Home >

Matabeleland North >

An 1886 journey through the Bechuanaland Protectorate along the Western Old Lake Route to the Victoria Falls that nearly ended in disaster

An 1886 journey through the Bechuanaland Protectorate along the Western Old Lake Route to the Victoria Falls that nearly ended in disaster

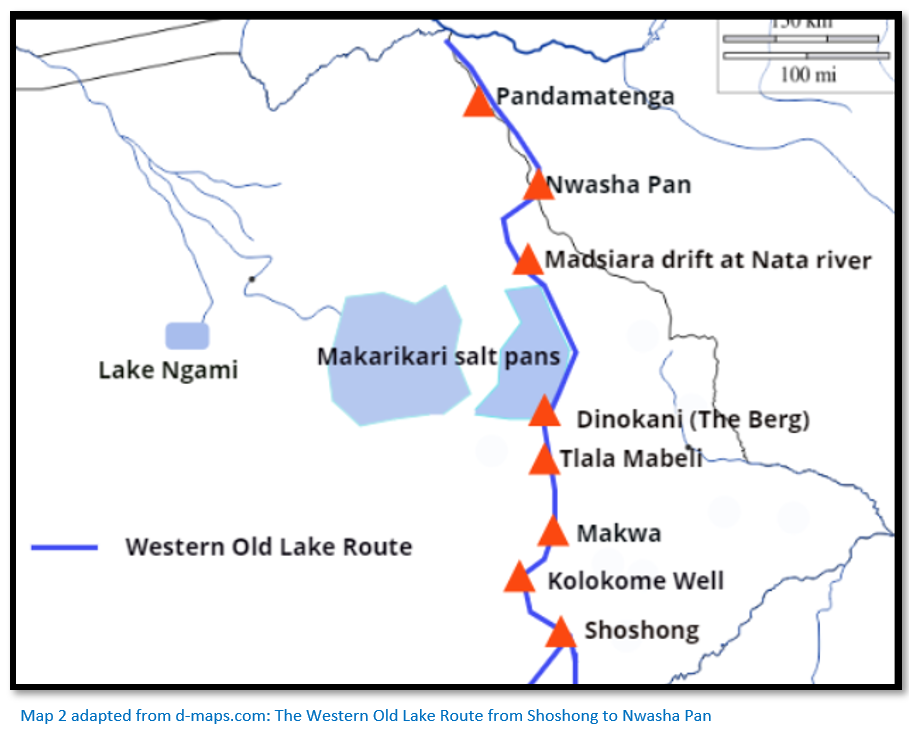

The book by Alfred James Bethell is compiled from a series of articles that he wrote up for The Field Magazine. There are just three chapters and any traveller that relied on this book as a guide might have come to serious grief much as the author did himself travelling the Western Old Lake Route from Shoshong to Nwasha pan; his fellow-traveller Trooper Arnot died soon after returning from the ordeals of the journey; his book makes no mention of this. The logistical details are sketchy and superficial when compared with seasoned African travellers as in Shifts and Expedients of Camp Life, Travel, and Exploration by William Lord and Thomas Baines.

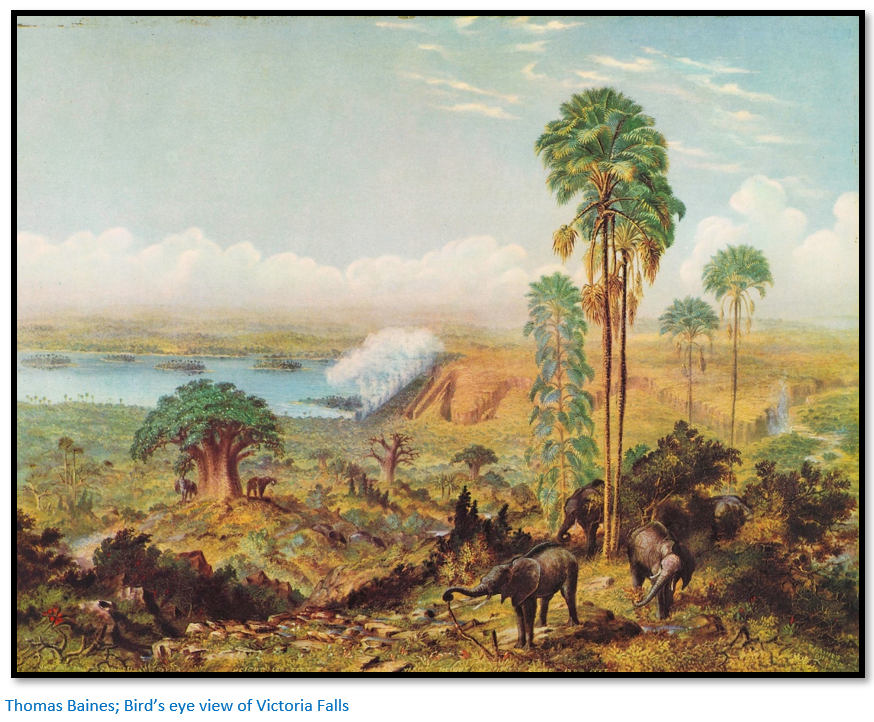

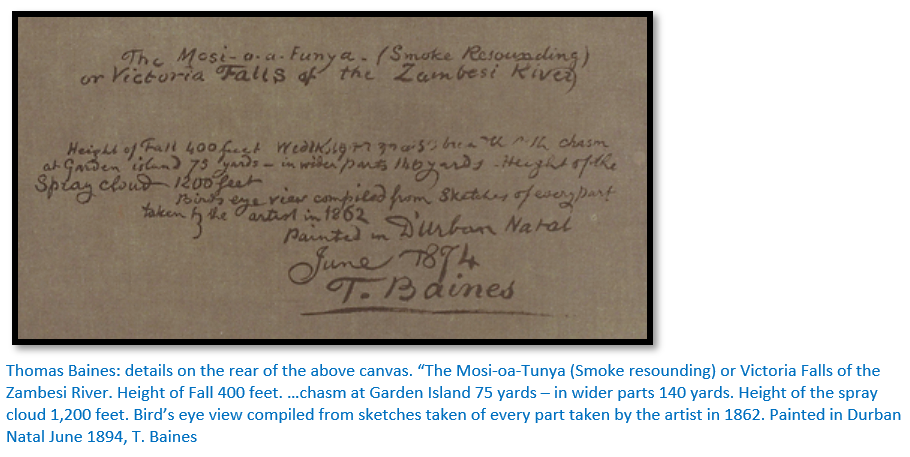

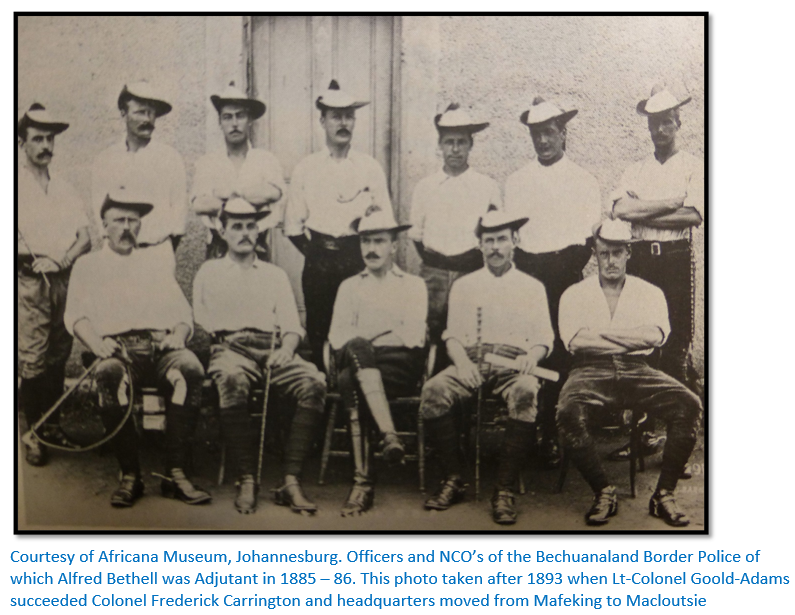

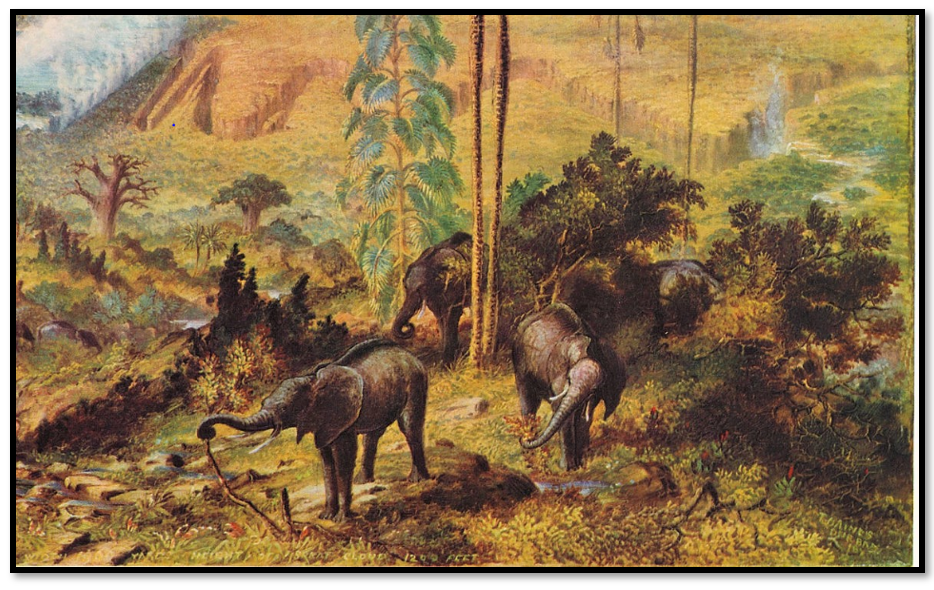

The major problem with the book is that the author had little experience in hunting or in travel in the Far Interior. His Southern African experience comprised eighteen months within the Bechuanaland Border Police (BBP) and most of his anecdotal hunting experiences told in the book were apparently heard within the Officers’ Mess where he was Adjutant. Even the book cover of the Books of Rhodesia reprint featuring the elephants of Thomas Baines birds-eye view of the Falls painted in 1864 would lead the reader to believe this is a serious book on hunting, which it is not!

Those with little experience of life within the interior relied on using experienced hunters and traders, drivers and guides who had acquired a knowledge of the kind of problems that travelling was likely to throw up; without that kind of knowledge any traveller would be seriously handicapped as they would soon find out.

Eighteen months experience within the regimented order of the BBP would not have provided sufficient experience and so it proved. They were ill-prepared and badly provisioned for their trip to the Victoria Falls (despite the advice he gives in his book) and were saved in the inward journey by George Blockley at Pandamatenga and then used George Westbeech’s infrastructure of contacts and guides to continue on their way. When their horses gave up on the return journey they had to send for help and were rescued by a BBP cart and trooper over the last 240 kms (150 miles) to Shoshong. Bethell resigned from the BBP almost immediately from ill-health.

Chapter 1 – Introduction

This aims to give intending hunters to South Africa an inkling of what to expect and how to prepare themselves. Bethell explains to elephant hunters that in 1886 the only areas with any potential for success lie in Northern Bechuanaland, Matabeleland and Mashonaland. In the Northern Transvaal and Zululand the elephant were extremely scarce. The Kalahari, Namaqualand, Damaraland and Ovamboland contained large quantities of game but the scarcity of water and remoteness made hunting difficult and for the experienced only.

What he does not say is that by 1886 the elephants had retreated into the most inaccessible areas of low-veldt tsetse-fly country where hunting on horseback was impossible and hunting on foot was a much more difficult and dangerous task.

Clothing

He recommends a hunting coat of buff moleskin to resist the wag 'n bietjie “wait a minute” thorns, Bedford cord breeches, brown leather “field” boots and some good thick flannel shirts topped off with a Boer hat, viz. a thick soft felt hat with a high crown and broad brim.[i] However most well-known hunters such as Selous and John Lee reveal they wore minimal clothing when elephant hunting.

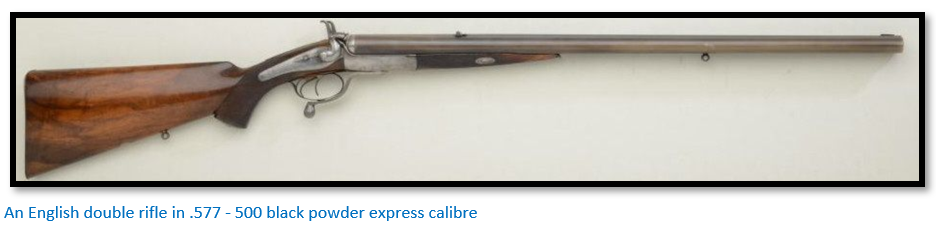

Guns

His recommendations are

- A strong central-fire 12 bore shot gun

- A double .500 black powder express

- A big elephant gun, presumably he means a large calibre black powder smooth-bore Roer.

The initial journey to get started

Bethell recommends landing at Cape Town and taking the train to Kimberley.

Equipment

Bethell suggests that having reached Kimberley the next thing is to get a wagon or two, drivers and voorloopers. He writes that if the sportsman has no African experience or has not arranged to go with a hunter familiar with the territory, he confides himself, his cheque book and his faith to a “substantial businessman” in Kimberley! Wagons and oxen at the time were comparatively cheap, a good Grahamstown wagon and twelve oxen to be bought for under £150.

Daily rates for drivers are 2/- to 2/6; voorloopers are 1/- to 1/6; food has to be supplied as well. He adds that the difference between a good driver and a bad one is equal between a pleasant trip and a disastrous one.

He says that as South African hunting is almost always done on horseback that “salted horses” should be obtained, i.e. horses that have had horse-sickness and recovered and therefore have a certain immunity. Salted horses were expensive costing £100 - £150 but of course there are no guarantees the horse is immunised. He recommends pinching a horse’s skin to test if it is salted and states that a salted horse “generally has a sleepy kind of look and is often lazy.” [This seems a dubious test to say the least]

Current practice at the time as the best preventative to African horse-sickness (AHS) was to keep horses tied up with nosebags on until the sun was well up and then to bring them in before sundown and never let them feed on low ground. [African horse sickness is usually fatal to horses and is spread by biting midges (Culicoides) and his suggested remedies are unlikely to be effective at all]

He lists the characteristics of a good shooting horse – soundness, fairly fast, a good stayer and steady under fire. But how do you test for these qualities at Kimberley far from the hunting grounds?

On supplies his advice is a little skimpy: tinned meats, coffee, sugar, meal, potatoes, jams, tinned milk, pepper, salt and tobacco. A small quantity of medicines should be taken including calomel, jalap and quinine for fever; morphia and ipecacuanha for choleraic attacks; eau-de-luce and ammonia for snake bites and some brandy.

Trekking from Kimberley

Leaving Kimberley the first four or five hundred miles is the same through Taungs, Vryburg, Mafeking to the Crocodile river and Shoshong. Then the choices are:

- From Shoshong to Lake Ngami is about a month’s trekking by ox wagon

- From Shoshong to the Mababe river (north east of Lake Ngami) about the same time

- From Shoshong to Mashonaland on the Hunter’s Road to Tati and then on to Gubulawayo, about a month’s trekking and then about a further three weeks to Mashonaland. He mentions that Lobengula’s consent is required to enter Matabeleland and that he expects a present in return. This trip is recommended as the best as the countryside is scenic and water usually abundant

- He notes that game is extraordinarily abundant north of the Zambesi river, but gives no advice on getting there as Bethell had travelled on none of the above routes.

Estimated Cost of an 8 month hunting trip to the interior

£ | |

Voyage from London to Kimberley and back | 100 |

1 x ox-wagon with span of 12 oxen and 4 extra | 150 |

1 x 12 bore shotgun | 20 |

1 x .500 Black powder express | 40 |

1 x Roer elephant gun | 40 |

Cartridges | 20 |

2 x salted horses | 100 |

Stores, including native barter items | 100 |

Cash for incidentals on the journey | 50 |

Driver wages (240 days @ 2/6 per day) | 30 |

Voorlooper wages (240 days @ 1/6 per day) | 18 |

668 | |

less sale of wagon and oxen @ half-cost | 75 |

593 |

The estimate looks as though it has been carelessly prepared; the salted horses cost less than the prices stated in the text, estimates for stores and the wages for the native servants look low.

Chapter 2 - The Early Days of Kimberley

This chapter was clearly included just to fill out the book and is composed of anecdotes which the author must have picked up in conversation and are so general as to be practically useless and not worth repeating. Half the chapter is not even about Kimberley at all, but the tribes beyond Kimberley with a crude and very superficial commentary on their chiefs. The author says his expectations of Mankoroane, the chief of the Batlapin tribe at Taungs were high, but they read like a child’s recollections from Le Morte d’Arthur and the reality was of course, quite different. The chief is presented in a very unflattering light and principally interested in cadging gifts including tobacco, brandy and clothing. Montsioa, chief of the Baralong is presented in a condescending way. Sechele, chief of the Bakwena, is parodied for his dress. Only Khama, chief of the Bamangwato is described in a positive light.

Chapter 3 – A ride to the Victoria Falls of the Zambesi

Shoshong is described “as much like other native towns; that is, a mass of huts shaped like bee-hives, inhabited by a mass of bipeds shaped like monkeys.” This unpleasant description probably describes Bethell’s general attitude to local people and why his travels were beset with so many mishaps. He comments that from all native towns: “a peculiarly unpleasant odour arises, which is caused by the natives excessively crude recognition of the established laws of sanitation.” Has he forgotten that London’s “Great Stink” of July and August 1858 caused by the same problem had occurred less than thirty years before?

In March 1886 as Adjutant of the Bechuanaland Border Police Bethell spent a few months in Shoshong during his eighteen months in Bechuanaland and says the dry and monotonous scenery drove him to seek out the Victoria Falls because it was wet and green. He says only about fifty Europeans had seen the Victoria Falls since it’s discovery by David Livingstone in 1855 until 1886 [In a recent article The First European Visitors to view the Victoria Falls before the end of 1880 under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com; my article lists at least 100 Visitors between 1855 – 1880]

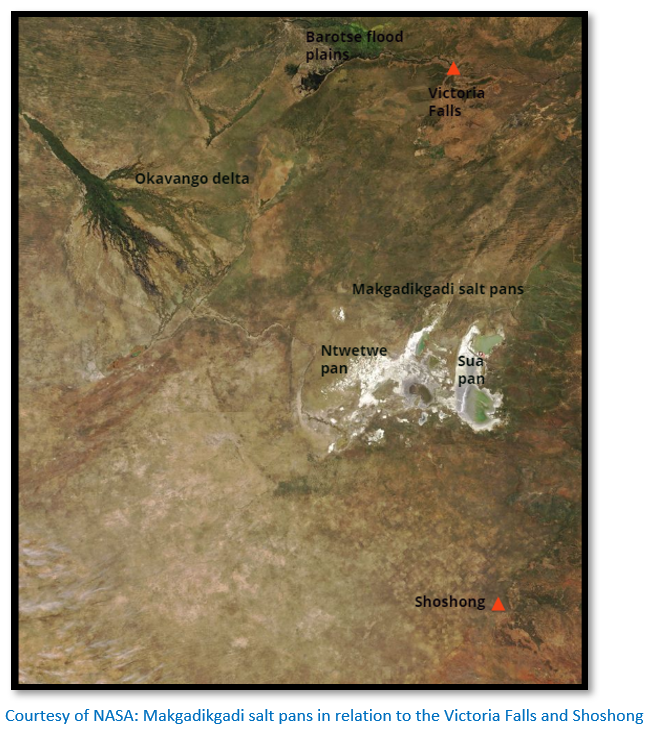

On 31 May Colonel Carrington[ii] and Colonel Aitcheson , a Mr Dunne and Bethell and Trooper Ayrton, set off in wagons from Shoshong. They took a native guide whose failings he says were he “had an unpronounceable name and had forgotten the road” but they christened him “Bodger.” The countryside is described as uninteresting and he says they did not do much shooting until they reached the Sua saltpans; although I think he means they did no shooting!

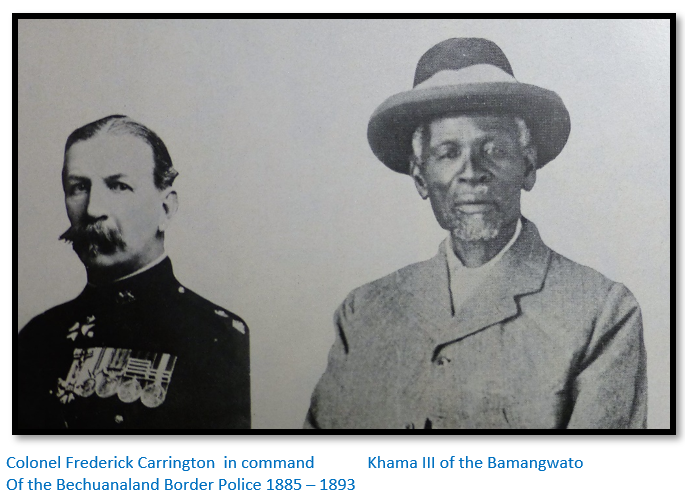

Bethell’s book was actually dedicated to Colonel Frederick Carrington in January 1887 perhaps while the author was at home convalescing in England.

The Sua, formerly Shua salt pans are on the eastern side of the Makgadikgadi; the Ntwetwe salt pans are on the west. Bethell states the Sua salt pans are fed by two small rivers[iii] and says their hunting is fairly successful without giving any specific details. Here he shot his first ostrich which he first wounded through the wing and “pursued my wounded bird for about two miles, over open flat ground, literally undermined with ant bear holes” until “with a lucky shot I cut his head off with a bullet.”

Then diverting to another occasion and another time he marvels at the ability of game to keep running despite being hit with a heavy bullet such as a .577 express. They came across a young giraffe bull and shot at him for an hour “’til at last he fell from exhaustion.” Bethell says they cut eleven bullets out of the carcase, “but there were probably fourteen in” and “he looked more like a plum pudding than nature had created him.”

One day their Carrington party sent their servants to cut up a Quagga, [mistaken, it must be a zebra, as Quagga were by then extinct][iv] but the servants soon ran back saying there was lion spoor around the carcase. One would think as sportsmen they would investigate signs of a lion, but no: “I think we were lazy that morning; anyway we sent them off again to see if the lion was on the quagga, and if he was, to come back and tell us.” Unsurprisingly the lion had taken advantage of the delay and made off with half the carcase!

Bethell does not appear to have personal hunted lion, although he tells some tales about how lions terrify oxen around the wagons at night by their smell and another story of a close encounter that Henry Collison, a hunter and trader, had with a lioness which he wounded before retreating to a tree and only just managed to climb into before the lioness took his shoe.

Bethell and Trooper Ayrton set off alone for the Victoria Falls on 17 June 1886

Bethell and Ayton left the Colonels and their party of native servants at their wagons to ride away on horseback to the Victoria Falls. They had a horse each and took a pack horse with supplies of coffee, tobacco and biltong with some meal and biscuit.

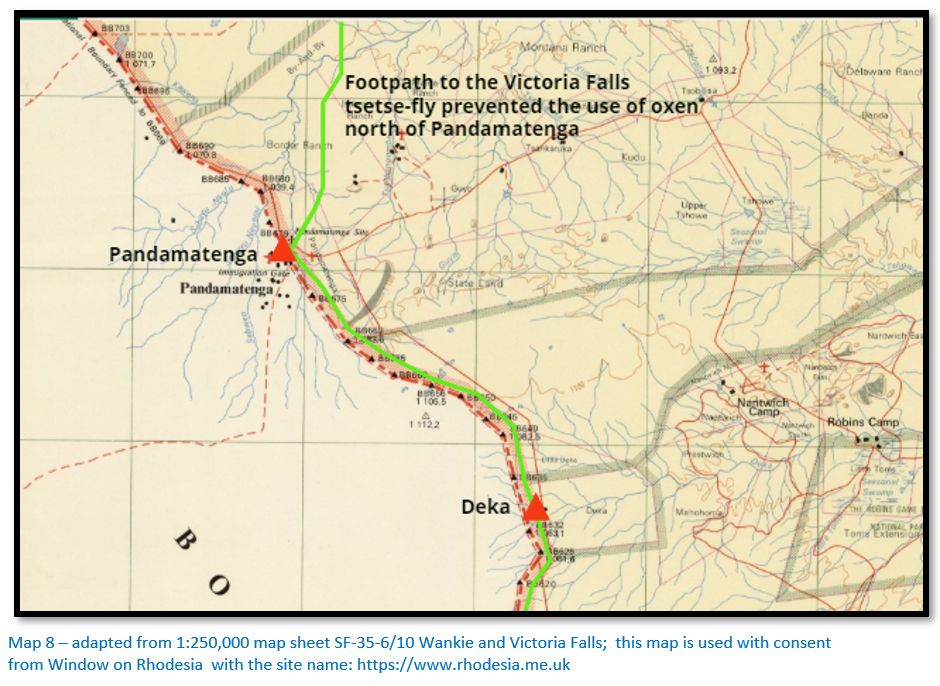

By midday next day when they reached water after riding through the night they estimated they had gone 72 kms (45 miles) They rested in the afternoon and kept alert at night for lions which were numerous. Thomas Fry, a Shoshong trader had given Bethell the names and distances of the waterholes on the road[v] but Bethell does not appear to have made even a sketch-map of the route.

They decided that the horses would need to forage for themselves and hung up all their meal in a tree to be collected and used on their return journey. Both their watches had stopped working. They knew they were going to pass a series of vleis and then there was a long distance without water, but without a map did not know which was the last vlei with water and choose the wrong one.

When they did reach water after several days riding they found it was liquid mud and not fit to drink. Whilst resting they were circled by a dark form but could not determine what it was in the dark. When the moon came up they rode on and finally heard frogs croaking, but the horses would not drink the little water they saw and they rode on expecting to reach water the next day at midday.

No water was seen and the pack-horse stopped and would travel no further. So thinking water was close by, they left the pack-horse with a plan to return in the morning. At moonrise they set off again taking a handful of biscuits and a tin of cocoa. Six miles passed, twelve, fifteen and still no water.

Now thoroughly alarmed they rode on through the night, but came upon no water and by daylight their horses were done in. About 9am they would go on no further and their water bottles were almost empty. They lay their coats over the saddles and walked on driving their horses in front of them. By 11:30 they were so exhausted they had to stop and rest before going on again. “No one who does not know what real thirst is, can conceive any idea of the horrors of it. First one’s throat seems to close up, then one’s tongue gets too big for one’s mouth, then one’s lips turn black and then one gets dizzy in the head.

…At last about 1pm I saw a game path leading to a vlei some hundred yards away; but we had passed so many vleis and they had all been dry that we hesitated before going to see. However, I determined to go down and I found water…I fancy I gave a yell to Ayton and then plunged my head into the beautiful clear pool and drank a little…We had been two nights and a day and a half riding hard without water and had covered about eighty miles or more of very heavy sand. It turned out that the water which looked a little at night was the last permanent water and that we had consequently missed it.” [It appears they missed Tamasetsi vlei between Gerufa pan and Deka pan in the darkness]

Bethell writes: “Just before we reached the water I was weak enough to drive on my horse by touching him with the butt of my rifle. I suppose I must have hit a bone, for suddenly the stock broke off at the small and we were left with nothing but a shotgun.” It would take more than “touching him” to break the stock of a .577 express!

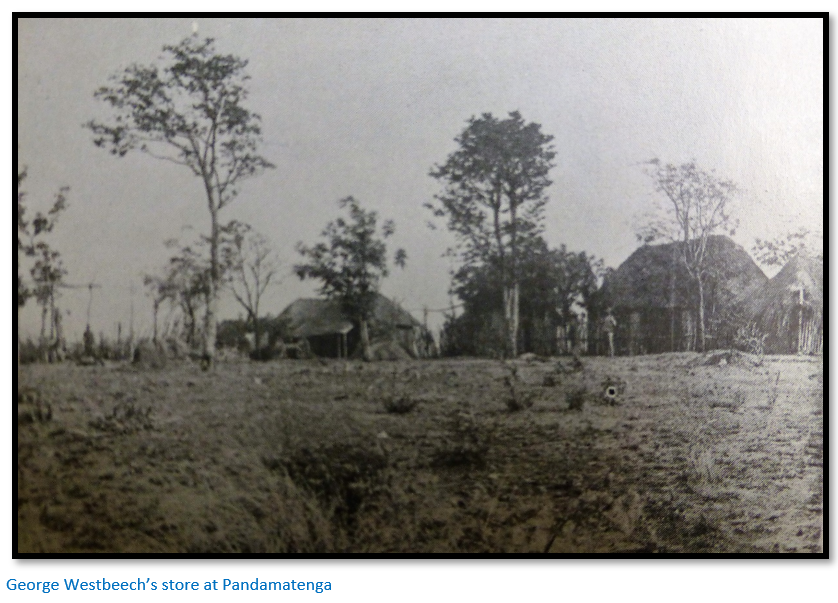

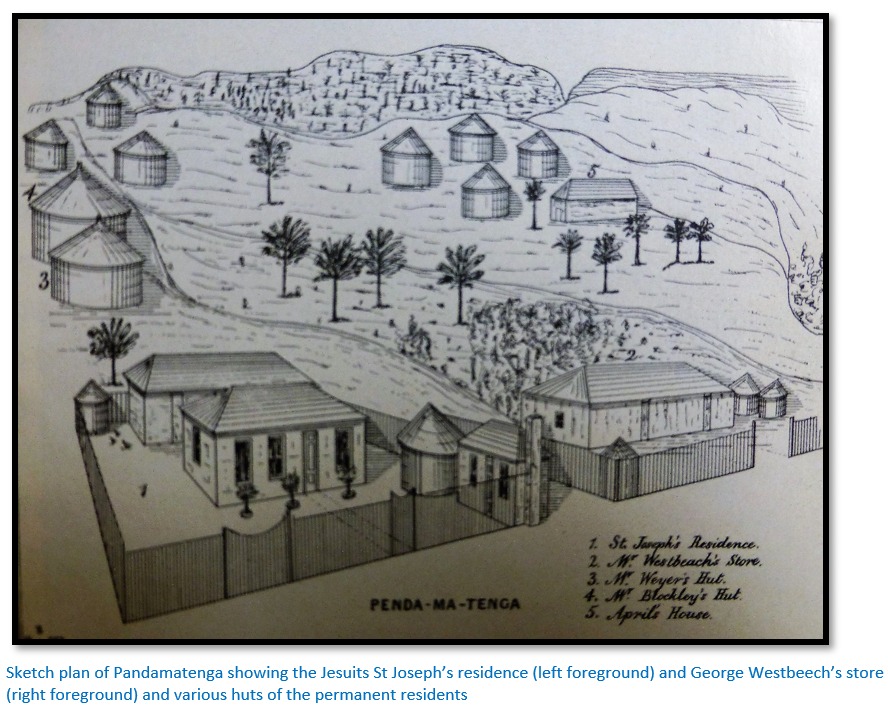

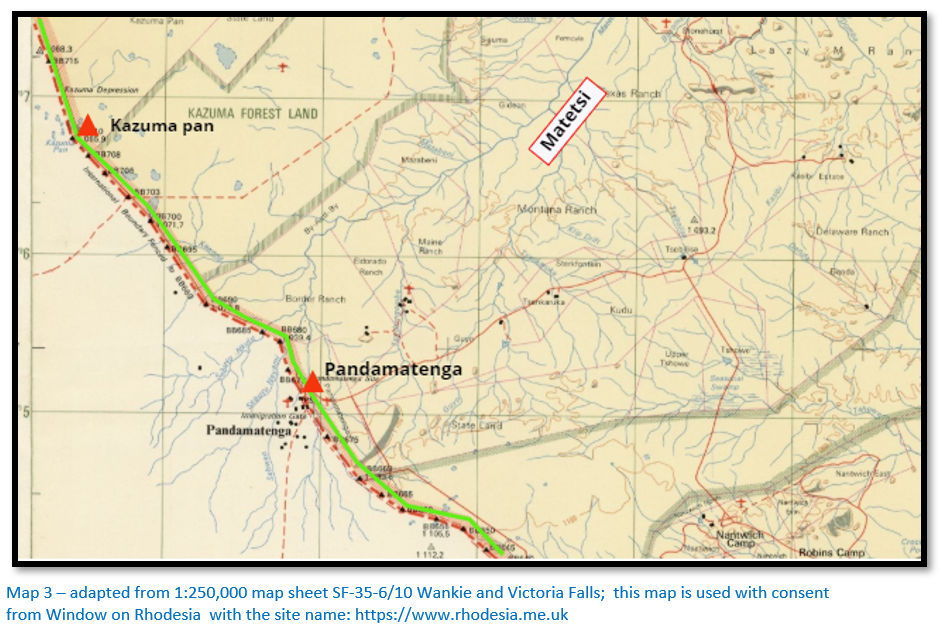

Arrival at Pandamatenga on 25 June 1886

They slept the night at Deka pan under a tree and arrived next day at Pandamatenga with just one teaspoonful of cocoa left! Their plan was to replenish supplies at George Westbeech’s store[vi] and go on to the Victoria Falls approximately 85 kms (53 miles) away by foot.[vii]

However George Westbeech was on the Zambesi but his assistant George Blockley[viii] remained behind at Pandamatenga. Bethell says: “This gentleman treated us with the utmost kindness and did everything in his power for us; but even he could not bring the store to us, so next day we left the horses with him and started to walk to the store.”

As soon as Bethell showed Blockley his gun with the broken stock, Blockley set to work and repaired it using the hide from the inside of an elephants’ ear so that it was serviceable again.

Bethell questioned Blockley on malaria fever which Blockley said he suffered from most years and took croton oil[ix] and enough quinine[x] and only stopped when he had singing in his ears! The ever-helpful Blockley gave them two carriers to take their supplies and guide them to the store at the Zambesi and then to guide them to the Victoria Falls and then back to Pandamatenga, a round trip of about 320 kms (200 miles)

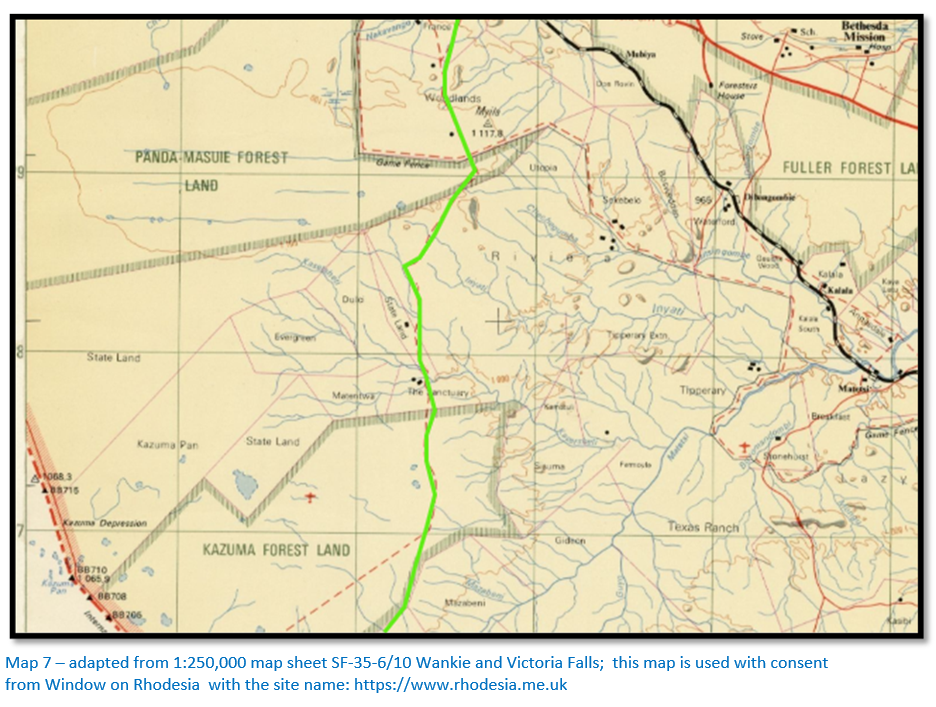

Walk to the Zambesi

The first days’ walk took them to Kazuma pan through undulating well-watered and wooded country. Once again Bethell shows a lack of cultural understanding: “Next day we started at dawn, or rather we wanted to start at dawn, but the ‘boys’ like all other natives, utterly declined to move before the sun was well up. White men naturally prefer walking in the cool, but natives or ‘boys’ as they are indiscriminately called, always feel the cold. This may possibly be due to their wearing no clothes, but my conviction is that they do it out of pure cussedness.”

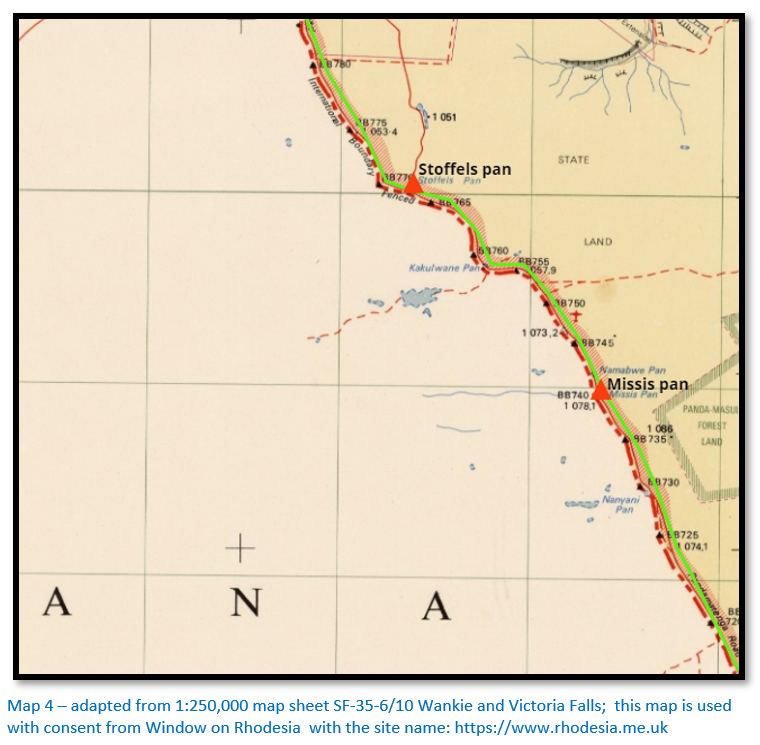

Then he states: “As I said, we started soon after dawn” which makes one question why the previous comments were necessary! They walked for 3 hours through thick sand, then a short break for coffee and some meat and: “through that interminable sand we ploughed for about 25 miles, with the sun broiling us and the flies devouring us half cooked, til at last we reached water in the evening.” At that moment one of their guides christened ‘Scorpion’ heard a honey-bird and soon brought back a supply. Bethell says he and Ayton ate about 10 lbs of honey in five days and liked it.

Arrival at the Zambesi river

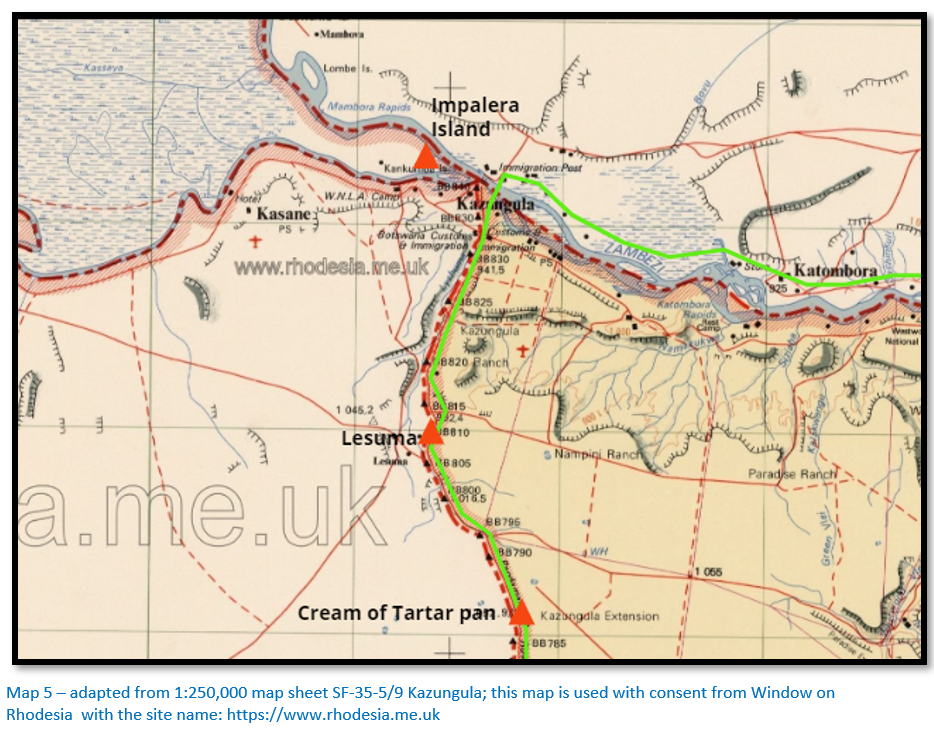

Next day after walking through another 15 miles of sand they reached Lesuma pan. A short walk next morning through beautiful countryside brought them within sight of the Zambesi and by the edge of the river they found Westbeech’s wagons. They were greeted by a crowd of dogs and at a hut found Watson and Middleton,[xi] trader and missionary just about to breakfast on beans. Bethell says they had shot some pheasants [does he mean the francolin or the more common guineafowl?]

So they feasted on these before crossing the river “in quite the shakiest iron punt I ever was in” the punt belonging to Dr Emil Holub who had travelled into the interior a few weeks before.[xii]

The place George Westbeech had chosen for his new store was at the confluence of the Zambesi and Chobe rivers at Impalera Island which Bethell calls “one of the loveliest and most unique scenes it is possible to imagine.” Game he thought was very abundant…the problem was getting Chief Lewanika to give permission to hunt.

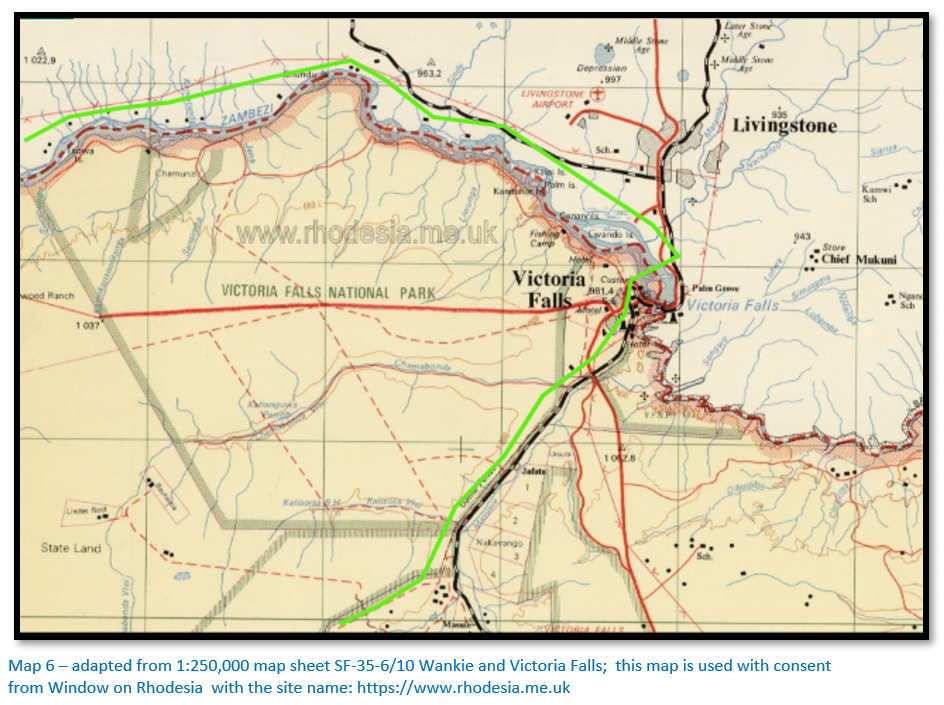

The most immediate problem for Bethell and Ayton was travelling the 85 kms (53 miles) to the Victoria Falls as the carriers said the south side of the Zambesi “was too full of lions” and getting permission to travel on the north side from the local kraalheads was tiresome and difficult. After much discussion the northern route was chosen.

Walking down the north bank of the Zambesi river to the Victoria Falls

Next day they crossed the river to the northern bank and walked along a path for about four hours before coming to their first kraal. They gave the headman some coffee to drink and obtained permission to continue their walk along the path which necessitated wading through a number of crocodile-infested lagoons.

Where the river bends to the south they planned to cut across the bend and arrive at the Falls the day after. They set off following the path that was some distance from the river: “Of a size about large enough for an ordinary jack-snipe[xiii] to hop along on one leg and shaped like an inverted V and one could not walk off it as the bush and grass was too thick.”

By evening they had reached the kraal of the Chief[xiv] whose permission was required to travel further. They had brought a supply of “stertreims” being about a yard and a half of calico worn around the waist. They met with the Chief who left them some grain, ground nuts and milk and cooked dinner using ox-wagon anti-friction grease tins as pots. Next day the Chief came down again and after a couple of hours walk brought them to the river where the smoke and roar of the Falls now seemed quite close.

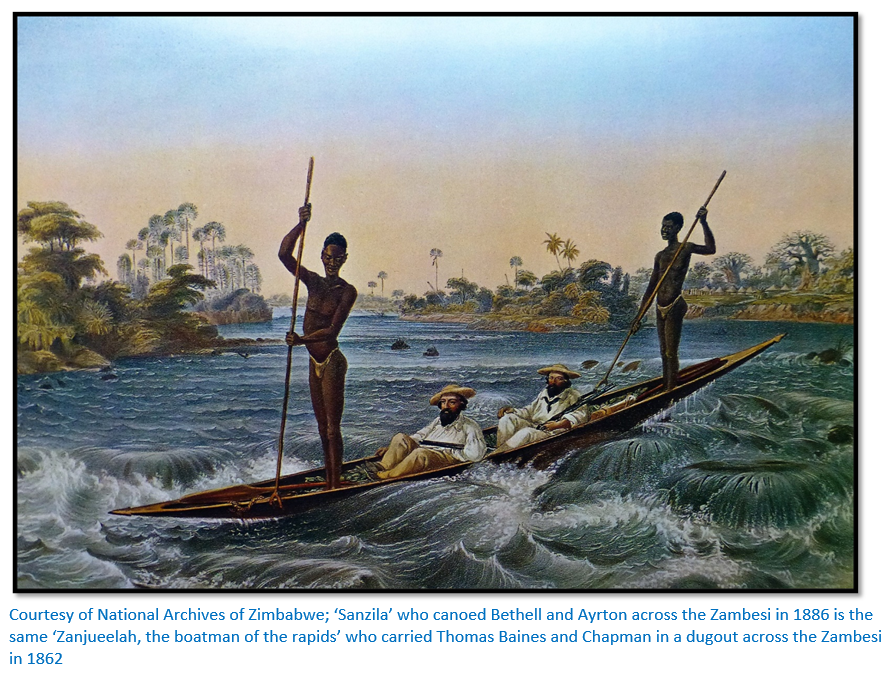

“Sanzila put us into a canoe made out of a log and about 4 inches out of the water and then got in himself which brought it down about 2 inches more. We sat in a pool at the bottom and devoutly prayed for a miracle while he paddled at the bows assisted by a diminutive native at the stern. Presently we got used to it and now I think I never enjoyed a trip more. On leaving the bank it looked quite a short way across to land on the other side, but on getting there one found it an island and after that one got more islands so that it took fully half an hour to get across…

A short walk through the bush took us down to the Falls and having chosen a place to camp we started off to see them. We could find no path, but by following the hippopotamus tracks through the bush we suddenly emerged right on the brink of the Falls.”

Bethell writes [P60] “Livingstone and I believe two other men landed on the island on the brink of the Falls and this same Sanzila, I fancy, took them to it.”

The Victoria Falls

“Perhaps no man has ever adequately described the magnificence of the Falls and it would be folly in me to attempt to do so; all I will do is say and give some sort of idea of their appearance…

The Zambesi above the Falls is about a mile or a mile and a half in width[xv] and is dotted over with large islands. Descending the river one would have not the slightest suspicion of any Falls being near were it not for the lofty columns of vapour rising over the trees so calmly and quietly does the river flow along. All at once without the least warning the whole waters of the river tumble with a noise like thunder over a chasm in its bed, some three to four hundred feet deep.[xvi] A part of the river, separated by an island from the main stream then turns abruptly away to the left at the bottom of the abyss and joining the other waters the whole rush out through numerous small channels [?] until they unite once more in the mighty Zambesi rolling its waves down to the sea…

It is perhaps unnecessary to add that the iris of the Falls is peculiarly brilliant in the blazing sunshine. The whole scene is one which utterly defies description; the uniqueness – to coin a word – of the Falls combined with their stupendous magnificence render it impossible for any words to do them justice; to understand and realise one must see.”

Return to Pandamatenga

“Ayton and I each burnt our most precious sacrifice to the deities of the Falls – he his last pipe of decent tobacco and I my last cigarette – and time being pressing, we left next morning for Pandamatenga where we arrived safely after three days walking over most horribly stony paths.”

Return journey to Shoshong

On 7 July 1886 Bethell and Ayrton left Pandamatenga accompanied by one of Blockley’s servants. “…our return journey promised to be harder than the journey up for between the Nata river and the Shoshong there is a stretch of sand, without water, nearly one hundred miles in length. Fortunately just before we started, four natives came up and said they wanted to go to Shoshong, so I engaged them at once and gave them as many empty calabashes as they would carry with the idea of sending them on with water for the horses when we came to the above-mentioned thirst…

We slept that night at the first water and next day went on about thirty miles and got to a water off the road which a bushmen [San Khoisan hunter-gatherer] we had with us, knew of. We were now crossing the long piece where we had found no water on the up journey. I ought to mention that Mr Blockley had sent a boy of his and two bushmen with us to go as far as the place where we had left the pack on the up journey, so they could take the packsaddle back to Pandamatenga and follow on the spoor of the pack-horse should we not find him.”

Bethell and Blockley’s men walked on ahead of Ayrton and the horses but when they reached the spot where they had cached the biscuits, coffee and cocoa and two kit bags with blankets on their way up they found them gone. All that was remaining were a few ground nuts and the remains of a fresh fire! He decided to send Blockley’s men after the pack-horse and wait for Ayrton and the horses and see if they could recapture their blankets.

After a long wait Ayrton appeared and said his horse was going lame. They now held a council of war about what to do next. They were 100 kms (60 miles) from Pandamatenga and about 483 kms (300 miles) from Shoshong with about 4 lbs of coffee, some fresh meat and biltong, a little local tobacco and a blanket each.

The decision was for Bethell to go ahead and try and catch the thieves who had stolen their packs with Ayrton to follow on with his lame horse and hopefully the recovered pack-horse. Bethell rode on about 20 kms (12 miles) before his horse tired and he decided to rest until moonrise before travelling on.

At the next water his horse refused to go further on, so he off-saddled for the night and slept. At dawn as he remounted he saw a campfire in the distance so he took his rifle and went over to investigate. The pack was untouched, so he hired the men to carry the pack to Shoshong and waited for Ayrton and the others to catch him up before journeying on. By evening Ayrton’s horse refused to move on and food was getting short.

From then on the two walked “through the most unutterable sand.” He says they managed to shoot the odd wild bird: “not much perhaps between two men who had walked all day on two cups of coffee and a square inch of meal bread, but still something” and then as his own horse was so knocked up he left him at the next vlei with water.

“So on 12 July we started to do the remainder of the journey on foot. Ayton, lucky man, wore boots and gaiters; but I had only a pair of old riding boots which made walking very hard work. Our saddles and bridles we threw into a thicket…Two days later we arrived at the place where we had left the Colonels and the wagons.”

Next day Bethell tried to do some hunting for antelope, but nothing was spotted. They had some old giraffe biltong which they boiled and mixed the soup with some meal to make cakes on which they spread giraffe fat which was going rancid. They allowed themselves one cake per day and as they were walking 20 – 25 miles per day: “it may be imagined that we soon had most elegant waists.”

They came across a man setting alight the grass in order to bring on the fresh grass who told them there were plenty of goats nearby belonging to Chief Khama. They killed two and were soon surrounded by local people shouting for compensation. This went on for some time; Bethell and Ayrton only had 7/6 between them and the goats owners wanted 15/- apiece. Eventually they just filled their calabashes with water and left.

In the afternoon they were sitting resting when a native came along driving two oxen laden with dried meat, but he wouldn’t sell any so they continued walking until they reached water at sundown having walked about 48 kms (30 miles) They now re-united with their men from Pandamatenga and at a cattle kraal managed to barter Bethell’s blanket for a small goat.

A long dry patch of road lay ahead, the next water smelt strongly of hydrogen and their men constantly stopped to eat berries. “The consequence was that by the end of the second day’s walking we had only done about 40 kms (25 miles) our water was half done, we had next to no food and worst of all, the boys complained of their loads.”

Bethell and Ayrton turn back and send for help

After discussion Bethell and Ayrton decided to go back to the last waterhole and seek help. Four of their freshest men elected to go on to Shoshong and they were given a note for William Francis, the trader asking for help. It took a day and a half to get back; the local chief refused to help, but they manage to persuade some San Khoisan to take a note to Shoshong for £5 and settled down to wait for relief.

The place, Linokane, was one of Khama’s cattle posts having no huts and only a few thorn scherms to shelter from the wind and was inhabited by a few San Khoisan cattle herders under the supervision of one of Khama’s men. They lived on wild berries mashed up into a drink called Mabele which when mixed with grain fermented into an alcoholic drink. As Khama was very strict about alcohol, Bethell and Ayrton were sworn to secrecy about its use!

Life was very quiet for the two men although they got on friendly terms with Khama’s man who did what he could for them until, at last, on 3 August when one of the men ran up shouting “the wagons are coming” and after some time they heard a whip crack and soon a spring cart arrived driven by Trooper Woods of the BBP with relief supplies.

Rescued

Their messengers had taken five days to cover the 240 kms (150 miles) to Shoshong and Tpr Woods had taken another five days to reach them. They knew their bodies would not stomach much food after weeks of deprivation, but even porridge resulted in agonies of acute indigestion and flatulence.

Two days later they left Linokane on top of the cart; Bethell with a huge abscess on his foot and arrived back in Shoshong on 10 August. It appears that he was not healthy enough to resume duties in the BBP and soon after left for Mafeking and then England.

Some useful advice

Bethell’s advice to intending visitors to the Falls is as follows. “Whatever you do, go comfortably, with a wagon or two and possibly a water cart…Then make your will and distribute your loose cash among the deserving poor.” His last few pages contain hunting advice, but none of it was self-learnt; it is all quoted from F.C. Selous!

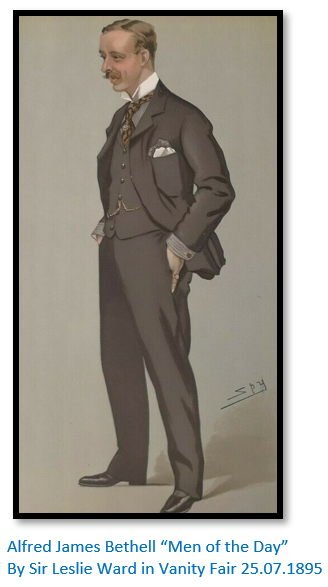

Alfred James Bethell (1862 – 1920) Life and career

Alfred Bethell was the youngest of five sons and went to Eton followed by Sandhurst and was commissioned into the 1st Battalion of the Northamptonshire, then in Ireland on garrison duty at Tipperary.

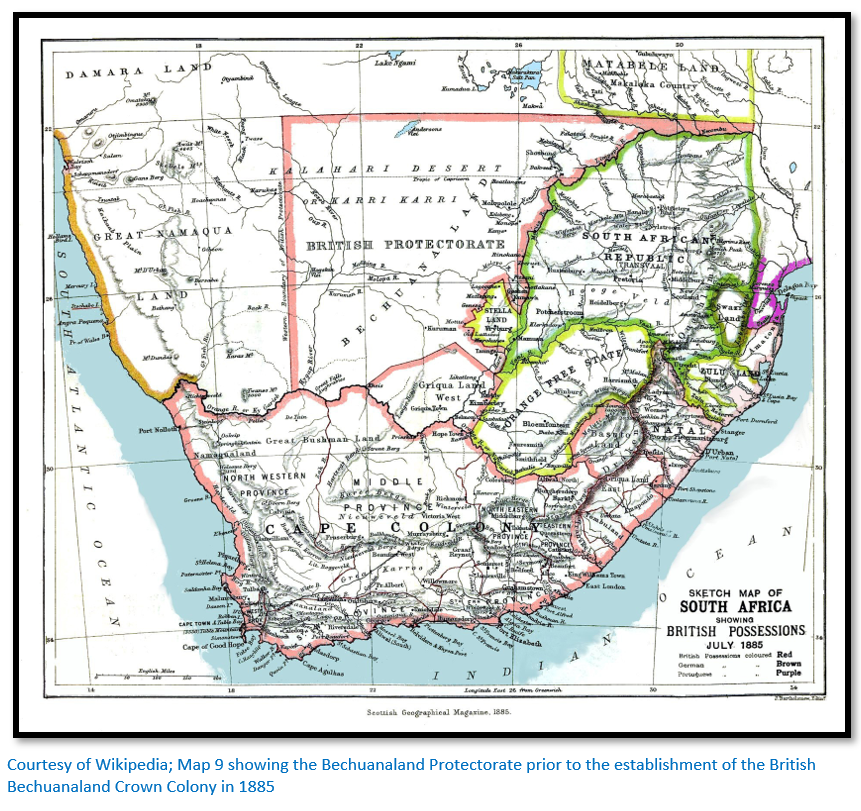

His brother Christopher, six years older, had been in Bechuanaland and was killed by Boers at Montsioa’s kraal near Mafeking in July 1884. The background to this was that there had been tension between the Boers and the Bechuana tribes for many years. The missionary road led through what became Bechuanaland and extended north to Lake Ngami and east toward Tati and Matabeleland.

The Boers strongly disliked their expansionist plans to the west being checked and to being hemmed in through the efforts of the missionaries of the London Missionary Society under Robert Moffat; this manifested itself in a Boer raid in 1852 on chief Sechele’s town of Dimawe (near Molepolole) and Livingstone’s mission at nearby Kolobeng was also pillaged.

The low intensity friction continued but became more aggravated when gold was reported by Karl Mauch at Tati in 1867 and increased numbers of traders and prospectors began to use the missionaries road. The 1881 Pretoria Convention set formal boundaries for the Transvaal Republic, but uncompromising Boers set up the two miniature republics of Stellaland in July 1882 with its capital at Vryburg and Goshen in October 1882 north of Stellaland near Mafeking. Both “republics” straddled the missionaries road.

German colonization efforts in South West Africa, now Namibia added to the anxiety and Rhodes actively campaigned for the Bechuana tribes to be assimilated into the Cape Colony. The Bechuanaland Protectorate was established with its territory extending to the Molopo river which included the two republics of Stellaland and Goshen.

John Mackenzie, the LMS missionary was the first Deputy Commissioner, but had no men or money to establish any law and order; he was succeeded by Rhodes in August 1884 who had no more success. The situation worsened when the Boers from Goshen attacked Montsioa’s kraal when Christopher Bethell was killed and the flag of the Transvaal Republic was hoisted at Mafeking.

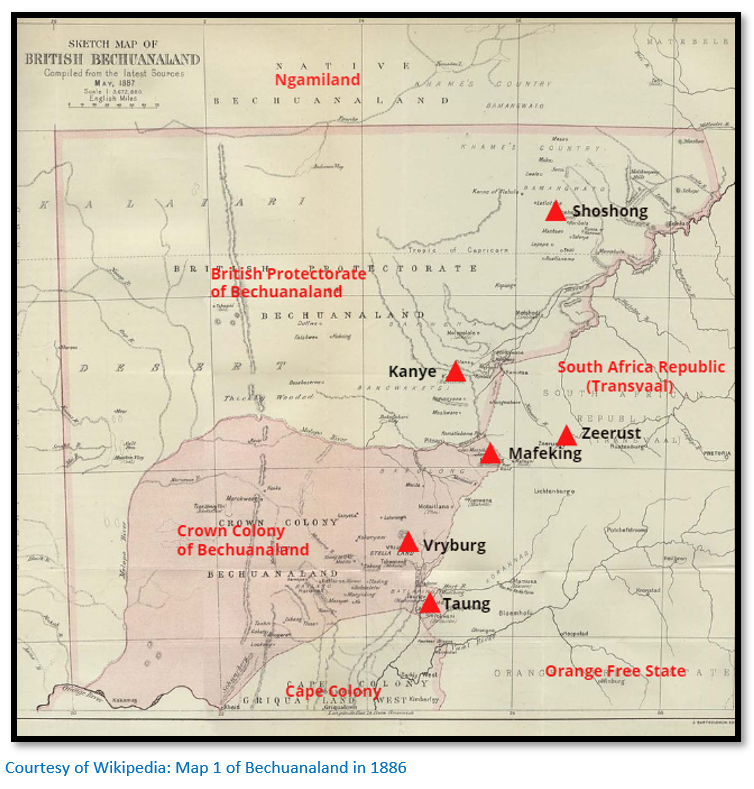

The Cape Government sent a military expedition under Sir Charles Warren to restore order and this succeeded without a shot being fired, the Boers simply fading away. The Bechuanaland Protectorate was then established in March 1885 to the north of the Molopo river and British Bechuanaland, a Crown Colony was established in September 1885 before being absorbed into the Cape Colony in 1895. (See map 1)

Christopher Bethell had come to South Africa in 1879 and was appointed adviser to chief Montsioa at Mafeking from where he kept Sir Hercules Robinson, the High Commissioner at the Cape, informed of the unfolding events in the area. Whilst defending Montsioa’s kraal with 100 of his tribesman against Boer forces he was killed on 31 July 1884. He had been wounded during the attack and was then shot dead by two Boers.

When Warren reached Mafeking with his military force Christopher Bethell was given a military funeral; the firing party being commanded by Captain E.G. Pennefather who later commanded the Pioneer Column [See the article Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Graham Pennefather 1850 – 1928 under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

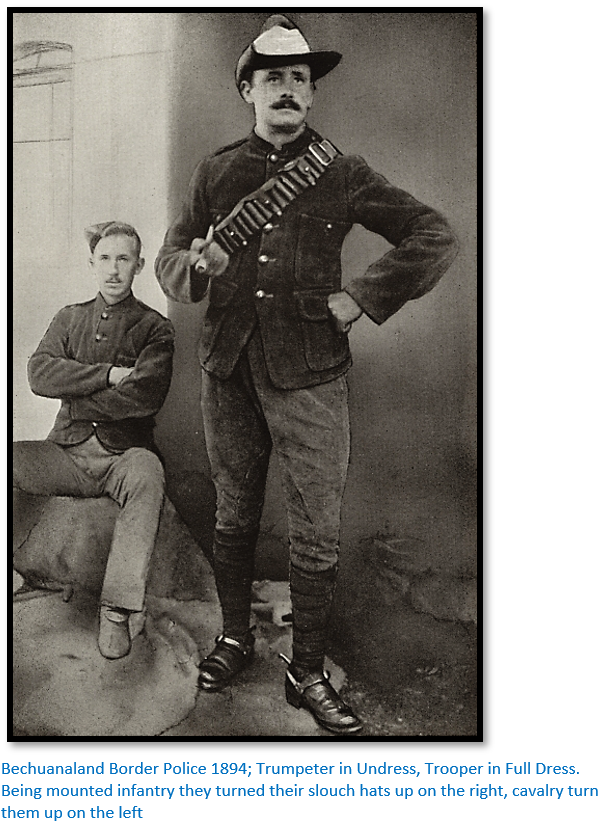

The policing of the vast area required the establishment of a new force and the Bechuanaland Border Police (BBP) was set up under the command of Lt-Colonel Frederick Carrington. The force comprised 500 mounted infantry with officers seconded from the British Army and most of the NCO’s and troopers from Sir Charles Warren’s force. This was the force that Alfred Bethell joined as Adjutant in 1885 aged 23 years old, a year after his elder brother’s death.

Much of the early work was in settling tribal boundaries and in December 1885 Bethell took ten troopers to Kanye to negotiate a treaty between two Bechuana chiefs.

Following his journey to the Victoria Falls Bethell quickly resigned from the BBP and the army because of poor health and returned to England. He married first Maud Bower in 1887 and after her death, he married the Hon. Elinor Lawson in 1918. It appears he managed a successful career in banking, became an MP and a Justice of the Peace living in Doncaster. He died on 23 October 1920 of pneumonia following influenza.

Acknowledgement

Most of the information on Alfred Bethell was researched by E.E. Burke, Director of the National Archives of Rhodesia in 1975 when the reprint edition of the book was published and obtained by me from the Foreword. Many authors and researchers owe thanks to E.E. Burke’s methodical and careful work over many years at the National Archives.

References

A.J. Bethell. Notes on South African Hunting. Books of Rhodesia Silver Series, Bulawayo 1976

E.C. Tabler. Pioneers of Rhodesia. C. Struik (Pty) Ltd. Cape Town, 1966

G. Tylden. The Bechuanaland Border Police 1885-1895. Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research Vol. 19, No. 76 (Winter 1940) P236-142

Wikipedia

[i] This is clearly based on the BBP uniform he was accustomed to and far too hot for general hunting

[ii] Lt-Col Frederick Carrington was selected to command in 1885 and most officers were seconded from the regular army

[iii] Both the Nata and Semowane rivers flow into the north of the Sua pan

[iv] Wikipedia states the last wild population of Quagga lived in the Orange Free State and the quagga was extinct in the wild by 1878, before Bethell undertook his hunting trip

[v] Thomas Fry was at Shoshong from about 1875 and used the Western Old Lake Route from Shoshong to Nwasha pan and Pandamatenga often. He was still trading at Shoshong in 1909 and died during the East African Campaign during WWI

[vi] For a description of Pandamatenga at the time which comprised about a dozen huts see the article George Westbeech and the road to Pandamatenga under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[vii] Pandamatenga was sited because it was outside the tsetse-fly belt. Travellers to the Victoria Falls had to travel on foot and take native carriers

[viii] George Blockley, trader, storekeeper and hunter entered Westbeech’s employ in 1871 and was in charge at Pandamatenga for the next sixteen years, probably the longest continuous residence of any European. Blockley met Frank Oates, Dr Emil Holub, Richard Frewen and the Jesuits and travelled to the Barotse country and Wankie’s kraal many times on trading missions. He was called “Little George” by all the Africans to distinguish him from George Westbeech. Like Westbeech he was a genial and friendly man and always gave great assistance to travellers. He died at the Zambesi in August 1887.

[ix] Croton oil is a foul-smelling oil, formerly used as a purgative, obtained from the seeds of the tropical Asian croton tree

[x] Quinine is a bitter compound that comes from the bark of the cinchona tree and is used as a malaria preventative

[xi] Neither Frank Watson nor Middleton have entries in Edward Tabler’s Pioneers of Rhodesia

[xii] Dr Holub was stuck at the Zambesi at the beginning of June 1886 unable to get porters until George Westbeech came to his rescue. He managed to travel about 260 kms (160 miles) north east of Kazungula before being attacked by local tribes. A servant Oswald Zoldner was killed and Holub lost everything except his notebooks. They struggled back to Kazungula where Frank Watson, Westbeech’s partner took care of them and Westbeech arranged for their passage to the south.

[xiii] The Jack snipe is a small, stocky wader bird found in Europe

[xiv] Bethell calls him ‘Sanzila’ but confirms on Page 60 that this is the same ‘Zanjueelah, the boatman of the rapids’ that Thomas Baines painted canoeing himself and James Chapman down the Zambesi above the Falls. The painting is featured in the article The First European Visitors to view the Victoria Falls before the end of 1880 under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[xv] At its widest Victoria Falls is 1.7 kms or 1.06 miles

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: