How Mutare and Manicaland were annexed from the Portuguese

First – a tribute

In carrying out the background research I have been greatly impressed by the articles written by J.C. Barnes, who taught at Umtali Boys’ High School and published both in Rhodesiana and Zuro – the Magazine of the History Society, Umtali Boys’ High School. All his articles are models of how local history can be made interesting and are extremely well-researched and clearly written.

Introduction

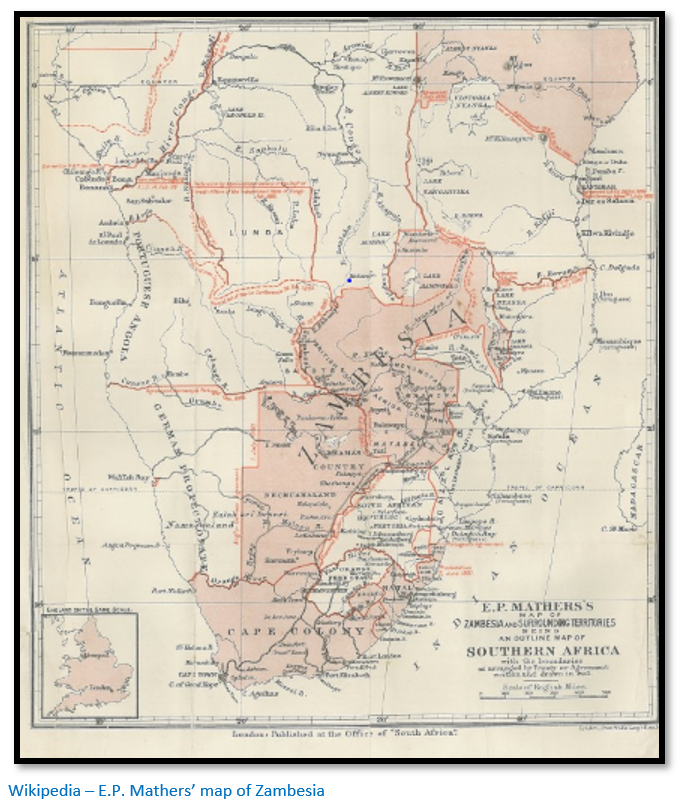

This has been written to supplement another article on ‘The Pink Map’ [listed under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] which considers the diplomatic wrangling associated with the ‘scramble for Africa’ and considers in greater depth the manoeuvres on the ground between the British South Africa Company (BSACo) and the Companhia de Moçambique for control of Manicaland and Gazaland prior to the establishment of the current boundaries between present-day Mozambique and Zimbabwe.

The BSACo occupation of Mashonaland in 1890 was an attempt to oust both the Portuguese in the east and to surround the Afrikaner Republics in the south. The Royal Charter of 1889 stated that the Company’s sphere of operations included: “the region of South Africa lying immediately to the north of British Bechuanaland and to the north and west of the South African Republic and the west of the Portuguese dominions.”

The Foreign Office under Lord Salisbury made it plain that it would only recognise the BSACo’s claims to Manicaland and Gazaland if they could demonstrate “effective control” or managed to sign treaties with the local chiefs that occupied these areas.

Initially, the Mashona people saw the 1890 settlers as migratory traders, like the Portuguese had been, and were prepared to sign treaties in the belief that it would not be long before they moved on again. However they realised things were very different when land was pegged out, an administration was set up and demands began to be made on them for labour on farms and mines. The position of Shona Chiefs was also threatened when cattle began to be demanded in lieu of hut tax and Native Commissioners were appointed to run the administration in the districts.

The situation was particularly difficult for Chief Tendai Mutasa who was caught between the British South Africa Company, (BSACo) the African Portuguese Syndicate, the Companhia de Moçambique and the Portuguese Government as without the military forces of Lobengula and Gungunhana he could only befriend each of them to their face and deny them as soon as they had gone.

Portuguese in Manicaland

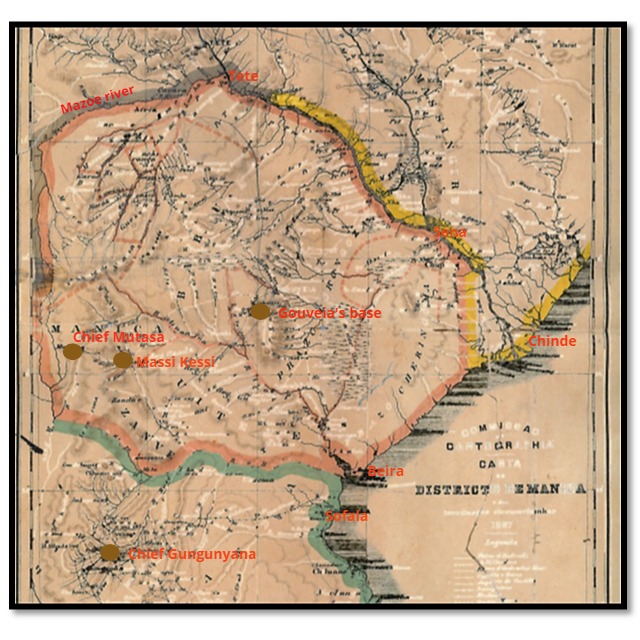

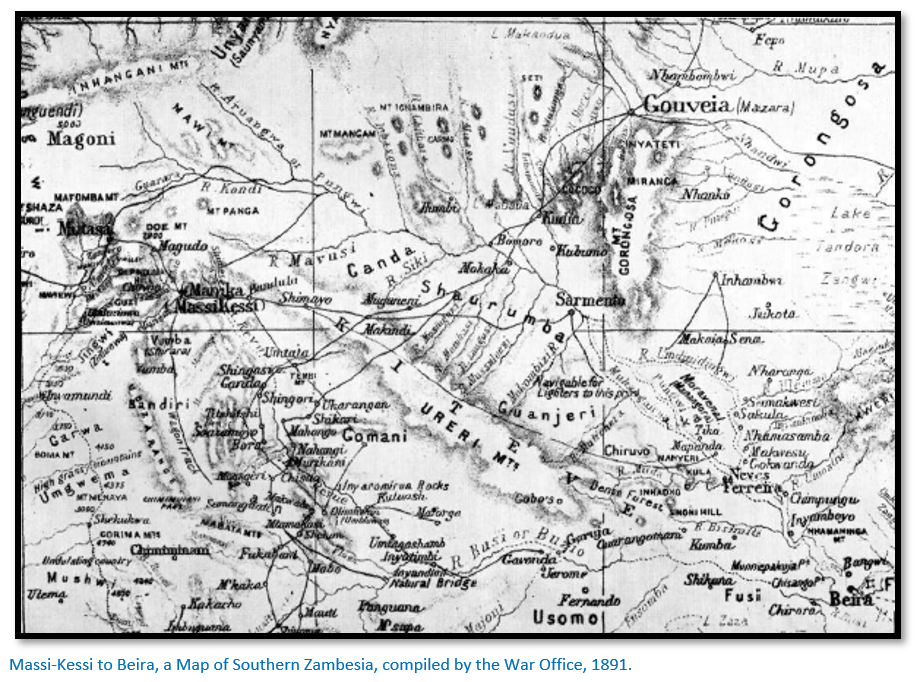

Gold-mining had taken place in Mashonaland and Manicaland prior to the arrival of Portuguese ships at Sofala in 1502 and this article focuses on Portuguese occupation of Manicaland since the nineteenth century. In 1878 Capt. Joachim Carlos Paiva de Andrada “Andrada” an energetic soldier had obtained a mining concession from Chief Tendai Mutasa and although no mining resulted become the first European to enter Manicaland in sixty years. Through the Anglo-Ophir Company he obtained a new mining concession in 1884 which became part of the Manica district proclaimed in June 1884 by the Portuguese authorities with Massi-Kessi or Macequece as its district capital and which extended as far west as the Mazoe River. See the Portuguese map of 1891 below.

Andrada travelled into northeast Mashonaland and visited Chief Chingaira Makoni east of present-day Rusape where he planted the Portuguese flag and planned further expeditions to the Mazoe (mow Mazowe) and Hunyani (now Manyame) rivers in an attempt to further Portugal’s claims to territorial legitimacy within the interior.

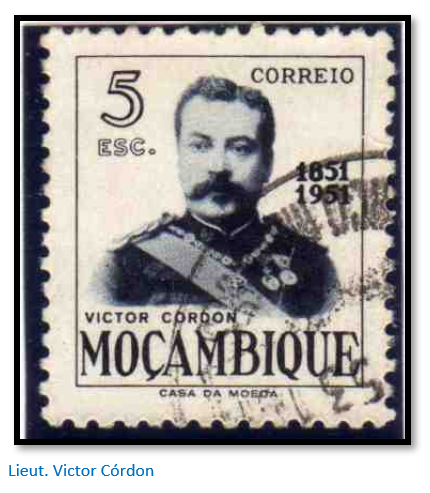

Lieut. Victor Córdon, was a Portuguese military officer of the Portuguese and after service in Angola was sent to Mocambique to explore the interior and to provide legitimacy to the Portuguese territorial claims to the interior. He headed an expedition into the Zambesi valley reaching the junction of the Sanyati (now Munyati) and Umfuli (now Mupfure) rivers where he erected a stockade. Córdon and Andrada negotiated many treaties with Mashona chiefs which were recognised by the establishment of the new Portuguese district of Zumbo in November 1889 which extended the boundary of Manica District as far west as the Umfuli (now Mupfure) river and to the Sanyati river from its junction with the Umfuli. This activity continued into 1890 when the Pioneer Column entered the country at Fort Tuli. Córdon returned to Lisbon in April 1890 to great public enthusiasm.

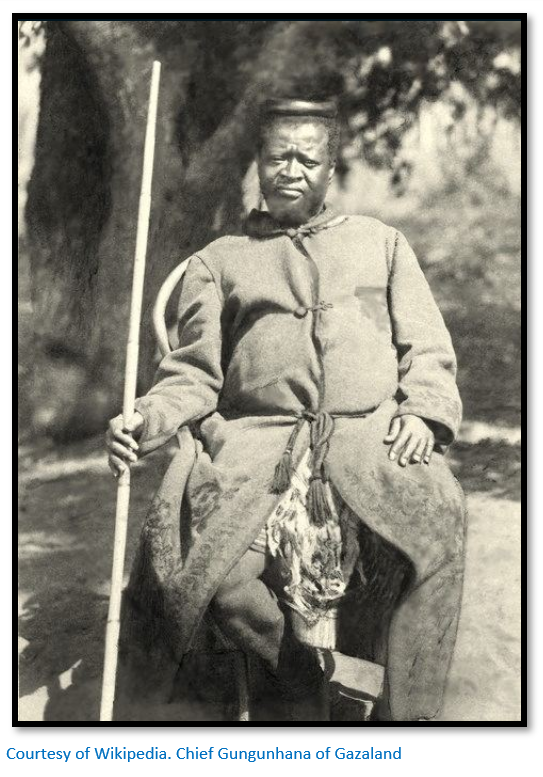

Whilst at the Umfuli-Sanyati junction Lobengula had written to Córdon asking: “by what authority are you are doing this in country that belongs to me. I am your friend. Lo Bengula.” This area of Mashonaland may have been subject to Lobengula’s writ, but to the east his impi’s reach seldom extended as far as the Sabi (now Save) river. On the other side of the Sabi river Gungunhana’s rule was prevalent; his capital at Mossurize, now Espungabera on the Mozambique side of the border from Mount Selinda in Zimbabwe.

Initially Rhodes and the BSACo had little interest in this area called Gazaland and focused on Manicaland and its easy access to the Indian Ocean at Beira, but it became increasingly clear that Mutasa owed allegiance to and paid tribute to Gungunhana and not Lobengula and therefore Rhodes attention began to concentrate on Gazaland as well.

How successive concessions recognised the authority in Mashonaland of Lobengula, Portugal and local Mashona chiefs

The Pioneer Column had begun its march from Fort Tuli on 6 July 1890. The Rudd Concession which had been signed by Charles Rudd, James Rochfort Maguire and Francis Thompson as representatives of the BSACo and by King Lobengula as representative of the amaNdebele nation gave the company exclusive prospecting and mining rights in those parts of Matabeleland and Mashonaland which were subject to the writ of Lobengula. However Lobengula’s authority did not extend east of the Sabi river as noted previously and this meant the BSACo technically did not have prospecting and mining rights here, moreover the area was claimed by the Portuguese.

Prior to this in 1887 Frank Johnson had received permission to prospect as far as the Mazoe Valley and in August of the following year the Northern Goldfields Exploration Company had sent him to Lisbon where he had obtained a concession to prospect and mine for gold along the Mazoe river from the Companhia de Moçambique.

Selous journeying through Bechuanaland on his way to Cape Town in January 1889 met Frank Johnson and was persuaded to join the Northern Goldfields Exploration Company which promptly changed its name to the Selous Exploration Company. Selous was requested to travel to the Mazoe Concession once the rains had ceased. In the interim Selous went to England and whilst there wrote an article for the Fortnightly Review praising the gold prospects in Mashonaland but also stating: “there are numerous tribes of Mashunas “sic” who are in no wise subject to Lo-Bengula. They pay him no tribute…” This was not what Rhodes wanted to hear and the Fortnightly Review’s Editor was forced to tone down these statements much to his Selous’ annoyance.

On his return to Cape Town Selous found out that the Portuguese had cancelled their Mazoe concession of 1888. Undeterred, the Selous Exploration Syndicate sent Selous via Tete and the Zambesi river to persuade the Mashona chiefs in the Mazoe Valley to sign a new concession with their syndicate.

Although the Korekore Chief Negomo would not sign a concession with Selous, his headmen Mapondera and Temaringa were prepared to sign; moreover, they stated they were entirely independent and had never paid tribute to Lobengula, or the Portuguese. This created a problem because now the territorial claims of Lobengula, Portugal and local Mashona chiefs had been recognised through successive concessions.

Then the BSACo learned that Chief Tendai Mutasa in Manicaland paid tribute to Chief Gungunhana in Gazaland and had signed treaties with the Companhia de Moçambique.

Soon after both Johnson and Selous allied themselves with Rhodes; however the detail of this will be dealt with in another article on the Rudd Concession. Selous was recruited as the intelligence officer to the Pioneer Column and paid £2,000 by Rhodes with the specific intention of preventing him from writing any more articles that stated that any Mashona chiefs were independent of Lobengula.

Anglo-Portuguese Treaty of 20 August 1890

Negotiations began on 6 July, the day the Pioneer Column set off from Fort Tuli and were concluded by 20 August, the day after the Pioneer Column left Victoria. Although this treaty was never ratified by the Portuguese its terms were also unfavourable to Rhodes as one of the provisions was that the area of present-day Melsetter, now Chimanimani, Mutare and part of Nyanga were considered within the Portuguese sphere of influence and the Sabi river was recognised as the Portuguese boundary.

Rhodes was appalled at the terms and cabled the London directors: “cannot too strongly urge upon you; you must abandon the agreement.” He had read the terms: “with great surprise, and with the utmost disappointment…and they must inform the Foreign Office that having now seen the treaty I strongly object to it and hope they will take this opportunity to drop the whole matter.”

The Portuguese were equally upset; they could not sign further treaties on any territory south of the Zambesi river without the consent of Britain.

Rhodes’ brief to A.R. Colquhoun the Administrator-designate of Mashonaland

If the Foreign Office was clear that the Sabi river indicated the extent of Lobengula’s authority in Mashonaland and the boundary for the Rudd Concession, Rhodes choose to ignore this view.

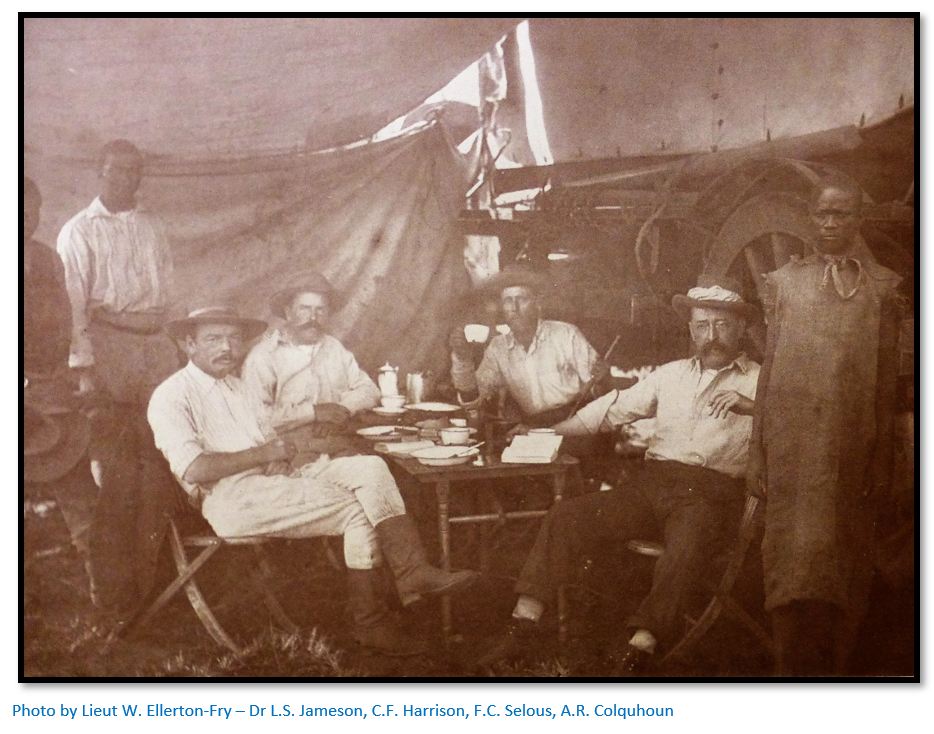

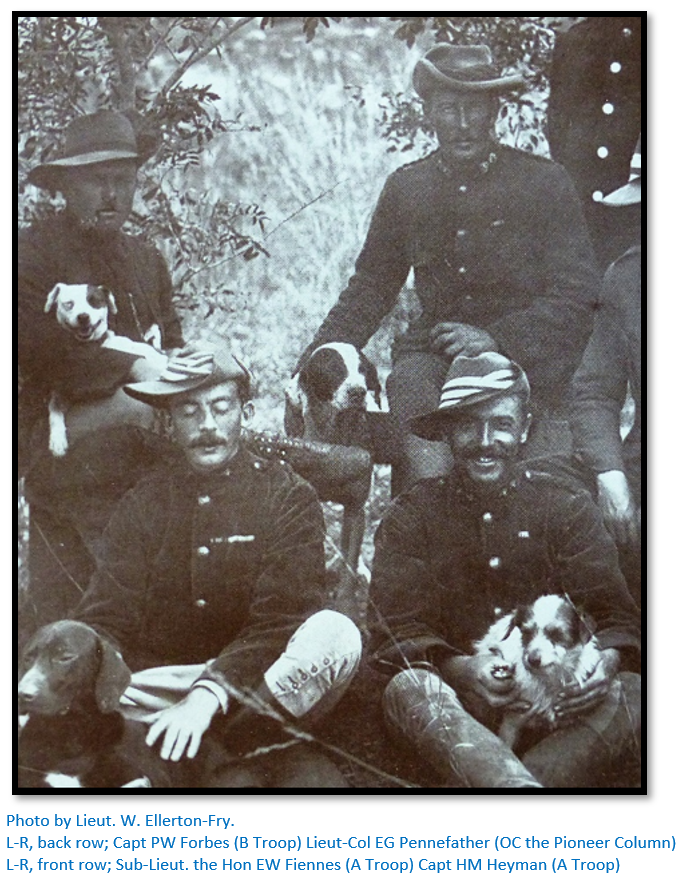

On 3 September soon after the Pioneers Column had reached Fort Charter A.R. Colquhoun, Administrator-designate of Mashonaland, accompanied by F.C. Selous, C.F. Harrison and seven BSA police from A Troop under Lieut. Adair Campbell, hurried to Chief Mutasa’s kraal to seek a concession extending the BSA Company’s influence over Manicaland. Dr L.S. Jameson, Rhodes’ personal representative, had expected to accompany the party but he had a fall from a horse breaking some ribs and was forced to return. Many prospectors at the time had convinced Rhodes that the gold reef which he had expected in Mashonaland did not run north-south, but west-east into Manicaland. No such reef was found, but Rhodes was determined to secure the area.

Of course none of the party on the way to see Chief Mutasa were yet aware of the Anglo-Portuguese treaty of 20 August which defined the Sabi river as the boundary.

In an article in Rhodesiana Publication No 9 on A.R. Colquhoun, J.A. Edwards quotes the memorandum of instructions given by Rhodes to Colquhoun on 13 May 1890 in which para 4 states: “As soon as practicable after entering Mashonaland, you will, accompanied by Mr Colenbrander (as Interpreter) and a small escort of Police, should you think it advisable to take them, visit the Chief of the Manica country, and obtain from him on behalf of the Company, a treaty and concessions for the mineral and other rights in his territory…You will endeavour to achieve the right of communication with the sea-board, reporting on the best line of railway connection with the littoral from Mashonaland…On returning from Mashonaland, for the purpose of taking over charge of the Administration, you will, if advisable, leave a representative with the Manica Chief.”

Chief Mutasa treaty negotiated on 14 September 1890

Colquhoun attempted to establish if Chief Tendai Mutasa had signed a treaty with the Portuguese. This he denied, Arthur Keppel-Jones stating Mutasa said they could ‘cut off his right hand’ if he lied, although he admitted to giving the Portuguese the right to dig for gold. The treaty was signed on 14 September giving the BSACo exclusive prospecting and mining and infrastructure development rights in Mutasa’s territory and the chief also agreed: “not to enter into any treaty or alliance with any other person, Company, or State, or to grant any concession of land without the consent of the Company in writing, it being understood that this Covenant shall be considered in the light of a treaty or alliance between the said nation and the Government of Her Britannic Majesty Queen Victoria.”

In return Chief Mutasa would receive £100 per annum, or the equivalent in trade goods in which muskets, powder and caps were specified, the BSACo would appoint a company representative and defend Chief Mutasa against any attack.

In a letter to his mother Lieut-Col. Pennefather comments on Colquhoun’s return to Salisbury on 14 October after having obtained the signed treaty agreement. However they were not to know Chief Mutasa had then secretly informed Baron Joa de Rezende, the representative of the Companhia de Moçambique at Macequece, that he had only signed the treaty under duress.

Subsequent treaty disputes with Chief Tendai Mutasa

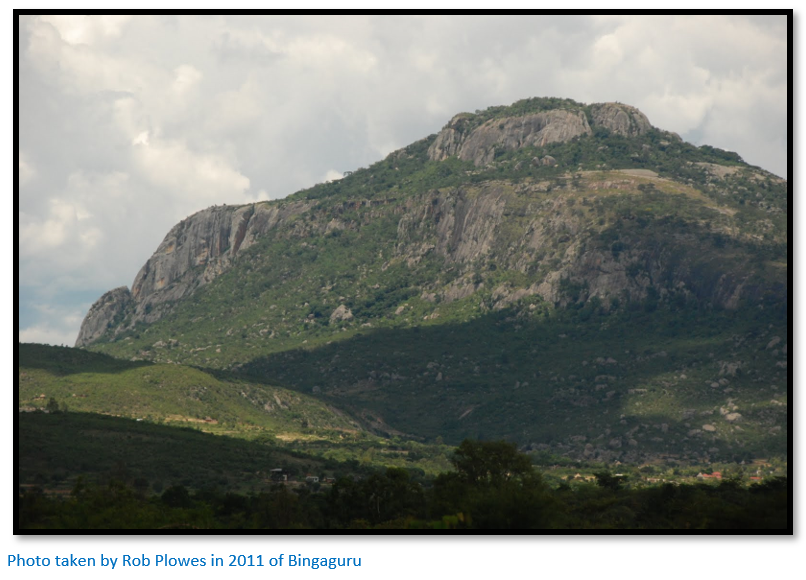

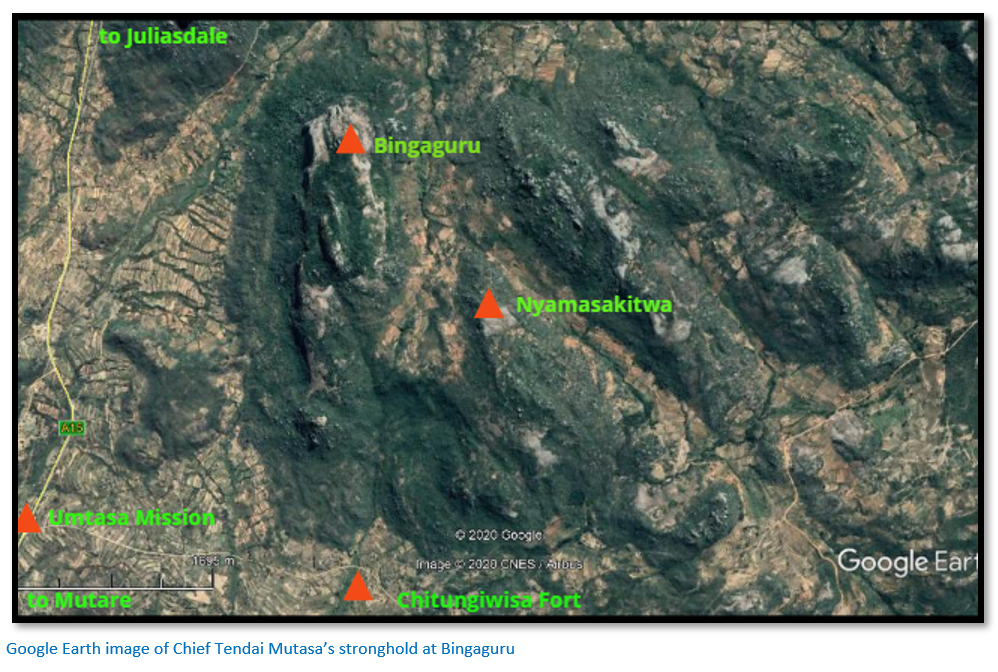

The BSACo’s dealings with Chief Tendai Mutasa were not the first; we have already noted the Portuguese alleged that he had signed a treaty with them in 1874 or 1875, had his status as Chief recognised at Sena and received a Portuguese flag which Andrada had raised at his fortress at Bingaguru in 1889. George Wise agreed a mining, cultivating and trading concession with Chief Mutasa on 3 November 1888 in exchange for two hundred cotton blankets per year. As the document was lost, it was replaced a year later and this time Chief Mutasa demanded wool blankets and the concession was in the name of the African Portuguese Syndicate represented by Reuben Beningfield.

Even before then JC Barnes in his Zuro article quotes Francis Pasipanodya and Rev. Sells as stating as early as the 1830’s during Shangaan raids in the Mfecane Chief Umtasa was compelled to move from his former kraal at Chitungiwiza to Bingaguru hill which he fortified.

Barnes then quotes Beningfield: “We were requested by Umtasa, the King of Manica, to pay him a visit…He resides in a mountain stronghold [Bingaguru…the biggest mountain] rising in three tiers, covered with huge boulders and almost impregnable. We had to crawl through tunnels in our ascent, and on the plateau, where little villages are situated, massive stockades with gates which are locked at night, surround them.”

The wool blankets took longer to buy and in December 1890 when Herbert Taylor had just delivered enough wool blankets for two years’ rental he was arrested on behalf of the BSACo by Dennis Doyle although he managed to deliver the blankets to Mutasa and get a receipt. He demanded compensation for his arrest from Colquhoun and Rutherford Harris but received nothing.

Taylor was back at Chief Mutasa’s in 1891 when the syndicate he represented had a concession over land the BSACo and settlers were by now occupying. Then in 1892 Chief Mutasa told Taylor that the BSAP had burnt six of his villages destroying crops and livestock and driven out the inhabitants because they had run away after being forced to provide labour (chibaro) on local mines and farms. When Mutasa had sent messengers to Umtali, now Mutare to say the BSACo were trespassing on African Portuguese Syndicate land they were said to have been arrested.

European residents in Umtali and Penhalonga held a public meeting, at which both Jameson and Taylor were present, to demand greater security of their properties. Jameson reassured them that the concession had lapsed and that the Mutasa had told Colquhoun in September 1890 when he signed the treaty with the BSACo that he regarded the blankets from the African Portuguese Syndicate not as rent, but as a present!

In November 1892 Major J.J. Leverson, the Chief British Boundary Commissioner, interviewed Mutasa’s son and three Headmen, as the Chief was said to be ill and was told there was nothing to complain about concerning the BSACo’s behaviour.

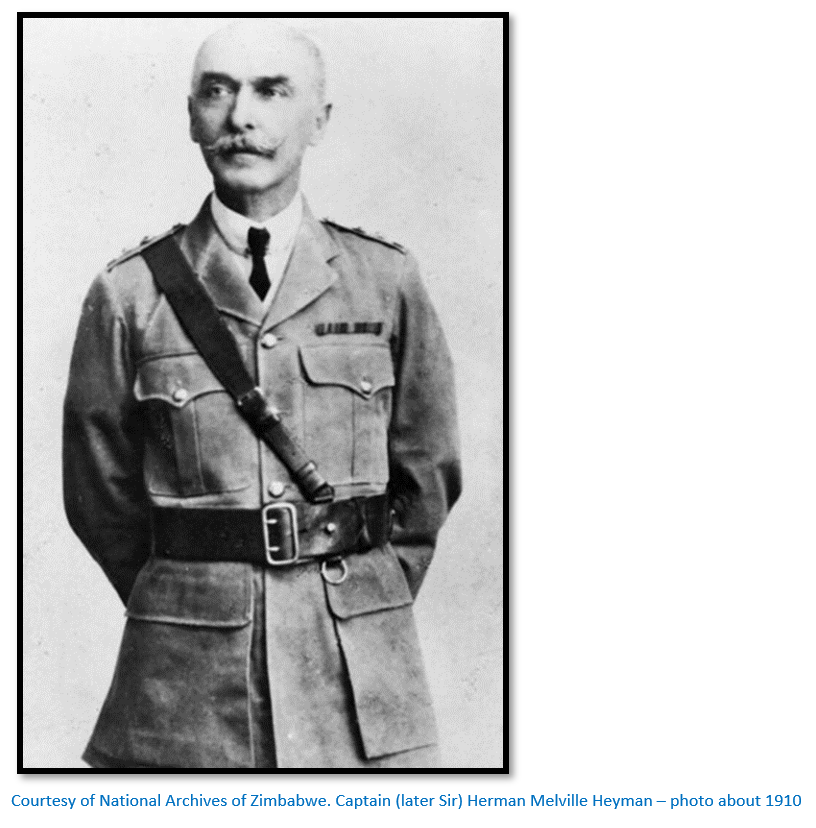

Captain H.M. Heyman then interviewed the Chief who denied any friction with the BSACo and requested that Taylor, the African Portuguese Syndicate representative, be expelled from the country. Then Mutasa denied having signed a treaty with the BSACo…this was rejected by Lord Ripon, then Secretary of State for the Colonies who accepted the authenticity of the treaty signed between Mutasa and Colquhoun on 14 September 1890.

Treaty disputes with Gungunhana

Similarly F.J. Colquhoun, no relation to the Administrator, was granted a concession by Chief Gungunhana which not only included area the BSACo regarded as within its sphere of influence but extended west of the Sabi river, but again Lord Ripon found in the BSACo’s favour.

Treaty disputes with Lobengula

Frustrated by the way that the BSACo had interpreted the Rudd Concession Lobengula gave another concession to Edouard Lippert in the South African Republic. Lippert was to make an annual payment to Lobengula for a 100 year lease which gave him the right to grant, lease, or rent land in Lobengula’s dominions which extended only as far as the Sabi river.

Just before Lippert’s concession was confirmed by Lobengula, Denis Doyle persuaded Gungunhana to sign a concession giving the BSACo: “sole and absolute power and control over all waste and unoccupied lands situated in my territory” in return for an annual payment of £300.

However unlike Lippert’s concession which was designed to extort money from the BSACo this was designed by Rhodes to frustrate the Companhia de Moçambique and the Portuguese Government and undermine the Anglo-Portuguese treaty of 20 August 1890.

The Foreign Office and Colonial Office and BSACo began negotiations; the Foreign Secretary, Lord Rosebery’s argument was that if the Portuguese could grant a concession over most of Gungunhana’s territory without consulting him, then they could hardly object if Gungunhana gave a concession to the BSACo east of the Sabi river. Consequently the British Government had no objection to this new concession.

Baron de Rezende of the Companhia de Moçambique protests and tension arises

Colquhoun sent Selous and two police troopers to Fort Massi-Kessi (Macequece) where they received a cool reception from Baron de Rezende and were informed that the party with its police troopers had been on Portuguese territory and illegally signed a treaty with Mutasa who was subordinate to Gungunhana and was therefore not free to sign treaties. A written protest was sent to Colquhoun by Baron de Rezende but rejected by him before he left for Salisbury leaving police trooper Trevor at Chief Mutasa’s kraal.

Civilian prospectors were unofficially encouraged to move into Manicaland – Maurice Heany persuaded “Sandy” Tulloch who later owned the Liverpool Mine with three months rations and ten extra gold claims to trek from Hartley Hills to Manicaland and Sgt-Major Montgomery and four police troopers from B Troop left Salisbury for Mutasa’s kraal. Soon Selous who was road-making into Manicaland sent a message to Colquhoun that the Portuguese were preparing to move a large armed force into Manicaland. Capt P.W. Forbes was told to get down to Manicaland as soon as possible to secure further territory under Mutasa’s concession and sign further treaties with chiefs living nearer the coast.

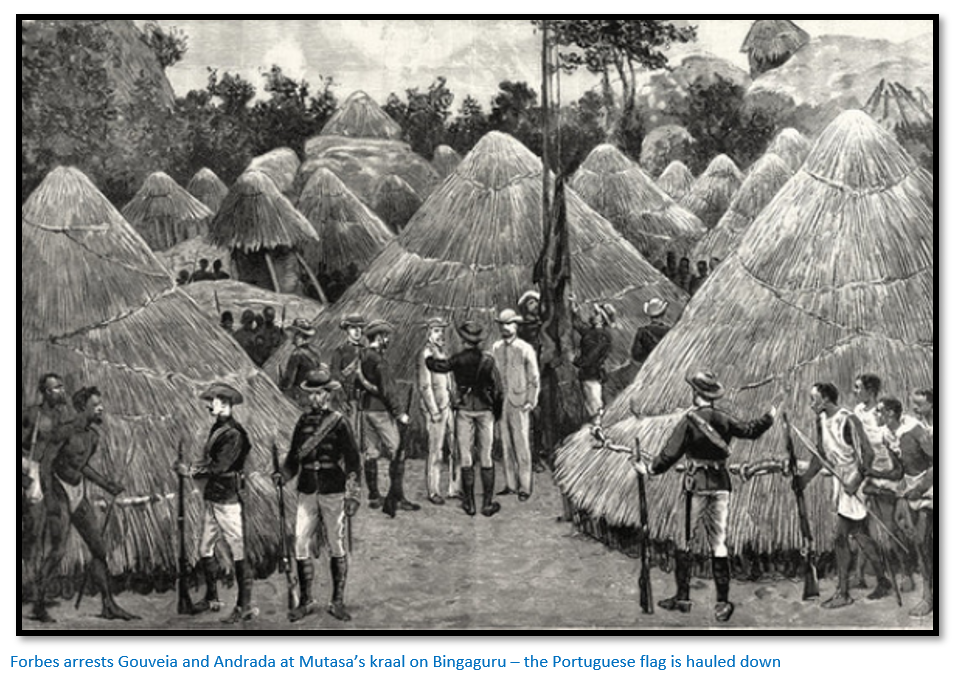

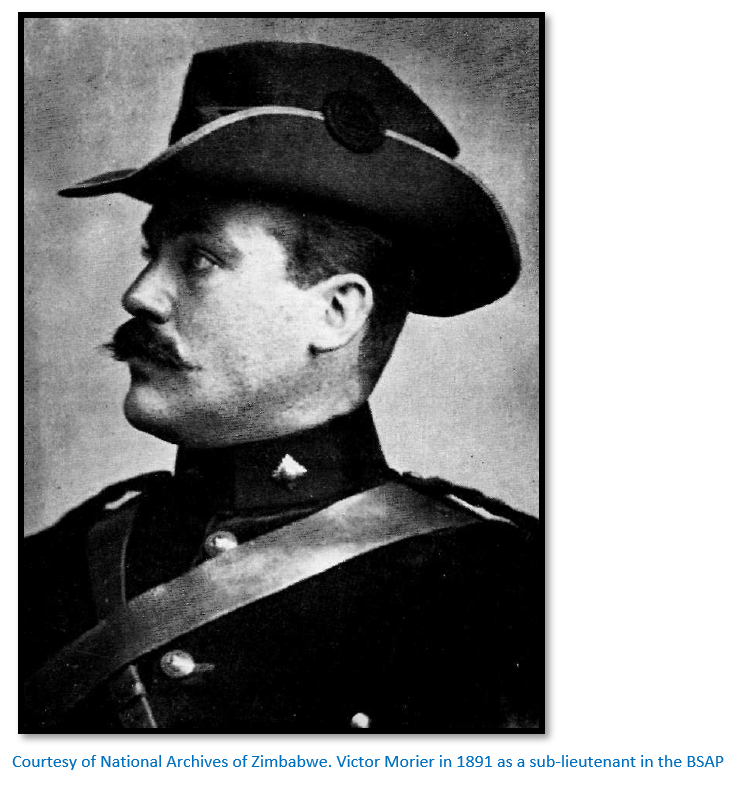

The news of the treaty had considerably annoyed the Portuguese and tension began to escalate in the area. The Governor of the province of Gorongosa, a Goanese named Manuel Antonio de Souza “Gouveia” and Col. Paiva de Andrada had arrived with two hundred armed natives at Chief Mutasa’s kraal to force him to change his allegiance. Gouveia had past form at terrorising local chiefs and coercing them into submitting to Portuguese rule. Victor Morier the BSACo interpreter commented: “treaties are easy enough got in these parts with a pair of old breeches.”

The police troopers at Mutasa’s kraal played for time until Forbes and Fiennes and their twenty-five police troopers arrived.

On 6 November Forbes sent Graham and two police troopers to Macequece with a message stating the Portuguese should get out of BSACo territory. The Portuguese told Graham the demands were too absurd to answer; the land belonged to Portugal and the BSACo forces were far too small to resist them. “As to force, if I chose with one sweep of my hand I could wipe you all out of Mashonaland.”

Portuguese forces occupy Chief Mutasa’s kraal

On 8 November Gouveia established himself at Chief Mutasa’s kraal with his 270 hundred armed followers and when Graham delivered a message he was told: “No Inglese would turn him out.” Gouveia was soon joined by Baron de Rezende, Andrada, a French engineer de Llamby and reinforcements making a Portuguese force of over three hundred.

The BSACo police troopers had been joined by Hoste, Tyndale-Biscoe and other troopers bringing the BSACo strength up to fifty.

Chief Mutasa about to backtrack on the BSACo treaty

On 15 November 1890, Andrada held an indaba at Chief Mutasa’s kraal at which the chief was persuaded to renege on his recent treaty concession with the BSACo. Local prospectors at Penhalonga; Messrs Harrison, Harrington, Harris, Campion, Moodie and Maritz were summoned to Bingaguru to witness Chief Mutasa swearing allegiance to Portugal. Harrison had been told the day before by Andrada that the Portuguese would expel the BSACo from Mashonaland and destroy Fort Hill. They were called into the chief’s enclosure as witnesses, but Mutasa refused to admit that in 1875 he had given Gouveia an elephant tusk filled with soil, signifying allegiance when Gouveia had defended him from raids by Chief Chingaira Makoni.

Victor Morier and a police trooper left from Fort Charter and covered the 250 kms in 5 days arriving on 13 November. Morier wrote: “When I got my orders to push on here I was ahead of the waggons. Consequently I am here with nothing but one horse blanket and a toothbrush, besides a dirty white shirt, bottomless breeches and sole-less boots and a patrol cap and have not the least hope of getting anything, as no supplies can reach the coast this way.“

On arrival they found Capt P.W. Forbes, “skipper” Hoste, Tyndale-Biscoe, Graham, Shepstone, Dennis Doyle (the interpreter) Baumann (a newspaper reporter) eight other police troopers and four civilian prospectors; King, Mahan, Suckling and Ogilvie – a total of twenty-one. Colquhoun on hearing that Andrada and Gouveia were at Mutasa’s kraal had instructed Forbes: “If force is directly used against Umtasa [Mutasa] you are empowered to Occupy Macequece…Mr Victor Morier will proceed via Fort Charter, to join you at Manica for political duty.”

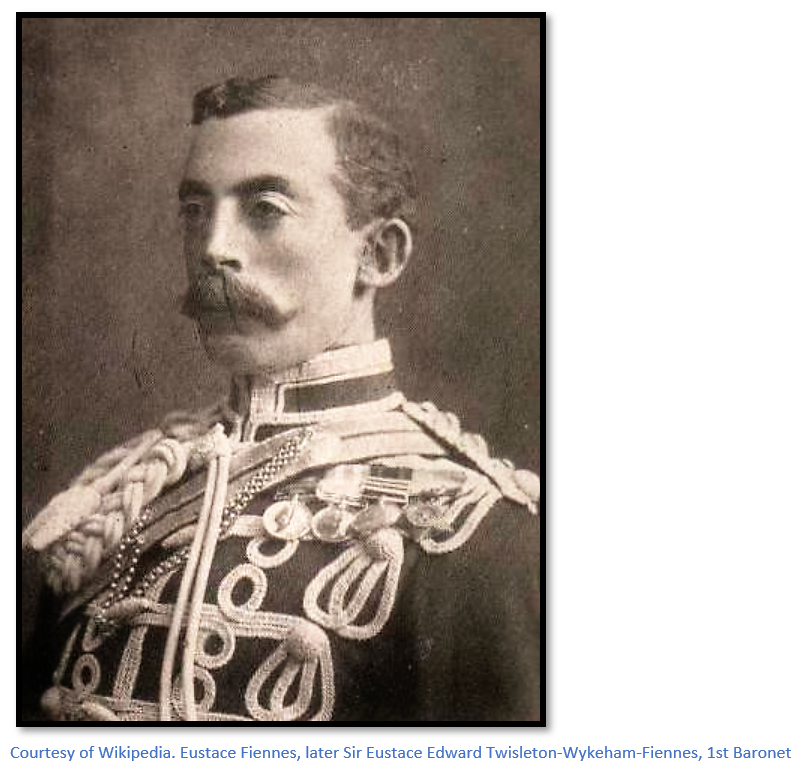

On 15 November they moved from Chitungwiza Fort three kilometres south of Bingaguru to meet up with Lieut. Fiennes and fifteen troopers who had followed behind Morier and were informed by one of Mutasa’s followers that Andrada was in the process of intimidating the chief, so according to Hoste: “we hardened our hearts and made up our minds to bag the lot while they were all together.”

Besides Gouveia’s 270 armed followers, Chief Mutasa had 1,000 men and a neighbouring Chief was present with 500 men.

The arrest of Andrada and Gouveia on Bingaguru on 15 November 1890

Forbes, Hoste, Doyle, Shepstone, Baumann, Morier, Palmer, Crawford and six police troopers were led up Bingaguru by Jomas, an interpreter. Mutasa’s armed guards let them through the gates thinking they were about to join the meeting.

The Portuguese flag had just been hoisted when Forbes accompanied by ten BSACo police troopers cautiously entered the kraal catching the Portuguese and their hosts by surprise and to their amazement arrested Gouveia and Andrada: “for conspiracy and tampering with the natives of our territory” whilst Fiennes with the remainder of the police force, dispersed their followers. Andrada protested that he was under the Portuguese flag but was nearly hit by the flagpole which snapped as Trooper Payne hauled the Portuguese flag down and Hoste wrote: “At this point his language became unprintable; however, we made a prisoner of him.”

As Forbes arrested Baron de Rezende, Gouveia made a dash for freedom but was grabbed by his trousers by Lieut. Shepstone and dragged around a hut; Forbes raced around the other side and arrested Gouveia at gun point.

Mutasa’s men thinking their chief was about to be arrested: “began humming like a hive of angry bees” until Doyle placed himself in front of them telling them they were friends who had come to free them from the tyranny of the Portuguese. As they wavered, Forbes and his men retreated through a gap in the palisade. Gouveia stuck fast and whilst two police troopers pulled from the front, Hoste put his foot “against the blunt end” and pushed him through!

Morier wrote: “They [Andrada, Rezende and Gouveia] were comfortably installed in Umtassa’s “sic” inner kraal, holding “indabas” (talkytalkies) with him and threatening him with extermination for having made treaties with us. Their band of armed bearers, 200, luckily for us, were encamped at the bottom of the hill. As it afterwards turned out, they had ordered Umtassa to attack us if we made any move against them and this he had promised to do. But we were too smart and sudden for them. Ten of us made a sudden raid up into the kraal, whilst the remainder disarmed the bearers at the bottom of the hill. We had an awful climb. It was two o’clock, with a blazing sun, and the kraal about 300 feet up, perched on perpendicular rocks. Of course it was “aupas de charge” with loaded rifles. The guards couldn’t make out what we were after and were luckily too surprised to barricade the narrow little gates in the stockade, through which one has to creep on all fours. We seized the Portuguese, pulled down their flag which was gaily floating in the middle of the kraal and proceeded to clear out as fast as we could go.”

Aftermath of the arrest

At the base of the mountain Fiennes and Tyndale-Biscoe led the remaining force to where 200 of Gouveia’s armed followers were camped. When they saw the BSACo force approaching Gouveia’s men took to the hills with their weapons.

When Hoste offered the captives a drink both Rezende and Andrada refused but Gouveia accepted saying: “I am a prisoner and it is your duty to be kind to me.”

Forbes was introduced to Andrada who jumped up and shouted: “Captain Forbes you are one damn rascal. In the future the very dogs in the street will bark when your name is mentioned.”

Morier, who spoke Portuguese listened unobtrusively outside the prisoners’ hut. As soon as they were alone Andrada said to Rezende: “This is like feeding in a robbers’ cavern and look at the brutes – eating with their fingers.” Hoste commented that this was: “distinctly unkind since we had given up all our mess-traps to the prisoners.”

Andrada and Gouveia were taken under police escort to Fort Salisbury for discussions with the Administrator Colquhoun before being escorted under parole to Cape Town. The Foreign Office noted that the BSACo had no power to make such arrests, but nothing more was done. Major A.G. Leonard in charge of E Troop of BSACo police at Tuli met many of the personalities passing through, including Andrada and Gouveia escorted by Lieut. Mundell. He described Andrada as: “a gentleman and very fine fellow” and “naturally very indignant…and in anticipation of the rumpus he is contemplating, converts himself into an insensate fury on a hot day and at the risk of bursting a blood vessel.” Gouveia, the notorious slave-dealer and villain and virtually ruler of the whole of Manica from his prazo at Gorongoza mountain: “was dressed in a striped sleeping-suit of various colours and appeared to be rather a retiring, mild-mannered half-caste gentleman - a thorough-bred Goanese; a class of people that were sometimes employed as cooks or boys in India, who make a great show of being Catholics and Christians, and a great show of being Europeans…”

Forbes captures Fort Massi-Kessi and invades Manica

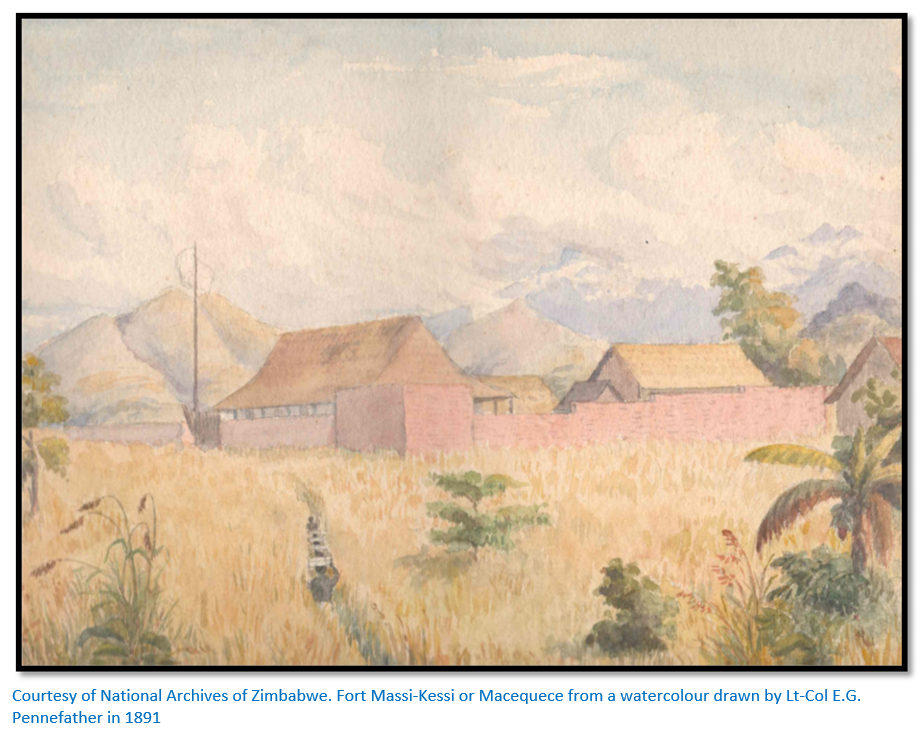

Encouraged by his success, Forbes released Baron de Rezende and de Llamby and on 17 November left with eight men for the fort of Massi-Kessi or Macequece, in ancient times known as Chipangura, but now called Manica. The thirty-five kilometre journey was only completed after the ox-wagons were left behind and the horses were led on foot over “the divide.”

They approached the fort cautiously on the morning of 19 November after being warned by local sources that a Portuguese regiment had moved in a few days previously. However a messenger approached to say the fort would lay down their arms. The garrison consisted of a corporal and a private with an assorted collection of Portuguese, French and Spanish miners – forty-five men in all. The fort was quickly occupied and the Portuguese flag replaced with the Union Jack.

Victor Morier wrote: “Sgt-Major Montgomery and myself were sent ahead to spy out the nakedness of the land and boldly rode into the place informing the Portuguese corporal and one private, who formed the garrison, that we occupied it. They were most humble and brought us food and drink. Montgomery went back to inform Forbes and I was left for twenty-four hours commandant and army of occupation. All the employees of the Mozambique Company, of which this is the headquarters, came in during the course of the day to do homage. There were seven Spaniards, several Frenchmen, all of course delighted to find somebody who talked their native tongues. Next day all the English prospectors of the district turned up, so we had a great meeting of white men. This is a fine large factory, with large stores of all kinds, gardens, etc.”

Hoste and Tyndale-Biscoe with a sergeant and four police troopers were left in charge of the fort and their prisoners although Tyndale-Biscoe soon left to find an easier route from Fort Hill which avoided “the divide” and was passable by ox-wagon. By the 23 November a pass was found: Captain Bruce and a party of police troopers went to cut a road and found themselves on the pass on Christmas Day, hence the name of Christmas Pass above Mutare.

A relative calm

Hoste now in charge of Fort Massi-Kessi soon received a letter from the Governor of Manica Province, J.J. Ferreira – clearly a man who had studied English history and called Hoste a “Saxon pirate” and “Norman robber” and threatened to hang him. The messenger inadvertently disclosed however that the Governor had been left with one officer after his forces deserted and Hoste replied that in the interests of preserving the peace the Governor should stay away from the fort…no more was heard.

On 24 November a police sergeant and ten troopers arrived at the fort; an inventory was made of all the stores which Baron de Rezende was asked to sign: “Oh, you English, you come here and steal our country and then make a fuss about a few picks and shovels.” Three days later Rezende and the prisoners were set free but not before Rezende threatened to find Forbes and: “smash him up.” Hoste remarked in his diary: “I was not particularly anxious about Forbes.”

A spontaneous approach to territorial acquisition

There was no well thought-out plan to the next phase. Hoste claimed: “as the Portuguese had been creating trouble in our territory it behoved us to retaliate.” Tyndale-Biscoe thought Forbes would leave for Beira via the Pungwe river: “to arrange with the different chiefs about a road and Doyle left for the south for the same purpose.” Morier thought the purpose was: “to make treaties with all the native chiefs” but in an earlier letter to his father wrote: “the Company…have determined to annex (Manica) make a rush to the coast and gain possession of a seaport.”

Forbes had left Massi-Kessi on 21 November with Doyle, Montgomery, Morier, Baumann and the remaining police troopers. They covered eighty kilometres in the first two days but were forced to go on foot thereafter in tsetse-fly country.

On 3 December a messenger arrived from Forbes at the fort saying he had left two police at Chimoio to maintain a communication link and that Baumann, the newspaper reporter had gone missing and was presumed to have been taken by lions.

The march had not been easy, Morier said: ”…we had an awful time…I hope never to make such another trip. We had to leave our horses fifty miles from here owing to the tsetse and do the remaining one hundred fifty on foot. ” But they had captured without difficulty a vast amount of Manica Province. Forbes had the bit between his teeth and was determined to capture all the land as far as Beira. He wrote to Colquhoun “…we shall secure the north bank of the Pungue [Pungwe] and all the country between the Pungue and Busi, and all the necessary seaboard. If I get the treaty with Sencombe (on whose land Beira is) I shall leave Morier with 3 or 4 men at his kraal to occupy under the treaty and write to the Governor of Beira, leaving the forcible ejection, if carried out at all, to be done later.” In the area between the Busi and Pungwe rivers they had concluded several mining concessions with local chiefs which included the right to build a railway.

On 29 November they were in the Pungwe Valley and about to destroy Gouveia’s base at Gorongosa and within two days march of the sea when a messenger arrived from Colquhoun ordering them to return to Massi-Kessi. Forbes was bitterly disappointed, but it was probably just as well, as he and his men were completely exhausted, their boots worn out and Forbes himself suffering from malaria. Forbes wrote to Colquhoun: “Your despatch caught me up here (Tica’s) and only just in time to stop me going down the Pungue “sic” I hoped to get boats this afternoon and should have got to Sencombe’s tomorrow…it is a great disappointment to the men being stopped just at the last moment.”

The despatch had been passed on by Hoste at Massi-Kessi as it was marked: “To be forwarded to Capt. Forbes at any expense of men and horse” and Hoste later said that if he had known of its contents, he would have delayed it! Jameson said of Colquhoun: “Damn the fellow; I got him his job.”

Lord Salisbury’s insight from Victor Morier’s letters to his father

This is Lord Salisbury’s letter to Sir Robert Morier after he received Victor Morier’s account of ‘Forbes coup’ at Chief Mutasa’s kraal at Bingaguru: “Dear Sir Robert, I am very much obliged to you for allowing me to see the enclosed letter from your son. It is most interesting – and it gives a very vivid picture of the adventure and of all its surroundings. Whatever judgements jurists or international moralists may have to form of the enterprise, it was both a striking and amusing illustration of the different national characteristics of the English and the Portuguese.”

Lord Salisbury reaches a decision on the BSACo territorial claims

This action had a profound effect on Lord Salisbury, the British Prime Minister and Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs who saw that the BSACo were firmly established in Manicaland and that the Portuguese were not. Forbes’ actions were in contravention of the ‘modus vivendi’ but on the other hand Portuguese flags had been raised at the kraals of Makoni, Mangwende, Makonde and Psanga indicating that the ‘modus vivendi’ had also been ignored by Portuguese officials.

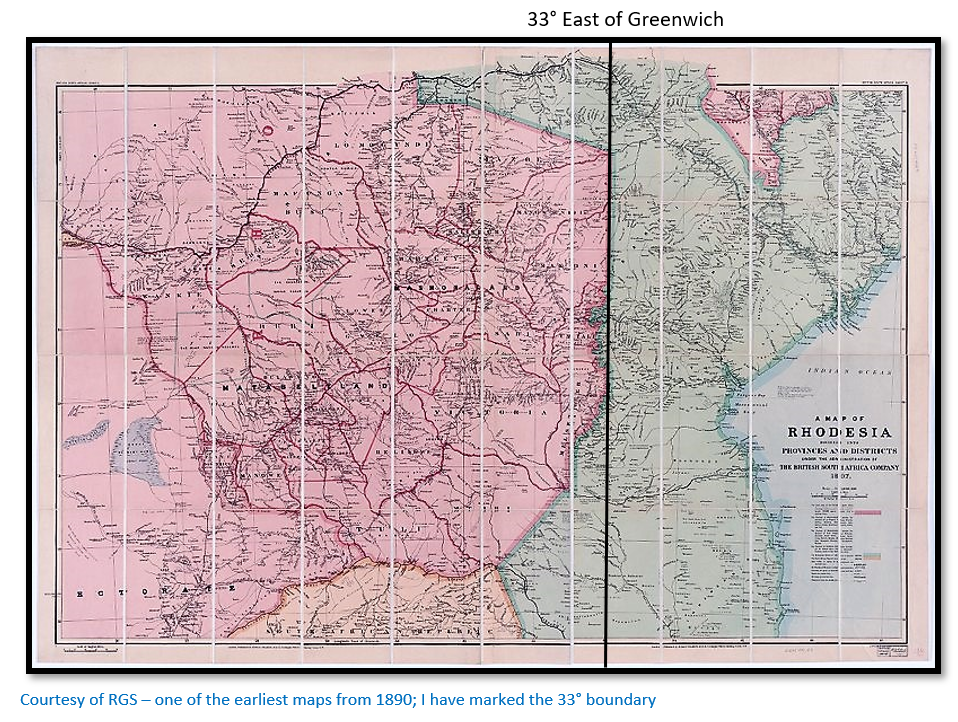

Lord Salisbury would negotiate any future treaty with Portugal on his terms – that is Portugal’s claims to the coast and Massi-Kessi would be recognised, but “archaeological” claims to the interior based on historical claims would not as no attempts had been made at government in the interior. The line of longitude 33°east of Greenwich would form the basis of the boundary.

14 November Anglo-Portuguese Modus Vivendi

An interim agreement recognising the status quo had been agreed between the Portuguese and the Foreign Office until a more definitive treaty could be negotiated which settled the boundary question once and for all…the Portuguese still assumed the Sabi river to be their western boundary. News of the modus vivendi reached Colquhoun in Salisbury on 23 November; hence the urgent despatch to Forbes. The news that Forbes advance into Mocambique had been halted by Colquhoun infuriated Rhodes who soon appointed Jameson in Colquhoun’s place as Administrator of Mashonaland.

Frank Johnson’s journey down the Pungwe river to Beira

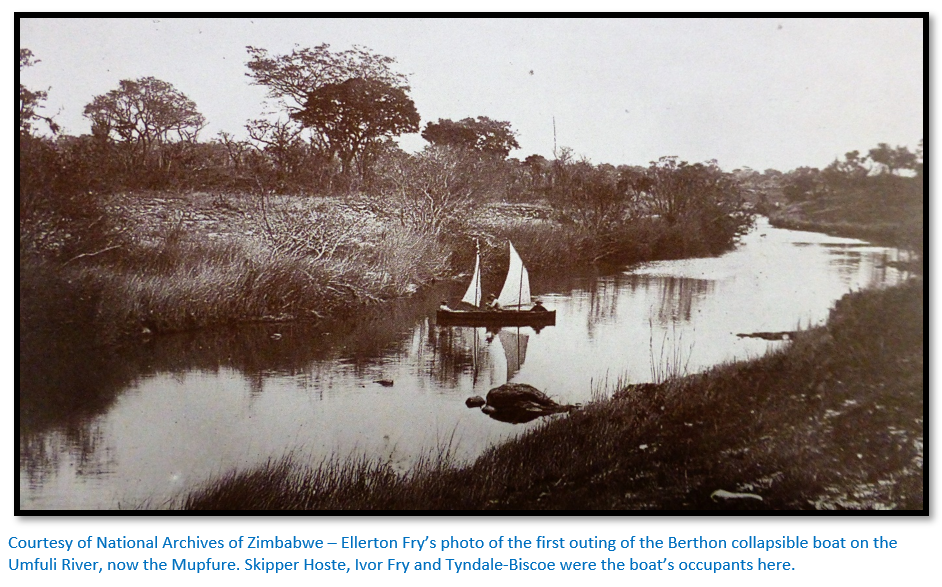

As part of the plan to claim Manicaland and a route to the sea at Beira, Johnson had included a Berthon collapsible boat in the Pioneer Column’s equipment which had its first outing on the Umfuli, now Mupfure river. On his first journey down the Pungwe river he was joined by Dr Jameson, who still had his ribs in plaster from his earlier fall from a horse, Jack their Zulu interpreter and Hay, a BSACo trooper. They left Fort Salisbury on 5 October; Troopers Morris and Human having left a fortnight before with a wagon and orders to reach Massi-Kessi.

They overtook the wagon with its boat at the Penhalonga valley near a small mining camp on the Bartissol claims which was being worked at the time by a group of English miners under a Portuguese licence. The miners knew nothing about the occupation of Mashonaland! Next day they climbed over “the divide” and reached the Fort at Massi-Kessi where they were politely received by a cool and suspicious Baron de Rezende.

They received permission to continue their journey, but no offers of help, so Mr Campion the manager at the Bartissol recruited thirty porters to carry their boat and next day they crossed “the divide” once more and decided for discretion’s sake to avoid Massi-Kessi. The next few days journey through Mandigo’s (later the site of the Beira-Mashonaland Railway maintenance shed) and Chimoio went smoothly and they reached the headwaters of the Pungwe river where they assembled their boat. There was so little freeboard with Johnson, Jameson and Hay onboard the boat that Jack was forced to return to Mashonaland.

A day’s journey on at Sarmento, Johnson knocked over the candle that Jameson was using to write up his journal with the result that the hut and all their possessions and then the entire village was burnt down! In view of this disaster the villagers meant to obstruct their onward journey, but Hay knocked out the most indignant villager with an oar and the party of three rapidly pushed off into the river. Following a tiring and hazardous trip they reached the mouth of the Pungwe where they were blown out to sea and through pure good luck ran into the steamer Lady Wood which was awaiting their arrival.

Gungunhana and Gazaland

After Andrada and Gouveia’s arrests BSACo police troopers remained at Chief Mutasa’s kraal; however the situation with Gungunhana was very different. After sending two envoys to Portugal Gungunhana had accepted a treaty on 20 May 1886 with the rank of Colonel, received payment of £200 per year, flown a Portuguese flag and accepted a Portuguese resident at his capital Mossurize. He also gave transit to Portuguese subjects across his territory, permitted mining by the Companhia de Moçambique and agreed only to accept Portugal’s claims over his territory.

However in the winter of 1889 Gungunyana made a complete volte-face by moving his capital and fifty thousand followers from Mossurize to a location one hundred and thirty kilometres north of the Limpopo mouth displacing its previous inhabitants and attacking and defeating several pro-Portuguese chiefs. In July 1890 his ambassadors in Lourenco Marque announced his independence and declared that if their territory was to be taken over they would prefer to be subjects of Britain rather than Portugal.

Rhodes had sent a BSACo representative, Aurel Schulz to Gungunhana’s new capital, who claimed to have obtained an oral treaty, much like the Rudd Concession, granting exclusive mineral and commercial rights to the BSACo in return for £500 per year and a thousand rifles and ammunition.

Rutherford Harris, the BSACo secretary charted a small steamer, the Countess of Carnarvon to deliver the arms shipment with Capt. Pawley in charge of delivery. The steamer went up the Limpopo river and the arms were unloaded after Pawley gave a personal bond of £2,000 for customs duty to the Portuguese officials on 21 February 1891. The steamer then returned to Durban for fuel and supplies.

In no time at all after reaching Cape Town following his journey down the Pungwe river with Frank Johnson, Dr Jameson was back in Mashonaland where he waited just three days at Fort Salisbury before setting off with Denis Doyle and Dunbar Moodie and arrived at Gungunhana’s new kraal on 2 March 1891 after an exhausting and difficult journey of seven weeks from Fort Salisbury. Initially Gungunhana stated he was still loyal to Portugal, but upon Dr Jameson stating the arms were from Queen Victoria, he put his mark to a concession confirming Schulz’s oral treaty which was dated 4 October 1890 and placed himself under British protection.

When Dr Jameson’s party reached the Countess of Carnarvon they found the steamer seized by a Portuguese gunboat and themselves under arrest although the treaty was smuggled overland to Lourenco Marques and recovered later.

However the 4 October 1890 date proved a mistake for the BSACo; the Anglo-Portuguese treaty had not lapsed with the ‘modus vivendi’ still in place – so the treaty was considered worthless by the Foreign Office and Dr Jameson was reprimanded for stating that the arms were from Queen Victoria and implying that Gungunhana’s territory would become a British Protectorate.

All these events indicate the lengths that Rhodes was prepared to go to obtain a route to the sea – ultimately the Foreign Office would not recognise either Forbes’ treaties with local chiefs between the Busi and Pungwe rivers, or Jameson’s treaty with Gungunhana.

Victor Morier’s opinion on the potential outcome

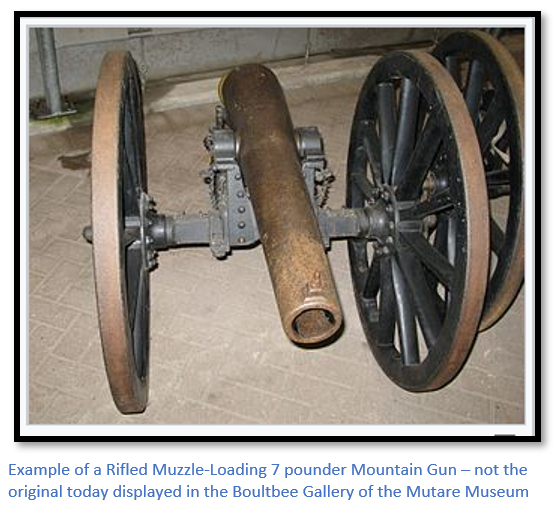

In January the doctor insisted Morier moved from Macequece to Fort Hill at Penhalonga because he kept catching malaria: “I have a spleen as big as my head and am as thin as a pin” and was on special duty: “which consists of my translating the numberless messages which come in from the various Portuguese Governors and officials…The Portuguese are doing all they can to raise the natives against us, and the report is, they are massing their forces at Beira. We might be attacked but I doubt the natives doing much. We have got a seven pounder down here and muster about a 100 all told. Our horses too are in fairly good condition, so we could make a fair show. The great question which agitates us is of course, what will the Home Government do? Will they back us up, or will they make us give back the country. If they do you may expect to see some strange doings.

My prophecy in this case is that the country will be seized by a band consisting of all the discharged Pioneers, the independent prospectors, etc. now in the country and a free Republic will be declared. That this is the intention of the men here is an open secret. Of course it will be absolutely the game of the BSACo to back up such a proceeding in every way. They must have a sea route, and right of way through Manica and if the Portuguese come back they will never get it.”

The next incident to secure the Pungwe route to Mashonaland

The ‘modus vivendi’ granted the BSACo free navigation up the Pungwe river and the use of the land route to Mashonaland – crucially it expired on 14 May 1891. The rainy season in 1890 – 91 had been unusually heavy and prolonged; those in Mashonaland suffered greatly from a lack of foodstuffs and mining supplies as ox-wagons from the south had been unable to cross the Lundi and Nuanetsi (now the Runde and Mwenezi) and Tokwe rivers which had come down in flood. There was now a much greater urgency to use the alternative and shorter Beira route to Mashonaland.

Johnson, Heany and Borrow’s syndicate arranged for five Europeans under the leadership of Sir John Willoughby and ninety-one labourers to be transported to Beira on the Norseman and from there to be transported up the Pungwe river by the paddle-steamers Agnes and the Shark with a string of barges. Their purpose was to survey and make a road into Mashonaland, although the Portuguese authorities were not at any time asked for permission. Willoughby himself had been the BSACo police staff officer and was described by Leonard as: “that fidget on wheels…a mixture of nonchalance, presumption and speculation” and a man most unlikely to have any respect for the Portuguese.

Willoughby’s instructions were to pay customs duty, have an interview with the Governor and inform him that he intended proceeding up the Pungwe river whether permission was given or not: “at daylight on the day succeeding that on which you interviewed the Governor of Beira, you will leave that port and proceed very carefully up the Pungwe…from sunrise to sundown you will, under all circumstances, fly the English ensign.”

The intention was clearly to make the Portuguese honour their commitment to the Pungwe river being an international waterway or to fire on the British flag. Sir Henry Loch, the British High Commissioner at Cape Town sent a telegram stating that if the Portuguese Governor refused permission and failed to observe the ‘modus vivendi’ the ships’ captain was to ask for this refusal in writing and return; if no refusal was received within 24 hours, this would be evidence of consent to proceed.

The Governor-General of Mocambique at Beira, Col. Joaquim José Machado, however refused to allow the party to proceed. Willoughby insisted on their right to do so, although his offer to pay customs duty was refused. On 15 April the paddle-steamer prepared to move upstream, the Portuguese gunboat Tamega fired a blank shot followed by a live round and Willoughby gave up.

The Agnes and Shark were detained with their crews, although the rest of the party were permitted to leave on the Norseman.

What had really incensed the Portuguese was that Fort Massi-Kessi was still occupied by four BSACo police on the grounds that they remained to protect the Companhia de Moçambique’s property until they could take charge of it. Among the items impounded was a bag of mail…Machado had made a diplomatic hash of it and played into Rhodes’ hands. Firing on the British flag was: “an insult and outrage that the Government of Portugal would have to answer for to the Government of England.”

The Portuguese respond with fury

The arrests at Mutasa’s kraal and the continued occupation of Massi-Kessi created popular indignation in Portugal and feelings ran high to avenge the insult against the Portuguese flag. Andrada’s report of their arrest further incensed the Portuguese public.

In late December Major Bettencourt arrived at Fort Hill saying he had been sent by the Governor of Mocambique as the mining commissioner of Manicaland. He was courteously treated by Capt H.M. Heyman but told he could not remain.

Then in early January 1891 a Portuguese officer Ensign Almeida Freire arrived at Massi-Kessi initially stating he was a trader; upon being asked to sign a paper stating he would obey BSACo instructions he disclosed he was actually a soldier and handed Heyman a letter from the Governor of Manica stating the fort should be handed over. Heyman ordered Freire to remain in the fort until he had sufficient carriers to leave the district.

The result of these incidents was that regiment of infantry plus engineers was sent from Portugal followed by a student body of volunteers from Portugal who landed at Delagoa Bay and travelled up the coast; a force of 400 askaris came from Angola and a body of 250 volunteers was formed at Lourenço Marques. The student body landed at Beira in February 1891 and began a march towards Manicaland, but they were ill-equipped and suffered badly from the heat, humidity and malaria taking two months to get from Neves Ferreira later Fontesvilla to Massi-Kessi. The regiment was held up at Neves Ferreira suffering the same debilitating effects from a lack of transport.

In February both Morier and Tyndale-Biscoe on separate occasions visited Chimoio to check out the rumours of the Portuguese advance but found no such evidence; on 7 March however Maurice Heany was taken captive when he visited Chimoio to check the progress of the road making party. Col. Machado declared martial law in Manica and Sofala and closed Beira and the international waterway of the Pungwe river to foreigners.

Morier writes: “On Sunday 3 May, a perfect bombshell bursts in camp [Fort Hill] by the arrival of a special messenger from Rhodes, saying the Portuguese were advancing in a large force on Massa-kesse “sic” calmly adding, ‘You must turn them out.’ All very well, but to tell seventy wretched fever-stricken men (of whom only thirty-eight were fit for duty, owing to the others having no boots) to drive a large well-fitted expedition having its base of operations close by and a perfect commissariat along a good road, out of the country, was a big order.”

The same despatch warned that a large body of Boers were preparing to cross the Limpopo river into Mashonaland. Lt-Col. Pennefather decided he must deal with the Boers, the most serious problem and left for Fort Salisbury, leaving Captain Heyman of “A” Troop to deal with the Portuguese. Pennefather’s instructions were that all available men should go to Massi-Kessi and occupy the hills overlooking the fort and await events.

Lt-Col Pennefather arrived in Manica on 28 April; one of his first acts was to recall the road-making party of Lieut Bruce and reconnoitre the Revue valley when he presumably painted the above watercolour.

14 May 1891, the end of the ‘modus vivendi’

News came the Portuguese under Major Xavier were marching on Massi-Kessi with the Manica Governor J.J. Ferreira with 100 volunteers from Lourenco Marques and a large force of Angolan and local askaris; as they advanced the BSACo police under Heyman fell back on Chua Hill and the Portuguese re-occupied the fort on 5 May.

The same day the seven-pounder gun set left from Fort Hill on the wagon road hauled by ten oxen and with its crew of six men with instructions to get within five kilometres of Massi-Kessi and wait to be joined by the remaining force. The same evening news came that the Portuguese had occupied Massi-Kessi with 70 white men and 600 – 700 Angolan and local African askari’s armed with machine guns. They had hoisted the Portuguese flag and were strengthening the fortifications.

On Wednesday 6 May Captain (later Sir Melville) Heyman’s small force comprised Morier, Drs Farrell and Lichfield, thirty men of “A” Troop plus six men with the seven-pounder gun and ten volunteers which included Fairbridge, Tulloch, Palmer, Crawford, MacLachlan, Russell, Pike, Cripps and Maritz…a total of fifty and these numbers are corroborated by Heyman and Tyndale-Biscoe. Lieut Fiennes was left in charge of Fort Hill whilst the others left for Massi-Kessi, a distance of about thirty kilometres, camping at the Crow’s Nest on top of “the divide.” (see the Fort Hill article under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com) The gun-team had great difficulty in getting the seven-pounder gun over what is now called the Christmas Pass, but also crossed swamps, reeds, scrub and heavy timbered country. This laborious task took three days. However, they arrived at their destination and took up a position on Chua hill overlooking Massi-Kessi Fort.

The Portuguese were aware that Capt. Heyman and his force might advance soon and had decided to take the offensive.

Preliminaries to the battle

Heyman and Morier set off for the fort at Massi-Kessi under a flag of truce and were stopped between the Chua Hills and the fort by a large piquet of Angola troops and met by Major Bettencourt. They were blindfolded and taken into the fort and ushered into the presence of Col Jayme Jose Ferreira, the new fort commandant who had 50 white troops and 300 Angolan askaris in the fort that were being reinforced daily. Heyman asked the Ferreira if he would refrain from troop movements until after the 14 May when the modus vivendi expired. Ferreira replied: “that martial law was proclaimed in Manica and he would drive us out whenever he thought fit.” Heyman told Ferreira he had men at Chua Hills and if the Portuguese troops advanced a fight could not be avoided. Ferreira replied: “that he knew that perfectly,” but if the BSACo forces withdrew to the west side of the Sabi river he would open the road to Beira for them.

Heyman and Morier then left for the Chua Hills where after three days of struggle by Sunday 10 May at 3am they had managed to drag the seven-pounder to the best position on the western end of the Chua Hills and sited in the middle of a freshly-dug trench. Morier says with outlying piquet’s, guard-duty and entrenching fatigues they worked like slaves and at night lay in the trenches in their overcoats, standing to arms for an hour before daybreak. Through binoculars they could see down into the fort at Massi-Kessi, about three kilometre below. The front of their position was protected by a deep ravine, further south was the Revue river valley and to the north steep wooded hills.

Early on the Sunday, following a request to Mutasa by Lieut Fiennes, about 200 of his men turned up and camped three kilometres to the rear of Heyman, but they were sulky and uncooperative and took no part in the impending action; Morier thought that if their small group had been beaten by the Portuguese, Mutasa’s men would have turned on them.

Pennefather rode to Salisbury and informed Colquhoun of the Portuguese activities in Manicaland; “B” Troop were quickly despatched but only arrived on the 21 May – ten days late!

On Sunday afternoon a Portuguese officer came under a flag of truce saying he had come to negotiate, but Heyman suspected they were spying out his forces and gave instructions to most of his men to hide with the seven-pounder gun; the few in sight drifted about nonchalantly. On seeing only a few men about, the Portuguese officer ordered Captain Heyman to leave, or threatened he would be driven out. No sooner had the officer returned to the fort then a large force occupied a kopje about a kilometre away on the eastern end of the Chua Hills and also overlooking Massi-Kessi fort, a hump in the hills between the forces prevented direct observation.

The battle of Chua Hills on 11 May 1891 near Massi-Kessi (Macequece) now present-day Manica

The Portuguese advanced at noon on Monday 11 May 1891 with about sixty European troops and 300 - 400 Angolese troops, in two columns, in their white uniforms. "The effect was picturesque" wrote Tulloch. Heyman’s deception had been so effective with the Portuguese believing his position was so slightly defended that they left behind their machine-guns. They advanced steadily and at six hundred yards deployed into a line and opened fire on Heyman’s piquet’s who returned the fire and then fell back.

As the bullets from the Angolan troops’ Snider rifle began whistling overhead, the seven-pounder gun fired back with shrapnel, a very unpleasant surprise to the attackers, but the BSACo police and the volunteers delayed their attack, waiting for the enemy to get within range of their Martini-Henry rifles.

All the BSACo servants and carriers fled, except for Morier’s servant Marufo, who drove the cattle and horses into a sheltered spot where they were safe from the bullets.

The Portuguese positioned themselves in line abreast at 500 metres and opened fire. Morier wrote: “Their fire was tremendously hot, the repeating rifles of their European troops making us think at one time that they had brought a machine-gun into action. Luckily they fired high and not a single man on our side was touched. Our men were divided into two bodies; one body was acting as sharpshooters in the bush below our trenches, the other body firing from the trenches. During the first half of the engagement I took up my position in a corner of the trench, but not being able to get a good view, I afterwards went down and joined the sharpshooters…I had a narrow squeak, a Snider bullet hitting the trunk of a tree against which I was pressing my cheek taking aim, one of the splinters flying into my eye, which blackened.”

The Martini-Henry rifles used by the BSACo still did not have smokeless powder which obscured their position, although a sergeant and ten men were in front of the trench acting as sharpshooters stayed clear of the smoke. The seven-pounder fired twenty-three shrapnel shells: Tulloch wrote: “pretty good going from a muzzle loader when you think of all the sponging and ramming and priming that had to take place.”

Twice the Portuguese forces reached the edge of the ravine 400 metres from the trench but then retreated despite their offices pleading and shouting with them to carry on.

At one point the view of the seven-pounder gun was obscured by a tree; Tulloch took an axe and after some energetic cutting the tree toppled over and he scrambled back behind cover. The Portuguese did not try and out-flank Heyman’s forces because he sent fictitious signals to imaginary reinforcements in the rear!

After two hours of rapid fire from both sides, the Portuguese askari troops began to retreat in small numbers at first and then in large groups to their fort; the Portuguese officers, who are said to have behaved splendidly, tried to rally their men, beating them with the flats of their swords, but, finding it futile, they all three walked slowly away at little more than funeral pace. Two or three volleys were fired at them, bullets ploughing up the earth around them. It was found afterwards that one, Major Bettencourt, was wounded in the neck rather badly, and another in the arm. They made no sign, however, until just as the rising ground was about to hide them from view, they turned, took off their hats to the English, and strolled slowly back to the fort. The exception was Major Xavier who turned and shook his fist.

There is a story put out by Tulloch that as the Portuguese rear-guard disappeared into the fort, the gunner, named Finch, said to Heyman, "let’s see how the old geezer will behave with the last shell" and screwing the gun up to maximum elevation, let fly and the last shell landed on the roof of the fort and set fire to the thatch. Portuguese casualties are not known and the BSACo force had one slight wound.

[The maximum firing range of the seven pound shell was 2,700 metres (3,000 yards) which gives the distance from Heyman’s position to Fort Massi-Kessi. If anyone can send me a photo of the original in the Mutare Museum I would be grateful]

The next day, Tuesday 12 May, the Portuguese flag was still flying and Heyman unaware that Major Xavier and his force had abandoned the fort, sent Dr Farrell down under a flag of truce to offer his services as a doctor. Farrell found Fort Massi-Kessi without its garrison, but full of Mutasa’s men: their only contribution having been to fire off their muzzle-loaders when the Portuguese retreated, and upon hearing the Portuguese leave in the night, they had decided on a little looting. Farrell signalled to Heyman who promptly occupied the Portuguese position on Chua Hills and sent Morier down to Massi-Kessi with ten men.

Morier saw the fort had been abandoned in a desperate hurry in the dead of night. “All the stores were left and nine machine-guns, seven Hotchkiss and two Nordenfeldts, with thousands of rounds of ammunition. The guns of course had been disabled and having absolutely destroyed the Hotchkiss and dragged the Nordenfeldts up the hill to our position, I blew up the bastions with dynamite and burnt all the buildings.” The fort was rapidly evacuated when ammunition started going off as the barrack roofs were fired, but not before various supplies and foodstuffs had been liberated. Theodore Bent observed six months later that the officer’s mess at the police camp was stocked with Portuguese cutlery and when the Governor of Massi-Kessi visited Fort Hill: “they had nothing to seat him on save his own chairs, nothing to feed him off save on his own plates, and nothing to give him save his tinned meats. But Portuguese politeness rose to the occasion and nothing was said.”

Lack of follow-up

Morier was sent with despatched for Pennefather at Salisbury. A prisoner informed Heyman that at Chimoio there was just a sergeant with three men, a doctor and ambulance and at Sarmento just a sergeant and five men, but Heyman’s gallant band of half-starved policemen and volunteers were not capable of following up the attack, as Fairbridge remarked: "in their state of complete exhaustion they could not have pursued anything swifter than a tortoise!” They only had six horses, almost all the local carriers had run away and the troopers lacked basic equipment, such as boots.

Pennefather ordered Heyman to return to Fort Hill with his men, Lieutenant Fiennes was ordered to take two wagons and a scotch cart to Massi-Kessi and remove supplies and foodstuffs after which a civilian, Maritz, was left in charge. The Companhia de Moçambique made a claim for £10,000 for damage and loss of their stores but the claim was not recognised.

On 14 May Pennefather and Selous arrived at Massi-Kessi shortly after the arrival of Col. Ferreira’s secretary under a flag of truce. He left soon after inspecting the damaged fort.

Immediate consequences of the battle

The ‘modus vivendi’ expired on 14 May 1891. Although the Portuguese had been the aggressors, Heyman and the BSACo police and volunteers and their seven-pounder gun had no right to be in the vicinity of Massi-Kessi. If Major Xavier had won the battle his mistake to attack would have been overlooked, but because he lost, Heyman now considered the way to Beira to be open.

Next day Pennefather and Selous and two troopers rode out to establish how far the Portuguese had retreated. They were informed the askaris had headed for Gouveia at Gorongoza, the remainder were at Chimoio making their way to Beira.

From the 15 May “B” Troop and all the civilians present began to work on strengthening the fortifications at Fort Hill. The seven-pounder gun and the two captured Portuguese Nordenfeldt guns (without their breechblocks!) were mounted on the walls facing east down the Penhalonga valley. [See the article Fort Hill – the first site of Umtali (now Mutare) under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

On 21 May Pennefather and Heyman rode over to Bingaguru to ensure they had Mutasa’s loyalty; thereafter Pennefather left for Salisbury.

Rhodes encourages the push for the sea

News of the battle of Chua Hills reached the Captain of the Agnes on the Pungwe river when he shipped Portuguese officers back to Beira; he sent a telegram to Cape Town who transmitted the information to London.

J.C. Barnes quotes a BSACo telegram from London to Cape Town dated 29 May 1891: “Referring to telegram from High Commissioner [Loch] to Colonial Office [Salisbury] 29th May with overland news of engagement…you will observe that Portuguese employed black men and attacked Police Force after we had gone from Massi Kessi in the belief that the Police were weak and starving. After such gross breach of Agreement [the modus vivendi] you must press for occupation of Beira and cession strip of territory as far as Mashonaland, as you know Portuguese officials in SA will not obey Lisbon, any treaty will be nominal, no railway, if it is agreed to, will ever be built by them. You cannot develop Mashonaland with 1,600 miles of land route. It is now the best time for action, now is your chance.” Barnes detects the influence and authority of Rhodes in the message.

On 24 May Heyman heard from travellers arriving at Fort Hill that the Portuguese forces had left Chimoio in full retreat carrying their wounded and with many of them sick with fever.

Fiennes plans an attack on Chimoio

On 26 May Lieut. Fiennes and eighteen troopers left on horseback for Chimoio which they reached the next evening and carried out a reconnaissance of the Chimoio fort preparatory to mounting an attack.

Prior to this, on 12 May Sir Henry Locke’s military secretary Major Sapte had arrived at Beira just after the first Bishop of Mashonaland, Bishop George Knight-Bruce. They two met up at Neves Ferreira above the Pungwe river where they both learned of the recent battle at Chua Hills. The Portuguese commandant permitted Sapte to leave, but only permitted the Bishop to leave the next day with a Portuguese artillery officer on a similar political mission as Sapte. After two days Knight-Bruce left the Portuguese officer behind and by the fourth day had overtaken Sapte.

On the morning of 29 May Knight-Bruce had breakfast with the Chimoio fort commandant and then left before being intercepted outside Chimoio on the track by Fiennes and two troopers.

Sapte was similarly well entertained by the fort commandant and whilst with him a soldier brought in a message from the Bishop to say that he was with Lieut. Fiennes.

Sapte left Chimoio at 6am on 30 May and met Fiennes and three troopers outside Chimoio. Sapte confirmed the ongoing peace negotiations between the Foreign Office and Portugal; Fiennes then had a cordial meeting with the camp commandant before returning to Fort Hill.

On Fiennes’ return to Fort Hill and hearing the information on the political negotiations transmitted by Sapte, Heyman issued an instruction that no prospecting should take place east of “the divide” as he wanted to establish peaceful conditions so that unimpeded travel to Beira could resume. Massi-Kessi was re-occupied by the Companhia de Moçambique.

Rhodes never forgave the Bishop Knight-Bruce for interfering or Fiennes for listening to him and was reported to have later said: “but why didn’t you put Sapte in irons and say he was drunk?” So the pursuit of the Portuguese ended and with it any hopes that the British Empire would be extended to the coast.

Gungunyana sends envoys to Britain

Neil Parsons in an essay on the various Zulu, Ndebele, Gaza and Swazi envoys to England in the period 1882 to 1894 notes that King Gungunyana sent envoys to England in 1891 and stated he preferred the British over the Portuguese who: “made the men and the women and the children silly with drink.”

The two Indunas Huluhulu Umteto and Umfeti Ntini arrived in Plymouth on 23 May 1891 accompanied by Dennis Doyle, a BSACo employee and were the subject of a well-organised publicity campaign by the same company which included newspaper interviews with the Pall Mall Gazette which supported Rhodes’ imperial aims. The aim was to gather support for a British intervention in Gazaland, the southern central portion of Mocambique.

Lord Salisbury was furious, but Rhodes maintained it was merely a private visit. Their visit coincided with the events described above, rumours of which were just beginning to reach England.

All of Rhodes’ expectations of gaining the territory of Gazaland were sunk by the new Anglo-Portuguese treaty of 11 June 1891 which replaced the treaty of August 1890 and unambiguously defined the boundary between Mocambique and British territory as running north – south along the Nyanga mountains “the divide” locating Gazaland firmly in Portuguese territory.

[For more information on the African envoys see the article Why Lobengula sent envoys to Queen Victoria in the late nineteenth century under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Anglo-Portuguese treaty of 11 June 1891 and longer term consequences for the region

Following Lord Salisbury’s ultimatum on 11 January 1890 which demanded the withdrawal of Portuguese troops from Mashonaland and the Shire Highlands in Malawi, there were anti-British riots and demonstrations in Portugal. Subsequently talks began in April 1890 but the proposals in the agreement signed on 1890 were never approved by the Portuguese Parliament and we know that Rhodes was also opposed this agreement.

The subsequent clashes between the BSACo and Portuguese forces and the Companhia de Moçambique as described above put the Portuguese authorities in a weak negotiating position. A new treaty was negotiated and signed in Lisbon on 11 June 1891 which gave the Portuguese more territory in the Zambesi valley, but established the boundary between latitudes 32°30´and 33° East of Greenwich, thus ensuring that Manicaland passed from Portuguese into British control and freedom of navigation was established on the Zambesi, Shire and Pungwe rivers. [These terms are described in the article “The Pink Map; how credible were Portuguese claims to Mashonaland” under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Clearly Rhodes’ many attempts to secure an outlet to the sea had been frustrated by the Foreign Office, but the BSACo’s right to use the Beira route to Mashonaland was recognised. Three British warships arrived off Beira to ensure that all foreign ships had the right to free passage up the Pungwe as long as any customs duty was paid and travellers had the right to carry arms. Sir John Willoughby and his labourers reappeared to construct a road from Fontesvilla and were not obstructed by the Portuguese authorities.

Later the Anglo-Portuguese Boundary Commission fixed the present-day borders of Mozambique and Zimbabwe. Victor Morier whose letters are much quoted above suffered greatly from malaria and returned to Britain on leave preparatory to taking up the post of Assistant Commissioner of the Boundary Commission but died at sea on 27 May 1892 on the return voyage, probably of cerebral malaria.

Behind the scenes commercial manoeuvres continue

In 1891 the Companhia de Moçambique continued to grant mining concessions, many to British syndicates and they sometimes overlapped with BSACo mining claims – the international boundary still being undecided. Negotiations began in November 1890 between Bartissol and the BSACo directors regarding mining rights which overlapped the international boundary.

Edmond Bartissol was negotiating for a royal charter from the Portuguese government for an enlarged Companhia de Moçambique and believed the BSACo could make an indirect investment through a French subsidiary company. The Portuguese Government however expressly forbade the BSACo holding a majority of shares in the charter; weeks later the BSACo was forbidden to hold any shares at all. This was a disappointment for the Foreign Office which had hoped there would be a commercial resolution which would simplify things.

Postscript on Bingaguru, Chief Mutasa’s stronghold visited in 1972

When JC Barnes, Iain Gwyther, Robert Plowes and Newton from the Ministry of Internal Affairs visited Bingaguru they used the same path to the mountain as used by all previous visitors and passed through two lines of stone walls in poor repair…the outer defence walls. The path twisted and turned around stone platforms from which they supposed rocks and spears could be thrown at an attacking force. 152 metres higher up the mountain at 1,680 metres (5,000 feet) the path was lost in dense undergrowth and they saw the upper-end of a tunnel surmounted by a broken stone wall which earlier visitors had been forced to crawl through.

There were magnificent views from the top of Bingaguru in all directions – the numerous granite outcrops and dense undergrowth meant it was not possible to view the layout of the old kraal. Barnes quotes Blennerhassett and Sleeman, two of the three first nurses to Fort Hill, who in 1892 delivered the £100 promised in Colquhoun’s treaty, as saying that even then the huts were hidden so well amongst the boulders that it was difficult to spot them.

At what would be the southern end of the kraal was the remains of a lookout hut; Chief Tendai Mutasa’s hut would have been more centrally situated. Here visitors and the nurses would be made to sit for hours waiting for Chief Mutasa to make an appearance. At the northern end of the summit a slight depression in the rocks provided a reservoir for rainwater.

Rob Plowes says that in 1972 when they received permission from Chief Mutasa to climb Bingaguru many of the dhaka hut bases were still intact – some even had their wall poles still standing and the mountain stronghold seemed to have been abandoned in a hurry.

They left Bingaguru on the only other access route passing a small and level platform that was the site of Chimbadzwa’s kraal which guarded the northern approaches. The route down allowed for single file only with a sheer drop of 180 metres (600 feet) on one side and where the path meets the saddle between Bingaguru and Nyamasakitwa mountains the old Chief’s cemetery could be seen.

Rob Plowes, son of the much-missed Darrel Plowes, tells me that before the climb the party went and paid their respects and obtained permission from Chief Mutasa at his home.

Newton, their guide for the trip to Bingaguru, was Darrel’s assistant for many years and Rob says he was fortunate to spend a lot of time with him when Darrel was on field trips. Newton was part of the Maskotcha (= Scottish!) group of former African serviceman who still paraded in kilts and other wartime regalia on Remembrance Day, the 11 November each year when a two-minute silence is held to remember the people who have died in wars.

Acknowledgements

J.C. Barnes. Bingaguru. Zuro – the Magazine of the History Society, Umtali Boys’ High School, 1973 P21-25

J.C. Barnes. The attack on Mutasa’s kraal, Nov 15th, 1890. Zuro – the Magazine of the History Society, Umtali Boys’ High School, 1974 P53-58

J.C. Barnes. The Battle of Massi Kessi. Rhodesiana Publication No 32, March 1975

Barry Brown for reading the draft and making suggestions

J.A. Edwards. Colquhoun in Mashonaland; A Portrait of Failure. Rhodesiana Publication No 9, December 1963

C.M. Hulley. Memories of Manicaland. C.M. Hulley 1980

F. Johnson. Great Days. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1972

A. Keppel-Jones. Rhodes and Rhodesia; the White Conquest of Zimbabwe 1884-1902. McGill-Queen’s University Press 1983

A.G. Leonard. How we made Rhodesia. Books of Rhodesia. Bulawayo 1973

N. Parsons. No longer rare birds in London. 'Black Victorians/Black Victoriana' edited by Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina. Rutgers, The State University, 2003

Rob Plowes for letting me have scans of Zuro – the Magazine of the History Society, Umtali Boys’ High School and for the photograph of Bingaguru.

F.C. Selous. Travel and Adventure in S.E. Africa. Books of Rhodesia. Bulawayo 1972

P.R. Warhurst. Extracts from the South African Letters and Diaries of Victor Morier, 1890-91 Rhodesiana Publication No 13, 1965

Barry Brown

Wikipedia for photographs and text