Karl Mauch, explorer and geologist and the man who claimed to be the first European to visit Great Zimbabwe

Summary

Karl Gottlieb Mauch (1837-75) was well-known in Southern Africa as the first European to publicise the gold-fields of Tati district and Hartley Hills (the Northern goldfields) and to describe Great Zimbabwe, but soon after his death he fell into obscurity. During his lifetime he prepared a number of geological maps of Southern Africa and although they were used locally they do not seem to have been published.[i] Rogers states that his ambitions were really beyond his means, but he displayed great determination and energy in the pursuit of those ambitions and provided much geological data and information for those that followed him.[ii]

We’ll see in the article that he did not discover the Tati and Hartley Hills goldfields; he publicised them and he was not the first European to visit Great Zimbabwe as he claimed, but he did inform the world of these finds which provided the stimulus for further European exploration of the area then called Zambesia. Adam Renders, the hunter who lived just three and a half hours walk away for three or four years prior to Mauch’s arrival is the most likely first European visitor and it was through his contacts with the local VaKaranga communities that he was allowed to guide Mauch to Great Zimbabwe; but he never left any written account himself and Mauch wrote him out of the history books.

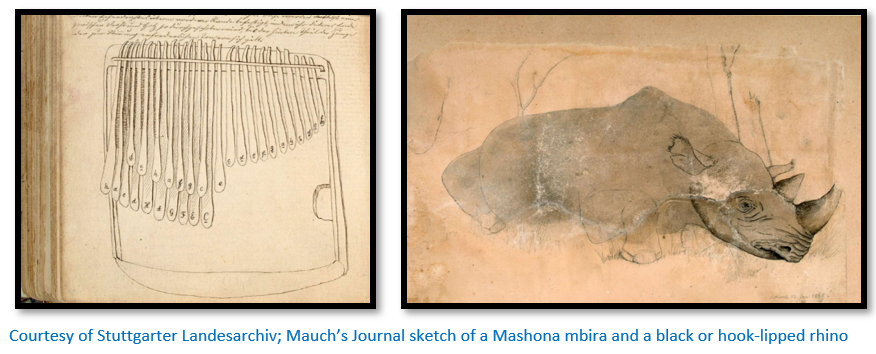

Gerald Mazarire states that Mauch’s Journals during the ten months he was present in the vicinity of Great Zimbabwe are indispensable as a primary source: “More critically, however, it stands distinctly at the centre of any debate on the history of the VaKaranga in particular, and is indispensable as a contemporary eye-witness account of their pre-colonial life at its most volatile period.” The Bernhard’s translated over fifteen pages of ethnography of people Mauch calls the Makalaka, in reality they are VaKaranga.[iii]

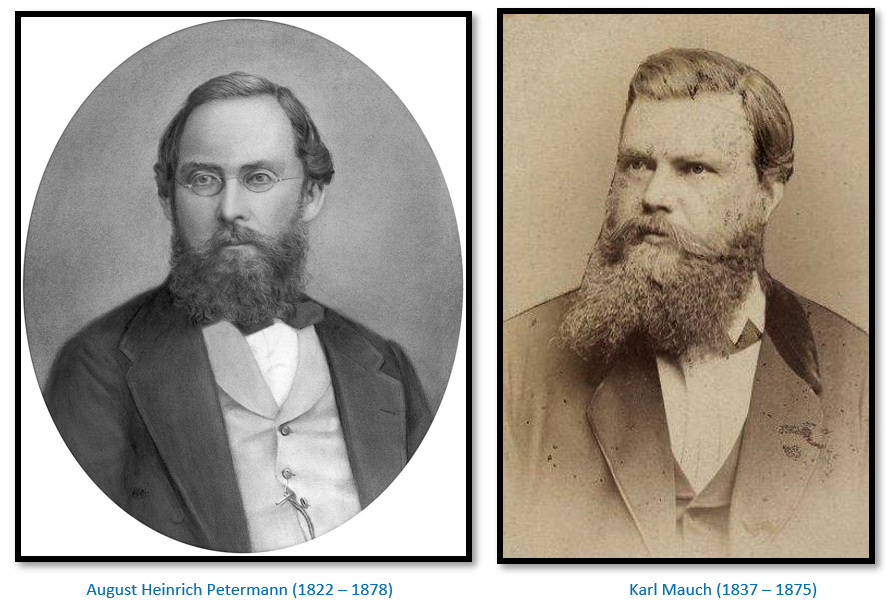

F.O. Bernhard describes Mauch as: “adventurous, stubborn, tough and unfortunately, rather vindictive.” He goes on to say that one reason why Mauch fell so quickly into obscurity after his death may be that Dr Petermann was: “sorely disappointed once he met Mauch in person on the latter’s return to Germany in 1873 for Mauch was by then a poor physical wreck and the state of his mind may be gauged when one reads the latter part of his journals.”[iv]

Early years

Karl (sometimes Carl) Gottlieb Mauch, born 7 May 1837 at Stetten im Remstal, Württemberg, Germany was the son of Joseph Mauch and his wife Christiane Dorothea née Greiner. Rob Burrett writes: “His obsession for African travel was inspired when at the age of fifteen he was given a school atlas for Christmas. What captivated him were the ‘blank spaces’ that constituted the then European knowledge of the interior of Africa.”[v] He finished a good school career at Realschule in Ludwigsburg and at seventeen years old attended the teacher's training school at the Franziskaner in Schwäbisch Gmünd in Württemberg from 1854 to 1856.

After this he became an assistant teacher at Isny (just east of Lake Constance) where during visits to the botanical garden at the University of Graz he became particularly interested in African flora. “I started a collection of insects, an herbarium and a collection of minerals…By walking six or more miles each day, in every season, over any ground, often without food or drink til my return to the point of departure and always wearing the same warm clothes, I have tried to steel my body”[vi] Despite having few means and without special training in any branch of science he had good health and determination and set his mind on a life of exploration for which he started reading travel books and learning some English, French and Arabic. In 1858 he moved to Marburg to become a tutor and for three years studied botany, geology, mathematics, medicine and foreign languages on his own.

Preparations for travel in the African interior

In 1863 he contacted by letter the map publisher Dr August Petermann, a great benefactor of geographical discovery, who promised him financial support and to publicise his work for a planned exploration of southern Africa. Mauch resigned his post as tutor that year and spent five months in London improving his English and his knowledge of plants, animals and minerals. Rogers quotes Mauch’s biographer as saying Mauch prepared himself for a traveller’s life in Africa by taking snakes to bed in order to prepare himself for similar situations in Africa! Then he applied for a job with a shipping company and went to sea in 1863-4 before travelling to South Africa as a sailor on a German ship, arriving in Durban in January 1865.

Geology and mapping in the South African Republic (Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek; the ZAR; also known as the Transvaal Republic)

Mauch initially worked as a labourer and teacher in Pietermaritzburg, Natal before accompanying the trader Carl Pistorius by foot and ox-wagon to the South African Republic (Transvaal) and in his journal gives graphic descriptions of life on the road, the farms they passed, the herds of antelope and the ever-present danger of losing one’s way out of sight of the wagon road. Crossing the watershed between the Limpopo and the Vaal rivers he noted that the highest part was called the Witwatersrand: "from the bleached limestone which occurs about the strong streams and springs."

He noted the siliceous limestone, or dolomite, which he found stretching over a great area as far as Marico and Likatoon and explored with companions some of the caves and underground passages in the dolomite and recorded a subsidence near Wonderfontein which made a diversion of the main road necessary.

In 1865 Mauch explored the country from Rustenburg and later from Potchefstroom on foot meeting with a good deal of unfriendliness from suspicious farmers but was not diverted from his task. North of Rustenburg the Pilanesberg mountains, an ancient volcanic crater drew his attention but his journey was complicated by lack of supplies and he lost his way although he managed to prepare a preliminary topographical map of the Pilanesberg noting: “some of the hills are made of a violet-brown quartz-porphyry and that fluorspar, red copper-ore, magnetite and gneiss occur there.”

From Rustenburg he moved onto Potchefstroom where he met a fellow German, Friedrich Jeppe, who was at that time acting postmaster-general of the Transvaal Republic[vii] and working on a map of the Transvaal. Jeppe’s later geographical / geological maps earned him the reputation of being the most important cartographer in the Transvaal and he introduced Mauch to A. Forssmann, a merchant based in Potchefstroom who funded and greatly facilitated Mauch’s travels in the Transvaal, but in common with many other Mauch benefactors received no acknowledgement for his assistance. With Potchefstroom as a base Mauch explored the Transvaal keeping a journal in which he described the geology and geography with notes on the natural history and the human inhabitants.

He left Potchefstroom after two and a half months for the Marico district to escape being drafted for commando service against Moshoeshoe in the Basuto war writing: “it would however be awkward to be posted with half-civilised peasants and to be forced as a “Buitenlander” (collective name for non-Afrikaner) to do what they do not want to do.”[viii] Returning to Potchefstroom he had an unpleasant journey in company with a crowd of young Boers.

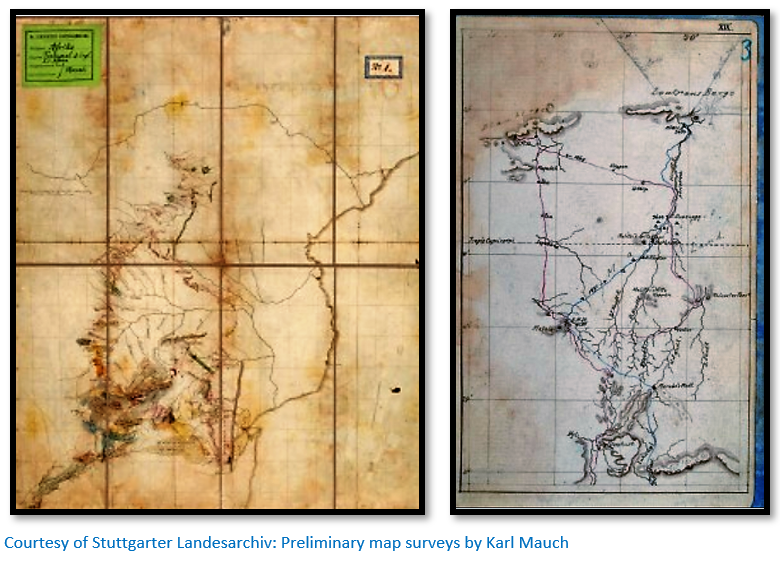

In June 1866 Mauch joined an exploratory expedition to the region between the Limpopo and Matlabas rivers on the Botswana border north of Pretoria. From this and his other data he put together a map of the Transvaal and sent it to a Cape Town printer for publication, but the project was not a commercial success; so he gave his information to Jeppe and Alexander Merensky. Their Transvaal map published in Petermann’s Mitteilungen in 1868 acknowledged the help from Mauch and the accompanying description notes that Mauch won a £5 prize for the best collection of minerals at the Potchefstroom show of that year and was elected an honorary member of the society's committee.

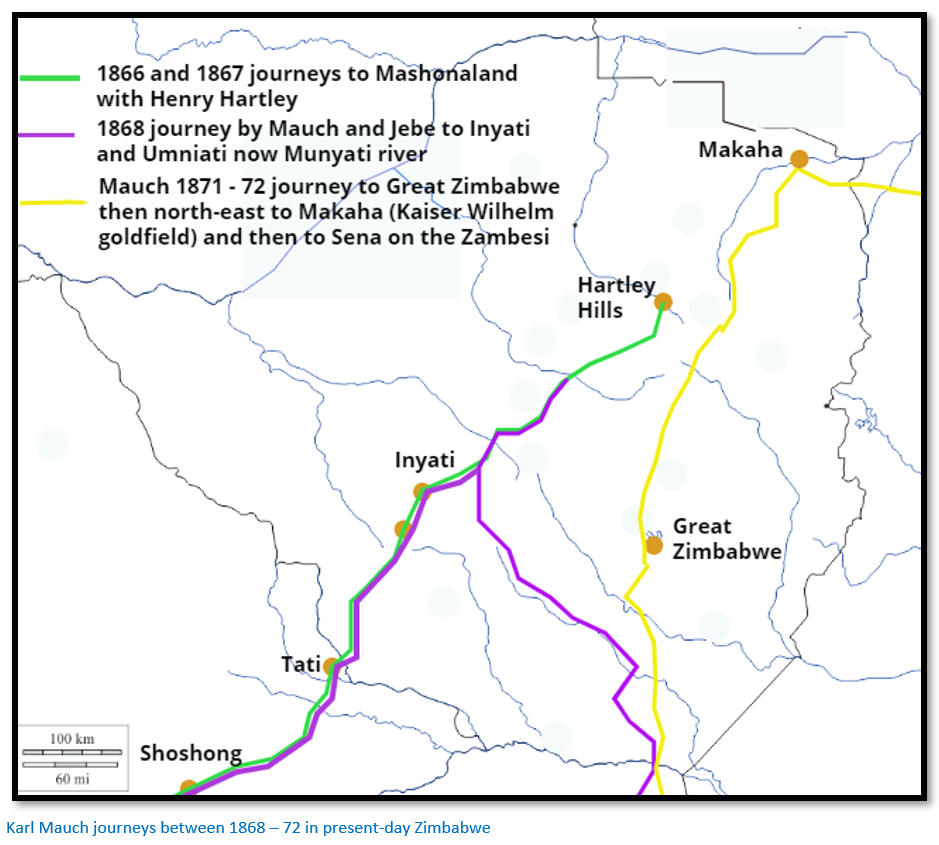

22 May 1866 – 10 January 1867 first Journey to Mashonaland with Henry Hartley

In February 1866 Mauch set out with the elephant hunter Henry Hartley on a hunting expedition through Botswana to Matabeleland in present-day Zimbabwe. From Hartley Mauch learnt much practical fieldcraft and the ways of dealing with native servants and overcoming the suspicions of Mzilikazi and the amaNdebele to collect information and mineral specimens of this largely unexplored region. Upon his return to Potchefstroom in January 1867 Mauch sent his observations by letter to Petermann saying: “Among my travel companions I must mention first the excellent and educated H. Hartley with his three splendid sons…My equipment for geographical observations was very poor and confined to a small, but good pocket compass; moreover it is dangerous to use scientific instruments in Mosilikatsi’s country or even to let them be seen. Even the sketching or collecting of minerals has to be done in secret, either during the absence of the Matabele who accompanied us or else during solitary excursions.”[ix]

Bernhard notes that Mauch’s map of his trip “is a neatly drawn valuable sheet of the whole region from the Vaal river to the Zambesi, scale 1:3,400,000 and shows beside his routes and discoveries, the distribution of the tsetse fly, mission stations and kraals, the height of mountains and the width of rivers and differentiates between permanent and periodical rivers.”[x]

15 March – 1 December 1867 second Journey to Mashonaland with Henry Hartley

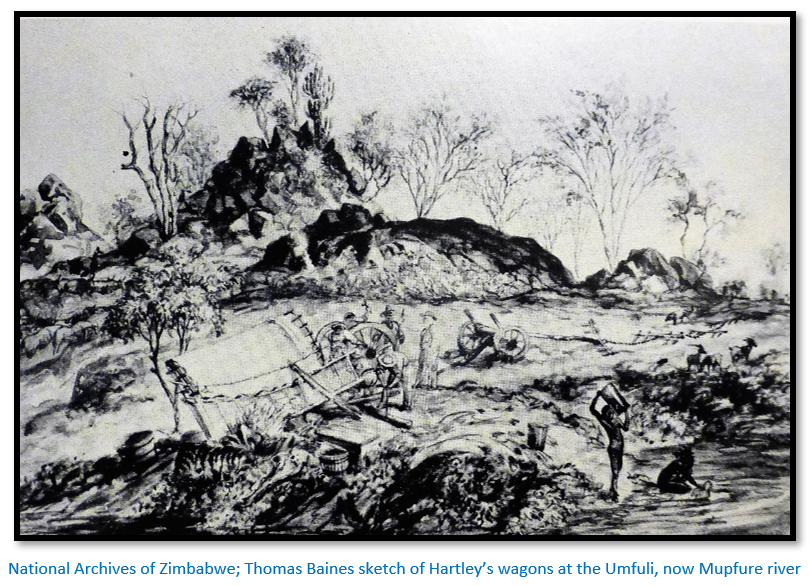

In March 1867 he again joined Hartley and other hunters on another expedition to Matabeleland, during which he confirmed the existence of gold deposits near the Umfuli, now Mupfure river (south-west of present Harare) which was called at the time the Northern Goldfields. On the return journey he collected rich quartz in gold bearing deposits on the banks of the Tati River, a tributary of the Shashe, near the current Botswana-Zimbabwe border.

Many authors have listed Mauch as the “discoverer” of these gold fields. However in all these goldfields the true discoveries were made by pre-European miners, probably VaKaranga in Matabeleland and Mashona in Mashonaland who left open pits where they had followed the quartz veins in search of gold. Both Hartley and Mauch were very much guided by the evidence of old unused workings in potential outcrops. Travellers were often offered small quantities of gold for barter; so they knew gold-mining had long been an activity carried out in the dry season by local people. Thomas Baines indicates that he was aware of this situation by painting “Oude Baas” Henry Hartley with a dead elephant on old workings near the Chimbo stream at Hartley Hills. Tabler states James Gifford travelling with the Hartley party showed Mauch the actual site portrayed in Baines’ painting from where he selected a 60 lb (27 kg) specimen of quartz which Gifford, Tom Hartley, Thomas Maloney and others carried 1.2 kms back to the Chimbo drift to load onto a wagon. At the same reef there was a smelter surrounded by rubble dumps and pits that yielded further excellent specimens and Mauch states he traced the reef for 35 kms (22 miles)[xi]

Mauch wrote: “on the 27 July Hartley brought me the news that when following a wounded elephant he passed several pits dug into quartz and that he suspected the former inhabitants of the country had dug for metal here, but what kind of metal he had been unable to discover…” After describing his journey to the spot: “On my approach this proved to be a quartz vein which protruded in places to a height of four feet. I soon came to this line and a few paces alongside it I came to a site which I recognised as a smelting place. This was about ten feet in diameter and contained slag, quartz stones, pieces of clay pipe, ash and coal. There were some pits four to five feet deep at a distance of about fifty paces, placed in openings of the quartz vein. Yet further on there was one pit ten feet deep but this was filled with water which probably prevented any further digging by the natives.”[xii]

“…I returned to this locality in the morning of 29 July, crossed the vein extending N 35 E° in a south-eastern direction and arrived after twenty minutes at a strong flowing small river [the Chimbo stream?] in whose sand I discovered fine, gold-like shining particles. After crossing the river I soon found the diggings which Hartley had described to me. These are irregularly placed, first here, then there. The quartz which appears to have been stored is turned upside-down and is thrown about. I found a largish depression close to the river which probably was used to separate the metal during the process of washing the gold. The pits are situated in an area two miles in length and 1.5 miles wide. A regular vein has been worked to a depth of six feet in the north-east part of this region, but it is again covered with so much earth that trees of seven inches thickness already grow on it…”

The amaNdebele guides believed Mauch was a crazy man because he was interested in nothing normal in their view and their fear and superstition gave Mauch much immunity from interference. Nevertheless he was still only able to smuggle out a few test specimens of quartz with indications of gold.[xiii] Mauch himself states: “As the Matabele had up til then heard nothing of the work of an explorer or naturalist, I, therefore could easily have been suspected of spying-out their country. It was expedient for me to trick the guides who had been attached to the party by the ruler Umselekatze; this succeeded so well that they pronounced me insane and I was therefore free, as it were to pick up stones and plants and then to throw them away again.”[xiv]

On 26 July he left their campsite on the Umbili [Manyama river?] and was at the Sterkstoom [Chimbo stream?] on the 28 July. Abandoned gold diggings were visited on the Umsweswe a few days later and between the 25 – 27 August they were at the confluence of the Sebakwe and Bembezana, a few kilometres north-east of present-day Kwekwe. By 10 September they were at Mzilikazi’s kraal at Mahlokohloko.

Mauch relates: “On the 3 August we passed ten minutes distance from this place. I remained behind and tried to explore other sites containing gold near the old Mashona-man Makombo’s kraal. After first looking around for his masters, the Matabele, and using partly the Zulu language (which I understood) and partly his own he points in an almost south-westerly direction, that is the direction of the extension of the quartz vein which I had first discovered [note the use of the word “I”; in fact, Hartley had discovered] and used the expression ‘kakulu’ (very much) mentioning also the names of the rivers Umsweswe, Sebakwe, Bembezana, Schwechwe.”

In order to examine the goldfields with Makombo who travelled with the wagons, the two would go ‘honey-hunting’ without their amaNdebele guides. Mauch says: “This was not denied me and I hurried to get my ‘horse’ into a better condition, in other words to sew a sole of untanned giraffe skin to my shoes.”[xv] The two of them managed to explore parts of all the above rivers. On the 25 August; “it was late in the afternoon that when we reached the junction of the Bembezana and the Sebakwe (Mauch calls the Pembesi and Sepakwe) To the north of the latter we wandered in the goldfield over quartz and schist and so it continued until we were forced at the setting of the sun to spend the night among the most beautiful geological formations…Taking only a few easily collected quartz samples with me, I refused to follow old Makombo to a place that far away was supposed to be rich in darama (gold)”[xvi]

Thomas Leask writes in his diary on 17 Aug 1870:[xvii] “Mauch who went out yesterday on a sort of exploring expedition, came upon five lions which got up in front of him. He wanted to get to a particular hill; the lions were between him and it and as they did not seem inclined to retreat to any distance, he merely waited until they moved a little, when he turned and mounted the first tree. He slept none that night but rested in a mopani tree.” [See the article Thomas Leask (1839 – 1912) and his first two hunting trips into Matabeleland and Mashonaland in 1866 and 1867 under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com ]

After leaving Mahlokohloko Mauch writes: “On the 20 September we arrived at Mosilikatsi’s last subjects at the southern guard post of his property under the command of the chief Manjami. [Manyami] The passport office is here for all those arriving from the south. From here the name of each traveller as well as his purpose is reported to headquarters by runner and here too, the answer has to be awaited.” [This is at Makobi’s kraal; see the article The Hunter’s Road – followed on maps under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

The goldfield on the Tati

Mauch writes: “…doubtful as to whether I would be able to repay my debts and how this could be done, contemplating in what way I could earn my daily bread in future…I was happily torn out of all this by the sight of an immense quartz vein between greenish schist which rose more than six feet above the ground. Hallo, I cried, here must be the reward for my efforts, I shall have to come here to dig for gold! And this decision I actively took then and there. Having made fairly accurate acquaintance with goldfields to the north of Moselekatze I certainly suspected gold and I was not disappointed. Over a width of twenty miles occurs various fine schists of grey, snowy-white and greenish colour, interspersed with smaller or larger quartz veins. I satisfied myself by taking some few gold bearing samples of quartz. I take this region as being still richer in this precious metal than the already mentioned ones. Had I not had to battle against the chief faults of the younger generation of Afrikaners of Boer extraction; laziness, ignorance and even perfidy, I would certainly have obtained up to three pounds within fourteen days by simply crushing the quartz stones with a hammer.”[xviii]

From Hartley’s farm at Thorndale Mauch hurried to Pretoria and wrote a letter to the Transvaal Argus on 3 December 1867 describing his finds and stating that he had traced the reef at Tati for 128 kms (80 miles) and on the Northern Goldfields reef for 35 kms (22 miles) but he did not include his own belief that the gold could probably not be worked for a profit due to the transport costs and opposition from the amaNdebele! The Transvaal government were interested even if the farmer citizens were not and the British newspapers in the Transvaal and Natal caught gold fever at once. South Africa was in the midst of a financial depression caused by the Basuto wars and to the newspaper editors this seemed a good way to lift everyone’s spirits.

Once again Mauch claimed all the credit for the discovery and Burrett writes: “It was his effective marginalising of Hartley and his portrayal of the discovery as an accident dependent upon his own geological skills that subsequently soured relations between Mauch and the Hartley family.”

Mauch travelled to Natal where he was entertained by Lieutenant-Governor Robert Keate and officials and described his finds. The ore samples he brought with him assayed well in Natal and later in England which added to the public excitement. Many speculative gold-mining companies were formed in 1867-8 but most failed before their expeditions set out. However in general the discovery of diamonds at the Vaal river and now gold in the interior gave South Africa a much greater value to the Great Powers.[xix] Many in Natal hoped that as Durban provided the most accessible route to the goldfields they would profit from any gold rush.

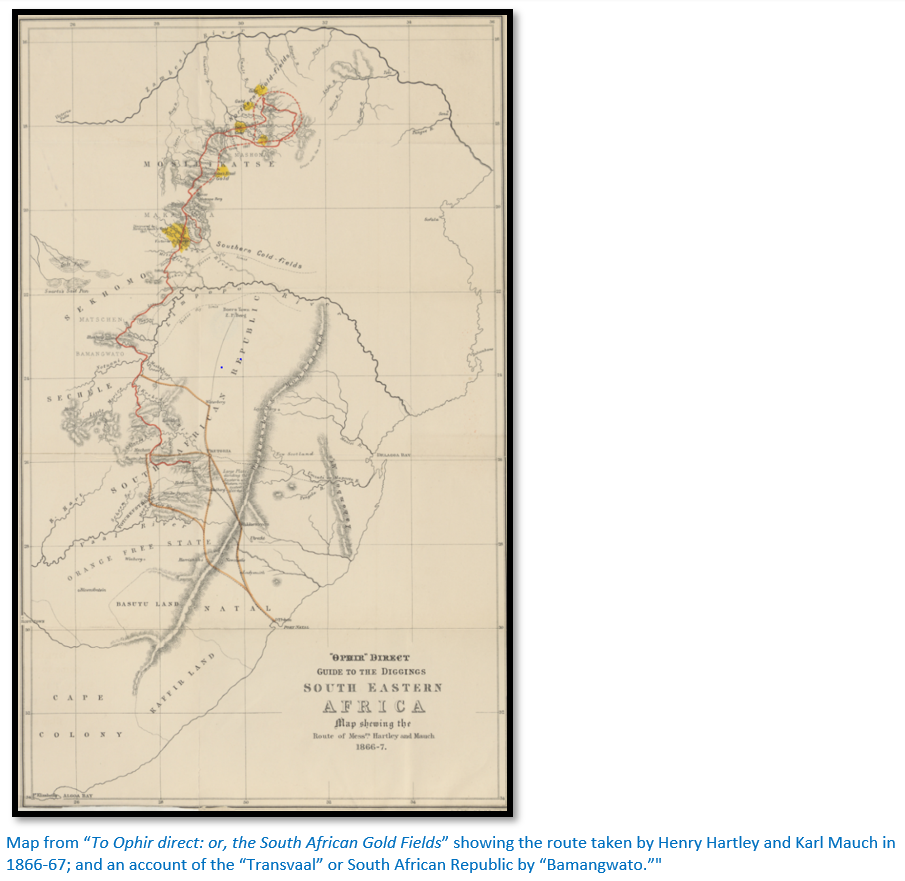

A number of pamphlets and guidebooks were written and they hyped the story that the goldfields were even richer than those in Australia and California. Richard Babbs wrote The Gold-Fields of South Africa and the Way to Reach Them and it is believed that a hotel-keeper, Albert Broderick, writing under the pseudonym ‘Bamangwato’ wrote To Ophir Direct; or the South African Gold Fields with a map showing the Route Taken by Hartley and Mauch in 1866-67.

In Durban Mauch bought survey instruments with money provided by Petermann, testing them at the observatory in Pietermaritzburg and staying with Major Erskine, the Colonial Secretary; and by March 1868 he was back in Potchefstroom.

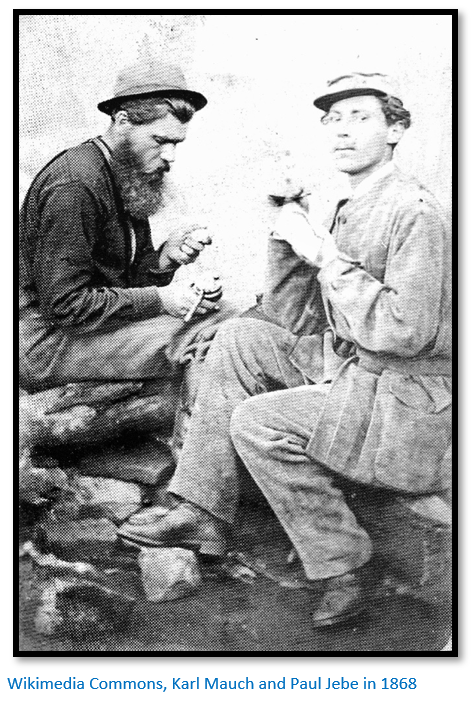

8 May – 18 October 1868 Journey to Inyati mission in Matabeleland

On 8 May 1868 Mauch left on a planned exploratory journey through central Africa via the Portuguese trading station at Zumbo on the Zambesi river; but was forced to turn east from Nylstroom on account of an ongoing native war before journeying through Botsabelo near Middelburg to Lydenburg where the missionaries Rev Alexander Merensky and Rev Nachtigal of the Berlin Missionary Society did all they could to assist him. Merensky wrote a vivid sketch of Mauch; "I can still see Mauch as he once sought rest and refreshment at the Botsabelo Mission Station after a toilsome journey. His sturdy figure was clothed in leather; revolver, compass, sextant, hunting-knife and a tin bowl hung from his belt; in his hand was a double-barrelled gun, while its cover and the indispensable blanket were slung on his back."[xx] He was accompanied by a German engineer, Paul Jebe, and for a week or so by V. Erskine, the Natal Colonial Secretary’s son.[xxi]

Mauch sent most of their supplies to Inyati by prospector’s wagon and he and Paul Jebe with a donkey, pack ox and five porters[xxii] travelled north-east through the Transvaal, noting the presence of copper mineralisation at Loolekop near Phalaborwa before crossing the Limpopo above the Bubye river confluence. They travelled up the Bubye before moving on to the Nuanetsi and following it upstream to the headwaters before striking out north-west towards Matabeleland. This was during a period of severe drought and they were finding starvation amongst the people and were themselves reduced to eating skins and wild plants, some of which made them ill.[xxiii]

“The few natives had suffered such a dearth in their harvest that they nourished themselves with unripe tree-fruit, with the white, acid-tasting flour that envelopes the seeds inside the pods of the baobab, with the extraordinary bitter fruits of the Kigelia, with onion-like roots, with grass roots, and sometimes even with the carrion of animals that had been killed by lions. In these days of famine I considered a small piece of indigestible buffalo skin, as well as some small fishes which I found in shallow pools and boiled without salt, exquisite delicacies.”[xxiv]

A month after leaving the Limpopo river Mauch and Jebe reached the first amaNdebele kraals in October having endured much suffering from hunger and fever. Here they were arrested for coming into Matabeleland by an unauthorised route (i.e. not via the Tati settlement) and were suspected of being Boer spies. However Mncumbatha, the amaNdebele regent during the interregnum between Mzilikazi’s death and Lobengula’s succession, released them on 18 October 1868 and they eventually reached the London Missionary Society mission at Inyati, now Inyathi, north of Bulawayo. After waiting through the summer rains and convalescing in January 1869 they travelled along the Hunter’s Road finding indications of a gold field along the Umniati River, now Munyati, a tributary of the Zambezi. However they soon returned to Potchefstroom, partly because Mauch’s friends, through "inexcusable neglect" had not forwarded supplies,[xxv] but also because of the amaNdebele rumours that he was exploring for gold.

About 25 March 1869 Mauch was at the Umpakwe river going towards the Tati settlement with two hunters where he met Bottomley, M’Intosh, Duncan and Guthrie going into Matabeleland and told them the best potential sites for gold prospecting. By 19 May he was near Potchefstroom where he met Eduard Mohr and Adolf Hübner.

The report in Petermann’s Mitteilungen was particularly negative. “From Lydenburg Mauch continued his trip to the north crossing the Limpopo and then turned north-west towards Mozilikazi’s empire, which he was finally able to reach although suffering the greatest hardships and danger. His European companion [Paul Jebe] who went with him turned out to be unsuitable for such journeys; the five natives whom he had taken with him too caused him many worries, his valuable dog died in the lowveld of the Limpopo from lack of meat or simply from lack of any food. He had to shoot his pack-ox right at the beginning of his trop from Lydenburg and eat it as it had already been attacked by tsetse-fly. North of the Limpopo the female donkey got mixed up with a troop of quaggas from which it was impossible to extract her. The whole journey was for months a continual fight against hunger as drought and famine existed along almost the entire route…”[xxvi]

Paul Jebe soon after became a victim of fever. Thomas Leask records in his diary for 21 June 1870: “George and Swithin Wood arrive at their camp on the Ngezi river. Both are still weak from fever. They were the first party into Mashonaland in 1870; George’s wife, child, mother-in-law and Paul Jebe died from fever although they all stayed on high ground. This year has given us all a lesson which will not soon be forgotten.” [See the article Thomas Leask (1839 – 1912) and “my last hunt” to Hartley Hills in 1870 under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Mauch’s discoveries of gold attracted worldwide publicity

The following is from A. W. Rogers: “According to Friedrich Jeppe, Mauch was extremely averse to being thought of as a prospector and kept many discoveries to himself in consequence. In a letter to Jeppe Mauch attributed the discovery of the gold-field on the Umfuli and Umsweswe rivers to Henry Hartley, but Jeppe who published the letter in the Transvaal Argus said that Mauch was too modest and that the discoveries were his. Hartley himself is believed to have been the author[xxvii] of a book ‘Direct to Ophir’ published in London in 1868 under the pseudonym ‘Bamangwato’ in which Mauch is credited with the discovery of gold in the north.

W.H. Penning (‘A Guide to the Goldfields of South Africa’ Pretoria, 1883) says that in 1868 rumours reached England of Mauch's discoveries north of the Transvaal, as well as in Lydenburg and near Marabastadt at Pretoria. C.F. Osborne, H.T. Glynn and Thomas Baines all bear witness to the importance of Mauch's finds of gold in attracting the attention of prospectors, miners and the general public of America and Europe to the probability of there being payable goldfields in southern Africa.

Friedrich Jeppe (Journal of the Royal Geographical Society; 47, 1877) thought that Mauch's discovery at Tati was “the commencement of the golden era that dawned upon South-eastern Africa." Although it seems certain that Mauch's work started the modern period of gold-seeking in South Africa, he was not the first European to find gold in the Transvaal. According to Dr G.G. Preller in "Argonauts of the Rand" published in 1935 J.G. Bronkhorst in 1836 saw gold which had been obtained by people in the Zoutpansberg and P.J. Marais, who was born in 1826 and educated at the South African College School found gold in the Okaikei and Crocodile valleys in 1853. Marais had been in California and Australia before he came to the Transvaal. Dr Preller also relates that the Rev. Tobias Mare found gold on Wilgespruit and Braamfontein in 1876 but that Mauch had said in 1867 that there was gold in the Rand and diamonds near Pretoria. There is, however, no evidence in Mauch's published writings…”

1869-70 Journey by foot to Delagoa Bay

Back in Potchefstroom by 15 May 1869 Mauch spent a few weeks familiarising himself with the diamond discoveries on the Vaal river and visiting the camps at Dutoitpan, Bultfontein, Alexanderfontein, De Beer and Colesbergkop; he looked for diamonds but failed to find them along the Harts River. “I am not a professional diamond digger and did not intend to become one. As fortune did not smile on me, I turned my back on the region…”[xxviii] Then he accompanied a Portuguese delegation and Lieutenant Leal to Mozambique looking for the best route to Delagoa Bay (now Maputo Bay) They reached Lourenco Marques, now Maputo in August 1870 after a difficult journey through Swaziland, during which time he collected more geographical information for a map, but a severe attack of fever prevented further exploration in Mozambique and forced him to return to Potchefstroom.

Typically, no mention is made of his travel companions and the Portuguese are described in very disapproving terms. He collapsed from fever and only the good care of the Berlin Missionaries at Lydenburg saved his life.

1870-71 mapping in the Transvaal

After recuperating in Lydenburg he was back in Potchefstroom by October 1870 and visited and described the coal deposits near present Vereeniging. He decided to try his luck on the diamond fields once more and sailed down the Vaal River in a small, flat-bottomed boat 10 x 4 ft (3 x 1.2 metre) doing the 350 miles in 23 days using a big umbrella as a sail and mapping the river more accurately. He suggested that the removal of some obstacles [33 of them islands and masses of boulders, cataracts and rapids!] and the cutting of a few canals round the rapids would make the Vaal river navigable from the Transvaal. Again he was unsuccessful at the diamond diggings but came to the conclusion that the diamond-bearing ground was much more extensive than was generally believed and would be a commercial success. He returned to Potchefstroom on foot in January 1871.

An account of this journey, "Wasserfahrt von Potchefstroom nach den Diamantfeldern am Vaal-Fluss, December 1870 - January 1871", was published in Petermann’s Mitteilungen later that year. Soon after his return to Potchefstroom in February 1871 he completed a map of the Delagoa Bay region which was published by Forssman in 1874.

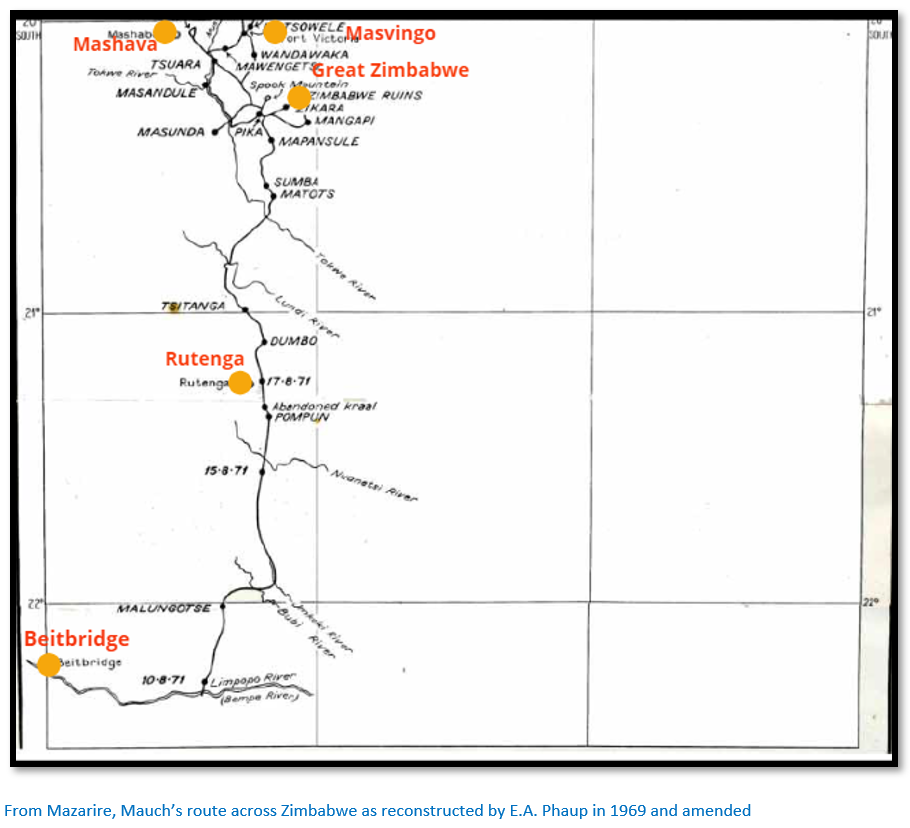

1871-72 Journey to Great Zimbabwe

At the Berlin Missionary Society station of Botsabelo Mauch heard from the missionaries Alexander Merensky and Albert Nachtigal of rumours from local people of great ruins north of the Limpopo in Banyailand which they had tried and failed to reach in 1862 after their porters were infected by smallpox and refused to go further.[xxix] Local people told them the ruins were haunted and approaching them was hazardous because of the local tribes. Rev Merensky agreed to accompany Mauch and they made plans together at Botsabelo, but the missionary was forced to cancel when an outlying mission station was attacked.

As part of his preparations Mauch says: “I had to consider it far more practical to travel with one suit only probably for several years. Durability is the foremost reason and therefore I clad myself with the exception of underwear in leather. Coat, vest and trousers were suitable made of tanned, softly treated buckskin and supplied with roomy pocket each of which had to hold its particular object…I chose the thickest flannel I could find for my underwear. This costume was certainly well-wearing, but with the proverbial African heat, its weight was almost insupportable. By and by one gets accustomed to it…An umbrella of such dimension that a small family could find protection beneath it guards against sunshine, rain or dew during the night. A woollen or fur-blanket (kaross) serves as a further cover during the night. ”[xxx]

“I altered the watertight etui of a gun container into a kind of school satchel to hold my books amongst which however no ‘light literature’ could be found. It contained besides the books that were needed several times a day, an almanac, logarithms, a book on botany, geological science, also drawing instruments, colouring box, journals, drawing books, inkpot and a towel with comb and hair brush.”

Merensky was an enthusiastic believer of the myth that: “in the country northeast and east of Moselekatze (i.e. Mashonaland) the ancient Ophir of Solomon is to be found.” Merensky has already inspired H.M. Walmsley to write a mad fictional account called The ruined cities of Zululand. This enthusiasm ribbed off on Mauch who was similarly inspired to seek: “the most valuable and important and hitherto most mysterious part of Africa…the old Monomotapa or Ophir.”[xxxi]

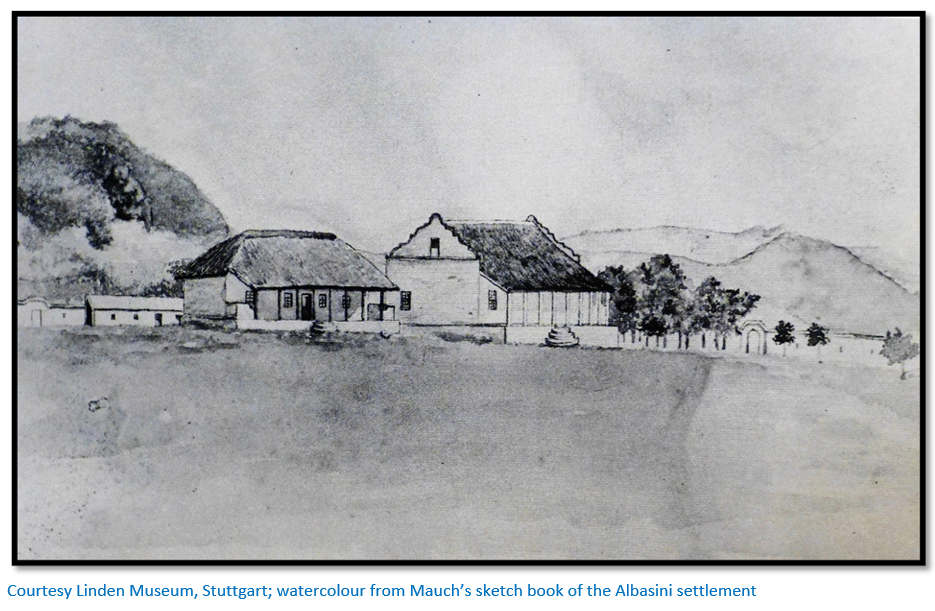

In the winter of 1871 Mauch went off alone to the Zoutpansberg using the trading post of João Albasini a Portuguese trader, ivory hunter and slaver as a base.[xxxii] From here he collected five young people who had been snatched from their homes north of the Limpopo with the excuse of returning them to their families. In this he succeeded, but he met increasing opposition from local people and disagreements and desertions from his porters as he penetrated the interior; north of the Nuanetsi river a local chief named Shumba robbed him, held him prisoner and tried to poison him. “It was about 9 o’clock when two black figures approached and set a large calabash with beer before me, trying to make me understand that this was a present for me from the chief. I asked them to have a drink first, as it is done everywhere, but they refused, an only too clear sign that the beer contained poison. I smashed the vessel with one single kick and an unmistakeable move with the rifle persuaded the messengers to retreat hastily.”[xxxiii]

He was rescued by several of Chief Mapensula’s men and they travelled northwards and crossed the Lundi, now Runde river and reached the kraal of Mapensula, [Mauch writes Manpansule] a Shona chief living on a tributary of the Tokwe river about 32 kms (20 miles) south of Great Zimbabwe.[xxxiv]

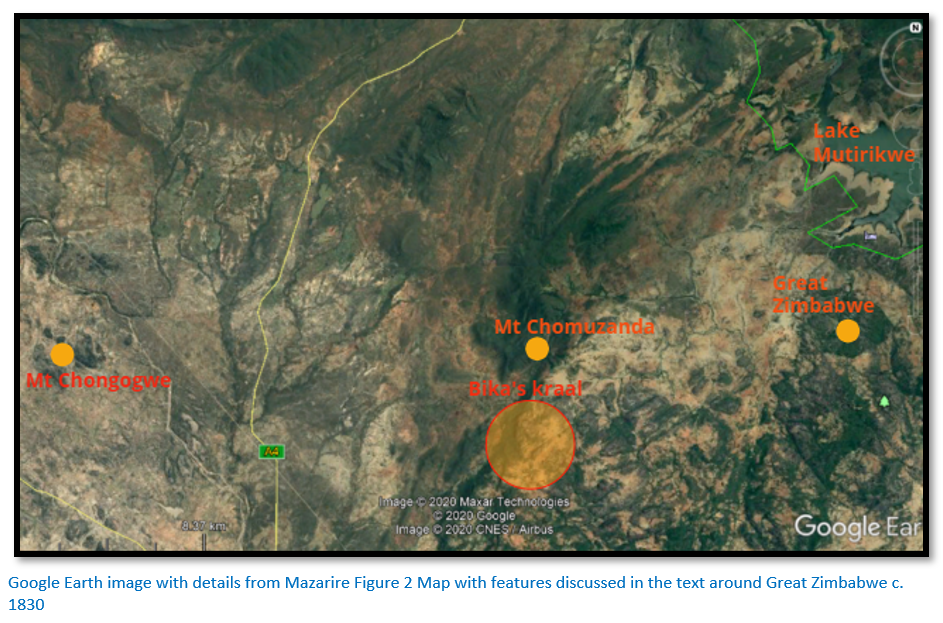

Mauch had heard and been warned of a certain Adam Renders (sometimes spelt Render) a hunter and ‘dangerous outlaw’ who had abandoned his wife and four children in the Transvaal and had lived with the daughter of a local chief. Renders answered Mauch's written request for help by collecting him and taking him to Bika's kraal, just 20 kms (12 miles) from Great Zimbabwe on 31 August.[xxxv]

Mauch wrote to Petermann and the missionary Gruetzner from Pike’s [Bika] kraal on 12 / 13 September 1871 saying: “On 30 July I started from Albasini; during a four days stay at Sewaas, my goods already diminished through time and men were further robbed and reduced in a friendly fashion, on the 18 August the restoration of five kidnapped children to their parents at Dumbo’s, on the 25 August an attempt by Mapensula, a Makalaka chief – instigated by a band of robbers sent by Sewaas – to keep me at his kraal on a high kopje as ‘his white man’ on the 31 deliverance from this terrible situation by Adam Render, on the 5 September discovery of goldfields No 1 of 1871, on the 5 September discovery of the large ruins of Zimbabye (in Portuguese Symbaoe) on the 11 September I obtained first, permission to closely investigate the nature of the ruins, secondly, the information that others exist about three days distance towards north-west of here where according to the description, an obelisk can be seen…”[continues below]

Although Mauch stayed at Bika’s kraal with Adam Renders for about nine months, there was great resistance by the local inhabitants to his visiting Great Zimbabwe. Bika (Mauch calls Pika) was a village headman under Chief Charumbira who resided near the Bondolfi Mission on the western foot of Chigaramboni Mountain. Mauch stayed with Bika’s son and successor Madzivere.[xxxvi]

“I learned a wonderfully fabulous story of a pot that hid itself in clefts and bushes on a mountain and at times was changing its position on its own; furthermore some more spook and ghost stories. I just had to visit the mountain with its miraculous pot, but only with great trouble and the art of conviction did I succeed in finding some companions among the sons of his [Renders] father-in-law, Pika. The mountain was ascended on the 3 September. It is in a straight line, about one hour away, of fair height, with a bare summit from which one has a marvellous comprehensive view. Only gradually did my companions dare to climb the peak and one of them, who had lost his toes by fire, suddenly pointed in an easterly direction to a hill about two and a half hours away and averred that there were largish walls that had been built by whites.” [xxxvii]

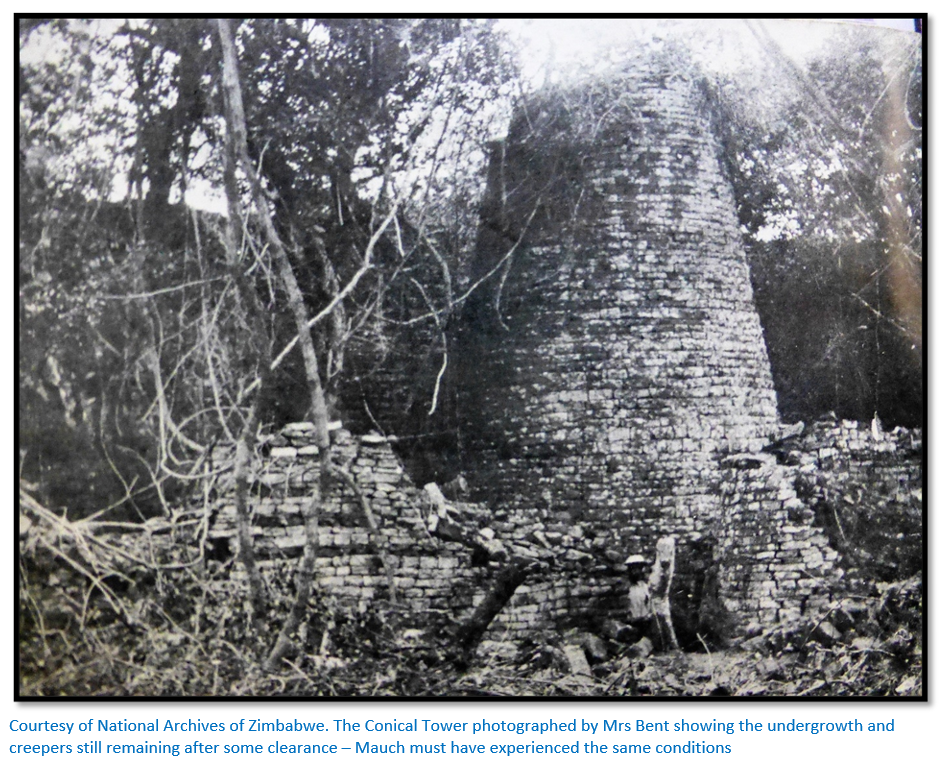

Both Mauch and Renders were destitute and sick with fever, but in October they heard of a European hunting at the Runde / Ngesi confluence [about 80 kms south west of Great Zimbabwe near Mt Buchwa] The hunter was George Phillips[xxxviii] who was a resident trader at Gubulawayo for many years and Mauch sent a letter requesting supplies. Phillips joined Mauch and Renders at Bika’s kraal and they visited Great Zimbabwe together on 11 September 1871 although Phillips was not that impressed, probably because the full extent of the structure was covered in trees and vines and not accessible.[xxxix]

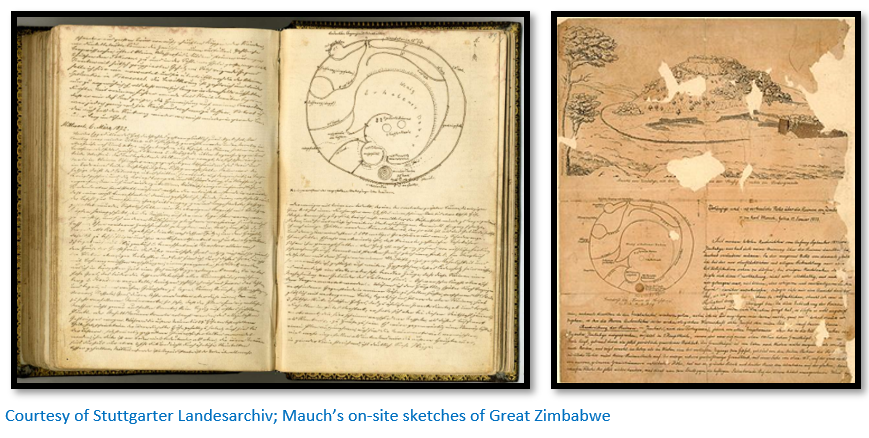

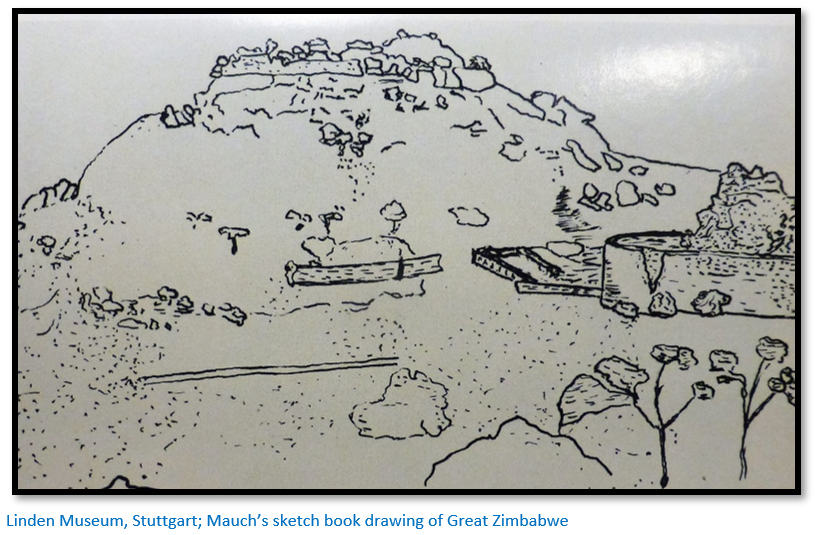

Phillips left what supplies he could spare for Mauch and Renders and departed for Matabeleland. In all Mauch visited the ruins three times and was the first to describe and sketch them. These were sent in a letter with a description of the ruins to Rev Merensky at Botsabelo Mission to be forwarded for publication in Petermann’s Geographischen Mitteilungen in 1872.

Phillips and Mauch already knew each other as recorded by Leask in his diary of ‘My Second Hunt’ from 4 May – 15 December 1866 into Matabeleland and Mashonaland. He notes on 28 July: “Phillips and Mauch, a German geologist who is travelling with Hartley went over to Umgesi [Ngezi river]; they were not out with me. Their dogs chased a water-buck which jumped into the river. The poor animal got about half-way across when he was seized by a crocodile which tried to drag it under water. The dogs jumped in after the buck and seized him. So there they were, the crocodiles – they saw more than one - pulling in one direction, and the dogs in another. Buck, dogs and all were pulled under three times. Phil says a crocodile had got hold of one of the dogs. The spectators of this scene succeeded in frightening the crocodiles and the dogs brought the buck to the bank, the latter dead, the former all but.”[xl] [See the article Thomas Leask (1839 – 1912) and his first two hunting trips into Matabeleland and Mashonaland in 1866 and 1867 under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com ]

First Europeans to visit Great Zimbabwe

There is no evidence that the Portuguese ever visited Great Zimbabwe; their reports provide the earliest written accounts of the interior although they rarely extend beyond the Mutapa empire in northern Mashonaland and they do refer to stone buildings; Diogo de Alcacova wrote that in ‘Zunbanhy’ the capital, “the houses of the king…were of stone and clay very large and on one level.” Antonio Fernandes gave an account of places he personally visited saying: “Embire…a fortress of the king of Menomotapa is now made of stone…without mortar.” Joao de Barros left a long description of gold mines and “a square fortress, masonry within and without, built of stones of marvellous size and there appears to be no mortar joining them…The natives of the country call these edifices Symbaoe…” This may indeed be a description of Great Zimbabwe but its description was provided not by the Portuguese themselves, but probably by Swahili traders at Sofala.

Boer hunting parties had visited the area of ‘Banyailand’ north of the Limpopo river in the 1860’s to hunt, but it is not clear how far they went[xli] and they certainly left no record of having seen Great Zimbabwe.

George Arthur Phillips was a hunter, trader and for many years business partner of George Westbeech. He came to Natal from England in 1862 and first visited Matabeleland in 1864. In 1866-7 he travelled to the south-east crossing the Ngezi, Runde and Tokwe rivers and hunted elephant in the area of present-day Masvingo although he failed to visit Great Zimbabwe[xlii] perhaps because his guides wished to avoid a confrontation with local people. Phillips only left Matabeleland in 1890 after twenty-five years of almost continuous residence and was nicknamed ‘Big’ or ‘Elephant’ by his friends who included both Mzilikazi and Lobengula.

Jan Adam Renders was a German who arrived in South Africa from America in 1842. He became a Transvaal burger and hunted every winter in the south-central region of Zimbabwe (referred to as Banyailand at the time) He was taken to Great Zimbabwe in 1867, returning in 1868 when he abandoned his family in the Transvaal and lived with the daughter of Bika, a petty chief and had local children. Known locally as ‘Sadama’ he was living at Bika’s kraal[xliii] when he rescued Karl Mauch and brought him to safety on 31 August 1871. Renders was fluent in the local Chikaranga language and interpreted for Mauch. Tabler states what finally became of Renders, the first European to visit Great Zimbabwe is unknown[xliv] although according to Mazarire[xlv] his son Hendrick told Mrs Jean Boggie that he left a deathbed note to his wife before he died about 1881.[xlvi] Most of the local information on Renders was collected by Richard hall in 1902 from a local chief ‘Mogoma’ as Renders stayed in his kraal and they went elephant hunting together.[xlvii] Attached as an appendix is the verbatim account written by his son Hendrik Jacobus Renders from the website geni.com.

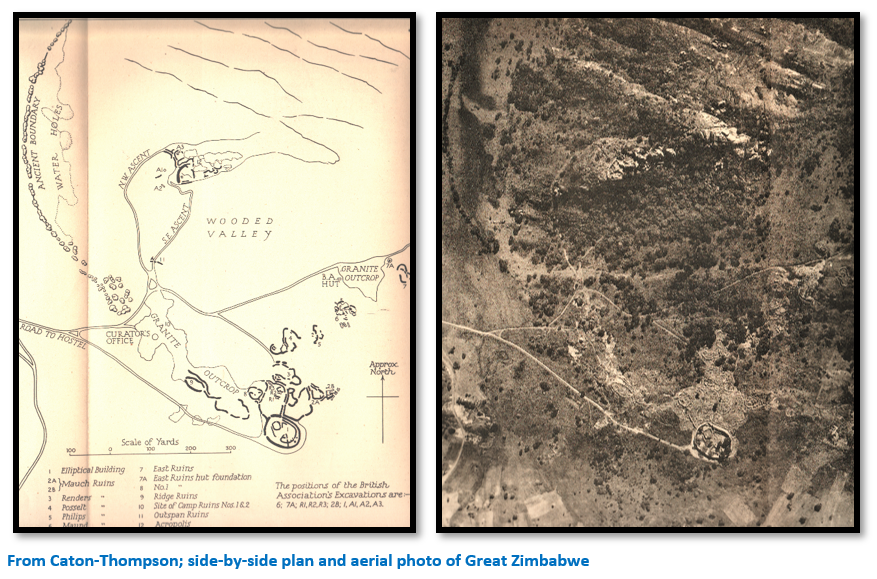

Gertrude Caton-Thompson led the 1928 British Academy inspired excavation at Great Zimbabwe with the photographer, later noted archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon. The quality of Caton-Thompson’s archaeological work far exceeded anything done prior to this date. In her book The Zimbabwe Culture she states categorically that Renders was the discoverer. P11: “The names commemorate the earlier explorers of [Great] Zimbabwe, beginning with Adam Renders who ‘discovered’ it in 1868 and Karl Mauch who three years later, gave to the world fuller details concerning it” and P272: “It was in 1868 that [Great] Zimbabwe was discovered by Adam Renders followed by Karl Mauch in 1871 and from this period onwards the country was steadily explored and exploited in all directions by hunters and prospectors.”

F.O. Bernhard who translated Mauch’s Journals states: “It is a debateable question whether he, in fact, was the discoverer of these ruins, whose whereabouts were vaguely known from reports by various black hunters. Adam Render had lived nearby for some year’s previous to Mauch’s arrival and must have been aware of them.”[xlviii]

Gerald Mazarire writes that although Mauch was not the first European to visit the Great Zimbabwe area he was the only one to provide a useful and detailed record of the VaKaranga in his Journals. The period between 1750-1850 coincides with the great movement of peoples in the region during the Mfecane and specifically with the disintegration of the Rozvi empire and his paper “offers a re-interpretation of Mauch’s record of African society and politics in the communities around Great Zimbabwe”[xlix]

Mauch’s theories on the origins of Great Zimbabwe

Mauch’s prejudices negatively influenced his theories about Great Zimbabwe. From his observations of the people living at the site at the time he did not believe they were capable of building the structure.[l] In his Journals he noted that they had only lived in the area for about forty years and he was told: “of the presence of quite large ruins which could never have been built by blacks.”[li] His later Journals are filled with sketches of artefacts he saw at Great Zimbabwe – they are all clearly African and local in origin, yet Mauch refused to acknowledge this fact.

Instead he tried to link Great Zimbabwe to Ophir, a wealthy trading port cited in the Bible and the ruins to Ophir’s legendary ruler, the Queen of Sheba, who visited King Solomon at Jerusalem bringing him a huge quantity of gold, spices and exotic animals. Mauch based some of his theory on wood beams which he incorrectly decided were cedar wood, an important export from Lebanon and concluded they had been brought by Phoenician traders exploiting the region’s gold deposits and that Great Zimbabwe was an imitation of Solomon’s palace at Jerusalem. His image of Africa was strongly negative which made it easy for him to identify the ruins of Great Zimbabwe with ancient Ophir.[lii] Mazarire also points out that finding the lost lands of Prester John had proved elusive in the Far East and increased attention was thus paid to Africa.[liii]

Neither Mauch nor Merensky of course were the first to make the link with ancient kingdoms. Sofala whose fort was established by the Portuguese in 1505 was considered by Thomé Lopes to be the biblical Ophir; its ancient rulers connected with the Queen of Sheba. João de Barros in his 1552 Da Asia wrote in connection with the buildings called Symbaoe: “and as these edifices are very similar to some which are found in the land of Prester John, at a place called Acaxumo, which was a principal city of the Queen of Sheba.” These and many other contemporary quotes show that Mauch’s theories on their origin were not at all unique.[liv]

Over time however, Mauch began to doubt his own Ophir Zimbabwe theory although this and similar speculative theories were widely held until and even after 1905, when Dr D.R. MacIver through archaeological excavation proved the ruins to be of African origin.

A further description of Great Zimbabwe appeared in 1876 a year after Mauch’s death in the Transactions of the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnography and Prehistory P186-9 in which Mauch states he had changed his opinion about the origin of the buildings, but true to his usual manner he does not say how or why his opinions have changed.[lv] “Since my last news from Zimbabye at the beginning of September 1871, my views on the ruins there have had to be changed considerably. In my meagre note at the time I believed, because of the superficial and quick observation of them, to recognize only a fortification. After contemplating the case my opinion proved to be erroneous and after I had the chance to open conversations about them with more senior and therefore more detached and more understanding people, an explanation forced itself on me which however, I dare not make public, although I am convinced of its correctness.”

Modern theories on the origin of Great Zimbabwe

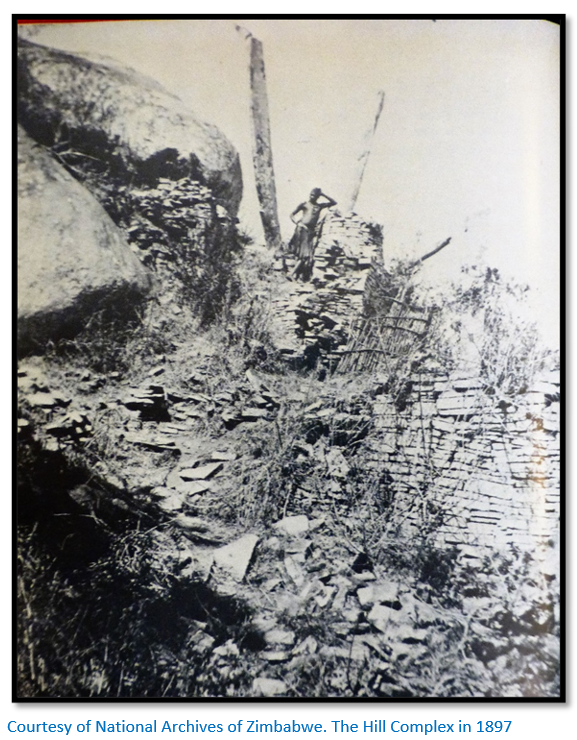

Both Caton-Thompson in 1929 and Garlake in 1973 came to the same conclusion following detailed and scientific excavations and review of their findings that all the man-made structures at Great Zimbabwe were of African origin with initial settlement in the fifth century evidenced by iron tools and pottery and with additions to the buildings through to the twelfth century and continuous occupation from then to the fifteenth century. The bulk of the dateable excavated finds are from the fifteenth century. Excavations in 1971 on a midden on the southern slope of the Hill Complex revealed the remains of over thirteen hundred cattle which along with pottery, iron-work, oral traditions and anthropology overwhelmingly indicate the builders were the ancestors of modern Mashona people.

Great Zimbabwe

The Great Zimbabwe area covers 1,780 acres and comprises three distinct areas; the Hill Complex also called the Acropolis, the Great Enclosure and the Valley Complex. The Hill Complex may be the oldest dating from the fifth Century. The Great Enclosure was called "the house of the great woman" or "the great house" by the VaKaranga people who lived there during the nineteenth century and was built at the height of Great Zimbabwe's power from the twelfth to fifteenth centuries. The walls of the Valley Complex appear to be the youngest suggesting they were built as the population expanded and Great Zimbabwe needed more housing space.

Mauch’s visit to Great Zimbabwe

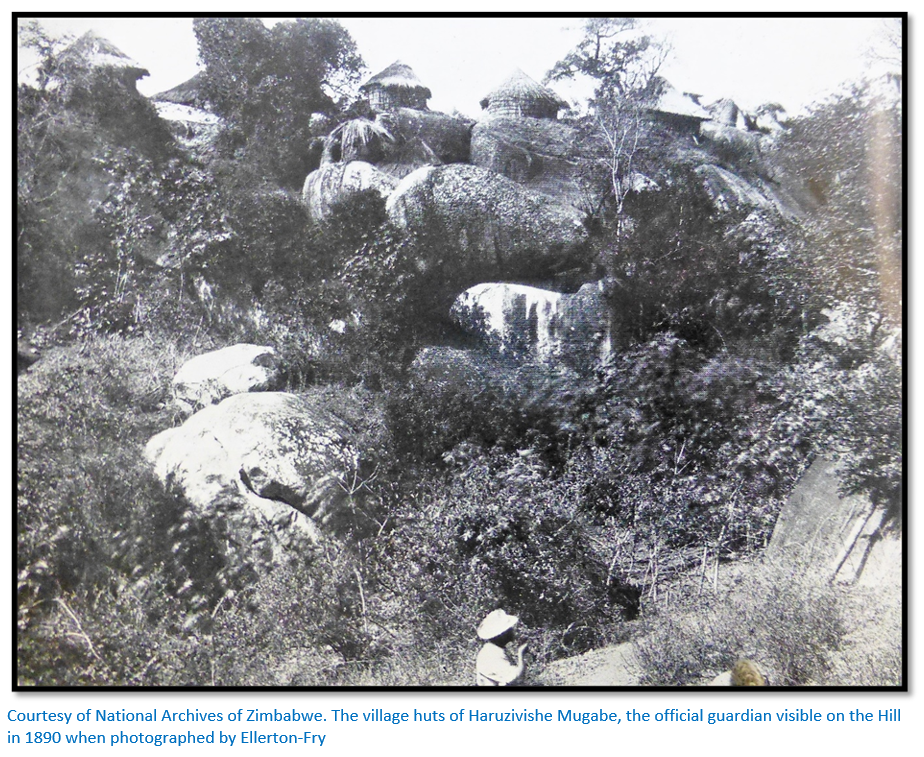

Initially Mauch, Renders and Phillips climbed a nearby mountain called Chomuzanda which local people were reluctant to climb because they believed it was haunted and which Mauch refers to in his Journals as ‘Spook mountain.’ Having persuaded his guides to climb on 3 September, Mauch was shown in which the direction Great Zimbabwe lay from the summit and that it was two and a half hours walk away but was unable to find a guide to take him despite making a of approaches to local people. Finally he learnt that Great Zimbabwe fell under the authority of the VaKaranga chief Chipfunhu Mugabe and paid a visit to his kraal near the Mzero river on 5 September 1871. Mauch, Renders and Phillips were only granted access to Great Zimbabwe on 11 September 1871 after having paid homage and presenting the chief with suitable presents.

Mauch’s Journal

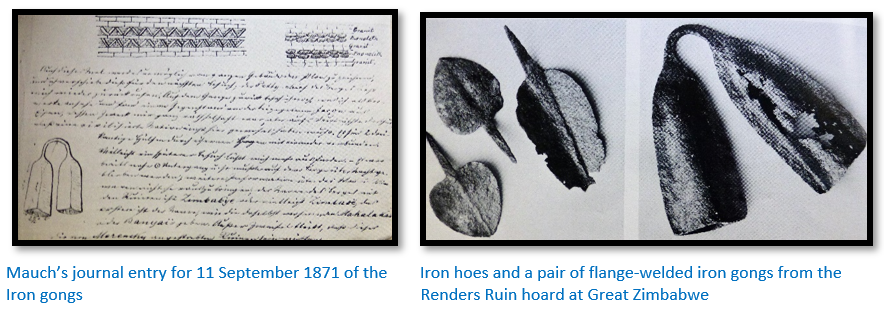

Garlake writes that despite only being allowed three short visits to Great Zimbabwe “Mauch’s descriptions, plans and sketches, put down in his diaries, then in letters and finally in two papers published in Germany were, given his circumstances, surprisingly exact, full and detailed.”[lvi]

In the Hill Complex, he calls it the Elliptical building, Mauch found: “masses of rubble, and parts of walls and dense thickets and big trees.”

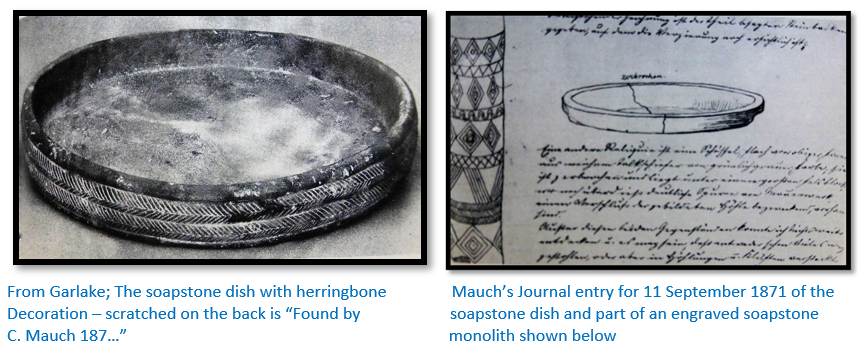

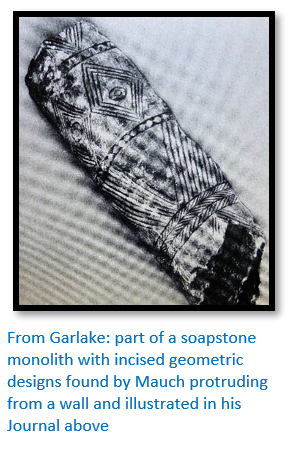

The relics he found included:

- A decorated soapstone dish lying underneath a large walled-up boulder near the Hill Complex

- A decorated soapstone beam protruding from a wall in the Great Enclosure

- In the ‘outbuildings’ now called the Valley Complex: “an object…of iron…[whose] use was a complete riddle to me, but it proves most clearly that a civilized nation must once have lived here. It consists of two triangularly shaped shells which are connected by an iron arc.”[lvii] [clearly an iron gong]

He noted in his Journal that the ruins themselves: “provide really only very few points of explanation…They only offer a guess at their great age, which is clearly suggested by the absence of mortar.” The VaKaranga were clearly relative newcomers to the region and made no claim to having built the stone structures of Great Zimbabwe.[lviii]

Mauch’s letter to missionary Gruetzner of 13 September continues: “Symbaoe or Zimbabye lies 3.5 hours to the east of my already mentioned point, my living site,[lix] therefore on longitude 31°48´and latitude 20°14´ [in fact 30°56´and 20°16´] I learned from the local inhabitants that they themselves have lived here for only 40 years, that the region was quite uninhabited before that time and that, earlier still the Malotse or Barotse lived in the country and near the ruins but they had to flee towards the north [during the Mfecane] They hold the ruins to be sacred and even now, people are said to visit and worship in them. Because of the fear of the present inhabitants it was impossible to discover the reason for this worship. All are absolutely convinced that white people once inhabited the region for even now there are signs of habitations and iron tools which could not have been produced by the blacks. Where this white population remained, whether it was chased away or killed, nobody can tell. This far does the knowledge of the Makalaka, the present inhabitants. But now to the actual ruins; During the short visit to the greatly extended sections it was not possible for me to find any inscriptions by clearing rubble and rocks near entrances. I did not pick up any tools which could point to an age – most of the iron tools, in fact everything that occurred here has been smelted down by the present inhabitants; the Barotse are not believed to have touched anything. Had these ruins been recently built by the Portuguese, they would certainly have given them a Portuguese name in accordance with their habit everywhere, but they may have altered them somewhat.

The ruin can be divided into two parts: the one on top of a 400 feet high granite kopje, the other on a slightly elevated terrace. Both are divided by a flat small valley and the distance is approximately 300 yards. [in fact 680 yards or 620 metres] The rocky kopje consists of an elongated granite massive of rounded shape on which lies a second boulder and on the latter again smaller ones, but still weighing many tons with crags and clefts and caves. On the western part of this mountain and furthermore covering the whole slope from top to bottom are ruins. As everything is filled with earth or is caved-in the reasons for these structures are at present unknown, it is most likely that they represented a fort, unconquerable in those times, to which fact point the many passages, which are now walled up and the rounded and zig-zag alignments of the walls. All the walls, without exception, are built of cut granite stones without any mortar. They are approximately the same size as our bricks, the walls are also of different thickness, they are 10 feet wide on their visible base and 7 to 8 feet on the ruined top. The most remarkable wall stands on the edge of a precipice and is, strangely still very well preserved up to a height of about 30 feet.

The descriptions continue for another two pages but are here omitted.[lx]

Mauch’s prolonged stay

From 12 September 1871 Mauch was stuck at Madzivere’s, Mazarire stating he was “idling and evidently bored” until the 23 October when he went with Adam Renders to Chivi to meet Phillips and obtain supplies. He was back at Chivi a week later to watch a traditional hunt using nets.

The porters sent to the Zoutpansberg returned on the 4 November but he was unable to move on because the local people were busy planting their fields prior to the onset of the rains. Mauch spent this time in November and December, Mazarire calls it his third phase, writing up an ethnography of the VaKaranga based on the lives of a typical boy and girl brought up in their society. This period into January 1872 was only interrupted by an elephant hunt to the present-day Mashava area during which Renders and Mauch quarrelled over the ivory.

Arriving back Renders was visited by a party of amaNdebele whilst Mauch was hidden from their sight – it does seem strange that rumours had not already reached the amaNdebele of his presence.

Toward the end of February Mauch made preparations for his journey to Sena but was delayed by the difficulties of getting porters. Mazarire writes that Mauch tried to upgrade his notes to the level of academic research by interviewing Bebereke, an old man and “son of the last high priest Tenga”[lxi] who father, a spirit medium, had been killed by the predecessors of the VaKaranga chief Chipfunhu Mugabe. Bebereke provided a detailed history stretching back to the Mutapa and Rozvi States and during March and April 1872 Mauch made detailed notes on the justice system, agriculture, religion and music of the VaKaranga. Bebereke described ceremonies held at the Great Zimbabwe site by his father, the last high priest in such detail that Mauch was convinced he was a direct descendant of the priesthood.[lxii] He concluded: “Judging by the answers to my questions it is now beyond doubt that in fact the Jewish religion as it existed in Solomon’s time has been transported here in all its essentials by the Queen of Sheba.”

In reality, as pointed out by Dawson Munjeri, Bebereke was describing a traditional bira ceremony for rain and not to a Jewish one.[lxiii]

The VaKaranga continued the rituals conducted by the former Rozwi who although they never built Great Zimbabwe recognised its spiritual significance and made periodic sacrifices of cattle at the site.[lxiv] Richard Hall whose disastrous excavations of the Great Enclosure and Hill Complex took place at Great Zimbabwe in 1902 – 4 recorded that a sacrifice of goats still took place in 1902. Large quantities of cattle bones were unearthed in the Great Enclosure to confirm these ceremonies.

On his final permitted visit to Great Zimbabwe on 6 March 1872 Mauch cut some wood from a collapsed lintel in a doorway to the Hill Complex and found it was impervious to insects, reddish, scented and with a “great similarity” to the “wood of his pencil.” This was the missing clue: “it can be taken as a fact that the wood which we obtained actually is cedar-wood[lxv] and from this that it cannot come from anywhere else but from the Libanon. Furthermore only the Phoenicians could have brought it here; further Salamo used a lot of cedar-wood for the building of the temple and of his palaces…”[lxvi]

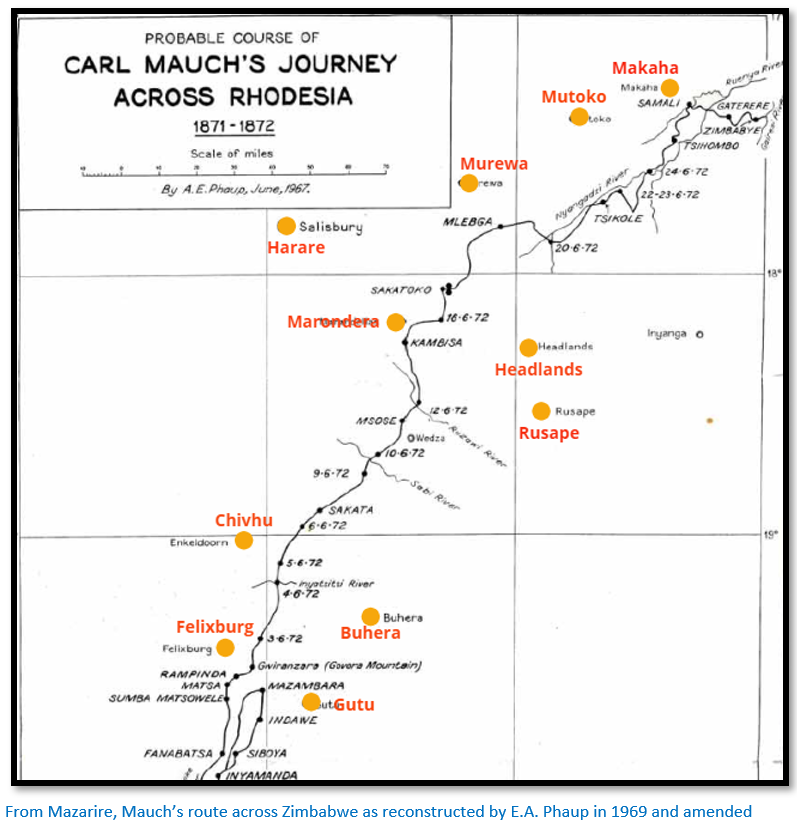

1872 Journey through north-east Mashonaland

The internal tribal politics and tensions between the local Chiefs made the securing of porters difficult but he managed to secure twelve and set out from Bika’s kraal for the Zambesi river but his native porters soon deserted and he was forced to return to Bika’s kraal on 17 April. “I intended to start for the Zambesi in April, but the porters wanted to leave me after some days’ marches. Therefore I had to decide to return and settle for another month in my former quarters. The Matabele undertook a raid during that time in the regions toward the Sabi [Save] river and not for a moment was I certain that they would not try an attack on my small village. Therefore I retired to a rocky cave and barricaded the entrance as best I could. The access was so difficult that only one enemy at a time could have approached. Fortunately they did not dare to attack and they passed by.”[lxvii]

In what Mazarire calls the fourth phase of Mauch’s writing he expresses increased anxiety and frustration. He believed his host Madzivere was stealing from him and that Renders wanted to share in his fame of discovering Great Zimbabwe. At times his poor mental condition resulted in his diary entries making no sense at all.

In May Mauch set off once again. Tabler states that he travelled over the headwaters of the western tributaries of the Save, formerly Sabi river crossing its watershed to the upper Mazowe river travelling north east and discovering what he called the Kaiser Wilhelm gold-field. However the map below shows Mauch’s journey was eighty kilometres to the south-east of the Mazowe river before following the Ruenya river into present-day Mozambique. The Kaiser Wilhelm gold-field is today known as Makaha, approximately 60 kms east-north-east of Mutoko and on the Ruenya river. Dr Carl Peters in 1899 walked through this area from Tete in then Portuguese East Africa crossing the Gairezi to the Ruenya river and this area is marked on his map as the Kaiser Wilhelm gold-field.[lxviii] Again, this was no geological discovery on Mauch’s part but indicated by the pre-European shafts and stopes dug by local people in their search for gold and in the dry season local people were seen panning for gold in the Ruenya.

Mauch says: “Its extraction is very simple wherever it is found in river and stream beds; the natives easily and within a short time wash in a pot sherd so much as they need for one or another purpose. Nobody attempts to own gold in great quantity except the chiefs who, as it were, have the right to possess all the larger pieces and who keep them for the exchange of arms with the Portuguese traders. Usually it occurs in thick flakes, but nuggets the size of hazel nuts appear to be not uncommon. Nowadays the natives do not attempt to produce gold from its matrix, the quartz, but numerous abandoned pits testify that they were formerly intensively worked.

I took the liberty to name such an extensive and according to chief Samaly, very rich field; ‘The Kaiser Wilhelm Field!’ it is bordered by mighty mountain ridges to the north and the south which each have an unclimbable kopje at their eastern limit. The northern twin-peaked kopje I named ‘Bismarck.’ Being nearer to the field it guards its interior as well as the second goldfield on the river Masore (Mazore) while the other kopje in the south I named ‘Moltke’ as it defied for centuries the well-known goldfield of Manica…”

Suffering from bad attacks of fever he reached Sena, a Portuguese settlement on the Zambezi, and from there travelled by boat to Quelimane at the river's mouth. Exhausted and without funds, he obtained the help of a French ship’s captain to reach Marseilles by the end of 1872 and returned to Germany from there.

Recognition at last

Petermann gave Mauch a warm welcome and he spent some time lecturing on his travels and discoveries and received financial assistance from King Karl I and the state of Württemberg to write up his information on Southern Africa which resulted in some recognition of his discoveries. The Royal Geographical Society gave a grant of £25 and the President, Sir Henry Rawlinson said the following to the Secretary of the German Legation who represented Mauch: " The Council of the Royal Geographical Society have awarded this sum as an acknowledgment of the persevering efforts which Herr Karl Mauch has made during seven years to extend our knowledge of the interior of South-East Africa. Landing at Natal, almost destitute of means, this enthusiastic and determined explorer has gradually worked his way northward to the almost unknown region lying between the lower courses of the Limpopo and Zambesi Rivers. Herr Mauch has succeeded not only in rediscovering the abandoned gold-district whence the Portuguese, and doubtless the Arabs before them, even as far back as the remotest antiquity, derived their East African gold, but has brought to light the ruins of an ancient city, revealing by the massiveness of its walls and towers, and its sculptured stones, the former existence here of a foreign civilised people, long anterior to the arrival of the Portuguese. These explorations have been carried on by Herr Mauch year after year, by repeated attempts and amid many privations…”

Petermann had published preliminary reports on Mauch’s travels from 1866 to 1872 using his letters. A more comprehensive account Carl Mauch's Reisen im Inneren von Sued-Afrika 1865-1872 was published, with a map and description of Great Zimbabwe in Petermann’s Geographischen Mitteilungen (Geographical Magazine) in 1874. A further six of Mauch’s sketch maps and two proper geographical maps followed in Geographische Mitteilungen. [lxix]

1874 Journey to Central America

In 1874 Mauch accompanied the naturalist C.E. Otto Kuntze on an expedition to central America. They visited the West Indies, but as they had a personality clash Mauch returned to Germany around the middle of 1874.

Return to Germany

With no formal qualifications and no university degree Mauch was unable to get an official post in a museum to write up a detailed account of his African journeys. He finally became manager in the Spohn and Ruthard cement factory at Blaubeuren, north Wuerttemberg. However, his health had been broken by the fevers suffered in Africa; tormented by sleeplessness[lxx] on 26 March he fell from a window causing injuries to his skull and breaking his back; he died in hospital at Stuttgart, Germany on 4 April 1875.

He was buried three days later in the Prague cemetery. Many of his colleagues donated for a memorial stone to Mauch which was dedicated on 18 June 1876. This was destroyed in World War II but reconstructed in 1991-2 by the main State Archives in Stuttgart.

Mauch’s achievements

Mauch was an excellent observer and recorder of objects that interested him. He was furthermore a good geologist for his time assembling his data into geological maps. The first was completed in 1868 after his journey to Inyathi. He drew a second geological map in 1871 on a scale of about 100 miles to the inch (1:6 336 000) and sent it to Petermann with some geological sections and notes, but it was not published. In the map legend the various geological formations are arranged in chronological order. Mauch recognised the superposition of the quartzites of the Pretoria Group on the dolomite and distinguished the granites of the Bushveld Igneous Complex from the widely distributed older granites and he was the first to map the overall geological structure of the Transvaal and surrounding territories. Mauch's biographer, Mager gives a list of six sketch-maps and two maps drawn by him.

Although Mauch is not known to have widely collected natural history specimens, he did send seeds to M.J. McKen at the Durban Botanic Garden and made some excellent botanical drawings with good descriptions. Although his views became very prejudiced when viewed through a “German prism” he was a keen observer and man of great determination and energy. Burrett writes: “Undoubtably Mauch was influenced by the Eurocentric ideas of his day – there are elements of racism, German nationalism and at times idiosyncratic bigotry, self-righteousness and at times, self-pity.”[lxxi]

His gold discoveries made him a pioneer of the southern African gold industry, while his cartographic work contributed significantly to the development of geographical knowledge of the region. He says himself: “The crowning work of all my travels and one of which I permit myself to be somewhat proud, is the discovery of the already mentioned Ruins of Zimbabye. When in 1867 I first heard the ruins discussed as fabulous buildings, I decided to visit them. In 1868 on the Limpopo their approximate situation was described to me by a native, but several attempts to reach them failed until finally, on the 5 September 1871 I was lucky enough to be the first white man to set eyes on them.”[lxxii]

Unfortunately his claim does not agree even with his own Journal for 1871:

3 September – Renders, Mauch and Phillips climb Mt Chomuzanda (Spook mountain) with local guides

5 September – Renders, Mauch and Phillips obtain permission from VaKaranga chief Chipfunhu Mugabe to visit Great Zimbabwe

11 September – Renders, Mauch and Phillips and guides visit Great Zimbabwe

Places named after Karl Mauch

There is a permanent exhibition on Karl Mauch in the museum under the Y castle at Stetten im Remstal, Württemberg. Mauchsberg a mountain peak south-east of Lydenburg in the South African province of Mpumalanga was named after him. In addition there is:

- Mauch Road in Pietermaritzburg

- Carel Mauch Street in Phalaborwa

- Karl Mauch School in his birthplace Stetten im Remstal, Württemberg

- Mauchstrasse in Scwabisch Gmund

- Mauchweg in Stuttgart-Stammheim

- Carl-Mauch-Weg in Freiberg am Neckar

- Mauchsberg , a settlement in the Thaba Chweu Local Municipality in the Ehlanzeni District

Acknowledgements

For much of the detail of Mauch’s visit to Great Zimbabwe and his journey through Zimbabwe I am grateful for the article written by the Zimbabwean historian Gerald Mazarire which is listed below and includes the map by Phaup and a detailed map of the Great Zimbabwe area. Interested readers should read this article for further information. F. O Bernhard and his wife did a great service to historians by editing and translating Mauch’s Journals which make an invaluable reference source.

References

Burke, E.E. (Ed.) The Journals of Carl Mauch: His travels in the Transvaal and Rhodesia, 1869-1872.

Salisbury: National Archives of Rhodesia, 1969

R.S. Burrett. Karl Gottlieb Mauch (1837-1875) Heritage of Zimbabwe. Publication No 27, 2008

F.O. Bernhard (Editor and translator) Karl Mauch, African Explorer. C. Struik (Pty) Ltd, 1971

Garlake, P.S. Great Zimbabwe. New York: Stein & Day, 1973.

G. Caton-Thompson. The Zimbabwe Culture. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1931

P.S. Garlake. Great Zimbabwe. Thames and Hudson, 1973

J. Liew. The Impact of Prejudice on the History of Great Zimbabwe. Ancient History Encyclopaedia, 19 August 2019

G.C. Mazarire. Carl Mauch and some Karanga Chiefs Around Great Zimbabwe 1871-1872; Re-Considering the Evidence. South African Historical Journal – September 2013.

D. Munjeri. Great Zimbabwe: A Historiography and History, Carl Mauch and After. Heritage of Zimbabwe. Publication No 7, 1987

C. Peters. The Eldorado of the Ancients. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1977

C. Plug (Compiler) Biographical database of Southern African Science

A. W. Rogers. The Pioneers in South African geology and their work. Transactions of the Geological Society of South Africa, 1937, Annexure to Vol. 39, pp. 1-139.

E.C. Tabler. Pioneers of Rhodesia. C. Struik (Pty) Ltd Cape Town 1966

E.C. Tabler. The Far Interior. A.A. Balkema. Cape Town 1955

J.P.R. Wallis. (Editor) The Southern African Diaries of Thomas Leask. Chatto and Windus, London 1954

Wikipedia

Appendix from the website geni.com; a statement written by Hendrik Jacobus Renders

"My father was born in Germany, in 1822, of German parentage. At a very early age he emigrated to America, and from there, at the age of about twenty, adventure led him to South Africa on an American trading ship. In Natal, he joined the Voortrekkers, and along with the Boer leader, Andries Pretorius, he crossed the Vaal river after the defeat of the Boers at Boomplaats, in 1848. They eventually settled at a place named Zoutpansberg, not far from the southern corner of Mashonaland.

While living there he married Elsie Pretorius, the leader's daughter. Every winter Adam Renders, with a small party of friends - Roets, Suel, Marnwick, Sultana, and a J. de Cout, used to cross the Limpopo river into what is today Southern Rhodesia in order to trade, hunt, and explore the country. In the winter of 1867 (not 1868 as some books say) Adam Renders came upon the Zimbabwe Ruins. He intended to annex the country for the Transvaal Republic, and having gained the confidence of Sangoma, the chief of the Mashonas in that region, he promised him guns, ammunition and help, to defend himself against the neighbouring tribes, in exchange for the land reaching from the ruins - and including them - to the Limpopo River. Sangoma agreed, and Render's party returned to Zoutpansberg to get the guns and ammunition.

In 1868, my father again went to Mashonaland, bringing along with him his wife and family. He showed my mother the land and the place where he intended to make his homestead. It was near where Morgenster mission station stands today. But mother strongly disapproved of settling so far from civilization, and amongst the native population and no wonder! Mother carried with her to the day of her death, the scars from seventeen assegai wounds which she received during fighting with the Zulus in the Transvaal. She also knew that there was continual danger from raiding parties and Matabele warriors. The state of fear in which the natives of these parts lived can scarcely be imagined.

So father took her back to the Transvaal, but he himself was quite determined to come to that district each year during the healthy season and to persuade more and more people to join him in making their home in that beautiful region.

One time when father and his friends trekked into the country, they found Sangoma in trouble again with neighbouring chiefs. an expedition was organized to drive Sangoma's enemies away. This was successful but on the return journey , a native shot a poisoned arrow at my father and wounded him in the shoulder. It brought about his death and he was buried by his gun bearer about eleven miles north of Zimbabwe Ruins. Before he passed away he wrote a note to my mother explaining everything.

Sangoma was much grieved to hear of the death of his protector and he sent messengers to my mother to come and fetch Sadama's (as the natives called him) belongings, which consisted of cattle, ivory, etc., which he had traded. But mother was afraid to come to the country again, as she feared that Sangoma's enemies would lay a trap for her. The country was still in a very wild state.

A few years later, Njobo, the gun bearer offered to show my brother, W A Renders, father's cattle and ivory and to explain to Sangoma that he was Adam's son. At the time, however, circumstances did not allow my brother to go, so we never got any of father's goods".

The above account doesn't support the claim that Renders lived with a native woman - the daughter of chief Bika's, with whom he fathered a child. Chief Bika was a village headman under Chief Charumbira who resided near the Bondolfi Mission on the western foot of Chigaramboni Mountain.

[i] The Pioneers in South African geology and their work, P77

[ii] Ibid, P77

[iii] Bernhard, P209-223

[iv] Bernhard, Preface

[v] Burrett, P74

[vi] Ibid, P2

[viii] Bernhard, P5

[ix] Ibid, P7

[x] Ibid, P9

[xi] Tabler, the Far Interior P287

[xii] Bernhard, P23

[xiii] Tabler, the Far Interior P287

[xiv] Bernhard, P184-5

[xv] Ibid, P68

[xvi] Ibid, P70

[xvii] Wallis, The Southern African Diaries of Thomas Leask, P88

[xviii] Bernhard, P81

[xix] Tabler, The Far Interior P288

[xx] The Pioneers in South African geology and their work, P78

[xxi] After his excursion east of Lydenburg to the 7,247 ft (2,209 metres) summit of one of the highest points in the Transvaal, the mountain was named Mauchsberg

[xxii] Tabler, Pioneers of Rhodesia P109

[xxiii] Ibid

[xxiv] Bernhard, P186

[xxv] Ibid, P185. These supplies included cotton ware, woollen blankets, brass wire, glass beads; the usual trade goods which Mauch hoped to use on a journey northwards into central Africa.

[xxvi] Ibid, P32

[xxvii] Extremely unlikely…Hartley was an acclaimed story-teller, no tale was ever more dramatic than his, but he left nothing written.

[xxviii] Bernhard, P187

[xxix] Mazarire, P15

[xxx] Bernhard, P190

[xxxi] Mauch’s Journal, 23 July 1871. Burke P117 / Garlake, P63

[xxxii] Near the Phabeni gate of the Kruger National Park

[xxxiii] Bernhard, P206

[xxxiv] Pioneers of Rhodesia P109

[xxxv] The Pioneers in South African geology and their work, P82

[xxxvi] Mazarire, P10

[xxxvii] Bernhard, P209

[xxxviii] George Phillips went with the Hartley party to Mashonaland in 1867 [See the article on the Hunter’s Road] and obtained a concession to seek minerals from Lobengula with Leask, Westbeech and Fairbairn in 1884 [See the article Were Lobengula and the amaNdebele tricked by the Rudd concession?]

[xxxix] Tabler, Pioneers of Rhodesia P109

[xl] Wallis, The Southern African Diaries of Thomas Leask, P80

[xli] Mazarire, P15

[xlii] Tabler, Pioneers of Rhodesia P129

[xliii] Mazarire refers to the place name where Render lived as Madzivere

[xliv] Tabler, Pioneers of Rhodesia P109

[xlv] Mazarire, P16

[xlvi] Ibid, P17

[xlvii] Ibid, P15

[xlviii] Bernhard, Cover

[xlix] Mazarire, P1

[l] The Impact of Prejudice on the History of Great Zimbabwe

[li] Mauch’s Journal, 1 September 1871. Burke P139 / Garlake P63

[lii] Book review of Gold und Ruinen in Zimbabwe, P336

[liii] Mazarire, P13

[liv] Garlake, P52

[lv] Bernhard, P122

[lvi] Mauch’s Journal 11 September 1871. Burke P139 / Garlake P63

[lvii] Ibid. Burke P146-8 / Garlake P63

[lviii] Garlake, P63

[lx] Bernhard, P118-9

[lxi] Summers P209

[lxii] Garlake, P63

[lxiii] Munjeri, P2

[lxiv] Ibid, P180

[lxv] According to Summers P131 in fact a local hardwood ubande or mutuvuti (Spirostachys Africana) Dawson Munjeri (P3) states this wood is used traditionally to drive away evil spirits and witches familiars, zvidhoma and thus its use at main entrance is understandable.

[lxvi] Mauch’s Journal 6 March 1872. Burke P189-91, Garlake P64

[lxvii] Bernhard, P224

[lxviii] Peters, P154

[lxix] The Pioneers in South African geology and their work, P82

[lxx] Ibid, P83

[lxxi] Burrett, P74

[lxxii] Bernhard, P233