The Native Commissioner – the early years

Introduction

Prior to 1894 the British South Africa Company (BSACO) had appointed magistrates to uphold the law. However after the invasion of Matabeleland In 1893[1] the BSACo established the Native Affairs Department by Order in Council to be responsible for the administration welfare of black Africans living on tribal trust lands initially in Matabeleland.

The BSAC recognised a system of administration was necessary to replace the amaNdebele system that had been ruled by Lobengula although initially their replacement was quite informal with a Chief Native Commissioner appointed in Bulawayo with Native Commissioners and Assistant Native Commissioners under authority.

To enforce their authority the Matabele Native Police (MNP) was raised and placed under the overall command of the Chief Native Commissioner of Bulawayo. The MNP role was to act as the ‘eyes and ears’ of the administration and was also responsible for law enforcement, the labour recruitment on the mines and farms and tax collection. This made them extremely unpopular and was cited by the amaNdebele as one of the causes of the Matabele Rebellion (Umvukela) Many deserted the MNP in March 1896 and joined the amaNdebele in the uprising.

In 1895 this same system of local government was extended to Mashonaland.

I have kept the term native where this was used in a colonial context but elsewhere use African or Mashona or amaNdebele.

Early years in the BSACo’s administration of Matabeleland

With the occupation of Mashonaland in 1890 the BSACo needed to establish its authority and set up a system of administration and in the absence of experienced staff it was almost inevitable that the chartered company would need to rely on amateurs for its administration.

However, as Phillip Mason writes, “where there are very clear class differences, amateur rulers tend to confuse the interests of their class with the ends of justice”[2] and were unlikely to be impartial between their own class and the Mashona.

After the invasion of Matabeleland in 1893 and the death of Lobengula in early 1894 the same administration needed to be set up in Matabeleland. Native Commissioners and magistrates were appointed with the same kind of duties as in other British colonial territories. They were meant to be an impartial authority, to be accessible, to receive petitions and to take steps to right any injustice or wrongs. They inquired into disputes regarding chieftainship succession and tribal boundaries and settled water disputes. They had the same civil powers as a magistrate. They were required to register the inhabitants of their district and collect taxes.

Mason goes on to say this, “is in accordance with the ideal of the British district officer in other parts of Africa…and at first there was not much difference in practice either between the Rhodesian sub-species and his colleagues…

…The first native commissioners were picked whenever a man who seemed suitable became available. Doctor Jameson chose a man he liked from the counter in a store or the desk in the telegraph office. They were sent out with a few instructions[3] and a wide opportunity to create a tradition. In their diaries and letters, one can savour a life that was very leisurely, unhampered by too much correspondence, or by too much formality.”[4]

Once the situation settled down, better quality candidates were picked, many coming from the Natal native administration, where they has learnt Zulu and therefore could pick up Sindebele quite easily.

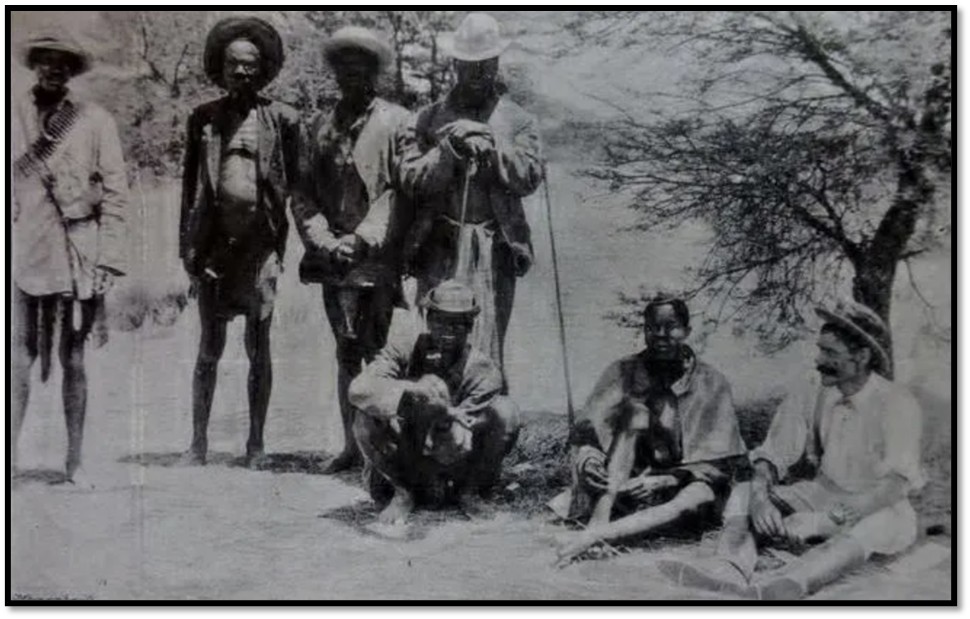

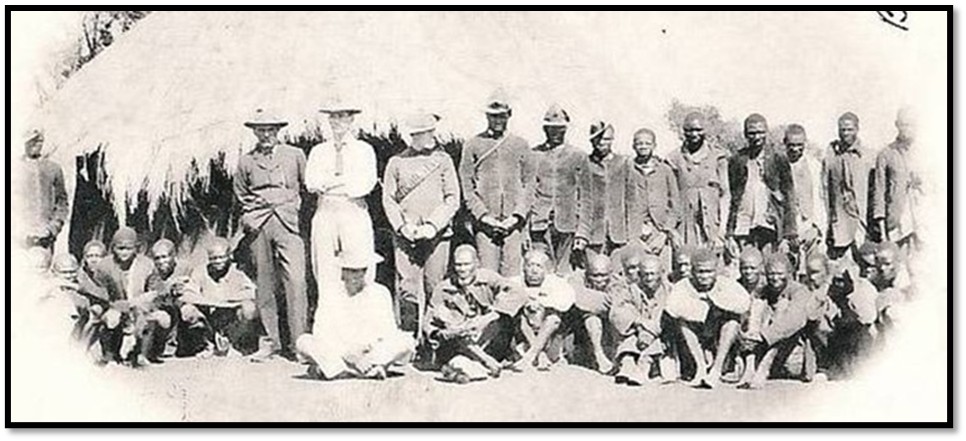

NAZ: Herbert Taylor talking with the amaNdebele Chiefs during the indaba negotiations at the close of the Matabele Rebellion (Umvukela)

The hierarchy of the Native Affairs Department and more background

The hierarchy within the Native Affairs Department was as follows:

- Administrator in Council

- Secretary for Native Affairs

- Two Chief Native Commissioners (Matabeleland and Mashonaland)

- Chief Native Commissioners were Native Commissioners (tribal districts and sub-districts)

- Assistant Native Commissioners

About 1907 a new layer was added, superintendents of natives, who were placed in charge of divisions, later styled ‘circles’ to ensure a greater degree of decentralization.[5]

On 1 October 1894 , Herbert John Taylor[6] and Johan Colenbrander were appointed as Native Commissioners and by 1 May 1895, Taylor became the Chief Native Commissioner for Matabeleland.[7]

The two positions of Chief Native Commissioner in Mashonaland and Matabeleland were amalgamated on the 1 November 1913 with the role of commissioner for Matabeleland abolished. HJT became chief native commissioner for all of Rhodesia and moved from Bulawayo to Salisbury where his "African name" of Msitela or Musitera (Mister Taylor) became the synonym for "head office."

In 1962 the Native Affairs Department was renamed the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Following the ranks of the Colonial Service, the Native Commissioners were renamed District Commissioners.

The Ministry of Internal Affairs encompassed fifty-four districts throughout Rhodesia, each led by a District Commissioner (DC) with an Assistant District Commissioner (ADC) as second in charge and a staff of white and black members who were responsible for vast and remote rural areas. Provincial Commissioners were appointed to coordinate local government in areas such as Mashonaland Central.

Militarily the administration was supported by the British South Africa Police (BSAP) but during the 1970’s the Ministry of Internal Affairs role became para-military as law and order broke down and the staff were required to defend themselves and the public under their charge. All staff underwent military training, patrolled their districts gathering intelligence and manned the protected village (PV) system.

Duties of the Native Commissioners

Native Commissioners in Southern Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe) were officials in the Native Affairs Department, established by the British South Africa Company in 1894 after the invasion of Matabeleland and death of Lobengula.

- Their primary responsibility was to administer the tribal areas and oversee the welfare of the black African population living on these lands. Their key roles were:

- Administration: Native Commissioners were responsible for the day-to-day administration of their designated districts and sub-districts.

- Welfare and Development: Their duties included a focus on the welfare and development of the black African rural population.

- Judicial Powers: Notably, Native Commissioners possessed significant judicial power, including the ability to try offenses committed against themselves. This was considered a departure from British legal principles by some.

- Law Enforcement: They played a crucial role in maintaining law and order and were assisted by the Matabele Native Police (MNP), an organization placed under the Chief Native Commissioner of Bulawayo. The MNP also handled tax collection and recruitment of labour.

- Local Level Government: Native Commissioners provided a local level of government throughout Rhodesia.

Notable Native Commissioners

Herbert John Taylor: Appointed as one of the first Native Commissioners in 1894 and later became Chief Native Commissioner.

Johan Colenbrander: Appointed as a Native Commissioner alongside Taylor.

Lionel Powys-Jones: Appointed as Chief Native Commissioner in 1947, he was one of only 16 people to hold this position between 1894 and 1978 and was honoured with a C.B.E.

Impact of the Matabele (Umvukela) and Mashona Rebellions (First Chimurenga)

Marshall Hole lays down the chartered company’s immediate task following the surrender of Kaguvi in October 1897. “The company was in a position to devote its attention to the settlement of the natives in areas where they could be kept under supervision and deprived of the opportunity for hatching further plots. Large tracts of country were selected for reservations…the constitution of the native department was overhauled and commissioners of proved capacity sent to all the principal centres of population.”[8]

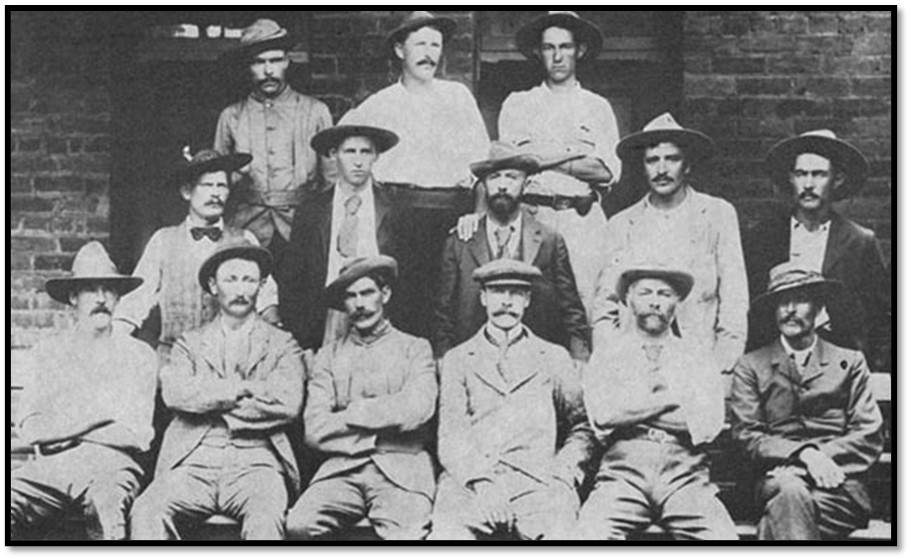

NAZ: Native Commissioners in 1896. Back (L-R) T. Hepburn, D.H. Moodie, C.G. Fynn

Middle (L-R) E. Armstrong, B. Armstrong, C.B. Cooke, V. Gielgud, T. Fynn

Front (L-R) H.M.G. Jackson, W.E. Thomas, H.J. Taylor, Capt. the Hon A. Lawley, J.W. Colenbrander, unknown

The role of Native Commissioners in Rhodesia was complex and often controversial

While they were tasked with the welfare of the African population, they were also instrumental in enforcing colonial policies, some of which were seen as restrictive or exploitative.

The Patriot, that vitriolic and prejudiced newspaper, can always be counted upon for a biased opinion! In an article on ‘the notorious native or district commissioners[9] describes them as “the ultimate colonial master bad guy” who were the Africans “worst cruel ‘headmasters’ in what were called African Tribal Trust lands where those colonial commissioners generously used the big stick against them putting the fear of the white man in all of them.”

The article adopts the line that the native commissioners replaced Lobengula “and so into the empty seat was thrown the native commissioner who to complete the coronation exercise was also referred to as ‘nkosi’” and are described as the “chief commissars during the cutting up of our country’s land into black and white areas.”

The article states, “Herbert Taylor when he eventually became the Chief Native Commissioner of the entire country was the chief consultant during the crafting of the scandalous Land Apportionment Act of 1931, which became, the ‘most important law governing land distribution in Rhodesia’ at the time.”

How development of native department policy gradually evolved

As Chief Native Commissioner Herbert Taylor founded the new system of native administration in Matabeleland on the basis of a restoration, as far as possible, to the chiefs, of the authority they had in Lobengula's time. This was a promise made by Rhodes at the Indabas with the chiefs and included in the 1894 and 1898 Orders in Council when he paid tribute to the immense value of the assistance of the chiefs.

In 1902 he stressed the native department's duty as "guardian and protector of the native" but by 1905 the concept of development began to appear - "development of stock farming and agriculture will lead to gradual assimilation of civilisation in other phases" - followed by more precise ideas such as the provision of health centres, "will do more to lessen the evils of witchcraft than any measure of legislation." Prof. M. Gelfand in Tropical Victory, 1953, wrote that, "the earliest references to ill health in the natives came from the native department, not from the medical profession . . . these astute observers would not allow the matter to be ignored" and it was "to result finally in the provision of an organised medical service in the Reserves."

In 1903 Taylor accompanied Sir William Milton,[10] as adviser on native affairs, to the South African Conference called by Alfred Milner, in an effort to bring about some kind of common native policy among the then four colonies.

However by 1909 Taylor had detected a gradual breaking away from the tribal system, the emergence of a "transitional state" when he urged that "it would be mistaken policy to attempt to arrest this individualistic tendency…it would be unwise at the present stage of development to abolish this system (of tribal control) as a means of government." and "it is the duty of Government to foster this desire for education that he may take his place as a useful citizen."

The land question was considered from an early stage

By 1911 Taylor was declaring, "developing the native reserves is a matter which should receive the earnest consideration of the Government . . . present methods adopted by natives are very wasteful, and the land soon gets worked out . . . also sanitation should be taught."

In 1912 Taylor stated, "land tenure is the root of the native problem" and proposed a scheme of gradual individual tenure because, "in a few years it is doubtful if the Reserves will be able to cope with the rapid increase of stock."[11]

In 1921 in response to Taylor’s 1919 reports, Britain established the Morris Carter Land Commission with Taylor as a member, probably the most knowledgeable member, of this Commission and following the Commission’s report in 1925 came the Land Apportionment Act, 1931. This set the legal pattern of possessory segregation and created Native Purchase Areas, Taylor's object for almost twenty years.

Modernising the native department

Taylor appointed in 1920 the first Director of Native Development (H.S. Keigwin) and also established a government industrial and farm school at Domboshava, followed by a second at Tjolotjo in Matabeleland and In April 1927, he appointed the first full-time agriculturist, the beginning of the training of African agricultural field officers.

His control for almost thirty years over native administration and untiring ideas to promote pioneering efforts in the fields of African health, education, agriculture and land tenure were recognised when he received a knighthood from the King in 1923, the same year the BSA Company gave way to a locally elected Legislative Council.

His final three years after the age of retirement was devoted to the formation and running of native councils. He had studied both South Africa's and Kenya's experience and considered that they should be introduced gradually on a voluntary basis and that it was time to prepare the groundwork, "the attempt to graft anything in the nature of local self-government before they are ready and willing to accept it is bound to fail." The principle of native councils[12] in June 1927 had been accepted after much Parliamentary debate.[13]

In December 1927 at the first conference of all native commissioners in Salisbury, Sir Herbert Taylor referred to "the essentials of native administration" and stressed the personal factor for commanding confidence.

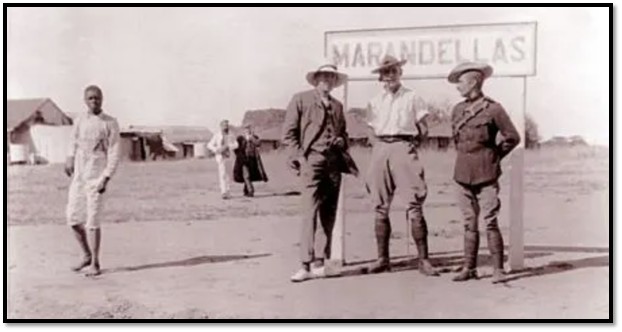

NAZ: Magistrate (?) Native Commissioner and BSAP Officer at Marandellas

Some early experiences of native commissioners

W.E. Scott reported from Hartley in 1897. “A lion came into Mr Gaynor’s kitchen and killed a houseboy named Mombe while the family were at dinner. Locusts are bad across the River {Umfuli, present-day Mupfure] and the remedies suggested by the agricultural department are of no avail. A meeting has been held to appoint Banquira chief of the Mashiangombi. All the headmen of the tribe were present and many others. After asking whether they all still wanted Banquira, I told them you had approved their choice. And Banquira was appointed amid apparent satisfaction from those present. I impressed upon Banquira that he was a servant of the government, that, we looked on him as such, and that if he did wrong he would be punished as one of the government servants; he was also to understand that he was to render all the assistance in his power to the authorities.”[14]

In September Scott was reporting that the Mashona, “Strongly object to build on account of the clayey nature of the soil, unsuitable for their favourite crop ropoko [rapoko – finger millet]…All the ground of the red clayey kind is not liked by the Mashonas. It is the white sandy soil covered with Msasa trees which the Mashona is so fond of.”

On 6 September he drafts a report following his return from a seven-day patrol on which he had seen “very few natives.” This is hardly surprising since the Mashona Rebellion (First Chimurenga) was barely over.

On the 5th of October he went off on another longer patrol and states in his report that it was not until the 19th of October that he, “first came across any natives in the Hartley district; they were Makorekore, very black, well-built people speaking a dialect of Mashona.” For two days, he lost the rest of his patrol and was reduced to eating locusts, on the third day, without food, he came to a native kraal and had a “welcome feed of native corn porridge.” He returned to Hartley on the 2 November saying, “with very little shoe leather left to his feet.” but knowing a great deal more about his district. The local natives, he reports, are few in number and quiet, but “very wild running like buck when you come across them in the veld.”[15]

The native commissioners in their difficult role as suppliers of native labour

Mason remarks that it was an odd double life that the native commissioner lived, alternating between lonely patrols and the small circle of well-known faces back at his quarters. He probably knew those firing at friendly natives and he knew the farmer who complained because his labour had run away but was known to treat them harshly.

David Mooney, one of the first murdered victims of the Mashona rebellion[16] recorded that in 1895 a farmer complained that eight of his workers had run away. On investigation it was found two had been thrashed and another two had not been paid their wages. In another area he recorded he found 102 huts scattered in the bush. He wrote, “If I can't get any tax from them next time I go, I suggest moving them to a spot on the Sarui River…where they are at present, they are not the slightest use for labour.” He found 448 more huts than his predecessor and supplied 800 natives for labour but complained that “the daily demand for labour makes it impracticable for me to absent myself from Hartley for long.”

He reported, “the natives of this district are unwilling to work. If they're hear I am in want of labour, they desert their kraals for weeks and stay in hiding till they hear I've got what I wanted...A man comes in wanting boys and generally wants them at a day's notice or less and thinks himself badly treated if I tell him he must wait five or six days…When I go out for a few days, I find half a dozen men wanting boys when I get back.”[17]

Mooney's letters are full of Information. The natives in 1895 are peaceful and civil towards europeans, yet distrustful. “They would like them very well if they had not to work for them.” There is no serious crime. “The Mashona are a very moral race.” There is, “no such thing as a chief in my area. Their subjects will in no case go to these so-called chiefs; all bring their grievances to me.”

He adds that 10 shillings a month is a “ridiculously low wage” and he is, “not at all surprised they are unwilling to work; after working 30 days they only earned 10 shillings for which they can buy 24 lbs of meal - just enough food for one adult for 12 days. A family of two would starve on such earnings. They all say they can feed better by collecting roots, fruits and herbs than by earning; I should be very glad were I to receive orders to supply no labour under 20 shillings a month.”

His report on the 24 May 1896 mentions the rumour of a plot by Matabele and Maholi to rise and kill europeans; he attaches no importance to it, the natures being very quiet and civil. The next entry is dated the 19 February 1897 with Scott being then in charge and still inquiring into Mooney's murder.

The farmers in the early days “regarded native commissioners as hopelessly biased in favour of the natives; even the 1915 Native Reserves Commission classed them along with missionaries, as partial to natives.”[18] The African population however probably regarded native commissioners as biased in favour of the farmers.

A chronic shortage of labour for farms and mines continued to exist

In 1905 it was calculated that 25,000 labourers were required; by 1910 the mines wanted 39,000 and the farmers 23,000 labourers.[19]

Mason writes that if you scanned any newspaper of the time, there as many letters on the shortage of labour as all the other subjects put together. “The reason is very simple; settlers wanted labour and Africans did not want to work. They had been used to an economy in which money played no part; they saw no reason for change.”[20]

Chief Commissioner Taylor not long after the rebellion told the amaNdebele that they, “must understand that this was now a white man's country…He did not expect all to turn out to work…They would please the government very much if they only went to work for three months and had nine months to rest…”[21] This was a gentle persuasion, but not enough.

He could be more unambiguous. “There could be no forced labour; the government would not allow it. At the same time, he wished them to go out willingly…He would have the Indunas realise that they were government officials. They were paid so much and in return the government looked to them to assist in supplying labour. They must see that the boys turned out to work.”

Neville Chamberlain in London thought this might be a form of compulsory labour and asked for an explanation. The BSACo replied, “A system more judicious, more humane in intention, and better guarded against the evils of forced labour on the one hand and uncontrolled competition on the other, could scarcely be conceived.” They thought “it would be exceedingly discouraging to humane and experienced officials like Mr Taylor…if the spirit and purpose of their dealings with the natives were inadvertently misconstrued by the Imperial authorities at home.”[22]

Meetings of local farmer associations called on the native commissioners to be more active in getting them labour.

However, the BSACo administration ruled that, “under no consideration whatever is any compulsion to be exercised” and “when messengers are dispatched to seek labourers, they are not to be given any powers whatsoever. They are simply to deliver your message through the chief or headman and return with such as are willing to work.”

On the other hand they advised that native commissioners were to lose no opportunity. In pointing out the advantages of work. These contradictory messages confused both messengers and chiefs.

In 1900., Captain Lawley, Administrator of Matabeleland, reported that native messengers “sent to connect boys” had used force. “The offenders are now in prison awaiting trial“ and this “will be ostensible proof that the government will not sanction anything in the way of force being used in the collection of labour.”

The Resident Commissioner wrote in 1901, “while undoubtedly strong moral pressure is brought to bear on the natives to induce them to work in the mines and elsewhere, no case of actual compulsion has come to my knowledge.”

One of the difficulties was that the mines paid higher wages and wanted labour in bulk. The farmers paid lower wages and wanted individual farmhands who would stay with them. An agreement with the Witwatersrand Native Labour Association (Wenela) was that they would provide Southern Rhodesia with 12.5% of the labour recruited in Mozambique, but by 1903 this had produced ‘not a single native for Rhodesia.’ The same organisation in Southern Rhodesia recruited from Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) and Nyasaland (Malawi)

As Mason writes, throughout the period the native commissioners walked a tight-rope with the colonial office always insisting they should be impartial and the farmers and miners anxious that he used his influence to induce natives to work.

The native commissioners role in the recruitment of Labour came to an end in 1903 when the Rhodesian Native Labour Bureau came into existence for the purpose of getting African workers to sign up with white employers.[23]

Native Commissioners and the collection of tax

In 1900 the BSACo proposed to change from a hut tax to a poll tax and that every male native capable of working should pay an annual tax of £2 unless he had been in employment for four months the previous year. After three years of continuous employment he was exempt paying tax forever.

Therefore assuming a male worked for four months on an average of 30 shillings a month, the tax would be paid after two months and at the end of the period he would have £4 or £5 to take home. However in 1903 the inspector of native compounds reported that a woman cultivating an extra acre could earn more money in a month than he earned in three months on the mines.

The final agreed amount was ten shillings, so natives were taxed, mainly to make them work and the rate of tax was kept lower by the imperial government than Rhodesian employers would have liked.

Native Commissioners and the law

In the early days, native commissioners duties also included those of a magistrate. In a 1910 proclamation, native commissioners were given the powers to try only cases where Africans were involved. They could also deal with criminal cases, in which the accused was an African, and thereafter native commissioners began to play a major part in the country's judicial system. Any native dissatisfied with local decisions in their villages, or angry at being accused of witchcraft by fellow tribesmen, could go to the native commissioner’s courts to seek justice.[24]

At the bottom of this legal and administrative hierarchy were the chiefs who were given very limited powers by the legal system. Direct rule of law through European administrative officers who had received legal training seemed the best choice.

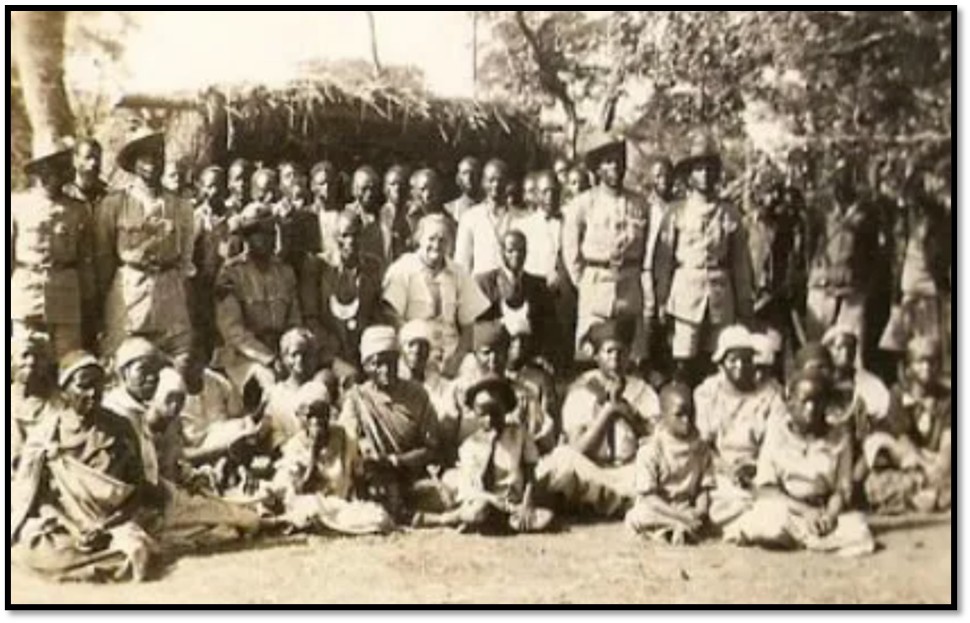

NAZ: Native Commissioner, Chiefs and Native Department employees and families

The BSACo’s policy toward Chiefs

Native Commissioner Drew at Victoria wrote in December 1896 for general guidance on the policy towards chiefs. He felt the power and influence of paramount chiefs, now freed from the danger of the amaNdebele were, he thought increasing, and he would like to back them up in all they do. So far, however, he has only “encouraged them to exercise their power over such of their people as want it and so far as the law permits.” However, “if the more common disputes could be dealt with by the paramount chiefs, we should be saved a considerable amount of trouble…of course he would need watching…white police would be needed to patrol the country and arrest other offenders. (e.g. europeans) and they would be native police under the native commissioners for the natives.”[25]

Mason puts his finger on the regulations at the time. “The native commissioner shall control the natives through their tribal chiefs and headmen” went the regulations, but in the next paragraph the native commissioner takes away some of the chief's main functions with the regulations stating, “The native commissioner shall have the sole power of appointing lands for huts, gardens, and grazing grounds for each kraal on vacant land or reserves in his district and no new hut shall be built or gardens cultivated without his consent and approval of the position selected…he shall from time to time fix the number of houses which shall compose a kraal.” But these were the tasks a chief performed and so if they were taken away from him his whole authority was undermined.

Drew’s proposal that the paramount chief’s powers be increased were opposed by Henry Melville Taberer (1870 – 1932)[26] the first chief native commissioner of Mashonaland and Clarkson Henry Tredgold (1865-1939)[27] the then attorney-general, who argued that to let the chiefs try cases would be to encourage corruption.

Taberer believed the chief’s judgement, “Frequently (not invariably) was influenced by the present given. Further, if the chief is a powerful one, he will help himself liberally to a portion of the judgement.” Even arbitration by chief should be discouraged but, “since natives know they can appeal against the decision of the chief to the native commissioner, the practice is a dying one.” He believed, “The whole idea of using chiefs was contrary to the official doctrine and that tribalism, like the reserves, was retrograde and it was the duty and the interest of government to assimilate the native into the new world, not preserve indigenous institutions.”

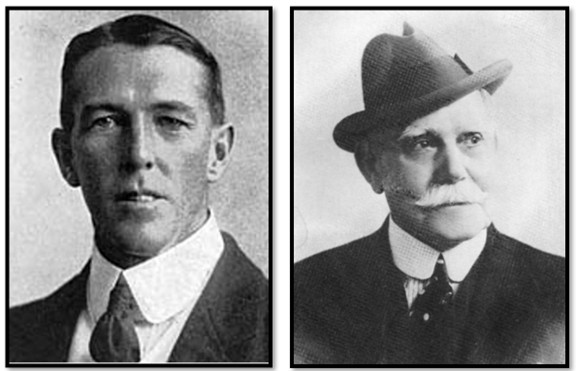

Henry Melville Taberer Herbert John Taylor

First Chief Native Commissioner, Mashonaland First Chief Native Commissioner, Matabeleland

Drew and other native administrators agreed that “in matters of native custom, an alien court, however well informed and well intentioned, may go wrong”[28] and believed a kind of indirect rule would work better, but the decision went against them and the movement was for the administration to gradually tighten its grip.

In reality the chiefs are given little power

Chiefs could be removed by the Administrator in Council subject to the agreement of the High Commissioner; even tribes could be divided or amalgamated. The chiefs had no legal powers; they were regarded as, “officials responsible for the good conduct of their tribes, for notifying crimes, deaths and epidemics to the native commissioners, for giving help with the collection of taxes and for the apprehension of criminals.”[29]

For this they received payment and by 1911 there were 142 paid chiefs in Mashonaland and 129 in Matabeleland.[30]

The BSACo administration was not dealing with a militarily strong African population after 1897

With the amaNdebele military monarchy effectively smashed after 1893 the administration resisted any form of suggestions that the old hierarchy should be restored in any shape or form. Even Njube, Lobengula’s heir to the chieftainship, who was educated at Rhodes’ expense in the Cape, was not allowed to return to Matabeleland. Taylor, the chief native commissioner for Matabeleland considered they preferred being directly responsible to the company administration resulting in no real cohesion amongst the indunas. They believed Africans often acted in opposition to each other. Taylor even encouraged some jealousy amongst the indunas saying this was the most expedient way of governing them.

In Mashonaland, the situation with the Mashona was similar with the old Karanga supremacy gone and although memories persisted, again there was no strong cohesion amongst the chiefs.[31]

The BSACo believed that abolishing the tribal system would quicken the pace of economic development

Henry Wilson-Fox, the chartered company’s general manager wrote to the company directors saying that Africans formed “the privates of the industrial army in every department of work.” He believed. Southern Rhodesia could be developed much faster if the tribal system could be dismantled with the Africans main role being that of wage labourers and secondly as producers of food. He believed that both roles required education and would not be achieved by segregating Africans in tribal trust lands or reserves.

He was impressed by the rate at which African agricultural production and rural prosperity was increasing as the growth in towns provided them with a larger market, but primarily he was keen to use available African manpower on the farms and mines. Education was the route by which African manpower would be absorbed into a wage economy and would also result in an increase of taxation. Fox privately even criticised the native commissioners who talked up “their natives” and built up a kind of vested interest in the existing African institutions that stood in the way of development. In his view they became, “a retrograde factor in the corporate life of the country” representing “a sleepy- hollow idea” of continuing out of date institutions.[32]

Native administration becomes increasingly centralised

In Southern Rhodesia and elsewhere as questions in Parliament made ministers more anxious to know what was going on and as newspapers constantly demanded information, more information was wanted from the native commissioners and their staff and as communications improved; the old excuses that permission took time, became increasingly redundant.

Mason writes that in the case of Crown Colony’s there was a graduated hierarchy of officials in which those at the top would have served as district officers and district commissioners which would have formed the basis for all their decisions. It was not the same in Southern Rhodesia where ‘native affairs’ was not the groundwork for all administrative posts but formed a completely separate organisation. The highest post was not chief secretary or governor, but chief native commissioner who then reported through the secretary for native affairs to the administrator or the Colonial Office’s watchdog, the resident commissioner.[33]

This resulted in headquarters being reluctant to decentralize power to the districts. As less was left to the initiative of native commissioners, they clung to the powers they had and devolved less authority to the chiefs. The concept of indirect rule through the chiefs became more and more diminished. Thus it became more and more established that tribal trust lands and reserves were the places where natives should live and should not be assimilated in the cities with their families, except when a source of labour.

Native Commissioners and Matabele cattle

The BSACo view was that all the cattle in Matabeleland belonged to the King. About 90,000 cattle were branded with the chartered company’s mark with the remainder left in native hands to milk. From time to time some would be called in for slaughter, or sale, or redistribution. Later it was believed about 70,000 cattle were still in native hands. The BSACo took 28,000 and left the remainder with the people. Not everybody believed this. Selous thought that almost every man of rank in Matabeleland had been a cattle owner, some of the indunas possessing large herds of private cattle.

Selous believed the BSACo’s mistake was not giving (say one-third of the cattle absolutely to the people and this became one of the causes of the Matabele Rebellion (Umvukela) as the people. would not have felt so defrauded. What happened? A native commissioner would receive orders to drive in so many head of cattle to Bulawayo and he would make up the numbers as best he could. Selous writes, “certain natives suffered wrong, especially owners of perhaps only three or four cows, who in some cases lost their all, both in cattle and faith in the honesty and justice of the chartered company which they deemed had broken the promise given them, as indeed was the case, though the mistake was made inadvertently and through not considering the investigation of the whole question of sufficient importance to take any trouble about.”[34] He says Reverend Helm felt the same.

Postcard of the native Commissioner and staff, native police and messengers at Plumtree about 1904

Selection of native commissioners

The BSACo generally favoured university graduates from England. Sir Charles Coghlan and the majority of the Legislative Council preferred local youths who were residents of Southern Rhodesia. The argument against local youths recruited straight from school was that they would have a narrow outlook, but they were recruited and needed longer to train often as clerks which meant they took a longer time to reach a position of responsibility. There were plenty of exceptions of course.

References

L.H. Gann. A History of Southern Rhodesia: Early Days to 1934. Chatto and Windus, London 1965

H.M. Hole. The Making of Rhodesia. Frank Cass & Co Ltd, 1967. https://archive.org/details/makingofrhodesia0000hole/page/n5/mode/2up

E. Howman. Sir Herbert John Taylor KT. Chief Native Commissioner. Rhodesiana Publication No 36. March 1977

P. Mason. The Birth of a Dilemma; the Conquest and Settlement of Rhodesia. Oxford University Press, 1958

The Patriot. 2 Oct 2014. The Notorious Native or District Commissioners, Part One. https://www.thepatriot.co.zw/old_posts/the-notorious-native-or-district-commissioners-part-one/

Notes

[1] See the article The Matabele Campaign of 1893 - the march on Bulawayo under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[2] The Birth of a Dilemma, P271

[3] There are many references in early biographies to Dr Jameson’s own dislike of administration and he and Rhodes always kept BSACo admin staff to the minimum. See the article Was Archibald Ross Colquhoun; first Administrator of Mashonaland 1890 – 92, a failure or was he actively undermined by Dr Jameson? under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[4] The Birth of a Dilemma, P271-2

[5] A History of Southern Rhodesia, P147

[6] Sir Herbert John Taylor, Chief Native Commissioner, Matabeleland, 1895-1913: Chief Native Commissioner, Southern Rhodesia, 1913-1928.

[7] See the article The inauspicious start to Herbert Taylor’s thirty-three year career as Chief Native Commissioner under Matabeleland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[8] The Making of Rhodesia

[10] Sir William Milton (1854-1930) Acting Administrator (1897-1898) 4th Administrator (1898-1901) 6th Administrator (1901-1914)

[11] Ibid

[12] Native Councils were later superceded by African or Chief’s Councils

[13] Sir Herbert John Taylor KT. Chief Native Commissioner

[14] The Birth of a Dilemma, P272

[15] Hardly surprising after a BSACo notice of 7 July requesting transport riders and travelers’ not to fire at friendly natives on the assumption that they were rebels!

[16] The Mashona Rebellion (First Chimurenga) only ended in October 1897 with the surrender of Kaguvi, the spirit medium who carried the Mlimo’s messages. See the article Old Fort Hartley and the Cemetery at Hartley Hills goldfield under Mashonaland West Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[17] The Birth of a Dilemma, P272

[18] Ibid, P277

[19] Ibid, 225

[20] Ibid, P219

[21] The Birth of a Dilemma, P220-1

[22] Ibid, P221

[23] A History of Southern Rhodesia, P146

[24] Ibid, P148

[25] Ibid, P275

[26] Henry Melville Taberer (7 October 1870 – 5 June 1932) was born at a mission station in the cape Colony. He went to university at Keble College, Oxford gaining a B.A. (Hon) in theology and played for Oxford against Cambridge in both long jump and rugby union, later playing cricket for Natal, the Transvaal and Rhodesia. He claimed to speak several African languages more fluently than he did English. From April 1896 to 1900 he was Controller of Cattle in Southern Rhodesia before his appointment as Chief Native Commissioner in Mashonaland in 1895. He was a captain in the Umtali Volunteer regiment and served through the Mashona rebellion (1896–97), being twice mentioned in despatches

[27] Father of Sir Robert Tredgold

[28] The Birth of a Dilemma, P276

[29] A History of Southern Rhodesia, P148

[30] Ibid, P150

[31] A History of Southern Rhodesia, P148

[32] Ibid, P149

[33] The Resident Commissioner’s role was To be aware of any legislation that was discriminatory against Africans. Section 80 of the Order in Council of 1898 read, “No conditions, disabilities, or restrictions shall, without the previous consent of a secretary of state, be opposed upon natives by ordnance, which do not equally apply to persons of European descent, save in respect of the supply of arms, ammunition and liquor.

[34] The Birth of a Dilemma, P189