Home >

Mashonaland East >

The story of a Trooper’s experiences in the Imperial Yeomanry and Rhodesia Field Force during the second Boer War 1899 - 1902

The story of a Trooper’s experiences in the Imperial Yeomanry and Rhodesia Field Force during the second Boer War 1899 - 1902

Boer War disasters for the British Army resulted in the formation of the Imperial Yeomanry

The second Boer War (11 October 1899 – 31 May 1902) between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics of The South African Republic and the Orange Free State began with the British Army suffering three humiliating defeats during ‘black week’ of 10-17 December 1899 at the battles of Stormberg, Magersfontein and Colenso where they lost 2,776 men killed, wounded and captured.

The British government realized they were going to need more troops than the regular army could provide and issued a Royal Warrant on 24 December 1899 which allowed volunteer forces to serve; this officially created the Imperial Yeomanry (IY) The Royal Warrant asked standing Yeomanry Regiments to provide service companies of approximately 115 rank and file, 1 Officer and 4 subalterns below the rank of Captain. Many British citizens, usually mid-upper class, volunteered to join the new regiments, although many left for South Africa with little skill in handling and riding horses and poor shooting skills.

Officers and men were required to bring their own horses, clothing and saddlery with the Government providing arms, ammunition, camp equipment and transport. Several of the Companies were raised by private individuals, including the 47th Company (Duke of Cambridge’s Own) the Earl of Dunraven’s ‘Sharpshooters’ the 19th Battalion ‘Paget’s Horse’ and Lord Latham’s 20th Battalion ‘Rough Riders.’

The first contingent of recruits to travel to South Africa was made up of 550 officers and 10,371 other ranks within 20 battalions of four companies each, except the 8th and 16th Battalions which had three companies each. The Battalions began to arrive in Cape Town between February and April 1900, except for the 17th and 19th Battalions which were integrated into the Rhodesia Field Force and were sent to Beira in Portuguese East Africa, now Mozambique. Sharrad Gilbert was a member of the 17th Battalion and it is with these two battalions that this article is wholly concerned.

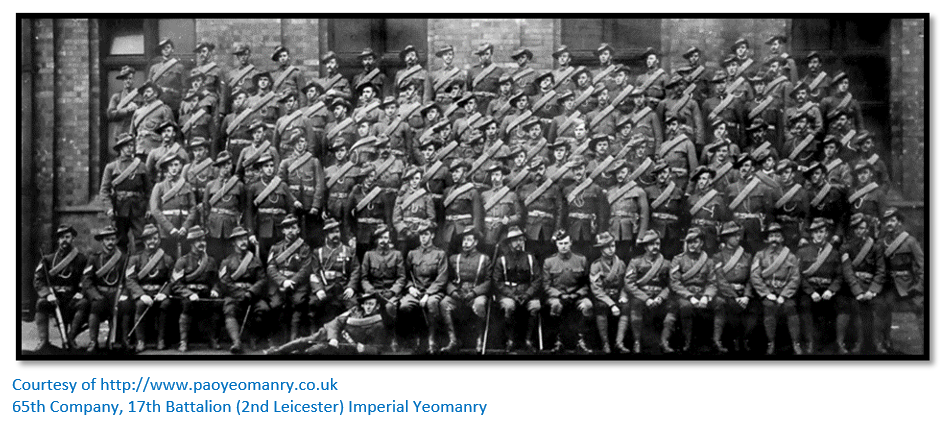

65th Company, 17th Battalion (2nd Leicester) Imperial Yeomanry

The Rhodesia Field Forces’ (RFF) initial task was to create a second front to the north of the Boer forces, but once in Marandellas the force would split, some heading south to Mafeking, now Mahikeng, which was relieved from its 217 day Boer siege on 17 May 1900, while others, including Gilbert in 65th Company, maintained a presence in northern Mashonaland to deter Mashonaland natives who were again becoming restive while Britain had her hands full with the Boers.

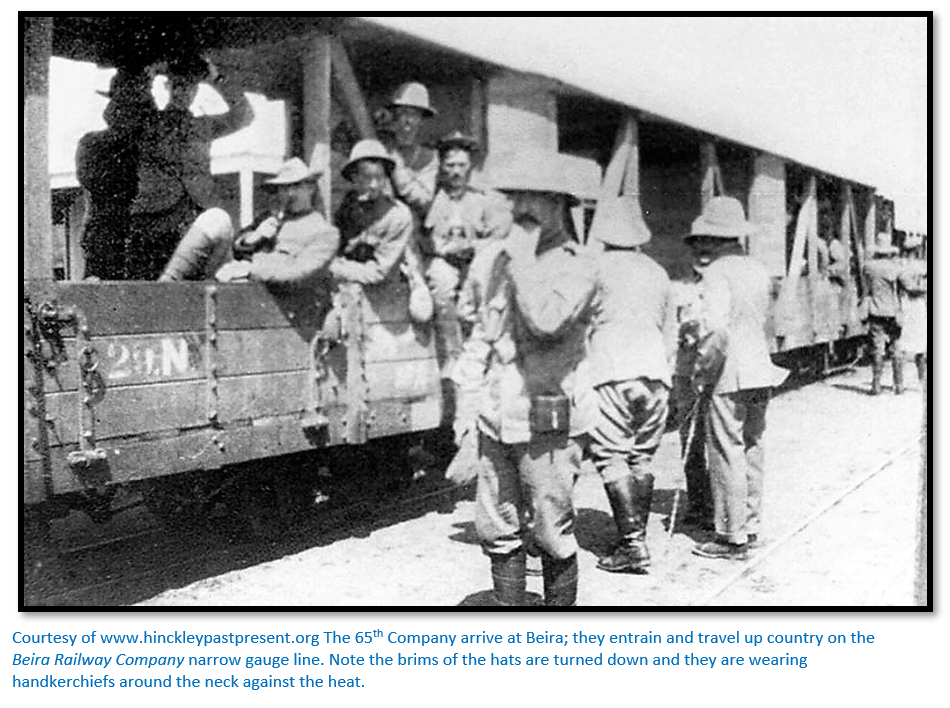

At the time the 65th entrained at Beira the railway was 2 ft narrow gauge as far as Bamboo Creek and then standard 3 ft 6 inch gauge to Marandellas. This entailed a change of trains and prolonged wait at Bamboo Creek during which time many members of the RFF contracted malaria, dysentery and enteric, a type of typhoid. Consequently some members of 17th and 18th Battalions were invalided directly home due to sickness before ever facing the enemy, and an unlucky number died of disease. In 65th Company these included 12071 Trooper J. Brooker who died on 9-Jun-1900 in the Umtali hospital of dysentery, and 12037 Quartermaster Sergeant W.T. Cockain who was evacuated back to England but died on 17-Dec-1900 of hepatitis.

Troopers in this first group of 65th Company served a full year in South Africa and returned to Britain in June 1901 on the Hawarden Castle. Their standard campaign medal clasp entitlement was Cape Colony, Rhodesia, Orange Free State, and South Africa 1901, but individual clasp entitlements did differ, depending on sickness, injury, death or transfer to other units once in South Africa.

Company numbers according to the medal roll were 6 officers, 1 Squadron Sergeant Major, 1 Squadron Quartermaster Sergeant, 1 Quartermaster Sergeant, 1 Farrier Sergeant, 1 Sergeant Trumpeter, 4 Sergeants, 3 Lance Sergeants, 5 Corporals, 6 Lance Corporals, 3 Shoeing Smiths, 1 Saddler, and 98 Troopers, some of whom were likely replacements since total unit size was 120 officers and men.

A second group of 65th Company soldiers was recruited in early 1901 to replace the first contingent in South Africa and was commanded by Captain H. P. Moulton-Barrett . They returned to Southampton aboard the ship Victorian in July 1902.

One of the members of the first group of 65th Company was 11991 Trooper Sharrad H. Gilbert. Gilbert recorded his impressions of the war and published them in 1901 in his book Rhodesia & After, Being the Story of the 17th and 18th Battalions of IY. This book is available for free electronically at Google books, and also as a reasonably priced paperback reprint from the Naval & Military Press.

Sharrad Gilbert: Rhodesia and after; being the story of the 17th and 18th Battalions of Imperial Yeomanry in South Africa

Gilbert wrote a collection of reports to the editor of The Hinckley Times and Bosworth Herald providing a personal commentary when the British public were awash with national pride and eager for news on the progress of the war.

The 7th Company was the first Leicester Battalion and was drawn primarily from existing members of Prince Albert’s Own Leicestershire Yeomanry Cavalry and the 65th Company, in which Gilbert was a Trooper, was the second unit of Imperial Yeomanry raised in Leicestershire. Initially commanded by Captain Walter A. Peake, recruitment for the 65th Company began on Wednesday, 21 February 1900 and was made up almost entirely of new recruits with little or no military background. The Leicester Mercury wrote War Office advertisements were placed in the local press for 115 men volunteers and in little over a week one hundred men had been accepted for service subject to passing the IY riding and shooting standards.

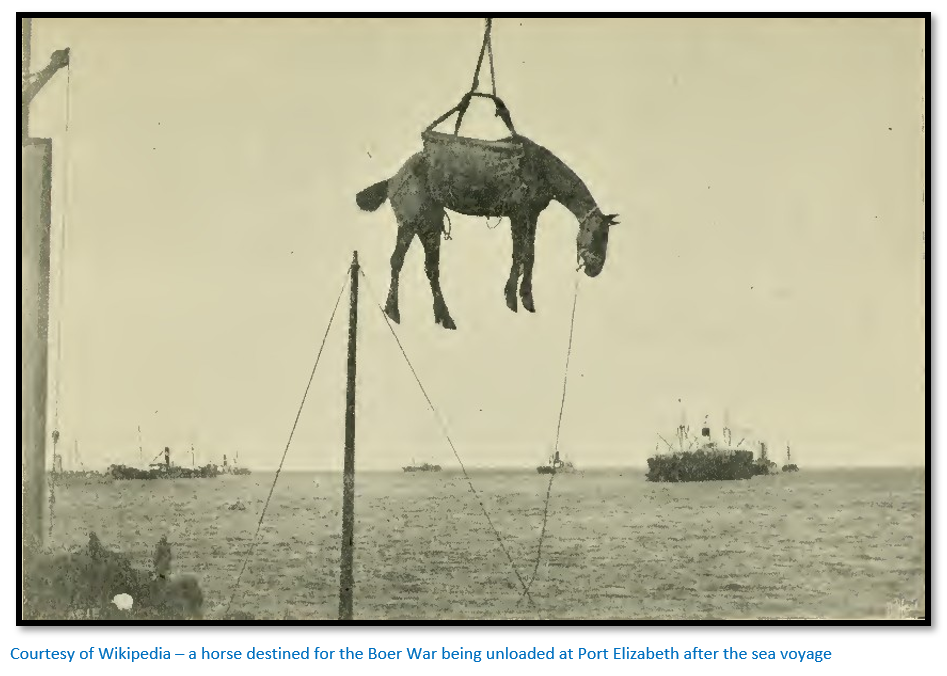

The 65th Company with seven other companies of the 17th and 18th Battalions IY sailed on 6 April 1900 from Southampton, calling briefly at Tenerife before sailing nonstop to Beira in Portuguese East Africa. In all, there were 63 officers, 1,019 men and 53 horses that sailed aboard the transport ship Galeka. They landed at Beira on the 4 / 5th May, joining with other volunteer mounted troops from Australia and New Zealand to form the Rhodesia Field Force under General Sir Frederick Carrington.

Arrival at Beira

On 4 May 1900 when Gilbert and his fellow soldiers arrived in the Galeka off Beira; the harbour had never held such an assemblage of ships…the Maori, the Waimate, the Monowai and the Cymric; all packed with khaki figures. Queenslanders, Victorians, New Zealand Rough Riders shouted their war cries as the ships passed and the 17th and 18th Battalions of the Imperial Yeomanry replied with hearty British cheers. However day after day went by as stores and horses were unloaded and only after waiting seven days did the paddle steamer Trevor came alongside and 65th Company of the 17th Battalion of IY set foot on African soil for the first time.

Gilbert writes that over to the West…’in the eye of the sunset, lies Rhodesia, with all the charms of a little known and undeveloped world.’ The myth of these charms was soon to be exploded as they boarded a troop train on the narrow gauge Beira – Salisbury railway. Each carriage was 16 ft by 5 ft and overhung the 2 ft gauge railway line; ‘a toy railway;’ overhead was a flat corrugated iron roof and timber boards at the ends, but the sides are open; they are pulled by two comical little locomotives made at the Falcon Works, Loughborough. Each carriage was filled with sixteen men in marching gear, thirty-two kit bags and three days’ rations for each man but compressing sixteen pairs of legs into this space is quite impossible, so soon there are dozens of pairs of legs clad in putties, boots and spurs dangling over the sides. The overwhelming sensation though is of a breathless, quivering heat.

Thirty-two Mile Creek

The engines all burn wood fuel so every few miles there is a plentiful heap of logs heaped up by the side of the line near a group of native huts. At 23 mile peg, christened Twenty-three Mile Creek, there is just a long siding, a water-tank for the locomotives and an iron bridge over the creek. The men unloaded their baggage and stores and scrambled up the bank to follow their officers for half-a-mile until they come across lines of small bell tents put up by the squadrons who preceded them. They pitched their tents and had a meal of corned beef and ship biscuit with hot coffee. Before sleep, each man has a quinine tablet. One of the few remaining buildings, for this was once a native kraal, serves as a guard house with one prisoner who woke up in the night to find: “three large light grey rats, one on his face, the other two sitting on his chest and contentedly trying to make a late supper off the buttons of his greatcoat.”

Because Portuguese East Africa was notorious for fever the men are given quinine daily and compelled to wear a sombrero during the day and a tam o’ shanter after sundown. Handkerchiefs are worn around the neck ‘to protect the spine’ and they were forbidden to sit on grass after the sun went down. But these precautions are in vain as severe diarrhoea affects the men.

At every hour of the day and night long trains, drawn or pushed by two or three engines and laden with men, horses and stores passed their camp on their way northwards. Often stores arrived in the middle of the night and they were ordered to shoulder the heavy boxes and stumble with them over the uneven ground in the darkness back to camp. Breakfast, dinner and tea was always bully beef and hard ship biscuit.

Sharrad Gilbert is clearly an amateur naturalist as he provides delightful descriptions of the jungle that surrounds them, the strange plants and insects and all the butterflies which are so unfamiliar to him. He befriends a large grey frog which finds its way under his stretcher…it has such a ‘without-a-friend-in-the-world’ kind of look that the soldiers let the frog stay a week before it left of its own accord without a farewell.

On 19 May the Colonel informed them of the Relief of Mafeking a few days before and all cheer and throw their hats in the air for Baden-Powell and his gallant men who had resisted Boer efforts for seven months. A few days later they were visited by Cecil Rhodes…Gilbert thought his face seemed lined with care.

On 20 May a company of New Zealanders and 100 horses stopped at their rail siding for a few minutes. They had food, but no water, so Gilbert and his companions filled their water bottles at the creek. The train had an engine at each end, but the driver of the rear engine was drunk and in an evil humour. A few miles down the line he unhitched his engine and the train was unable to move on for some hours.

On 22 May the sick were brought in stretchers from the camp and waited over three hours in the sun for a train. The train then collided with some wagons parked on a siding and some of the carriages derailed. The whole camp was marched to the siding in the darkness, the sick lifted out and the carriages pulled back onto the rails before the train left with its sick passengers.

On 23 May Gilbert and the Imperial Yeomanry were due to leave at 11:30am after their stay of twelve days. It was another hot day and there was no shade as all their tents were packed. The train only arrived in the evening and they left in a grain wagon – a box with an iron roof and large door which had to be kept open all the time to prevent them suffocating. They sat on their kitbags, no light, no food and no room to stretch legs. Someone started a singsong, but it died a natural death. At last at 12:30 the train stopped and they were told they had arrived at Bamboo Creek.

Bamboo Creek

They arrived in a heavy thunderstorm and only next morning saw their new camp. A large stretch of black-looking soil covered with rows of dirty-looking tents, bare hard trodden earth in the higher parts, soft and sticky earth in the hollows. The railway line in front was reached by crossing dikes and pits of smelling stagnant water with planks; at the back was coarse yellow shoulder-high grass except where it was burnt off. The right side had a vast horse paddock, the right was waste ground and the men had barely been in camp a day before they began to fall sick.

Each day those on parade grew smaller and the words ‘malarial fever’ which had just been a name, now became a reality. The two or three small hospital tents soon grew full and a fatigue party was kept busy constantly throwing water on their canvas sides to keep the interiors cool. The doctors were the hardest worked men in the camp as their duties continued day and night.

Soon the hospital tents were full and the sick men were forced to stay in their own tents…the fit stepping over their blanketed bodies. The fever removed any desire for food and their friends patiently helped them to eat small quantities. Fever often revealed itself when the men were on parade under the hot sun when the sick fainted. In one Yeomanry squadron only two out of the section of twenty-eight men remained fit for duty; each day in turn one served as tent orderly and the other fell in on parade – their sole section representative. The camp was becoming a vast hospital and as day followed day no orders came to move.

Fever was followed by acute diarrhoea and then dysentery. At the end of the camp was the Bamboo Creek cemetery. When the Imperial Yeomanry arrived it held four graves marked by white wooden crosses with black paint inscriptions - by the time they left three more graves had been added. Prior to their arrival large numbers of horses had died of blue tongue; the carcasses were not buried, just dragged by oxen into the surrounding grass away from the camp where they were fed on by the vultures. Army food was monotonous and unimaginative consisting of bully beef and hard ships’ biscuit every day of the week accompanied by tea or coffee; the men supplemented their diet with tins of condensed milk and jam when they could be purchased.

Bamboo Creek at the time was the terminus for the narrow gauge; to the west the 3 ft 6 inch standard gauge continued toward Umtali. [For an in-depth account read the article The Beira and Mashonaland Railway – the Contractor’s Stories under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] The station and telegraph offices consisted of iron buildings with veranda’s dominated by groves of banana trees. Everywhere hundreds of natives were busy unloading stores from the narrow gauge and onto the carriages of the standard gauge. The Bamboo Creek Hotel was within their bounds, but a sentry prevented the troops visiting the Portuguese settlement.

The Hotel’s large matchwood boarded bar-room had a long counter, backed by the usual bar-room shelves and a glittering array of coloured bottles and flasks. The clink of glasses mixed with the hum of scores of conversations, a shifting population consisted of slouch-hatted, shirt-sleeved, booted and spurred and picturesquely dressed men with brown faces and sun-scorched arms. At the far end the click of billiard balls; everything seen through the smoke of bad shilling cigars and black cake tobacco. Behind the bar the sallow faces and broken English of the attendants and every few seconds the crash of a broken bottle as it was flung through the open window out the back of the bar to join the dozens that have gone before. Many soldiers enjoyed their first square meal since they left home of antelope meat or boar’s head in the dining room.

The orders to move came suddenly and by Sunday midday their kit-bags and bedding were packed and they waited in blue deck uniforms to save the khaki from the sparks of the locomotive. The hours rolled by, the men unpacked their blankets and lay down to sleep. The train arrived the following midday. Eight horse boxes – seven of them filled with horses for the Rhodesian Artillery and one open wagon. The sick were put in the empty horse box, the rest packed into the open wagon, but there was room only for “A” squadron and the remaining three squadrons had to wait. So on 28 May 1900 Gilbert along with forty-two other soldiers, many sick with fever and dysentery, left the fever pit of Bamboo Creek on a journey to Umtali which would take two days and a night.

Many weeks after he says he came across the following written shakily in pencil upon the walls of a Rhodesian Hospital: “Bamboo Creek, the white man’s grave.” He continues: “It was only the work of an idle moment, scrawled by some unfortunate when the fever had left him strength and the power to think. But for the truth of it let the little row of graves in the cemetery at Bamboo Creek bear witness; for the bitter proof of it go to the Umtali graveyard to the last resting place of the score of British and Colonial soldiers who lie there. To its fever-laden flats we owe the teeming hospitals of Umtali and Marandellas. Of Umtali where ninety men were crowded into a building intended to hold fifty; of Marandellas where in addition to the iron hospital of nearly forty beds, fifty large huts of mud and thatch had to be built to cope with the incoming sick. Many a man who saw his name among the pitiful list of those invalided home owes to Bamboo Creek his shattered health and the wreck of bright hopes with which he left his country and his home.”

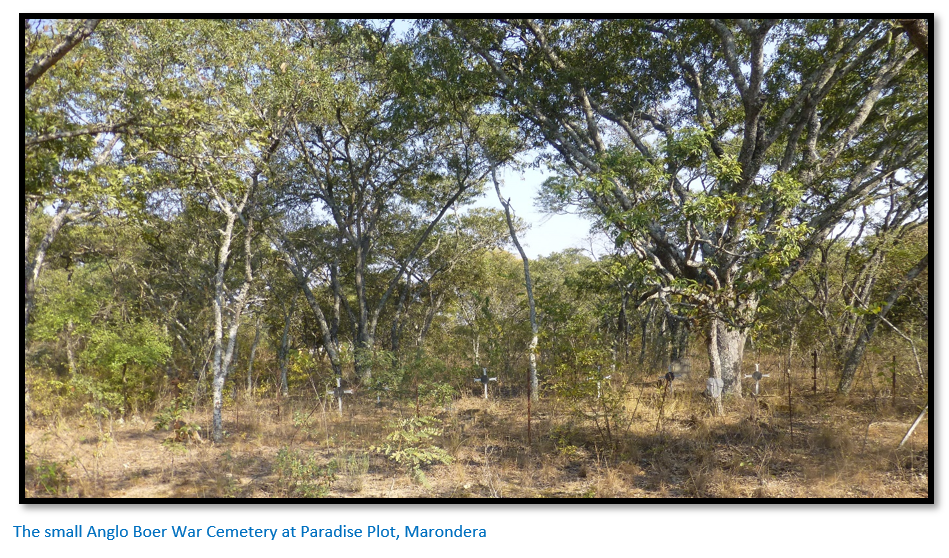

[An article on the Anglo Boer War graves at Paradise Plot, Marondera can be found under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

The train journey to Umtali

They travelled mile upon mile of jungle through the Amatongas Forest with occasional small forest clearings, then a bushfire whose flames licked at the side of the railway line, their eyes and noses filled with its pungent smoke until their engine pulled them with a rush into the pure air of the forest. At Amatongas station where logs are thrown onto the engine-tender there was time to make tea with boiling water from the engine and arrowroot for the sick as they were watched over by the yellow face of a fever-stricken Portuguese station master.

Then off they went into the night wrapped in their cloaks against the chill of the African night; the gradients are severe and as the engine climbs great fiery sparks fly past or in amongst them. So the long weary night passes with many halts to replenish the wood and water and a long wait in a siding for a down train to pass.

At last breakfast at Chimoio…the men hang their legs over the sides of the carriages below their sunburnt faces, unwashed since the previous day. In one hand, an enamel mug of muddy-looking coffee and in the other a square of ships’ biscuit covered in Crosse and Blackwell’s strawberry jam. They are now through the tsetse-fly belt at 1,280 metres (4,200 feet) and pass large paddocks filled with horses being watched over by their Australian comrades.

From Chimoio the railway line descends into the Revue River Valley where they halted for water before commencing the climb up the Munene River Valley into Macequece, now Manica. Here they read a copy of the Manica Mining Journal and learned it has been a bad season for malaria and lions. Four lions had killed five oxen a few days before belonging to a Mr Ribeiro, a lion hunt had been organised in which most of the town’s menfolk were involved, but without result, and to add insult to injury a further ox had been killed by the lions the next day.

After Macequece the gradients become steeper, the railway line making great snake-like curves as it curves between the hills and the speed slackens to a walking pace and even halts at times until greater steam pressure is built up; conversely, on the downgrades the train makes up for lost time. For the men with their legs stretched over the sides of the carriages the views become more magnificent as they climb higher and cross numerous streams over rickety-looking bridges. Along the line of the rail they can see great lengths of the old narrow gauge line which has been torn up and flung into the long grass alongside. At last they reach Umtali, now Mutare.

Goldfields Hospital, Umtali

On 11 August 1897 the last meeting of the Sanitary Board in Old Umtali was held and by the end of the year Bishop Hartzell conducted the first Methodist service. The majority of residents had moved to the present site of Umtali, now Mutare in time for the arrival of the first train on 4 February 1898.

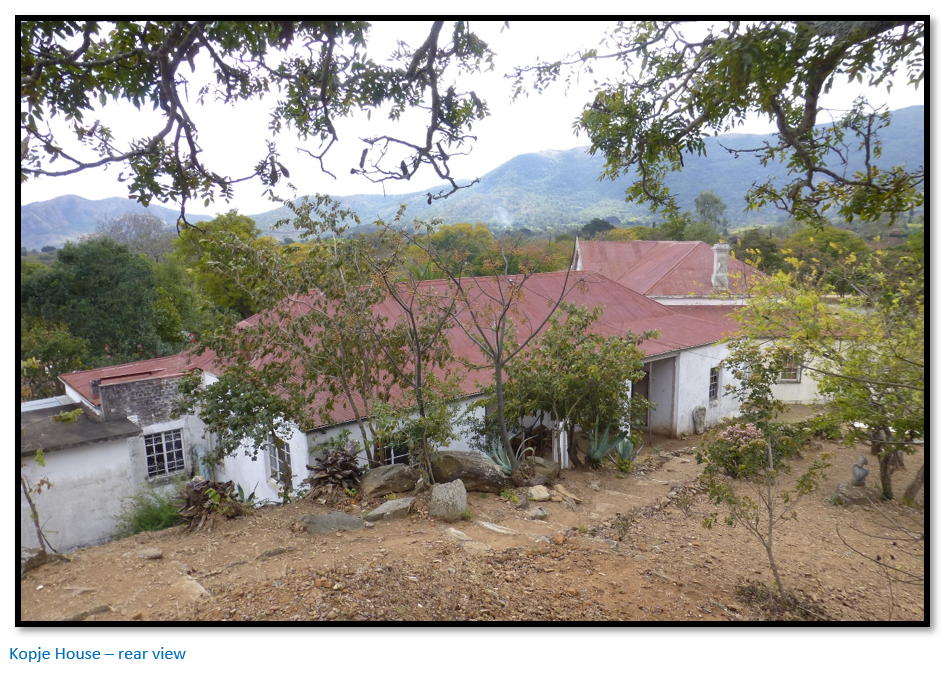

The name of Goldfields refers to the hotel which was established very briefly on the site before being taken by the military. Dr Morris states the first written reference to the site is by Lt-Col E.A.H. Alderson who was in a party in 1896 which: “inspected the site of the proposed new hospital.” Gilbert was clearly a patient as he says Ward 3 still had a large semi-circular mahogany bar and that only teetotal patients slept here as they wouldn’t be likely to rise from their beds and rap the counter in an absent-minded fit! Its name Kopje House reminds us that most of the earliest patients were suffering from malaria and blackwater fever and the small prominence upon which it is sited provided a cooling breeze.

Kopje House between 10th and 11th Avenue on Third Street served as Umtali’s only hospital from 1897 to 1930 and according to Dr R.M. Morris the layout in 1928 was substantially the same as today except for slight modifications in its later functions as school hostel, Aged Person’s Home, Government Office, annexe of the Mutare Museum and now Mutare National Gallery. [See the article on Mutare National Gallery under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Gilbert recalled the heavy feet of the hospital orderly as he walked up the four rickety wooden steps of the ‘annex’ and said after he opened the door: “Six o’clock. Time to get up.” The sleepers growled and pulled the blankets closer around them. “Shut that door for Gawd’s sake. Can you get me a drink? I’m as thirsty as a fish.” The orderly would reply as he went back down the stairs: “See what I can do.”

This was followed by the soft voice of the sister giving instructions to an orderly from the courtyard. Then the door would be hesitantly pushed open and ‘Bokus’ would come in to sweep the centre of the room and under each bed; a process to be repeated four times a day. The orderly brings around breakfast: “Hmm” consulting his cards: “two full’s and one low.” The full comprises a huge plate of porridge covered in sugar and swimming in milk, large slices of bread and jam and tea. The menu of the unfortunate “lows” whose fever needs starving get: 5am – arrowroot; 8am – cocoa; 11am – soup; 1pm – sago; 3:30pm – milk or arrowroot; 5:30pm – cocoa; 8pm – milk or soup; 12pm – cocoa or hot milk.

The staff included three doctors and four sisters – Australian ladies who have volunteered for the RFF, a few R.A.M.C. men and orderlies were lent by the different squadrons passing through.

Patients from the wards came in to talk. Everything is done in leisurely fashion as there is nothing to do but eat and grow well and regain strength. The one newspaper is shared, a single pink sheet 17.5 inches by 11 inches, printed on one side only. The title takes up 3 inches, the remainder divided into four columns with three columns of advertisements and the fourth carries a report of the hospital bazaar and a polo match. Nothing about the war. Price 3 pence.

On the 12 June 1900 as Gilbert noticed a screen around a bed and the orderly stated: “Yes, Trooper McCann has just gone.” Tomorrow he will be drawn in a creaking wagon with black oxen to the cemetery and laid to rest to the sound of a rifle volley and the bugle playing “Last Post.” That day three other soldiers passed away (Blackden H.C.W; Bloomfield J.B and Stone J)

So many arrive sick from Bamboo Creek with Gilbert on the 1 June that the doctors are at their wits’ end and the less-ill patients are moved into tents to make beds available in the wards. He says the prescription for those with malaria is quinine three times a day and no food… not very conducive to jollity.

At the end of this chapter Gilbert adds thanks for the single-hearted and unselfish kindness of the people in Umtali:

- The Civil Commissioner who entertained them at the Residency,

- Mrs Myburgh and the ladies of Umtali who provided eggs, fowls, milk and fruit,

- The people of Umtali who donated their whole milk supply to the hospital,

- To the Clubs which gave literature,

- To the volunteer Australian nurses who provided cheerful cheer and skilful nursing.

The Base Camp at Marandellas

Before it became the Base Camp of the Rhodesian Field Force Marandellas was a small station on the Beira – Salisbury line with the usual water-tank and hotel-store. By 1900 it was full of military activity; the detraining of horses and guns, ammunition and men with mountains of forage and stores stretching several miles to the west with Headquarters at one end and the Hospital at the other.

On the eastern edge were the Police barracks – the white troopers in small tin houses and the native police in pole and dhaka huts with their families. Their uniforms consisted of a dark blue tunic and black leather belt, brown corduroy trousers with black stripe, scarlet field service cap and bare legs and feet. Nearby was the Post Office, a square mud plastered hut with the military press censor, a lieutenant, in an adjoining hut, who signed off Gilbert’s letter without a glance at it. Then came the Maitland Camp for staff offices, after which were the grass-green tents of the Colonials, consisting of the Victorian Bushmen, the New Zealand Rough Riders and the Tasmanians. Then the rows and rows of white bell tents of the Imperial Yeomanry with horse lines in-between. At the western end were whole streets of iron sheds and warehouses and then the hospital with rows of huts for the overflow of patients. Most westerly of all the small cemetery at Paradise Plot – those buried here are listed in the table of casualties below.

The water supply came from the creek from where it was pumped by a steam vertical engine administered by an Australian trooper with pipes leading to the horse troughs in which a thousand horses could be watered and also into rows of corrugated zinc cisterns in the centre of the camp for the soldiers’ use.

The fine ankle-deep dust was remembered well by Gilbert who was for some weeks served as the cyclist orderly to the Headquarters Staff and whose BSAP bicycle was built high to spare the pedals from rocks and stumps; it weighed as much as he could carry and was hard work to pedal.

At Marandellas the Imperial Yeomanry were issued horses – principally from Texas and Hungary and although they proved tough and hardy there was significant horse sickness in the camp; 15 - 20 horses were being shot each day and their carcasses dumped in the veld a mile or more to the north of the camp.

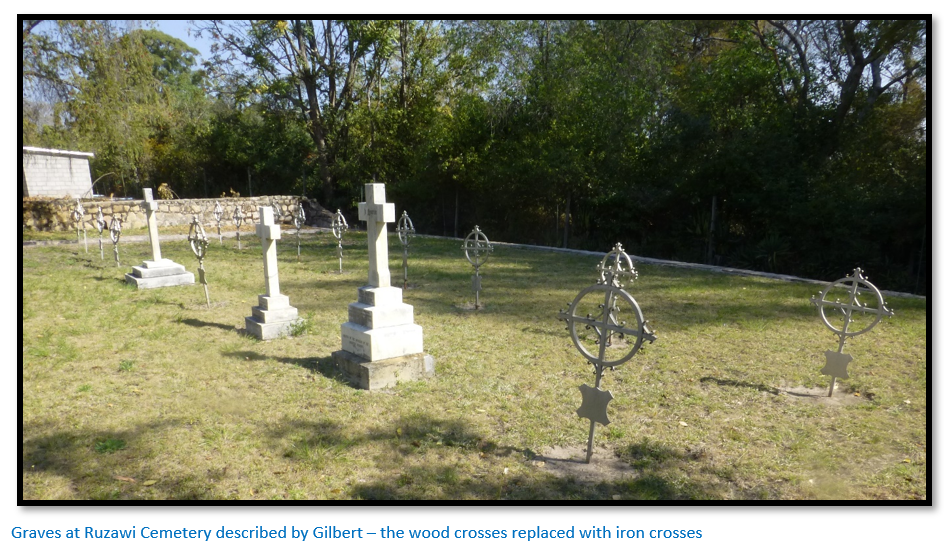

To the south of the camp were the characteristic stony kopjes of Mashonaland where Gilbert explored the caves and terraces and rough fortifications of “Gatzi’s kraal” which had been determinedly held during the Mashona Rebellion or First Chimurenga. At the site of present-day Ruzawi School was the small cemetery with its three marble memorials and roughly carved wooden crosses [See the article Mashona Rebellion / First Chimurenga 1896-7 graves at Old Marandellas (Ruzawi Cemetery) under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Daily trains steamed in from the Beira with military stores and guns, men and horses. The sound of the forge and shoeing of horses was heard from morning until night.

Every few days a squadron of horsemen, fully equipped, with their stores loaded upon mules and ox-wagons would parade for a final inspection and then head off towards Charter – some bound for Tuli via Victoria, others for Bulawayo to the envy of those remaining who looked forward to the day they would be ‘ordered south.’

1901 Mapondera Rebellion

Chief Mapondera was considered an outlaw by local Europeans and in seeking to apprehend him at his kraal a BSAP patrol under Capt. Munroe came under fire suffering a loss of one of his NCO’s, Sgt John. Munroe returned to Sinoia, now Chinhoyi and telegraphed Lieut-Col Flint, then commander of the Mashonaland Division of the BSAP who was informed that other kraals were helping Mapondera with men and grain.

A mixed expedition was hastily put together comprised of European and African BSAP and one squadron of the 65th Imperial Yeomanry, now part of the Rhodesia Field Force and on 28 June 1901 their train loaded with horses and stores left Marandellas for Salisbury. After two weeks rough trekking with wagons they made camp at Sipolilo, now Guruve 140 km north of Salisbury. Gilbert complained the nights were cold and with the ox-wagons trailing behind they had no blankets; the rations went bad and needed to be supplemented with game meat.

A great indaba was held at Sipolilo which many of the surrounding Chiefs and Headmen of kraals attended; Lieut-Col Flint’s words were translated into the local Shona dialect…he replaced Chief Mapondera with Chief Sipolilo as Paramount Chief on the promise that he would promote peace rather than insurrection.

Soon they were trekking on foot…a single line along bush paths that stretched for three miles towards Mapondera kraal, although one troop has been detached to cut off any retreat northward. At 2am they halted for two hours before moving on again. Four hours later it is too late for a surprise attack; the guides had miscalculated the distance. They advanced for another hour and suddenly heard the sound of firing echoing in the hills.

The detachment troop after leaving Sipolilo at dawn had made heavy going through rough country with few paths to follow and little water. Next day they descended the Zambesi Escarpment to the Dande River and here on one of the bends lay Mapondera’s stronghold. They lay waiting for the main column to initiate the assault but were discovered by a child of one of Mapondera’s wives who ran away screaming. The mother and child raised the alarm and the soldiers were only just in time to fire a volley as Mapondera’s followers scrambled up the hillside returning fire with their flintlock smoothbore guns.

Two hours later the detachment troop and main body were united, but the birds had flown leaving just a few goats at the kraal which were eaten for lunch. Mapondera’s men then crept back taking advantage of poor sentries and fired on the soldiers again before taking to the hills once more. The bodies of five tribesmen were found and many of the women and children captured along with livestock and grain.

Gilbert states it was easy to see where Mapondera’s men were hiding as their muskets emitted great clouds of gunpowder smoke. The caves were searched for grain bins, camp was made near the scene of the engagement and patrols sent out; another small engagement as Mapondera retreated east resulted in two more tribesman being killed and further dependants being captured. This was no significant victory, but the threat posed by Mapondera in provoking a new uprising was significantly reduced.

Back at Sipolilo, Gilbert witnessed a great ‘Victory’ feast attended by many local tribesman at which the singing and dancing make a great impression on him.

Return to Marandellas

The soldiers returned from Salisbury to their camp at Marandellas which has diminished considerably in their absence with only three squadrons of Bushmen and themselves left. After two weeks of rumours and counter-rumours their orders arrive and they leave at 4am next day. However the speed of the force of five officers and over a hundred men with two Maxim guns and limbers is dictated by the slow pace of the five mule wagons and three ox-wagons.

Their marching routine is to rise at dawn and ride until 9 – 10am and halt at a stream or shady spot where the horses, mules and oxen are turned out to graze before a further short trek in the afternoon. They marvel at the changing colours of the Msasa woodland from every shade of tender green to vivid Indian red, the plains of undulating grasses and those blackened patches where the tender green shoots of new grasses are showing through.

Their wagons only carry forage and stores for part of their journey so after passing through Charter they reach ‘The Range’ a large Government depot on 1 September where they can replenish stores [I believe this is ‘Old Wiltshire Headquarters] and arrive at Enkeldoorn, now Chivhu the same night. At the time the town had a single street lined with young trees, a few brick stores, a hospital and red-brick Dutch Church, the Post Office built of sun-dried bricks in which the clerks lived with the bleached skull of a hippo at the door. The police camp is where it is located today, just to the south of the town.

Two days later they crossed the Sebakwe River [probably at Orton’s Drift – [see the article under Midlands on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] and passed from Mashonaland into Manicaland. Gilbert mentions that as well as the drift there was a ferryboat here drawn across by a wheel hung from a cable.

This being the main Salisbury – Bulawayo road they were passed every other day by the Zeederberg coaches piled with passengers and baggage and drawn at a fast trot by eight small grey mules. They looked far too clumsy to negotiate the small spruits but completed the 450 km (280 miles) in three-and-a-half days. The mules were changed every 19 km or so (12 miles) at coaching stations which were just rough wooden sheds with a corral and some huts, the mules grazed on the veldt until a coach was nearly due when they were corralled.

Just before Gwelo they came across a river with banks 9 metres high (30 feet) and Gilbert watched as the wagons negotiated the steep sloping track down to the stream and then up again on the other side. The mule wagons crossed one at a time; a sharp crack from the driver’s whip and the ten mules bounded forward. Down they went at a run and splashed into the shallow stream, the wheels bumping against the rocks and then up the steep bank wet and slippery from the feet of the teams that went before. A rear wheel catches behind a rock; the driver urges the mules forward…surely the wagon must move or the harness break. Slowly the wheel grinds slowly over the obstacle and moves up the hill foot by foot, the whips crack and the driver urges the mules on until they reach level ground.

Gwelo, now Gweru

The town was made up of tin buildings and brick shops scattered rather haphazardly on the stands with wide streets bordered by ditches and pepper trees. There were general stores and bottle stores, a Post Office and Stock Exchange and some fancy hotels. African Police in white trousers and helmets with khaki tunics patrolled the streets carrying large knobkerries. Tall thin sun-burnt European men lounged at the front of the hotels talking business and smoking large cigars. Young boys on bicycles took short-cuts across the unbuilt-on stands. The news shop displays newspapers a month old and near the two chemists is the office of The Gwelo Times.

Their camp is in a grove of trees half-a-mile from town and infested with white-ants. Saddles and webbing have to be kept off the ground or be eaten; scorpions are a problem too. They encounter swarms of locusts which cover every branch and leave each long grass stalk with its swinging burden. The shrill noise of the cicadas which goes on for hours drives everyone away unless they can be found; not easy as they are well camouflaged, and then squashed.

Gilbert adopts a chameleon and describes its antics for over three pages, even training it to ride on his shoulder until one day after a gallop he finds it has fallen off.

He describes the advantages and disadvantages of mules versus oxen. The mule requires 10 lbs of oats each day, so for a ten day journey with ten mules 1,000 lbs of oats must be carried; whereas oxen simply graze off the veld. So oxen can carry a heavier load but are slower.

Several times between Gwelo and Bulawayo they crossed the track bed of the future railway, but no rails had yet been laid.

Near Thabas Induna, now Ntabazinduna they camped on the banks on the Umguza River whilst the horses were inoculated against Glanders. The following day there is an inspection of the Rhodesia Field Force by their Commander General Sir Frederick Carrington and on 26 September they marched into Bulawayo.

Bulawayo

Gilbert was feeling jovial when he wrote his article on Bulawayo. “Bulawayo may become a Chicago, though it is doubtful; yet it is evidently laid out with that end in view. There are miles of streets and sidewalks to be kept in repair…it would be a great relief to the groaning ratepayers if the town was squeezed into a third of its present size.” Later in describing the Park…”Through the whole length of the Park winds the Matsheumhlope River, or perhaps I should say river-bed, for there was no water in it at the time that I saw it. The Matsheumhlope is not a large river – one can easily jump it without having the limbs of an athlete, but the mouth of a music-hall comic is absolutely necessary, I should say, in order to pronounce it.”

And practically every Bulawayan was a cyclist…every man, woman and child owned a bicycle. Oliver Ransford in Rulers of Rhodesia says that even General Carrington learned to ride a bicycle in Bulawayo!

For the Imperial Yeomanry Bulawayo meant a release from the bully beef and biscuit they had lived on for the past month. They rode past the cafes and stores and hotels and over the railway line and then three miles through thin thorn scrub to the long low white huts of the Hillside Barracks which would be their home for the next six weeks. The barracks were a double row of long huts around three sides of an immense square; built of wooden boards with tin roofs and earth floors, they were infested by rats.

There was no drill; their duties mostly comprised guard duties at their Barracks, the Agricultural Hall, the Magazine and the Railway Station. Morale took rather a hit as they believed they might not see any active soldiering; they had come to be soldiers not stable-lads and so they sang the song of the 65th Company:

“Grooming, Grooming, Grooming,

Always blooming well grooming,

From Reveille to Lights Out,

We’re grooming all the day.”

Horses were taken out with the soldiers riding one and leading two for a trot around the Bulawayo racecourse. Beer could be purchased at the canteen for 6d a glass; there was also a dry canteen and an Australian Café which sold steak and eggs. Near the guard-room were long stretches of hospital tents for those with illnesses that included enteric, typhoid, malaria and dysentery.

During their stay the seasons changed…first blinding dust storms followed by thunderstorms which peeled off the rough plaster of the huts and turned the parade ground and surrounding veldt into shallow lakes. At the same time they received orders to move and the squadron left by rail for South Africa.

After in South Africa

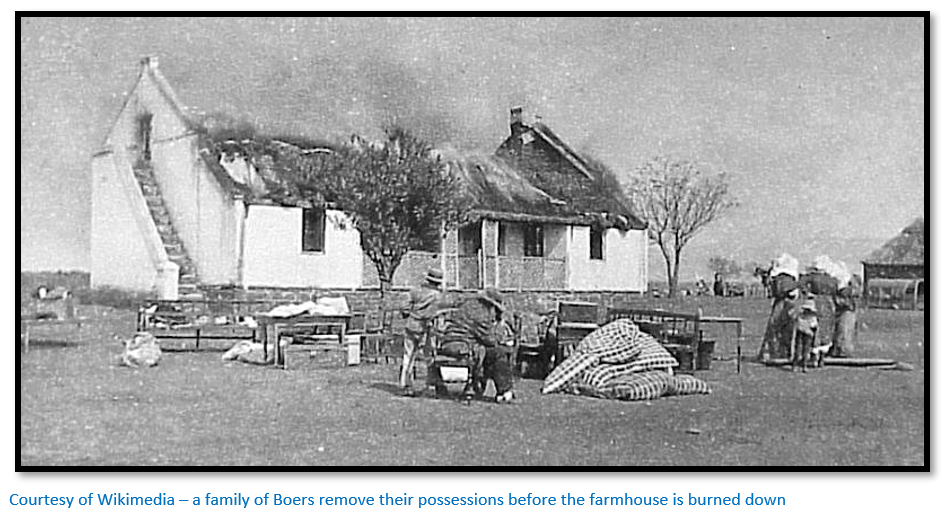

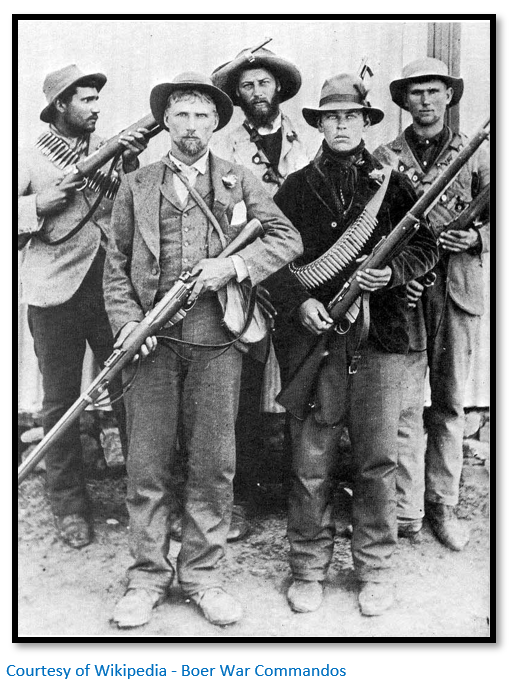

In the remaining nine months the 65th Company of the Leicester’s were in South Africa they had to undergo diverse tasks including guarding the drifts on the Orange River, guarding convoys of supplies and carrying out countless patrols in search of the Boers. This entailed long days in the saddle under a scorching sun as the Boers were skilled in a commando type of warfare and often the pursuing troops were days behind their quarry. On one fruitless chase of General Herzog they were on the chase for fifteen days and through lack of forage and hardship lost four hundred horses and mules. When they were tired after days of pursuit and let their guard down they might be ambushed or caught in the open and sniped at from a range of kopjes 1,000 metres distant. At other times they were tasked with burning down lonely Boer farmsteads to deprive the commandos of supplies.

Outside Aberdeen in the Eastern Cape Sharrad suffered the humiliation of being captured by the Boers. Their patrol was ambushed by 250 – 300 Boers under their commandant Scheepers and Sharrad was pinned down by fire and surrounded by the Boers and forced to surrender. The British troopers had to walk under armed escort after discarding the bolts of their rifles to render them useless and being relieved of their horses and water bottles and bandoliers. Scheepers himself was dressed in a neat navy blue suit with two bandoliers crossed over his body. They all spoke English and were from the Cape.

Some hours later the party of Boers and prisoners were shelled British howitzers with their 50 lb lyddite shells. They all scrambled up and over rocky ridges for several miles and as they splashed through a spruit Sharrad turned aside and hid under some thorn undergrowth. He was missed and the Boers came back searching for him but just as he thought he would be recaptured they heard artillery fire and thinking their retreat might be cut off, they turned their horses around and left.

He had several close escapes including when two Boers on horses were just sixty yards away and another when a Boer horseman was just ten yards away as Gilbert lay silent on the ground under his khaki greatcoat. Eventually, he was spotted by another British patrol but not before he had survived an awkward moment with an ostrich defending its territory!

| Rhodesian Field Force (RFF) grave locations and numbers | No. | Name | Unit | Rank | Date | Reason | ||||

| Twenty-three Mile Creek | 11288 | Flude C. | 61st South Irish I.Y. | Tpr | wounded | 18/05/1900 | Gunshot wound | |||

| Bamboo Creek, PEA | 1 | 12468 | Apps E.R. | 67th (Sharpshooters) I.Y. | Tpr | died | 29/05/1900 | Dysentery / Malaria | ||

| 1 | 12037 | Cockain W.T. | 65th Leicestershire I.Y. | Q.M. Sgt | died | 17/12/1900 | Hepatitis | |||

| 1 | 12449 | Shaw G.F. | 67th (Sharpshooters) I.Y. | Tpr | died | 29/05/1900 | Enteric | |||

| 1 | 12006 | Stevenson C ** | 65th Leicestershire I.Y. | Tpr | died | 20/07/1901 | Enteric | |||

| Umtali (Mutare) | 1 | 4684 | Blackden H.C.W. | 50th Hampshire I.Y. | Tpr | died | 12/06/1900 | Dysentery | ||

| 1 | 4693 | Bloomfield J.B. | 50th Hampshire I.Y. | Tpr | died | 12/06/1900 | Fever | |||

| 1 | 384 | Brent H. | Victoria, 3rd Bushmen's Contingent | Sgt | died | 14/05/1900 | Railway accident | |||

| 1 | 12071 | Brooker J.R. | 65th Leicestershire I.Y. | Tpr | died | 09/06/1900 | Dysentery | |||

| 1 | 4697 | Burden F.H. | 50th Hampshire I.Y. | Tpr | died | 16/06/1900 | Dysentery / Malaria | |||

| 1 | 12469 | Dunne A.J. | 67th (Sharpshooters) I.Y. | Tpr | died | 24/06/1900 | Dysentery | |||

| 1 | 367 | Foster T.B. | Victoria, 4th Imperial Contingent | Pte | died | 22/08/1900 | Enteric | |||

| 1 | 11262 | Franklin D.C. | 61st South Irish I.Y. | Tpr | died | 05/06/1900 | Dysentery / Malaria | |||

| 1 | 12710 | Hinton J. | 71st (Sharpshooters) I.Y. | Tpr | died | 10/06/1900 | Dysentery | |||

| 1 | 11300 | McCann J.M. | 61st South Irish I.Y. | Tpr | died | 12/06/1900 | Dysentery | |||

| 1 | 11088 | McCarron D. | 60th North Irish I.Y. | Saddler | died | 05/06/1900 | Dysentery / Malaria | |||

| 1 | 1125 | McIntosh D.F. | New Zealand, 4th Contingent | Pte | died | 05/07/1900 | Dysentery | |||

| 1 | 46 | Myers W. | New South Wales Contingent | Sgt | died | 25/04/1900 | Railway accident | |||

| 1 | 12738 | Pugh A.J. | 71st (Sharpshooters) I.Y. | Tpr | died | 08/06/1900 | Malaria | |||

| 1 | 11289 | Stone J. | 61st South Irish I.Y. | Tpr | died | 12/06/1900 | Dysentery | |||

| 1 | 584 | Swan J.C. | Victoria 3rd Bushmen's Contingent | Pte | died | 26/05/1900 | Malaria | |||

| Marandellas (Marondera) | 1 | 11254 | Armstrong T.G.B. | 61st South Irish I.Y. | Tpr | died | 07/08/1900 | Meningitis | ||

| 1 | 4710 | Davis S.E. | 50th Hampshire I.Y. | Tpr | died | 26/07/1900 | Blood poisoning | |||

| 1 | Hamilton H.C.W. | Queensland 1st Mounted Infantry Contingent | Capt | died | 12/07/1900 | Dysentery | ||||

| 1 | 418 | Kiley J. | Victoria 4th Imperial Contingent | Pte | died | 13/10/1900 | Pneumonia | |||

| 12034 | Lapham R.A. | 65th Leicestershire I.Y. | Pte | wounded | --/06/1901 | accidently wounded | ||||

| 1 | 1335 | Saxon F. | New Zealand, 4th Contingent | Pte | died | 19/06/1900 | Malaria | |||

| 1 | 15507 | Shaw A.E. | 75th (Sharpshooters) I.Y. | Tpr | died | 07/06/1900 | Malaria | |||

| 1 | - | Stevens G.W.N. | Rhodesia Regiment | Pte | died | 29/07/1900 | Exposure | |||

| Salisbury (Harare) | 1 | H. Andrew | 70th (Sharpshooters) I.Y. | Lieut. | died | 09/07/1900 | Dysentery | |||

| Enkeldoorn (Chivhu) | 1 | 11084 | Austin T. | 60th North Irish I.Y. | Tpr | died | 24/08/1900 | Dysentery | ||

| 1 | 440 | Kelly R. | New South Wales Imperial Bushmen | Sgt | died | 03/07/1900 | Malaria | |||

| Iron Mine Hill | 1 | 275 | Walton J.N. | New South Wales Contingent | Q.M. Sgt | died | 21/05/1900 | Influenza | ||

| Bulawayo | 1 | 75 | Hambly E.A. | West Australia, 3rd Bushmen's Contingent | Pte | died | 26/06/1900 | Malaria | ||

| 1 | - | Hines F.E. | Army Nursing Service | Sister | died | 07/08/1900 | Influenza | |||

| 1 | 12784 | Lloyd A.V. | 71st (Sharpshooters) I.Y. | Tpr | died | 28/12/1900 | Enteric | |||

| 1 | 67 | McPhee W.J. | West Australia, 3rd Bushmen's Contingent | Pte | died | 02/07/1900 | Influenza | |||

| 1 | - | Millar T.M. | - | - | died | - | - | |||

| 1 | 11190 | Ringwood V. | 61st South Irish | Pte | died | 09/02/1901 | Enteric | |||

| Mapondera's kraal | 12049 | David W. | 65th Leicestershire I.Y. | Tpr | wounded | 16/07/1901 | Gunshot wound | |||

| 12069 | Gittins A. | 65th Leicestershire I.Y. | Tpr | wounded | 16/07/1901 | Gunshot wound | ||||

| 12047 | Munn H.T. | 65th Leicestershire I.Y. | Sgt | wounded | 16/07/1901 | Gunshot wound | ||||

| Gwanda | 1 | 11242 | F.J. Madden | 61st South Irish | Tpr | died | 18/10/1900 | Pneumonia | ||

| Fort Victoria (Masvingo) | 1 | 12580 | Grey B. | 70th (Sharpshooters) I.Y. | Tpr | died | 15/10/1900 | Enteric | ||

| 1 | 12498 | Olney C. | 67th (Sharpshooters) I.Y. | Tpr | died | 28/10/1900 | Enteric | |||

| 1 | 12793 | Peck W.S. | 71st (Sharpshooters) I.Y. | Tpr | died | 25/10/1900 | Enteric | |||

| Tuli | 1 | 12612 | P.B. Russell | 70th (Sharpshooters) I.Y. | Tpr | died | 03/12/1900 | Enteric | ||

| Number of RFF graves in Zimbabwe | 42 | |||||||||

| ** Evacuated back to England and died there | ||||||||||

Campaign for memorial headstone for Sharrad Golbert

Much of the following information was collected by a local Hinckley historian, Greg Drozdz, who campaigned fifty-six years after Gilbert’s death for a memorial headstone over his unmarked grave. He and The Burbage Heritage Group knew that Gilbert was one of Hinckley’s most decorated soldiers, having served in both the Boer War and the First World War, paraded before royalty and accumulated a total of 35 years of military service.

When the Boer War was declared on 11 October 1899 Gilbert applied to serve abroad with the Leicestershire regiment, but despite his 13 years’ service with the volunteers, he was initially turned down, before reapplying and being enlisted in the 65th Squadron (Leicestershire) 17th Battalion Imperial Yeomanry.

During the fifteen months in Rhodesia and South Africa during which he saw much action and was in fact captured by the Boers at Aberdeen in the Eastern Cape. However, he managed to escape.

On his return Sharrad home with another Hinckley man, Dudley Beaumont Atkins, they were met by a large patriotic crowd at Hinckley railway station and ferried to the Union Hotel in an open carriage where the town band played “Hail the Conquering Hero Comes.” The Hinckley volunteers were each presented with a gold watch and a scroll and a Boer War memorial tablet with all their names was placed in the entrance to the Council offices, then in Station Road, but now on display at Hinckley and District Museum.

Sharrad was awarded the Queen’s South African medal with clasps for South Africa, Orange Free State, Rhodesia and Cape Colony and had the honour of receiving this from Edward, Prince of Wales, in a Whitehall parade.

His seven medals comprise:

- Queen's South Africa Medal with 4 clasps: South Africa, Orange Free State, Rhodesia, Cape Colony 1901

- British War Medal (Great War of 1914-1918)

- Victory Medal (Great War of 1914-1918)

- Territorial Force War Medal (Great War of 1914-1918)

- King Edward VII Coronation 1902 Medal

- Meritorious Service Medal (for non-commissioned officers)

- Volunteer Long Service & Good Conduct Medal

Sharrad gathered together his notes he had made during his time on the veldt and his articles from The Hinckley Times and Bosworth Herald and had them published in a book; Rhodesia and after; being the story of the 17th and 18th Battalions of Imperial Yeomanry in South Africa upon which this article is based.

On his return to Hinckley he immediately transferred to the volunteer battalion of the Leicestershire Regiment and remained in the 1st Battalion Volunteers until 1908 when the Volunteers were disbanded and then he served with the 4th Battalion of the New Territorial Army.

At the Coronation of Edward VII and Queen Alexandria on 9 August 1902 Gilbert was the senior NCO representing the Leicestershire Regiment unit and at the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 he was a Colour Sergeant with the 2/5th Leicestershire Regiment helping to drill new recruits who went on to serve in Ireland during the Sinn Fein Easter rebellion of Easter 1916 before being promoted to Regimental Quartermaster Sergeant.

Although there is a letter from Sharrad in the Leicestershire Record Office requesting a character reference for an Officer’s commission, he never became an officer, although he was awarded the Meritorious Service Medal in addition to his campaign medals.

He served with the army of occupation of the Rhine in Cologne and received his discharge in 1921 and was awarded the Territorial War medal and the Volunteer Long Service and Good Conduct medal in recognition of his long army career of 35 years going back to 1886.

In July 1937 he paraded before King George VI and the Queen in Hyde Park with a detachment of the Leicestershire and Rutland War Veterans Association.

In civilian life he worked as an accounts clerk in local Hinckley hosiery factories; fellow employees remembered him as a quiet and modest man, small in stature, with glasses and a white moustache.

Although he married later in life, his wife died in 1940 and he was a widower for the rest of his life.

In his last years, 93 years old, deaf and blind, he was cared for by neighbours, until he accidentally fell into his fire and died of severe burns at his home De Montfort House, in Britannia Road.

The Hinckley Times for 11 March 1961 recorded the death of Burbage’s oldest resident at that time, but because he had no family, and perhaps no will, he was buried in an unmarked grave in St Catherine’s churchyard, Burbage.

A Memorial for Sharrad Gilbert’s unmarked grave 56 years after his death

It seems entirely appropriate that due to the efforts of Greg Drozdz, Joseph Barsby, Director of G. Seller & Co. Funeral Directors, The Burbage Heritage Group and the local community, a memorial headstone was placed on his grave to mark and commemorate this humble and modest man.

A large assembly gathered in September 2017 to commemorate the life of Sharrad Gilbert in a memorial service that included the Lord Lieutenant of Leicester Lady Gretton, the Mayor of Hinckley and Bosworth Cllr Ozzy O’Shea, Leicestershire County Council Chairman Cllr Janice Richards and Burbage Parish Council Chairman Cllr Stan Rooney.

References

S.H. Gilbert: Rhodesia and after; being the story of the 17th and 18th Battalions of Imperial Yeomanry in South Africa. Simpkin Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co. Ltd, 1901

www.angloboerwar.com/name-search - useful database of participants

The Hinckley Times

Dr R.M. Morris. The Umtali Hospitals. Rhodesiana Publication No 40, 1979

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: