Thetford Game Reserve Rock Art Site

- How the trance dance served a community healing function in Late Stone Age community life illustrated through rock art paintings from a rock art site at Thetford Game Reserve, central Mashonaland, Zimbabwe

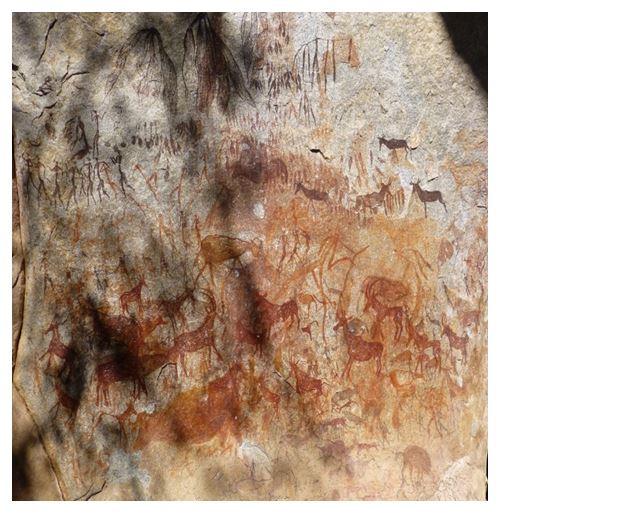

- The features of this site include the pristine paint quality of sections of the rock art panel, the clarity with which the trance scene is depicted, the high number of roots and plants featured by the artists (40% of the total images) and the first reported use in Zimbabwean rock art of a natural physical feature in the granite rock surface as a deliberate and dramatic part of the trance scene composition.

From Harare head north on the (A11) Mazowe road. Distances are from the road toll: 6.1 KM turn right on to the Christon Bank road. 10.9 KM ignore turnoff to right, 11.84 KM turn right onto gravel road signposted for Thetford, drive to the hill summit and then road descends into the valley, 15.3 KM cross Mazowe Bridge, 15.7 KM turn left at T junction, onto narrow tar road, 16.9 KM reach Thetford entrance.

Note all activities, including game drives, need to be booked in advance.

GPS Reference: 17⁰35′26.86″S 31⁰03′12.61″E

Website: www.thetfordgamereserve.com

Background to the rock art in Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe has one of the highest concentrations of rock paintings in Africa; they occur in almost all of the 150,000 sq. km of granite areas within Zimbabwe and appear in shallow shelter sites and under large granite overhangs. Sometimes the rock paintings are called “Bushmen paintings” but this term has largely fallen into disuse as inaccurate and derogatory. The Archaeological Survey of Zimbabwe, which began the system of recording sites in the 1960’s, has recorded thousands of rock art sites over the country, but there are likely to be many more.

The rock art site described is on Thetford Game Reserve, north of Harare in the Mazowe Valley. Thetford Game Reserve stocks many of the animals such as kudu, giraffe, sable, buffalo, rhino, zebra, and eland that would have roamed the area when the stone-age hunter-gatherer artists painted at this site amongst the granite kopjes. The area is also rich in other historical, archaeological and cultural sites, such as iron-age furnace sites on near-by Surtic farm[i].

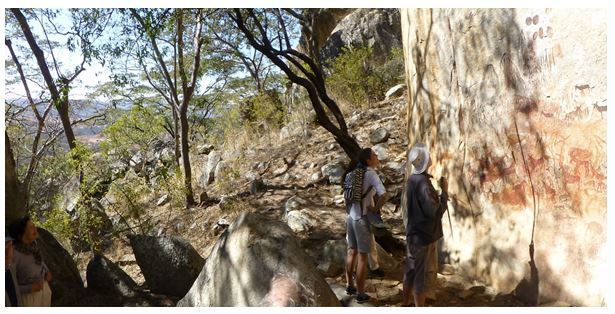

As the above photo of the Thetford Game Reserve rock art site shows, Zimbabwe’s rock paintings are often on exposed shelters within the granite kopjes and are barely sheltered from the rain, wind and sun. Natural damage from these elements fades the paintings and further actual damage is caused by water run-off and from the urine stains of the rock hyrax, known locally as “dassies, or rock rabbits” which live in these rocky habitats. This makes the rock art of Zimbabwe completely unlike the rock paintings of France and Spain and the sites at Lascaux and Altamira, best known for the bulls, bison and horses, which are hidden away deep in caves and largely inaccessible.

The artists

The paintings were skilfully drawn on the granite faces by the late Stone Age hunter-gatherers who lived in southern Africa from about 13,000 years ago and in Zimbabwe until the arrival of the early Iron Age era, beginning about 2,000 years ago. Today the nearest descendants of the artists, the !Kung San, live in Botswana.

Subjects portrayed in the paintings

In general, almost every animal encountered in Zimbabwe has been drawn on the rock art sites, along with scenes of hunter-gatherers engaged in different activities from hunting and dancing to camp scenes. More rarely painted are birds, fish, insects and reptiles, such as crocodiles. Other objects painted include trees, roots and abstract shapes called ovoids or formlings which are unique to Zimbabwe and not found in the rock art of South Africa.

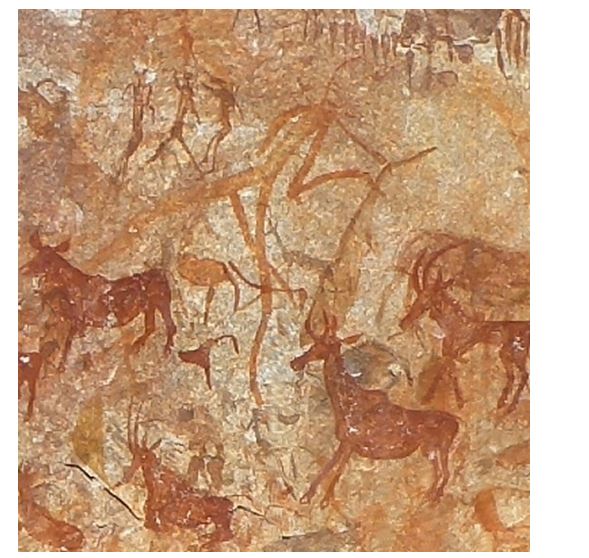

The range of animals painted at the Thetford Game Reserve rock art site includes not only the more common animals, such as kudu and sable, but also elephants, rhinoceros, zebra, sable, giraffe and warthog and bush pig.

A brief background to San cultural philosophy

Modern societies like ours tend to separate the spiritual aspects of our lives. For instance, we go to Church to pray, the Doctor when we feel ill, join a walking club for companionship, or take a “city break” to enjoy new sights. To the San, this would have seemed quite alien, as there are no partitions in their spiritual lives, everything is interconnected in life and the means to achieve this was through the healing dance.

Richard Katz in his book Boiling Energy: community healing among the Kalahari San [ii]explains that the San believe that the spiritual world and their own earthly world are one, they are completely interconnected. The spiritual world would be inhabited by the dead relatives of the San, the gauwasi, who live in the sky with God and have everything they need, but who sometimes from loneliness through missing their relatives, come back down to earth and cause mishaps to humans, through accidents or sickness. The gauwasi aim is to have their earth relatives join them in the sky and this creates a real issue for the San in the form of a struggle between the living who wish to heal the sick, or injured, and the gauwasi, the spirits of the dead. The person who bridges these two worlds is the trancer, or shaman.

Katz states that it is through the trance process the trancers are able to contact the realm where the gods and the spirits of dead ancestors live. Sickness is a process by which these spirits, helped by the lesser god, try to carry off the sick ones into their realm. The spirits have various ways of bringing misfortune and death, such as “allowing” a lion to maul a person, or a snake to bite, or a person to fall from a tree (Marshall 1969[iii]) but the dance is where the spirits are most likely to bring sickness.

The healing dance

Over the past few decades, research particularly in South Africa by David Lewis-Williams[iv] using information collected by Dr Bleek in the 19th century and ethnographic investigations into the religious traditions of the last remaining hunter-gatherers in the southern Cape, as well as contemporary San in Botswana has been carried out by Katz, Biesele, Lee, Marshall and others.

This research has revealed that the spiritual focus of the hunter-gatherers culture was the healing dance and the trance state attained by certain individuals, known as trancers. In their trance state, the personal potency activated by the trancers was believed to be capable of healing sickness, controlling game and the weather, and also enabled them to communicate with the gauwasi and other bands of hunter-gatherers in the spirit world. Katz lists some of the activities that define the healing dance and establish its centrality and importance in San society:

- healing in the most generic sense is provided. It may take the form of curing an ill body, or mind, as the healer “pulls out the sickness”

- mending the San social fabric as the dance provides for a manageable release of hostility and an increased sense of social solidarity

- protecting the camp from misfortune as the healer pleads with the gods for relief from the Kalahari’s harshness

- the healing takes the form of enhancing consciousness as the dance brings its participants into contact with the spirits and gods

- the dance provides the training ground for aspiring healers

- it provides the healers with opportunities for fulfilment and growth, where all can experience a sense of well-being and where some may experience what westerners would call spiritual development.

- in dance the San find a vehicle for artistic expression

- from the dance, they receive a profound knowledge, as the healer reports on those extended encounters with the gods which can occur during especially difficult healing efforts.

- Katz states that the trance dance is the San’s primary expression of “religion,” “medicine” and “cosmology.” It is their primary “ritual.” For the San, the dance is, quite simply, an orientating and integrating event of unique importance.

Number of participants in a trance dance

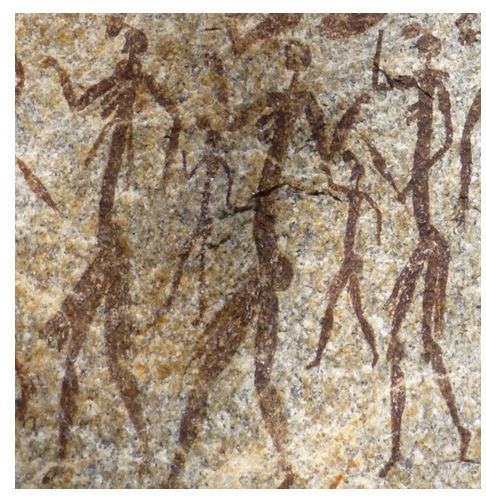

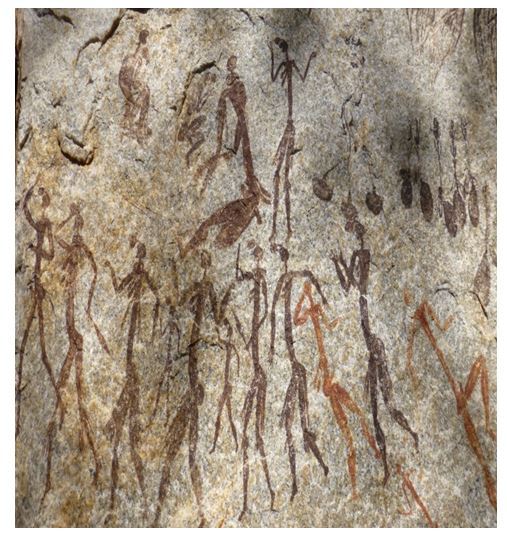

Katz observes from living amongst the San community that a large dance, in which several camps participate, includes about fifty to eighty persons. In such a large dance, fifteen to thirty women may be singing at different times. They are usually adult, joined by some of the more enthusiastic adolescents, as shown at Thetford site in the adjacent photo from the Thetford Game Reserve rock art site. The adolescent participants are shown as smaller versions of the adults, but otherwise identical.

About seven to fifteen men may be dancing at any one time, most of them young or middle-aged.

Smaller dances have fifteen to twenty persons, with seven to ten women singing and four to five men dancing. Perhaps one quarter of the female singers and two-thirds of the male dancers may be healers at one dance regardless of its size.

At large dances to celebrate a special event, Katz observed up to 200 persons at a dance which may go on continuously for several days. Two dance fires may be built, with singers divided up around each one, and the dancers circling both fires in a figure-eight pattern. The killing of a large animal, such as an eland, may motivate this kind of dance, or it may be a sudden sickness in the community, or the return of absent family friends, or a visit from relatives.

Dance equipment

Katz noted that very little special equipment was worn for the trance dance. Dance rattles (zhorosi) are used, made from dried insect cocoons with pieces of ostrich shell inside, strung on pieces of fibre. Usually a pair of rattles is used, one string being wrapped around each of the dancers calves. As the dancers move around the circle, the rattles give a distinctive staccato sound, which accompanies and accents the rhythmic texture of the dance.

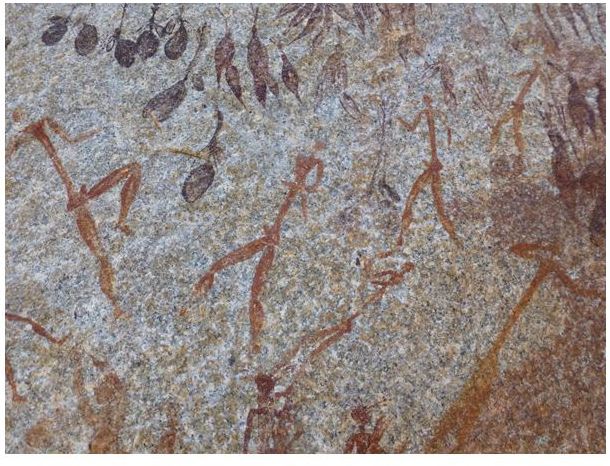

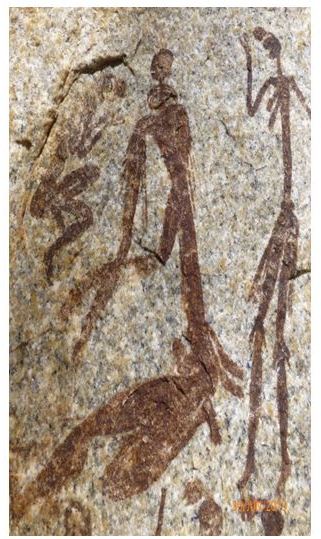

As can be seen from this photo of the Thetford site at least one woman wears rattles and carries a fly-whisk object. Both women wear aprons front and back and one has a tassels from her knees; the other below her breasts. Most dancers also bring their walking stick to the dance. This stick, which can also be used for digging roots and carrying objects, usually has a large gnarled knot at the top serving as a handle. The dancers use the stick to accent their dancing steps, or especially when fatigued, to support the as they continue to dance.

All the female dancers, the adolescents and the figure being healed wear an object that looks like a blob on their heads supported by a stem. Peter Garlake, the most eminent rock art researcher in Zimbabwe, in his book The Painted Caves [v]believes these shapes represent the release of a form of spiritual energy or potency.

The healing dance itself would last all night and includes every member of the community, plus the invisible spirits of the dead, the gauwasi, who are drawn by the singing and dancing and who stay in the darkness, outside the fire-light and try to shoot small, invisible “arrows of sickness” into people. The San believe that all members of the community have sickness in them, but through the spirits of their dead relatives the gauwasi, this sickness can turn into a real illness, or injury. The trancer then engages in a struggle with the gauwasi over the person.

The photo above is situated directly above the dancers and healer depicted on the Thetford site and may show the gauwasi crouched, preparing their “arrows of sickness.” Garlake suggests that the large elaborate arrowheads are a key indicator of trancing. Clearly arrowheads of this size were not used in hunting and thus they must have an alternative significance.

Elizabeth Marshall Thomas observed “that the women sit in a circle around the fire with their babies on their backs and sing the medicine songs in several parts with falsetto voices and clap their hands in a sharp, staccato rhythm. Behind them the men dance one behind the other and circle around slowly taking short, pounding steps in counterpoint to the rhythms of the singing and clapping. This is accompanied by the sharp, high clatter of rattles – made from dry cocoons strung together with sinew cords – that are tied to their legs”.

As the hours go by, the dancing along with the singing and clapping gets more intense as the healers in the group pound their feet. Lorna Marshall in The Medicine Dance of the Kung Bushmen[vi] says that “as the dance intensifies, the n/um or energy, is activated in those that are healers.” Katz also says “the singing of these powerful n/um songs helps awaken the n/um and awaken the healer’s heart; their heart must be awakened before they can begin to heal.” As the trancer dances, n/um, which is described as living in the stomach, heats up and begins to boil, then rises up the spine until it rests at the base of the dancers head.

At this point, after hours of dancing and hyperventilation, with the help of the women’s hypnotic singing and clapping, a dancer may enter a trance or half-trance state, !kia, where he/she may sweat, tremble and may bleed from the nose and later describe how they travel on their frightening mission into the spirit world. Fellow dancers will lead the trancer from the dance circle to sooth and massage him/her with rendered animal fat.

To the right of the above scene, the male dancers are painted in a different shade of ochre and are scattered around in a frenzy of dancing movement and facing different directions.

The photo shows the key event, the trance dance in progress with the women encircling the trancer. The women are portrayed in upright postures all facing the same direction in procession; note the woman on the far right clapping, unlike the other participants, her fingers are drawn.

At the centre of the scene, the trancer crouches with a knee bent and his buttocks resting on his heel, the other leg outstretched, dominating the frieze with his size and elongated limbs. Interestingly, the entire trance scene appears to have been done by a single artist as the style of painting is very similar with the consistent use of two shades of ochre. The women and trancer are in a darker ochre, there is a trace of orange in the lighter ochre used to paint the men.

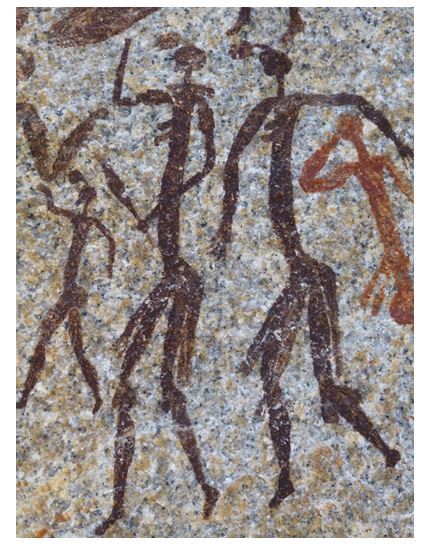

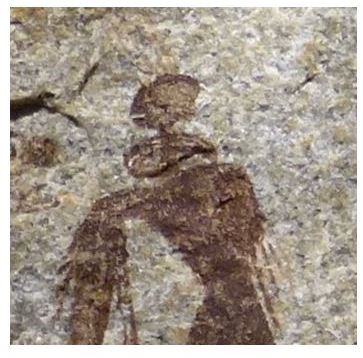

Peter Garlake, in his book The Hunter’s Vision,[vii] describes how hoops drawn on either side of the neck are intended by the artists to portray the enlarged arteries of a shaman in trance and this rare image is seen very clearly in the photo enlargement alongside of the trance.

Katz quotes a trancer “You dance, dance, dance, dance. The n/um lifts you up in your belly and lifts you in your back and you start to shiver. N/um makes you tremble, it’s hot. Your eyes are open, but you don’t look around; you hold your eyes still and look straight ahead. But when you get into !kia, you’re looking around because you see everything, because you see what’s troubling everybody. Rapid shallow breathing draws n/um up. What I do in my upper body, the breathing, I also do in my legs with the dancing. You don’t stomp harder, you just keep steady. Then n/um enters your body, right to the tip of your feet and even your hair. ”

Rupert Isaacson in The Healing Land [viii]describes the process of moving from one state to another “they sometimes dance themselves into trance, sometimes screaming in pain, and at other times laughing or singing.” This article may refer to the masculine, but the feminine equally applies.

The trance state, !kia

In the trance state the dancer may feel like he is sleepwalking, being stretched out, or flying. In trance the dancers may jump, run or somersault, even tremble and convulse. The feeling of potency, achieved in the trance state is central to the spiritual belief of the San and these sensations experienced in the trance state can be directly related to the Thetford Game Reserve rock art site.

The experience of !kia is often compared by the San to dying and being reborn and accordingly, there is a real fear of death, with only the dying taking place with no rebirth. Thomas Huffman[ix] says the San use the metaphor “to die” to signify trance. The San word for dying is the same as that for entering deep trance and trance scenes are often associated with dying animals and the symptoms of sweating, hyperventilating, gasping for air, bleeding from the nose and finally collapsing into unconsciousness are analogous to both experiences. This metaphor has been extensively researched by Lewis-Williams within a South African context.

As Katz tells it, in their ordinary state the !Kung do not argue with the gods, such is their respect. But in !kia, the !Kung are able to enter the realm where the gods and the spirits of dead ancestors live where the healers in their trance state express the wishes of the living by entering directly into a struggle with the spirits and the lesser god.

When a person is seriously ill, the struggle becomes intense. The more powerful healers sometimes travel to the great god’s home in the sky, bringing the confrontation directly to the source of the illness. The San say that the traveller’s soul makes that journey at the greatest risk to the healer’s very life. Healers undertake such a terrifying journey because they want to rescue the soul of a sick person from the god’s home and bring it back to their own camp.

On their return, these powerful healers may describe the god’s home, at times in great detail, as well as recounting their own struggle for the sick one’s soul. If a healer’s n/um is strong, the spirits will retreat and the sick one will live. This struggle is at the heart of the healer’s art and power.

The power or potency of n/um could be attained by any in the San community who participated in the communal dance activities. Dancers who attain trance state and out-of-body experiences on a regular basis are termed shamans. Katz states that dancers can only heal when they learn to control their boiling n/um, or energy. Then they learn to “pull out sickness.”

The photo above from the Thetford site shows four male figures below the trancer. One appears to have large animal ears and wavy arms; the second is in a wide-apart stance and has one raised wavy arm, the third has a V-shape object on his shoulder and a line rises vertically from his head.

All of these features are indicative of trance dance. The fourth figure is four times larger and painted in orange ochre. One arm is much longer than the other, the feet are attenuated and the torso is headless, although several lines flow from the neck. The elongation of limbs has already been discussed within the context of trance.

Trance dancing could also be about healing the whole community, as well as individuals. Social tensions between individuals and groups could be healed through trance dance. In trance, a dancer’s spirit may leave their body and travel to distant groups of hunter-gatherers, or control game, or lead “rain animals” to dry areas.

Marshall Thomas writes about trancers healing “star sickness” as a force which can afflict groups of people and become the source of jealousy and quarrels. The trance dance will release any hostility and bring together groups of people.

The effect of n/um has been portrayed on numerous rock art sites in Zimbabwe (e.g. Zombepata cave) as streams of apparently random stippling made up of dots, dashes and arrowheads. In the past these were interpreted by researchers as representations of reality such as rivers, flocks of birds, swarms of bees, smoke, pollen, etc. Garlake maintains to the San community they are powerful representations of energy in the form of n/um.

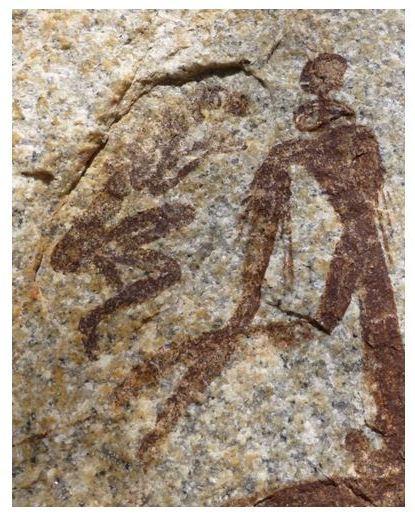

The curing state, Twa

Alongside is another enlargement of the frieze at Thetford site. Curled into a small natural depression in the granite, a sick person is lying with knees drawn up. Bending over the patient is a kneeling shaman whose enlarged arms are shown over the patient. If the healer is vigorous enough, and if his n/um is powerful enough, the trancer then cures, twa, by fluttering his hands over the patient and then puts his face to the patient and inhaled the sickness into himself and exhales n/um into the patient. This may be one of the clearest depictions of trance healing in Zimbabwe.

The struggle may be intense with the trancer’s soul having to leave his body to plead with the Gods and the spirits for the life of those who may be ill. In this state, he may be unconscious in trance. If he succeeds, then with a high pitched cry, the trancer expels the sickness from the patient’s body, or the community, back into the darkness.

In the trance state, brought about through long sessions of communal dancing, from which the trancers enter a hallucinatory state, individuals may bleed from the nose; this blood is considered potent and may be rubbed on a sick person to promote healing. Scenes of humans bleeding from the nose are relatively common in Zimbabwe rock art.

According to Marshall, San healers may use plant substances which contain n/um. These plants are ground to a powder, mixed with marrow, or fat, and put in an empty tortoise shell, several inches long. Healers place a burning coal into the mixture, wafting the smoke, which carries n/um, toward the patient.

The skill of healing was open to all the community in San culture

Katz states “the healing dance is open to all and public, a routine cultural event to which all San have access. To become a healer is to follow a normal pattern of socialization.” Healing is not a reserved profession for those with special powers. Essentially the training of both men and women healers is the same, especially the process of receiving n/um. Most males and more than a third of the women try to become healers. A group of five or six year olds may perform a small “healing dance” imitating the actual dance with its steps and healing postures, at times falling as if in !kia. Through play, the children are modelling as they grow up, they are learning about !kia.

Thomas Dowson reports that despite the long and painful process, many San wish to heal and by the time they reach adulthood, about half of men and a third of women become healers through trance.

Trancing and the rock art sites.

Trancers acquire a vision to see supernatural animals, ghosts, gods, sickness and n/um. However, they do not see themselves as set apart from the community by their powers. They shared their trance experiences of n/um, !kia and twa and the spirit world through painting on the rocks. The rock art sites of Zimbabwe represent the interface between the earthly world and the San spirit world, a theme that is well illustrated at the Thetford site.

The rock face as an entrance to the spirit world

J.D. Lewis-Williams and T.A. Dowson state “there is neuropsychological and ethnographic evidence that suggests that San shamans visited the spirit world via a tunnel that, in some instances, started at the walls of rock shelters”. They argue convincingly that the walls of rock shelters were in some sense, a “painted veil” suspended between this world and the world of the spirits.

At many sites the authors had noticed features of the art itself that suggested the rock face was significant and part of the picture ”contrary to western notions of the painted canvas as a Tabula rasa (i.e. a blank slate) Images of animals and people appear to enter and exit cracks in the rock, or steps in the rock face led to the notion that the spirit world lay beyond the rock face and the paintings on the rock face were therefore already set into a shamanistic context”.

They give a number of examples to illustrate the principal ways in which the San artists used the rock face to give the impression of depictions entering and leaving the wall of a rock shelter and conclude, amongst other things, that the artists themselves were shamans and that they were depicting their own spiritual experiences and insights.

In support of this, the rock face at the Thetford site provides a very real example of being an active part of the vision the shaman artists are attempting to portray. The patient at the heart of the healing process lies huddled within a natural circular hollow within the rock face. The author is not aware of any other reported examples in Zimbabwe of the artists actually incorporating the physical features of the rock surface into their art.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the staff at Thetford Game Reserve, especially Mark Brightman, who were very helpful and Dennis Pascall who assisted with the image count.

[i] Martin D. Prendergast. Early Iron Age furnaces at Surtic Farm, near Mazowe, Zimbabwe. SAAB Bulletin 38: 31-32. 1983

[ii] Richard Katz. Boiling energy: community healing among the Kalahari Kung. Cambridge, Mass. Harvard University Press. 1982

[iii] Lorna Marshall. The Medicine Dance of the !Kung Bushmen. Journal of the International African Institute 39: 347-381. 1969

[iv] J. David Lewis Williams. Believing and Seeing. Academic Press. 1981

[v] Peter Garlake. The Painted Caves, an introduction to the Prehistoric Rock Art of Zimbabwe. Modus Publications. 1987

[vi] Lorna Marshall. The Medicine Dance of the !Kung Bushmen. Journal of the International African Institute 39: 347-381. 1969

[vii] Peter Garlake. The Hunter’s Vision, the Prehistoric Art of Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe Publishing House. 1995

[viii] Rupert Isaacson. The Healing Land. Geographical 73.7; 7 (2001): 53

[ix] Thomas N. Huffman. The Trance Hypothesis and the Rock Art of Zimbabwe. South African Archaeological Society. Goodwin Ser. 4. 1983