us. I said, “No, you are only boys, I want men,” continuing my bluff.

We went to a kraal where we found one of the headmen of Bulawayo and the chief iNduna of the Nsukamini Regiment. On telling them what I wanted, the latter volunteered to come with me.

After walking about three miles along a path, he halted and pointed ahead. We dismounted and walked about seventy yards (64 metres) when we came to an open space in the bush which was very thick all round, and then we saw a number of bones scattered about. After looking solemnly on with bared heads for a while, we set to work and collected what remained of that brave band and piled them in a heap while our people were digging a trench. It must be remembered that these remains had been lying there for a long time during a very wet season and were quite bleached.[23] We got every visible scrap together, including the skulls of all,[24] and buried them under a large Mopane tree on which I cut with knife and hatchet a cross with the legend “To brave men.” The only articles of consequence which we picked up were a watch and a ring, both of which were recognised by those interested and handed over.

After finishing this sad duty, we rode some distance farther and came to an open glade where Lobengula's last camp had been and where Wilson's party turned back on their fatal attempt to rejoin the main column. We were there told how the King had been gone some time before the party came to the spot and fired into the place. We followed the spoor for some distance beyond this, talking to the people and telling them that we had brought them peace, and persuading them to come in. We returned to our camp in the evening having had a long and trying day.

Next morning I had a message from the two headmen I have mentioned, to come to them alone at their kraal. I crossed the river, giving Reilly some excuse for leaving him. On arriving, and after the usual greeting, a dry ox hide was laid down in front of me in perfect silence. Then a skin bag, with some ceremony and still in silence, was brought forth and the contents poured out on the hide. I was told to count and found five hundred sovereigns. Then another bag was produced with the same amount, all in silence.

When I told them that there was a thousand pounds they said, “Take it, Jimsolo and plead for us with the Doctor. We are tired of war and want to be able to sleep.” I repeated to them what I had been telling them all - that the white men were also tired of strife and wanted to live in peace with the people of the country. After some more talk, I put five hundred sovereigns in each of my wallets and went back to camp. On arrival I put the wallets in my bag and, as far as I am aware, Reilly knows nothing of this matter till the present day.[25]

The following day was the big indaba when Mjaan, the chief iNduna of the King's favourite Regiment, Mgubongubo, a brother of the King, and many iNdunas and others came to talk.

Mjaan, as befitted his rank, began the talking in a most friendly vein. They were glad to hear the message we had brought them and asked us to tell “the Doctor” that they were tired of war and wanted to live in peace and wished us to tell him so, and much more to the same effect. After him the King's brother got up, and hadn't spoken long before he began telling of his narrow escape when I went down with him and two others on a mission to the High Commissioner to try and stop the invasion of the country by the whites (we knew such a mission was too late, but we were only three white men left in the country and the King's word was the only law so I had to go)

We had only got as far as Tati when we unexpectedly rode into a force coming up from the South.[26] While I was talking to the officer in command[27] my three men were taken across the river and thinking not unnaturally that they were going to be killed, the youngest made an attempt to escape and was promptly shot, while the second one was clubbed on the head and died shortly after, leaving this old man who was now talking. You can imagine how uneasy I felt not knowing but that he might blame me for what happened. Think of my relief when at last he said, “we came out of death together.”[28]

After a good deal more talking, I repeated the message I had brought. They then said, “We hear what you say and believe you, but we wish to send two of our number in with you to the Doctor as our ears to hear from him.” Of course, I agreed to this, not only so, but I told them I would come back again with their oxen and bring them food and medicine. They were greatly pleased at this and the indaba ended, and we prepared to return to Inyati.

In due time we arrived at the camp just as Dr Jameson was sending off dispatches. The men were stopped until my report was taken down by Sir John Willoughby. This done there was a meeting between the Doctor and the two “ears,” who were assured that all I had told and promised them was true. They were perfectly satisfied after the talk.

When I told the doctor that I had promised to go down again he was surprised. Anyway, I said I must go on to Bulawayo first and get some things that were required. The camp was broken up and all went back to Bulawayo. The war was over.

After staying a short time in Bulawayo, we started back again with a wagon load of grain and other necessaries. The people had been living on nothing but meat and were dying of smallpox among other things. As we made our way, we passed many people coming in to look for their old homes. On reaching our old camp we again crossed the river to where we had buried what we had found. We had two boxes with us into which we put the remains and started back with them, having collected a number of the King’s wives and many people who came in. The journey was rather a sad one as occasionally we would pass corpses just out of the path, small boys principally. And those ladies were a terrible handful, not at all appreciating their altered circumstances and that we were trying to make things as pleasant for them as possible before getting as far as Bulawayo, where we left them, or they had left us, at various places.

On arrival I reported to Dr Jameson, went to my house, and collapsed, the reaction was so great. I had been living at strong tension all the time.”

Dawson’s account in his Diary

In his diary Dawson wrote the battle site was a small space of about 15 yards (14 metres) in diameter, literally covered with bones, men, and horses more or less mingled…all the heads were in this small space except one which was about 10 yards (9 metres) off. This was the man who was so hard to kill that they were almost going to leave alone because he was a wizard. This we determined to bring back for recognition – a strong built dark man with clipped beard and moustache.

Stafford Glass writes, “This man, as is now well-known, was Harry (Henry) Borrow, whose end has been described by Frank Johnson…survivors of the attacking Matabele…never tired in subsequent years of recounting that epic scene and describing how, ultimately, only one man was left standing, a man taller than the rest, who with empty rifle took off his hat and sang a song – obviously ‘God Save the Queen’ – until ha also fell. That was my friend Harry Borrow.”[29]

Capt Walter Howard’s account in the Bulawayo Chronicle of 9 July 1904 / Rhodesia Genesis (P94-104)

Howard states that Wilson’s orders included following the spoor of the King’s wagons – he says they expected the patrol to end when they captured the King and that the patrol would return the same evening. On the southern bank of the Shangani river, Forbes’ force stayed awake for hour after hour awaiting news.

About 11pm Capt Napier with Trooper Robertson and Scout Mayne [should be Bain] crossed the Shangani river bringing the message that Wilson intended to attack the King’s camp at daylight. At this point Howard volunteered to swim the river and attempt to establish the state of the Wilson party, but Major Forbes could get no volunteers to go with him and so his request was refused.

Next morning, the 4 December 1893, the main force began travelling up the Shangani, the river being on their right when an intense sound of gunfire could be heard from the northern bank and orders were given to push on with all speed.[30] After about two miles about 200 amaNdebele ran to the edge of the Mopane trees and began firing at them. The BBP Maxim under Sgt-Major Wagstaffe returned fire, a three-sided square was formed, the river being the fourth and the fighting continued for about an hour. Sounds of firing could be heard from the northern bank before it slackened and then died out altogether.

About 11am Major Forbes gave the order to retire on the previous night’s position with the idea that Wilson would rejoin the main column there.[31] By 4pm the Shangani river was a raging torrent about 137 metres (150 yards) wide[32] and during this retirement the scouts Burnham and Ingram with Trooper Gooding reached the main column with the news that made everyone fear the worst.

A terrific thunderstorm broke out that evening during which Ingram and Lynch set off for Bulawayo with a message for Dr Jameson telling him what had happened and that the column would retreat to the drift they had crossed on the way to Bulawayo; that they needed ammunition; had wounded men and no rations. They arrived in Bulawayo, but their nerves were so strained that they were unable to give any coherent message.[33]

In February 1894 Dr Jameson requests Dawson and Reilly to travel to the Shangani river

Dr Jameson requested James Dawson and James Reilly[34] to travel north to make contact with Lobengula, who was supposed at the time to be alive, and establish the fate of the Wilson patrol. Dawson and Reilly buried the bodies on the battlefield and cut a memorial cross on a Mopane tree. Afterwards their bodies were interred at Great Zimbabwe. Later their remains were exhumed once again and transferred to the Matobo in March 1904 near the spot where Cecil Rhodes had been buried on 10 April 1902. Their monument was unveiled by the administrator at the time, Sir William Milton, KCMG and dedicated by the Bishop of Matabeleland, Bishop Gaul on 5 July 1904, in the presence of a large crowd.

Painting belonging to the Bulawayo City Council by Allan Stewart depicting the last stand of the Shangani Patrol

Dawson and Reilly’s account of their mission from the Matabeleland occupation souvenir[35]

In February 1894 James Dawson,[36] a long-time trader at Bulawayo and accompanied by James Reilly was asked by Dr Jameson to seek an interview with Lobengula. By that time however, Lobengula was dead, although they did not know this until they met a party of amaNdebele returning to Bulawayo from the Shangani battle site. The amaNdebele on seeing Dawson dropped their guns and bundles and held their hands above their heads. One man gave details of the circumstances of the King's death. Dawson immediately wrote to Dr Jameson telling him what he had heard and saying that he would try and confirm the news, and also try to find the remains of Allan Wilson's party and give them a temporary burial.

Dawson and Reilly continued north for four more days before meeting another party of amaNdebele on 15 February who were on the northern bank of the Shangani river which was still in flood. Dawson said, “On the other side of the river there were a lot of young villains who talked to us a bit roughly, in fact, they threatened to boil us like pheasants in our jackets. It was fortunate for us that the river chanced to be full and impassable. Of course they took it, seeing there were only two of us, that we were spies sent out by the main body. At any rate, we used to interview them by shouting across the river. Later we got them to bring some of the older men down to the river to talk to us so that we soon got on better terms with them, the older men being pleased to see us.

On the eighth day after this, the river became passable, when we crossed over. [i.e. 23 February 1893]

I told them we wanted to see some of their headmen. They would not go and fetch them. I went up to their kraal and ordered them to bring their headman, saying that I was going away and that I expected them to do what I had ordered. I also told them that they were to show me where the remains of Wilson's party were, and they would have to assist me to bury them. They said they would show me where they were, but they would not help me bury them. They showed me where the remains were, which was about four miles from where Major Forbes had fought. The remains were all lying in a small space; what I might call an irregular, oval space about 20 yards the one way and 15 yards the other way.”

The amaNdebele account of the battle

James Dawson said there was no doubt that Wilson's men had stood together and made their last stand in that small area. “The fight started a little way off where Lobengula’s wagons had been stopped and our men, finding they were far outnumbered and likely to be worsted, retreated in the hope of being able to rejoin the main body. But unfortunately, a great number of the Matabele had crossed the river in the early hours of the morning and Wilson's party met them.[37] Wilson had just time to send three men[38] to tell Forbes where they were, and explain their plight, when they were surrounded and hemmed in. The native say they could not understand why all should have stayed, as some of them could have escaped had they tried. But they had not tried because some of the horses had been killed, and those who had horses resolved not to desert their comrades in distress. So, they stood there and fought the thing out.

The natives were very loud in their praise of the way in which they fought. They called them ‘men of men’ - the very best of men they could wish to have before them. It was only the Maxims, they thought, which fought them before;[39] but they said they now saw what a few men could do with their rifles and revolvers. I consider this fight did more to settle the whole Matabele difficulty than a good many other things that have occurred, for from that day to this, the Matabele have been thoroughly subdued.”[40]

Dawson said it was difficult to arrive at the number of amaNdebele who were killed in the fight. He explained, “They took away all their dead with the exception of about half a dozen we saw lying there. The natives say these were men without any friends or they would have been taken away and buried. But you could tell by the trees how terrific must have been the fire, for the branches and stems of the trees were all torn to shreds by the bullets. It was one continual forest, and they fired out of the trees on all sides. Wilson’s party were in a small, lightly wooded spot in the forest, which was so dense they could not see far in any direction. One old man whom I brought in - he was the head of a little town - said that he went off with a party of men to take part in the fight, when he heard a shout and before they did anything at all, six of his men were lying dead and he then went back. This sort of thing would have gone on from early morning until well in the afternoon.”[41]

A comprehensive account of the battle by an amaNdebele who was there

The following was reported in the Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser of 23 July 1898 (P229)[42] This account was told by M’Kotchwana, a warrior of the iNgubo Regiment who is present at the battle.

“When the white Inkos[43] Wilson came across the big river Shangani, we watched him, and although he knew it not, he was surrounded on all sides by the remnants of regiments which had fought at the Bembesi, the Imbezu, the Nsukamini, the Nyamandhlovu and others. At nightfall we missed the white majakas,[44] but towards the rising of the sun, Mjaan, the great chief, came to us and said, ‘I have heard the white warriors in the bush: Come, let us go and kill them.’ We were about 1,000 in number, and without noise we went and surrounded the place where the white men had their fire. Two of them were standing up looking into the bush. Some of us made a little noise. One of the white men standing awake went and woke up another man. I think it was their Inkos. He came and looked all round into the bush, and then aroused all the other amakiwa. They got up, and I saw they were busy getting their ammunition ready and saddling their horses. As it drew near for the sun to peep over the edge of the world, we started firing at the white men. They mounted their horses and tried to proceed in the direction of the great Shangani. But our men shot well, and horses dropped dead. It was a cloudy morning and the rain fell fine and swiftly. There were as many amakiwa as three times the fingers on my two hands. Most of them had black covers over their shoulders (capes)

When the white warriors found they could not go on, they shot the living horses and stood behind them waiting for us. We fired our guns at the white men, but at first, they did not do us much harm, as we were well protected by the trees and bushes. As the sun rose, we noticed several of the white warriors lying dead. Mjaan gave orders to rush up to the enemy. We issued from behind the protecting trees and tried to run up to kill Wilson and his party, but they killed many of us with the little guns in their hands and wounded more.

‘How many were killed and wounded in that first rush, M’Kotchwana? As many as six times the fingers of my two hands - so many’ and the old warrior waved his hand six times. ‘But how many were killed outright? So many’ said M’Kotchwana, signifying 40. ‘Then we went behind the trees and fired often, till many of the amakiwa fell and few remained. Again, Mjaan said, ‘Let us kill all that are left’ but some of them said, ‘No, they are brave warriors; let us leave the life in those who are not yet dead. But the men of the Imbezu said, ‘No, let us kill all the white men.’

Again, we rushed against the few who remained standing. When they saw us coming, they made a big singing noise and they shouted three times. They killed more of us. I was struck near the temple and remembered no more. My brother told me afterwards that all the white men fell fighting till the end. They were brave men, my father. The next day at sunrise we took all their clothes and skinned the face of the biggest white Majaka and took it to Lobengula, who was away one day's journey. The great chief said that was not the skin of the leader. We returned and took yet another skin off the face of a white chief. When Lobengula saw it, he was satisfied. He asked whether his Imbezu regiment had done all the killing. When he learned that they had not done more than others, he said, ‘Have I then all this time put my trust in a lump of dirt?’ I had two sons killed that day, my father, said M’Kotchwana and my brother was shot in the stomach. The amakiwa were brave men they were warriors.

When asked how he obtained possession of the cape, M’Kotchwana said it was on a white soldier who was killed before the first rush. He fell outside the ring of dead horses; they thought he was not dead and kept on shooting at his body. When the natives ran up, M’Kotchwana seized this cape off the white man's body.”

How long did the battle last?

Information from Forbes and others is confusing. The first skirmish was at daylight at the King’s wagon, there had been a second skirmish to the east and nearer the Shangani river at an antheap, the final last stand seems to have started about 7 - 7:30am on the 4 December.

Captain Finch said he heard nothing after about 8:30am, Walter Howard, does not give a time, Forbes stated, “the only firing reported after this was a few shots said by those that heard them to be further up the river than the previous firing and almost 2 hours after.” (i.e. about 9:30am)[45]

Mhlahlo, who served in the Nsukamini Regiment under Manondwane said, “We started the fight at break of day, and it was all over by the time the sun was there” (indicating about 10am) iNduna Sivalo Mahlana in 1918 said, “we fought from sunrise to midday.”

Wilson’s patrol apparently did not sing God Save the Queen[46]

The confusion seems to have risen over several amaNdebele statements. For instance, Machasha, an iNduna of the Nsukamini Regiment said, “We were being reinforced every minute by men coming in. Had it not been for that they would have beaten us off. After a time, the white men did not fire quite so much, and we came to the conclusion that their ammunition was getting short. We were preparing to rush in again when all the white men that could stood up, took off their hats and sang. We were so surprised that men could sing in the face of death that it took us some time to make up our minds what to do. Even when their cartridges were done and most of them were down, we could not stab them because of their revolvers which they shot us with until the last cartridge. Most of them shot themselves with that and those who had no shots left just covered their eyes and died without a sound, brave men as they were.”[47]

Dawson continued, “it is quite true that those who were wounded and could not get up, loaded the rifles for the others, for the natives told us that the whites cheered frequently. They can imitate cheering and the way the natives gave the ‘Hip, Hip, Hooray’ confirms this.”

The amaNdebele who were at the fight said the white men frequently called upon them to come closer and fight it out. They replied, “No, we have got you today, and we are going to take our time for this job.” This in a very jeering tone.

Dawson said they were 34 in Wilson's party and against them probably 3 - 4,000 amaNdebele. Wilson's men would have had about 100 rounds per man for their Martini-Henri rifles and he said there was very little unspent ammunition left.

Dawson and Reilly collected the remains of the fallen men at the site and gave them a temporary burial. “We put bushes over the grave and cut a cross in a big tree with the inscription, ‘To brave men.’ That, in fact, was the only thing we could do as we knew they would be removed. We could not bring them away with us as we had no transport.”

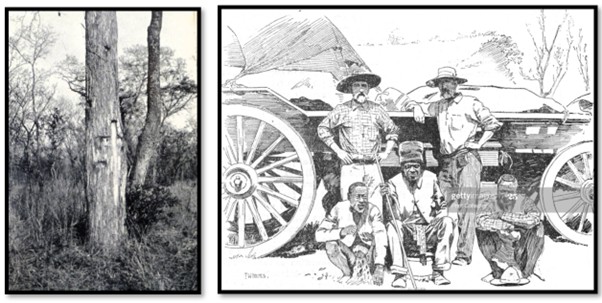

Central African Archives: The cross cut into a Mopane tree by Dawson and Reilly with the inscription, ‘To Brave Men.’ Barry Brown: sketch of Dawson and Reilly, although Dawson states they had no transport for the bodies

Dawson said he was sure Wilson and his men did not sing,[48] but he thought they might have cheered. He asked the amaNdebele who were there to imitate the sounds the white men made and they imitated, “Hip Hip Hooray.” Dawson concluded, “There is a story that they joined in a song before they died, but I cannot find that this is true.”[49]

The identity of the last person will never be known

The amaNdebele who were present at the battle told Dawson that when all the white men had been killed except one, he had gone off to a little mound in an open space 20 yards away and they said, “When the natives came on, he beat them off. The natives began to think he was bewitched, so they gave him time to collect several rifles and revolvers from the remains of the party and he took them to this place. When they came on again, he must have fought splendidly, because he killed a lot of them. He emptied all his guns and then took to his revolvers. He beat them off twice, but he was at last shot in the hip. But even on the ground, he still fought until he was killed.”

Dawson was unable to discover the identity of that person, but he was told this by many amaNdebele who were there.[50] However, the truth of this was confirmed by Dawson who reported that they collected thirty-three skulls,[51] “all except one were lying in a circle of 15 yards diameter with the bones of a good many horses – the one exception was found twenty yards outside the ring.”[52]

Lobengula's death was confirmed by the iNduna Mjaan who told Dawson he had buried, “the calf of the Elephant” in a cave, in all his feathers and finery, afterwards closing up the cave with rocks and stones.[53] Dawson said the Lobengula he knew was a pleasant and agreeable man, unless he was in a bad humour, which was occasionally the case, adding he would, however, make up for it when he got better tempered.

The first grave of Major Allan Wilson and his men at Shangani (Pupu)

Photo courtesy of Rob Burrett: Shangani (Pupu) Memorial site in the 1980’s

At a later date the above memorial was erected at the site of the Shangani (Pupu) Memorial site

The Sunday News; Pupu Shangani Battlefield National Memorial today

Roll of Honour - Biographical details of those members of the Shangani Patrol who perished on 4 December 1893

Victoria Volunteer Force

Sergeant Clifford Bradburn was born in 1868 and came from Edgbaston, Birmingham and before arriving in South Africa in 1890 he worked for the Birmingham Bank. He was a Trooper in D Troop of the British South Africa Company Police[54]

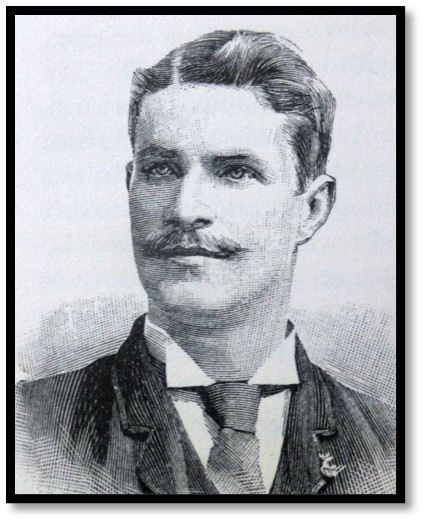

Sergeant Clifford Bradburn

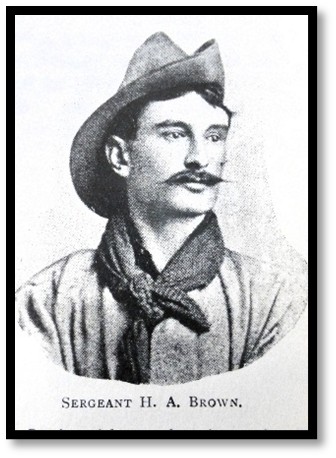

Sergeant Harold Alexander Brown was educated at Harrow and Exeter College, Oxford and had a great love of travel and adventure including authoring a book called A Winter in Albania. He was a Trooper in A Troop of the British South Africa Company Police.[55]

Sgt Harold Alexander Brown

Corporal Frederick Crossley Colquhoun was born in Edinburgh, farmed in Canada in 1887-8 and came to the Cape in 1889 before joining the Pioneer Corps in 1890[56] and subsequently joining the British South Africa Company at Victoria. He volunteered to serve with the Victoria Rangers.

Cpl Frederick Crossley Colquhoun

Trooper Dennis Michael Cronly Dillon was the son of John Dillon, Postmaster-General of the Punjab and born in India in 1868. He was a signaller in the Victoria Rangers

Tpr Dennis Michael Cronly Dillon

Captain Frederick Fitzgerald commanded No 1 Troop of the Victoria Rangers. Before the campaign he was a sub-inspector in the British South Africa Company Police at Victoria. (See photo of 1893 Victoria Column Officers)

Captain Harry Greenfield was quartermaster of the Victoria Column. Born in Devon in 1861 and educated at Tavistock Grammar School. He worked for the National Bank of the Orange Free State[57] before moving to Kimberley where he was overseer at a diamond mine before reaching Mashonaland. He volunteered his services in 1893 when he was appointed a Captain in the Victoria Rangers.

Captain Harry Greenfield

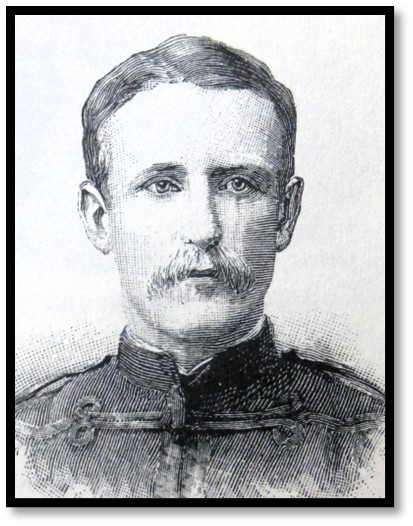

Sergeant-Major Sidney Charles Harding was born in Kensington in 1861 and educated at St. John’s College, Cambridge. His father was Colonel Charles Harding of the Fourth Queens Royal West Surrey Regiment. He was appointed a Lieutenant in Dyme’s Mounted Rifles and then joined the Natal Mounted Police. In 1889 he joined the Bechuanaland Border Police and served for four years before resigning and moving to Victoria where he was appointed Troop Sergeant-Major.

Troop Sgt-Major Sidney Charles Harding

Trooper Harold John Hellet volunteered for the Victoria Rangers

Lieut Arend Hermanus Hofmeyer was the son of a Dutch Reformed Church clergyman in the Cape and second lieutenant in No 4 Troop.

Lieut George Hughes was the son of an Irish Methodist minister and educated at Methodist College, Belfast. He joined a brother in South Africa. He was a Trooper in D Troop of the British South Africa Company Police[58] (No 457) and on his discharge worked for the Bechuanaland Exploration Company as a prospector. In 1893 he was appointed Lieutenant in No 1 Troop.

Lieut George Hughes

Captain William Joseph Judd commanded No 4 Troop of the Victoria Rangers and was originally farming at the Cape before joining the Pioneer Corps in 1890[59] and afterwards taking up transport riding in Mashonaland. (See photo of 1893 Victoria Column Officers)

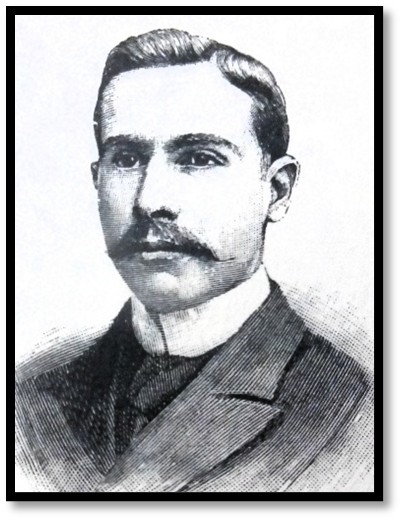

Captain Argent Blundell Kirton was born at Portsmouth in 1857, the son of Major E.B. Kirton of the Royal Engineers. At sixteen he went to South Africa and joined his two brothers; one died from fever and the other from a fall from his horse. He farmed near Zeerust and travelled to Matabeleland prior to 1890. He married Katherine, daughter of Rev Thomas Morgan Thomas in 1887 leaving a widow and three children on his death. In 1893 he was working for Sir John Willoughby at Victoria and volunteered for service. He was in charge of transport and at Bulawayo volunteered to join Wilson’s Patrol.

Captain Argent Blundell Kirton

Troopers Robert Oliver and Alexander Hay-Robertson both joined the Victoria Rangers.

Trooper John Robertson came from Pitlochry, Scotland and was born in 1867. His letters home vividly described the occupation of Matabeleland.

Tpr John Robertson

Trooper Earle Edward Welby was attached to the Victoria Rangers.

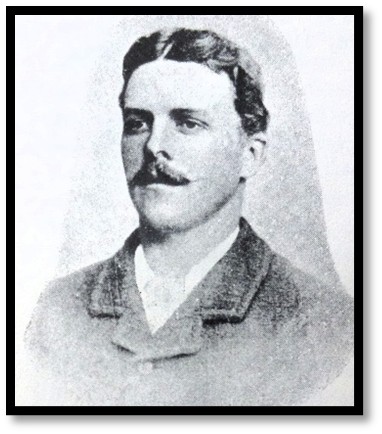

Major Allan Wilson, son of Robert Wilson, a railway and road contractor was born in Ross-shire,[60] Scotland in 1856. He was educated at the Kirkwall Grammar School and Milne’s Institution, Fochabers. He served in the Cape Mounted Rifles and received a Lieutenant’s commission in the Basuto Police resigning for service with the Bechuanaland Exploration Company. As senior officer in the Victoria Volunteer Force he volunteered when the Matabele campaign was launched and was appointed Major in command of the Victoria Column.

Major Allan Wilson[61]

Salisbury Horse Volunteers

Trooper William Abbott was born at Thornthwaite, Cumberland and arrived in South Africa in 1889. He worked for the Bechuanaland Trading Association for three years before leaving to go prospecting in the Mazoe district in 1893. Volunteered for the Salisbury Horse Volunteers and was assigned to B Troop.

Tpr William Abbott

Trooper William Bath

Born in 1856 in London he joined the Cape Mounted Rifles in 1876 and fought in the 1879 Basuto Campaign at the storming of Morosi’s Mountain with Allan Wilson. After leaving the CMR as a sergeant he became an overseer at a Kimberley diamond mine, later joining the Bechuanaland Border Police (BBP) In 1892 he was in charge of a crushing plant at the Langlaagte Estate and Gold Mining Company before leaving for Mashonaland in June 1893 and volunteering for the Salisbury Horse Volunteers.

Tpr William Bath

Sergeant William Henry Birkley was born in London and immigrated to South Africa in 1884 where he joined the Cape Mounted Rifles, then Carrington’s Horse. He was working as a solicitor in Salisbury when hostilities began. He served in B Troop of the Salisbury Horse Volunteers.

Sgt William Henry Birkley

Captain John Henry Borrow commanded B Troop of the Salisbury Horse Volunteers. Born on 17 March 1865, the eldest son of the Rev J.H. Borrow of Cornwall and later Canterbury. He arrived in the Cape in 1882. In March 1887 with his friends Frank Johnson and Maurice Heany they went on a prospecting expedition to Mashonaland. In the 1893 occupation of Matabeleland, he was the first man to enter Bulawayo having been sent forward with a patrol of twenty men to take possession before the main body arrived.

Captain Henry John Borrow

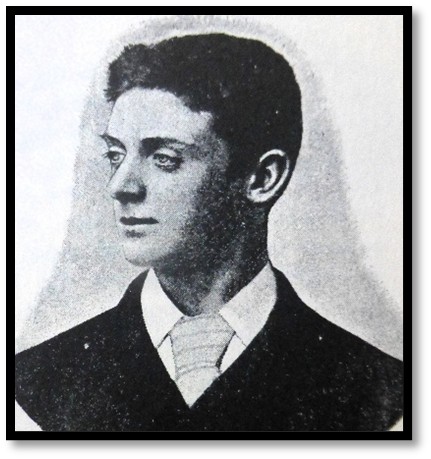

Trooper William Henry Britton was born at Halstead, Essex in 1870 and was just 19 when he arrived in Mashonaland. After the Victoria incident he volunteered for service and was part of the Salisbury Column that occupied Matabeleland.

Tpr William Henry Britton

Corporal Harry Graham Kinloch was born at Norwood, Surrey in 1863 and educated at Harrow and then Trinity College, Cambridge and had been practising as a solicitor in Salisbury. A good athlete, he played cricket and was a champion light-weight boxer. Volunteered with the Salisbury Horse and was a member of B Troop killed at Shangani.

Trooper George Sawers Mackenzie was born in India in 1860 and arrived in Mashonaland in 1890 with D Troop of the British South Africa Company Police[62] and on his discharge worked as an assayer for the Zambezia Exploration Company before joining the Salisbury Horse Volunteers.

Trooper Matthew Meiklejohn came to Mashonaland from Cape Town and worked for Frank Johnson and Co Limited before being recruited into B Troop with the Salisbury Horse Volunteers.

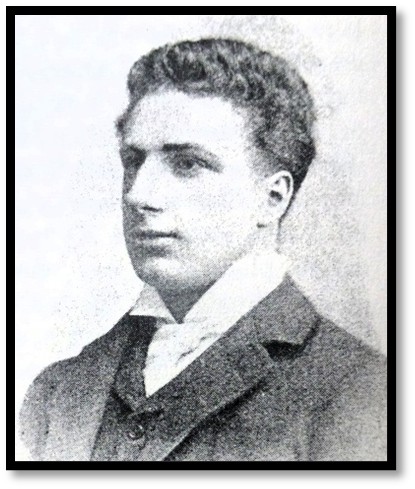

Trooper Harold D.W.M. Money was in B Troop of the Salisbury Horse Volunteers, his father was Major-General Money. He was born in 1872 and educated at Wellington College and came to Mashonaland with Henry Borrow volunteering to join B Troop a few weeks after he joined the Salisbury Horse Volunteers. A great athlete, he enjoyed riding and shooting.

Tpr Harold Dalton Watson Moore Money

Trooper Percy Crampton Nunn was born at Bury St Edmunds in 1855, his father was a Professor of music. He arrived in South Africa in 1881 and served in the Cape Mounted Rifles and later in the Bechuanaland Border Police. During the occupation of Matabeleland, he forwarded illustrated accounts of the march to the Daily Graphic with his last contribution on 19 December 1893.

Tpr Percy Crampton Nunn

Trooper William Alexander Thomson was born in Aberdeen, Scotland in 1871. He left for the Cape in 1889 and worked in Rondebosch for two years. He came up with the Van der Byl trek to Laurencedale, near Rusape, and was in charge of medical care arriving in Mashonaland in early 1893. He volunteered after the Victoria incident and was accepted into B Troop of the Salisbury Horse Volunteers. He was just 23 years old when killed in action at Shangani.

Tpr William Alexander Thomson

Trooper Henry St. John Tuck left England for the Cape in 1889 having served in the Royal Navy Artillery Volunteers. He served in the Cape Mounted Police before joining the British South Africa Company Police in C Troop in 1890.[63] Hickman writes that he went with Captain P.W. Forbes to negotiate a treaty with Chief Mutasa in Manicaland and tremendously impressed the natives with his magic when he removed his glass eye! At the end of 1891 he was discharged from the police and started farming with his partner L.N. Papenfus, later a well-known surveyor. Both joined the Salisbury Horse Volunteers with Tuck going into B Troop.

Tpr Henry St. John Tuck

Trooper Frank Leon Vogel was second son of the Hon Sir Julius Vogel, KCMG and born in Auckland, New Zealand in 1870 and educated at Charterhouse. He arrived in South Africa in April 1891 and became a Trooper in the Mashonaland Mounted Police at Tuli. Then joined the survey department at Salisbury and then became assistant secretary to Dr Jameson, the administrator. He served on the Maxim gun at the Battle of Shangani (Bonko) and volunteered for special scouting work. At the Battle of Bembesi (Egodade) he had a narrow escape when a bullet went through his hat.

Tpr Frank Leon Vogel

Trooper Philip Wouter de Vos and Trooper I. Dewis both joined the Salisbury Horse Volunteers and took part in the occupation of Matabeleland.

Trooper Thomas Colelough Watson was educated at Wellington College, the son of a Colonel, the grandson of a Colonel and the great grandson of a Colonel. He initially joined his father in India, then spent four years in Tasmania before arriving in Mashonaland in 1891 and volunteering for the Salisbury Horse Volunteers.

Tpr Thomas Colclough Watson

Trooper Henry George Watson joined the Salisbury Horse Volunteers soon after arriving in Mashonaland.

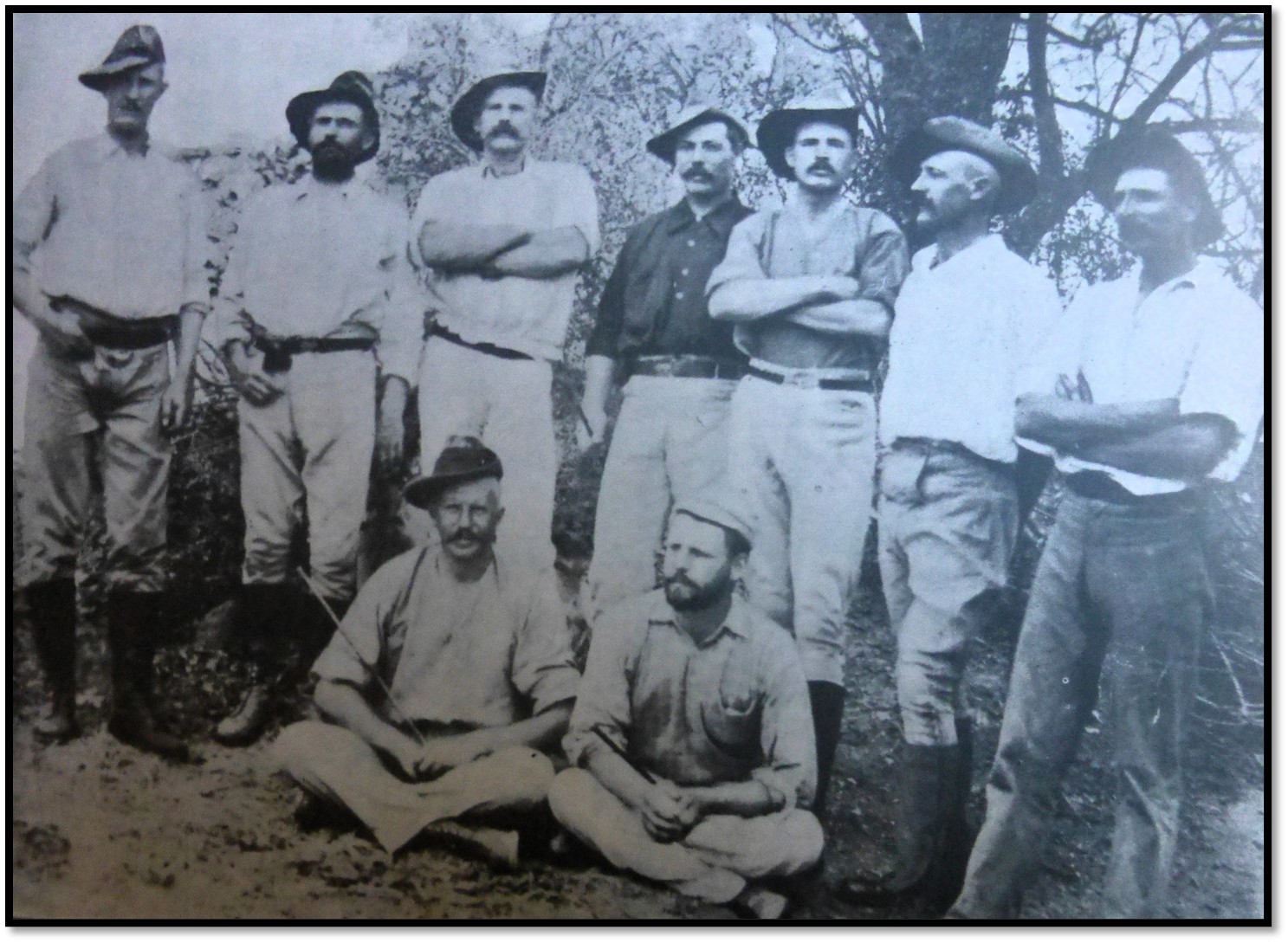

1893 Victoria Column Officers

NAZ: Standing (L-R) Lieut Stoddart, Capt Judd*, Major Allan Wilson*, Capt Napier, Capt Fitzgerald*, Lieut Hamilton, Lieut Williams

Seated (L-R) Lieut Sampson, Adjutant Kennedy

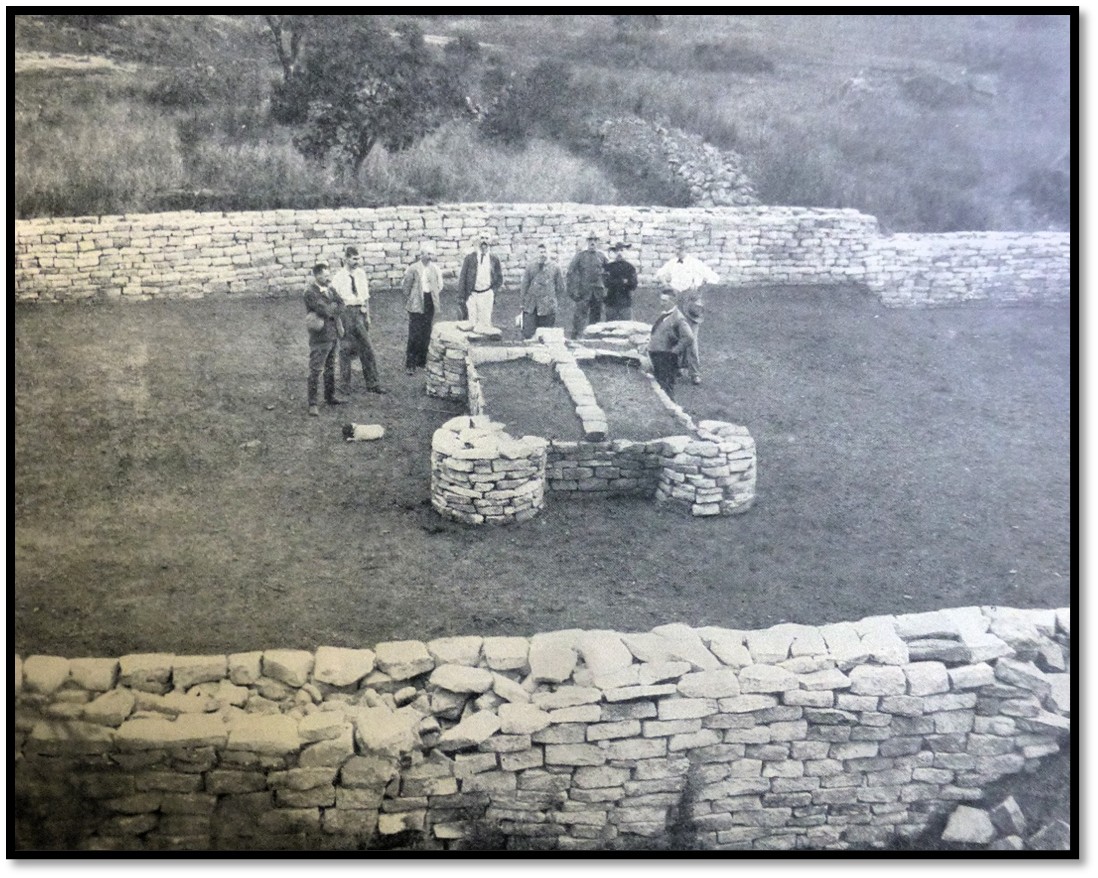

The Patrol’s remains are exhumed and reburied at Great Zimbabwe

Obviously, the isolated initial burial place at the present Shangani (Pupu) Memorial site was unsuitable, except as a temporary measure. Dawson writes that after their first trip in early February 1894 they returned with a wagon with supplies and medicines to the Shangani river and to the battle site, “We had two boxes with us into which we put the remains and started back with them…”

Robert Cary writes between 18 July – 9 August the bodies were moved to Victoria (present-day Masvingo) “After the service in the small Church of Saint Michael and all Angels in Fort Victoria on 13th August a procession, accompanied by an escort of six mounted men from the different units which had taken part in the fighting, made the pilgrimage to the Ruins (Great Zimbabwe) At the site of the grave a stone surround was built and everyone in Rhodesia assumed that the thirty-four gallant young men had made their last journey.”[64]

The second grave of Allan Wilson and his men at Great Zimbabwe. Their remains were transferred to the Matobo in March 1904

In 1904 their remains are exhumed once more and moved to the Matobo

After John Tweed, the sculptor, was commissioned to design a memorial in the Matobo, there was much opposition from the citizens of Fort Victoria. “Secret plans were made, and one morning in February 1904 the townspeople woke to find that the bodies had been disinterred during the night and were already on their journey to the Matobo. Fort Victoria was furious. A mass meeting was held and resolutions were passed castigating the government's action as ‘high handed’ and ‘illegal;’ the Volunteers in the town unanimously handed in their resignations in protest against the ‘insult’ which had been done to them.” [65]

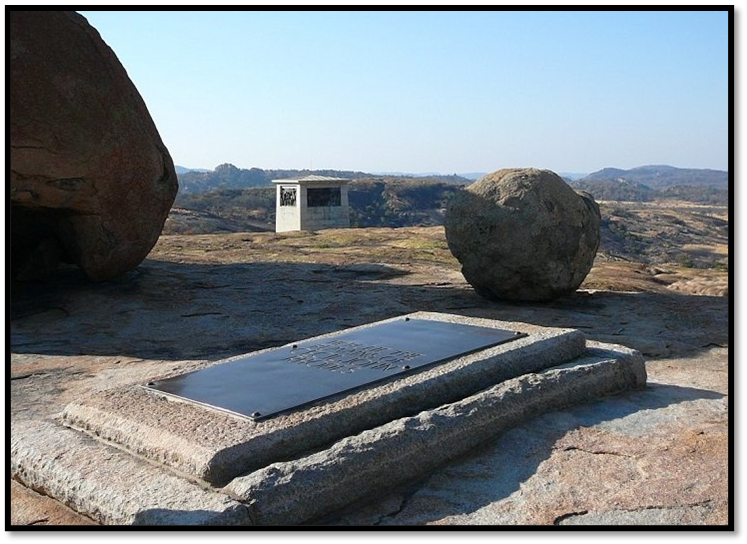

View across Rhodes’ grave to the Shangani Memorial

The memorial to the Shangani Patrol is on top of Malindidzimu in the Matobo Hills, it was requested by Cecil John Rhodes in his will that he wished to have the patrol re-interred alongside him at World's View and this was done two years after his death.

The memorial is made of granite blocks quarried nearby. Herbert Baker designed the memorial, and each side has a bronze panel by John Tweed with each of the members of the Troop shown in relief. The main inscription has, "To Brave Men" with a smaller dedication underneath, "To the enduring memory of Allan Wilson and his men whose names are hereon inscribed and who fell in fight against the Matabele on the Shangani River on December the 4th, 1893. There was no survivor."

The Bulawayo Chronicle of 9 July 1904 has a long description of the opening ceremony summarised as follows: “Soon after 11 o’clock [on the 5 July, 1904] the Pioneers formed up and led by the Southern Rhodesian Volunteers (SRV) the band playing funeral marches, marched to the summit of the View of the World, where a square was formed of the SRV with the Pioneers inside. A short delay occurred, but soon His Honour the Administrator,[66] accompanied by the Archbishop of Capetown, Archdeacon Reeves and Colonel F, Rhodes advanced to the Memorial, where the service was conducted. This consisted of Hymns 165 and 540, with short prayers. The unveiling of the Memorial was announced by a flourish of trumpets, after which and at the conclusion of the dedication, an address was given by His Honour the Administrator.”

The Shangani Memorial itself

The Bulawayo Chronicle article provides some details on the construction of the Memorial that is situated 102 metres (112 yards) south east from Rhodes’ grave. It is composed of massive blocks weighing from three to seven tons that were quarried from an adjacent kopje. The square structure has sides measuring 7 metres (23 feet) and is 10 metres (33 feet) high. Internally is a cubic vault of 3 metres (10 feet) where the remains of Wilson and his colleagues are placed. Mr J. Loughton oversaw construction.

The bronze panels were the work of John Tweed who made the individual figures stand out in relief.[67]

West Panel

North Panel

East Panel

South Panel

Roll of Honour

West Panel | East Panel | |||

Capt Henry John Borrow (mounted) | Commanded B Troop | Tpr Percy Crampton Nunn | B Troop | |

Sgt Harold Alexander Brown | Victoria Rangers | Tpr Henry St. John Tuck | B Troop | |

Tpr Harold Dalton W.M. Money | B Troop | Tpr Thomas Colclough Watson | B Troop | |

Sgt-Major Sidney Charles Harding | Victoria Rangers | Capt Frederick Fitzgerald (mounted) | Commanded 1 Troop | |

Major Allan Wilson (mounted) | Commanded Victoria Rangers | Tpr Alexander Hay Robertson (mounted) | Victoria Rangers | |

Capt Argent Blundell Kirton (mounted) | Transport, Victoria Rangers | Tpr William Alexander Thomson | B Troop | |

Cpl Frederick Crossley Colquhoun | Victoria Rangers | Tpr William Bath | B Troop | |

Cpl Harry Graham Kinloch | B Troop | Tpr John 'Jack' Robertson | Victoria Rangers | |

Tpr Edward Brock | B Troop | Sgt Clifford Bradburn | Victoria Rangers | |

North Panel | South Panel | |||

Tpr L. Dewis | B Troop | Tpr Matthew Meiklejohn | B Troop | |

Lieut George Hughes (mounted) | 1 Troop | Lieut Arend Hermanus Hofmeyer (mounted) | 4 Troop | |

Tpr Dennis Michael Dillon | Signaller, Victoria Rangers | Tpr George Sawers Mackenzie | B Troop | |

Tpr Philip Wouter De Vos | B Troop | Capt William Joseph Judd (mounted) | 4 Troop | |

Tpr Henry George Watson | B Troop | Tpr Edward Earle Welby | Victoria Rangers | |

Tpr William Henry Britton | B Troop | Tpr William Abbott | B Troop | |

Capt Harry Moxon Greenfield (mounted) | Qm, Victoria Rangers | Tpr Frank Leon Vogel | B Troop | |

Sgt William Henry Birkley | B Troop | Tpr Harold John Hellet | Victoria Rangers |

Details from A Time to Die, P169-171

Final tribute from Hugh Marshall Hole

Hole has the following to say, “Few episodes of Colonial history have more profoundly stirred popular sentiment then the tragic catastrophe of the Shangani river where a handful of the Mashonaland Volunteers - not trained soldiers, but just miners, farmers, clerks and traders - fired with the desire for achievement, fell into a trap and died, shoulder to shoulder, in a splendid but hopeless dash to capture the Matabele King. No doubt the emotion caused by their exploit was partly inspired by the uncertainty that for a long while hungover the actual details, some of which will never be known, for there was no survivor.

Alan Wilson, their leader, was a cool-headed Highlander, a man of well-knit, powerful frame, who had spent some years as a frontier policeman and had become manager of one of the mining syndicates working in Victoria. Those who went out with him on that last fateful ride, cheerily calling out to their messmates, as they cantered off, to keep supper hot for them, were all in the heyday of manhood, many of them trained in the public schools and universities of England and Scotland and the rest tough colonials well-used to campaigning in Africa. They were the very flower of the settlers and although there was no special selection of individuals to form the patrol, it would have been difficult to have picked a couple of score men better fitted to give a good account of themselves in a tight place. Indeed, it was some time before the rest of us in Salisbury and Bulawayo could bring ourselves to believe that so brave a company had been wiped out to a man by the broken and fugitive remnants of Lobengula's army. Native reports said that the King was still shaping his course for Mashonaland with Wilson's party hard on his heels. To this idea we clung, and it was some weeks before we grasped the full force of the disaster which had overtaken the patrol actually on its very first day.”[68]

References

Occupation of Matabeleland: A Souvenir printed for the celebrations held in Bulawayo between Monday 30 October to Sunday 5 November 1933

Barry Brown. Various snippets of useful information including book references and the Bulawayo Chronicle of 9 July 1904 which includes an account of the unveiling of the Shangani Memorial by Sir William Milton KCMG

Robert Cary. A Time to Die. Howard Timmins, Cape Town 1969

Robert Cary. The Pioneer Corps. Galaxie Press, Salisbury 1974

L.D.S. Glass. The Matabele War. Longmans, Green & Co, 1968

L.D.S. Glass. James Dawson, Rhodesian Pioneer. Rhodesiana No 16 July 1967 (P66-80)

A.S. Hickman. Men who made Rhodesia. The British South Africa Company, Salisbury 1960

H.M. Hole. Old Rhodesia Days. Books of Rhodesia, Silver Series Vol 8, Bulawayo 1976

H.M. Hole. The Passing of the Black Kings. Books of Rhodesia, Silver Series Vol 20, Bulawayo 1978

N. Jones. Rhodesian Genesis. (Walter Howard’s account P94-104) Rhodesia Pioneers’ and Early Settlers’ Society, Bulawayo 1953

W.A. Wills and L.T. Collingridge. The Downfall of Lobengula. Books of Rhodesia, Volume 17, Bulawayo 1971

Appendix

Lobengula’s Bath Chair

This information came from Barry Brown. Lobengula's bath chair was abandoned near Lake Alice between the Bubi and Gwampa rivers. Gwenda Newton in her article 'The Helms of Hope Fountain' wrote, "The Cape Government had sent Lobengula a bath chair on wheels as a present and had asked Charles [Helm] to deliver it. Charles’ mode of transport, which he found most useful, was a “Spider” (a small horse-drawn cart) but on the 18th it had broken down and he arrived at the King’s with the bath chair in his wagon. The bath chair had an elephant painted on each side of it and was topped by an umbrella with a gold fringe."

http://www.bulawayomemories.com/home_helms.../helms_2015.pdf

Artist sketch of Lobengula in his bath chair

The above sketch hangs in Rhodes' cottage in Muizenberg The bath chair itself had an elephant painted on its side, so cannot have been just "any old" bath chair; it must have been customised especially for Lobengula by the Cape Government.

Notes

[1] The third remaining white at Bulawayo, James Dawson, had taken the three emissaries from Bulawayo to meet Goold-Adams forces at Tati

[2] The Matabele War, P226

[3] James Dawson, Rhodesian Pioneer, P70

[4] Ibid, P71

[5] Chief Langalibalele refused to let the Natal authorities register their guns and after a violent skirmish he fled to Basutoland before being captured and held on Robben Island

[6] Barry Brown sent this account by Col C.L. Carbutt who was at one time Superintendent of Natives

[7] See the appendix for notes on Lobengula’s bath chair

[8] The advance was so slow in the very wet conditions that all the dismounted men and wagons were sent back to Emhlangeni – those that went on included 25 mounted men from B Troop of the Salisbury Column under Borrow, 49 under Major Wilson from the Victoria Column, 24 from the Tuli Column under Raaff and 35 from the BBP under Coventry) with two Maxims on galloping carriages, one drawn by mules and the other by horses. A pack horse carried ten days’ rations for every ten men. There were no tents and the only protection from the rain was their blankets and cloaks (Walter Howard)

[9] Forbes force left from Shiloh Mission on the 24 November 1893 (Walter Howard)

[10] Hugh Marshall Hole states they knew the King and his forces were close “for the smoke still rising from the fires at their last camp showed they were only just ahead.” The Passing of the Black King’s, P260

[11] A scherm is the local name for a thorn enclosure designed primarily to keep wildlife out at night

[12] The Downfall of Lobengula, p236-7

[13] The first group comprised Captain Napier, Scout Bain and Trooper Robertson were sent to Major Forbes to request reinforcements.

[14] The Matabele War, P229

[15] The second group consisted of Frederick Burnham, the chief Scout, Pearl Ingram, another American Scout, and Trooper G. Gooding

[16] Burnham’s breathless remark on reaching Forbes was, “I think I may say we are the sole survivors of that party.”

[17] The King’s bodyguard was from the Babambeni Regiment under the InDuna Dakamela Ncube

[18] This from Dawson’s papers in the National Archives of Rhodesia and taken from Rhodesian Genesis, P104-112

[19] Sekombo was an iNduna who took an active part later in the 1896 Matabele Rebellion against the settlers along with Somabulana, Umlukulu, Dhliso, and Hluganiso and others

[20] Dawson forgets to say he also had a letter from High Commissioner Loch promising Lobengula that he would receive good treatment and giving assurance that he would not be sent out of South Africa

[21] This letter was brought to Inyati on 1 March 1894 by runner (A Time to Die, P150)

[22] 23 February 1894

[23] Barry Brown questioned whether the bodies would have become skeletons between the 4 December 1893 and the date that Dawson and Reilly arrived at the battle site on 23 February 1894

[24] It is unfortunate that Dawson does not state the actual number of skulls collected and if this tallies with the thirty-four of the Wilson Patrol known to have been killed at the battle site

[25] Barry Brown referred me to the L.D.S. Glass article in Rhodesiana No 16 July 1967 (P66-80) James Dawson, Rhodesian Pioneer. Glass believes that Dawson kept the 1,000 gold sovereigns for himself instead of turning them in or even sharing them with Reilly. (75-76)

[26] See the article The Southern Column’s skirmish at the Singuesi river on 2 November 1893 revisited under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[27] Lieut-Col Goold-Adams

[28] Mgubongubo was one of the emissaries along with Mantuse and Ingubo (both killed) Dawson bears much some responsibility for this tragic outcome that caused much mistrust amongst the amaNdebele. A Commission of Inquiry under Major W.H. Sawyer, High Commissioner Loch’s Military Secretary, decided that Dawson was to blame because he failed to report himself and the iNdunas to Lt-Col Goold-Adams and instead had gone off with Selous for a drink and dinner. Sawyer wrote, “It is due to this unfortunate delay that the subsequent deplorable occurrences may be attributed.” (James Dawson, Rhodesian Pioneer P73) Dawson was in charge of the party and left the emissaries to get refreshment, leaving the three amaNdebele without telling the guards who they were. (A Time to Die, P27) Presumably, this is why he states he was uneasy.

[29] James Dawson, Rhodesian Pioneer P74

[30] Johan Colenbrander was heard saying to Major Forbes, “They cannot keep that up for long, sir, with their stock of ammunition.” (Walter Howard)

[31] “Outnumbered by thirty to one and with less than one hundred rounds of ammunition per man our position was very precarious, but no ammunition was wasted for a man did not fire until he was pretty certain of his mark… During our fight, our slaughter cattle had been driven off by the Matabele which was awkward for us in the extreme” (Walter Howard)

[32] “When we started off at dawn it was a sand river but, in the afternoon, it was almost impassable and in the following morning it was a wide, deep and fast flowing river.” (Walter Howard)

[33] This statement by Howard seems unlikely. Jack Carruthers (Rhodesian Genesis P102) states, “Dr Jameson on receipt of Forbes’s dispatch that he would follow up along the Shangani river, immediately formed a relief party of all the available men in camp at Bulawayo.” Major Forbes sent a written message – as a regular army officer this makes sense.

[34] In some accounts spelt Riley, for example in A Time to Die, P150

[35] Occupation of Matabeleland: A Souvenir printed for the celebrations held in Bulawayo between Monday 30 October to Sunday 5 November 1933

[36] James Dawson, a Scot who came to South Africa in 1870, worked briefly in a Grahamstown solicitor’s office, then in 1872 as Chief Khama’s secretary, until they quarrelled, and then visited Matabeleland in 1873 working for the trader James Cruikshank. He managed Cruikshank’s store at Shoshong 1875 – 1877 before moving to Bulawayo and becoming James Fairbairn’s partner where he stayed. Dawson, Tainton, Fairbairn and the other traders opposed the Rudd Concession of 1889 as they wanted a concession themselves. At Jameson’s request Dawson and James Reilly looked for Lobengula in 1894 and brought back the remains of the Allan Wilson patrol. Stayed on until 1898 in Matabeleland before moving back to Scotland in 1898 when he married Wilson’s former fiancée.

[37] The amaNdebele that fought against Wilson and his party included the following Regiments: Imbizo under INduna Mtshana Khumalo, Ingubo under INduna Fusi Khanye, Nsukamini under INduna Manondwane Tshabalala, Nyamandhlovu under INduna Phahla Khumalo, Ihlati under INduna Matshe Sithole

[38] The three men were the scouts Burnham and Bain and Trooper Gooding. Suggestions have made the three actually deserted to save their lives. Major Walter Howard said he had been told by Sir Aubrey Wools Sampson who participated in the Jameson Raid that Trooper G. Gooding made a deathbed confession to this effect. However, at the Court of Inquiry in late December 1893 both Burnham and Ingram’s accounts were consistent and Gooding gave the same account in a letter to his mother – Wilson gave the three horsemen orders to ride ahead and to request Forbes to bring reinforcements (A Time to Die, P103)

[39] At the battles of Shangani (called Bonko by the amaNdebele) on 25 October 1893 and Bembesi (called Egodade by the amaNdebele) on 1 November 1893

[40] For more information read the article Three oral history statements made in 1937 by amaNdebele warriors present at the killing of Allan Wilson and thirty-three other Europeans on 4 December 1893 at the Shangani River under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[41] Most accounts state the battle lasted about two hours

[42] Barry Brown sent me a copy of the article for which I am very grateful

[43] Inkos means leader

[44] Majakas are warriors

[45] A Time to Die, P106-7

[46] The Wikipedia entry on Allan Wilson states that his Troop sang God Save the Queen but the amaNdebele actually reported they said, ‘Hip Hip Hooray.’

[47] A Time to Die, P108

[48] The Wikipedia article on Allan Wilson states the survivors sang ‘God Save the Queen’ but this appears to contradict Dawson’s account following his interviews with the amaNdebele warriors who were present at the battle.

[49] A Time to Die, P111

[50] The Wikipedia article in quoting the 1895 play Cheer, Boys, Cheer! hints that the last person to be killed was Allan Wilson himself, but this is just speculation and there is no evidence of this. The same article also states, “Once both of Wilson’s arms were broken and he could no longer shoot, he stepped from behind a barricade of dead horses, walked toward the Ndebele, and was stabbed with a spear by a young warrior.” Again, Dawson who interviewed those who were there, makes no such claim. The Matabele talked of “the big, dark, bearded man, who defied them to the last” but this description is too general to identify any individual.

[51] Stafford Glass states they numbered 33 (The Matabele War, P229) However, the Roll of Honour lists 34 individuals

[52] A Time to Die, P109

[53] C.K. Cooke authored an article in Rhodesiana No 23 (December 1970) P3-53 entitled Lobengula, Second and Last King of the Amandabele: His Final Resting Place and Treasure

[54] Trooper Clifford Bradburn is listed as No 182 in Men who made Rhodesia.

[55] Sergeant Harold Alexander Brown is listed as No 473 in Men who made Rhodesia.

[56] Corporal Colquhoun is llisted as No 68 in the Pioneer Corps

[57] The Orange Free State ceased to exist after the Boer War and is now part of the Free State Province

[58] Trooper George Hughes is listed as No 457 in Men who made Rhodesia.

[59] Listed as No 62 in the Pioneer Corps

[60] Ross-Shire is now part of Ross and Cromarty

[61] The portraits are from The Downfall of Lobengula

[62] Trooper George Sawers Mackenzie is listed as No 797 in Men who made Rhodesia

[63] Trooper Henry St. John Tuck is listed as No 133 in Men who made Rhodesia

[64] A Time to Die, P166

[65] Ibid, P167

[66] The Administrator was Sir William Milton, KCMG

[67] In the Bulawayo Chronicle article Trooper Edward Brock is included on the North panel whereas he is included in the West panel in A Time to Die. The Bulawayo Chronicle lists nine figures on the North panel when in fact there are only eight. In total however both show a total of thirty-four casualties.

[68] Old Rhodesian Days, P96

When to visit:

Anytime

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: