Terracing and Water Furrows

The terracing is not easy to see, although there are thousands of kilometres of terracing on nearly every hillside all over Nyanga. Once your eye becomes trained to the signs of terracing, you’ll see it along much of the route between Juliasdale to Watsomba. Terracing is believed to cover an area of at 8,000 square kilometres.

The people who adopted this settled way of life brought with them domesticated animals, cultivated crops on the hillsides and used pottery and iron tools in their daily lives. The area occupied by terracing enjoys good soils and a comparatively high rainfall for Zimbabwe > 1,000mm.

In effect, many archaeologists have argued that terracing became a soil management mechanism for managing the steep sided hills of the Nyanga region in that the terracing reduces the soil run-off and conserves water.

From Rhodes Nyanga Hotel: drive 1.6 KM to the main road (A14) Turn right and head for Nyanga Town, 4.3KM continue past the Troutbeck turnoff on your right, 7.4KM continue past the intersection to Nyanga town, 9.2KM continue past the Hospital, 11.7KM tar road changes to untarred road, 14.8KM reach furrow on right at Ziwa Ruins Intersection which continues under the road and parallel to the Ziwa Ruins road.

GPS reference for water furrow: 18°10'28.80″S 32°44'40.55″E

Archaeologists say terraces are the most characteristic of Nyanga ruins and there are thousands of square kilometres of them in existence. Terracing is divided into Type 8A, simpler and earlier terracing found on the Uplands and Type 8B, more developed, later in period and found in the Nyanga Lowlands around Mount Ziwa (formerly van Niekerk Ruins)

Many Type 8A terraces do not have stone walling, being made of earth, and they are not particularly easy to see, unless your eye is trained, or the setting sun gives them away by their shadows.

Type 8B are stone-faced, with the earth banked on the inside, the height of the stone walls depending on the steepness of the hillside, but often rising to two metres or more. In some areas, whole hillsides are covered with thirty or more lines of terracing. For example, at Ziwa Ruins, it has been estimated there are 800 kms of terracing in an area of 30 square kilometres. Examples of terracing patterns are observable from Google Maps at GPS reference: 18°08'10.13″S 32°38'15.50″E which is the position of the Ziwa Site Museum. The area lies in rain shadow and there are few perennial streams, so terracing is a good water conservation method.

Peter Garlake says that early explorers such as Dr. Heinrich Schlichter and Dr. Carl Peters believed that vast populations once lived here to construct such extensive terracing. However, he believes that without the use of fertilizer and manure, the land in the terraces would quickly loose its fertility which forced the farmers to continuously move to new areas. Building terraces was a convenient way of clearing the ground of stone and vast areas would be cultivated and then abandoned over the course of a few centuries.

Robert Soper in his book The Terrace Builders of Nyanga presents detailed plans and sketches showing that the terraces show how the agricultural community grew crops on the terraced hillsides, raising livestock in the pit structures in the Nyanga highlands initially from about AD 1300 and then moved down into the lowlands by AD 1800 leaving the remains of their efforts over an area of over 8,000 square kilometres. He acknowledges that terracing is used in other parts of Africa, such as South Africa, East Africa, the southern region of Ethiopia and in Sudan, but nowhere are they used as extensively as Nyanga.

There are differences in use however; Sutton observes that the terraces found in Tanzania were designed for irrigation, whilst the ones in Nyanga were mainly for soil conservation purpose,

Ann Kritzinger presents an alternative theory that the terraces are the result of extensive mining for gold and the pit structures are hydraulically engineered tanks for the winning of gold. The results of gold assays do seem to indicate some sort of process to win gold was being carried out; but the jury is out over whether gold-mining rather than agriculture was the purpose of this huge human effort in the past.

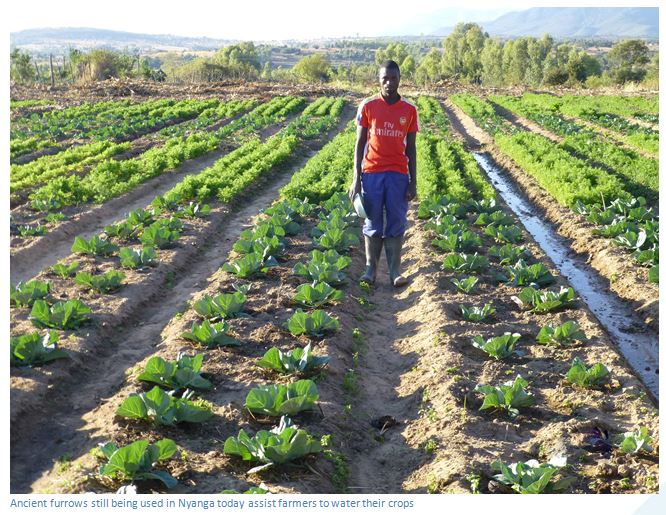

Peter Garlake states in his Guide to the Antiquities of Inyanga that more evidence of the engineering skill of the Upland builders are the water furrows; simple earth ditches leading from perennial streams in a gradual gradient to the living sites. Often they run for several kilometres and although many have been destroyed, others are adapted for use today, as the photo illustrates. In the 1970’s a large water furrow 275 metres from the Rhodes Nyanga Hotel could be followed along a picturesque footpath to its junction with the Mare River, but the furrow is no longer in use with water being transported by pipe.

Acknowledgements

P.S. Garlake. A Guide to the Antiquities of Inyanga. Published by the Commission for the Preservation of Natural and Historical Monuments and Relics in 1972. Courtesy of ORAFs.

R. Summers. Ancient Ruins and Vanished Civilisations of Southern Africa. T.V. Bulpin. Cape Town 1971

Soper, R. The Terrace Builders of Nyanga. Harare, Weaver Press 2006

Ann Kritzinger. Laboratory Analysis Reveals Direct Evidence of Precolonial Gold Recovery in the Archaeology of Zimbabwe’s Eastern Highlands. Proceedings of 9th International Mining History Congress, Johannesburg 17-21 April 2012

Sutton, J.E.G. 1984. “Irrigation and soil conservation in African Agricultural history with a Reconsideration of the Inyanga Terracing (Zimbabwe) and Engaruka Irrigation works (Tanzania).” In Journal of African History, 25. (25-41)

Ann Kritzinger. Laboratory Analysis Reveals Direct Evidence of Precolonial Gold Recovery in the Archaeology of Zimbabwe’s Eastern Highlands. Proceedings of 9th International Mining History Congress, Johannesburg 17-21 April 2012