Photographs taken by the Reverend F.H. Surridge during the Pioneer Column’s 1890 trek into Mashonaland

Background to Reverend F.H. Surridge

Reverend Frank Harold Surridge (10 June 1862 – 4 May 1947) had originally gone to South Africa in 1883 and met Cecil Rhodes on the voyage and they remained friends. He was the Curate at Claremont, Cape Town and ordained a priest at Bloemfontein in 1890. On 26 May 1890 he accepted the post of Church of England Chaplain to the Pioneer Column.[1]

After the flag raising ceremony at Salisbury on 13 September 1890 and disbandment of the Pioneer Column, he travelled to Hartley Hills before leaving Mashonaland in 1891 and returning to England.

On 9 July 1891, soon after his return to England, Surridge delivered a lecture to the Royal Colonial Institute (an earlier iteration of the Royal Commonwealth Society), entitled 'Matabeleland and Mashonaland.' This talk was illustrated with lantern slides of which these prints are presumably the originals.

He was Curate at Holy Trinity, Ely from 1891-93 and then at Little Ouse, Suffolk 1893-98 before

travelling to India where he took up various chaplaincy’s until 1905. He then returned to England and served as Curate in Devon, London and Essex; retiring after serving as Vicar of Elsenham, Essex from 1926-32. He lived in retirement at Dovercourt in Essex, dying there on 4 May 1947. He married, but with no children.[2]

Skipper Hoste in his book Gold Fever makes some references to Rev Surridge, saying “At three o'clock on Sunday afternoon we pulled out of Kimberley in a Capе cart drawn by six troop horses. Being new to harness and very fresh into the bargain, we dashed off in great style, rattling along the dusty and pot-holed main street of the town in pursuit of Biscoe and his little band of brave men.

Borrow perched himself on the front of the cart and cracked his whip like an expert, while I sat beside him handling the reins. Our two passengers, the immaculate Dr Tabuteau and our dapper little parson, Surridge, clung on to the sides of the cart as it rocked and swayed over the bumpy road. However, there had been rain, and the horses soon found the going too heavy to keep up the smacking pace they had started with, so it was not long before we settled down to a more steady rate of progress.”[3]

And a few pages further on, “The following day being Sunday, our little chaplain, Surridge, held a service in the Court house. He gave the impression of being a little out of his element, and I could not help feeling that he would have been happier among a crowd of old ladies in an English country vicarage.”[4]

This from the following Sunday, “The next day being Sunday, and the inhabitants having asked our little parson, Surridge, to hold a service in the town, he came to me for a conveyance. He was a very horsey-looking man and always wore black elephant-cord riding breeches.

Taking him at his face value, I offered him a horse. When it was brought round Surridge appeared on the scene with a haversack containing his surplice slung across his shoulder and a loosely rolled umbrella in his hand. He climbed confidently into the saddle and the man who was holding the horse's head let it go. The horse was a bit slow in starting, so Surridge dug his heels into him. At the same time he bashed him over the ribs with the umbrella. This the old pug considered was going too far. He did not mind being kicked in the ribs - he was used to that - but to be lambasted with a brolly was an insult. Up went his back, he gave a couple of violent pig jumps, and the poor little cleric found himself flying through the air. Fortunately, the ground was soft, so he was not hurt.

However, I thought he might not be so lucky next time, so I had the cart inspanned and the rather subdued and dusty man rode to church in that. I later adopted this horse as my second mount. I gave him the name of Satan, partly because of his colour, black, and partly because of his dislike of the parson.”[5]

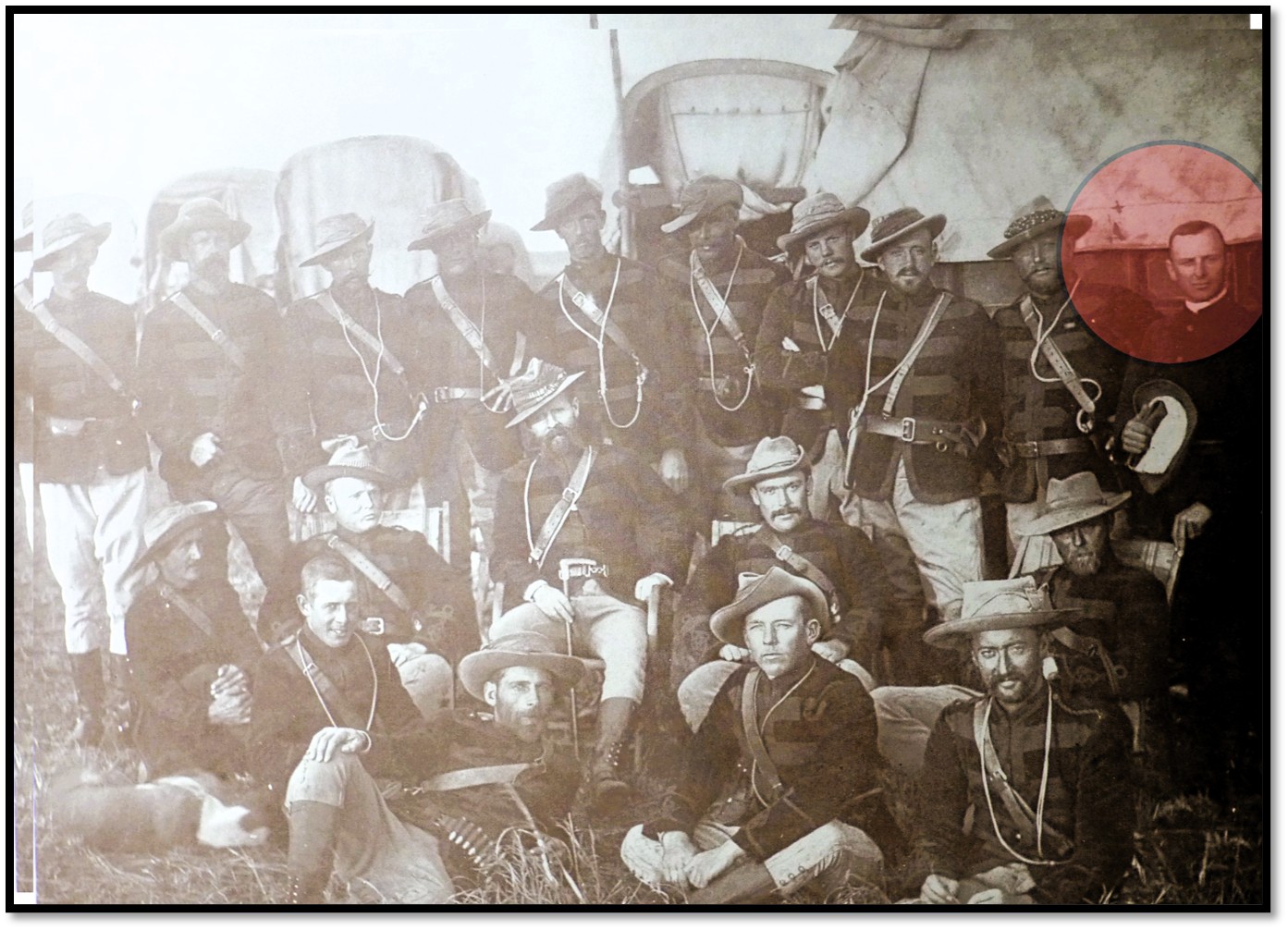

Ellerton Fry: Occupation of Mashonaland

Back (L-R) Lt E. O’C. Farrell, Lt F. Mandy, Capt (Dr) A.S.O. Tabuteau, Lt (Dr) J.W. Lichfield, Capt J.J. Roach, (C Troop) Capt H.F. Hoste (B Troop) Lt H.J. Borrow, Lt A.A. Campbell, Lt R.G. Burnett, Rev S.H. Surridge (Chaplain)

Centre (L-R) Lt W.E. Fry, Capt A.E. Burnett, Capt M. Heany (A Troop) Maj F.W.F. Johnson (O.C. Pioneer Corps) Capt F.C. Selous

Front (L-R) Lt E.C. Tyndale-Biscoe, Lt R.G. Nicholson, Lt R. Beale, Lt (Dr) J. Brett

Reverend Surridge’s photo album

The album (held in the Cambridge University Library) contains mounted prints measuring approximately 240 x 180 mm, with captions beneath the prints written in a fine copperplate hand.[6] The photographs show scenes taken between July and September 1890 during the Pioneer Column’s trek to Mashonaland in what was later to be Southern Rhodesia [now Zimbabwe] The sequencing of the photos in the album does not follow the progress of the trek and may reflect the order in which the lantern slides accompanying Surridge's lecture were shown.[7] However I have re-arranged the photos below so that they follow in date order.

The album contains 21 photos taken between the Umzingwane and Tokwe rivers during the Pioneer Column’s trek and covers the period 19 July to 9 August 1890. It’s a mystery why there are none of Fort Tuli preceding entry into Lobengula’s territory and the trek on the highveld after Providential Pass to Salisbury. Perhaps there were insufficient ‘wet plates’ or they were lost or broken enroute.

Many of the Rev Sturridge’s photographs have had the large areas of sky cropped out. His sub-titles to the photos are very brief and do not always agree with Ellerton Fry’s photos. To make the article more interesting I have added many of the sub-titles from the album of Fry’s photos published by Books of Zimbabwe entitled Occupation of Matabeleland: Views by Ellerton-Fry and also comments from the books by Adrian Darter and Skipper Hoste listed under references.

Ellerton Fry has many photos of the Pioneer Column’s journey from Mafeking to the training camp at Macloutsie to the construction of Fort Tuli on the Shashe river where the trek into Lobengula’s territory began. Here was their first encounter with the amaNdebele, “We had hardly finished. drawing up our laager when eighteen Matabele warriors, resplendent in ostrich plumes and golden crested crane feathers, crossed the river and came swaggering into our camp as if they owned it. They looked awful scoundrels, big hefty chaps, variously armed with stabbing assegais and guns of many patterns.”[8]

The Reverend Surridge has no photographs of the many laagers and scenes of the Pioneer Column. They are almost all of river scenes, kopjes and African kraals. Sometimes a few Pioneers pose in these photos, but perhaps they were there to encourage local natives to have their photos taken, or perhaps they helped the Reverend carry his camera equipment that was bulky and heavy.

Very likely he was a reluctant fellow traveller, not caring much to be included in the object of occupying Mashonaland, but under instruction from his Bishop to investigate the possibility of extending Christianity into Mashonaland. Inyati [Inyathi] Mission,[9] north of Bulawayo, had been set up by Robert Moffat and William Sykes of the London Missionary Society in 1859, but Lobengula did not approve of the missionaries seeking converts and no attempts had been made to spread the gospel in Mashonaland. Even in Ellerton Fry’s photo of the Column’s Pioneer Officers, Reverend Surridge is very much on the periphery.

Rivers are a frequent subject for both Ellerton Fry and Reverend Surridge and there are a number of reasons for this. River crossings often halted the column for several days. Crossing the Nuanetsi took three days as the spaces between the boulders had to be filled in with logs and sandbags and then topped with tarpaulins and then ox-wagons had to be helped across and steadied on this precarious causeway by The Pioneers themselves.

The cameras were very bulky and heavy cumbersome objects and difficult to manoeuver and recorded their images on ‘wet plates’ made of glass and coated with light-sensitive silver. Ellerton Fry writes that processing the plates presented its own special difficulties, “The development of my photos was rather difficult. As water was near at hand, I attempted it at night in my tent, but the searchlight playing all around our laager made it very trying…once I left some few plates, including one of Selous, in a stream of water. When I went the next morning, animals had been walking over them.”[10]

Cutting the road for the ox-wagons

On 6 July 1890, 'B' Troop paraded in full marching order on the parade ground in front of Fort Tuli.

Skipper Hoste[11] wrote, “When we had fallen in and had been inspected by the O.C. we marched off amidst the cheers of the rest of the column who had all turned out to see us off. Carrying the big axes with which we were to chop the road through the bush to Mashonaland, we rode across the sandy bed of the Shashi [Shashe] and landed on the other side. We were the first members of the expedition to enter Matabeleland officially.”[12]

Adrian Darter’s[13] description follows: “He (Selous) rode ahead on one of his fine hunters and pointed to a tree, a pioneer sprang to it and felled the obstacle. Should it be a forest giant, two men tackled it and Mangwato[14] boys steered its fall by means of a rope. These boys dragged aside the timber, for the orders were that the pioneers were to cut down trees only, so that Selous always had pioneers to issue orders to. The moment your tree fell, you walked rapidly past your comrades employed ahead of you and took your station behind Selous. He indicated an arboreal victim and you sacrificed it speedily. Hard muscular, glorious work, such as Gladstone loved…[15]

… We stood in awe of his boys, or more correctly, their guns, for many were armed with ancient blunderbusses, charged with slugs, and they would come up to one with the beastly thing full-cock and carelessly pointed. Sometimes they went off with a k-r-r-bang, a pioneer would jump and swear, but no one was hit and the dense forest could take all our language peacefully.

‘A’ and ‘B’ Troop of the pioneers cut the way right through from Tuli to Salisbury alternately day by day. This is ‘A’ Troop’s day - if you have never swung an axe, then you have lost the rhythm and music of its bite. They troop behind Selous in half sections. Right numbers dismount, strip off all accoutrements, rifle, hand axe, bandolier and tunic, attach them to their horses, rifle in gun bucket and held by wallet strap in front to steady it. Tunic, bandolier, haversack and water bottle strapped to the front of the saddle by wallet straps. Hand over your horse to your left number and line up. In shirt sleeves and riding breeches, booted and spurred, revolver at your waist, you stood, brawny and brown, to receive a large axe distributed to you and you move off to Selous waiting for you. His dexter finger is thrown out. You know your work. Meanwhile, the left numbers, leading the mounts follow on. In case of attack you have your revolver and axe which we were swinging with dexterity.”

Skipper Hoste writes prior to arriving at Macloutsie that, “To carry our kit and equipment 103 wagons spread out along a line five and a half miles long. The coloured and native drivers and leaders amounted to about 250. We had enough oxen to furnish two spans to each wagon, besides which we brought with us quite a respectable mob of slaughter cattle and a large herd of spare horses.”[16]

The Umzingwani (Mzingwane) was crossed on the 9 July and the column laagered on the north-east bank that evening.

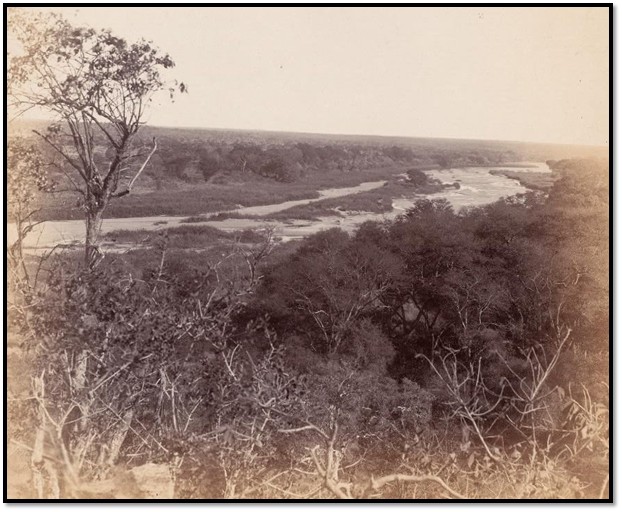

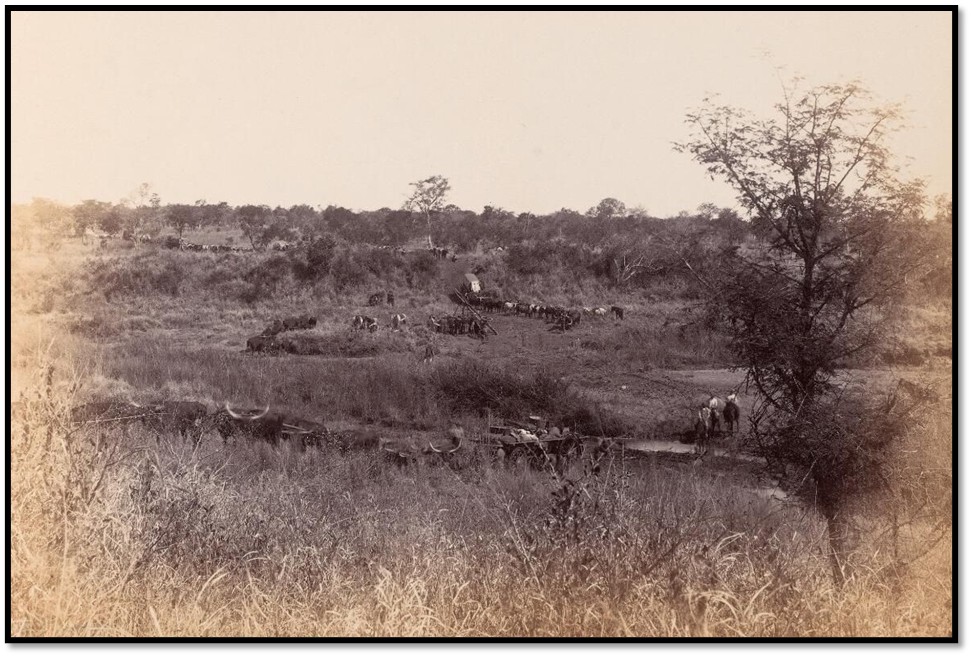

Rev Sturridge: The Umzingwani [Mzingwane] River.

The first major river to be crossed after the Shashe river. The Pioneers who were clearing the road sharpened their axes on the sandstone formation along the banks of the Mzingwane.

Darter writes, “As ‘A’ Troop had done the chopping, ‘B’ Troop would find the guards and pickets. Tonight and tomorrow ‘A’ Troop would supply the sentries. The column had now reached Umzingwane, 30 miles from Tuli. Umzingwane is a rapid running river and the heights of its banks tell of the body of water coming down in the rainy season. This river takes the waters of the Matoppo Hills and of Balla Balla of Matabeleland and flows into the Limpopo. On this river in Matabeleland, Gambo had a large kraal. He was one of Mzilikazi’s principal indunas. That was something to go to bed with here on outlying picket. But tomorrow we must cut a drift, for the banks of the river are steep. I am awake and Sergeant Suckling is getting ready to relieve sentries. You know the system, two hours on and four hours off, between 6pm and 6am.

Mine is the middle watch, troopers settle that by drawing lots and here at 2pm I am being marched to relieve Jack Grimmer.[17] We find Jack perched up a tree and ‘grousing.’ “What's the matter, Grimmer?” asks Sergeant Suckling.[18] “What the devil do the chartered company think of us, bringing us here as food for the Matabele or lions? A lion has been fooling round here for the last hour.”

Here was a cheerful prospect for me and I proposed to Suckling to dispense with this damned post. No good. He marched away, taking Jack with him who said, “You are going to have a lively time of it, Bert.” I had it. Intermittently between 2am and 3am an animal was sniffing around, sometimes near my legs. It was pitch dark, but at 3am the first glimpses of dawn would bring light on this subject, meanwhile that hour seemed ages, that beast too frequent in his visits, and I was in a cold sweat.

When it was light enough, I patrolled to the next sentry, who was Lionel Cripps.[19] He was as pleased to see me as I him and told me a hyena had worried him for the last hour, and he had but recently been able to distinguish it.”[20]

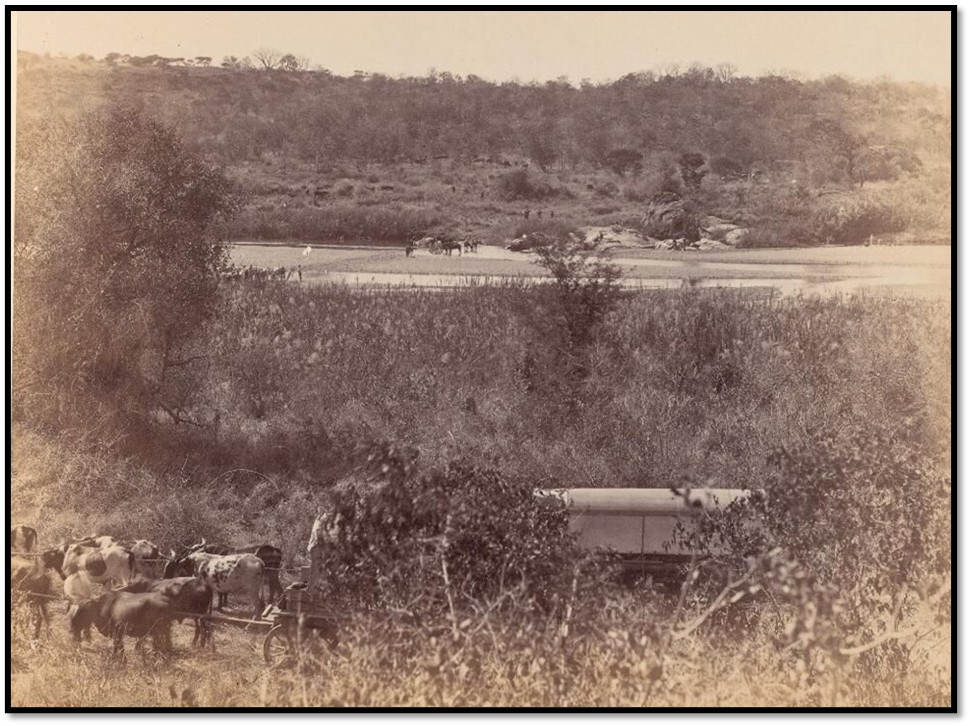

Rev Sturridge: The Umzingwani [Mzingwane] River.

“It was a difficult river to ford, so the wagons were taken across empty, and afterwards the goods were carried over by The Pioneers.” (William Harvey Brown) The normal span to haul an ox-wagon was 14-16 oxen, but to cross the bed of the Umzingwane double spans were often yoked together to cross the sandy river bed.

Frank Johnson laid out the daily routine on the march: “After we stood to arms at reveille, patrols were sent out about two miles on either side of the column to make sure there were no Matabele in the vicinity. On their return, we next broke laager, advancing about ten to twelve miles to our next camp, which had been prepared the previous day by the advance guard. We used to reach our new camp around 10am, after which we breakfasted. Orderly room followed. The cattle were kept outside the laager, our horses within.

Selous had with him one troop at a time as advance guard acting as protection to the Bamangwato natives, who did the actual work of cutting the road. Other patrols used to go out some ten to fifteen miles on our left and then work back. The natives were under the control of Radicladi, Khama’s favourite brother, who proved of great assistance in keeping his men under discipline, as they were inclined to be terrified of being attacked by the Matabele.

Every night, when the column was halted, the searchlight operated, its brilliant beams being directed into the sky and surrounding bush. At intervals I also had electric mines fired. But no shooting at all was allowed, in order not to create any false alarms. The only time this rule was relaxed was when we arrived at Fort Victoria, where there was open country around and there was no chance of the camp thinking that a shot might mean the alarm.”[21]

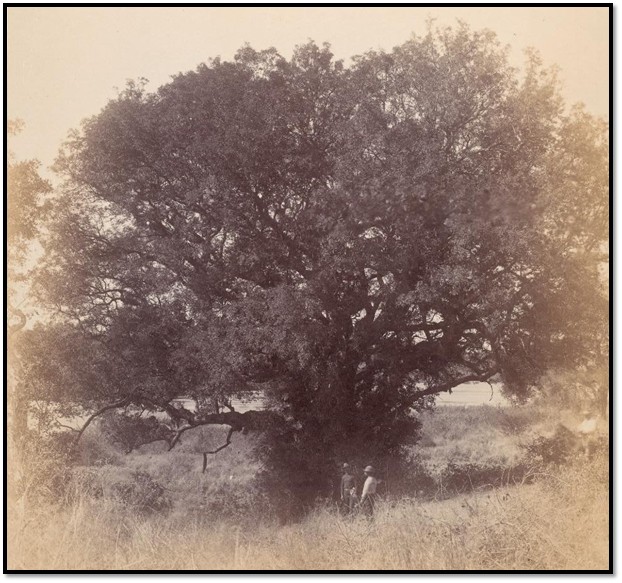

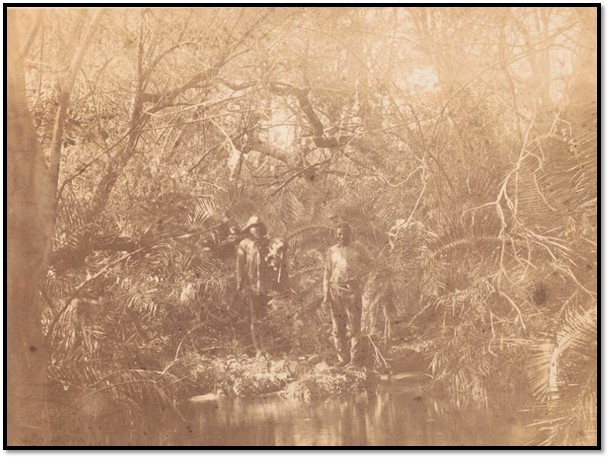

Rev Sturridge: timber on the Umzingwani [Mzingwane] River.

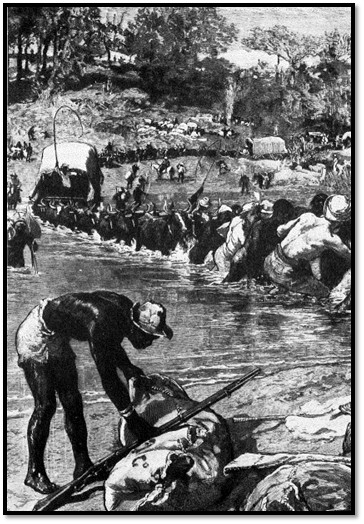

Many of Ellerton Fry’s photos were republished as sketches by the London Illustrated papers. However Victorian modesty did not include the naked bodies of the Pioneers assisting in the river crossings. Fry wrote, “When I returned to Mashonaland after my trip to England, I got my leg pulled for the Graphic had represented every one of us with a pair of bathing drawers on, whereas we were clothed as by nature.”

Ellerton Fry took a photo of the same tree labelling it: ‘Large thorn tree on banks of Umzingwane.’

The Pioneer Column crossed the Umshabetsi (Mtshabezi) river with its dry river bed with water running under the sand and then the Bubye and its tributary the Bubiana (Bubyana) rivers before crossing into Banyailand.[22]

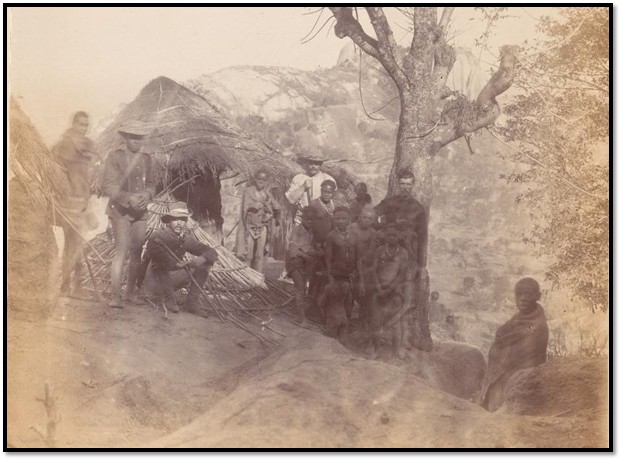

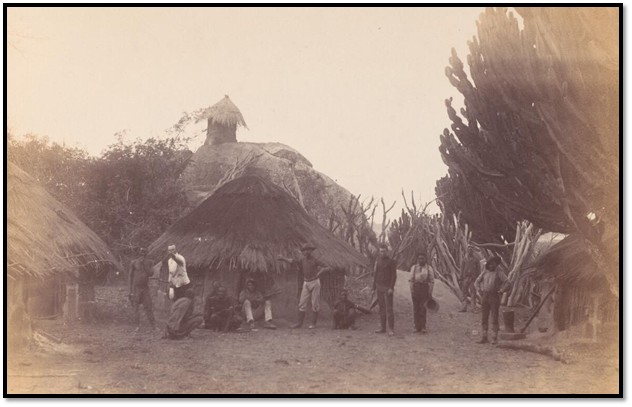

Rev Sturridge: Banyailand kraal on Mount 700 feet high.

This is the area described in Ellerton Fry’s photos as Matibi’s Mountain and Setoutse’s country. “On July the 25th we arrived at Matibi’s kraal and laagered for the day in a natural amphitheatre surrounded at some little distance by high rocky hills. The valley floor was covered with stunted, leafless trees, burned by the sun to a uniform grey.”[23]

Darter writes, “We have halted in the facility of Matibi’s kraal, who is a minor chief of the Banyai. This is the race that the Matabele easily conquered and despised. They are a broken abject race and live in irregular huts on granite kopjes. Their cattle, goats and fowls are very small. Matabele raiding and In-breeding has done this for their stock. The pasturage is good, the country, with its beautiful trees, and bold copies, picturesque.”[24]

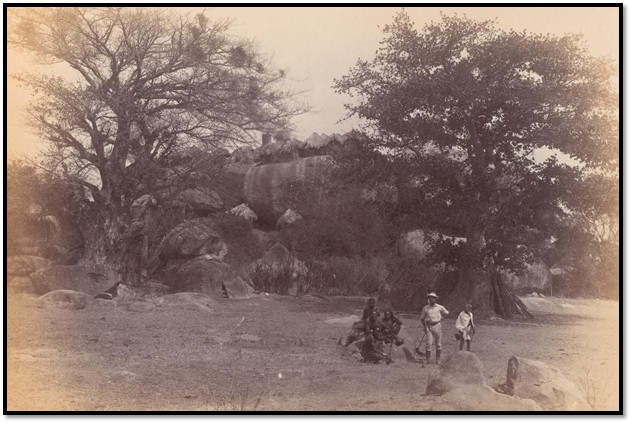

Rev Sturridge: Somoto’s kraal.

“The trail followed a winding valley between high granite mountains. On the tops of the mountains we could see groups of the wretched Banyai watching the column and wondering who we were and whether there was any chance of our presence breaking up the reign of terror which they had been subjected to for so long.”[25]

Johnson writes, “On July 26, Spreckley was appointed market master. Orders were issued that no purchases are to be made from natives without referring to the market master. A place will be fixed daily as a market, and all natives bringing supplies into camp will be directed to such place, and purchases made at rates determined by the market master.” Who?[26]

Rev Sturridge: Somoto’s kraal

High up among the rocks, in almost inaccessible places, these timid beings dwelt in neighbourly proximity to the baboons and monkeys. Their fields were in the valleys below, where they raised millet, mealies and melons. They owned sheep, goats and beautiful spotted cattle of a small breed. But the Matabele were in the habit of periodically raiding them, robbing them of their male livestock. (Frank Johnson}

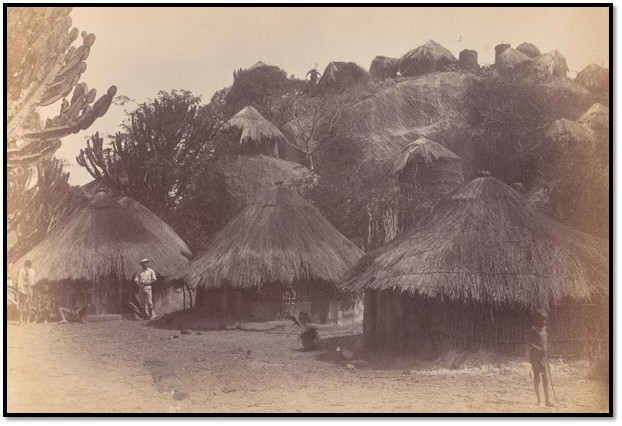

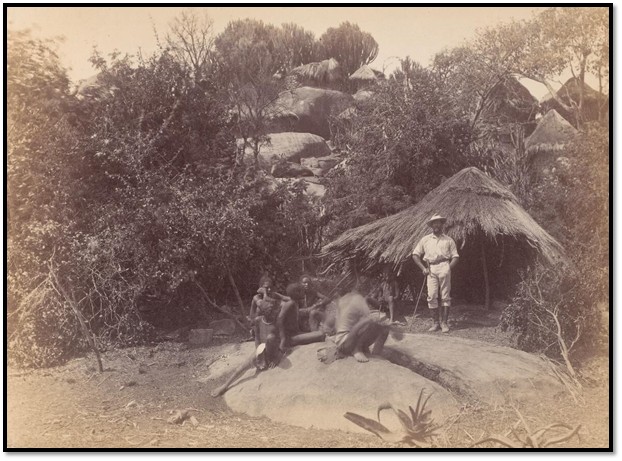

Rev Sturridge: Goto’s kraal.

“Their clothing is most scanty and their ornaments few, consisting chiefly of iron or brass rings and beads of various colours, the most fashionable being red, white eye, and pure white.” (Sir John Willoughby}

Stuck up in the most inaccessible places and disguised to look like the rocks in which they were scattered where the huts of the Banyai…They (Selous and his scouts) had visited several Banyai kraals and found the local natives in a miserable condition, most of them living in holes among the rocks like baboons.[27]

Rev Sturridge: Goto’s kraal

The small hut on top of the rock is for storing grain away from rats and mice.

In the daytime, when the column was halted, numerous natives would come to the laager, some with round baskets and others with calabashes of beer (mtuala) and tobacco. A sort of market-place would then be formed where they sold the produce they brought for pieces of limbo (blue or white calico) beads, or even empty cartridge cases., which as snuff boxes possess no mean value in their eyes. (Sir John Willoughby)

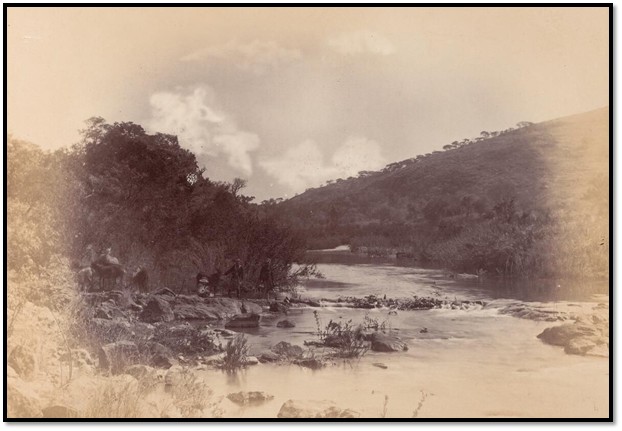

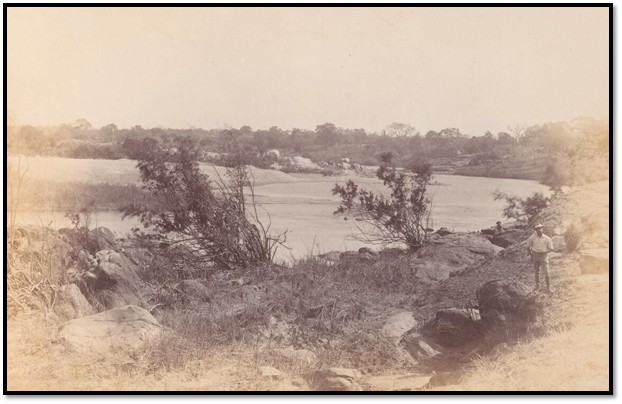

Rev Sturridge: Nuanetsi [Mwenezi] River looking west.

Hoste writes, “One afternoon a party of sixteen Matabele came across 'A' Troop, who were roadmaking ahead, and told them to quit work and go home. However, as no one paid any attention to their orders, they watched the operations for a bit and then went off and disappeared into the thick bush. The next day a party of twenty Matabele turned up while we were on the march. They were inclined to be cheeky, asking: 'What has the white man lost? Why are they looking for it in our country?" However, after a short parley they went off without declaring war.

These were the sort of questions we were becoming accustomed to hearing. They indicated that the Matabele were becoming restless at this invasion of what they considered their own private raiding territory. All we could do was to hope that Lobengula would be able to restrain the more excitable elements of his armies until we had reached the comparative safety of the high veldt tableland.

It was with a feeling of relief that we finally reached the Nuanetsi River on July 28th. The previous afternoon we had spent fighting a large grass fire that had come roaring down on us, and we were all as black as sweeps. We beat the fire, but we had no water to spare for anyone to wash with until we reached the Nuanetsi. In fact the only time we could ever afford a good wash was when we came across a river.

We found the Nuanetsi a broad stream running between high banks covered with large trees. Although it was only three feet deep it was running strongly and it took all day to get the column across. With the bleating of sheep and goats, the braying of donkeys, the neighing of horses, the lowing of cattle and the shouts of the herders the drift sounded for all the world like a noisy farmyard. It was not a very good drift, and many of the wagons stuck badly. While some of the men took the strain on ropes attached to the trek chains of the oxen, others in the river heaved and pushed at the wheels, coaxing the wagons over the more difficult places. It was hard work splashing about waist-deep in the swirling water, but in the end we got everything across without accident.”[28]

The Pioneers had to construct a makeshift causeway across the bed of the swift flowing Mwenesi as there was no visible natural drift across it. It took the entire column three days to cross the Mwenesi.

Darter has little to say about the Nuanetsi apart from, “Onward we go laagering, and then northwards until we reach Nuanetsi (Mwenezi) and have cut the road for more than 100 miles and the column halts to make a drift, for the Nuanetsi is a swift, flowing river with plenty of good water running over huge boulders, which the brawny pioneers roll aside to make way for the wagons. All the work in the rivers we do, whether the Bamangwato’ s fear the water, or the crocodiles I know not. They only dragged the timber aside that fell to the axes of the pioneers.”[29]

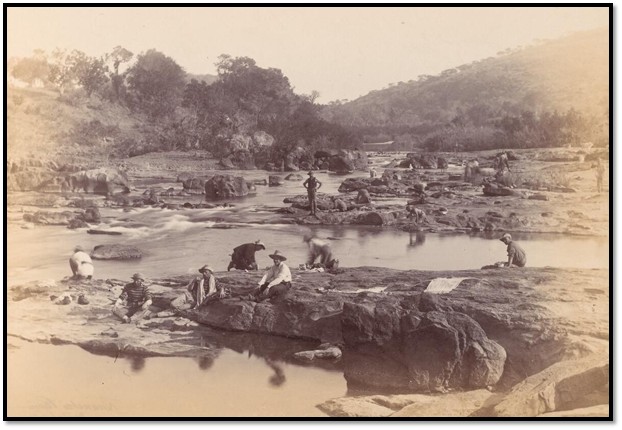

Rev Sturridge: Nuanetsi [Mwenesi] River

In this photo it looks like the men are taking advantage of the delay to wash their clothes in the rapids and dry them off on the rocks.

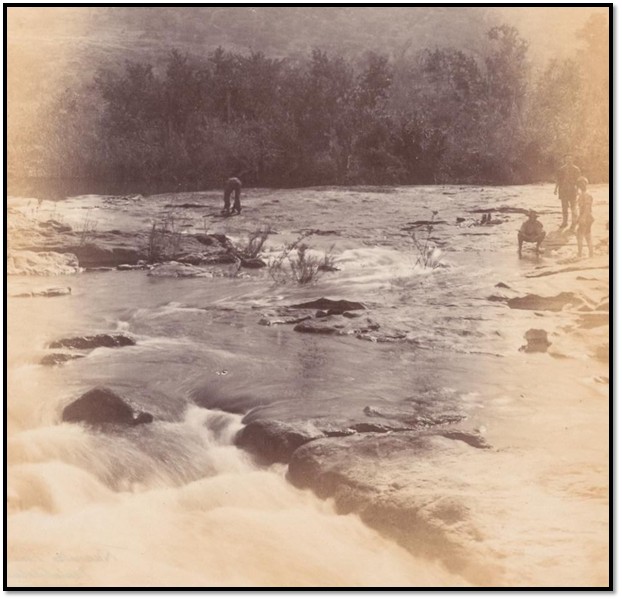

Rev. Sturridge: Nuanetsi [Mwenezi] River:

The relative slowness of Sturridge’s camera has blurred the waters in the picture. This problem was ever-present for Victorian photographers and their subjects were required to keep quite still to avoid the blurring result.

Ellerton Fry has a number of photos showing the Pioneers manhandling the ox-wagons across the newly constructed causeway.

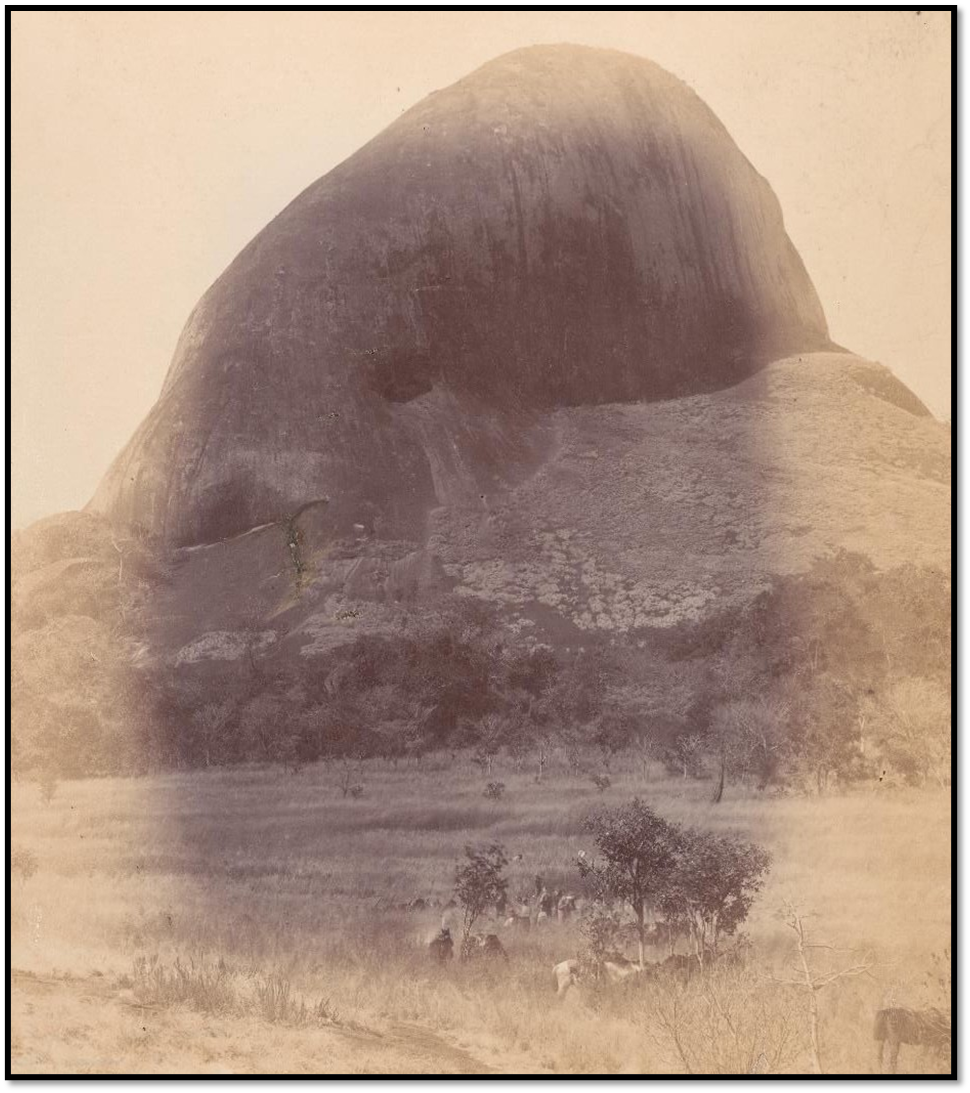

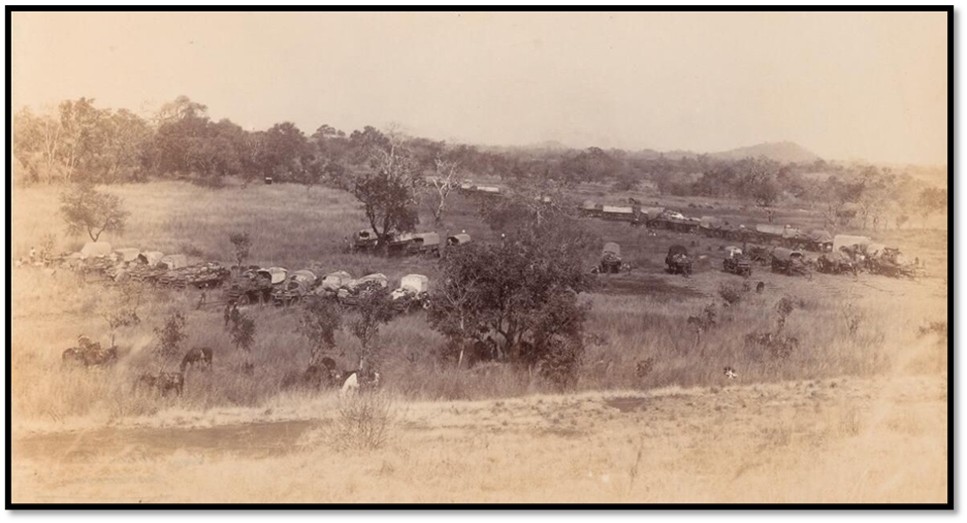

Rev Surridge: Savana Buli, 1,200 feet, near the Lundi River

Ellerton Fry’s photo is from a different angle and shows the Pioneer Column laager in the foreground. “The first day of August found us camped under a great solid rock which rose 500 feet straight out of the ground. Without a crack in it. It was known as the Svana Bula rock and had a decidedly Rider Haggardish appearance. About a third of the way up…was what might have been a hole or cave. The natives in the area claimed that it went right through to the other side and that it was not a natural hole but had been made by human agency in the far distant past.”[30]

Skipper Host wrote that the mountain was reached on 1 August 1890 and “looked like a huge thumb sticking out of the veldt.”

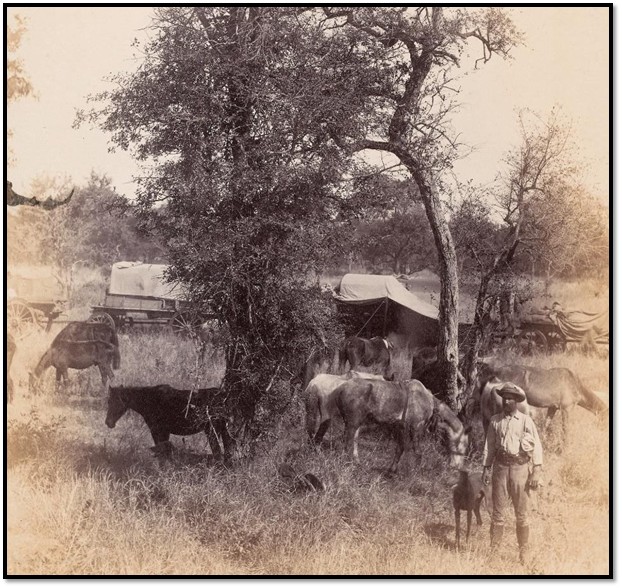

Rev Sturridge: In camp, Mashonaland:

The horses grazed around the wagons ready to be mounted in an emergency. The oxen would be grazing at a short distance from the laager under the watchful eyes of the herd boys.

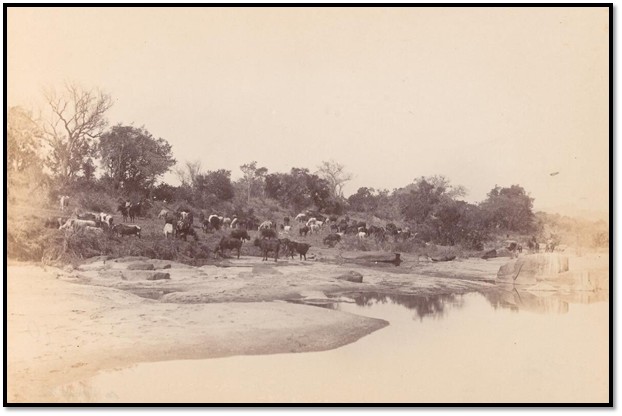

Rev Surridge: On Lundi [Runde] River

The Lundi [Runde] was the largest and most difficult river we had encountered on the southern side of the watershed, flowing into the Limpopo. The banks were not so difficult, but its several hundred yards of sandy bed were so treacherous from ‘quicksand’s’ that I finally decided to corduroy its entire length to ensure the safe passage of the transport. As this work involved the felling and transportation of such a large number of fair-sized trees, it was necessary to halt the column for two or three days. [Frank Johnson]

Darter accompanied Selous and a small escort to Chibi’s kraal across the Lundi and to the north-west. “It is situated on a kopje and can only be approached in single file along a footpath winding its way to the summit. We give over our horses to our half-sections and climb the hill. The Chief greets us and Selous returns the salutation. Selous and Chibi have an indaba. Chibi - which means headman - is seated outside his hut surrounded by his indunas. He tells Selous that he is head of all the Banyai and defines his boundaries, he also admits the supremacy of Lobengula and that he pays tax to him. Selous explains to him that Rhodes had a concession from Lobengula to seek gold and mine it, that the expedition is a peaceful one, that the road will be maintained through his country, but that the white men would on no account interfere with his people or their lands.”[31]

The next day Darter is summoned to the officer’s mess tent and invited for a day’s shooting. “Major Johnson. Captain Heyman. Captain Ted Burnett, Fred Langermann and I rode up the river in quest of hippopotami. About three miles up the river we came on a deep and likely pool, tethered our horses to the trees and took positions on the banks. We had to wait some time, for the burly brutes were shy. They have to come up to breathe though and presently nostrils protruded from the water and we fired. This is all you see of the hippo. You have to shoot quickly for the moment his lungs are filled with air down he goes.

We remained here a few hours and then rode further up where we came upon an immense lagoon festooned with reeds. We cooked and ate our lunch, watered and fed our horses and sought cover on the riverside. This was a hippopotamus home and we fired incessantly. The artful hippo could be seen pushing his nose under the reeds to escape observation. Major Johnson, having decided to get a more suitable position, forced his way among the reeds and later we heard a yell from him. On running to him, I ascertained that he had walked onto the back of a hippopotamus, indistinguishable from the slimy mud amongst the reeds. The hippo in astonishment had splashed into the water, upsetting Johnson. It was so ludicrous that I sat down in the mud and laughed heartily and the officers chaffed him for not ‘sticking to his mount.’”[32]

The next day we rode out, taking boys with us. The dead hippopotamus comes up after twelve hours. We found one hippo in the lower pool and as the carcass had drifted to shallow water and was easy to wade in and fasten the rope around the body and drag it ashore. Two others in the lagoon were brought out with equal facility. A carcass that had not being caught by the current was floating in mid-stream and I volunteered to swim out. Major Johnson said he would come also. Both of us stripped and plunged in, but we had not gone twenty yards when ‘Lookout Johnson, a crocodile near you.’ Burnett shouted. Major Johnson went back to swear at him. Burnett was getting even over yesterday's event. I went on, made a half-hitch around the hippo’s neck and mounted the carcass and together we were hauled to land. The Bamangwato boys pointed out the tooth marks of crocodiles on the hide of the hippopotamus, but - I have none on me.”[33]

Rev Surridge: The Lundi [Runde] River

Frank Johnson took the opportunity to hunt hippo whilst the riverbed was being ‘corduroyed’ and shot a number of the beasts upstream from the fording point; for days afterwards, the Pioneers enjoyed fresh hippo ‘bacon.’

Johnson noted, “The Lundi was the largest and most difficult river we had encountered on the southern side of the watershed, flowing into the Limpopo. The banks were not so difficult, but its several hundred yards of sandy bed was so treacherous from ‘quicksands’ that I finally decided to corduroy its entire length to ensure the safe passage of the transport. As this work involved the felling and transportation of such a large number of fair sized trees, it was necessary to hold the column for two or three days. Not only was there a considerable volume of water flowing over its sandy bed, but a short distance above the point selected for the drift there was a very large and deep pool in which a modern battleship could have been floated. This pool was the headquarters of a small herd of hippopotami, and I had once agreed to the request of Trooper ‘Curio’ Brown to shoot for him a specimen for the Smithsonian Institution, for which he was collecting. We got a fine animal ashore with the aid of a span of eighteen oxen pulling through a block, with differential tackle secured to a big overhanging tree. Brown and I were kept busy during our stay at the Lundi, removing the skin completely with the huge head and cleaning the latter. I believe the specimen is still in the museum at Washington. The ‘corduroying’ completed at last, we got through the Lundy without much trouble.”[34]

Skipper Hoste writes, “At eight in the morning of August 3rd the first wagon entered the water. The sky was overcast and the water looked far from inviting, but by now we were getting quite accustomed to fording rivers. All hands, with the exception of outposts, were on the job, most of them stripped to the bare buff. The shouting, splashing, cracking of whips, intermingled with yells of laughter and assorted farmyard noises, was simply deafening during the four hours we were crossing.

Pausing for breath after helping to ease the wheel of a covered waggon over an underwater obstacle, Borrow noticed the doctors and chaplains sitting comfortably inside. “Do you realise there are dry men in this wagon?” he asked the man next to him. “We'll see about that.” Without more ado, the naked men in the river assailed the wagon and dragged the protesting men into the icy water.

Hosking, the hospital orderly, resisted fiercely, but finally, overcome by numbers, he was ducked, swearing eternal vengeance on his tormentors. Eventually, after much heaving on ropes and pushing of wheels, the last wagon was across and the laager on the north bank completed by noon.”[35]

Rev Surridge: Ruins on the Lundi [Runde] River

Ellerton Fry also photographed these ruins on the northern bank of the Runde River. The Pioneers found iron and old slag inside the ruins, indicating that an iron smelting furnace had been operated there.

“Old Rocky Mountain Thompson, who had been prospecting round the Lundi some years before, told Biscoe and me where we could find some ancient ruins about two miles from the camp. As we were both off duty that afternoon we rode off to look for them. We found them without much difficulty.

They were small and, of course covered with creepers, but in a wonderfully good state of preservation. They consisted of a circular wall surrounding what appeared to have been either a sacrificial altar or a smelting furnace. I rather fancy it was the latter as, round about it, mixed with the sand, we found a considerable amount of fragments of ashes and charcoal. We hunted through the debris and found some iron ore and slag.

The curious thing about the ruins was that though they were evidently built by people of a certain degree of civilisation we could discover no inscription of any kind about them to tell who or what kind of people had used them. it The outer wall was very well preserved and almost perfect. In one place it had a sort of rough ornamentation on it formed by placing the stones in different patterns. It stood about six feet high and the inner wall was a few feet higher. Except for two entrances they were joined together, so that the outer wall, which was about five feet thick, formed a terrace with the inner wall at the back of it.

The local natives seemed to have no idea who had built them. They had been there, they said, before their forefathers had arrived in that country many hundreds of years before.”[36]

Rev Surridge: The Tokwani [Tokwane] stream

Rev Surridge: On the Tokwani [Tokwane] River, Mashonaland

Rev Surridge: near Tokwe River, Mashonaland

The night they crossed the Runde river and not far from the Tokwe river Johan Colenbrander[37] arrived from Bulawayo at midnight, bearing a dire warning from Lobengula that if the Column did not turn back, the Ndebele would rise like the ‘sand in the desert.’ Four Pioneers, including Johnson, Selous and a prospector called Cherry were to be taken alive and skinned. Colenbrander reported that Lobengula did not want a war, but he had difficulty in restraining his hot-blooded warriors. When Colenbrander left the next day, he considered the unmoved pioneers doomed.

Ellerton Fry found some of the reactions to this ominous warning amusing and wrote. One man (I will not mention his name} was always to be found like a walking arsenal, revolver, bowie knife and no end of things on his person.

Hoste noted, “After a hard morning chopping we arrived at the Tokwe River at noon on August 9th. We inspected it and found a place where, though there was a good deal of water, we could make a good drift by blowing up some rocks that were in the way. We had everything we needed in the way of drills, hammers and dynamite in our scotch cart, so we got to work at once. Five of us spent four hours in the river, stark naked except for our hats, hammering away putting holes for the charges into the rocks.

I was working away at one hole, up to my neck in water, when Colonel Pennefather rode up and asked for the Officer-in-Charge. 'Yes, sir?" I answered. He looked slightly shocked but he made no remark about my sketchy costume. 'How are you getting on?" he inquired. 'We'll be finished by nightfall,' I answered. The next morning the men had breakfast early and as soon as that was over the wagons began crossing the river.”[38]

Darter writes, “We doubled our sentries on this night of August the 10th that followed the day of Lobengula's message. Colenbrander had stated that the King [Lobengula] had great difficulty in holding back the young soldiers and if he had given the command, they would be on their way now. Sergeant-Major Mahon posted the sentries himself that night and I do not think it would be easy to find another man more energetic in keeping a man alert by pointing out the danger of his post. He showed me the exact spot the Matabele would come from - a break in the hills - and left me on tenterhooks for two hours. On meeting the other sentries, on turning into my blankets, I found that he discovered a Matabele spot in front of each of their outlooks. He certainly was a champion for scaring a young soldier into alertness.

The searchlight was in play all night, throwing its rays on the hills across the bush, up to the heavens and back again. In the morning, we greeted the sun and its penetrating rays with joy, but the bush gave no sign of the tread of Matabele, nor was there a glimpse of their war paint.”

We had to sandbag the Tokwe, for it was a swift torrent. The waters swirled the bags out of line and sent them yards down the river. There were boulders at hand and these we dropped in the river until we had formed a ledge and behind these replaced the sandbags. Once we had formed this, it was easy to place the other sandbags, but it took some time to gain a footing for the first layer.

We crossed the Tokwe and the country ascended rapidly to a pass ahead of us. There was a strain of anxiety easily discernible on every face, whether officer or trooper. That pass had to be made and we were making for it and the road was being cut through it to the north, but who knows that in that wooded pass the Matabele may be lurking in ambush? With the column extended on a steep gradient, with frowning hills on each side for the enemy to rush down from, we were in a predicament that was not good to contemplate too long over.

It was an ideal spot for a ‘wipeout’ but as we were in the position to supply the sanguinary matter It made all the difference. We could not make the way through the pass in the day. We laagered halfway and manned the wagons.

That night the searchlight scanned the crags and sides of the mountain. Few of us slept, and a hand was constantly extended to assure yourself that your bedfellow - the Martini-Henry rifle was warm and in close proximity. The non-commissioned officers too, would appear suddenly and reassure themselves of the readiness of the men…

We got through and with fervour named the pass Providential Pass.[39]

The Graphic, 25 Oct 1890: All hands help to get the wagons across the Lundi

Rev Surridge: Forest scene, Mashonaland.

References

Occupation of Mashonaland; Views by W. Ellerton Fry. Books of Rhodesia. Bulawayo, 1982

R. Cary. The Pioneer Corps. Galaxie Press, Salisbury 1975

A. Darter. The Pioneers of Mashonaland. Books of Rhodesia. Silver Series, Vol 17. Bulawayo 1977

H.F. Hoste, Edited by N.S. Davies. Gold Fever. Pioneer Head, Salisbury, 1977

F. Johnson. Great Days; the Autobiography of an Empire Pioneer. Books of Rhodesia Volume 24, Bulawayo 1972

[1] Reverend Father A.M. Hartmann, S.J. was Chaplain to the Roman Catholic congregation

[2] The Pioneer Corps, P55

[3] Gold Fever, P20

[4] Ibid, P22

[5] Ibid, P27

[6] Cambridge University Library reference is RCS/Y3052B and found on the website at: http://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-RCS-Y-03052-B/1

[7] The text for the lecture is printed in: Royal Colonial Institute (1891), 'Matabeleland and Mashonaland', 'Proceedings of the Royal Colonial Institute', vol. XXII, pp.305-331, London: Royal Colonial Institute. The album was presented to the Royal Colonial Institute in June 1891.

[8] Gold Fever, P42

[9] See the article Inyati and the activities of the London Missionary Society in Matabeleland from 1859 under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[10] Occupation of Matabeleland, Intro Pix

[11] Henry Francis ‘Skipper’ Hoste (1853 – 1936) attested on 26 May 1890 as a Captain of ‘B’ Troop. Failed entry into the Royal Navy and apprenticed into the Merchant Navy eventually promoted to commodore of the Union Steamship Company and on RMS Trojan met Rhodes in August 1889. After arriving at Fort Salisbury, he was in charge of the flag raising ceremony on 13 September 1890. Prospected and mined in Mashonaland and took part in the battle of Massi Kessi (Macequece) Went diamond digging at Somabula. Resigned commission in the 1893 invasion of Matabeleland. Two i/c to Col R. Beale on Relief Column to Bulawayo in 1896. Pall bearer at Rhodes funeral in 1902. Cattle inspector at Essexvale retiring in 1930. Died Salisbury 13 Jan 1936.

[12] Gold Fever, P45

[13] Adrian Darter attested into the Pioneer Corps on 7 May 1890 as a trooper No 86 in A Troop. After the disbandment of the Corps he joined a prospecting syndicate. Was present at the battle of Massi Kessi (Macequece) in May 1891 against the Portuguese but left Mashonaland in 1892 after a bad bout of blackwater fever. Returned in 1896 serving in the Matabeleland Relief Force (MRF) under Vol Plumer. Lived in Bulawayo serving in the Rhodesia Regiment in the Anglo-Boer War and was present at the Relief of Mafeking. Served in the Middlesex Regiment in WWI.

[14] Radikladi, Khama’s brother, was in charge of the 270 Bamangwato. 200 of them helped in the road cutting and 70 were mounted and acted as scouts

[15] The Pioneers of Mashonaland, P66

[16] Gold Fever, P34

[17] John ‘Jack’ Robert Grimmer. One of Rhodes’ Apostles he attested into the Pioneer Corps as No 171 in B Troop on 14 July 1890. He was Rhodes’ private secretary in 1891, served as a Corporal in the Salisbury Horse in the 1893 invasion of Matabeleland and in te Grey’s Scouts in the 1896 Rebellions. Became manager of Rhodes Nyanga Estates in 1897. May have been the last person Rhodes spoke to on his death in 1902. See the article The death of Cecil John Rhodes at his Muizenberg cottage in 1902 under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[18] Edward Horace Walpole Suckling attested into the Pioneer Corps No 51in April 1890 as a Corporal but was promoted to Sergeant. Served in Natal Mounted Police and Bechuanaland Border Police (BBP) After disbandment partnered W.H. Birkley in a Pioneer Street butchery until Dec 1892. Member of a syndicate with E. Tyndale-Biscoe with claims at Mt Simoona near Bindura. He was fishing with dynamite when a stick exploded in his hand destroying his hand and blinding him. Died at Mazoe 28 May 1893

[19] Lionel Cripps C.M.G. attested into the Pioneer Corps No 133 on 7 May 1890 into A troop. Came from India to Port Elizabeth in 1880, worked in a store 1880-84, then farmed at Somerset East 1884-7 before prospecting at Klerksdorp and the Rand 1887-89. After the Pioneer Corps was disbanded joined a prospecting syndicate at Mazoe and pegged the Jumbo and Golden Quarry gold mines. Worked 1892-3 as a compound guard at Kimberley Diamond Mine before moving to Umtali and farming as well as working alluvial claims at Penhalonga. Represented the Eastern Districts on the Legislative Council in 1914 and Bulawayo 1920-3. Elected first Speaker of the Legislative Assembly 1924-35.

[20] Pioneers of Mashonaland, P72

[21] Great Days, P137

[22] Two Boers, Louis Adendorff and Klein Barend Vorster claimed to have a Banyailand concession from the two chiefs covering an area of 200 miles by 100 miles and when Rhodes refused to purchase the concession, ambitious plans took place to gain by force what had been lost through diplomacy although it may have all been a scheme to blackmail the BSACo. The plans were for 1,500 – 2,000 Boers to cross the Limpopo river at Middle drift during the 1890 dry season and the stated reason was that Chiefs Chivi and Matibi of Banyailand needed protection against amaNdebele raiding parties. For more information see the article The Adendorff trek and the planned invasion of Banyailand under Masvingo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[23] Gold Fever, P52

[24] Pioneers of Mashonaland, P77

[25] Gold Fever, P53

[26] Great Days, P138

[27] Gold Fever, P48

[28] Gold Fever, P54

[29] Pioneers of Mashonaland, P81

[30] Gold Fever, P55

[31] Pioneers of Mashonaland, P85-5

[32] Ibid, P86-7

[33] Pioneers of Mashonaland, P87-8

[34] Great Days, P138-9

[35] Gold Fever, P56

[36] Gold Fever, P56

[37] Johan Colenbrander was the BSAC representative based in Bulawayo

[38] Gold Fever, P59

[39] Pioneers of Mashonaland, P91-3