George Westbeech and the road to Pandamatenga

Pandamatenga 18°31´30.22"S 25°39´45.79"E

Impalera Island 17°46´59.04"S 25°13´23.13"E

Introduction

This article is about two subjects; George Westbeech and the road which he built and maintained and is always connected with him from Tati to Pandamatenga. The text below combines accounts from Leask (1868) Mohr (1870) Selous and Oates (1874) Holub (1876) Decle (1892) Gibbons (1896) and Hodson (1907,8,9,10) Oates and Holub’s descriptions are the fullest. Once the Westbeech Road was established this route from Tati greatly superceded the Western Old Lake Route which passed through extremely dry and sandy country which was particularly hard on the trek oxen and had no villages like Tati where trekkers could rest and repair their wagons. There is a fuller description of Westbeech’s life later in the article, but the following may serve as an introduction.

I have not touched upon the impact George Westbeech had on promoting British interests in the region; he was even more influential than David Livingstone because he stayed in the Zambesi Valley and from his conduct of fairness and honesty in his dealings with them created in the native people a deep respect for Britain. He actively discouraged the Dutch and Belgian Jesuits, whilst actively promoting Rev Francois Coillard, a missionary of the Paris Evangelical Missionary Society who was an Anglophile. This topic is thoroughly explained in Richard Sampson’s book and in a later article on Westbeech’s diaries on this website.[i]

Westbeech

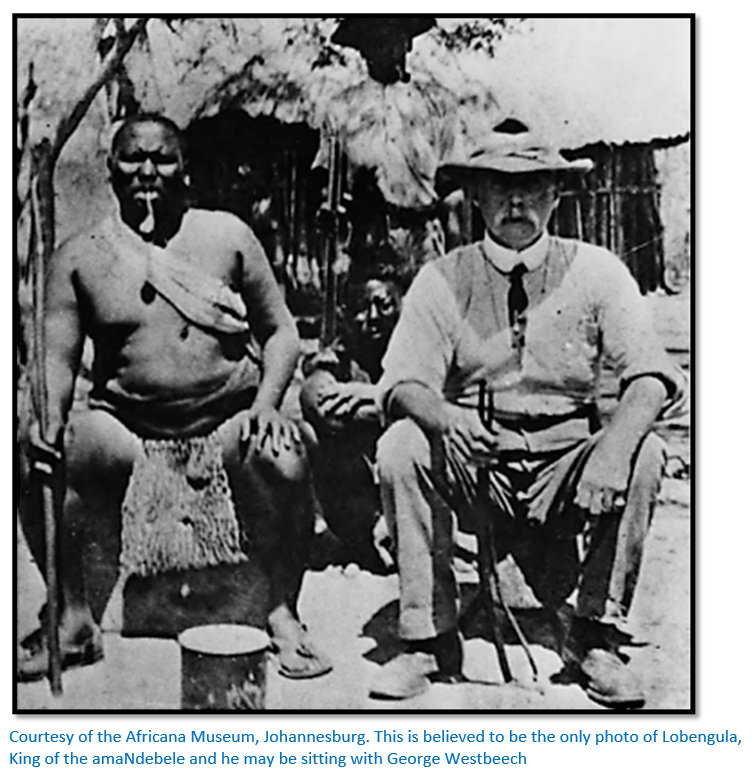

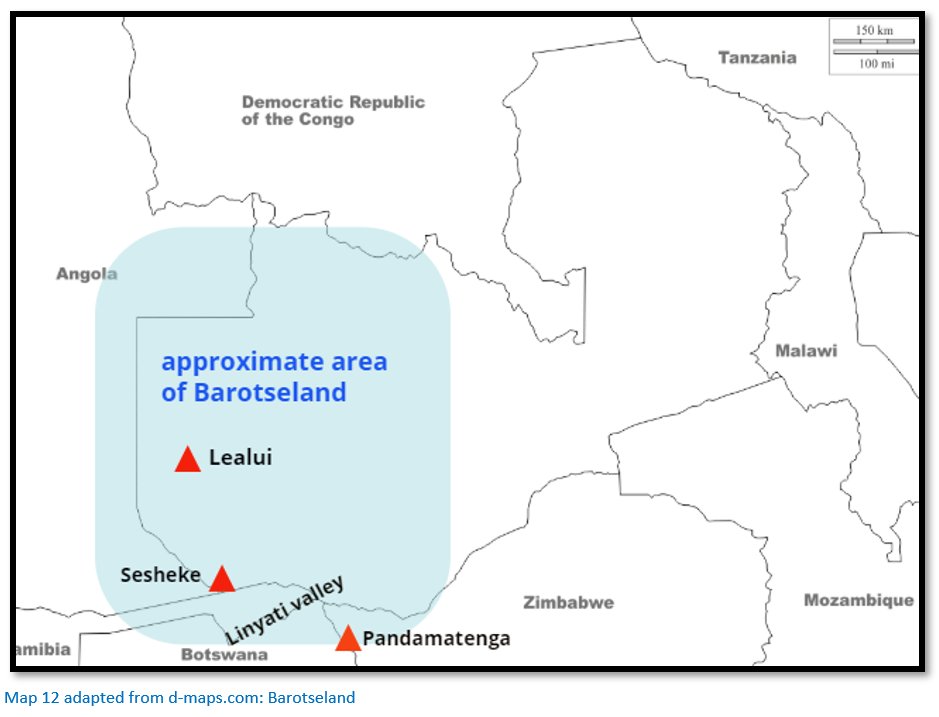

Westbeech entered Matabeleland in mid-January 1870 as a trader and he and George Phillips were amongst the few Europeans permitted by the regent Mncumbatha to stay in the country during the interregnum between the death of Mzilikazi on 9 September 1868 and Lobengula’s coronation at Mhlanhlandlela on 22-24 January 1870. This was the start of a trading partnership between Phillips and Westbeech that lasted twenty years. Phillips controlled trade in Matabeleland whilst Westbeech dominated trade in Barotseland, acting as a semi-official commercial agent for the Lozi or Barotse people. They gained the confidence and trust of Mzilikazi, Mncumbatha and then Lobengula.

In 1872 Westbeech returned to Barotseland in present-day western Zambia and cut the road from Tati that has been named after him. In 1871 or 1872 he established his headquarters at Pandamatenga on the headwaters of the Matetsi river.[ii] Westbeech gained the respect of the Lozi Kings Sipopa and Lewanika who granted him extensive trading and hunting privileges. From the hinterland of the region then called Zambesia he exported large quantities of ivory, hides and ostrich feathers and imported trade goods.

Sampson provides a great tribute to Westbeech which is worth quoting: “History aside, Westbeech also merits study as a remarkable human being. From the age of nineteen onwards he had the ability to impress himself on Chiefs who governed Matabeleland and Barotseland. The books written by explorers, travellers, hunters and traders all pay tribute to him. The Chief in Barotseland appointed him an InDuna (i.e. senior headman) and ordinary Africans came to recognise him as someone to look up to and who was prepare to assist them when in trouble.”[iii]

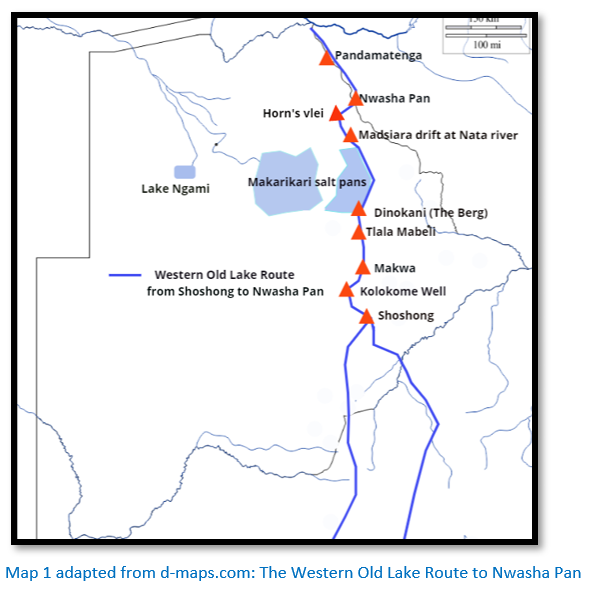

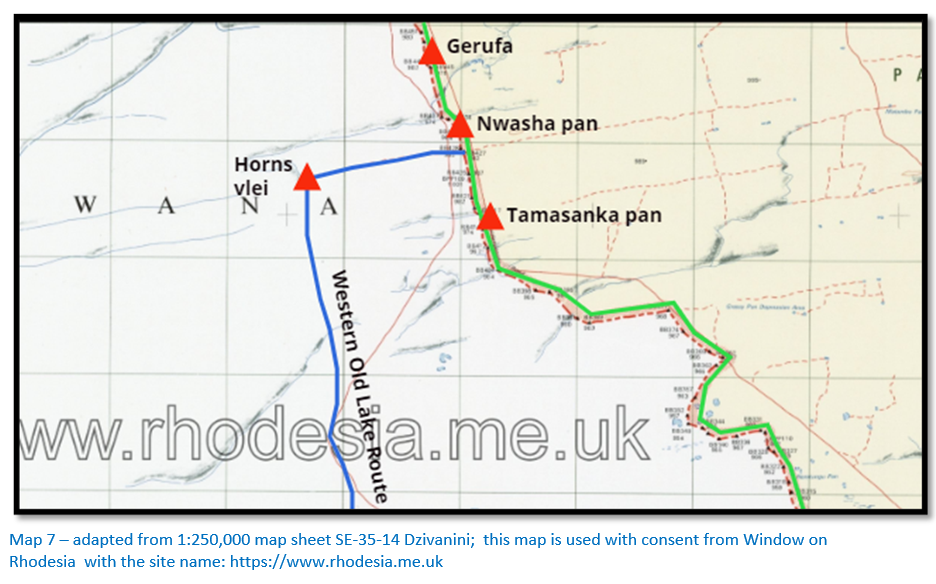

Western Old Lake Route

As stated above, Westbeech began trading in Barotseland in 1871 or 1872 and on his first journey north took the road to Nwasha pan using the Western Old Lake Route which left Shoshong going directly north, skirted the eastern edge of the Makarikari salt pans crossing the Nata river at Madsiara drift and joining what became the Westbeech Road at Nwasha pan. This route took about thirteen days by ox-wagon to cover the 217 miles (350 kms) which lay mostly through sand veld with summer-rainfall rivers and passed through thorn bush, mopane trees, grassy plains, and granite hills.

There is a good account of trekking this route on a hunting trip by Fred Barber in 1875.[iv] [See the article Frederick ‘Freddy’ Hugh Barber, hunter, trader, artist – visited the Victoria Falls in 1875 and Matabeleland in 1876 under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Westbeech did not abandon the Western Old Lake Route entirely. Selous tells how in December 1879 he and Laer killed a giraffe and rode home through a terrible lightning storm and just as the storm was lifting they came across the wagon-track near Horn’s Vlei [see map 1 and 7] and on firing a shot heard a reply from their wagon just less than a mile distant. Selous was lying in bed when Samuel his servant said in Dutch: “Sir, there are wagons coming along the big road from Bamangwato [Shoshong] I have twice heard a whip crack.” Selous sat up and listened for some time without hearing anything and concluded Samuel was mistaken. Next morning he saddled up his horse Nelson at daylight and rode over to Horn’s Vlei and to his great joy found two wagons outspanned and the oxen feeding round the vlei. It turned out to be an old friend Frank Watson and he was taking two wagon-loads of goods to Westbeech at the Zambesi.[v]

Selous says for six months he had not seen a white man or spoken English and writes: “How inexpressibly delightful are such meetings in the wilderness…Watson offered to broach a case of brandy in the old style and the orthodox thing to have done would have been for both of us to have remained at Horn’s vlei until the case was finished and a day or two longer to recover from the effects of it. However as I am practically a total abstainer and knew too that poor George Westbeech wanted all the brandy he could get to help him to withstand the deadly climate of the Zambesi valley, I would not consent to my friend’s proposition, so we only had a friendly chat over numerous cups of tea and exchanged news. The following day we parted, but before doing so I was able to supply my friend with a good stock of meat, both fresh and salted, sufficient to last him to Pandamatenka.”

Selous left Shoshong, then commonly called Bamangwato, on 9 April 1888 with two wagons, five salted horses and sixteen donkeys with hopes of crossing the Zambesi river and using Lealui, he calls it Lialui, as a base for a year to collect natural history specimens for museums. Of the journey up on the Western Old Lake Route he writes: “The journey to Pandamatenka may be dismissed in a few words. The country is well known, most monotonous and uninteresting and game at this time of year very scarce. I managed however always to keep my servants and dogs in meat, and amongst other things shot five ostriches (two beautiful cocks and three hens all at this time of year in splendid plumage) and seven gemsbucks. I only once saw giraffe and shot a fine fat cow.” He reached Pandamatenga on 16 May with all the livestock in good condition. “Here I had hoped to meet my old friend Mr George Westbeech, the well-known Zambesi trader, but I found that he was still at the river, some seventy miles distant. I found however my old acquaintance, John Weyers, a colonial Dutchman and all the half-caste elephant-hunters in Westbeech’s employ. From them I heard all the news and to my intense chagrin, learned that the country across the Zambesi was in a very unsettled condition and that there was no chance of my getting through the river.

To a man of my impatient restless temperament this was crushing news and the next morning I saddled up one of my horses determined to ride on and get correct information from George Westbeech. I met him a few miles beyond Gazuma and spent a day discussing the situation with him. He confirmed all that I had heard at Pandamatenka and put things in a worse light still saying that a revolution was breaking out in favour of Marancinyan, in which case it would be months before the country became settled again and that at present at any rate, it was impossible to cross the river with my wagons as all the people were away and there was no one to work the canoes.”[vi]

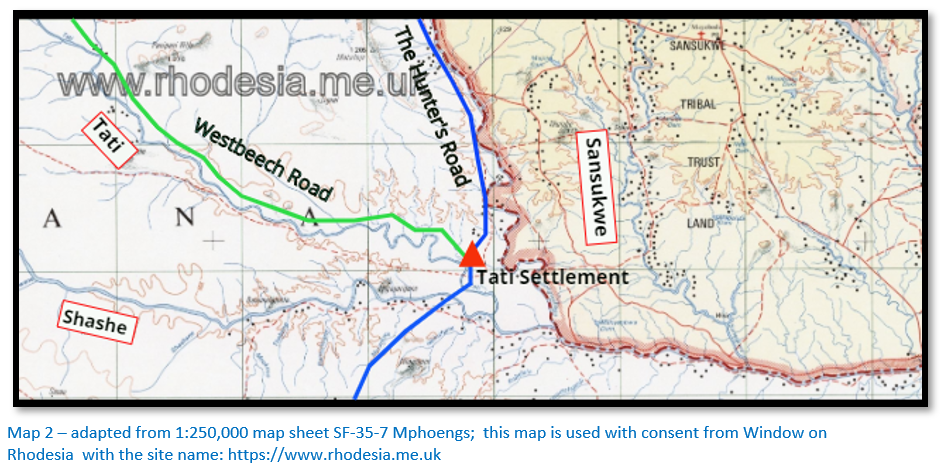

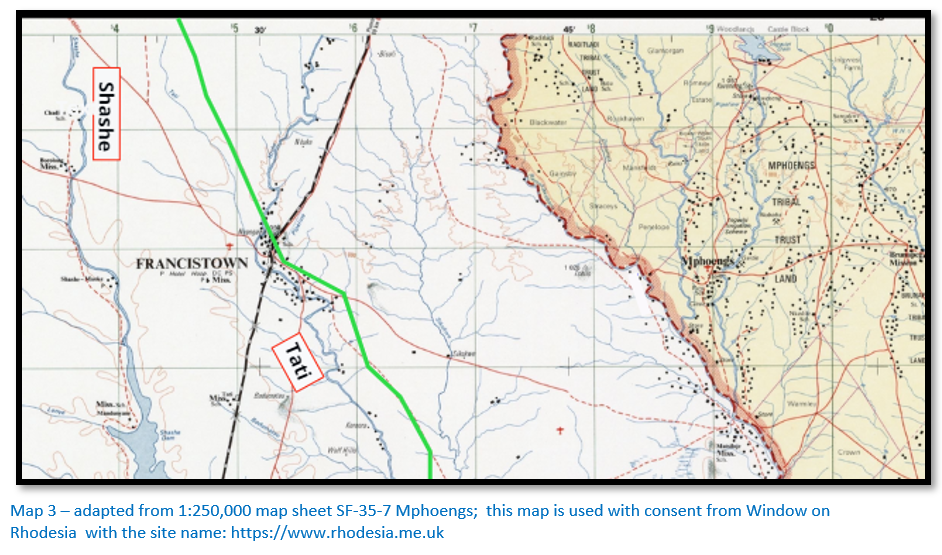

The Westbeech Road

Dr Emil Holub coined the expression the Westbeech Road[vii] although many hunters and travellers simply referred to it as the ‘Zambezi Road.’ The road followed the eastern bank of the Tati river upstream from the Tati settlement soon passing the confluence with the Sekukwe (Little Tati) river near the site of Todd’s Creek, 37 kms (23 miles) upstream from Tati where a minor goldfield was being developed and worked by Australian miners. At the Poort, where the Tati river forced a way through hills 57kms (35.5 miles) from Tati was a drift where the wagons could take a road led to the future sites of Francistown and the Monarch Mine.

An alternative route, but not often used, was to take the Hunter’s Road up to the Ramaquabane river drift following the river on the right bank upstream for about 27 kms (17 miles) and then crossing the Inchwe river to meet up with the Westbeech Road.

The Road then crossed the Tati river and 10 kms (6 miles) further on crossed a ford over the Vukwe river which had a dry bed of granite sand with thick and varied vegetation and surrounding granite kopjes. The Shashe river was reached after a trek of 11 kms (7 miles)

The drift over the Shashe river had steep banks which were tricky to negotiate, but the rocky bed generally had pools of water even in the dry season; many travellers visited and commented upon the dry-stone walls that enclosed the summit of a kopje a short walk from the drift. The right bank of one of the larger tributaries of the Shashe was followed until its headwaters were reached and then the Westbeech Road continued north over the watershed between the Shashe and Maitengwe and crossed the headstreams of both rivers. After the drier region down country many travellers noted the change of scenery; they were in the Mopane veld with a wide variety of indigenous fruit trees and granite kopjes with euphorbia, aloes, and wild fig trees.

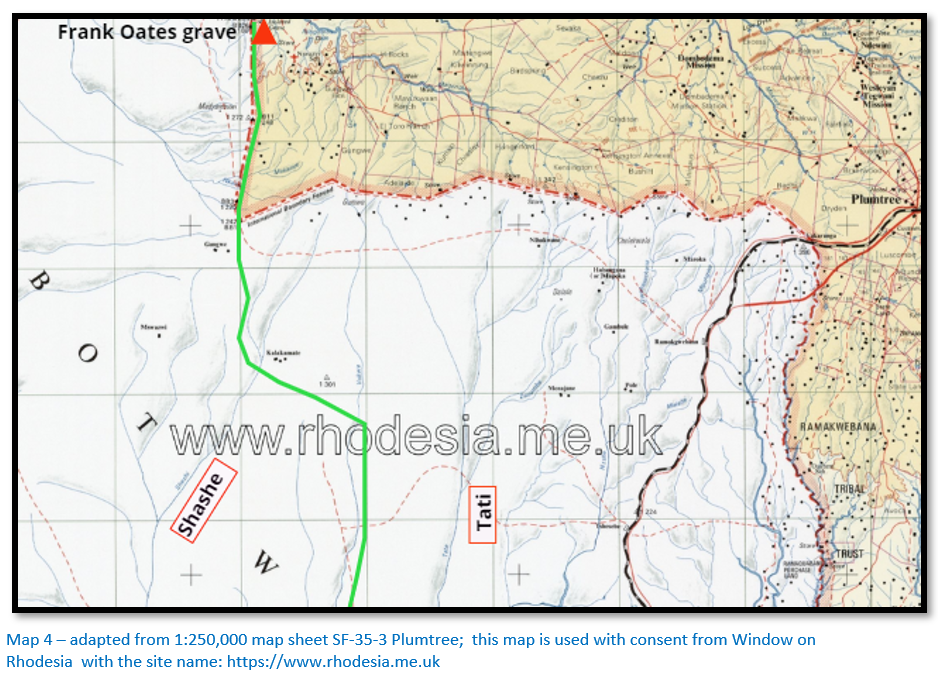

The Westbeech Road now can be identified easily as it follows almost exactly the existing border between Botswana and Zimbabwe almost as far as the Zambesi river.

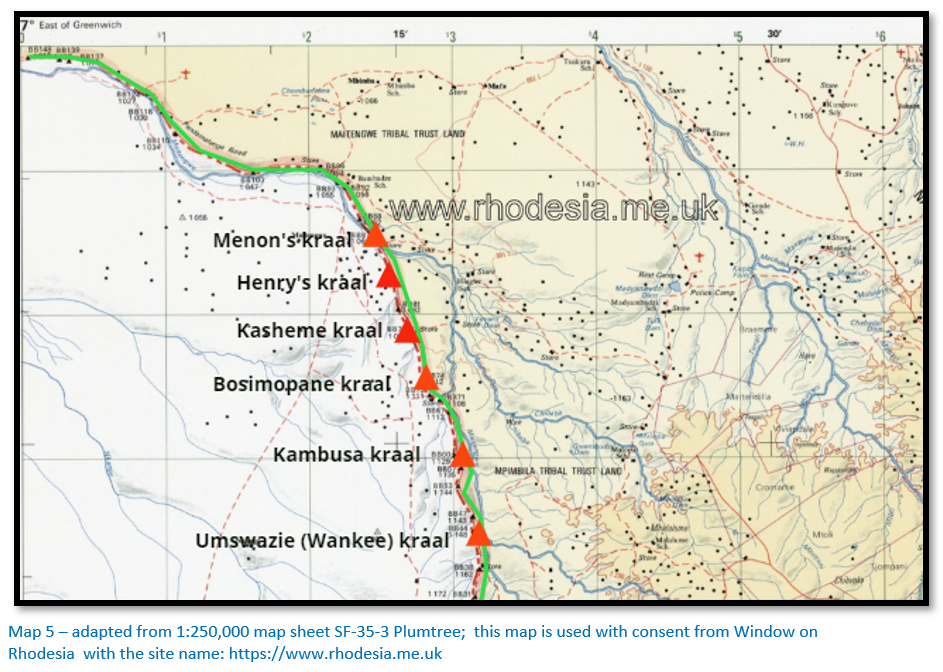

Frank Oates on his fateful journey to the Victoria Falls left Tati on 3 November 1874 and reached Pandamatenga on 27 December and has left colourful descriptions of the journey in his letters and diary, but these are for another article. On their return journey from the Falls Oates complained of feeling unwell at Gerufa on 25 January and despite Dr Bradshaw’s attentions, his condition continued to deteriorate. At Umswazie’s or Wankee’s kraal [map 5] on 5 February 1875 they paid off some of their Bakalanga servants and Frank Oates died the same evening. The ground here was hard and stony; Piet Jacobs who lived at Tati was hunting nearby and advised Dr Bradford to bring the wagons on and he would find a suitable spot for a grave. They met Jacobs about an hour south of the last kraal where he had located a disused native game trap about eight feet deep and Oates was buried here by a small tributary of the Maitengwe river.

The first of a series of Bakalanga kraals all under amaNdebele rule were encountered; Umswazie’s or Wankee’s kraal was 23 kms (14 miles) from the Shashe drift and 138 kms (86 miles) from Tati. Umswazie or Wankee also ruled the next kraal at Kambusa which had about fifteen pole and dhaka huts and a vegetable garden ringed by a thorn fence to keep out the wildlife. Kambusa kraal was the first of a series of kraals where travellers could barter trade goods such as cloth, beads, knives, crockery, blankets, brass wire, snuff boxes and brandy for grain, vegetables and melons; after these Bakalanga villages the upper reaches of the Westbeech Road were uninhabited and there was no food to be obtained between Menon’s kraal and the Matetsi river.

First-time travellers were warned to be watchful of the bargaining powers of Umswazie who was cunning and crafty. The Bakalanga grew a surplus of grain and vegetables in their vlei gardens and were generally inoffensive although they had a reputation for thieving and would sneak into unguarded wagons to steal what they could; gunpowder and caps were particularly prized.

This section of the road generally did not present problems; water supply and adequate pasture for the ox spans were present even during the dry season, malaria fever was absent and there was no tsetse-fly. Lions needed to be guarded against with thorn scherms; temporary thorn fences around the oxen with a watch fire kept alight all night.

During the rainy season from November to March the situation changed dramatically. The vleis became treacherous with the heavy clays of the ground north of the Shashe turning to thick black mud and the risk of malaria becoming prevalent during the rainy season and afterwards particularly along the Maitengwe, Nata and Sibanene rivers.

The road now followed along the west bank of the Maitengwe river and continued for 39 kms (24 miles) from Umswazie’s kraal to Menon’s kraal which was the northernmost of the Bakalanga kraals. In between kraals called Bosimopane, Kasheme and Henry’s were passed. The huts at Menon’s kraal had low roofs and were built around fenced stockades in which cattle and goats were kept. The surrounding land was fertile and sweet potatoes, maize, sorghum and millet, melons and pumpkins were grown. Here the countryside was characterised by Mopane forest, in places which thickened into dense groves and the numerous granite kopjes gradually diminished in size as the road left behind the watershed. Many small usually dry tributaries of the Maitengwe were crossed; they only flowed during a brief period in the rainy season but their banks held pools of water well into the dry season.

Travellers say the quality of the pole and dhaka huts within the kraals and their gardens outside deteriorated as travellers moved north. Menon was the most important of the Bakalanga headman and was about fifty years old in 1876 with a reputation as a great liar and hypocrite although most of the other kraal headmen had similar reputations for petty mischief-making.

George Westbeech was one European whose dealings with the Bakalanga were amicable; Tabler thinks because they all knew he was a friend of Lobengula and had amaNdebele backing. Tabler goes on to say that the Bakalanga had been peaceable farmers and cattle herders before they were conquered by the amaNdebele; thereafter with their loss of independence they became much less industrious and more inclined to thievery.[viii] The huts and gardens in Westbeech’s day grew progressively worse-looking from north to south.

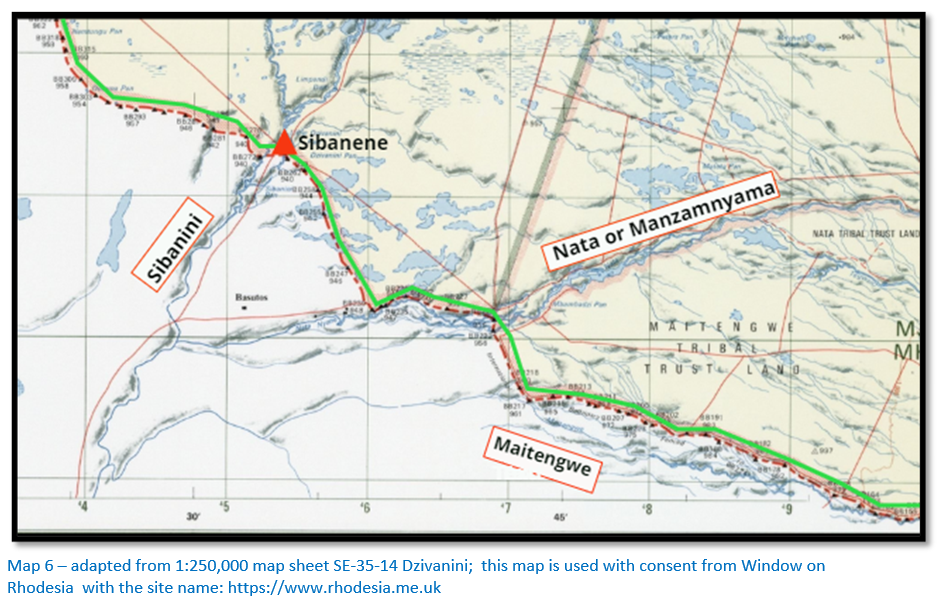

After leaving Menon’s kraal the granite kopjes ceased and the flat countryside became populated with Mopane forest visited by buffalo and giraffe; the Westbeech road lay about 3 kms (2 miles) to the west of the Maitengwe as the elevation of the land gradually decreased. About 10 kms (6.5 miles) on the road crossed the Maitengwe at a drift where the riverbed was sandy and about 120 metres (400 feet) wide. Near the drift was a large hollow Mopane tree under which a Bakalanga chief had been buried and the site held great spiritual beliefs for the Bakalanga.

The road ran on the east bank of the Maitengwe for roughly 40 kms (25 miles) beyond the drift before leaving that watercourse and continued in a north-west direction through sand and Mopane trees for another 27 kms (17 miles) before intersecting the Nata river. The Nata river drift was 4kms (2.5 miles) above the Nata river confluence with the Nata Nyane river and close to the existing international boundary. This route had been used long before the arrival of Europeans by the Bakalanga as a footpath which connected the most reliable water sources; when the surveyors drew up the international boundary between Zimbabwe and Botswana they simply followed on what had always been the most convenient path. Sampson wrote that the Westbeech Road was visible from the air crossing from one side of the fence that marked the international boundary and back again even in modern times.[ix]

The riverbed of the Nata Nyane held many pools of water, some salt and others fresh and attracted multitudes of birds and wildlife including lion, hyena and jackal which made the nights hideous with their sounds. The Nata river generally began to flow about November and was 4 – 6 metres deep (15 – 20 feet) and on occasion flooded its banks, but by March was reduced to a string of pools. The river flows west into the Makarikari salt pans where the waters eventually evaporate.

Beyond the Nata river the road crossed the Sibanene plain which comprised flat Mopane woodland and thorn scrub with ponds scattered at intervals. The birdlife was prolific and where the Mopane forest was thick numerous lions, elephant and buffalo were present. This was amaNdebele territory during the reign of Mzilikazi, but after Lobengula came to power the Bamangwato controlled the western areas.

Once the Nata Nyane river was crossed a further 23 kms (14.5 miles) took travellers to Sibanene pan which had a high knoll on its southern end that was dry in winter but had water lapping at its foot after the summer rains. Fish could be caught in the pan and wildlife was prolific. There were thick groves of Mochwere trees around the pan and the green of the Mopane trees made a refreshing sight for travellers coming from the dry western areas.

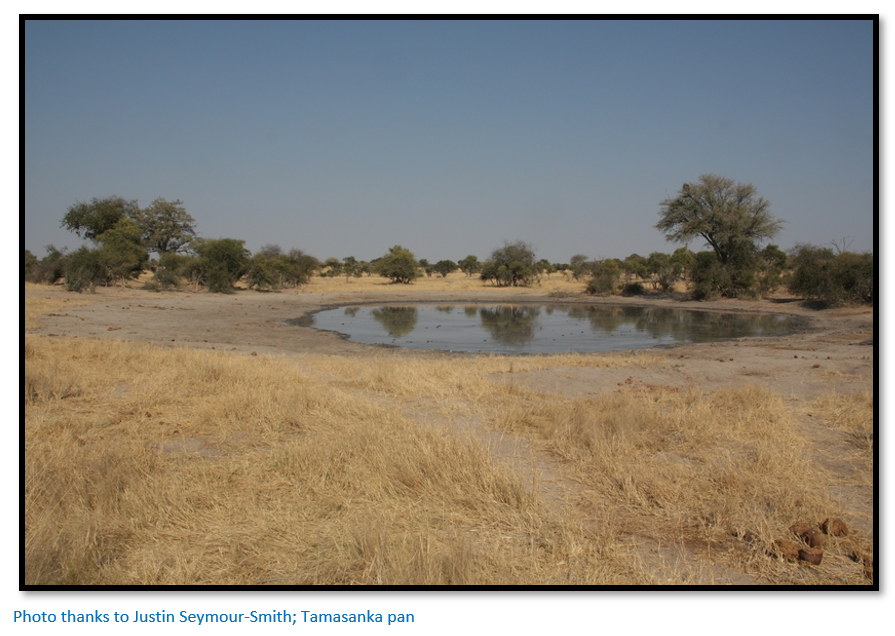

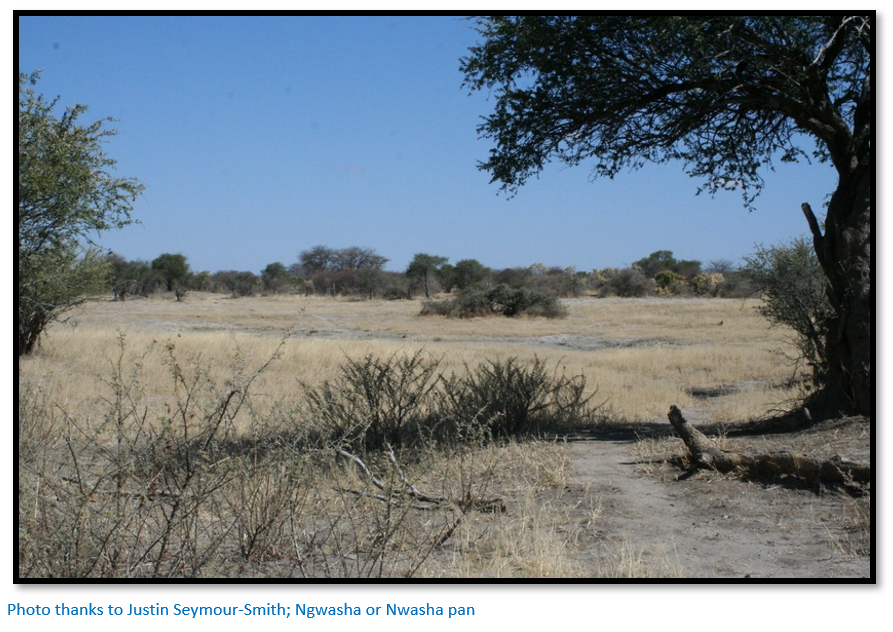

Beyond the pan lay the Sibanene river, usually a dry rivulet followed by 37 kms (23 miles) of dreary travel through sand, dense thorn bush, grass, Mopane forest and dry waterholes; the thick sand making for heavy going for the oxen before Tamasanka pan was reached with its welcoming cluster of permanent pools of clean water.

Nwasha pan was a further 31 kms (19 miles) of hard going through the sand although rhino and elephant were often to be seen in this wilderness of Mopane forest. Here the Westbeech Road was joined by the Western Old Lake Route, the original road to the Zambezi river from Shoshong and the south, the distance from Tati to Nwasha Pan is 350 kms (217 miles)

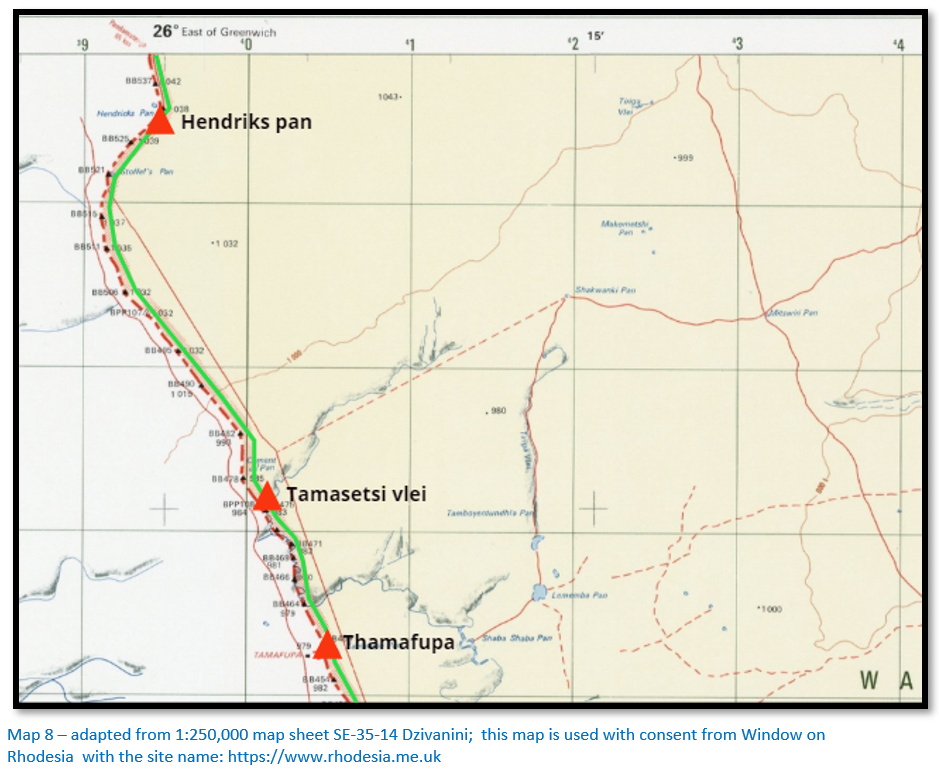

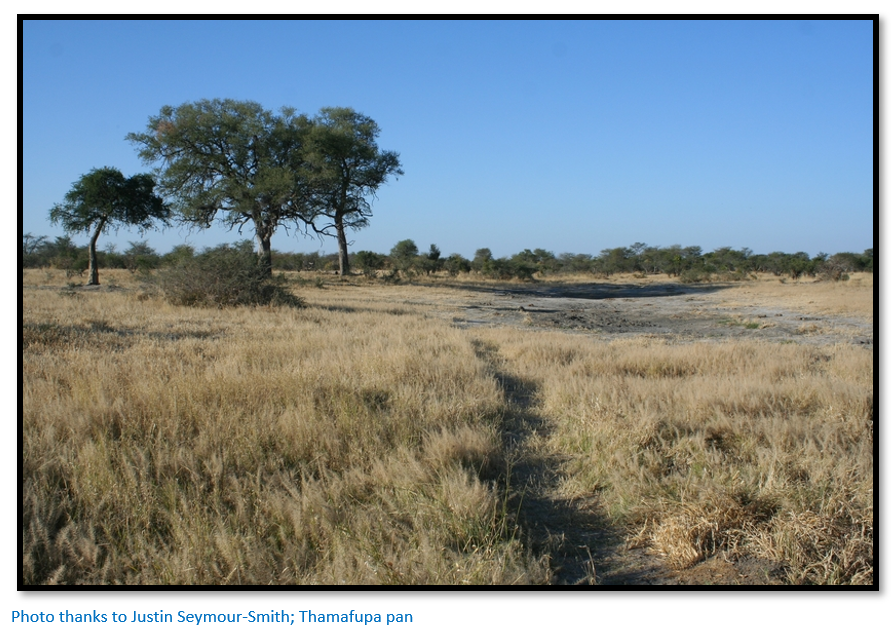

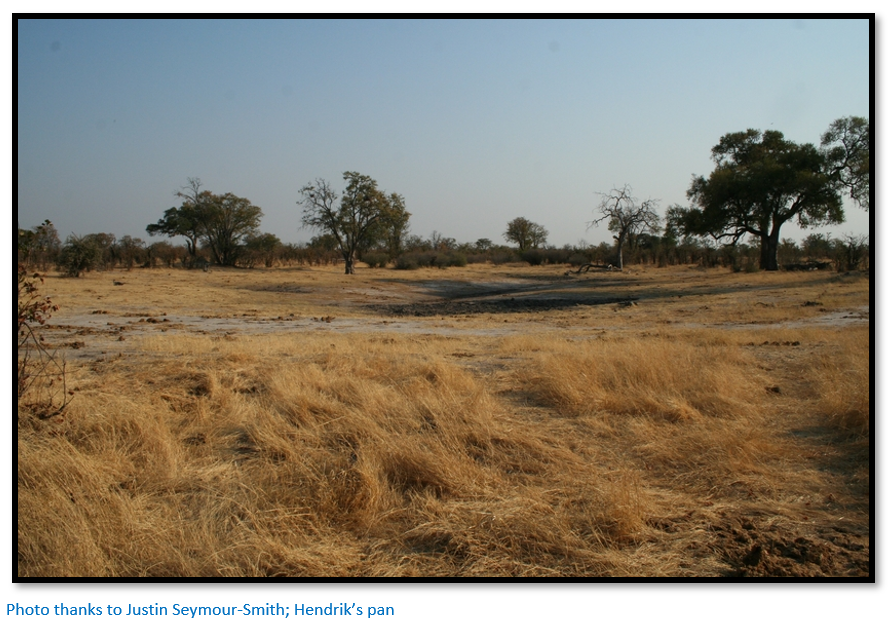

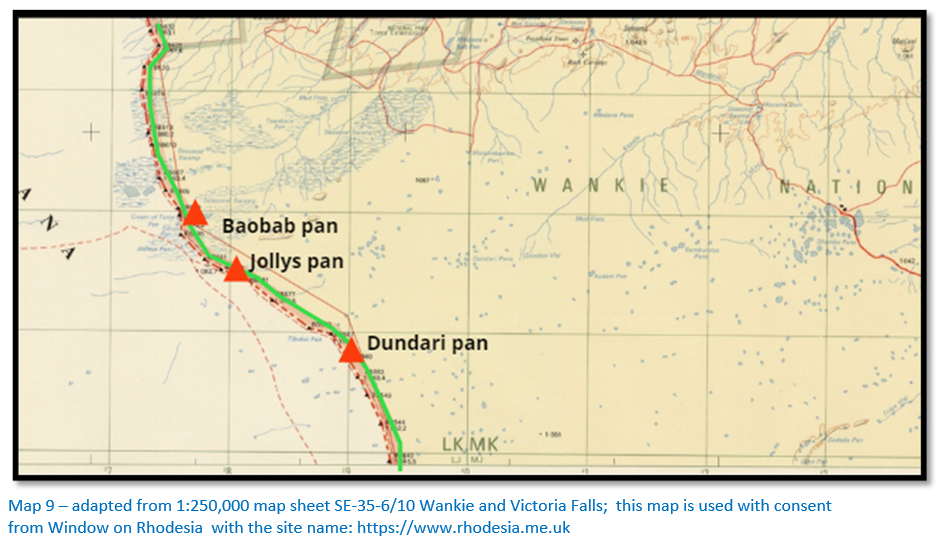

North of Nwasha a string of pans ensured a supply of water for oxen and people throughout most of the year except in the very driest months. This chain of vleis: Gerufa, Thamafipa, Tamasetsi, Hendrik’s pan, Dundari pan, Jolly’s and Baobab pans led onto the Deka river which was 31 kms (19 miles) south of the Matetsi river.

Frederick Barber and his hunting party in 1875 came up the Western Old Lake Route joining the Westbeech Road at Nwasha pan and wrote; “Some Bushmen [Khoisan hunter-gatherers] told us that at a vlei some distance ahead called Jerua [Gerufa] elephants were drinking and that a large troop frequented the vicinity. This good news induced us to pack up and proceed thither without delay. Here we found camped a Dutchman named Meyer[x] a very respectable nice fellow and to our astonishment an old Kimberley friend, Pat Wilkinson. Meyer was on a trading trip, Pat for sport pure and simple.”

The following elephant hunt is described so well by Barber that it is worth recounting. “Our friends the Kirton’s, Jacobs and Meyer now left us proceeding with their whole trek to Pandamatenga, a trading station near the Zambesi. Frank [Fred’s brother] Wilkinson and I were left with our one lone wagon and oxen, two horses, the driver and leader and several Bushmen which we had hired at Klamaghanyani…We had all contributed groceries to one mess and Mrs George Kirton had prepared all our meals for us, making the grandest loaves of brown bread. They also had several milk cows and butter and milk were plentiful the whole way. Black coffee, tea without milk and rough heavy bread and carelessly cooked meat was substituted in the place of our hitherto sumptuous fare. Mrs Kirton was a Dutch girl, and where a Boer woman excels it is in making splendid meals with the roughest materials.

However we determined to make up by hunting and shooting what we had lost in good living, so we set to work and built a strong kraal for our oxen and a scherm[xi] around the wagon. This completed leaving Frank in charge of the camp Wilkinson and I rode out with our hunting boys in search of elephant spoor. We had hired several Bushmen for the trip and one, a Bamangwato,[xii] August, turned out a splendid spoorer. It was simply marvellous the way he could follow the tracks of any animal in any sort of veld.

Within a couple of miles of our camp we found the fresh spoor of a great herd of elephants which we rapidly followed, August leading the way at a rapid swing walk and sometimes at a trot, Wilkinson and I keenly keeping a lookout ahead. We had not gone far when a low whistle from August warned us that the quarry was in sight. Glancing through the stumps [trunks] of the trees we perceived a huge grey mass of moving objects banked up in a great solid phalanx. Elephants! Phew! What awesome brutes!! How grand they looked as they stalked majestically along extending for about two hundred yards. The first time a man sees elephants in their native wilds marks an epoch in his life…

We drew up our horses for a space and contemplated them with feelings of amazement and admiration and with a certain amount of dread at being so suddenly confronted with such a colossal and formidable body of animals. They appeared like a long heavy goods train covered with grey tarpaulins and our elephant guns, up to now so heavy, seemed like popguns. They were moving slowly along, feeding with flopping ears, their great lithe, flexible trunks tearing at the branches of trees and roots. Here was a problem for youngsters who up to a few weeks before had shot nothing larger than blesboks. How we longed to have with us some old veteran hunter to hold our hands and tell us how to attack them.

Perplexed we considered a moment and then decided there was nothing to do but ride up to them and blaze away and take the chances that developed. So we rode slowly towards them unperceived, to within about seventy or eighty yards. Suddenly as if wakened by an electric spark the whole mass of bulls, cows and calves became galvanised and like a rolling torrent swept forward into a swift trot smashing everything in their way. We dashed forward. In my excitement I saw no more of Wilkinson but galloped forward and drew up my horse within fifty yards of the moving mass and watched for a good opportunity to give a good tusker a shot if possible in a vital spot.

They were so mixed up, bulls, cows and calves passing and repassing each other, dust flying, trees breaking and swaying about, sometimes a calf getting knocked over in the scurry, such a chaos of trumpeting and squealing that it seemed impossible to pick out a good one. Several times I was on the point of pressing the trigger at what appeared a good one when another great pair of flopping ears would intervene. The best part of the herd had passed before I could get a good chance when a big cow with good-looking tusks came along on the near side. Taking her well forward in the shoulder I fired and had the extraordinary luck to kill her stone dead with the first shot.[xiii]

I fired the other barrel at another which only accelerated its speed, so quickly reloading I galloped forward knowing the best bulls were further ahead. The bush, although low was thick and difficult to ride through and I found it difficult to get a good shot. I had got well to the front and was waiting for a chance when I became aware of a great crashing on my left and also immediately behind me. Glancing around I found myself almost surrounded by them…

My old horse who had previous experience with elephants did not seem to relish the position any more than I did, so for the next couple of hundred yards the way we annihilated space would have been a credit to a modern automobile. [These events took place in 1875; Fred Barber died in 1919] The elephants were evidently as scared as I was and were making tracks. I galloped after the retreating sounds and had just got in sight of the rear of the mob, consisting mostly of cows and calves, when I descried, sneaking away at a tangent to my left, an enormous bull with splendid tusks.

Here was an attractive and negotiable position, so I hurried after and got up to within forty yards of him and was just about to dismount and give him a shot in his rump when he became aware of my presence and swerved round. As he did so I gave him a good shot in his left shoulder. With a screech that would have awakened the dead he charged me necessitating another masterly retreat. In looking back while galloping away I ran over a young mopani tree which nearly unhorsed me. My right leg being thrown back across the rump of my horse. It was with some difficulty (carrying a heavy gun) that I regained my saddle. If I had fallen off, eventualities would probably have been unpleasant. After a fruitless chase he stopped, when so did I. We contemplated each other for a moment, then he turned around and began making off again. As I got nearer to him, he turned again, raised his trunk and shrilly trumpeting, charged forward again. I aimed and fired at the middle of his chest. He rushed forward a few steps and came down on his knees, dying in a prone position with the points of his tusks embedded in the ground. Jubilant! I rode up and examined him. He was a grand big chap and his tusks, weighed later, scaled just under forty pounds each.

…I saddled my old charger, for whom I entertained the greatest respect. He had shown business instincts that astonished me. I fired a couple of shots and bye and bye some boys turned up and after much shouting and shooting Wilkinson, hatless, stirrup-less, his bridle broken and a little of his shirt still hanging over his half-naked body…Red in the face with het and exertion and passion, he cursed everything an inch high and swore with such a vocabulary of voluminous and brilliant oaths…

A midnight thunderstorm would pale beside the dark looks with which he surveyed me. If a glance could kill, I should have become a cremated corpse and his temper was not pacified when I told him that I had another fine one lying some distance off. I chaffed him saying I was astonished that he, having been so much longer in the bushveld, hadn’t shot at least half a dozen…we now set to work to chop out the tusks, a job which none of us knew anything about and which consequently took us the whole day to accomplish and could have been done in half the time if we had understood dentistry.”

Barber again; “Hunting in the neighbourhood for four or five days and finding no fresh elephant spoor we continued our journey towards the Zambesi passing the fine pools of Thamafipa and Tamasetsi and a little further north The Big Baobab Tree well-known to all travellers passing that way by its enormous girth. [Fred Barber and his companions met Alfred Cross[xiv] and W.A. Browne at Gerufa on 21 July 1875 after Lobengula ‘gave them the road;’ Cross and Barber measured this tree] Its stump was nearly eighty feet in circumference at the ground and although to outward appearances quite healthy, the inside had rotted out leaving a comfortable room in which travelling natives slept about ten feet in diameter. A Dutch hunter with his wagon and family joined us here and travelled with us.

Next day while out hunting a young Dutchman lost himself getting back to the wagons quite accidently next afternoon quite exhausted with hunger, thirst and fear. He was in a deplorable condition minus his gun, cartridges, jacket, hat and boots; had been and still was in an utterly demoralized state. He had seen lions, elephants, rhinos and all sorts of fearful animals. Most of them had chased him from which he had only escaped by climbing trees to facilitate which, he had discarded his boots. He had fired away all his cartridges in hope of being heard at the wagons and at wild animals. Throwing away his gun he had fled panic-stricken losing in his flight his jacket and hat. It was several days before he recovered his self-possession and equanimity and his gun of course was never recovered.”[xv]

Cross says there were four families of Boers standing at Hendrik’s vlei when they arrived there on 7 August.

Richard Frewen’s journey from Shoshong to Pandamatenga in 1877

The dates give some indication of the typical time a hunting trip took with stops for excursions into the hunting veld often when a number of wagons came together and the hunters combined their resources.

Correct name | Frewen's name | |

06-Jun | arrived at Shoshong | Bamangwato |

13-Jun | left Shoshong | |

14-Jun | Letloche | Gehlutsi |

16-Jun | Mukwe, a sand river | Moko |

18-Jun | Sekoswe, a sand river | Soakassa |

19-Jun | Mersa | |

20-Jun | Makwa | Maqua |

24-Jun | The Berg | |

28-Jun | Shuane river | Mapani sluit |

30-Jun | Nata River or Madsiara drift | Nanta river |

05-Jul | Nekwati pan | Mokolani pan |

06-Jul | Horn's vlei | |

07-Jul | Matlamanyane | Khamainyame |

11-Jul | Nwasha pan | Nwatcha |

12-Jul | Gerufa | Jerufa |

16-Jul | Tamafupa | |

18-Jul | Tamasetsi | |

20-Jul | Stoffel's pan | |

21-Jul | Hendrik's vlei | |

31-Jul | Baobab pan | Moani |

02-Aug | Deka | Daka |

09-Aug | Pandamatenga | Pandamatinka |

[The article Richard Frewen, the man who annoyed Lobengula and the consequent death of the Colonial Government Emissaries on their way to the Victoria Falls is under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Thomas Leask arrived at Deka on 4 June 1868 and wrote: “Inspanned at sunrise and got to Deka before mid-day where we found Vanderberg. Here is a fine stream of water: it is quite a delight to see such a thing again and the luxury of a drink of clear crystal water after being compelled to drink a decoction of mud, urine and water – this, with the luxury of a pleasant bathe, is grand. Give the drunkard his spirits, the tippler his beers and ales, but give the African traveller a stream of clear pure water.”

On 8 June; “The last three days have been passed in idleness with the exception of a little hunting and fishing. The Bushmen [Khoisan hunter-gatherers] returned yesterday and report the country to be very dry. Consequently we inspanned this morning and trekked on the Fall road as far as Pandamatinka [Pandamatenga] where we arrived shortly before sundown. The road goes about a day further, but we have decided to halt here because some hunters got their oxen stuck by ‘fly’ last year at the old stand-place ahead.”

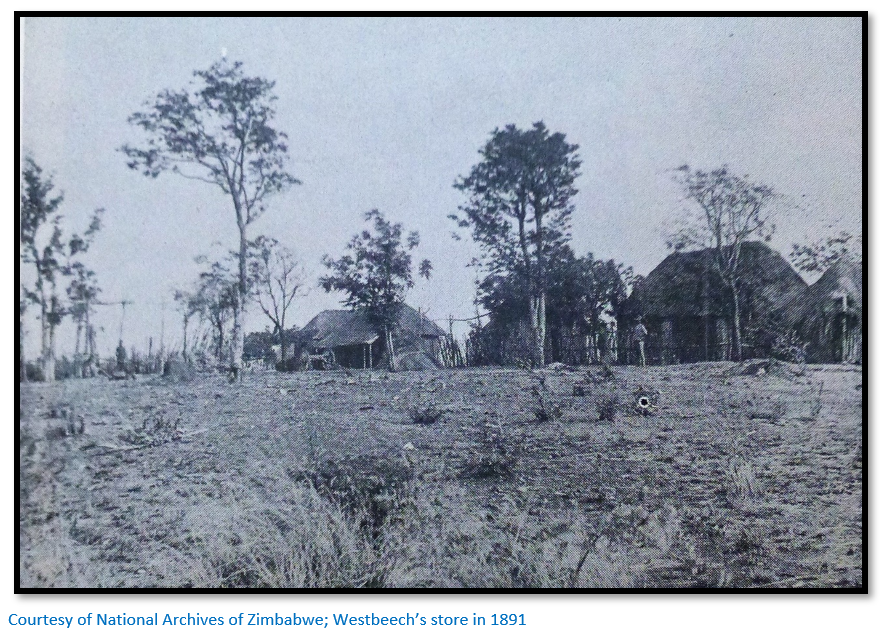

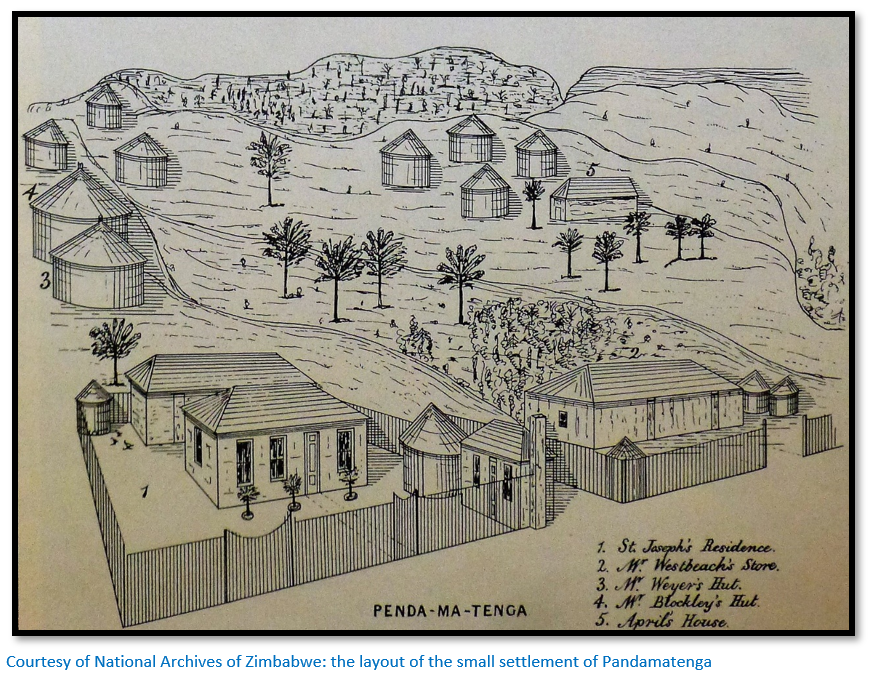

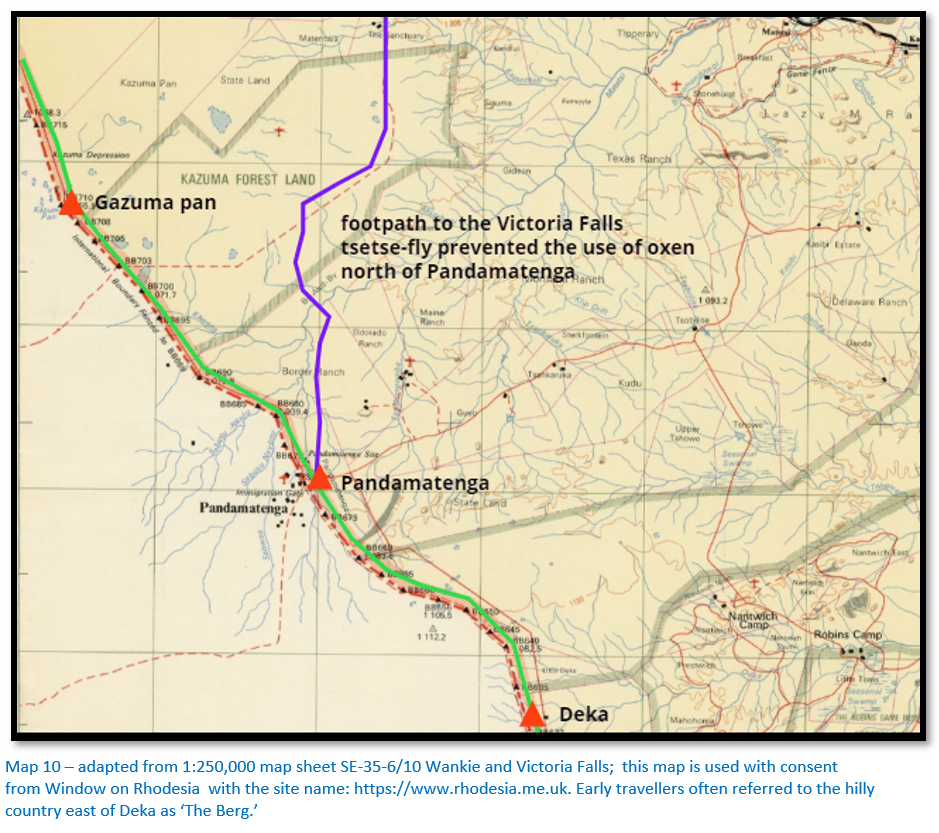

Pandamatenga

The Matetsi river had been a stand place for ox-wagons as early as 1867. Before that year, the absence of tsetse-fly had allowed oxen and horses to be taken even further north but post-1867 this point became the limit for domestic stock as the fly moved southwards. Westbeech established his headquarters on a small hill not far from the headwaters of the Matetsi river at Pandamatenga; in time this became a renowned spot for all hunters, traders and explorers in the Far Interior.

Since most of the trade that Westbeech carried out was in Barotseland, north of the Zambezi river, he chose the headwaters of the Matetsi river for the following reasons:

- Water was plentiful all year round

- It was a fairly healthy spot even during the rains when malaria was most prevalent

- No tribe claimed strong ownership of the area although the amaNdebele conducted raids

- Tsetse-fly to the north forced traders to transfer their goods from wagons to the backs of porters and carry any goods 97 kms (60 miles) to Impalera Island.

Tabler states[xvi] that Pandamatenga was dominated by Westbeech for many years and remained for about thirty years the major settlement for traders and hunters north of Tati. Tabler states Baines, Chapman and Leask visited Pandamatenga before Westbeech; other travellers who visited included Holub (1875) Pinto (1878) Arnot (1882) Schulz and Hammar (1884) Bethel (1886) Starkey (1887) Bertrand (1895) and Reid (1899) but this is not a complete list.

Westbeech was not the first at Pandamatenga; traders had used the small rocky hill just north of the first headwater stream of the Matetsi previously, but Westbeech was the first to make it a permanent settlement and he had a high thorn fence constructed around pole and dhaka huts and a warehouse. The oxen needed to be protected as lions in the area were a nuisance. The site became a destination for European travellers and for local native hunters wishing to sell ivory, ostrich feathers and animal skins. His agents George Brockley and Dr Benjamin Bradshaw were permanently stationed at Pandamatenga, Westbeech lived here when he was not travelling south or in Barotseland.

Bulpin[xvii] says Pandamatenga was named after a renowned elephant hunter named Mutenga who used the spot in a grove of Mpanda trees (Lonchocarpus capassa or rain tree) near the source of the Matetsi river as a temporary hunting base. Early Europeans also began to use it as a base calling it Mpanda Mutenga and Bulpin says Mutenga began selling ivory to them. When this came to the ears of Lobengula the Nyamandhlovu regiment ‘meat of the elephant’ was sent to wipe out Mutenga and his family.

Other sources claim the name is derived from panda meaning ‘market’ and tenga meaning ‘to bring.’ The trading station under Westbeech always operated with a European left in charge to organize the movement of wagons and oxen and the parties of mixed race hunters leading Africans on expeditions into the surrounding country to hunt elephants. Westbeech generally supervised the overall operations and took part in any activities when required.

Blockley ‘little George’ who worked for Westbeech from 1871 until his death in August 1887 was the best known employee, a good-natured and amiable man who travelled extensively in Barotseland. Tabler says he was also on the best of terms with Sipopa and Lewanika, as well as Wankie and all the other minor chiefs.

Dr Bradshaw joined Westbeech in 1872 having previously worked as a doctor on a steamship and at the diamond fields and then came to the Zambezi. Like Blockley he was friendly and hospitable, a skilled doctor and good cook, his hobby was collecting birds and insects. His favourite joke was to warn guests about eating too much and then to enjoy what they left on his advice. In 1878 he was described as a small man with blue eyes, short hair and a light-brown beard wearing a linen shirt, cotton socks and veldskoens with a bowie knife on the belt of his trousers.

Christoffel Schinderhutte was another employee and Alexander Walsh who had been Francis’ storekeeper at Shoshong spent many years at Pandamatenga; visitors noted he was still present in 1899 a decade after Westbeech’s death.

A number of other Europeans and men of mixed race were employed as wagon-drivers, storemen and elephant hunters by Westbeech including Jan or Klaas Afrika and Henry Wall who became his brother-in-law.

Sampson says: “At the peak of his operations he [Westbeech] had no less than 400 employees consisting of Europeans. South Africans of mixed race, Africans and Bushmen [Khoisan hunter-gatherers] from the Kalahari Desert.”[xviii]

Westbeech established a cemetery south of his settlement at Pandamatenga which was the first site that travellers passed on their way north and a constant reminder of the dangers of malaria and hunting big game. Over the years the cemetery contained at least twenty-three graves.

Barber writes: “Without further mishap we arrived at Pandamatenga. This was the end of our long journey northwards as far as our wagons were concerned as beyond this was tsetse-fly country and our further journey to the Victoria Falls would have to be made on foot. Pandamatenga was a trading station where a great deal of ivory, feathers, etc., were traded from native chiefs living along the Zambesi river and beyond it. Here we found a good many traders with their wagons and some of them had put up temporary shops built of poles and straw, grass or rushes. One man was down with malarial fever having contracted while trading in the Barotse country and we had the unpleasant task of burying him a few days later. From all reports there seemed little chance of finding elephants anywhere near here so we determined to make our visit to the Falls at once and then return to Tamafupa which seemed the best country for elephant hunting.”

Alfred Cross records that the trader Jolly was carried into Pandamatenga extremely ill with fever on 11 August. He died during the night and was buried in blankets because there was no wood for a coffin the next day. His trade goods were sold the next day; Jolly’s Pan was named after him.[xix]

Many travellers noted the frequent use of alcohol at Pandamatenga which was really unsurprising considering the life of isolation and hardship that the men endured; hunting elephant was a dangerous pastime and fever cut many lives short so they partied hard on the infrequent occasions they bumped into old friends. Richard Frewen made the following notes in his 1877 journal on the subject:

17 Sept – Among other things that had gone wrong was one ox and one of my Scotch collie dogs was dead. The Bushman whom McKenny had engaged had bolted after breaking into my hut. Oxen extremely poor. Sent them off to Pandamatinka [Pandamatenga] McKenny came in. His other boy whom he had engaged against my wishes had bolted with my elephant gun. Rain fell, the first, but not enough to do much good. Rode over to Pandamatinka where I meet Westbeach [Westbeech] Dr Bradshaw, etc. Most of them very drunk.

18 Sept – Found my brandy casks had been nearly emptied of their contents, over 60 bottles had been stolen. This was bad as they were in the charge of white men. I managed to get most of my things together and started the wagon off early and soon after followed myself. I never saw such a hell upon earth as the place was; three wagons had arrived from below and what with the sorting of goods, selling of ivory and everyone being more or less drunk, I was glad enough to get away. I engaged a boy to drive my wagons out in the place of J. McKenny as I could not stand his thieving and lying any longer. Got back to Daka [Deka] in the afternoon…

19 Sept – Westbeach, Nicoll, Collison and others came over from Pandamatinka, all still very drunk…

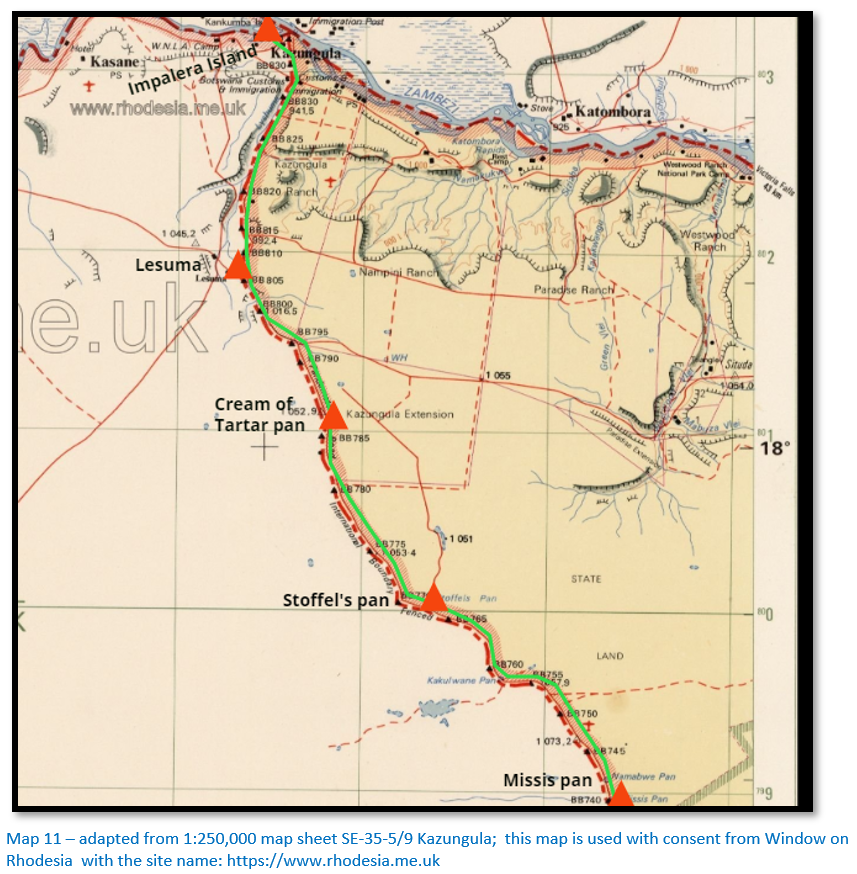

Pandamatenga to Impalera Island

Between Pandamatenga and Impalera, the Barotse outpost on an island at the confluence of the Chobe and Zambezi rivers the Westbeech Road crossed the Khazuma Depression and travellers camped at Gazuma pan, Missis Pan, Makolani Pan, Stoffel’s Pan, Cream of Tartar Pan and finally at Lesuma Valley. All travel to both Impalera (97 kms) and the Victoria Falls (80 kms) would have been on foot with the aid of porters

Selous writes that in there were two amaNdebele attacks on the Batauwani at Lake Ngami with the first in 1883 being only partially successful and the second in 1885 a complete disaster as the Batauwani received news of the impending attack and took their cattle and people beyond the Botletle, now Boteti river and ambushed the amaNdebele with their breech-loading rifles. Many amaNdebele were shot, others drowned trying to cross the Botletle and the survivors were forced to retreat across 640 kms (400 miles) of uninhabited desert with hundreds dying of thirst, starvation and exhaustion.[xx]

One portion of the retreating impi travelled home by a more northerly route than they came and surprised one of Khama’s wagons with a BaNgwato hunter and a Khoisan guide. The hunter managed to escape by catching one of the horses and riding away bareback and eventually reached Shoshong. The Khoisan was forced to guide them to Pandamatenga and when they reached the Westbeech Road at Gazuma vlei 23 kms (14 miles) north of Pandamatenga he was assegai’d as they had no further use of him. Selous was shown the spot in 1888 where his remains had lain at the foot of an ant-heap beside the wagon-track.

At the time one of Westbeech’s elephant hunters, Jan Afrika was living at Gazuma with Charley, a local native lad later employed by Selous and several families of Khoisan. As the amaNdebele came filing out in long lines to Gazuma the Khoisan ran away except a few who took refuge in Africa’s hut and a Khoisan man and woman and young baby who stayed with Afrika. Afrika has shot an eland the day before and the meat was hanging up around his hut. The amaNdebele helped themselves to the meat and some corn, but left Afrika and Charley knowing they were Westbeech’s men.

When the inDuna was told the Khoisan had run away as soon as they saw the amaNdebele he became angry and said: “not a dog of them should have lived if he had seen them.” Then he killed the baby and woman with one thrust of his assegai and wounded the man, who managed to run away as the other amaNdebele were too busy seizing the eland meat.

Pandamatenga to Victoria Falls

Barber continues: “Leaving our wagon, oxen and horses in charge of our most trustworthy boys we started on our long walk to the Zambesi being about sixty miles distant[xxi] We were joined by a trader ‘Sandy’ Anderson and another white hunter Alfred Cross making our party of whites five[xxii] with about thirty native carriers carrying our groceries, spare ammunition and blankets. We travelled north down an open valley, interspersed with trees. Towards evening we got among hills with open valleys between. It was pleasant to get out of the monotonous everlasting bush that we had been travelling through for so long into hilly country with patches of open and bush and plenty of clear streams of water.

This country abounded in objects of interest to a naturalist. I was pretty well posted in the science of both birds and butterflies, but up to now had been too busily occupied in shooting. But here were numbers of, to me, new varieties of butterflies among which the Acrididae were strongly evident in many varieties. Here was an opportunity of immortalizing myself…So I improvised a net and for the nonce became a butterfly catcher to the great amusement of my companions and the astonishment of our carriers. I took a good many beautiful specimens and felt sure that several at least were new to science, but sad to say, on sending my collection later to Roland Trimen[xxiii] of butterfly fame, I found I was just too late. A Mr Oates had visited the same spot a year before and cleaned up all its rare varieties.” [see the article on Frank Oates Expedition to the Victoria Falls under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Pandamatenga to Wankie’s kraal

Chief Wankie’s kraal was on the north bank at the confluence of the Zambesi and Deka rivers [For the location of Wankie’s kraal see the map in the article Thomas Leask’s two journey to the Zambesi in 1868 and 1869 under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Selous says they walked from Wankie’s to Pandamatenga in 3 days: “about the shortest time on record I think, five days being considered good time. On the third day we did exactly ten hours actual walking (by my watch) at a great pace, and Paul, Charley and myself with three of the natives got in just at sundown, the remainder not arriving till midday the following day.”

George Cobb Westbeech

Sampson tells us that Joseph Westbeech, George’s grandfather was a distinguished Royal Navy Commander and that there is a considerable resemblance between his career and that of Horatio Hornblower, the naval officer created by C.S. Forester in his 12 book series of a naval officer during the Napoleonic Wars.[xxiv] George’s father, also Joseph, was a master mariner but became a customs officer and George was brought up at Toxteth Park, Liverpool and close to the Mersey River where many of the Royal Navy’s fighting ships were built. Joseph married Elizabeth Copp and George was born on 5 October 1844 and named George Copp Westbeech after his maternal grandfather.

His father died in 1848 and his mother was forced to move to a smaller house with her mother and ran a small shop. His brother Joseph died aged two from enteritis in 1849 and his mother died in 1852 from tuberculosis. Aged just eight he only had his maternal grandmother for support and under her guidance and to her great credit by 1862 Sampson states: “At the age of 18 he had developed a pleasant well-mannered, gentlemanly and genial personality.”[xxv] He clearly only had an average schooling but a good natural intelligence and an ear for languages…he spoke many African languages which helped him in trading activities and encouraged his acceptance by the many different native tribes in the African interior.

He left England in 1862, still not yet eighteen years old but within a year moved north to Matabeleland with no material assets but a warm and engaging personality which made him the trusted friends everywhere he went.

Sampson quotes F.C. Selous: “a man of most loveable disposition and many fine qualities…Once when walking with G.W. down to the Zambezi, he said to me, pointing to a toothbrush fixed in his hat, ‘that’s the last link between me and civilisation old man.’ Soon afterwards we were sitting in a native village, the guest of the headman and his friend and relations, and Westbeech was no longer a white man, but had become to all intents and purposes an African. As I watched the beer pot going round and listened to my friend talking to his hosts with the utmost fluency in their own language, every now and then gravely taking snuff with one or other of them, I marvelled at his dual nature. G.W. at least was absolutely happy in his adopted country and often told me that he had not the least desire to return to England. Nor did he ever do so. From Kazungula to Lealui, a distance of some 300 miles, I don’t think there was a village along the Zambesi, in which there was not at least one lady who called him husband.”[xxvi]

Sampson quotes from Mr W.V. Johnstone of Potchefstroom in 1929 in relation to Westbeech’s character in which he was always mild, gentle and reliable and polite: “These men of whom I write elevated the white man in the minds of the native and caused him to understand there were others, of better calibre than the wretched specimens of the race which they had hitherto come in contact with. George Westbeech was of such; his word was his bond. He was a mild man in many ways, but nevertheless a brave and intrepid hunter.”[xxvii]

Sampson says that with the hard life with monotonous food, mostly maize porridge spiced with Worcestershire sauce when available and game meat, far from family and friends, often ill with fever: “it is no wonder that most of them took to drink as their one solace. Indeed the non-drinking interior man was the extreme exception”[xxviii]

Matabeleland from 1863 - 7

Westbeech arrived in Matabeleland for the first time in 1863 and spent the next four years buying ivory and so pleased Mzilikazi that he was allowed to drive the King’s wagon and serve himself first when eating with the King. He was brave and friendly and liked by everyone because of his offers of assistance. Everywhere he lived he made sure he spoke the local language and became fluent in isiNdebele, Sechuana, Sesutu and others – this was a great advantage in his trading with the various tribes. Selous says of him: “one of those many English and Scotch men whose innate love of enterprise, combined with indomitable perseverance, has led them to try their fortune in every unexplored corner of the globe.”

Mashonaland in 1868 with Lobengula and an impi

George Phillips and Westbeech went to Mashonaland in 1868 leaving the Hunter’s Road at the Umniati, now Munyati river and riding across to the Mwenezi Hills to the east before coming back and accompanying an AmaNdebele impi on a raid beyond the Hunyani now Manyame river. Lobengula accompanied them in an ox-wagon and after crossing the Manyame they travelled a further two days to the east and reached Golatima’s kraal, the brother of Hwata in the current Mazowe/Concession/Glendale area. The amaNdebele drove Hwata out of his mountain kraal while Phillips and Westbeech trekked down the Mazowe river until threatened by local Mashona tribes. As neither kept a journal nor made any maps the country remained unknown until Selous surveyed it during 1882. On their return they learned Mzilikazi had died, but Mncumbatha permitted them to stay in the country until Lobengula’s succession in 1870.

Lobengula appointed amaNdebele King in 1870

Westbeech was one of those who attended Lobengula’s succession ceremony[xxix] when he was brought from his kraal to Mhlahlandhlela on 22 January 1870 with a large escort of izinDuna and between seven and nine thousand warriors were at the capital. The next day Lobengula was prepared with magic rites and the day was quiet. Those Europeans present consisted of Will Hartley, H. Grant, R. Hudson, John Lee, J. O’Donnell, G.A. Phillips, W. Sykes, T.M. Thomas, W. Thomas and G. Westbeech On the 24 January a dance of hundreds of warriors in battle dress took place chanting “in full deep chorus” as individuals ran out to shout praise names and pledge their loyalty. Oxen were then slaughtered on Lobengula’s orders as his first official act and the next two days were spent in feasting.

By 26 March Westbeech was at Mangwe and then left the country for Hopetown to buy more trade goods. Hopetown had been a quiet farming area until the Eureka and Star of Africa diamonds were discovered there in 1867 and 1869; now the town in the Northern Cape and near the Orange river was bustling with diamond seekers. The goods were taken to Pandamatenga and he was back at Mangwe on 12 August with four wagons and George Gordon[xxx] Mohr and Cluley on the way to Shoshong. They parted at the Bamangwato town with Westbeech going south.

Trading in Barotseland from 1871

Westbeech (Joros Montuna; ‘big George’; Selous calls him ‘Georos’) left his business partner Phillips in Matabeleland and with his employee George Blockley ‘little George’ took three loads of trade goods to open a trading business in the Zambesia region. On his first trip he used the Western Old Lake Route which skirted the Makarikari salt pans, but thereafter he used the route from Tati which had been travelled by Leask, Coverley, Ziesmann, Mohr and others up the valley of the Tati river to the headwaters of the Shashe river and north to the Maitengwe river.

Sipopa Lutanga, King of the Barotse or Lozi people (1864 – 76) came to Impalera island on the confluence of the Chobe and Zambezi rivers to meet him and although Westbeech has no initial plan to cross the Zambesi Sipopa had all his goods taken over the river to Barotseland and treated him as a friend. Westbeech became a confidant and councillor of Sipopa on his first visit and the King insisted on an extended stay for eighteen months. During this time he travelled down to the Victoria Falls and was given the freedom of the country; a unique privilege for a European until 1877 and the right to hunt for elephant anywhere in Barotseland.

When he inspanned his wagons to leave the country Sipopa was so upset he gave Westbeech a large gift of ivory which Westbeech finally sold in Shoshong for £12,000. This success and the realisation that he had virtually a trade monopoly with the Barotse or Lozi tribe made him decide to continue trading in Barotseland in view of the profits to be made. He brought in better and cheaper goods than the Portuguese traders of mixed race from Angola and the Swahili Arabs from the east coast.

Throughout his long stay in the country he continued to act honourably and was trusted by Lobengula and Sipopa. Until 1877 when trade declined as a result of the civil disturbances in Basutoland following the death of Sipopa he managed to bring out between ten and fifteen tons of ivory for sale at Shoshong each year. The price of ivory was about seven shillings per pound when Westbeech started although the price steadily increased over the decade as the elephant were gradually shot out in Matabeleland.

Prior to Westbeech arriving, King Sipopa traded mostly with mixed-race Portuguese from Angola who had the habit of giving the King all their goods, including their own clothes, then taking whatever ivory he chose to give them. When the first Europeans came across the Zambezi he expected them to do the same and treated them badly when they would not. William Horn persuaded Sipopa to barter goods in 1868 and paved the way for Westbeech who arrived in 1871. Horn died at Hope Fountain on 5 October 1875 and his son worked for Westbeech at Pandamatenga in 1885.

Westbeech gained King Sipopa’s confidence to such an extent that he was granted extraordinary trading and hunting privileges and by 1877 all other traders had been ousted from Barotseland. However he was still forced to give Sipopa a present with each annual transaction and his demands grew ever increasingly costly. In the 1870’s the most acceptable trade items wanted by the Barotse were milk-coloured, blue and abumgazi beads, European clothing, smooth-bore guns, powder and lead.

Cutting the Westbeech Road in 1872

Westbeech cut the road from Tati when he returned to Barotseland in 1872 that was named after him. Westbeech may also have been the first to vary the route by using the Ramaquabane river from Tati and thereafter the entire road from Pandamatenga to Tati was improved and maintained by Westbeech and his employees for the next seventeen years until 1889.

King Sipopa gave Westbeech and Brockley permission to travel and trade in the Barotse Valley in 1872 and 1873.

1873

Westbeech was at Shoshong in April 1873 and left with Dawnay, Moore, Humphreys and Stroomboom on the Hunter’s Road. A wagon broke down at the Mhalapshwe river and a replacement was sent from Shoshong. They turned north at Tati but were delayed by wagons breaking down and oxen dying from lung disease before reaching Gerufa. [map 7] Schinderhutte, another employee, came with spare oxen from Pandamatenga to find out the reason for the delay and they met at Gerufa on 13 September 1873 and left the next day.

1874

During late 1873 – 1874 Westbeech was Sipopa’s guest at Sesheke and he travelled and traded throughout the period and only left in December

1875

He was back at Pandamatenga in January 1875 and soon afterwards started south with Bradshaw, Frank Oates and Mackenna. They reached Gerufa on 25 January and Oates died north of Umswazie or Wankee’s kraal on 5 February. A friend called Gilchrist brought a memorial stone from Pietermaritzburg in Natal which became a well-known feature to later travellers. [See the article on Frank Oates under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] Westbeech rode off to Bulawayo the same day leaving his companions to continue onto Tati where they were re-joined by Westbeech, Phillips and Fairbairn before continuing on towards Shoshong.

Westbeech, Phillips and Bradshaw arrived at Zeerust in the Marico Valley and on I June 1875 Westbeech married Cornelia Carolina Gronum whose parents lived on a nearby farm. Phillips was best man at the wedding. The honeymoon to the Victoria Falls in which the couple were accompanied by Mr and Mrs Francis mixed business with pleasure as the party went to the Victoria Falls from 13 - 24 Setember and then visited Sipopa at Impalera to conduct some trade. Westbeech and Francis were at Bulawayo by 26 July and then journeyed to Pandamatenga accompanied by a large party. Mrs Westbeech and Mrs Francis were not the first European women to visit the Victoria Falls…that honour goes to Mrs Reader who accompanied her husband and child in 1862.

1876

Westbeech with his employees Bradshaw and Walsh travelled through Jacobsdal on the boundary between the Orange Free State and the Cape Colony and by October 1876 were back at Tati. Westbeech briefly visited Bulawayo in December before starting back to Pandamatenga with Grandy, Dorehill and Horner.

1877

Westbeech was between Pandamatenga and Barotseland during the year with his wife visiting him accompanied by Phillips in the winter months. In September, his wife left Pandamatenga for the last time and although Westbeech tried the following year to be reconciled with her, it was obvious the marriage was over. She strongly disapproved of the rowdy drinking binges at Pandamatenga and learnt of his many relationships with native women on the Zambezi. Indeed Selous writes that every kraal along the Zambesi river had at least one woman who called Westbeech ‘husband.’ Westbeech seems to have accepted that his marriage was over.

1878

He planned a trip to England with his wife but never made it and again traded in Barotseland after promising the Rev Coillard to get permission to establish a mission in Barotseland.

1879

Westbeech and Bradshaw went through Tati on their way south in June 1879

1880

Westbeech was at Lesuma in June 1880

1882

Westbeech visited King Lewanika in the Barotse Valley in January 1882 returning to Pandamatenga on 4 April. On 30 August he was at Sesheke when the missionary Arnot arrived and supported his request to establish a mission in Barotseland. Once permission was granted, Westbeech assisted Arnot to the capital Lealui by boat on 19 December

1883

Westbeech left Lealui in February 1883 and was at Lesuma in mid-July when the missionaries Mr and Mrs Williams arrived. Although ill with fever he took them to the Victoria Falls and helped them over the Zambezi. Still ill he was at Sesheke in October before travelling back to Pandamatenga.

1884

In May despite having fever he assisted the German travellers Schulz and Hammar by providing porters to the Victoria Falls and then up the Chobe river. In July he welcomed Rev Coillard to Pandamatenga and sent messengers to King Lewanika to ensure they had a welcome reception into Barotseland.

1885

Westbeech and Horn, the son of William Horn the trader who preceded Westbeech into Barotseland left Shoshong on 20 March along the Hunter’s Road for Bulawayo where Westbeech spent several days discussing business with Phillips, Fairbairn and Lobengula. They were at the Nata river by 21 May and reached Pandamatenga on 28 May.

Trade in Barotseland had almost ceased in Barotseland because of civil war between the factions of Lewanika and Akafuna Tatila. In June Westbeech arrived at his store at Lesuma and saw the Coillard missionaries. Harry Ware and Percy Reid arrived in on 27 July; Ware had broken his thigh and Westbeech cared for him at his house and arranged for Reid to visit the Victoria Falls and go hunting on the Machili river. Westbeech travelled twice from Pandamatenga to Sesheke in November and December to negotiate between the warring headmen.

1886

Blockley accompanied him on the second trip when he left Pandamatenga on 29 December, reached the Chobe river by 9 January 1886 and was at Lealui to meet Lewanika by 14 February. Rev Coillard arrived in late March to assist in the negotiations and Westbeech left on 29 March taking Yeta, one of Coillard’s missionaries to Sesheke where Westbeech was given a silver watch as a gift by Coillard before arriving back at Pandamatenga on 23 April.

Westbeech with his hunters and Frank Watson left Pandamatenga on 31 May; Watson went to Lesuma to bring back trade goods to Kazungula which was used to purchase a good quantity of ivory from Lewanika. Westbeech went on to his new hunting ground in the Linyati Valley and sent his hunters in all directions. In early August Lewanika withdrew his hunting permit, but this was ignored by Westbeech until a second order arrived on 25 August. In early September he took his ivory and hunters to Kazungula where Watson was building a store.

Westbeech arrived at Lealui in the Barotse Valley on 14 October and obtained an apology from Lewanika for his recent poor behaviour. He was back at Kazungula by 19 November where he ordered Watson and Fry to accompany Holub to Klerksdorp on 7 December and finished off the construction of the store at Kazungula himself.

1887

Westbeech stayed at his store at Kazungula ill with fever from January to June. He obtained permission for two sportsmen Cory and Starkey to hunt in Barotseland and made a difficult journey with them to Lealui on 6 September. He left Lealui on 6 December in heavy rains reaching Sesheke on the 27 and Kazungula on the 7 January 1888.

1888

Father Middleton of the Paris Mission nursed Westbeech through a bad attack of dropsy (oedema) and liver trouble until he left Kazungula on 16 January. Father Dardier arrived from Sesheke on the 1 February, but despite Westbeech giving him intensive nursing died on 23 February. Westbeech stayed at Kazungula until mid-May waiting to get back to Pandamatenga.

He left for the Transvaal and was at Shoshong in late June but died whilst trekking at Kalkfontein in the Transvaal Republic on 17 July 1888 and was buried at the nearby mission station of Vleeschfontein.

Westbeech spent twenty-six years in Southern Africa and helped many hunters, missionaries and travellers on their way to Barotseland and the Victoria Falls. He smoothed the way for the Reverends Arnot and Coillard to establish missions in Barotseland through his friendship with Lewanika. He was the friend and trusted adviser to the Barotse Chiefs Sipopa and Lewanika and to King Lobengula and was a member of the Barotse Council of State and treated as an honorary inDuna in Matabeleland. Westbeech and Blockley were the first Europeans after David Livingstone to travel in the upper Zambezi region of Barotseland.

Westbeech traded in Barotseland from 1872 until his death in 1888 and was the best-known European at the Zambezi for fifteen years. Everyone who met him only had good things to say about him. Major Henry Stabb called him: “a gentleman by birth and education.”

Barotseland

The Barotse lived in the fertile Barotse Valley along the Zambesi river above the Victoria Falls. They were conquered by the Makololo about 1826 but overcame their oppressors in 1864 – 5 and under their Kings became a powerful sovereign tribe over the many tribes near their valley and controlled the region between the Chobe and the Zambesi and the Tonga tribes at the Falls and below.

Leask, Westbeech, Phillips and Fairbairn

In his younger days Lobengula had joined George Westbeech and George Arthur ‘Elephant’ Phillips at their hunting camps and enjoyed their company. They traded for eight years in Matabeleland before they moved their base to Pandamatenga in 1871 and Lobengula was well-disposed towards these old residents of Matabeleland. Phillips travelled down country to discuss a mining concession with Lobengula and these talks continued over a long period with Westbeech complaining that Phillips was too occupied in drinking native beer and taking too long. [See Westbeech letter to Leask below]

The following is a copy of the agreement between Thomas Leask and his partners and was written by Leask and dated 3 June 1881:

We the undersigned George Westbeech, James Fairbairn and Thomas Leask having mutually agreed to make application to Lo Bengula – the Chief of the Matabele country – for certain cessions and rights to dig for gold and other minerals in that part of his territory named Mashona Country. We therefore hereby mutually agree and bind ourselves to each other that in event of any one of us individually or all of us collectively obtaining said cession and right to dig for gold in any part of Lo Benguela’s territory we each equally bear whatever expense may be connected therewith and we shall each equally share all profits that may in any way accrue therefrom. And we further agree and bind ourselves individually and collectively to allow Mr George Phillips, who is not here present, to join us in this venture and to share equally with us in expenses and profits thereof.

Signed at Klerksdorp Transvaal this third day of June in the year of our Lord 1881 in presence of undersigned witnesses.

Witness

Jno W. Walker George Westbeech

Peter Carmichael James Fairbairn

Thomas Leask

Westbeech letter to Leask[xxxi]

Sesheke, 1 Sept 1882

My Dear Sandy,

Expecting daily to start for the Barotse Valley in quest of ivory as the King [Lewanika] has now returned from the Bashukulumbu war victorious driving home about 20,000 head of cattle, I send you a few lines in expectation of there being a chance of its going per Jesuits wagon before my return. I have during the winter got together a wagon-load of whips, sjamboks and riems and a little ivory, of which latter article there is no scarcity if only I had powder and I am living in constant dread that someone else will come in with that article knowing how scarce it is and get what I can have myself. If John brings me some you can expect me soon: if not, do not expect me soon, as I have made up my mind not to come out without something worth coming out with. George Wood is dead: went to Daika for change of air and died there. I had a letter from Phil [Phillips] some months ago telling me that he was doing nothing with Loben and if he did not soon get Mashona country [i.e. permission to hunt] he would come on foot here. However up to the present he has made no demonstration.

I am getting as thin as a lath and am never really well; the constant travelling I have had and worry enough to have killed anyone else is telling on me and completely aging me.

You had better write to Phil and insist on his coming here if only to assist me; he might listen to you but never will to me. I think I should have had an answer, either yes or no from Loben in less than 12 months, but between ourselves I do not believe that either himself or Fairbairn have moved at all in the matter since I opened the matter for them last August. I believe they are too funky of the King. Do not fail to keep any letters that pass through your office for me until my return from the interior as I do not want to run the chance of missing them on the road. Now Goodbye, old friend. I will write again if an opportunity presents on my return from the Barotse and let you know how I’ve succeeded. In the meantime please accept my kindest wishes and with kind regards to Mrs Leask.

Yours sincerely, George Westbeech

By the bye, a gentleman arrived here 3 days ago, a Mr Arnot on missionary work. I think I have been of use to him: however you will hear from himself some day: in the meantime he desires to be kindly remembered to yourself and Mrs Leask.

Concession with Lobengula

On 25 January 1884 Lobengula made his mark on an agreement with Thomas Leask, George A. Phillips, George Westbeech and James Fairbairn which stated:

I Lobengula, King of the Amandebele nation have this day granted to Messrs Thomas Leask, George A. Phillips, George Westbeech and James Fairbairn permission to dig and mine for gold and other minerals in my country between the Gwaie [Gwaai] and Hunyani [Manyame] rivers and to remove the product. Also I have given them permission to have a few white men to work and prospect for them.

By this grant I cancel all former grants and concessions and this is the only one valid. I give the said company power to add to their number and I also promise to protect them.

Lo Bengula

X

His mark

As witness Elephant seal embossed

T. Halyet

John H. Whitaker

For further background on the concessions that Lobengula granted see the articles Were Lobengula and the amaNdebele tricked by the Rudd concession and Land and the British South Africa Company - the Renny-Tailyour and Lippert concessions under Bulawayo in the website www.zimfieldguide.com

After George Westbeech’s death Thomas Leask and George Phillips sold out to Rhodes for £30,000 each. James Fairbairn refused to sell until a year later when Rhodes would only pay £3,000. Leask and Phillips each paid one quarter of their proceeds into Westbeech’s estate, but Fairbairn did not.

Sources

Once again I am indebted to Colin Weyer who has permitted me to use his scanned copies of the 1:250,000 Series of present-day Zimbabwe published by the Surveyor-General in 1975. These I have consistently used on a scale of 3cm to 10kms or 2 inches to 10 miles.

For plotting the Westbeech Road on the maps and descriptions I have used Eric C. Tabler’s books The Far Interior and Zambezia and Matabeleland in the Seventies – both excellent sources if you can get them.

For information on George Westbeech I have used mostly Tabler’s books on The Far Interior and Pioneers of Rhodesia and Trade and Travel in Early Barotseland and Richard Sampson’s first-rate biography White Induna; George Westbeech and the Barotse People

References

T.V. Bulpin. To the Banks of the Zambezi. Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1965

R. Sampson. White Induna; George Westbeech and the Barotse People. Xlibris Corporation, 2019

F.C. Selous. Travel and Adventure in South-East Africa. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1973

P. Shaw and N. Parsons. A Note on George Copp Westbeech (1844-1848) Botswana Notes and Records Volume 21, 1989

E.C. Tabler (Ed). Zambezia and Matabeleland in the Seventies. The Robins Series. Chatto and Windus, London 1960

E.C. Tabler. The Far Interior. A.A. Balkema, Cape Town 1955

E.C. Tabler. Trade and Travel in Early Barotseland: Diaries of George Westbeech, 1885-88, and Captain Norman MacLeod, 1875-76. The Robins Series, University of California, 1963

E.C. Tabler. Pioneers of Rhodesia. C. Struik (Pty) Ltd, Cape Town 1966

J.P.R. Wallis. The Southern African Diaries of Thomas Leask 1865-1870. Chatto and Windus, London 1954

[i] White Induna; George Westbeech and the Barotse People

[ii] Pioneers of Rhodesia, P168

[iii] White Induna, Preface

[iv] Zambesia and Matabeleland in the Seventies, P23 - 66

[v] Travel and Adventure in South-East Africa, P153

[vi] Ibid, P197

[vii] Holub, Emil. Seven Years in South Africa: Travels, Researches and Hunting Adventures, Between the Diamond-Fields and the Zambesi (1872–79)

[viii] The Far Interior, P41

[ix] The White Induna, P35

[x] Karl Meyer was German sailor who jumped ship at Port Elizabeth, spoke good English and sometimes worked repairing wagons but spent most of the late 1860’s and 1870’s in Matabeleland.

[xi] Barricade of thorn bushes

[xii] This does not make sense

[xiii] Barber states in Zambesia and Matabeleland in the Seventies, P55 that he uses a twelve bore percussion musket

[xiv] Alfred Cross first came to Matabeleland with his uncle, William Tainton and W.A. ‘Zambezi’ Browne and stayed as their partner hunting and trading until about 1880.

[xv] Zambesia and Matabeleland in the Seventies, P47

[xvi] The Far Interior, P42

[xvii] To the Banks of the Zambezi, P178

[xviii] White Induna, Preface

[xix] Zambesia and Matabeleland in the Seventies, P48

[xx] Travel and Adventure in South-East Africa, P103

[xxi] About 80 kms as the crow flies

[xxii] Barber forgets that Browne was also with them; they left Pandamatenga on 14 August 1875

[xxiii] Curator of the South African Museum, Cape Town from 1876 to 1895

[xxiv] The White Induna, Notes and References No 5, P149

[xxv] Ibid, P6

[xxvi] Ibid, P12

[xxvii] Ibid, P15

[xxviii] Ibid, P11

[xxix] The Far Interior, P399

[xxx] Gordon at this time was working for Chief Macheng and collecting £1 per head from gold miners intending to work at the Tati goldfields

[xxxi] The Southern African Diaries of Thomas Leask 1865-1870, P234