Fort Haynes and the fight at Chief Chingaira Makoni’s Kraal

The battle at Chief Chingaira Makoni’s kraal and stronghold was one of the few set-pieces in the 1896 Mashona rebellion, or First Chimurenga where the Mashona forces had the option of setting the location and where Col. Alderson’s forces set the time of the engagement.

The few set-piece battles probably include this at Chief Makoni’s kraal, that at Fort Harding and Chief Chikwakwa / Headman Gondo’s kraals near Goromonzi and at Chief Mashingombi’s / Headman Chena’s kraals near Hartley Hill.

For the rest the actions are mostly skirmishes in Mashonaland.

Col. Alderson was criticised by Earl Grey for not establishing more forts and breaking off the engagements early; but as he reminds us often in his book, he was uncertain of the supply situation in Salisbury with the telegraph line being constantly cut.

There is still controversy around Chief Chingaira Makoni’s death by firing squad. Feelings were running high as 117 settlers had been killed in Mashonaland out of a population of 2,737. The military discipline instilled by professional soldiers such as Col. Alderson, calmed the situation down.

Visit the marble memorial to Capt. A.E. Haynes Royal Engineers surrounded in a metal railing. A few metres to the east within a low stone wall are the metal grave marker to Pte Smith Vickers 3rd Battalion Kings Royal Rifles and the marble memorial to Pvt William Wickham 1st Battalion Royal Irish Regiment.

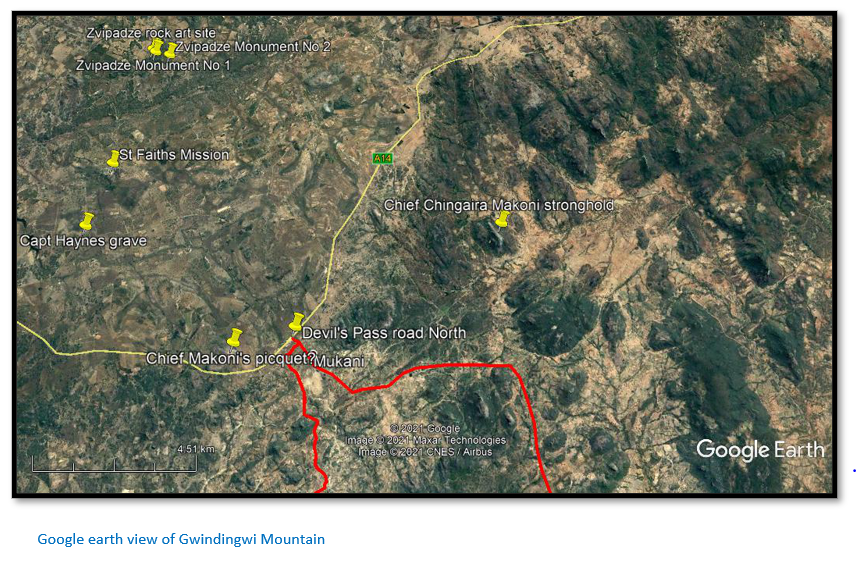

From Rusape take the A14 turnoff to Nyanga: Drive 7.5 KM and turn left onto the gravel road with a signpost for St Faith’s mission. 10.4 KM pass the turnoff on the right for the farm owner, Mr Vitalis, whose property is adjacent to the farm that Fort Haynes is probably situated on. 10.6 KM cross the Nyamasvitsvi River, 11.9 KM stop just short of the cattle grid and before the road turns left for St Faith’s Mission. Park the car and follow a path for 220 metres through some gum trees on the left. Cross over a fence which is lying on the ground and bear right along a firebreak accessing Captain Haynes’ grave which is 15 metres from the firebreak in a group of trees just west of the fence line dividing the farms.

Fort Haynes is described by Col. Alderson as being 350 metres away along the Nyamasvitsvi River. In fact, the nearest point for the Nyamasvitsvi River is 800 metres away. However, 350 metres due south, in the same direction as the river, is a small homestead and this may be the site of Fort Haynes, although I have not yet investigated.

A rounded granite gomo with telephone towers on the summit might be the site on Col. Alderson’s map which has Chief Chingaira Makoni’s picket marked.

Chief Chingaira Makoni’s kraal and stronghold was at Gwindingwi Mountain amongst the kopjes on the right-side of the A14 going towards Nyanga. A gravel road leaves the A14 at 24.7 kms from Rusape and heads south east towards the mountain. After travelling 4.4 kms the road forks; one branch going east and the other west of the mountain.

GPS reference for Captain Haynes grave: 18⁰30′31.54″S 32⁰12′59.09″E

GPS reference for Gwindingwi Mountain: 18⁰30′32.19″S 32⁰20′12.41″E

In June 1896 the Mashona Rebellion or First Chimurenga broke out.

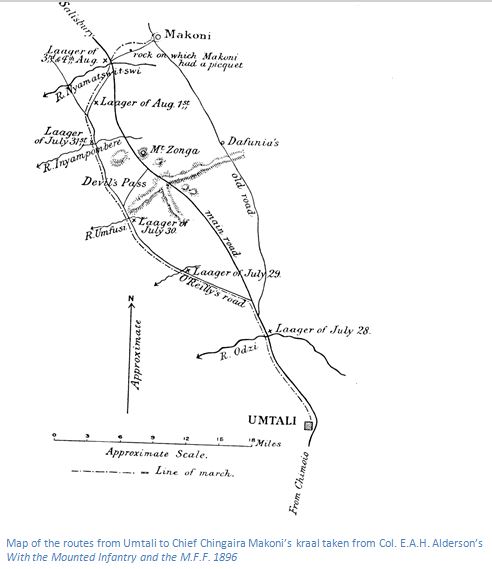

Four companies of mounted infantry were sent from Aldershot in England destined for Matabeland arrived in Cape Town on 19th May 1896. Their destination was now switched to Mashonaland and they set off by sea to Beira. From there they took the train 170 miles to Chimoio and then travelled by wagon and horseback with the first of the troops reaching Umtali (now Mutare) on 19th July 1896.

This force of 380 mounted Infantry was under the command of Col. E.A. Alderson and their five month campaign is told in his book With the Mounted Infantry and the Mashonaland Field Force 1896.

Chief Chingaira Makoni posed a major threat to the communications between Mutare and Harare with his kraal and stronghold some seventeen kilometres northeast of present-day Rusape. The telegraph line had already been cut and there was no communication between Mutare and Harare for 48 days.

On the 28th July 1896, the Mashonaland Field Force comprising 230 mounted infantry, 39 Royal Engineers, 14 Royal Artillery, 48 West Riding Regiment, 17 Scouts and 92 volunteers (Total of 440) with two Maxim guns and two seven-pounders left Mutare.

They avoided the Devil’s Pass, where they anticipated an ambush, by using the O’Reilly’s Road and on the 2nd / 3rd and 4th August laagered on the Nyamasvitsvi River where it was crossed by the main road and close to the four, or five huts locally known as the “new police huts.”

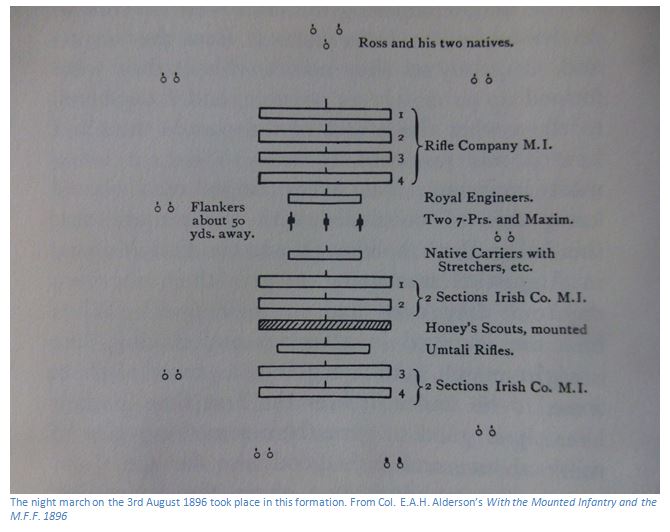

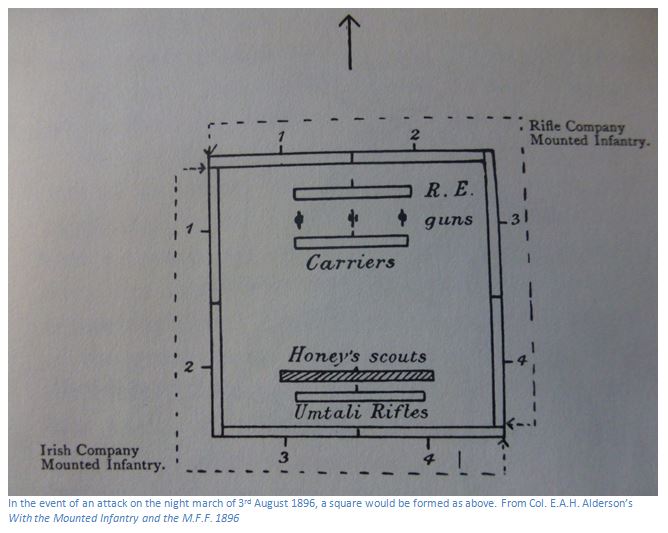

In the afternoon of the 2nd Col. Alderson had a meeting with Chief Native Commissioner Taberer and Native Commissioner Ross and decided upon a night attack on Chief Chingaira Makoni. The imminent attack was kept secret and at 1.45am on the 3rd August, Alderson’s forces fell in as silently as possible before Col. Alderson addressed them all and told them the object of their preparations was an attack on Chief Chingaira Makoni’s stronghold and they began their night march.

They marched in the formation below in case they were ambushed and detoured away from the main track to avoid one of Chief Chingaira Makoni’s military posts (the picquet marked on the map above) which had been placed on a prominent rock near where the track ran to his kraal.

They had brought one Maxim gun and the two seven-pounders, but they were each being pulled by two instead of four mules, and it slowed the force’s movement down. At 5:15am Native Commissioner Ross, who was acting as guide, thought he had miscalculated the distance and they might not be there by daylight.

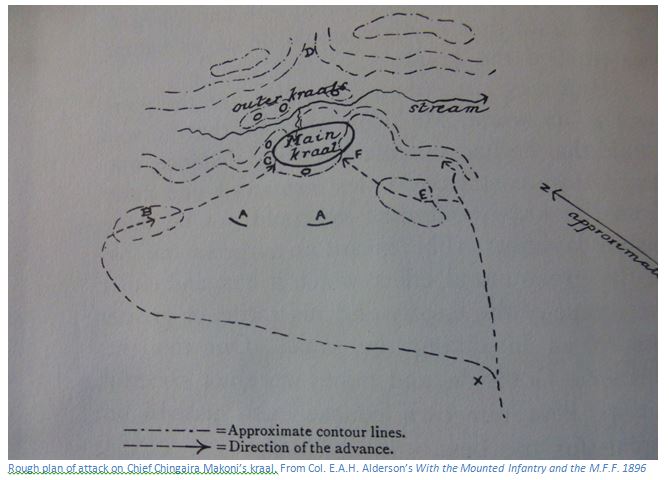

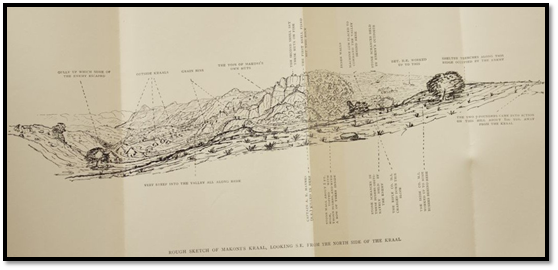

A few minutes later, Ross said it was alright and they were at point X on the plan. Capt. Jenner was sent with the Rifle Company Mounted Infantry, the Umtali Rifles and the Maxim gun to the south of Chief Chingaira Makoni’s kraal at E and Col. Alderson took the Irish Company Mounted Infantry, the engineers and the two seven-pounders to the west at B and Jenner was told not to commence firing until the seven-pounders opened fire.

A celebration had been taking place and the sentries on duty to the south east of the kraal at A did not hear the forces moving around them. Col. Alderson’s force at 5:50am was 750 metres from Chief Chingaira Makoni’s kraal and looking down on it. They saw it occupied a strong defensive position surrounded by a dry-stone wall topped with thorn bushes and containing around 300 pole and dhaka thatched huts. The seven-pounders opened fire with direct hits on their intended targets and in a moment the kraal was in Col. Alderson’s words “like a stirred up ant’s nest.”

Alderson’s forces moved forward in the face of return fire and Private Mackey was wounded with the seven-pounder shields being hit repeatedly by rounds. Capt. Jenner’s Maxim gun opened up on the south side. By 7:30 Alderson’s troops have only 180 metres of open ground between them and the wall around Chief Chingaira Makoni’s kraal. Jenner’s men charge with fixed bayonets and when they were 180 metres from point F; Alderson had his men charge to point C so that the combined forces reached the wall around the kraal simultaneously.

Chief Chingaira Makoni’s defenders retreated to the caves and shots from there killed Capt. Haynes and Private Vickers who were clearing the inner walls about 8:30am. Alderson was now faced with choices:

(1) Send men into the caves where they would be at a disadvantage? No, too dangerous.

(2) Blockade the caves and starve the Mashona out? There had been no news from Salisbury and Alderson believed he should ascertain the situation there as quickly as possible.

(3) Dynamite the caves? No, they were too extensive.

So by 2pm the same day, Alderson’s forces evacuated the kraal having set it on fire and marched back to the Fort on the Nyamasvitsvi River with over 500 captured cattle, sheep and goats. Alderson considered Chief Chingaira Makoni’s casualties amounted to about 200 men.

Alderson’s casualties included Capt. Alfred Ernst Haynes, Royal Engineers; Private Smith Vickers, Kings Royal Rifles; Private Williams Wickham, Royal Irish Regiment; killed and four wounded. Those killed were taken back and buried on the 4th August near the Nyamasvitsvi River “in a well-chosen site under two spreading trees, about a quarter of a mile from Fort Haynes.” The grove of trees was still standing in May 2016 when visited by the author.

Col. Alderson says: “Poor little Haynes was, as I have already said, killed inside the kraal, after having gallantly led his men over the wall. In him we had suffered an irreparable loss. With his bright keenness, his fertile brain, and ready resource, he had already made himself invaluable. Apart from his professional value to me, I never met a man whom I grew to like so much in so short a time. Both the privates killed were good useful men, whose loss we could ill afford.”

Captain Haynes marble memorial is surrounded by a still intact metal railing. The epitaph reads: IN MEMORIAM. CAPTAIN ALFRED ERNEST HAYNES, ROYAL ENGINEERS. BORN JULY 27 AT HAMPSTEAD LONDON. KILLED IN ACTION NEAR THIS PLACE AUG 3 1896. “FAITHFUL UNTO DEATH”

The east side of Captain Haines memorial has the following epitaph: ALSO PT VICKERS, 3rd BATT, KINGS ROYAL RIFLES. The west side epitaph reads: ALSO PT W. WICKHAM, 1st BATT, ROYAL IRISH REGT.

The two privates are buried within in a low walled enclosure a few metres east of Captain Haynes grave which is obscured by a heavy growth and which I failed to spot on the first visit.

The epitaph on Pte Smith Vickers metal grave marker reads: FOR QUEEN & EMPIRE. SMITH VICKERS KRR 3.9.96. The date inserted by the Gregory Iron Foundry in Cape Town is incorrect and should read 3.8.96.

The epitaph on Pte William Wickham marble memorial reads: IN MEMORIAM. PTE WILLIAM WICKHAM 1st BATTn ROYAL IRISH REGIMENT, SERVING WITH THE MOUNTED INFANTRY, KILLED IN ATION AT MAKONI’S KRAAL, AUGUST 3rd 1896. ERECTED BY THE OFFICERS, NON-COMMISSIONED OFFICERS AND MEN OF THE IRISH COMPANY, MOUNTED INFANTRY

Pte Smith Vickers iron grave marker resulted from the lists drawn up by the Guild of Loyal Women (GLW) in 1908-9 which were drawn up in turn from lists drawn up by the BSAP and was presumably supplied with the incorrect date to the Gregory iron foundry in Cape Town where it was cast.

The marble memorial for Pte William Wickham was presumably the result of a collection made by the men of the Irish Company of the Mounted Infantry; this was not done for Pte Smith Vickers.

Surname | Initials / Name | Number | Rank | Unit | Command | Status | Date of Death |

Haynes | Aubrey Edward | 5231 | Capt | Royal Engineers | Mashonaland Field Force | KIA | 3 August 1896 |

Vickers | Smith | n/a | Pte | 3rd Bn King's Royal Rifle Corps | Mashonaland Field Force | KIA | 3 August 1896 |

Wickham | William | 8075 | Pte | 1st Bn Royal Irish Regiment | Mashonaland Field Force | KIA | 3 August 1896 |

Interestingly there is no mention of who paid for and commissioned Capt. Haynes’ memorial; I believe the BSA Company paid for the metal fence enclosure.

Col. Alderson writes: “We arrived back at the laager just before dusk, and found that the men left there had made good progress with the building of the fort which was to be established there, and which poor Haynes had designed the previous day. The fort was naturally christened Fort Haynes.”

The fort designed by Capt. Haynes was built near the Nyamasvitsvi River and became the main depot for road garrisons with the existing police huts were converted into a hospital for the sick and wounded. No plan seems to exist of the Fort and there are no drawings in Peter Garlake’s comprehensive article on Pioneer Forts in Rhodesia 1890 – 1897.

The severely wounded included:

Surname | Initials / Name | Number | Rank | Unit | Command |

Mackey | W | 4231 | Pte | Royal Irish Regt. | Mashonaland Field Force |

Broad | R | 7825 | Pte | 2nd Bn Rifle Brigade | Mashonaland Field Force |

Young | D | n/a | TPr | Umtali Rifles | Mashonaland Field Force |

Slightly wounded included: | |||||||||

Surname | Initials / Name | Number | Rank | Unit | Command |

| |||

Lock | H | 7256 | Pte | 3rd Bn King's Royal Rifles | Mashonaland Field Force |

| |||

Col. Alderson and his mounted infantry left soon after for Harare and Chief Chingaira Makoni reoccupied his stronghold claiming that the victory was his.

A chain of fortified posts was established at Devil’s Pass, Headlands and the Marandellas Hotel (now Marondera) both of the last two named being south of their present locations. These were garrisoned by local volunteers and the Mashonaland Field Force under Major C.W. Watts.

No. of men | Unit | Post | Kilometres from Salisbury |

|

| Salisbury | 0 |

70 | Matabeleland Relief Force | Marandellas No V Fort | 83 |

30 | Umtali Rifles | Headlands No IV Fort | 142 |

50 | Det. 2 / West Riding Regt. | Fort Haynes No III Fort | 176 |

50 | Det. 2 / West Riding Regt. | Devil's Pass No II Fort | 197 |

50 | Det. 2 / West Riding Regt. |

|

|

70 | Umtali Rifles | Umtali No I Fort | 248 |

30 | Matabeleland Relief Force |

|

|

350 |

|

|

|

The Second attack on Gwindingwi Mountain and capture of Chief Makoni

Major C.N. Watts of the 2nd West Riding Regiment arrived at Old Marandellas from Bulawayo on 29 July 1896 with a detachment of one hundred soldiers from the Matabeleland Relief Force. At Charter he had handed over to Col. R. Beal the thirteen wagon loads of supplies for Salisbury he had brought with him.

He was then ordered to go from Old Umtali to Fort Haynes to accept the rifles and ammunition surrendered, or to attack Chief Makoni’s kraal again if he failed to surrender, and by the 26 August there were 230 men at Fort Haynes made up of detachments from the Umtali Artillery Corps, the Umtali Volunteers and the Imperial Forces with the seven-pound gun from Old Umtali. The chief and about two hundred of his men were still emerging from the caves in their stronghold at Gwindingwi Mountain to threaten travellers and transport at the top of the Devil’s Pass road.

Prior to this there had been much local criticism of Lt-Colonel E.A.H. Alderson’s tactics which were judged by locals as being altogether too soft. R. Hodder-Williams quotes Adams-Acton saying Alderson’s Mounted Infantry did “no end of harm” because the Mashona were not driven from their strongholds and “now thought they could defy the white man.”[i]

Even Earl Grey, the Administrator in a letter to his wife wrote on 10 January 1897 that Alderson had made a major mistake in not utterly crushing Chief Chinengundu Mashayamombe’s force at his stronghold on the Mupfure river. In another letter on the 17 January, he wrote: “there is no doubt, privately, that the Imperial troops did very little and the punishment of the Mashonas has not been sufficient.”

However, the difference rose over tactics. Alderson thought that the stubborn chiefs would negotiate and come to terms; when he was unable to persuade a chief to come to terms, he passed on with his quest to resupply Salisbury. His theory being that once he reached Salisbury, he could view the scene in Mashonaland as a whole, realise negotiations were not working and deal with the chiefs in a more direct and less peaceful way.

As Hodder-Williams states, local volunteer forces realised this was not an uprising where compromise solutions could be negotiated, because what was at stake was the white man’s presence in the country.

Chief Chingaira Makoni sent Watts a message on the 27 August 1896 saying he would surrender the next day; but failed to appear and on the 30 August Major Watts marched from Fort Haynes at 1:30am taking the same route as was taken by the forces on the 3 August. Every precaution was taken to keep their leaving secret and ensure the attack was a surprise, although this seems unlikely in view of Makoni’s men knowing the country far better; indeed, only a few men were at the kraal and they quickly retreated to the caves.

Chief Chingaira Makoni’s kraal was occupied at daybreak without opposition and the seven pounder was deployed opposite the mouth of the main cave and opened fire. Chief Makoni’s men replied with a well-directed, but desultory fire from their positions within the caves and the stalemate continued for a few days with Chief Makoni refusing to surrender.[ii] On the first attack eleven of Chief Makoni’s men and seventy women and children were captured.[iii]

Several attempts were made by Makoni’s people to break through the lines of the siege, but they were driven back into the caves.

Once a supply of dynamite had arrived from Salisbury by wagon, a meeting was held to consider the best way to dislodge Chief Makoni’s people from their caves. Lieutenant Fichat and Andrew Puzey of the Umtali Volunteers with Colin Harding volunteered to run the greatest risk of placing the dynamite charges within the caves whilst under constant and heavy fire.

Lionel Cripps added: “Andrew Puzey had prepared the fuse and was let down into the cave by rope and after setting fire to the fuse was hauled up – a ticklish job and not much to his liking, so he told me.”[iv]

Prisoners later stated that the first dynamite explosion sheared off large chunks of granite from the roof of the cave burying grain bins and killing two warriors, whilst several others were hurt by splinters of shattered rock.

Watts gained intelligence that Chief Makoni intended escaping from the caves and breaking through his picket lines on the night of Tuesday, 2 September 1896. The forces surrounding the cave entrances and nearby kraal were reinforced for such an eventuality. Soon after sunset a Mashona force made a rush from the caves and a heavy fire was opened up on them. Chief Makoni tried to use the fighting as a diversion to escape from the cave; Elsa Goodwin Green was told by local sources that Lieutenant Fichat went into the caves regardless of the deadly fire and dragged out the chief into the cover of the kraal.

Again, Lionel Cripps adds in his notes that Elsa implied that Lieutenant Fichat captured the chief unaided, but the reality was: “Tom Dlamini, a Swazi, actually did the catching of Makoni. He invited him to palaver and then grabbed him by the arm and handed him over to Fichat.”[v]

Once his followers saw that Chief Makoni had been captured many lost heart for further fighting and came out and gave themselves up.

Major Watts wished to send Chief Makoni to Umtali to stand trial, but Native Commissioner Ross was opposed to this plan as he argued there was a real risk of the Chief escaping which would set the whole district into a blaze, and that the safety of Old Umtali itself might be endangered. In fact, one of Chief Chingaira Makoni’s sons and two of his senior advisers did manage to escape and Watts’s plan for a trial in Umtali was rapidly discarded and a court-martial was quickly convened to try Chief Makoni for armed rebellion with one of the native commissioners being appointed to act as interpreter and as his defender.

The following day, Wednesday 3 September 1896 he was tried by a Field General Court-Martial composed of the following officers:

Captain Pease, King’s Own Lancers, President

Captain Watts, 2nd West Riding Regiment

Captain Tulloch, Umtali Volunteers

Lieutenant Stockley, Matabeleland Mounted Police[vi]

Lieutenant McQueen, Matabeleland Mounted Police

In spite of Chief Chingaira Makoni’s assertion that he was innocent of being a rebel; his reply being: “it is all very well to call me a rebel, but the country belonged to me and my forefathers long before you came here” he was found guilty of armed rebellion and of having caused the murder of the three traders at Headlands by the officers of the court-martial and was sentenced to be shot. A telegram was sent to Earl Grey by Major Watts to confirm the sentence, but as the nearest telegraph office was at Umtali, this had to be taken by native runners. Native Commissioner Ross argued that any delay in waiting until permission was received would be prejudicial to security and the sentence was carried out on the morning of the 4 September.

Chief Chingaira Makoni was executed by firing squad in the presence of all who had taken part in the fighting, including tribesmen who had resisted Watt’s force and been taken prisoner. The firing party was drawn up of troopers from each squad that took part.

… [after capture] it was feared that if Makoni should escape … the whole district would be in a blaze, and that the safety of Umtali itself might be endangered. A court-martial was therefore convened to try him, In spite of his assertion that he was innocent, he was found guilty of being a rebel, and of having caused the murder of the three traders; he was therefore sentenced to be shot, and the sentence was carried out at once. He was placed with his back to a corn-bin, on the edge of the precipice on which his kraal stood and died with a courage and dignity that extorted an unwilling admiration from all who were present. One of the best known men in Salisbury, when talking to me about it, said, “I know of nothing grander than Makoni’s death, than the quiet way in which he spoke to his people, and told them to abstain from further resistance; for himself he only begged that he might be buried decently. ‘And now,’ he said, ‘you shall see how a Makoni can die.'”

Elsa Goodwin Green states she was told that his body was buried where he fell overlooking his kraal, but it is apparent from oral history that he was reburied by his followers in the traditional burial place of Makoni Chieftains.

Casualties on Major Watts side were light: Sergeant-Major Wood of the Umtali Volunteers was slightly wounded as were two of the native forces. The casualties on Makoni’s side were believed to be about thirty killed and others wounded, some by firing and others in the dynamite explosion.

Elsa Goodwin green says the capture and execution of Chief Makoni had an immediate effect in the district “as all armed resistance halted much to the relief of the citizens of Manicaland.”[vii]

This action caused controversy even at the time in 1896 when passions were running high. Colonel Alderson sent a telegram congratulating Major Watts and his force on their success, however the High Commissioner at Cape Town, Sir Hercules Robinson, called the court-martial into question, and pending an inquiry, Major Watts was suspended and brought to Salisbury under arrest on 18th September, where he was to appear before a court of inquiry on charges of cruelty.

The residents of Old Umtali made up a petition in protest at this action and a telegram was sent to Earl Grey, the Second Administrator of Rhodesia.[viii] The telegram stated that Major Watts’ action in convening a court-martial was not only justifiable, but absolutely necessary. Many killings in the district of traders and farmers had been committed at Chief Makoni’s orders, his defiance had rallied other chiefs to rebel against the administration and his death had brought immediate peace to the district.

At the inquiry Major Watts justified his actions by stating that Chief Makoni was one of the most powerful chiefs in Mashonaland and posed a threat not only to the white community, but also to Mashona tribes, friendly to whites, whom he often raided.

He was acquitted on the grounds that the rebellion justified actions that would not be permitted in peacetime. One of the Umtali Volunteers wrote: “our CO Major Watts is a perfect devil” but the popular sentiment amongst the whites was probably expressed in a letter by George McDougal who fought with the Umtali Volunteers in the Marandellas area (now Marondera) and wrote to his family in Scotland that: “the enemy are always ready to pounce upon small parties unarmed and torture them to death. It is such dastardly conduct on their part that makes the white man so bitter against them here.”

The Melbourne Argus of 1 October 1896 carried a short article: “The shooting of Makoni: Major Watts acquitted. The inquiry into the conduct of Major Watts in having the Matabele (sic) chief tried by court-martial and shot has resulted in the acquittal of that officer.”

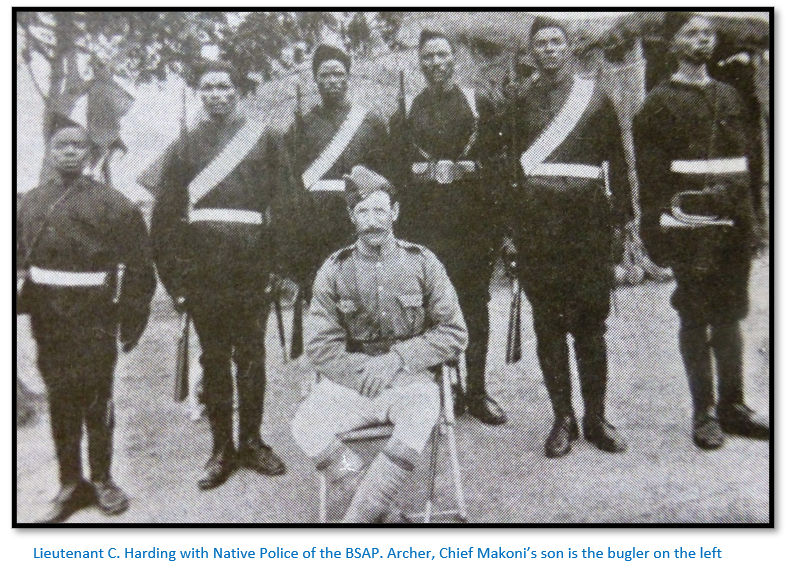

Colin Harding, in his book Frontier Patrols writes: “the use of dynamite at this and other times, though distasteful, was, I think, justifiable and necessary, and it was not used until we were convinced that the caves were devoid of women and children. On more than one occasion I have endangered myself by waiting outside the caves helping weak women and children laden with their belongings to a place of safety.”

Colin Harding’s account of this episode in his book Far Bugles is as follows: “Between the attack made on Makoni’s kraal by Colonel Alderson on or about August Bank Holiday, and the attack made by Major Watts, which I am describing, Makoni had made signs that he wished to surrender on condition that his life should be spared. This request went through to the proper authority, i.e., the High Commissioner, and Makoni was informed that he would have to submit to a trial and the question of life or death would depend on the result of a trial.

Apparently, under those conditions, Makoni, who always denied the committal of any murders, refused to surrender, and as a result Major Watts made his attack. It is alleged that during the time that we were sitting round Makoni’s cave, he was informed that if he surrendered, his life should be spared. I am not in a position to say whether or not this was the case, but this I know, that if he did not surrender on some implied conditions or the other, he contemplated doing so when he came to the mouth of the cave and was captured by an officer who claimed him as prisoner who had unconditionally surrendered. Makoni was tried by a court martial, he was found guilty of being a murderer and a rebel, sentenced to be shot, and it was my unfortunate duty to be in charge of the firing party which carried this sentence into effect. Makoni died a brave man, whether he was a murderer, rebel or the devil incarnate. The trial and subsequent death of Makoni was the subject of an investigation which exonerated Major Watts, after he had been under open arrest for some considerable time. Whether he acted rightly or wrongly, he acted as he considered expedient, and in accord with the great majority of his brother officers who were there. I leave it at that."

Because of the controversy around Chief Chingaira Makoni’s death and his part in charge of the firing squad I have also quoted Colin Harding’s account of the same incident in his later 1938 book Frontier Patrols: "Eventually when endeavouring to escape or else with the idea of surrender, he [Chief Chingaira Makoni] came to the cave’s mouth where he was seized and made prisoner. A court-martial was held resulting in a judgement of death. Whether he voluntarily surrendered or whether he sought to escape is uncertain. Makoni adhered to the former supposition, and again demanded a trial at Salisbury. He was overruled and sentenced to be shot; and placed in command of the firing party, I, reluctantly, had the duty of carrying the sentence into effect. Makoni was certainly a rebel, and with equal conviction I found him a brave man. As such he faced his doom and the trying ordeal which preceded his death. To me, myself, he bore no malice, and taking his two small sons who unknowingly came to see him die, he placed them under my charge. As they were led reluctantly away, their father whether good or bad, whether guilty or innocent (and who can tell?) was hurtled into eternity.

As elsewhere I have related, the two lads became my faithful and devoted servants, and to the regret of many white men who with myself had grown to appreciate my small charges, Paris, the elder, was fatally wounded when later we attacked Kunze’s kraal, and in spite of good and kind nursing, died eventually in the native hospital in Salisbury.”

However, this view is balanced by an old Shona man who said to “Wiri” Edwards, Native Commissioner at Marandellas: We saw you come with your waggons and horses and rifles. We said to each other: “they have come to buy gold, or it may be to hunt elephant, they will go again. When we saw that you continued to remain in the country, and were troubling us with your laws, we began to talk and to plot.”

This execution continues to be controversial with a number of sources alleging that Chief Chingaira Makoni’s head was hewed off as a trophy and is kept in a British Museum and the Chieftainship itself continues to excite debate.

Acknowledgements

P.S. Garlake. Pioneer Forts in Rhodesia 1890 – 1897. Rhodesiana Publication No. 12, September 1965. P37-62

V. Somerville. Mashonaland Branch Outing to the Rusape Area. Heritage of Zimbabwe. No. 10, 1991. P99-101

T. Tanser. Chief Makoni and the Shona Rebellion 1. Heritage of Zimbabwe. No. 10, 1991. P105-111

E. Goodwin Green. Raiders and Rebels in South Africa. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1976

E.A.H. Alderson. With the Mounted Infantry and the Mashonaland Field Force 1896. Books of Rhodesia reprint. Bulawayo, 1971

R. Hodder-Williams. Marandellas and the Mashona Rebellion. Rhodesiana No. 16 July 1967. P27-55

C. Harding. Frontier Patrols. G. Bell & Sons. 1938

C. Harding. Far Bugles. Simpkin Marshall Ltd. 1932

Notes

[i] Marandellas and the Mashona Rebellion, P42

[ii] Raiders and Rebels, P94

[iii] The ’96 Rebellions, P73

[iv] Foreword to the Reprint

[v] Ibid

[vi] Lieutenant Stockley was the husband of Cynthia Stockley, the authoress but they separated the same year.

[vii] Ibid, P97

[viii] Earl Grey had been a director of the British South Africa Company and was asked to take-over the role of Administrator after Dr Jameson carried out his abortive raid on Johannesburg