Was Archibald Ross Colquhoun; first Administrator of Mashonaland 1890 – 92, a failure or was he actively undermined by Dr Jameson?

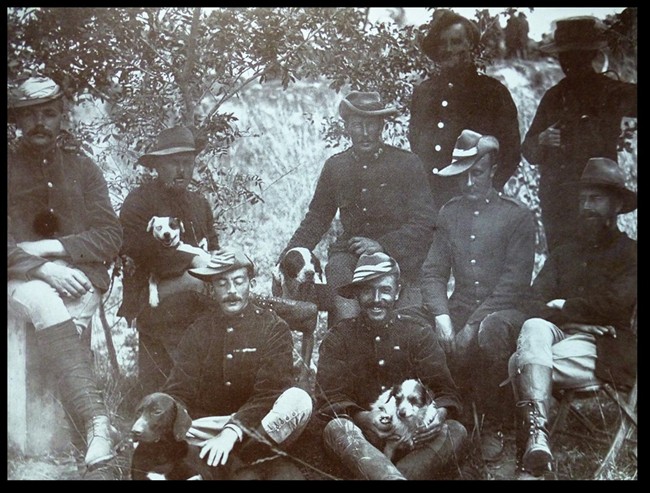

In his article ‘Colquhoun in Mashonaland: A Portrait of Failure’ in Rhodesiana Publication No 9 of December 1963 by J.A. Edwards the author begins with the rhetorical question of who was the most important man in the Pioneer Column? Was it Lieut-Col Eduard G. Pennefather, who commanded the Police? Frank Johnson because he led and organised the Pioneer Corps? Frederick C. Selous, the guide, because he selected the route to Mashonaland? Dr Leander S. Jameson because he represented Rhodes and carried his power of attorney? Or Archibald R. Colquhoun because he was the future administrator of Mashonaland from October 1890 to September 1892? All but Pennefather appear in the photo by Ellerton-Fry below.

Ultimately none of them enjoyed a lengthy career employed or contracted to the British South Africa Company as will be explained.

Ellerton-Fry 1890: Dr L.S. Jameson, C.F. Harrison (Colquhoun’s secretary) F.C. Selous, A. Colquhoun

All of them, except Colquhoun, had a role to play in the Pioneer Column’s journey that began on 5 July 1890 when B Troop under ‘Skipper’ Hoste crossed the Shashe river. Colquhoun’s responsibilities only began on 3 September 1890 when he, accompanied by Jameson, Selous and a small number of troopers left the Pioneer Column to negotiate a treaty with Chief Mutasa.

Background to A.R. Colquhoun (March 1848 – 18 December 1914)

Archibald Ross Colquhoun (pronounced ka-HOON) was born in March 1848 on the Alfred during a violent storm off Cape Town, the fifth child of Archibald Colquhoun and Felicia (née Anderson) He describes his family background in some detail, how his grandfather was in the army in India, his father as a typical Scot ‘of a vanishing type’ who ‘would be a soldier but had to be a doctor.’ How his father joined the East India Company’s service as an assistant surgeon, and operated under difficult conditions at Quetta and Kandahar and earned his title as ‘the fighting doctor’ during the disaster at Kabul.

But his father suffered from ill-health after the Sikh campaign and retired in Scotland. He says he learnt nothing at school but was very distressed at his mother’s death and his father’s remarriage, and he did not get on with his step-mother. He did an engineering course and in 1871 left Scotland to work as an assistant surveyor with the Indian Public Works. His book Dan to Beersheba describes the friends he made, the sports they played and life in a bachelor bungalow.

He was transferred as the secretary and second in command of a Government Mission to Siam and Siamese Shan States. He describes Rangoon in the 1870’s before being recruited to fight the dacoits and marching with the sepoys and their elephants and was involved in skirmishes taking dacoits as prisoners.

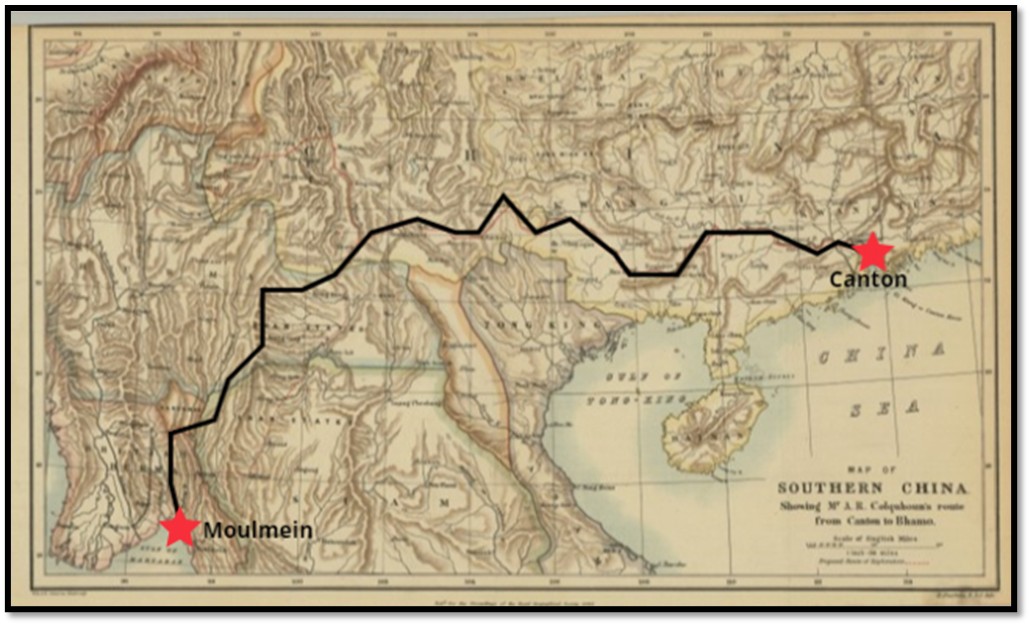

He then conceived a plan to explore southern China starting at Canton and travelling up the Pearl river (Zhejiang) with his companion C. Wahab to establish the best route for a railway connecting Burma and China. Their translator soon deserted and Colquhoun describes the food and customs of the people – how they fish with cormorants, they had much trouble with servants, and in Shan country find there is a reward on their heads. They faced many difficulties and dangers, including starvation and imprisonment, before finally reaching Rangoon.

A.R. Colquhoun’s route across Southern China from Canton to Moulmein 1882-3

On his return to Scotland he wrote Across Chrysê and in 1884 was awarded the Royal Geographical Society’s Founders Medal ‘for his journey from Canton to the Irrawaddy.’

In the same year he was appointed a Times correspondent “the pay and allowances seemed to me princely” and left for Tonkin to report on the Sino-French War (1884–1885) Tonkin, now part of Vietnam, was considered a crucial foothold into Southeast Asia and the key to the Chinese market. It had been invaded by the French in the Tonkin Campaign, was then a colony of France as French Indochina, with Hanoi becoming the capital in 1901. The French and Chinese fought several bloody battles. He concludes, “I have seen something of war and know that it cannot be waged with kid gloves, but the method of village burning and country wasting is as wasteful as it is cruel and turns peaceful people into homeless brigands and recoils eventually on the conqueror.” His articles to The Times were very critical of the military strategy of the French commanders, his telegrams quickly became censored and things were made difficult for him.

In 1885 he wrote Burma and the Burmans: Or ‘The Best Unopened Market in the World in which he argued that the only thing preventing British business from making a killing in the region was the despotic and incompetent king Thibaw, who had succeeded his father in 1878. Inheriting the Burmese throne was never straightforward as kings routinely had dozens of children to compete for the title. Thibaw, who was twenty-one when he took the throne, shortly afterwards had eighty-three members of the royal family killed; the women were strangled, and the men were tied up in red sacks and beaten to death with paddles. (The idea was to avoid any visible shedding of royal blood—though some accounts have the men being trampled to death by elephants, which must have been at least messy)

The proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and monthly record of Geography, November 1882: “Explorations through the South China Borderlands.”

After a spell in Hong Kong he travelled to Port Arthur, and then to Siam (Thailand) to view the proposed railway connection between Burma and China, after which Colquhoun wrote his book Amongst the Shans. He was sent on a mission to Upper Burma to persuade King Chulalongkorn that a rail connection would be to his country’s advantage, but the railway proposal did not get off the ground.

In 1885 when he suggested in the Times that Britain annex Upper Burma, he was appointed as the Deputy Commissioner for Upper Burma, then an extension of India, writing that, “dacoit hunting was, however, our principal occupation…the country, even before we took it over, had got into a state of anarchy. Bands of robbers lived by terrorising the districts…” and they were ruthlessly hunted down and captured by the sepoys. In 1889 he criticised Lord Ripon saying he always followed a policy of, “put it off to the latest moment and then half-hearted interference.” He wrote, “I think I really deserved my Burmese nickname of ‘Blazes’ for I was always blazing away at someone and at last I had overstepped the mark.” This brought down a warning from his superiors.

Then having written a defence of his previous remarks with some severe criticism of his superiors that he intended to send to the Times correspondent, he placed the letter in the wrong envelope, addressed to those same superiors and was finally suspended from duty. Nominally he remained in the same post until 1894, but found he was no longer given any meaningful responsibilities and began to search around for a new post writing, “I am afraid that the free hand that I had enjoyed as the Times correspondent made me less and less inclined to knuckle under to any official regime.”

When recommended for a post in Baluchistan that he considered a demotion, he wrote, “At the time I was very hot about it…but I see now that I was treated with generosity after being guilty of insubordination…”

How did Colquhoun get appointed as Administrator of Mashonaland?

In protest, Colquhoun took long leave in Scotland and, “began to look about for another sphere of action. Among my friends and acquaintances was Rochford Maguire, who introduced me to Alfred Beit, and the latter, after I had seen him several times, gave me letters to Cecil Rhodes in Kimberley. He was so keen that I should go that he actually secured for me a passage out in the kindest way.” Buckle, his former Editor at the Times, in a letter also recommended his work in Burmah.

Rochfort Maguire Wikipedia: Cecil Rhodes and Alfred Beit c. 1900

Leaving England on 29 November 1889 on the S.S. Mexican among his shipmates were Charles Rudd and Col Frank Rhodes who then accompanied him to Kimberley by train. It was public knowledge that the concession had been won from Lobengula and the British South Africa Company (B.S.A. Co.) had been formed for its development, but not much else was known. On Saturday 28 December Colquhoun was informed that he had been hired in an administration post and would be in Kimberley for about six months, and then go up to Mashonaland, the letter reading:

December 28 / ‘89

Dear. Mr Colquhoun,

I am prepared to offer you an appointment with salary of £800 per annum pending our obtaining civil administration in the Chartered Co. territory, after which I will find you an independent post in the civil administration at a salary of not less than £1,500 per annum. Of course, the latter depends on our obtaining. the administration of the country.

Yours truly, C.J. Rhodes

For the British South Africa Co.

PS My idea would be to give you charge of Mashonaland as soon as practicable.

Colquhoun was still technically on long leave, so he wrote to the Indian government asking if he could retire with his accumulated pension. The request was refused, but he was allowed to go on secondment for three years, although in fact, at the end of that period, he was allowed to resign.

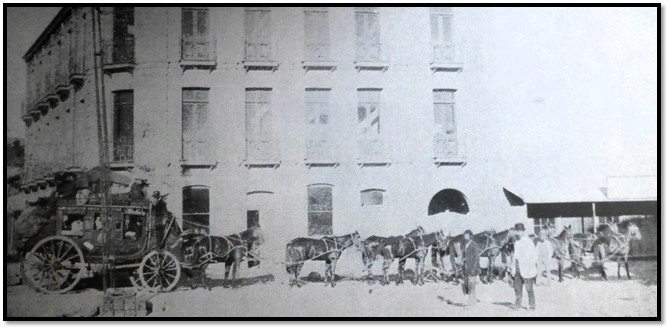

The coach leaving Kimberley for the north in 1889

During his time at Kimberley, apart from drafting letters for Rutherfoord Harris, the B.S.A. Company secretary, Colquhoun took the three and a half day journey to Pretoria by stagecoach drawn by sixteen mules; “nine inside passengers and an unlimited number outside on the knife-board, with luggage piled up on the rumble behind and littering every corner of the coach inside.” Rhodes sent him to sound out President Kruger and if possible to find out without direct questions what was his attitude to the ‘northern expansion.’ In 1890, Paul Kruger was 65 year old, but a strong-looking man. “He sat in a leather-covered armchair, in dirty-looking clothes, his hair and beard long, a big Dutch pipe in his mouth and a huge red bandana handkerchief hanging out of the side pocket of his jacket. A prominent piece of furniture was a large spittoon, of which he made frequent use. There is no doubt that, with all his surface rusticity, Kruger is a genius – a master of statecraft. His most striking characteristic was a sphinx-like immobility of countenance – no one could forget that great pale heavy face and the little eyes, whose lids closed over them like the hood of a cobra. He did not speak English and professed not to understand it, though as to this last I had my doubts.” He doesn’t say if he managed to get any opinion from Kruger on the subject of his journey there!

Wikipedia: Paul Kruger, Sir Henry Loch,

President of the Transvaal Republic High Commissioner for Southern Africa

Following this he visited Rhodes at Groote Schuur and met Sir Henry Loch, then British High Commissioner for South Africa. Loch knew Colquhoun’s father; they had been in the same regiment in India in 1844. This made Loch very friendly towards Colquhoun and they corresponded frequently in 1890-91.

The chief guide to his future role lay in the Memorandum of Instructions for Mr Colquhoun that Rhodes gave him on 13 May 1890. In his article Edwards lays out the most important ones:

1. You will accompany the Selous Road expedition on its way into Mashonaland. On the 30th of September next, or as soon after that date as possible, you will assume the Administration of Mashonaland.

3. You will be unofficially attached to the Expedition while on its way into Mashonaland and will not be held responsible in any way for the conduct or carrying out of the expedition for which the contractors and Lt-Colonel Pennefather…will alone be responsible. You will, however, from time to time, report as to the progress of the Expedition.

4. As soon as practicable after entering Mashonaland, you will, accompanied by Mr Colenbrander (as interpreter) and a small escort of Police, should you think it advisable to take them, visit the Chief of the Manica country, and obtain from him on behalf of the Company, a treaty and concessions for the mineral and other rights in his territory…You will endeavour to secure the right of communication with the seaboard, reporting on the best line of railway connection with the littoral from Mashonaland…On returning to Mashonaland, for the purpose of taking over charge of the Administration, you will, if advisable, leave a representative with the Manica Chief.

5. On assuming charge as Administrator, you will endeavour to carry on the administration without employing the members of the expedition (who receive a high rate of pay) and will requisition such a number of Police as may be found necessary, thereby releasing the members of the expedition for their prospecting work, etc.

6. On the way up, and after entering Mashonaland, you will examine the country, so far as possible, and select one or more town sites…

7. After arrival in Mashonaland, do your best to encourage prospecting and developing as the first work to be undertaken by the Pioneers...

8. You are supplied with copies of the proposed ‘Mining Law for Mashonaland’ prepared under my supervision…You will be supplied with copies of the ‘Laws and Regulations’ which are being prepared by Sir Sidney Shippard for use in Mashonaland…

11. A regular Postal service should be established between Mashonaland and the Bechuanaland Protectorate border.

12. The necessary Registers and Books should be set on foot and the necessary clerical establishment for this purpose, and for carrying on work generally, should be employed by you.

13. You have the power to appoint provisionally such Resident Magistrates and Mining Commissioners and to employ such surveying establishments, on a simple scale, as may be required…

16. Wherever not provided for by the Mining Law, the Laws and Regulations, or these Instructions, you will be guided by the British Bechuanaland Laws and Regulations and Procedure…

17. You will report to and communicate with this office, which will submit your reports to Home Board.

Preparations start with the granting of the royal charter

With the grant of the royal charter on the 29 October 1889 the B.S.A. Co. had the right to construct railways and telegraphs, to promote trade and colonisation, and finally to develop the minerals and other resources of Mashonaland. To give practical effect to the charter it was decided a Pioneer Column should go up and establish itself in Mashonaland. Colquhoun was to accompany the Column and report on its progress and, if settlement was successfully accomplished, to draw up the regulations for the new community.

It was at Loch’s insistence that the Pioneer Column should be accompanied by a protective force of Police, much to Frank Johnson’s annoyance. Capt P.G. Forbes was the first officer recruited on 16 November 1889; Lieut-Col E.G. Pennefather was only appointed in command on 1 May 1890.

Colquhoun writes they did not leave Kimberley with any fanfare of trumpets, on the contrary, “to avoid attracting attention we dribbled out of Kimberley and our first gathering place was Macloutsie …”

In 1885 the territory south of the Molopo river became the colony of British Bechuanaland, was eventually incorporated into the Cape Colony and is now part of South Africa. Territory to the north of the river became part of the Bechuanaland Protectorate under King Khama III.

The Pioneer Column gets underway

The Bechuanaland Protectorate was the training ground for the Pioneer Column with its escort of British South Africa Company Police, indeed without Khama’s cooperation it is doubtful that the march would have taken place. It began on 11 July 1890 when the Shashe river was crossed at Fort Tuli.

Colquhoun’s description of the march from Fort Tuli is very sketchy for a newspaper correspondent and author. “We rode in column formation. Selous with his scouts (most of them lent by Khama) went on in front and spread out on either side, the Pioneers and Police surrounded the waggons, and the guns brought up the rear, with more scouts behind. With all the precautions we could take however, we were conscious that in the broken and scrubby country [i.e. Fort Tuli to Fort Victoria, now Masvingo] which became more and more difficult as we approached Mashonaland, we could have been cut up in a few moments by a determined attack. We were anxious and on the alert until we reached the open country, but on the high plateau of Mashonaland we breathed more freely.”

Colquhoun’s responsibilities start with the negotiations for a treaty with Chief Mutasa

On 26 August Colquhoun, the administrator-designate, left the Pioneer Column near Fort Charter with Dr Jameson, Rhodes’ personal representative; Harrison, Colquhoun’s secretary and Selous, the intelligence officer, and struck across country for Manicaland. Jameson was thrown from his horse and injured and returned painfully to the Pioneer Column, but the others set off once more on 3 September with an escort of seven Troopers under Lieut Adair Campbell and travelled to Chief Mutasa’s kraal on Bingaguru. Mutasa appeared at midday, “attired in a naval cocked hat, a tunic (evidently of Portuguese origin, but of ancient date) a leopard skin slung over his back, the whole… being completed by a pair of trousers, that had evidently passed through many hands, or rather covered many legs...” On the 14 September 1890, a concession was obtained from Mutasa that extended the B.S.A. Co’s influence over Manicaland. Mutasa stated he was tired of Portuguese threats, intimidation and interference and granted mineral rights over Manicaland for £100 and B.S.A. Co. protection.

Colquhoun had been instructed to define Mutasa’s territory to the widest extent, preferably to the sea, but it was soon clear any such claims could not be confirmed, Mutasa was really a petty chief and European gold prospectors were already working under licences from the Mozambique Company whose base was at Massi Kessi (Macequece / Manica)

The concession was quickly disputed by the Portuguese Mozambique Company, clearly Mutasa was playing off both sides, probably through fear, and in fact secretly informed the Portuguese that he had only signed the treaty under duress! Colquhoun decided that immediate steps must be taken to demonstrate effective occupation of the new territory and posted Lieut M.D. Graham and four troopers at Mutasa’s kraal. Back at Salisbury he instructed Capt P.W. Forbes, the senior Police officer in the absence of Lieut-Col Pennefather , to go to Manicaland and occupy as much territory as possible eastwards towards the Pungwe river.

Photo by Lieut. W. Ellerton-Fry – British South Africa Company’s Police Officers

L-R, back row; Lieut. CWP Slade (B Troop) Surgeon-Capt. RF Rand (HQ)

Middle row; Sub-Lieut. MHG Mundell (B Troop) Capt. PW Forbes (B Troop) Lieut-Col EG Pennefather (OC the Pioneer Column) Lieut. D Graham (Adjutant HQ) Canon F. Balfour (Chaplain HQ)

Front row; Sub-Lieut. the Hon EW Fiennes (A Troop) Capt. HM Heyman (A Troop)

Colquhoun finds himself being undermined and overruled

Colquhoun had believed he was the key figure in Mashonaland, but soon came to realise he was not; that, in fact, Jameson was the authentic representative of the B.S.A. Co. It was a deceitful arrangement which placed him in an impossible situation and naturally the reality could not be explained to him.

The first sign of trouble came when a letter from Rutherfoord Harris reached Colquhoun as the Pioneer Column left Fort Victoria in August informing him that Jameson and Selous were to accompany him in his negotiations with Chief Mutasa in Manicaland, although Jameson’s accident prevented him from going. Immediately before leaving the Pioneer Column for the second time on 3 September Colquhoun wrote to Harris, “by this mail Jameson has received from you a letter containing certain instructions with regard to the Manika Mission, of which I myself have had no advice from you. As I have been entrusted with this Mission by the Board, and have full instructions from Mr Rhodes on the subject, I think these instructions should have come to me. Please communicate with me in future in such cases. On this occasion no harm is done, but confusion might arise if I alone am not instructed in such matters.”

The next day he wrote to Harris again, “I shall expect that all official correspondence shall be sent to me, or through me in the case of the O.C. police, [Pennefather] who will be the same as the Inspector-General of Police in India and Burma, etc, I take it. It might be as well, if any doubt exists on the subject to refer the matter to the High Commissioner [Loch] or his secretary, as the procedure should be clearly laid down.”

Colquhoun is unhappy about communications to Jameson by-passing him

Things went downhill from there on. In September Colquhoun wrote to Harris, “I have written to Rhodes regarding a certain amount of friction between myself and Jameson. Your writing to Jameson suggestions and quasi-instructions direct was very irregular and unfortunate, and I have been compelled to tell Rhodes so. It has undermined my authority and Jameson has not cooperated with me as I hoped he would.”

Matters did not improve. On 4 October a telegram from Harris to Lieut-Colonel Pennefather said, “I have to urge upon you that…you should at once proceed yourself with HQ staff and occupy the whole of the Manica country” and ended ominously: “It is not necessary to repeat all this to Colquhoun.”

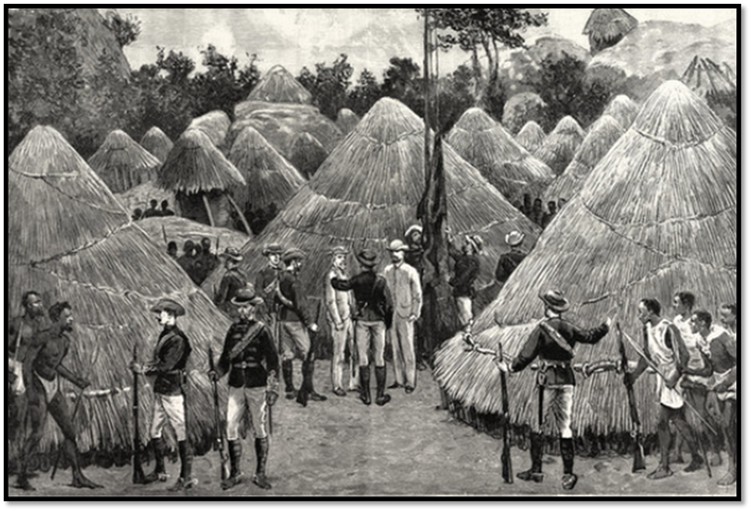

Portuguese officials are arrested at Mutasa’s kraal at Bingaguru Mountain

Forbes was at Mutasa’s by 5 November and learnt that Col. Paiva D’Andrade as well as Baron de Rezende and Gouveia, the Portuguese governor of Gorongoza province, were both at (Massi Kessi) (Macequece, now Manica) Lieut Graham was sent to ask them to withdraw, but they replied that the B.S.A. Co. had no rights in the territory. Forbes played for time, knowing Lieut the Hon Eustace Fiennes was riding from Fort Charter with 25 troopers from A Troop.

Gouveia and D’Andrade then entered Mutasa’s kraal with their armed followers and together with Baron Rezende at a meeting persuaded Mutasa to backtrack on his concession agreement with Colquhoun. As soon as the A Troop reinforcements arrived, Forbes entered Mutasa’s kraal with 10 men, arrested D’Andrade and Gouveia and dispersed their followers. For a complete description see the article How Mutare and Manicaland were annexed from the Portuguese under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Forbes arrests Gouveia and Andrada at Mutasa’s kraal on Bingaguru – the Portuguese flag is hauled down

Jameson and Johnson propose travelling through Portuguese territory

Colquhoun warned Dr Jameson and Johnson about travelling through Massi Kessi and the Pungwe river on their return to Cape Town as dangerous, and not in the Chartered Company’s interests, but was ignored.

He wrote to Rutherfoord Harris in early October, “Jameson had formulated certain plans re going out via Manika (sic) with Johnson, which did not seem to me to be in the best interests of the Coy. Holding the instructions I did (both from Mr Rhodes and the Board) I thought it my duty to the work, more especially as I did not understand, and did not approve, the intimacy existing between Johnson and Jameson. I thought it very inexpedient, in the interests of the Company, that Johnson should go out via Manika until matters were quite settled there and I know from you that you held the same view. This view was strengthened after my visit to Manika and after the execution of the Treaty [with Chief Mutasa] especially as the earlier situation was complicated by the Portuguese being in a state of intense irritation, not likely to become less after the Anglo Portuguese Agreement…I have let Jameson know that I wrote to Rhodes to say that he had not supported me and had endeavoured to weaken my authority”

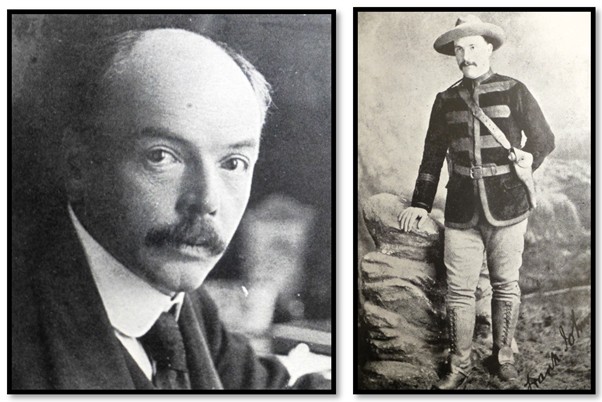

Dr L.S. Jameson Major Johnson in Pioneer uniform

The differences between Colquhoun and Jameson grow wider

Jameson wrote to his brother Sam on 11 November, “Entre nous, I have had rather a tiff with Colquhoun, who is an ass…”

Jameson and Johnson were overtaken on their way to the Pungwe river by a Police trooper, “who saluted shamefacedly and said he had come from Colquhoun with orders to arrest them and take them back to Salisbury. Damn the fellow! said Jameson, I got him his job.”

But Colquhoun to his intense surprise, soon learned from Harris that, “Rhodes would like Johnson to go through to Pungwe unless there are very strong objections to it.” Colquhoun wrote back saying this was the first time he had heard this was Rhodes’ wish and that he always understood the opposite was true.

When Jameson and Johnson arrived at Cape Town after their eventful trip down the Pungwe river, Colquhoun received a telegram from Rhodes stating, “approve all that has been done.”

Forbes, encouraged by Colquhoun, follows up his initial success in Mozambique, but is forced to turn back

Forbes marched into Gorongosa, and then eastward towards the coast, hoping to acquire further concessions from independent chiefs. His small force, severely hindered by malaria and lack of food, were in the Pungwe Valley, when Colquhoun had them called back to Massi Kessi. Colquhoun knew that this question was bigger than the Mozambique Company – it involved Portugal who claimed sovereign rights over the territory.

Rhodes did not give up on acquiring further concessions from chiefs in Portuguese-claimed territory

Dr Auriel Schultz, a Natalian and Rhodes acquaintance, negotiated a concession with Chief Gungunyana in which full mineral and commercial rights were granted to the B.S.A. Co. in return for 1,000 rifles, 20,000 rounds of ammunition and £500 per annum. Dr Jameson, accompanied by Dennis Doyle and Dunbar Moodie left Old Umtali on 10 January 1891 to sign the agreement. In the rainy season and through unexplored country they faced daunting conditions but arrived at Gungunyana’s kraal on 2 March.

Their arrival coincided with the appearance of a small steamship, the Countess of Carnarvon, together with the arms and a small detachment of Company Police at Xai-Xai on the Limpopo river. Although the delivery was made, Jameson was detained by the Portuguese, but they did not find the concession and he left on the ship for Lourenço Marques (Maputo)

The big question for Colquhoun of course, was why had Rhodes instructed Jameson to conduct these negotiations and not himself, if he was meant to be in charge of administration. The answer was clearly, Jameson was de facto in charge and not Colquhoun.

Their differences were clear to others. A.G. Leonard wrote in June 1891, “Speaking of Colquhoun and Jameson, Graham informs me that, in the first instance they were great friends, but afterwards, on their way down to Manica, Jameson tried to take the administration of affairs into his own hands and so they fell out.”

The 1890/91 rainy season in Mashonaland was unusually long and heavy

The heavy rains made life for the newly arrived Pioneers and Police very difficult. The flooded rivers to the south made transport impossible; ox-wagons were kept stationary on the riverbanks for weeks at a time; food supplies ran short and malaria fever proved deadly. Many isolated prospectors and sick police died, particularly in February 1891 and at Fort Tuli Capt A.G. Leonard estimated that at least 97% of the horses died of horse-sickness, known as ‘dikkop.’

Chris Ash in The If Man writes, “During the first rainy season, with Colquhoun in charge, there had been huge problems with supply waggons not getting through and the colony had come close to disaster.” Clearly Colquhoun was not responsible for the wagons being held up for weeks by flooded rivers; perhaps the sentence construction is just muddled.

Colquhoun’s three biggest external problems facing Mashonaland in 1891

There were:

(1) The ever-present threat of an attack into Mashonaland by the amaNdebele. In November 1890 Chief Lomagundi (Magundi) whose kraal was 70 miles (112 kms) north-west of Salisbury had submitted to one of Gouveia’s Portuguese agents and hoisted the Portuguese flag. For this and refusing to pay annual tribute to Lobengula he was killed with four of his councillors by a small raiding party of 30-40 amaNdebele under Malete. When Forbes arrived a week later with B.S.A. Co. Police he was told the amaNdebele had asked the chief, “why he had taken presents from the Portuguese and English and had shown the English the way to dig for gold and also why he had given guides to take white men to the Zambezi without taking leave of Lobengula, to whom the country belonged.” This brought home the military threat that the amaNdebele represented.

(2) The growing dispute with the Portuguese over Manicaland who maintained that their writ ran as far west as the Sabi (Save) river. Portugal and the United Kingdom had agreed the modus vivendi on the 14 November 1890, whereby they agreed to halt any hostilities and freeze their territories. Forbes’ surprise arrest of D’Andrade and Gouveia at Mutasa’s kraal on the following day had aroused widespread popular indignation in Portugal and large numbers of students and others volunteered to oppose the Chartered Company’s expansion. They arrived from February 1891 at Beira and for the next two months moved steadily towards Manicaland, but with heavy losses from malaria.

The governor of Manica and Sofala, Col Joaquim Machado, declared martial law and closed Beira and the Pungwe river to foreign traffic. This was a great blow to the firm of Johnson, Heany and Borrow who had contracted to build a road from Mashonaland to Fontesvilla, the highest navigable point on the Pungwe river. They had commissioned a road making party in Durban under the command of Sir John Willoughby and that arrived in the steamship Norseman at Beira along with the tugs Agnes and Shark.

Johnson had announced his intention to open a road with coaches from the Pungwe river, but the plan became a disaster. Dr James Johnston writes on 16 July 1892, “We are now in the tsetse-fly belt. We passed 17 wagons today that had been left to their fate on the veldt for several months - the result of a rash venture on the part of a company to transport goods from Beira up to the interior. The ‘fly’ killed off the oxen, numbering some 400 and valued at £7 each, and so the wagons, of an average value of £130 had to be abandoned.”

(3) The threat to the south posed by the Adendorff trekkers from the Transvaal Republic and their planned incursion into Banyailand. In fact, this threat never materialised. See the article The Adendorff Trek and the planned invasion of Banyailand under Masvingo Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Colquhoun’s internal administrative duties

Rob Burrett comments on how the unsupervised activities of prospectors in the Lomagundi district was a growing concern for the B.S.A. Co administration in Salisbury and notes that gold claims had to be registered, claim boundary disputes settled, and royalties collected, but its remoteness from Salisbury precluded effective administration. To solve this problem, Lewis A. Vintcent, was appointed acting Mining Commissioner for the district on 28 February 1891 and after a journey made difficult by flooded rivers during the 1890-91 rainy season settled at Spreckley’s hilltop camp, just west of the Hunyani (Manyame) river. Initially called Colquhoun’s camp, but later Spreckley’s camp after Colquhoun’s departure.

Most of the prospectors were seriously ill with fever and Vintcent found himself increasingly caring for them, a problem exacerbated by shortages of supplies and medicines, dangerous wild animals, little communication with Salisbury and disappointing gold discoveries, despite glowing sample assays. He himself fell ill in late April whilst visiting Golden Kopje camp and died of fever whilst his friends tried to get him to Salisbury.

He was succeeded in the post by Jack Spreckley, a well-known early pioneering character, who was appointed acting on 29 June 1891 and confirmed in 1892. His duties included inspecting shafts, settling claim disputes, dealing with labour troubles, collecting royalties and even shooting problem lions.

Land rights become an administrative issue

The purpose of the Pioneer Column was to establish a settlement at Mt Hampden, later changed to Salisbury, which would be the core of the B.S.A. Co’s commercial empire in Zambesia. The pioneers were volunteers and as an inducement were each promised one alluvial and ten quartz claims and 1,500 morgen (3,175 acres) of farm land. Many who had become disillusioned with the Rand now looked to Mashonaland as an alternative. Frank Johnson, in addition to any profits he made from the £88,340 he was authorised to spend, was granted land rights of 40,000 morgen (84,678 acres) in Mashonaland.

But, in fact, there was no land for the Chartered Company to give. The Rudd Concession gave mineral rights, but not land rights, and Colquhoun could not issue titles to land until Lobengula agreed. He was advised that if the pioneers pressed him for their 1,500 morgen land rights, he should allow them to ‘ride off’ the boundaries in Boer fashion and grant them provisional title.

Did the lack of B.S.A. Co. administration give Colquhoun an impossible task?

Dr Jameson deliberately stood aloof from all the administration detail of running Mashonaland and with few trained staff and surveyors and lack of supplies due to the heavy rains, Colquhoun had to battle to set up some sort of administration and to sort out the Pioneer claims and boundary surveys. It’s no wonder he found himself condemned as a petty bureaucrat by Frank Johnson, “Being an old Indian Civil Servant, he was obsessed with rules and regulations.”

In reality the administration in Mashonaland was completely inadequate for the task in terms of personnel and resources to perform more than the minimum duties required.

It appears that Dr Jameson actively undermine Colquhoun’s authority from the start

In Mid-July 1890 Colquhoun had written, “Jameson and I are practising veld life like a couple of new chums and are enjoying it immensely. We are as fit as possible and all the better for the change from the flesh-pots of Kimberley.” Frank Johnson bitterly opposed Lieut-Col Pennefather being given overall command of the Pioneer Column and objected to Selous as Intelligence officer. Colquhoun and Jameson eased the tensions between them that Colquhoun said, “requires some skill to smooth over. Jameson and I do what we can to prevent a rupture.”

This quote below from Edwards’ own article rather invalidates his arguments and shows that Jameson actively undercut Colquhoun’s authority from the very beginning; Jameson would have undoubtably have had Rhodes’ support. Colquhoun had secured the treaty with Mutasa and prepared to return to Salisbury where Pennefather was acting Administrator. He writes on 4 October to Harris, “on arrival at Mount Hampden, which I hope to reach on 7th, I shall write to you regarding the friction which unfortunately arose between Jameson and myself in connection with the Manika Mission. Jameson viewed my determination to undertake and carry through the Manika work (which I was bound by my instructions, para 4 to do) from the outset with evident disapproval. He wished to have the conduct of the Mission in his own hands, perhaps because he considered me not the right man for the work. At any rate, far from supporting me as a colleague (as I hoped he would have done) from the moment he found I meant to go and do the work, he threw difficulties and obstacles in my way, and this was noticeable to others as well as myself. As I have already written to you, in telling you I had been compelled to write to Rhodes on the subject, your sending instructions, etc., direct to Jameson, while I (who was charged with the work) was left unadvised, did not tend to make matters smoother.”

On the 15 November Colquhoun again wrote to Harris in the same vein, “I have no wish to carry on a controversial correspondence regarding the Jameson incident. It is useless to support the theory that the friction and rupture occurred from my needlessly taking offence about your having written Jameson instructions on one occasion. The causes of the misunderstanding lay far deeper, as you yourself well know. It was no case of procedure or etiquette, but whether I was prepared to allow myself to be supplanted, to have my authority entirely sapped by Jameson.”

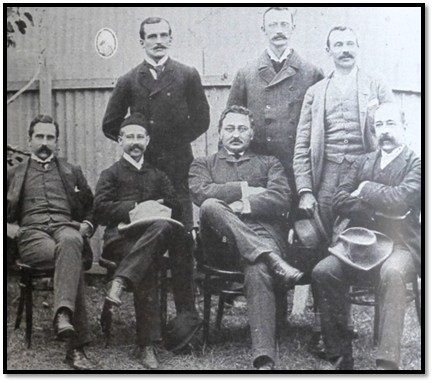

Planning the conquest of trans-Zambesia

Standing: (L-R) James Grant, John Moir, Joseph Thomson

Sitting: (L-R) James Rochfort Maguire, Henry Hamilton Johnston, Cecil Rhodes, Archibald R. Colquhoun

However when Jameson returned to Salisbury in December 1890 after his trip down the Pungwe river with Johnson he wrote that his, “arrangement with Rhodes himself is, that if I like at the end of Colquhoun’s year, I can take over the administratorship.”

Did Rutherfoord Harris also work to undermine Colquhoun’s authority on Rhodes’ instructions?

It can be argued that everything Harris did was at Rhodes’ instructions.

In August 1890 Colquhoun wrote to Harris directly, “After September 30th, I shall expect all official correspondence shall be sent to me, or through me. The procedure should be clearly laid down, it must be recollected that for some time to come the official machinery will be very small and the procedure adopted should be with the view to save inter-correspondence between the Administrator and the Police and Survey department heads etc.”

Clearly this did not happen and on 22 November 1890 Colquhoun tells Rochford Maguire, “Harris is still continuing his correspondence in a way which will lead to dual control up here. I feel confident that I can deal with the work here successfully. But authority must be centred in one hand and that mine.”

A clearly exasperated Colquhoun wrote once more to Harris on 27 October, “the system of corresponding with others – giving information, suggestions and even instructions direct, sometimes unknown to me and frequently in advance of my receiving advice – must lead to endless confusion, friction, rupture and failure.”

Despite his protests, nothing changed, “I feel so strongly that it is not possible to carry on work under the triple division of authority which has obtained, or under the dual system (Pennefather and myself) which you still adhere to, that I must ask you to lay this letter…before Rhodes for a ruling, unless you see your way to make a complete change in the system of correspondence such as I suggest…It is quite impossible to carry on work as hitherto, or now conducted …The system I have throughout advocated is the only one possible in a new country, that of authority centred in one hand – that of the Administrator who alone is held responsible - with the view to simplifying the work, avoiding a multiplication of correspondence and preventing the confusion, friction and failure which otherwise must inevitably result.”

Harris refutes Colquhoun’s criticisms

Presumably these replies were decreed by Rhodes, “At this stage, expediency rather than etiquette will be observed.”

“In Mr Rhodes’ opinion…no useful or practical purpose will be served by sending Mr Jameson’s letters through your office.”

“In Mr Rhodes’ opinion the time has not arrived for carrying out that system of official etiquette in correspondence, which no doubt will be the case when things are more developed.”

Finally on 5 December 1890, “definite instructions from Mr Rhodes, the following is in future to be our method of correspondence from this office:

(a) All police matters relate solely to Colonel Pennefather, with whom we shall in consequence correspond on this subject and with him alone.

(b) Correspondence relating to political matters, and other matters of which I deem it most convenient and expedient to write to Dr Jameson, in his capacity as Managing Director, will in all cases be sent direct to him.

(c) Letters relating to administrative details will, of course, be sent to you.

Briefly…I certainly have adopted, and shall in the future continue to adopt, the system of triple correspondence, as it was by Mr Rhodes’ express wish that I did so, and he desires me to continue the same system in future. Dr Jameson will also be able to explain to you fully Mr Rhodes’ views on this subject.”

Colquhoun gets demoted, but not dismissed

Harris wrote to the London office on 1 December, Mr Rhodes desires me to say, in reference to his request that the Board should authorise him to send Dr Jameson into Mashonaland, with full powers to represent him, that, from repeated instances that have occurred in Mr Colquhoun’s letters and cablegrams officially to Mr Rhodes, there's been a great want of judgement and tact in dealing not only with the difficult political matters connected with the Portuguese, but also in the interpretation of the various instructions to him…

Mr Rhodes felt, therefore, that, though still considering that Mr Colquhoun will make an admirable official with regard to departmental details, and to the organisation of the Company’s procedure, yet, owing to his lack of previous acquaintance with South African affairs, it would be distinctly advisable, in view of Mr Rhodes enforced presence as premier at Cape Town, for him to have someone thoroughly conversant, not only with the internal history of the company, and the native affairs in the north, but also one who for the last five years has had the closest personal relations with himself, and is therefore imbued with his views and aims in the north, nay, was so, even previously to the first step being taken there. Mr Rhodes can assure the board that in Dr Jameson they have one, only second to himself in capacity for dealing with the Chartered Company’s affairs, in a broad, comprehensive and successful manner.”

A tailored version of this letter was sent to Colquhoun himself with this addition, that he was, “to regard Dr Jameson as being Mr Rhodes himself, and to refer all points requiring decision and instruction to Dr Jameson, whose judgement is to be taken as being that of Mr Rhodes himself.”

The reason he wasn’t dismissed was because as Jameson wrote to his brother, “a change at present would not look well for the Company.” However another reason that Jameson disclosed was that he would prefer it if Colquhoun stayed on, as he “should hate the administrative detail work, but like the general control work.”

This statement reveals that Jameson had no love for administration – further revealed between 1892 to 1896 when he took over the reins as Administrator.

Colquhoun assents to his demotion

Colquhoun replied to Harris, “I am complying fully with Mr Rhodes’ wishes. Jameson being here with full powers will expedite the work greatly” and he reassured Jameson, “you may count on my cordial co-operation.”

Clearly the process was humiliating and in late June he asked Rhodes for, “six months leave from 1st October next, with permission to resign my appointment at the termination of that period. Dr Rand thinks I should not stay here during the next rains, and I feel in want of a change.”

Rhodes agreed, with a letter from Harris ending, “and I have to ask you to be so good on your departure from Mashonaland to hand over your office to Dr Jameson…”

Colquhoun bids Rhodes farewell

In September 1892 Colquhoun left Salisbury and called on Rhodes at Groote Schuur saying Rhodes, “was very kind and cordial to me and offered me six months’ leave and the option of returning to my post if I liked, but I felt that the avenues of promotion were few and the conditions of service not such as would suit me.”

Colquhoun’s successor, Dr L.S. Jameson

Selous writes, “I have not yet said anything concerning the administration of the country, but I will conclude this chapter by saying that I consider that it was a veritable inspiration that prompted Mr Rhodes to ask his old friend Dr Jameson to take over the arduous and difficult duties of Administrator of Mashonaland. Dr Jameson has endeared himself to all classes of the community by his tact and good temper and has managed all the diverse details connected with the administration of a new country…He was the man for the position. No other, taken all round, could have been quite what Dr Jameson has been as Administrator of Mashonaland in its early days.”

Hugh Marshall Hole also acknowledges that it was Jameson’s ability to deal with people rather than his mastery of administrative detail that made him a success. “…Jameson, who, without any previous experience of government, assumed at Rhodes's request the duties of Administrator. It was no easy post to fill. The small white community was composed almost exclusively of young men suddenly released from military discipline and scattered over a large area; all round them were wild savages of uncertain temper; the nearest outpost of civilization was Mafeking, 1000 miles away; the necessaries of life had to be dragged all that distance in slow moving ox-waggons and luxuries were unobtainable; there were no telegraph line and letters took three or four weeks to reach the railhead. Yet by his tact, a marvellous faculty of quick decision and a strong sense of humour, Jameson managed to keep the more daring settlers out of mischief and the whole community more or less contented.”

Marshall Hole, as Jameson’s private secretary when he was Administrator, can claim first-hand knowledge of Jameson’s approach to his role. “In his intercourse with those around him. Jameson was no stickler for etiquette. His chief weapon was good-humoured banter, but this was only a cloak for a real and personal sympathy which won him the confidence and affection of the circle of varied characters which the Pioneer expedition had brought together and kept the discordant elements not only in good order, but in good temper. His everyday work of administration was transacted in a large, square thatched hut, with walls of poles and mud, lined and ceiled with native-made mats of split bamboo. Here, with his feet on the table in front of him, with his chair tilted back and with a cigarette between his fingers, he would receive deputations and chat with callers, official or otherwise. They generally came to air some grievance but were disarmed by the shrewd and friendly chaff which they encountered, and, though seldom gaining their point, they invariably left in sublime good temper.”

However, despite Selous’ and Marshall Hole’s praise for his character, Jameson was a poor Administrator and handicapped by the parlous financial state of the B.S.A. Co. John Galbraith states Jameson, “…was quite unequipped by experience or temperament to oversee an efficient administration. But even if he had been a paragon of administrative virtues, he would have been unable to develop a strong, efficient government, for the board's mandate of rigorous economy reduced the administrative staff to a level of officials who with a few clerks were required to act as magistrates and mining commissioners and in a variety of other roles that made effective company government impossible. In 1893 Jameson’s staff consisted of less than twenty administrative in a territory of approximately 110,000 square miles.”

John Galbraith’s view is that “From the standpoint of the companies interests, Jameson’s great deficiency was not that he did not act in accordance with Rhodes’s intentions, but that he was an incompetent administrator. When he was removed from office, his successors found appalling acts of misfeasance during his tenure. The surveyor-general, for example, had been awarded, allegedly with Jameson's sanction, 1,000 square miles for relinquishing his private practice. The same surveyor had left the land descriptions in a shambles. H. Wilson Fox of the London office wrote to Milton : “More of the Augean stable of the past to sweep up I suppose you will say. It certainly is hard that the cleaning of all the dirty corners left by Jameson should fall on your shoulders.”

Robert Rotberg writes, “Jameson was a haphazard, impulsive, and ineffective administrator, but neither Rhodes nor others were to discover how loosely he ran the country until much later, and not conclusively until 1897 when William H. Milton replaced Jameson, reorganised the running of the Company's possession and began to clean out what Fox called an Augean stable of the past. During the years before the war against the Ndebele, and then, until the Raid, Rhodes probably only dimly perceived how badly Jameson served his own and his associates’ ambitions for the interior land. So long as Jameson quickly reduced costs, stifled or assuaged the disaffection among the settlers, and found ways to produce at least some return, Rhodes was apparently content.”

At one stage Milton claimed that Jameson had, “given nearly the whole country away to the Willoughby’s, Whites and others of that class…Jameson must have been off his head”

Photo NAZ: Hon Charles White, Col Frank Rhodes, L.S. Jameson, Hon Henry. F. White, unknown woman

How well did the others fare?

Upon the successful establishment of a colony at Fort Salisbury, Johnson, Heany and Borrow busied themselves with land and mining development, ventures which attracted capital investment from Rhodes.

Frank Johnson was the hustler Rhodes needed to get things done. Johnson went on to exploit quicker routes to Mashonaland, essential if the new settlement was to prosper and grow. Believing that Portuguese East Africa provided a far more practical transport avenue for supplies into Mashonaland, Johnson undertook an exploratory trip by boat down the Pungwe River with Jameson.

By the latter half of 1893, after the Victoria incidents, plans to invade Matabeleland were at an advanced stage. With seven hundred men at his disposal, Jameson looked to Johnson, the senior military officer in the country, to command the expedition. Jameson said the only wheeled transport would be the seven-pounders and Maxims. Johnson knew the grass would be burnt, they needed fodder for the horses, food, medical supplies and ammunition and with a small force up against 20,000 amaNdebele, wagons formed a mobile protective fort. Jameson was adamant, no wagons, and when Johnson refused to agree said, “Then I must tell you to clear out of the country at once. As long as you remain here the men, out of mistaken loyalty to you, will not go with Forbes. As it turns out, Jameson relented and the combined Victoria / Salisbury columns took thirty-six wagons!

Lieut-Colonel Edward Graham Pennefather was appointed on the 1 May 1890 as leader of the combined Pioneer Column and Police force. High Commissioner Loch imposed the Police force on the B.S.A. Co much to Rhodes’ annoyance to secure the settler population of 1,500 Europeans against the amaNdebele threat, but the force of 650 military Police at £300 per year each were costing the Chartered Company £195,000 a year to maintain, and the drain of its financial resources was causing the London Board much concern.

Marshall Hole writes that Rhodes and Jameson put their heads together to devise some means of ridding themselves of this white elephant. Jameson could not understand why the Police would not carry out civil duties such as driving post-carts, assisting in surveying farms, or doing clerical work for the administration. On one occasion he said to Pennefather, “when your men are doing nothing you show them in your returns as ‘available for duty’ but the moment I ask a man to do something, I am told he must get extra duty pay.”

Retrenchment was required. Rhodes instructed Jameson to reduce Police numbers “with all despatch” and “The Police should now gradually assume a civil form.” Thus in the months August 1891 to January 1892 Hickman records that 3 new recruits were added and 477 were discharged, reducing the Police force to 40 and the onus for defence was transferred to a newly formed body of volunteer settlers and prospectors, the Mashonaland Horse. Pennefather’s own discharge would not have been a great surprise to him.

The nursing sisters wrote in Adventures in Mashonaland: “on the 2nd January 1892, Col Pennefather rode into the camp [at Old Umtali] Everyone rejoiced to see him. He told us he projected spending the rainy season in Manica and set to work to make his hut comfortable. Great therefore was the general surprise when, on the 4th of January, a runner brought him a despatch informing him that the Military Police were to be disbanded and a Civil Police created. The Colonel’s services would therefore be no longer required. He could re-join his regiment when he pleased…The announcement was too sudden not to be unpleasant, but the Colonel took the affair very calmly: “I’ve received the Order of the Sack, Sister.” That was all he said about it. We were very sorry indeed to say goodbye to him.”

So Pennefather’s 20 months (May 1890 – Jan 1892) in Mashonaland was even shorter than Colquhoun’s 23 months (26 Aug 1890 – Aug 1892)

Lastly Frederick Selous. As already noted there was ‘bad blood’ between Johnson and Selous; Selous suggested the Pioneer Column route in opposition to Johnson’s plan to attack Bulawayo and this may have caused the friction. Selous successfully guided the Pioneer Column from Fort Tuli to Victoria; but just prior to reaching Charter Johnson writes, “Two hours later he (Colquhoun) came to me shame-facedly and asked whether I could possibly spare Selous adding, I know you cannot do so.” “You want Selous?” I replied. “Certainly, you can have him.” Right away I sat down and issued the following order: “Captain F.C. Selous, having resigned his commission this day, is struck off strength of the Regiment accordingly.” Frankly, I was glad when Selous was gone.”

Thus from his appointment in March 1890 to cut a wagon road eastwards from Palapye to being struck off as Intelligence Officer on 26 August 1890, Selous’ employment period of six months only, was the shortest. Of course, Selous went onto negotiate a treaty with Chief Mtoko and cut the Selous road from Old Umtali to Salisbury, but these were different assignments.

Edwards amateur psychological analysis of Colquhoun

Edwards discusses an incident when Colquhoun was a small boy and was promised a boat by a postman to whom he gave a penny a week, but the boat never came. This is a rather far-fetched attempt to analyse Colquhoun’s statement, “I have felt the pangs of disappointment since…” Of course, Colquhoun hoped that Mashonaland would turn out to be a second Rand – everyone did, this is what most of the Pioneers hoped for and of course they were disappointed when the quartz deposits turned out to be low-grade and requiring crushing machinery to process that had to be brought from Kimberley 800 miles (1,290 kms) away by ox-wagon. There is no evidence that he suffered any long-term depression as a result.

Edwards then cites Colquhoun’s ‘lack of imagination’ because he previously turned down an invitation from Henry Morgan Stanley to be his second in command in the Congo expedition. In Dan to Beersheba, Colquhoun states that Stanley already had a history and reputation for treating expedition members badly. It was probably a wise decision.

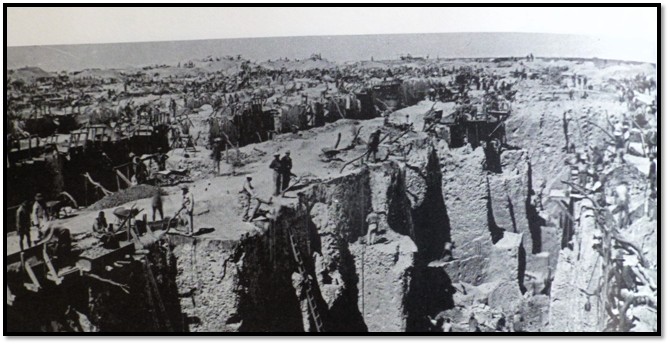

He then states most photographs show Colquhoun on the ‘fringe of any group photograph,’ concluding he is touched by doubt and hesitation and never strays far from his ‘instructions.’ The Memorandum of Instructions from Rhodes gives his role as ‘the administration of Mashonaland’ and to ‘carry on the administration.’ However the financial woes of the B.S.A. Co. when the mining revenues proved to be a mere trickle precluded any sufficient support whilst the administration demands were very great. Rhodes remembered the chaos over claims that had occurred at the Kimberley’s diamond pipes in their early days and was very anxious that the Mashonaland gold claims were properly surveyed and monitored – this required Mining Commissioners in the districts and administration systems in place – as already stated, the B.S.A. Co. resources were inadequate for the task.

Early days at Kimberley Diamond Mine – the chaotic and dangerous claims state that Rhodes wished to avoid in Mashonaland

Edwards states he was more of a ‘spectator than a participant.’ This seems unlikely; he had after all travelled through Southern China and extensively in Burma. Colquhoun successfully negotiated the treaty with Mutasa; it is clear that Jameson decided to negotiate the Gaza treaty with Gungunyana himself and elbowed Colquhoun out of the role.

Colquhoun’s life after Mashonaland

He visited the United States in 1893 and Central America in 1895 to visit Nicaragua and the proposed Panama Canal route. In 1896 he returned to China and was involved in railway negotiations. In 1898 and 1899 he travelled through Siberia, Eastern Mongolia, and China from north to south.

In 1900, he married Ethel Maud (née Cookson) who after his death remarried John Towse Jollie. Until his death, Archibald Colquhoun continued to travel widely publishing his views and reading a number of papers

before the Royal Colonial Institute, the Geographical Society, the Society of Arts, and the United Service Institution and spent much of the rest of his life traveling.

In 1900-1901, he and Ethel travelled in the Pacific -- the Dutch East Indies, Borneo, Philippines, Japan -returning to England via Siberia. From 1902 to 1903, they visited the West Indies, Central America and the United Stated, and South Africa and Rhodesia in 1904 and 1905.

In 1913 he again inspected construction work on the Panama Canal on behalf of the Royal Colonial Institute before his death on 18 December 1914.

Archibald R. Colquhoun Ethel Maud Colquhoun in 1907, after his

death she married John Towse Jollie

Conclusion

It appears that Colquhoun’s alleged failure was brought about by the deficiency of the B.S.A. Co’s administrative facilities resulting from its poor financial circumstances, rather than any personal flaws – the Chartered Company was after all a commercial company reliant on earning revenues, rather than a civil government with a broad base of taxpayers for support. This policy resulted from the UK government wishing to colonise on the cheap.

No individual could successfully administer a large area such as Mashonaland with such limited means and in this sense, both Colquhoun and Jameson were both given Sisyphean tasks that could never be successfully completed, although Colquhoun has been judged by history far more harshly than Jameson. It seems clear that Jameson, with Rhodes’ connivance, probably did deliberately undermine Colquhoun’s authority.

Some of Colquhoun’s insights into Cecil Rhodes

During his six months at Kimberley, Colquhoun was often in Rhodes presence and gained some useful insights into Rhodes, the man. “He was not a Sunday-school hero any more than he was a jingo Imperialist. He worked hard; lived hard. His real friendships were few. Probably he cared more for his early friend Pickering (who died young) than for any other human being, and after him he had a sincere affection for Jameson. In his later years he had a young protégé, a South African, to whom also he was much attached. [Jack Grimmer]

Because there were few decent houses in Kimberley at the time, Rhodes shared a tin-roofed shanty with Jameson, just opposite the Kimberley Club; Colquhoun shared a similar place with three other companions, including Otto Beit. Colquhoun says the offices of the Chartered Company were just a couple of rooms in the De Beers Building and they all messed at the Kimberley Club, where Rhodes had his own table, to which only his intimates were invited. The Club was, at the time, “stuffed with money” – more millionaires to the square foot than any other place in the world (Johannesburg had not yet arrived) Rhodes habit was to go horse-riding in the morning whenever he could.

Rhodes was careless about his dress. “I think at this time he was the worst-dressed man I have ever seen. His old veld hat was battered and dirty; his trousers bagged at the knees and his coats at the pockets…When entertaining guests at Groot Schuur he never went up to dress until the first carriage was heard driving up and five or six minutes sufficed for his toilet.”

Once or twice during his period of office work at Kimberley when Rhodes was afraid his financial backers were going to fail him, his language became lurid, and he was at times subject to fits of rage in which he let himself go.

The Cape to Cairo concept was not Rhodes’ original idea. The phrase was coined by Sir Charles Metcalfe, the railway engineer and Ricarde Siever in the Fortnightly Review of 1888 before Rhodes had given it serious consideration. But Rhodes, once his interest had been aroused, strongly supported the project to gain popular support for his northern expansion.

Books and articles written by A.R. Colquhoun

Across Chryse: Being the narrative of a journey of exploration through the south China borderlands,

from Canton to Mandalay. London: S. Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington, 1883.

The opening of China: Six letters reprinted from The Times on the present condition and future

prospects of China. London: Field and Tuer, 1884.

The truth about Tonquin: as The Times special correspondence. London: Field and Tuer, 1884.

A sketch of Formosa with J.H. Stewart-Lockhart. The China Review 13 (1885): 161-207.

Burma and the Burmans: or "The best unopened market in the world". London: Field and Tuer, 1885.

English policy in the Far East: as The Times special correspondence. London: Field and Tuer, 1885.

Amongst the Shans with H. Hallett and A. Terrien de Lacouperie. London: Field and Tuer, 1885.

The physical geography and trade of Formosa. Scottish Geographical Magazine (Edinburgh) 3 (1887): 567-77.

Matabeleland, the war, and our position in South Africa. The Leadenhall Press Ltd, 1894

The key of the Pacific: the Nicaragua canal. A. Constable and Co, 1895

China in transformation. Harper and Brothers, 1898

The renascence of South Africa. Hurst and Blackett Ltd, 1900

The mastery of the Pacific. The Macmillan Company, 1902

The Afrikander Land. J. Murray, 1906

References

C. Ash. The If Man. 30° South Publishers (Pty) Ltd, 2012

R.S. Burrett. Lomagundi Genesis. Heritage of Zimbabwe Publication No 12, 1993, P39-60

I.D. Colvin. The Life of Jameson Vol I and II. Edward Arnold and Co, London, 1923

J.A. Edwards. Colquhoun in Mashonaland, A Portrait of Failure, P1 – 17. Rhodesiana Publication No 9, December 1963

J.S. Galbraith. Crown and Charter. The Early years of the British South Africa Company. University of California Press, 1974

A.S. Hickman. Men who made Rhodesia. The British South Africa Company, Salisbury 1960

F. Johnson. Great Days. Books of Rhodesia, Vol 24, Bulawayo, 1972

A.G. Leonard. How we made Rhodesia, Vol 38. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo, 1973

H. Marshall Hole. Old Rhodesian Days. Books of Rhodesia, Siver Series, Vol 8, Bulawayo 1976

H. Marshall Hole. The Passing of the Black Kings. Books of Rhodesia, Siver Series, Vol 20, Bulawayo 1978

R.I. Rotberg. The Founder: Cecil Rhodes and the Pursuit of Power. Oxford University Press, 1988

M.R. Tucker. The Pink Map; how credible were Portuguese claims to Mashonaland and Manicaland before 1890? Heritage of Zimbabwe Publication No 39, 2020, P139 - 154

M.R. Tucker. Henry James Borrow (1865 – 1893) after whom Borrowdale is named. Heritage of Zimbabwe Publication No 38, 2019, P133 – 162

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: