The Pink Map; how credible were Portuguese claims to Mashonaland and Manicaland before 1890?

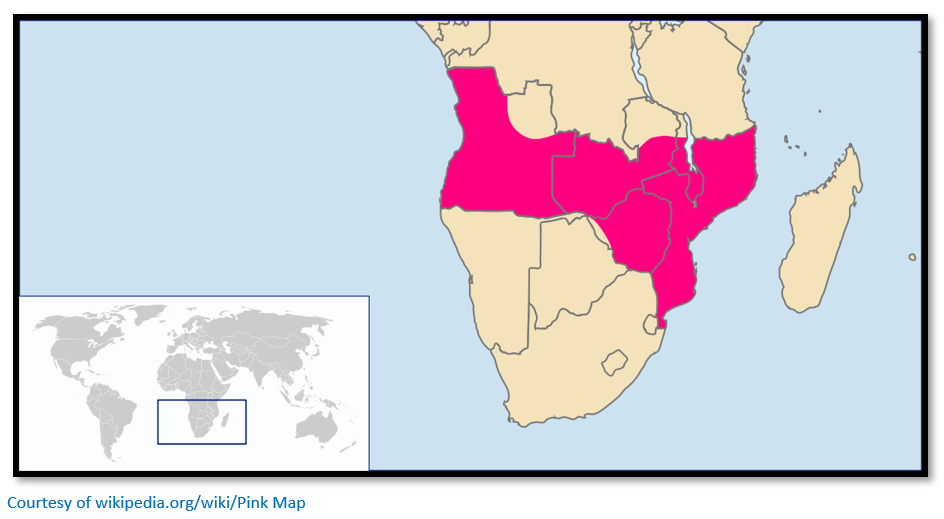

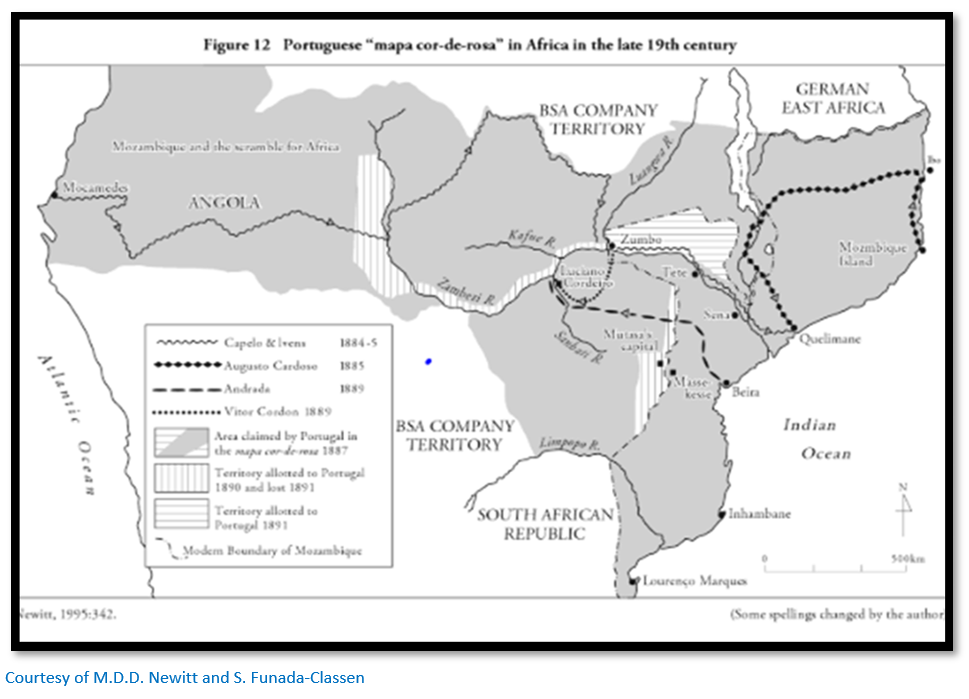

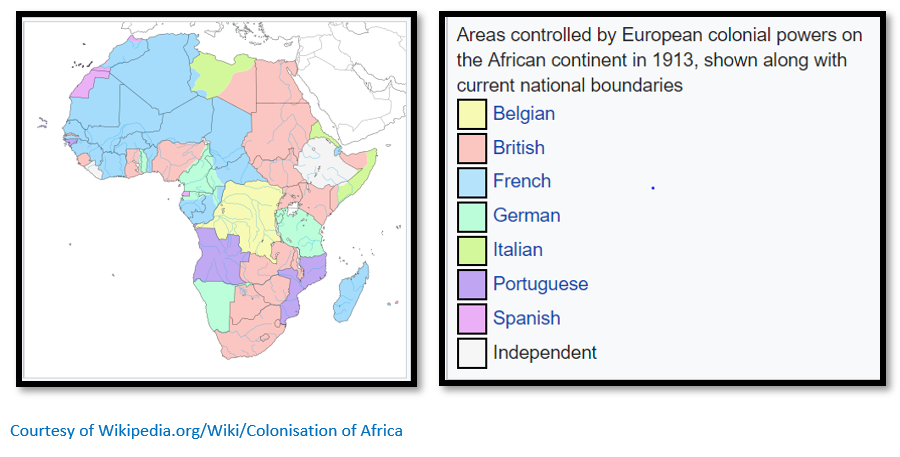

Reality is described as the state of things as they actually exist, as opposed to an idealistic or notional idea of them and this article examines the extent to which The Pink Map (Portuguese: Mapa cor-de-rosa) or Rose-Coloured Map of 1885 represented Portugal’s claim of sovereignty over the land corridor connecting their colonies of Angola and Mozambique during the period commonly known as the ‘Scramble for Africa.’ i.e. their territorial claims to present-day Zambia, Zimbabwe and Malawi.

Portuguese claims to territories in 1800

In Angola Portuguese effective influence extended to the coastal areas around Benguela, Luanda and Ambriz. In Mozambique the Portuguese had concluded a commercial treaty with the Ruler of Sofala in 1502 and subsequently forts were built at Mozambique Island, Ibo and Sofala and trading stations at Quelimane, Inhambane and Delagoa Bay on the coast and Sena and Tete on the Zambezi River.

Prior to the arrival of the Portuguese commercial activities had been conducted by Somali traders with indigenous peoples and the principal export was gold through Sofala from the hinterland…subsequently slaves were exported to the sugar plantations of Mauritius and Réunion and later to Brazil; when the slave trade declined after 1830 the ivory trade grew in its place.

Portuguese rule suffered during the 1830’s Mfecane with Lourenço Marques and Sofala destroyed in 1833 and 1835, Zumbo on the Zambezi River bordering Zambia was abandoned in 1836 and Sena was forces to pay tribute to the Gaza Empire under Shosangane.

Portugal introduced the Prazo system of large leased estates under nominal Portuguese rule; in reality local warlords established fortified strongholds and used private armies to raid for slaves in the interior. The most powerful of these warlords was Manual Antonio de Sousa, also known as Gouveia, a settler from Goa, who by the middle of the 19th century controlled most of the southern Zambezi Valley and a huge swath of land to its south. To the north of the Zambezi River, Islamic slave traders rose to power from their base in Angoche and to the south along the Shire River Yao Chiefs were the dominant power.

In the interior of Mozambique for long periods there was not even a pretence of Portuguese control from the period when Shosangane created his Gaza Empire in the 1830’s until his death in 1856. Only a succession struggle between his sons Mawewe and Mzila gave the Portuguese the excuse to intervene and back Mzila in 1861.

In addition to trading with the interior, the Portuguese hoped to establish a route connecting their territories of Angola in the west and Mocambique in the east and sent the following expeditions to Kazembe, near Lake Mweru in present-day Zambia;

- 1796 Manuel Caetano Pereira, a merchant.

- 1798 Francisco Jose de Lacerda e Almeida, a Portuguese officer arrived via Tete and died within a few weeks of arriving at Kazembe's whilst waiting for trade negotiations to start. His journal was carried back to Tete by his chaplain, Father Pinto, and later translated into English by the explorer Sir Richard Burton.

- 1802 Pedro João Baptista and Amaro José, pombeiros (slave traders).

- 1831 Major José Monteiro and António Gamito, with 20 soldiers and 120 slaves as porters, were sent by the Portuguese Governor of Sena district. Gamito wrote in his journal: "We certainly never expected to find so much ceremonial, pomp, and ostentation in the potentate of a region so remote from the sea coast."

As trade missions, though, they were failures as their efforts to set up an alliance which would control the Atlantic-Indian Ocean trade route from beginning to end were all rejected by local Chiefs.

Portuguese African possessions in the late 1860’s

In reality the Portuguese had no effective presence within the area between Angola and Mozambique and only a limited presence within those territories at the time.

Portuguese presence in present-day Zimbabwe

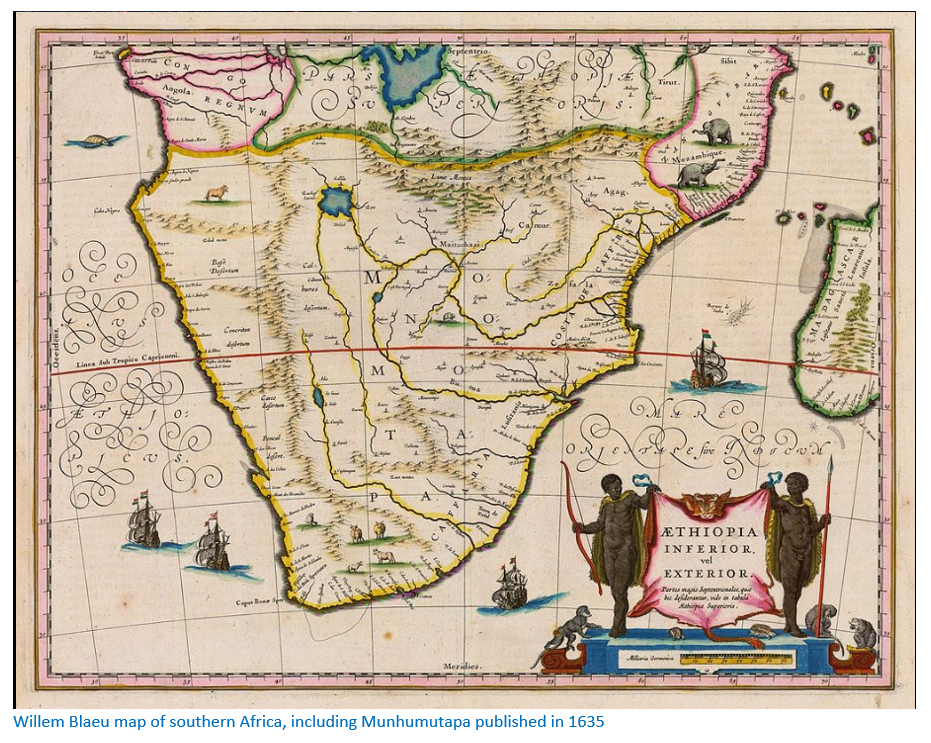

The Portuguese explorer Pêro da Covilhã is the first European known to have visited Sofala in 1489. His report highlighted the gold trade which had enriched its Somali traders and propelled Sofala from a small trading post into one of the leading towns on the east African coast in the twelfth century. His reports on the gold trade with the interior, now in a state of decline, finally led in 1502 to Vasco da Gama bringing the first Portuguese ships into Sofala harbour.

The Busi river route connected Sofala to the town of Manica and to the adjoining goldfields in present-day Zimbabwe. The Portuguese established at Sofala a factory (feitorias) which served as a market and warehouse and was governed by a feitor ("factor") who was responsible for managing the trade, buying and trading products and collecting taxes on behalf of the King and in 1505 constructed Fort São Caetano, the second Portuguese fort in East Africa after Kilwa.

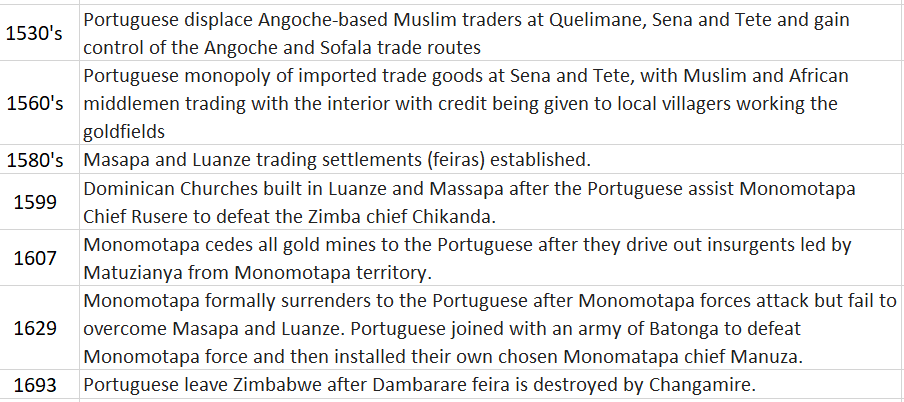

Very gradually the Portuguese explored the interior as this summary timeline indicates:

The Portuguese gained a wide-spread presence on the goldfields of Mashonaland at Angwa, Dambarare (at Mazowe) Piringani, Luanze, Maramuca (near Chegutu) Massapa. [Luanze and Maramuca are described on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] There are other feira sites including Bocuto and Matafuna which have not yet been traced.

Stan Mudenge argues that agriculture and cattle formed the economic base of the Mutapa Empire, but that gold and ivory played an important subsidiary role. Gold mining was both alluvial and through gold-reef mining – the only limits to depth being haulage, ventilation and the water table and this influenced when mining took place during the dry season months of August – October before the rains commenced in November. From then until April the miners became farmers and were involved in planting, weeding and harvesting their crops.

Until the Portuguese traders established their feiras [market-places] they were forced to send Vashambadzi – sometimes their children of mixed marriage to local women to buy up the gold from the villagers as the quantities mined were quite small and did not justify the journey to Tete.

Challenges to Portuguese African possessions

Increasingly European and local powers began to take an interest in Portugal’s African possessions. The Boers in the Transvaal Republic claimed an outlet to the Indian Ocean at Delagoa Bay in 1868 which was settled in the following year in favour of Portugal. Britain then made a claim which was rejected after arbitration by President MacMahon of France in 1875.

In present-day Malawi which had been explored by David Livingstone in the 1850’s a Church of Scotland mission was founded at Blantyre in 1876 and two years later the African Lakes Company was established.

Portuguese efforts to counter European territorial expansion

The Portuguese were suspicious of European explorers who often held consular positions and might claim the territory they explored for their own nations. To counter this threat The Lisbon Geographical Society and the Portuguese Government created a joint commission in 1875 to organise scientific expeditions between Angola and Mozambique.

Alexandre Alberto da Rocha de Serpa Pinto (1846 – 1900)

Alexandre de Serpa Pinto led three expeditions through which Portugal hoped to assert its African territorial claims. The first in 1869 was from the Island of Mozambique to the Zambezi Valley; the second in 1876 from Benguela in Angola to the river basins of the Congo and upper Zambezi and the last in 1877–79 crossing Africa from Angola, with the intention of claiming the area between it and Mozambique.

The last expedition with Lieutenant Commander Capelo and Lieutenant Ivens, both of the Portuguese navy, was from Benguela in November 1877. They parted company at Bie: Capello and Ivens turning north where they emerged at Dondo, on the Cuanza river in northern Angola. Serpa Pinto continued eastward, gradually changing course to the south. He crossed the Cuando river in June 1878 and in August reached Lealui, the Barotse capital on the Zambezi where assistance from the missionary Francois Coillard enabled him to continue his journey along the Zambezi to the Victoria Falls. He then turned south and arrived at Pretoria in the Transvaal Republic on February 12, 1879. Serpa Pinto was the fourth explorer to cross Africa from west to east.

Portuguese discussions with Britain

Whilst these expeditions took place the Portuguese attempted treaty discussions with Britain with the aim of obtaining a treaty of navigation on the Congo and Zambezi rivers and in 1879 claimed the area south and east of the Ruo River on the present south-eastern border of Malawi. By 1884 there was a draft treaty in place but was never ratified as negotiations ended with the Berlin Conference of 1884 – 5.

Berlin Conference of 1884 – 5

The articles of the Berlin Conference required that a nation must effectively occupy any areas claimed rather than simply relying on historical claims based on early discovery, or on simple exploration expeditions. Article 35 of the Act required the power claiming rights to have sufficient authority to protect existing rights and the freedom of trade i.e. an operating administration with policing powers.

This clause, the so-called clause of ‘effective occupation’, was important because it threw out historical claims based on priority of discovery and travel, the principle hitherto used by the Portuguese to account for their rights in Africa. This effectively ruled out Portugal’s claims to the area between Angola and Mozambique.

This contemporary view was endorsed in 1884 by Henry O’Neill, the British Consul on Mozambique Island: "Portugal has been a colonising power only in name. To speak of Portuguese colonies in East Africa is to speak of a mere fiction—a fiction colourably sustained by a few scattered seaboard settlements, beyond whose narrow littoral and local limits colonisation and government have no existence. Had Portuguese rule in East Africa shown any sort of vitality or reality no one cherishing any regard for international amity could have any fair plea to desire its displacement. By the ordinary rules of conquest and occupation Portugal has a title to possession sanctioned by three centuries of existence. But the very fact that for 300 years the flag of Portugal has waved along the East Coast involves the condemnation of Portuguese rule. For what is there to show for it? What use has Portugal made of her acquisitions or opportunities? What effect has she produced upon the destinies of the Continent? What part has she played? What contribution has she made to the sum of the world's progress, to the cause of civilisation to the well-being of mankind? The answer to these questions is writ in characters of miserable failure.”

The Portuguese response

Plans were made to form The Company of Mozambique (Companhia de Moçambique SARL) with the aim of administering and developing its territories on the east coast and later to neutralize the influence of the British South Africa Company (BSACo) and in 1884 Joaquim Carlos Paiva de Andrada was given four tasks:

- To establish Beira and the Portuguese occupation of much of Sofala Province.

- To acquire a concession and establish a trading post at Zumbo, which could be occupied by Afro-Portuguese families.

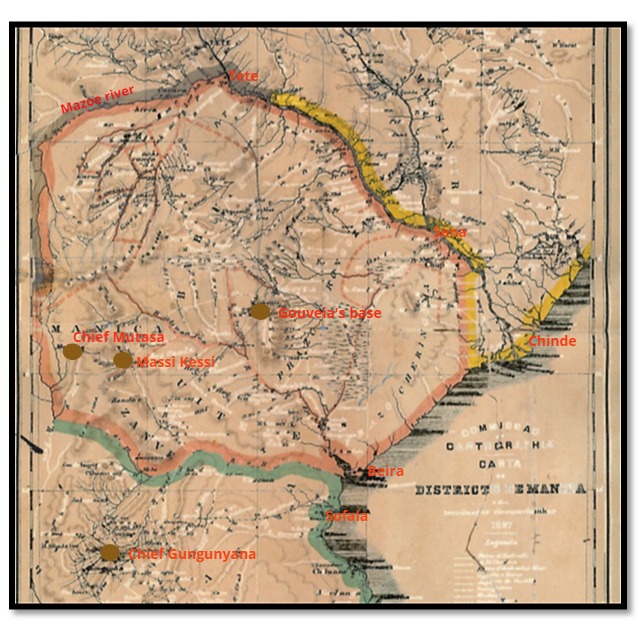

- To acquire a concession over Manica including the present-day areas of Manicaland - he concluded a treaty in 1889 with Chief Mutasa covering present-day Manicaland and established a basic administration with its base at Macequece (Massi-Kessi) but he was arrested in November 1890 by British South Africa Company troops and expelled.

- Also in 1889, Andrada crossed into northern Mashonaland to obtain additional treaties with local chiefs but the Portuguese government was not informed and they were not formally notified to other powers, as required by the Berlin Treaty.

The concession covered the central part of Mozambique i.e. Manica and Sofala from 1891 until 1941 (extended to include south of the Save River in 1893) when its 50 years (prolonged from 25 years in 1897) Charter expired. The Company had special trading privileges and the authority to collect revenue and taxes and issue stamps; in return infrastructure was to be constructed including railways, public services provided and a fee paid to Portugal.

In 1884 Serpa Pinto was appointed Portugal’s consul in Zanzibar in 1884, with the mission to explore the region east from Lake Nyasa and from the Rovuma River, the present-day border between Tanzania and Mozambique and the Zambezi River. However his attempts at treaty-making with local chiefs resulted in failure.

To further bolster their territorial claims the Portuguese Foreign Minister, Barros Gomes, issued in 1885 the Pink Map or Rose-coloured Map. In response to French recognition of the Pink Map Portugal gave up any claims to the area around the Casamance River in Guinea; for German recognition Portugal agreed to accept a southern boundary for Angola and a northern boundary for Mozambique. The acts of "noting" the Portuguese claims and attaching the Rose-Coloured Map to each treaty did not mean that France or Germany accepted Portugal’s territorial claims, only that Portugal had made them.

German-Portuguese Convention of 1886

The loss of the Portuguese claims to the Congo at the Berlin Conference was blamed on a loss of British support, but a year later Germany recognised Portugal’s claims on The Pink Map, although Britain was kept in the dark on this subject for several months. However after the Anglo-German boundary agreement on Africa in June 1890 Portugal lost any hope of further German support.

The above map produced in 1887 marks Manica District (in red) stretching as far inland as the Mazowe river; the Tete district is marked west of the Mazowe river showing that the Portuguese as late as 1887 regarded Manicaland and Mashonaland as part of their territorial possessions.

Negotiations with Britain

Lord Salisbury who was Foreign Secretary 1878 – 1890, stated Britain would not accept any Portuguese territorial claims unless sufficient Portuguese forces were present to maintain order. He formally protested against the Pink Map but made no claim against any of the territories it covered.

Britain protested for two main reasons. Firstly, Portuguese claims in Nyasaland were an obstacle to the activities of the Scottish missionaries who had followed David Livingstone and settled in the area in 1875. Secondly, it threatened Cecil Rhodes' policy of expansion through the BSACo and the establishment of a British sphere of influence stretching from Cape to Cairo.

The British Minister in Lisbon proposed that the Zambesi River be recognised as the northern limit of British influence…this left the Scottish missions in present-day Malawi within Portuguese territory and would have left Portuguese territory connecting Angola and Mozambique, although it would be much narrower than that shown on the Pink Map. This proposal was rejected by Portugal as they believed the area now comprising northern Mashonaland contained more resources such as gold and ivory than previously thought and should be considered within their sphere of influence.

Portugal makes a counter-offer, then mounts two expeditions

In 1889 Portugal stated it would be willing to abandon its claim to the region between Angola and Mozambique in return for a claim on the Shire Highlands in present-day Malawi. The British Government now rejected this proposal after lobbying by the Scottish missions and because the Chinde River entrance had just been discovered allowing direct access to the Zambesi River and the Shire River and were thus considered international waterways.

Portugal tried to reinforce their claim by sending two expeditions to the area. The first under Antonio Cardoso, a former governor of Quelimane left in November 1888 for Lake Nyasa. The second expedition under Serpa Pinto travelled to the Shire valley and both men signed treaties with local chiefs. Harry Johnston, the British Commissioner and Consul-general for the Mozambique and the Nyasa districts advised Pinto in August 1889 not to cross the Ruo River into the Shire Highlands.

Anglo-Portuguese Crisis of December 1889

Johnston’s advice was ignored and on 8 November after Pinto’s forces were engaged in a minor skirmish with the Makololo tribe near the Shire River the Portuguese crossed the Ruo River into present-day Malawi.

In response Johnston's vice-consul, John Buchanan, accused Pinto of ignoring British interests and contrary to his instructions declared a British Protectorate over the Shire Highlands. In December 1889 and also contrary to instructions, Johnston declared a further protectorate over the area to the west of Lake Nyasa; both Protectorates were later recognised by the British Foreign Office.

The 1890 British Ultimatum followed by talks

Lord Salisbury sent an ultimatum to Portugal on 11 January 1890 demanding the withdrawal of the Portuguese troops from Mashona and Matabeleland and the Shire-Nyasa region (Malawi) where Portuguese and British interests in Africa overlapped. The text ran as follows: “What Her Majesty's Government require and insist upon is the following: that telegraphic instructions shall be sent to the governor of Mozambique at once to the effect that all and any Portuguese military forces which are actually on the Shire, or in the Makololo, or in the Mashona territory are to be withdrawn. Her Majesty's Government considers that without this the assurances given by the Portuguese Government are illusory.

Mr. Petre [the English Minister in Lisbon] is compelled by his instruction to leave Lisbon at once with all the members of his legation unless a satisfactory answer to this foregoing intimation is received by him in, the course of this evening, and Her Majesty's ship Enchantress is now at Vigo waiting for his orders.”

The Fortnightly Review in an article entitled “Portugal’s Aggression and England’s Duty” urged the British government to seize Delagoa Bay and the African Lakes Company directors supported a no compromise position. These areas had been nominally claimed by Portugal since the sixteenth century. Talks started in Lisbon in April 1890, and in May the Portuguese delegation proposed an Anglo-Portuguese joint administration of the disputed area between Angola and Mozambique. The British government refused to agree and drafted a treaty that imposed boundaries that were generally disadvantageous to Portugal.

The views of Rhodes and the British South Africa Company

The BSACo had been formed in October 1888 and only received the Royal Charter permitting the company to trade with local chiefs, own and sell land and control its own police force a year later. From the outset Rhodes and the BSACo were opposed to Portuguese claims to Mashonaland and made no secret of their desire for direct land access to the Indian Ocean. However Rhodes was not in favour of the treaty either and in a letter to the Foreign Office dated 23 September 1890 wrote: “I took the liberty of sending you a direct cable as to the Portuguese treaty in the hope that it was not too late to remedy the mischief that has been done. Now that the Portuguese Ministry has resigned I hope you will drop this wretched treaty, under which we get nothing and give away a great deal.” And he went on: “You have given away half the Barotse which has just been formally ceded to us… You have given away the whole of Gazaland. I have an agent now with the King and expect to hear daily of his accepting our flag… You have given away Manica. My people are now occupying and out of it. They will not go, and further they will not be ruled by a half-caste Portugee and I hope you will draw Lord Salisbury’s attention to this fact.” He also complained of “the brutal conduct of the Portuguese to their native subjects.” He concluded: “I can only add in conclusion that if you have any regard for the work I am doing you will show it by now dropping the Anglo-Portuguese agreement. I see nothing but trouble in the future if it is carried through, and I do not think I am claiming too much from your department in asking you to give some consideration to my views.”

In May 1890 the BSACo gave Rhodes “absolute discretion” as its managing director; in July he became prime minister of the Cape Colony – as Galbraith states, both offices gave him enormous power and he would not be prevented by his board of directors or from the Foreign Office. Additionally Britain would not make decisions on central Africa before consulting with its self-governing Cape Colony and this relationship provided an opportunity which Rhodes would exploit in every way.

European powers views of Portugal’s possessions in Africa

Countries such as Italy, Austria and Germany all understood Portugal’s plight, but none were prepared to offer more than words of sympathy. Their greatest concern were not Portugal’s African possessions, but that the fall of Portugal itself might also topple the Spanish monarchy.

British South Africa Company policy towards Mozambique was forthright

The BSACo considered that Portuguese claims to Manicaland and Mashonaland rested upon the flimsiest pretences; ancient treaties with the Mutapa Empire (Munhumutapa) and scattered trading settlements (feiras) which had been abandoned since their defeat in 1693. Furthermore that Portugal was on the verge of bankruptcy and could not support its colonial possessions. A BSACo Director, Albert Grey stated that their territory south of the Zambezi was: “bound by the eternal laws of gravitation to tumble into our lap” and Rhodes and the Directors were keen to assist the process. Rhodes’ view was even more forthright: “They are a bad race and have had 300 year on the coast and all that they have done is to be a curse to any place they have occupied.”

Rhodes believed in a free play of forces rather than diplomacy

After the June 1890 Anglo-German boundary agreement Rhodes believed that as long as the Foreign Office did not interfere the BSACo could occupy all the territory south of the Zambesi to the coast and if the Portuguese decided to fight they would lose all their possessions from Delagoa Bay to present-day Tanzania. Rhodes was not in favour of any international agreements which confirmed Portugal’s right to territory which he believed the Portuguese administration did not have the power to hold or the resources to develop.

However the BSACo directors were more cautious than Rhodes as they knew wars were costly and the company’s resources limited; it was felt important that Portugal be seen as the aggressors in any potential engagement.

Lord Salisbury’s views on Portugal’s colonial possessions

One of the quotes concerning Lord Salisbury, then combining the roles of Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary, was: “English policy is to float lazily downstream, occasionally putting out a diplomatic boathook to avoid collisions.” Salisbury expected the chartered companies to fall in with British policies, but Rhodes’ avowed intention to oust the Portuguese from Mozambique threatened international relationships. On 28 September the Duke of Abercorn wrote to George Cawston, both were BSACo Directors, that Salisbury; “apparently has had enough of Rhodes.” But the problem for the Foreign Office was that if Rhodes was irritated enough he might carry out the threat suggested in his speeches and lead South Africa out of the British Empire.

Salisbury had no wish to humiliate the Portuguese, but he was also not prepared to make concessions that might be interpreted as a climbdown. Thus Nyasa and the Shire Highlands and the recognition of the Zambesi and Pungwe rivers as international waterways were non-negotiable, but their right to Delagoa Bay and the coastline as far as present-day Tanzania was not disputed.

The situation in Manicaland and Gazaland

In the 1630’s the town of Chipangura, later Massi-Kessi or Macequece and now Manica, was the main gold market in Manicaland with Portuguese traders visiting and even settling in the town until it was sacked by the Rozvi army from present-day Zimbabwe in 1695. Thereafter the gold trade continued, but under the ascendancy of the Manica Kings.

By 1890 on the western side of the Manica mountains Chief Mutasa, who lived at the hill called Binga Guru, ruled over the Manica tribes. The BSACo hoped that if they could make an ally of Mutasa and demonstrate he was an independent chief, they could claim his territory through a treaty. The route along the Pungwe River to Beira would be much shorter and cheaper into Mashonaland than the route from the south so if Mutasa’s territories could be overstated as far as the coast, so much the better. In times past, Mutasa had declared his submission to either the Portuguese or Gungunyana, the chief of Gazaland, depending on who he believed held the greatest power. Now there was the competing challenge from the BSACo.

We have already seen that on Shoshangane’s death in 1856 his sons struggled for control of the Gaza Empire with the Portuguese intervening with arms and African levies and backing Mzila in 1861. Under Mzila’s successor Chief Gungunyana their power waned; Manuel António de Sousa (Gouveia) had forced the Gaza’s from the region between the Zambezi and Busi-Revue rivers and from the coast. Gungunyana had initially accepted Portuguese control, but by 1887 was contesting Portuguese claims over his territory.

As with Chief Mutasa, the independence of Chief Gungunyana was important for the BSACo as the Limpopo river which flowed through Gazaland might offer an alternative route into Mashonaland and his territory also contained goldfields.

George Cawston’s argument that Mutasa (Umtassa) and Gungunyana were independent chiefs

Cawston’s argument to the Foreign Office was to quote Selous stating that both chiefs had large standing armies and as independent chiefs desired friendship treaties with Britain. Their recognition as independent chiefs was a cynical ploy described by the BSACo director Albert Grey: “Let Gungunyana and Umtassa be the declared sovereigns. We can pull the wires from behind the curtain. They pose before the civilised world as independent chiefs and nobody can complain if they choose to use their independence in a way that is pleasing to us.”

The role of Archibald Colquhoun, Administrator of Mashonaland

In an article in Rhodesiana Publication No 9 on A.R. Colquhoun, J.A. Edwards quotes the memorandum of instructions given by Rhodes to Colquhoun on 13 May 1890 in which para 4 states: “As soon as practicable after entering Mashonaland, you will, accompanied by Mr Colenbrander (as Interpreter) and a small escort of Police, should you think it advisable to take them, visit the Chief of the Manica country, and obtain from him on behalf of the Company, a treaty and concessions for the mineral and other rights in his territory…You will endeavour to achieve the right of communication with the sea-board, reporting on the best line of railway connection with the littoral from Mashonaland…On returning from Mashonaland, for the purpose of taking over charge of the Administration, you will, if advisable, leave a representative with the Manica Chief.”

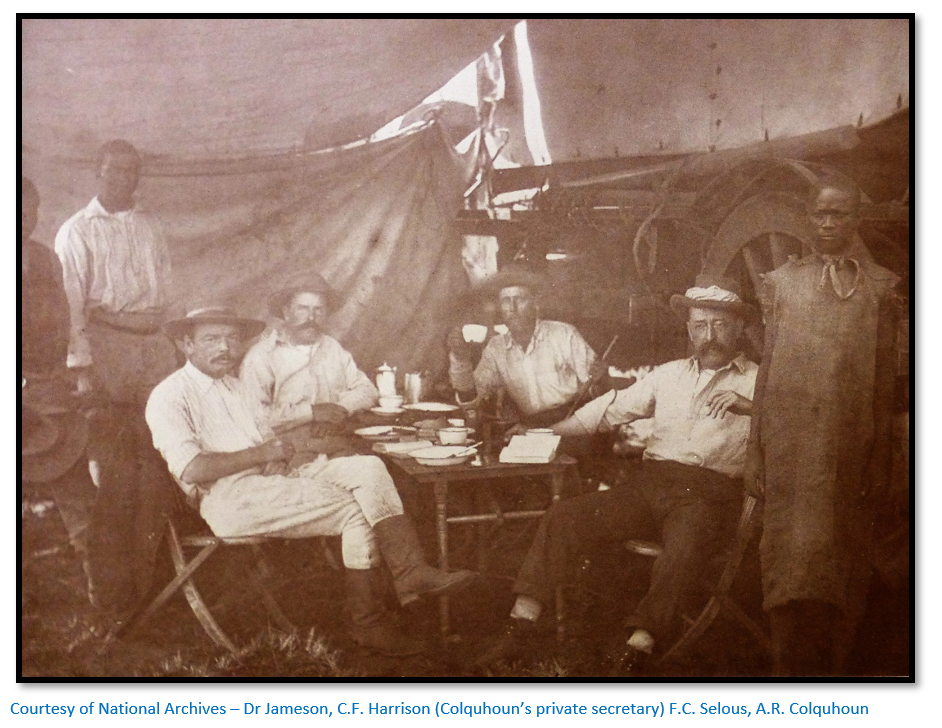

Acting on his instructions, on 26 August 1890 A.R. Colquhoun left the Pioneer Column on with C.F. Harrison, his private secretary, F.C. Selous and Dr Jameson and an escort of fifteen police under Lieut. Adair Campbell but returned within a few days and set off again on 3 September with a reduced escort of seven police and without Jameson who was injured in a fall from his horse. The party re-joined the Column having made a treaty with Chief Mutasa on 14 September who declared that he looked upon the BSACo to liberate him from Portuguese threats and intimidation. For £100 per year the BSACo was given exclusive mineral rights and other monopolies to the area under his authority.

As soon as 21 September Colquhoun wrote to Rutherford Harris, the BSACo secretary: “Upon my return to Mount Hampden I propose warning Major Johnson and Dr Jameson against adopting the Manica and Massi Kessi route on their return to Cape Town, deeming that route, at the present time, both unsafe for them personally, as well as inexpedient in the interests of the Company.”

This view was ignored by Johnson and Jameson and so Colquhoun wrote again to Harris on 4 October: “I thought it very inexpedient in the interests of the Company, that Johnson should go out via Manika until matters were quite settled there and I know from you that you held the same view. This view was strengthened after my visit to Manika and after the execution of the treaty [with Chief Mutasa] especially as the earlier situation was complicated by the Portuguese being in a state of intense irritation, not likely to become less after the Anglo-Portuguese agreement.”

But Colquhoun to his intense surprise soon learned from Harris that: “Rhodes would like Johnson to go through to Pungwe unless there are very strong objections to it…” Rhodes was once more prepared to change his views when the situation required it.

The situation on the ground in Manicaland in September 1890

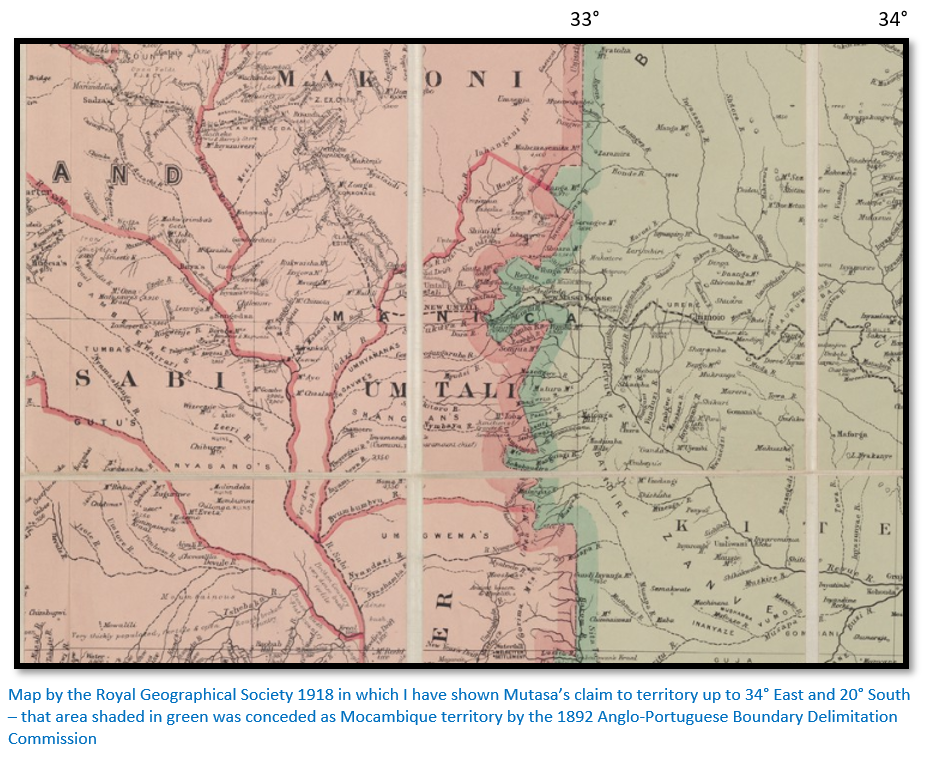

The BSACo’s hopes that Chief Mutasa’s would lay claim to vast stretches of Mocambique were not realised; the territory he claimed extended to 34° East and 20° South and even this area contained the base of The Company of Mozambique at Macequece occupied by its officials. In addition prospectors and miners were at work under licence from The Company de Mozambique at Penhalonga. In 1888 Baron de Rezende, Director of Operations for The Company of Mozambique had engaged James Jeffreys, a British mining engineer, to prospect in the area of “the divide” and Jeffrey had pegged claims on the future Rezende, Bartissol and Penhalonga goldmines. [see the article on Penhalonga under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

In addition, Chief Mutasa then secretly informed the Portuguese at Macequece that he had only signed the treaty under duress. This however is the subject of another article on the website www.zimfieldguide.com entitled ‘How Mutare and Manicaland were seized from the Portuguese.’

Anger in Portugal and Portuguese public reaction

After centuries of lethargy Africa suddenly became a focus of attention for Portugal. The Berlin Conference of 1884 – 5 had stripped away Portugal’s claims to the Congo, but the German-Portuguese convention of 1886 recognised their claim to the territories on The Pink Map and violent anti-British demonstrations broke out in Portugal when the draft treaty was published by Britain following the April 1890 Lisbon talks. Its’ terms aroused violent anti-British sentiments all over Portugal, demonstrations were held, the British consulate stoned and economic sanctions against Britain were demanded. The Portuguese press and literature echoed and stimulated the reaction against Britain. Journalists, poets, novelists, students and the public in general protested violently against what they saw as an outrage against Portugal’s claims in Africa.

The Guardian newspaper wrote on 19 February 1890: “No Englishman, however, farsighted, probably foresaw the storm which this Lake Nyassa dispute has aroused in Portugal. It may perhaps be traced to three causes – to the excitable character of a Southern people; to self-reproach felt by the Portuguese for their prolonged neglect of splendid colonial opportunities; and lastly... to Republican intrigues.”

The Modus Vivendi of 14 November 1890

Since the treaty of August was rejected, an agreement was reached according to which there would be a standstill in Anglo-Portuguese negotiations, the so-called Modus Vivendi and was negotiated by the Marquis of Soveral, the Portuguese Minister in London, and signed on 14 November 1890. This recognised the Scottish missions rights in the Shire Highlands, and Portugal’s territorial claims to Gazaland and most of Manicaland east of 33°. Portugal agreed not to accede any land south of the Zambesi river; the Zambesi, Shire and Pungwe rivers were declared international waterways and several acres of land at Chinde, at the mouth of the Zambesi, were leased to Britain and Portugal committed to building a railway from Fontesvilla on the Pungwe to the BSACo’s border.

BSACo intransigence continues

When Lord Salisbury heard that the BSACo was planning to move into territory designated Portuguese he told Sir Henry Loch, the High Commissioner for Southern Africa that Britain would not recognise any such acquisitions. Rhodes however continued with his strategy of recognising the independence of Chiefs Mutasa and Gungunyana and declared the BSACo would send its forces to defend them against Portuguese attack. Rutherford Harris, the mouthpiece for Rhodes said that Britain should not thwart: “the rightful development of the English race in south Zambesia, out of respect to such a slave-raiding, gin-drinking set of scoundrels as the Portuguese.”

Treaty of Lisbon on 11 June 1891

New treaty negotiations began after the battle of Macequece and Chua Hills between the BSACo and the Portuguese which agreed a compromise. The borders of Angola were fixed, freedom of navigation was confirmed on the Shire, Zambesi and Pungwe rivers and Portugal was given more territory in the Zambesi Valley in exchange for giving up land in Manicaland. This treaty established the borders which exist today of present-day Zimbabwe and Mozambique. Portugal gained no rights to the north bank of the Zambesi, thus ending any claim to the region between Angola and Mozambique as outlined on the Pink Map.

Rhodes could never be satisfied with anything less than the occupation of Beira, but the other BSACo directors were satisfied providing the Portuguese could be held to their promise to build a railway and negotiation would henceforth be decided not by action, but by negotiation.

References

Wikipedia: Pink Map

M.D.D. Newitt. A History of Mozambique. Indiana University Press 1995

Joaquim Carlos Paiva de Andrada. Relatorio de uma viagem ás terras dos Landins

www.filatelia.fi/articles/mozambique.

Teresa Pinto Coelho, (2006). Lord Salisbury's 1890 Ultimatum to Portugal and Anglo-Portuguese Relations, p. 2. http://www.mod-langs.ox.ac.uk/files/windsor/6_pintocoelho.pdf

S. Funada-Classen. The Origins of War in Mozambique. a History of Unity and Division. African Minds, 2013

S.I.G. Mudenge. A Political History of Munhumutapa c 1400 – 1902. Zimbabwe Publishing House 1988

J.S. Galbraith. Crown and Charter. The early years of the British South Africa Company. University of California. 1974

J.A. Edwards. Colquhoun in Mashonaland; A portrait of failure. Rhodesiana Publication No 9, December 1963