Home >

Manicaland >

The Old Umtali Pioneer's Cemetery and the strange story of the death of Monty Bowden

The Old Umtali Pioneer's Cemetery and the strange story of the death of Monty Bowden

Why Visit?:

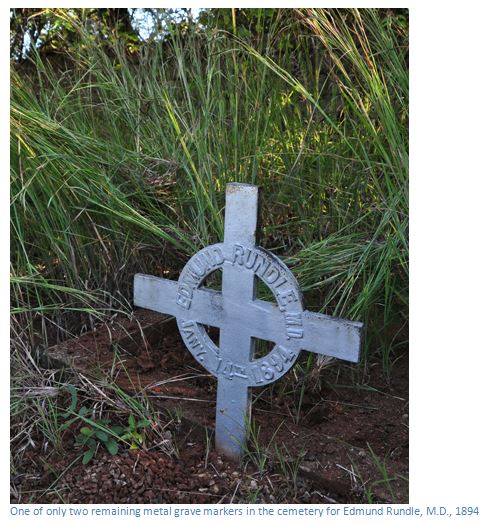

- With the Old Mutare cemetery vandalised and abandoned on the former Premier Estate there is probably no good reason for visiting these days, but it remains a strong link to the courage and determination of the earliest Europeans who came to this country.

- In 1896 the construction of the railway between Beira and Salisbury led to Old Mutare being moved a third time so that it was closer to the railway line – compensation was paid by the BSA Company to the townspeople for the cost of moving to the present-day site of Mutare.

- The cemetery became abandoned, but not forgotten, as on 17 August 1950 a ceremonial plaque was laid at the Old Umtali cemetery by the Governor of Southern Rhodesia, Maj. Gen. Sir John Noble Kennedy.

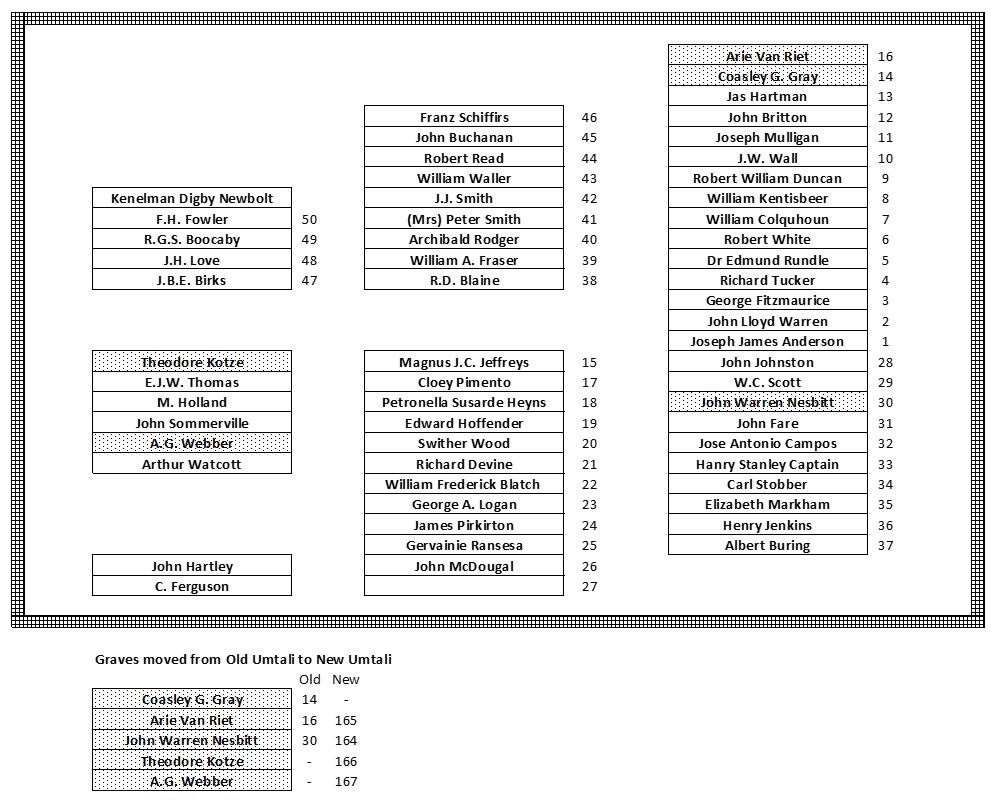

- The chaos of the land invasions after 2000 led to the desecration and current ruinous state of the cemetery. Fortunately, what happened at Old Umtali has not been repeated at most cemetery sites around the country; they look abandoned and overgrown, but they have not been vandalised. This article includes a cemetery plan drawn up in 1913 found during research at the National Archives of Zimbabwe.

- The story of Monty Bowden is probably typical of many of the young adventurers who came to this country in the 1890’s. Life was hard and demanding; many left soon after they realized all the talk of making their fortunes from gold was just a pipe dream, others like Bowden caught fever and are buried in lonely graves in the veld.

- The two articles from which most of this article are taken form a conjunction; the first by Davis and Dodge describe the Old Umtali cemetery, the second by Jonty Winch tells the story of how Monty Bowden came to be buried within the cemetery. The actual site of his grave, the first recorded at Old Mutare in 1892, is not marked on the 1913 cemetery plan, so evidently the site of his grave had been forgotten, but Nurse Blennerhassett records the event in her book.

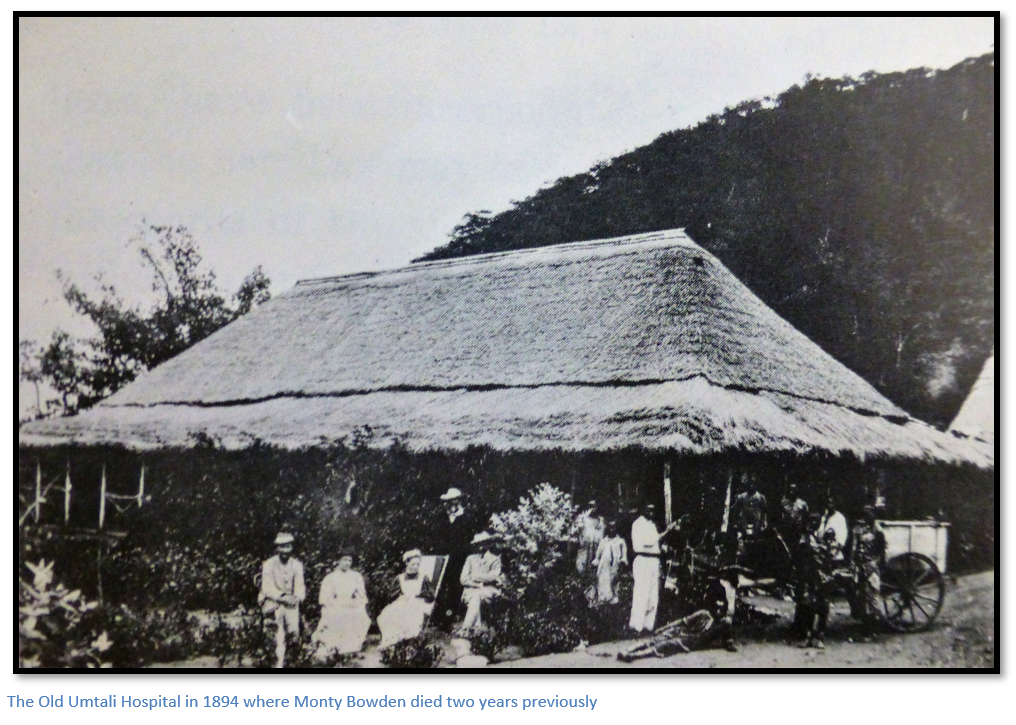

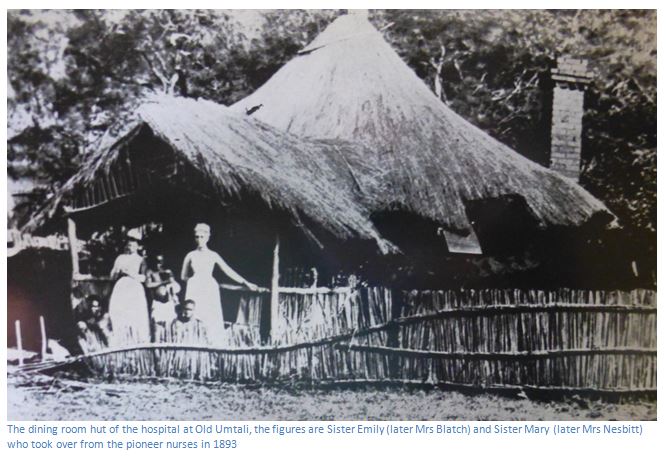

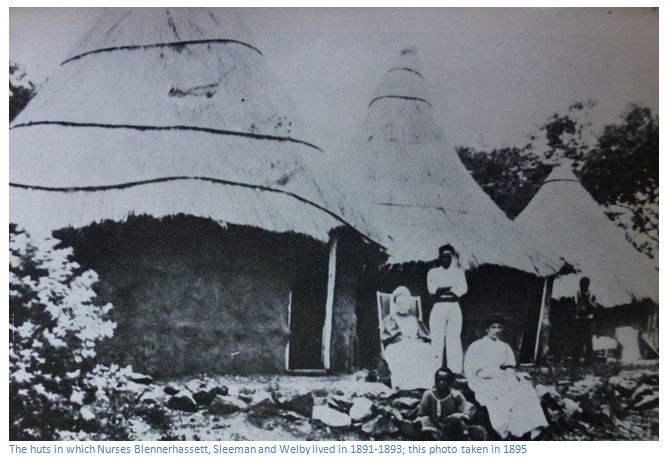

- The timeline is as follows: Fort Hill established by November 1890; Nurses Blennerhassett, Sleeman and Welby arrive in July 1891, a hospital is built. In December 1891 a new hospital is built at Old Umtali, now the Methodist Mission and Fort Hill is abandoned. Old Umtali is where Monty Bowden died on 19th February 1892. Umtali (now Mutare) moved to its present site in 1897 when it was established that to detour the Beira - Harare railway line to Old Mutare would be costly and add ten miles to the route.

How to get here:

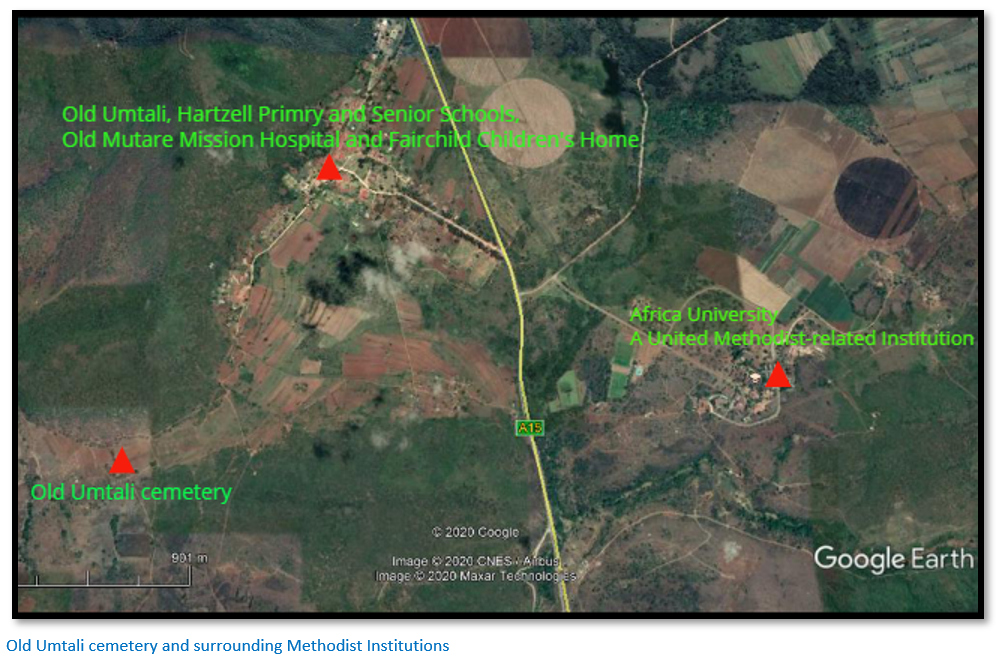

Coming from Harare, approximately 10 kilometres from Mutare turn left off the A3, the main Harare to Mutare Road, onto the A15 to Nyanga, 4.0 KM immediately after crossing the Mutare River turn left along a good untarred road. At 6.33 KM turn right and head north up the western edge of the hills, 6.9 KM keep on and do not take the right fork, 7.2 KM turn left and the old Mutare cemetery is 50 metres to your north west.

Background

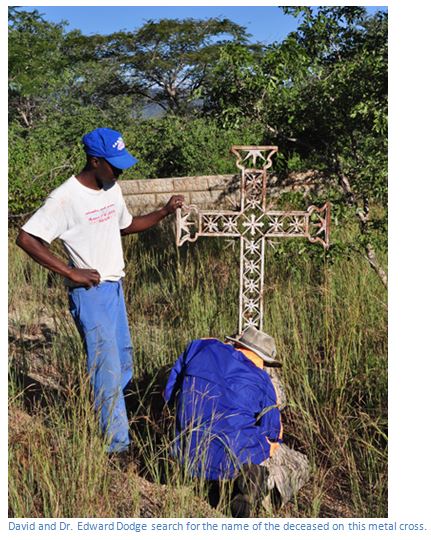

This article is from several sources. The first resulted from a visit to the Old Umtali cemetery in 2012 by G.R. Davis, who took the photos used in the article, and Dr David Dodge, both from Africa University whose campus is close by. The other source is an article published on the ORAFs website written by Jonty Winch and condensed from his book England’s Youngest Captain. Eddy Norris created the ORAFs website and his daughter Denise, continues the good work. The Old Umtali cemetery plan is from the National Archives of Zimbabwe (NAZ GU 1/4/1)

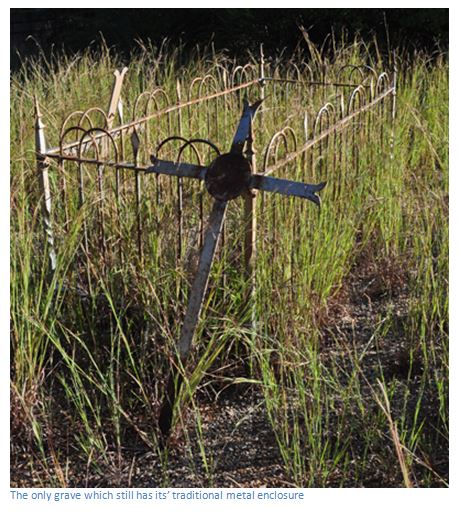

The old cemetery has been deliberately vandalised, and its’ poor condition is not the result of mere neglect. Once the former owners had been removed from Premier Estates after the land invasions, local people cleared away the marble headstones and metal grave markers.

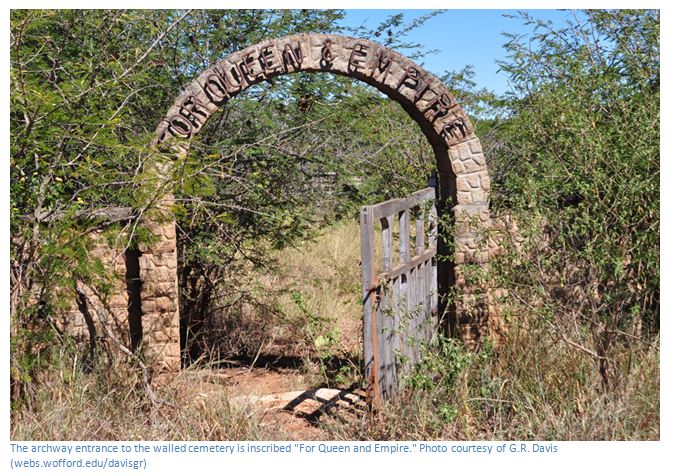

The neat little cemetery with its arched entrance and low walled surround still stands; but it has an abandoned and forlorn look. It looks overgrown and unloved, but unlike most cemeteries in Zimbabwe, those people that died in Old Umtali and were buried here have been treated in an uncharacteristically undignified manner. This is in sharp contrast with the graves in the nearby Methodist cemetery where the cemetery is neat and tidy, and the graves have been treated with dignity.

My initial article said that sadly there was no known list of those buried within the cemetery and only a few grave markers remain. However, whilst carrying out research for an article on the Pioneer memorial crosses and the Loyal Women’s Guild at the National Archives of Zimbabwe (NAZ) I came across several cemetery plans. Most were prepared by the British South Africa Police who were responsible for the cemeteries in more remote locations, but this plan was prepared by TW on the 28 January 1913 and has a British South Africa Company seal at the top of the page.

In addition, the references at NAZ say there are the graves of two suicides buried outside the western corner of the cemetery.

The historical importance of this site was recognized many years ago at the unveiling of the Old Umtali cemetery plaque on 17 August 1950 by the Governor of Southern Rhodesia, Maj. Gen. Sir John Noble Kennedy, on the occasion of the Southern Rhodesian Jubilee celebration in Umtali (now Mutare) seen in the photo above.

The plaque remains seen above was assembled from fragments that G.R. Davis and Dr David Dodge found in the weeds near the entrance during a visit to the cemetery in April / May 2012.

Few will be aware that the oldest burial within this cemetery is that of England's youngest ever cricket captain. The Tragic Tale of Monty Bowden is told by Jonty Winch on the ORAFs website with references to the incident in D.C. de Waal’s book With Rhodes in Mashonaland describing how de Waal accompanied Rhodes and Major Frank Johnson from Beira to Mashonaland and Salisbury (now Harare) in September 1891. They went up the Pungwe River by barge and then by cart but abandoned the cart to travel by horseback to Penhalonga. At Fort Hill, the first Umtali, they met Dr Jameson and went by coach to Salisbury returning to the Cape by the end of November 1891. [see the article on Fort Hill in Manicaland Province]

But to return to Jonty Winch’s account of Montague Parker Bowden which I have quoted largely in verbatim.

The first English cricket team to visit South Africa in December 1888 was put together by Captain Gardner Warton received with great acclaim, although at the time it was not considered an official England squad. [1] At a public dinner were present His Excellency the Governor of the Cape Colony and High Commissioner for South Africa, Sir Hercules Robinson, The Chairman was Sir Thomas Upington, former Prime Minister of the Cape and other guests included Sir JH de Villiers (the Chief Justice), Sir David Tennant (Speaker of the House of Assembly), Sir Thomas Scanlen (Prime Minister 1881-84) and the Hon JH Hofmeyr (Parliamentary leader of the Afrikaner Bond).

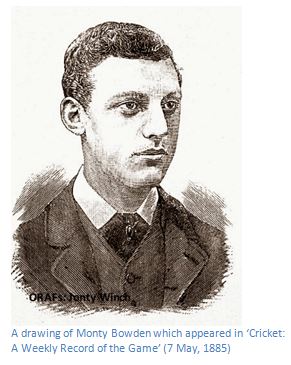

Monty Bowden was a member of this English cricket team having been England’s outstanding schoolboy batsman of 1883. At the end of the season, Cricket: A Weekly Record of the Game included an article on the high scorers for the year. It recorded the achievements of three players – England stars; Dr EM Grace of Gloucestershire and WW Read of Surrey, and the promising young Bowden. The youngster had not only scored 845 runs at an average of 52.81 for Dulwich College, but had played for Surrey. He was to experience several successful seasons for the county before suffering a lapse in form. A taste of the good life possibly affected him, whilst the initial aura and excitement of playing for Surrey might have worn off. To his father’s consternation, he frittered away the money he earned as a stockbroker’s clerk and was perpetually in debt.

Jonty Winch says at the welcoming dinner the visiting cricketers listened to speakers taking turns to drum the importance of the northward expansion of the British Empire. Upington stated, ‘I sincerely hope before Sir Hercules Robinson’s period of office in this Colony has terminated, that what is at the present moment known as the “sphere of influence” will be known as the British Protectorate up to the Zambezi. And I shall be inclined to go further ... I see no reason why we should not cross the Zambezi …’ His statement was greeted with loud and prolonged cheers.

The twenty-three-year-old Monty Bowden was not oblivious to the relationship between sport and expanding British imperialism. He had attended Dulwich College, a public school that made a significant contribution to the Empire through support for the military and the Indian civil service. Yet Bowden had no desire to follow a similar career path. He had not enjoyed the hardness, even brutality, of much of school life. He had avoided the rigors of the football field and the Rifle Volunteer Corps, the latter attracting a large following which included his elder brother Frank. Young Monty occupied himself in other areas, demonstrating ability in drama for which Dulwich had, by that time, gained a reputation. His love for cricket might have been regarded as an extension of his interest in acting as he was a stylish batsman and a lively showman behind the stumps. The game awakened his aesthetic sensibility and became an essential and influential part of his life.

A tour to Australia in 1887-88 had revived Bowden’s cricket fortunes. Fitter and more focused, he blossomed in the 1888 season. He finished third in the Surrey averages for all matches, scoring 797 runs at 31.22, and was placed eleventh in the English first-class averages for the season.

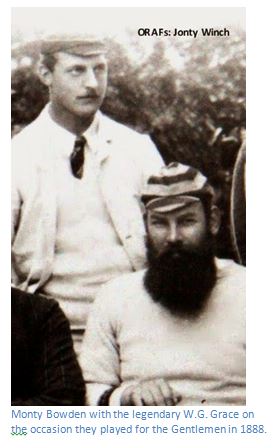

A few weeks later, he left England for South Africa in the knowledge that he had made a notable contribution to the success achieved by Surrey, England’s undisputed champion county. His talent as a wicket-keeper had also been recognised in his selection for the Gentlemen against both the Players and the Australians, whilst his explosive batting commanded interest at cricket grounds around the country.

The cover of ‘England’s Youngest Captain’ written by Jonty Winch, which features Monty Bowden in the course of the 1888/89 tour to South Africa – the first trip by an English sporting team to that part of the world.

In South Africa his wicket-keeping ‘fairly electrified the locals’. On 25 March 1889 he captained the tourists in the second Test at Newlands when tour leader, Aubrey Smith, was unable to get to Cape Town in time for the match. Bowden, at 23 years 144 days old, remains England’s youngest-ever Test captain. and perhaps the only one not to know he was England captain – the matches against the representative XI were at the time simply considered tour matches and only given status as South Africa’s first Tests years later, by which time Bowden had died. He led his side to an emphatic victory by an innings and 202 runs – still a record margin in Tests between the two countries – with Johnny Briggs claiming fifteen wickets in a day.

At the conclusion of the tour, Bowden decided to join his captain in a stock-broking business. They had spent an exciting week on the Rand and were stimulated by romantic notions of amassing great wealth. Bowden brushed aside his commitment to Surrey cricket in the belief that everyone would understand. He was convinced that it would take only a year or two to amass his fortune.

The partnership of Smith and Bowden did not last a year. Like so many other businesses, it was forced to close as a result of the dramatic financial crash which took place. The boom of the previous two years had been killed by dishonest methods, rumours that gold was giving out and the panic-selling of shares.

Smith publicly attributed the closure of their business to bad luck, but people in the know might have disagreed with his interpretation. The Comtesse de Bremont, an American friend of Oscar Wilde’s mother, questioned whether the two cricketers were committed to their work. Through her novel, The Gentleman Digger: A Study of Johannesburg Life, she ridiculed their efforts: “When the team first came to the Rand we set him [Smith] and another cricketer [Bowden] up in brokering. They prospered for a few months but were not smart enough to go ahead on their own legs.”

Amidst the gloom, cricket was again Bowden’s saving grace; he continued to demonstrate good form in the 1889-90 season, averaging 53.92 from 701 runs. Admittedly his runs were made in the less exalted sphere of Transvaal club cricket, but the fast wickets and dry conditions allowed him to develop his footwork and timing to a new level.

He was well prepared for the first Currie Cup challenge when Kimberley hosted the Transvaal in April 1890. The game became a personal triumph as he scored 63 (out of 117) and an unbeaten 126 (out of 224 for 4) to inspire an historic victory. ‘Galopin’, writing in The Star, was ecstatic: “It is to Bowden more than anyone else in the team that Johannesburg owes the victory; and I think most people will now admit the truth of the assertion – which I have held for a long time – that Mr. Monty Bowden is far and away the best bat in South Africa ... It is to be hoped that a reception befitting the occasion awaits this talented young cricketer, as well as the other members of the team.”

Bowden did not go back to Johannesburg. He admitted to being ‘dead broke’ but his problems were deeper. He knew his firm’s bankruptcy would affect his chance of being readmitted to the fold should he return to England. He also realised that much depended on whether the London Stock Exchange committee accepted Aubrey Smith. If Bowden had known, he would have been horrified to discover that Smith told the committee their business failed because of an “untrustworthy partner who had absconded.” It was an absurd claim as Bowden had bid goodbye to Smith in Kimberley and had, in fact, collected the Currie Cup when his captain made a hurried departure. As it turned out the committee were not fooled by Smith’s argument and his request for admission was refused. Justice prevailed, but damage had been done.

The process by which Smith’s fate was decided took several months and in the interim Bowden had to find employment. His options were limited: the idea of a severely reduced status as a professional cricketer was not considered and, in the aftermath of his business failure, he dared not approach his father, a successful shipbroker, but with the mid-Victorian stereotype of a stern, unapproachable character. In any event, his father would probably have supported the one clear option open to his son and that was for young Monty to join the BSA Company’s expedition to Mashonaland.

Rhodes’s planned expedition to Mashonaland in 1890 attracted 2,000 applications for a force of nearly 200 men. They were recruited from various trades and professions and, once they had opened up the new territory, they would be free to set up their own businesses and form the structure of a complete community. As a celebrated cricketer, Bowden’s selection for the expedition was guaranteed. It would give him another chance to earn the fortune that had eluded him in the Transvaal goldfields, although sacrifices would have to be made. For a start, his career as a cricketer was put on hold indefinitely.

Bowden’s concerns were numerous, with his greatest fear being the anticipated military-style discipline. It would bring an abrupt end to the comforts he had always cherished as an English gentleman. He would miss his role as a cricket celebrity, a status amply re-enforced during his stay in Kimberley. Ironically, when news circulated that he was joining the expedition, lustre was added to the fame he had acquired. For a few weeks, he could not resist playing up to the role, disguising the torment of someone who was in reality the antithesis of the intrepid Pioneer.

There was tremendous excitement in Kimberley during the weeks leading up to the departure of the expedition. Frederick Courtney Selous, the appointed guide to the Pioneer Corps, was in the town until 13 April and citizens jostled with one another to catch a glimpse of one of the most romantic figures of the period. The governor, Sir Henry Loch, made an official visit prior to the departure of the expeditionary force. A banquet was held in his honour at the Town Hall on 17 April. Bowden was mentioned high on the published list of dignitaries, his name appearing alongside Cecil John Rhodes, members of the Cape parliament, Sir Thomas Upington, Sir John Willoughby (second-in-command of the Pioneer Police), Admiral Wells, the Reverend John Moffat and Sir Sidney Shippard (Administrator of Bechuanaland) – men deeply involved in the expedition to Mashonaland. Bowden listened intently to several rousing accounts of the need to take the Pioneer route.

On Saturday 3 May 1890, with three days to go, Charles Finlason was able to announce in the Daily Independent that Bowden had finally made up his mind to join the Pioneer Corps. “The force will have a very powerful cricket team,” he observed. “It would be sad if the Currie Cup found its way to Vryburg, or Elibe, or some town on the Zambezi.” Finlason was obviously unaware that Bowden had already ‘sold’ the Currie Cup. During their time in Kimberley, Bowden and some of the Transvaaler’s stayed at the Central Hotel. With the players enjoying the good life, their debts mounted and eventually the management became concerned about payment. Bowden, as the group’s spokesman, was asked for some form of surety. He obliged by handing over the one item of value that he possessed – the Currie Cup – to the manageress, Mrs. Creagh.

Bowden continued to play cricket during the march northwards. Between Zeerust and Mafeking his section of the Pioneer Corps met members from Cape Town. Adrian Darter recalled: “The Johannesburg contingent challenged us to cricket and gave us a tremendous drubbing, due chiefly to the savage relish they took in my bowling, and the unmerciful manner in which they punished it. Wimble and Bowden were the chief offenders – to me – both played a splendid innings. We contested this match in the neighbourhood of Otta’s Hoek, and in the vicinity are the Malmani goldfields …”

Further matches were played in Mafeking, a bustling staging post which served as a temporary base for the Pioneers. Later a match was arranged on the afternoon of 16 August 1890 near Fort Victoria (now Masvingo) It was the first cricket match to be played in the country that was to become Rhodesia and ultimately, Zimbabwe. Bowden captained ‘A’ Troop and the Scottish rugby international, Edward Pocock, led the combined ‘B’ and ‘C’ Troops. Skipper Hoste later wrote; “I forget who won. It was probably ‘A’ Troop as they had several outstanding cricketers, notably Monty Bowden.”

Cricket aside, the expedition was not a pleasant experience for Bowden. He had loathed the intensive training in preparation for the march. The column leader, Frank Johnson was a hard taskmaster and as there was a strong likelihood of their being attacked by the Matabele in the course of the 400-mile journey, he wanted to ensure that they were a well-disciplined body. One Pioneer wrote that the men; “were being unnecessarily worried about and overworked, what with parades, drills, fatigues, etc.”

Charles Finlason referred to Bowden in the Daily Independent: “I heard of his progress from time to time. The life was abhorrent to him and he fretted until he fell victim to an attack of fever. He became so depressed as to be almost broken-hearted; his one aim was to get out of the force and back to civilisation.”

Bowden’s plight upset his friends and they rallied to his assistance. “Great efforts were made,” continued Finlason, “to obtain his release [but] from the first attack of fever he seems never to have recovered.”

The Star reported his death on 24 October 1890. Finlason thought it was likely that “many months of sickness and debility had seen the young trooper return to Motloutsie [Macloutsie] where he died a lingering death.” The emotional report infuriated Dr Rutherford Harris, Rhodes’s ‘close confident, henchman and hatchet man,’ but Finlason was not unduly worried. He presented a patronising explanation in the Daily Independent: “I am assured that Mr. Johnson is singularly kind-hearted and would be the last to refuse to grant Bowden his release had he asked for it. The probability is that Bowden, being in a depressed state incidental to perpetual fever relapses, was very anxious to get home, but was prevented from moving, not by the commands of the Chartered Company or Mr. Johnson, but because he had not sufficient money to make the journey.”

The comment did not reflect well on the Company and its concern for the welfare of its men. But those who knew Bowden would have been aware of the reasons that led to the impecunious cricketer joining the Pioneer Corps. They would have realised that he was trapped and would have stayed that way until someone came up with a means of extricating him from a wider and increasingly complex personal predicament.

Another factor to be considered was that Johnson made it very difficult for his men to obtain a release and, as a deterrent, had issued a regimental order to that effect. He had also instituted a censorship of letters. When efforts were made to gain Bowden’s release, Johnson and Harris might well have used some means at their disposal to block it. They would not have wanted somebody as well-known as Bowden leaving the expedition, being interviewed and possibly criticising the manner in which it operated.

Throughout a tense debate which took place in the press, rumours circulated that Bowden was still alive. Then, on 11 December, the Daily Independent printed an official announcement. A triumphant Dr Rutherford Harris had supplied a telegram for publication: “Fort Salisbury – Mr. Bowden alive and well; he was in here yesterday from Hartley Hills; is very indignant about this false report.”

The Star carried out an investigation and later revealed that a man had died of fever. He was a post-rider in the Chartered Company’s Police and his name was Briggs. It transpired that when details of the man’s death were relayed to Pretoria, the recipient of the information was careless in its subsequent distribution. He had misplaced and could not record the name of the dead man except for the fact that it was the same as that of an English cricketer; “… it began with a B… someone else along the line recalled that Bowden had signed up with the Pioneers … it must be him…”

Bowden’s venture to Hartley Hills was a failure because when it came to prospecting, he and most of his associates were rank amateurs. After a few months of struggling in fearful weather, with indifferent food and the ever-present fever, many of the men began to lose heart. Bowden joined Edward ‘Ted’ Slater as a partner in a trading business in Fort Salisbury. Prospects seemed good as the Pioneer Column had been unable to transport much in the way of building equipment, materials and tools. Nor had they been able to bring up furniture, cooking utensils, bedding, lamps and the various requirements to start a new life. Unfortunately for Bowden and his partner, a horrific rainy season lasting five months prevented trading taking place. The rivers flooded, and the roads were impassable. By Christmas 1890, the fledgling capital was effectively cut off from the outside world and the settlers suffered great inconvenience and hardship.

Towards the end of March 1891, the Chartered Company promoted the excellent prospects in Manicaland. Reports were optimistic that gold existed there in great quantities. A geologist, Dr Hector Smith, had stated in a published pamphlet in January 1891, “I have not the slightest doubt that Manicaland of today, and the Ophir of Sheba and Solomon’s time are one and the same.”

For Bowden a move to Umtali on the eastern border made sense from a business angle. The cost of importing goods into Mashonaland by road from South Africa was prohibitive, and his best option would be to operate the Beira route. Goods could be brought up from South Africa by sea and unloaded at Beira. From there they would be taken by a small launch [the Shark] up the Pungwe River to Neves Ferreira, about 5 kilometres from M’pandas [Mapanda] Native Carriers then took the goods 280 kilometres to Umtali.

When he arrived in Umtali, the town was no more than a collection of scattered huts on a steep little kopje near the present turn-off to St Augustine’s Mission on the road to Penhalonga [Fort Hill] Bowden’s trading business was conducted on foot and necessitated leading his porters through heat and swamp on the treacherous lion-infested journey to the trading post at M’pandas. African bearers cost little more than a yard or two of limbo, but they were scarce, especially when their own maize fields needed attention and they were likely to run away at awkward moments.

Whilst Bowden struggled to establish himself, cricket officials in South Africa lamented his departure. Harry Cadwallader, the Cape Times reporter and secretary of the South African Cricket Association, was in the process of organising an overseas tour and believed Bowden’s presence in the South African team would be the draw card needed to attract financial backing and to encourage counties to provide fixtures.

A trip to Mashonaland to chat to Bowden was not out of the question. The territory was a major talking point and it suited the Cape Times to have a man on the spot. It was agreed that Cadwallader should update views on gold prospects; the growing impatience with the Chartered Company; the findings of an investigation by the controversial Randolph Churchill; the aftermath of the British-Portuguese conflict … and lure Bowden back to South Africa.

Cadwallader’s venture was held up at M’pandas because of lack of transport and he spent nearly two months in a tent erected haphazardly on the bank of a muddy stream. Local inhabitants were rarely pleasant and competed viciously for business at cut-throat prices. The Pungwe River, with its monstrous crocodiles, ran along one side and a stagnant creek bordered another. Dense fog from the water often enveloped the area. It was not a place that anyone wished to stay for long. Like the other Portuguese villages, it was dirty and unkempt, and rats were a virtually uncontrollable feature.

The one bright moment for Cadwallader occurred when Bowden arrived on 12 July 1891. He swept dramatically into M’pandas, heading a convoy of seventy naked carriers. Cadwallader was told that Bowden had: “come to fetch provisions for the Europeans and forces in Manica … they have very little left.” The carriers had been collected with much difficulty from Manica kraals. It was therefore to Bowden’s immense frustration that he lost a number on arrival because they were in demand at M’pandas and could obtain a higher rate of pay from other parties.

Cadwallader was thrilled to meet Bowden and to discover that he intended travelling to Durban before the next rainy season. The prospect of Bowden being available for South African cricket was very reassuring. But, tragically, the next few months would yield numerous problems. Bowden’s second venture to M’pandas was marred by the dreaded fever and he was fortunate to be rescued by Rhodes near the Mozambican village of Mandigo. Rhodes was on his first trip to the country that would bear his name and he was understandably anxious to assist Bowden.

DC de Waal wrote: “Mr Bowden had with him some thirty carriers, who were carrying flour, liquor and other provisions for his shop at Umtali…Before Mr Bowden parted with us, Mr Rhodes gave him a bottle of whisky. At this action of the Premier I felt rather displeased, for we had very little of that liquor left, and I told him so afterwards.” “Well,” said Mr Rhodes, “we have some old brandy still. Bowden complains of feeling poorly and fatigued – his colour testifies to it – and it is only right that I should help him.”

The next day, Rhodes and Bowden met again, and De Waal received another surprise; “Bowden complained that his health was rapidly giving way, and that he felt very exhausted. Mr Rhodes deeply sympathised with the poor man, and I no less.” On this occasion, Rhodes gave Bowden the horse that de Waal was using. “Not to appear disagreeable,” said de Waal, “I did not utter a word, though it was with a feeling of deep regret that I witnessed my dear brown pony leave us, and the animal showed its disinclination to do so by repeatedly neighing as it was being led away. Mr. Rhodes now asked me whether I minded his giving my horse away. That,” I answered, “you should have asked me before you did it. But you would have had no objection?”

In December 1891, Charles Finlason arrived in the country. He was shocked by Bowden’s condition and wrote; “The hardships that he had incurred had told severely on him and he was much weakened by the fever. He was in the best of spirits although he complained that he could not get entirely rid of the fever.” Finlason also discovered that Bowden had delayed his departure for Durban. “He learnt whisky was fetching three and four pounds per bottle. The chance appeared too good to be lost and he determined to make one more journey and take his chance of getting back before the rains set in.”

Finlason detested Fort Hill, not least because he was paranoid about fleas. “When I got to Umtali,’ he told readers of The Star, ‘the camp [Fort Hill] was being shifted to the new site [Old Umtali, near the cemetery described in this article] some seven miles nearer Salisbury.” He explained: “The move was imperative, because the Company had omitted to secure the first site of the township to themselves and enterprising prospectors came along and pegged out the whole camp, fort and all. So, a new site had to be found. It was as well because the whole place would have been uninhabitable in another three months, owing to the fleas. They used to drive me out into the night sobbing. It was dreadful.”

According to Finlason, the new township [see the article on Old Umtali – the second site in Manicaland] was a vast improvement, situated in a healthy spot and out of the range of Portuguese gunfire should a war erupt. He admired the green and wooded hills surrounding the town on all sides, while streams of the clearest water flowed past it in the east and south. At that time of the year, noted Finlason; “the grass is as green as it can be seen in summer in “dear old Ireland” and we have dells and lovely nooks here which would take a lot to beat.” Umtali, of course would move once more before the end of the century.

By the end of 1891 developments indicated that Bowden intended settling in new Umtali. A new site for the town had been selected and surveyed, and he displayed a commitment to its future by requesting a stand in Second Street. He also showed an interest in prospecting in the Penhalonga valley but did not avail himself, as a Pioneer, of the right to a farm. He could not afford the costs involved in surveying the land. Instead, he obtained grants of land, ‘squatting’ on a piece of ground near the town. He built a mud hut and christened his modest construction, ‘The Hilton’ because it was there that he hoped to establish a hotel. The plan was to take advantage of the town becoming an important staging-post between Mashonaland and Mozambique. [The young nurses Blennerhassett, Sleeman and Welby themselves moved from Fort Hill to Old Umtali in December 1891]

Conditions for Bowden’s return from Fort Salisbury in February 1892 were hazardous because there was a strong driving rain at night and drizzle during the day. He was at one point thrown from the post-cart in which he was travelling, a subsequent ‘Roll of Pioneers’ recording that he died as a result of being “crushed by a wagon near Umtali.”

The day after Bowden’s arrival at Umtali, Saturday, 13 February 1892, he was on the cricket field. The towns-people would not entertain any thought of his missing the game. It was, after all, the first match to be played in Manicaland and it was quite something to have the famous Surrey cricketer playing. The contest between the Chartered Company and the Rest of Manicaland was staged in the main street. There was no matting, simply bare earth. A few weeks earlier on Boxing Day 1891, an athletic sports meeting had been held at the same venue. The proud comment was made in the Cape Argus that: “Umtali streets are not Threadneedle streets; we are not hard up for space in Manicaland.”

Captain Lyndhurst Winslow, the former Sussex player, led the Rest of Manicaland side which included several members of the Pioneer Corps, namely Bowden, Arthur Puzey, Alexander ‘Sandy’ Tulloch, George Logan and William Clinton. The Chartered Company batted first, but their innings was a disaster. After being 25 for 4, they collapsed to be all out with no addition to the score. Robert Talbot-Bowe, batting at number five, was left 0 not out and there were four ‘ducks’. The side batted two short because players had slipped away for a few minutes, not expecting the innings to disintegrate the way it did. Captain Winslow and the Reverend Sewell captured three wickets each; Bowden, keeping wicket, recorded a stumping.

Captain Winslow, who opened the innings for the Rest of Manicaland, was the only player to stay at the wicket for any length of time. He scored 33 out of a total of 63. Bowden was clearly not well: “it was observed that he was in bad form” and batted at number six. He was bowled for one, swinging wildly at a delivery from Talbot-Bowe.

In their second innings, the Chartered Company fared better, reaching 51. Bowden sent down a few deliveries. It was an ordeal for him, but he plucked up his last vestige of energy to take four wickets (all clean bowled). Winslow claimed three and Sewell two. This left the Rest of Manicaland fourteen runs to win the match. Logan and Puzey notched up the runs without being parted to give their side an easy victory by ten wickets.

The effort involved in playing the match probably affected Bowden’s condition, although it was thought that he would feel better after some rest. Sadly, this was not the case. On the Monday, his condition deteriorated alarmingly, and he had an epileptic seizure and was conveyed to the hospital. The news spread quickly in the small town and there was great concern.

Nurse Rose Blennerhassett wrote: “The first case we lost in Old Umtali was Mr Montague Bowden, the well-known cricketer. He was singularly handsome, popular, and with every chance of success in trading and prospecting enterprises… His temperature rose to 107 and he passed away very peacefully on the fourth day after his admittance. On account of the heat it was necessary to keep the doors and windows of the room, where he lay, wide open, and a man with a loaded revolver sat there all night to protect the corpse from wild beasts. Next day he was buried, the whole community attending his funeral. With great difficulty, owing to the scarcity of wood, a coffin had been made out of whisky cases. It was covered with dark blue limbo. A card, bearing his name and age, was nailed to the lid. Beneath it we placed a large cross of flowers. The remains were carried across the compound to a bullock-cart, and the melancholy procession started. We lingered to watch it wind across the plain, until it disappeared from view, and then with sad steps returned to the wards.”

Bowden died on Thursday, 19 February 1892. The District Surgeon, Dr JW Lichfield, a fellow Pioneer, signed his death notice, recording the cause of death as epilepsy. Subsequent sources have linked his death to the fall from the post-cart, exhaustion, alcohol and sunstroke. It took time for the news to become known. Lionel Cripps, a local farmer, later the first Speaker of the Southern Rhodesian Legislative Assembly, did not hear of the cricketer’s death until Friday, 27 February, noting in his diary, “Poor Bowden died in Umtali.” The news was brought to Cripps by the recently-employed ‘Paddy’ O’Toole VC who had been in the town collecting supplies.

In Cape Town, Cadwallader did not want to believe the news. Perhaps too much rested-on Bowden’s return to South African cricket. As a result, he created unnecessary anxiety by cabling a message overseas that: “from statements by gentlemen who recently arrived in Cape Town … there is happily reason to view the reported death of Mr Bowden with a great amount of reserve.”

Bowden left a sum total of £1 15s 6d, which was held by the master’s Office. His real assets were worth more as they included the farm he was entitled to as a former member of the Pioneer Column. His father pursued the right to secure the farm and used his influence to obtain the services of Dr Jameson, the country’s administrator. It mattered little because Jameson was quickly tied up in his infamous Raid of 1895. The rebellion against the government of Paul Kruger also caused John Bowden to switch attention to another son, Frank, one of the soldiers who participated in the ill-fated invasion. Frank was taken prisoner at Doornkop and repatriated to England where he was called to the trial in London.

It was a stressful time, but the fervour of Frank Bowden’s devotion to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) was not undermined by such ill-fortune. On his return, he joined the British South Africa Police and resumed the task of following up details related to his brother’s estate. His father had requested that a farm be selected in the most favourable locality with the intention being to sell it at a good price. Lawyers representing him obtained land in Matabeleland and carried out his request. As a result, on 13 December 1901, JH Kennedy signed the ‘Account of the Administration and Distribution of the Intestate Estate of the late Montagu (sic) P. Bowden’. Bowden left his father and mother equal amounts of £36 9s 4d.

His grave is not identified on the Old Umtali cemetery plan indicating that when the BSAC surveyor drew up the plan in 1913; twenty-one years after Monty Bowden’s death, all memory of its whereabouts and its existence as the earliest grave had been forgotten.

And now an account from one of the Umtali nurses, Rose Blennerhassett “Sister Aimée” which T.V. Bulpin quotes in his book To the Banks of the Zambezi. Bulpin puts the quote under a general heading of 1893, but Bill Jehan sent me their marriage details for 24 December 1891. Bulpin says: one of the nurses at Old Umtali has left us some account of Christmas in that little mining and frontier town. It was a celebration which certainly had its moments, although it is only fair to state that it was really a dual occasion. Love had come to the little town of Umtali. Sister Welby “Sister Beryl” and Dr J.W. Lichfield, the local medical officer, were to marry on Christmas eve, and after months of interested, speculative (and some jealous) observation by the local population, the culmination of the romance would certainly have been a reason for jollification, even without Christmas.

“Christmas day dawned in an already excited community” wrote Nurse Blennerhassett rather sourly, “I do not think it is exaggerating to say that by noon everyone in the place, with the exception of three or four men, was very tipsy indeed.” The day had been set aside for sport. In Old Umtali this meant that the main street, the only area in the eastern mountains so far cleared of bush, was converted into a sports field. Here the local fun and games always took place, with full facilities provided for thirsty athletes provided on both sides of the street.

“Before the afternoon was far spent,” continued Nurse Blennerhassett, “the good-natured stage of drunkenness was replaced by the quarrelsome one. A free fight took place round the too-well supplied refreshment wagon.”

The magistrate ordered the civil commissioner to be arrested. The civil commissioner retaliated by suspending the magistrate. At the height of these proceedings, Sister Welby and her doctor were united a young clergyman by the name of Rev. J.R. Sewell, who had come to the eastern mountains to assist Bishop Knight-Bruce and found himself stranded there, with the Bishop away sick in Britain, with no money, no authority, and prospects so scant that he talked plaintively of working his way back before the mast to Britain.

“I must say” primly wrote Nurse Blennerhassett, “that the appearance of this gentleman was a great shock to us. He wore a helmet, a flannel shirt, and coarse blue trousers, much too short, of the type dear to navvies. These were held in place by a large scarlet handkerchief, which however did its work so indifferently that Mr Sewell was always hitching up his trousers like a sailor in a pantomime.”

Mr Sewell, we are told, afterwards “chucked his orders” and went into partnership with a Jewish tavern keeper, an occupation which the young man doubtless found more profitable than what he had referred to as “bible-punching.” Bulpin writes: “So far as Old Umtali was concerned, Sister Welby was well wed, the New Year [1893] seen in with the same celebration which had started at Christmas, and the main street of the cheerful little town so cluttered up, in the course of time, by cricket wickets, soccer goalposts and hurdles left over from track meetings that, after persistent complaints by shoppers who objected to jumping over such things, the local sanitary Board was most reluctantly compelled to request the athletes to disport themselves elsewhere.”

Acknowledgements

http://webs.wofford.edu/davisgr/PioneerCemetary/index.htm

ORAFs website: The Tragic Tale of Monty Bowden by Jonty Winch

J. Winch. England’s Youngest Captain, the Life and times of Monty Bowden and two South African Journalists. Windsor Publishers, 2003

[1] www.theguardian.com/sport/2015/jul/21/the-spin-forgotten-story-englands-youngest-test-captain by John Ashdown

R. Blennerhassett and L. Sleeman. Adventures in Mashonaland. Books of Rhodesia Volume 8, 1969

D.C. de Waal. With Rhodes in Mashonaland. Books of Rhodesia Volume 36, 1974

Bill Jehan for the marriage certificate of Sister Welby “Sister Beryl” and Dr J.W. Lichfield

T.V. Bulpin. To the Banks of the Zambezi. Nelson 1965.

When to visit:

All year around

Fee:

Not applicable

Category:

Province: