Land and the British South Africa Company - the Renny-Tailyour and Lippert concessions

The article Were Lobengula and the amaNdebele tricked by the Rudd Concession? under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com deals with the events leading up to Lobengula granting the above concessions. This article considers some of the consequences of the Rudd concession, the Renny-Tailyour concession and its successor the Lippert concession and their importance to the British South Africa Company (BSAC)

The Rennie-Tailyour concession article by Robert Cherer Smith in Heritage No 38 places the emphasis on the mining consequences of the concession; however Rhodes and the BSAC believed the real importance of the concessions lay in their conveying title to land rights, thus trumping the Rudd concession which related only to mineral rights.[i]

But first, we should examine the Rudd concession which preceded them.

The Rudd Concession forms the background to the Lippert concession

The details of the Rudd Concession are well-known to many readers; on 30 October 1888 King Lobengula [King of Matabeleland, Mashonaland and other adjoining territories] on behalf of the amaNdebele [in the presence and with the consent of my Council of Indunas] signed the Rudd Concession [This given under my hand the 30th day October in the Year of our Lord 1888, at my Royal Kraal]

The concession granted Charles Dunell Rudd, Rochfort Maguire and Francis Robert ‘Matabele’ Thompson [do hereby grant and design until the said grantees, their heirs, representatives and assigns, jointly and severally] the right to the minerals within his Kingdom [the complete and exclusive charge over all metals and minerals situated and contained in my Kingdoms, principalities, and dominions] and permitted them to import mining machinery [together with full power to do all things that they may deem necessary to win and procure the same] and enjoy the profits from the sale proceeds [and to hold, collect, and enjoy the profits and revenues, if any, derivable from the said metals and minerals]

Rudd, Maguire and Thompson agreed to pay Lobengula [the sum of 100 pound sterling, British currency, on the first day of every lunar month] and deliver at Gubulawayo [one thousand Martini-Henry Breech-loading Rifles, together with one hundred thousand rounds of suitable bull cartridge] plus [to deliver on the Zambezi River, a steamboat with guns suitable for defensive purposes upon the said river, or in lieu of the said steamboat, should I so select, to pay to me the sum of five hundred pounds sterling, British currency] Lobengula complained at the number of concession-seekers seeking mineral rights [I have been much molested of late by diverse persons seeking and desiring to obtain grants and concessions of land and mining rights in my territories] and gave Rudd, Maguire and Thompson the right to exclude competitors from his Kingdom [to take all necessary and lawful steps to exclude from my Kingdoms, principalities and dominions, all persons seeking land, metals, minerals, or mining rights therein, and I do hereby undertake to render them such needful assistance as they may, from time to time, require for the exclusion of such persons] and to give them exclusive rights to all the minerals [to grant no concessions of land or mining rights from and after this date without their consent and concurrence]

The only area excluded was the area of the Tati concession granted to Sir John Swinburne’s London and Limpopo Mining Company [nothing contained in these presents shall extend to, or affect a grant made by me of certain mining rights in a portion of my territory south of the Ramakoban river, which grant is commonly known as the Tati Concession]

Firstly, it is important to understand what the Rudd concession meant to the different parties.

Lobengula and the Rudd concession

To Lobengula the concession was granted to three specific persons, Rudd, Maguire and Thompson, and it gave them the right to the mineral resources which Lobengula hoped would have the following results:

- He hoped it would keep other concession-seekers at bay. These consisted of numerous individuals and syndicates, but the most significant parties seeking mineral concessions, other than Rhodes’ agents, were the Exploring Company headed by Lord Gifford and George Cawston and whose agent at the royal kraal of Umvutcha was Edward Maund and also Eduard Lippert represented by Renny-Tailyour.

- He believed Thompson who said that they, unlike the Boers from the Transvaal Republic, were not seeking land and would not overrun his country, they sought only the right to explore for minerals and to trade. For Lobengula and the izinDuna their most pressing concern was security of Matabeleland and they believed that whilst the Boers might be better fighters than the British, Britain was a greater power on the world stage. His envoys Babayane and Mshete who saw Queen Victoria with Edward Maund had impressed him with what they had seen in Britain, so he hoped Britain could reasonably be expected to protect him from the Boers.

- He believed John Moffat, the colonial office representative and Sir Sidney Shippard, who arrived soon after the Rudd party when they both stated that it was in his best interests to work with one large commercial organisation which was supported by Queen Victoria (i.e. the Rudd party representing Rhodes) and told Lobengula that events in Mashonaland would be easier for him to manage than if he had to deal with small-time prospectors and syndicates.

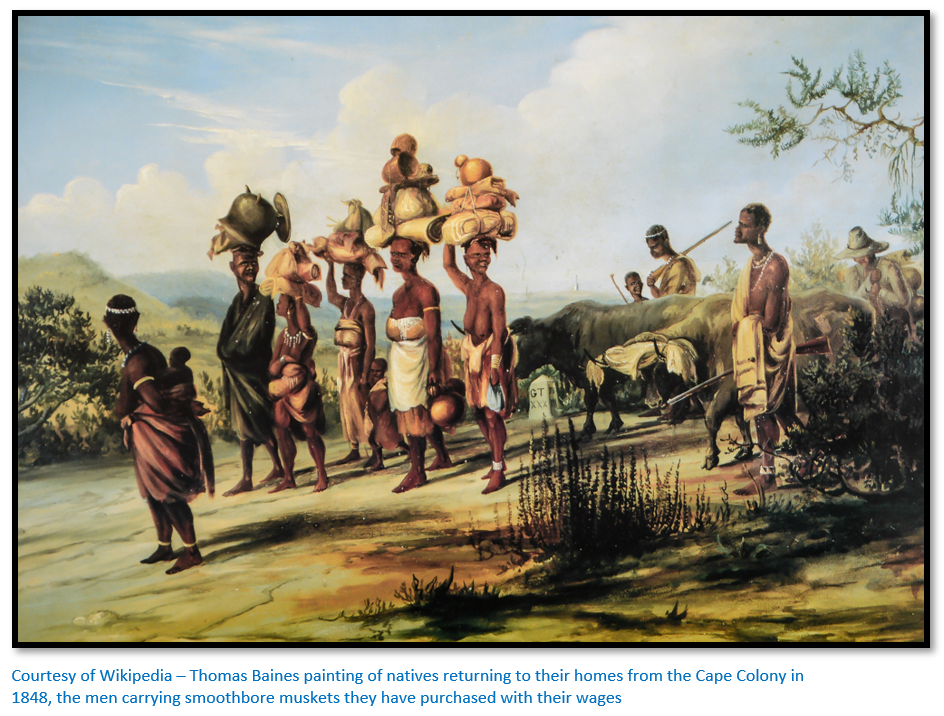

- Rudd’s offer for a concession was far more generous than any of his competitors could offer; particularly the 1,000 Martini-Henry breech-loading rifles, 100,000 rounds of matching ammunition, a steamboat on the Zambezi or, if Lobengula preferred, a lump sum of £500. There was also £100 per month, although that had little value to the amaNdebele who thought gold sovereigns were best suited for making bullets…guns and ammunition were what they really valued. Lobengula already had some smoothbores and muskets, but these rifles were the latest available.

Europeans and the Rudd concession

- They considered the Rudd concession was a legal commercial document owned by Rhodes’ company Gold Fields of South Africa - the rights of which could be transferred to the Central Search Association which was used to merge the interests of Gifford and Cawston’s Exploring Company with Rhodes and into which the Rudd concession was transferred on 23 May 1889 from Gold Fields of South Africa Ltd.

- Charles Helm, the missionary based at Hope Fountain Mission and Lobengula’s interpreter for the Rudd concession, stated that Rudd made oral promises to Lobengula that were not in the written document, including: "that they would not bring more than 10 white men to work in his country, that they would not dig anywhere near towns, etc., and that they and their people would abide by the laws of his country and in fact be his people." However none of these promises were included in the concession itself and neither Rhodes nor any of the officials of the BSAC felt they had any legal or moral obligation to stand by these statements, although Lobengula clearly thought they were part of the agreement.

In less than a year after amalgamating their interests in the Central Search Association the total share capital of this company of £121,000 was transferred into the United Concessions Company with the same shareholders, but with a greatly enlarged share capital of £4 million.

With the backing of a large commercial venture the colonial office could be approached for a royal charter that was granted to the British South Africa Company on 29 October 1889.

The Renny-Tailyour concession granted after the Pioneer Column reaches its destination

Edward Ramsey Renny-Tailyour was Eduard Lippert’s agent at Umvutcha in Matabeleland. Lippert was an estranged cousin of Alfred Beit - he held the controversial dynamite concessions in the Transvaal and helped Paul Kruger set up the National Bank and Netherlands South Africa Railway Company and procured arms from Germany for the Transvaal Republic.

Lippert had been attempting to gain a concession from Lobengula since early 1888 and on 4 April 1891 his agent Renny-Tailyour declared that he and Lobengula had completed an agreement which gave: “the sole and exclusive right and privilege for the full term of one hundred years, to lay out, grant, or lease, for such periods as he may think fit, farms, townships, building plots, and grazing areas, to impose and levy rents, licences and taxes, to get in, collect, and receive the same, to give and grant certificates in my name for the occupation of any farms, etc; to establish and to grant licences for the establishment of banks; to issue bank notes, to establish a mint…”[ii] in the territory of the BSAC in return for £1,000 up front and £500 annually.

Why Lobengula granted Renny-Tailyour a concession

The Rudd concession in stating [to grant no concessions of land or mining rights from and after this date without their consent and concurrence] prevented any future land concessions, but also gave no land rights to Rudd and his party.

So how did Renny-Tailyour, as the agent of Eduard Lippert, despite this clause in the Rudd concession, manage to persuade Lobengula to grant him the exclusive right for one hundred years to deal with all land in Mashonaland and Matabeleland?

This concession was undoubtably granted because Lobengula wished to avenge himself on Rhodes for subsequently gaining the upper hand with the Rudd concession. He had to face many accusations from concession-seekers at Gubulawayo who had a common interest in frustrating Rhodes’ party of Rudd, Maguire and Thompson. and from his own izinDuna that he had “sold the land” to the BSAC

The first adverse report in the Cape Newspapers was received in mid-January 1889 in a letter to Reilly, one of Renny-Tailyour’s party and Tainton translated it for the King saying it stated that the King: “had in fact sold his country and the grantees could if they so wished bring an armed force into the country, depose him and put another chief in his place; dig anywhere, in his kraals, gardens and towns.”[iii]

The King’s strategy had been to delay the evil day by dividing the white interests where he could, then giving a little to the whites whose overwhelming power he understood; at another time doing the same for his amaNdebele subjects who wished to drive the whites from Ndebele lands and constantly dawdling and delaying. It was Renny-Tailyour who reported that the Imbizo, Ingubo and Insuka regiments demanded to see the King on 11 June 1889 to ask if the he had sold his country for guns and that all the white men connected with the Rudd concession, including John Moffat the colonial office representative, were ordered away.

This letter from John Moffat to Thomas Leask on the subject of a minerals concession that Lobengula had signed on 14 July 1888 with Leask, Philips, Westbeech and Fairbairn explains the predicament that Lobengula found himself in:

Sanane River, 28 Nov 1888

“My Dear Mr Leask,

…I believe that the Chief Lobengula is fairly honest in intentions when he puts his name to an agreement, but I have come to see, especially lately that he is far from being a free agent. He has in fact behind him forces which he can ill control – and the jealous and suspicious nature of his fighting men aroused, any agreement of this sort made with white men would be of little account. The Chief is being much beset with applications. I have reason to believe that during the two months I have spent there, just now, at least five hundred pounds in gold has been given to him by different parties, in order merely to pave the way for concessions.

My advice to such as gave me an opportunity of offering advice was – let all combine and act on a settled plan – this advice was not taken and the result has been a most unsatisfactory clashing of interest and by such a mode of procedure certainly not forwarding their own, for the Chief is learning how to play one against another to pocket the proceeds with tolerable freedom from any responsibility – beyond a few fair words.”

Moffat continues with this theme: “…I believe that a great syndicate of which you may have heard is at work and is prepared to deal with the matter on an unprecedented scale and eventually if such a course should prove to be necessary, to protect his own interest; such seems to me the only feasible plan and I should like to see such a scheme carried out. Could not the interest represented by you be merged in this? I fancy it will be this or nothing.”

Moffat then assures Leask of his neutrality in these matters: “…The chief value of my position is that I am in no way connected with gold or other mercantile interests – and can give Lobengula advice entirely apart from personal considerations…”[iv]

Defects in the Renny-Tailyour concession

Other concession-seekers at Umvutcha disputed the authenticity of the concession saying on Lobengula’s side only izinDuna Mshete had signed the document and that Lobengula had believed the agreement was with "Offy" Shepstone, the son of Theophilus Shepstone, a British diplomat who had great influence over the Zulu people in Natal and was well-known to Lobengula. When Renny-Tailyour arrived in Matabeleland he had brought a letter from “Offy” then in Swaziland, with a friendly message from his uncle and the Swazi King – an old Swazi Induna, Silas Mdhluli, had accompanied him to Gubulawayo and these factors may have given Lobengula the impression they had official status.

Renny-Tailyour told Lobengula that the BSAC wanted his land; that he would contest the matter in Johannesburg after obtaining a general power of attorney which required the King’s signature. So he obtained two sheets of paper; one had the date, Lobengula’s elephant seal, Mshete’s mark as witness and the signatures of Renny-Tailyour, Acutt and Reilly, both of whom were Renny-Tailyour employees. The other supposedly had the agreement in draft form, but the contents were only known in Renny-Tailyour [v] who transferred the concession document to Eduard Lippert.

Lippert knew the biggest weakness the BSAC faced was its legal incapacity to transfer land title and sort to undermine the Rudd concession; however he also knew the colonial office would not tolerate a rival to the BSAC, so despite the potential defects in his concession, Lippert believed he had the upper hand and demanded from Rhodes £250,000 in cash or shares at par in the BSAC.

Oscar Dettelbach also receives a concession

The principal defect of the Rudd concession was that it only granted mining rights. Both Lippert through Renny-Tailyour and Dettelbach through his agent Hassforther – described by Marie Lippert as: “a horrible liar and not worthy of attention” had been importuning Lobengula for concessions since 1886 – Lippert for land, Dettelbach for a trading monopoly and both collaborated together. On the 18 November 1890 (i.e. after the Pioneer Column had raised the British flag at Salisbury on 13 September 1890) Dettelbach received a trading concession covering natural gums, cotton, rubber and the right to build roads. As the price of the concession was only £50 per annum, Lobengula’s purpose in granting the concession was clearly to divide the whites.

Rhodes and colonial office reaction

Rhodes and Sir Henry Loch both initially condemned the Lippert concession as a fraud. Loch assured Rhodes of colonial office support and stated that if Lippert tried to gazette his agreement, he would issue a proclamation warning of its infringement of the Rudd Concession and the BSAC’s Charter and threaten Lippert with legal action. Renny-Tailyour was arrested at Tati and his colleague, Hassforther returning from Germany, was arrested at Tuli. However Sir Henry Loch soon authorised their release on condition of their signing a declaration not to disturb the peace.

Rhodes protested that Lippert’s actions amounted to blackmail and that Lippert’s concession had no legal basis since the Rudd concession stated that Lobengula would give away no land without Rudd’s consent, but Alfred Beit thought the English courts might be sympathetic to Lippert and recommended negotiation. The last thing that Rhodes needed at this time was a drawn-out and expensive court case which they might not win, with its attendant publicity. Beit negotiated with Lippert, but probably because they were related, the talks broke down several times and after two months Rhodes asked Charles Rudd, who had negotiated many Boer farm sales on behalf of Gold Fields of South Africa, the company that held Rhodes’ gold interests, to take over the negotiations with Lippert.

An agreement with Lippert

On 12 September 1891 when the Pioneer Column was between the Umfuli, now Mupfure river and Fort Salisbury, now Harare, Rudd and Lippert agreed the BSAC would buy the concession negotiated by Renny-Tailyour providing that Lippert returned to Umvutcha and had the concession confirmed in “proper form” and the down payment of £1,000 accepted by Lobengula.

In return for a new concession, Lippert would receive the right to 75 square miles[vi] (48,000 acres) in Matabeleland with all land and mineral rights; 20,000 ordinary shares (0,7% of the total) in the United Concessions Company and 30,000 ordinary shares (3% of the total) in the BSAC, plus £5,000 in cash. Lippert was to invest £25,000 in developing the 75 square miles area within one year - all of which did not add up to the £250,000 he had initially demanded.

At this time of course Rhodes and the BSAC had no claim to any land in Matabeleland.

Why did the BSAC need the Renny-Tailyour and Lippert concessions?

The colonial office maintained all along that the BSAC had no power to grant valid land titles and initially the colonial office had asserted that the Lippert concession infringed on the Rudd concession and the BSAC’s Royal Charter. However disagreeable the notion was, Lippert through Renny-Tailyour had acquired a concession from Lobengula which granted land rights as Lobengula’s agent. It did not matter that the Rudd, Renny-Tailyour and Lippert concessions were all acquired under dubious circumstances. Rhodes said the Lippert concession was: “the one thing needful to give the Company the fullest jurisdiction in Lo Bengula’s territory.”[vii]

Transfer of the Lippert concession - Lobengula is subject to another deception

The success of this deception depended on Lobengula believing that Lippert was acting against Rhodes rather than on his behalf as Lobengula’s only reason for signing the Lippert concession was to stymie the BSAC; to slow down their operations and win himself time. Sir Henry Loch, the High Commissioner for Southern Africa wrote to John Moffat, his representative at Gubulawayo saying: “Your attitude towards Messrs. Lippert and Renny-Tailyour should not change too abruptly, though if consulted by the King you might profess indifference on the subject.” [viii]Moffat in turn wrote to Rhodes: “I feel bound to tell you, I look on the whole plan as detestable, whether viewed in the light of policy or morality…when Lobengula finds it all out…what faith will he have in you?”[ix] but agreed to go along with the sham, justifying his decision by deciding that Lobengula was just as untrustworthy as Lippert.

With Moffat as a witness, on 17 November 1891 Lobengula made his mark on a concession that gave Lippert: “In consideration for the payment of one thousand pounds having been made to me today, I do hereby grant Edward Amandus Lippert, and to his heirs, subject only to the annual sum of £500 being paid to me…the sole and exclusive right, power and privilege for a full term of 100 years to layout, grant or lease for such period or periods as he may think fit, farms, townships, building plots and grazing areas; to impose and levy rents, licences and taxes thereon, and to get in, collect and receive the same for his own benefit, to give and grant Certificates in my [Lobengula’s] name for the occupation of any farms, townships, building plots and grazing areas.”

The witnesses were Renny-Tailyour, Reilly, James Fairbairn and James Umkisa, one of Lobengula’s servants. Tainton and Acutt interpreted; John Moffat certified: “that this document is a full and exact expression of the Chief Lo Bengula.”[x]

Marie Lippert

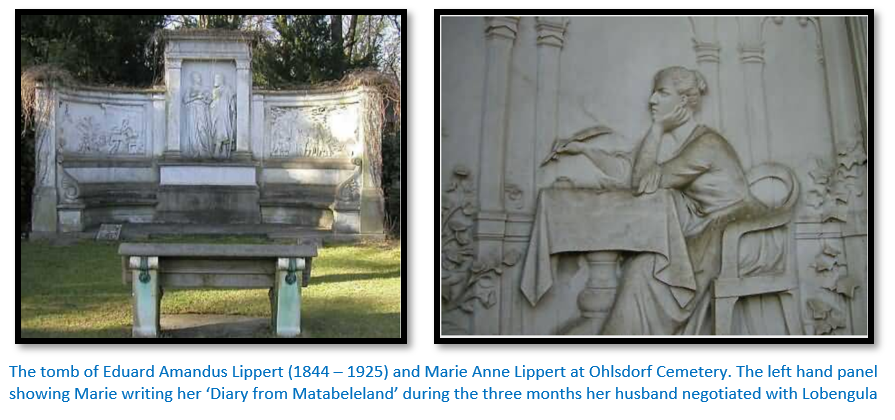

Marie Lippert accompanied her husband on the three month journey (21 Sept to 22 Dec 1891) to Matabeleland and her sketches and letters to friends and family describing their travels and living in an ox-waggon tell of the difficulties of the journey, but also of her cheerful curiosity in the life of the native people they encountered.

An unexpected blessing for the BSAC

Lippert sold his rights to Rudd on 24 December 1891 and Rudd transferred the rights to the BSAC on 11 Feb 1892; Sir Henry Loch subsequently approved the concession with the colonial office expressing satisfaction that the question of land rights for the BSAC was now solved and on 5 March 1892 the Secretary of State, Lord Salisbury cabled his approval of the Lippert concession and its transfer from Rudd to the BSAC. All these transactions were kept secret from Lobengula.

In the end Rhodes concluded that the Lippert concession turned out to be an unexpected blessing as although it did not acquire the land, it acquired the right to confer title to land on Lobengula’s behalf which the Rudd concession itself lacked and was required if the colonial office was to recognise that the BSAC legally owned the occupied territory in Mashonaland. In other words, it was the Lippert concession preceded by the Renny-Tailyour concession that gave teeth to the Rudd concession.

Colonial Office approval in 1893 of BSAC arrangements concerning land

Lord Knutsford expressed himself satisfied with the validity of both the Rudd and Lippert concessions and any queries were smoothly brushed aside. For example this question quoted in Hansard from Mr Labouchere on 4 May 1893:

“I beg to ask the Under Secretary of State for the Colonies whether his attention has been called to an advertisement in the public press of the prospectus of the Mashonaland Development (Willoughby's) Company, in which it is stated that the promoter of the company has obtained from the British South Africa Chartered Company a concession of 600,000 acres of land in any part of Mashonaland, outside a radius of three miles of any proclaimed goldfield or established township; whether the entire land of Mashonaland belongs to the Chartered South Africa Company; if so, from whom possession has been obtained; whether the vendor himself was the owner of the entire land of Mashonaland, and had a right to sell it irrespective of the assent of its inhabitants; whether this assent was obtained, and, if so, how and when; and whether such sale has been sanctioned by Her Majesty's Government; and, if so, whether any investigation of the title of the vendor took place, and any stipulations were made with regard to the native population?

The under-secretary of State for the colonies, Mr Sydney Buxton replied:

“I have seen the advertisement referred to in the first paragraph of the question. The British South Africa Company are assignees for value during a term which has 98½ years to run, of the rights of Lo Bengula to grant and lease farms, grazing grounds, and town areas, in Mashonaland, and to hold for their own benefit the rents and other profits arising from such grants. The company acquired these rights from one Edward Amandus Lippert, to whom Lo Bengula had granted them. If by "vendor" in the third paragraph of the question Lo Bengula is meant, the answer is that Lo Bengula has control, as paramount Chief, though he probably has not the sole ownership, of the lands of Mashonaland. The assent of the Mashonas was not necessary to validate the concession, as it covered only that which Lo Bengula had a right to grant. The Lippert concession and its transfer to the British South Africa Company were approved by Her Majesty's late Government. No investigation of the title of the vendor (Lo Bengula) took place on that occasion, and no stipulations were then made with regard to the native population; but Her Majesty's Government had already considered the position and claims of Lo Bengula in the Mashona country, and the right of natives in the company's field of operations had been safeguarded by Article 14 of the Charter granted to the company in October, 1889. The whole Lippert concession appears to be understood by the Chartered Company as referring to unoccupied lands. I may add that the Directors assure the Colonial Office that they have no intention of interfering with native occupation in this sparsely-populated country, and that their local administrator, Dr Jameson, will be careful not to sanction the selection by Sir John Willoughby's Company of any blocks of land, the acquisition of which would be inconsistent with native rights under the company's Charter.

Mr Labouchere asked: “Is there no one connected with the Colonial Office on the spot to see that the Directors of the company keep their engagements?”

Mr Sydney Buxton replied: “We have no administration in Mashonaland, and no right to exercise jurisdiction.”

Lord Knutsford did not concern himself with the obvious fact that the concession was a personal contract between Lippert and Lobengula; once satisfied that the concession had been successfully transferred to the BSAC, he simply endorsed the deed of transfer to the effect it could not be assigned again without the approval of the colonial office.[xi]

Lobengula unaware

The Matabele and Lobengula remained unaware of this subterfuge until May 1892 when they learned from John Moffat that in fact the BSAC and not Eduard Lippert owned the concession. Moffat wrote: “He evidently did not like the idea at all and could not understand how it could have been brought about, so possessed is he with the conviction that these interests are entirely irreconcilable.” [xii] Moffat told Colenbrander: “The King was a good while before he took in the idea and he is not very cheerful about it. But there you are, at least this should mark the end of all those discreditable intrigues. I have a shrewd idea that if anybody else ever mentions the word concession to Lobengula, he will do so at no little peril to himself.”[xiii]

Lobengula was out-manoeuvred because Rhodes purchased the Lippert concession in an effort to consolidate and strengthen the BSAC in the eyes of the colonial office. Rhodes might have taken a different course and disputed the Lippert concession on the grounds that it contravened the clause in the Rudd concession, but speed was now of the essence and purchasing the Lippert concession was the most expedient approach.

Same contradiction as the Rudd concession

As with the Rudd concession, Lobengula was unaware of the contradiction in granting a concession to an individual [Eduard Lippert] in that the concession was a legal document with transferable rights which could be sold to a commercial concern, in this case the BSAC. Clearly in Lobengula’s mind he was appointing Renny-Tailyour and then Lippert as his agent with powers of delegation on his [Lobengula’s] behalf. He was not signing away any rights to layout, grant or lease land to the BSAC in Mashonaland or Matabeleland – however it is hardly surprising that he failed to understand the complexities of British commercial law.

With the Rudd concession together with the Lippert concession and the royal charter the BSAC could grant title-deeds and issue leases and rent land “on Lobengula’s behalf.” i.e. create a legal system defined by the law rather than by native custom.

Occupation of Mashonaland July – September 1890

Members of the Pioneer Column were recruited from all over South Africa—they were not paid salaries or any cash in return for their services; the incentive was that each of the 196 pioneers was promised a free farm of 3,175 acres (1,500 morgen) and 15 reef claims of 400 x 150 feet. The primary interest of these young men was gold and therefore many of the pioneers sold their land claims to speculators for about ₤100 each while still on the march to Salisbury, now Harare.

Marshall Hole says that immediately after the disbandment of the Pioneers, Colquhoun was authorised by Rhodes to issue a notice introducing a simple scheme of civil and criminal law based on a draft issued by Sir Sidney Shippard, but the colonial office refused to recognise this notice because no authority had been granted by Lobengula. The other defect in the Rudd concession; the absence of land title was simply disregarded in anticipation of a future land settlement being negotiated and the Pioneers were given permission to peg out and occupy their promised farms.

Colquhoun, the first Administrator, recognised that the BSAC had no legal right to grant land titles and believed the permission of the Mashona chiefs was required before farms could be allotted to the pioneer settlers.

His successor, Dr Leander Starr Jameson, did not share Colquhoun’s views on land rights and when individual settlers claimed that the farms they had been allotted were heavily wooded and unsuitable for farming, he allowed them to choose new farms.

In addition there was two forms of title deed; one for the Pioneers and another for the rest. Bona fide and beneficial occupation was required of the rest, but not for the Pioneers as they complained to Rhodes that they could not occupy their farm grants when they were expected to be looking for gold. [xiv] Otherwise all were expected to pay an annual quit-rent of £3 per 3,175 acres, the normal farm size.

During 1891 Mashonaland was already being surveyed for farms even though the BSAC did not acquire the Lippert concession until 11 Feb 1892.

Jameson also persuaded members of the British aristocracy, Henry and Robert White, sons of Lord Annaly and Sir John Willoughby to come to Mashonaland on the promise of land grants.

Jameson also persuaded members of the British aristocracy, Henry and Robert White, sons of Lord Annaly and Sir John Willoughby to come to Mashonaland on the promise of land grants.

Chief Lobengula reminds the BSAC who own the land

In November 1891 Chief Nemakonde (Lomagundi) was visited by the amaNdebele who had some questions for him. Why had he accepted presents from the Portuguese and English? Why had he shown the English where to dig for gold and given them guides to lead them to the Zambezi river? Why had he not paid his usual annual tribute?

Lobengula’s envoys stated all this had been done without his permission. Chief Nemakonde wanted to give his response in the morning, but immediately the amaNdebele envoys came they killed the chief and three of his headmen. In his reply to Jameson Lobengula said: “I sent a lot of my men to go and tell Lomogunda to ask you and the white people why you were there and what you were doing. He sent word back to me that he refused to deliver my message and that he was not my dog or slave. That is why I sent some men in to go and kill him. Lomogunda belongs to me. Does the country belong to Lomogunda?”

Gold a disappointment

The BSAC was founded on the hope that the mineral deposits in Mashonaland would be comparable to those on the Witwatersrand…this was the premise on which the Royal Charter was granted and on Rhodes’ argument that the gold mines that were subsequently established would provide sufficient capital to develop the territory without the British Treasury having to contribute funds. He told the editor William Stead: “I quite appreciate the enormous difficulties of opening up a new country, but still if providence will furnish a few paying gold reefs I think it will be all right.”[i]

By the early 1890’s some mines were established but it was obvious that Mashonaland was not going to be a ‘second Rand’ and the BSAC was running short of cash. As a solution the BSAC moved towards the broad seizure of land and its distribution to settlers for commercial farming in the hope they would develop productive farms and generate enough revenue to cover the BSAC administration expenses. Land resettlement schemes were started and commercial crops such as tobacco and citrus encouraged.

As part of this scheme indigenous people were moved off land of high quality or in good rainfall areas; Native Reserves and Tribal Trust Lands were reorganized and often reduced in size or relocated.

Encroachment on African lands

Initially in 1891 Colquhoun attempted to restrict this encroachment by confining farms to between the Hunyani, now Manyame and the Umfuli, now the Mupfure and there was no pegging of farms within six miles of Salisbury, now Harare. But Jameson removed the first restriction and Rutherfoord Harris reduced the second to three miles.

Restrictions were similarly lifted in 1893-4 when Matabeleland was occupied. Volunteers in the Victoria and Salisbury columns were each entitled to 6,350 acres (3,000 morgen) After the occupation the core of the amaNdebele nation was soon pegged out for farms and there was no question of avoiding native villages and gardens.

From 25 April 1894 farms could be purchased by anyone in Matabeleland for 3s. per morgen providing the farm was occupied within a minimum of five months and for at least three years of continuous occupation and that buildings were constructed worth at least £200.

Land grants and speculation in land companies

Because individuals could only hold one farm, an easy solution was to hold multiple farms through companies and according to W.H. Brown by the end of 1891 half the pioneer’s rights to their farms had been sold. Initially all looked well: in 1892 when Percy Inskipp sent Rutherfoord Harris a list of farm grants; 11 had two farms each, 2 had small grants, the remaining 327 had one farm each, so presumably the farm sales had not been registered.

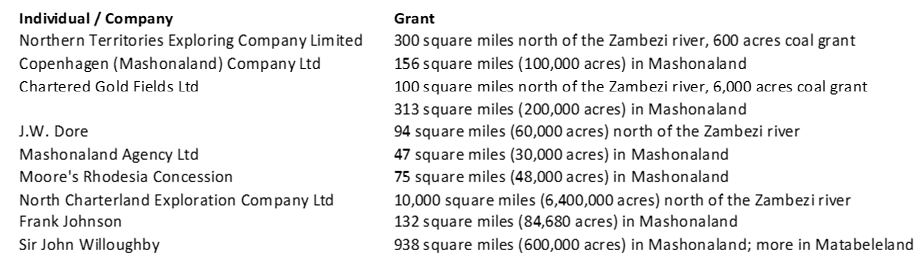

In fact, huge grants were made to favoured individuals and companies:

Land grants to February 1893 amounted to 2,061,000 acres (3,220 square miles) Sir William Milton said “that Jameson had given away nearly the whole country to the Willoughby’s, Whites and others of that class so that there is absolutely no land left which is of any value for settlement of immigrants by Government…I think Jameson must have been of his head for some time before the raid.”[ii] From April 1893 free land grants were stopped and land was sold in Mashonaland by the BSAC for 1s 6d. per morgen, although only about 300 farms were occupies at the end of 1892.[iii]

A number of speculative companies were formed to purchase land and attracted over £20 million in start-up capital. Many land grants were quickly sold and over the 15.8 million acres given over to farms and land grants; 9.3 million acres or 59% quickly ended up owned by companies. In 1892 Rhodes who trusted Jameson implicitly said: “We must make no more of these land grants, they will close up the country. We must have occupation by individual farmers.”[iv] Robert Blake writes: “Few of them paused to reflect on the legal aspect of these exciting promises. The status of the farms was particularly questionable, for the company was not in a position to give valid title to land.”

Raising capital for development

Those individuals who had been persuaded to embark on the exciting prospect of being the first into the country on the promise of their land grants and mining claims soon came to understand that there were few surface gold prospects and sold out their rights to speculators at the going rate of £100 each.[v]

Development of Mashonaland required financial capital from sources outside the BSAC as the company’s own resources were limited and soon being spent on the Pioneer Column (£90,000) and the Police Force (650 men at the end of 1890 cost £300 each per annum) Most of the large land grants listed above required the recipients to invest heavily as a condition of their land grants, although many in fact failed to make the investment.[vi] Even Eduard Lippert as a sale condition of the Renny-Tailyour concession was required to invest £25,000 in developing the 75 square miles area within one year.

A final decision

For nearly twenty-five years the BSAC was allowed to sell land, grant title-deeds and leases without any suggestions that a flaw existed. Even Lobengula’s presumed death in 1894 produced no statements that the BSAC’s position in regard to land was in any way affected.

In 1918 matters came to a head over who owned the “unalienated lands” which were yet to be allocated. The BSAC’s case rested upon the Renny-Tailyour and Lippert concessions described above in which the BSAC and Colonial Office both chose to recognise that Lobengula could delegate the legal power to grant title-deeds and issue leases and rent land. i.e. create a legal system defined by the law rather than by native custom.

On 26 July 1918, in Re Southern Rhodesia the judgement of the Judicial Committee of the UK’s Privy Council found the whole transaction illegal, the result being that the Lippert concession was declared null and void as a title deed. The concession had merely made Lippert the agent in land transactions; it had given him no right to use the land or to take its usufruct. Indeed, under customary law, Lobengula had no authority to make any award of Ndebele land, let alone Mashona land.

Land titles granted by the BSAC were legally valid, but the indigenous peoples had lost their land rights through conquest and all unalienated land was ruled to belong to the Crown. The BSAC was awarded £3,750,000 for its past administration expenses, plus a £2million waiver of its war debts, and the right to keep its extensive mineral rights, commercial assets and land that it had allocated to itself. Indigenous people received no compensation. But by 1918 of course, Lobengula was long since dead; and both the Ndebele and the Shona had been stripped of much of their land.[vii]

The above judgement removed a major stream of revenue for the BSAC through the sale of land; it had the effect of not only damaging the company’s ability to pay dividends but reduced the funds for development in Rhodesia. The BSAC did retain its mineral rights until 1933 when they were sold for £2 million to the Southern Rhodesian government.

Unintended consequences of the land issue

The 1918 decision that ruled that all unalienated land belonged not to the BSAC but to the Crown and the subsequent loss of revenue led to the BSAC backing the proposal that the country become part of the Union of South Africa. This prospect proved very unpopular in Rhodesia and in the 1920 Legislative Council Election the Responsible Government Association won ten of the 13 seats contested.

A referendum on 27 October 1922 won a 60% majority for responsible government. The British government chose not to renew the Company's charter, and instead gave self-governing colony status to Southern Rhodesia on 12 September 1923 and then granted full self-government on 1 October the same year.

The new Southern Rhodesian government immediately purchased the unalienated land from the British treasury for £2 million. The Company retained mineral rights in the country until 1933, when they were bought by the colonial government, also for £2 million.

Subsequent Controversy over the Renny-Tailyour concession

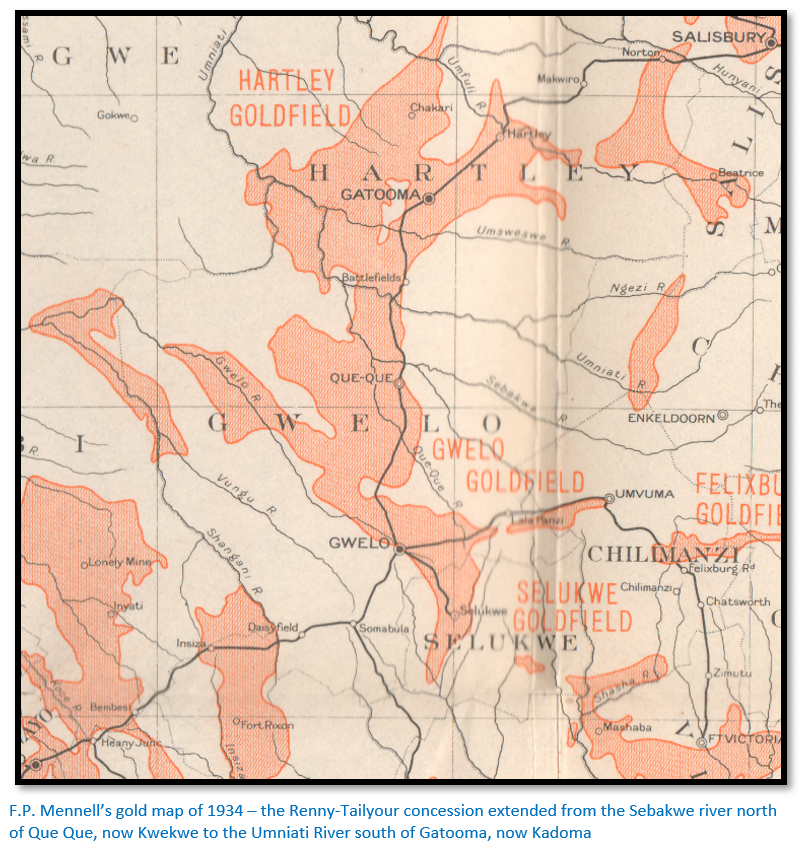

The Cherer-Smith article concentrates on the land and mineral rights awarded to Lippert covering the associated four blocks of land (East Clare, Sherwood, Umsweswe and Sebakwe) which were owned by a succession of companies (Matabeleland and Manicaland Syndicate Limited, Matabeleland Development Company, Exploring Land and Minerals Company, London and Rhodesia Mining and Land Company, Lonrho) and subject to various agreements in 1894, 1909 and 1947. Even the area of the concession is confusing – Cherer-Smith says 125 square miles; most subsequent writers state 75 square miles! The concession area shown in the map below lies between the Sebakwe and Umniati rivers and includes Battlefields with the Old Hunters Road forming a border in an area that contained much evidence of pre-colonial mining and even today hosts much artisanal gold-mining activity as shown by a recent flooding tragedy.

Dr Jameson, the Acting Administrator signed the initial land certificates on 3 July 1894;[viii] however from the start there was disagreement over whether mining royalties were payable to the BSAC under the terms of the concession. This was settled in 1909 when it was agreed that payments under the Mines and Minerals Ordinances were exempt, but mineral royalties were payable to the BSAC. In 1930 the London and Rhodesia Mining and Land Company (subsequently Lonrho) acquired the East Clare block but there was considerable confusion over the actual area covered by the block (14,920 or 10,884 morgen) and the boundaries of the actual area as the route of the Old Hunters Road which formed one boundary was now uncertain.

By 1949 only three gold mines were operating, but a dispute between Lonrho and the Mining Affairs Board over tribute agreements rumbled on until 1956 when the government under the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland terminated the Renny-Tailyour Concession and opened the area for general prospecting.

Eduard Amandus Lippert

In 1890 Lippert bought part of the farm Braamfontein and rebuilt the farmhouse for himself and his wife, Marie, naming it Marienhof after her death in 1897. He started the Sachsenwald plantation to supply timber to the mines, now the suburb of Saxonwold in northern Johannesburg. The Pro-Boer Lippert made his fortune from a monopoly dynamite concession, often cited as a cause of the war by the Uitlanders and assisted the Boers in buying guns from Germany. Lippert left the Transvaal on the outbreak of war, never to return. Bulpin calls him “the evil genius of the Transvaal” and states he had “an extraordinary and rapacious greed for money.”[ix] In Germany in his later years he is known for his philanthropy; to commemorate his wife Lippert donated the nursing home Mariensruh in Groß Borstel , as an orphanage and now a school.

Edward Ramsay Renny-Tailyour (1851 – 1894)

Renny-Tailyour, Lippert’s agent at Gubulawayo, negotiated a dubious concession with Lobengula which permitted the grant of land titles as Lobengula’s agent for 100 years. Renny-Tailyour died on 14 June 1894 near Mangwe travelling by coach from Bulawayo – John McCarthy in his Heritage article[x] suggests that because Renny-Tailyour was so unpopular with the BSAC his death attracted little attention and there is no deceased estate record for him. He is recorded by the Loyal Women’s Guild in 1909 as ‘W. Rennie-Tailyour’ with a white sandstone cross on grave No 10…only five of the nineteen graves within the cemetery are identified. Bulpin says Renny-Tailyour “who generally insulated himself from the surrounding world by a defensive glow of alcohol, found the Lippert’s distasteful” and said to Johan Colenbrander: “I call him the famous partnership of Dr Lippert and Mr Hyde, no chemistry is needed to make the demoniac change, only the jingle of gold in somebody else’s pocket.”

Text of the Lippert Concession[xi]

To all of whom these Presents shall come, I, Lo Bengula, Kind of the Amandabele nation, and of the Makalaka, Mashona, and surrounding territories, send greeting:

Whereas I have granted a concession in respect of mineral rights, and the rights incidental to mining only, and whereas my absolute power as paramount King to allow persons to occupy land in my kingdom, and to levy and collect taxes thereon, has been successfully establishes; and whereas, seeing that large numbers of white people are coming into my territories. And it is desirable I should assign land to them, and whereas it is desirable that I should once and for all appoint some person to act for me in these respects:

Now, therefore, and in consideration of the payment of one thousand pounds (£1,000) having been made to me today, I do hereby grant to Edward Amandus Lippert, and to his heirs, executors, assigns, and substitutes, absolutely, subject only to the annual sum of £500 being paid to me or to my successors in office, in quarterly instalments, in lieu of rates, rents and taxes, the following rights and privileges, namely:

The sole and exclusive right, power and privilege for the full term of one hundred (100) years to lay out, grant or lease, for such period or periods as he may think fit, farms, townships, building plots and grazing areas, to impose and levy rents, licences and taxes thereon, and to get in, collect and receive the same for his own benefit, to give and grant certificates in my name for the occupation of any farms, townships, building plots and grazing areas; to commence and prosecute, and also to defend in any competent court in Africa or elsewhere, either in my name or in his own name, all such actions, suits, and other proceedings as he may deem necessary for establishing, maintaining, or defending the said rights, powers and privileges hereby conferred; provided always that the said rights and privileges shall only extend and apply to all such territories as now are, or may hereafter be, occupied by, or be under the sphere of operations of the British South Africa Company, their successors, or any person or persons, holding from or under them, and provided that from the rights granted by these presents are excluded only by the grazing of such cattle, the enclosing of such land, and the erection of such buildings and machinery as are strictly required for the exercise of the mineral rights now held by the British South Africa Company under the said concession.

The powers granted to E. Ramsay Renny-Tailyour, under date of 22nd April. 1891, are hereby withdrawn and cancelled in so far as they are in conflict with these presents.

Given under my seal at Umvutcha this 17th day November 1891.

Elephant Seal Lo Bengula

Witnesses (signed) E.R. Renny-Tailyour

James Riley

James Fairbairn

James Umkisa’s cross

(signed) Ed. A. Lippert

References

R. Blake A History of Rhodesia (Eyre Methuen, London 1968)

T.V. Bulpin. To the Banks of the Zambezi. Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1965

C. Chavunduka and D.W. Bromley. Beyond the Crisis in Zimbabwe: Sorting out the Land Question. Development Southern Africa 27, 2010

R. Cherer Smith. The Rennie Tailyour Concession. Rhodesiana Publication No 38, March 1978

M.O. Collins. Rhodesia – Its Natural Resources and Economic Development, Salisbury 1965

A. Darter. The Pioneers of Mashonaland. Books of Rhodesia Silver Series Vol 17, Bulawayo 1977

J.S. Galbraith. Crown and Charter; The Early Years of the BSAC. University of California Press, 1974

Hansard 4 May 1893 Vol 12, 70-72

A. Keppel-Jones. Rhodes and Rhodesia, the White Conquest of Zimbabwe 1884 – 1902. McGill-Queens’s University Press, 1983

H. Marshall Hole. The Making of Rhodesia. Frank Cass and Company, Abingdon 1926

J. McCarthy. Mangwe Cemetery. Heritage of Zimbabwe Publication No 14, 1995

M. Meredith. Diamonds, Gold and War. Simon and Schuster, 2007

R. Palmer. Land and Racial Domination in Rhodesia. Heinemann, 1977

R.I. Rotberg. The Founder, Cecil Rhodes and the Pursuit of Power. Oxford University Press, 1988

R. Sampson. White Induna; George Westbeech and the Barotse People. Xlibris Corporation, 2008

Wikipedia

[i] The Founder, Cecil Rhodes and the Pursuit of Power, P336

[ii] Ibid, P369

[iii] Crown and Charter, P281

[iv] Ibid, P280

[v] Ibid, 257

[vi] Ibid, P278

[vii] Diamonds, Gold and War, P277

[viii] R. Cherer Smith. The Rennie Tailyour Concession, P35

[ix] To the Banks of the Zambezi, P311

[x] Mangwe Cemetery, P141

[xi] Pioneers of Mashonaland, P189

[i] Diamonds, Gold and War, P276

[ii] Rhodes and Rhodesia, P181

[iii] Ibid, P85

[iv] White Induna, George Westbeech and the Barotse people, P139

[v] Ibid, P175

[vi] R. Cherer Smith. The Rennie Tailyour Concession. Rhodesiana Publication No 38, March 1978. In the article the author states the concession covered 125 square miles (80,000 acres) P35

[vii] The Founder, Cecil Rhodes and the Pursuit of Power, P336

[viii] Diamonds, Gold and War, P277

[ix] The Founder, Cecil Rhodes and the Pursuit of Power, P337

[x] Rhodes and Rhodesia, P183

[xi] The Making of Rhodesia,

[xii] Ibid, P227

[xiii] To the Banks of the Zambezi, P311

[xiv] Rhodes and Rhodesia. P367