Thomas Baines and the Hartley Hills goldfield

This was a time when many European powers jostled to acquire new territory in Africa; Portugal claimed that Matabeland and Mashonaland had been ceded to them by the Emperor of Monomotapa three hundred years before.

None of the early mining efforts undertaken at Tati and at Hartley Hills in the 1870’s were ultimately successful. The early indications of gold from samples taken at the surface did not continue at depth when they sunk shafts and most of the parties simply ran out of cash, sold or abandoned their claims and went down to the diamond fields which were a much greater commercial success.

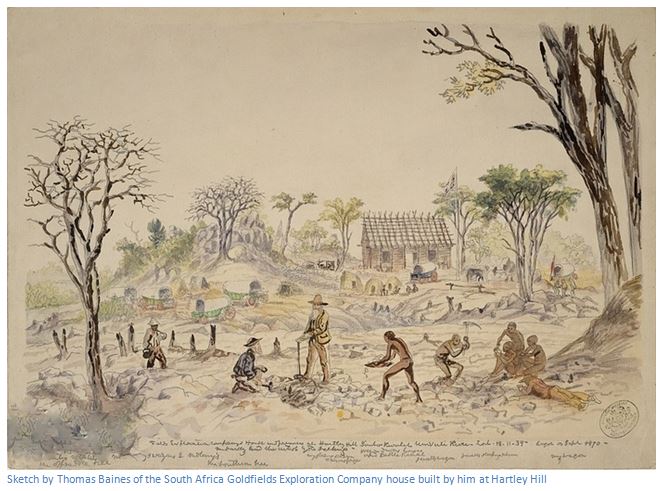

Thomas Baines made great efforts on behalf of the South African Gold Fields Exploration Company and obtained the first written agreement with the amaNdebele King Lobengula to mine for gold.

The Baines Concession was never repudiated and but for Thomas Baines’ untimely death, his Concession would probably have prevailed over the Rudd Concession. As it turned out, the Baines Concession was never taken up and Hartley Hills remained a fabled El Dorado until the settlement of Old Hartley in 1890.

All the work Thomas Baines carried out on behalf of the South African Gold Fields Exploration Company came to nothing as the company went bankrupt and Baines was left out of pocket.

His maps, the diary descriptions of all he observed, the sketches and paintings provide the most valuable insight into life from the 1840’s to the 1870’s in southern Africa generally and of modern-day Zimbabwe in particular.

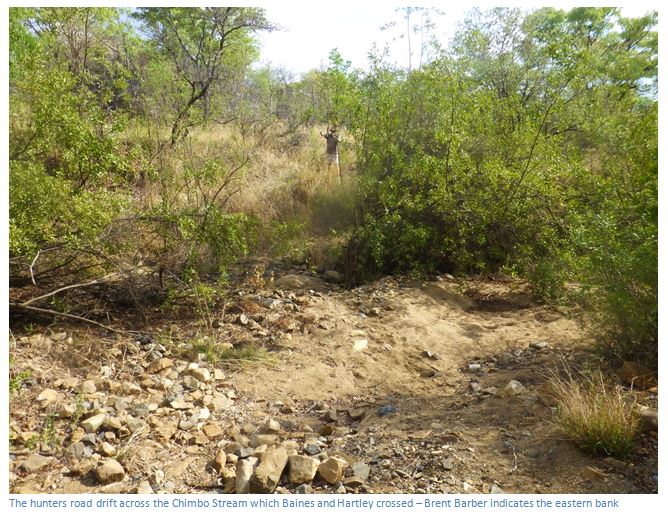

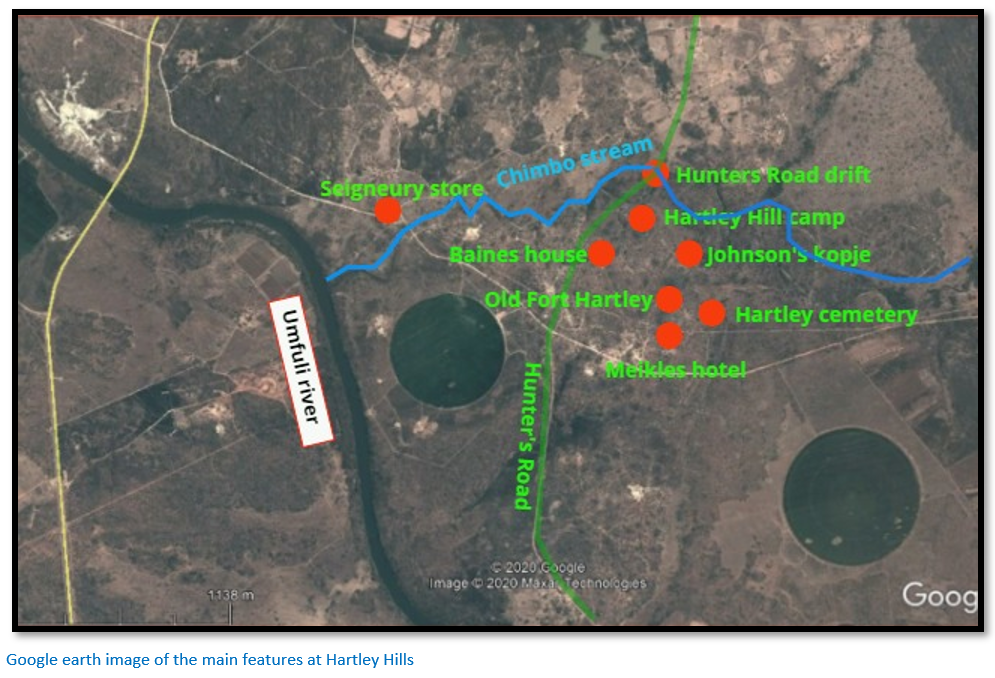

Hartley town on the A5 national road is now named Chegutu. The original Hartley Hill goldfields are east of the junction of the Mupfure River (formerly the Umfuli) and the Chimbo stream (sometimes marked Zimbo) The area is easily reached from the main Harare Bulawayo A5 National road 71 KM from Harare, by turning left off the National road at the roundabout, south toward Ngezi Mine. At 7.2 KM continue past Chengeta Safari Lodge turnoff on the left and at 15.73 KM reach Seigneury Road intersection. Turn left onto the gravel road, 17.54 KM go to the left of the Seigneury store, 17.69 KM cross the bridge over Chimbo stream, 18.00 KM pass the stamp mill on your left, 18.62 KM stay on main gravel road, pass old gold diggings on your right, 19.11 KM a farm track turns left for Fort Hill. (i.e. 3.3 KM from the tar turn-off) 19.27 KM take right-hand fork, 19.62 KM park car and the fort is on the summit of the kopje to your left. Johnson’s kopje is to your right. 350 metres northwest of Johnson’s kopje are the two peaks of Hartley Hill mining camp, follow the footpath which traces the hunter’s road to the old drift across the Chimbo Stream.

See the Google earth image below for the general layout.

GPS reference for Fort Hill: 18⁰12′05.81″S 30⁰23′46.11″E

GPS reference for Johnson’s kopje: 18⁰12′01.16″S 30⁰23′47.41″E

GPS reference for the cemetery: 18⁰12′12.55″S 30⁰23′45.19″E

GPS reference for Hartley Hills mining camp: 18⁰11′53.32″S 30⁰23′40.59″E

GPS reference for the Hunters Road drift across the Chimbo Stream: 18⁰11′46.61″S 30⁰23′41.70″E

For general background refer to the article Pre-Colonial Mining in Zimbabwe on the website www.zimfieldguide.com which relates how the 1830’s brought complete disruption to pre-colonial gold-mining as Mzilikazi crushed the remnants of the Torwa and Rozvi States and brought some of the Mashona tribes under his sway: Zwangendaba swept up through Zimbabwe on his way to Malawi and Tanzania and finally the Shangaans, people of Soshangane, settled in southern Mocambique and Manicaland.

Henry Hartley emigrated from England as a child with the 1820 settlers. He was trained as a blacksmith, but took up farming in the Magaliesburg when he moved to the Transvaal (now Gauteng) From his farm, Thorndale, he made hunting trips to the north almost every year in search of ivory and ostrich feathers. He gained a good reputation as a fair man and elephant hunter; both Mzilikazi who called him “Keeper of the King’s Elephants” and Lobengula, trusted and liked him. From 1865 the site of Hartley Hills was where he camped every year at the end of the old Hunter’s Road.

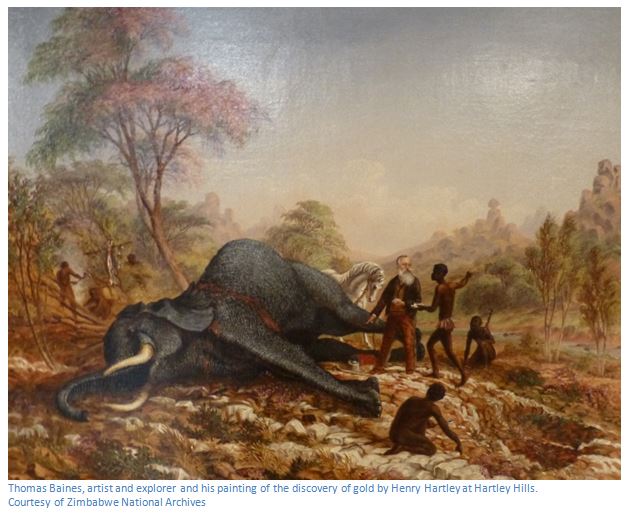

Interest in gold exploration in the interior revived when Henry Hartley found gold reef in “ancient workings” north of the Mupfure River (formerly the Umfuli) although he could not remove samples due to a prospecting ban imposed by Mzilikazi. However the legend goes that a shot and dying elephant collapsed on a gold bearing quartz outcrop. This historic incident is preserved for all time by an original painting by Thomas Baines in the National Archives of Zimbabwe which shows Henry Hartley in 1866 with a dead elephant lying on the ancient workings and the white quartz gold bearing reefs in the foreground.

The following year, Karl Mauch, a German explorer and geographer, confirmed the discovery of gold reefs and ancient workings at Tati, near Francistown in Botswana and his sensational accounts of the goldfields and the mystical accounts of the origins of Great Zimbabwe led many newspapers to print the story as the rediscovery of King Solomon’s mines. At Potchefstroom, in December 1867, Hartley and Mauch announced the extent of the goldfields, thus beginning the first gold rush as prospectors and miners from Europe and Australia began the long trek northward up the missionaries' road.

In 1867 Henry Hartley guided Mauch to the site, who confirmed the discovery of gold and announced to the world the existence of what became known as the “Northern Goldfields.” The remote hunting outspan became the focus of world-wide attention and numerous concession hunters converged on the capital of the now dying King Mzilkazi.

Thomas Baines describes how Henry Hartley dare not openly assist Mauch in searching for gold reefs as his Matabele servants would ask: “what have you to do with seeking stones? The King gave you leave to shoot elephants.“ Nevertheless, Mauch received clandestine help and made some hasty examinations of the reefs between the the Serui and Mupfure Rivers and reported: “there the extent and beauty of the goldfields are such that I stood as if transfixed, and for a few minutes was unable to use the hammer…thousands of persons might work on this extensive gold field without interfering with one another.”

As a result of this unwelcome publicity the Matabele expected a rush of fierce and lawless desperadoes and their anger was directed at those who had spread the news of gold, especially Henry Hartley, who at one time feared for his life. However he was spared because the Matabele respected him for his honesty and because the Rev. Lee pleaded on his behalf. The first organised prospecting arrivals were the Durban gold Mining Company who travelled to Matabeland in 1868 and proceeded to Inyati where so many of the party died from malaria that they gave up their quest and turned back.

But fabulous tales of the goldfields richness continued to circulate; one specimen possessed by the Chamber of Commerce in Port Elizabeth was said to be worth the equivalent of £12,000 per ton!

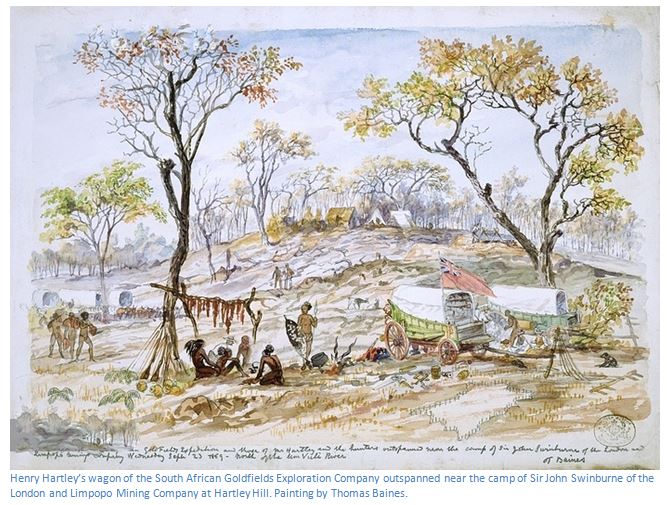

Sir John Swinburne formed the London and Limpopo Mining Company and reached the Tati on 27 April 1869 from Durban and began mining operations along with other parties already there.

Another group of investors in Natal formed the South African Gold Fields Exploration Company and the leadership was offered to Thomas Baines who arrived back in Durban in early 1869. CJ Nelson was appointed chief geologist and RJ Jewell the company secretary. Meetings were held, and about £3,000 subscribed for shares to equip a party of 34 Australians to carry out mining on the Tati goldfields.

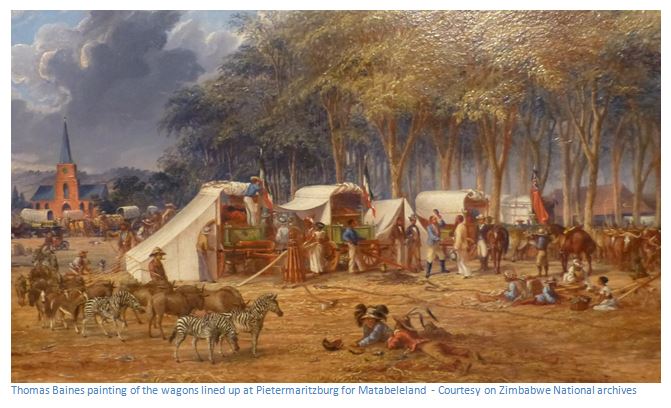

At Durban the wagons of the Baines party met up with the Germans, including Edwin Mohr and Adolph Hubner and Baines says: “Our four wagons standing side by side, flying the British and North German flags, like a little squadron busily fitting for a long voyage, were for many days a centre of interest upon the market square of Pietermaritzburg.”

After the long journey they arrived on the edge of Matabeland in mid-June and requested permission to enter the AmaNdebele Kingdom; but Mzilikazi had just died and the succession was still undecided, so it was only on the 7th July they were given an escort to the Regent Um Nombata to consider their application to enter Mashonaland. After presenting gifts and a formal audience they were granted permission and told they may keep any gold they found. Even here at Inyati, Nelson was finding traces of alluvial gold.

They travelled the hunter’s road behind Sir John Swinburne and his party between modern Gweru and KweKwe and saw numerous gold bearing quartz reefs and found alluvial gold on the Sebakwe River. Thomas Baines rode on ahead of the wagons by horse to meet up with Henry Hartley and halting for the night at the Serui River, he saw the fires from Sir John Swinburne’s camp at Hartley hills reflected on the clouds. Next morning he came upon Hartley’s wagons, where he was welcomed by the wives and children as the men were away hunting.

Hartley was pleased to see him, but dared not help Baines with finding gold until his head man, Inyoka, “Serpent” had confirmed with Baines’ own escort Inyassa, that he had received permission to explore for gold. Once this was confirmed, Hartley invited Baines to accompany him on his next hunting expedition and also promised to show him examples of quartz-reefs that he had seen. Beyond the Mupfure River the hunter’s road barely existed; but the hunters had blazed rough trails to follow the elephant towards the Manyame River.

Some Mashona from a village about thirty-five miles to the north-west informed them that there were pits in their vicinity from which their forefathers used to dig a kind of metal, which they knew nothing about. Baines set off on his horse at the centre of a long procession, his head man, Inyassa, carrying his rifle, and two or three other men his blankets and other necessaries, and crossed large tracts of well wooded granite country in which large white quartz reefs were visible.

Next day after reaching Maghoondas Village a guide took him to the pits from which gold used to be extracted. The quartz reef was bordered by clay slate and other rocks and traversed a valley shut in by rounded hills. The pits were in groups of six or eight, 1.2 metres wide (4 feet) and some of them 3 metres deep (ten feet) His guide fetched him a quartz specimen and on his return to camp he saw other quartz reefs and ancient diggings; as well as shooting a rhino and two antelope.

On his return Baines met Hartley and they crossed the Chimbo stream just above its junction with the Mupfure River, but a wagon was damaged in the drift and they halted for repairs under a group of granite hills with quartz reefs at their base. Hartley picked out some quartz reef in which they found gold and saw extensive ancient workings nearby.

Next day Inyoka, Hartley’s headman took Baines to the Hartley Hills “ancient workings” about a mile in length, with heaps of earth excavated from the holes which were about 1.2 metres wide (4 feet) and 3.7 metres deep (12 feet) Sometimes the holes were joined, forming a large pit with tall trees growing from them, proving they had not been worked for some years.

North of the Mupfure River Sir John Swinburne had sunk two shafts about 7.6 metres deep (25 feet) and obtained samples of gold in quartz; some white and crystalline, others red or yellow with iron oxides. However, the reefs petered out and after quarrelling with practically everyone, Sir John left Hartley Hills and his successor, Capt. Arthur Levert, concentrate on Karl Mauch’s southern goldfield between the Shashe and Ramokgwebana Rivers in modern day Botswana. Baines and Nelson returned to the Chimbo River to examine the reefs and marked off their first claim in the presence of their headman Inyassa and in recognition of Henry Hartley; he named the locality Hartley Hills.

Messages were soon received from the amaNdebele saying all visitors must leave the country as the Matabele wished to be uninterrupted whilst they choose their new King. On their return to Inthlathlangela the indunas asked the headman Inyassa if Baines had asked permission to hunt for elephants and then looked for gold and also dug holes without permission. However Inyassa stated Baines had not looked for gold and his testimony cleared Baines.

On the 26th January 1870 Lobengula was proclaimed King of the amaNdebele in succession to Mzilikazi. In April, Lobengula sent greetings and confirmed to John Lee the rights granted by Mzilikazi to Thomas Baines and on another occasion said: “Mr Baines can have the northern gold fields.” Together they visited Lobengula and found wagons nearby laden with presents that have been given to his father Mzilikazi: “beads, guns, pistols, Colt's and other revolvers, corroded into masses of rust, and every conceivable article of use or luxury that a traveller could offer to a barbarian monarch, among which he says I will only mention a splendidly mounted Scottish garter dirk, and a pair of magnificent ram's horn mulls, mounted in massive silver.”

After eating with Lobengula and having sung his praises, Baines was invited to make his request. Baines told Lobengula that Um Nombata had given him permission to explore and Nelson had made a report on the goldfields and he hoped Lobengula would grant him a treaty. Lobengula asked him what the boundaries would be; Baines requested from the Gweru to the Manyame Rivers. Lobengula said as he was only a newly made King, he could not sell land; but he would give Baines permission to seek and dig for gold anywhere within those rivers and to use wagons to bring in machinery to crush the ore. John Lee requested permission for a house for Baines to live in and for storehouses, Lobengula said these things were covered in his grant and Baines promised not to exceed the King’s permission.

When Baines and Lee returned to camp they discussed a suitable present for Lobengula; Baines decided to give his salted riding horse which had cost £75 with a saddle, bridle and a rifle to make the gift up to £100. Whilst camped here Lobengula’s rain-makers objected to their flags which they hung above the wagons, you see them in Baines’ paintings of Pietermaritzburg and Potchestroom, which were thought likely to drive away the rain. Baines learned that it was the white border of the Union Jack which they objected to; his white trousers and shirts could not be hung out to dry without frightening away the rain clouds; but there was no objection to black colours!

Baines returned to Hartley Hill where he marked the boundaries of the South African Goldfields Exploration Company gold claim and then built a house for Nelson and the working party with two rooms using mopane poles to support the roof. After an exploration trip of 40 kilometres down the Mupfure River he met Thomas Leask and Thomas Moloney who told him that of the party of seventeen who had arrived a month before, seven had died of fever including George Wood’s wife, child and mother-in-law Mrs Fraser, Paul Jebe a German explorer, McDonald, Toris, a wagon driver and Willie Hartley. Baines strangely omits James O’Donnell who died on the same day as Willie Hartley, 29 May 1870. Another who died that year was Henry Lamont McGillewie, a trader who became an elephant hunter because it is said he failed in business. He had a famous shooting horse named Colbrook and died of fever at the Serui River, near Hartley Hills.

Together with Robert Jewel he made a number of local journeys; one to the south east over the watershed to Umtigesa’s kraal where he noticed the Mashona huts were usually built on the most inaccessible peaks as a refuge from the Matabele raiders and often had a ladder to their huts built on isolated boulders. Another trip was down the Mupfure River about 40 kilometres where they saw ancient workings and on their return to Hartley Hill, Baines, Leask, and Jewell joined Henry Hartley to visit his favourite son Willie’s lonely grave near the confluence of the Mapfure River and Chirundazi stream which they did on the 29 August 1870.

Baines joined Hartley on a trip to the northwest where they come upon the ruins of a house occupied by white men that he thinks was occupied fifty years before [Note: this is likely to be the Portuguese feira of Maramuca] The chief geologist of the company, Nelson had still not arrived on his return to Hartley Hill, so he organised efforts to begin mining the gold-bearing quartz.

On 9th September Baines rode with George Wood 100 kilometres to the northwest and about 10 kilometres east of Maghoondas where Wood bought a quill of gold amidst the extensive gold workings. They saw a heap of quartz that has been burned ready for crushing, with another heap piled up with wood ready for burning. Baines considered this is good evidence that the gold fields had being worked by the local Mashona and were not “ancient” and still being furtively mined. They tried to buy more gold, but the Mashona were terrified of the amaNdebele who had warned them not to have anything to do with the “King’s rocks.” On their way back to Matabeland Hartley and Baines encountered a herd of two hundred elephant and Hartley killed eight of them; but Baines does not have Lobengula’s permission to shoot elephants and they saw more promising looking quartz reefs on the Sebakwe River.

With the summer rains approaching, the hunting parties began to trek back to Matabalaland. Reverend Thomas Morgan Thomas had been recalled from Inyati Mission by the London Missionary Society to answer charges he had spent too much time trading. They were welcomed back by Rev. Mr and Mrs Sykes and Mr and Mrs Thomson. When Baines asked to see Lobengula, his brother M’Poctlo said: “why need you be troubled, do we not all know the King has given you the country?” Mr and Mrs Thomson accompanied Baines on the way to see Lobengula and visited the future site of Hope Fountain Mission. [see Hope Fountain article on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] John Lee helped the missionaries explain the principles and purpose of a missionary society and Watson explained the necessity and benefit of religion to help persuade the King to grant land to the missionaries.

Baines discussed with John Lee whether he should ask for a written document on behalf of the South African Goldfields Exploration Company, but decided to trust to Lobengula’s verbal promise as even the old hunting rights granted by Mzilikazi were held as law. Lobengula examined his quartz samples and saw how little gold would be obtained. A few days later on 23 November 1870 Lobengula confirmed all of the privileges he had granted, but was anxious the Company did not infringe his territorial rights in Mashonaland. Baines said he had given his word and would rather resign than break his promises. Lobengula refused a gift, or tribute in case it looked as though he was parting with his country and Baines said he would make an annual present, adding he thought Lobengula’s conduct would ensure the friendship of the Colonial and British Government.

Whilst at Lobengula’s kraal he received a letter from Senhor Costa, Governor of Quelimane in Mocambique, saying the land north of the Limpopo was part of the district of Sofala and he could not explore for gold, or make treaties without the permission of the King of Portugal. He claimed Portugal owned all the territory through a treaty made with the conquered Emperor of Monomotapa three hundred years before! Baines replied saying he was not aware of the Portuguese territorial right to Matabeland which had been conquered by Mzilikazi, and that his son Lobengula had given his company the right to search for gold.

Later Baines met the Portuguese Consul in Potchefstroom, who was more pragmatic and thought Portugal should encourage Britain in developing the goldfields by opening its ports and suggested that Baines should build a road from Hartley Hill down to the coast at Sofala.

Baines reached Pietermaritzburg on 30 January 1871 to discover that the South Africa Gold Fields Exploration Company had not completed their negotiations with the mining company that was to succeed it and that the Directors required a written document signed by Lobengula agreeing to their mineral rights. The Company ran out of money and never reimbursed Baines for his expenses and he was forced to work again as an artist to make a living. His enthusiasm for the northern goldfields at Hartley Hiills did not wane, he mortgaged his house in England and was given credit by traders who were impressed by his enthusiasm.

On 16 May 1871 he left again for the interior and reached the King’s kraal on 12 August where Lobengula received Baines with his usual friendship. John Lee was aware of the royal protocols and after several days Baines raised the subject saying that he was personally very satisfied with the King’s word, but that his Company feared that he might die and then doubts might arise as to the exact details agreed upon and begged for an agreement in writing. Lobengula replied: “yes, I know it is the custom of the white man and you shall have a writing.”

Lee and Baines agreed the document should avoid all legal phrasing and should be written as nearly as possible in the King’s words. So after drafting a number of other letters for Lobengula, the day came on the 29 August 1871 when the agreement was read and Lobengula signed with his X mark and with a seal made of box wood on which Baines had carved; “Lo Benguela.” After farewells, Baines set off on the 1 September via Hope Fountain and then took his wagon to John Lee’s farm at Mangwe where he stayed until 26 September before setting off once again for Pietermaritzburg.

However in the end nothing came of all his long journeys and successful diplomacy and he never returned again to the northern goldfields. He was left to clear up the financial mess of the failed South Africa Gold Fields Exploration Company. Full of enthusiasm he planned a new trip to the Tati gold district to take a crushing plant, and had prepared all his outfit and waggons for the journey when he died of dysentery at Durban on the 8th May, 1875!

Acknowledgements

T. Baines. The Gold Regions of South Eastern Africa. Books of Rhodesia 1968

Col. A.S. Hickman. Norton District in the Mashona rebellion. Rhodesiana No. 3. 1958

P.S. Garlake. Pioneer Forts in Rhodesia 1890 -1897. Rhodesiana No. 12. Sept 1965.

W.H. Brown. On the South African Frontier. Books of Rhodesia 1970

Col. A.S. Hickman. Men who made Rhodesia. BSAP Co. 1960

The ’96 Rebellions. BSA Co. Books of Rhodesia 1975

Ken Calder who accompanied me on my first visit and Brent Barber who came on the second visit.

T.V. Bulpin. To the Banks of the Zambezi. Nelson 1965.