Home >

Mashonaland East >

‘Chimurenga’: The Shona Rising of 1896-7; a summary of David Beach’s article

‘Chimurenga’: The Shona Rising of 1896-7; a summary of David Beach’s article

This summary of David Beach’s article of the same name that was published in the Journal of African History, 20, 3 (1979) P395-420 and represents a later interpretation of the Mashona uprising or First Chimurenga to Terence Ranger’s book Revolt in Southern Rhodesia 1896-7.

Also used is David Beach’s article Kaguvi and Fort Mhondoro published in Rhodesiana Publication No 27, December 1972, P29-47 which provides much background detail of the religious significance in the area around chief Chinengundu[1] Mashayamombe’s kraal and Kaguvi Hill[2] where the Mashona Rebellion initially broke out and also the military efforts by the British South Africa Company (BSAC) and imperial forces to subdue the rising.

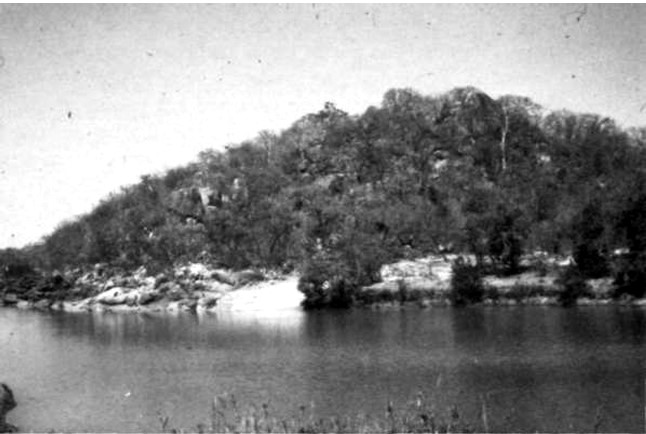

Photo D.N. Beach; Kaguvi Hill and the pool in the Umfuli (Mupfure) river

Conclusions reached by both Ranger and early historians

David Beach calls Terence Ranger’s work “seminal” in its scope, but finds his conclusions are very similar to earlier historians such as Hugh Marshall Hole and Howard Hensman who both wrote accounts shortly after the conclusion of the Mashona Rebellion (First Chimurenga) in 1897.

They thought the Rebellion was a ‘pre-planned conspiracy led by religious authorities’ and that it began with a ‘simultaneous outbreak on a given signal.’

Beach argues that the rising was neither pre-planned nor simultaneous. He writes that in the second half of 1896 with the Matabele Rebellion (Umvukela) still underway, in Mashonaland there was limited resistance to white rule in separate unconnected outbreaks although some Mashona communities were contemplating a full-scale war (Hondo)

When chief Mashayamombe sent messengers to Mkwati at Manyanga (Ntaba zika Mambo) in May 1896 along with Bonda a Rozwi headman living in the Range-Charter district and Tshiwa, he was asked by the Native Commissioner Moony why he had done so. Moony reported that Mashayamombe was, “in communication with someone in Matabeleland and had lately sent some young men down.” He added that he had “taxed old Mashayingombi with this, but he informed me that he had only sent down to the Matabele ‘Umlimo’ for some medicines to prevent the locusts from eating his crops next year.”[3] On their return the messengers brought news of how Bulawayo was under siege and of the amaNdebele impi’s on the Umguza river and this created a renewed sense of resistance amongst many of the Mashona communities.

Beach concludes that the impact of religious leadership was limited and that central pre-planning was non-existent.

White explanations of the causes of the Matabele (Umvukela) and Mashona (First Chimurenga) Rebellions

Marshall Hole, then civil Commissioner at Salisbury (Harare) blamed everything on the ingratitude of the Shona, “with true native deceit they have beguiled the administration into the idea that they were content with the government of the country…but at a given signal, they cost all pretence aside and simultaneously set in motion the whole of the machinery which they had been preparing.”[4]

Marshall Hole could not believe the Shona chiefs were capable of organising the rebellion; he blamed the amaNdebele, but primarily he believed the mastermind was Mkwati, ‘the high priest of the Mlimo’ who wished to extend the uprising in Matabeleland by intriguing with the Mhondoro’s[5] of Mashonaland.

As time went by other historians also introduced other factors that triggered the uprising including BSAC misrule with the grievances of the hut tax and forced labour and also the influence of other spirit mediums such as Gumboreshumba (Kaguvi) and Nehanda Charwe Nyakasikana (Nehanda) But one idea predominated and this was that the Shona people had a preconceived and co-ordinated plan of resistance that had been agreed upon in advance and kept secret for weeks or months until the signal came to start the killing.

Marshall Hole again, “In almost every kraal the natives, even the women and children, put on the black beads, which were the badge of the mhondoro, while their fighting men, with native cunning, waited quietly for the signal to strike down the whites at one blow. So cleverly was their secret kept and so well laid the plans of the witchdoctors, that when the time came the rising was almost simultaneous and in five days over one hundred white men, women and children were massacred in the outlying districts of Mashonaland.”[6]

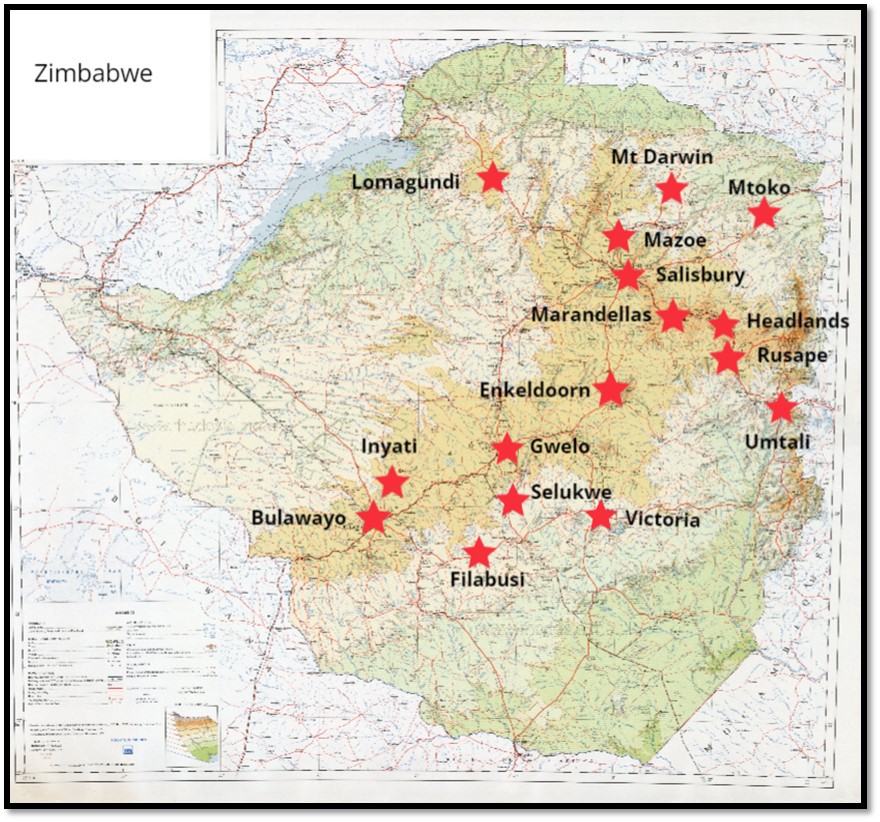

Places with 1896 names mentioned in the text

How BSAC rule impacted on Mashona society

Beach divides the impact into two periods:

1890 – 1894

During this period the Chartered Company efforts were focused in Mashonaland on finding payable gold reefs and in Matabeleland after the end of 1893. Prospecting tended to shift from area to area starting initially with Hartley and Mazoe and incidents of forced labour were quite limited. Taxation was planned but not applied and there was little white farming. White / Shona relations at this time were largely cordial.

1895 – 1896

During this period mining expanded rapidly and white farming increased. Labour demand outstripped local volunteers and migrant workers and often labour coercion took place during the busy agricultural season often with poor pay and rough methods.”[7] In 1894 the Hartley Mining Commissioner began to collect hut tax on a small scale. A Native Department was created with each district having one or two white officers[8] and a body of native police for enforcement. Witnesses in 1897 stated, “The thing that caused Chimurenga (the rising) was sjamboks, since that time people were being forced to work for the government. So these people were the ones who were being beaten thoroughly by sjamboks.” A Native Department station had been set up near Mashayamombe’s kraal to put increased local pressure on the community.

However from October 1895 the BSAC Police began concentrating in Bulawayo prior to the Jameson Raid leaving a much reduced police force in the districts that now had to be administered by the Native Department and the military forces were replaced by part-time volunteers in the towns, such as the Rhodesia Horse Volunteers.[9]

How had the Mashona managed to co-ordinate the timing of the rising so well?

Beach writes that this posed a curious problem for historians. The late March 1896 rising amongst the amaNdebele was easier to understand as they had a defined state from their arrival in the 1840’s that was not destroyed, despite their King Lobengula’s death in early 1894, and their view of a state was still alive in 1896. But the Mashona enjoyed no such political unity, the Changamire Rozvi confederacy which had united them had been destroyed by the amaNdebele; so how had they managed their uprising in June 1896?

Beach states that Ranger’s argument of how they managed this feat comes very close to Marshall Hole, although his explanation of why the rising occurred due to BSAC misrule was very different. Ranger agreed with Marshall Hole that the rising was a ‘sudden and co-ordinated attack’ a ‘co-ordinated force of arms’ ‘concerted action’ ‘almost simultaneous’ and ‘preceded by a ‘period of apparent calm [during which in early 1896] preparations for revolt were being made.’

There had been some localized resistance to individual whites and the BSAC from 1891-6 but the real inspiration for the Mashona uprising was the amaNdebele rising (Umvukela) in late March 1896. This was orchestrated by Mkwati, the ex-Leya slave and priest of the Mwari cult aided by his assistants, Tenkela-Wamponga known to the amaNdebele as Usalugazana, and Siginyamatshe, the ‘stone-swallower,’ real name Siminya who was an important Mwari messenger and lived at Ntabeni kraal near Bulawayo and worked especially with the Manyanga shrine at Ntaba zika Mambo.

Ranger’s theory for the Mashona Rebellion

In April 1896 Tshihwa, a Rozvi Mwari-cult officer living in the Gwelo (Gweru) district contacts Bonda, another Rozvi Mwari-cult officer living at the Range-Charter district under chief Musarurwa, and chief Mashayamombe on the Umfuli (Mupfure) river in the Hartley (Chegutu) district. During May Bonda and chief Mashayamombe’s messengers went with Tshihwa to Mkwati at Manyanga (Ntaba zika Mambo) and talked with Mkwati who encouraged them to spread the rising in Mashonaland. On their return to Hartley chief Mashayamombe contacted Gumboreshumba, grandson of Kawodza, the great spirit medium of the Chaminuka mhondoro spirit killed in 1883 by the amaNdebele, who was then living at chief Chikwakwa’s kraal near Goromonzi.

Gumboreshumba became possessed by the Kaguvi spirit in the late 1880’s and grew in local importance through supplying good luck in hunting but became widely-known largely through his role as the svikiro of the spirit husband of Nehanda, even over all the other mhondoro’s. In Ranger’s words he was chosen by chief Mashayamombe, “when there was need for a man to link the planned uprising in the west [Hartley and Charter] with the paramount’s of central Mashonaland” and he made this happen by moving north of Mashayamombe’s which became the “powerhouse of the Shona rising.”

A series of meetings are organised to co-ordinate the Mashona rising

At the end of May or beginning of June 1896 the Kaguvi spirit medium summoned the agents of the central Shona paramount’s to Hartley using the pretext of distributing anti-locust medicine. The paramount’s each sent trusted headmen or close relatives and in many cases their sons. Chief Chikwakwa sent Zhante, his army commander, chief Zvimba his son, chief M’Southi sent his younger brother. chief Garamombe sent his son. Others included Panashe, the son of chief Kunzwi-Nyandoro and Mchemwa, son of chief Mangwende and the sons of chief Chingaira Makoni. Information was then given of the success the amaNdebele impi’s were having in besieging Bulawayo and their success against the white patrols on the Umgusa river.[10]

These meetings had representatives from Gutu, Hartley (Chegutu) Lomagundi (Makonde) Marandellas (Marondera) Mazoe (Mazowe) and Umvukwes (Mvurwi) districts – virtually all the areas that took an active part in the Mashona Rebellion. Most of the local Mashona mhondoro mediums supported an uprising including Nehanda in Mazoe and Goronga in Lomagundi.

The signal for the uprising is given

In June 1896 Tshiwa, Bonda and some amaNdebele arrived back from Manyanga with Mkwati’s instructions for an uprising. Tshihwa went south to Selukwe (Shurugwi) Bonda went to Charter, Kaguvi moved between Hartley and Goromonzi. The signal for the killings of whites came from messengers sent by the mhondoro mediums and chiefs and by pre-arranged signal fires.[11]

After June the uprising participants needed to alter their tactics as the military situation changed in both Matabeleland and Mashonaland.[12] In August Lt-Col Alderson had attacked chief Chingaira Makoni’s kraal at Gwindingwi with mixed results and that was soon followed up by Major Watts with a force of 180 Umtali volunteers and 50 soldiers from the West Riding Regiment and one seven-pounder gun. After Makoni and his people retreated into the caves a siege of 4-5 days took place and the caves were dynamited before chief Makoni was forced to surrender and controversially shot by firing squad.[13]

Bonda became the liaison officer at chief Mashayamombe’s, “carrying messages, raiding loyalists and generally playing a most significant role.” Mkwati, forced from Manyanga, by Colonel Plumer’s force[14] came with Tenkela-Wamponga to chief Mashayamombe’s kraal on the Umfuli river. Both Mkwati and Kaguvi planned to move to the east of Salisbury in the area of chiefs Chikwakwa and Kunzwi-Nyandoro to encourage and support their resistance. This was effective. Colin Harding writes that he had many parleys with chiefs mostly without success, including with chief Chikwakwa. “I have described but one of the many palavers Father Bieler, Howard and I had with native chiefs endeavouring to smooth the way to a satisfactory and permanent peace. Our interviews were not all successful...”[15]

The uprising had success in the north-east where chief Gurupira and 550 friendlies supported a patrol under Native Commissioner Armstrong and Harding although Harding comments, “Personally I do not for a moment believe that Gurupila cared a hang for either Armstrong or the Chartered Company, but he and his people had a grudge against one or two Mashona chiefs...”[16] On Domborembudzi mountain (Shona: mountain of Goats) a skirmish took place where chief Gurupira was mortally wounded and his friendlies retreated back to Mtoko (Mutoko) with his body and Armstrong was forced to retreat for lack of supplies to Umtali. In the end the superior forces and tactics of the whites in attacking each rebel chief separately finally brought the rising to an end.

Ranger considered the co-ordination of the outbreak was not achieved through the paramount’s alone but was achieved only with the aid of their traditional religious authorities who were able to harness the commitment of the people in a way that far outweighed their loyalty to the chiefs. This was Ranger’s overall impression of the Mashona Rebellion and was accepted for at least a decade.

David Beach’s alternative re-evaluation of events in 1896

In summary his own findings, presented below, were that the risings were not ‘simultaneous’ or even ‘almost simultaneous’ even given that communications were comparatively slow and that secondly, the risings had not been determined and co-ordinated in a way that Ranger had assumed. Therefore according to Beach, the need for an overall ‘religious’ or ‘political’ organisation to manage the process falls away and understanding the social and political situation as outlined by Ranger requires revision.

The basis of the Mashona economy

The Mashona economy is described by Beach as having an agricultural base with supporting production from herding, hunting / gathering, manufacturing and mining and external trade. By the late 10th century the last three segments were in a depressed state relative to earlier periods. The agricultural base was key and depended on the preparation of fields and planting of grain in early summer – October to November and their reaping at the start of winter – March to June. Grain storage limitations meant the annual crop cycle was essential with the threat of disaster (shangwa) from drought or locusts ever present.

There is little resistance to BSAC rule before 1894

Beach maintains there was no rising before 1894 because there was little pressure on the Mashona during that period. Many Mashona believed the white presence was only temporary much like that of the Portuguese between 1629 – 1693. Also some Mashona rulers found the whites useful in local politics with many clashes between Mashona and whites before 1894 being engineered by other Mashona groups to their own advantage.

Resistance to the BSAC starts to increase but not in any co-ordinated way

However after 1894 resistance to BSAC rule became more noticeable but took the form of isolated and seemingly unconnected incidents. Resistance took the form of desertion from forced labour, abandoning kraals as a result of tax and labour demands, theft, cattle-maiming and actual violence.

Initially the violence was limited to the Native Department or police who were enforcing the labour and tax collection, or to actual employers of labour, but not to the general white population. Beach gives numerous examples.

August 1894 – a policeman collecting labour in the Lomagundi district is murdered

September 1894 – Chief Kunzwi-Nyandoro’s forces chase police who are trying to arrest his son Panashe

October 1894 – a policeman is killed at Makoni’s kraal near Rusape

April 1895 – Native Commissioner Armstrong is threatened by the Budya at Mtoko

October 1895 – Chief Kunzwi-Nyandoro’s forces fire on police patrols

December 1895 – Chief Gezi’s people in Marandellas attack the police

February 1896 – two of Native Commissioner Armstrong’s police are murdered and his patrols fired upon

February 1896 – Native Department police collecting hut tax are fired upon in the Charter district and sjambokked by the Nyanja

March 1896 - Chief Gezi’s people in Marandellas attack the police again

April 1896 – Chief Kunzwi-Nyandoro openly threatens the police and local whites

April 1896 – Chief Marange in the Umtali district uses armed force to recover confiscated cattle

May 1896 – Native Commissioner Ruping’s patrol is attacked by Budya at Mtoko and the district remains tense[17]

May 1896 – a miner is murdered in the Lomagundi district

It is clear that these incidents of violence were not part of any general Mashona rising, despite central districts of Mashona being extremely tense between March – June 1896. Beach states that the more militant chiefs were even then discussing the possibility of a full Hondo (war) but that this was done independently of each other and there is no evidence of widespread joint-planning of the Mashona Rebellion before June. Chief Kunzwi-Nyandoro’s threat to attack all whites was not carried out, in May at chief Mashayamombe’s kraal there was talk of killing the police and local Indian traders, but it was not carried out. In the Marandellas district, Muchemwa the son of chief Mangwende had been talking about armed resistance and the Marandellas Native Commissioner ‘Wiri’ Edwards received hints that a rising might take place with a pair of sandals left at his door and talk of a bird from Mwari.

Normal Shona politics continued despite the rising

In April 1896 political tension within chief Mutasa’s district near Umtali led to the Chimbadzwa people leaving for Barwe. In November 1896 the Pako people allied with the Ngowa and tried to recover Chirogwe ancestral hill from chief Chivi’s Mhari who had seized it. Neither Chimbadzwa nor Pako took part in the rising. In April and November 1896 rumours spread that chief Mutasa would attack Old Umtali; in fact he aided the BSAC. In October 1896 after false reports the Victoria forces attacked the Duma people; but the Duma still remained neutral.

Opportunist theft from deserted stores did take place and there were robberies against whites and foreign Africans. Chingoma’s people attacked Carruthers at Belingwe and Chipuriro’s people killed their chief’s son-in-law Box, Box’s bother and migrant workers from the Zambesi, but the thieves were simply taking advantage of the troubled times and were not part of the uprising. Beach calls this ‘peripheral violence.’

Even in Mtoko, prospectors were not attacked until 25 June when news of the main rising reached local Budya, chief Kunzwi-Nyandoro’s people rose on 20 June, chief Chingaira Makoni about 23 June, whilst chief Marange stayed neutral.

Beach’s sequence of events for the Mashona Rebellion

The amaNdebele Rebellion began towards the end of March 1896 and most of their Shona Maholi joined them. However in the south-east across the southern Shona territory ruled by chiefs Chivi, Chirimuhanzu, Gutu, Matibi and Zimuto the amaNdebele Rebellion stalled, mostly because they feared an amaNdebele victory more than the fact that they suffered under BSAC rule.

At the edge of the north eastern range of amaNdebele raiding parties were the Umniati and Sebakwe river valleys that were relatively thinly populated. AmaNdebele patrols had penetrated this area as far as the Umfuli (Mupfure) river and in May reached Payne’s farm in the Mwenezi Range where they recovered cattle taken by Payne in 1893 and some Mashona in these areas did join the rising.

The close connection between religion and the Mashona economy

Mashona religious leaders of all the different cults were expected to use their connections with the senior mhondoro spirits to produce rainfall and to avert droughts and this function could not be suspended, even during the rising. Siginyamatshe was still distributing anti-locust medicine in 1897 at Belingwe whilst on the run from the authorities. Marshall hole and Ranger both believed these religious activities were from the beginning a political cover, but Beach states the evidence suggests that the initial contact was purely of a religious-economic nature and only later assumed a political role.

Beach does not think Mkwati was the religious supremo of the rebellions believed by Ranger, although he was an important local religious figure at Manyanga (Ntaba zika Mambo) In the summer of 1895-6 the crops suffered from locust swarms and chief Mashayamombe sent messengers to get anti-locust medicine from Mkwati. The first initiative for contact came not from Mkwati, but from Mashayamombe, and his kraal became a distribution point for locust medicine. A witness later recalled, “I remember the people assembling at Mashingombi’s kraal to get medicine for the locusts. This had nothing to do with the rebellion.”[18]

Kaguvi, real name Gumboreshumba becomes involved

Mashayamombe decided to make some profit from the anti-locust medicine and sent a message to Gumboreshumba, medium of the Kaguvi spirit. Gumboreshumba was the grandson of Kawodza, a previous medium of the Kaguvi spirit killed by an amaNdebele impi on Lobengula’s orders. Kawodza had lived in the Chivero district in the 1860’s,[19] and was killed at Kaguvi Hill in an amaNdebele raid, but Gumboreshumba now lived at chief Chikwakwa’s kraal bordering the territories of Kunzwi-Nyandoro, Seke, Rusike, Chinamora and Mangwende. Kaguvi’s spirit was thought to be the spirit husband of the Nehanda spirit and Gumboreshumba had made the Kaguvi spirit well-known for his ability to find game.

When Kaguvi’s messenger arrived at Mashayamombe’s kraal for the anti-locust medicine he was asked for a payment of one cow. This Kaguvi refused, but about this time he moved from Chikwakwa’s to Chivero.[20] Mashayamombe’s demand for payment from Kaguvi led to a difference of opinion between them and from now they were to act independently of each other and not in unison as was widely thought at the time.

The religious-economic element between amaNdebele and Mashona changes to political

About this time another religious leader and Rozvi named Bonda, born in the Selukwe (Shurugwi) area and now living at Charter where he founded a small religious centre. In June 1896 he travelled to Mkwati’s, Beach thinks it may have been for anti-locust medicine or just to make contact.

There they heard the news of the amaNdebele Rebellion from Mkwati and received the encouragement that was to result in the Mashona rebellion. In April 150 volunteers of the Rhodesia Horse Volunteers under Robert Beal had left Salisbury with 200 Shona friendlies to assist the besieged people of Bulawayo. On route they fought skirmishes with Chief Uwini at Makalaka Kop on 30 April and at Amaveni and Nxa on 9 and 22 May. Bonda carried the false news back to Mashonaland that the column had been destroyed and this news had a great effect on the people.

Up to this point interaction between the amaNdebele and the Mashona had been about locust medicine. Beach believes the political element now came to the fore. Mkwati sent Tshihwa the Rozvi representative, but Beach believes his impact was outweighed by the amaNdebele secular leadership who sent some men of the Mangoba regiment to Mashayamombe’s and about six men of the Insugamini regiment to back up Bonda at Charter in the second week of June 1896 and to incite a rising at Hartley and Charter.

This is in marked contrast to Ranger who believed there had been contact between the Mashona and Mkwati since April and that planning for the uprising had taken place between Mashayamombe and the Kaguvi medium before the arrival of Tshihwa and the amaNdebele. Beach differs from Ranger in these aspects:

- There was no planning in advance

- There was no joint headquarters for the uprising either at Mashayamombe’s kraal or where Kaguvi was now living at Chivero

- There is plenty of evidence that the people in the districts only heard of the uprising a day in advance

Kaguvi sent messages to chief Mashonganyika’s near Goromonzi and then onto Gondo’s kraal asking them to send representatives. One of them who visited the medium in his new home base was Zhante, chief Chikwakwa’s commander, but this was after the rising had broken out in the Chivero district. Giving evidence later he said, “I thought he would give us something to kill the locusts. When I got there I found he had a lot of white men’s loot.[21] He ordered me to kill the white men. He said he had orders from the gods. Some Matabele who were there said watch all the police wives. I returned and gave Chiquaqua Kagubi’s orders.”[22] Zhante was probably at Kaguvi’s kraal on 14 June 1896.

Beach also disputes Ranger’s statement that a ‘conference’ took place. There is no evidence that anybody from Lomagundi, or Panashe, son of Kunzwi-Nyandoro, or Muchemwa, son of Mangwende or the turbulent sons of Chingaira Makoni came to Kaguvi’s at Chivero before the rising.

How did news of the rising spread?

Beach says the Mashona used the lunar calendar – they could have had a simultaneous rising if it had been preplanned using the chiwara signal-fire system, but this was not used except in the Mazoe and Marandellas districts,[23] and the Mashona paramount’s simply joined the rising, opposed it or stayed neutral as the news reached them.

Messengers took five days from Sunday 14 June[24] to cover the 75 miles (120 km) from Mashayamombe’s kraal to Mangwende. Most Mashona districts had the news within 7 days (i.e. by Sunday 21 June) but some areas in the north-east only received the news by Thursday 25 June. Beach writes that Ranger obscures the timing issue by first referring to the Marandellas district where the rising began on 19-20 June.[25] This ripple effect was considered by Ranger but rejected because BSAC ‘experts’ rejected it, but the Mashona often use the word Chindunduma to describe the rising and this means ‘ripple’ as well as ‘rage.’

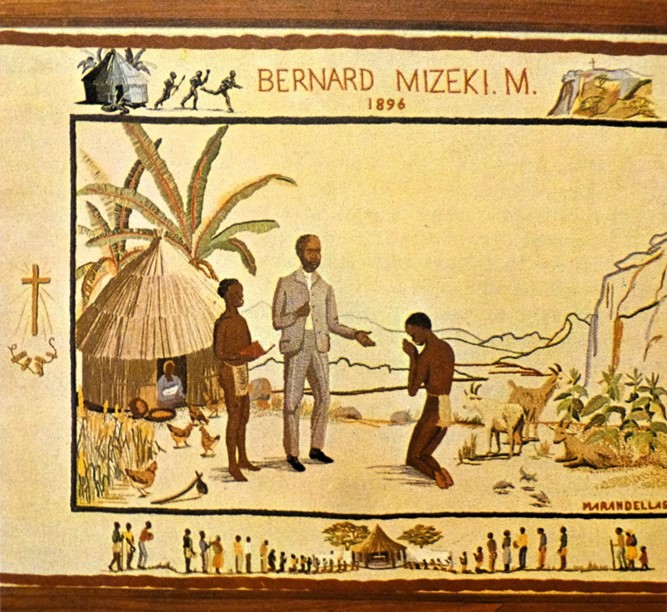

From Rhodesian Tapestry: A History in Needlework. Bernard Mizeki catechizing – this was embroidered by the Marandellas Women’s Institute.

Technically the rising may have started on Thursday 11 June 1896

On that day a clash developed between the wives of Muzhuzha Gobvu, the nephew of chief Mashayamombe and Native Commissioner Moony’s African police. When it escalated Moony had Muzhuzha thrashed. “…it is when this chimurenga started, it started…because this camp was in Muzhuzhu’s village and then the fighting started straight away after the beating of Muzhuzhu.”[26]

Mashayamombe’s people stated this incident began the rising and the sole surviving policeman agreed this in evidence in 1897. “About three days before Mr Mooney was murdered, Mjuju thrashed Jim's wife. On the women coming to complain about the matter, Mr Mooney thrashed Mjuju. Four men of Umjuju’s kraal ran out with guns. These were taken away by Mr Mooney and sent to Hartley to Lukata [Thurgood]

…Janatilla and Jhanda deserted the night before we went to the coolie’s taking their guns with them. On the third day, after the guns had been sent to Hartley we accompanied Mr Mooney to the trading station of the coolies across the Umfuli river.[27] On our arrival there we found that they had been killed, so we returned to Umjuju’s kraal...Before arriving at Mr Mooney's huts, Makomani deserted with his gun. On getting to the huts, Kaseke and Mhlambezi went into Mr Mooney's hut, put down their guns and went away…We were told by Mr Mooney to cook some food before starting for Hartley. Jarivan went up to his wife's hut in Umjuju’s kraal. He there saw the impi coming into the kraals. He ran away to Mr Mooney and told him of it and said, ‘Let us run.’ Mr Mooney then mounted his horse and said, ‘Come along, let us go.’ The Mashona followed us up and opened fire on us.”[28]

Thus it appears that Moony’s action in flogging Muzhuzha, the nephew of chief Mashayamombe triggered the rising from talk into widespread action. Moony himself was followed by Mashayamombe’s brother Chifamba as far as the Nyamachecha river where his horse was wounded and he climbed a small hill where he was killed in the ensuing gunfight. Soon afterwards two traders,[29] John Stunt and A. Shell, with seven Zambesi Africans arrived at Muzhuzha’s and were set upon and killed.

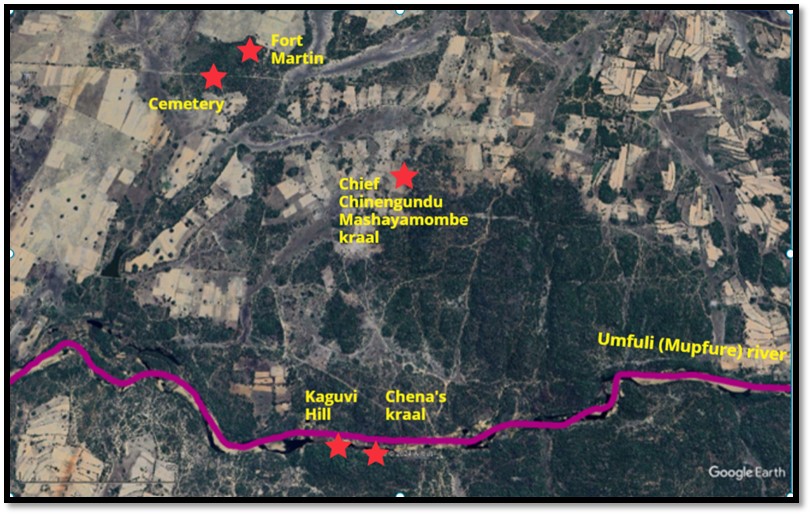

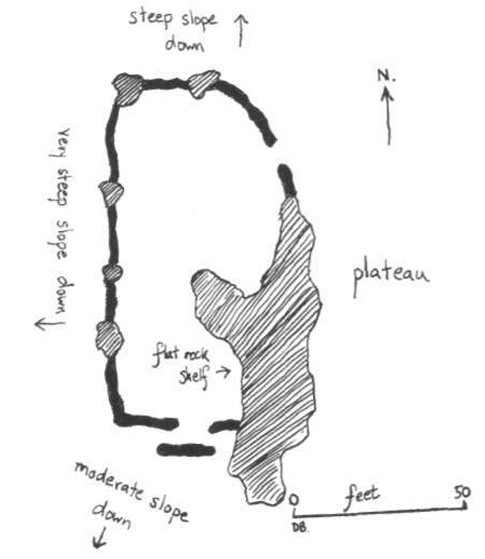

Area around chief Mashayamombe’s kraal; names mentioned in the text

Most Mashona had no inkling that a rising was about to begin

The organisation of the rising comes out in the evidence regarding the murder of Hepworth[30] on 17 June. Mashayamombe called his medium, Dekwende and said they were going to murder the white men. Dekwende called the people together and became possessed by his spirit. Dekwende’s son gave evidence, “I heard Dekwende order the men to kill the white man…He said this about 8pm in the night before the man was killed. The next morning Mgangwi said I was to come with him to help carry the blankets of Kagono and the others who were going hunting to the Zwe Zwe.” As they approached Hepworth's, “Kagono…told us that the eland hunt was a blind and our real orders from Mashayamombe were to kill the white man.”[31]

It is clear that even chief Mashayamombe’s relatives were unaware of the rising until the night before it broke out and Kakono’s raiders were only told once the killing mission was underway. Another example of unawareness of the rising is shown by the man who actually killed Native Commissioner Moony, Rusere, who had just come from Kaguvi’s kraal and was told Moony was being pursued and borrowed a gun from his uncle. None of chief Mashayamombe’s people claimed he had directed the killings – it was his medium Dekwende of the Choshata mhondoro that gave the directions.

On 15 June Mashayamombe’s forces went east to Beatrice mine[32] and west to the Umsweswe river and on the 18 June they begun the siege at Hartley Hills.[33] The rising began to spread to the south-east, “I remember the beginning of the rebellion, a messenger came from Mashingombi saying that Kagubi had given orders for the white men to be killed, so the three prisoners and I and two others started early in the morning.” This was on 16 June and by 18-19 June the rising was widespread in the Charter district.

Bonda and the amaNdebele persuaded the Sango, Maromo and Mutekedza paramount’s to join in the rising, but Bonda does not appear to have taken a further active part. Tshihwa-Wamponga went back to Mkwati at Manyanga and was in the Selukwe district in July 1896.

News of the rising spread north and east from Mashayamombe’s to Mtoko and Makoni’s territories; it gives a good idea of the medium Kaguvi’s influence. Beach says he may not have known of the rising’s start on 14 June, but by 16 June he was giving it his whole-hearted support when his messenger arrived at Nyamweda’s kraal. Norton’s cattle were stolen that night and the Norton family murdered the next day.[34] Word of the rising spread north; on 18 June the Mashona on the Gwebi river had joined in. To the east of Salisbury Zhante brought the news on 19 June and the murders commenced the next day. The same happened in the Mangwende area.

Photo J.D. Cobbing: The svikiro’s cave at Kaguvi Hill

In Makoni’s territory tensions had been brewing. The Native Department concentrated all whites at Headlands where an attack was made by Mangwende and Svosve’s people on 22 June and Makoni only became active next day. The Lomagundi and Abercorn (Shamva) districts only became active from 21 June, 24-25 at Mtoko and from the 25 June at Mt Darwin.

Salisbury was on alert from 17 June; telegraph messages were sent to Mazoe and this is why the Alice mine inhabitants were warned before fighting broke out on 18 June.[35] However many whites in outlying areas did not receive notification and were surprised and murdered.

Kaguvi’s influence is not as widespread as Ranger asserts

Beach contends that Kaguvi’s role in the rising as described by Ranger was too sweeping and that Kaguvi’s influence was really only in the Chivero-Nyamweda area of Hartley where his grandfather, Kawodza had been active and also where he had previously operated in the Chikwakwa and Kunzwi-Nyandoro area adjacent to Goromonzi. He states there is no doubt that the Kaguvi medium was influential in those areas. Nor is it surprising that as the Kaguvi spirit of Gumboreshumba was the husband of the Nehanda spirit that he was for a while more influential than Charwe, the Nehanda medium.

Beach concludes that since the Kaguvi spirit was not the supreme co-ordinating figure in the Mashona Rebellion that the Mashona did not need such a figure and he is of less significance than it might have been.

The Mashona paramount’s primarily fought a defensive rebellion

Apart from some raids by Mashayamombe’s people to Charter and Hangayiva, 72 and 105 kms away, for essential supplies, the paramount’s fought almost entirely within their own territories and rarely combined to attack targets.[36] Beach maintains where they did combine in 1897, it was usually because they had been driven out of their own territories. Bonda and Maromo moved from Charter to Mashayamombe’s after the rising collapsed in their area in September 1896. When Kaguvi was driven from Chivero by Captain C. White’s patrol[37] on 26 July he also moved into the area and cooperated with Dekwende but stayed at Chena’s kraal on the south bank of the Umfuli river opposite Mashayamombe’s kraal. Mkwati and Tenkela-Waponga were also forced to move eastwards and established themselves temporarily at Mashayamombe’s.

Ranger’s concept of Mkwati and the Kaguvi mediums trying to revive the Rozvi confederacy is illusionary

Beach writes that Kaguvi did encourage chiefs Chikwakwa, Kunzwi-Nyandoro, Chinamora and Mangwende to hold firm and not surrender towards the end of 1896 but the Rozvi confederacy idea was produced by the Native Department from a minor incident. In late December 1896 three senior Rozvi’s Chiduku, Mbava and Mavudzi travelled to Ndanga and asked Chikowore Chingombe, the leader of the Mutinhima Rozvi house to return with them to Mavangwe and be their Mambo.

The Native Department officials were alarmed because of a series of reports that the Kaguvi medium was planning to collect Rozvi recruits from Chiduku on the upper Sabi river, that Bonda had travelled to the same area, another report that Mwari cult messengers had been in the Ndanga district and that certain Rozvi had returned to Ndanga and told the local Makalaka people that there was no point in cultivating their lands as the “Mlimo had gone to get the assistance of Mudsitu Mpanga Mtshetstunjani and Govia to help him” wipe out all the whites and friendlies.[38]

Beach states Ranger assumed that only the arrest of Chingombe stopped the plan from developing. In fact many of the rumours outlined above were false and just part of the local politics as the Rozvi had no effective fighting force.

Chief Mashayamombe and Gumboreshumba, the Kaguvi medium quarrel

Beach writes that Kaguvi leaving Chena’s village on the Umfuli river for the Goromonzi area was not part of any masterplan but arose because of bad blood between him and chief Mashayamombe. It was customary for spirit mediums to be assisted by girls, servants rather than wives, chief Mangwende had offered seven girls as a gift, but Kaguvi seized other women from Mashayamombe. Fighting followed and two of Kaguvi’s men were killed and there was virtually a state of war between them.

In January 1897 Herbert Taylor, the chief Native Commissioner, accompanied by Col F. de Moleyns,[39] commander of the British South Africa Police, Native Commissioner John Brabant and Hubert Howard, Lord Grey’s representative, met with chief Mashayamombe for talks.

When Taberer heard of the dispute between Mashayamombe and Kaguvi he told the chief he would be left alone and “that he was not to consider any action taken against the mondoro [sic) as including him.”[40] The BSA police and Mashayamombe now formed a temporary truce whilst the police tried to capture the spirit medium but he had fled away to try and join the amaNdebele under Gwayabana on the lower Umfuli. De Moleyns and 186 men left Hartley Hills on 12 January 1897 to make a night attack on Chena’s kraal where the medium was supposed to be present. But the force was defeated by the thick bush and darkness.

De Moleyns reported, “…I was informed by spies sent on by Captain Brabant that the natives were awake, occasionally firing off guns, shooting, etc. and had men on the lookout, and under the circumstances I considered that even if I could affect an entrance into the kraals it was very doubtful whether I could capture the Mandoro [sic] I decided not to make the attempt. I allowed the men to sleep to daylight, 13th and then… reconnoitred the country around Mandoro’s kraal and selected a position for a fort, where I established myself, distance 9 miles E.S.E. of Hartley, 1 mile from the Umfuli and about 4 miles from the Mandoro’s. The fort is on a kopje rather too extensive for the force that I can leave here, but excellently situated for harassing operations and capable of good defence.”[41]

Fort Mhondoro as drawn by D.N. Beach

Kaguvi abandons Kaguvi Hill and Chena’s village

On 17 January de Moleyns’ men occupied Kaguvi Hill where they found a quantity of loot, but the position had been evacuated by Kaguvi who moved 500 yards east. De Moleyns was then informed by Mashayamombe,[42] although the truce was now over, that the medium had fled. Gumboreshumba was chased, some of his women were captured by the neutral chief Rwizi near Beatrice mine, but the spirit medium himself eluded capture and made it back to his old patch near chief Chikwakwa’s kraal where he continued to encourage the paramount’s to carry on fighting.

Resistance continues in Mashonaland in 1897 but it was every paramount for himself

As time went on Kaguvi lost influence east of Salisbury when he was driven away so that he became less influential than the Nehanda medium. Even when Native Commissioner Armstrong and a few police led the Budya under Gurupira on an attack on Mangwende and eastern Salisbury resistance strongholds and Gurupira was fatally wounded on 23 April, the Budya did not change sides, but went home.

Why resistance crumbled in the Mashona rebellion

Beach attributes three reasons to this:

- A number of paramount’s collaborated with the whites. The Gutu, Chirimuhanzu, Chivi and Matibi rulers wanted to unite against the amaNdebele. Internal conflicts between paramount’s also influenced their decision to collaborate. Land was an issue between Maburutse and Maromo; Gunguwo and Maromo were already in conflict. The north-western Nyanja ruler’s Ranga and Kwenda refused to kill the African missionaries living with them when asked to so by Mutekedza and Svosve and collaborated with the BSAC. The Mutasa dynasty was neutral at first and later collaborated. The Budya initially joined the rising, but then turned neutral and later collaborated. Those that collaborated prevented the rising from spreading further and enabled Umtali and Victoria to be used as resupply bases.

- The role of the Imperial troops was played down by the BSAC but their numbers and military tactics were superior. They withdrew from indefensible positions and concentrated where they could defend themselves. By concentrating their firepower and numbers on each Mashona ruler in turn they could defeat them

- The final reason was that Mashona food crops were raided by troops and destroyed or removed. Beach thinks the fighting ended in the summer of 1897 not so much because of the fighting but because it was vital for the summer crops to be planted.

Final Conclusion

There is similarity between the way Ranger and early historians (Hensman, Marshall Hole, etc) looked at the Mashona Rebellion (Chimurenga) with both saying it was a pre-planned conspiracy led by religious officials and its outbreak was nearly simultaneous. In fact, it was neither pre-planned nor simultaneous. As Beach has explained above, the atmosphere in Mashona communities was ripe for rebellion, but the initial outbreaks of violence were separate and unconnected with some extremists talking of a full-scale Hondo (war) However Shona communities were too disunited to carry out such an organisation in the secrecy required in order for it to succeed and there were too many prepared to collaborate with the whites. Mashona women had married newcomers and remained loyal to their husbands which is why the amaNdebele at Kaguvi’s told Zhante that the wives of policemen had to be watched.

Beach believes that the Kaguvi medium Gumboreshumba was not influential over the wide area that Ranger believed. His promises that the white man’s bullets would turn to water had been found wanting and Beach states it was noticeable that the Shona did not rely on them and fought from cover. In general the ideology behind the rising was not religious but because, “They were sick of having the white men and wanted to drive them back to the diamond fields.”[43]

In 1896 there was a threat of a famine, 1895 was a bad year for locusts which devastated the crops and led the paramount’s, including chief Mashayamombe, to send messengers to Mkwati at Manyanga (Ntaba zika Mambo) who was then a principal leader in the Matabele Rebellion (Umvukela) to get locust medicine. False rumours of the defeat of Beal’s Rhodesia volunteers was given to these messengers . Kaguvi told Native Commissioner Kenny after his capture in 1897 that Mkwati told the messengers he was a god and could kill all the whites and was doing so at that time in Matabeleland and that he, Kaguvi, would be given the same powers as Mkwati and was to start killing all the whites in Mashonaland.[44] Beach states this led to a ' ripple effect' in which Shona communities resisted or collaborated as the news reached them. However to emphasize he believes the element of religious leadership was limited and central pre-planning non-existent.

References

D. N. Beach. ‘Chimurenga’: The Shona Rising of 1896-7. Journal of African History, 20, 3 (1979) P395-420

D. N. Beach. Kaguvi and Fort Mhondoro. Rhodesiana Publication No 27, December 1972, P29-47

C. Harding. Far Bugles. Simpkin Marshall Ltd, London, 1933

T.O. Ranger. Revolt in Southern Rhodesia 1896-7. A Study in African resistance. Heinemann, London 1979

The ’96 Rebellions. Reports on the Native Disturbances in Rhodesia. Books of Rhodesia. Bulawayo 1975

H. Marshall Hole. Witchcraft in Rhodesia. The African Review, 6 November 1897

[1] Chinengundu held the traditional Mashayamombe title in the 1890’s

[2] Kaguvi Hill on the south bank of the Umfuli (Mupfure) is above a pool in the river that is said to ever dry up and from it came the noises of cattle, sheep, goats and cockerels. At the top of the hill among the great granite boulders a cave became the site for a Shona spirit medium’s shrine with great religious significance to local people. Beach writes it is also a stronghold with a perimeter of stone walls. From here much of the ideological impetus for the rising originated

[3] Kaguvi and Fort Mhondoro, P35

[4] The ’96 Rebellions, P69

[5] Mhondoro is the term used for a deceased person of political person. Although shumba is the usual Shona word for lion, mhondoro also means lion in the sense that an important deceased person’s spirit normally lives in the body of a lion

[6] The ’96 Reports list 114 civilians murdered or missing in Mashonaland with a total civilian population of 1,497 at 31 October 1896; 145 civilians murdered in Matabeleland

[7] Kaguvi and Fort Mhondoro, P34

[8] At Hartley the first Native Commissioner was H. Thurgood (Rukwata) followed by D.E. Moony (Moni)

[9] The Rhodesia Horse Volunteers was raised in April 1895 with units at Salisbury, Bulawayo, Victoria and Umtali and Victoria in Mashonaland and disbanded the following year.

[10] See the article Bulawayo and the Matabele Rebellion (or Umvukela) – Part 1, the first few weeks and the patrols sent to rescue outlying farmers, prospectors and storekeepers under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[11] Some of the killings are described in the article Mashona Rebellion / First Chimurenga 1896-7 graves at Old Marandellas (Ruzawi Cemetery) under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[12] See the article Bulawayo and the Matabele Rebellion (or Umvukela) – Part 2, after the first few weeks, a change in tactics under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[13] See the article Colin Harding – the man in charge of the execution of Chief Chingaira Makoni – his life and career in early Rhodesia under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[14] See the article Battle of Ntaba zika Mambo, Manyanga or Mambo Hills under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[15] Far Bugles, P58

[16] Ibid, P61

[17] Native Commissioner Herman Henry Ruping was murdered about 24 June by his own police at M’lewa’s kraal in the Abercorn (Shamva) district. [Source: The ’96 rebellions]

[18] Chimurenga: the Shona Rising of 1896-7, P407

[19] Information from D.P. Abraham

[20] Kaguvi was now between Hartley and Salisbury at Mupfumera’s in the Chivero district

[21] Beach believes the loot belonged to Thurgood and was taken from his agent George who had a store nearby

[22] Chimurenga’: The Shona Rising of 1896-7, P409

[23] Native Commissioner ‘Wiri’ Edwards noted the fires on the hilltops around Marandellas

[24] Ranger dates the start of the rising from Friday 19 June 1896

[25] Jean Farrant who wrote Mashonaland martyr: Bernard Mizeki and the pioneer Church states Mizeki was murdered on 17 June is probably mistaken – more likely to have been 19-20 June. The upper border of the Bernard Mizeki Tapestry depicts the scene of his martyrdom, while the lower border depicts pilgrims coming to the shrine later erected on the site of his hut. The motif to the left depicts the triumph of the Cross over the witch doctor’s bones. The granddaughter of chief Mangwende, Lily Mutwa married Mizeki in March 1896 three months before he was murdered and after his death became a catechist in her own right. See the article Bernard Mizeki Shrine under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[26] Kaguvi and Fort Mhondoro, P36

[27] The first fatalities of the rising were probably these three Indian traders killed at their store on the south bank of the Umfuli (Mupfure) river whose deaths are not listed in The ’96 Rebellions

[28] Ibid, P37

[29] The ’96 Rebellions lists them as prospectors

[30] John Charles Hepworth murdered in the Hartley district at Wallace’s farm, mine manager at the Renny-Tailyour Concession [Source: The ’96 rebellions]

[31] Chimurenga’: The Shona Rising of 1896-7, P411

[32] At the Beatrice mine William James Tate and S. Koefoed were murdered on 16 June along with four African mine worker from the Zambesi area

[33] See the article Old Fort Hartley and the Cemetery at Hartley Hills goldfield under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[34] The Norton family were murdered about 17 June 1896. They were Joseph Norton, wife Caroline and baby daughter Dorothy with their nurse Miss L.M. Fairweather. Also the farm assistants James Alexander and Harry Gravenor

[35] See the article The June 1896 Mazoe Patrol skirmish with detailed accounts from those besieged and their Mashona attackers under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[36] A joint attack at the Alice mine at Mazoe may have been because it was at the junction of two territories, that of the Hwata-Chiweshe and Nyachuru territories

[37] White led a patrol of approximately 250 men to lift chief Mashayamombe’s siege of Hartley Hill. On his return to Salisbury on the south road he attacked Mupfumera’s kraal where the spirit medium Kaguvi was living. Kaguvi escaped moving south to Kaguvi Hill on the Umfuli (Mupfure) and White claimed a lot of loot at the kraal

[38] Chimurenga’: The Shona Rising of 1896-7, P415

[39] Frederick Eveleigh-de-Moleyns, 5th Baron Ventry. On 1 October 1896, he was redirected from Matabeleland with Robert Baden-Powell to command and train a new police force of 580 men in Mashonaland that Wikipedia states was completed by 1 December 1896 for which he was awarded the Companion of the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) although this seems rather a short period to train so many!

[40] Kaguvi and Fort Mhondoro, P43

[41] Fort Mhondoro on Pachikanikiso Hill had an initial garrison of 64 men, but after being attacked by Mashayamombe’s men on 8 – 10 February numbers were increased to 102 men, but it was in an unhealthy area and Fort Mhondoro was abandoned on 12 March 1897 by the remaining force of 24 men and superseded by Fort Martin on the north bank of the Umfuli and close to Mashayamombe’s kraal

[42] Beach writes (P44) that de Moleyns received their most useful information on Kaguvi from chief Mashayamombe himself

[43] Chimurenga’: The Shona Rising of 1896-7, P415

[44] Kaguvi and Fort Mhondoro, P36

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: